Submitted:

15 August 2025

Posted:

18 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Classification of Diabetes-Induced Neurological Disorders

2.1. Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy (DPN)

2.2. Diabetic Autonomic Neuropathy (DAN)

2.3. Central Nervous System (CNS) Complications of Diabetes

3. Pathophysiological Mechanisms

3.1. Hyperglycemia and Glucotoxicity

3.1.1. Polyol Pathway Activation

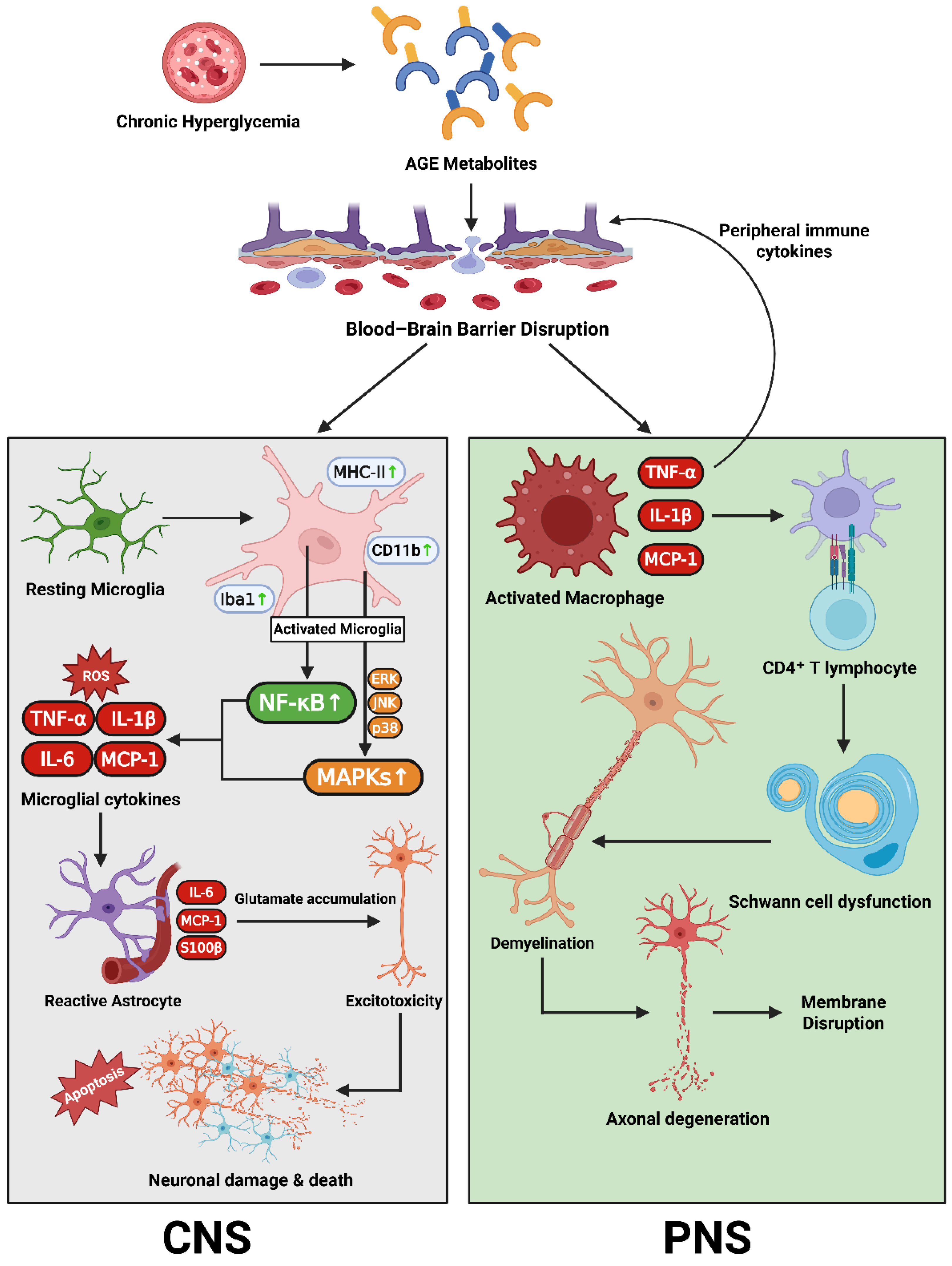

3.1.2. AGE–RAGE Signaling

3.1.3. Hexosamine Biosynthetic Pathway (HBP)

3.1.4. Protein Kinase C (PKC) Activation

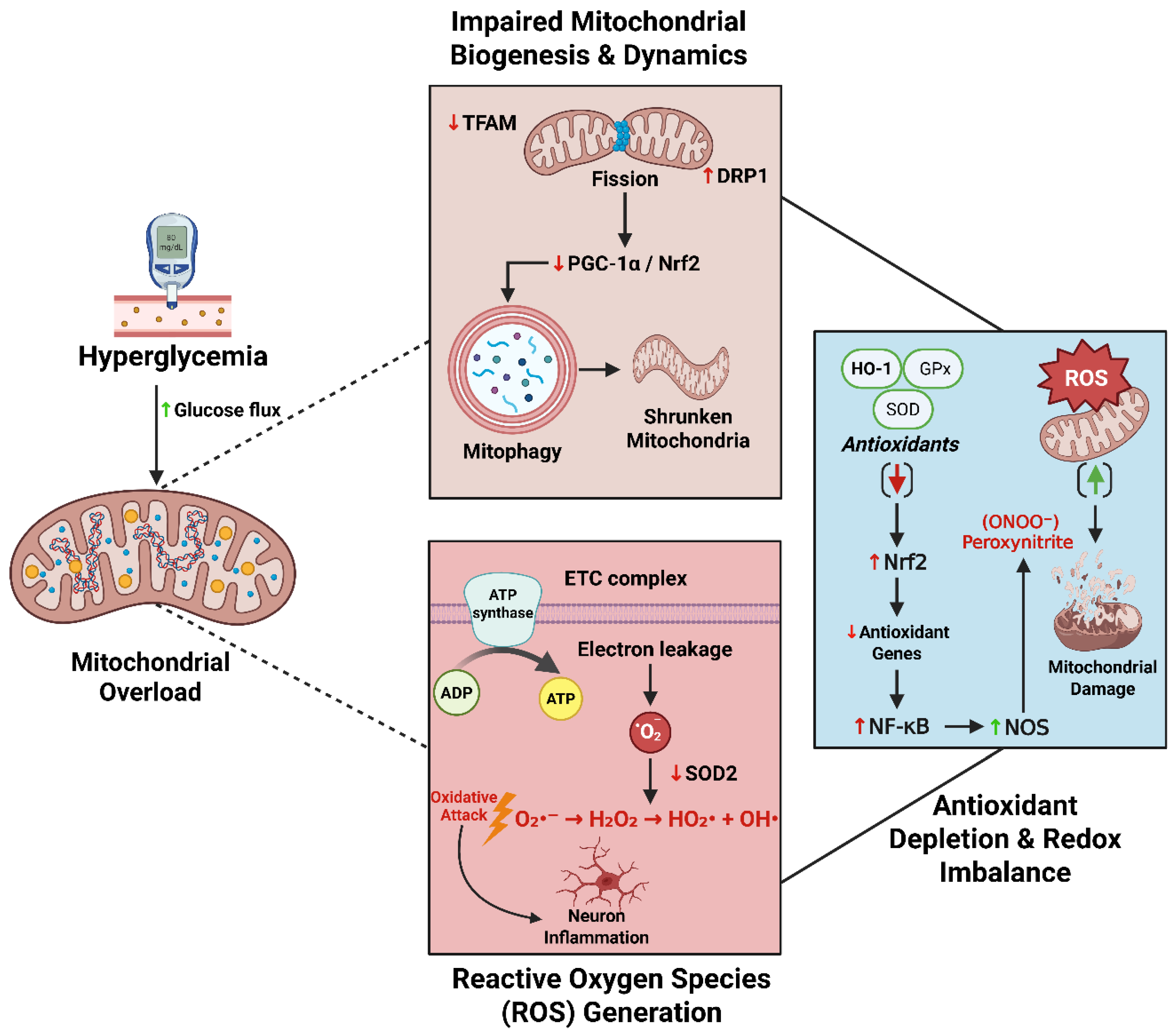

3.2. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Oxidative Stress

3.2.1. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Generation in Neurons and Glia

