1. Introduction

Spinal cord tumors represent a diverse group of central nervous system (CNS) neoplasms, classified based on their anatomical location as intradural intramedullary, intradural extramedullary, or extradural[

1]. Relatively rare compared to intracranial tumors (2-4% of primary CNS tumors), their impact on neurological function can be profound[

2]. While traditional classifications and treatment paradigms have relied heavily on histopathological features, recent advances in molecular diagnostics have revealed that genetic alterations play a crucial role in tumor behavior, prognosis, and therapeutic response[

3,

4]. The 2021 World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of CNS Tumors introduced a paradigm shift by emphasizing molecular subtypes over traditional histology, particularly for ependymomas[

5].

Molecular diagnostics have transformed the understanding of spinal cord tumors. Techniques such as DNA methylation profiling, next-generation sequencing (NGS), fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), and immunohistochemistry (IHC) have become instrumental in refining diagnoses and guiding treatment. These tools can detect specific gene fusions, mutations, and epigenetic modifications that are not evident through histology alone[

6]. This brief review focuses on the primary intramedullary spinal cord tumors with an emphasis on genetic mutations expression and how these influence clinical management. We explore the implications of these markers in radiation and chemotherapy decisions, treatment stratification, and prognostication.

2. Tumor-Specific Genetic Profiles Affecting Behavior and Prognosis

In this section, we review major primary spinal cord tumor pathologies, focusing on their molecular markers, prognostic significance, and therapeutic implications. A summary is presented in

Table 1.

2.1. Ependymoma

Ependymomas are among the most prevalent primary spinal tumors and are now classified based on molecular features. The WHO 2021 classification of spinal cord ependymomas includes spinal ependymoma (SP-EPN), spinal ependymoma with N-Myc (aka MYCN) amplification (SP-MYCN), myxopapillary ependymoma (MPE), subependymoma (SE), and neurofibromatosis 2 (NF2)-mutated variants (with losses on chromosome 22q). The SP-EPN and the rare SP-MYCN variants are exclusive to spinal cord, while the others can also happen in supratentorial and posterior fossa compartments.

While spine ependymomas (including those with NF2 mutation) are in general regarded as good prognosis,[

7] MYCN-amplified spinal ependymomas in particular exhibit aggressive behavior, rapid progression, early metastases, and leptomeningeal dissemination. The recurrence rate is reported to be in the 75-100% range.[

8] Therefore, they are associated with poorer prognosis and require multimodal therapy.[

9] On pathology, these possess high-grade features including microvascular proliferation, necrosis, and high mitotic cell count. Diagnosis of the pathognomic high MYCN amplification is confirmed by immunohistochemistry or FISH. [

10,

11] While rare, it emphasizes the importance of DNA methylation profiling and gene fusion detection for classification and guiding treatment options.

MPE is associated with a better outcome and long-term overall survival rates has been reported to exceed 90%.[

12] However, approximately 20% are associated with local or distant recurrence. As a result, they were upgraded to WHO grade 2 in the 2021 classification. While not bearing immediate prognostic data, Homebox gene HOXB13 (which is often seen in prostate cancer) has emerged as a useful immunohistochemical marker for distinguishing MPE from other spinal ependymomas,[

13,

14] playing role as a potential diagnostic marker as well as a possible therapeutic target for MPE.

Unlike cranial SEs, how genetic markers influence prognosis in spinal SEs is scarcely studied. For instance, brainstem SEs can have H3 K27M mutations without significant effect on prognosis, [

15] and loss of chromosome 6 and TERT mutations are frequent events in posterior fossa SE which harbor poorer prognosis.[

16] This yet has to be studied in spinal SE. Spinal SE do not appear to be associated with NF2 mutations either.

2.2. Ganglioglioma

Gangliogliomas are rare glioneuronal tumors in the spinal cord that resemble their intracranial counterparts but have lower frequency of BRAF V600E mutations. While these mutations are less frequent compared to brain tumors but, when present, may offer therapeutic targets.[

17,

18,

19] Most gangliogliomas are WHO grade I with favorable prognosis following resection. High-grade (anaplastic) variants exhibit increased mitotic activity and cellularity; however, genetic markers specific to spinal cord anaplastic gangliogliomas are not well described in literature and should be the subject of future research.

