Submitted:

18 August 2025

Posted:

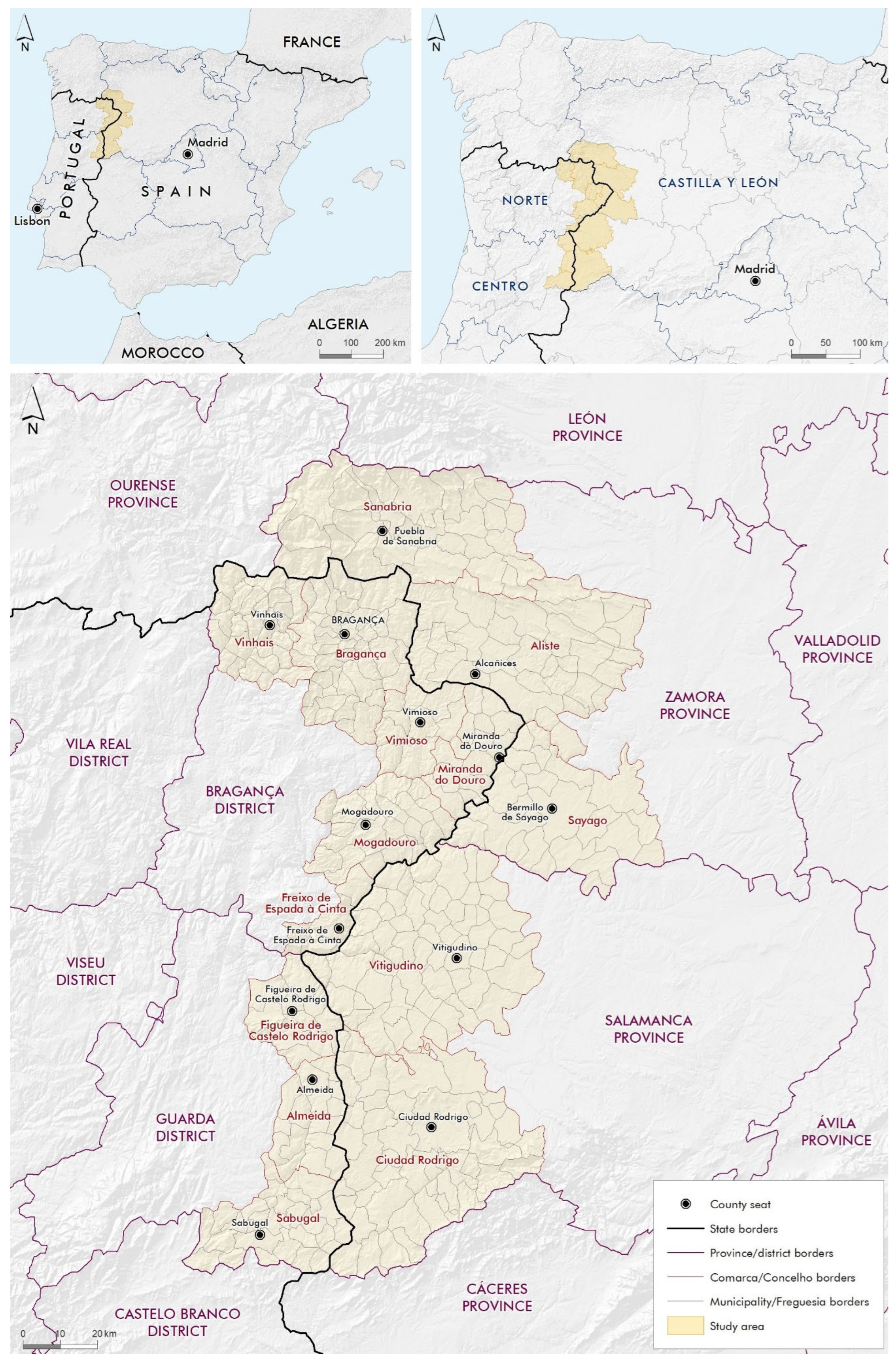

19 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

‘Borders and mobilities are not antithetical. A globalizing world is a world of networks, flows and mobility; it is also a world of borders.’