3.2.2. Antioxidant Depletion and Redox Imbalance

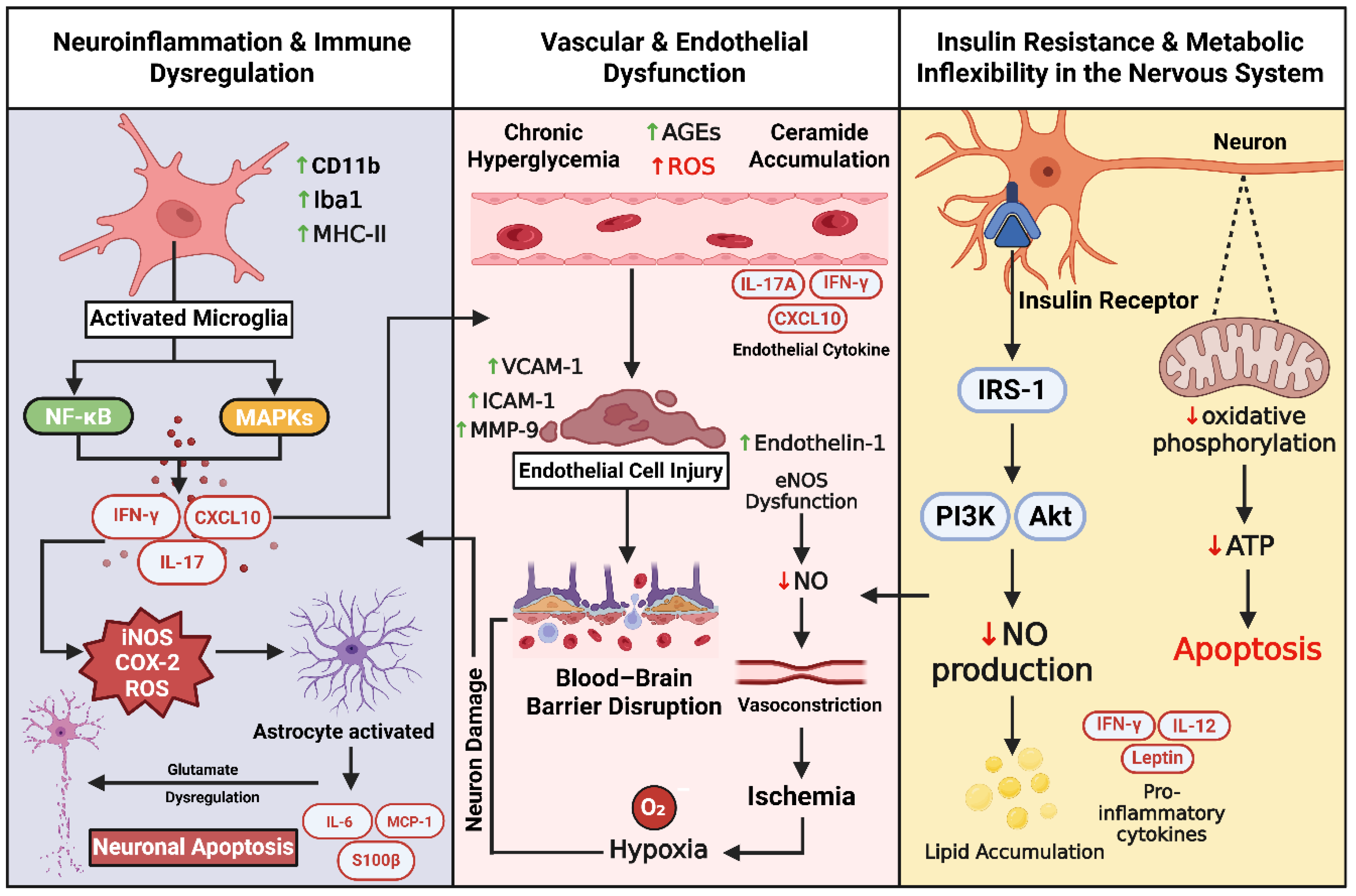

3.3. Neuroinflammation and Immune Dysregulation

3.4. Vascular and Endothelial Dysfunction

3.5. Insulin Resistance and Metabolic Inflexibility in the Nervous System

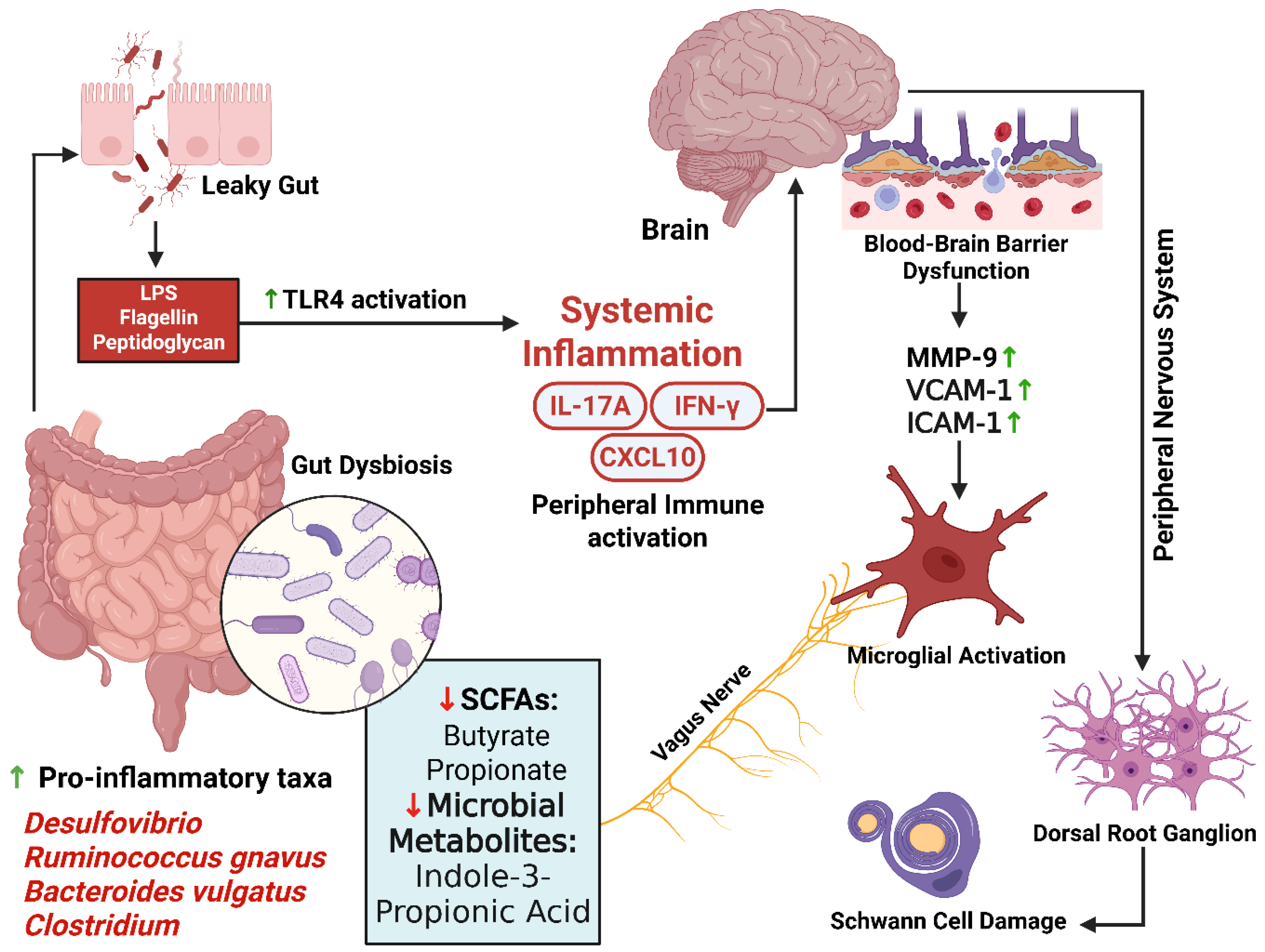

3.6. The Gut–Brain Axis in Diabetes-Induced Neuropathy

- Linking Mechanisms to Clinical Phenotypes in Diabetic Neurodegeneration

| Pathogenic Mechanism | Mechanism | Clinical Phenotypes | Key References |

| Polyol Pathway Overdrive | AR-mediated glucose-to-sorbitol conversion consuming NADPH, causing osmotic and redox stress (myo-inositol depletion; Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase impairment) | Length-dependent DPN; early small-fiber symptoms; slowed conduction | [64,65] |

| AGE–RAGE Axis | Tissue glycation, ECM stiffening, RAGE-mediated NF-κB/MAPK activation and oxidative stress | DPN (axonal/demyelination); painful DPN; cognitive decline | [250] |

| PKC Activation (via DAG) | Impaired eNOS/NO, elevated endothelin-1, VEGF-induced permeability | Ischemic DPN; microvascular dysfunction; autonomic neuropathy | [104] |

| Oxidative Stress & Mitochondrial Dysfunction | ETC superoxide generation; imbalance of mitochondrial fission/fusion; impaired biogenesis | Axonal transport impairment; PDN; cognitive slowing | [133] |

| Compromised Antioxidant Defenses | Nrf2 suppression, enzyme glycation (SOD, catalase, GPx), NADPH depletion | Accelerated DPN progression; CNS vulnerability | [155,251,252] |

| Neuroinflammation (Microglia/Astrocytes, Cytokines) | TLR4/RAGE induction; astrocytic GLT-1 downregulation; release of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 | Painful DPN; cognitive impairment; barrier dysfunction | [173] |

| Neurovascular Dysfunction (vasa nervorum & BBB) | Microangiopathy; reduced eNOS/mitigated NO; BBB tight-junction breakdown | DPN ischemia; cognitive decline | [191,204] |

| Insulin Resistance & Metabolic Inflexibility | IRS-1 Ser-phosphorylation; GLUT1/GLUT3 downregulation; lipotoxic DAG/ceramide accumulation | Cognitive decline; synaptic fatigue; DPN progression | [212] |

| Gut–Brain–Nerve Axis (Dysbiosis) | Loss of SCFA-producing species; LPS-TLR4 endotoxemia; impaired SCFA/indole/bile signaling; vagal dysfunction | PDN; cognitive symptoms; systemic inflammation | [236,242] |

| Small-Fiber Predominant Pathology | Early Aδ/C-fiber involvement; autonomic sudomotor fiber loss | Painful DPN; autonomic features | [18] |

| Large-Fiber Predominant Pathology | Axonal degeneration ± demyelination | Numbness, gait instability | [26] |

| CNS Cognitive/Affective Manifestations | BBB leak; insulin resistance; neuroinflammation | MCI; depression/anxiety | [54] |

| Autonomic Neuropathy (CAN & GI Dysmotility) | Autonomic fiber loss; impaired vagal signaling; enteric dysfunction | Orthostatic hypotension; gastroparesis | [253] |

4. Knowledge Gaps and Future Directions

Toward Precision-Based, Multi-Targeted Therapy

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Feldman, E.L. , et al., Diabetic neuropathy. Nat Rev Dis Primers, 2019. 5(1): p. 42.

- Pop-Busui, R.; Boulton, A.J.; Feldman, E.L.; Bril, V.; Freeman, R.; Malik, R.A.; Sosenko, J.M.; Ziegler, D. Diabetic Neuropathy: A Position Statement by the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2016, 40, 136–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zilliox, L.A. , et al., Diabetes and Cognitive Impairment. Curr Diab Rep, 2016. 16(9): p. 87.

- Kciuk, M.; Kruczkowska, W.; Gałęziewska, J.; Wanke, K.; Kałuzińska-Kołat, Ż.; Aleksandrowicz, M.; Kontek, R. Alzheimer’s Disease as Type 3 Diabetes: Understanding the Link and Implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giacco, F. and M. Brownlee, Oxidative stress and diabetic complications. Circ Res, 2010. 107(9): p. 1058-70.

- Talbot, K. , et al., Demonstrated brain insulin resistance in Alzheimer's disease patients is associated with IGF-1 resistance, IRS-1 dysregulation, and cognitive decline. J Clin Invest, 2012. 122(4): p. 1316-38.

- Zhao, F.; Siu, J.J.; Huang, W.; Askwith, C.; Cao, L. Insulin Modulates Excitatory Synaptic Transmission and Synaptic Plasticity in the Mouse Hippocampus. Neuroscience 2019, 411, 237–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cani, P.D. , et al., Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes, 2007. 56(7): p. 1761-72.

- Starr, J.M.; Wardlaw, J.; Ferguson, K.; MacLullich, A.; Deary, I.J.; Marshall, I. Increased blood-brain barrier permeability in type II diabetes demonstrated by gadolinium magnetic resonance imaging. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2003, 74, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, J.; Lawson, C.M.; Rentrup, K.F.G.; Kulkarni, P.; Ferris, C.F. Evaluating blood–brain barrier permeability in a rat model of type 2 diabetes. J. Transl. Med. 2020, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimu, S.J. and S. Islam, Gender Differences in Drug Addiction: Neurobiological, Social, and Psychological Perspectives in Women–A Systematic Review. Journal of Primeasia, 2025. 6(1): p. 1-13.

