1. Introduction

The use of American rootstocks in viticulture was introduced as the primary strategy to combat the Phylloxera epidemic that nearly destroyed European vineyards during the 19

th century. While the European grapevine (

Vitis vinifera L.) is highly susceptible to the root-feeding form of the insect, American species such as

V. riparia, V. rupestris, and

V. berlandieri exhibit natural resistance due to co-evolution with the pest [

1,

2]. Therefore, grafting European grape varieties onto American - often interspecific - rootstocks remains the standard and most effective strategy to prevent Phylloxera damage [

3,

4]. However, rootstocks play a broader role as they display multiple properties including resistance to soil-borne pests and diseases (such as nematodes and fungal pathogens), adaptation to diverse soil conditions (i.e., drought, salinity and excessive CaCO₃), control over vine vigor and nutrient uptake, improved compatibility with specific scion varieties and improved fruit composition [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9].

Previous studies have shown that rootstocks can significantly influence berry composition, particularly the accumulation of flavonoids, anthocyanins, and tannins, which are critical for wine color, structure, and aging potential [

4,

10]. These effects are often linked to rootstock-mediated changes in berry skin development, water status, or nutrient partitioning during ripening. Moreover, rootstocks may alter important parameters such as total soluble solids, titratable acidity, and pH in the must, thereby shaping the resulting wine profile [

11,

12]. While nitrogen availability plays a role in these outcomes, the impact of rootstock on secondary metabolites - such as phenolics - appears to involve broader physiological and metabolic pathways, often interacting with environmental factors such as drought and soil composition [

13,

14].

Nitrogen (N) is a key nutrient for vine growth and berry development, but it also has a direct impact on wine production by influencing alcoholic fermentation, particularly through its contribution to yeast-assimilable nitrogen (YAN), which includes ammonium and amino acids essential for the yeast during fermentation [

15]. Low YAN concentrations can lead to slow or stuck fermentations and the formation of undesirable sulfur compounds, while excessive YAN may increase volatile acidity and microbial instability [

16]. Although nitrogen can be supplemented to the must, either in organic or inorganic form, before or during fermentation to optimize fermentation kinetics and enhance wine aroma [

17], the naturally occurring nitrogen levels in the vine and grapes hold multiple aspects of importance. These nitrogen levels are assumed to be partially dependent on the vigor imparted by the rootstock to the scion [

18]. However, the mechanisms and overall effects of rootstocks on N levels in the vine and grapes have not been yet fully understood [

19]. Evidence suggests that rootstock genotype can influence nitrogen uptake, transport, and assimilation [

20] through root-specific gene regulation [

21].

The influence of rootstocks on grapevine performance and fruit composition has been extensively studied only in major international cultivars such as Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, Cabernet Sauvignon, and Shiraz [

11,

22,

23,

24], while some additional research exists on varieties like Albariño [

25]. However, studies on indigenous cultivars remain limited.

Assyrtiko is an indigenous Greek variety renowned for retaining high acidity under warm and dry conditions, primarily associated with the unique volcanic terroir of Santorini [

26]. It has recently gained wider recognition and cultivation in Greece and abroad due to its viticultural and oenological potential [

27]. Rootstock effects on Assyrtiko have not been thoroughly explored. Moreover, while rootstock effects on vine growth and berry composition are well documented, their influence on sensory characteristics and overall wine quality has received comparatively little attention, particularly for indigenous varieties.

The main objective of the present study was to assess the effects of five commonly used rootstocks (110 R, 140 Ru, 3309 C, 41 B, and FERCAL) on nitrogen levels, grape and wine composition, and sensory attributes of wines produced from Assyrtiko grapes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Vineyard Site and Management - Experimental Design

The study was conducted at the experimental vineyard of the university of West Attica in Egaleo Grove (37º59'52"Ν, 23º40'34"Ε). The soil across the entire plot was homogeneous and classified as loam, consisting of 50.1% sand, 34.5% silt, and 15.5% clay. It exhibited a pH of 7.3, an organic matter content of 1.84%, and a total calcium carbonate (CaCO₃) content of 25.5%. Meteorological conditions were uniform across the entire experimental plot. The study was conducted during the 2023–2024 season that was characterized as a moderate and relatively late-ripening vintage for the Attica region. All vines shared the same scion material, grafted with the Assyrtiko cultivar (clone E16), ensuring that rootstock was the only experimental variable. Each pair of planting rows was assigned to a different rootstock, with each row consisting of 30 vines (60 vines per rootstock). For the experiments, a randomized block experimental process was designed [

28], with 20 vines per replicate (block) and three replicates per rootstock. Vines were trained to a unilateral “Cordon de Royat” system and pruned to 8-10 buds per vine. Shoot thinning was carried out twice in each growing season, and shoot topping was performed when shoots reached a length of approximately 1.10 m. Drip irrigation was applied biweekly (beginning in mid-May) and moderate fertilization with Nutri-Leaf 20-20-20+T.E. (Miller, Hanover, PA, USA) was performed twice a year. Grape harvest occurred on the 7

th of September 2024, during the morning. Berry sampling involved the random collection of 6–8 berries from various parts of randomly selected clusters. Sampling was conducted separately for each replicate.

2.2. Must Preparation and Micro-Vinification

Grapes were manually crushed and the extracted juice was filtered through a 0.5 mm sieve to remove coarse particles. A representative must sample of 250mL from each replicate was kept for the oenological analyses. The remaining must was centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 5 minutes. An aliquot part of the centrifuged must was transferred into plastic Eppendorf tubes and frozen at -20 °C for later analysis of yeast-assimilable nitrogen (YAN). The rest was transferred into new 1.5 L plastic fermentation bottles equipped with integrated airlocks. The yeast strain

Saccharomyces cerevisiae VIN 13 was used across all micro-vinifications, as a single inoculum, to verify uniform fermentation conditions. Yeast was rehydrated in deionized water (10 g / 100 mL), was stirred using a sterile glass stirring rod, and maintained at 30 °C for 30 minutes. Following rehydration, inoculation was performed using a graduated pipette, delivering 3 mL of yeast suspension into each must sample to achieve a final concentration of 30 g/hL. Bottles were sealed, and airlocks were filled with pure ethanol (99.8%). Micro-vinification was conducted in triplicate for each rootstock and each replicate had a volume of approximately 1L. Fermentations were carried out at 20 ± 2 °C until the must density stabilized, indicating completion. Throughout fermentation, monitoring, visual determination of the yeast strain under microscope (Olympus CX21, Tokyo, Japan), and density measurements (

