Submitted:

19 August 2025

Posted:

21 August 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

How is Heterogeneity Measured?

The Q Statistic

The I2 Statistic

The τ2 Statistic

- DerSimonian–Laird (DL). The most widely known and historically the default [9]. It is simple—plugging the observed Q into a formula—but biased: with few studies or large true heterogeneity, it tends to underestimate τ2, pulling values toward zero and giving overly narrow confidence intervals. Given its well-documented biases, the DL estimator should no longer be regarded as the default choice in modern meta-analysis.

- Restricted maximum likelihood (REML). Now considered the standard [10,11]. Unlike DL, it iteratively searches for the τ2 that makes the observed results most plausible under a random-effects model. This reduces bias and produces more reliable estimates, especially in small meta-analyses or when heterogeneity is substantial.

- Paule–Mandel. Another estimator that, like REML. Although classical, improves over DL and is currently accepted as a REML alternative.

- Bayesian estimators. In Bayesian statistics, τ2 is not treated as a fixed number but as something uncertain, described by a probability distribution. We start with a prior (what we already know or assume) and update it with the data to get a posterior (what seems plausible after seeing the evidence) [12]. The advantage is that we can make direct probability statements, like “there is a 70% chance that heterogeneity is above a clinically important level.” This approach is flexible, especially when data are scarce, but the results depend on how the prior is chosen, so it must be done transparently.

Prediction Intervals: An Extension of τ2

Which Statistic Matters Most: Q, I2, or τ2?

|

But do these conventional metrics of heterogeneity apply equally to diagnostic accuracy studies? In therapeutic meta-analysis, heterogeneity is usually unidimensional: all studies estimate the same type of effect. Diagnostic test accuracy (DTA) is different. Here two outcomes—sensitivity and specificity—must be analyzed together, because they are linked by the diagnostic threshold. Raising the threshold makes specificity climb but sensitivity fall; lowering it has the opposite effect. This correlation means that univariate pooling of sensitivity or specificity is misleading. Instead, hierarchical random-effects models—the bivariate model and the hierarchical summary ROC (HSROC)—are required [16,17,18]. Interpretation. In DTA meta-analysis, heterogeneity is described by the τ2 for sensitivity and specificity, plus a correlation parameter that captures threshold effects. Unlike intervention reviews, where Q, I2, or τ2 summarize a single outcome, diagnostic data are inherently bivariate. Applying univariate statistics such as Q or I2 to sensitivity or specificity alone ignores this structure and often exaggerates or misrepresents heterogeneity. Metrics like the bivariate I2 proposed by Zhou et al. [19] have been suggested, but the most robust approach is to interpret the variance and correlation parameters yielded directly by hierarchical models, as these respect the joint nature of accuracy data. Limitations. Quantifying heterogeneity in DTA is inherently more complex than in intervention reviews. Even when hierarchical models are used, estimates of τ2 (Se), τ2 (Sp), and threshold correlation become unstable with few studies, producing wide or imprecise variance estimates. This makes heterogeneity harder to measure, yet also more crucial, because threshold-driven differences are often the main source of inconsistency in diagnostic accuracy research [20]. |

So, We Found Heterogeneity. What Now?

How Much?

Where from?

- If differences arise from valid but diverse contexts, pooling may be reasonable, provided conclusions are nuanced.

- If differences stem from systematic flaws, pooling misleads, and sometimes the correct choice is not to pool at all.

Transparency, Reproducibility, and Caution

Conclusions

CRediT Author Statement

Ethical Statement

Original Work

Informed Consent

AI Use Disclosure

Data Availability Statement

Conflict of Interest

References

- Cochran, W.G. The Combination of Estimates from Different Experiments. Biometrics 1954, 10, 101–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mood AM, Graybill FA, Boes DC. Introduction to the Theory of Statistics. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1974.

- Casella G, Berger RL. Statistical Inference. 2nd ed. Duxbury Press; 2002.

