Submitted:

15 August 2025

Posted:

19 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Problem Statement

Gap Analysis

Objectives and Review Question

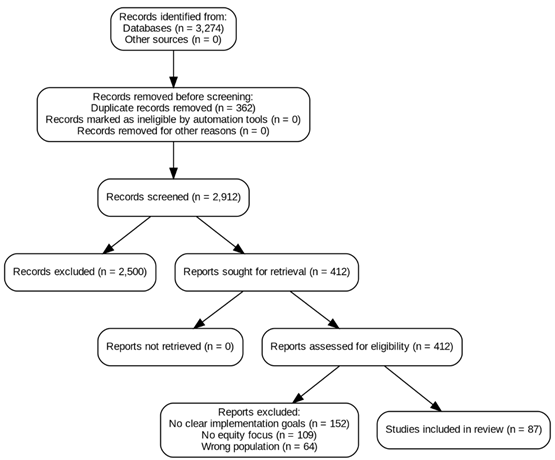

Methods

Eligibility Criteria

Search Strategy

Study Selection

Data Extraction

Quality Assessment

Data Synthesis

Results

Study Selection

Study Characteristics

| Author / Year | Country / Setting | Target Exposure | Population Characteristics | Implementation Framework Used | Intervention Type | Study Design | Key Outcomes (Environmental, Health, Implementation) | Equity Considerations |

| Campbell et al., 2011 | USA / Philadelphia | Housing quality (lead exposure) | Low-income households with children | Not explicitly named; CBPR principles applied | Home visits, tailored education, remediation | Randomized controlled trial | Reduced household lead levels, improved housekeeping practices | Targeted high-risk communities, culturally tailored materials |

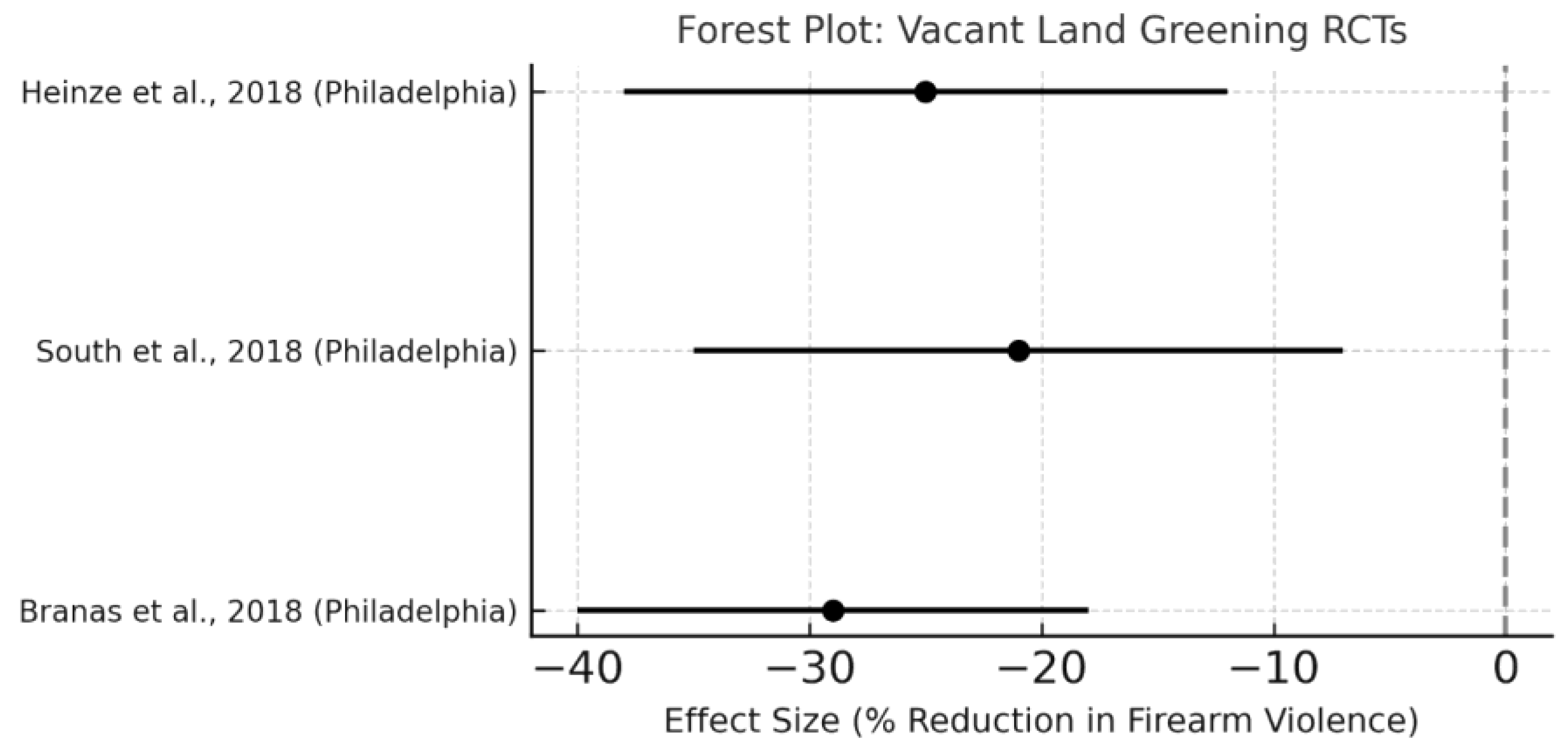

| Branas et al., 2018 | USA / Philadelphia | Urban heat, greenspace | Residents in blighted urban areas | Not specified; implicit community engagement framework | Vacant lot greening | Cluster randomized controlled trial | ↓ Firearm violence (−29%), improved mental health, increased safety perceptions | Community-selected lots, avoided displacement through local hiring |