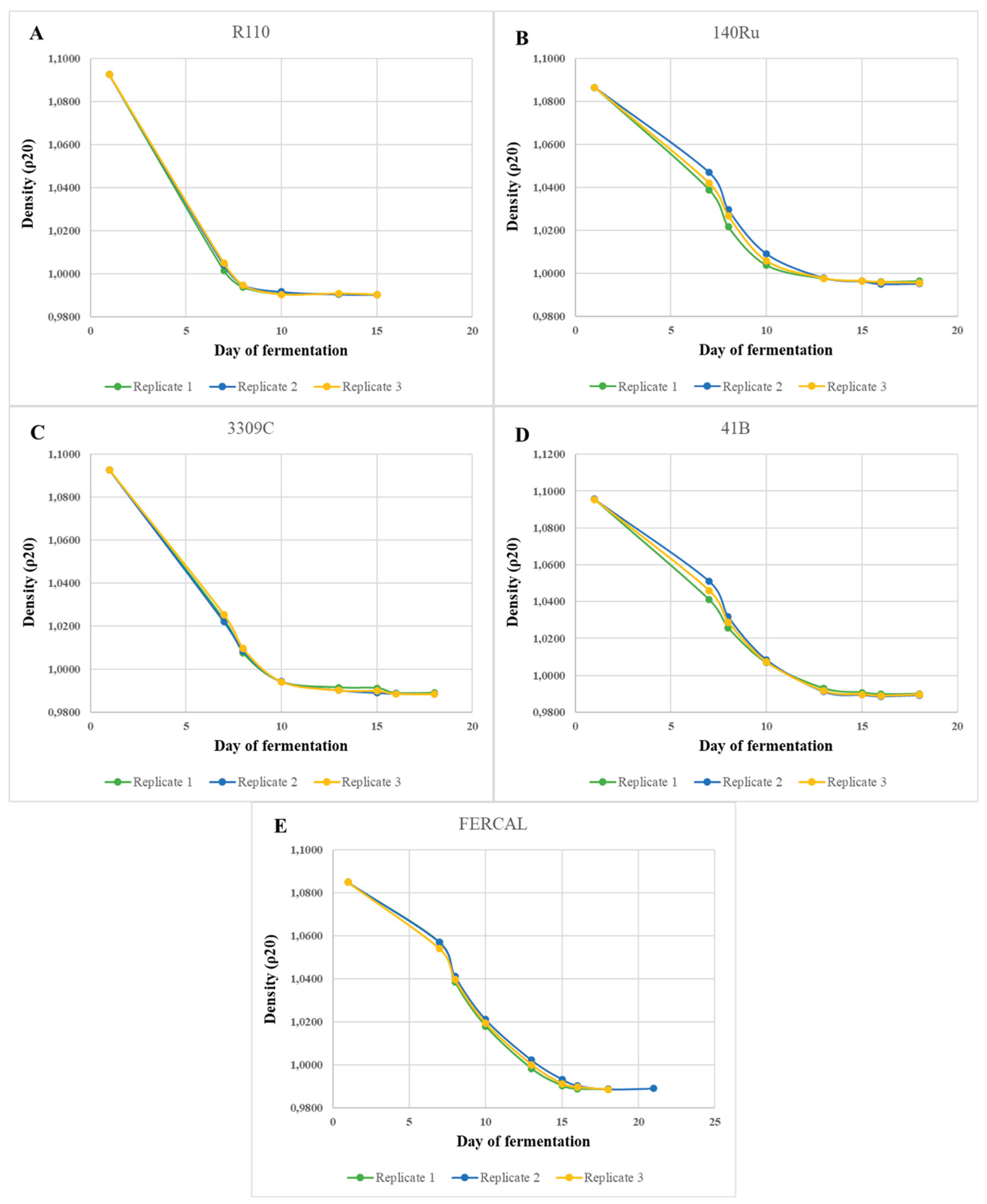

Figure 1), were conducted on a daily basis.

2.3. Chemical Analyses

2.3.1. Classical Analyses in Musts and Wines

Sugar Content (°Bé) and Density (g/L) were measured in centrifuged must samples using a portable density meter (DMA 35 BASIC, AntonPaar, Graz, Austria). pH in both must and wine samples was measured with a pH meter (Hanna Edge HI 2002-02, North Kingstown, RI, USA). Ethanol content (alcoholic strength, % vol), titratable acidity (TA, g tartaric acid /L), and volatile acidity (VA, g acetic acid /L) were measured according to International Organization of Vine and Wine (OIV) methods [

29]. Reducing Sugars (RS) in wine samples were determined using the Luff method, in accordance with the OIV protocols [

29].

2.3.2. Total Tannins (TT)

To determine the total tannin content (TT) in wine samples, the Bate Smith method (or acid hydrolysis) was used, whereby tannins (proanthocyanidins) are converted to anthocyanins through heating in an acidic environment [

30]. Briefly, from each wine sample, two aliquots were taken: one was boiled, and the other remained at room temperature. The optical densities (absorbance) of both samples were measured at 550 nm using a UV mini 1240 spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan), with a 10 mm path length cuvette. To calculate total tannins in g/L of wine, the absorbance values were applied in the following formula:

where: d

₁ = absorbance of the unheated sample, d₂ = absorbance of the heated sample and k = 19.35 if (d₂ − d₁) > 0.07 or k = 20.83 if (d₂ − d₁) ≤ 0.07.

2.3.3. Nitrogen Levels Determination

In must and wine samples, free amino nitrogen (FAN) and ammonium nitrogen concentrations were measured using an automatic enzymatic analyzer (Hyperlab, Steroglass), with the appropriate enzymatic kits, following the analyzer’s instructions. FAN enzymatic determination was based on the NOPA method [

31]. Yeast assimilable nitrogen (YAN, mg N/L) was calculated as the sum of FAN and ammonium nitrogen.

All of the above chemical analyses were conducted in triplicate.

2.4. Sensory Evaluation

The organoleptic study took place under optimum conditions in the laboratory of ‘Sensory control’ at the Egaleo Park campus of the University of West Attica. The study was conducted by a panel of eight (8) experienced accessors (expert panel) consisting of 50% male and 50% female tasters aged from 26 to 46 years old. The wines were served in standard ISO wine tasting glasses (INAO type), with a capacity of 220 mL, at a serving temperature of 10-11°C. Tasting was blind and randomized as wines from different rootstocks were served simultaneously at glasses that displayed only a code number. The organoleptic attributes evaluated in the present study were: color intensity, aromatic intensity, aromatic complexity, aromatic character, perceived acidity, perceived sweetness, astringency, alcohol perception, body/concentration, balance, aftertaste duration, and overall quality. Evaluation was based on the judgment of the expert panelists using a 10-point scale for each parameter. The entire evaluation was repeated one week after the first one by the same panel.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS v.29 (IBM Chicago, IL, USA). One-Way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was performed for each parameter to investigate significant differences. One-Way ANOVA was followed by post-hoc tests to indicate differences among specific rootstocks. Tukey’s HSD post-hoc test was primarily used if allowed by assumptions. Prior to analysis, Levene’s test was performed toexamine the assumption of equal variances.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemical Composition and Nitrogen status of Assyrtiko Must

Rootstock genotype overall presented a strong influence on must composition. Baumé degrees and must density differed significantly among rootstocks (

Table 1), indicating rootstock-based effects on appearance time of phenological stages including ripeness. Corso et al. [

32] reported that rootstock selection may affect ripeness levels by modulating auxin-related genes, as ripeness is regulated by a multipart network of mobile signals including auxins and other hormones. In the present study, Baumé ranged from 11.7° in 140Ru (significantly lowest) to 12.8° in FERCAL (significantly highest), with R110 and 3309C occupying intermediate positions and 41B intermediate high. As expected, density followed a similar pattern as 41B and FERCAL showed the highest mean densities (1.0955 and 1.0950 g/L, respectively), while 140Ru had the lowest (1.0866 g/L). Such rootstock-driven shifts in ripening and soluble solids are commonly attributed to differences in water relations, nutrient uptake and vigor mediated by the rootstock [

33]. As previously reported, rootstocks that confer high vigour to the scion can extend the vegetative growth cycle, thereby delaying ripening [

32,

34].

