Submitted:

19 August 2025

Posted:

20 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

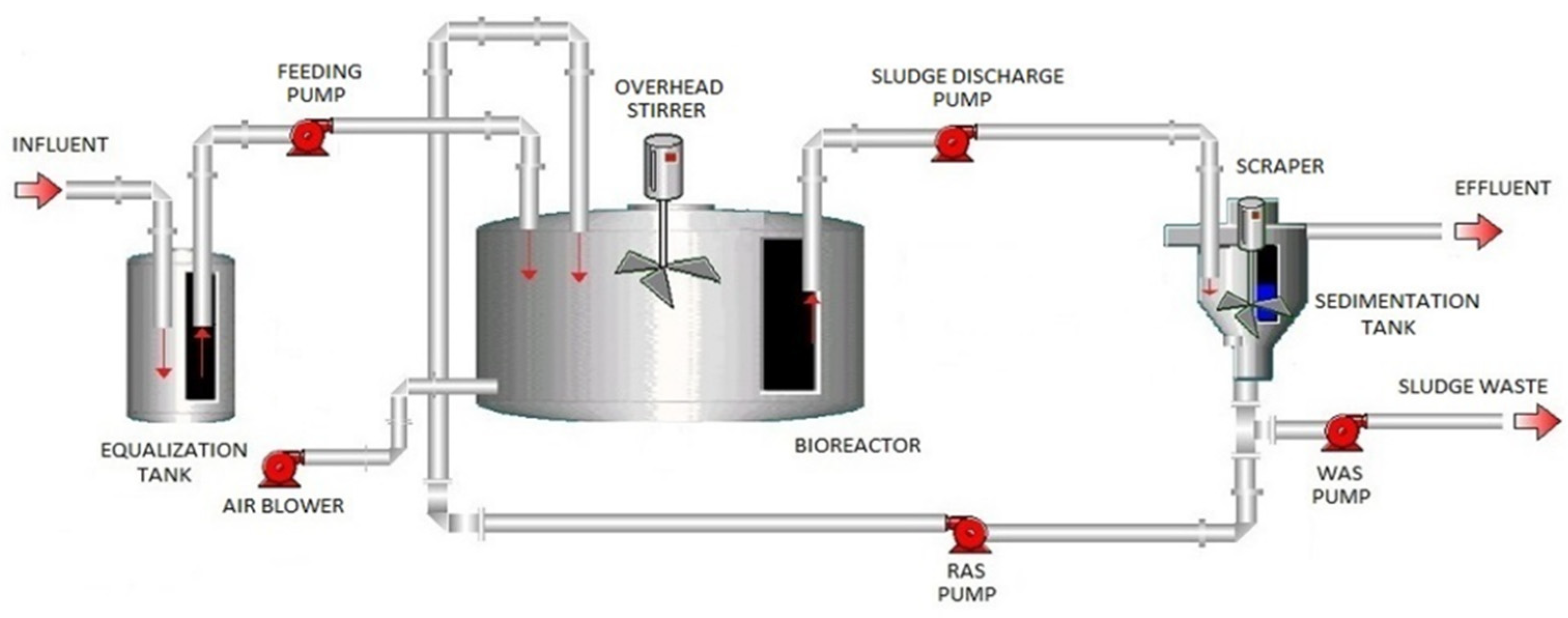

2.1. Experimental Apparatus

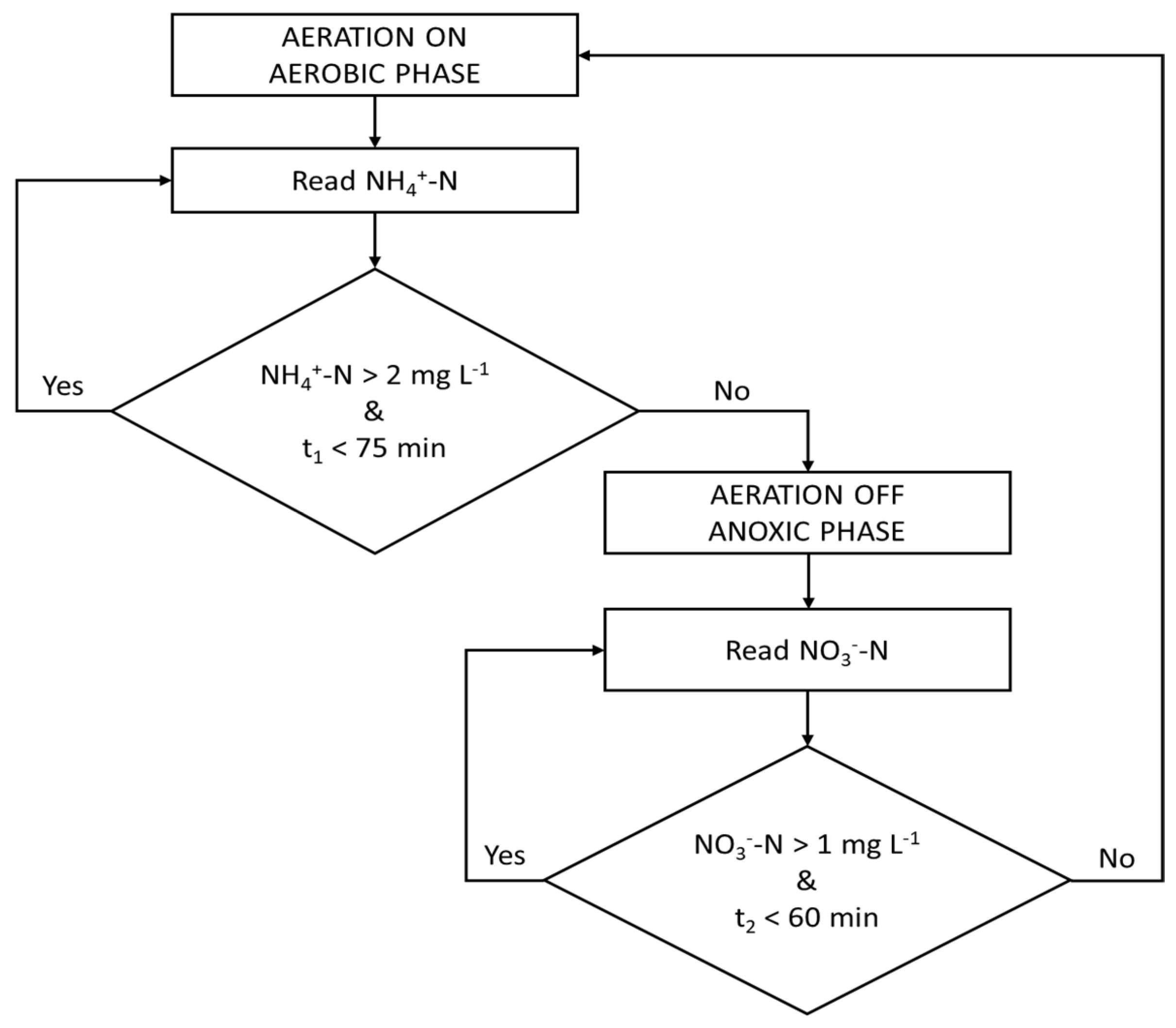

2.2. Real-Time Control Strategy

2.3. Instrumentation and Software

3. Results and Discussion

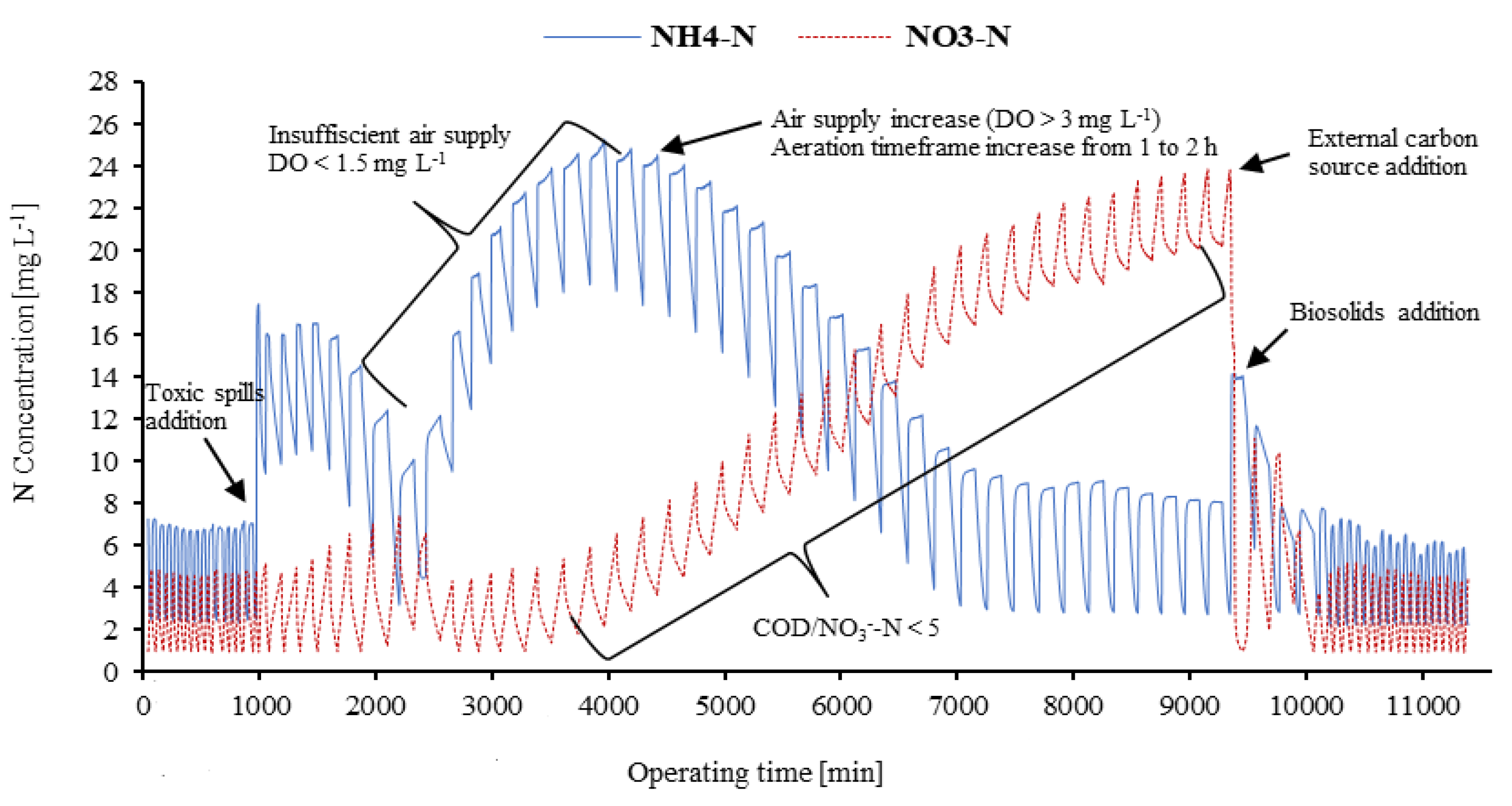

3.1. Performance of IAF-AS System and Operating Conditions

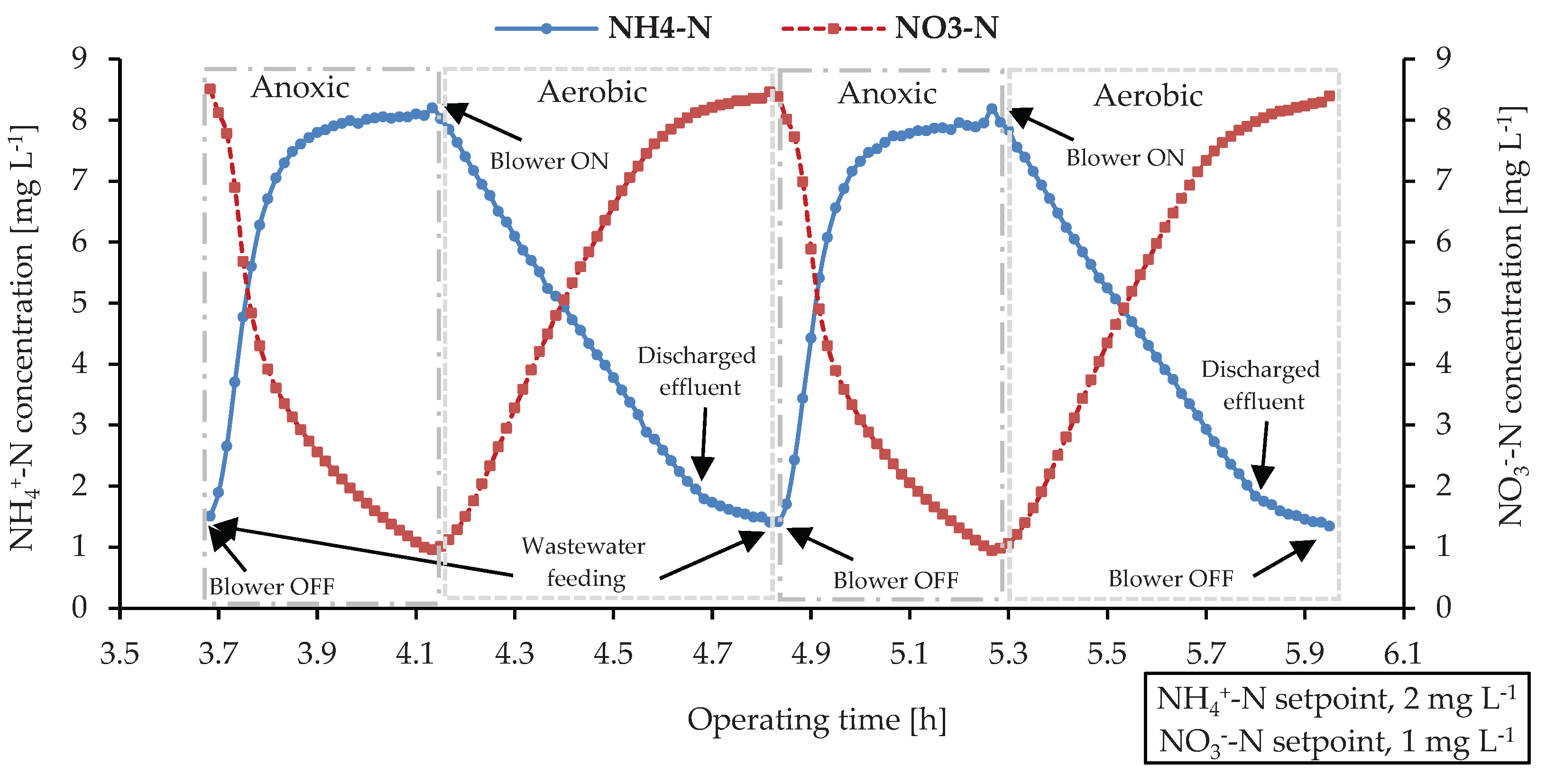

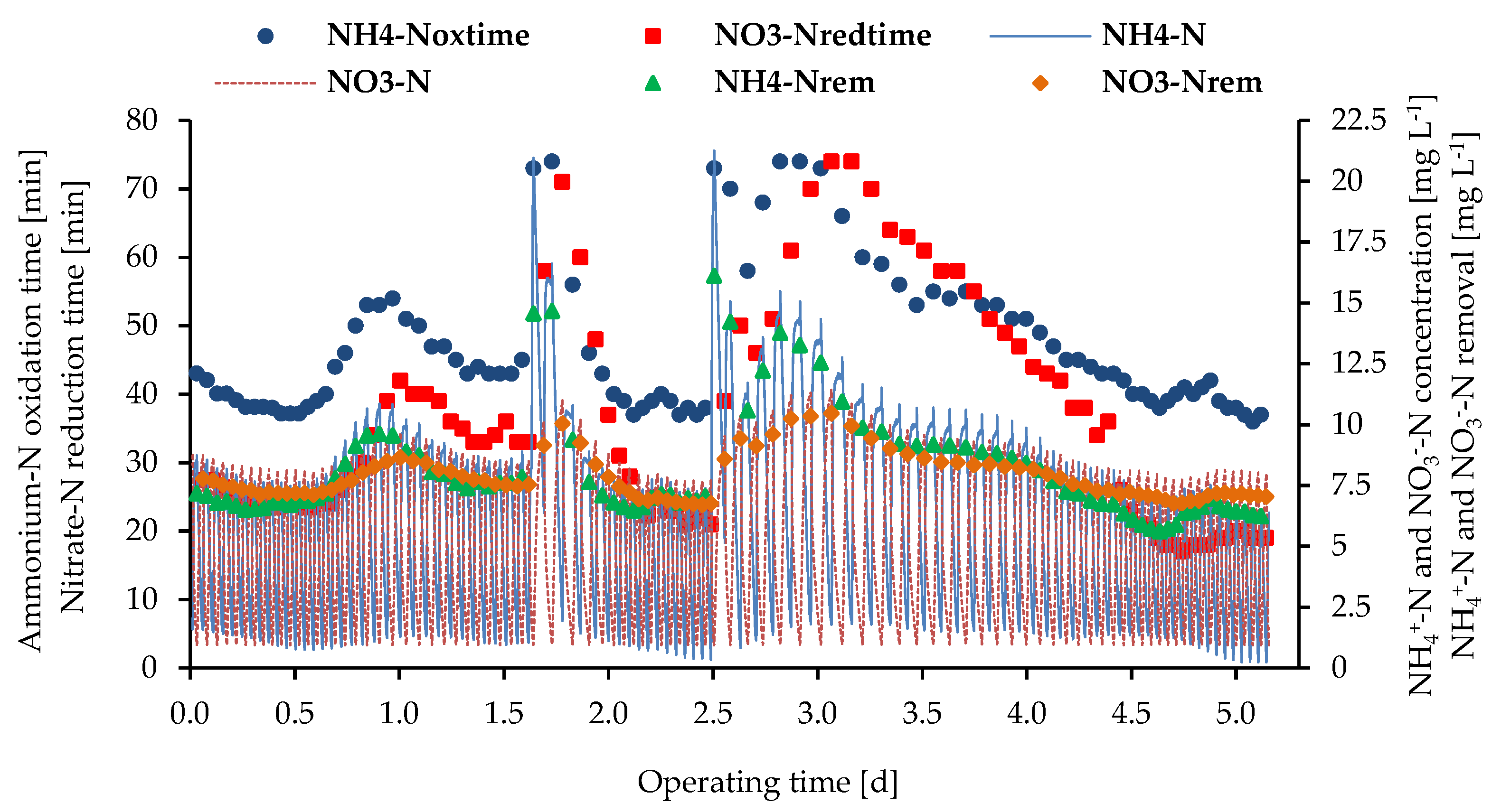

3.2. Dynamic Control of Nitrification and Denitrification Process by NH4+-N and NO3--N Sensors

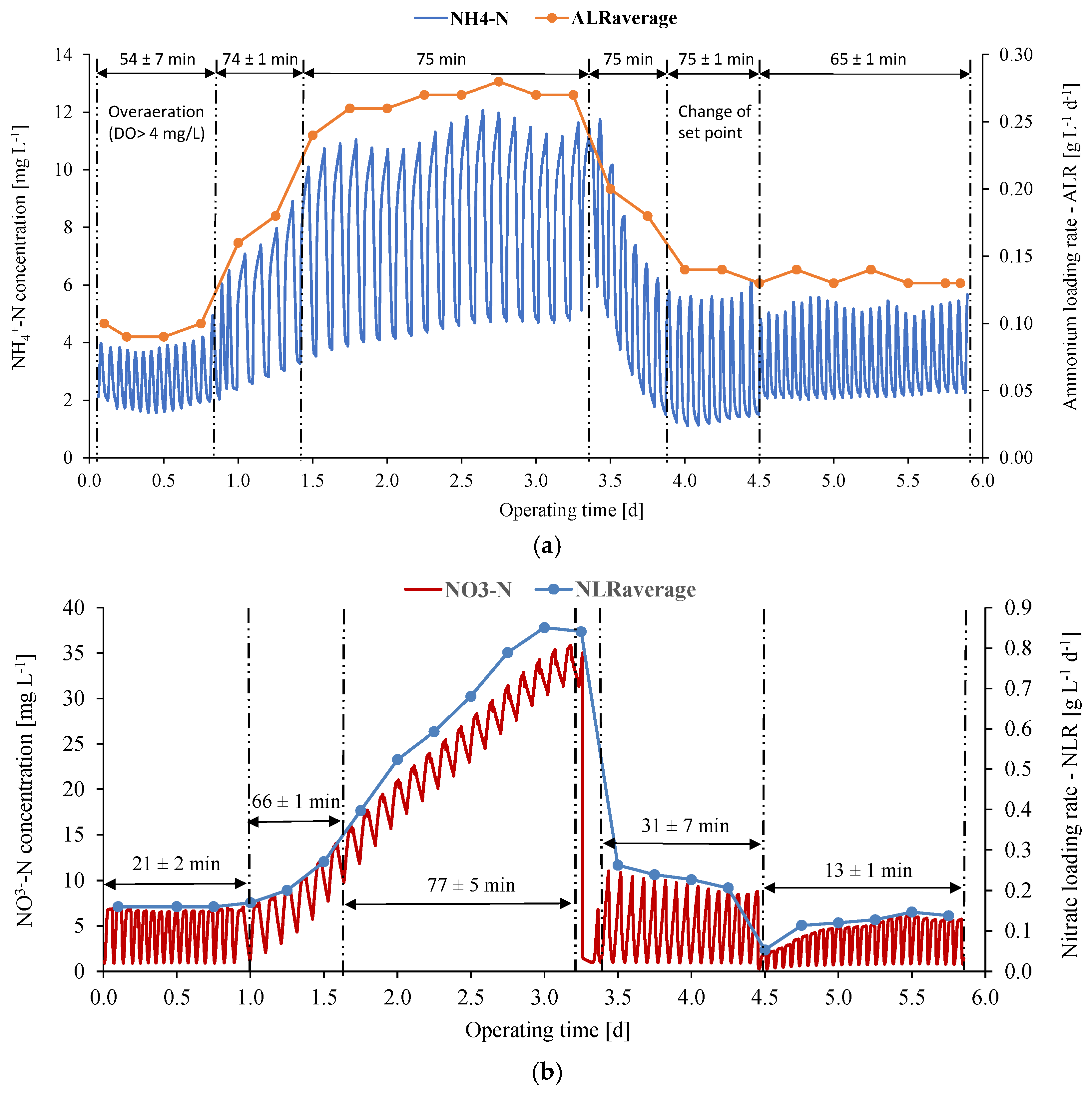

3.3. Nitrification and Denitrification Process Control Outcomes After Interventions

3.4. Dynamic Nitrification and Denitrification Process Control After Sudden and Deliberate External Disturbance

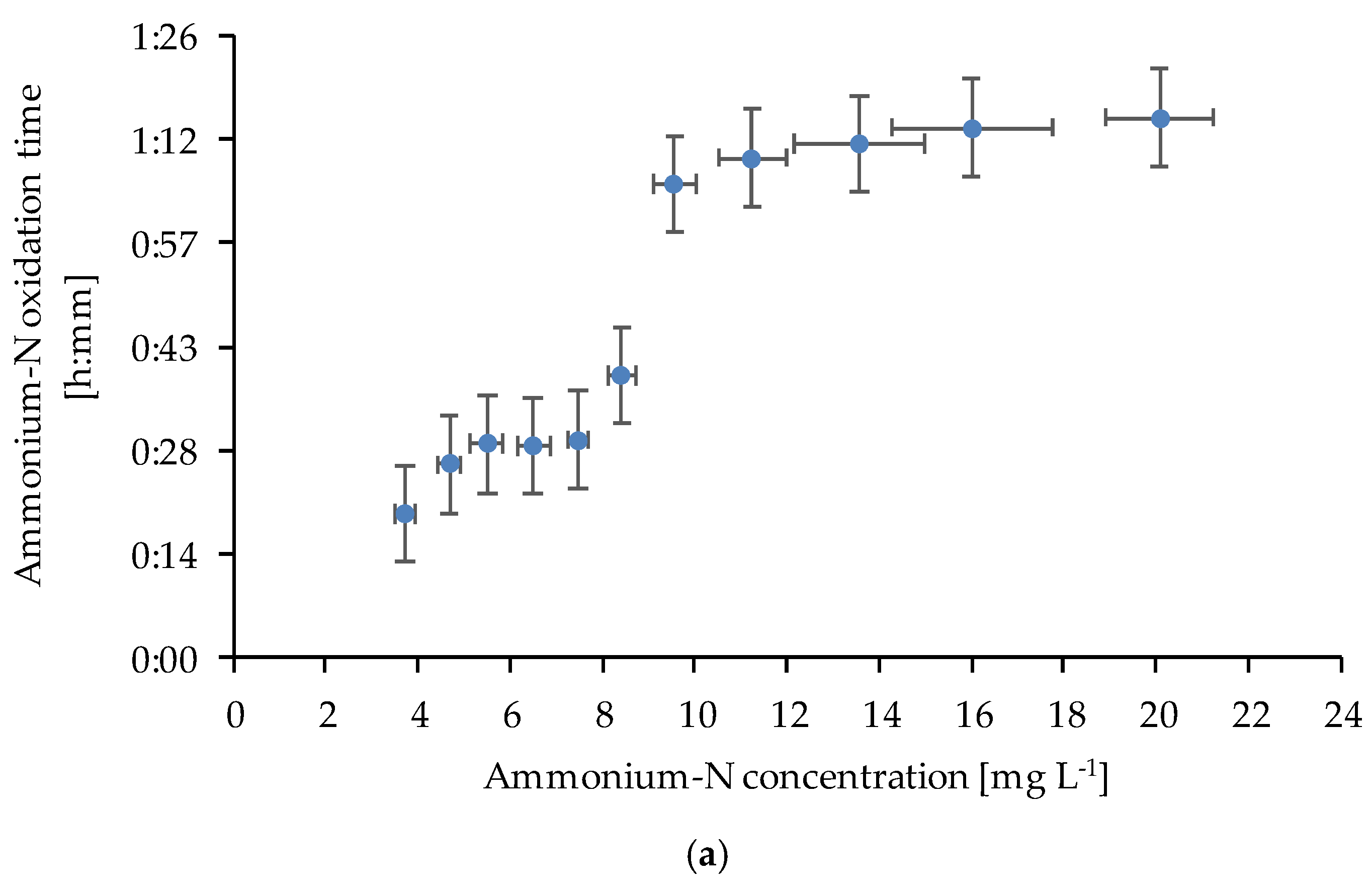

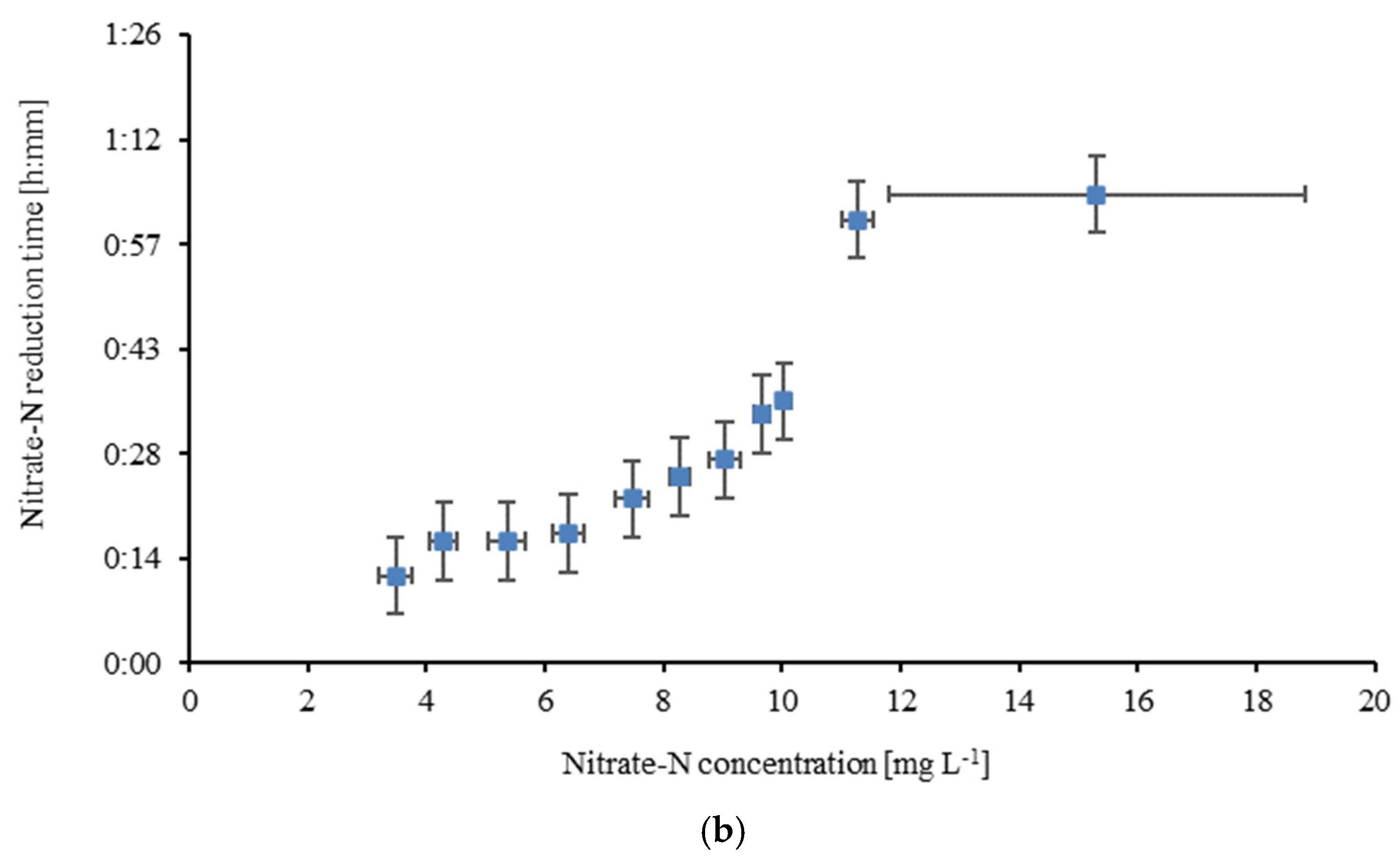

3.5. Specific Nitrification (SNR) and Denitrification (SDR) Rates

3.6. Energy Consumption

