Submitted:

17 August 2025

Posted:

18 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is one of the most important causes of disability and mortality and is associated with several complications. Rhythm control through AF ablation is strongly suggested with pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) through single-shot ablation devices, like cryoballoon ablation (CBA) and circumferential pulsed-field ablation (PFA). In this review we will analyse the differences between these two techniques, in terms of their efficacy and safety profile. Then we will underline that the debate on the differences in costs between CBA and PFA is still controversial. For the lack of continuous rhythm monitoring during follow-up in most of the studies conducted, it is difficult to establish which one of these two technologies is more suitable for a given patient. Nowadays, the comparison between CBA and PFA is constantly evolving.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Biophysical Mechanism of Action

2.1. CBA

2.2. PFA

2.2.1. Electric Field Parameters

2.2.2. Thermal Effect: Is It Possible?

3. Are There Predictive Parameters of Success?

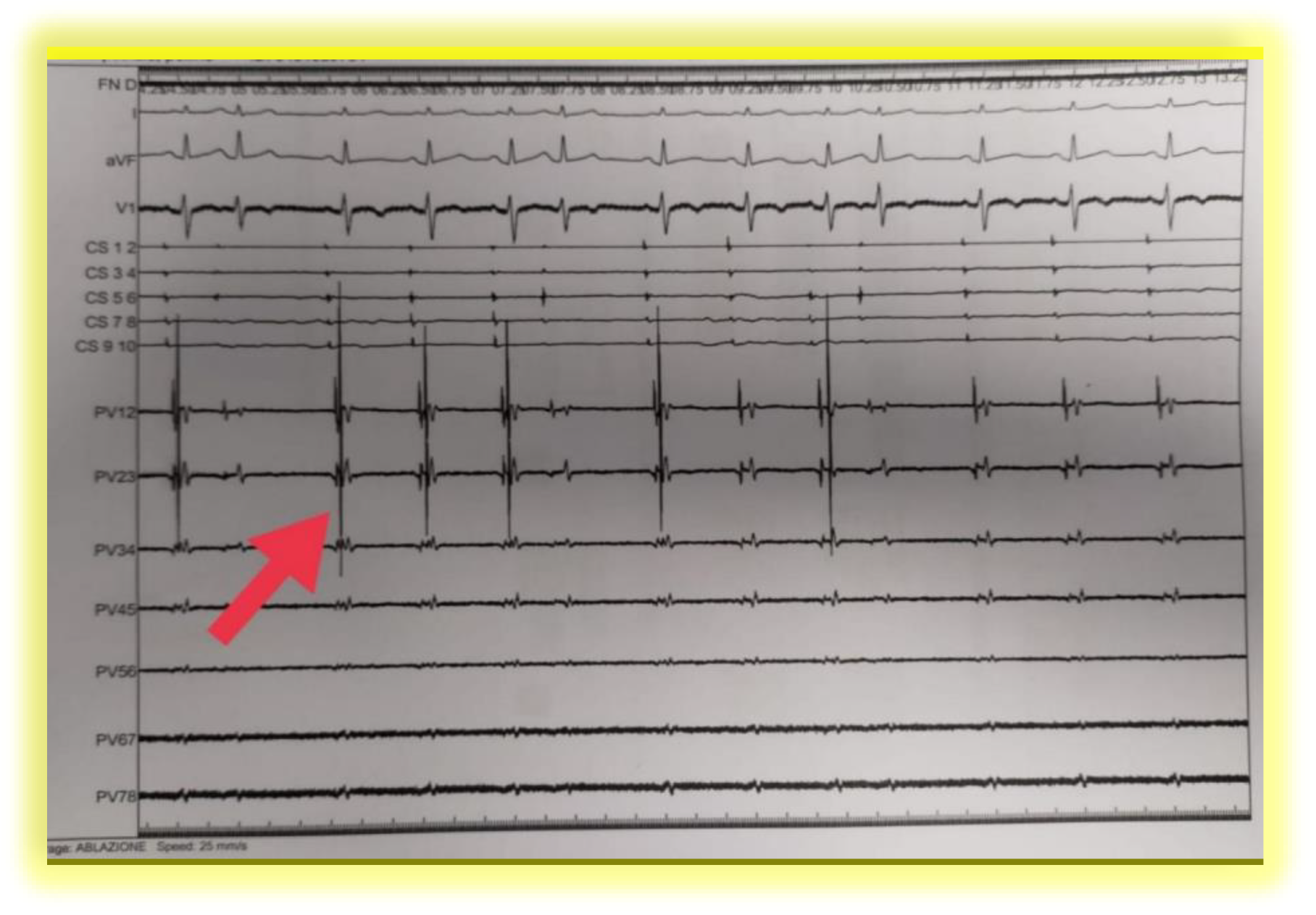

3.1. With CBA …

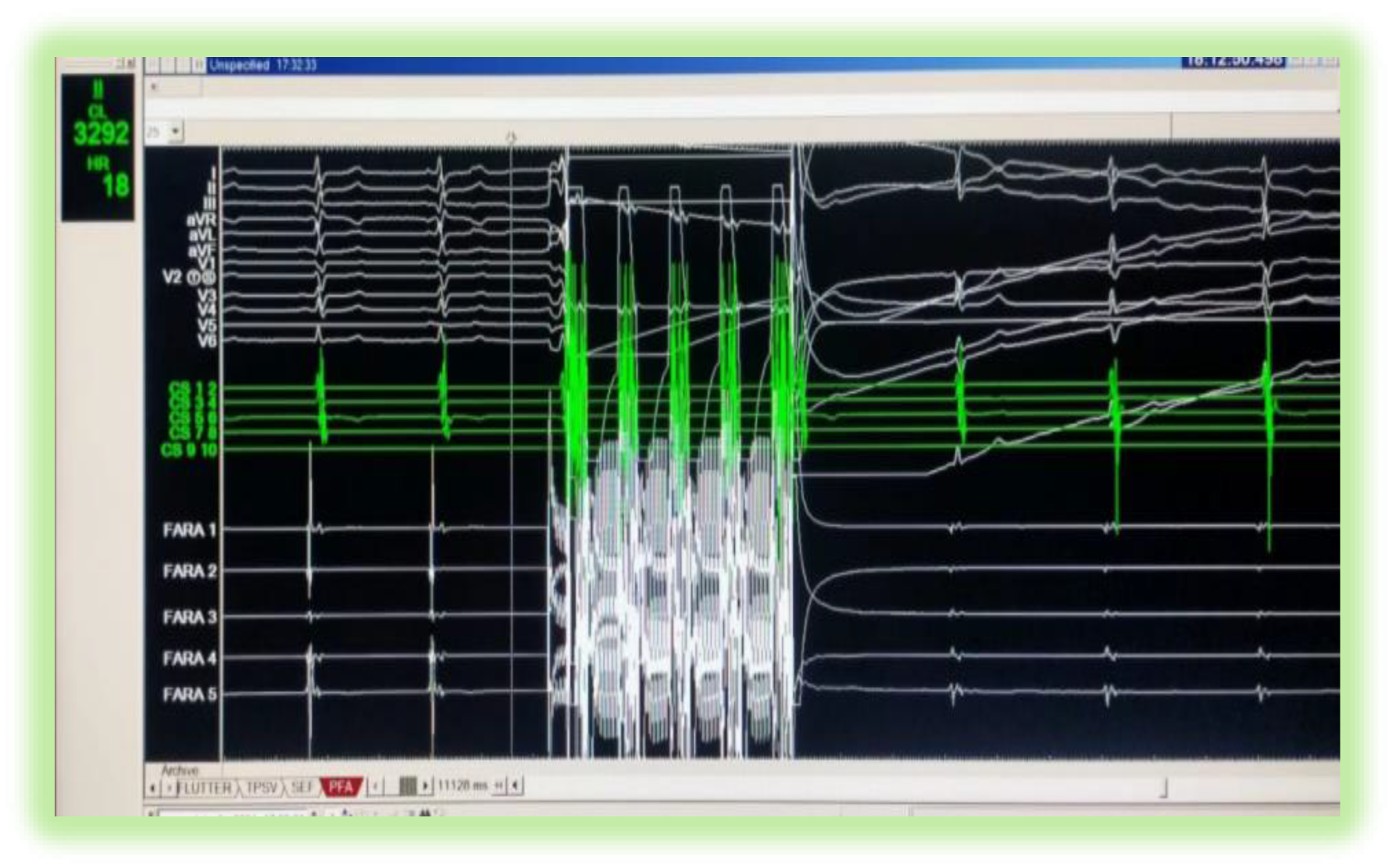

3.2. With PFA …

4. Cardiac and Neuronal Biomarkers: PFA versus CBA

5. Database Research and Selection Criteria of Patients

6. Acute and long-Term Efficacy

6.1. PVs’ Reconnection After CBA or PFA: Where Is the Truth?

7. Safety and Adverse Effects

8. Versatility

9. Costs

10. Conclusions

Conflict of Interests

References

- Wolf, P.A.; Abbott, R.D.; Kannel, W.B. , Atrial fibrillation as an independent risk factor for stroke: the Framingham Study. Stroke 1991, 22, 983–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.J.; Larson, M.G.; Levy, D.; et al. Temporal relations of atrial fibrillation and congestive heart failure and their joint influence on mortality: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2003, 107, 2920–2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, A.; Breteler, M.M.B.; de Bruyne, M.C.; et al. Atrial fibrillation and dementia in a population-based study: the Rotterdam Study. Stroke 1997, 28, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haïssaguerre, M.; Jaïs, P.; Shah, D.C.; et al. Spontaneous initiation of atrial fibrillation by ectopic beats originating in the pulmonary veins. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 339, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wazni, O.M.; Marrouche, N.F.; Martin, D.O.; et al. Radiofrequency ablation vs antiarrhythmic drugs as first-line treatment of symptomatic atrial fibrillation: A randomized trial. JAMA 2005, 293, 2634–2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calkins, H.; Reynolds, M.R.; Spector, P.; et al. Treatment of atrial fibrillation with antiarrhythmic drugs or radiofrequency ablation: Two systematic literature reviews and meta-analyses. Circ. Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 2009, 2, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, J.G.; Wells, G.A.; Deyell, M.W.; et al. Cryoablation or drug therapy for initial treatment of atrial fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Rocca, D.G.; Marcon, L.; Magnocavallo, M.; et al. Pulsed electric field, cryoballoon, and radiofrequency for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation ablation: a propensity score-matched comparison. Europace. 2023, 26, euae016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gelder, I.C.; Rienstra, M.; Bunting, K.V.; et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J. 2024, 45, 3314–3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairy, P.; Dubuc, M. Transcatheter cryoablation part I: preclinical experience. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2008, 31, 112–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, J.G.; Dubuc, M.; Guerra, P.G.; et al. The biophysics and biomechanics of cryoballoon ablation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2012, 35, 1162–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugrue, A.; Maor, E.; Del-Carpio Munoz, F.; et al. Cardiac ablation with pulsed electric fields: principles and biophysics. Europace. 2022, 24, 1213–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, C.; Lv, Y.; Dong, S.; et al. Irreversible electroporation ablation area enhanced by synergistic high- and low-voltage pulses. PLoS One. 2017, 12, e0173181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavee, J.; Onik, G.; Mikus, P.; et al. A novel nonthermal energy source for surgical epicardial atrial ablation: irreversible electroporation. Heart Surg Forum. 2007, 10, E162–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugrue, A.; Vaidya, V.; Witt, C.; et al. Irreversible electroporation for catheter-based cardiac ablation: a systematic review of the preclinical experience. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2019, 55, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maor, E.; Sugrue, A.; Witt, C.; et al. Pulsed electric fields for cardiac ablation and beyond: A state-of-the-art review. Heart Rhythm. 2019, 16, 1112–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, D.C.; Reberšek, M.; Dermol, J.; et al. Quantification of cell membrane permeability induced by monopolar and high-frequency bipolar bursts of electrical pulses. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016, 1858, 2689–2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anić, A.; Phlips, T.; Brešković, T.; et al. Pulsed field ablation using focal contact force-sensing catheters for treatment of atrial fibrillation: acute and 90-day invasive remapping results. Europace. 