INTRODUCTION

Continuing Medical Education (CME), or continuous professional development (CPD),plays a vital role in ensuring that more than 100 million medical professionals globally maintain up-to-date knowledge and clinical competencies[

1]. When implemented effectively, CME can positively influence clinicians’ attitudes, enhance their knowledge and skills, and ultimately improves patients’outcomes[

2]. Accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare professionals are increasingly choosing CME online platforms due to their flexibility and accessibility[

3]; a trend that most likely will continue to expand..

Whilst various e-learning approaches have demonstrated improvements in knowledge acquisition, evidence on their effectiveness especially within CME remains limited[

4,

5]. As artificial intelligence (AI) gains traction in medical education[

6], blended learning models that combine self-paced, AI-guided platforms with traditional synchronous methods may offer a promising route to improving learning outcomes and participant engagement. The Epistudia platform introduces such an approach, delivering a structured, evidence-based CME curriculum that integrates an expert input with an AI-driven personalization. It is designed to facilitate the development of CME content focused on evidence-based topics. Through the integration of AI, Epistudia enables the conversion of expert knowledge into personalized CME e-courses with minimal manual input. This process allows for rapid CME-course creation and facilitates a timely updates of the medical content, addressing the need for an up-to-date content in the context of rapidly evolving medical knowledge.

This study evaluates the effectiveness and acceptability of this blended, expert-informed AI-based training (EIAT) in CME-accredited training. Whilst CME is primarily aimed at licensed healthcare providers, selected advanced medical students may also be eligible to participate for educational purposes.

OBJECTIVES

Primary Objective:

To assess the effectiveness and overall satisfaction of an expert-informed AI-based training (EIAT) in comparison to the live on-site and / or online expert teaching as part of CME.

Secondary Objectives:

a) To evaluate participants’ completion rate of EIAT and live expert-led training (LET), and to compare the differences between the two modalities.b) To evaluate participants’ competence and engagement.c) To compare participants’ satisfaction between EIAT and LETd) To collect CME-relevant feedback aligned with Union Européenne des Médecins Spécialistes – European Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (UEMS-EACCME) standards.

METHODS

Study Design:

