Submitted:

18 August 2025

Posted:

20 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

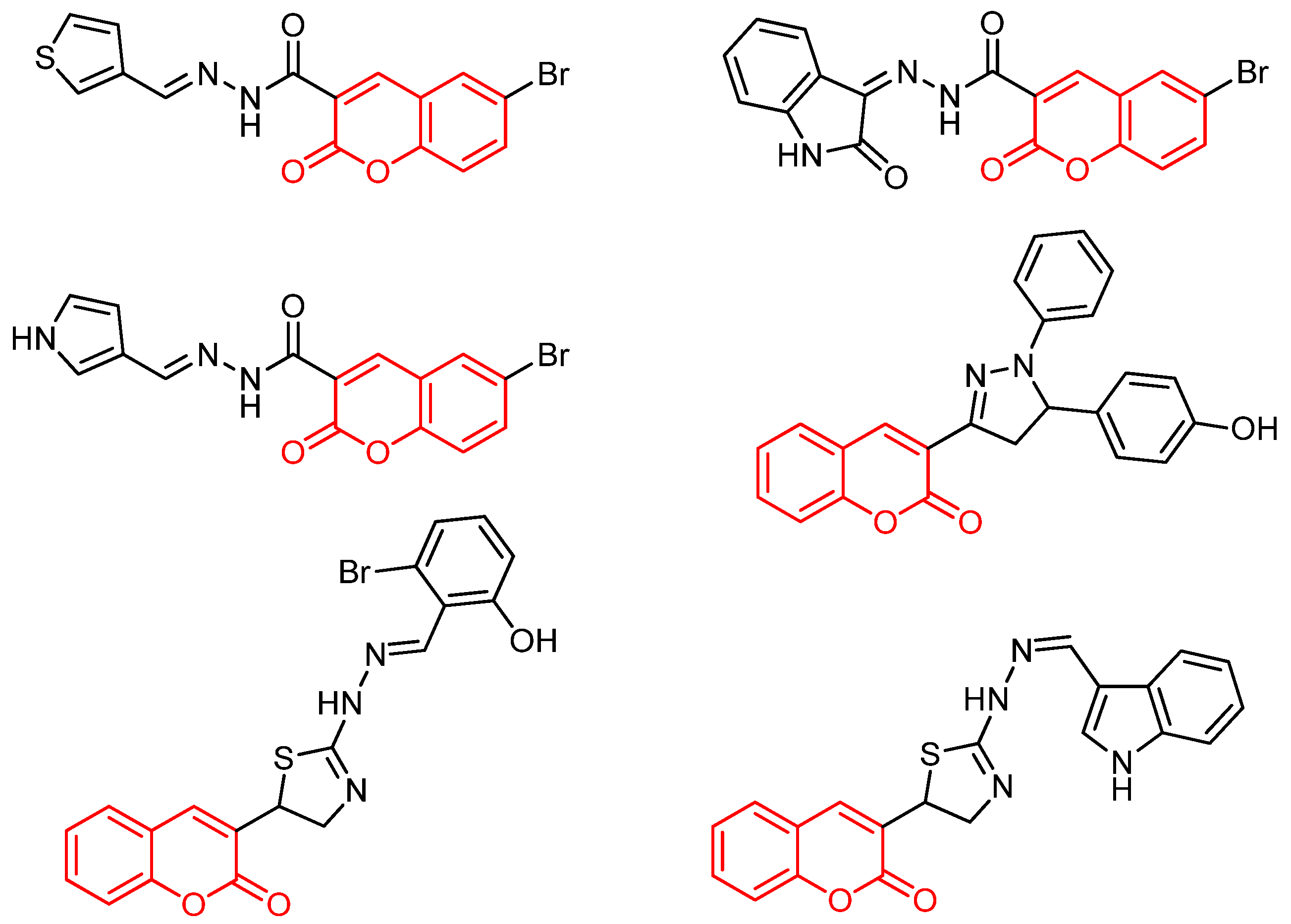

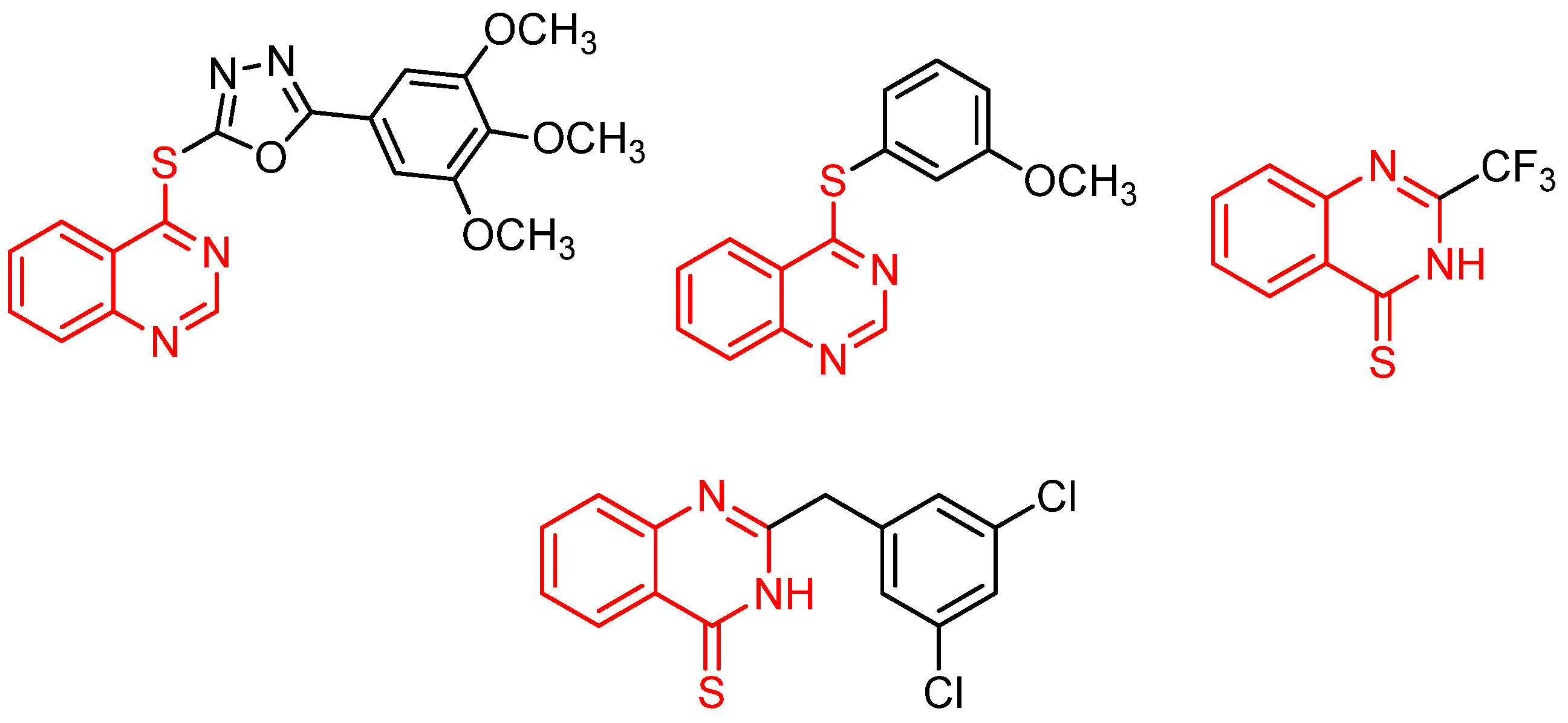

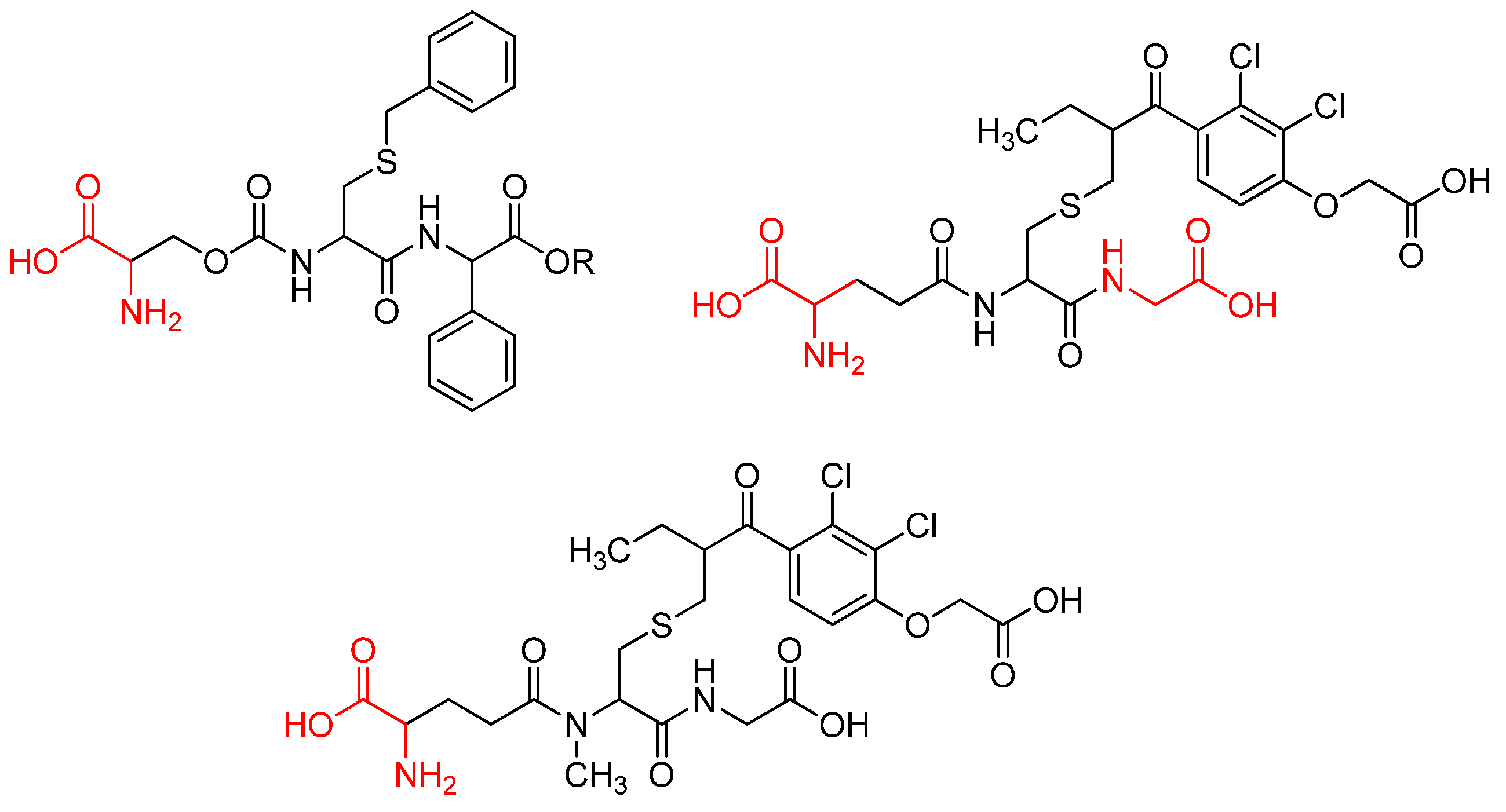

1. Introduction

2. Result and Discussion

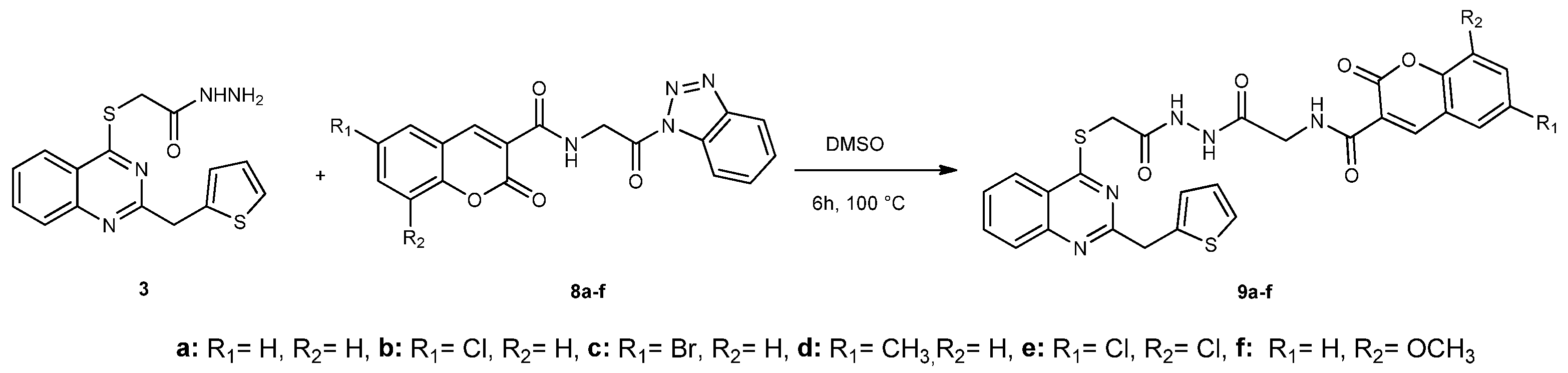

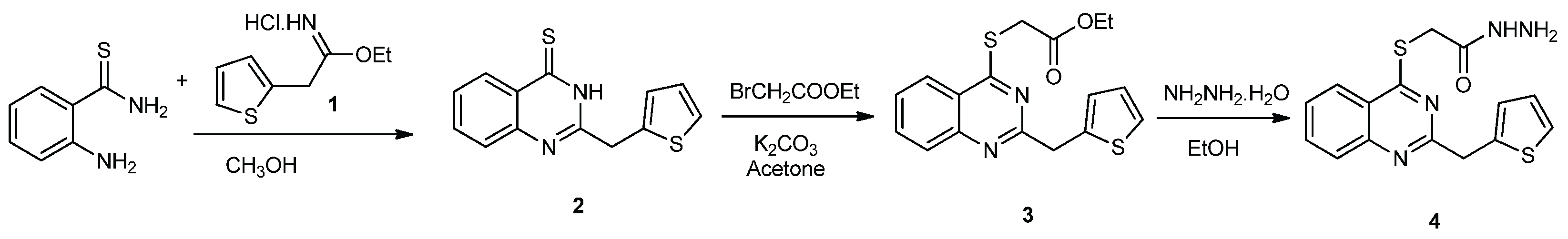

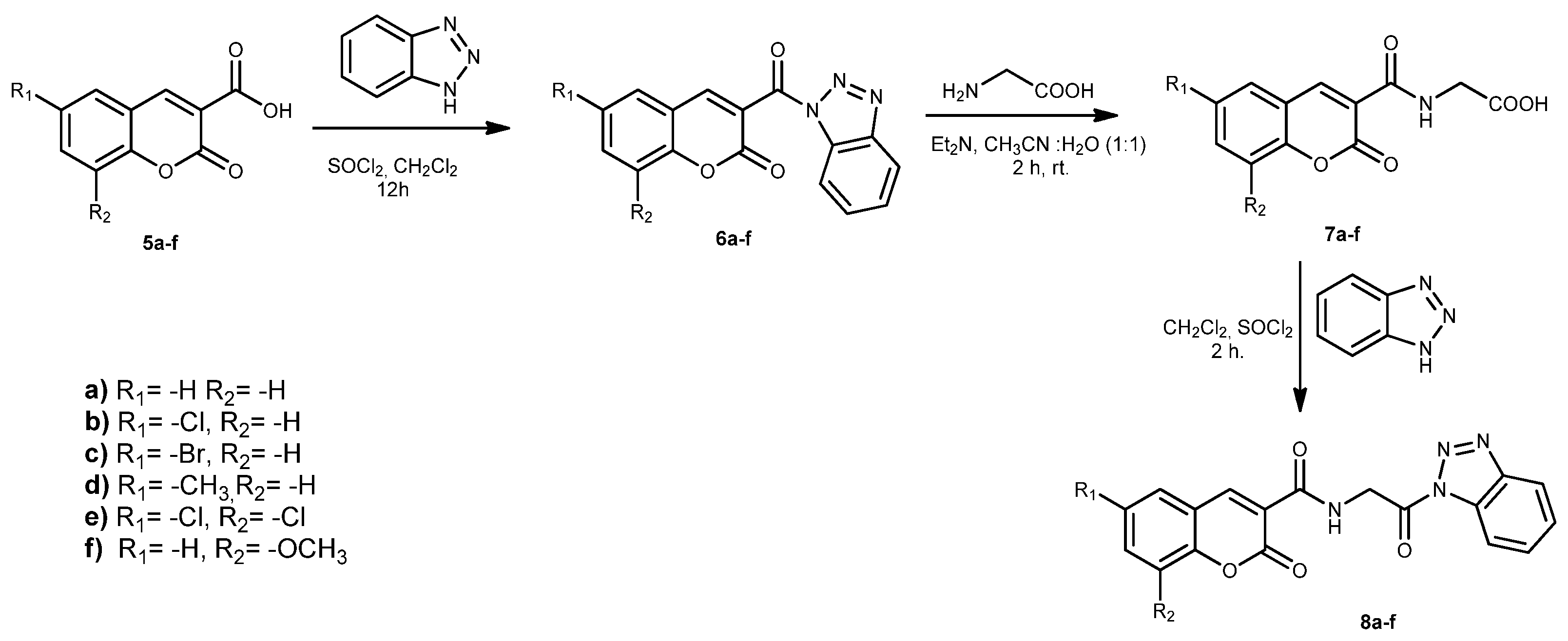

2.1. Chemistry

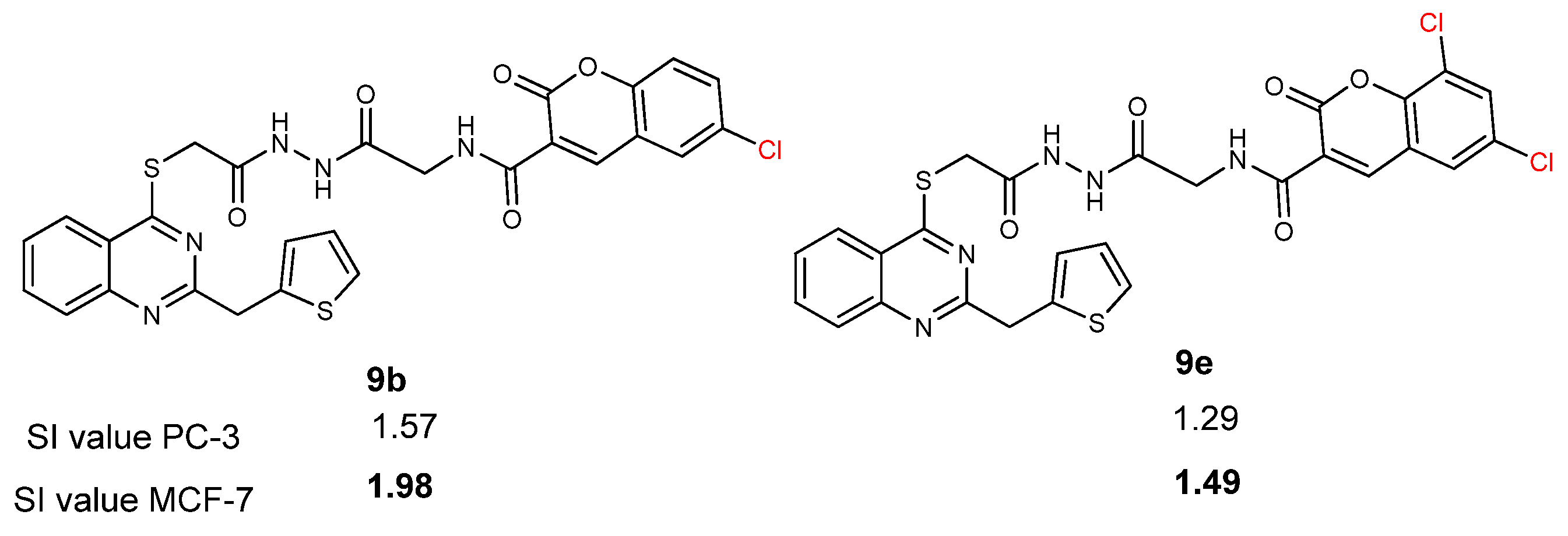

2.2. Anticancer Activity Study

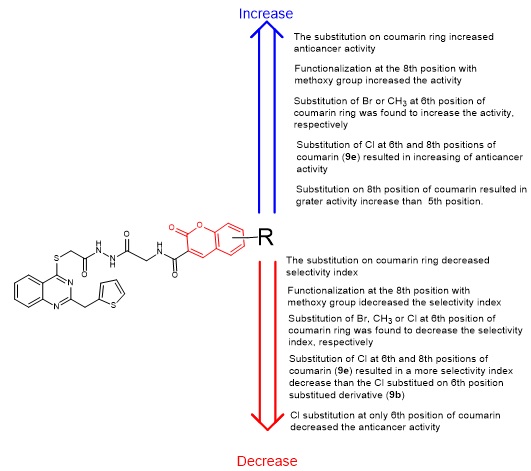

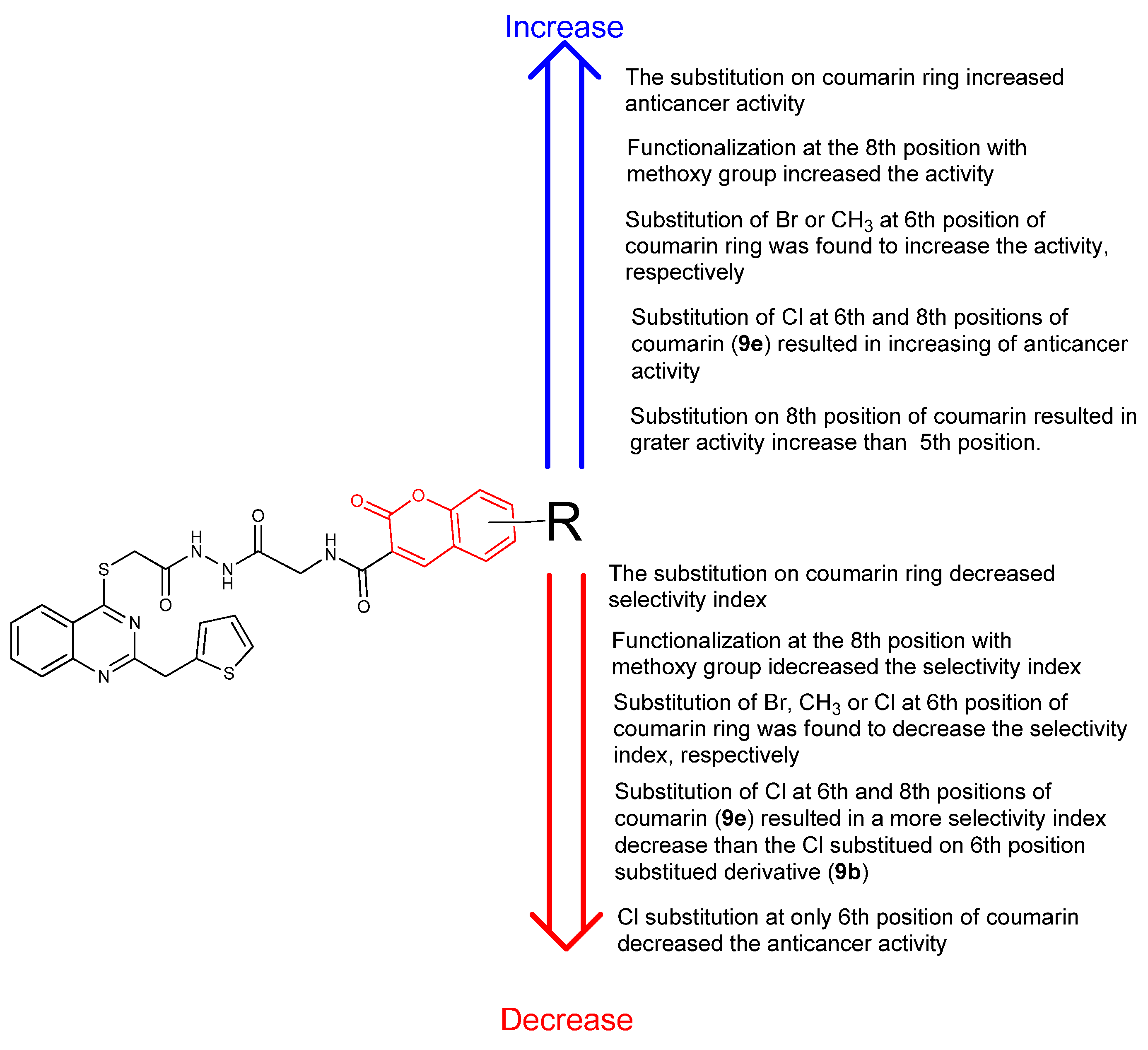

2.3. Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) Study

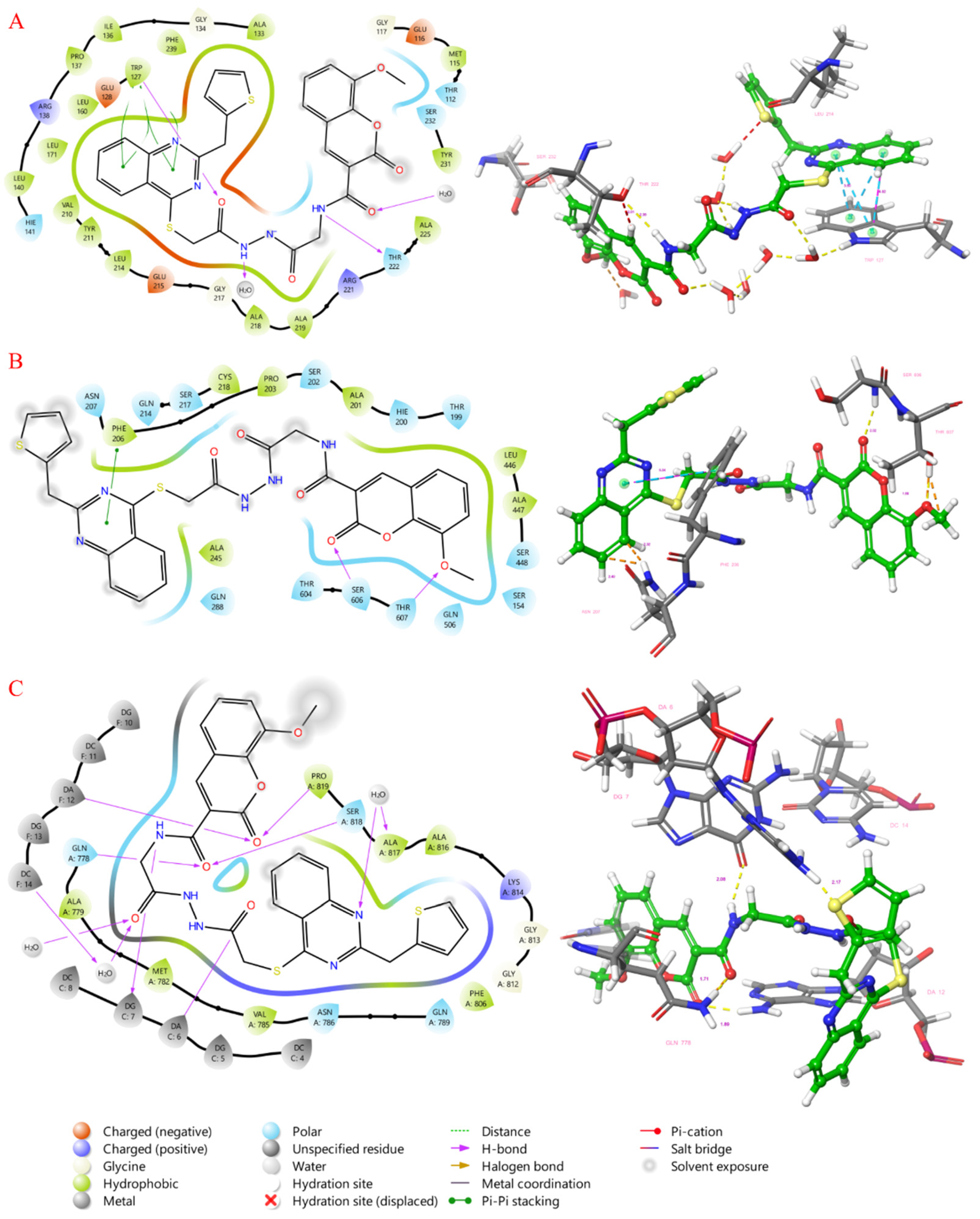

2.4. Molecular Docking Study

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Experimental Synthesis

Synthesis of Compounds 9a–f

3.2. Anticancer Activity

3.3. Molecular Docking Studies