2.3. Astrocytoma/Glioma

Spinal astrocytomas range from WHO grades II to III (excluding the grade IV glioblastoma) and often harbor heterogeneous and distinct mutations, which does substantially affect the outcome. The histone 3 (H3) K27M mutations are the most common mutations seen in cerebral astrocytomas, especially diffuse midline gliomas, and affect the histone H3 protein, specifically in the H3F3A or HIST1H3B genes. They can also occur in spinal astrocytomas and glioblastomas and data suggest that this mutant could be seen in 40%, 40%, and 20% of grades 2, 3, and 4, respectively.[

20] While typically associated with poor prognosis,[

21,

22] recent data suggest grade II/III H3 K27M-mutant tumors may have better survival than grade IV astrocytomas, so the histology still has a higher impact on survival than the presence of this mutation per se.[

20,

23]

In contrast to the more common H3 K27M mutation, isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) mutations are relatively rare in spinal astrocytomas and these mutations (IDH) are more seen in the cerebral counterparts.

Another mutation associated with poor outcome is telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) promoter mutations, particularly in IDH-wild type (IDH-wt) tumors.[

24,

25,

26] However, it’s important to note that the prognostic significance of TERT promoter mutations can be modulated by other genetic factors. For instance, patients with these mutations and unmethylated MGMT promoters exhibit the worst survival rates, while in IDH-mutated gliomas, TERT promoter mutations may be associated with a more favorable prognosis, especially in the context of 1p/19q codeletion.[

27] Interestingly, TERT promoter mutations has a better prognosis in the presence of K27M mutations in grade 2 and 3 astrocytomas. Therefore, when considering the prognosis of spine astrocytoma with TERT promoter mutations, it is crucial to take into account the combined molecular profile of the tumor rather than solely relying on the presence of TERT mutations.

Other mutations with less clear effect on prognosis include TP53 mutations, GALR1 and GRM5 of neuroactive ligand-receptor interactions signaling pathways, and PPM1D. While their exact interaction is not well known, they might be associated with a poor outcome and tendency for malignant progression.[

23,

28]

Lastly, while effects of BRAF V600E mutations on prognosis is still not well known and controversial, their presence may identify candidates for BRAF-targeted therapies (including Vemurafenib, Dabrafenib, and Encorafenib).

2.4. Glioblastoma (GBM)

Spinal glioblastomas are exceedingly rare but highly aggressive with dismal progression-free and overall survival rates.[

29] Unlike cerebral counterparts, studies of genetic mutations specific to spinal GBM are scarce, due to rarity of the disease (1–3% of all intramedullary tumors). For instance, IDH (1 and 2) and ATRX (Alpha-Thalassemia X-linked Intellectual Disability) mutations and MGMT (O-6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase) promoter methylation are associated with slightly better prognosis in cranial GBM due to targeting the tumor to specific treatments. In contrast, TP53 mutations and EGFR (epithelial growth factor receptor) amplification are associated with worse outcomes in cranial GBMs. Still, the presence and as a result influence of these genetic markers is not well-studied in spinal GBM.[

30] Moreover, other studies (again combining cranial and spinal GBMs) have shown that SPARC (secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine) and VIM (vimentin) genes are over-expressed and CACNA1E (calcium voltage-gated channel subunit alpha1e), SH3GL2 (SH3 domain-containing GRB2-like 2, endophilin A1), and DDN (dendrin) genes are under-expressed in glioblastoma. CACNA1E and VIM exhibit better prognosis. H3F3A K27M mutations are common, and co-mutations include TP53, TERT promoter, and PIK3CA. These mutations influence survival and may impact therapeutic choices in GBM in general.[

31] To emphasize, these studies often pool cranial and spinal GBM (with cranial ones outnumbering spinal GBM). Therefore, their role in primary spinal GBMs should be selectively studied.