| Garcia et al., 2013 | USA / Los Angeles | Air pollution (diesel emissions) | Port-adjacent communities | CBPR | Community air quality monitoring + policy advocacy | Mixed-methods case study | Reduced diesel emissions via Clean Air Action Plan | High community control, linked environmental data to advocacy outcomes |

| Latham & Jennings, 2022 | USA / New York City | Water quality (lead) | Public school students | Equity-focused policy implementation | Replacement of school water fixtures | Observational program evaluation | ↓ Lead exposure in students, though disparities remained | Policy targeted disadvantaged schools first |

| Heinze et al., 2018 | USA / Philadelphia | Housing quality, crime | Urban low-income neighborhoods | Community-engaged design | Housing repairs (Basic Systems Repair Program) | Quasi-experimental study | Reduced crime rates, improved housing conditions | Prioritized repairs in high-need, high-crime areas |

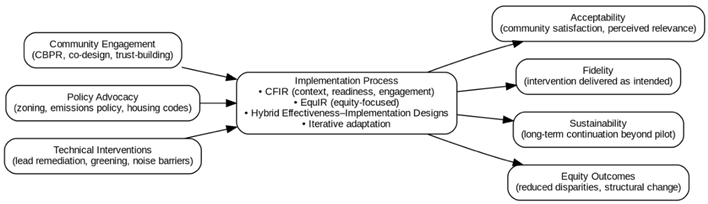

Synthesis of Findings

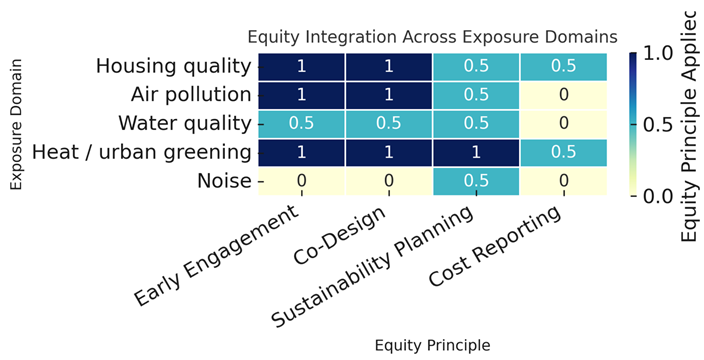

Housing Quality Interventions

Air Pollution Mitigation

Water Quality Remediation

Heat Mitigation and Urban Greening

Noise Reduction

Implementation Science Integration

| Exposure type | Number of studies | Common strategies used | Reported effectiveness | Equity outcomes | Key implementation barriers/facilitators |

| Housing quality | Many (16–30) | Home visits; tailored education; lead remediation; structural repairs; CHWs; CBPR; policy alignment; hybrid effectiveness–implementation designs | Reduced household lead levels; improved housing conditions; lower crime in some settings; improvements in self-reported health/behaviors | Targeted high-risk/low-income households; culturally tailored materials; variable reporting of equity metrics; limited >2-year follow-up | Barriers: funding continuity; landlord compliance; fragmented services. Facilitators: community trust, city repair programs, integration with public health systems |

| Air pollution | Some (6–15) | Community air monitoring; mobile/low-cost sensors; traffic/port policy advocacy; zoning and freight routing changes; CBPR coalitions | Emission reductions linked to policy actions; stronger evidence for environmental change than direct clinical endpoints | High community participation; evidence of disproportionate baseline burden; mixed evidence on narrowing disparities post-intervention | Barriers: regulatory inertia; technical capacity; sustained funding. Facilitators: CBPR leadership; cross-agency coalitions; data transparency for advocacy |

| Water quality | Some (6–15) | Participatory water testing; fixture replacement; corrosion control; school-based remediation; public reporting mandates | Documented reductions in lead exposure following remediation; gaps in randomized evidence; program evaluations predominate | Prioritized remediation in disadvantaged schools/areas; residual disparities persist | Barriers: aging infrastructure; capital costs; procurement delays. Facilitators: legal mandates; public dashboards; parent engagement |

| Heat / urban greening | Many (16–30) | Tree canopy expansion; vacant lot greening; pocket parks; cooling centers; reflective/green roofs; stewardship programs | Lower surface/air temperatures; reductions in violence in some RCTs; improved mental well-being and perceived safety | Benefits uneven without anti-displacement measures; risk of green gentrification; equity improves with co-design and local hiring | Barriers: maintenance capacity; land tenure; displacement pressures. Facilitators: community stewardship; anti-displacement policy packages; multi-agency funding |

| Noise | Few (≤5) | Highway sound barriers; building retrofits; green roofs; land-use buffer policies | Reduced noise exposures (dB) near sources; limited long-term follow-up | Equity lenses infrequently applied; exposure disparities persist | Barriers: high capital costs; ongoing enforcement. Facilitators: inclusion in planning codes; co-benefits with greening |