2023, 25, euad147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar, B.Y.; Yusuf, Y.A.; Esmati, M.H. Analysis of pulsed field ablation using focal contact force-sensing catheters for treatment of atrial fibrillation: acute and 90-day invasive remapping results. Europace. 2023, 25, euad287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, I.; Koruth, J. Novel Ablation Catheters for Atrial Fibrillation. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2024, 25, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiachris, D.; Antoniou, C.K.; Doundoulakis, I.; et al. Best Practice Guide for Cryoballoon Ablation in Atrial Fibrillation: The Compilation Experience of More than 1000 Procedures. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2023, 10, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Ortega, C.A.; Ruiz, M.A.; Solórzano-Guillén, C.; et al. Time to -30°C as a predictor of acute success during cryoablation in patients with atrial fibrillation. Cardiol J. 2023, 30, 534–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciconte, G.; Mugnai, G.; Sieira, J.; et al. On the Quest for the Best Freeze: Predictors of Late Pulmonary Vein Reconnections After Second-Generation Cryoballoon Ablation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2015, 8, 1359–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, L.B.; Wollner, K.; Chu, S.Y.; et al. Thawing plateau time indicating the duration of phase transition from ice to water is the strongest predictor for long-term durable pulmonary vein isolation after cryoballoon ablation for atrial fibrillation-Data from the index and repeat procedures. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2023, 10, 1058485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babak, A.; Kauffman, C.B.; Lynady, C.; et al. Pulmonary vein capture is a predictor for long-term success of stand-alone pulmonary vein isolation with cryoballoon ablation in patients with persistent atrial fibrillation. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2024, 10, 1150378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Potter, T.; Grimaldi, M.; Duytschaever, M.; et al. Predictors of Success for Pulmonary Vein Isolation With Pulsed-field Ablation Using a Variable-loop Catheter With 3D Mapping Integration: Complete 12-month Outcomes From inspIRE. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2024, 17, e012667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mountantonakis, S.; Gerstenfeld, E.P.; Mansour, M.; et al. Predictors of atrial fibrillation freedom using pulsed field vs thermal catheter ablation for the treatment of atrial fibrillation-Result of the ADVENT study. Heart Rhythm 21, S45–S46. [CrossRef]