2.5. Hemangioblastoma

Spine hemangioblastomas, similar to their cranial counterparts, are strongly linked to mutations in the von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) gene, both in inherited (VHL disease) and sporadic cases.[32]While not directly affecting tumor behavior, it may affect outcome due to higher rate of recurrence (as a result of the syndromic nature of VHL).[33]While other rare genetic factors may also be involved in cranial hemangioblastoma, particularly in patients with aggressive tumor growth, these are not validated and confirmed in spinal ones.

3. Discussion

Integrating Genetic Data into Clinical Practice

The incorporation of genetic markers into the management of spinal cord tumors marks a significant shift from purely histopathological classification toward a biologically informed approach. Several key domains are impacted: 1) Diagnosis, 2) Risk stratification, 3) Therapeutic decision-making, 4) Surveillance, 5) Patient and family counseling, 5) Research and clinical trials.

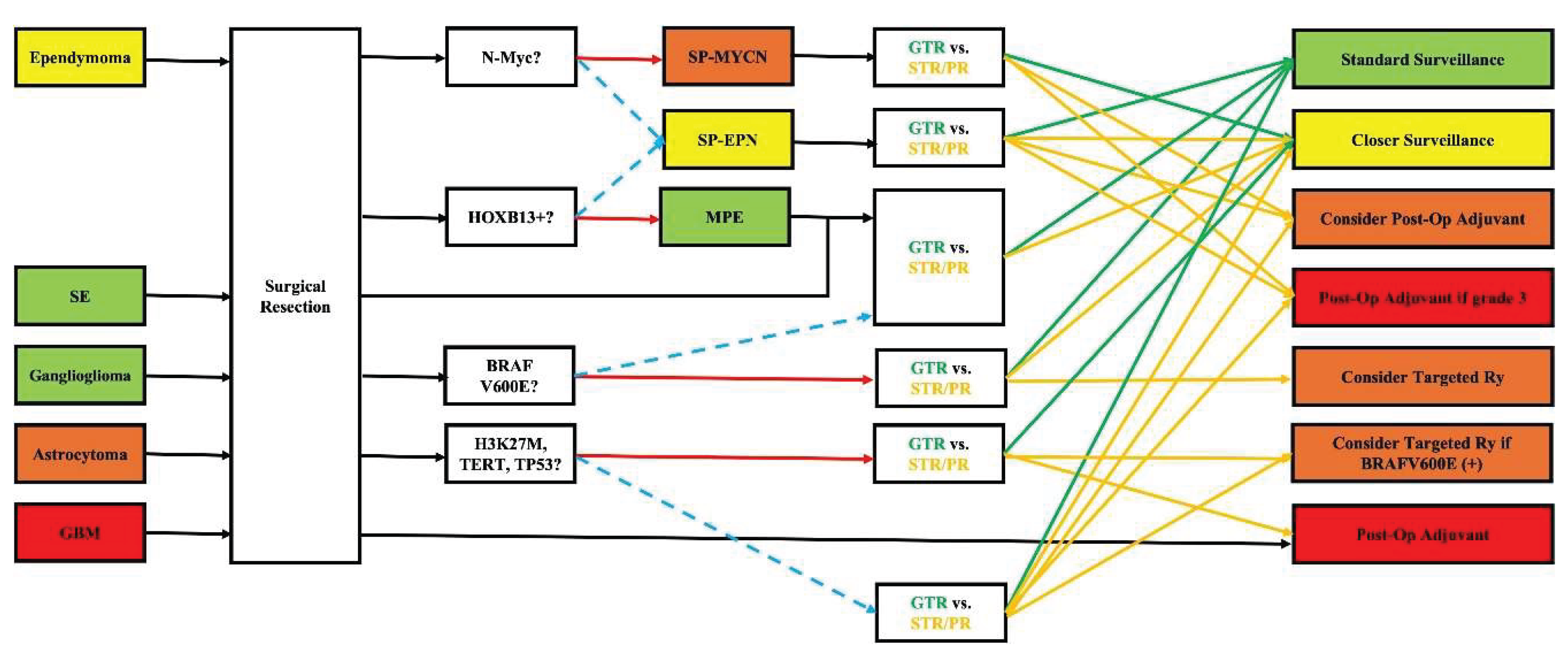

DNA methylation profiling and gene fusion detection have proven more reliable than histological grade alone in predicting prognosis. For example, the identification of