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global Cancer Statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2024, 74, 229–263. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Cao, Z.; Prettner, K.; Kuhn, M.; Yang, J.; Jiao, L.; Wang, Z.; Li, W.; Geldsetzer, P.; Bärnighausen, T.; et al. Estimates and Projections of the Global Economic Cost of 29 Cancers in 204 Countries and Territories From 2020 to 2050. JAMA Oncol 2023, 9, 465–472. [CrossRef]

- Guida, F.; Kidman, R.; Ferlay, J.; Schüz, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Kithaka, B.; Ginsburg, O.; Mailhot Vega, R.B.; Galukande, M.; Parham, G.; et al. Global and Regional Estimates of Orphans Attributed to Maternal Cancer Mortality in 2020. Nat Med 2022, 28, 2563–2572. [CrossRef]

- James, N.D.; Tannock, I.; N’Dow, J.; Feng, F.; Gillessen, S.; Ali, S.A.; Trujillo, B.; Al-Lazikani, B.; Attard, G.; Bray, F.; et al. The Lancet Commission on Prostate Cancer: Planning for the Surge in Cases. The Lancet 2024, 403, 1683–1722. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lu, B.; He, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Du, L. Prostate Cancer Incidence and Mortality: Global Status and Temporal Trends in 89 Countries From 2000 to 2019. Front Public Health 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Leong, S.P.; Witte, M.H. Cancer Metastasis through the Lymphatic versus Blood Vessels. Clin Exp Metastasis 2024, 41, 387–402. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Wang, J.; Deng, X.; Xiong, F.; Zhang, S.; Gong, Z.; Li, X.; Cao, K.; Deng, H.; He, Y.; et al. The Role of Microenvironment in Tumor Angiogenesis. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research 2020, 39, 204. [CrossRef]