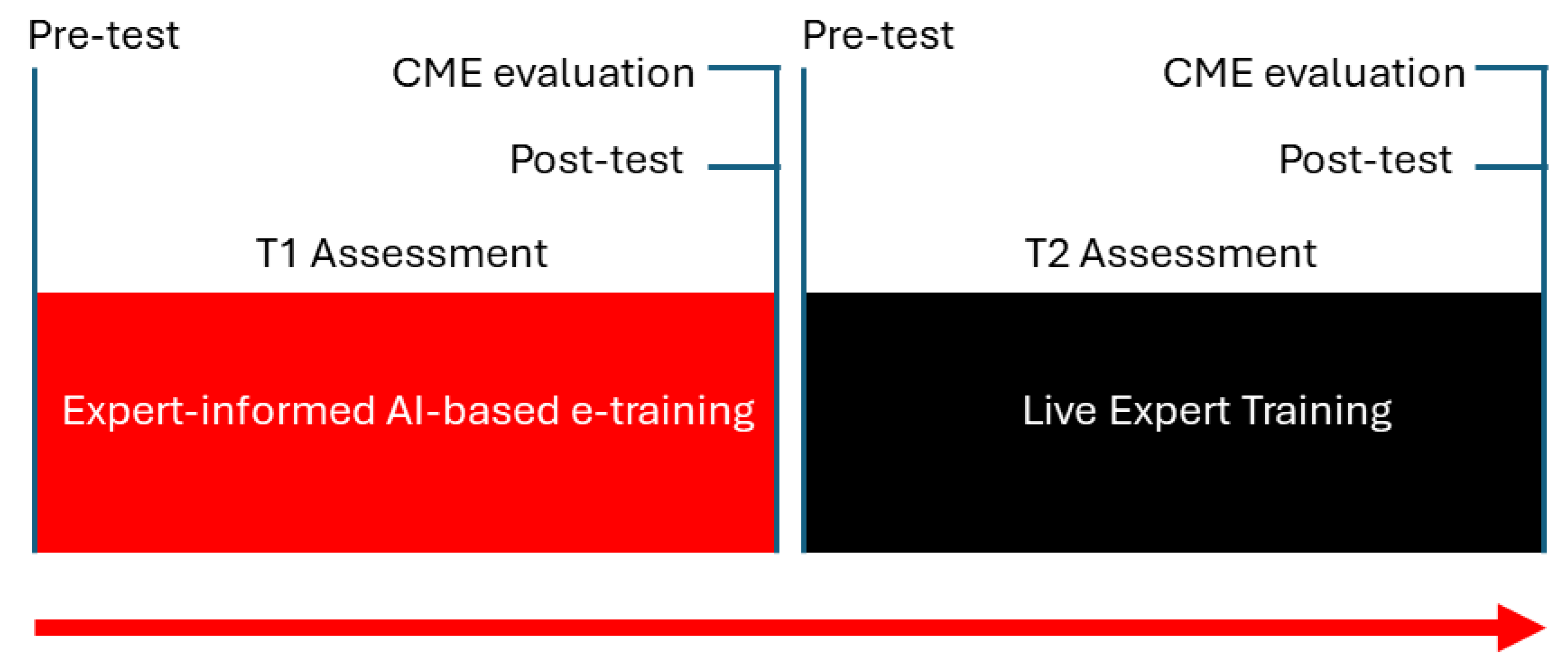

A within-subject, pre-post intervention study was conducted (

Figure 1). All participants followed EIAT and afterwards, LET. The protocol of the study is published at the Open Science Framework and can be found at

https://osf.io/4tkec

Participants and inclusion criteria:

Eligible participants were medical doctors and medical students aged 18 years or older who registered for the course on the Epistudia platform before 2 July, 2025, and had not previously completed two or more training modules. The United Kingdom Albanian Medical Society (UKAMS) promoted the event through its network and social media channels, inviting interested individuals to register. Upon registrations, the participants received an email with a request for informed consent to participate in the study, along with instructions for accessing and completing the training in Epistudia e-learning platform. Only those who provided informed consent were included in the study. The LET was conducted on-site in London, United Kingdom, with the option to participate online via Zoom.

Module A: EIAT (Steps 1–16)

From 2 to 17 July 2025, participants were asked to complete the EIAT modules on the Epistudia platform. This component included video-trainings, exercises, and reading materials and aimed to teach the core skills necessary for conducting a systematic review and meta-analysis. During this period, two email reminders to complete the training were sent to all participants.

Module B: LET (Steps 17–24)

Participants who finished the EIAT were then provided with access to Module B content, which covered the advanced steps of the course, on the Epistudia platform and attended live training sessions either on-site or via Zoom. The live sessions were designed to reinforce and expand upon the online material.

Data Collection

Information about their professional background and their place of medical practice or study was gathered in the registration form. The study outcomes data were collected at two time-points:

T1: 2 – 18 July: This was before the start of -EIAT (Module A), and after EIAT, T2: 18 – 19 July: This was before the start of the LET and after LET, either on-site or Zoom.

T1 assessment (2 – 18 July2025) and Test: A multiple-choice test assessing the knowledge delivered in Module A was administered on the Epistudia platform at the beginning and at the end of the Module A training. At the end of Module A, participants were asked to complete the T1 assessment, a CME-aligned evaluation, on the Epistudia platform. The T1 assessment evaluates the participants’ knowledge, effectiveness of the training, and overall satisfaction with the Module A. Completion of both Module A and T1 was mandatory in order to progress to the next phase.