- Burgess, J.; Frank, B.; Marshall, A.; Khalil, R.S.; Ponirakis, G.; Petropoulos, I.N.; Cuthbertson, D.J.; Malik, R.A.; Alam, U. Early Detection of Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy: A Focus on Small Nerve Fibres. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Määttä, L.L.; Andersen, S.T.; Parkner, T.; Hviid, C.V.; Bjerg, L.; Kural, M.A.; Charles, M.; Søndergaard, E.; Kuhle, J.; Tankisi, H.; et al. Longitudinal Change in Serum Neurofilament Light Chain in Type 2 Diabetes and Early Diabetic Polyneuropathy: ADDITION-Denmark. Diabetes Care 2024, 47, 986–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridman, V.; Sillau, S.; Ritchie, A.; Bockhorst, J.; Coughlan, C.; Araya, P.; Espinosa, J.M.; Smith, K.; Lange, E.M.; Lange, L.A.; et al. Plasma neurofilament light chain concentrations are elevated in youth-onset type 2 diabetes and associated with neuropathy. J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst. 2023, 28, 460–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mielke, M.M.; Evans, J.K.; Neiberg, R.H.; Molina-Henry, D.P.; Marcovina, S.M.; Johnson, K.C.; Carmichael, O.T.; Rapp, S.R.; Sachs, B.C.; Ding, J.; et al. Alzheimer Disease Blood Biomarkers and Cognition Among Individuals With Diabetes and Overweight or Obesity. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e2458149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maalmi, H.; Strom, A.; Petrera, A.; Hauck, S.M.; Strassburger, K.; Kuss, O.; Zaharia, O.-P.; Bönhof, G.J.; Rathmann, W.; Trenkamp, S.; et al. Serum neurofilament light chain: a novel biomarker for early diabetic sensorimotor polyneuropathy. Diabetologia 2022, 66, 579–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karger, A.B.; Nasrallah, I.M.; Braffett, B.H.; Luchsinger, J.A.; Ryan, C.M.; Bebu, I.; Arends, V.; Habes, M.; Gubitosi-Klug, R.A.; Chaytor, N.; et al. Plasma Biomarkers of Brain Injury and Their Association With Brain MRI and Cognition in Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2024, 47, 1530–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, B.A.; Lovblom, L.E.; Lewis, E.J.; Bril, V.; Ferdousi, M.; Orszag, A.; Edwards, K.; Pritchard, N.; Russell, A.; Dehghani, C.; et al. Corneal Confocal Microscopy Predicts the Development of Diabetic Neuropathy: A Longitudinal Diagnostic Multinational Consortium Study. Diabetes Care 2021, 44, 2107–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gad, H.; Petropoulos, I.N.; Khan, A.; Ponirakis, G.; MacDonald, R.; Alam, U.; A Malik, R. Corneal confocal microscopy for the diagnosis of diabetic peripheral neuropathy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Diabetes Investig. 2021, 13, 134–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billeson, K.; Baldimtsi, E.; Wahlberg, J.; Whiss, P.A. Growth Differentiation Factor 15 and Matrix Metalloproteinase 3 in Plasma as Biomarkers for Neuropathy and Nephropathy in Type 1 Diabetes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schroeder, I.S. , Pluripotent Stem Cells for Cell Therapy. Methods Mol Biol, 2021. 2269: p. 25-33.

- Shrikanth, C.; Nandini, C. AMPK in microvascular complications of diabetes and the beneficial effects of AMPK activators from plants. Phytomedicine 2020, 73, 152808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zilliox, L.A.; Russell, J.W. Physical activity and dietary interventions in diabetic neuropathy: a systematic review. Clin. Auton. Res. 2019, 29, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kajiyama, S.; Kawamoto, M.; Shiraishi, S.; Gaus, S.; Matsunaga, A.; Suyama, H.; Yuge, O. Spinal orexin-1 receptors mediate anti-hyperalgesic effects of intrathecally-administered orexins in diabetic neuropathic pain model rats. Brain Res. 2005, 1044, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berti-Mattera, L.; Larkin, B.; Hourmouzis, Z.; Kern, T.; Siegel, R. NF-κB subunits are differentially distributed in cells of lumbar dorsal root ganglia in naïve and diabetic rats. Neurosci. Lett. 2011, 490, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyck, P.J.; Albers, J.W.; Andersen, H.; Arezzo, J.C.; Biessels, G.; Bril, V.; Feldman, E.L.; Litchy, W.J.; O'BRien, P.C.; Russell, J.W.; et al. Diabetic polyneuropathies: update on research definition, diagnostic criteria and estimation of severity. Diabetes/Metabolism Res. Rev. 2011, 27, 620–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H. , et al., Controlled chattering--a new 'cutting-edge' technology for nanofabrication. Nanotechnology, 2010. 21(35): p. 355302.

- Yaribeygi, H.; Ashrafizadeh, M.; Henney, N.C.; Sathyapalan, T.; Jamialahmadi, T.; Sahebkar, A. Neuromodulatory effects of anti-diabetes medications: A mechanistic review. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 152, 104611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, C.S.; Sharp, P. Tighter Accuracy Standards within Point-of-Care Blood Glucose Monitoring: How Six Commonly Used Systems Compare. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2012, 6, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouri, A.; Boulet, L.-P.; Kaplan, A.; Gupta, S. An evidence-based, point-of-care tool to guide completion of asthma action plans in practice. Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 49, 1602238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pozzi, M.; Rivolta, M.; Gelosa, M.; Capra, M.; Poggioli, G.; Bernasconi, A.; Lomuscio, G. Upper gastrointestinal involvement in diabetes mellitus: Study of esophagogastric function. Acta Diabetol. 1988, 25, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharucha, A.E., Y. C. Kudva, and D.O. Prichard, Diabetic Gastroparesis. Endocr Rev, 2019. 40(5): p. 1318-1352.

- Usai-Satta, P.; Bellini, M.; Morelli, O.; Geri, F.; Lai, M.; Bassotti, G. Gastroparesis: New insights into an old disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 26, 2333–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Gerichten, J. , et al., The [(13) C]octanoic acid breath test for gastric emptying quantification: A focus on nutrition and modeling. Lipids, 2022. 57(4-5): p. 205-219.

- Agochukwu-Mmonu, N.; Pop-Busui, R.; Wessells, H.; Sarma, A.V. Autonomic neuropathy and urologic complications in diabetes. Auton. Neurosci. 2020, 229, 102736–102736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, L.C.; Barnes, M.P.; Rodgers, H. Response to Letter by Munin et al Regarding Article, “Botulinum Toxin for the Upper Limb After Stroke (BoTULS) Trial: Effect on Impairment, Activity Limitation, and Pain”. Stroke 2011, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martonosi, Á.R.; Pázmány, P.; Kiss, S.; Dembrovszky, F.; Oštarijaš, E.; Szabó, L. Urodynamics in Early Diagnosis of Diabetic Bladder Dysfunction in Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Med Sci. Monit. 2022, 28, e937166–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Z.; Tang, Z.; He, C.; Tang, W. Diabetic cystopathy: A review 综述:糖尿病性膀胱病. J. Diabetes 2015, 7, 442–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, M.; Wandy, A.; Soraya, G.V.; Goysal, Y.; Lotisna, M.; Basri, M.I. Sudomotor dysfunction in diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN) and its testing modalities: A literature review. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; Bal, A.; Sandhir, R. Curcumin supplementation improves mitochondrial and behavioral deficits in experimental model of chronic epilepsy. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2014, 125, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, H.; Kihara, M.; Kosaka, S.; Ikeda, H.; Kawabata, K.; Tsutada, T.; Miki, T. Comparison of SSR and QSART in early diabetic neuropathy—the value of length-dependent pattern in QSART. Auton. Neurosci. 2001, 92, 72–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krieger, S.-M.; Reimann, M.; Haase, R.; Henkel, E.; Hanefeld, M.; Ziemssen, T. Sudomotor Testing of Diabetes Polyneuropathy. Front. Neurol. 2018, 9, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.S. , et al., Association of metabolic dysregulation with volumetric brain magnetic resonance imaging and cognitive markers of subclinical brain aging in middle-aged adults: the Framingham Offspring Study. Diabetes Care, 2011. 34(8): p. 1766-70.

- Launer, L.J.; E Miller, M.; Williamson, J.D.; Lazar, R.M.; Gerstein, H.C.; Murray, A.M.; Sullivan, M.; Horowitz, K.R.; Ding, J.; Marcovina, S.; et al. Effects of intensive glucose lowering on brain structure and function in people with type 2 diabetes (ACCORD MIND): a randomised open-label substudy. Lancet Neurol. 2011, 10, 969–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ott, A. , et al., Diabetes mellitus and the risk of dementia: The Rotterdam Study. Neurology, 1999. 53(9): p. 1937-42.

- Bahniwal, M.; Little, J.P.; Klegeris, A. High Glucose Enhances Neurotoxicity and Inflammatory Cytokine Secretion by Stimulated Human Astrocytes. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2017, 14, 731–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Fu, J.; Zhang, L.; Guo, M.; Zhuang, P.; Yin, Q.; Zhang, Y. Function and therapeutic value of astrocytes in diabetic cognitive impairment. Neurochem. Int. 2023, 169, 105591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steen, E. , et al., Impaired insulin and insulin-like growth factor expression and signaling mechanisms in Alzheimer's disease--is this type 3 diabetes? J Alzheimers Dis, 2005. 7(1): p. 63-80.

- Farris, W. , et al., Insulin-degrading enzyme regulates the levels of insulin, amyloid beta-protein, and the beta-amyloid precursor protein intracellular domain in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2003. 100(7): p. 4162-7.

- Willette, A.A.; Bendlin, B.B.; Starks, E.J.; Birdsill, A.C.; Johnson, S.C.; Christian, B.T.; Okonkwo, O.C.; La Rue, A.; Hermann, B.P.; Koscik, R.L.; et al. Association of Insulin Resistance With Cerebral Glucose Uptake in Late Middle–Aged Adults at Risk for Alzheimer Disease. JAMA Neurol. 2015, 72, 1013–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.J. , et al., The prevalence of comorbid depression in adults with diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care, 2001. 24(6): p. 1069-78.

- Mezuk, B.; Eaton, W.W.; Golden, S.H. Depression and Type 2 Diabetes Over the Lifespan: A Meta-Analysis. Diabetes Care 2009, 32, e57–e57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjeev, S.; Murthy, M.K.; Devi, M.S.; Khushboo, M.; Renthlei, Z.; Ibrahim, K.S.; Kumar, N.S.; Roy, V.K.; Gurusubramanian, G. Isolation, characterization, and therapeutic activity of bergenin from marlberry (Ardisia colorata Roxb.) leaf on diabetic testicular complications in Wistar albino rats. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 7082–7101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasreddine, Z.S.; Phillips, N.A.; Bédirian, V.; Charbonneau, S.; Whitehead, V.; Collin, I.; Cummings, J.L.; Chertkow, H. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A Brief Screening Tool For Mild Cognitive Impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2005, 53, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folstein, M.F., S. E. Folstein, and P.R. McHugh, "Mini-mental state". A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res, 1975. 12(3): p. 189-98.

