Submitted:

19 August 2025

Posted:

19 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Proposed Method

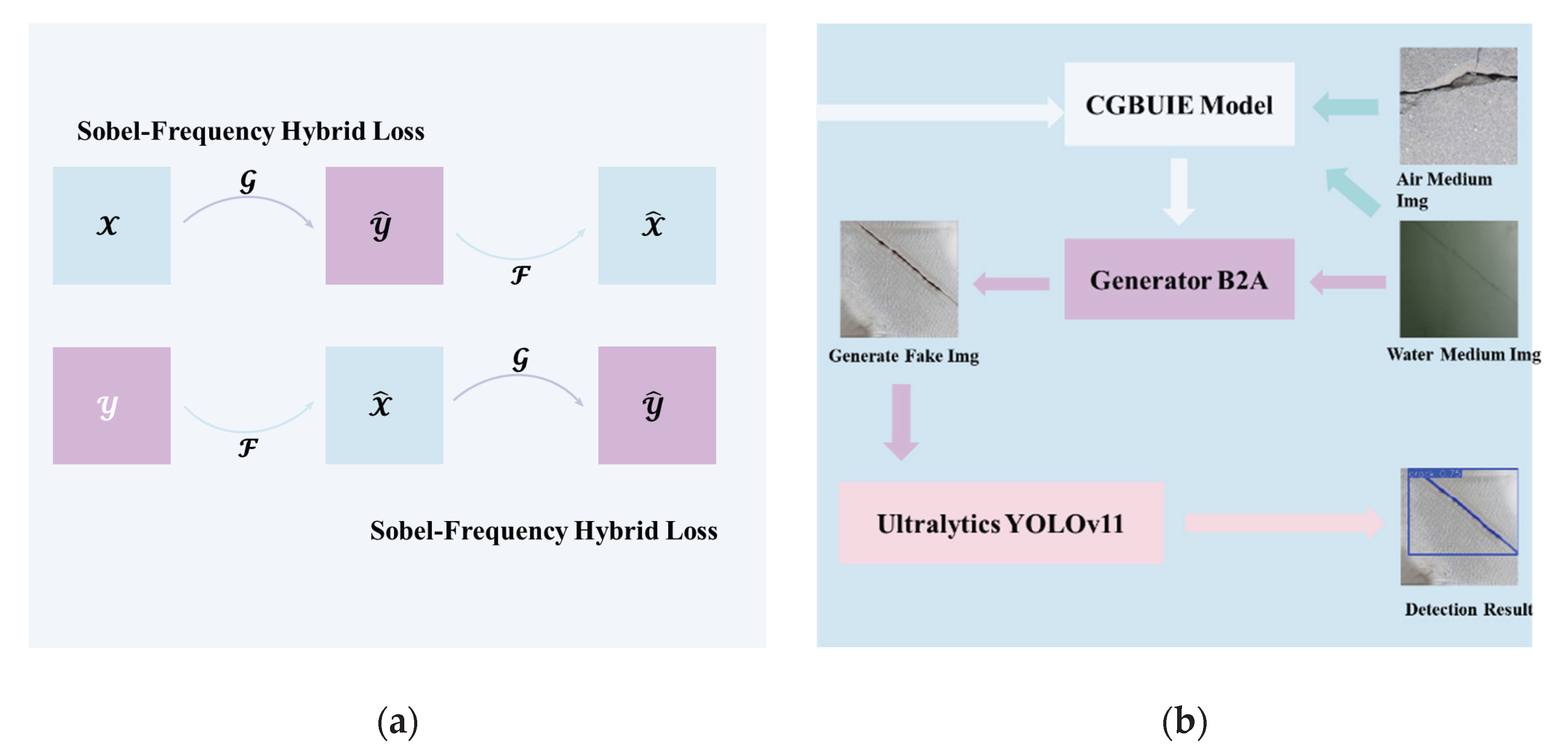

2.1. CycleGAN Based Underwater Image Enhancement Model

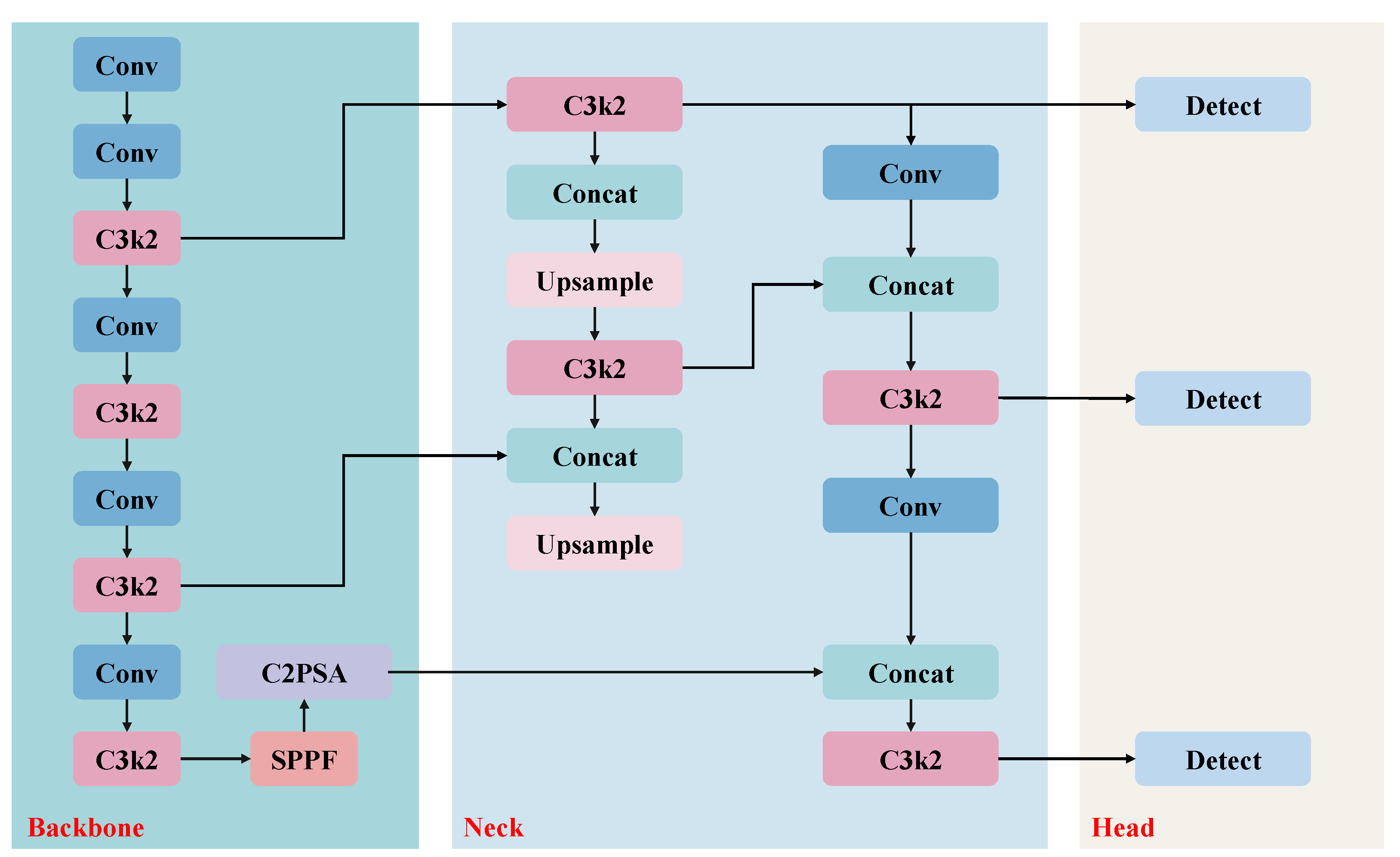

2.2. YOLOv11 Model

3. Experimental Analysis

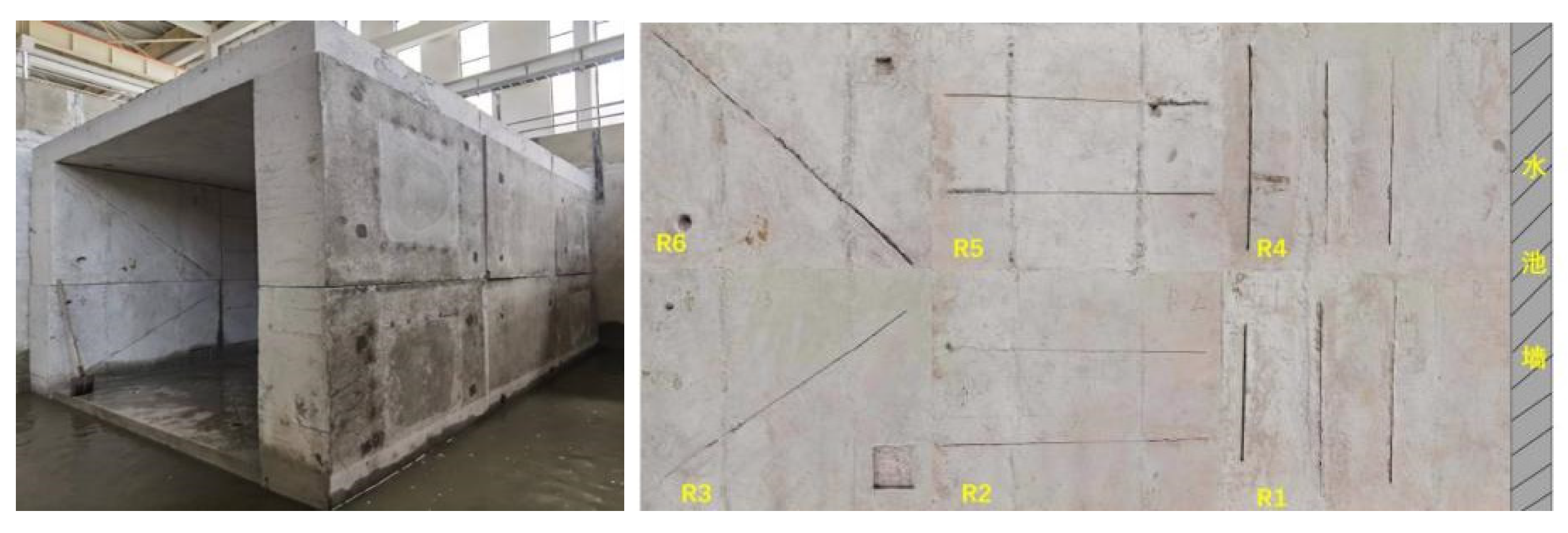

3.1. Data Collection and Experimental Setup

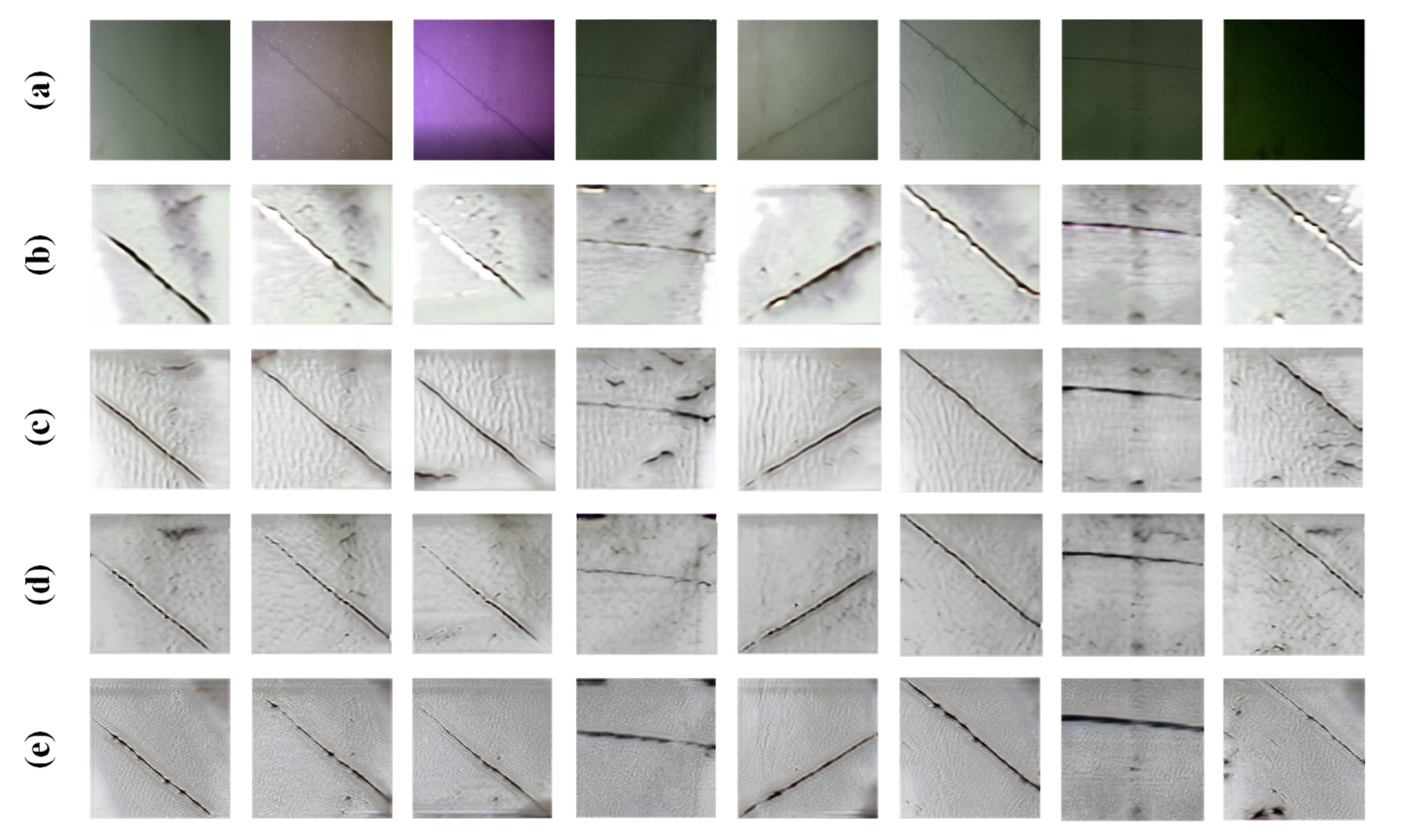

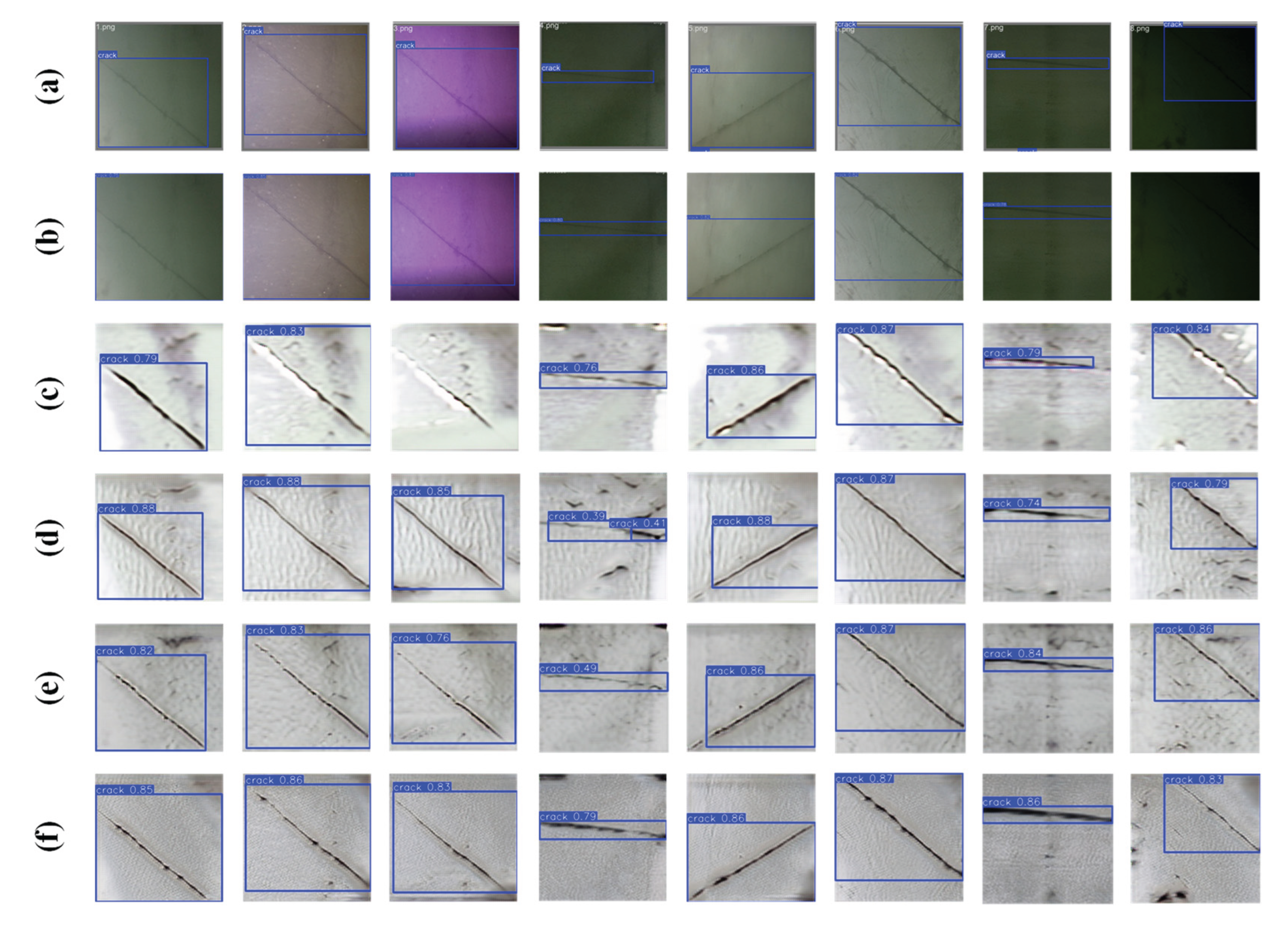

3.2. Experimental Results and Analysis

