5. Benthic Foraminifera Identification and Distribution

Benthic foraminifera species and genera were identified and counted in 47 samples of the dispersed-shell lithofacies in Barfield Bay Cores 3, 4, and 5 and Caxambas Pass Core 1. These counts were then summed by genus so that Poag’s synthesis of generic predominance facies for the modern Gulf of Mexico [

35] could be applied to interpret Holocene environments of the sediment fill of Barfield Bay. A predominant genus is “…a genus in a given sample that is represented by the most abundant specimens” [

35]. “A generic predominance facies is a benthic foraminifera assemblage characterized by a particular predominant genus” [

35].

Three predominant genera are represented in the benthic foraminifera assemblages in the Barfield Bay and Caxambas Pass core samples. Two of these are the hyaline taxa

Ammonia spp. and

Elphidium spp., and the third is the miliolids. Poag [

35] combined all miliolids into a Miliolid Predominance Facies because, in his words, “(1) miliolid genera are difficult to separate consistently and (2) low latitude miliolids seem to have generally similar environmental requirements” [

35]. The sum of these three predominant genera comprises 95% to 100% of the foraminifera in all Barfield Bay samples studied here.

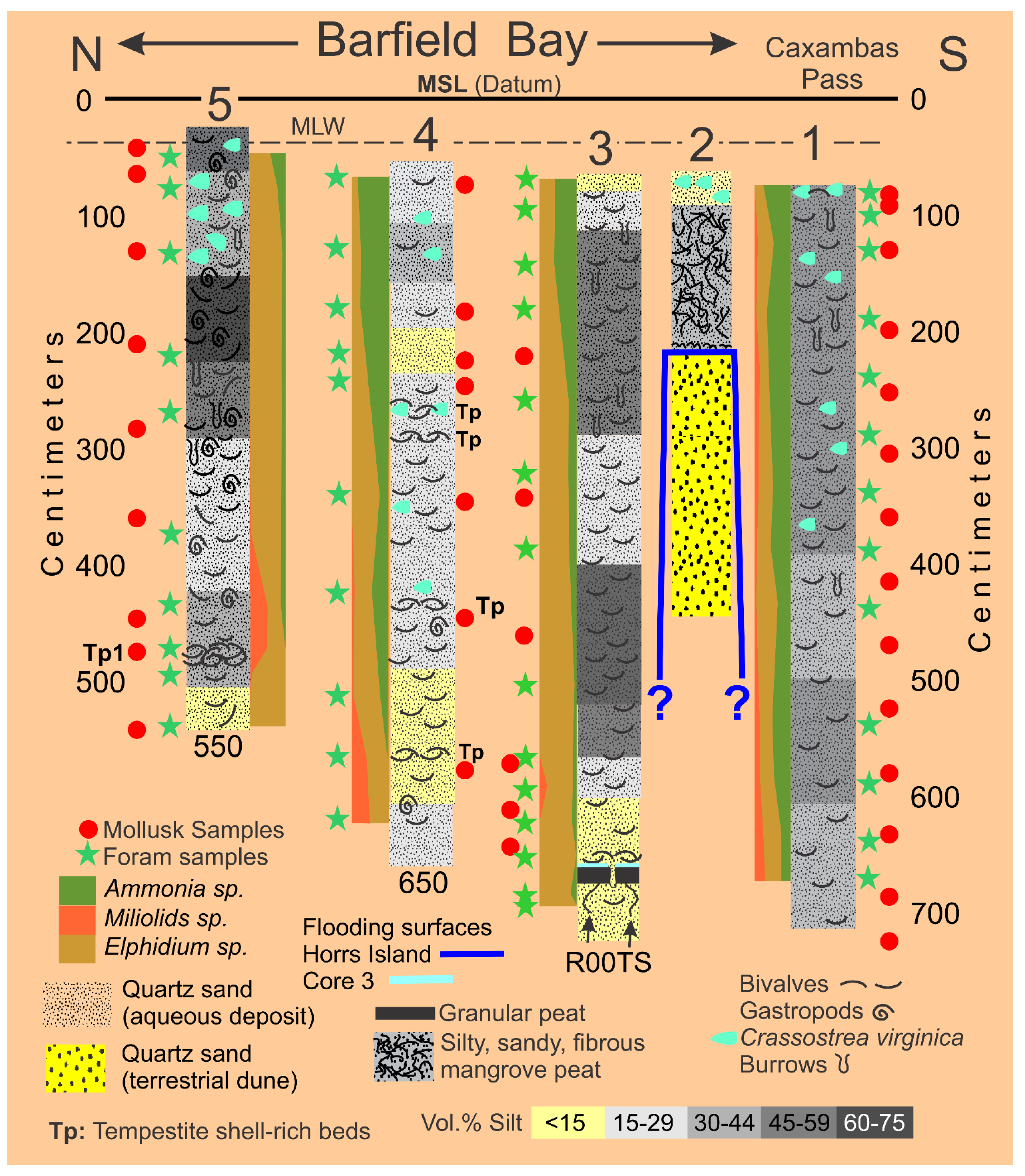

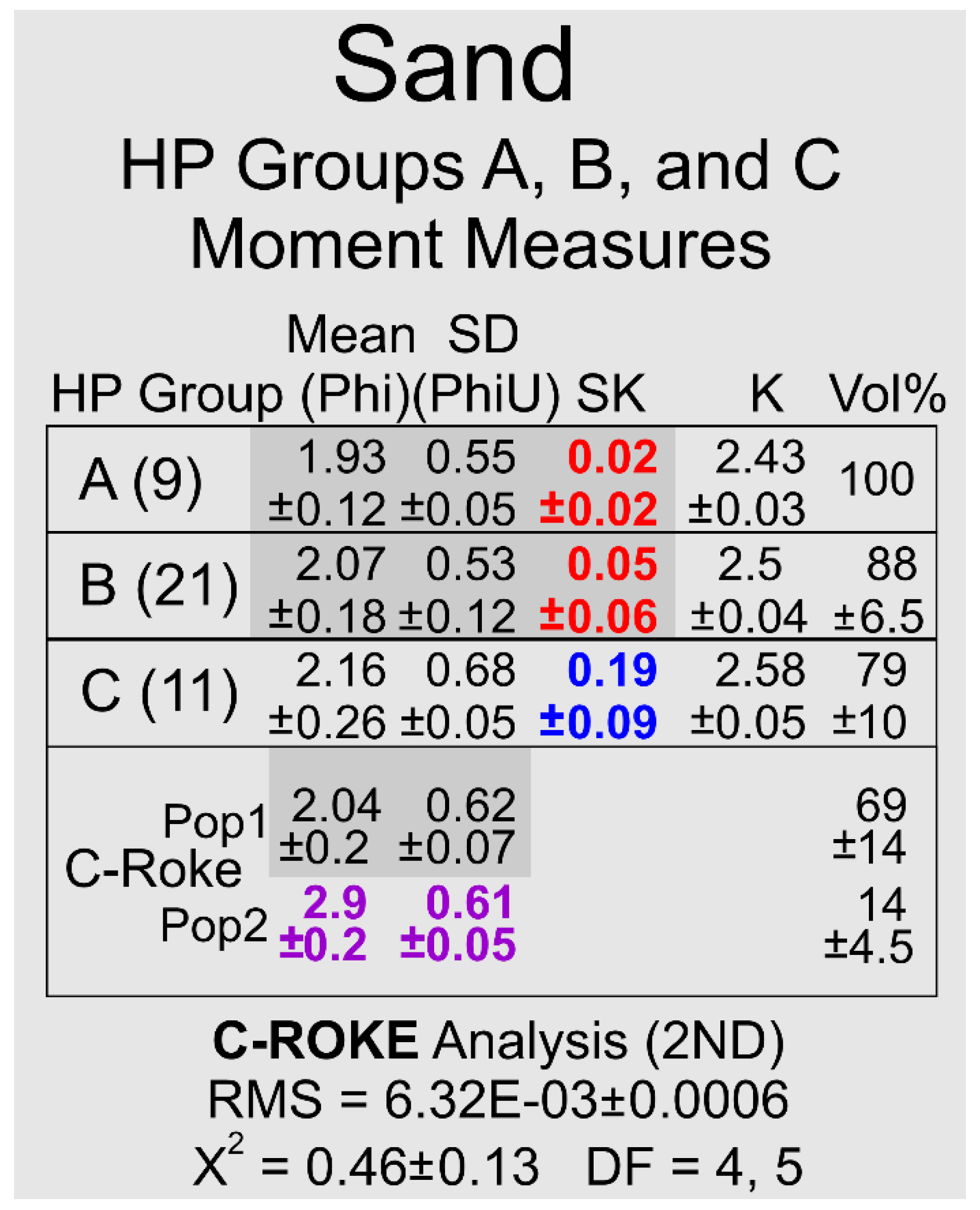

Elphidium spp. dominates the entire thickness of the bioturbated sediment-fill in Cores 5 and 3,

Figure 13. It is the most abundant genus throughout the lower 4 meters of Core 4, and it is second to

Ammonia spp. in abundance throughout Core 1,

Figure 13.

Ammonia spp. is second in overall abundance and is the most abundant benthic foraminifer in the upper meter of Core 4,

Figure 13. Miliolids are the least abundant benthic foraminifers present in the Barfield Bay samples; they comprise 40-50% of the basal meter in Cores 5 and 4 and 10-20% of the basal meter in Cores 3 and 1,

Figure 13.

Because of the close proximity of Barfield Bay to their study area, the benthic foraminifera study of Benda and Puri [

36] is a useful modern analog for interpreting Holocene environments of Barfield Bay. These authors analyzed benthic foraminifera species (and ostracods which are not reviewed here) at 116 stations arrayed across coast-parallel environments from marsh river, lagoon, and mangrove islands in the Ten Thousand Islands area and from environments offshore of the mangrove islands in Gullivan Bay. The predominant genera in their data [

36] are the same as for the Barfield Bay core samples, namely,

Ammonia spp.

, Elphidium spp., and miliolids. The generic percentages in the 116 bottom samples [

36], contoured at 10, 30, 50, and 70 percentage values, are shown in genus-specific panels in

Figure 20. The

Ammonia spp. distribution consists of a coastal, or proximal, high-concentration band and a miliolids distribution of a more open Gulf, or distal, high-concentration band, Panels A and C of

Figure 20.

Elphidium spp. has a much more complicated distribution with “pockets” of extremely high values, in both coastal and offshore locations, interspersed in a more blanket-like distribution of values in the 20-40% range,

Figure 20.

The primary tidal opening into Barfield Bay lies near the middle of the

Elphidium spp. blanket [

37] and on the gulfward boundary of the

Ammonia spp. band, therefore,

Elphidium spp. and

Ammonia spp. should be and are the two prominent components of the benthic foraminifera population in the three Barfield Bay cores as well as in the Caxambas Pass core,

Figure 13. In addition,

Ammonia spp. is enriched in the uppermost 1-1.5 meters of the three Barfield Bay Cores and the Caxambas Pass Core,

Figure 13. Miliolids, however, are present primarily in the basal 1-1.5 meters of the three Barfield Bay Cores as well as in the Caxambas Pass Core,

Figure 10. A possible explanation for this miliolid restriction to the oldest portions of these cores is that deposition of the adjacent Kice, Morgan, and Cape Romano barrier islands as well as the mangrove-covered islands immediately south of Barfield Bay (shown in gray in

Figure 20) greatly reduced access to the open Gulf of Mexico. In summary, the benthic foraminifera population of Barfield Bay, dominated by

Elphidium spp. and, to a lesser extent,

Ammonia spp., is consistent with the overall benthic foraminifera distributions identified in the Benda and Puri [

36] data.

6. Summary of Mollusk and Benthic Foraminifera Content of the Barfield Bay Bioturbated Sediment-fill

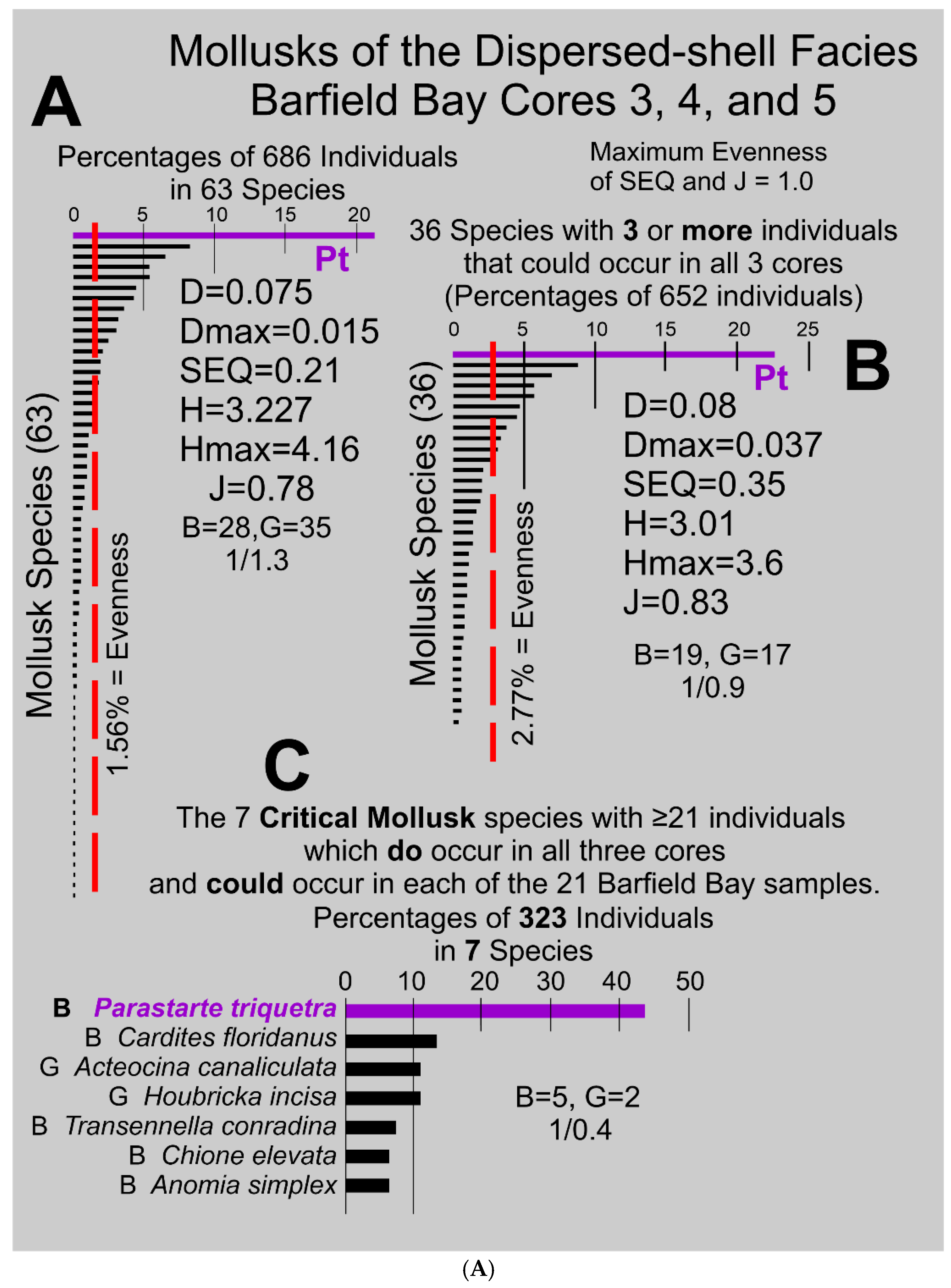

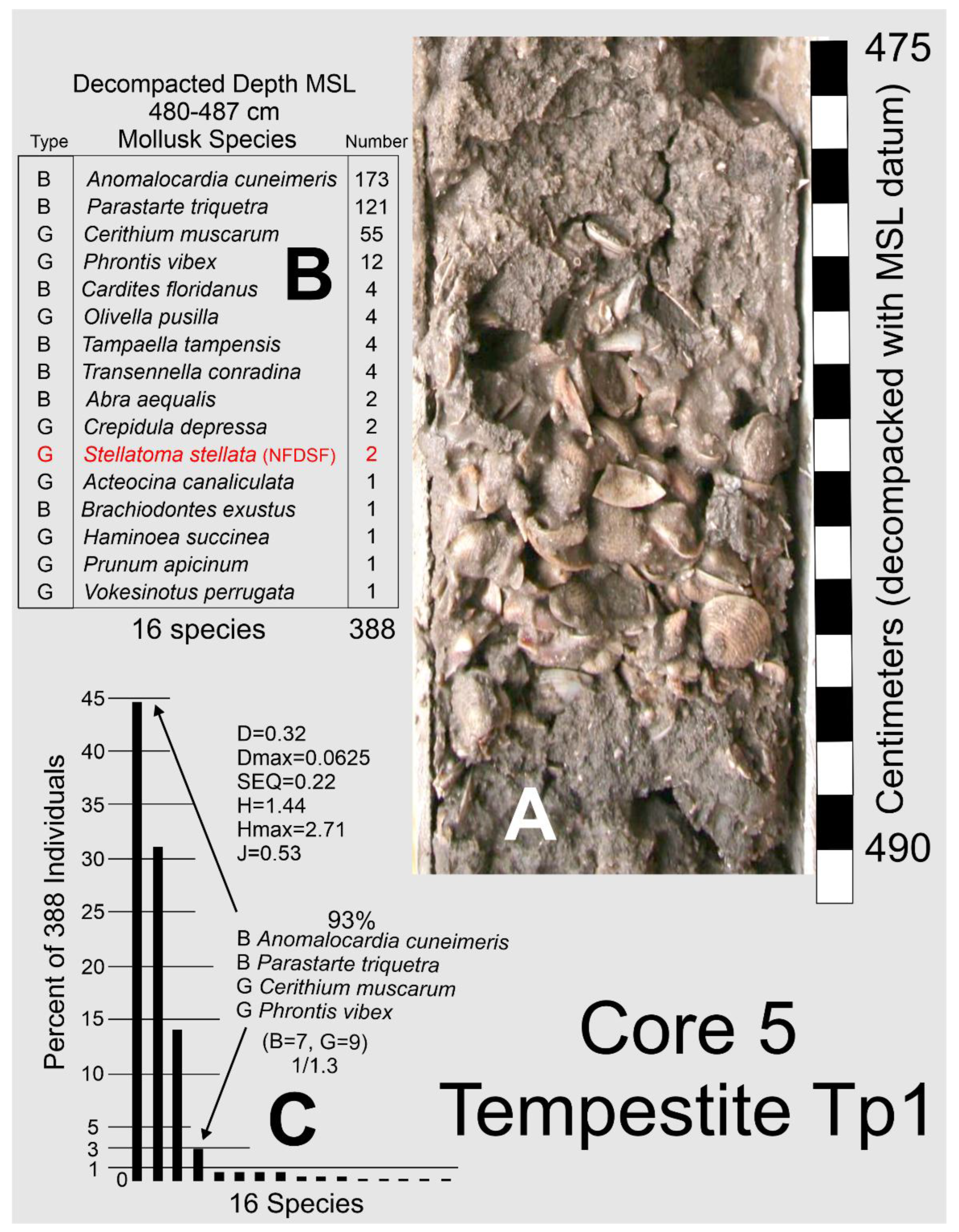

The mollusks (smaller than the 7cm diameter of the vibracore barrel) identified in this study comprise 686 individuals organized into 63 species. The two dominant species in the bioturbated sediment-fill, in terms of total individuals, are the bivalves Parastarte triquetra and Anomalocardia cuneimeris. The tempestite Tp1 sample contains 388 individuals. This tempestite deposit can be considered a taphocoenosis derived from a thanatocoenosis by a storm event.

Species diversity of the mollusks in the Barfield Bay bioturbated sediment-fill, as indicated by the Shannon Diversity Index

H=3.227 (Hmax =4.16) [

27] and the Simpson Concentration Index

D=0.075 [

28] (possible range of 0-1 with 0 being more diverse), is high. However, these two diversity indices are known to over emphasize species richness (

S=63) at the expense of species abundance. The degree of evenness of individuals per species is indicated by the Shannon Evenness Index

SEI/J=0.78 (range of 0-1) [

27] which indicates a fairly high degree of evenness and the Simpson Equitability Index

SEQ=0.21 [

28] which indicates a low degree of evenness and the dominance of a few species. An inspection of the actual distribution of percentages of total individuals per species, Panels A and B in

Figure 14A, clearly shows a highly skewed distribution that is dominated by 14 species out of the total 63. The mollusk population of the bioturbated sediment-fill is

very uneven with forty-three (43) of the sixty-three (63) species containing only

109 individuals out of the total

686 or 15%. Stated another way, one-third (33%) of the identified species contain 85% of the individuals. Thus, the smaller (<7cm) mollusk population of Barfield Bay is characterized as being rich in number of species (

S=63) and is dominated by a relatively few species with the two pelecypods,

Parastarte triquetra and

Anomalocardia cuneimeris, being the most prominent. Twelve (12) of the fourteen (14) most abundant species occur in all three Barfield Bay cores and seven of these twelve are represented by numbers greater than 21 so that they potentially can occur in all 21 mollusk samples. These seven

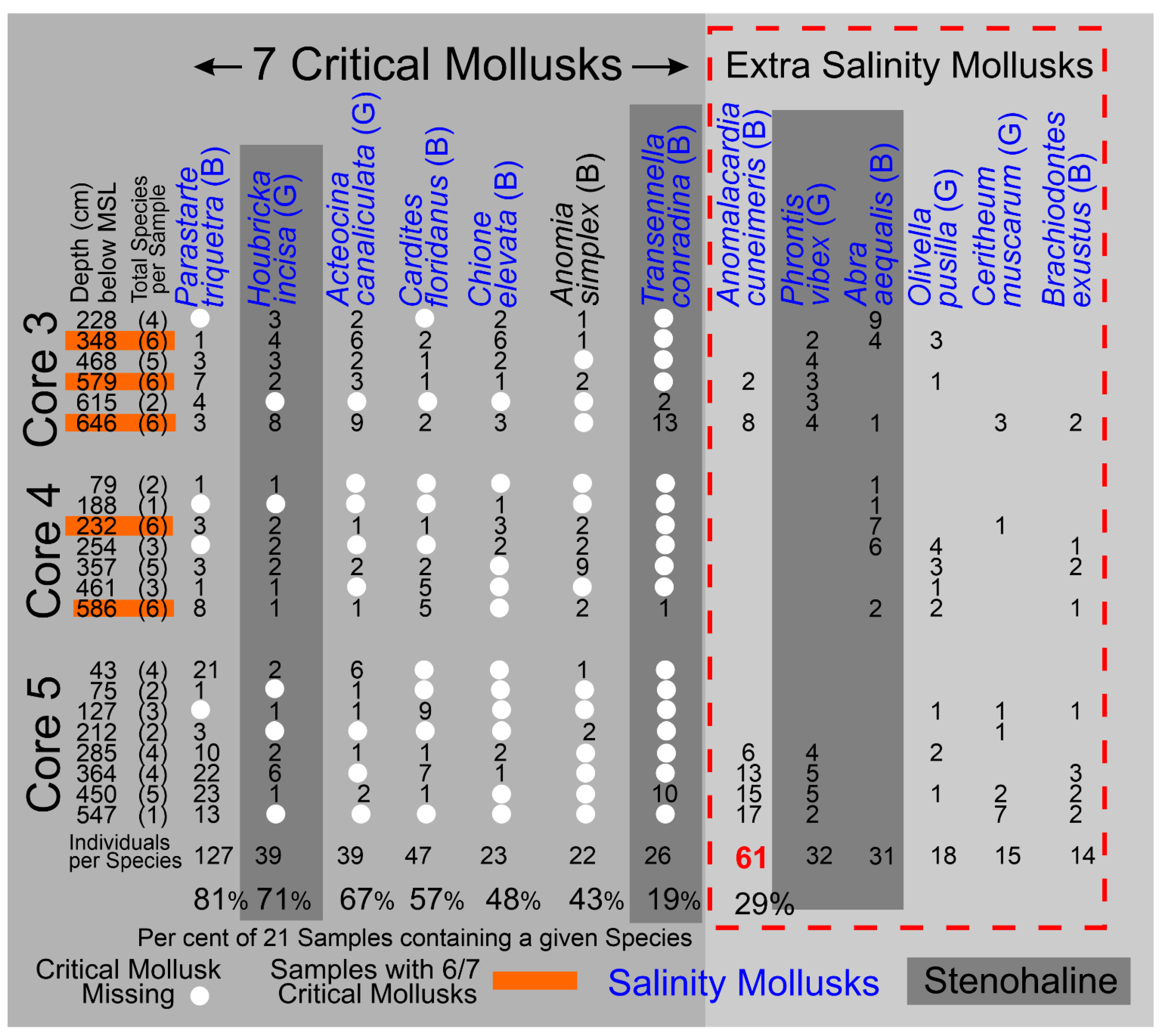

Critical Mollusks, along with their respective percentage occurrence in the 21 samples, are

Parastarte triquetra (81%),

Houbricka incisa (71%),

Acteocina canaliculata (67%),

Cardites floridanus (57%),

Chione elevata (48%),

Anomia simplex (43%), and

Transennella conradina (19%).