T2 assessment (18 – 19 July2025) and Test: A multiple-choice test assessing the knowledge delivered in Module B was administered on the Epistudia platform before and after the live sessions. After completing Module B, participants were asked to complete the T2 assessment for the LET, which was the same as the T1 CME-aligned evaluation and was also administered through the Epistudia platform.

Outcomes and Questionnaire:

Completion of the EIAT was defined by the successful completion of all reading materials, exercises, and videos within each module, as tracked automatically by the Epistudia e-learning platform. The system required participants to complete each section before progressing to the next. Attendance-based completion of the LET was confirmed by the participants’ presence during the final afternoon session, either on-site or online, as monitored by the course organizers. The multiple-choice tests for both modalities included 20 questions, totaling 100 points. Participants were asked to complete an evaluation form (see Appendix 1) approved by UEMS-EACCME as part of the CME accreditation process for the course. This evaluation form covers several key domains: Overall Satisfaction and Recommendation (Q1, Q18, Q19, Q20), Engagement and Effort (see Q2, Q3, Q13), Learning Outcomes and Practical Impact (Q4, Q14), Course Design and Content Quality (Q5–Q9, Q11–Q12), and Fairness and Assessment (Q10). Additionally, it includes essential CME quality assurance items addressing bias, conflict of interest, and transparency (Q15–Q17).

Data Analysis:

The final analysis included participants who completed Module A/ EIAT and submitted the exam following the EIAT. The completion rate of Module A /EIAT was assessed, and afterwards, the completion rate was calculated for participants who, after finishing Module A, proceeded to Module B/ LET by completing the pre-exam test. To assess the participants’ knowledge acquisition, satisfaction, and self-perceived competence, descriptive statistics was used to summarize responses for both Modules, A and B. All continuous measurements were standardized on a common scale (e.g., 1 to 10) to facilitate interpretability. Responses from EIAT and LET were compared using paired t-tests for continuous outcomes. Due to small sample sizes, for paired nominal data, responses were consolidated into two categories and McNemar’s test was applied to compare outcomes across related groups or time points. Finally, the qualitative feedback was analysed thematically to identify key insights and inform future improvements to the CME program. Analysis were conducted using Excel and Stata 16.1

Ethical Considerations:

All data collected from participants were kept anonymous and confidential and were downloaded as excel files. Participants were informed that their responses will be used solely for the purposes of enhancing educational quality and for scholarly dissemination. By completing the evaluation forms, participants provided their implied consent to take part in this process.