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gong Xiaonan et al Dam Danger Assessment and Risk Reinforcement Technology [M], China Construction Industry Press 2021 (in Chinese).

- XIANG Yan, WANG Yakun, CHEN Zhe, DAI Bo, CHEN Siyu, SHEN Guangze. Underwater defect detection and diagnosis assessment for high dams: current status and challenges[J]. Advances in Water Science.

- Morlando G, Panei M, Porcino D, Pasquali M, Saponara S. Underwater Surveys of Hydraulic Structures: A Review Focused on the Use of Underwater Locomotion Systems[J]. Frontiers in Robotics and AI, 2021/2023.

- Akkaynak D, Treibitz T. Sea-thru: A Method for Removing Water from Underwater Images[C]//Proc. CVPR. 1691, 1682–1691.

- Pizer S M, Amburn E P, Austin J D, et al. Adaptive histogram equalization and its variations[J]. Computer Vision, Graphics, and Image Processing 1987, 39, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CHEN Lifeng, LIANG Xiaogang, PENG Qianqian, et al. Adaptive homomorphic filtering algorithm for low illumination image enhancement[J]. Computer Science and Application 2023, 13, 450. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Li, W. Zhang, Y. Zhang, Z. Chen and H. Gao, "Adaptively Dictionary Construction for Hyperspectral Target Detection. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 2023, 20, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Xiang Y, Dai B, et al. ``Dam early warning model based on structural anomaly identification and dynamic effect variables selection,'' in Structures, Elsevier, vol~74, PP.108507, 2025.

- Wang, Y. , Fan, H., Liu, S., & Tang, Y. (2024). Underwater Image Enhancement Based on Multi-scale Attention and Contrastive Learning. Laser & Optoelectronics Progress.

- Du Feiyu, Wang Haiyan, Yao Haiyang, et al. Domain-Adaptive Underwater Image Enhancement Algorithm [J]. Computers and Modernization.

- Li J, Skinner K, Eustice R M, Johnson-Roberson M. WaterGAN: Unsupervised Generative Network to Enable Real-time Color Correction of Monocular Underwater Images[EB/OL]. arXiv:1702.07392, 2017.