- Hoaglin, D.C. Misunderstandings about Q and ‘Cochran's Q test' in meta-analysis. Stat. Med. 2015, 35, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thompson, S.G. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat. Med. 2002, 21, 1539–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.5 (updated 24). Cochrane, 2024. Available from www.cochrane.org/handbook. 20 August.

- von Hippel, P.T. The heterogeneity statistic I2 can be biased in small meta-analyses. BMC Med Res. Methodol. 2015, 15, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DerSimonian, R.; Laird, N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin. Trials 1986, 7, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viechtbauer, W. Bias and Efficiency of Meta-Analytic Variance Estimators in the Random-Effects Model. J. Educ. Behav. Stat. 2005, 30, 261–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veroniki, A.A.; Jackson, D.; Viechtbauer, W.; Bender, R.; Bowden, J.; Knapp, G.; Kuss, O.; Higgins, J.P.; Langan, D.; Salanti, G. Methods to estimate the between-study variance and its uncertainty in meta-analysis. Res. Synth. Methods 2015, 7, 55–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thompson, S.G.; Spiegelhalter, D.J. A Re-Evaluation of Random-Effects Meta-Analysis. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A (Statistics Soc. 2008, 172, 137–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riley, R.D.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Deeks, J.J. Interpretation of random effects meta-analyses. BMJ 2011, 342, d549–d549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagashima, K.; Noma, H.; A Furukawa, T. Prediction intervals for random-effects meta-analysis: A confidence distribution approach. Stat. Methods Med Res. 2018, 28, 1689–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IntHout, J.; A Ioannidis, J.P.; Rovers, M.M.; Goeman, J.J. Plea for routinely presenting prediction intervals in meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e010247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitsma, J.B.; Glas, A.S.; Rutjes, A.W.; Scholten, R.J.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Zwinderman, A.H. Bivariate analysis of sensitivity and specificity produces informative summary measures in diagnostic reviews. J. Clin. Epidemiology 2005, 58, 982–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutter, C.M.; Gatsonis, C.A. A hierarchical regression approach to meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy evaluations. Stat. Med. 2001, 20, 2865–2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbord, R.M.; Deeks, J.J.; Egger, M.; Whiting, P.; Sterne, J.A.C. A unification of models for meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy studies. Biostatistics 2006, 8, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Dendukuri, N. Statistics for quantifying heterogeneity in univariate and bivariate meta-analyses of binary data: The case of meta-analyses of diagnostic accuracy. Stat. Med. 2014, 33, 2701–2717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeks, J.J.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Leeflang, M.M.; Takwoingi, Y. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Diagnostic Test Accuracy. Version 2.0 (updated 23). Cochrane. 2023. Available on: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook-diagnostic-test-accuracy/current. 20 July.

- Oxman, A.D.; Guyatt, G.H. A Consumer's Guide to Subgroup Analyses. Ann. Intern. Med. 1992, 116, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viechtbauer, W.; Cheung, M.W.-L. Outlier and influence diagnostics for meta-analysis. Res. Synth. Methods 2010, 1, 112–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.; Wang, J.; Lin, L.; Wu, C. Sensitivity analysis with iterative outlier detection for systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Stat. Med. 2024, 43, 1549–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.G.; Higgins, J.P.T. How should meta-regression analyses be undertaken and interpreted? Stat. Med. 2002, 21, 1559–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baujat, B.; Mahé, C.; Pignon, J.; Hill, C. A graphical method for exploring heterogeneity in meta-analyses: application to a meta-analysis of 65 trials. Stat. Med. 2002, 21, 2641–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbraith, R.F. A note on graphical presentation of estimated odds ratios from several clinical trials. Stat. Med. 1988, 7, 889–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L'ABbé, K.A.; Detsky, A.S.; O'ROurke, K. Meta-Analysis in Clinical Research. Ann. Intern. Med. 1987, 107, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.; Egger, M. Funnel plots for detecting bias in meta-analysis: Guidelines on choice of axis. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2001, 54, 1046–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egger, M.; Smith, G.D.; Schneider, M.; Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997, 315, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Begg, C.B.; Mazumdar, M. Operating Characteristics of a Rank Correlation Test for Publication Bias. Biometrics 1994, 50, 1088–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