- Kroenke, K., R. L. Spitzer, and J.B. Williams, The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med, 2001. 16(9): p. 606-13.

- Kawahito, S.; Kitahata, H.; Oshita, S. Problems associated with glucose toxicity: Role of hyperglycemia-induced oxidative stress. World J. Gastroenterol. 2009, 15, 4137–4142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calcutt, N.A. Diabetic neuropathy and neuropathic pain: a (con)fusion of pathogenic mechanisms? PAIN® 2020, 161, S65–S86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, D.R.; Tegeder, I.; Kuner, R.; Agarwal, N. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1α protects peripheral sensory neurons from diabetic peripheral neuropathy by suppressing accumulation of reactive oxygen species. J. Mol. Med. 2018, 96, 1395–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshitari, T. Advanced Glycation End-Products and Diabetic Neuropathy of the Retina. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, X.; Wu, J.; Jing, S.; Yan, L.-J. Hyperglycemic Stress and Carbon Stress in Diabetic Glucotoxicity. Aging Dis. 2016, 7, 90–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oates, P.J. Polyol pathway and diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2002, 50, 325–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malamas, M.S.; Hohman, T.C.; Millen, J. Novel Spirosuccinimide Aldose Reductase Inhibitors Derived from Isoquinoline-1,3-diones: 2-[(4-Bromo-2-fluorophenyl)methyl]-6-fluorospiro[isoquinoline-4(11H),3'-pyrrolidine]-1,2',3,5'(2H)-tetrone and Congeners. 1. J. Med. Chem. 1994, 37, 2043–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Kapoor, A.; Bhatnagar, A. Physiological and Pathological Roles of Aldose Reductase. Metabolites 2021, 11, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niimi, N.; Yako, H.; Takaku, S.; Chung, S.K.; Sango, K. Aldose Reductase and the Polyol Pathway in Schwann Cells: Old and New Problems. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Greene, D.; Chakrabarti, S.; A Lattimer, S.; A Sima, A. Role of sorbitol accumulation and myo-inositol depletion in paranodal swelling of large myelinated nerve fibers in the insulin-deficient spontaneously diabetic bio-breeding rat. Reversal by insulin replacement, an aldose reductase inhibitor, and myo-inositol. J. Clin. Investig. 1987, 79, 1479–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, D.A. and A.M. Mackway, Decreased myo-inositol content and Na+-K+-ATPase activity in superior cervical ganglion of STZ-diabetic rat and prevention by aldose reductase inhibition. Diabetes, 1986. 35(10): p. 1106-8.

- Lattimer, S.A.; Sima, A.A.; Greene, D.A. In vitro correction of impaired Na+-K+-ATPase in diabetic nerve by protein kinase C agonists. Am. J. Physiol. Metab. 1989, 256, E264–E269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillon, K.R.W.; Hawthorne, J.N.; Tomlinson, D.R. Myo-inositol and sorbitol metabolism in relation to peripheral nerve function in experimental diabetes in the rat: The effect of aldose reductase inhibition. Diabetologia 1983, 25, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sima, A.A. , et al., Supplemental myo-inositol prevents L-fucose-induced diabetic neuropathy. Diabetes, 1997. 46(2): p. 301-6.

- Goto, Y.; Hotta, N.; Shigeta, Y.; Sakamoto, N.; Kikkawa, R. Effects of an aldose reductase inhibitor, epalrestat, on diabetic neuropathy. Clinical benefit and indication for the drug assessed from the results of a placebo-controlled double-blind study. Biomed. Pharmacother. 1995, 49, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, T. , et al., Effects of epalrestat, an aldose reductase inhibitor, on diabetic peripheral neuropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes, in relation to suppression of N(ɛ)-carboxymethyl lysine. J Diabetes Complications, 2010. 24(6): p. 424-32.

- Sekiguchi, K.; Kohara, N.; Baba, M.; Komori, T.; Naito, Y.; Imai, T.; Satoh, J.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Hamatani, T. ; the Ranirestat Group Aldose reductase inhibitor ranirestat significantly improves nerve conduction velocity in diabetic polyneuropathy: A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study in Japan. J. Diabetes Investig. 2018, 10, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabbay, K.H. , Aldose reductase inhibition in the treatment of diabetic neuropathy: where are we in 2004? Curr Diab Rep, 2004. 4(6): p. 405-8.

- Twarda-Clapa, A.; Olczak, A.; Białkowska, A.M.; Koziołkiewicz, M. Advanced Glycation End-Products (AGEs): Formation, Chemistry, Classification, Receptors, and Diseases Related to AGEs. Cells 2022, 11, 1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prommer, E.E. Methadone Isomers and Their Role in Pain Management. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2009, 26, 149–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The CRASH trial protocol (Corticosteroid randomisation after significant head injury) [ISRCTN74459797]. BMC Emerg Med, 2001. 1(1): p. 1.

- Toth, C.; Rong, L.L.; Yang, C.; Martinez, J.; Song, F.; Ramji, N.; Brussee, V.; Liu, W.; Durand, J.; Nguyen, M.D.; et al. Receptor for Advanced Glycation End Products (RAGEs) and Experimental Diabetic Neuropathy. Diabetes 2008, 57, 1002–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Win, M.T.T.; Yamamoto, Y.; Munesue, S.; Saito, H.; Han, D.; Motoyoshi, S.; Kamal, T.; Ohara, T.; Watanabe, T.; Yamamoto, H. Regulation of RAGE for Attenuating Progression of Diabetic Vascular Complications. Exp. Diabetes Res. 2011, 2012, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plieth, C. Peroxide-Induced Liberation of Iron from Heme Switches Catalysis during Luminol Reaction and Causes Loss of Light and Heterodyning of Luminescence Kinetics. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 3268–3279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coughlan, M.T.; Thorburn, D.R.; Penfold, S.A.; Laskowski, A.; Harcourt, B.E.; Sourris, K.C.; Tan, A.L.; Fukami, K.; Thallas-Bonke, V.; Nawroth, P.P.; et al. RAGE-Induced Cytosolic ROS Promote Mitochondrial Superoxide Generation in Diabetes. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2009, 20, 742–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talabi, O.O.; Dorfi, A.E.; O’nEil, G.D.; Esposito, D.V. Membraneless electrolyzers for the simultaneous production of acid and base. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 8006–8009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMarco, S.J.; Strehler, E.E. Plasma Membrane Ca2+-ATPase Isoforms 2b and 4b Interact Promiscuously and Selectively with Members of the Membrane-associated Guanylate Kinase Family of PDZ (PSD95/Dlg/ZO-1) Domain-containing Proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 21594–21600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, E. , Frankincense: systematic review. Bmj, 2008. 337: p. a2813.

- Shimizu, F.; Sano, Y.; Haruki, H.; Kanda, T. Advanced glycation end-products induce basement membrane hypertrophy in endoneurial microvessels and disrupt the blood–nerve barrier by stimulating the release of TGF-β and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) by pericytes. Diabetologia 2011, 54, 1517–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, F.; Sano, Y.; Tominaga, O.; Maeda, T.; Abe, M.-A.; Kanda, T. Advanced glycation end-products disrupt the blood–brain barrier by stimulating the release of transforming growth factor–β by pericytes and vascular endothelial growth factor and matrix metalloproteinase–2 by endothelial cells in vitro. Neurobiol. Aging 2013, 34, 1902–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenk, M.R.; Lucast, L.; Di Paolo, G.; Romanelli, A.J.; Suchy, S.F.; Nussbaum, R.L.; Cline, G.W.; I Shulman, G.; McMurray, W.; De Camilli, P. Phosphoinositide profiling in complex lipid mixtures using electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003, 21, 813–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juranek, J.K.; Geddis, M.S.; Song, F.; Zhang, J.; Garcia, J.; Rosario, R.; Yan, S.F.; Brannagan, T.H.; Schmidt, A.M. RAGE Deficiency Improves Postinjury Sciatic Nerve Regeneration in Type 1 Diabetic Mice. Diabetes 2013, 62, 931–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, M.; Crego, A.; Rodrigues, R.; Almeida-Antunes, N.; López-Caneda, E. Effects of the COVID-19 Mitigation Measures on Alcohol Consumption and Binge Drinking in College Students: A Longitudinal Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 9822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, M. , et al., Low peripheral nerve conduction velocities and amplitudes are strongly related to diabetic microvascular complications in type 1 diabetes: the EURODIAB Prospective Complications Study. Diabetes Care, 2010. 33(12): p. 2648-53.

- Yaffe, K. , et al., Advanced glycation end product level, diabetes, and accelerated cognitive aging. Neurology, 2011. 77(14): p. 1351-6.