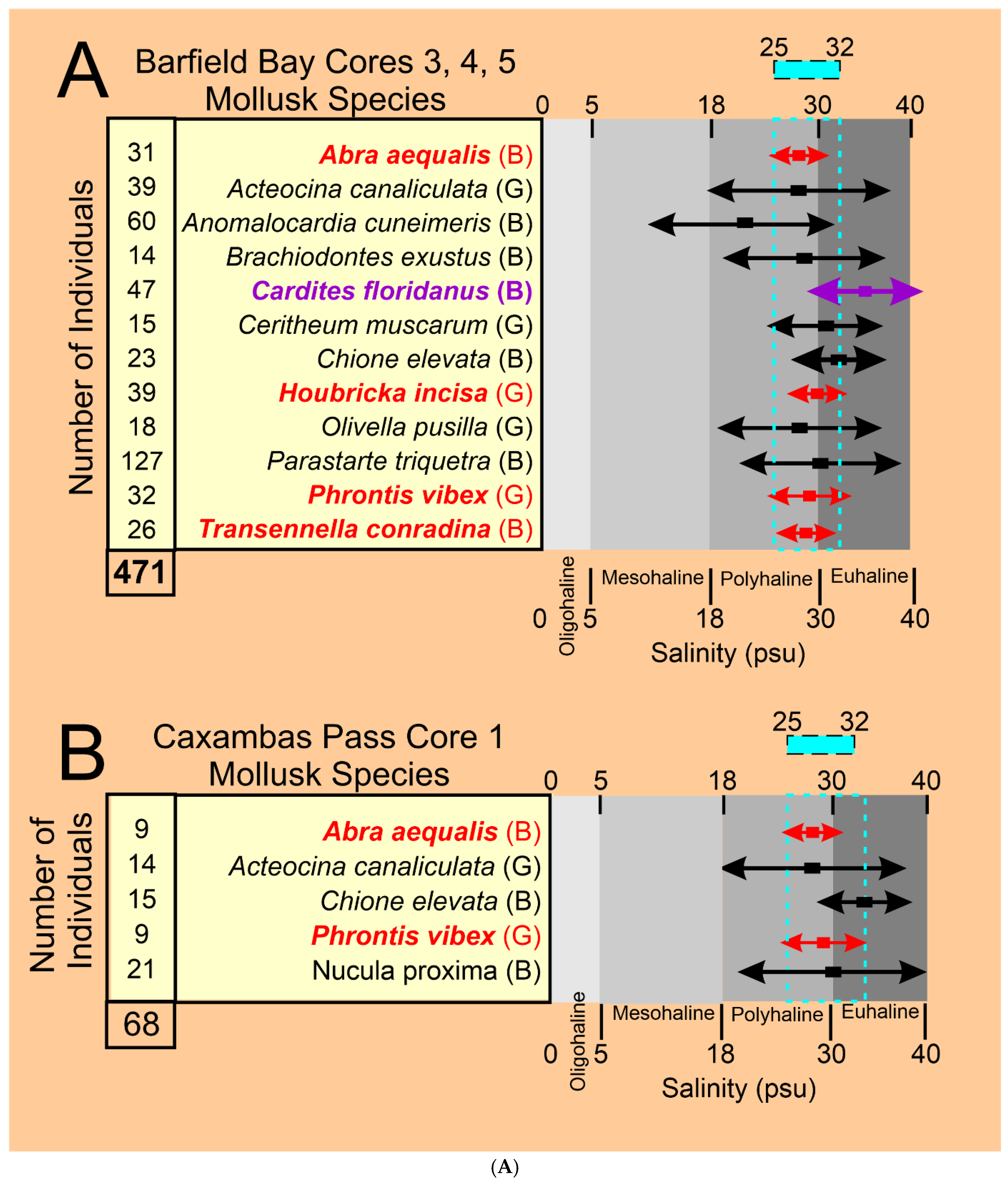

The twelve most abundant mollusks present in the bioturbated sediment-fill have been used to estimate the paleo-salinity during the deposition of the Barfield Bay sediment-fill. The present-day salinity ranges for these 12 mollusks [

30,

31] overlap in the range 25-32 psu, which is the upper half of the polyhaline to the lower 2 psu units of the euhaline zone,

Figure 18A. This 7 psu range is basically the range of the four, most stenohaline, mollusks in this HP Group of 12. Because members of this more abundant HP Group occur throughout the entire 7-meter-thick stratigraphic section (

Figure 11A), this paleo-salinity regime most likely characterized Barfield Bay during the deposition of the entire sediment-fill.

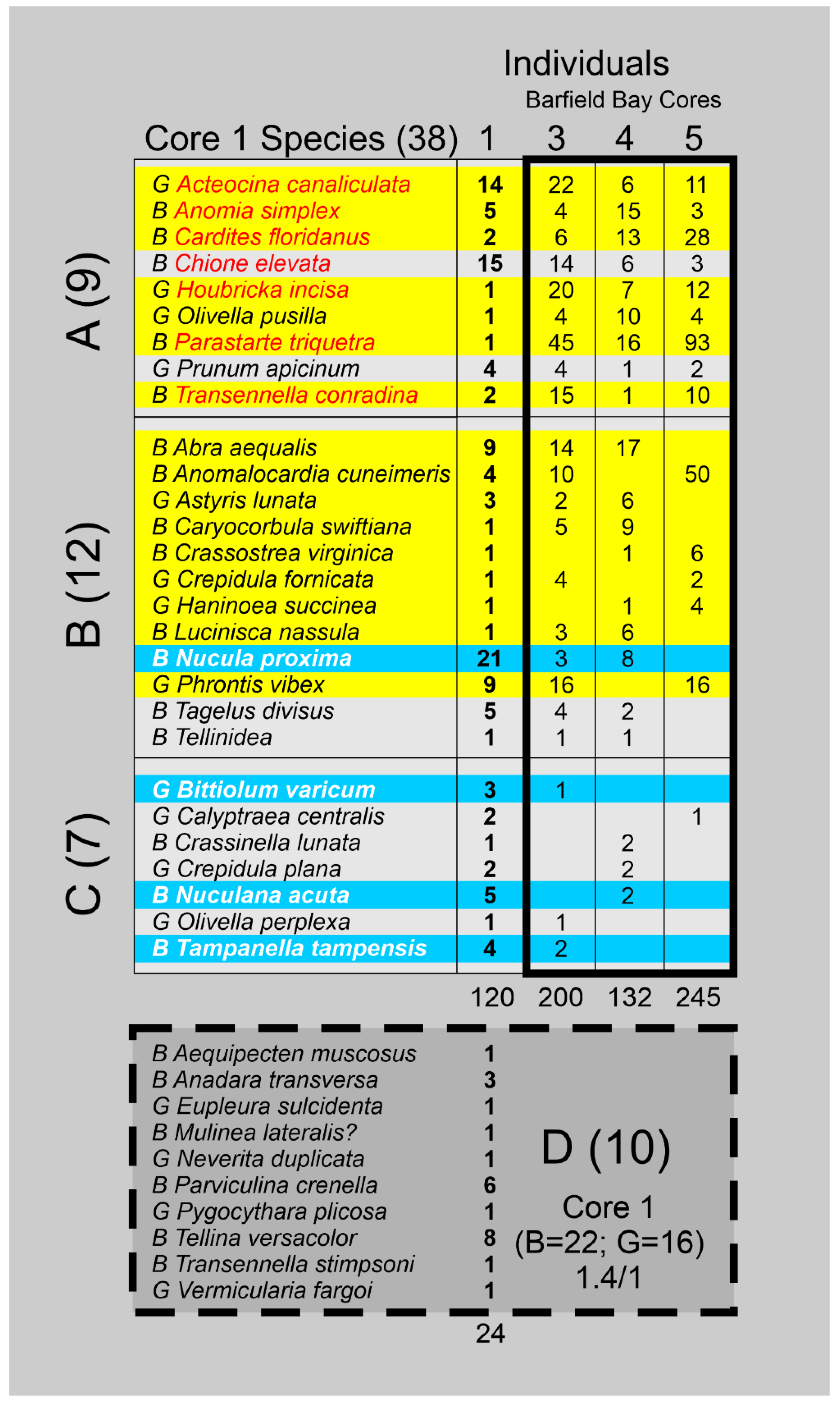

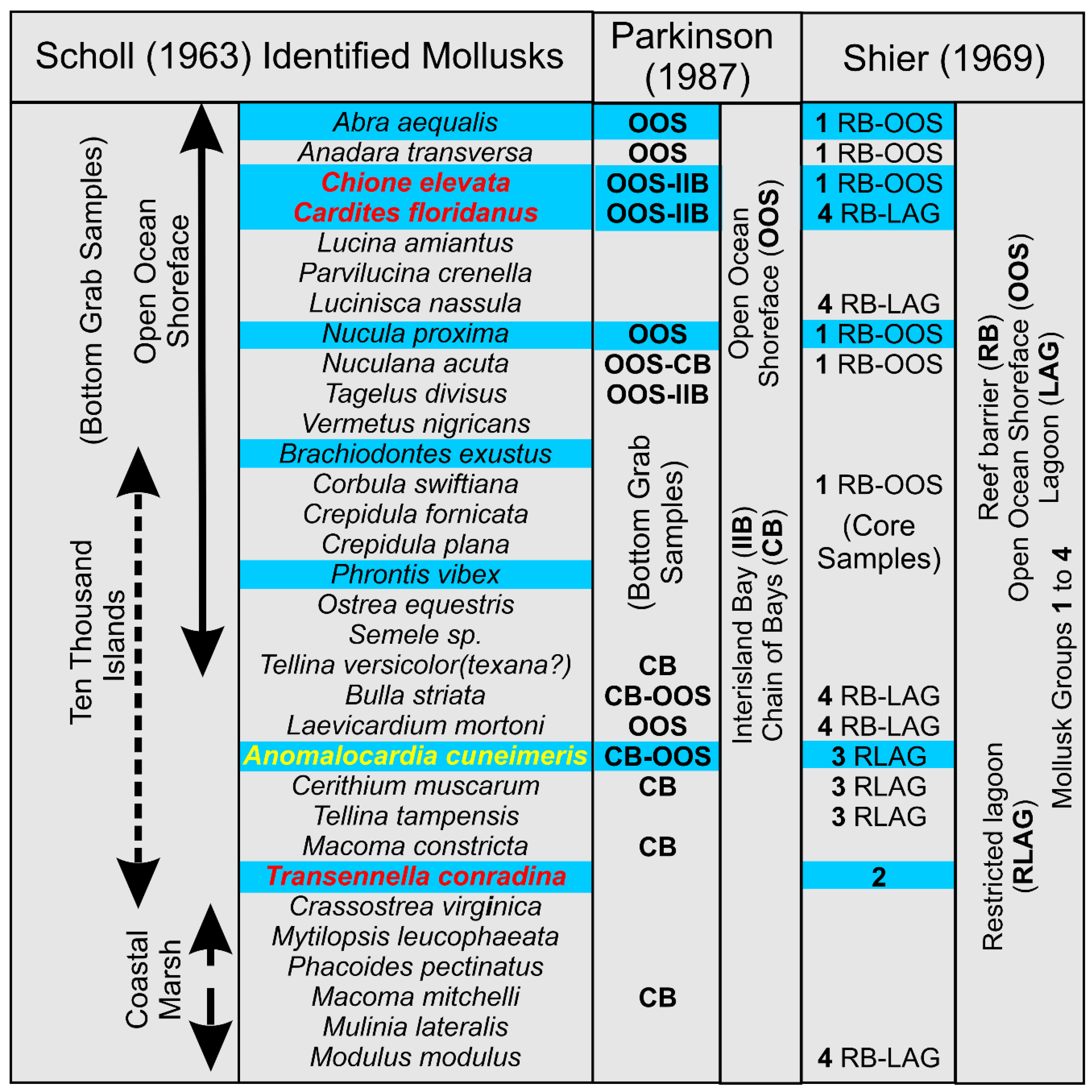

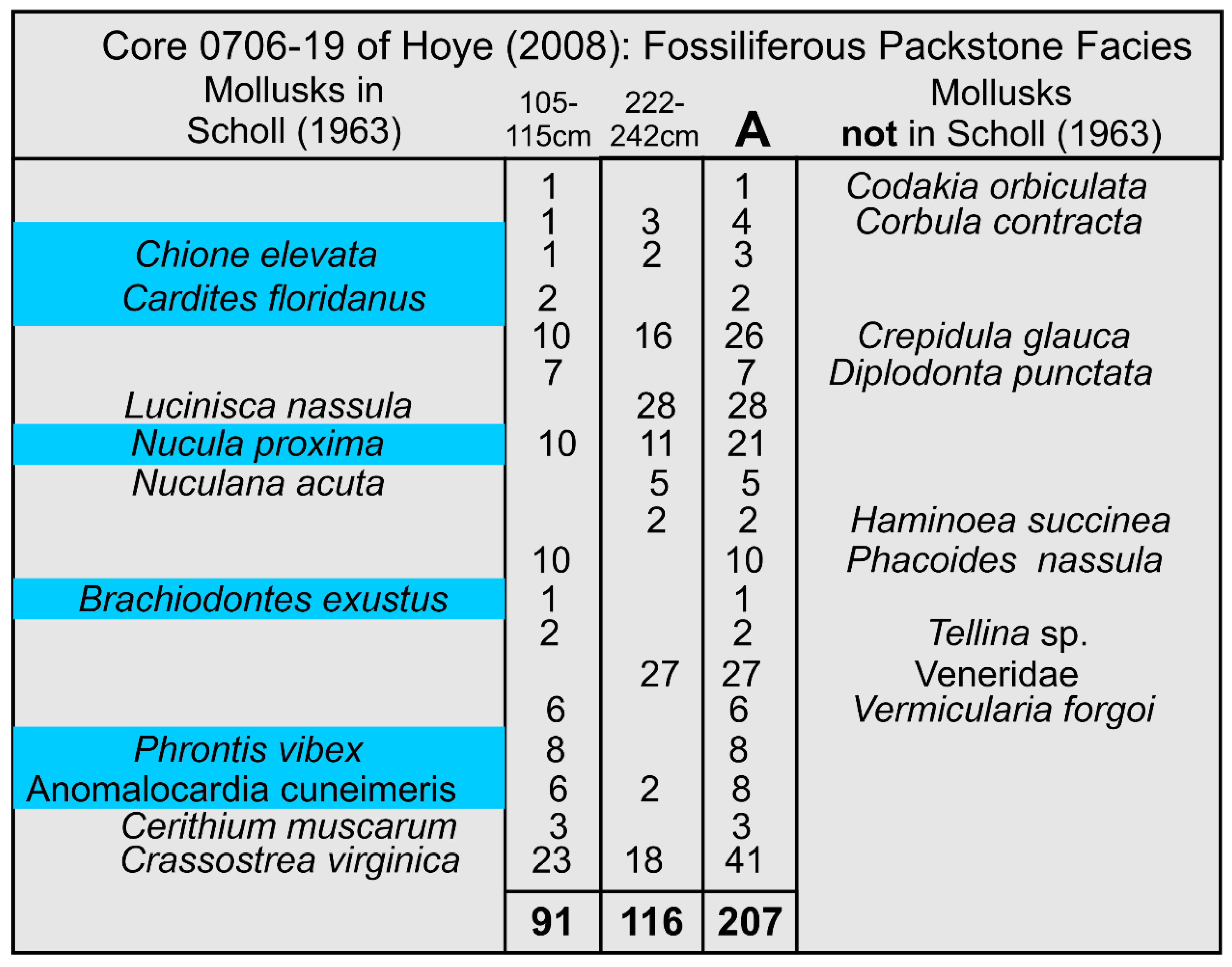

The number of species (63) identified in this Barfield Bay study is much greater than the number of species identified in studies of the nearby Ten Thousand Islands, both from bottom grab samples [

32,

33] and cores [

11,

34]. However, many of the 12 salinity-critical species of this Barfield Bay study are identified in samples of the open shoreface and proximal inner shelf depositional environments of the Ten Thousand Islands studies [11, 32, 33, and 34].

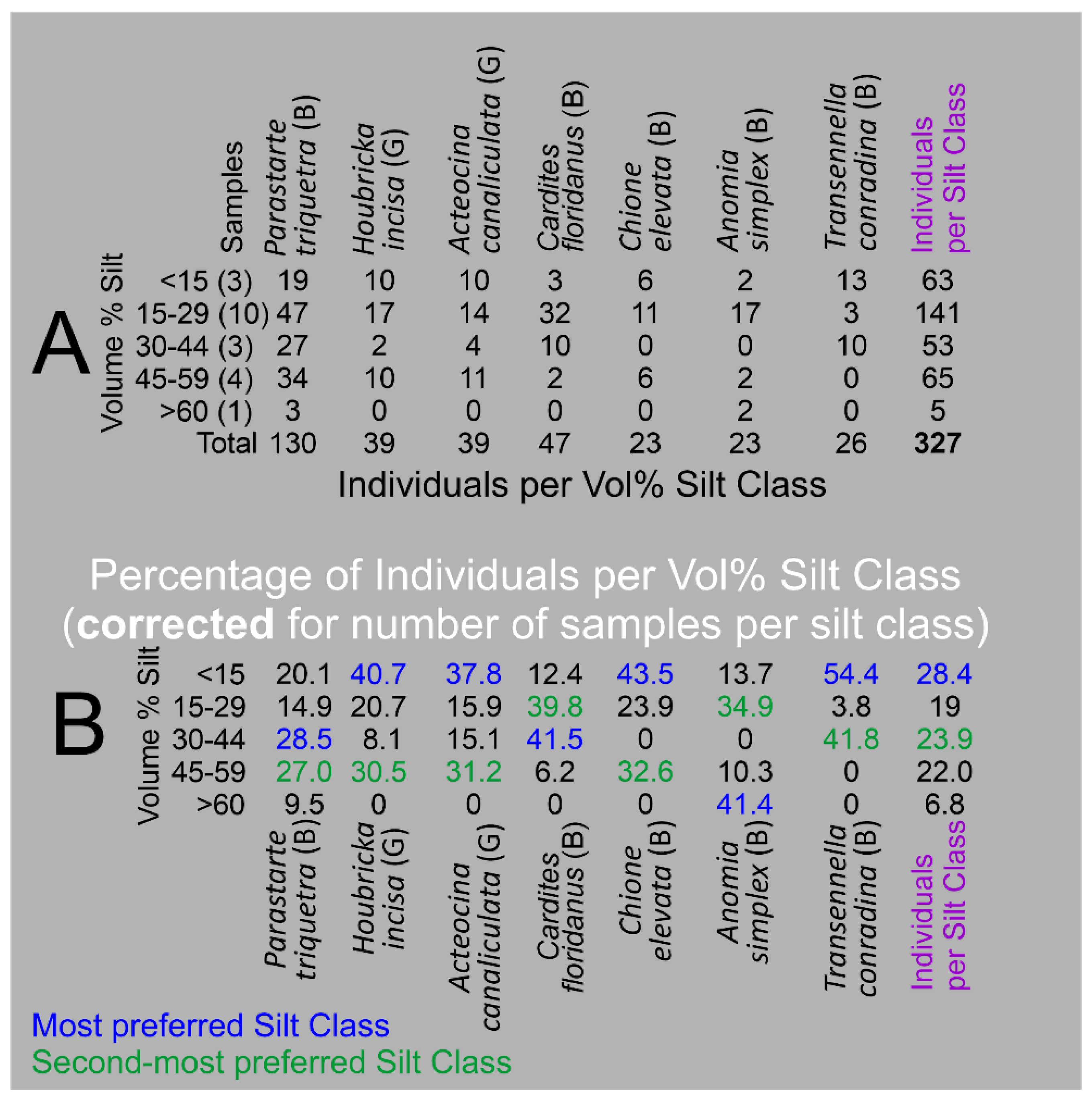

All twenty-one (21) Barfield Bay mollusk samples have a minimum of 5% volume silt. Five of the seven Critical Mollusk Species, with the exceptions of Cardites floridanus and Anomia simplex, “prefer” the >15 Volume % silt class. Anomia simplex is the only species that “prefers” the >60 Volume % silt class. All seven Critical Mollusk Species have a secondary mode in the 30-44 and 45-60 Volume % silt classes. As long as the volume % silt is below 60%, volume % silt appears not to be a major factor in the occurrence of the seven Critical Mollusks.