Agreements and Disagreements

Critical Appraisal

Discussion

Summary of Main Findings

Comparison with Existing Literature

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of the Evidence Base:

Limitations of the Evidence Base:

Strengths of this Review:

Limitations of this Review:

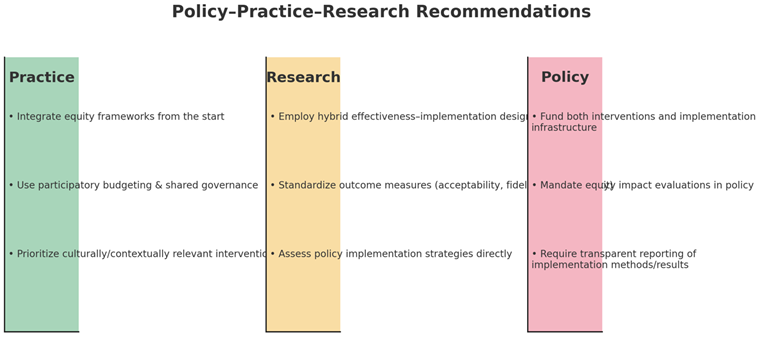

Implications for Practice, Research, and Policy

Practice

Research

Policy

Unanswered Questions and Gaps

Controversies and Ongoing Debates

Conclusion

Key Messages

Recommendations

Supplementary Materials

References

- Aarons, G.A.; Hurlburt, M.; Horwitz, S.M. Advancing a Conceptual Model of Evidence-Based Practice Implementation in Public Service Sectors. Adm. Policy Ment. Heal. Ment. Heal. Serv. Res. 2010, 38, 4–23. [CrossRef]

- Asthma Allergy Found. Am. 2020. Asthma disparities in America. A roadmap to reducing burden on racial and ethnic minorities. Rep., Asthma Allergy Found. Am., Arlington, VA. https://www.aafa.org/wp-content/ uploads/2022/08/asthma-disparities-in-america-burden-on-racial-ethnic-minorities.pdf.

- Bibbins-Domingo, K. Climate Justice and Health. JAMA 2022, 328, 2217–2217. [CrossRef]

- Braithwaite, J.; Churruca, K.; Long, J.C.; Ellis, L.A.; Herkes, J. When complexity science meets implementation science: a theoretical and empirical analysis of systems change. BMC Med. 2018, 16, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Branas CC, Cheney RA, MacDonald JM, Tam VW, Jackson TD, Ten Have TR. 2011. A difference- in-differences analysis of health, safety, and greening vacant urban space. Am. J. Epidemiol. 174:1296–306.

- Branas, C.C.; South, E.; Kondo, M.C.; Hohl, B.C.; Bourgois, P.; Wiebe, D.J.; MacDonald, J.M. Citywide cluster randomized trial to restore blighted vacant land and its effects on violence, crime, and fear. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2018, 115, 2946–2951. [CrossRef]

- Brown, P.; Mayer, B.; Zavestoski, S.; Luebke, T.; Mandelbaum, J.; McCormick, S. The health politics of asthma: environmental justice and collective illness experience in the United States. Soc. Sci. Med. 2003, 57, 453–464. [CrossRef]

- Busch, T.; Hodgson, M.; Wakefield, C. Scale-model study of the effectiveness of highway noise barriers. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2003, 114, 1947–1954. [CrossRef]

- Cacari-Stone, L.; Wallerstein, N.; Garcia, A.P.; Minkler, M. The promise of community-based participatory research for health equity: A conceptual model for bridging evidence with policy. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, 1615–1623.

- CampbellC,TranM,GracelyE,StarkeyN,KerstenH,etal.2011.Primarypreventionofleadexposure: the Philadelphia Lead Safe Homes study. Public Health Rep. 126:76–88.

- Carrión, D.; Belcourt, A.; Fuller, C.H. Heading Upstream: Strategies to Shift Environmental Justice Research From Disparities to Equity. Am. J. Public Heal. 2022, 112, 59–62. [CrossRef]

- Casey, J.A.; Daouda, M.; Babadi, R.S.; Do, V.; Flores, N.M.; Berzansky, I.; González, D.J.; Van Horne, Y.O.; James-Todd, T. Methods in Public Health Environmental Justice Research: a Scoping Review from 2018 to 2021. Curr. Environ. Heal. Rep. 2023, 10, 312–336. [CrossRef]

- Casey, J.A.; Morello-Frosch, R.; Mennitt, D.J.; Fristrup, K.; Ogburn, E.L.; James, P. Race/Ethnicity, Socioeconomic Status, Residential Segregation, and Spatial Variation in Noise Exposure in the Contiguous United States. Environ. Heal. Perspect. 2017, 125, 077017–077017. [CrossRef]

- Chicas, R.; Xiuhtecutli, N.; Elon, L.; Scammell, M.K.; Steenland, K.; Hertzberg, V.; McCauley, L. Cooling Interventions Among Agricultural Workers: A Pilot Study. Work. Heal. Saf. 2020, 69, 315–322. [CrossRef]

- Chowkwanyun M. 2023. Environmental justice: where it has been, and where it might be going. Annu. Rev. Public Health 44:93–111.