- Lugano, R.; Ramachandran, M.; Dimberg, A. Tumor Angiogenesis: Causes, Consequences, Challenges and Opportunities. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2020, 77, 1745–1770. [CrossRef]

- Saman, H.; Raza, S.S.; Uddin, S.; Rasul, K. Inducing Angiogenesis, a Key Step in Cancer Vascularization, and Treatment Approaches. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12, 1172. [CrossRef]

- Abood, R.G.; Abdulhussein, H.A.; Abbas, S.; Majed, A.A.; Al-Khafagi, A.A.; Adil, A.; Alsalim, T.A. Anti-Breast Cancer Potential of New Indole Derivatives: Synthesis, in-Silico Study, and Cytotoxicity Evaluation on MCF-7 Cells. J Mol Struct 2025, 1326, 141176. [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.D.; Ortiz, A.P.; Pinheiro, P.S.; Bandi, P.; Minihan, A.; Fuchs, H.E.; Martinez Tyson, D.; Tortolero-Luna, G.; Fedewa, S.A.; Jemal, A.M.; et al. Cancer Statistics for the US Hispanic/Latino Population, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin 2021, 71, 466–487. [CrossRef]

- Chunarkar-Patil, P.; Kaleem, M.; Mishra, R.; Ray, S.; Ahmad, A.; Verma, D.; Bhayye, S.; Dubey, R.; Singh, H.; Kumar, S. Anticancer Drug Discovery Based on Natural Products: From Computational Approaches to Clinical Studies. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 201. [CrossRef]

- Ongnok, B.; Chattipakorn, N.; Chattipakorn, S.C. Doxorubicin and Cisplatin Induced Cognitive Impairment: The Possible Mechanisms and Interventions. Exp Neurol 2020, 324, 113118. [CrossRef]

- Soltan, O.M.; Shoman, M.E.; Abdel-Aziz, S.A.; Narumi, A.; Konno, H.; Abdel-Aziz, M. Molecular Hybrids: A Five-Year Survey on Structures of Multiple Targeted Hybrids of Protein Kinase Inhibitors for Cancer Therapy. Eur J Med Chem 2021, 225, 113768. [CrossRef]