Results

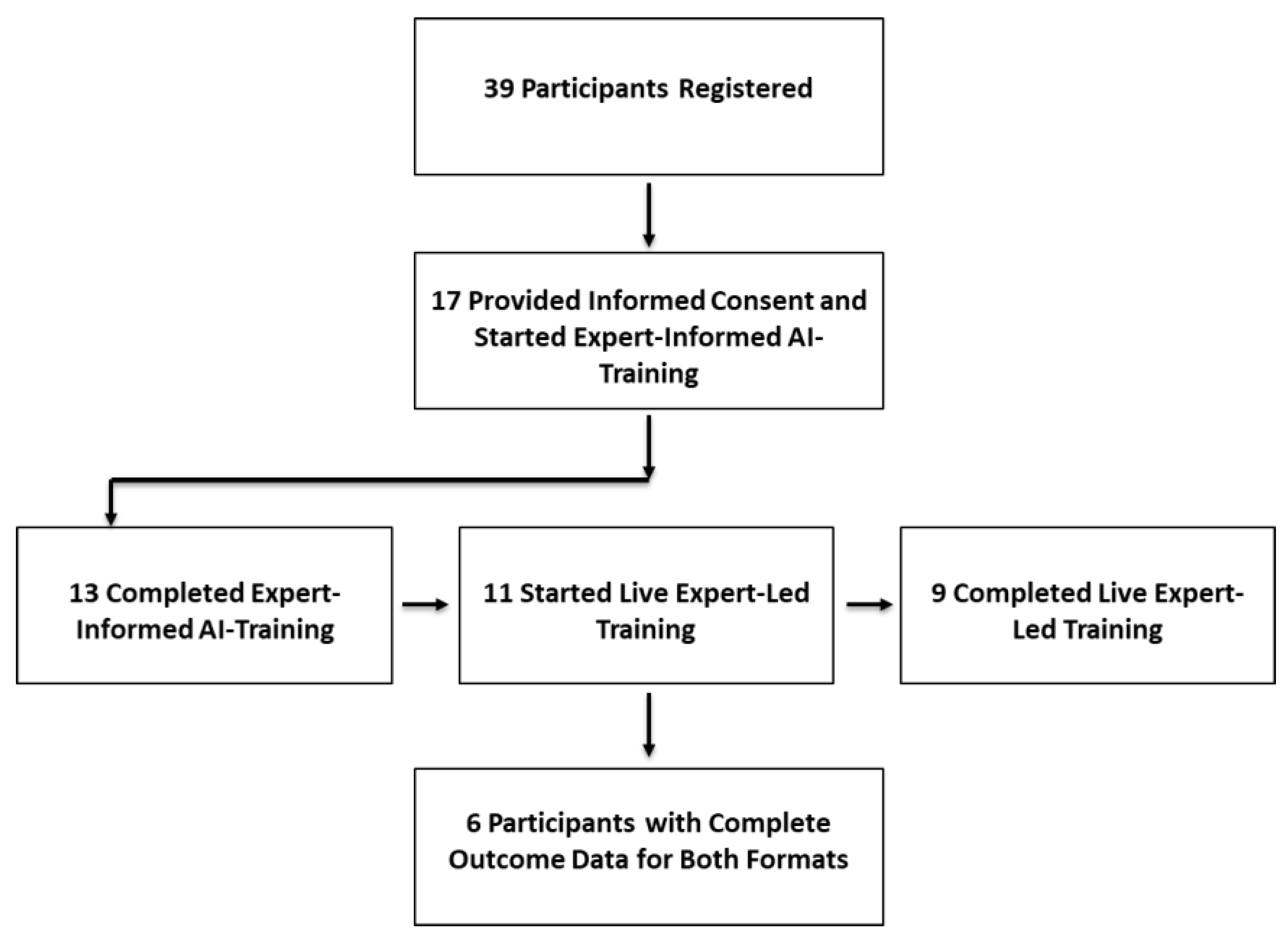

A total of 39 participants were registered for the training, either through the Epistudia website or by contacting the organizing committee directly. Of these, 17 participants provided informed consent and started the EIAT course on the Epistudia platform, forming the final study population (

Figure 2). Among the 17 participants, 10 were clinicians, 2 were medical students, 2 were researchers, and 3 reported other professional backgrounds. Geographically, 12 participants were based in the United Kingdom, 1 in the United States, and 4 in Albania and North Macedonia.

Completion Rate:

Of the 17 participants who provided informed consent, 13 completed all 24 learning activities of the EIAT, including the pre-exam (Figure 2). The remaining 4 participants completed nine or fewer activities, resulting in a completion rate of 76%. All 13 participants who completed the required learning activities also took the post-training exam, and 10 of them submitted evaluation forms (Figure 2). Of 13 participants that completed EIAT, 11 participated in the LET (Figure 2). Of those participants, 9 completed the live-session training (82%), 6 completed the post exam and 7 the course evaluation form (Figure 2).