- Takahashi, S.; Kurimura, Y.; Hashimoto, J.; Uehara, T.; Hiyama, Y.; Tsukamoto, T.; Iwasawa, A.; Nishimura, M.; Sunaoshi, K.; Takeda, K.; et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility and penicillin-binding protein 1 and 2 mutations in Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolated from male urethritis in Sapporo, Japan. J. Infect. Chemother. 2013, 19, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akella, N.M.; Ciraku, L.; Reginato, M.J. Fueling the fire: emerging role of the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway in cancer. BMC Biol. 2019, 17, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Li, X.; He, L.; Zhu, S.; Lai, S.; Zhang, X.; Huang, Z.; Yu, B.; Cui, C.; Wang, Q. Empagliflozin improves renal ischemia–reperfusion injury by reducing inflammation and enhancing mitochondrial fusion through AMPK–OPA1 pathway promotion. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 2023, 28, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Hart, G.W. ProteinO-GlcNAcylation in diabetes and diabetic complications. Expert Rev. Proteom. 2013, 10, 365–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, K.; Alekseev, O.; Qi, X.; Cho, W.; Azizkhan-Clifford, J. O-GlcNAc Modification of Transcription Factor Sp1 Mediates Hyperglycemia-Induced VEGF-A Upregulation in Retinal Cells. Investig. Opthalmology Vis. Sci. 2014, 55, 7862–7873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.H.; Park, S.Y.; Nam, H.W.; Kim, D.H.; Kang, J.G.; Kang, E.S.; Kim, Y.S.; Lee, H.C.; Kim, K.S.; Cho, J.W. NFκB activation is associated with its O -GlcNAcylation state under hyperglycemic conditions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2008, 105, 17345–17350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tallent, M.K.; Varghis, N.; Skorobogatko, Y.; Hernandez-Cuebas, L.; Whelan, K.; Vocadlo, D.J.; Vosseller, K. In Vivo Modulation of O-GlcNAc Levels Regulates Hippocampal Synaptic Plasticity through Interplay with Phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, E.W.; Wang, K.; Nelson, A.R.; Bredemann, T.M.; Fraser, K.B.; Clinton, S.M.; Puckett, R.; Marchase, R.B.; Chatham, J.C.; McMahon, L.L. O-GlcNAcylation of AMPA Receptor GluA2 Is Associated with a Novel Form of Long-Term Depression at Hippocampal Synapses. J. Neurosci. 2013, 34, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jóźwiak, P.; Oracz, J.; Dziedzic, A.; Szelenberger, R.; Żyżelewicz, D.; Bijak, M.; Krześlak, A. Increased O-GlcNAcylation by Upregulation of Mitochondrial O-GlcNAc Transferase (mOGT) Inhibits the Activity of Respiratory Chain Complexes and Controls Cellular Bioenergetics. Cancers 2024, 16, 1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hui, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Kuang, L.; Xu, J.; Hao, Y.; Cao, J.; Zheng, T. O-GlcNAcylation of circadian clock protein Bmal1 impairs cognitive function in diabetic mice. EMBO J. 2024, 43, 5667–5689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geraldes, P.; King, G.L. Activation of Protein Kinase C Isoforms and Its Impact on Diabetic Complications. Circ. Res. 2010, 106, 1319–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farb, M.G.; Ganley-Leal, L.; Mott, M.; Liang, Y.; Ercan, B.; Widlansky, M.E.; Bigornia, S.J.; Fiscale, A.J.; Apovian, C.M.; Carmine, B.; et al. Arteriolar function in visceral adipose tissue is impaired in human obesity. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2012, 32, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasevcimen, N.; King, G. The role of protein kinase C activation and the vascular complications of diabetes. Pharmacol. Res. 2007, 55, 498–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabit, C.E.; Shenouda, S.M.; Holbrook, M.; Fetterman, J.L.; Kiani, S.; Frame, A.A.; Kluge, M.A.; Held, A.; Dohadwala, M.M.; Gokce, N.; et al. Protein Kinase C-β Contributes to Impaired Endothelial Insulin Signaling in Humans With Diabetes Mellitus. Circulation 2013, 127, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naruse, K.; Rask-Madsen, C.; Takahara, N.; Ha, S.-W.; Suzuma, K.; Way, K.J.; Jacobs, J.R.; Clermont, A.C.; Ueki, K.; Ohshiro, Y.; et al. Activation of Vascular Protein Kinase C-β Inhibits Akt-Dependent Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase Function in Obesity-Associated Insulin Resistance. Diabetes 2006, 55, 691–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.Y.; Takahara, N.; Gabriele, A.; Chou, E.; Naruse, K.; Suzuma, K.; Yamauchi, T.; Ha, S.W.; Meier, M.; Rhodes, C.J.; et al. Induction of endothelin-1 expression by glucose: an effect of protein kinase C activation. Diabetes 2000, 49, 1239–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harhaj, N.S.; Felinski, E.A.; Wolpert, E.B.; Sundstrom, J.M.; Gardner, T.W.; Antonetti, D.A. VEGF Activation of Protein Kinase C Stimulates Occludin Phosphorylation and Contributes to Endothelial Permeability. Investig. Opthalmology Vis. Sci. 2006, 47, 5106–5115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, L.B.; Milne, L.; Nelson, N.; Eddie, S.; Brown, P.; Atanassova, N.; O'BRyan, M.K.; O'DOnnell, L.; Rhodes, D.; Wells, S.; et al. KATNAL1 Regulation of Sertoli Cell Microtubule Dynamics Is Essential for Spermiogenesis and Male Fertility. PLOS Genet. 2012, 8, e1002697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleegal, M.A.; Hom, S.; Borg, L.K.; Davis, T.P. Activation of PKC modulates blood-brain barrier endothelial cell permeability changes induced by hypoxia and posthypoxic reoxygenation. Am. J. Physiol. Circ. Physiol. 2005, 289, H2012–H2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richner, M.; Ferreira, N.; Dudele, A.; Jensen, T.S.; Vaegter, C.B.; Gonçalves, N.P. Functional and Structural Changes of the Blood-Nerve-Barrier in Diabetic Neuropathy. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 12, 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeshita, Y.; Sato, R.; Kanda, T. Blood–Nerve Barrier (BNB) Pathology in Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy and In Vitro Human BNB Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 22, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimu, S.J.; Patil, S.M.; Dadzie, E.; Tesfaye, T.; Alag, P.; Więckiewicz, G. Exploring Health Informatics in the Battle against Drug Addiction: Digital Solutions for the Rising Concern. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanmugam, N. , et al., High glucose-induced expression of proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine genes in monocytic cells. Diabetes, 2003. 52(5): p. 1256-64.

- Chen, S. , et al., High glucose-induced, endothelin-dependent fibronectin synthesis is mediated via NF-kappa B and AP-1. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol, 2003. 284(2): p. C263-72.

- Venkatesan, B.; Valente, A.J.; Das, N.A.; Carpenter, A.J.; Yoshida, T.; Delafontaine, J.-L.; Siebenlist, U.; Chandrasekar, B. CIKS (Act1 or TRAF3IP2) mediates high glucose-induced endothelial dysfunction. Cell. Signal. 2013, 25, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieper, G.M. and H. Riaz ul, Activation of nuclear factor-kappaB in cultured endothelial cells by increased glucose concentration: prevention by calphostin C. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol, 1997. 30(4): p. 528-32.

- Ozsarac, N.; Weible, M.; Reynolds, A.J.; Hendry, I.A. Activation of protein kinase C inhibits retrograde transport of neurotrophins in mice. J. Neurosci. Res. 2003, 72, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.-L.; Zhu, H.; Yu, W.-J.; Le, Y.; Wang, W.-J.; Li, F.; Gui, T.; Wang, Y.; Shi, W.-D.; Fan, X.-Q. High glucose levels increase the expression of neurotrophic factors associated with p-p42/p44 MAPK in Schwann cells in vitro. Mol. Med. Rep. 2012, 6, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naruse, K. Schwann Cells as Crucial Players in Diabetic Neuropathy. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, L.; Qu, M.; Zhang, M.; Cheng, P.; Guo, M.; Selvarajah, D.; Tesfaye, S.; Wu, J. High glucose mediates diabetic peripheral neuropathy by inducing Schwann cells apoptosis through the Dgkh/PKC-α signaling pathway. Acta Diabetol. 2025, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, N.N.; Sheetz, M.; Price, K.; Comiskey, L.; Amrutia, S.; Iqbal, N.; Mohler, E.R.; Reilly, M.P. Selective PKC Beta Inhibition with Ruboxistaurin and Endothelial Function in Type-2 Diabetes Mellitus. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2008, 23, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckman, J.A.; Goldfine, A.B.; Gordon, M.B.; Garrett, L.A.; Creager, M.A. Inhibition of Protein Kinase Cβ Prevents Impaired Endothelium-Dependent Vasodilation Caused by Hyperglycemia in Humans. Circ. Res. 2002, 90, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casellini, C.M. , et al., A 6-month, randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled study evaluating the effects of the protein kinase C-beta inhibitor ruboxistaurin on skin microvascular blood flow and other measures of diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Diabetes Care, 2007. 30(4): p. 896-902.

- Vinik, A.I. , et al., Treatment of symptomatic diabetic peripheral neuropathy with the protein kinase C beta-inhibitor ruboxistaurin mesylate during a 1-year, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial. Clin Ther, 2005. 27(8): p. 1164-80.

- Baird, A.A. and J.A. Fugelsang, The emergence of consequential thought: evidence from neuroscience. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci, 2004. 359(1451): p. 1797-804.

- Clemente-Suárez, V.J.; Redondo-Flórez, L.; Beltrán-Velasco, A.I.; Ramos-Campo, D.J.; Belinchón-Demiguel, P.; Martinez-Guardado, I.; Dalamitros, A.A.; Yáñez-Sepúlveda, R.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F. Mitochondria and Brain Disease: A Comprehensive Review of Pathological Mechanisms and Therapeutic Opportunities. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, U.C.; Bhol, N.K.; Swain, S.K.; Samal, R.R.; Nayak, P.K.; Raina, V.; Panda, S.K.; Kerry, R.G.; Duttaroy, A.K.; Jena, A.B. Oxidative stress and inflammation in the pathogenesis of neurological disorders: Mechanisms and implications. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2024, 15, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernyhough, P.; Chowdhury, S.K.R.; E Schmidt, R. Mitochondrial stress and the pathogenesis of diabetic neuropathy. Expert Rev. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 5, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, T.; Edelstein, D.; Du, X.L.; Yamagishi, S.-I.; Matsumura, T.; Kaneda, Y.; Yorek, M.A.; Beebe, D.J.; Oates, P.J.; Hammes, H.-P.; et al. Normalizing mitochondrial superoxide production blocks three pathways of hyperglycaemic damage. Nature 2000, 404, 787–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, X.-L.; Edelstein, D.; Rossetti, L.; Fantus, I.G.; Goldberg, H.; Ziyadeh, F.; Wu, J.; Brownlee, M. Hyperglycemia-induced mitochondrial superoxide overproduction activates the hexosamine pathway and induces plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 expression by increasing Sp1 glycosylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 12222–12226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.-Y.; Tang, L.-Q. Roles of the NLRP3 inflammasome in the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy. Pharmacol. Res. 2016, 114, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sifuentes-Franco, S. , et al., The Role of Oxidative Stress, Mitochondrial Function, and Autophagy in Diabetic Polyneuropathy. J Diabetes Res, 2017. 2017: p. 1673081.

- Eckersley, L. Role of the Schwann cell in diabetic neuropathy. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2002, 50, 293–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S. , et al., New insights into the role of mitochondrial dynamics in oxidative stress-induced diseases. Biomed Pharmacother, 2024. 178: p. 117084.

- Rius-Pérez, S. , et al., PGC-1α, Inflammation, and Oxidative Stress: An Integrative View in Metabolism. Oxid Med Cell Longev, 2020. 2020: p. 1452696.