Total titratable acidity also differed among rootstocks (

Table 1). 41B, Fercal and 140Ru were grouped among the higher-acidity musts (4.93, 4.90 and 4.88 g/L, respectively), whereas 3309C produced the lowest TA (4.48 g/L). Correspondingly, pH varied significantly, R110 musts had the highest pH (4.25), while 41B presented the lowest pH (4.01). The inverse relationship between TA and pH across rootstocks suggests differences in acid accumulation and cation (notably K⁺) uptake, processes known to be modulated by rootstock genotype and to influence must buffering capacity and subsequent wine stability. These rootstock effects on acidity are in line with prior observations in other cultivars [

11,

33,

35].

Nitrogen status (FAN, ammoniacal N and YAN) presented rootstock effect. Musts from R110 contained the highest concentrations of α-amino nitrogen (FAN = 128.1 mg/L) and ammoniacal nitrogen (NH₄⁺ = 98.7 mg/L), resulting in a mean YAN of 226.8 mg/L, significantly greater than all the other rootstocks (

Table 2). In contrast, 140Ru produced the lowest YAN (132.6 6 mg/L), with 3309C, 41B and FERCAL occupying intermediate positions (

Table 2). In a previous study, R110 also produced grapes with higher YAN compared to a low vigour rootstock (420A,

V. berlandieri×

V. riparia) in Cabernet Sauvignon [

35]. However, in a more recent study, R110 resulted in lower YAN and FAN compared to other rootstocks in Pinot noir [

28].

Rootstock effects on nitrogen levels recorded on the plant and grapes may derive from variations in root system architecture, nutrient uptake efficiency, and the allocation and remobilization of nitrogen within the vine. These differences can influence both the timing of ripening and the overall nutrient balance of the scion, reflecting broader impacts on nutrient dynamics and vine physiological status [

36,

37].

3.2. Fermentation Duration and Kinetics

Fermentation kinetics varied among rootstocks. Although alcoholic fermentation progressed smoothly to dryness in all treatments, speed and duration differed according to rootstock. For each rootstock, the three biological replicates showed remarkable consistency with each other, both in rate and duration (

Figure 1). R110 and 3309C displayed the most rapid fermentations, reaching completion in approximately 9-10 days, while 41B and FERCAL required slightly longer (11-12 days). In contrast, 140Ru exhibited the slowest fermentation dynamics, extending to roughly 14 days. Differences in fermentation speed are likely to reflect the combined influence of yeast-assimilable nitrogen and sugar concentration as well as possible variations in the micronutrient profile imparted by each rootstock. Higher YAN levels, as observed in R110 musts, are generally associated with faster yeast growth and shorter fermentation times, whereas lower YAN, such as in 140Ru, can limit fermentation rate and result in prolonged completion [

15,

16,

38].

3.3. Wine Composition, Tannins and Nitrogen Status

Differences were detected on the chemical profile of the finished wines (

Table 3) and on residual nitrogen pools after fermentation (

Table 4). Alcoholic strength varied significantly among rootstocks, with wines from FERCAL showing the highest ethanol content (13.1 % vol) and those from 140Ru the lowest (10.2 % vol), with corresponding results in wine density. These differences are consistent with the variation in must sugar content at harvest and are likely to reflect rootstock effects on ripening rate and berry composition [

4,

20]. Residual sugar levels were generally low across all treatments, indicating that alcoholic fermentation progressed to completion in most cases. Acid-base attributes in the wines followed patterns already evident in the musts. Wines from 140Ru displayed the highest titratable acidity and lowest pH, while R110 wines exhibited the lowest acidity and highest pH. Such differences may be linked to rootstock-mediated variation in potassium uptake [

2]. Volatile acidity was distinctly higher in 140Ru wines, which may be associated with its lower initial YAN and sugar concentrations, conditions that may challenge yeast metabolism and increase acetic acid production (

Table 3).

Total tannin concentration in the finished wines was significantly influenced by rootstock. R110 wines contained the highest tannin level (0.375 g/L), whereas 41B and 140Ru produced the lowest tannin concentrations (0.167 g/L and 0.208 g/L, respectively). In a previous study, the levels of tannins in musts from own-rooted vines were significantly higher compared to all rootstocks but did not vary significantly among different rootstocks [

11]. As Assyrtiko is considered a white variety with remarkably high levels of tannins and total phenolics, the concentration of tannins as a result of vineyard conditions - including rootstock selection - is viticulturally and enologically meaningful. Differences in concentrations of tannins may arise from altered berry structure or phenolic biosynthesis. It is known that tannins and other phenolic compounds affect mouthfeel, oxidative stability and the potential for ageing [

39,

40,

41].

Residual nitrogen in the wines mirrored must nitrogen status and differed by rootstock (

Table 4). R110 wines retained the highest residual FAN (57.7 mg/L) and YAN (62.7 mg/L), while FERCAL wines retained the lowest residual nitrogen. These values reflect dynamics of nitrogen assimilation by yeast during fermentation as R110 had substantially higher initial YAN in the must, which explains both the fast fermentation rate and the larger residual pools after fermentation. The magnitude and timing of nitrogen uptake by yeast influence fermentation kinetics, aromatic compound formation and the risk of fermentation problems (Gobert et al., 2019; Onnetti et al., 2024). Overall, rootstocks that produced musts with higher YAN and sugar (e.g., R110 and 3309C) supported faster, more complete fermentations and yielded wines with higher alcohol, lower volatile acidity and greater residual FAN, while 140Ru -characterized by lower Baume and low must YAN - exhibited slower fermentation kinetics, lower alcohol and substantially elevated volatile acidity.