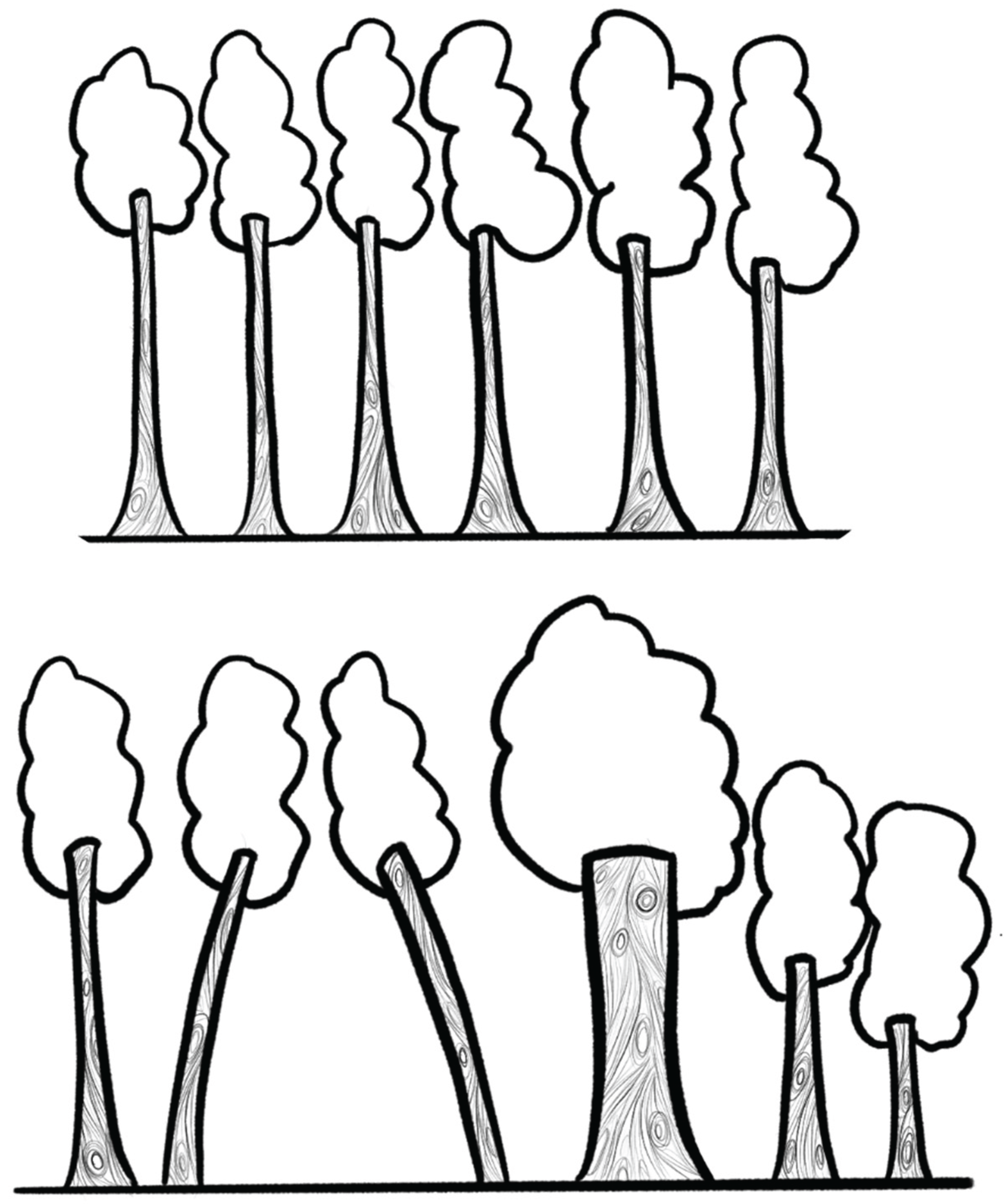

| Measure | What it measures | How it works | Strengths | Limitations | Forest metaphor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q (Cochran’s Q) | Tests if variability between studies is greater than chance alone | χ2 test, df = n–1 | Simple, widely implemented | Low power with few studies; too sensitive with many; only a test (yes/no) | Spotting whether the grove looks uneven at all |

| I2 (Higgins & Thompson) | Proportion of observed variability due to real heterogeneity (not chance) | Derived from Q and df | Intuitive %, widely reported | Distorted with very small/large studies; unstable with few studies; does not tell absolute size | What fraction of the leaning goes beyond natural randomness |

| τ2 (tau-squared) | Between-study variance (absolute amount of heterogeneity) | Estimated via formulas (DL, REML, etc.) | Gives scale of dispersion in same units as effect size | Harder to interpret; estimator-dependent; unstable with few studies | How much the trunks lean (a few degrees vs. 40°) |

| Prediction Interval (PI) | Likely range of true effects in a new study | Extends random-effects model using τ2 | Adds realism: shows what to expect in future contexts | Wide intervals with few studies; often omitted in practice | Walking deeper: what leaning we may see in the next part of the forest |

| DTA: Univariate Q/I2 | Applied separately to sensitivity (Se) and specificity (Sp) | Same formulas as above, but only for one dimension | Easy, familiar | Misleading: ignores correlation Se–Sp, inflates heterogeneity | Looking only east–west, ignoring north–south bends |

| DTA: Bivariate model (Reitsma) | Joint modeling of Se & Sp with correlation (ρ) | Bivariate random-effects linear mixed model on the logit scale of sensitivity and specificity. | Preserves correlation; handles threshold | Requires more data; computationally heavier | Viewing forest in 2D, not one axis |

| DTA: HSROC (Rutter & Gatsonis) | Models accuracy across thresholds | Curve-based hierarchical model | Captures threshold explicitly | Less intuitive for clinicians; complex | Not just leaning trunks, but whole slope of the ground |

| DTA: Bivariate I2 (Zhou) | Extends I2 to joint Se–Sp space | Formula from bivariate variance-covariance | Provides “intuitive %” in DTA | Newer, less familiar, rarely in software defaults | Proportion of the mess in both directions simultaneously |