Learning Outcome: Exam Evaluation

In the EIAT, participants demonstrated a significant improvement in knowledge, with mean exam scores increasing from 73.8 ± 11.2 (pre-exam) to 93.5 ± 5.5 (post-exam) out of 100. The average gain was 17.3 ± 13.3 points, indicating a signficiant learning effect (p = 0.0005). Similarly, participants in the live session showed a notable improvement, with mean scores rising from 63 ± 11.4 (pre-exam) to 93.3 ± 9.3 (post-exam). The average gain was 29.17 ± 13.2 points (p = 0.003). While LET resulted in a higher mean knowledge gain compared to the EIAT (mean difference: 14.2 ± 21.5), this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.17). Furthermore, no significant difference was observed between the post-exam scores of the two training formats (p = 0.79), suggesting both delivery methods were comparably effective in achieving high post-training performance (

Table 1)

20. questions-CME-aligned evaluation (Table 2 and 3):

Tables 2 and 3 present the results of the 20-question CME-aligned evaluation, organized by each assessed domain.

Satisfaction:

Participant satisfaction was high across both learning formats. When asked how likely they were to recommend the course to a friend or colleague, respondents gave a mean rating of 9.7 (SD = 0.67) for the EIAT and 10 (SD = 0) for LET, with no significant difference between the two formats (p > 0.05). Overall course ratings were similarly positive, with mean scores of 9.8 (SD = 0.63) for EIAT and 9.7 (SD = 0.76) for LET. Again, no significant difference was observed (p> 0.05), indicating consistently strong approval of the course experience across both delivery methods (

Table 2).

Table 3 presents a summary of the responses to the open-ended questions. Participants reported satisfaction with both the expert-informed AI-based and live expert-led training formats, highlighting clarity, structure, practical relevance and flexibility as key strengths. While both formats were praised for their educational value, LET participants noted technical setup challenges and suggested more hands-on group activities, whereas EIAT learners emphasized the need for a larger question bank and pre-assessment of statistical knowledge.

Engagement and Effort:

In terms of engagement and effort, both EIAT and live ELT participants demonstrated strong involvement, though differences emerged in the extent of effort. Learners in the expert-informed AI-training were more likely to complete only the assigned coursework (90%), whereas those in the live expert-led training were more inclined to go beyond requirements (28.6% vs. 10%), suggesting potentially higher intrinsic motivation or opportunity for deeper engagement in the live expert-led format. When asked about involvement, 71.4% of LET participants described themselves as enthusiastically involved, compared to 60% of EIAT participants, albeit no significant differences between the two training modalities was observed (p = 0.31). The enjoyment of coursework was rated highly in both groups, with EIAT learners reporting a mean score of 9.0 (SD = 1.41) and LET participants slightly higher at 9.43 (SD = 1.5) (p = 0.10).

Learning Outcomes and Practical Impact:

Practical knowledge gained from the course varied notably between groups. A significantly higher percentage of LET participants (85.8%) reported gaining a great deal of practical knowledge compared to 50% of EIAT participants (p = 0.08). Regarding implementation of knowledge in practice, both groups reported similar intent: 60% of EIAT and 57.1% of LET participants indicated they would apply the knowledge “very much” (p = 0.99), suggesting equivalent perceived relevance regardless of format.

Course Design and Content Quality:

Participants rated the design and quality of the course content highly across both formats, with no significant differences observed in any assessed aspect (all p-values > 0.05). For the expert-informed AI-based e-training, both the clarity of course objectives and the alignment of procedures and assignments with those objectives received mean ratings of 9.8 (SD = 0.63). For the live training, these elements were rated slightly lower at 9.1 (SD = 1.1) and 9.4 (SD = 0.1), respectively. The amount of coursework was considered appropriate in both formats: M = 9.4 (SD = 1.35) for EIAT and M = 9.3 (SD = 1.03) for LET. Course presentations were also rated as effective in explaining key concepts (EIAT: M = 9.4, SD = 1.35; M = 10.0, SD = 0; LET: M = 9.7, SD = 0.8). The syllabus was regarded as clear and valuable for professional development, with ratings of M = 9.4 (SD = 1.35 and SD = 0.97) for EIAT and M = 9.7 (SD = 0.82) for LET. Finally, the quality and relevance of course materials were rated very highly across both formats (EIAT: M = 9.8, SD = 0.63; LET: M = 10, SD = 0), and content repetition was minimal (EIAT: M = 9.33, SD = 1.00; LET: M = 10, SD = 0).

