Submitted:

19 August 2025

Posted:

20 August 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

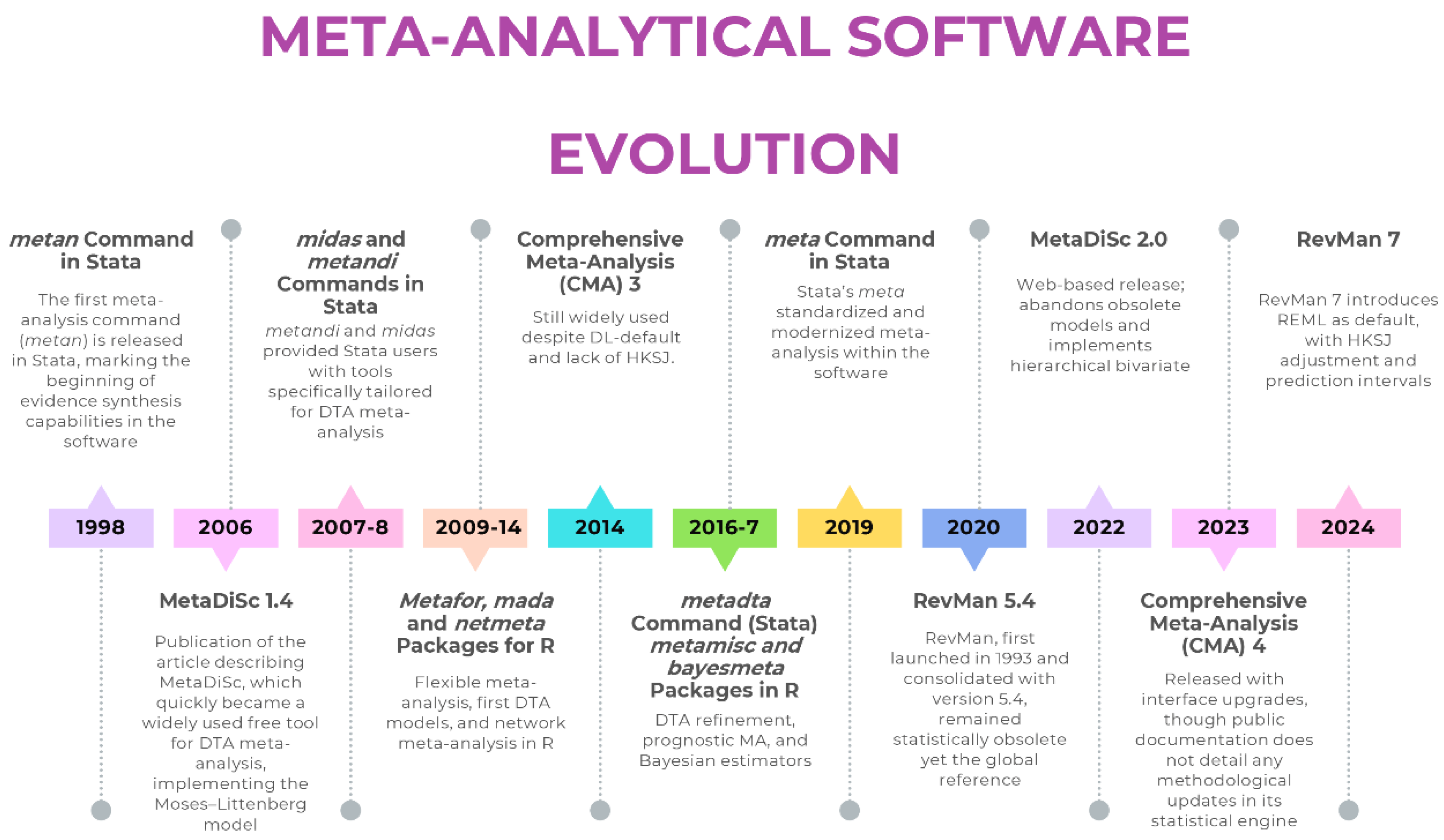

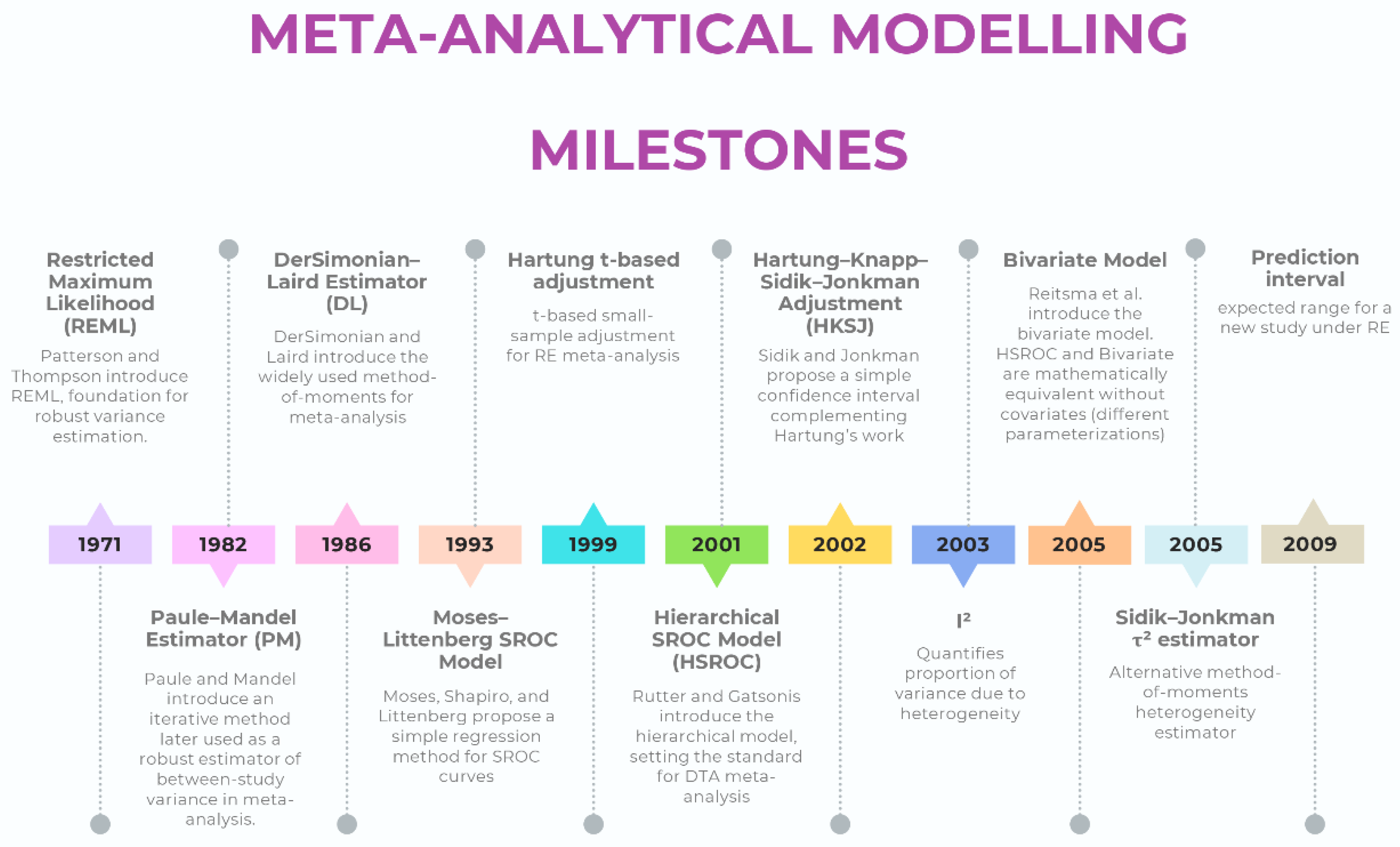

From Legacy Defaults to Modern Standards: The Evolution of User-Friendly Meta-Analysis Software

Review Manager (RevMan): A Tale of Two Versions

- For intervention reviews, RevMan 5.4 [20] defaults to the DL estimator for random-effects models—a paradigmatic hidden default. The dominance of the DL estimator did not arise arbitrarily: its computational simplicity and early endorsement facilitated widespread adoption. In scenarios with a large number of studies and low heterogeneity, its performance is often comparable to more advanced estimators. The main limitation, as consistently shown in simulation studies, is its poor performance in meta-analyses with few studies and/or substantial heterogeneity, where τ2 is systematically underestimated and confidence intervals become misleadingly narrow. More robust alternatives such as REML or PM are absent in RevMan 5.4, as are HKSJ adjustments that correct the well-documented deficiencies of Wald-type intervals. Prediction intervals—now considered essential for interpreting clinical heterogeneity—are also not provided. Even the graphical outputs are problematic: forest plots often apply a confusing label, “M-H, Random,” which is inherently contradictory. The Mantel-Haenszel (MH) method is a fixed-effect approach by definition, yet the software applies the DL random-effects estimator, creating a significant source of confusion for users.