- Amorós-Figueras, G.; Casabella-Ramon, S.; Moreno-Weidmann, Z.; et al. Dynamics of High-Density Unipolar Epicardial Electrograms During PFA. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2023, 16, e011914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krisai, P.; Knecht, S.; Badertscher, P.; et al. Troponin release after pulmonary vein isolation using pulsed field ablation compared to radiofrequency and cryoballoon ablation. Heart Rhythm. 2022, 19, 1471–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemoine, M.D.; Mencke, C.; Nies, M.; et al. Pulmonary Vein Isolation by Pulsed-field Ablation Induces Less Neurocardiac Damage Than Cryoballoon Ablation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2023, 16, e011598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, V.Y.; Gerstenfeld, E.P.; Natale, A.; et al. Pulsed Field or Conventional Thermal Ablation for Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2023, 389, 1660–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbanek, L.; Bordignon, S.; Schaack, D.; et al. Pulsed Field Versus Cryoballoon Pulmonary Vein Isolation for Atrial Fibrillation: Efficacy, Safety, and Long-Term Follow-Up in a 400-Patient Cohort. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2023, 16, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cespón-Fernández, M.; Della Rocca, D.G.; Almorad, A.; et al. Versatility of the novel single-shot devices: A multicenter analysis. Heart Rhythm. 2023, 20, 1463–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiavone, M.; Bianchi, S.; Malacrida, M.; et al. Novel cryoballoon technology for atrial fibrillation ablation: Impact of pulmonary vein variant anatomy, cooling characteristics, and 1-year outcome from the CHARISMA registry. Heart Rhythm. 2024, S1547-5271(24)03238-7. [CrossRef]