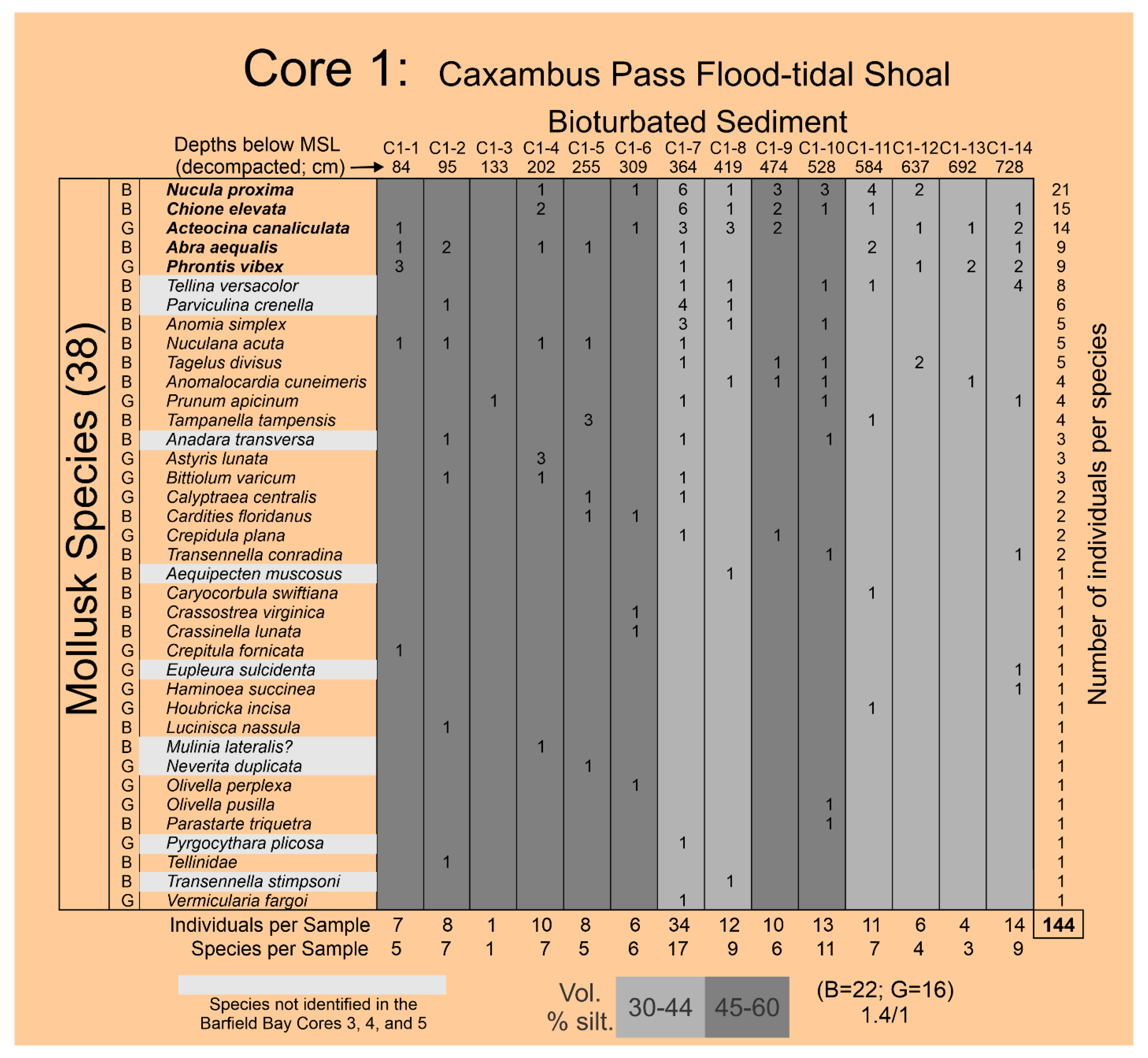

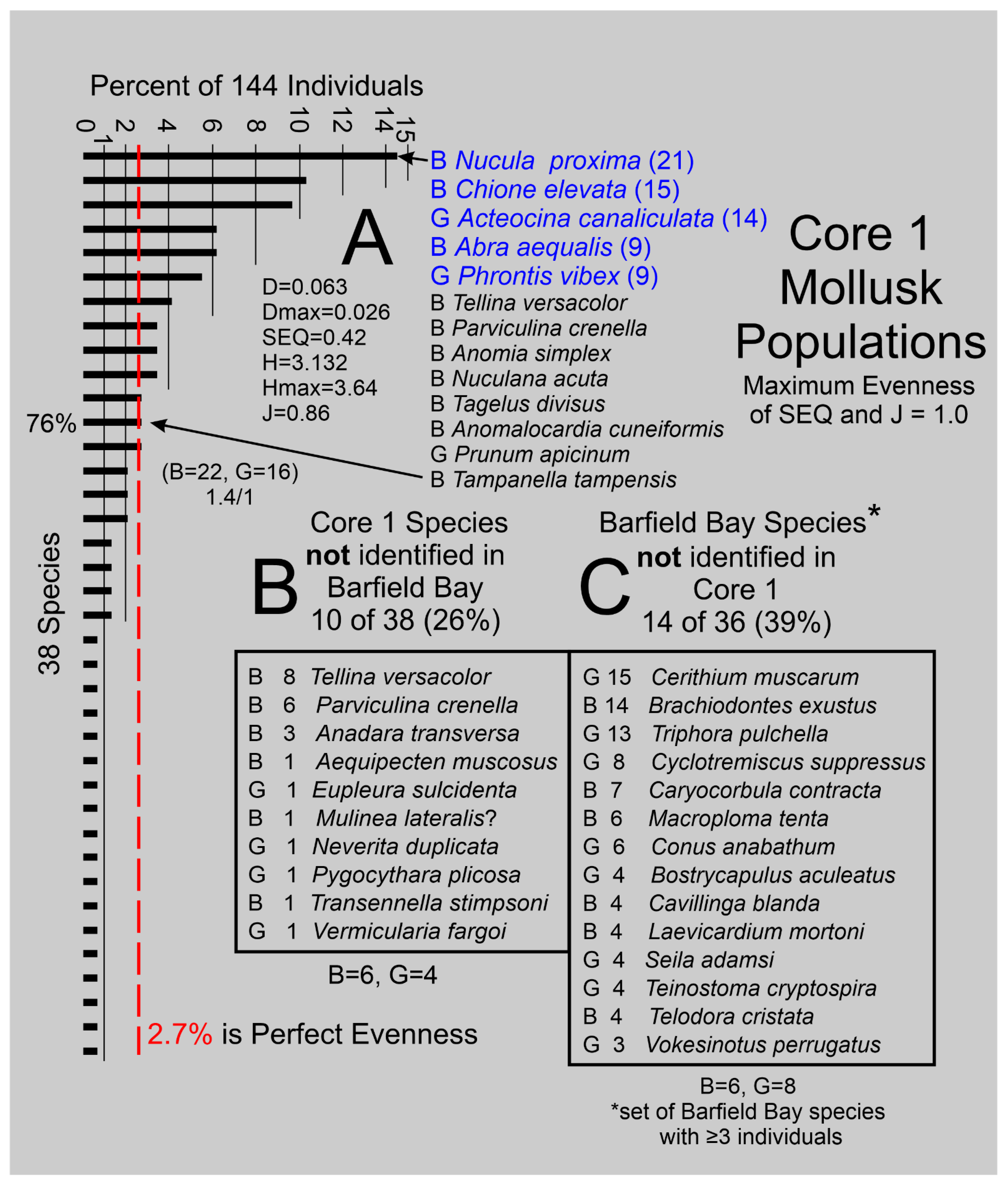

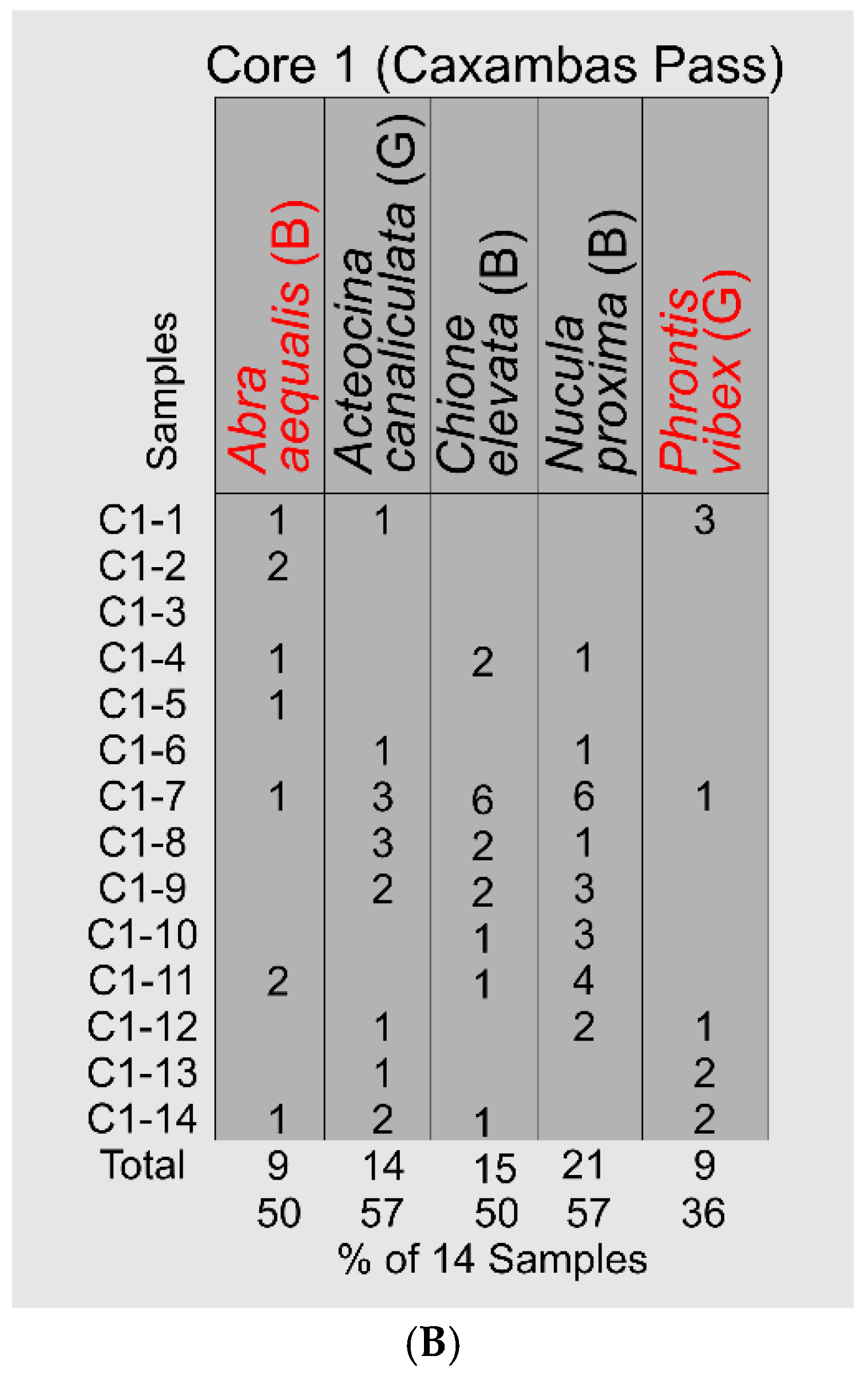

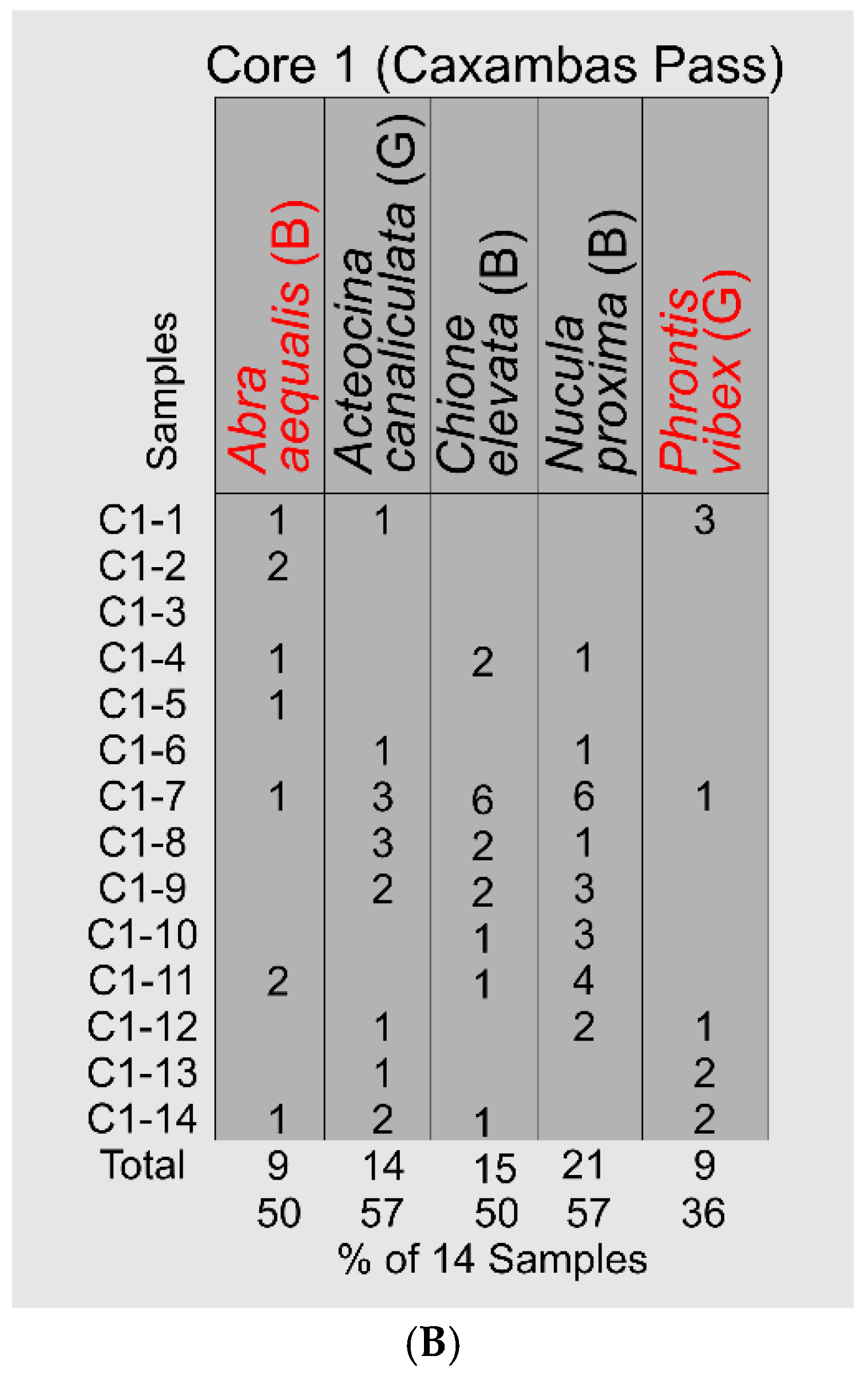

The identification of

38 species in the 14 samples of Core 1 in the Caxambas Pass flood-tidal delta is a good indication of a rich, diverse, molluscan fauna. However, the relative abundances of these species produce a markedly uneven distribution. The Shannon Diversity

H [

27] of 3.132 (Hmax of 3.64) and the Simpson Diversity D [

28] of 0.063 (0-1.0 range, maximum diversity = 0.0) indicate a relatively high degree of diversity. The Simpson Equitability [

28]

SEQ of 0.42 (range of 0 to 1 with 1= maximum evenness) indicates a moderate degree of unevenness or the dominance of a few species. The J [

29] index (equivalent to the

Shannon

Equitability

Index) is 0.86 (1=maximum evenness) which is twice the Simpson [

28] and indicates a high degree of evenness. However, both Shannon [

27] indices,

H and

SEI/

J, are sensitive to species richness and this Core 1 mollusk population has 38 species which apparently is sufficient to inflate this evenness index.

Nucula proxima (B)

, Chione elevata (B),

Acteocina canaliculata (G),

Abra aequalis (B), and

Phrontis vibex (G) are the dominant mollusks. However,

Parastarte triquetra and

Anomalocardia cuneimeris, the two most abundant species in the Barfield Bay mollusk population, occur as only one (0.07%) and four (2.8%) individuals, respectively, in the 144 shells identified in the Core 1 mollusk population. The Caxambas Pass Core 1 and the Barfield Bay mollusk populations, geographically juxtaposed and with the same long-term salinity as well as overall silt content, can only be considered to be similar.

The benthic foraminifera population of the Holocene, Barfield Bay sediment-fill is dominated by

Elphidium spp. with a secondary

Ammonia spp. component,

Figure 13. These two foraminifers are the main constituents of the adjacent Gullivan Bay shallow, nearshore region to the southeast [

36]. Miliolids, the most gulfward, benthic foraminifera [

36] are a significant component of the basal 1-1.5 m of Cores 3 and 5. The Caxambas Pass, flood-tidal delta Core 1 has a much more equal ratio of

Elphidium spp. and

Ammonia spp. throughout its 7-meter length with a slight occurrence of miliolids in the basal meter. The lack of a larger miliolid component, especially in the basal portion of in Core 1, is puzzling given that prior to the deposition of the Kice, Morgan, and Cape Romano barrier islands this location faced the open Gulf of Mexico.

7. Discussion and Interpretation of Mollusk Populations

The mollusk data collected in this study are interpreted to indicate an environment with a long-term salinity range of 25-32 psu. With the exception of the Crassostrea virginica shells, all mollusks identified in this study of the Barfield Bay, Holocene, sediment-fill are subtidal. No Crassostrea virginica clusters, or even portions of clusters small enough to fit into the 7-cm-diameter vibracore barrel, were identified. This argues that the oyster shells identified in this study can reasonably be considered clasts, originating from oysters encrusting the prop-roots of red mangrove (Rhizophora mangle) trees that covered the bay margins and/or nearby intertidal islets (as they do today), and were transported into the bay proper.

Sixty-three (63) mollusk species were identified in the 21 samples collected from the three Barfield Bay vibracores. This number of species indicates a species-rich and, by definition, diverse population with Shannon [

27] and Simpson [

28] diversity indices of

H of 3.27 (Hmax of 4.16) and

D of 0.075 (0-1.0 range, maximum diversity = 0.0), respectively. However, this mollusk population is very uneven with Polieu [

29] (equivalent to the

Shannon

Equitability

Index [

27]) and Simpson [

28] unevenness indices of J=0.78 (1=maximum evenness) and

SEQ=0.21 (range of 0 to 1 with 1= maximum evenness), respectively. It is this unevenness that is the more interesting. Previous mollusk populations identified in this region [

11,

32,

33,

34] are only broadly similar to this one identified in the Barfield Bay sediment-fill. The bivalve

Parastarte triquetra is the most abundant mollusk identified in the Barfield Bay population, however, its variability of occurrence in the twenty-one (21) mollusk samples is pronounced with a range of 0 to 30 individuals per sample, and it is represented in the fourteen (14) samples in the nearby Caxambas Pass Core 1 by a single individual. However, it is not identified in most other studies [11, 32, and 34]. It is mentioned in [

33] as being ubiquitous and prominent in surface grab samples, but no quantification is provided.

Anomalocardia cuneimeris, the second-most abundant mollusk in the Barfield Bay population, also has considerable variability in the twenty-one (21) mollusk samples with a 0 to 15 range in numbers per sample; furthermore, it is essentially the principal mollusk component of Tempestite Tp1. It likewise is present in the Caxambas Pass core (4 individuals) and in single-digit numbers in other studies [32, 33, and 34]. This pronounced variability suggests that none of the existing studies have adequately characterized the mollusk population, especially the variability of its constituent species, in the Barfield Bay/Ten Thousand Island region of southwest Florida. In addition, the “classic” indices of unevenness may not be useful in describing a population containing species that have geographically localized occurrences of numerous individuals.

The small “bump” in the Miliolid component of the benthic foraminifera population near the bases of the three Barfield Bay cores may be a subtle, possibly significant, sea level indicator. This “bump” is above the granular, terrestrial peat in Core 3,

Figure 13. This Miliolid concentration may suggest that the flooding event at the top of the terrestrial peat at the base of Core 3 submerged the entrance to Barfield Bay to depths sufficient for easier access of the distal, offshore Miliolid benthic foraminifera.

10. Holocene Sea level Record in the Barfield Bay Region

The granular, allogenic peat near the base of Core 3,

Figure 21 and

Figure 23, provides an upper bound for MSL 6900 years BP, namely, it can have been no higher than some 6.5 meters below present-day. This upper bound is somewhat deeper and older than the 5.5-meter depth and 6200 years BP age of wooden burial stakes from a submerged archaeological site in the Gulf of Mexico offshore of Manasota Key, Sarasota County, Florida [

42,

43,

44].

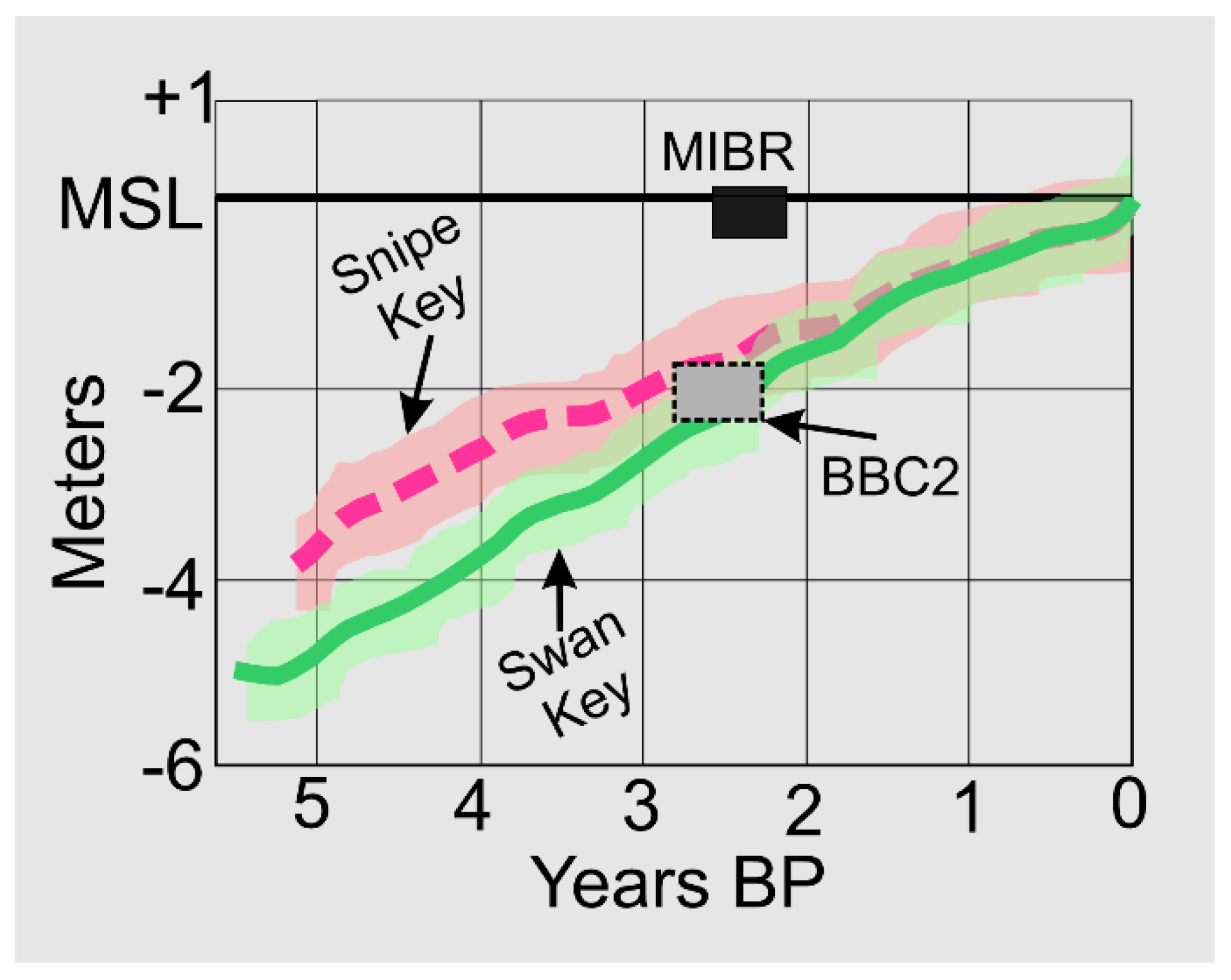

Cores 2, 6, and 7 that were taken on the terrestrial aeolian dune margins of Barfield Bay record a sea level transgression at the bases of their Holocene intra- and peritidal sections,

Figure 6B and

Figure 21. This transgressive surface occurs at elevations ranging from 162 cm to 210 cm below MSL. These different positions could well be 1) on a single sloping and/or irregular transgressive surface or 2) are three different surfaces altogether. In Core 2 a sample of mangrove roots and other vegetative debris located immediately on top of the transgressive surface at a depth of approximately 2-meters below MSL has a radiocarbon age of

2410±60 years BP,

Figure 6B and

Figure 20. A recent study [

3] determined that mangrove peat deposition in South Florida occurs in the upper 50 centimeters of the 1-meter intertidal zone, a conclusion based on 5 ground surveys and extensive Lidar mapping. Hence, this Barfield Bay sample of mangrove-derived, vegetative debris, absent any foraminifera data, was most likely deposited at a MSL position 2 to 2.5 meters below present-day. This Core 2 deposit fits on both of the relative sea level (RSL) curves [

3], each of which are based on 47 (Snipe Key) and 43 (Swan Key) C-14 ages of subsurface samples of mangrove peat and wood fragments that extend back to 5500 years BP, box BBC2 in

Figure 25.