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Marsili-Libelli, S.; Spagni, A.; Susini, R. Intelligent monitoring system for long-term control of sequencing batch reactors. Water Sci Technol 2008, 57, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avilés, A.B.L.; Velázquez, F.D.C.; Del Riquelme, M.L.P. Methodology for energy optimization in wastewater treatment plants. Phase iii: Implementation of an integral control system for the aeration stage in the biological process of activated sludge and the membrane biological reactor. Sensors (Basel) 2020, 20, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Iratni, A.; Chang, N.B. Advances in control technologies for wastewater treatment processes: Status, challenges, and perspectives. IEEE CAA J Autom Sin 2019, 6, 337–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drewnowski, J.; Remiszewska-Skwarek, A.; Duda, S.; Łagód, G. Aeration process in bioreactors as the main energy consumer in a wastewater treatment plant. Review of solutions and methods of process optimization. Processes 2019, 7, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alattabi, A.W.; Harris, C.; Alkhaddar, R.; Alzeyadi, A.; Abdulredha, M. Online Monitoring of a Sequencing Batch Reactor Treating Domestic Wastewater. Procedia Eng 2017, 196, 800–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Mu, J.; Li, X.; Shan, R.; Li, K.; Liu, M.; Yu, M. A strategy for starting and controlling nitritation-denitrification in an SBR with DO and ORP online monitoring signals. Desalination Water Treat 2019, 151, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Mu, J.; Du, Y.; Wu, Z. Study and application of real-time control strategy based on DO and ORP in nitritation–denitrification SBR start-up. Environ Technol 2021, 42, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo, F.; Orchard, M.; Muñoz, C.; Zamorano, M.; Antileo, C. Advanced strategies to improve nitrification process in sequencing batch reactors - A review. J Environ Manage 2018, 218, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyake, M.; Hasebe, Y.; Furusawa, K.; Shiomi, H.; Inoue, D.; Ike, M. Enhancement of nutrient removal in an activated sludge process using aerobic granular sludge augmentation strategy with ammonium-based aeration control. Chemosphere 2023, 340, 139826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieger, L.; Jones, R.M.; Dold, P.L.; Bott, C.B. Ammonia-based feedforward and feedback aeration control in activated sludge processes. Water Environ Res 2014, 86, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Várhelyi, M.; Cristea, V.M.; Brehar, M. Improving Waste Water Treatment Plant Operation by Ammonia Based Aeration and Return Activated Sludge Control. Comput Aided Chem Eng 2019, 46, 1165–1170. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, R.D.; Bashar, R.; Amstadt, C.; Uribe-Santos, G.A.; McMahon, K.D.; Seib, M.; Noguera, D.R. Pilot-scale comparison of biological nutrient removal (BNR) using intermittent and continuous ammonia-based low dissolved oxygen aeration control systems. Water Sci Technol 2022, 85, 579–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansouri, A.M.; Zinatizadeh, A.A.; Irandoust, M.; Akhbari, A. Statistical analysis and optimization of simultaneous biological nutrients removal process in an intermittently aerated SBR. Korean J Chem Eng 2014, 31, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melidis, P.; Ntougias, S.; Sertis, C. On-line monitoring of a BNR process using in situ ammonium and nitrate probes and biomass nitrification-denitrification rates in an intermittently aerated and pulse fed bioreactor. J Chem Technol Biotechnol 2014, 89, 1516–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regmi, P.; Bunce, R.; Miller, M.W.; Park, H.; Chandran, K.; Wett, B.; Murthy, S.; Bott, C.B. Ammonia-based intermittent aeration control optimized for efficient nitrogen removal. Biotechnol Bioeng 2015, 112, 2060–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.K.; Bhatia, A.; Kazmi, A.A. Effect