2. Literature Review

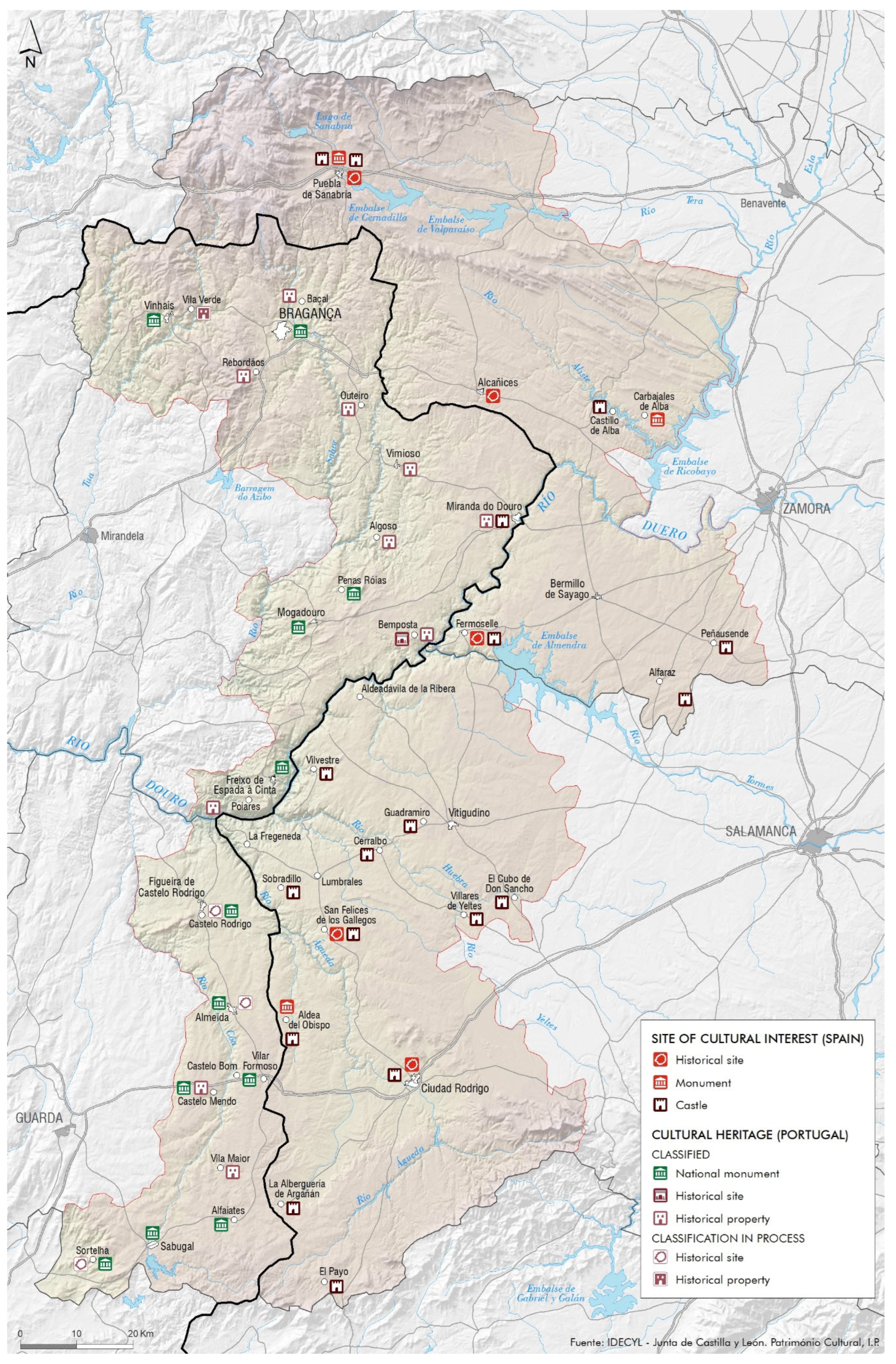

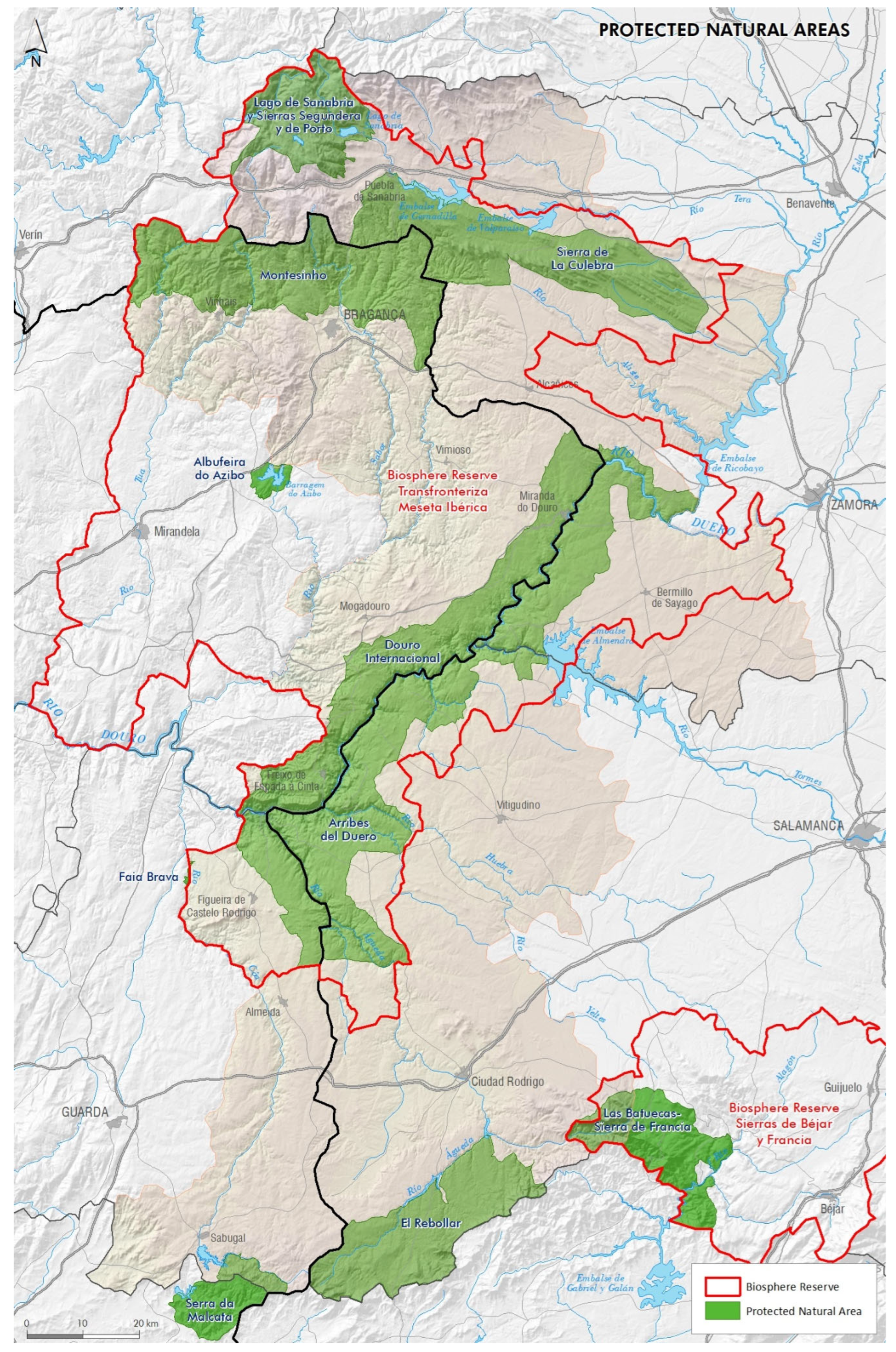

2.1. Borderlands as a Tourists’ Destinations

- -

- Accessibility: the entire transportation system to reach and move around the destination (to which high-speed internet connections and mobile telephony may be added),