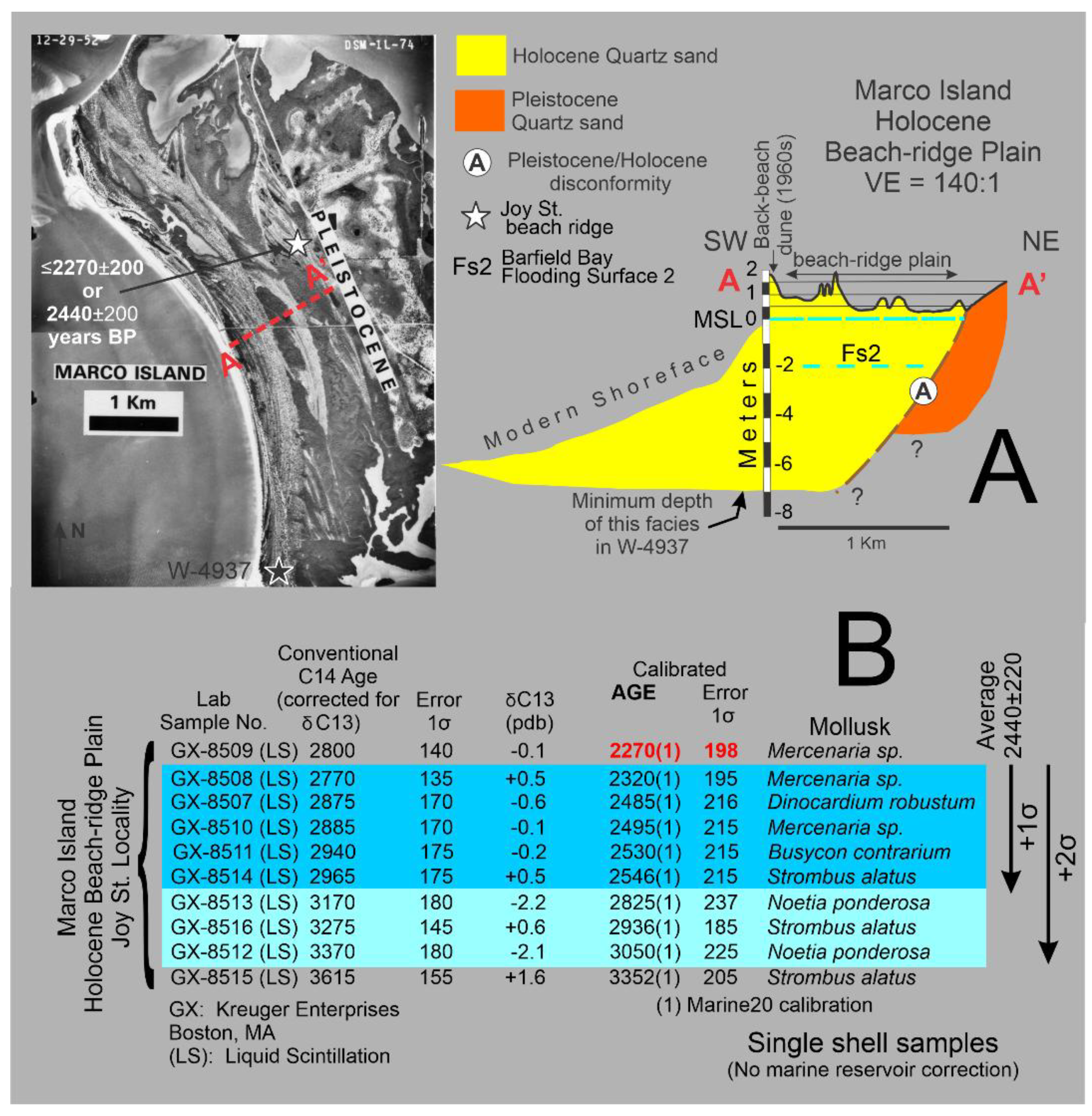

The beach-ridge that was located at what now is Joy Street, Marco Island, was the oldest ridge in the Holocene beach-ridge plain on the Gulf of Mexico margin of Marco Island,

Figure 26A. It was deposited at a mean sea level essentially equal to present-day based on the paradigm of equating beach-ridge swale elevation to mean-higher-high water (MHHW) [

45]. The youngest shell in the spectrum of ten radiocarbon dates made on ten individual shells collected at the Joy St. beach-ridge has an age of

2270±200 years BP (Cal), Panel B in

Figure 26B. The next five, younger shells have 1σ range-estimates that overlap the 1σ-range of the youngest shell. This 1σ “cluster” has a mean age of

2440±200 years BP that provides support for the hypothesis that the

2270±200 years BP shell is a reasonable estimate of the actual age of deposition and not just a maximum estimate. Thus, the Joy St. beach ridge and the Barfield Bay Fs2 flooding surface indicate two different MSL elevations over the same time interval,

Figure 26.

Two

independent and

coeval mean sea level indicators, located within 5-kilometers of each other, identified in a microtidal and low wave energy environment, producing contemporaneous elevation estimates differing by 2-meters call into question the ability of both techniques to estimate mean sea level. This apparent conundrum, however, may be caused by one technique interpolating continuity between discrete data points when continuity does not actually exist. Relative sea level (RSL) curves based on

subsurface, intertidal, vegetative debris [

3,

46] can promote interpretations of stratigraphic completeness, with few, if any, disconformities and, more importantly,

cannot identify the presence of highstand events. RSL curves from the southeastern US that are based on subsurface, intertidal data always result in a sloping, linear distribution of age/depth values such that younger material is always higher in elevation and older material is always lower ever since the pioneering work of D. W. Scholl and colleagues in the Ten Thousand Islands of southwest Florida [

47]. The depositional ages of beach ridges comprising Holocene barrier islands in the southeastern United States identify an intermittent sequence of sea level “highstands”, equal to present-day, that extend back 5000-6000 years BP [

45,

48,

49]. Thus, the apparent misfit between the contemporaneous MSL elevations predicted by Fs2 in Barfield Bay Core 2 and that of the Joy St. beach ridge can be explained by the existence of a short-term sea level “highstand” that was not and could not have been identified in a RSL curve [

3] based on subsurface, intertidal data.

Figure 26.

Panel A. The 1952 aerial photo shows Marco Island prior to residential development. The white star locates the beach-ridge site at Joy Street where nearshore-marine, mollusk shells were collected at the Joy St. locality during the dredging of a finger canal. The black star is the location of Water-well W-4937, which provides a minimum subsurface depth for the Holocene deposits. Profile

AA’ was made from a proprietary map with a 1-foot contour interval surveyed by the Deltona Corporation prior to development. Fs2 is the estimated MSL for Flooding surface 2 in Core 2. Panel B

. Radiocarbon date list on individual mollusk shells collected from the Joy St. locality. Marine reservoir corrections (MRC) were not applied in the Marine20 calibration because these MRC values for the Ten Thousand Islands region of southwest Florida are known only for

Crassostrea virginica shells [

50], none of which were analyzed in this study. The youngest shell in the spectrum of radiocarbon dates made on 10 shells collected at the Joy St. beach-ridge has an age of

2270±198 years BP. This is the

maximum possible age for this deposit, it could be much younger. The next five, younger shells, highlighted in blue, have 1σ range-estimates that overlap the 1σ-range of the youngest shell. The following next 3 younger shells (highlighted in light blue) have 2σ range-estimates that overlap the 2σ range of the youngest shell.

Figure 26.

Panel A. The 1952 aerial photo shows Marco Island prior to residential development. The white star locates the beach-ridge site at Joy Street where nearshore-marine, mollusk shells were collected at the Joy St. locality during the dredging of a finger canal. The black star is the location of Water-well W-4937, which provides a minimum subsurface depth for the Holocene deposits. Profile

AA’ was made from a proprietary map with a 1-foot contour interval surveyed by the Deltona Corporation prior to development. Fs2 is the estimated MSL for Flooding surface 2 in Core 2. Panel B

. Radiocarbon date list on individual mollusk shells collected from the Joy St. locality. Marine reservoir corrections (MRC) were not applied in the Marine20 calibration because these MRC values for the Ten Thousand Islands region of southwest Florida are known only for

Crassostrea virginica shells [

50], none of which were analyzed in this study. The youngest shell in the spectrum of radiocarbon dates made on 10 shells collected at the Joy St. beach-ridge has an age of

2270±198 years BP. This is the

maximum possible age for this deposit, it could be much younger. The next five, younger shells, highlighted in blue, have 1σ range-estimates that overlap the 1σ-range of the youngest shell. The following next 3 younger shells (highlighted in light blue) have 2σ range-estimates that overlap the 2σ range of the youngest shell.

11.Conclusions and Interpretations of the Origin, Sedimentology, Paleontology, and Holocene Stratigraphy of Barfield Bay, Marco Island Region, southwest Florida

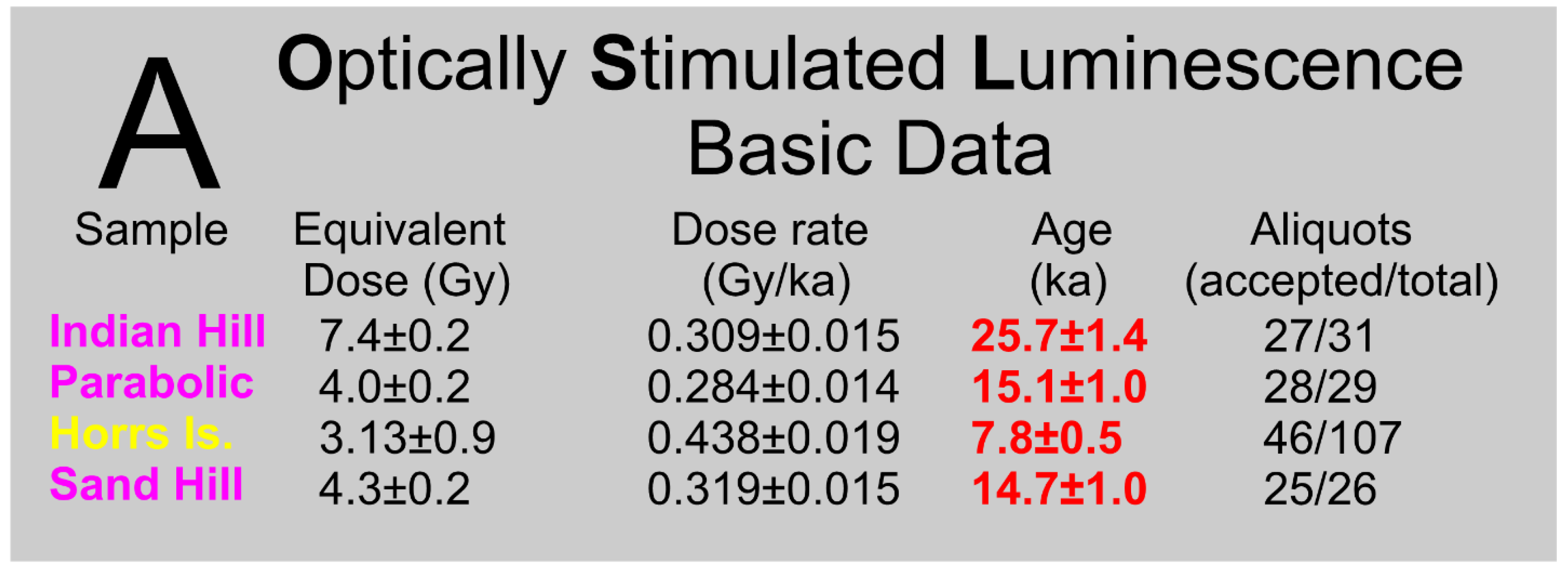

Barfield Bay fills the semi-elliptical center of a north-south-oriented parabolic dune that has a southern opening. The southern ends of the two parabolic arms terminate against east-west-oriented transverse dunes, the Indian Hill at the western arm and the Horrs Island at the eastern arm. Both transverse dunes have steeper, north-facing slopes which indicate northward migration. Optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) dates on the quartz-sand from the crests of these dunes indicate that the Indian Hill transverse dune is 26,000, the Barfield Bay parabolic dune is 15,000, and the Horrs Island transverse dune is 8000 years old. All these dunes are terrestrial in origin because the Gulf of Mexico shoreline was hundreds to many tens of kilometers farther west during the times of their formation. Local, pre-existing Pleistocene coastal sand deposits, MIS Stage 5E [

51], are the most reasonable local sources for the sand mobilized into these terrestrial, aeolian dunes. It is possible that the immediately adjacent Marco Island Pleistocene deposit, now interpreted as a barrier-island remnant, could also be a terrestrial aeolian dune given that its isopach pattern defines an isolated, elliptical, 10-meter-thick mass which is 4-5 times thicker than the Pleistocene coastal deposits on the adjacent Florida mainland.

Two possible alternative hypotheses for the origin of Barfield Bay are 1) a Carolina Bay, a shallow (2-4 meters deep) elliptical feature with a several meter-high sand rim, and 2) an impact crater. Both are untenable given the differences in ages of the terrestrial dunes that surround Barfield Bay because rim deposits of both Carolina Bays [

52,

53] and the proximal deposits of an ejecta blanket surrounding an impact crater [

54] must be the

same age. Carolina Bays typically occur in HP Groups, are no more than 4-meters deep, and are filled with significant quantities of vegetative material; furthermore, they do not contain marine mollusk shells [

52,

53].

The three vibracores that sampled the Barfield Bay sediment-fill penetrated between 5- and 7-meters of thoroughly bioturbated, silty, mollusk-shell-rich, quartz sand. Layered material consists of a handful of 5-7-centimeter-thick layers composed of mollusk-shells with minor silty sand matrix which are interpreted to be tempestites. In addition, the lowermost 23 cm of the deepest core has a 5-centimeter-thick layer of granular, terrestrial peat that is over- and underlain with mollusk-shell-rich, silty quartz-sand. It should be emphasized that 97% of the 17.82-meters of sediment recovered in these three cores consists of non-layered, bioturbated, mollusk-shell-rich, silty quartz-sand.

Granulometric analysis of forty (40) bay-fill and seventeen (17) terrestrial dune sediment samples resulted in the recognition of six, distinct, volume-percent histogram-patterns, four of which occur in both the bay-fill and terrestrial dune samples. The sand and silt fractions of all fifty-seven (57) samples were

NOT separated prior to grain-size analysis with a Mastersizer 2000 device; mollusk-shell material was removed by sifting through a 1-mm screen. The computer programs GRANULO [

1] and ROKE [

2] were used to identify 163 log-normal populations present within the sand and silt material comprising these 57 sediments. These 163 log-normal populations formed seven distinct, at the 2σ level, clusters on a mean versus standard deviation plot. The major sand cluster (41 members out of the 57 samples) of the coarsest, best sorted grain-sizes (2.03±0.17 Phi; 0.17±0.06 Phi units) contained log-normal populations from both bay-fill and terrestrial dune samples as did both the medium- (5.3±0.2 Phi; 0.54±0.1 Phi units) and fine-silt (7.1±0.3 Phi; 0.91±0.1 Phi units) clusters. These grain-size characteristics did

not discriminate depositional environments. The one non-expected, grain-size result is the identification of log-normal populations containing both very fine sand and coarse silt; undoubtedly the result of not separating sand and silt prior to the analysis of silt-rich, clastic sediment. The identification of these 163 log-normal components strongly suggests that prior to bioturbation the clastic sediment consisted of numerous, distinct layers of sand and silt. Furthermore, the result that the major sand component of both the bay-fill and terrestrial aeolian dunes is of the same grain-size suggests a similar, if not identical, source.

A total of 686 mollusk shells were identified in the 21 samples of the bioturbated silty quartz-sand in the three Barfield Bay cores and 388 in tempestite Tp1. Species diversity of the mollusks in the Barfield Bay sediment-fill, as indicated by the Shannon Diversity Index

H=3.227 (Hmax =4.16) [

27] and the Simpson Concentration Index

D=0.075 [

28] (possible range of 0-1 with 0 being more diverse), is high. However, these two diversity indices are known to over emphasize species richness (

S=63) at the expense of species abundance. The degree of evenness of individuals per species is indicated by the Shannon Evenness Index

SEI/J=0.78 (range of 0-1) [

27] which indicates a fairly high degree of evenness and the Simpson Equitability Index

SEQ=0.21 [

28] which indicates a low degree of evenness and the dominance of a few species. Thus, the 686 mollusk-shells identified in the 21 samples of the Barfield Bay sediment-fill come from a rich (S=63), diverse (D=0.21, H=3.23), and markedly uneven (SEQ=0.21) population that is dominated by the two bivalves,

Parastarte triquetra (B) and

Anomalocardia cuneimeris (B), with 154 and 61 identified individuals, respectively, out of 686 identified individuals. Seven critical species were identified on the basis of 1) occurring in all three Barfield Bay cores and 2) having 21 or more identified individuals so that they could occur in all 21 Barfield Bay mollusk samples. These Critical Mollusks are the following:

Parastarte triquetra (B),

Houbricka incisa (G),

Acteocina canaliculata (G),

Cardites floridanus (B),

Chione elevata (B),

Anomia simplex (B), and

Transennella conradina (B). Although

Anomalocardia cuneimeris (B) is the second-most abundant mollusk, it does not occur in all three cores and thus cannot be considered as a Critical Mollusk. These seven Critical Mollusks occur in 55% of their possible stratigraphic positions (147) in the 21 samples of the three Barfield Bay cores.

Environmental factors of salinity and silt content were evaluated for the Critical Mollusks and some additional abundant species of wide distribution. Salinity data collected in southwest Florida [

30,

31] for six of the Critical Mollusks and six additional abundant and widely (among the three cores and stratigraphically within the three cores) distributed species indicate a salinity range of 25-32 psu during the deposition of the Barfield Bay sediment-fill. From a substrate perspective, as long as the volume % silt is below 60%, which it overwhelmingly is, volume % silt appears not to be a major factor in the occurrence of the seven Critical Mollusks. Perhaps the most significant sedimentologic aspect of the identified mollusk population is that it is subtidal.

The Barfield Bay, silty quartz-sand, sediment-fill was most likely deposited in flood-tidal deltas that entered primarily through the Caxambas Pass opening and secondarily through the Blue Hill Creek region. Aerial photos clearly show the present-day Caxambas Pass main-channel as a bright, white ribbon (sand-rich, shallow) separating two darker (deeper, more silt-rich?) areas off to the southeast and northwest. This hypothesized flood-tidal delta interpretation is almost required by the geographic/geomorphic setting of the bay, namely, isolated from the open Gulf of Mexico and/or Gullivan Bay by terrestrial aeolian dunes several tens of meters high when the Holocene marine transgression arrived in this area. The surrounding aeolian dunes probably contributed a bare minimum of sand, and that only to their adjacent, mangrove-covered, intertidal fringes, because 1) they probably were covered with grasses, shrubs, and trees as they are today, and 2) the 2-5-kilometer fetch across Barfield Bay should produce only very small waves and only during extreme wind events. Basically, flood-tidal transport is the most reasonable mechanism to introduce sand and silt into this restricted depositional site. Core 4 is located in this main-channel region and indeed has a much lower, overall silt content. Cores 3 and 5 are located in the southeast and northwest basin areas, respectively, and both have much higher, overall silt contents. No bedding surfaces or indications of sedimentary structures were recognized in the bioturbated, mollusk-shell-rich sediment-fill sampled with the three, Barfield Bay vibracores. Original bedding and sedimentary structures have been destroyed by burrowing organisms, pelecypods and various marine invertebrates. The actual depositional processes can only be hypothesized. The sediment could have come in as turbid mixtures of sand and silt or separately, as an overwash-like sand sheet which was then followed by the suspension-settling of silt. The mollusk species comprising the identified mollusk population are all subtidal as are the rare tempestites. These two observations basically require that the entire Barfield Bay sediment-fill was deposited at subtidal depths.

The overall lack of sedimentary structures and various bedding surfaces essentially prohibits the organization of the Barfield Bay sediment-fill into distinct stratigraphic units. Only two verifiable flooding surfaces have been identified, and these are at the base and top of the sediment-fill. The basal surface (Fs1,

Figure 20) is located at a depth of 657-664 cm (MSL) and occurs on top of a terrestrial, allogenic, granular peat (

6900±50 years BP Cal) sandwiched between subtidal, shell-rich, quartz-sand. This terrestrial peat records a relative pause in the Holocene transgression followed by a flooding event and continued transgression. This sea level position is within the error estimates for elevation and age indicated by a Caribbean-wide RSL (relative sea level curve) [

55] but is beyond the range of the recent south Florida RSL curve [

45]. The other (Fs2,

Figure 6B and

Figure 20) is located at a depth of 210 cm (MSL) below the top of Core 2 and separates peritidal, silty quartz sand containing mangrove vegetative debris (

2410±60 years BP Cal) from the underlying quartz sand of the 7800-year-old Horrs Island terrestrial aeolian dune. The Fs2 sea level position is 2-meters lower than that indicated by the nearly coeval (

2270±200 years BP Cal), inter- and supratidal beach ridge on the Gulfward margin of Marco Island. This elevation difference for two coeval, equally rigorous sea level indicators can be reconciled with a “highstand” event that was not, and could not be, recorded in the recent RSL curve [

45] based on intertidal, subsurface core data. The pervasive bioturbation experienced by the Barfield Bay sediment-fill has destroyed all stratigraphic information except for the identification of flooding surfaces Fs1 and Fs2. Future studies seeking to extract sea level information from this exceptional 7-plus meters of Holocene marine deposits should concentrate on the narrow band, no more than the 150-meter distance between Cores 2 and 3, along the margins of the surrounding dunes. This band is the best location for the preservation of onlapping, intertidal deposits.

Figure 1.

This diagram shows the general terrestrial ecology of the Barfield Bay region in 1927 [

6] prior to its subsequent, extensive, and continual development which began in the1950s.

BB refers to Barfield Bay.

1 refers to the Indian Hill transverse dune;

2 refers to the Sand Hill dune (located 25 km north of Marco Island on the mainland);

3 refers to the Barfield Bay parabolic dune; and

4 refers to the Horrs Island transverse dune.

JI and

IoP refer to Johnson Island and the Isle of Palms, respectively, and

KMV refers to the historic Key Marco village.

Figure 1.

This diagram shows the general terrestrial ecology of the Barfield Bay region in 1927 [

6] prior to its subsequent, extensive, and continual development which began in the1950s.

BB refers to Barfield Bay.

1 refers to the Indian Hill transverse dune;

2 refers to the Sand Hill dune (located 25 km north of Marco Island on the mainland);

3 refers to the Barfield Bay parabolic dune; and

4 refers to the Horrs Island transverse dune.

JI and

IoP refer to Johnson Island and the Isle of Palms, respectively, and

KMV refers to the historic Key Marco village.

Figure 2.

Detailed map [

4] of the Barfield Bay region showing the 5-foot (1.5 meter) contour lines that define the terrestrial aeolian dunes that surround Barfield Bay. The two entrances into the bay are shown by the black letters

A and

B which identify the flood-dominant, tidal channels of Caxambas Pass and Blue Hill Creek, respectively. Intertidal shoals, shown in light blue, cover some 40% of the bay with the remainder being only 0.3-0.6 meters deep at MLW [

5]. The magenta-colored Indian Hill transverse dune and the Barfield Bay parabolic dune are Pleistocene in age, 24,000 and 15,000 years old, respectively. The yellow-colored Horrs Island transverse dune is early Holocene in age, 7800 years old. The orange-colored Marco Island is Pleistocene in age, either a coastal deposit 110,000 years old or, possibly, a late Pleistocene terrestrial aeolian dune formed sometime during the sea level fall after the 110,000-year-old highstand and the 24,000-year-old Indian Hill dune.

Figure 2.

Detailed map [

4] of the Barfield Bay region showing the 5-foot (1.5 meter) contour lines that define the terrestrial aeolian dunes that surround Barfield Bay. The two entrances into the bay are shown by the black letters

A and

B which identify the flood-dominant, tidal channels of Caxambas Pass and Blue Hill Creek, respectively. Intertidal shoals, shown in light blue, cover some 40% of the bay with the remainder being only 0.3-0.6 meters deep at MLW [

5]. The magenta-colored Indian Hill transverse dune and the Barfield Bay parabolic dune are Pleistocene in age, 24,000 and 15,000 years old, respectively. The yellow-colored Horrs Island transverse dune is early Holocene in age, 7800 years old. The orange-colored Marco Island is Pleistocene in age, either a coastal deposit 110,000 years old or, possibly, a late Pleistocene terrestrial aeolian dune formed sometime during the sea level fall after the 110,000-year-old highstand and the 24,000-year-old Indian Hill dune.

Figure 3.

Panels showing (1) the subsurface data points, (2) a structure contour map of the top of the Tamiami Limestone, (3) an isopach map of the Pleistocene coastal deposits, and (4) an isopach map of the Holocene coastal deposits.

Figure 3.

Panels showing (1) the subsurface data points, (2) a structure contour map of the top of the Tamiami Limestone, (3) an isopach map of the Pleistocene coastal deposits, and (4) an isopach map of the Holocene coastal deposits.