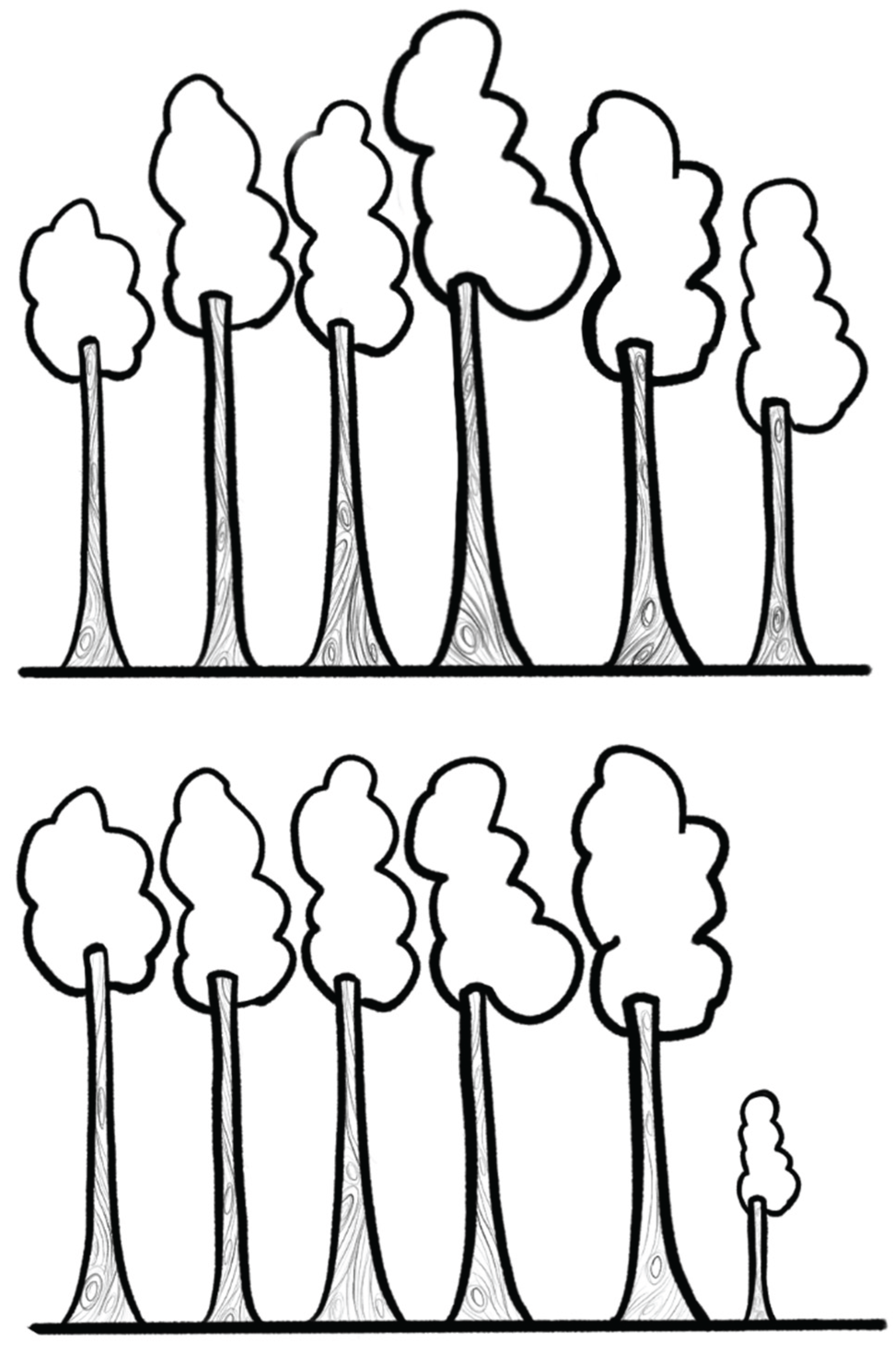

| Approach | Description | Forest Metaphor | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structured subgroup analysis | Compare effect sizes across categories (e.g., low vs. high RoB, RCT vs. observational). | Comparing clearings: do trees in rocky vs. fertile soil lean differently? | Easy to interpret; highlights clinically meaningful differences. | Strong assumptions; oversimplifies heterogeneity as binary; can be misleading if used alone. |

| Subgroup analysis: Sensitivity analyses | Explore robustness under different assumptions (e.g., estimators, corrections for zero events). | Testing different rulers to measure the same lean. | Reveals how assumptions affect results. | Can be misleading with sparse data; requires multiple studies; exploratory, not confirmatory. |

| Subgroup analysis: leave-one-out | Re-runs meta-analysis omitting one study at a time. | Temporarily removing one tree to see if the skyline changes. | Simple, widely implemented, shows robustness. | Harder to interpret; depends on scale of effect size; unstable with small number of studies. |

| Meta-regression | Relates effect size to study-level covariates (e.g., mean age, year, quality). | Putting on colored lenses—seeing if tilt changes with soil, wind, or slope. | Handles multiple covariates, quantifies trends. | Requires at least 10 studies per covariate |

| Prediction intervals | Estimates range of effect in a future study, considering heterogeneity. | Tells you what tilt angles you might encounter in the next grove. | Clinically meaningful, forward-looking. | Requires a reliable estimate of τ2, which can be difficult when there are only a few studies |