3.4. Sensory Profile

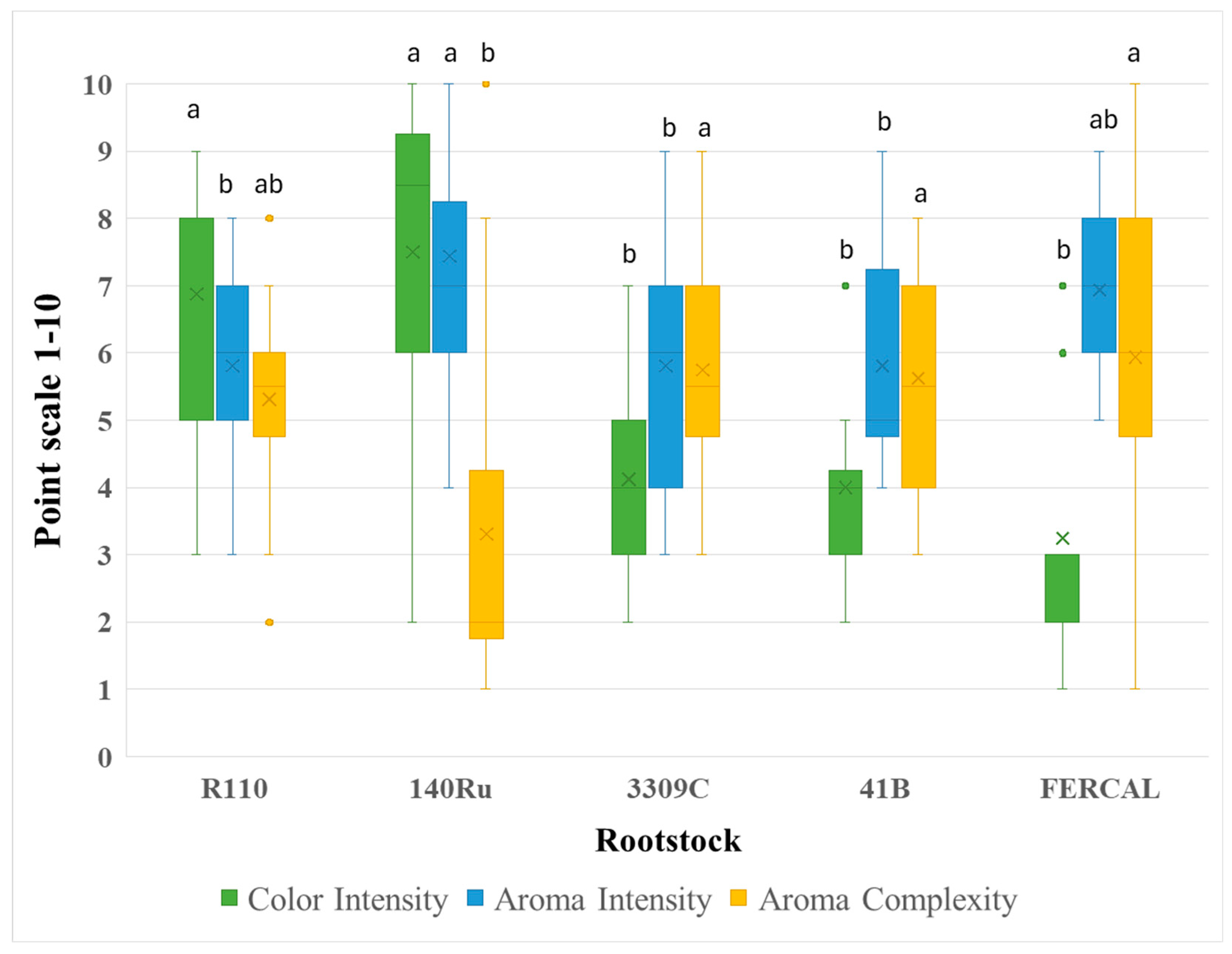

The sensory evaluation revealed significant differences in several wine organoleptic attributes. Colour intensity differed markedly among treatments (

p < 0.00001), with wines from 140Ru clearly presenting a darker - brownish hue compared to all other wines. Aroma intensity (

p = 0.0104) and aroma complexity (

p = 0.0044) also varied significantly, with R110 and 3309C wines consistently achieving higher scores compared to the other rootstocks (

Figure 2). In contrast, perception of acidity (F₄,₇₅ = 0.751,

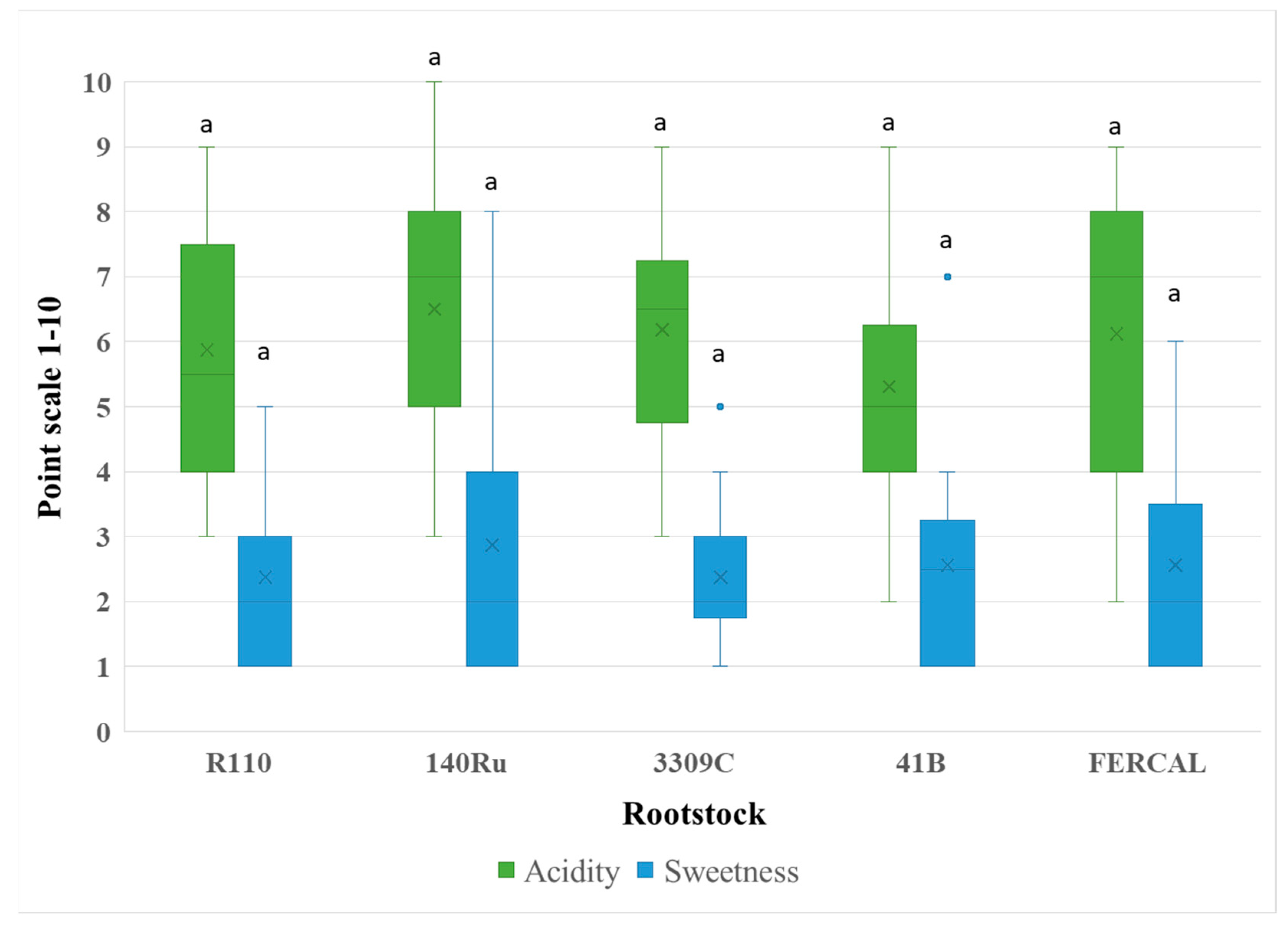

p = 0.5607) and perceived sweetness (F₄,₇₅ = 0.669,

p = 0.9076) did not differ significantly, indicating that these parameters were perceived by the panel as equally pronounced among different rootstocks, despite the measurable chemical differences detected in wine analysis (

Figure 3).