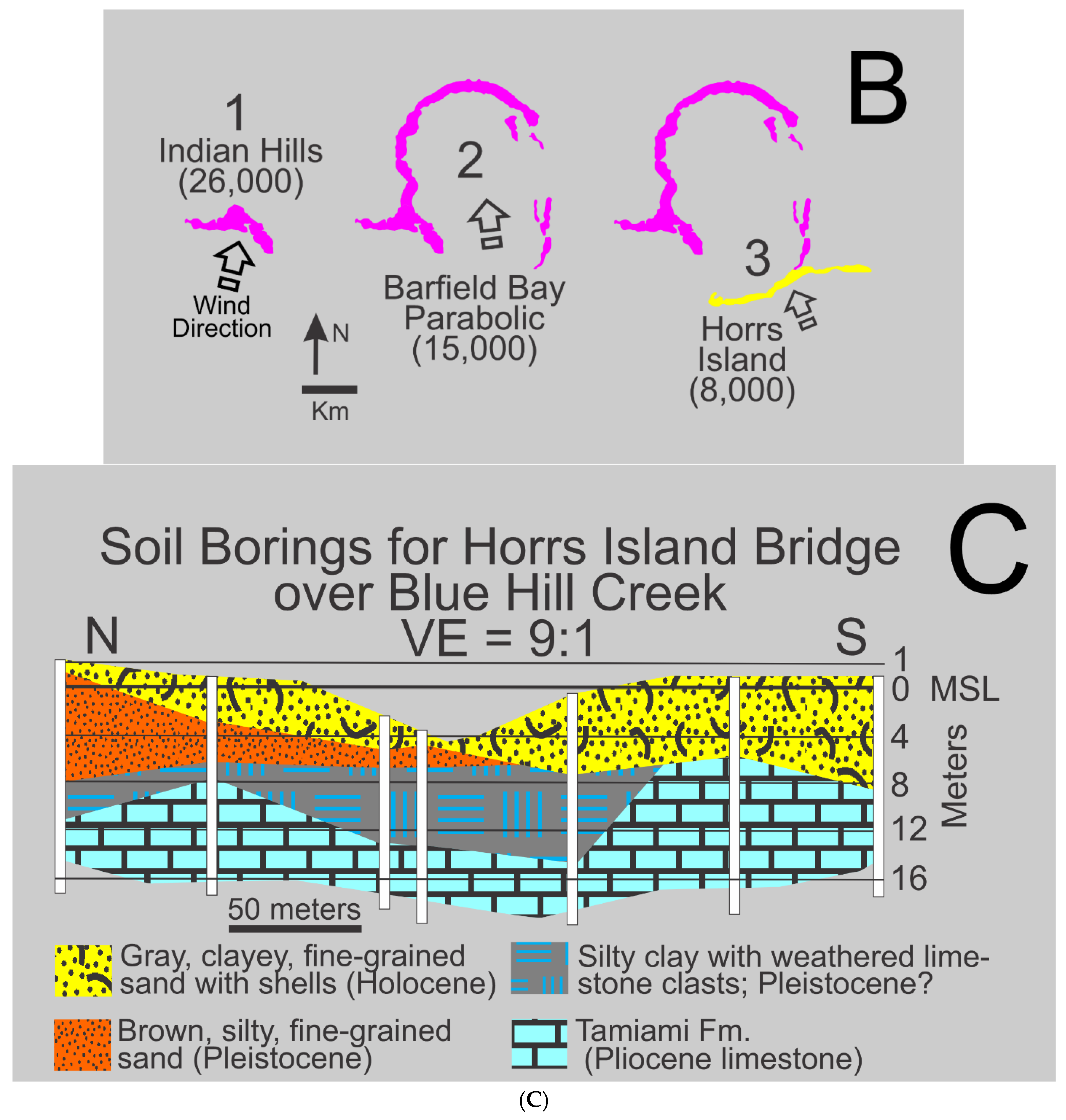

Figure 4.

A. The basic OSL data for the terrestrial aeolian dunes (Indian Hill Transverse, Barfield Bay Parabolic, and the Horrs Island Transverse) that surround Barfield Bay. In addition, the basic data are provided for the Sand Hill Transverse dune,

Figure 1. These analyses were done at Illinois Geological Survey OSL laboratory.

B. Chronological deposition of the three aeolian dunes that surround Barfield Bay, based on OSL dating of sand samples taken from the respective crests. Notice that thousands of years separate each interval of dune deposition. The open arrows show the sand transport directions for the three dunes.

C. A stratigraphic cross section across Blue Hill Creek on the eastern side of Barfield Bay where the intermittent eastern limb of the parabolic dune is located. Note the lack of Pleistocene sand deposits on the southern half of the section. This suggests that the Pleistocene sand deposits in the Barfield Bay region may not completely cover either the silty clay regolith with limestone clasts or the Tamiami Limestone itself.

Figure 4.

A. The basic OSL data for the terrestrial aeolian dunes (Indian Hill Transverse, Barfield Bay Parabolic, and the Horrs Island Transverse) that surround Barfield Bay. In addition, the basic data are provided for the Sand Hill Transverse dune,

Figure 1. These analyses were done at Illinois Geological Survey OSL laboratory.

B. Chronological deposition of the three aeolian dunes that surround Barfield Bay, based on OSL dating of sand samples taken from the respective crests. Notice that thousands of years separate each interval of dune deposition. The open arrows show the sand transport directions for the three dunes.

C. A stratigraphic cross section across Blue Hill Creek on the eastern side of Barfield Bay where the intermittent eastern limb of the parabolic dune is located. Note the lack of Pleistocene sand deposits on the southern half of the section. This suggests that the Pleistocene sand deposits in the Barfield Bay region may not completely cover either the silty clay regolith with limestone clasts or the Tamiami Limestone itself.

Figure 5.

Images of the silty quartz-sand sediment containing mollusk shells from the three Barfield Bay vibracores. These images are representative of the various silt amounts. Note the essentially random (?) arrangement of the mollusk shells; these images show the bioturbated texture that comprises the vast majority of the Holocene sediments that fill Barfield Bay. The white circles identify mollusk shells; the pink pelecypod in the upper left corner (white circle) of the Core 5 image is articulated. The homogeneous texture with no obvious stratification is interpreted to have resulted from intense bioturbation.

Figure 5.

Images of the silty quartz-sand sediment containing mollusk shells from the three Barfield Bay vibracores. These images are representative of the various silt amounts. Note the essentially random (?) arrangement of the mollusk shells; these images show the bioturbated texture that comprises the vast majority of the Holocene sediments that fill Barfield Bay. The white circles identify mollusk shells; the pink pelecypod in the upper left corner (white circle) of the Core 5 image is articulated. The homogeneous texture with no obvious stratification is interpreted to have resulted from intense bioturbation.

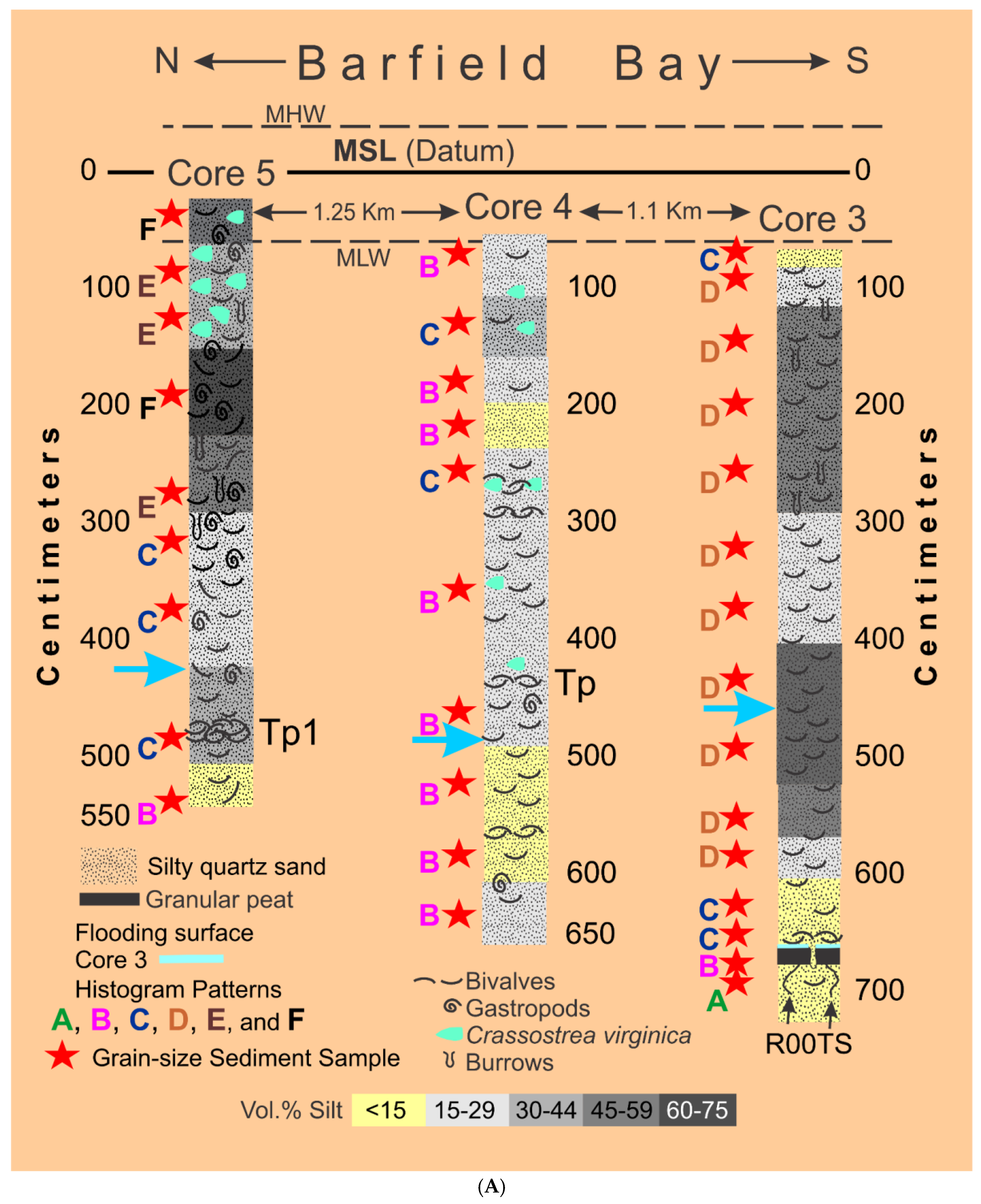

Figure 6.

A. The lithology and mollusk content of the three Barfield Bay vibracores that penetrated the Holocene sediment-fill. The silt-rich Cores 3 and 5 are located on the margins of the Southeast Basin (SEB,

Figure 2) and the Northwest Basin (NWB,

Figure 2), respectively. Core 4 is located in the main distributary channel region of the flood-tidal delta adjacent to the present-day Caxambas Pass,

Figure 2. The blue arrows show the locations of the core photos in

Figure 6. The largest concentration of

Crassostrea virginica shells is found in the upper 1.5 meters of Core 5. The decompacted depths are in centimeters.

B. Diagram showing the sediments in Cores 2, 6, and 7 which were taken in the mangrove fringe adjacent to the Barfield Bay Parabolic Dune and the Horrs Island Transverse Dune.

Crassostrea virginica shells are prominent in the upper several decimeters of these cores and were deposited from clusters that are present on the prop roots of red mangrove trees (

Rhizophora mangle). These Holocene sediments are a mixture of intertidal and shallow subtidal and can be best described as peritidal [

24]. The root casts that occur within the aeolian sand are probably not from red mangroves but rather from trees that populated these dunes prior to the Holocene marine transgression that flooded Barfield Bay. The vast majority of the quartz sand deposited above the Flooding Surface Disconformities most probably came from erosion of the adjacent aeolian dune and was not transported very far into Barfield Bay. Flooding surface Fs2 in Core 2 may not be correlative with the floodings surfaces in Cores 6 and 7.

Figure 6.

A. The lithology and mollusk content of the three Barfield Bay vibracores that penetrated the Holocene sediment-fill. The silt-rich Cores 3 and 5 are located on the margins of the Southeast Basin (SEB,

Figure 2) and the Northwest Basin (NWB,

Figure 2), respectively. Core 4 is located in the main distributary channel region of the flood-tidal delta adjacent to the present-day Caxambas Pass,

Figure 2. The blue arrows show the locations of the core photos in

Figure 6. The largest concentration of

Crassostrea virginica shells is found in the upper 1.5 meters of Core 5. The decompacted depths are in centimeters.

B. Diagram showing the sediments in Cores 2, 6, and 7 which were taken in the mangrove fringe adjacent to the Barfield Bay Parabolic Dune and the Horrs Island Transverse Dune.

Crassostrea virginica shells are prominent in the upper several decimeters of these cores and were deposited from clusters that are present on the prop roots of red mangrove trees (

Rhizophora mangle). These Holocene sediments are a mixture of intertidal and shallow subtidal and can be best described as peritidal [

24]. The root casts that occur within the aeolian sand are probably not from red mangroves but rather from trees that populated these dunes prior to the Holocene marine transgression that flooded Barfield Bay. The vast majority of the quartz sand deposited above the Flooding Surface Disconformities most probably came from erosion of the adjacent aeolian dune and was not transported very far into Barfield Bay. Flooding surface Fs2 in Core 2 may not be correlative with the floodings surfaces in Cores 6 and 7.

Figure 7.

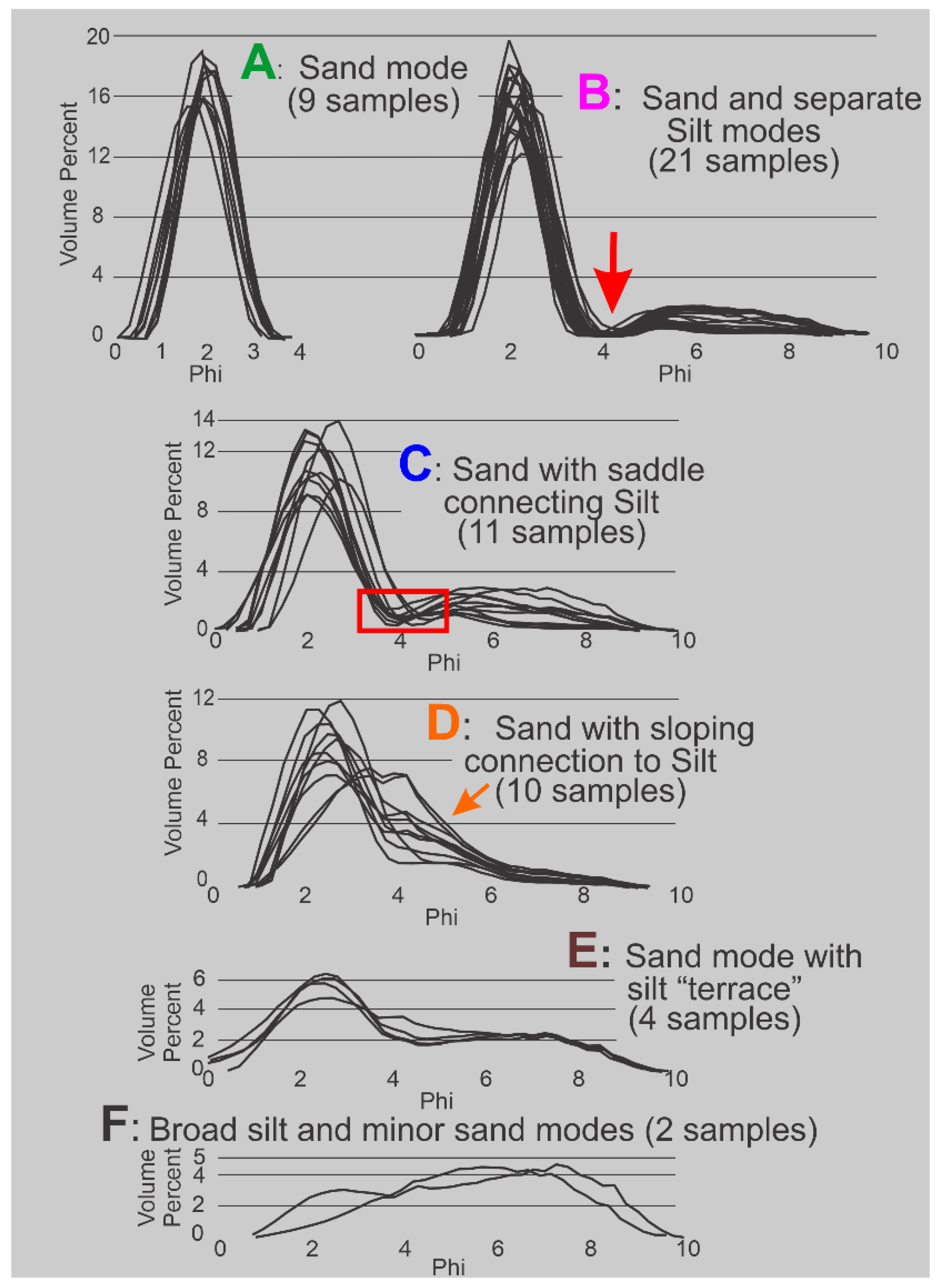

Volume percentage histograms of the quarter-Phi grain-size classes of the fifty-seven (57) sediment samples from the three Barfield Bay and the three aeolian dune vibracores. Based on their overall geometric shape or pattern these histograms can be placed into the six distinctly different histogram pattern (HP) HP Groups, A through F. The HP HP Group D samples are found only in the silt-rich portion of Core 3. Three of the HP HP Group E and all of the HP HP Group F samples are found in the silt-rich portion of Core 5. HP HP Groups A, B, and C are found in all six of the vibracores.

Figure 7.

Volume percentage histograms of the quarter-Phi grain-size classes of the fifty-seven (57) sediment samples from the three Barfield Bay and the three aeolian dune vibracores. Based on their overall geometric shape or pattern these histograms can be placed into the six distinctly different histogram pattern (HP) HP Groups, A through F. The HP HP Group D samples are found only in the silt-rich portion of Core 3. Three of the HP HP Group E and all of the HP HP Group F samples are found in the silt-rich portion of Core 5. HP HP Groups A, B, and C are found in all six of the vibracores.