MYCN amplification in spinal ependymoma or

H3 K27M mutations in astrocytoma can guide clinicians toward more aggressive surveillance and treatment plans, even when traditional features suggest a low-grade lesion. Moreover, while

surgery remains the cornerstone for most primary intramedullary spinal cord tumors,

molecular data inform decisions about adjuvant therapy. For instance, while prognosis in ependymoma is generally favorable and achieving gross-total resection (GTR) is technically considered a “cure” without further treatment, identifying N-Myc amplification can change the standard classification to SP-MYCN bearing a worse prognosis. In these scenarios, the multi-disciplinary treatment team (including the surgeon, radiation oncologist, and medical oncologist) can decide on more frequent imaging surveillance if GTR is achieved; if sub-total resection (STR) or partial resection (PR) is achieved, adjuvant treatments (post-operative radiation +/- chemotherapy) may be considered as an earlier option (instead of waiting until recurrence happens). Likewise, identification of HOXB13 may not alter the treatment strategy (with GTR still being the goal) but confers better prognosis as it confirms diagnosis of MPE (vs. SP-EPN). For astrocytoma and GBM, the genetic mutation profile (mostly comprising of H3 K27M, TERT, and TP53) can significantly alter (worsen) the prognosis. Again, the treatment plan has to be modified to implement more frequent clinical and imaging surveillance and more aggressive treatment modalities (surgical resection, radiation, chemo, etc.). In some instances, specific markers do not alter prognosis, but they can guide toward additional beneficial treatments. For instance, the presence of

BRAF V600E mutations, particularly in gangliogliomas or astrocytomas, offers potential access to targeted inhibitors (e.g., Vemurafenib, Dabrafenib, and Encorafenib), shifting paradigms for recurrent or unresectable disease. Genetic testing also provides value in familial syndromes and counselling. Detection of

NF2 mutations in ependymomas mandates genetic counseling and long-term follow-up for other manifestations of neurofibromatosis type 2. Lastly, as the information is relatively new and its impact on clinical practice still not fully established, patients with defined alterations may be eligible for

molecularly stratified clinical trials, enabling more tailored medicine approaches in neuro-oncology for spinal tumors. A schematic workflow is proposed and depicted in

Figure 1. Of note, as previously mentioned, the field is still fresh, and most data originates from case series. Therefore, the author needs to emphasize that the whole review and suggested workflow is purposed to increase awareness about the topic and open door for future research. Practical changes and guidelines can only be concluded based on extensive multi-center large clinical trials.

4. Limitations and Future Directions

Despite its promise, the integration of genetic diagnostics into routine clinical workflow for spinal cord tumors faces several challenges. First, most genetic tests are available only in certain labs and settings and their availability is relatively limited in most practices, including community settings. Second, given the rarity of intramedullary spinal cord tumors, studies are faced with rather small sample sizes which restricts robust validation of markers. Adding to the limitation, most data stems from case series, rather than large clinical trials. Although data is more readily available about the cranial counterparts, rarity of primary intramedullary spinal tumors have refined generalizability of the data. This issue also imposes challenges on prospective clinical trials which are trying to define the impact of genetic subtypes on treatment strategies and outcomes. Lastly, overlapping genetic profiles in some tumors complicate classification. While the effects of one single mutation on outcome can be better evaluated, presence of multiple genes and genetic mutation can alter the interaction due to polygenic inheritance, epistasis, genetic linkage, etc., complicating the clinical outcome (for instance, as observed in the case of TERT promoter mutation and H3 K27M in astrocytomas). To overcome these limitations, collaborative registries and standardized panels for genetic testing are needed.

5. Conclusions

Advances in genetic profiling have reshaped our understanding of primary spinal cord tumors. Rather than relying solely on histopathology, clinicians can now stratify patients by genetic alterations, improving prognostication and treatment selection. Molecular markers such as H3 K27M, MYCN amplification, and TERT promoter mutations, among many, are not merely academic observations; they are actionable elements that can and should inform patient care. As the field evolves, it is imperative that neuro-oncology practice transitions from morphology to genetic and molecular precision, with the ultimate goal of enhancing survival and quality of life for patients with these rare but impactful tumors.