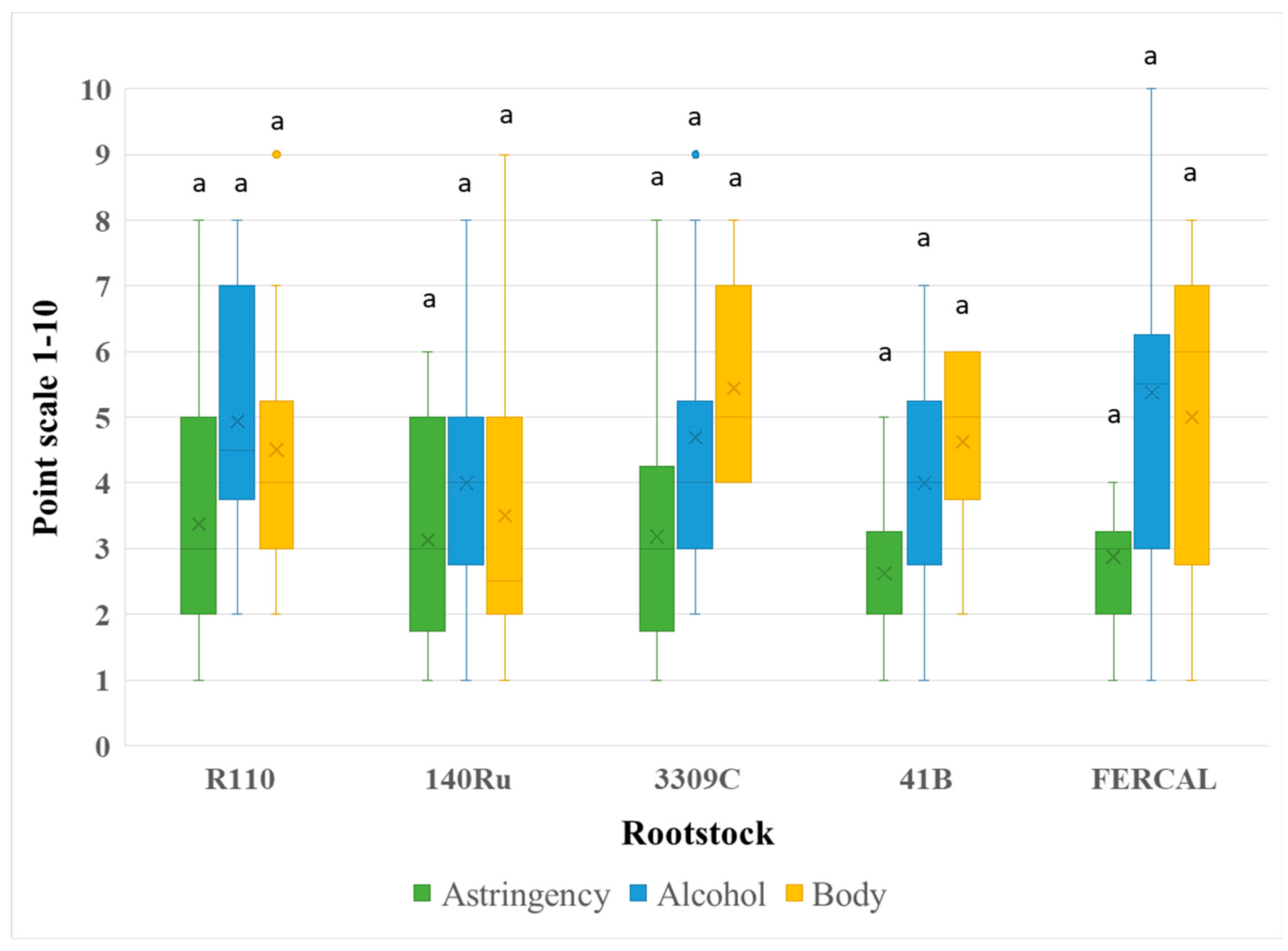

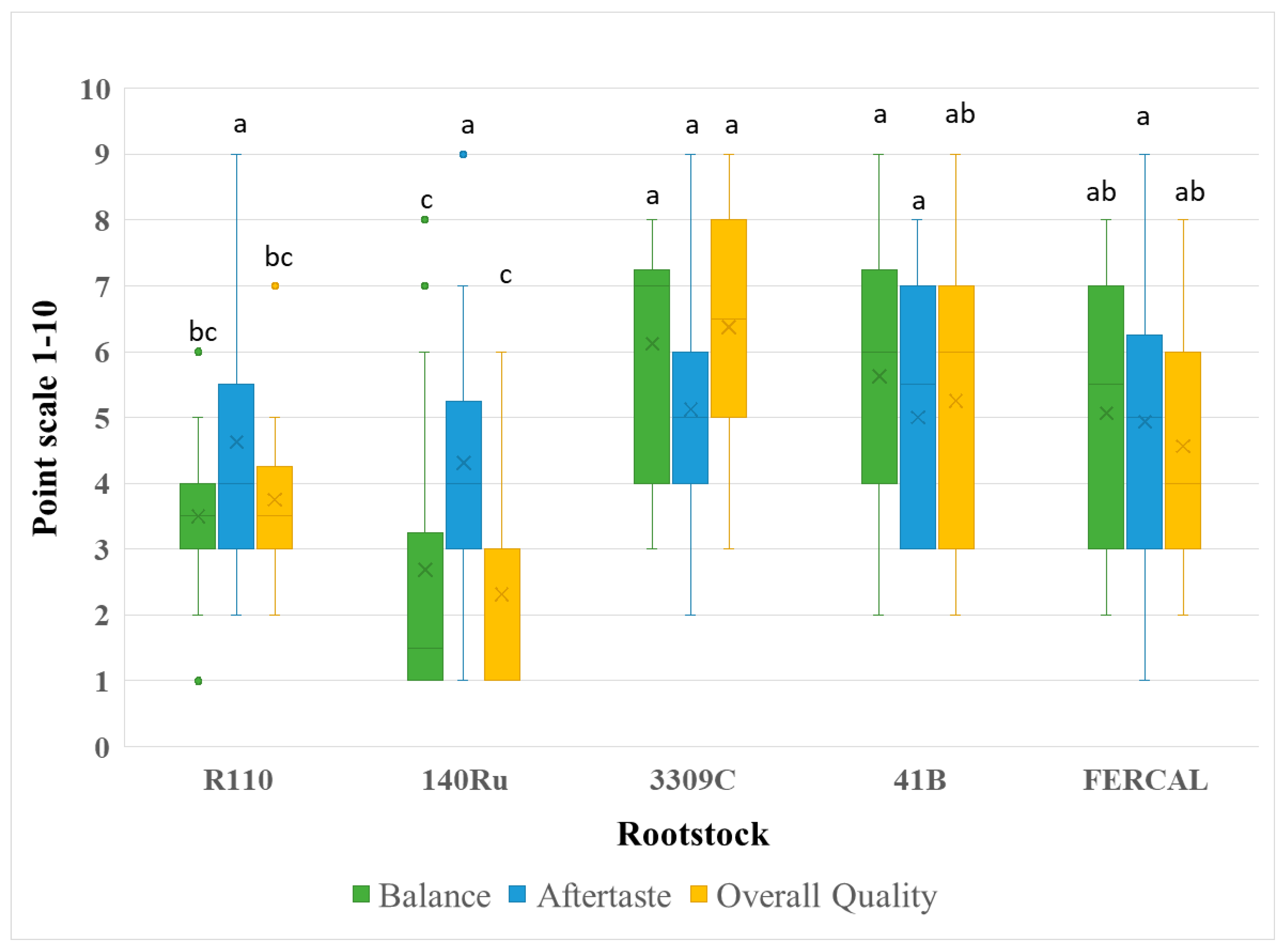

Astringency (F₄,₇₅ = 0.518,

p = 0.7230), perceived alcohol (F₄,₇₅ = 1.352,

p = 0.2589), and aftertaste (F₄,₇₅ = 0.411,

p = 0.8001) also showed no significant variation among rootstocks (

Figure 4). The same case was recorded in the perception of body/mouthfeel/viscosity (F₄,₇₅ = 2.232,

p = 0.0734), with R110 and 3309C scoring slightly higher. Significant effects were recorded for balance and overall quality (

P < 0.00001), where R110 and 3309C again ranked highest, suggesting a consistent panel preference for these wines (

Figure 5).