- Sharifi-Rad, J.; Cruz-Martins, N.; López-Jornet, P.; Lopez, E.P.-F.; Harun, N.; Yeskaliyeva, B.; Beyatli, A.; Sytar, O.; Shaheen, S.; Sharopov, F.; et al. Natural Coumarins: Exploring the Pharmacological Complexity and Underlying Molecular Mechanisms. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2021, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Vyas, V.K.; Bhatt, S.; Ghate, M.D. Therapeutic Potential of 4-Substituted Coumarins: A Conspectus. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry Reports 2022, 6, 100086. [CrossRef]

- An, G.; Morris, M.E. Chapter 3—Efflux Transporters in Cancer Resistance: Molecular and Functional Characterization of Breast Cancer Resistance Protein. In Drug Efflux Pumps in Cancer Resistance Pathways: From Molecular Recognition and Characterization to Possible Inhibition Strategies in Chemotherapy; Sosnik, A., Bendayan, R., Eds.; Academic Press, 2020; Vol. 7, pp. 67–96 ISBN 24683183.

- Koley, M.; Han, J.; Soloshonok, V.A.; Mojumder, S.; Javahershenas, R.; Makarem, A. Latest Developments in Coumarin-Based Anticancer Agents: Mechanism of Action and Structure–Activity Relationship Studies. RSC Med Chem 2024, 15, 10–54. [CrossRef]

- Koley, M.; Han, J.; Soloshonok, V.A.; Mojumder, S.; Javahershenas, R.; Makarem, A. Latest Developments in Coumarin-Based Anticancer Agents: Mechanism of Action and Structure–Activity Relationship Studies. RSC Med Chem 2024, 15, 10–54. [CrossRef]

- Önder, A. Anticancer Activity of Natural Coumarins for Biological Targets. In; 2020; pp. 85–109.

- Gangopadhyay, A. Plant-Derived Natural Coumarins with Anticancer Potentials: Future and Challenges. J Herb Med 2023, 42, 100797. [CrossRef]

- Mofasseri, M.; Eini, E.; Mofasseri, S.; Hanifehpour, B.; Zanbili, F.; Poursattar Marjani, A. Anticancer Potential of Coumarins from the Ferulago Genus. Results Chem 2025, 13, 102033. [CrossRef]

- Kumari, P.; Kaur, M. Coumarin-Based Hybrid Compounds: A New Approach to Cancer Therapy. J Mol Struct 2025, 1337, 142149. [CrossRef]

- Hricovíniová, J.; Hricovíniová, Z.; Kozics, K. Antioxidant, Cytotoxic, Genotoxic, and DNA-Protective Potential of 2,3-Substituted Quinazolinones: Structure—Activity Relationship Study. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 610. [CrossRef]

- Ghorab, M.M.; Abdel-Kader, M.S.; Alqahtani, A.S.; Soliman, A.M. Synthesis of Some Quinazolinones Inspired from the Natural Alkaloid L—Norephedrine as EGFR Inhibitors and Radiosensitizers. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem 2021, 36, 218–238. [CrossRef]

- Zayed, M.F. Medicinal Chemistry of Quinazolines as Anticancer Agents Targeting Tyrosine Kinases. Sci Pharm 2023, 91, 18. [CrossRef]

- Ling, Z.-N.; Jiang, Y.-F.; Ru, J.-N.; Lu, J.-H.; Ding, B.; Wu, J. Amino Acid Metabolism in Health and Disease. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8, 345. [CrossRef]

- Jing, R.; Walczak, M.A. Peptide and Protein Desulfurization with Diboron Reagents. Org Lett 2024, 26, 2590–2595. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-M.; Li, Y.; Liu, R.-F.; Xiao, J.; Zhou, B.-N.; Zhang, Q.-Z.; Song, J.-X. Synthesis, Characterization and Preliminary Biological Evaluation of Chrysin Amino Acid Derivatives That Induce Apoptosis and EGFR Downregulation. J Asian Nat Prod Res 2021, 23, 39–54. [CrossRef]

- Butler, M.; van der Meer, L.T.; van Leeuwen, F.N. Amino Acid Depletion Therapies: Starving Cancer Cells to Death. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism 2021, 32, 367–381. [CrossRef]

- Naz, S.; Shah, F.A.; Nadeem, H.; Sarwar, S.; Tan, Z.; Imran, M.; Ali, T.; Li, J.B.; Li, S. Amino Acid Conjugates of Aminothiazole and Aminopyridine as Potential Anticancer Agents: Synthesis, Molecular Docking and in Vitro Evaluation. Drug Des Devel Ther 2021, Volume 15, 1459–1476. [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, F.; Araújo, J.; Gonçalves, V.M.F.; Palmeira, A.; Cunha, A.; Silva, P.M.A.; Fernandes, C.; Pinto, M.; Bousbaa, H.; Queirós, O.; et al. Evaluation of Antitumor Activity of Xanthones Conjugated with Amino Acids. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 2121. [CrossRef]

- Çalişkan, N.; Menteşe, E.; Yilmaz, F.; Ilhan, M.S. Synthesis and Anticancer Activities of Amide-Bridged Coumarin–Quinazolinone Hybrid Compounds. Russian Journal of Organic Chemistry 2024, 60, 918–926. [CrossRef]

- Menteşe, E.; Yılmaz, F.; Menteşe, M.; Beriş, F.Ş.; Emirik, M. Developing Effective Antimicrobial Agents: Synthesis and Molecular Docking Study of Ciprofloxacin-Benzimidazole Hybrids. ChemistrySelect 2024, 9, e202303173. [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, F. Microwave-Assisted Synthesis and Investigation of Urease Inhibitory Activities of Some 1,2,4-Triazol-3-Ones Containing Salicyl and Isatin Moieties. Russ J Gen Chem 2024, 94, 2018–2022. [CrossRef]

- Güven, O.; Menteşe, E.; Bilgin Sökmen, B.; Emirik, M.; Akyüz, G. Benzimidazolone Conjugated Biscoumarins: Synthesis, Molecular Docking Studies, Urease, Lipase, and Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitory Activities. J Mol Struct 2025, 1338, 142362. [CrossRef]

- Menteşe, E.; Güzel, Y.Ü.; Akyüz, G.; Karaali, N.Ü. Synthesis of Novel Quinazolinone-Triheterocyclic Hybrides as Dual Inhibition of Urease and Ache. Journal of the Iranian Chemical Society 2024, 21, 2425–2431. [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, F. Green Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Some 1,2,4-Triazol-3-Ones. Russian Journal of Organic Chemistry 2024, 60, 513–521. [CrossRef]