- Vargas-Mendoza, N.; Angeles-Valencia, M.; Morales-González, Á.; Madrigal-Santillán, E.O.; Morales-Martínez, M.; Madrigal-Bujaidar, E.; Álvarez-González, I.; Gutiérrez-Salinas, J.; Esquivel-Chirino, C.; Chamorro-Cevallos, G.; et al. Oxidative Stress, Mitochondrial Function and Adaptation to Exercise: New Perspectives in Nutrition. Life 2021, 11, 1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhao, H.; Lin, S.; Lv, Y.; Lin, Y.; Liu, Y.; Peng, R.; Jin, H. New therapeutic directions in type II diabetes and its complications: mitochondrial dynamics. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1230168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Qin, Y.; Liu, B.; Gao, M.; Li, A.; Li, X.; Gong, G. PGC-1α-Mediated Mitochondrial Quality Control: Molecular Mechanisms and Implications for Heart Failure. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 871357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Chen, X.; Yu, B.; Shen, L.; Zhang, X. Delayed Intracerebral Hemorrhage Secondary to Ventriculoperitoneal Shunt: A Retrospective Study. World Neurosurg. 2017, 107, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gureev, A.P.; Shaforostova, E.A.; Popov, V.N. Regulation of Mitochondrial Biogenesis as a Way for Active Longevity: Interaction Between the Nrf2 and PGC-1α Signaling Pathways. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.-Y.; Zhu, L.; Bao, X.; Xie, T.-H.; Cai, J.; Zou, J.; Wang, W.; Gu, S.; Li, Y.; Li, H.-Y.; et al. Inhibition of Drp1 ameliorates diabetic retinopathy by regulating mitochondrial homeostasis. Exp. Eye Res. 2022, 220, 109095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Yu, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Tian, Y.; Cai, J.; Wei, M.; Lyu, Y.; Yang, D.; Shen, S.; et al. SIRT3 alleviates painful diabetic neuropathy by mediating the FoxO3a-PINK1-Parkin signaling pathway to activate mitophagy. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2024, 30, e14703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmpilas, N.; Fang, E.F.; Palikaras, K. Mitophagy and Neuroinflammation: A Compelling Interplay. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2023, 21, 1477–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figley, M.D.; Thomas, A.; Gitler, A.D. Evaluating noncoding nucleotide repeat expansions in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurobiol. Aging 2014, 35, 936.e1–936.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, A.R.; Siraj, A.K.; Ahmed, M.; Bu, R.; Pratheeshkumar, P.; Alrashed, A.M.; Qadri, Z.; Ajarim, D.; Al-Dayel, F.; Beg, S.; et al. XIAP over-expression is an independent poor prognostic marker in Middle Eastern breast cancer and can be targeted to induce efficient apoptosis. BMC Cancer 2017, 17, 640–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teleanu, D.M. , et al., An Overview of Oxidative Stress, Neuroinflammation, and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int J Mol Sci, 2022. 23(11).

- Averill-Bates, D.A. , The antioxidant glutathione. Vitam Horm, 2023. 121: p. 109-141.

- Krishnamurthy, H.K.; Pereira, M.; Rajavelu, I.; Jayaraman, V.; Krishna, K.; Wang, T.; Bei, K.; Rajasekaran, J.J. Oxidative stress: fundamentals and advances in quantification techniques. Front. Chem. 2024, 12, 1470458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, J.K. The Role of Aldose Reductase in Polyol Pathway: An Emerging Pharmacological Target in Diabetic Complications and Associated Morbidities. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2024, 25, 1073–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedeek, M.; Callera, G.; Montezano, A.; Gutsol, A.; Heitz, F.; Szyndralewiez, C.; Page, P.; Kennedy, C.R.J.; Burns, K.D.; Touyz, R.M.; et al. Critical role of Nox4-based NADPH oxidase in glucose-induced oxidative stress in the kidney: implications in type 2 diabetic nephropathy. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2010, 299, F1348–F1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, D.; Velagapudi, R.; Gao, Y.; Hong, J.-S.; Zhou, H.; Gao, H.-M. Activation of neuronal NADPH oxidase NOX2 promotes inflammatory neurodegeneration. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2023, 200, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Li, K.; Chen, Y.; Xie, J.; Wu, C.; Cui, C.; Deng, B. Oxidative Stress in Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy: Pathway and Mechanism-Based Treatment. Mol. Neurobiol. 2023, 60, 4574–4594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez, M.M.; Folgado, J.; Tormo, C.; Artero, A.; Ascaso, M.; Martinez-Hervás, S.; Chaves, F.J.; Ascaso, J.F.; Real, J.T. Altered glutathione system is associated with the presence of distal symmetric peripheral polyneuropathy in type 2 diabetic subjects. J. Diabetes its Complicat. 2015, 29, 923–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neagu, M. , et al., Diabetic neuropathy: A NRF2 disease? J Diabetes, 2024. 16(9): p. e13524.

- Kumar, A.; Mittal, R. Nrf2: a potential therapeutic target for diabetic neuropathy. Inflammopharmacology 2017, 25, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Oost, J. , et al., The ferredoxin-dependent conversion of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate in the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus represents a novel site of glycolytic regulation. J Biol Chem, 1998. 273(43): p. 28149-54.

- Yan, H.; Harding, J.J. Glycation-induced inactivation and loss of antigenicity of catalase and superoxide dismutase. Biochem. J. 1997, 328, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polykretis, P.; Luchinat, E.; Boscaro, F.; Banci, L. Methylglyoxal interaction with superoxide dismutase 1. Redox Biol. 2020, 30, 101421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najjar, F.M.; Taghavi, F.; Ghadari, R.; Sheibani, N.; Moosavi-Movahedi, A.A. Destructive effect of non-enzymatic glycation on catalase and remediation via curcumin. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2017, 630, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Begum, M.; Choubey, M.; Tirumalasetty, M.B.; Arbee, S.; Sadik, S.; Mohib, M.M.; Srivastava, S.; Minhaz, N.; Alam, R.; Mohiuddin, M.S. Exploring the Molecular Link Between Diabetes and Erectile Dysfunction Through Single-Cell Transcriptome Analysis. Genes 2024, 15, 1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L. , et al., Hyperglycemia-induced apoptosis in mouse myocardium: mitochondrial cytochrome C-mediated caspase-3 activation pathway. Diabetes, 2002. 51(6): p. 1938-48.

- Kowalczyk, P.; Sulejczak, D.; Kleczkowska, P.; Bukowska-Ośko, I.; Kucia, M.; Popiel, M.; Wietrak, E.; Kramkowski, K.; Wrzosek, K.; Kaczyńska, K. Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress—A Causative Factor and Therapeutic Target in Many Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norat, P.; Soldozy, S.; Sokolowski, J.D.; Gorick, C.M.; Kumar, J.S.; Chae, Y.; Yağmurlu, K.; Prada, F.; Walker, M.; Levitt, M.R.; et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in neurological disorders: Exploring mitochondrial transplantation. npj Regen. Med. 2020, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Pang, Y.; Fan, X. Mitochondria in oxidative stress, inflammation and aging: from mechanisms to therapeutic advances. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ametov, A.S. , et al., The sensory symptoms of diabetic polyneuropathy are improved with alpha-lipoic acid: the SYDNEY trial. Diabetes Care, 2003. 26(3): p. 770-6.

- Ziegler, D. , et al., Oral treatment with alpha-lipoic acid improves symptomatic diabetic polyneuropathy: the SYDNEY 2 trial. Diabetes Care, 2006. 29(11): p. 2365-70.

- Han, T. , et al., A systematic review and meta-analysis of α-lipoic acid in the treatment of diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Eur J Endocrinol, 2012. 167(4): p. 465-71.

- Heidari, N.; Sajedi, F.; Mohammadi, Y.; Mirjalili, M.; Mehrpooya, M. Ameliorative Effects Of N-Acetylcysteine As Adjunct Therapy On Symptoms Of Painful Diabetic Neuropathy. J. Pain Res. 2019, ume 12, 3147–3159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhrabadi, M.A.; Ghotrom, A.Z.; Mozaffari-Khosravi, H.; Nodoushan, H.H.; Nadjarzadeh, A. Effect of Coenzyme Q10 on Oxidative Stress, Glycemic Control and Inflammation in Diabetic Neuropathy: A Double Blind Randomized Clinical Trial. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 2014, 84, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celen, M.C.; Tuncer, S.; Akkoca, A.; Dalkilic, N. Enhancing diabetic rat peripheral nerve conduction velocity parameters through the potent effects of MitoTEMPO. Heliyon 2024, 10, e41045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schemmel, K.E.; Padiyara, R.S.; D'SOuza, J.J. Aldose reductase inhibitors in the treatment of diabetic peripheral neuropathy: a review. J. Diabetes its Complicat. 2010, 24, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas-Soria, M.; García-Alloza, M.; Corraliza-Gómez, M. Effects of diabetes on microglial physiology: a systematic review of in vitro, preclinical and clinical studies. J. Neuroinflammation 2023, 20, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Kraiem, A.; Sauer, R.-S.; Norwig, C.; Popp, M.; Bettenhausen, A.-L.; Atalla, M.S.; Brack, A.; Blum, R.; Doppler, K.; Rittner, H.L. Selective blood-nerve barrier leakiness with claudin-1 and vessel-associated macrophage loss in diabetic polyneuropathy. J. Mol. Med. 2021, 99, 1237–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, E.; Judd, R.; Hoe, L.; Dennis, J.; Posner, P. Effects of diabetes mellitus on astrocyte GFAP and glutamate transporters in the CNS. Glia 2004, 48, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, E.S.; Dennis, J.C.; Braden, T.D.; Judd, R.L.; Posner, P. Insulin treatment prevents diabetes-induced alterations in astrocyte glutamate uptake and GFAP content in rats at 4 and 8 weeks of diabetes duration. Brain Res. 2010, 1306, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, X.; Wan, J.; Wu, W.; Ma, L.; Chen, C.; Dong, W.; Liu, Y.; Jin, C.; Sun, A.; Zhou, Y.; et al. GLT-1 downregulation in hippocampal astrocytes induced by type 2 diabetes contributes to postoperative cognitive dysfunction in adult mice. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2024, 30, e70024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biswas, J.; Pijewski, R.S.; Makol, R.; Miramontes, T.G.; Thompson, B.L.; Kresic, L.C.; Burghard, A.L.; Oliver, D.L.; Martinelli, D.C.; Shore, S.E. C1ql1 is expressed in adult outer hair cells of the cochlea in a tonotopic gradient. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0251412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raka, M.A. , et al., Inhibitory role of resveratrol in the development of profibrogenesis and fibrosis mechanisms. Immunology, Endocrine & Metabolic Agents in Medicinal Chemistry (Formerly Current Medicinal Chemistry-Immunology, Endocrine and Metabolic Agents), 2018. 18(1): p. 80-104.

- Younger, D.S. , et al., Diabetic peripheral neuropathy: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of sural nerve biopsies. Muscle Nerve, 1996. 19(6): p. 722-7.