Wine organoleptic parameters in relation to different grapevine rootstocks have not been extensively studied and further examination is required to draw accurate conclusions. However, rootstock genotype seems to play an indirect - thought important - role in several wine characteristics. These characteristics unavoidably affect the sensory profile of the final wines [

42]. Therefore, certain rootstocks can serve as valuable tools in optimizing wine quality in specific winegrape cultivars. Assyrtiko is well-known for producing exceptional white wines, as own-rooted, in the volcanic terroir of Santorini [

27]. However, the effect of different rootstocks on its quality attributes had not been investigated. In the present study, while 140Ru produced Assyrtiko wines with comparatively lower scores for aroma and balance, wines from R110 and 3309C consistently scored highest for overall quality. Panelists also detected greater aromatic complexity and balance in R110 wines. Although consistently performs poorly in yield components, R 110 seems to enhance grape and wine quality. This evidence is also supported by the study of Olarte Mantilla et al. [

24] who found that Syrah wines from R110 presented greater sensory characteristics compared to other rootstocks and own-rooted vines. Overall, these results align with recent findings showing that rootstock selection may influence sensory outcomes by modulating grape composition, acid-sugar balance, and phenolic content, key parameters shaping aromatic expression, structural harmony, and perceived quality [

42,

43,

44].

5. Conclusions

Rootstock genotype had a marked effect on the nitrogen status and chemical composition of musts and wines from Vitis vinifera cv. Assyrtiko, as well as on certain sensory attributes of the resulting wines. Assyrtiko is renowned for producing world-class wines when grown on its own roots in the phylloxera-resistant volcanic terroir of Santorini. However, as its cultivation expands to diverse regions in Greece and abroad, there is an increasing need to assess its compatibility and interactions with phylloxera-resistant American rootstocks. The findings of this study highlight rootstock selection as a valuable viticultural tool for shaping wine style and ensuring the high-quality standards associated with Assyrtiko. Further research is needed to broaden the range of tested combinations and explore rootstock-scion interactions that may underline the chemical and sensory outcomes documented in the present study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.B. A.E. and E.K.; methodology, A.E., E.B., M.P. and V.K.; software, E.B., M.P., V.K.; validation, G.B. and E.K.; formal analysis, E.B., M.P., V.K. and A.E.; investigation, E.B., A.E. and G.B.; resources, E.K.; data curation, E.B. and A.E.; writing—original draft preparation, E.B., A.E., M.P. and V.K.; writing—review and editing, E.B., A.E. and G.B.; visualization, M.P. and V.K.; supervision, E.B., G.B. and E.K.; project administration, E.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all panelists involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data derived from this study are presented within the article. Raw data are available upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- Arnold, C.; Schnitzler, A. Ecology and Genetics of Natural Populations of North American Vitis Species Used as Rootstocks in European Grapevine Breeding Programs. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gautier, A.; Cookson, S.J.; Lagalle, L.; Ollat, N.; Marguerit, E. Influence of the Three Main Genetic Backgrounds of Grapevine Rootstocks on Petiolar Nutrient Concentrations of the Scion, with a Focus on Phosphorus. OENO One 2020, 54, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granett, J.; Walker, M.A.; Kocsis, L.; Omer, A.D. Biology and Management of Grape Phylloxera. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2001, 46, 387–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimek, K.; Kapłan, M.; Najda, A. Influence of Rootstock on Yield Quantity and Quality, Contents of Biologically Active Compounds and Antioxidant Activity in Regent Grapevine Fruit. Molecules 2022, 27, 2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ollat, N.; Peccoux, A.; Papura, D.; Esmenjaud, D.; Marguerit, E.; Tandonnet, J.P.; Delrot, S. Rootstocks as a Component of Adaptation to Environment. In Grapevine in a Changing Environment. In Grapevine in a Changing Environment; Gerós, A., Chaves, M., Gil, H., Delrot, S., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 68–108. [Google Scholar]

- Warschefsky, E.J.; Klein, L.; Frank, M.H.; Chitwood, D.H.; Londo, J.P.; von Wettberg, E.J.; Miller, A.J. Rootstocks: Diversity, Domestication, and Impacts on Shoot Phenotypes. Trends Plant Sci. 2016, 21, 418–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferris, H.; Zheng, L.; Walker, M.A. Resistance of Grape Rootstocks to Plant-Parasitic Nematodes. J. Nematol. 2012, 44, 377–386. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner, K.; Rizzo, D.M. Relative Resistance of Grapevine Rootstocks to Armillaria Root Disease. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2006, 57, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darriaut, R.; Lailheugue, V.; Masneuf-Pomarède, I.; Marguerit, E.; Martins, G.; Compant, S.; Ballestra, P.; Upton, S.; Ollat, N.; Lauvergeat, V. Grapevine Rootstock and Soil Microbiome Interactions: Keys for a Resilient Viticulture. Hortic.Res. 2022, 9, uhac019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhu, C.; Sun, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, S.; Shi, W.; Wang, W.; Zhao, B. Influence of Rootstock on Endogenous Hormones and Color Change in Cabernet Sauvignon Grapes. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 6608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbertson, J.F.; Keller, M. Rootstock Effects on Deficit-Irrigated Winegrapes in a Dry Climate: Grape and Wine Composition. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2012, 63, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Skinkis, P.A. Oregon ‘Pinot Noir’ Grape Anthocyanin Enhancement by Early Leaf Removal. Food Chem. 2013, 139, 893–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, R.R.; Blackmore, D.H.; Clingeleffer, P.R.; Correll, R.L. Rootstock effects on salt tolerance of irrigated field-grown grapevines (Vitis vinifera L. cv. Sultana): I. Yield and vigour inter-relationships. Austral. J. Grape Wine Res. 2002, 8, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, I.; Strever, A.; Myburgh, P.A.; Deloire, A. The interaction between rootstocks and cultivars (Vitis vinifera L.) to enhance drought tolerance in grapevine. Austral. J. Grape Wine Res. 2014, 20, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobert, A.; Tourdot-Maréchal, R.; Sparrow, C.; Morge, C.; Alexandre, H. Influence of Nitrogen Status in Wine Alcoholic Fermentation. Food Microbiol. 2019, 83, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.J.; Henschke, P.A. Implications of Nitrogen Nutrition for Grapes, Fermentation and Wine. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2005, 11, 242–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godillot, J.; Sanchez, I.; Perez, M.; Picou, C.; Galeote, V.; Sablayrolles, J.M.; Farines, V.; Mouret, J.R. The Timing of Nitrogen Addition Impacts Yeast Genes Expression and the Production of Aroma Compounds during Wine Fermentation. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 829786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, M.; Mills, L.J.; Harbertson, J.F. Rootstock Effects on Deficit-Irrigated Winegrapes in a Dry Climate: Vigor, Yield Formation, and Fruit Ripening. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2012, 63, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, M. , Tittmann, S., Ben Ghozlen, N. & Stoll, M. (2018). Grapevine rootstocks result in differences in leaf composition (Vitis vinifera L. cv. Pinot noir) detected through non-invasive fluorescence sensor technology. Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research, 24. [CrossRef]