of intermittent aeration strategies on treatment performance and microbial community of an IFAS reactor treating municipal wastewater. Environ Technol 2017, 38, 2866–2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barana, A.C.; Lopes, D.D.; Martins, T.H.; Pozzi, E.; Damianovic, M.H.R.Z.; Del Nery, V.; Foresti, E. Nitrogen and organic matter removal in an intermittently aerated fixed-bed reactor for post-treatment of anaerobic effluent from a slaughterhouse wastewater treatment plant. J Environ Chem Eng 2013, 1, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wosiack, P.A.; Lopes, D.D.; Rissato Zamariolli Damianovic, M.H.; Foresti, E.; Granato, D.; Barana, A.C. Removal of COD and nitrogen from animal food plant wastewater in an intermittently-aerated structured-bed reactor. J Environ Manage 2015, 154, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.E.D.; Moura, R.B.; Damianovic, M.H.R.Z.; Foresti, E. Influence of COD/N ratio and carbon source on nitrogen removal in a structured-bed reactor subjected to recirculation and intermittent aeration (SBRRIA). J Environ Manage 2016, 166, 519–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Liu, R.; Chen, L.; Dong, B.; Kawagishi, T. Advantages of intermittently aerated SBR over conventional SBR on nitrogen removal for the treatment of digested piggery wastewater. Front Environ Sci Eng 2017, 11, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azis, K.; Ntougias, S.; Melidis, P. NH4+-N versus pH and ORP versus NO3--N sensors during on-line monitoring of an intermittently aerated and fed membrane bioreactor. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2021, 28, 33837–33843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchobanoglous, G.; Abu-Orf, M.; Burton, F.L.; Bowden, G.; Stensel, H.D.; Tsuchihashi, R.; Pfrang, W. Wastewater Engineering: Treatment and Resource Recovery, 5th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, USA, 2014; p. 2048. [Google Scholar]