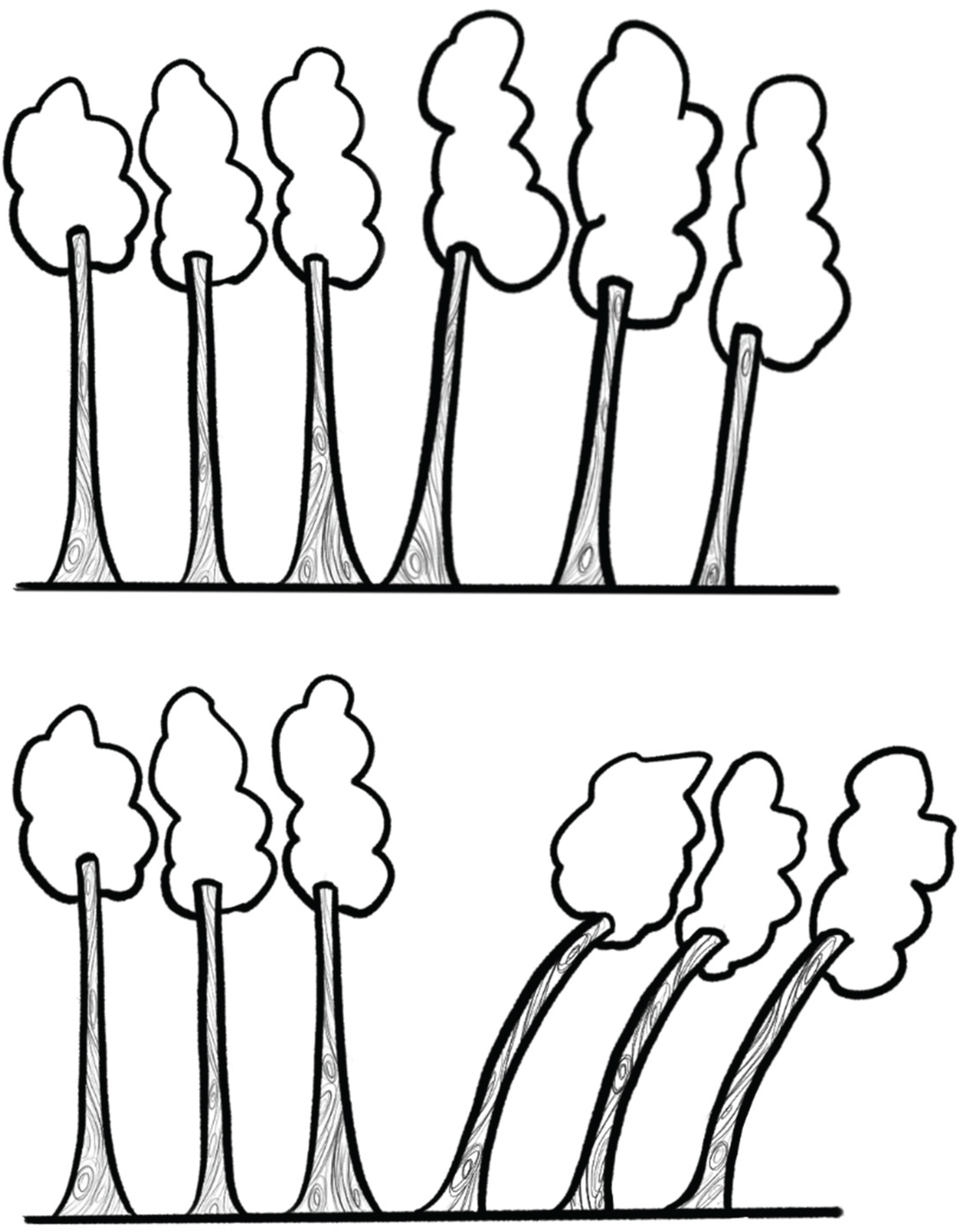

| Approach | Description | Forest Metaphor | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forest plot visual inspection | Visual inspection of confidence interval overlap across studies. | Looking at tree trunks: do their shadows overlap, or are they scattered apart? | Simple first step; immediately shows obvious dispersion. | Subjective; poor reliability when few studies are available. |

| Baujat plot | Plots each study’s contribution to overall heterogeneity (Q) against influence on effect size. | Spotting which trees lean most and distort the forest skyline. | Identifies outliers and influential studies. | Exploratory; requires enough studies; interpretation not always straightforward. |

| Galbraith (radial) plot | Plots standardized effect sizes against precision. | Like drawing rays from the forest center—outliers stand apart from the main bundle. | Highlights heterogeneity and small-study effects. | Assumes linearity; less intuitive for non-statisticians. |

| L’Abbé plot | Scatterplot of event rates in treatment vs. control groups across studies. | Two groves side by side: do trees from one lean consistently more than the other? | Good for binary outcomes; intuitive clinical insight. | Not suitable for continuous outcomes; harder to interpret with sparse data. |

| Funnel plot | Plots study effect size against precision to assess asymmetry (often for publication bias). | Like looking up at the treetops—symmetry suggests balance, asymmetry suggests something missing. | Can hint at bias or small-study effects; widely recognized. | Low power with few studies; asymmetry ≠ publication bias per se |

| Step | Recommended Action | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Test for Presence | Report Cochran’s Q statistic with degrees of freedom and p-value. | Provides a formal test, but acknowledge its limitations (low power with few studies, excessive sensitivity with many). |

| 2. Quantify Inconsistency | Report I2 together with its 95% confidence interval. | I2 quantifies the proportion of variability due to heterogeneity. The CI communicates the considerable uncertainty of this estimate. |