Ethics Approval

Not applicable (literature review).

Data Availability

All data discussed are derived from published studies cited in the manuscript.

Author Contributions

RML conceptualized the study, performed literature review, drafted the manuscript, and approved the final version.

Funding

This research did not receive external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dickman C FM, Gokaslan Z. Spinal Cord and Spinal Column Tumors: Principles and Practice: Thieme; 2006.

- Chamberlain MC, Tredway TL. Adult primary intradural spinal cord tumors: a review. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2011;11(3):320-8.

- Nagashima Y, Nishimura Y, Eguchi K, Yamaguchi J, Haimoto S, Ohka F, et al. Recent Molecular and Genetic Findings in Intramedullary Spinal Cord Tumors. Neurospine. 2022;19(2):262-71.

- Zhao Z, Song Z, Wang Z, Zhang F, Ding Z, Fan T. Advances in Molecular Pathology, Diagnosis and Treatment of Spinal Cord Astrocytomas. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2024;23:15330338241262483.

- Louis DN, Perry A, Wesseling P, Brat DJ, Cree IA, Figarella-Branger D, et al. The 2021 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Neuro Oncol. 2021;23(8):1231-51.

- Pratt D, Sahm F, Aldape K. DNA methylation profiling as a model for discovery and precision diagnostics in neuro-oncology. Neuro Oncol. 2021;23(23 Suppl 5):S16-s29.

- Connolly ID, Ali R, Li Y, Gephart MH. Genetic and molecular distinctions in spinal ependymomas: A review. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2015;139:210-5.

- Swanson AA, Raghunathan A, Jenkins RB, Messing-Jünger M, Pietsch T, Clarke MJ, et al. Spinal Cord Ependymomas With MYCN Amplification Show Aggressive Clinical Behavior. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2019;78(9):791-7.

- Ghasemi DR, Sill M, Okonechnikov K, Korshunov A, Yip S, Schutz PW, et al. MYCN amplification drives an aggressive form of spinal ependymoma. Acta Neuropathol. 2019;138(6):1075-89.

- Kresbach C, Neyazi S, Schüller U. Updates in the classification of ependymal neoplasms: The 2021 WHO Classification and beyond. Brain Pathol. 2022;32(4):e13068.

- Raffeld M, Abdullaev Z, Pack SD, Xi L, Nagaraj S, Briceno N, et al. High level MYCN amplification and distinct methylation signature define an aggressive subtype of spinal cord ependymoma. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2020;8(1):101.

- Gomez DR, Missett BT, Wara WM, Lamborn KR, Prados MD, Chang S, et al. High failure rate in spinal ependymomas with long-term follow-up. Neuro Oncol. 2005;7(3):254-9.

- Gu S, Gu W, Shou J, Xiong J, Liu X, Sun B, et al. The Molecular Feature of HOX Gene Family in the Intramedullary Spinal Tumors. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2017;42(5):291-7.

- Purkait S, Praeger S, Felsberg J, Pauck D, Kaulich K, Wolter M, et al. Strong nuclear expression of HOXB13 is a reliable surrogate marker for DNA methylome profiling to distinguish myxopapillary ependymoma from spinal ependymoma. Acta Neuropathol. 2025;149(1):29.

- Yao K, Duan Z, Wang Y, Zhang M, Fan T, Wu B, et al. Detection of H3K27M mutation in cases of brain stem subependymoma. Hum Pathol. 2019;84:262-9.

- Thomas C, Thierfelder F, Träger M, Soschinski P, Müther M, Edelmann D, et al. TERT promoter mutation and chromosome 6 loss define a high-risk subtype of ependymoma evolving from posterior fossa subependymoma. Acta Neuropathol. 2021;141(6):959-70.

- Gessi M, Dörner E, Dreschmann V, Antonelli M, Waha A, Giangaspero F, et al. Intramedullary gangliogliomas: histopathologic and molecular features of 25 cases. Hum Pathol. 2016;49:107-13.