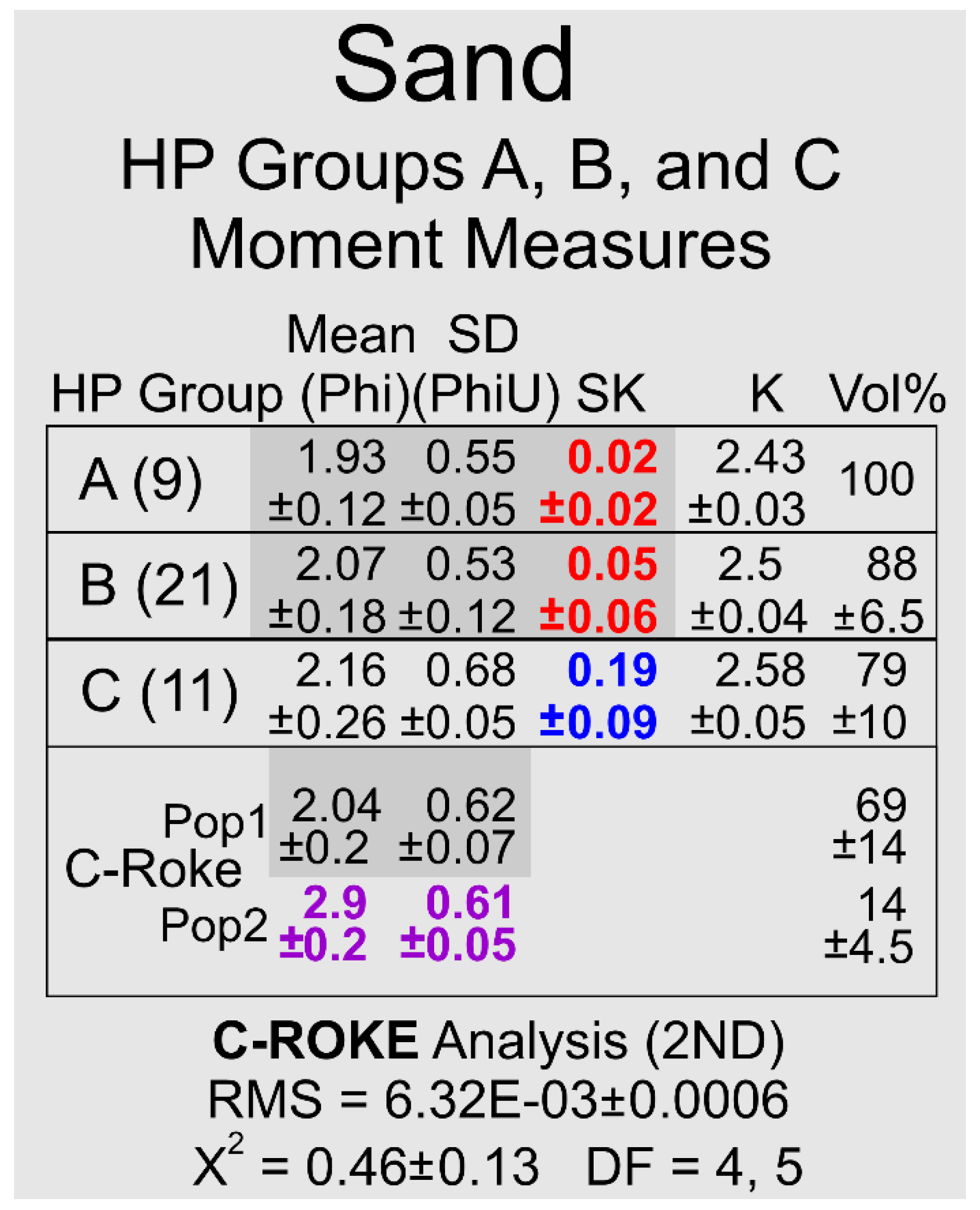

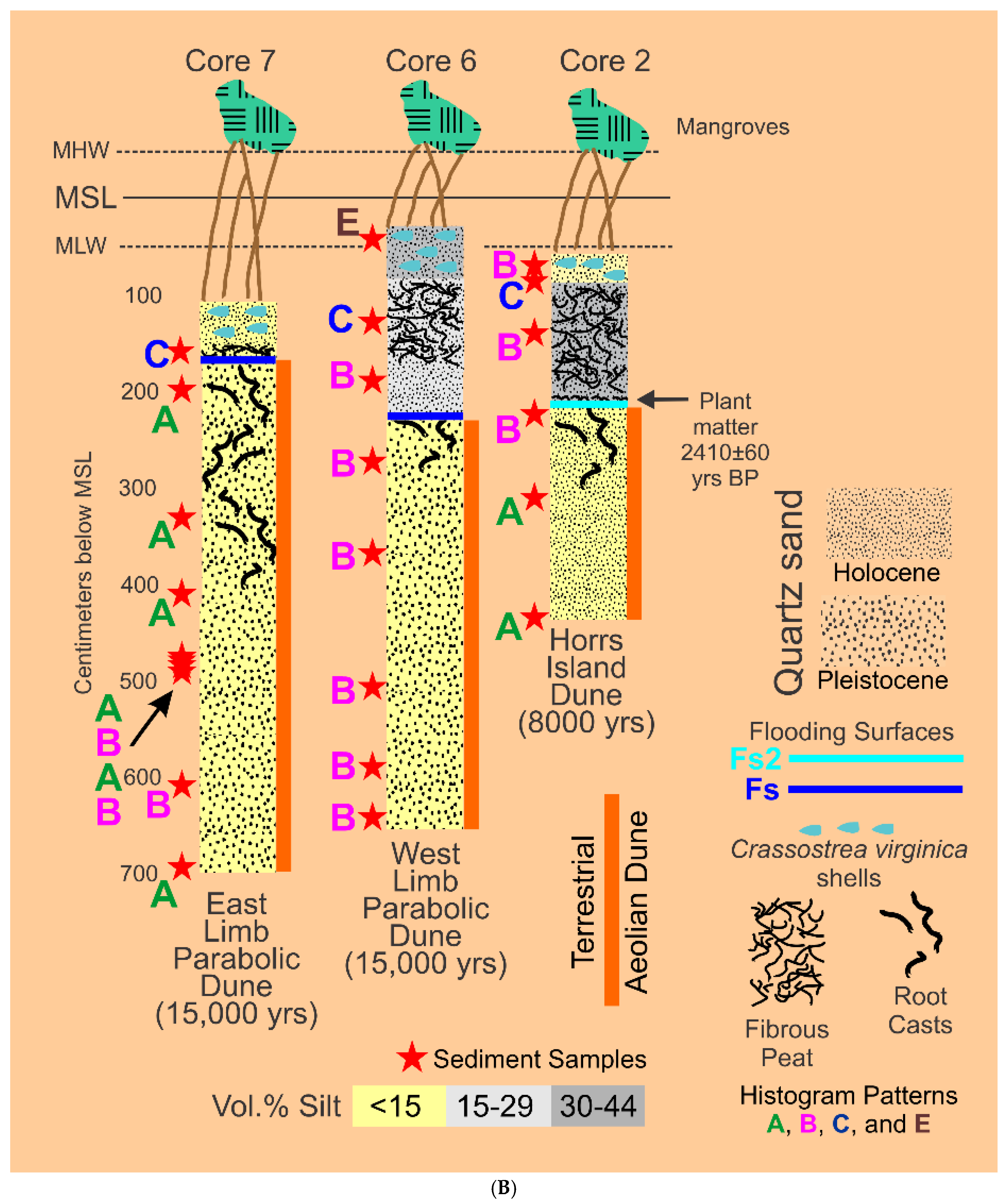

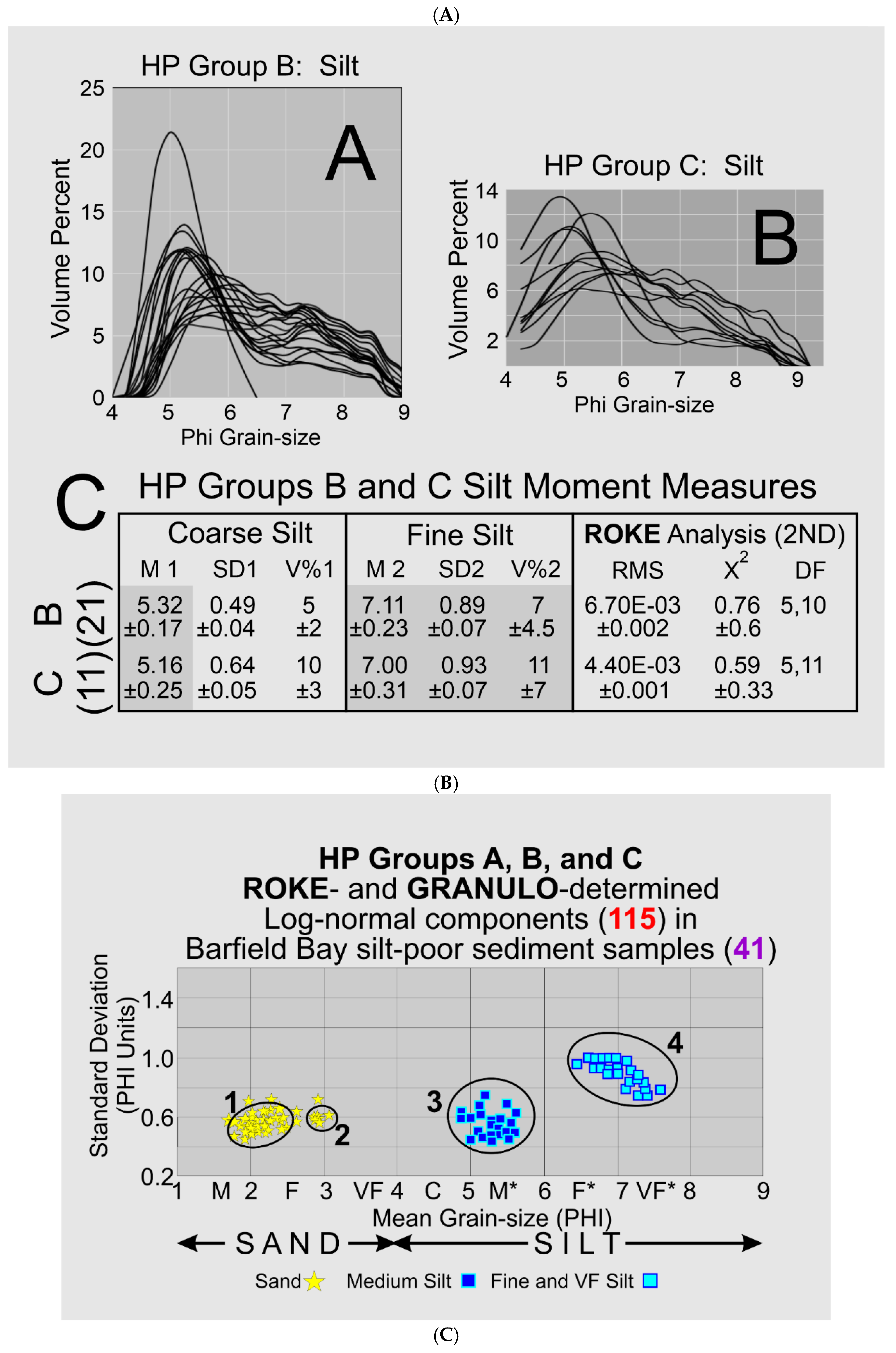

Figure 8.

A. HP Group-averaged, moment measures of the sand populations in HP Groups A, B, and C generated with GRANULO [

1]: (9) is the number of samples in the HP Group, Mean is a Phi grain-size, SD is the standard deviation (sorting) in Phi units, SK is the skewness, K is the kurtosis, and Vol% is the percentage of sand in the total sample volume (sand and silt). The specific column values highlighted in grey have overlapping standard deviations and thus can be considered statistically indistinguishable. RMS is root mean square of deviations and X

2 is a Chi Square value. DF is the degrees of freedom of the X

2 value. The null hypothesis that a distribution resulting from the combination of the 2 ROKE-identified normal distributions is different from the original distribution in the HP HP Group C sand mode was rejected at the 90% confidence level using a X

2 goodness-of-fit test.

B. Panels

A and

B. Volume percentage histograms of the silt fractions of HP Groups B and C samples. Note the polymodal character of these distributions with coarser and finer modes. Note that the HP Group C silt distributions have been truncated at their coarser ends; this truncation took place at the low point of the “saddle” connecting the sand and silt populations. This truncation has not affected the recognition of the coarse silt mode. Panel

C. HP HP Group-averaged, statistical moment measures of the two, ROKE-identified silt populations and HP Group-averaged RMS (root mean square) and X

2 values.

(21) and

(11) are the number of samples analyzed. M=Phi Mean grain-size, SD=standard deviation (sorting) in Phi units, V

*1=volume percentage of the silt component of total sediment sample, the numbers 1 and 2 refer to the respective component distributions.

(2ND) indicates that the ROKE program searched for two normal distributions. The null hypothesis that a distribution resulting from the combination of the 2 ROKE-determined normal distributions is different from the original distribution in the HP HP Groups B and C silt components was rejected at the 90% confidence level using X

2 goodness-of-fit tests. The gray background indicates those values that are statistically indistinguishable.

C. A bivariate plot of Mean grain-size versus Standard Deviation for the GRANULO and ROKE described and identified, respectively, log-normal populations in HP Groups A, B, and C; these three HP Groups are silt-poor relative to HP Groups D, E, and F. Cluster 1 contains 41 members, Cluster 2 contains 11 members, Cluster 3 contains 41 members, and Cluster 4 contains 40 members.

Figure 8.

A. HP Group-averaged, moment measures of the sand populations in HP Groups A, B, and C generated with GRANULO [

1]: (9) is the number of samples in the HP Group, Mean is a Phi grain-size, SD is the standard deviation (sorting) in Phi units, SK is the skewness, K is the kurtosis, and Vol% is the percentage of sand in the total sample volume (sand and silt). The specific column values highlighted in grey have overlapping standard deviations and thus can be considered statistically indistinguishable. RMS is root mean square of deviations and X

2 is a Chi Square value. DF is the degrees of freedom of the X

2 value. The null hypothesis that a distribution resulting from the combination of the 2 ROKE-identified normal distributions is different from the original distribution in the HP HP Group C sand mode was rejected at the 90% confidence level using a X

2 goodness-of-fit test.

B. Panels

A and

B. Volume percentage histograms of the silt fractions of HP Groups B and C samples. Note the polymodal character of these distributions with coarser and finer modes. Note that the HP Group C silt distributions have been truncated at their coarser ends; this truncation took place at the low point of the “saddle” connecting the sand and silt populations. This truncation has not affected the recognition of the coarse silt mode. Panel

C. HP HP Group-averaged, statistical moment measures of the two, ROKE-identified silt populations and HP Group-averaged RMS (root mean square) and X

2 values.

(21) and

(11) are the number of samples analyzed. M=Phi Mean grain-size, SD=standard deviation (sorting) in Phi units, V

*1=volume percentage of the silt component of total sediment sample, the numbers 1 and 2 refer to the respective component distributions.

(2ND) indicates that the ROKE program searched for two normal distributions. The null hypothesis that a distribution resulting from the combination of the 2 ROKE-determined normal distributions is different from the original distribution in the HP HP Groups B and C silt components was rejected at the 90% confidence level using X

2 goodness-of-fit tests. The gray background indicates those values that are statistically indistinguishable.

C. A bivariate plot of Mean grain-size versus Standard Deviation for the GRANULO and ROKE described and identified, respectively, log-normal populations in HP Groups A, B, and C; these three HP Groups are silt-poor relative to HP Groups D, E, and F. Cluster 1 contains 41 members, Cluster 2 contains 11 members, Cluster 3 contains 41 members, and Cluster 4 contains 40 members.

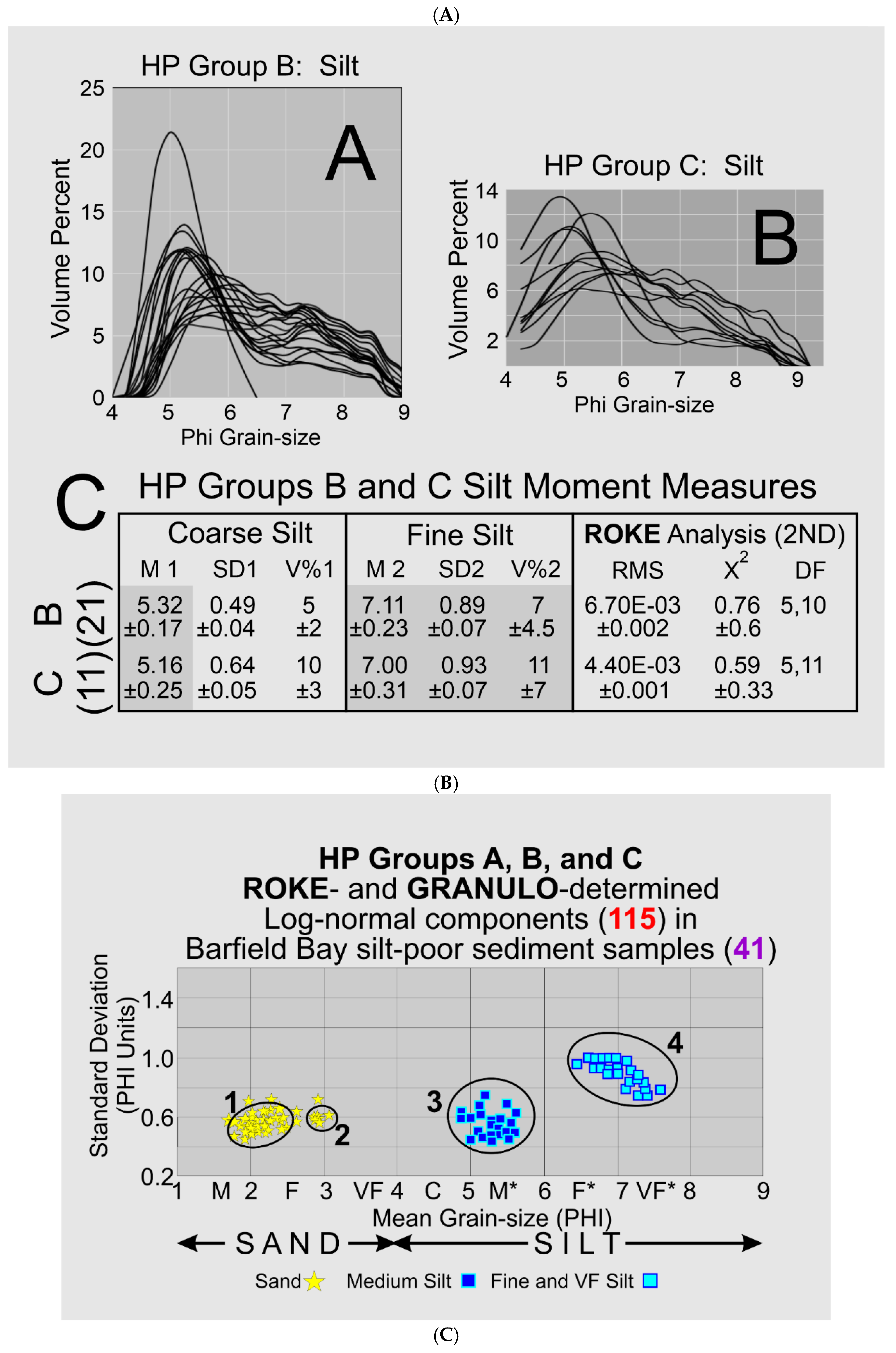

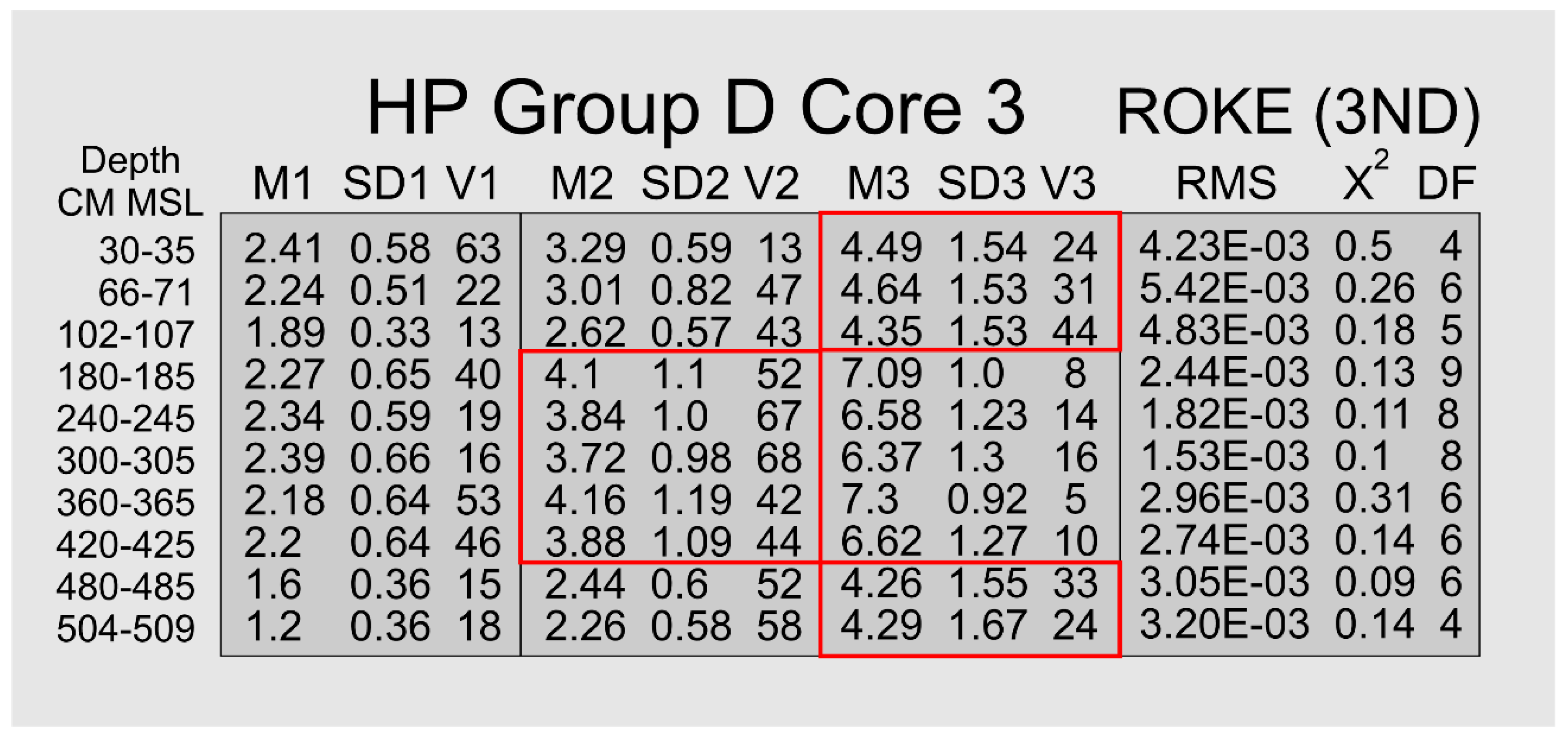

Figure 9.

The three ROKE-identified, normal distributions that can be combined to yield the histogram curves for the ten HP Group D samples. M=Phi Mean grain-size, SD=standard deviation in Phi units, V=volume percentage, RMS is root mean square, X2 is Chi square, DF is degrees of freedom. The numbers 1,2,3 arrange the constituent log-normal distributions in order of decreasing mean grain-size. ROKE only searches for normal distributions and thus there are no skewness or kurtosis values. The Depth numbers are in centimeters within the decompacted core below the Mean Sea level datum. (3 ND) indicates that the ROKE program searched for three normal distributions. The null hypothesis that respective combinations of the three ROKE-identified normal distributions are different from the original HP Group D distributions was rejected at the 90% level using a X2 goodness-of-fit test. The red outline boxes identify the populations that contain both very fine sand and coarse silt.

Figure 9.

The three ROKE-identified, normal distributions that can be combined to yield the histogram curves for the ten HP Group D samples. M=Phi Mean grain-size, SD=standard deviation in Phi units, V=volume percentage, RMS is root mean square, X2 is Chi square, DF is degrees of freedom. The numbers 1,2,3 arrange the constituent log-normal distributions in order of decreasing mean grain-size. ROKE only searches for normal distributions and thus there are no skewness or kurtosis values. The Depth numbers are in centimeters within the decompacted core below the Mean Sea level datum. (3 ND) indicates that the ROKE program searched for three normal distributions. The null hypothesis that respective combinations of the three ROKE-identified normal distributions are different from the original HP Group D distributions was rejected at the 90% level using a X2 goodness-of-fit test. The red outline boxes identify the populations that contain both very fine sand and coarse silt.

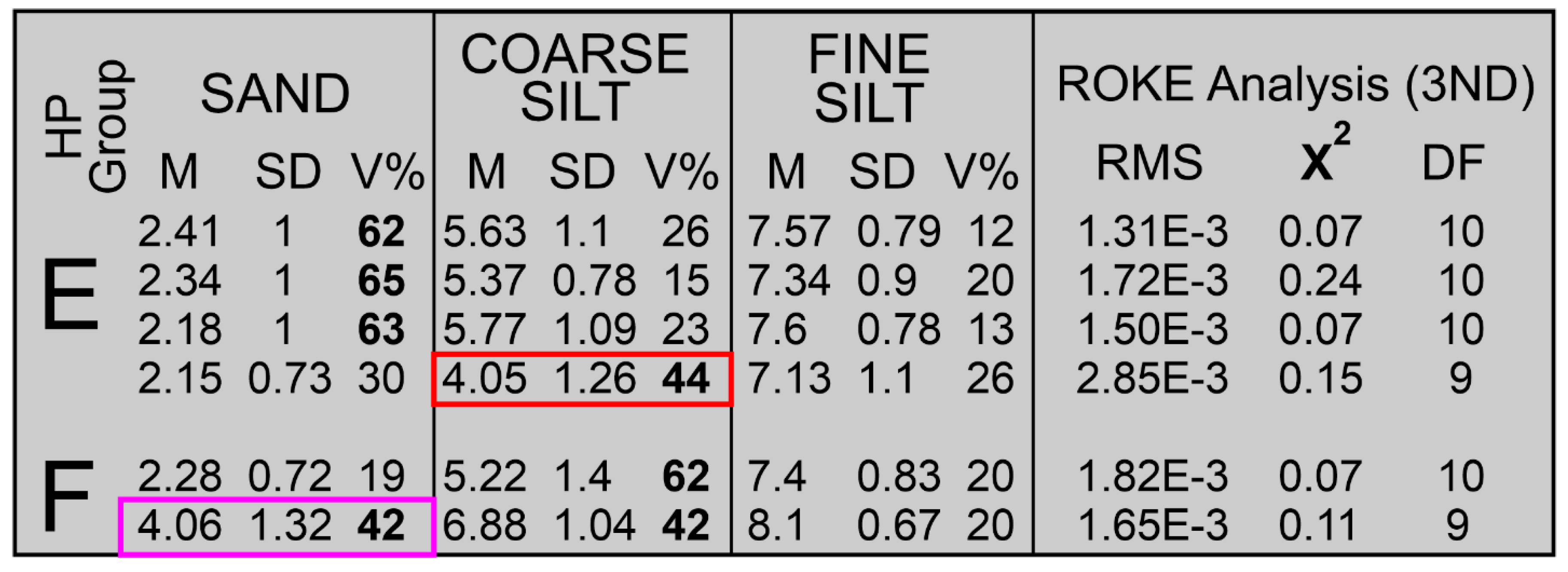

Figure 10.

The three ROKE-identified normal distributions that can be combined to yield the histogram curves for the four HP Group E and the two HP Group F samples. M= Phi Mean grain-size, SD=standard deviation in Phi units, V=volume percentage, RMS is root mean square, X2 is Chi square, and DF is degrees of freedom. ROKE only searches for normal distributions and thus there are no skewness or kurtosis values. The value in bold is the volumetrically largest component of a single sample. (3 ND) indicates that the ROKE program searched for three normal distributions. The null hypothesis that respective combinations of the three ROKE-identified normal distributions are different from the original HP Group E and F distributions was rejected at the 90% level using a X2 goodness-of-fit test.

Figure 10.

The three ROKE-identified normal distributions that can be combined to yield the histogram curves for the four HP Group E and the two HP Group F samples. M= Phi Mean grain-size, SD=standard deviation in Phi units, V=volume percentage, RMS is root mean square, X2 is Chi square, and DF is degrees of freedom. ROKE only searches for normal distributions and thus there are no skewness or kurtosis values. The value in bold is the volumetrically largest component of a single sample. (3 ND) indicates that the ROKE program searched for three normal distributions. The null hypothesis that respective combinations of the three ROKE-identified normal distributions are different from the original HP Group E and F distributions was rejected at the 90% level using a X2 goodness-of-fit test.

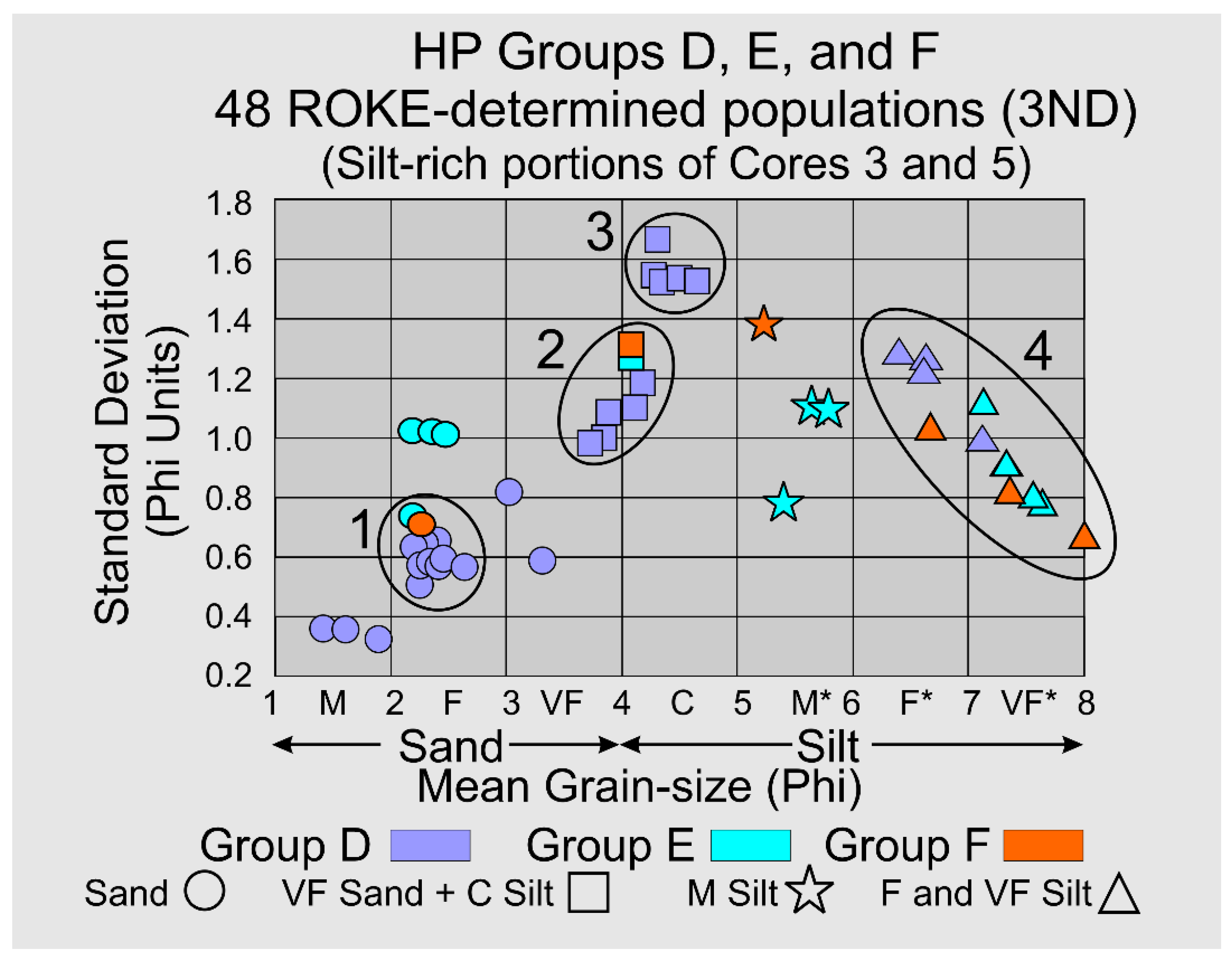

Figure 11.