- O'Brien, J.A.; McGuire, H.M.; Shinko, D.; Groth, B.F.d.S.; Russo, M.A.; Bailey, D.; Santarelli, D.M.; Wynne, K.; Austin, P.J. T lymphocyte and monocyte subsets are dysregulated in type 1 diabetes patients with peripheral neuropathic pain. Brain, Behav. Immun. - Heal. 2021, 15, 100283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dogrul, A.; Gul, H.; Yesilyurt, O.; Ulas, U.H.; Yildiz, O. Systemic and spinal administration of etanercept, a tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitor, blocks tactile allodynia in diabetic mice. Acta Diabetol. 2010, 48, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Chen, Y.; Nadeem, L.; Xu, G. Beneficial effect of TNF-α inhibition on diabetic peripheral neuropathy. J. Neuroinflammation 2013, 10, 836–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.-J.; Li, J.-M.; Zhang, T.; Cao, Z.-Y.; Hu, T.; Zhong, S.-Y.; Xu, Z.-Y.; Gong, H.; Jiang, C.-L. Microglial NLRP3 inflammasome activation mediates diabetes-induced depression-like behavior via triggering neuroinflammation. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacology Biol. Psychiatry 2023, 126, 110796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Mamun, A.; Shao, C.; Geng, P.; Wang, S.; Xiao, J. Pyroptosis in Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy and its Therapeutic Regulation. J. Inflamm. Res. 2024, ume 17, 3839–3864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, K.; Akash, M.S.H.; Liaqat, A.; Kamal, S.; Qadir, M.I.; Rasul, A. Role of Interleukin-6 in Development of Insulin Resistance and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 2017, 27, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callanan, A.; Davis, N.; McGloughlin, T.; Walsh, M. The effects of stent interaction on porcine urinary bladder matrix employed as stent-graft materials. J. Biomech. 2014, 47, 1885–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.-S.; Yang, Y.-J.; Zhang, Y.-Z.; Huang, W.; Li, Z.-S. Minocycline attenuates pain by inhibiting spinal microglia activation in diabetic rats. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 12, 2677–2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Hiam-Galvez, K.J.; Mowery, C.T.; Herold, K.C.; Gitelman, S.E.; Esensten, J.H.; Liu, W.; Lares, A.P.; Leinbach, A.S.; Lee, M.; et al. The effect of low-dose IL-2 and Treg adoptive cell therapy in patients with type 1 diabetes. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austin, P.J.; Moalem-Taylor, G. The neuro-immune balance in neuropathic pain: Involvement of inflammatory immune cells, immune-like glial cells and cytokines. J. Neuroimmunol. 2010, 229, 26–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, N.E.; Eaton, S.E.M.; Cotter, M.A.; Tesfaye, S. Vascular factors and metabolic interactions in the pathogenesis of diabetic neuropathy. Diabetologia 2001, 44, 1973–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasuda, H.; Dyck, P.J. Abnormalities of endoneurial microvessels and sural nerve pathology in diabetic neuropathy. Neurology 1987, 37, 20–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, H.C.; Rosoff, J.; Myers, R.R. Microangiopathy in human diabetic neuropathy. Acta Neuropathol. 1985, 68, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sima, A.A. , et al., Endoneurial microvessels in human diabetic neuropathy. Endothelial cell dysjunction and lack of treatment effect by aldose reductase inhibitor. Diabetes, 1991. 40(9): p. 1090-9.

- Newrick, P.G. , et al., Sural nerve oxygen tension in diabetes. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed), 1986. 293(6554): p. 1053-4.

- Tuck, R.R.; Schmelzer, J.D.; Low, P.A. ENDONEURIAL BLOOD FLOW AND OXYGEN TENSION IN THE SCIATIC NERVES OF RATS WITH EXPERIMENTAL DIABETIC NEUROPATHY. Brain 1984, 107, 935–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, H.-W.; Hsieh, J.-H.; Chien, H.-F.; Lin, Y.-H.; Yeh, T.-Y.; Chao, C.-C.; Hsieh, S.-T. CD40-mediated HIF-1α expression underlying microangiopathy in diabetic nerve pathology. Dis. Model. Mech. 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohib, M.M.; Rabe, S.; Nolze, A.; Rooney, M.; Ain, Q.; Zipprich, A.; Gekle, M.; Schreier, B. Eplerenone, a mineralocorticoid receptor inhibitor, reduces cirrhosis associated changes of hepatocyte glucose and lipid metabolism. Cell Commun. Signal. 2024, 22, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toutouzas, K.; Riga, M.; Stefanadi, E.; Stefanadis, C. Asymmetric Dimethylarginine (ADMA) and other Endogenous Nitric Oxide Synthase (NOS) Inhibitors as an Important Cause of Vascular Insulin Resistance. Horm. Metab. Res. 2008, 40, 655–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thum, T.; Fraccarollo, D.; Schultheiss, M.; Froese, S.; Galuppo, P.; Widder, J.D.; Tsikas, D.; Ertl, G.; Bauersachs, J. Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase Uncoupling Impairs Endothelial Progenitor Cell Mobilization and Function in Diabetes. Diabetes 2007, 56, 666–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kihara, M. and P.A. Low, Impaired vasoreactivity to nitric oxide in experimental diabetic neuropathy. Exp Neurol, 1995. 132(2): p. 180-5.

- Gonçalves, J.S.; Seiça, R.M.; Laranjinha, J.; Lourenço, C.F. Impairment of neurovascular coupling in the hippocampus due to decreased nitric oxide bioavailability supports early cognitive dysfunction in type 2 diabetic rats. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2022, 193, 669–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellemann, K.; Thorsteinsson, B.; Fugleberg, S.; Feldt-Rasmussen, B.; Andersen, O.O.; Grönbæk, P.; Binder, C. KINETICS OF INSULIN DISAPPEARANCE FROM PLASMA IN CORTISONE-TREATED NORMAL SUBJECTS. Clin. Endocrinol. 1987, 26, 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahaf, G. A Possible Common Neurophysiologic Basis for MDD, Bipolar Disorder, and Schizophrenia: Lessons from Electrophysiology. Front. Psychiatry 2016, 7, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zeng, W.; Sun, J.; Chen, W.; Zhang, R.; Yang, Z.; Yao, Z.; Wang, L.; Song, L.; Chen, Y.; et al. The quantification of blood-brain barrier disruption using dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in aging rhesus monkeys with spontaneous type 2 diabetes mellitus. NeuroImage 2017, 158, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batzias, K.; Antonopoulos, A.S.; Oikonomou, E.; Siasos, G.; Bletsa, E.; Stampouloglou, P.K.; Mistakidi, C.-V.; Noutsou, M.; Katsiki, N.; Karopoulos, P.; et al. Effects of Newer Antidiabetic Drugs on Endothelial Function and Arterial Stiffness: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Diabetes Res. 2018, 2018, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piconi, L. , et al., Intermittent high glucose enhances ICAM-1, VCAM-1, E-selectin and interleukin-6 expression in human umbilical endothelial cells in culture: the role of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. J Thromb Haemost, 2004. 2(8): p. 1453-9.

- Siddiqui, K.; George, T.P.; Mujammami, M.; Isnani, A.; Alfadda, A.A. The association of cell adhesion molecules and selectins (VCAM-1, ICAM-1, E-selectin, L-selectin, and P-selectin) with microvascular complications in patients with type 2 diabetes: A follow-up study. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1072288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quattrini, C.; Jeziorska, M.; Boulton, A.J.; Malik, R.A. Reduced Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Expression and Intra-Epidermal Nerve Fiber Loss in Human Diabetic Neuropathy. Diabetes Care 2008, 31, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schratzberger, P.; Walter, D.H.; Rittig, K.; Bahlmann, F.H.; Pola, R.; Curry, C.; Silver, M.; Krainin, J.G.; Weinberg, D.H.; Ropper, A.H.; et al. Reversal of experimental diabetic neuropathy by VEGF gene transfer. J. Clin. Investig. 2001, 107, 1083–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y., A. Yabluchanskiy, and M.L. Lindsey, Thrombospondin-1: the good, the bad, and the complicated. Circ Res, 2013. 113(12): p. 1272-4.

- Boucher, J.; Kleinridders, A.; Kahn, C.R. Insulin Receptor Signaling in Normal and Insulin-Resistant States. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2014, 6, a009191–a009191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleinridders, A.; Ferris, H.A.; Cai, W.; Kahn, C.R. Insulin Action in Brain Regulates Systemic Metabolism and Brain Function. Diabetes 2014, 63, 2232–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E Kelley, D.; Mandarino, L.J. Fuel selection in human skeletal muscle in insulin resistance: a reexamination. Diabetes 2000, 49, 677–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Cáceres, C.; Quarta, C.; Varela, L.; Gao, Y.; Gruber, T.; Legutko, B.; Jastroch, M.; Johansson, P.; Ninkovic, J.; Yi, C.-X.; et al. Astrocytic Insulin Signaling Couples Brain Glucose Uptake with Nutrient Availability. Cell 2016, 166, 867–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeger, M.; Popken, G.; Zhang, J.; Xuan, S.; Lu, Q.R.; Schwab, M.H.; Nave, K.; Rowitch, D.; D'ERcole, A.J.; Ye, P. Insulin-like growth factor type 1 receptor signaling in the cells of oligodendrocyte lineage is required for normal in vivo oligodendrocyte development and myelination. Glia 2006, 55, 400–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, M.; Choubey, M.; Tirumalasetty, M.B.; Arbee, S.; Mohib, M.M.; Wahiduzzaman; Mamun, M. A.; Uddin, M.B.; Mohiuddin, M.S. Adiponectin: A Promising Target for the Treatment of Diabetes and Its Complications. Life 2023, 13, 2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohib, M.; Rabby, S.F.; Paran, T.Z.; Hasan, M.; Ahmed, I.; Hasan, N.; Sagor, A.T.; Mohiuddin, S.; Hsu, T.-C. Protective role of green tea on diabetic nephropathy—A review. Cogent Biol. 2016, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-S.; Brill, S.J. Rfc4 Interacts with Rpa1 and Is Required for Both DNA Replication and DNA Damage Checkpoints in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001, 21, 3725–3737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Hwang, D.; Bataille, F.; Lefevre, M.; York, D.; Quon, M.J.; Ye, J. Serine Phosphorylation of Insulin Receptor Substrate 1 by Inhibitor κB Kinase Complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 48115–48121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. , et al., Diabetes mellitus and Alzheimer's disease: GSK-3β as a potential link. Behav Brain Res, 2018. 339: p. 57-65.

- Talbot, K. Brain Insulin Resistance in Alzheimer's Disease and its Potential Treatment with GLP-1 Analogs. Neurodegener. Dis. Manag. 2014, 4, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, W.-K.; Xian, Y.-X.; Zhang, L.; Lai, H.; Hou, X.-G.; Xu, Y.-X.; Yu, T.; Xu, F.-Y.; Song, J.; Fu, C.-L.; et al. Influence of blood glucose on the expression of glucose transporter proteins 1 and 3 in the brain of diabetic rats. Chin. Med J. 2007, 120, 1704–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.K. , et al., Predicting the efficiency of prime editing guide RNAs in human cells. Nat Biotechnol, 2021. 39(2): p. 198-206.