- Lecourt, J.; Lauvergeat, V.; Ollat, N.; Vivin, P.; Cookson, S.J. Shoot and Root Ionome Responses to Nitrate Supply in Grafted Grapevines Are Rootstock Genotype Dependent. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2015, 21, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochetel, N.; Escudié, F.; Cookson, S.J.; Dai, Z.; Vivin, P.; Bert, P.F.; Muñoz, M.S.; Delrot, S.; Klopp, C.; Ollat, N.; Lauvergeat, V. Root Transcriptomic Responses of Grafted Grapevines to Heterogeneous Nitrogen Availability Depend on Rootstock Genotype. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 4339–4355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdeja, M.; Hilbert, G.; Wu, D.Z.; Lafontaine, M.; Stoll, M.; Schultz, H.R.; Delrot, S. Effect of Water Stress and Rootstock Genotype on Pinot Noir Berry Composition. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2014, 20, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miele, A.; Rizzon, L.A. Rootstock-Scion Interaction: Effect on the Composition of Cabernet Sauvignon Grape Must. Rev. Bras. Frutic. 2017, 39, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olarte Mantilla, S.M.; Collins, C.; Iland, P.G.; Kidman, C.M.; Ristic, R.; Boss, P.K.; Jordans, C.; Bastian, S.E. Shiraz (Vitis vinifera L.) Berry and Wine Sensory Profiles and Composition Are Modulated by Rootstocks. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2018, 69, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilanova, M.; Genisheva, Z.; Tubío, M.; Álvarez, K.; Lissarrague, J.R.; Oliveira, J.M. Rootstock Effect on Volatile Composition of Albariño Wines. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 2135–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karampatea, A.; Vrentzou, E.; Skendi, A.; Bouloumpasi, E. Effect of Vineyard Location on Assyrtiko Grape Ripening in Santorini and Its Wine’s Characteristics. Biol. Life Sci. Forum 2024, 40, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgouros, G.; Mallouchos, A.; Dourou, D.; Banilas, G.; Chalvantzi, I.; Kourkoutas, Y.; Nisiotou, A. Torulaspora delbrueckii May Help Manage Total and Volatile Acidity of Santorini-Assyrtiko Wine in View of Global Warming. Foods 2023, 12, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, M.; Samer, S.; Stoll, M. Grapevine Rootstock Genotypes Influence Berry and Wine Phenolic Composition (Vitis vinifera L. cv. Pinot Noir). OENO One 2022, 56, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OIV - International Organisation of Vine and Wine. OIV - International Organisation of Vine and Wine. Compendium of International Methods of Wine and Must Analysis; International Organization of Vine and Wine: Paris, France. Compendium of International Methods of Wine and Must Analysis; International Organization of Vine and Wine: Paris. Available online: https://www.oiv.int/ (accessed on 18 November 2024).

- Wilhelmy, C.; Pavez, C.; Bordeu, E.; Brossard, N. A Review of Tannin Determination Methods Using Spectrophotometric Detection in Red Wines and Their Ability to Predict Astringency. S. Afr. J. Enol. Vitic. 2021, 42, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duke, B.C.; Butzke, C.E. Rapid Determination of Primary Amino Acids in Grape Juice Using an o-Phthaldialdehyde/N-Acetyl-L-Cysteine Spectrophotometric Assay. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1998, 49, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corso, M.; Vannozzi, A.; Ziliotto, F.; Zouine, M.; Maza, E.; Nicolato, T.; Moser, C. Grapevine Rootstocks Differentially Affect the Rate of Ripening and Modulate Auxin-Related Genes in Cabernet Sauvignon Berries. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, J.B.; Laureano, O.; de Castro, R.; Pereira, G.E.; Ricardo-Da-Silva, J.M. Rootstock and harvest season affect the chemical composition and sensory analysis of grapes and wines of the Alicante Bouschet (Vitis vinifera L.) grown in a tropical semi-arid climate in Brazil. OENO One 2020, 54, 1021–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambetta, G.A.; Manuck, C.M.; Drucker, S.T.; Shaghasi, T.; Fort, K.; Matthews, M.A.; Walker, M.A.; McElrone, A.J. The Relationship between Root Hydraulics and Scion Vigour across Vitis Rootstocks: What Role Do Root Aquaporins Play? J. Exp. Bot. 2012, 63, 6445–6455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Steenwerth, K.L. Rootstock and Vineyard Floor Management Influence on ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ Grape Yeast Assimilable Nitrogen (YAN). Food Chem. 2011, 127, 926–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdenal, T.; Dienes-Nagy, Á.; Spangenberg, J.E.; Zufferey, V.; Spring, J.-L.; Viret, O.; Marin-Carbonne, J.; van Leeuwen, C. Understanding and Managing Nitrogen Nutrition in Grapevine: A Review. OENO One 2021, 55, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaou, N.; Koukourikou, M.A.; Karagiannidis, N. Effects of Various Rootstocks on Xylem Exudates Cytokinin Content, Nutrient Uptake, and Growth Patterns of Grapevine Vitis vinifera L. cv. Thomson Seedless. Agronomy 2000, 20, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onetto, C.; McCarthy, J.; Solomon, M.; Borneman, A.R.; Schmidt, S.A. Enhancing Fermentation Performance through the Reutilisation of Wine Yeast Lees. OENO One 2024, 58, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiner, R.P.; Scagel, C.F.; Lee, J. N, P, and K Supply to Pinot Noir Grapevines: Impact on Berry Phenolics and Free Amino Acids. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2014, 65, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkytė, V.; Longo, E.; Windisch, G.; Boselli, E. Phenolic Compounds as Markers of Wine Quality and Authenticity. Foods 2020, 9, 1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.A.; Ferrier, J.; Harbertson, J.F.; des Gachons, C.P. Analysis of Tannins in Red Wine Using Multiple Methods: Correlation with Perceived Astringency. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2006, 57, 481–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller-Fuenzalida, F.; Cuneo, I.F.; Kuhn, N.; Peña-Neira, Á.; Cáceres-Mella, A. Rootstock Effect Influences the Phenolic and Sensory Characteristics of Syrah Grapes and Wines in a Mediterranean Climate. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feifel, S.; Zimmermann, D.; Schaub, M.; Wegmann-Herr, P.; Richling, E.; Durner, D. Influence of Grape Maturity and Maceration Time on Sensory Characteristics and Phenolics in Pinot Noir and Cabernet-Sauvignon Wines. OENO One 2025, 59, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medel-Marabolí, M.; López-Solís, R.; Vásquez-Cerda, M.; Seguel-Rubio, E.; Gil-Cortiella, M.; Seguel-Seguel, O.; Obreque-Slier, E. Grapevine Rootstocks Mediate the Effects of Soil Salinity on Physicochemical and Sensory Properties of Cabernet Sauvignon Grapes and Wines. Appl. Food Res. 2025, 5, 101073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Fermentation durations and kinetics of Assyrtiko microvinifications, from grapes that derived from the rootstocks: R110 (A), 140Ru (B), 3309C (C), 41B (D) and FERCAL (E).

Figure 1.

Fermentation durations and kinetics of Assyrtiko microvinifications, from grapes that derived from the rootstocks: R110 (A), 140Ru (B), 3309C (C), 41B (D) and FERCAL (E).

Figure 2.