- Clark, S.; Bungum, T.; Shan, G.; Meacham, M.; Coker, L. The effect of a trail use intervention on urban trail use in Southern Nevada. Prev. Med. 2014, 67, S17–S20. [CrossRef]

- Cohen DA, Han B, Derose KP, Williamson S, Marsh T, McKenzie TL. 2013. Physical activity in parks: a randomized controlled trial using community engagement. Am. J. Prev. Med. 45:590–97.

- Crable EL, Lengnick-Hall R, Stadnick NA, Moullin JC, Aarons GA. 2022. Where is “policy” in dissem- ination and implementation science? Recommendations to advance theories, models, and frameworks: EPIS as a case example. Implement. Sci. 17:80.

- Crona, B.I.; Wassénius, E.; Jonell, M.; Koehn, J.Z.; Short, R.; Tigchelaar, M.; Daw, T.M.; Golden, C.D.; Gephart, J.A.; Allison, E.H.; et al. Four ways blue foods can help achieve food system ambitions across nations. Nature 2023, 616, 104–112. [CrossRef]

- Curran, G.M. Implementation science made too simple: a teaching tool. Implement. Sci. Commun. 2020, 1, 1–3. [CrossRef]

- Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, Pyne JM, Stetler C. 2012. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid de- signs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med. Care 50:217–26.

- Damschroder, L.J. Clarity out of chaos: Use of theory in implementation research. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 283, 112461. [CrossRef]

- Damschroder, L.J.; Aron, D.C.; Keith, R.E.; Kirsh, S.R.; Alexander, J.A.; Lowery, J.C. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement. Sci. 2009, 4, 50. [CrossRef]

- Damschroder, L.J.; Reardon, C.M.; Widerquist, M.A.O.; Lowery, J. The updated Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research based on user feedback. Implement. Sci. 2022, 17, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Davis LF, Ramírez-Andreotta MD. 2021. Participatory research for environmental justice: a critical interpretive synthesis. Environ. Health Perspect. 129:26001.

- Dodd-Butera, T.; Beaman, M.; Brash, M. Environmental Health Equity: A Concept Analysis. Annu. Rev. Nurs. Res. 2019, 38, 183–202. [CrossRef]

- Donovan, G.; Mills, J. Environmental Justice and Factors that Influence Participation in Tree Planting Programs in Portland, Oregon, U.S.. Arboric. Urban For. 2014, 40. [CrossRef]

- Eccles MP, Mittman BS. 2006. Welcome to Implementation Science. Implement. Sci. 1:1.

- Errett, N.A.; Hartwell, C.; Randazza, J.M.; Nori-Sarma, A.; Weinberger, K.R.; Spangler, K.R.; Sun, Y.; Adams, Q.H.; Wellenius, G.A.; Hess, J.J. Survey of extreme heat public health preparedness plans and response activities in the most populous jurisdictions in the United States. BMC Public Heal. 2023, 23, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Eslava-Schmalbach, J.; Garzón-Orjuela, N.; Elias, V.; Reveiz, L.; Tran, N.; Langlois, E.V. Conceptual framework of equity-focused implementation research for health programs (EquIR). Int. J. Equity Heal. 2019, 18, 80. [CrossRef]

- Ezell JM, Bhardwaj S, Chase EC. 2023. Child lead screening behaviors and health outcomes following the Flint water crisis. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 10:418–26.

- Ezell, J.M.; Chase, E.C. A Population-Based Assessment of Physical Symptoms and Mental Health Outcomes Among Adults Following the Flint Water Crisis. J. Urban Heal. 2021, 98, 642–653. [CrossRef]

- Fawkes, L.S.; McDonald, T.J.; Roh, T.; Chiu, W.A.; Taylor, R.J.; Sansom, G.T. A Participatory-Based Research Approach for Assessing Exposure to Lead-Contaminated Drinking Water in the Houston Neighborhood of the Greater Fifth Ward. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2022, 19, 8135. [CrossRef]

- Fitzhugh EC, Bassett DR Jr., Evans MF. 2010. Urban trails and physical activity: a natural experiment. Am. J. Prev. Med. 39:259–62.

- Garcia, A.P.; Wallerstein, N.; Hricko, A.; Marquez, J.N.; Logan, A.; Nasser, E.G.; Minkler, M. THE (Trade, Health, Environment) Impact Project: A Community-Based Participatory Research Environmental Justice Case Study. Environ. Justice 2013, 6, 17–26. [CrossRef]

- Garrison JD. 2021. Environmental justice in theory and practice: measuring the equity outcomes of Los Angeles and New York’s “Million Trees” campaigns. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 41:6–17.