- OceanVision Lab. EUVP: A Large-Scale Paired and Unpaired Underwater Image Enhancement Dataset[EB/OL]. 2019.

- Hambon, J. Electronical imaging of structural concrete: Investigation by Bayesian stationary wavelet field[J]. Electronic Imaging 2009, 9, 764–773. [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Wang Y, Zhou D. The Image Recognition, Automatic Measurement and Seam Tracking Technology in Arc Welding Process[C]//2010 8th World Congress on Intelligent Control and Automation. 2010, 2327–2332.

- Shi Z, Tao G, Cao Z, et al. CrackYOLO: A More Compatible YOLOv8 Model for Crack Detection[J]. PAA(Pattern Analysis and Applications), 2024.

- Mao, Y., et al. (2020). Crack Detection with Multi-task Enhanced Faster R-CNN Model. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (pp. 1234-1238). IEEE.

- Huang Y, Huang H, Zhang J, et al. Intelligent recognition of crack targets based on improved YOLOv5[J]. Tsinghua Science and Technology, 2023.

- He K, Wang K, Liu Y, et al. URPC2019: Underwater Robot Picking Contest and Dataset[EB/OL]. LNCS (Springer).

- Zheng Z, Wang P, Liu W, et al. Distance-IoU Loss: Faster and Better Learning for Bounding Box Regression[C]//Proc. AAAI. 2993.

- Hou X, Sheng H, You L, et al. An Improved YOLOv8 for Underwater Object Detection[J]. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 2024, 12, 123. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J-Y, Park T, Isola P, Efros A A. Unpaired Image-to-Image Translation using Cycle-Consistent Adversarial Networks[C]//Proc. ICCV. 2251.

- Zhang Y, Wu K, Fang K. Comprehensive Performance Evaluation of YOLOv11: Advancements, Benchmarks, and Real-World Applications[EB/OL]. arXiv:2411.18871, 2024.

- Chen H, Zhang H, Yin H, et al. Multi-scale reconstruction of edges in images using a morphological Sobel algorithm[J]. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 14202. [Google Scholar]

- Cooley J W, Tukey J W. An algorithm for the machine calculation of complex Fourier series[J]. Mathematics of Computation 1965, 19, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez R C, Woods R E. Digital Image Processing (3rd ed.)[M]. Pearson, 2008.

- Jiang L, Dai B, Wu W, Loy C C. Focal Frequency Loss for Image Reconstruction and Synthesis[C]//NeurIPS. 2021.

- Kim; et al. Wavelet-Domain High-Frequency Loss for Perceptual Quality[C]//WACV. 2023.

- El-askary A, et al. LM-CycleGAN: Improving Underwater Image Quality Through Loss Functions[EB/OL]. Scientific Foundation, 2024.

- Enhancement of underwater dam crack images using a multi-feature CycleGAN[J]. Automation in Construction, 2024.

- Powers D M, W. Evaluation: From Precision, Recall and F-Measure to ROC, Informedness, Markedness and Correlation[J]. Journal of Machine Learning Technologies 2011, 2, 37–63. [Google Scholar]

- Everingham M, Van Gool L, Williams C K I, Winn J, Zisserman A. The PASCAL Visual Object Classes (VOC) Challenge[J]. IJCV 2010, 88, 303–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Future Machine Learning. Differences Between Precision, Recall, and F1 Score[EB/OL]. 2025.

- Kintu J P, Kaini S, Shakya S, et al. Evaluation of a cough recognition model in real-world noisy environment[J]. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 2025, 25, 381. [Google Scholar]

| CycleGAN | SobelLoss | HFLoss | Detection Evaluation Indicators | |||||

| Precision | Recall | F1-Scorw | mAP50 | mAP50-95 | ||||

| 0.93 | 0.875 | 0.902 | 0.876 | 0.565 | ||||

| √ | 0.994 | 1 | 0.930 | 0.982 | 0.624 | |||

| √ | √ | 0.869 | 1 | 0.996 | 0.991 | 0.548 | ||

| √ | √ | 0.993 | 1 | 0.997 | 0.993 | 0.72 | ||

| √ | √ | √ | 1 | 1 | 0.999 | 0.995 | 0.732 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).