- Akyüz, G.; Menteşe, E. Urease Inhibition Activity Studies of Novel Azabenzimidazole-Derived Compounds. Russ J Gen Chem 2024, 94, 2432–2437. [CrossRef]

- Akyüz, G. Synthesis and Urease Inhibition Activities of Some New Schiff Bases Benzimidazoles Containing Thiophene Ring. Russ J Bioorg Chem 2024, 50, 974–981. [CrossRef]

- Çalışkan, N.; Akyüz, G.; Menteşe, E. A Facile Ultrasonic Synthesis Approach to 3-H-Quinazolinethione Derivatives and Their Urease Inhibition Studies. Phosphorus Sulfur Silicon Relat Elem 2024, 199, 293–298. [CrossRef]

- Çalışkan, N.; Akyüz, G.; Menteşe, E. A Facile Ultrasonic Synthesis Approach to 3- H -Quinazolinethione Derivatives and Their Urease Inhibition Studies. Phosphorus Sulfur Silicon Relat Elem 2024, 199, 293–298. [CrossRef]

- Castillo, A.; Justice, M.J. The Kinesin Related Motor Protein, Eg5, Is Essential for Maintenance of Pre-Implantation Embryogenesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2007, 357, 694–699. [CrossRef]

- Aye, Y.; Li, M.; Long, M.J.C.; Weiss, R.S. Ribonucleotide Reductase and Cancer: Biological Mechanisms and Targeted Therapies. Oncogene 2015, 34, 2011–2021. [CrossRef]

- Nitiss, J.L. DNA Topoisomerase II and Its Growing Repertoire of Biological Functions. Nat Rev Cancer 2009, 9, 327–337. [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger Release 2018-4: Glide, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2018.

- Schrödinger Release 2018-4: Induced Fit Docking Protocol; Glide, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2018; Prime, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2018.

- Ahmad, Md.F.; Alam, I.; Huff, S.E.; Pink, J.; Flanagan, S.A.; Shewach, D.; Misko, T.A.; Oleinick, N.L.; Harte, W.E.; Viswanathan, R.; et al. Potent Competitive Inhibition of Human Ribonucleotide Reductase by a Nonnucleoside Small Molecule. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2017, 114, 8241–8246. [CrossRef]

- Talapatra, S.K.; Tham, C.L.; Guglielmi, P.; Cirilli, R.; Chandrasekaran, B.; Karpoormath, R.; Carradori, S.; Kozielski, F. Crystal Structure of the Eg5—K858 Complex and Implications for Structure-Based Design of Thiadiazole-Containing Inhibitors. Eur J Med Chem 2018, 156, 641–651. [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-C.; Li, T.-K.; Farh, L.; Lin, L.-Y.; Lin, T.-S.; Yu, Y.-J.; Yen, T.-J.; Chiang, C.-W.; Chan, N.-L. Structural Basis of Type II Topoisomerase Inhibition by the Anticancer Drug Etoposide. Science (1979) 2011, 333, 459–462. [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger Release 2025-2: Protein Preparation Workflow; Epik, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2024; Impact, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY; Prime, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2025.

- Schrödinger Release 2025-2: LigPrep, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2025.