- Garvin, E.C.; Cannuscio, C.C.; Branas, C.C. Greening vacant lots to reduce violent crime: a randomised controlled trial. Inj. Prev. 2012, 19, 198–203. [CrossRef]

- Gentile, D.A.; Morphew, T.; Elliott, J.; Presto, A.A.; Skoner, D.P. Asthma prevalence and control among schoolchildren residing near outdoor air pollution sites. J. Asthma 2020, 59, 12–22. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.K.; Shapiro, M.F.; Abramson, D. Closing the Knowledge Gap in the Long-Term Health Effects of Natural Disasters: A Research Agenda for Improving Environmental Justice in the Age of Climate Change. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2022, 19, 15365. [CrossRef]

- Gould, C.F.; Bejarano, M.L.; De La Cuesta, B.; Jack, D.W.; Schlesinger, S.B.; Valarezo, A.; Burke, M. Climate and health benefits of a transition from gas to electric cooking. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2023, 120. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M., Luhan, G. A., & Caffey, S. M. (2025). Analysis of design algorithms and fabrication of a graph-based double-curvature structure with planar hexagonal panels. arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M., Caffey, S. M., & Luhan, G. A. (2024). Exploring architectural design 3D reconstruction approaches through deep learning methods: A comprehensive survey. Athens Journal of Sciences, 11(2), 1–29. https://www.athensjournals.gr/sciences/2024-6026-AJS-Gorjian-02.pdf.

- Gorjian, M., & Quek, F. (2024). Enhancing consistency in sensible mixed reality systems: A calibration approach integrating haptic and tracking systems [Preprint]. EasyChair. https://easychair.org/publications/preprint/KVSZ.

- Gorjian, M. (2024). A deep learning-based methodology to re-construct optimized re-structured mesh from architectural presentations (Doctoral dissertation, Texas A&M University). Texas A&M University. https://oaktrust.library.tamu.edu/items/0efc414a-f1a9-4ec3-bd19-f99d2a6e3392.

- Gorjian, M., Caffey, S. M., & Luhan, G. A. (2025). Exploring architectural design 3D reconstruction approaches through deep learning methods: A comprehensive survey. Athens Journal of Sciences, 12, 1–29. [CrossRef]

- Raina, A.S.; Mone, V.; Gorjian, M.; Quek, F.; Sueda, S.; Krishnamurthy, V.R. Blended Physical-Digital Kinesthetic Feedback for Mixed Reality-Based Conceptual Design-In-Context. GI '24: Graphics Interface, Canada; pp. 1–16.

- Gorjian, M. (2024). A deep learning-based methodology to re-construct optimized re-structured mesh from architectural presentations (Doctoral dissertation, Texas A&M University). Texas A&M University. https://oaktrust.library.tamu.edu/items/0efc414a-f1a9-4ec3-bd19-f99d2a6e3392.

- Gorjian, M. (2025). Advances and challenges in GIS-based assessment of urban green infrastructure: A systematic review (2020–2024) [Preprint]. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. (2025). Analyzing the relationship between urban greening and gentrification: Empirical findings from Denver, Colorado [Working paper]. SSRN. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. (2025). From deductive models to data-driven urban analytics: A critical review of statistical methodologies, big data, and network science in urban studies [Preprint]. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. (2025). GIS-based assessment of urban green infrastructure: A systematic review of advances, gaps, and interdisciplinary integration (2020–2024) [Preprint]. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. (2025). Green gentrification and community health in urban landscape: A scoping review of urban greening’s social impacts [Preprint, Version 1]. Research Square. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. (2025). Green schoolyard investments and urban equity: A systematic review of economic and social impacts using spatial-statistical methods [Preprint]. Research Square. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. (2025). Green schoolyard investments influence local-level economic and equity outcomes through spatial-statistical modeling and geospatial analysis in urban contexts [Preprint]. arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. (2025). Greening schoolyards and the spatial distribution of property values in Denver, Colorado [Preprint]. arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. (2025). Greening schoolyards and urban property values: A systematic review of geospatial and statistical evidence [Preprint]. arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. (2025). Integrating machine learning and hedonic regression for housing price prediction: A systematic international review of model performance and interpretability [Preprint]. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. (2025). Methodological advances and gaps in urban green space and schoolyard greening research: A critical review [Preprint]. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. (2025). Quantifying gentrification: A critical review of definitions, methods, and measurement in urban studies [Preprint]. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. (2025). Schoolyard greening, child health, and neighborhood change [Preprint]. arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. (2025). Spatial economics: Quantitative models, statistical methods, and policy applications in urban and regional systems [Preprint]. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. (2025). Statistical methodologies for urban morphology indicators: A comprehensive review of quantitative approaches to sustainable urban form [Preprint]. arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. (2025). Statistical perspectives on urban inequality: A systematic review of GIS-based methodologies and applications [Preprint]. arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. (2025). The impact of greening schoolyards on residential property values [Working paper]. SSRN. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. (2025). The impact of greening schoolyards on surrounding residential property values: A systematic review [Preprint, Version 1]. Research Square. [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. (2025). Urban schoolyard greening: A systematic review of child health and neighborhood change [Preprint]. Research Square. [CrossRef]

- Hammer, M.S.; Swinburn, T.K.; Neitzel, R.L. Environmental Noise Pollution in the United States: Developing an Effective Public Health Response. Environ. Heal. Perspect. 2014, 122, 115–119. [CrossRef]

- Heaney, C.; Wilson, S.; Wilson, O.; Cooper, J.; Bumpass, N.; Snipes, M. Use of community-owned and -managed research to assess the vulnerability of water and sewer services in marginalized and underserved environmental justice communities.. 2011, 74, 8–17.