- -

- Amenities: all services facilitating a convenient stay,

- -

- Available packages: availability of service bundles by intermediaries to direct tourists’ attention to the unique features of a destination,

- -

- Activities: all available activities at the destination and what consumers can do during their visit, and

- -

- Ancillary Services: daily used services, such as banks, telecommunication, postal service, and hospital, which are not primarily aimed for tourists (Buhalis, 2000, p. 98).

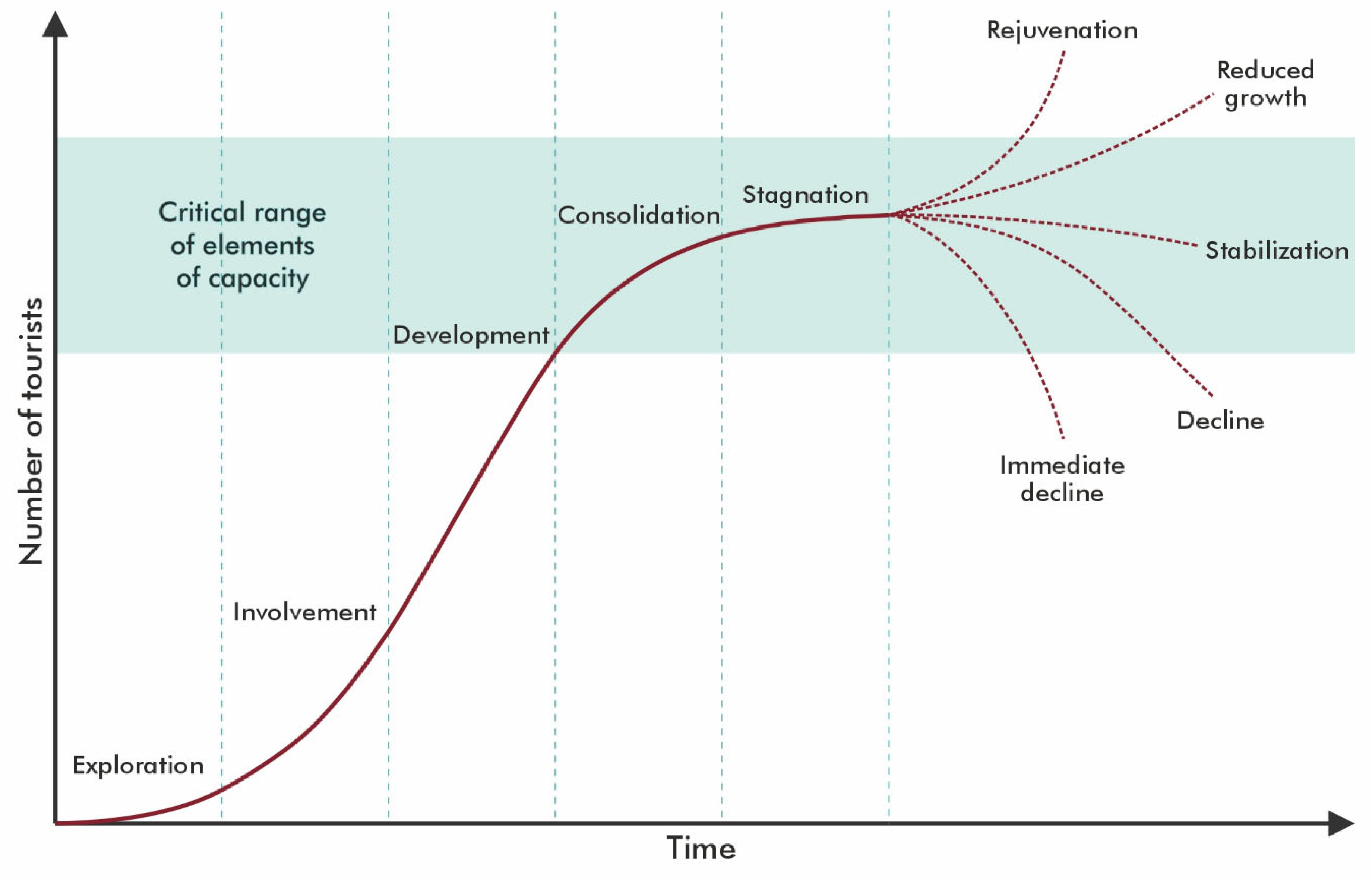

2.2. Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle

- Exploration: Small numbers of tourists use local facilities having contact with local people without changing the local social and natural environment.

- Involvement: Some local residents begin to provide facilities. Some pressure on public institutions to improve tourism facilities can be expected. Interaction with local people is high. Examples of this stage van be observed in less accessible areas of western Europe (Butler 1980, 8).

- Development: The number of tourists increases rapidly. The area is substantially marketed in tourist-generating areas. Facilities and attractions are adapted. External control of facilities and attractions and business increases to the detriment of local control.

- Consolidation: The rate of increase in the number of tourists declines. The area now depends on tourism dominated by external actors. Some discontent among local people can emerge.

- Stagnation: Tourist numbers stop increasing because the local environment loses attractivity. Organised mass tourism dominates the area.

- Decline or Rejuvenation: Decline implies a decreasing number of tourists, loosing attractivity due to competition with new attractive destinations. Rejuvenation may occur when new attractions are added and/or existing but unexploited heritage is now (re)utilised for tourism.

2.3. Considerations of Typology Building

3. Materials and Methods

‘…are today as they are and, why not, as well as giving some clues about their futures as living communities’ (Sanz-Ibáñez & Clave 2014, 572).

4. Results: Typology Tourist Destinations

Tourism Destination Typology