A bivariate plot of Mean grain-size versus Standard Deviation for the ROKE described and identified, log-normal populations in HP Groups D, E, and F; these three HP Groups are silt-rich relative to HP HP Groups A, B, and C. Cluster 1 contains 11 members, Cluster 2 contains 7 members, Cluster 3 contains 5 members, and Cluster 4 contains 11 members.

Figure 11.

A bivariate plot of Mean grain-size versus Standard Deviation for the ROKE described and identified, log-normal populations in HP Groups D, E, and F; these three HP Groups are silt-rich relative to HP HP Groups A, B, and C. Cluster 1 contains 11 members, Cluster 2 contains 7 members, Cluster 3 contains 5 members, and Cluster 4 contains 11 members.

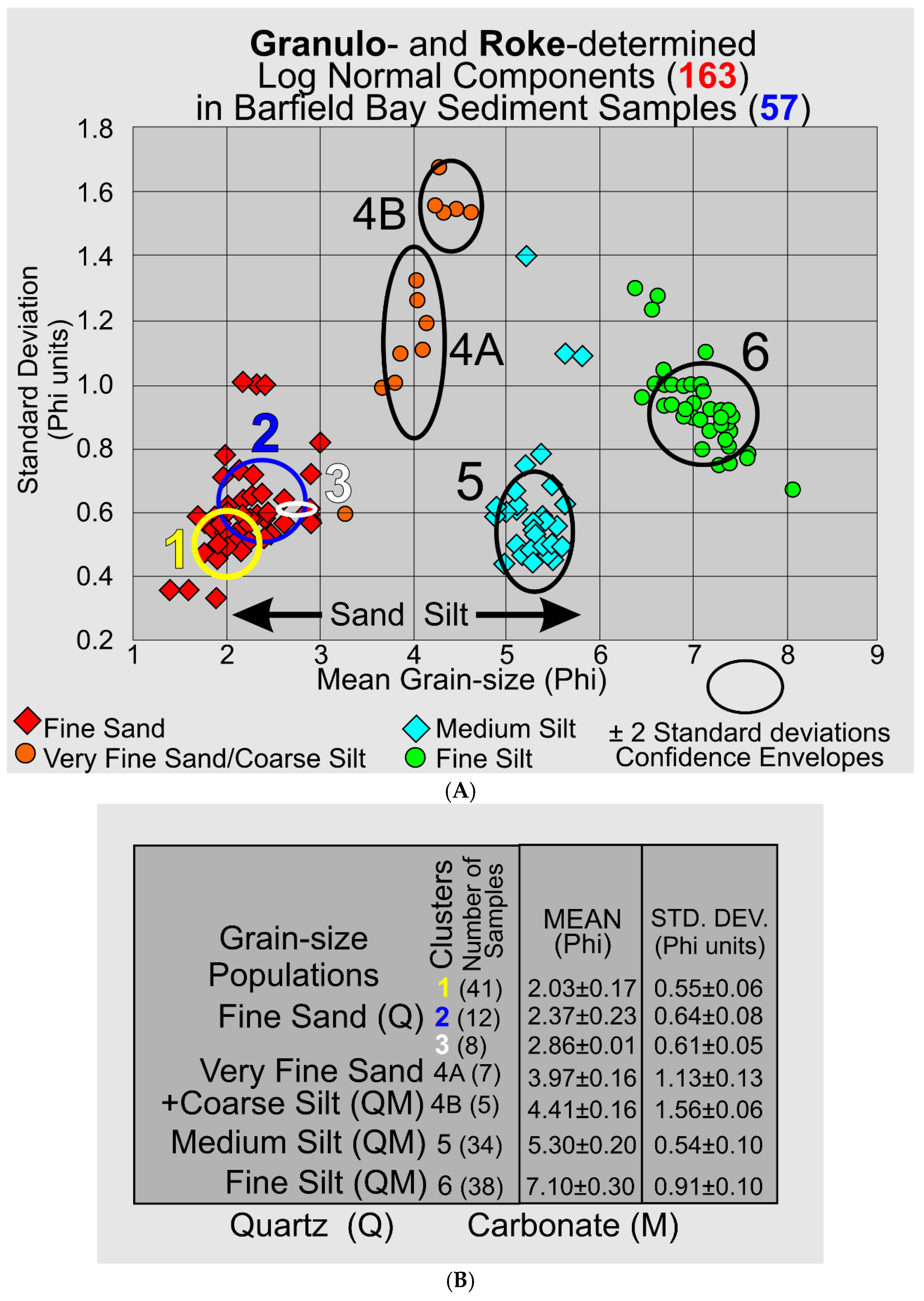

Figure 12.

A. A bivariate plot of mean grain-size (Phi) versus standard deviation (Phi units) for the 163 log-normal populations identified by the GRANULO and ROKE programs in sediment samples from the Barfield Bay sediment-fill and the surrounding terrestrial aeolian dunes. Clusters 1, 3, 5, and 6 are from the “silt poor” HP Groups A, B, and C; Clusters 2, 4A, and 4B are from the silt-rich HP Groups D, E, and F. Note that the two fine sand clusters 1 and 2 that contain the vast majority of fine-sand populations barely overlap.

B. Cluster-averaged mean grain-sizes and standard deviations for the seven clusters shown in

Figure 12A. Quartz (Q) is the primary mineralogy of the sand grains. Carbonate (M) is the (?) significant mineralogy of the silt grains [

13,

14] with siliciclastic material [

15] being present as well.

Figure 12.

A. A bivariate plot of mean grain-size (Phi) versus standard deviation (Phi units) for the 163 log-normal populations identified by the GRANULO and ROKE programs in sediment samples from the Barfield Bay sediment-fill and the surrounding terrestrial aeolian dunes. Clusters 1, 3, 5, and 6 are from the “silt poor” HP Groups A, B, and C; Clusters 2, 4A, and 4B are from the silt-rich HP Groups D, E, and F. Note that the two fine sand clusters 1 and 2 that contain the vast majority of fine-sand populations barely overlap.

B. Cluster-averaged mean grain-sizes and standard deviations for the seven clusters shown in

Figure 12A. Quartz (Q) is the primary mineralogy of the sand grains. Carbonate (M) is the (?) significant mineralogy of the silt grains [

13,

14] with siliciclastic material [

15] being present as well.

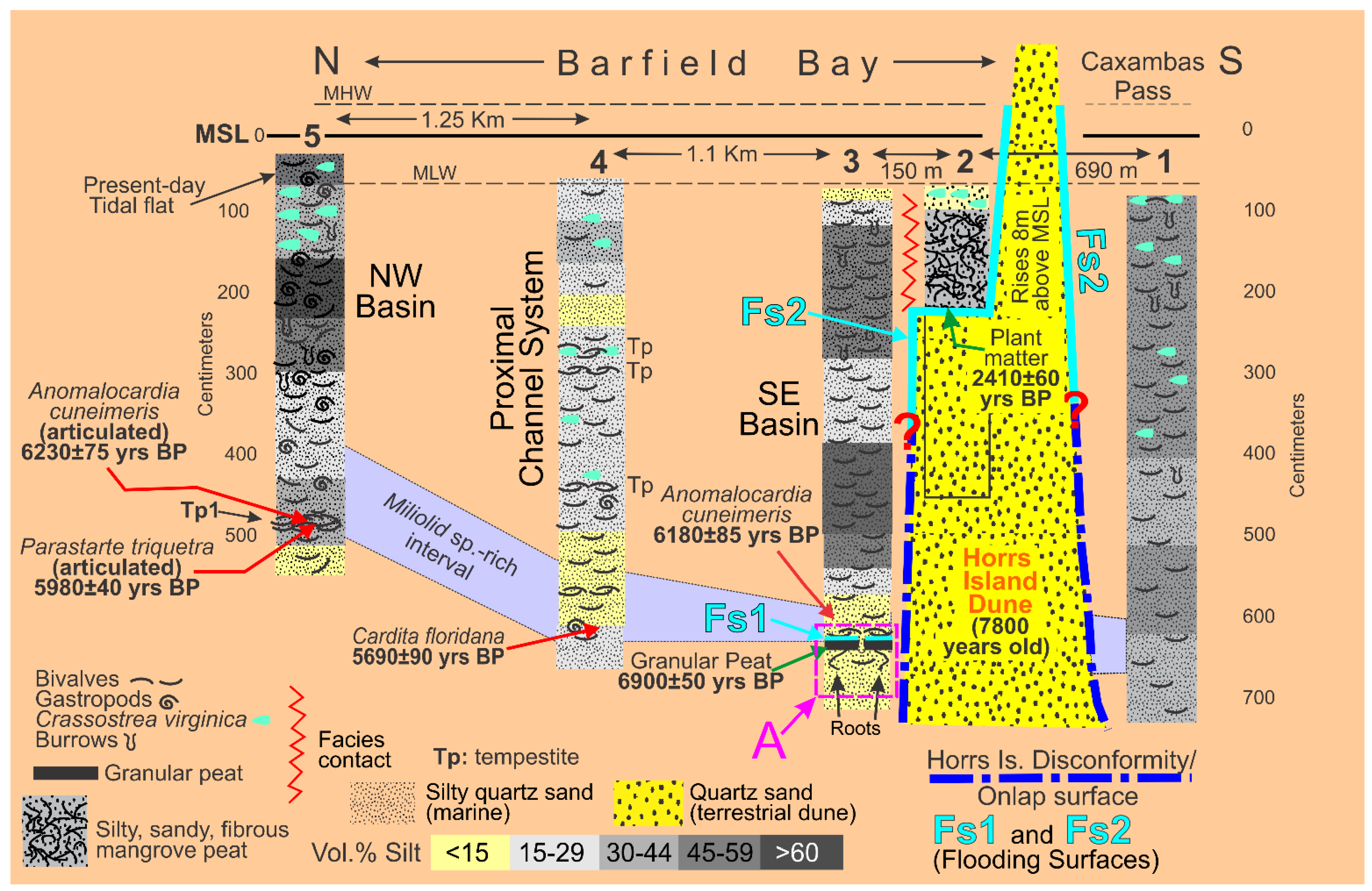

Figure 13.

A North/South stratigraphic cross-section through Barfield Bay, across the Horrs Island dune, and out into Caxambas Pass showing Cores 5, 4, 3, 2, and 1. The red-filled circles mark the locations of the 21 mollusk samples of the bioturbated Barfield Bay sediment-fill and the locations of the 14 mollusk samples in Core 1. The green stars mark the locations of the 46 foraminifera samples. The distributions of the benthic foraminiferans Ammonia sp., Elphidium spp., and the miliolids are shown by the shaded vertical bands. The core depths are decompacted and have a MSL datum. The mollusk symbol occurrences reflect descriptions of the actual core and not the specific mollusk samples; there are more Crassostrea virginica than would be expected given the sample identifications. At present there are no data that allow for the placement of Core 2 and Core 3 flooding surfaces into adjacent cores.

Figure 13.

A North/South stratigraphic cross-section through Barfield Bay, across the Horrs Island dune, and out into Caxambas Pass showing Cores 5, 4, 3, 2, and 1. The red-filled circles mark the locations of the 21 mollusk samples of the bioturbated Barfield Bay sediment-fill and the locations of the 14 mollusk samples in Core 1. The green stars mark the locations of the 46 foraminifera samples. The distributions of the benthic foraminiferans Ammonia sp., Elphidium spp., and the miliolids are shown by the shaded vertical bands. The core depths are decompacted and have a MSL datum. The mollusk symbol occurrences reflect descriptions of the actual core and not the specific mollusk samples; there are more Crassostrea virginica than would be expected given the sample identifications. At present there are no data that allow for the placement of Core 2 and Core 3 flooding surfaces into adjacent cores.

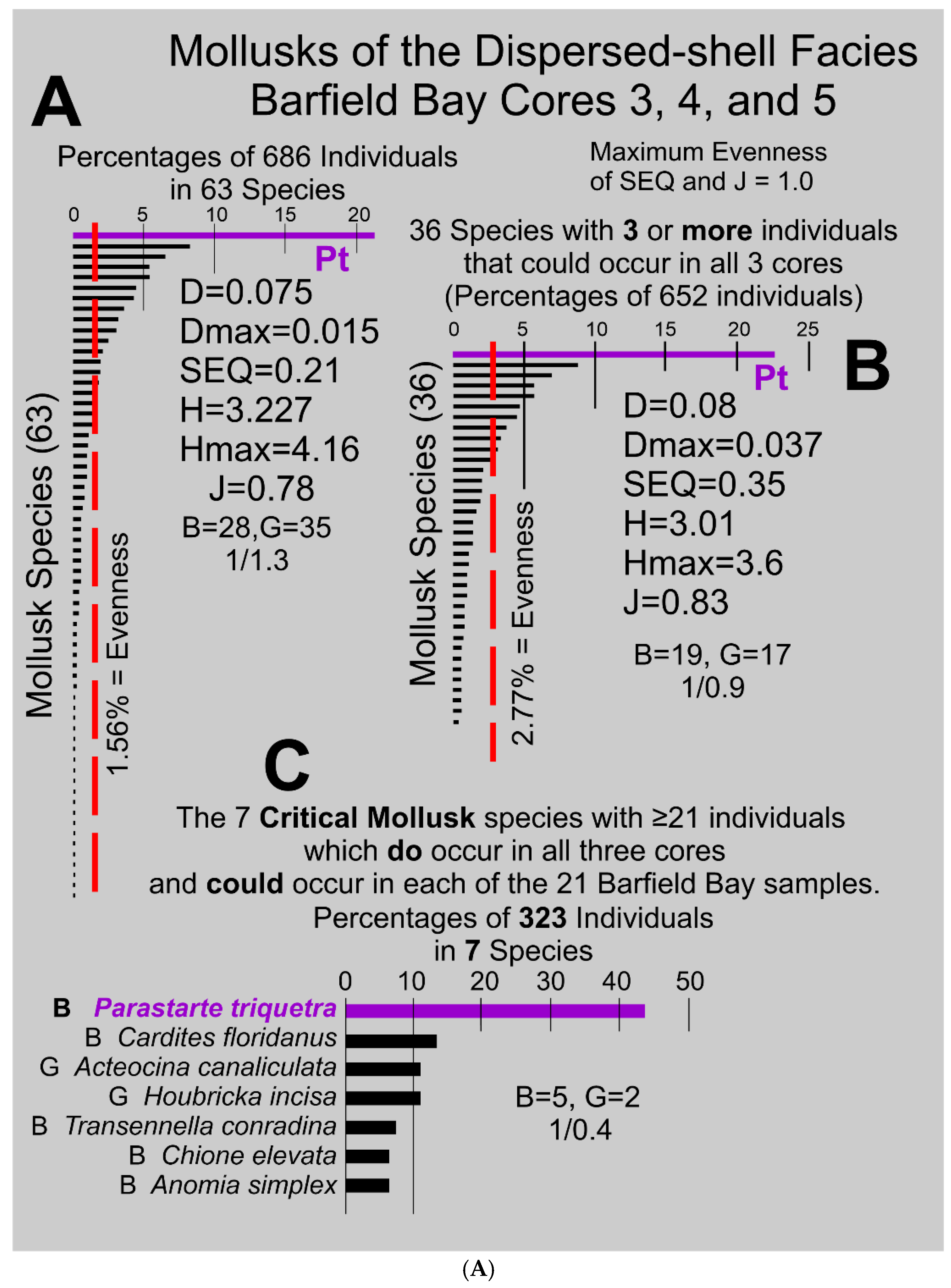

Figure 14.

A. Diagrams showing the relative abundances, diversity, and evenness of the mollusk population identified in the 21 samples (from Cores 3, 4, and 5) of the Barfield Bay bioturbated sediment-fill. The following indices have been calculated for the distributions shown in

Panels A (entire 686 individuals) and

B (species with ≥3 individuals):

D=Simpson Concentration Index (0-1 with 0 being maximum diversity),

Dmax=value that represents maximum diversity,

SEQ=Simpson Equitability Index

A (0-1 with 1 being perfect evenness).

H=Shannon Diversity Index,

Hmax=maximum diversity for Shannon Diversity Index,

J=Pielou Evenness [

29] (0-1 with 1 being maximum evenness). The vertical, red-dashed lines in Panels

A and

B indicate the percentage abundance for perfect evenness for the given distribution.

Panel C identifies the 7 Critical Mollusks which

do occur in all three Barfield Bay cores and are sufficiently abundant that they could occur in all 21 Barfield Bay mollusk samples. It is readily apparent that the abundance of the bivalve

Parastarte triquetra, shown as a purple line marked with

Pt, may be in some way anomalous.

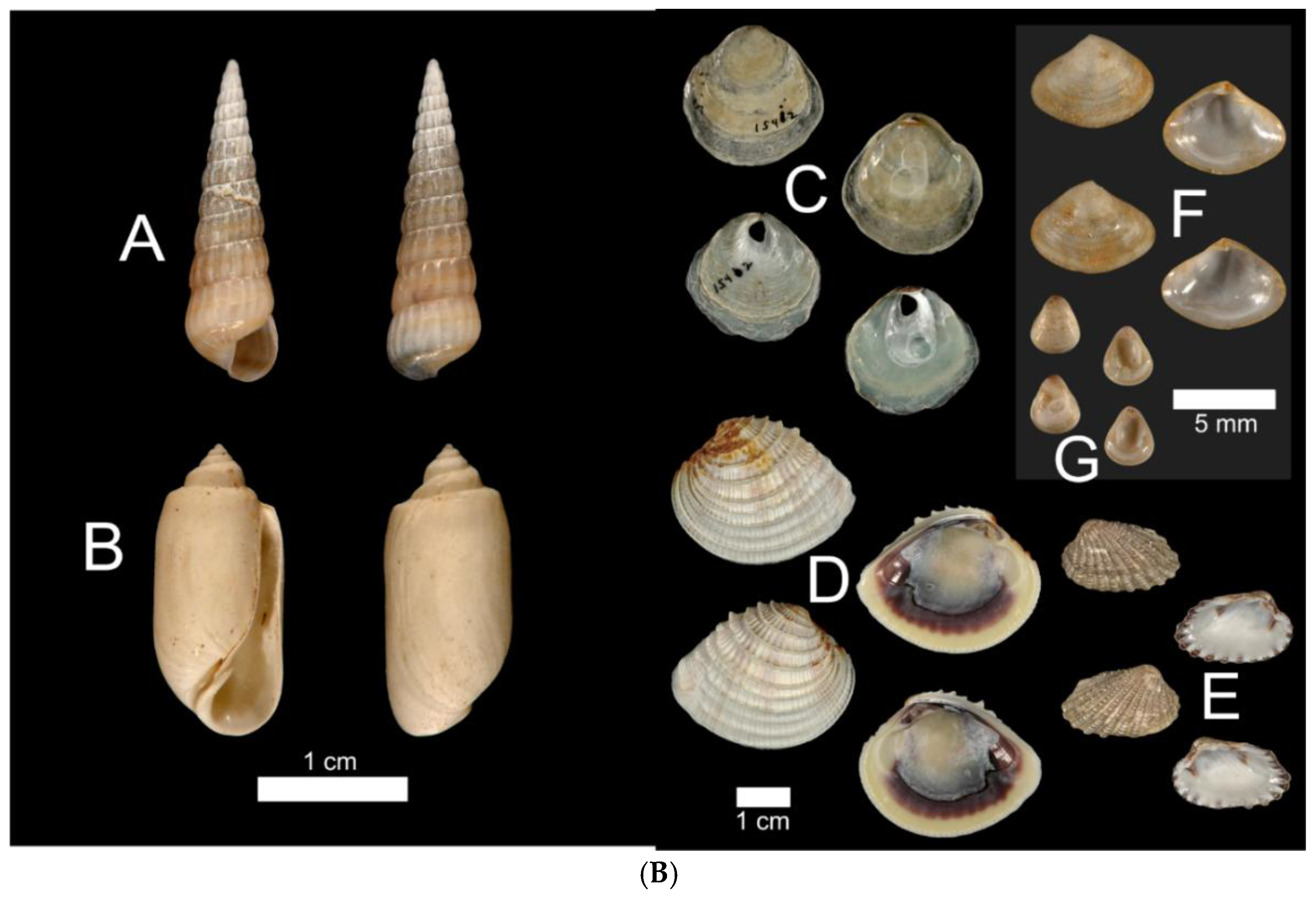

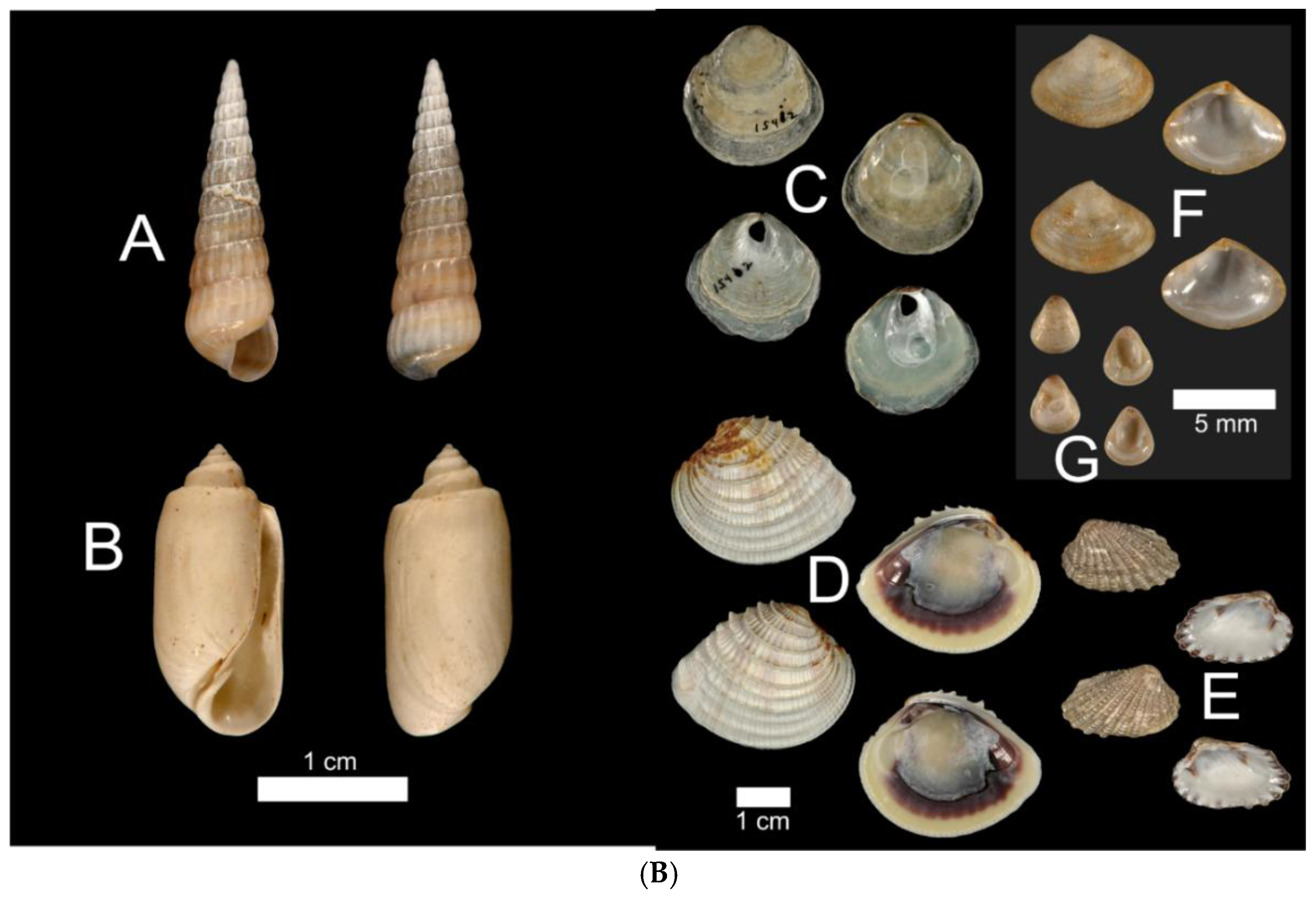

B. Images of the seven Critical Mollusks identified in the Barfield Bay mollusk population.

GASTROPODS: (A)

Houbricka incisa UF 506186, USA, Florida, Lee County; (B)

Acteocina canaliculata UF 250394, USA, Florida Palm Beach County.