- Parsa, Z.; Dhib, R.; Mehrvar, M. Dynamic Modelling, Process Control, and Monitoring of Selected Biological and Advanced Oxidation Processes for Wastewater Treatment: A Review of Recent Developments. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejaswini, E.S.S.; Uday Bhaskar Babu, G.; Seshagiri Rao, A. Design and evaluation of advanced automatic control strategies in a total nitrogen removal activated sludge plant. Water Environ J 2021, 35, 791–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrentino, R.; Langone, M.; Vian, M.; Andreottola, G. Application of real-time nitrogen measurement for intermittent aeration implementation in a biological nitrogen removal system: performances and efficiencies. Environ Technol 2019, 40, 2513–2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Åmand, L.; Olsson, G.; Carlsson, B. Aeration control – a review. Water Sci Technol 2013, 67, 2374–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsson, G.; Carlsson, B.; Comas, J.; Copp, J.; Gernaey, K.V.; Ingildsen, P.; Jeppsson, U.; Kim, C.; Rieger, L.; Rodríguez-Roda, I.; Steyer, J.-P.; Takács, I.; Vanrolleghem, P.A.; Vargas, A.; Yuan, Z.; Åmand, L. Instrumentation, control and automation in wastewater - From London 1973 to Narbonne 2013. Water Sci Technol 2014, 69, 1373–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Wang, Q.; Yan, H.; Chen, C.; Ma, J.; Xu, Q. Improve the performance of full-scale continuous treatment of municipal wastewater by combining a numerical model and online sensors. Water Sci Technol 2018, 78, 1658–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, T.; Xu, Z.; Hughes, E.; Qian, F.; Lee, M.; Fan, Y.; Lei, Y.; Brückner, C.; Li, B. Real-Time in Situ Monitoring of Nitrogen Dynamics in Wastewater Treatment Processes using Wireless, Solid-State, and Ion-Selective Membrane Sensors. Environ Sci Technol 2019, 53, 3140–3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelissen, R.; Van Dyck, T.; Dries, J.; Ockier, P.; Smets, I.; Van Den Broeck, R.; Van Hulle, S.; Feyaerts, M. Application of online instrumentation in industrial wastewater treatment plants - A survey in Flanders, Belgium. Water Sci Technol 2018, 78, 957–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dries, J. Dynamic control of nutrient-removal from industrial wastewater in a sequencing batch reactor, using common and low-cost online sensors. Water Sci Technol 2016, 73, 740–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipps, W.C.; Braun-Howland, E.B.; Baxter, T.E. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 24th ed.; American Public Health Association (APHA), American Water Works Association (AWWA) and Water Environment Federation (WEF): Washington, DC, USA, 2023; p. 1536. [Google Scholar]

- Srb, M.; Lánský, M.; Charvátová, L.; Koubová, J.; Pecl, R.; Sýkora, P.; Rosický, J. Improved nitrogen removal efficiency by implementation of intermittent aeration. Water Sci Technol 2022, 86, 2248–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.; Kang, H.J.; Park, Y.; Bae, J. Optimization of a sequencing batch reactor with the application of the Internet of Things. Water Res 2023, 229, 119511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battistoni, P.; Fatone, F.; Cola, E.; Pavan, P. Alternate cycles process for municipal WWTPs upgrading: Ready for widespread application? Ind Eng Chem Res 2008, 47, 4387–4393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardelli, P.; Gatti, G.; Eusebi, A.L.; Battistoni, P.; Cecchi, F. Full-scale application of the alternating oxic/anoxic process: An overview. Ind Eng Chem Res 2009, 48, 3526–3532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ngo, H.H.; Guo, W.; Peng, L.; Wang, D.; Ni, B. The roles of free ammonia (FA) in biological wastewater treatment processes: A review. Environ Int 2019, 123, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, M.; Chen, T.; Hu, Z.; Zhan, X. Assessment of nitrogen and phosphorus removal in an intermittently aerated sequencing batch reactor (IASBR) and a sequencing batch reactor (SBR). Water Sci Technol 2013, 68, 400–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Gao, X.; Peng, Y. Optimization of the intermittent aeration to improve the stability and flexibility of a mainstream hybrid partial nitrification-anammox system. Chemosphere 2020, 261, 127670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, T.; Demir, E.K.; Başaran, S.T.; Çokgör, E.U.; Sahinkaya, E. Specific ammonium oxidation and denitrification rates in an MBR treating real textile wastewater for simultaneous carbon and nitrogen removal. J Chem Technol Biotechnol 2023, 98, 2859–2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotro, G.; Jefferson, B.; Jones, M.; Vale, P.; Cartmell, E.; Stephenson, T. A review of the impact and potential of intermittent aeration on continuous flow nitrifying activated sludge. Environ Technol 2011, 32, 1685–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Average (± St. Deviation) |

|---|---|

| Total COD (mg L-1) | 375 ± 72.7 |

| Soluble COD (mg L-1) | 185 ± 68.9 |

| BOD5 (mg L-1) | 230 ± 33.2 |

| NH4+-N (mg L-1) | 57.3 ± 15.8 |

| TKN (mg L-1) | 73.8 ± 12.9 |

| SS (mg L-1) | 132 ± 39.1 |

| PO43--P (mg L-1) | 5.87 ± 1.4 |

| pH | 7.67 ± 0.19 |

| EC (μS cm-1) | 1318 ± 98.9 |

| NH4+-Nin range (mg L-1) |

NH4+-N oxidation time (min) | SNR (g g -1 VSS d-1) | NO3--Nform range (mg L-1) |

NO3--N reduction time (min) | SDR (g g -1 VSS d-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.5-5.0 | 17-29 (25±3) | 0.103-0.119 | 3.0-5.0 | 6-24 (16±5) | 0.372-0.468 |

| 5.1-7.5 | 24-35 (29±2) | 0.092-0.143 | 5.1-7.5 | 9-31 (16±7) | 0.378-0.576 |

| 7.6-9.5 | 31-62 (43±11) | 0.089-0.099 | 7.6-9.0 | 15-33 (26±4) | 0.389-0.677 |

| 9.6-14 | 50-75* (69±7) | 0.09-0.099 | 9.1-10.5 | 31-40 (34±2) | 0.385-0.517 |

| 14.1-21 | 70-75* (73±1) | 0.097-0.14 | 10.6-15 | 37-64 (56±8) | 0.448-0.525 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).