- Lete, M.G. , et al., Histones and DNA compete for binding polyphosphoinositides in bilayers. Biophys J, 2014. 106(5): p. 1092-100.

- Rangaraju, V.; Calloway, N.; Ryan, T.A. Activity-Driven Local ATP Synthesis Is Required for Synaptic Function. Cell 2014, 156, 825–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Kahn, M.; ter Horst, K.W.; Rodrigues, M.R.; Gaspar, R.C.; Hirabara, S.M.; Luukkonen, P.K.; Lee, S.; et al. A Membrane-Bound Diacylglycerol Species Induces PKCϵ-Mediated Hepatic Insulin Resistance. Cell Metab. 2020, 32, 654–664.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A Stoica, B.; A Movsesyan, V.; Iv, P.M.L.; I Faden, A. Ceramide-induced neuronal apoptosis is associated with dephosphorylation of Akt, BAD, FKHR, GSK-3β, and induction of the mitochondrial-dependent intrinsic caspase pathway. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2003, 22, 365–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AT Sagor, M. , et al., Angiotensin-II, a potent peptide, participates in the development of hepatic dysfunctions. Immunology, Endocrine & Metabolic Agents-Medicinal ChemistryCurrent Medicinal Chemistry-Immunology, Endocrine & Metabolic Agents), 2016. 16(3): p. 161-177.

- El-Aarag, B.; Shalaan, E.S.; Ahmed, A.A.; Sayed, I.E.T.E.; Ibrahim, W.M. Cryptolepine Analog Exhibits Antitumor Activity against Ehrlich Ascites Carcinoma Cells in Mice via Targeting Cell Growth, Oxidative Stress, and PTEN/Akt/mTOR Signaling Pathway. Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem. 2024, 24, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellar, D.; Lockhart, S.N.; Aisen, P.; Raman, R.; Rissman, R.A.; Brewer, J.; Craft, S. Intranasal Insulin Reduces White Matter Hyperintensity Progression in Association with Improvements in Cognition and CSF Biomarker Profiles in Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer's Disease. J. Prev. Alzheimer's Dis. 2021, 8, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craft, S. , et al., Intranasal insulin therapy for Alzheimer disease and amnestic mild cognitive impairment: a pilot clinical trial. Arch Neurol, 2012. 69(1): p. 29-38.

- Kopp, K.O.; Glotfelty, E.J.; Li, Y.; Greig, N.H. Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists and neuroinflammation: Implications for neurodegenerative disease treatment. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 186, 106550–106550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölscher, C. Brain insulin resistance: role in neurodegenerative disease and potential for targeting. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2020, 29, 333–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, A.; Shimu, S.J.; Faika, M.J.; Islam, T.; Ferdous, N.-E.; Nessa, A. Bangladeshi parents’ knowledge and awareness about cervical cancer and willingness to vaccinate female family members against human papilloma virus: a cross sectional study. Int. J. Community Med. Public Heal. 2023, 10, 3446–3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coopmans, C.; Zhou, T.L.; Henry, R.M.; Heijman, J.; Schaper, N.C.; Koster, A.; Schram, M.T.; van der Kallen, C.J.; Wesselius, A.; Engelsman, R.J.D.; et al. Both Prediabetes and Type 2 Diabetes Are Associated With Lower Heart Rate Variability: The Maastricht Study. Diabetes Care 2020, 43, 1126–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaz, B.; Bazin, T.; Pellissier, S. The Vagus Nerve at the Interface of the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Fu, T.; Liu, W.; Du, Y.; Bu, J.; Wei, G.; Yu, M.; Lin, Y.; Min, C.; Lin, D. An Update on the Role and Potential Molecules in Relation to Ruminococcus gnavus in Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Obesity and Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes, Metab. Syndr. Obesity: Targets Ther. 1235; 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, A.Z.; Rodrigues, N.d.C.; Gonzaga, M.I.; Paiolo, J.C.C.; de Souza, C.A.; Stefanutto, N.A.V.; Omori, W.P.; Pinheiro, D.G.; Brisotti, J.L.; Junior, E.M.; et al. Detection of Increased Plasma Interleukin-6 Levels and Prevalence of Prevotella copri and Bacteroides vulgatus in the Feces of Type 2 Diabetes Patients. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erny, D. , et al., Host microbiota constantly control maturation and function of microglia in the CNS. Nat Neurosci, 2015. 18(7): p. 965-77.

- Tolhurst, G.; Heffron, H.; Lam, Y.S.; Parker, H.E.; Habib, A.M.; Diakogiannaki, E.; Cameron, J.; Grosse, J.; Reimann, F.; Gribble, F.M. Short-Chain Fatty Acids Stimulate Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Secretion via the G-Protein-Coupled Receptor FFAR2. Diabetes 2012, 61, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothhammer, V.; Mascanfroni, I.D.; Bunse, L.; Takenaka, M.C.; Kenison, J.E.; Mayo, L.; Chao, C.-C.; Patel, B.; Yan, R.; Blain, M.; et al. Type I interferons and microbial metabolites of tryptophan modulate astrocyte activity and central nervous system inflammation via the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Nat. Med. 2016, 22, 586–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Mello, V.D. , et al., Indolepropionic acid and novel lipid metabolites are associated with a lower risk of type 2 diabetes in the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study. Sci Rep, 2017. 7: p. 46337.

- Garcez, M.L.; Tan, V.X.; Heng, B.; Guillemin, G.J. Sodium Butyrate and Indole-3-propionic Acid Prevent the Increase of Cytokines and Kynurenine Levels in LPS-induced Human Primary Astrocytes. Int. J. Tryptophan Res. 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keitel, V.; Görg, B.; Bidmon, H.J.; Zemtsova, I.; Spomer, L.; Zilles, K.; Häussinger, D. The bile acid receptor TGR5 (Gpbar-1) acts as a neurosteroid receptor in brain. Glia 2010, 58, 1794–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Su, M.; Wang, L.; Gong, Q.; Wei, X. Activation of the bile acid receptors TGR5 and FXR in the spinal dorsal horn alleviates neuropathic pain. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2023, 29, 1981–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benichou, T.; Pereira, B.; Mermillod, M.; Tauveron, I.; Pfabigan, D.; Maqdasy, S.; Dutheil, F.; A Malik, R. Heart rate variability in type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta–analysis. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0195166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonomo, R.R.; Cook, T.M.; Gavini, C.K.; White, C.R.; Jones, J.R.; Bovo, E.; Zima, A.V.; Brown, I.A.; Dugas, L.R.; Zakharian, E.; et al. Fecal transplantation and butyrate improve neuropathic pain, modify immune cell profile, and gene expression in the PNS of obese mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020, 117, 26482–26493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Guo, L.; Feng, S.; Wang, C.; Cui, Z.; Wang, S.; Lu, Q.; Chang, H.; Hang, B.; Snijders, A.M.; et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation ameliorates type 2 diabetes via metabolic remodeling of the gut microbiota in db/db mice. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2023, 11, e003282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, K.; Yasujima, M.; Yagihashi, S. Role of Advanced Glycation End Products in Diabetic Neuropathy. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2008, 14, 953–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, H.; Sun, Y.; Lin, P.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Y.; Qiao, Y.; Liu, D.; Chiefari, E. Glucose Fluctuation Inhibits Nrf2 Signaling Pathway in Hippocampal Tissues and Exacerbates Cognitive Impairment in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats. J. Diabetes Res. 2024, 2024, 5584761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, J.; Li, X.; Tian, H.; Liu, C.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, S.; Chu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L. Neuroprotective effect of diosgenin in a mouse model of diabetic peripheral neuropathy involves the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2020, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, D.J.; Martyn, C.N.; Young, R.J.; Clarke, B.F. The Value of Cardiovascular Autonomic Function Tests: 10 Years Experience in Diabetes. Diabetes Care 1985, 8, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohib, M.M.; Rabe, S.; Nolze, A.; Rooney, M.; Ain, Q.; Zipprich, A.; Gekle, M.; Schreier, B. Eplerenone, a mineralocorticoid receptor inhibitor, reduces cirrhosis associated changes of hepatocyte glucose and lipid metabolism. Cell Commun. Signal. 2024, 22, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pop-Busui, R. , Cardiac autonomic neuropathy in diabetes: a clinical perspective. Diabetes Care, 2010. 33(2): p. 434-41.

- Braffett, B.H.; Gubitosi-Klug, R.A.; Albers, J.W.; Feldman, E.L.; Martin, C.L.; White, N.H.; Orchard, T.J.; Lopes-Virella, M.; Lachin, J.M.; Pop-Busui, R.; et al. Risk Factors for Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy and Cardiovascular Autonomic Neuropathy in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (DCCT/EDIC) Study. Diabetes 2020, 69, 1000–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Brien, P.D., S. A. Sakowski, and E.L. Feldman, Mouse models of diabetic neuropathy. Ilar j, 2014. 54(3): p. 259-72.

- Doty, M.; Yun, S.; Wang, Y.; Hu, M.; Cassidy, M.; Hall, B.; Kulkarni, A.B. Integrative multiomic analyses of dorsal root ganglia in diabetic neuropathic pain using proteomics, phospho-proteomics, and metabolomics. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohib, M. , et al. Hypoxia induces activation of Mineralocorticoid receptor. in ACTA PHYSIOLOGICA. 2022. WILEY 111 RIVER ST, HOBOKEN 07030-5774, NJ USA.

- Latif-Hernandez, A.; Yang, T.; Butler, R.R.; Losada, P.M.; Minhas, P.S.; White, H.; Tran, K.C.; Liu, H.; Simmons, D.A.; Langness, V.; et al. A TrkB and TrkC partial agonist restores deficits in synaptic function and promotes activity-dependent synaptic and microglial transcriptomic changes in a late-stage Alzheimer's mouse model. Alzheimer's Dement. 2024, 20, 4434–4460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, N.; Edwards, K.; Russell, A.W.; Perkins, B.A.; Malik, R.A.; Efron, N. Corneal Confocal Microscopy Predicts 4-Year Incident Peripheral Neuropathy in Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2015, 38, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, M.A.; Zhang, E.; Natarajan, R. Epigenetic mechanisms in diabetic complications and metabolic memory. Diabetologia 2014, 58, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenvers, D.J.; Scheer, F.A.J.L.; Schrauwen, P.; la Fleur, S.E.; Kalsbeek, A. Circadian clocks and insulin resistance. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2018, 15, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, J.; Sloan, G.; Stevens, L.; Selvarajah, D.; Cruccu, G.; Gandhi, R.A.; Kempler, P.; Fuller, J.H.; Chaturvedi, N.; Tesfaye, S.; et al. Female sex is a risk factor for painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy: the EURODIAB prospective diabetes complications study. Diabetologia 2023, 67, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).