BIVALVES: (C)

Anomia simplex UF 15402, USA, Florida, Lee County; (D)

Chione elevata UF 536755, USA, Florida Levy County; (E)

Cardites floridanus UF 510768, USA, Florida, Pinellas County; (F)

Transennella conradina UF 370120, USA, Florida, Miami-Dade County; (G)

Parastarte triquetra UF 528945, USA, Florida, Gulf County. Images provided by Dr. Roger Portell, Florida State Museum, Univ. of Florida.

Figure 14.

A. Diagrams showing the relative abundances, diversity, and evenness of the mollusk population identified in the 21 samples (from Cores 3, 4, and 5) of the Barfield Bay bioturbated sediment-fill. The following indices have been calculated for the distributions shown in

Panels A (entire 686 individuals) and

B (species with ≥3 individuals):

D=Simpson Concentration Index (0-1 with 0 being maximum diversity),

Dmax=value that represents maximum diversity,

SEQ=Simpson Equitability Index

A (0-1 with 1 being perfect evenness).

H=Shannon Diversity Index,

Hmax=maximum diversity for Shannon Diversity Index,

J=Pielou Evenness [

29] (0-1 with 1 being maximum evenness). The vertical, red-dashed lines in Panels

A and

B indicate the percentage abundance for perfect evenness for the given distribution.

Panel C identifies the 7 Critical Mollusks which

do occur in all three Barfield Bay cores and are sufficiently abundant that they could occur in all 21 Barfield Bay mollusk samples. It is readily apparent that the abundance of the bivalve

Parastarte triquetra, shown as a purple line marked with

Pt, may be in some way anomalous.

B. Images of the seven Critical Mollusks identified in the Barfield Bay mollusk population.

GASTROPODS: (A)

Houbricka incisa UF 506186, USA, Florida, Lee County; (B)

Acteocina canaliculata UF 250394, USA, Florida Palm Beach County.

BIVALVES: (C)

Anomia simplex UF 15402, USA, Florida, Lee County; (D)

Chione elevata UF 536755, USA, Florida Levy County; (E)

Cardites floridanus UF 510768, USA, Florida, Pinellas County; (F)

Transennella conradina UF 370120, USA, Florida, Miami-Dade County; (G)

Parastarte triquetra UF 528945, USA, Florida, Gulf County. Images provided by Dr. Roger Portell, Florida State Museum, Univ. of Florida.

Figure 15.

The stratigraphic distribution of the seven Critical Mollusks throughout the twenty-one (21) samples of the bioturbated sediment-fill in Cores 3, 4, and 5. The letters (B) and (G) indicate a bivalve and gastropod, respectively. The white circles indicate a missing Critical Mollusk in a given sample. The samples with the orange background contain six out of a possible seven Critical Mollusk species. The species in bold blue type are the twelve Salinity Mollusk species used to estimate the long-term salinity conditions in Barfield Bay. Notice the widespread stratigraphic range of the stenohaline Houbricka incisa and the widespread, but core specific, stratigraphic ranges of the stenohaline Phrontis vibex and Abra aequalis.

Figure 15.

The stratigraphic distribution of the seven Critical Mollusks throughout the twenty-one (21) samples of the bioturbated sediment-fill in Cores 3, 4, and 5. The letters (B) and (G) indicate a bivalve and gastropod, respectively. The white circles indicate a missing Critical Mollusk in a given sample. The samples with the orange background contain six out of a possible seven Critical Mollusk species. The species in bold blue type are the twelve Salinity Mollusk species used to estimate the long-term salinity conditions in Barfield Bay. Notice the widespread stratigraphic range of the stenohaline Houbricka incisa and the widespread, but core specific, stratigraphic ranges of the stenohaline Phrontis vibex and Abra aequalis.

Figure 16.

Tempestite Tp1 in Core 5. Panel

A contains a core photo of Tp1 in which the mollusk shells clearly touch each as well are arranged in a jumbled pattern. Both contacts are relatively sharp. Panel

B presents a list of sixteen (16) mollusk species identified in this unit; (

NFDSF) indicates a species not identified in the bioturbated sediment-fill. Panel C shows the distribution of the percentages of the individual 16 species. This population has a diversity D [

27] of 0.32 (Dmax=0.0625) and an evenness SEQ [

27] of 0.22 (perfect evenness=1) and can be considered to be of low diversity.

Figure 16.

Tempestite Tp1 in Core 5. Panel

A contains a core photo of Tp1 in which the mollusk shells clearly touch each as well are arranged in a jumbled pattern. Both contacts are relatively sharp. Panel

B presents a list of sixteen (16) mollusk species identified in this unit; (

NFDSF) indicates a species not identified in the bioturbated sediment-fill. Panel C shows the distribution of the percentages of the individual 16 species. This population has a diversity D [

27] of 0.32 (Dmax=0.0625) and an evenness SEQ [

27] of 0.22 (perfect evenness=1) and can be considered to be of low diversity.

Figure 17.

Panel A shows the distribution of the 144 individuals over the 38 species identified in the 14 samples from Core 1 which is located on the Caxambas Pass flood-tidal delta. The red dashed line indicates the percentage abundance for perfect evenness for this distribution. The 13 most-abundant species, listed in order of abundance, account for 76% of the 144 individuals identified in the 14 samples. The three most abundant mollusks are, in order of abundance, the bivalves Nucula proxima and Chione elevata, followed by the gastropod Acteocina canaliculata. The species in blue type in Panel A are used to estimate long-term salinity.

Figure 17.

Panel A shows the distribution of the 144 individuals over the 38 species identified in the 14 samples from Core 1 which is located on the Caxambas Pass flood-tidal delta. The red dashed line indicates the percentage abundance for perfect evenness for this distribution. The 13 most-abundant species, listed in order of abundance, account for 76% of the 144 individuals identified in the 14 samples. The three most abundant mollusks are, in order of abundance, the bivalves Nucula proxima and Chione elevata, followed by the gastropod Acteocina canaliculata. The species in blue type in Panel A are used to estimate long-term salinity.

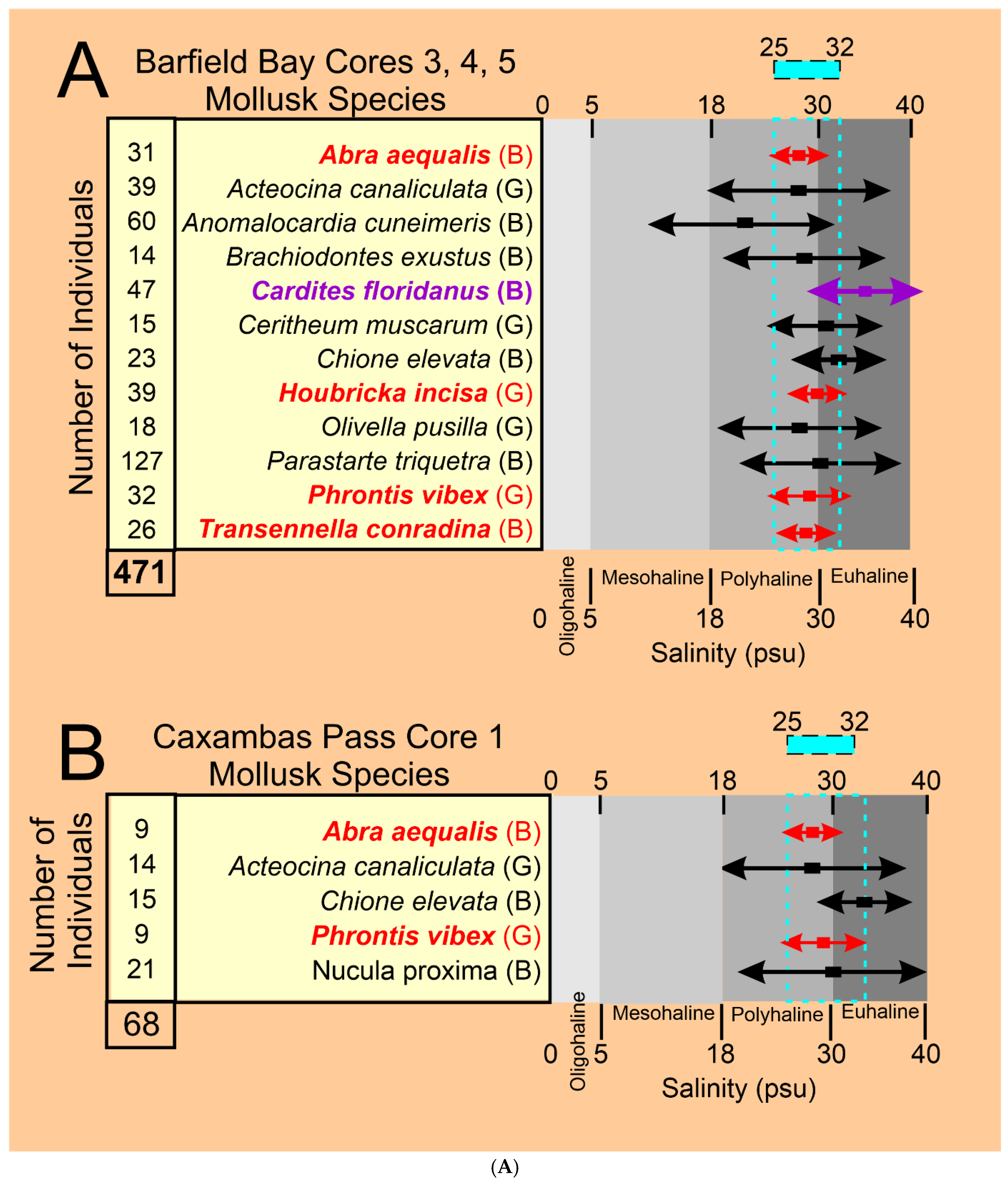

Figure 18.

A. Salinity estimates for Barfield Bay and Caxambas Pass based on mollusk populations. The salinity data [

30,

31] for each species are based on present-day conditions in southwest Florida. Stenohaline mollusks, their salinity means (rectangle) and 1 standard deviation ranges (double headed arrows), are shown in red. More euryhaline mollusks, their salinity means (rectangle) and 1 standard deviation ranges (double headed arrows), are shown in black. The essentially euhaline

Cardites floridanus is shown in purple. These twelve (12) mollusks in

Panel A account for 471 individuals out of a total of 686 (69%) identified in the bioturbated sediment-fill present in Barfield Bay.

Panel B shows the salinity ranges for the more abundant mollusks from the Caxambas Pass Core 1. These five (5) mollusks account for 68 individuals out of a total of 144 (47%) identified in the silt-rich, quartz-sand facies present in Core 1. These salinity ranges have a common overlap of 25-32 psu, shown by the turquoise-colored bar and dashed-line outline, which is basically the range of the four stenohaline species.

B. The stratigraphic distribution of the five salinity-critical mollusks in the Caxambas Pass Core 1 from Panel B in

Figure 15A. The two stenohaline mollusks

Abra aequalis and

Phrontis vibex are present in 50% and 36% of all 14 samples, respectively. Furthermore,

Abra aequalis is present throughout the thickness of Core 1, and

Phrontis vibex is concentrated near the base of Core 1.

Figure 18.

A. Salinity estimates for Barfield Bay and Caxambas Pass based on mollusk populations. The salinity data [

30,

31] for each species are based on present-day conditions in southwest Florida. Stenohaline mollusks, their salinity means (rectangle) and 1 standard deviation ranges (double headed arrows), are shown in red. More euryhaline mollusks, their salinity means (rectangle) and 1 standard deviation ranges (double headed arrows), are shown in black. The essentially euhaline

Cardites floridanus is shown in purple. These twelve (12) mollusks in

Panel A account for 471 individuals out of a total of 686 (69%) identified in the bioturbated sediment-fill present in Barfield Bay.

Panel B shows the salinity ranges for the more abundant mollusks from the Caxambas Pass Core 1. These five (5) mollusks account for 68 individuals out of a total of 144 (47%) identified in the silt-rich, quartz-sand facies present in Core 1. These salinity ranges have a common overlap of 25-32 psu, shown by the turquoise-colored bar and dashed-line outline, which is basically the range of the four stenohaline species.

B. The stratigraphic distribution of the five salinity-critical mollusks in the Caxambas Pass Core 1 from Panel B in

Figure 15A. The two stenohaline mollusks

Abra aequalis and

Phrontis vibex are present in 50% and 36% of all 14 samples, respectively. Furthermore,

Abra aequalis is present throughout the thickness of Core 1, and

Phrontis vibex is concentrated near the base of Core 1.

Figure 19.

Panel A contains the distribution data for the seven Critical Mollusks among the five (5) volume percent silt classes. The Samples column contains the number of times a particular volume percent class occurs within the 21 mollusk samples from the three Barfield Bay cores. There are 327 individual mollusks used in this analysis. Panel B shows the percentage preference of individual species for a specific volume percent silt class. The blue numbers indicate the most preferred silt classes and the green numbers the second-most preferred silt classes for the respective mollusk species.

Figure 19.

Panel A contains the distribution data for the seven Critical Mollusks among the five (5) volume percent silt classes. The Samples column contains the number of times a particular volume percent class occurs within the 21 mollusk samples from the three Barfield Bay cores. There are 327 individual mollusks used in this analysis. Panel B shows the percentage preference of individual species for a specific volume percent silt class. The blue numbers indicate the most preferred silt classes and the green numbers the second-most preferred silt classes for the respective mollusk species.

Figure 20.

The Benda and Puri [

36] distribution of the three, dominant, benthic foraminifera genera (

Ammonia spp.,

Elphidium spp., and

Miliolids) in the Gullivan Bay-Ten Thousand Islands region of southwest Florida.

1 labels Barfield Bay and

2 Marco Island. The mangrove-covered islands and barriers immediately south of Barfield Bay (shown in gray and labeled

3) probably were not in existence during, at least, the initial 3000 years of Holocene deposition in Barfield Bay. The orange mass is the Pleistocene portion of Marco Island and the pink mass is the Holocene portion. The black star in Panel C is the location of the Core 0706-19 [

34] at the mouth of Fakahatchee Bay. The contour lines indicate the generic percentages of the benthic foraminiferans.

Figure 20.

The Benda and Puri [

36] distribution of the three, dominant, benthic foraminifera genera (

Ammonia spp.,

Elphidium spp., and

Miliolids) in the Gullivan Bay-Ten Thousand Islands region of southwest Florida.

1 labels Barfield Bay and

2 Marco Island. The mangrove-covered islands and barriers immediately south of Barfield Bay (shown in gray and labeled

3) probably were not in existence during, at least, the initial 3000 years of Holocene deposition in Barfield Bay. The orange mass is the Pleistocene portion of Marco Island and the pink mass is the Holocene portion. The black star in Panel C is the location of the Core 0706-19 [

34] at the mouth of Fakahatchee Bay. The contour lines indicate the generic percentages of the benthic foraminiferans.

Figure 21.

Stratigraphic cross section through Barfield Bay showing the lithology, fossil content, and radiocarbon dates in Cores 1-5. The core depths are decompacted values with a mean sea level datum (MSL). The details of the dashed-line box (labeled

A) at the base of Core 3 are shown in

Figure 23. The plant-based and shell radiocarbon dates have been calibrated with the IntCal20 curve [

37] and the Marine 20 curves, respectively. However, no local Marine Reservoir Correction has been applied to the shell dates. All shells, except the

Crassostrea virginica, are from subtidal organisms. The tempestite shell beds (Tp) contain <10% silt by volume and the vast majority of shells are touching each other,

Figure 16. The 7800-year-old date for the Horrs Island Dune is based on an Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) age on sand collected from a depth of 1-meter below a crest location. The two flooding surfaces are identified as follows:

Fs1 where subtidal-shell-bearing quartz sand overlies granular, allogenic peat (terrestrial or lacustrine) and

Fs2 where silty quartz-sand containing plant debris overlies the early Holocene Horrs Island terrestrial aeolian dune. The Horrs Island onlap/disconformity (blue dash-dot line) indicates that Horrs Island has been incrementally submerged during the Holocene transgression, the details of which are presently unknown.

Figure 21.

Stratigraphic cross section through Barfield Bay showing the lithology, fossil content, and radiocarbon dates in Cores 1-5. The core depths are decompacted values with a mean sea level datum (MSL). The details of the dashed-line box (labeled

A) at the base of Core 3 are shown in

Figure 23. The plant-based and shell radiocarbon dates have been calibrated with the IntCal20 curve [

37] and the Marine 20 curves, respectively. However, no local Marine Reservoir Correction has been applied to the shell dates. All shells, except the

Crassostrea virginica, are from subtidal organisms. The tempestite shell beds (Tp) contain <10% silt by volume and the vast majority of shells are touching each other,

Figure 16. The 7800-year-old date for the Horrs Island Dune is based on an Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) age on sand collected from a depth of 1-meter below a crest location. The two flooding surfaces are identified as follows:

Fs1 where subtidal-shell-bearing quartz sand overlies granular, allogenic peat (terrestrial or lacustrine) and

Fs2 where silty quartz-sand containing plant debris overlies the early Holocene Horrs Island terrestrial aeolian dune. The Horrs Island onlap/disconformity (blue dash-dot line) indicates that Horrs Island has been incrementally submerged during the Holocene transgression, the details of which are presently unknown.

Figure 22.

Aerial photograph of Barfield Bay, US Geological Survey 1995. A is a flood tidal-delta at the north end of the main tidal channel from Caxambas Pass. Bh is the Blue Hill Creek flood tidal-delta. Dashed lines are tidal channels the thicknesses of which indicate relative importance. The white letters Tg indicate the presence of subtidal Turtle Grass (Thalassia testudinum).

Figure 22.

Aerial photograph of Barfield Bay, US Geological Survey 1995. A is a flood tidal-delta at the north end of the main tidal channel from Caxambas Pass. Bh is the Blue Hill Creek flood tidal-delta. Dashed lines are tidal channels the thicknesses of which indicate relative importance. The white letters Tg indicate the presence of subtidal Turtle Grass (Thalassia testudinum).

Figure 23.

Annotated photograph of the basal 23-cm of Core 3 showing the various stratigraphic units. Basal Unit

A contains both rare nearshore-marine mollusks (

Anomalocardia?) and a sparse assemblage of calcareous, benthic foraminifera. There is a disconformity between Units A and B. The C-14 date of

6900±50 yrs BP on the allogenic peat clasts of Unit B may be only a maximum estimate. The

6180±85 yrs BP date on an

Anomalocardia cuneimeris shell from the overlying Unit C is only a

maximum estimate for the age of deposition. The contact between Units B and C is marine flooding surface Fs1 (

Figure 21), the oldest such surface identified in the Barfield Bay sediment-fill.

Figure 23.

Annotated photograph of the basal 23-cm of Core 3 showing the various stratigraphic units. Basal Unit

A contains both rare nearshore-marine mollusks (

Anomalocardia?) and a sparse assemblage of calcareous, benthic foraminifera. There is a disconformity between Units A and B. The C-14 date of

6900±50 yrs BP on the allogenic peat clasts of Unit B may be only a maximum estimate. The

6180±85 yrs BP date on an

Anomalocardia cuneimeris shell from the overlying Unit C is only a

maximum estimate for the age of deposition. The contact between Units B and C is marine flooding surface Fs1 (

Figure 21), the oldest such surface identified in the Barfield Bay sediment-fill.

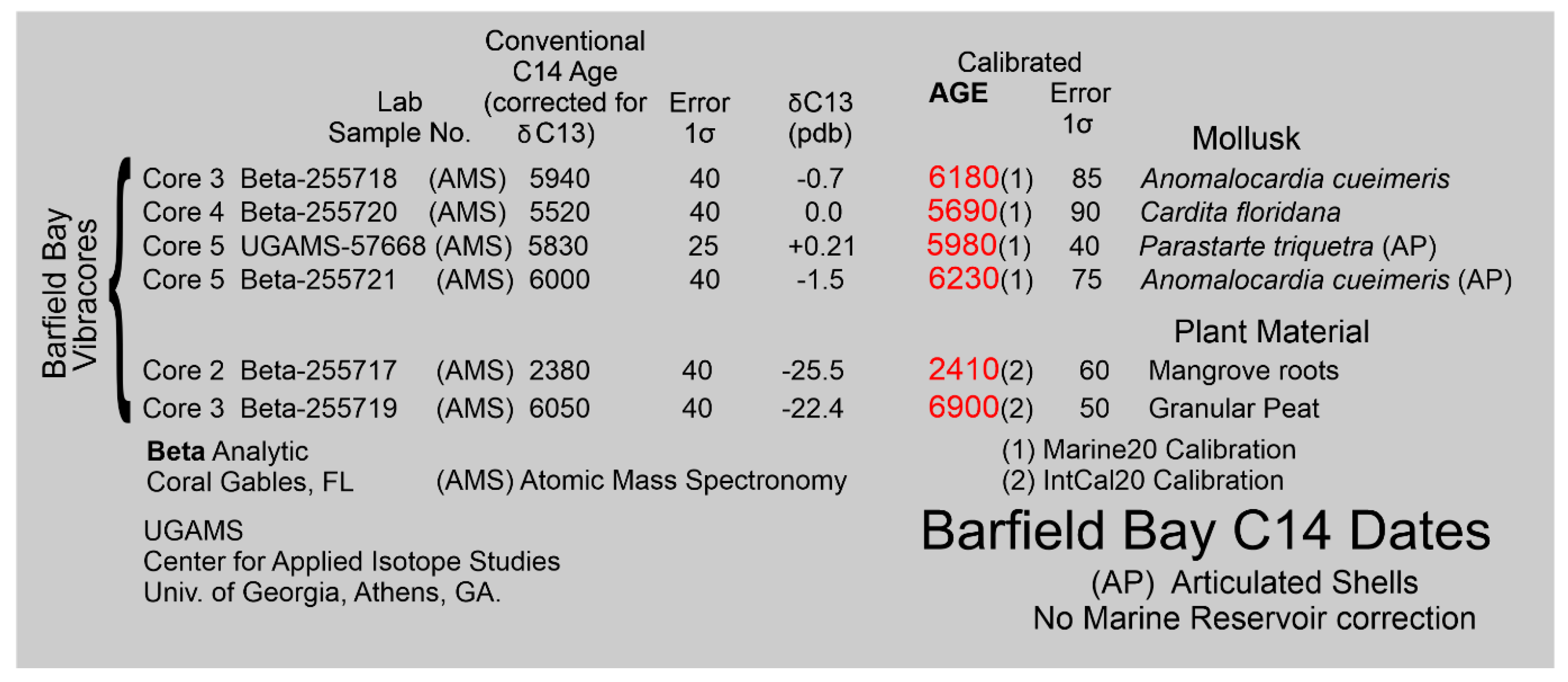

Figure 24.

Radiocarbon dates on mollusk shells and vegetative material collected in the Barfield Bay vibracores. The calibration curves Marine20 and IntCal20 are from Heaton [

38]. These samples are located in

Figure 20. The two articulated mollusk samples are from tempestite Tp1.

Figure 24.

Radiocarbon dates on mollusk shells and vegetative material collected in the Barfield Bay vibracores. The calibration curves Marine20 and IntCal20 are from Heaton [

38]. These samples are located in

Figure 20. The two articulated mollusk samples are from tempestite Tp1.

Figure 25.

A diagram showing the relative sea level (RSL) curves based on mangrove-peat data from Snipe and Swan Keys in south Florida [