- Badertscher, P.; Weidlich, S.; Knecht, S.; et al. Efficacy and safety of pulmonary vein isolation with pulsed field ablation vs. novel cryoballoon ablation system for atrial fibrillation. Europace. 2023, 25, euad329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, H.; Lu, H.; et al. Meta-analysis of pulsed-field ablation versus cryoablation for atrial fibrillation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2024, 47, 603–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, I.; Mastella, G.; Bernlochner, I.; et al. Efficacy and safety of pulsed field ablation compared to cryoballoon ablation in the treatment of atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis. Eur Heart J Open. 2024, 4, oeae044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetta, G.; Della Rocca, D.G.; Parlavecchio, A.; et al. Multielectrode catheter-based pulsed electric field vs. cryoballoon for atrial fibrillation ablation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Europace. 2024, 26, euae293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivek Y, Reddy; et al. Pulsed field ablation of persistent atrial fibrillation with continuous electrocardiographic monitoring follow-up: ADVANTAGE AF Phase 2. Circ. Arrhyth. Electrophysiol 2025, 152, 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.; Yu, H.T.; Shim, J.; et al. Cryoballoon Pulmonary Vein Isolation With Versus Without Additional Right Atrial Linear Ablation for Persistent Atrial Fibrillation: The CRALAL Randomized Clinical Trial. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2025, 18, e013408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isenegger, C.; Arnet, R.; Jordan, F.; et al. Pulsed-field ablation versus cryoballoon ablation in patients with persistent atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc. 2025, 59, 101684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katov, L.; Teumer, Y.; Bothner, C.; et al. Comparative Analysis of Real-World Clinical Outcomes of a Novel Pulsed Field Ablation System for Pulmonary Vein Isolation: The Prospective CIRCLE-PVI Study. J Clin Med. 2024, 13, 7040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurhofer, J.; Kueffer, T.; Knecht, S.; et al. Comparison of Cryoballoon vs. Pulsed Field Ablation in Patients with Symptomatic Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation (SINGLE SHOT CHAMPION): Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Heart Rhythm O2. 2024, 5, 460–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reichlin, T.; Kueffer, T.; Badertscher, P.; et al. Pulsed Field or Cryoballoon Ablation for Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation. New England Journal of Medicine 2025, 392, 1497–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scherr, D.; Turagam, M.K.; Maury, P.; et al. Repeat Procedures After Pulsed Field Ablation for Atrial Fibrillation: MANIFEST-REDO Study. Europace. 2025, euaf012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiavone, M.; Molon, G.; Pieragnoli, P.; et al. Very Long-Term Follow-Up of Pulmonary Vein Isolation Using Cryoballoon for Catheter Ablation for Atrial Fibrillation: An 8-Year Multicenter Experience. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2025, e013645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chehirlian, L.; Koutbi, L.; Mancini, J.; et al. High Incidence of Phrenic Nerve Injury in Patients Undergoing Pulsed Field Ablation for Atrial Fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2025, S1547-5271(25)02751-1. [CrossRef]

- Howard, B.; Haines, D.E.; Verma, A.; et al. Characterization of Phrenic Nerve Response to Pulsed Field Ablation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2022, 15, e010127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oda, Y.; Nogami, A.; Igarashi, D.; et al. A Case Report of Persistent Phrenic Nerve Injury by Pulsed Field Ablation: Lessons from Anatomical Reconstruction and Electrode Positioning, Heart Rhythm case report 2025, 11, 763-766. [CrossRef]

- Ekanem, E.; Neuzil, P.; Reichlin, T.; et al. Safety of pulsed field ablation in more than 17,000 patients with atrial fibrillation in the MANIFEST-17K study. Nat Med. 2024, 30, 2020–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakkireddy, D.; Katapadi, A.; Garg, J.; et al. NEMESIS-PFA: Investigating Collateral Tissue Injury Associated With Pulsed Field Ablation. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2025, S2405-500X(25)00274-9. [CrossRef]

- Regany-Closa, M.; Pomes-Perez, J.; Invers-Rubio, E.; et al. Head-to-head comparison of pulsed-field ablation, high-power short-duration ablation, cryoballoon and conventional radiofrequency ablation by MRI-based ablation lesion assessment. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhaeghe, L.; L'Hoyes, W.; Vijgen, J.; et al. Left atrial function after atrial fibrillation ablation with pulsed field versus radiofrequency energy: a comparative study. Heart Rhythm. 2025, S1547-5271(25)02724-9. [CrossRef]