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Informed Consent Statement Not applicable.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aledo, A. & Mazón, T. (2004). Impact of residential tourism and the destination life cycle theory, In; Pineda, Brebbia, C.A, & Mugica, M. (eds.) Sustainable Tourism, 25-36, WIT Press.

- Alves Moreira, M. C. (2016).

- Boura, I. (2004). Património e mobilização das comunidades locais: das Aldeias Históricas aos contratos de aldeia, Cadernos de Geografia, 21.23.

- Breakey, N.M. (2005).

- Buhalis, D. Marketing the competitive destination of the future. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.W. The Concept of a Tourist Area Cycle of Evolution: Implications for Management of Resources. In The Tourism Area Life Cycle; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2006; Volume 1, pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R (2004). The tourism area life cycle, in the twenty-first century, in: Lew, A, Hall, M. & Williams, A. M, (eds,) A companion to tourism, 159-169, Blackwell Publishing.

- Cabero, V. (2004). (2004). Bordes y márgenes del territorio en Castilla y León: integración y cooperación. In E. Clemente, Mª. I. Martín & L. A. Hortelano (Eds), Territorio y planificación, una aproximación a Castilla y León, (pp.79-95). Salamanca: Caja Duero.

- Camară, G. Comment on “A new European regional tourism typology”. Ann. Tour. Res. Empir. Insights 2022, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campesino Fernández A., J. (2016). Paisajes del agua y turismo fluvial en la raya ibérica, In: Vera, J. F., Olcina, J., Hernández, M. (eds.), Paisaje, cultura territorial y vivencia de la Geografía. 47-72, Libro homenaje al profesor Alfredo Morales Gil. P: San Vicente del Raspeig.

- CEAMA (2021). Actas do XV Seminário Internacional do Centro de Estudos de Arquitectura Militar de Almeida, Google Académico.

- Chylińska, D. Escape? But where? About ‘escape tourism’. Tour. Stud. 2022, 22, 262–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccossis, H.; Constantoglou, M.E. (2006). The Use of Typologies in Tourism Planning: Problems and Conflicts, in Regional analysis and policy: The Greek experience, In: Coccossis, H. & Psycharis, Y. (eds.