- In diagnostic test accuracy (DTA) reviews, the limitations are even more severe. RevMan allows manual entry of bivariate HSROC parameters but does not estimate them directly from the data. Sensitivity and specificity are modeled separately rather than within a proper hierarchical bivariate framework, undermining the joint estimation of test accuracy. In practice, the software continues to generate Moses–Littenberg summary ROC curves—a model abandoned more than a decade ago—without providing hierarchical estimates that reflect between-study variability. This approach, by forcing a symmetric SROC and treating the regression slope as a threshold effect, systematically overstates accuracy compared with hierarchical models [18].

- Robust Default Estimator: The default estimator for τ2 is now REML, with DL remaining as a user-selectable option.

- HKSJ Confidence Intervals: The HKSJ adjustment is now available for calculating CIs for the summary effect, providing better coverage properties than traditional Wald-type intervals.

- Prediction Intervals: The software now calculates and displays prediction intervals on forest plots, enhancing the interpretation of heterogeneity by showing the expected range of effects in future studies.

MetaDiSc: From Obsolete Modelling to a Limited Yet Solid Modern Standard

- Bivariate Hierarchical Model: MetaDiSc 2.0 uses a hierarchical random-effects model as its core engine, modelling sensitivity and specificity as a correlated pair, correctly acknowledging that a test’s performance characteristics are not independent and vary across different study populations and settings.

- Confidence and Prediction Regions: The software generates both a 95% confidence region for the summary point (quantifying uncertainty in the mean estimate) and a 95% prediction region (illustrating the expected range of true accuracy in a future study).

Comprehensive Meta-Analysis 3 & 4: The Enduring Black Box

Current Methodological Standards for Meta-Analytic Modelling (Intervention Reviews)

Modeling (Estimator)

Confidence Intervals

Heterogeneity

Current Methodological Standards for Meta-Analytic Modelling (Diagnostic Test Accuracy Reviews)

Modeling (Estimator)

Intervals

Heterogeneity

Consequences for Evidence Synthesis

The Danger of Defaults: Undeclared Corrections and Automatic Exclusions

Call to Action

Conclusions

| Do not use RevMan 5.4, MetaDiSc 1.4, or CMA for performing meta-analyses. |

| For intervention reviews: adopt REML or PM estimators with HKSJ-adjusted CIs when indicated. Consider mHK as refinement of HKSJ when τ² is close to zero. |

| For DTA reviews: use hierarchical bivariate (Reitsma) or HSROC (Rutter & Gatsonis) models. Never model Se & Sp separately. |

| Always report PIs in random-effects models. |

| Favor transparent and reproducible solutions (R: metafor, meta, mada; Stata: meta, metadta, midas). |

| Report heterogeneity using the appropriate metrics (intervention: Q, I², τ²; DTA: τ²Se, τ²Sp, ρ), avoid univariate I² in DTA. |

| Explore heterogeneity properly through meta-regression and subgroup analyses. |

| When using methods that require continuity corrections for zero-cell studies (e.g., inverse-variance with ratio measures), always declare which correction was applied (e.g., mHA, Carter). Prefer statistical models that directly handle zero cells, such as those based on the binomial likelihood (e.g., bivariate/HSROC models in DTA) |

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Original Work

AI Use Disclosure

Conflicts Of Interest

References

- Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.5 (updated 24). Cochrane, 2024. Available from www.cochrane.org/handbook. 20 August.

- Deeks JJ, Bossuyt PM, Leeflang MM, Takwoingi Y (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Diagnostic Test Accuracy. Version 2.0 (updated 23). Cochrane, 2023. Available from https://training.cochrane.org/handbook-diagnostic-test-accuracy/current. 20 July.

- DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986, 7, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viechtbauer, W. Bias and Efficiency of Meta-Analytic Variance Estimators in the Random-Effects Model. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics 2005, 30, 261–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veroniki AA, Jackson D, Viechtbauer W, Bender R, Bowden J, Knapp G, et al. Methods to estimate the between-study variance and its uncertainty in meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods 2016, 7, 55–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paule RC, Mandel J. Consensus values and weighting factors. J Res Nat Bur Stand. 1982, 87, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Aert RCM, Jackson D. Multistep estimators of the between-study variance: The relationship with the Paule-Mandel estimator. Stat Med. 2018, 37, 2616–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hartung, J. An alternative method for meta-analysis. Biom J. 1999, 41, 901–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartung J, Knapp G. On tests of the overall treatment effect in meta-analysis with normally distributed responses. Stat Med. 2001, 20, 1771–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartung J, Knapp G. A refined method for the meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials with binary outcome. Stat Med. 2001, 20, 3875–3889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidik K, Jonkman JN. A simple confidence interval for meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002, 21, 3153–3159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IntHout, J. , Ioannidis, J.P. & Borm, G.F. The Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman method for random effects meta-analysis is straightforward and considerably outperforms the standard DerSimonian-Laird method. BMC Med Res Methodol 2014, 14, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röver, C. , Knapp, G. & Friede, T. Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman approach and its modification for random-effects meta-analysis with few studies. BMC Med Res Methodol 2015, 15, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langan D, Higgins JPT, Jackson D, Bowden J, Veroniki AA, Kontopantelis E, Viechtbauer W, Simmonds M. A comparison of heterogeneity variance estimators in simulated random-effects meta-analyses. Res Synth Methods 2019, 10, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moses LE, Shapiro D, Littenberg B. Combining independent studies of a diagnostic test into a summary ROC curve: data-analytic approaches and some additional considerations. Stat Med 1993, 12, 1293–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reitsma JB, Glas AS, Rutjes AWS, Scholten RJPM, Bossuyt PM, Zwinderman AH. Bivariate analysis of sensitivity and specificity produces informative summary measures in diagnostic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol 2005, 58, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutter CM, Gatsonis CA. A hierarchical regression approach to meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy evaluations. Stat Med. 2001, 20, 2865–2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Moses-Littenberg meta-analytical method generates systematic differences in test accuracy compared to hierarchical meta-analytical models. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016, 80, 77–87. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang J, Leeflang M. Recommended software/packages for meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy. J Lab Precis Med 2019, 4, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5) [Computer program]. Version 5.4. Copenhagen: The Cochrane Collaboration, 2020.

- Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 7.2.0. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2024. Available at revman.cochrane.org.

- Zamora J, Abraira V, Muriel A, Khan K, Coomarasamy A. Meta-DiSc: a software for meta-analysis of test accuracy data. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006, 6, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Plana, M.N. , Arevalo-Rodriguez, I., Fernández-García, S. et al. Meta-DiSc 2.0: a web application for meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy data. BMC Med Res Methodol 2022, 22, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brüggemann, P. , Rajguru, K. Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA) 3.0: a software review. J Market Anal 2022, 10, 425–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borenstein, M. Chapter 27. Comprehensive meta-analysis software. In Systematic Reviews in Health Research: Meta-analysis in Context; Egger, M., Higgins, J.P.T., Davey Smith, G., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 535–548. [Google Scholar]

- Mheissen S, Khan H, Normando D, Vaiid N, Flores-Mir C. Do statistical heterogeneity methods impact the results of meta- analyses? A meta epidemiological study. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0298526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Version 4. Borenstein M, Hedges L, Higgins J, Rothstein H. Biostat, Inc.

- Mheissen S, Khan H, Normando D, Vaiid N, Flores-Mir C. Do statistical heterogeneity methods impact the results of meta- analyses? A meta epidemiological study. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0298526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nyaga, V.N. , Arbyn, M. Metadta: a Stata command for meta-analysis and meta-regression of diagnostic test accuracy data – a tutorial. Arch Public Health 2022, 80, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roger, M. Harbord & Penny Whiting. metandi: Meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy using hierarchical logistic regression. Stata J. StataCorp LP 2009, 9, 211–229. [Google Scholar]

- Dwamena, BA. MIDAS: Stata module for meta-analytical integration of diagnostic test accuracy studies. Statistical Software Components S456880, Boston College Department of Economics, revised 13 Dec 2009.

- Doebler P, Holling H. Meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy with mada. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/mada/vignettes/mada.

- Zhou Y, Dendukuri N. Statistics for quantifying heterogeneity in univariate and bivariate meta-analyses of binary data: the case of meta-analyses of diagnostic accuracy. Stat Med. 2014, 33, 2701–2717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernán MA, Robins JM. Causal Inference: What If. Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2020.