- Heinze, J.E.; Krusky-Morey, A.; Vagi, K.J.; Reischl, T.M.; Franzen, S.; Pruett, N.K.; Cunningham, R.M.; Zimmerman, M.A. Busy Streets Theory: The Effects of Community-engaged Greening on Violence. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2018, 62, 101–109. [CrossRef]

- Hering JG. 2018. Implementation science for the environment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52:5555–60.

- Hossenbaccus, L.; Linton, S.; Ramchandani, R.; Gallant, M.J.; Ellis, A.K. Insights into allergic risk factors from birth cohort studies. Ann. Allergy, Asthma Immunol. 2021, 127, 312–317. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, A.; Sheriff, G.; Chakraborty, T.; Manya, D. Disproportionate exposure to urban heat island intensity across major US cities. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Huber A. 2022. These 9 diverse innovations are paving the way for climate justice. World Econ. Forum, Feb. 17. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/02/these-9-diverse-solutions-pave-the- road- to- climate- justice/.

- Hunter, R.; Cleland, C.; Cleary, A.; Droomers, M.; Wheeler, B.; Sinnett, D.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.; Braubach, M. Environmental, health, wellbeing, social and equity effects of urban green space interventions: A meta-narrative evidence synthesis. Environ. Int. 2019, 130, 104923. [CrossRef]

- Inst. Med. 2001. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: Natl. Acad. Press.

- Kingdon J. 1984. Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies. Boston: Little, Brown and Co.

- Kwan, C.; Walsh, C. Ethical Issues in Conducting Community-Based Participatory Research: A Narrative Review of the Literature. Qual. Rep. 2018, 23, 369–386. [CrossRef]

- Landes, S.J.; McBain, S.A.; Curran, G.M. An introduction to effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 280, 112513–112513. [CrossRef]

- Lane-Fall, M.B.; Curran, G.M.; Beidas, R.S. Scoping implementation science for the beginner: locating yourself on the “subway line” of translational research. BMC Med Res. Methodol. 2019, 19, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Latham, S.; Jennings, J.L. Reducing lead exposure in school water: Evidence from remediation efforts in New York City public schools. Environ. Res. 2022, 203, 111735. [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.S.; Vos, T.; Flaxman, A.D.; Danaei, G.; Shibuya, K.; Adair-Rohani, H.; AlMazroa, M.A.; Amann, M.; Anderson, H.R.; Andrews, K.G.; et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012, 380, 2224–2260. [CrossRef]

- LouisvilleKY.gov. 2023. Louisville’s urban tree canopy assessment. LouisvilleKY.gov. https://louisvilleky. gov/government/urban-forestry/louisvilles-urban-tree-canopy-assessment.

- Mankikar, D.; Campbell, C.; Greenberg, R. Evaluation of a Home-Based Environmental and Educational Intervention to Improve Health in Vulnerable Households: Southeastern Pennsylvania Lead and Healthy Homes Program. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2016, 13, 900. [CrossRef]

- Masri, S.; LeBrón, A.M.W.; Logue, M.D.; Valencia, E.; Ruiz, A.; Reyes, A.; Wu, J. Risk assessment of soil heavy metal contamination at the census tract level in the city of Santa Ana, CA: implications for health and environmental justice. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2021, 23, 812–830. [CrossRef]

- Means, A.R.; Kemp, C.G.; Gwayi-Chore, M.-C.; Gimbel, S.; Soi, C.; Sherr, K.; Wagenaar, B.H.; Wasserheit, J.N.; Weiner, B.J. Evaluating and optimizing the consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR) for use in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Implement. Sci. 2020, 15, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Mihalakakou, G.; Souliotis, M.; Papadaki, M.; Menounou, P.; Dimopoulos, P.; Kolokotsa, D.; Paravantis, J.A.; Tsangrassoulis, A.; Panaras, G.; Giannakopoulos, E.; et al. Green roofs as a nature-based solution for improving urban sustainability: Progress and perspectives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 180, 113306. [CrossRef]

- Milio, N. Priorities and Strategies for Promoting Community-Based Prevention Policies. J. Public Heal. Manag. Pr. 1998, 4, 14–28. [CrossRef]

- Minkler, M. Linking Science and Policy Through Community-Based Participatory Research to Study and Address Health Disparities. Am. J. Public Heal. 2010, 100, S81–S87. [CrossRef]

- Minkler, M.; Garcia, A.P.; Williams, J.; LoPresti, T.; Lilly, J. Sí Se Puede: Using Participatory Research to Promote Environmental Justice in a Latino Community in San Diego, California. J. Urban Heal. 2010, 87, 796–812. [CrossRef]

- Minkler, M.; Vásquez, V.B.; Shepard, P. Promoting Environmental Health Policy Through Community Based Participatory Research: A Case Study from Harlem, New York. J. Urban Heal. 2006, 83, 101–110. [CrossRef]

- Mohai P, Pellow D, Roberts JT. 2009. Environmental justice. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 34:405–30.