- Ettema, W. A. (1980). 18.

- Fiorello, A.; Bo, D. Community-Based Ecotourism to Meet the New Tourist's Expectations: An Exploratory Study. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2012, 21, 758–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelbman, A.; Timothy, D.J. Border complexity, tourism and international exclaves. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 110–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregório, M. J. & Sarmento, J. (2022). A ruína como actante: a teoria ator-rede das aldeias históricas em Castelo Rodrigo, Portugal, In Reis, P. (ed.) Turismo e Desenvolvimento dos Territórios do Interior. -55.

- Chorley, R.; Haggett, P. Integrated Models in Geography (Routledge Revivals); Taylor & Francis: London, United Kingdom, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M. A typology of governance and its implications for tourism policy analysis. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 437–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haywood, K. Can the tourist-area life cycle be made operational? Tour. Manag. 1986, 7, 154–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, G. K. S. & McKercher, B. (2015). A review of life cycle models by Plog and Butler from a marketing perspective, in Kozak, M, & Kozak, N.

- Hortelano Mínguez, L. A. (2015). 36. [CrossRef]

- Hortelano Mínguez, L. A. & Mansvelt Beck, J. (2017). 29.

- Hortelano Mínguez, L. A. & Martín Pescador, C. A. (2025). Atlas de la Raya hispano-lusa/ Atlas da Raia hispano-lusa, Junta de Castilla y León, Valladolid.

- Jacobsen, J.K.S. Roaming Romantics: Solitude-seeking and Self-centredness in Scenic Sightseeing. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2004, 4, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, C.S. Shoring the foundations of the destination life cycle model, part 1: Ontological and epistemological considerations. Tour. Geogr. 2001, 3, 2–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühn, M. Peripheralization: Theoretical Concepts Explaining Socio-Spatial Inequalities. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2014, 23, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagiewski, R. (2006).The Application of the Talc model: a literature survey. Aspects of Tourism, in: Butler, R. (ed.). The Tourism Area Life Cycle Vol.1 Applications and Modifications. Cromwell Press, 27-50.

- Lane, B.; Kastenholz, E. Rural tourism: the evolution of practice and research approaches – towards a new generation concept? J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 1133–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCannell, D. Staged Authenticity: Arrangements of Social Space in Tourist Settings. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 79, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, J. C. (1969). 48.

- Mehmetoglu, M. Typologising nature-based tourists by activity—Theoretical and practical implications. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 651–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, D. (2016), On the location of tourism: an outlook from Europe’s northern periphery, In: Mayer, M. & Job, H. (eds.) Naturtourismus- Chancen und Herausforderungen, 113-124, MetaGis-Systems, Mannheim.

- Ouyang, R. , Li, X. & Xing, J. (2023). A: Tourism geography; 2. [CrossRef]

- Paasi, A. Bounded spaces in a ‘borderless world’: border studies, power and the anatomy of territory. J. Power 2009, 2, 213–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paasi, A. Examining the persistence of bounded spaces: remarks on regions, territories, and the practices of bordering. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B, Hum. Geogr. 2022, 104, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintado, A. & Barrenechea, E. (1972). La raya de Portugal. La frontera del subdesarrollo. Madrid: Edicusa, Cuadernos para el Diálogo.

- Castro, M.P.; Prieto, F.C.; Aparicio, D.G.; Zamora, A.N.; Tárraga, A.B.L. Turismo y patrimonio como motores de desarrollo rural: el caso de las bodegas históricas de Fermoselle (Zamora). Cuad. Geogr. 2023, 62, 118–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokkola, E.-K.; Lois, M. Scalar politics of border heritage: an examination of the EU’s northern and southern border areas. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2016, 16, 14–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, P. S. (2017). P. 417 Turismo planeamento e desenvolvimento regional. Estratégias de intervenção para a rede das Aldeias Históricas de Portugal, Tese de Doutoramento, Universidade de Coimbra, Google Académico.