| 3. Quantify Magnitude | Report between-study variance (τ2) and specify the estimator used (e.g., REML). | τ2 measures the absolute magnitude of heterogeneity. Justify using a robust estimator (REML) over biased methods (DL). |

| 4. Assess Predictive Impact | Report the 95% Prediction Interval. | Translates heterogeneity into a clinically interpretable range of expected effects in future studies. |

| 5. Visualize Data | Always present a forest plot. Consider additional plots (Baujat, Galbraith) if enough studies are available. | Visual inspection complements statistical metrics, helping to identify patterns, outliers, and inconsistencies. |

| 6. Explore Sources with Caution | If subgroup or meta-regression analyses are conducted, explicitly state they are exploratory and hypothesis-generating. | Prevents overinterpretation of findings with low statistical power and high risk of ecological fallacy or spurious results. |

| Pitfall | Example | Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Choosing model based on statistical threshold | Switching to random-effects only if Q-test p < 0.10 | Misleading inference; model choice should be conceptually justified, not threshold-driven |

| Using DerSimonian–Laird by default | Applying DL estimator in small or heterogeneous meta-analyses | Underestimation of τ2, overly narrow CIs, false precision |

| Overinterpreting subgroup or meta-regression results | Treating subgroup differences as confirmatory | False positives due to low power and ecological bias |

| Ignoring prediction intervals | Reporting only pooled effect and CI | Misses clinical implications of between-study variability |

| Excluding studies based on funnel plot asymmetry alone | Removing “outliers” due to funnel plot | Conflates publication bias with heterogeneity; risks cherry-picking |

| Interpreting or performing funnel plots with few studies (<10) | Drawing conclusions about publication bias from funnel plot when k < 10 | Funnel plots are unreliable with few studies; risk of false inference of bias or asymmetry |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).