- Weber F, Knapp G, Ickstadt K, Kundt G, Glass Ä. Zero-cell corrections in random-effects meta-analyses. Res Synth Methods 2020, 11, 913–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, JJ. , Lin, EX., Shi, JD. et al. Meta-analysis with zero-event studies: a comparative study with application to COVID-19 data. Military Med Res 2021, 8, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veroniki AA, McKenzie JE. Introduction to new random-effects methods in RevMan. Cochrane Methods Group; 2024. Available at: https://training.cochrane.

| Software | Domain focus | Main strengths (historical) | Major limitations | Status / maintenance | Adequacy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RevMan 5.4 | Interventions, DTA | Free, official Cochrane tool, intuitive interface | DL only, WT CIs, no PIs, obsolete DTA models, no advanced regression or Bayesian/network options | Obsolete, replaced by RevMan 7 | 🔴 |

| RevMan 7 (Web) | Interventions, DTA | Successor to RevMan 5.4, updated interface, integration with Cochrane systems | No full hierarchical DTA implementation#break# Still limited compared to R/Stata in advanced modeling (e.g. lack of user-adjustable meta-regression or network meta-analysis) |

Actively maintained, solves many problems of 5.4 | 🟡 |

| MetaDiSc 1.4 | DTA | First free tool for diagnostic meta-analysis, simple interface | Separate Se/Sp, Moses–Littenberg only, no hierarchical modeling, no CIs/PIs | Still widely used despite release of v2 | 🔴 |

| MetaDiSc 2 | DTA | Modernized interface, implementation of hierarchical models | Lacks the advanced flexibility of script-based platforms (e.g., handling multiple covariates, non-linear models, or advanced influence diagnostics). Limited reproducibility compared to code-based solutions. | Released but limited adoption; partially solves 1.4 problems | 🟡 |

| CMA 3 | Interventions | Affordable, easy GUI, widely adopted in early 2000s | Closed code, black-box outputs, default DL, no HKSJ, limited estimators, no transparency or reproducibility | Commercial; not updated to current methods | 🔴 |

| CMA 4 | Interventions | Affordable, easy GUI, implementation of PIs | Core model settings (e.g. estimator, CI method) remain undisclosed and presumably unchanged; problems of transparency and reproducibility persist | Commercial; not clarified if updated to current methods | 🔴 |

| R (metafor, meta, mada) | Interventions, DTA, advanced | Full implementation of robust estimators, transparency, reproducibility, continuous updates | Requires statistical literacy and coding skills | Actively maintained, methodological gold standard | 🟢 |

| Stata (meta, metadta, midas, metandi) | Interventions, DTA | Robust, validated commands, widely used in applied research | Commercial license required, statistical literacy needed | Actively maintained, highly reliable | 🟢 |

| Suboptimal modeling practice | Software | Why it is problematic | Solution / Recommended alternative |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random-effects with DL | RevMan 5.4, CMA | Underestimates between-study variance (τ²), produces overly narrow CIs | Use REML or PM estimators |

| WT CIs with k > 2 and τ² > 0 | RevMan 5.4, CMA | Coverage too low, especially with few studies or high heterogeneity | Apply HKSJ adjustment or present both CIs (WT and HKSJ). |

| No PI | RevMan 5.4, CMA | Fails to quantify expected range of effects in new settings | Implement prediction intervals in R or Stata |

| Separate modeling of Se & Sp | MetaDiSc 1.4 | Ignores correlation between Se & Sp → biased and incomplete inference | Use hierarchical bivariate model (Reitsma) |

| Moses–Littenberg SROC | MetaDiSc 1.4 | Obsolete, produces biased summary curve, no proper CI or PI | Use HSROC (Rutter & Gatsonis) or bivariate model |

| No meta-regression with robust estimators, no multivariable meta-regression | RevMan 5.4, MetaDiSc 1.4, CMA | Limits exploration of heterogeneity | Use meta-regression in R or Stata |

| Black-box closed code | CMA | Opaque algorithms, no transparency, limited reproducibility | Use script-based software (R or Stata) |

| Lack of advanced models (Bayesian, network, hierarchical) | All three | Cannot handle complexity of modern evidence synthesis | Use R (netmeta, bayesmeta) or Bayesian frameworks (JAGS, Stan) |

| Undeclared continuity correction (mHA) | RevMan 5.4, CMA (NS) | Artificially inflates effect estimates, especially in small or zero-cell studies | Use models handling zero cells directly (e.g. beta-binomial or Peto for rare events; in DTA, use bivariate/HSROC); alternatively, declare correction explicitly. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).