- Morgan, W.J.; Crain, E.F.; Gruchalla, R.S.; O'COnnor, G.T.; Kattan, M.; Evans, R.I.; Stout, J.; Malindzak, G.; Smartt, E.; Plaut, M.; et al. Results of a Home-Based Environmental Intervention among Urban Children with Asthma. New Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351, 1068–1080. [CrossRef]

- NCSL (Natl. Conf. State Legis.). 2023. State and federal environmental justice efforts. Rep., NCSL, Washington, DC. https://www.ncsl.org/environment-and-natural-resources/state-and-federal- environmental- justice- efforts.

- Nesbitt, L.; Meitner, M.J.; Girling, C.; Sheppard, S.R.; Lu, Y. Who has access to urban vegetation? A spatial analysis of distributional green equity in 10 US cities. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 181, 51–79. [CrossRef]

- Neta, G.; Martin, L.; Collman, G. Advancing environmental health sciences through implementation science. Environ. Heal. 2022, 21, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- NIEHS (Natl. Inst. Environ. Health Sci.). 2019. Translational research framework. NIEHS. https://www. niehs.nih.gov/research/programs/translational/framework- details/index.cfm.

- NIH (Natl. Inst. Health). 2022. Dissemination and implementation research in health program announcement (R01 Clinical Trial Optional). Res. Proj., Dep. Health Hum. Serv., Washington, DC. https://grants.nih. gov/grants/guide/pa-files/PAR-22-105.html.

- Nilsen, P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement. Sci. 2015, 10, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Norton, W.E.; Chambers, D.A. Unpacking the complexities of de-implementing inappropriate health interventions. Implement. Sci. 2020, 15, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- NY City Counc. 2018. Local law no. 55. Local Laws of the City of New York for the Year 2018. https:// www.nyc.gov/assets/buildings/local_laws/ll55of2018.pdf.

- NY City Counc. 2019. Local law no. 66. Local Laws of the City of New York for the Year 2019. https:// www.nyc.gov/assets/hpd/downloads/pdfs/services/local-law-66-of-2019.pdf.

- Ornelas Van Horne Y, Alcala CS, Peltier RE, Quintana PJE, Seto E, et al. 2023. An applied environmental justice framework for exposure science. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 33:1–11.

- Paul KL, Caplins LB. 2020. Narratives of injustice: an investigation of toxic dumping within the Blackfeet Nation. Hum. Biol. 92:27–35.

- Powell, B.J.; Beidas, R.S.; Lewis, C.C.; Aarons, G.A.; McMillen, J.C.; Proctor, E.K.; Mandell, D.S. Methods to Improve the Selection and Tailoring of Implementation Strategies. J. Behav. Heal. Serv. Res. 2015, 44, 177–194. [CrossRef]

- Powell, B.J.; McMillen, J.C.; Proctor, E.K.; Carpenter, C.R.; Griffey, R.T.; Bunger, A.C.; Glass, J.E.; York, J.L. A Compilation of Strategies for Implementing Clinical Innovations in Health and Mental Health. Med Care Res. Rev. 2011, 69, 123–157. [CrossRef]

- Powell, B.J.; Waltz, T.J.; Chinman, M.J.; Damschroder, L.J.; Smith, J.L.; Matthieu, M.M.; Proctor, E.K.; E Kirchner, J. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement. Sci. 2015, 10, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Proctor, E.K.; Landsverk, J.; Aarons, G.; Chambers, D.; Glisson, C.; Mittman, B. Implementation Research in Mental Health Services: an Emerging Science with Conceptual, Methodological, and Training challenges. Adm. Policy Ment. Heal. Ment. Heal. Serv. Res. 2008, 36, 24–34. [CrossRef]

- Quinn, A.K.; Neta, G.; Sturke, R.; Olopade, C.O.; Pollard, S.L.; Sherr, K.; Rosenthal, J.P. Adapting and Operationalizing the RE-AIM Framework for Implementation Science in Environmental Health: Clean Fuel Cooking Programs in Low Resource Countries. Front. Public Heal. 2019, 7, 389. [CrossRef]

- Rabin, B.A.; Brownson, R.C.; Haire-Joshu, D.; Kreuter, M.W.; Weaver, N.L. A Glossary for Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health. J. Public Heal. Manag. Pr. 2008, 14, 117–123. [CrossRef]

- Rickenbacker, H.; Brown, F.; Bilec, M. Creating environmental consciousness in underserved communities: Implementation and outcomes of community-based environmental justice and air pollution research. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 47. [CrossRef]

- RigolonA,BrowningMHEM,McAnirlinO,YoonHV.2021.Greenspaceandhealthequity:asystematic review on the potential of green space to reduce health disparities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:2563.

- Rogers EM. 2003. Diffusion of Innovations. New York: Free Press. 5th ed.