- de la Cruz, E.R.R.; Ruiz, E.C.; Aramendia, G.Z. Una década de turismo sin fronteras. El caso de la Región Duero/Douro, el turismo fluvial y la diversidad turística. Cuad. de Turismo. [CrossRef]

- Rumford, C. Theorizing Borders. Eur. J. Soc. Theory 2006, 9, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Ibáñez, C.; Clavé, S.A. The evolution of destinations: towards an evolutionary and relational economic geography approach. Tour. Geogr. 2014, 16, 563–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarantakou, E. Contemporary Challenges in Destination Planning: A Geographical Typology Approach. Geographies 2023, 3, 687–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L. (2009). S: Heritage building in the ’historical villages of Portugal’; 2.

- Silva, L. Built heritage-making and socioeconomic renewal in declining rural areas: evidence from Portugal. Etnografica 2012, 487–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackie, S.L.; Koduri, G.; Hill, C.L.; Wakefield, R.J.; Hutchings, R.; Loy, C.; Dasgupta, B.; Wyatt, J.C. Accuracy of musculoskeletal imaging for the diagnosis of polymyalgia rheumatica: Systematic review. RMD Open 2015, 1, e000100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S. Time, tourism area ‘life-cycle,’ evolution and heritage. J. Heritage Tour. 2020, 16, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofield, T.H. Border Tourism and Border Communities: An Overview. Tour. Geogr. 2006, 8, 102–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timothy, D.J. Political boundaries and tourism: borders as tourist attractions. Tour. Manag. 1995, 16, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, C. Towards a Typology of Community Participation in the Tourism Development Process. Anatolia 1999, 10, 113–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, C. Expected nature of community participation in tourism development. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S. & Lew, A. A. (2014).

| P Periphery PPP Peripheralization |

Inhibiting attraction | Favouring attraction |

|---|---|---|

| P Remoteness | Far from population centres/Limited accessibility | None |

| P Rurality | Reduced activity options | Rest/Authentic nature and culture/Tourist-friendly environment |

| P Border | Low cross-border connectivity/Cultural differences hamper personal communication | Tangible heritage of militarisation/Availability consumer goods and services across the border/Smuggling trails |

| P Structural deficits | Lack of amenities and ancillary services | None |

| PPP Lack of innovation | Lowly qualified workforce | Authentic nature and culture |

| PPP Out-migration | Disappearance of potential of tourism entrepreneurs Degradation cultural landscapes due to abandoned agriculture |

Reappearance wildlife (wolf/bird watching) |

| Type | Volume | Institutional Involvement |

AAAAA | Heritage Recognition | Defensive Heritage | Location in Natural Reserve | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mature | High/Stable | Start: before EU policies, Multilayered | High/Moderate in Puebla and Almeida | Yes | Yes | Puebla de Sanabria | Bragança Ciudad Rodrigo, Puebla de Sanabria, Almeida |

| Developing | Significant growth | Province | Low | Yes | No | Arribes del Duero | La Fregeneda |

| Hyper-development |

Booming | Since mid-1990s, State; now market-driven | Low | Yes | Yes | No | Sortelha, Castelo Rodrigo |

| Rejuvenating | Cross-border shopping replaced by other attractions | Since century XXI, Multilayered | Moderate | Yes | Yes | Douro Internacional, Arribes del Duero |

Miranda do Douro, Fermoselle, Vimioso |

| Stagnation/ Decline |

Decrease cross-border shopping | Since century XXI, Multilayered | Moderate | No | No | No | Vilar Formoso |

| Specialised niche tourism | Moderate or Low/Stable or Growing | Diverse | Low | Diverse | Diverse | Diverse | Small-scale localities |

| Failed policy-driven | Low | Since mid-1990s, Multi-Layered | Low | Yes | Yes | Yes | San Felices de los Gallegos, Aldea del Obispo |

| Sleeping or Exploration | Low | Low | Low | Diverse | Diverse | Diverse | Most sites |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).