| CC50 (citotoxitity 50: µg/L); SI (selectivity index) | |||||

|

Comp. no. |

Prostate cancer (PC-3) |

SI |

Breast cancer (MCF-7) |

SI | Human embryonic kidney (HEK-293) |

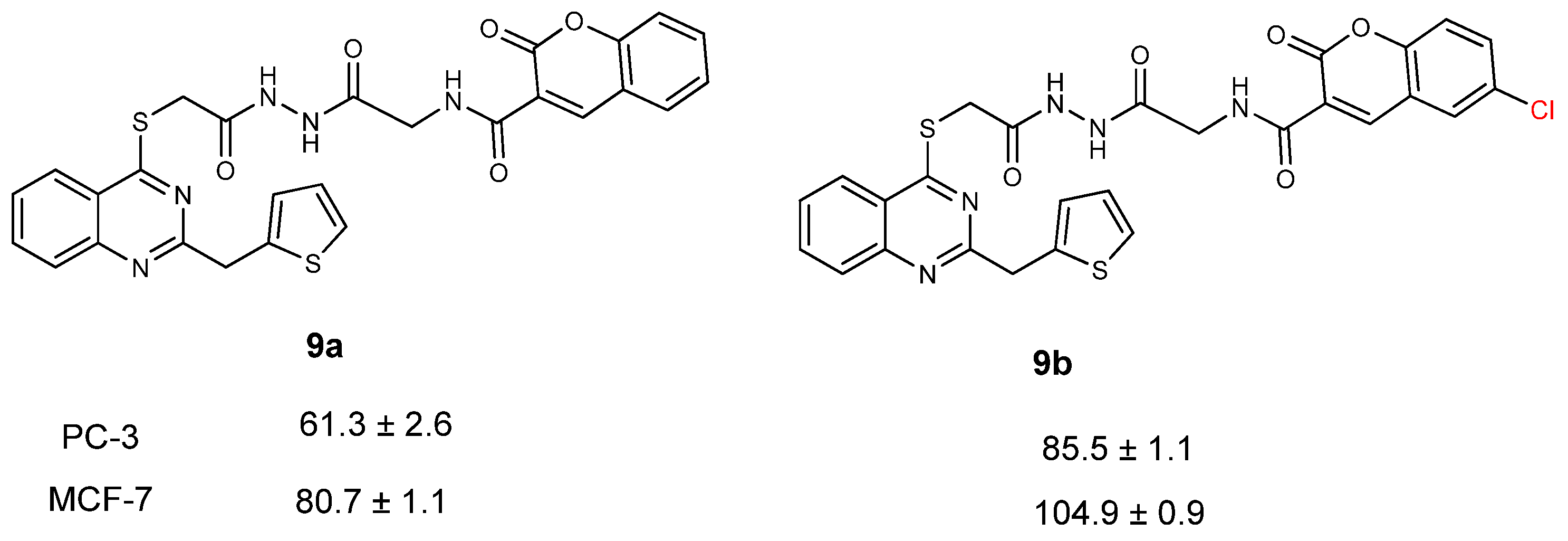

| 9a | 61.3 ± 2.6 | 3.22 | 80.7 ± 1.1 | 2.45 | 197.6 ± 1.5 |

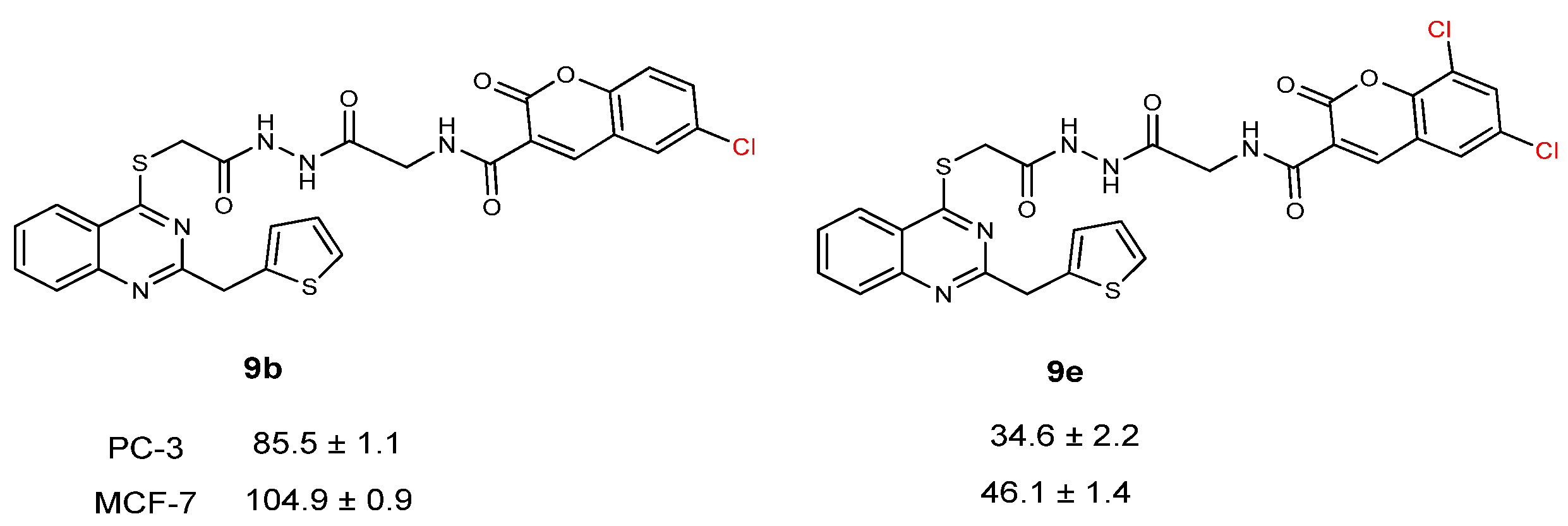

| 9b | 85.5 ± 1.1 | 1.57 | 104.9 ± 0.9 | 1.29 | 134.6 ± 1.6 |

| 9c | 47.7 ± 0.3 | 2.51 | 71.2 ± 0.2 | 1.68 | 119.9 ± 2.1 |

| 9d | 43.0 ± 0.9 | 2.14 | 74.3 ± 1.4 | 1.24 | 91.9 ± 1.4 |

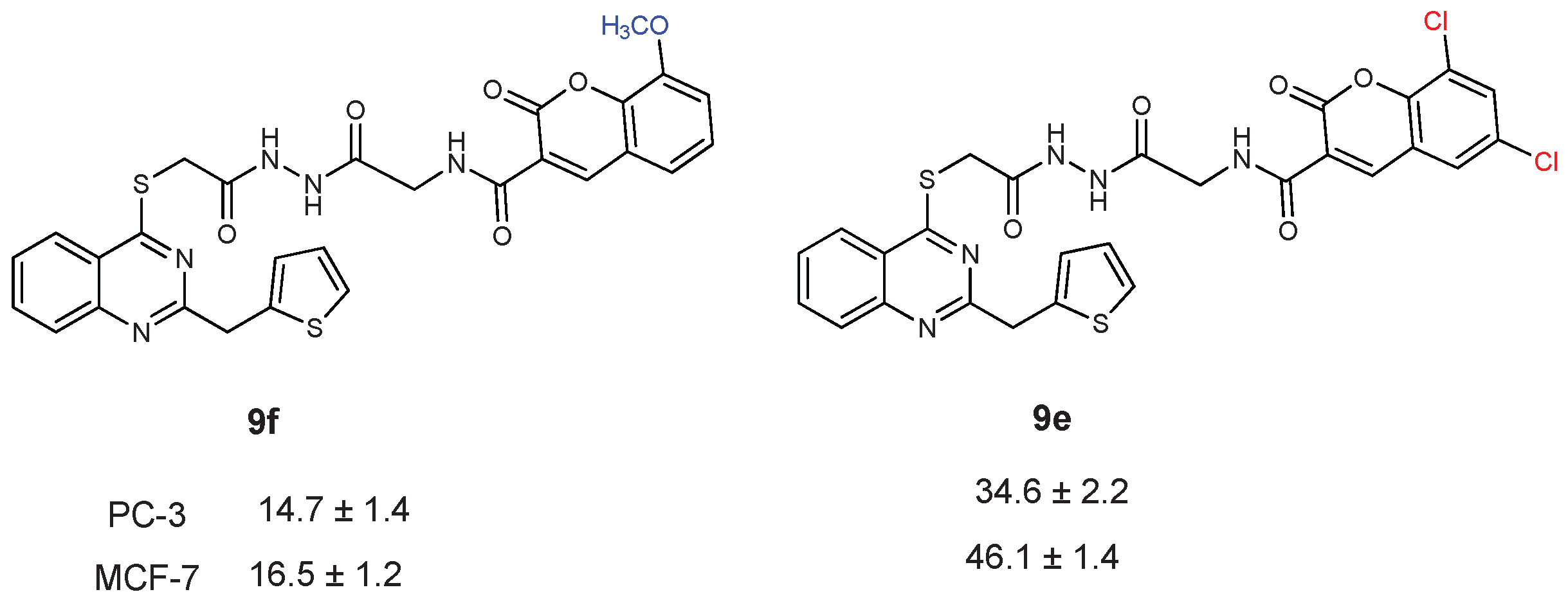

| 9e | 34.6 ± 2.2 | 1.98 | 46.1 ± 1.4 | 1.49 | 68.8 ± 0.8 |

| 9f | 14.7 ± 1.4 | 0.59 | 16.5 ± 1.2 | 0.53 | 8.7 ± 2.4 |

| Cisplatin | 24.1 ± 0.4 | 0.85 | 22.1 ± 1.0 | 0.93 | 20.6 ± 2.4 |

| 6G6Y | 5TUS | 3QX3 | |

| 9a | -11.029 | -7.99 | -9.956 |

| 9b | -11.084 | -7.133 | -8.622 |

| 9c | -11.256 | -6.627 | -10.874 |

| 9d | -11.272 | -8.368 | -9.902 |

| 9e | -10.883 | -7.603 | -8.021 |

| 9f | -11.881 | -9.088 | -12.694 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).