Fairness and Assessment:

Perceptions of assessment fairness were uniformly positive. Both groups gave high ratings for grading fairness, with EIAT participants rating it 9.8 (SD = 0.63) and LET participants rating it a perfect 10 (SD = 0.0) (p = 0.36). Similarly, both formats maintained a strong standard of CME compliance and transparency. While only 40% of EIAT participants noted faculty conflict-of-interest declarations, 85.7% of LET affirmed these were provided (p = 0.08), indicating more consistent adherence to disclosure practices in the live training setting.

CME Quality Assurance:

Trust in the objectivity of course content remained high across both formats. EIAT participants rated the absence of commercial bias at 9.8 (SD = 0.63), closely aligning with the perfect score of 10 from LET attendees (p = 0.36), reflecting a strong consensus on the course’s credibility and neutrality.

Discussion:

Our pilot study demonstrated that EIAT is well-received by both healthcare professionals and medical students, with high levels of satisfaction, engagement, and perceived applicability of the knowledge to clinical practice. Additionally, participants showed improvement in knowledge acquisition, as measured both subjectively (self-perceived) and objectively (exam performance). While the EIAT yielded outcomes comparable to those of LET, participants reported slightly higher engagement and involvement with the the LET format, although the differences were not statistically significant.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the effectiveness of EIAT specifically within the context of CME and professional development. Previous studies on e-learning have investigated a range of modalities including video modules, computer-assisted learning, gamified approaches, and live webinars and have generally found them to be comparable in effectiveness to traditional instructional methods[

7,

8,

9]. Consistent with our findings, a randomized pre-post study in Italy involving 39 family medicine residents showed that video module instruction was as effective as traditional teaching in improving knowledge and satisfaction[

10]. A study conducted in two Welsh medical schools found that one hour of e-learning led to greater knowledge acquisition than one hour of lecture-based teaching[

11]. Unlike Welsh study, our study included a broader sample of healthcare professionals and a smaller number of medical students, following a research skill training. The higher receptiveness to e-learning among younger learners may lead to a favorable effect of e-learning modalities. Moreover, in our study, the content of the training differed between the two formats, which may have influenced learning experiences and challenges. Nonetheless, our study builds on existing research by introducing EIAT, a novel approach that, unlike many traditional e-learning methods, requires less effort to develop and allows for more flexible and timely updates to course content. This adaptability is particularly valuable in biomedical education, where knowledge evolves rapidly.

Live expert-led training demonstrated higher levels of engagement and involvement compared to EIAT training, although the difference was not statistically significant. In our study, the AI-based training consisted of video instruction and self-guided exercises, but did not include interactive elements or feedback for participants. The absence of real-time interaction, gamification, or dynamic exercise features that were integrated into the live expert-led sessions may account for the observed differences in engagement. Supporting this, a study conducted among undergraduate students in Groningen found that incorporating game-based learning led to significantly higher engagement and involvement compared to passive video-based instruction[

12]. These findings suggest that the addition of interactive components, such as gamification or real-time feedback, could enhance the effectiveness and appeal of AI-based training formats.