- Rosenthal, J.; Balakrishnan, K.; Bruce, N.; Chambers, D.; Graham, J.; Jack, D.; Kline, L.; Masera, O.; Mehta, S.; Mercado, I.R.; et al. Implementation Science to Accelerate Clean Cooking for Public Health. Environ. Heal. Perspect. 2017, 125, A3–A7. [CrossRef]

- Ross, K.; Chmiel, J.F.; Ferkol, T. The Impact of the Clean Air Act. J. Pediatr. 2012, 161, 781–786. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, L.; Reames, T.G. Cooling Detroit: A socio-spatial analysis of equity in green roofs as an urban heat island mitigation strategy. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 44, 126331. [CrossRef]

- Selove R, Waltz TJ. 2023. Developing a project-specific implementation strategy glossary. QUERI Im- plementation Research Group. Health Services Research & Development. https://www.hsrd.research.va. gov/cyberseminars/catalog-upcoming-session.cfm?UID=6349.

- Slater, S.; Pugach, O.; Lin, W.; Bontu, A. If You Build It Will They Come? Does Involving Community Groups in Playground Renovations Affect Park Utilization and Physical Activity?. Environ. Behav. 2016, 48, 246–265. [CrossRef]

- South EC, Hohl BC, Kondo MC, MacDonald JM, Branas CC. 2018. Effect of greening vacant land on mental health of community-dwelling adults: a cluster randomized trial. JAMA Netw. Open 1:e180298.

- South, E.C.; Kondo, M.C.; Cheney, R.A.; Branas, C.C. Neighborhood Blight, Stress, and Health: A Walking Trial of Urban Greening and Ambulatory Heart Rate. Am. J. Public Heal. 2015, 105, 909–913. [CrossRef]

- South, E.C.; MacDonald, J.; Reina, V. Association Between Structural Housing Repairs for Low-Income Homeowners and Neighborhood Crime. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2117067–e2117067. [CrossRef]

- South EC, MacDonald JM, Tam VW, Ridgeway G, Branas CC. 2023. Effect of abandoned housing in- terventions on gun violence, perceptions of safety, and substance use in black neighborhoods: a citywide cluster randomized trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 183:31–39.

- Strane, D.; Flaherty, C.; Kellom, K.; Kenyon, C.C.; Bryant-Stephens, T. A Health System-Initiated Intervention to Remediate Homes of Children With Asthma. Pediatrics 2023, 151. [CrossRef]

- Switzer, D.; Teodoro, M.P. The Color of Drinking Water: Class, Race, Ethnicity, and Safe Drinking Water Act Compliance. J. AWWA 2017, 109, 40–45. [CrossRef]

- Tapp, H.; White, L.; Steuerwald, M.; Dulin, M. Use of community-based participatory research in primary care to improve healthcare outcomes and disparities in care. J. Comp. Eff. Res. 2013, 2, 405–419. [CrossRef]

- Tessum, C.W.; Paolella, D.A.; Chambliss, S.E.; Apte, J.S.; Hill, J.D.; Marshall, J.D. PM 2.5 polluters disproportionately and systemically affect people of color in the United States. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabf4491. [CrossRef]

- Tester, J.; Baker, R. Making the playfields even: Evaluating the impact of an environmental intervention on park use and physical activity. Prev. Med. 2009, 48, 316–320. [CrossRef]

- Tollefson, J. How science could aid the US quest for environmental justice. Nature 2022. [CrossRef]

- Umunna, I.L.; Blacker, L.S.; Hecht, C.E.; Edwards, M.A.; Altman, E.A.; Patel, A.I. Water Safety in California Public Schools Following Implementation of School Drinking Water Policies. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2020, 17, E166. [CrossRef]

- US Census Bur. 2013. American Housing Survey (AHS) Table Creator. American Housing Survey (AHS). https://www.census.gov/programs- surveys/ahs/data/interactive/ahstablecreator.html.

- US Environ. Prot. Agency. 2023. Analyze trends: EPA/State Drinking Water Dashboard. ECHO. https://echo.epa.gov/trends/comparative-maps-dashboards/drinking-water-dashboard.

- Integrated Risk Information System Page. US Environmental Protection Agency Web site. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/ (accessed on day month year).

- Waltz, T.J.; Powell, B.J.; Matthieu, M.M.; Damschroder, L.J.; Chinman, M.J.; Smith, J.L.; Proctor, E.K.; Kirchner, J.E. Use of concept mapping to characterize relationships among implementation strategies and assess their feasibility and importance: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) study. Implement. Sci. 2015, 10, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Wier M, Sciammas C, Seto E, Bhatia R, Rivard T. 2009. Health, traffic, and environmental jus- tice: collaborative research and community action in San Francisco, California. Am. J. Public Health 99(Suppl. 3):S499–504.

- Woodward, E.N.; Matthieu, M.M.; Uchendu, U.S.; Rogal, S.; Kirchner, J.E. The health equity implementation framework: proposal and preliminary study of hepatitis C virus treatment. Implement. Sci. 2019, 14, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Yeter, D.; Banks, E.C.; Aschner, M. Disparity in Risk Factor Severity for Early Childhood Blood Lead among Predominantly African-American Black Children: The 1999 to 2010 US NHANES. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1552. [CrossRef]

- Zota, A.R.; Shamasunder, B. Environmental health equity: moving toward a solution-oriented research agenda. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiology 2021, 31, 399–400. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).