- Di Nunno V, Gatto L, Tosoni A, Bartolini S, Franceschi E. Implications of BRAF V600E mutation in gliomas: Molecular considerations, prognostic value and treatment evolution. Front Oncol. 2022;12:1067252.

- Garnier L, Ducray F, Verlut C, Mihai MI, Cattin F, Petit A, et al. Prolonged Response Induced by Single Agent Vemurafenib in a BRAF V600E Spinal Ganglioglioma: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Front Oncol. 2019;9:177.

- Chai RC, Zhang YW, Liu YQ, Chang YZ, Pang B, Jiang T, et al. The molecular characteristics of spinal cord gliomas with or without H3 K27M mutation. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2020;8(1):40.

- Akinduro OO, Garcia DP, Higgins DMO, Vivas-Buitrago T, Jentoft M, Solomon DA, et al. A multicenter analysis of the prognostic value of histone H3 K27M mutation in adult high-grade spinal glioma. J Neurosurg Spine. 2021;35(6):834-43.

- Zhang F, Cheng L, Ding Z, Wang S, Zhao X, Zhao Z, et al. Does H3K27M Mutation Impact Survival Outcome of High-Grade Spinal Cord Astrocytoma? Neurospine. 2023;20(4):1480-9.

- Alvi MA, Ida CM, Paolini MA, Kerezoudis P, Meyer J, Barr Fritcher EG, et al. Spinal cord high-grade infiltrating gliomas in adults: clinico-pathological and molecular evaluation. Mod Pathol. 2019;32(9):1236-43.

- Lee Y, Park CK, Park SH. Prognostic Impact of TERT Promoter Mutations in Adult-Type Diffuse Gliomas Based on WHO2021 Criteria. Cancers (Basel). 2024;16(11).

- Gorria T, Crous C, Pineda E, Hernandez A, Domenech M, Sanz C, et al. The C250T Mutation of TERTp Might Grant a Better Prognosis to Glioblastoma by Exerting Less Biological Effect on Telomeres and Chromosomes Than the C228T Mutation. Cancers (Basel). 2024;16(4).

- Heidenreich B, Rachakonda PS, Hosen I, Volz F, Hemminki K, Weyerbrock A, et al. TERT promoter mutations and telomere length in adult malignant gliomas and recurrences. Oncotarget. 2015;6(12):10617-33.

- Arita H, Matsushita Y, Machida R, Yamasaki K, Hata N, Ohno M, et al. TERT promoter mutation confers favorable prognosis regardless of 1p/19q status in adult diffuse gliomas with IDH1/2 mutations. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2020;8(1):201.

- Liu DK, Wang J, Guo Y, Sun ZX, Wang GH. Identification of differentially expressed genes and fusion genes associated with malignant progression of spinal cord gliomas by transcriptome analysis. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):13583.

- Amelot A, Terrier LM, Mathon B, Joubert C, Picart T, Jecko V, et al. Natural Course and Prognosis of Primary Spinal Glioblastoma: A Nationwide Study. Neurology. 2023;100(14):e1497-e509.

- Liu A, Hou C, Chen H, Zong X, Zong P. Genetics and Epigenetics of Glioblastoma: Applications and Overall Incidence of IDH1 Mutation. Front Oncol. 2016;6:16.

- Li Q, Aishwarya S, Li JP, Pan DX, Shi JP. Gene Expression Profiling of Glioblastoma to Recognize Potential Biomarker Candidates. Front Genet. 2022;13:832742.

- Klingler JH, Gläsker S, Bausch B, Urbach H, Krauss T, Jilg CA, et al. Hemangioblastoma and von Hippel-Lindau disease: genetic background, spectrum of disease, and neurosurgical treatment. Childs Nerv Syst. 2020;36(10):2537-52.

- Wach J, Basaran AE, Vychopen M, Tihan T, Wostrack M, Butenschoen VM, et al. Local tumor control and neurological outcomes after surgery for spinal hemangioblastomas in sporadic and von Hippel-Lindau disease: A multicenter study. Neuro Oncol. 2025;27(6):1567-78.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).