Fermentation Sensory evaluation regarding Color Intensity, Aroma Intensity, and Aroma Complexity of Assyrtiko wines from five different rootstocks. Box plots depict the distribution of panel scores on a 1–10 scale, with the × symbol representing the mean value. Outliers are plotted as individual points. Different lowercase letters denote statistically significant differences among rootstocks for each parameter (p < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Fermentation Sensory evaluation regarding Color Intensity, Aroma Intensity, and Aroma Complexity of Assyrtiko wines from five different rootstocks. Box plots depict the distribution of panel scores on a 1–10 scale, with the × symbol representing the mean value. Outliers are plotted as individual points. Different lowercase letters denote statistically significant differences among rootstocks for each parameter (p < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Sensory evaluation regarding perceived Acidity and Sweetness of Assyrtiko wines from five different rootstocks. Box plots depict the distribution of panel scores on a 1–10 scale, with the × symbol representing the mean value. Outliers are plotted as individual points. Different lowercase letters denote statistically significant differences among rootstocks for each parameter (p < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Sensory evaluation regarding perceived Acidity and Sweetness of Assyrtiko wines from five different rootstocks. Box plots depict the distribution of panel scores on a 1–10 scale, with the × symbol representing the mean value. Outliers are plotted as individual points. Different lowercase letters denote statistically significant differences among rootstocks for each parameter (p < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Sensory evaluation regarding Astrigency, Alcohol, and Body (mouthfeel/viscosity) of Assyrtiko wines from five different rootstocks. Box plots depict the distribution of panel scores on a 1–10 scale, with the × symbol representing the mean value. Outliers are plotted as individual points. Different lowercase letters denote statistically significant differences among rootstocks for each parameter (p < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Sensory evaluation regarding Astrigency, Alcohol, and Body (mouthfeel/viscosity) of Assyrtiko wines from five different rootstocks. Box plots depict the distribution of panel scores on a 1–10 scale, with the × symbol representing the mean value. Outliers are plotted as individual points. Different lowercase letters denote statistically significant differences among rootstocks for each parameter (p < 0.05).

Figure 5.

Sensory evaluation regarding Balance, Aftertaste, and Overall Quality of Assyrtiko wines from five different rootstocks. Box plots depict the distribution of panel scores on a 1–10 scale, with the × symbol representing the mean value. Outliers are plotted as individual points. Different lowercase letters denote statistically significant differences among rootstocks for each parameter (p < 0.05).

Figure 5.

Sensory evaluation regarding Balance, Aftertaste, and Overall Quality of Assyrtiko wines from five different rootstocks. Box plots depict the distribution of panel scores on a 1–10 scale, with the × symbol representing the mean value. Outliers are plotted as individual points. Different lowercase letters denote statistically significant differences among rootstocks for each parameter (p < 0.05).

Table 1.

Must composition of Assyrtiko grafted onto five different rootstocks. Each value represents mean ± SE. Different letters within the same column indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) among rootstocks.

Table 1.

Must composition of Assyrtiko grafted onto five different rootstocks. Each value represents mean ± SE. Different letters within the same column indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) among rootstocks.

| Rootstock |

˚Baume |

Density

(g/L) |

Titratable acidity

(g/L) |

pH |

| R110 |

12.5±0.0c

|

1.0925±0.02b

|

4.70±0.1ab

|

4.25±0.00a

|

| 140Ru |

11.7±0.0d

|

1.0866±0.01c

|

4,88±0.1a

|

4.13±0.01b

|

| 3309C |

12.4±0.0c

|

1.0927±0.02b

|

4.48±0.1b

|

4.07±0.00c

|

| 41B |

12.6±0.0b

|

1.0955±0.01a

|

4.93±0.2a

|

4.01±0.01d

|

| FERCAL |

12.8±0.0a

|

1.0950±0.01a

|

4.90±0.0a

|

4.07±0.01c

|

|

p-value

|

˂ 0.00001

|

˂ 0.00001

|

0.0089

|

˂ 0.00001

|

Table 2.

Nitrogen grape juice status of Assyrtiko grafted onto five different rootstocks. Each value represents mean ± SE. Different letters within the same column indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) among rootstocks.

Table 2.

Nitrogen grape juice status of Assyrtiko grafted onto five different rootstocks. Each value represents mean ± SE. Different letters within the same column indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) among rootstocks.

| Rootstock |

α-Amino nitrogen (FAN) (mg/L) |

Ammoniacal N (NH₄⁺) (mg/L) |

YAN (FAN + NH₄⁺) (mg/L) |

| R110 |

128.1±0.7a

|

98.7±0.3a

|

226.80±0.99a

|

| 140Ru |

65.3±0.9b

|

67.3±0.4d

|

132.60±0.46c

|

| 3309C |

76.19±10.0b

|

75.8±2.9c

|

151.99±12.87bc

|

| 41B |

77.5±8.9b

|

90.7±0.3b

|

122.20±8.66bc

|

| FERCAL |

88.78±8.53b

|

89.9±1.1b

|

178.68±9.63b

|

|

p-value

|

0.0009

|

˂ 0.00001

|

0.0001

|

Table 3.

Oenological analyses of Assyrtiko wines from plants grafted onto five different rootstocks. Each value represents mean ± SE. Different letters within the same column indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) among rootstocks.

Table 3.

Oenological analyses of Assyrtiko wines from plants grafted onto five different rootstocks. Each value represents mean ± SE. Different letters within the same column indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) among rootstocks.

| Rootstock |

Density

(g/L) |

Titratable acidity (g/L) |

pH |

Volatile acidity (g/L) |

Alcohol

(%vol) |

Reducing sugars (g/L) |

Total Tannins (g/L) |

| R110 |

0.9896±0.01b

|

3.93±0.1c

|

4.20±0.00a

|

0.27±0.01c |

12.8±0.0b

|

1.2±0.0abc

|

0.375±0.00a

|

| 140Ru |

0.9951±0.01a

|

5.23±0.1a

|

3.80±0.00e

|

0.98±0.00a

|

10.2±0.1c

|

1.3±0.1ab

|

0.208±0.00c

|

| 3309C |

0.9883±0.01c

|

3.45±0.1c

|

3.90±0.00d

|

0.31±0.01b

|

12.7±0.1b

|

1.4±0.1a

|

0.292±0.00b

|

| 41B |

0.9893±0.02b

|

4.68±0.2ab

|

3.97±0.00b

|

0.23±0.00d

|

12.9±0.0ab

|

1.1±0.0bc

|

0.167±0.00d

|

| FERCAL |

0.9883±0.00c

|

4.55±0.1b

|

3.95±0.00c

|

0.20±0.01e

|

13.1±0.1a

|

1.0±0.1c

|

0.220±0.02c

|

|

p-values

|

˂ 0.00001

|

˂ 0.00001

|

˂ 0.00001

|

˂ 0.00001

|

˂ 0.00001

|

0.0087

|

˂ 0.00001

|

Table 4.

Nitrogen status of wines from Assyrtiko grafted onto five different rootstocks. Each value represents mean ± SE. Different letters within the same column indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) among rootstocks.

Table 4.

Nitrogen status of wines from Assyrtiko grafted onto five different rootstocks. Each value represents mean ± SE. Different letters within the same column indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) among rootstocks.

| Rootstock |

α-Amino nitrogen (FAN) (mg/L) |

Ammoniacal N (NH₄⁺) (mg/L) |

YAN (FAN + NH₄⁺) (mg/L) |

| R110 |

57.73±0.37a

|

4.94±0.16a

|

62.67±0.53a

|

| 140Ru |

41.09±5.54b

|

2.51±0.23c

|

43.60±5.31b

|

| 3309C |

32.73±2.43bc

|

3.79±0.21b

|

36.52±2.21bc

|

| 41B |

27.07±3.86bc

|

3.62±0.10b

|

30.69±3.94bc

|

| FERCAL |

18.25±0.83c

|

4.76±0.01a

|

23.02±0.83c

|

|

p-value

|

0.00007

|

˂ 0.00001

|

0.00005

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).