While our study has several strengths, including the training was CME-accredited and resembling a real-world scenario, it also has several limitations. Firstly, both participants and assessors were not blinded to the intervention. However, outcome assessments were conducted independently of the assessors, which likely minimized potential bias. Secondly, the level of difficulty in the learning content may have differed between the two training modalities. This could partly explain why participants in the expert-informed AI-based group scored higher on the pre-test compared to those in the live expert-led group, suggesting that the learning difficulty in LET was higher. The extent to which knowledge and learning outcomes were influenced by content difficulty remains unclear. Thirdly, the study may have been underpowered to detect statistically significant differences between the two training formats, and as such, the comparative findings and respective p-values should be interpreted with caution. Fourthly, participation in the LET was defined as being present at both the start and end of the session, which may have overestimated actual engagement, as it did not account for periods of inactivity during the training. Completion in the EIAT may have been overestimated, as it was primarily based on video module tracking and did not verify engagement with optional self-paced exercises or active interaction with reading materials. Additionally, because only participants who had completed EIAT were included in LET, those in LET may have been more motivated, potentially contributing to higher completion rates. Given differences in difficulty in learning activities between the two modalities may have been present, comparisons of completion rates should be interpreted with caution. For example, if learning activities in LET could be considered more difficult, similar completion rate or knowledge gain could also indicate greater efficacy. Fifth, because EIAT always preceded LET, a carryover/practice effect may be present; without counterbalancing or an order term, we cannot disentangle this from modality effects. Future studies should incorporate randomization or counterbalancing to better isolate modality effects. Lastly, the generalizability of our results may be limited due to the specific participant population. Extending these findings to other clinical specialties or to broader applications beyond CME requires further investigation.

In conclusion, our pilot study highlights the potential of EIAT as a tool to enhance CME. Future studies with larger sample sizes and more rigorous designs are needed to determine whether this approach could be effectively and formally integrated into professional training programs.

Conflicts of Interest

Taulant Muka is the co-founder and CEO of Epistudia GmbH.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Embassy of Kosovo and the Albanian Embassy in London for their logistical support of the event, the United Kingdom Albanian Medical Society for organizing and supporting the training, and KAYAV for their sponsorship to training.

Funding

No financial support was received for the current study

Data Availability

Data can be available upon request to authors.

References

- Cervero, R.M. and J.K. Gaines, The impact of CME on physician performance and patient health outcomes: an updated synthesis of systematic reviews. J Contin Educ Health Prof, 2015. 35(2): p. 131-8. [CrossRef]

- Mazmanian, P.E. and D.A. Davis, Continuing medical education and the physician as a learner: guide to the evidence. JAMA, 2002. 288(9): p. 1057-60.

- Mueller, M.R., et al., Physician preferences for Online and In-person continuing medical education: a cross-sectional study. BMC Med Educ, 2024. 24(1): p. 1142.

- Savage, A.J., et al., Review article: E-learning in emergency medicine: A systematic review. Emerg Med Australas, 2022. 34(3): p. 322-332. [CrossRef]

- Li, M., et al., The effectiveness of blended learning in nursing and medical education: An umbrella review. Nurse Educ Pract, 2025. 86: p. 104421. [CrossRef]

- Triola, M.M. and A. Rodman, Integrating Generative Artificial Intelligence Into Medical Education: Curriculum, Policy, and Governance Strategies. Acad Med, 2025. 100(4): p. 413-418. [CrossRef]

- Morgado, M., et al., Full title: Video-based approaches in health education: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep, 2024. 14(1): p. 23651.

- Feng, J.Y., et al., Systematic review of effectiveness of situated e-learning on medical and nursing education. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs, 2013. 10(3): p. 174-83.

- Viljoen, C.A., et al., Is computer-assisted instruction more effective than other educational methods in achieving ECG competence amongst medical students and residents? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open, 2019. 9(11): p. e028800.

- Garcia-Rodriguez, J.A. and T. Donnon, Using Comprehensive Video-Module Instruction as an Alternative Approach for Teaching IUD Insertion. Fam Med, 2016. 48(1): p. 15-20.

- Mohee, K., et al., Comparison of an e-learning package with lecture-based teaching in the management of supraventricular tachycardia (SVT): a randomised controlled study. Postgrad Med J, 2022. 98(1157): p. 187-192.

- Buijs-Spanjers, K.R., et al., A Web-Based Serious Game on Delirium as an Educational Intervention for Medical Students: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Serious Games, 2018. 6(4): p. e17.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).