- Giannopoulos, G.; Kossyvakis, C.; Vrachatis, D.; et al. , Effect of cryoballoon and radiofrequency ablation for pulmonary vein isolation on left atrial function in patients with nonvalvular paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: A prospective randomized study (Cryo-LAEF study). J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2019, 30, 991–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soysal, A.U.; Ozturk, S.; Onder, S.E.; et al. Left atrial functions in the early period after cryoballoon ablation for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2023, 46, 861–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkaya, E.; Berkowitsch, A.; Rieth, A.; et al. Clinical outcome and left atrial function after left atrial roof ablation using the cryoballoon technique in patients with symptomatic persistent atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol. 2019, 292, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigeta, T.; Yamauchi, Y.; Oda, A.; et al. How to perform effective cryoballooon ablation of left atrial roof: considerations after experiences of more than 1000 cases. European Heart Journal 2022. [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, S.; Hasegawa, K.; Mukai, M.; et al. Cryoballoon left atrial roof ablation for persistent atrial fibrillation-Analysis with high-resolution mapping system. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2022, 45, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erkapic, D.; Roussopoulos, K.; Aleksic, M.; et al. Cryoballoon-Assisted Pulmonary Vein Isolation and Left Atrial Roof Ablation Using a Simplified Sedation Strategy without Esophageal Temperature Monitoring: No Notable Thermal Esophageal Lesions and Low Arrhythmia Recurrence Rates after 2 Years. Diagnostics (Basel). 2024, 14, 1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odagiri, F.; Tokano, T.; Miyazaki, T.; et al. Clinical impact of cryoballoon posterior wall isolation using the cross-over technique in persistent atrial fibrillation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2024, 47, 1326–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kueffer, T.; Tanner, H.; Madaffari, A.; et al. Posterior wall ablation by pulsed-field ablation: procedural safety, efficacy, and findings on redo procedures. Europace. 2023, 26, euae006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yogarajah, J.; Hutter, J.; Kahle, P.; et al. Initial Real-World Experiences of Pulmonary Vein Isolation and Ablation of Non-Pulmonary Vein Sites Using a Novel Circular Array Pulsed Field Ablation Catheter. J Clin Med. 2024, 13, 6961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Rocca, D.G.; Sorgente, A.; Pannone, L.; et al. Multielectrode catheter-based pulsed field ablation of persistent and long-standing persistent atrial fibrillation. Europace. 2024, 26, euae246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commissione per la valutazione delle tecnologie e degli investimenti sanitari della Regione Toscana, www301.regione.toscana.it/bancadati/atti/Contenuto.xml?id=5409796&nomeFile=Decreto_n.4588_del_05-03-2024-Allegato-3.

- Jungen, C.; Rattka, M.; Bohnen, J.; et al. Impact of overweight and obesity on radiation dose and outcome in patients undergoing pulmonary vein isolation by cryoballoon and pulsed field ablation. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc. 2024, 55, 101516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Success Predictors | Independent or dependent? | Linking to extension of myocardial injury |

|---|---|---|

| TTI [21] | Independent | None |

| Time of reaching of target temperature (-40°C) [22,23] |

Independent | None |

| thawing speed [24] |

Dependent | Thawing plateau prolongation correlates with TnT levels [24] |

| Coldest nadir temperature achieved [21,22,23,24] | Dependent | None |

| PV occlusion grade [21] | Independent | None |

| PV capture [25] | Independent | None |

| Success Predictors | Is it related to only particular PFA catheter? | Applications in AF ablations |

|---|---|---|

| Number of applications of PFA >= 12 for PV [26] | Varipulse | Yes |

| Failure of class I/III antiarrhythmic drugs prior to PFA [27] | Farapulse | Yes |

| Different epicardial unipolar electrograms after 30 minutes of PFA [28] | Monopolar focal catheter | No, in ventricular ablations |

| Single procedure average cost | Expected number of patients successfully treated out of 5000 procedures | Global cost of 5000 procedures | Expected number of patients successfully treated with 5 million euros expense | Expected number of patients successfully treated with 5 million euros expense | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFA | 5500 euros | 3750 | 27,5 million euros | 682 | 6150 |

| CBA | 4500 euros | 3600 | 22,5 million euros | 790 | 7200 |

| Difference between PFA and CBA | 1000 euros | 150 | 5 million euros | -108 | -1050 |

| Procedural time | ↓ | ↑ |

| Costs of ablation kit | ↑ | ↓ |

| Cost/Benefit ratio | ↓ | ↑ |

| Cardiomyocyte specific damage | ↑ | ↓ |

| Neuronalspecific damage | ↓ | ↑ |

| Necessity of sedation | ↑ ↑ | ↑ |

| Complete PVI at first shot | ↑ ↑ | ↑ |

| At 1 year AF recurrence freedom after ablation | ↑ ↑ | ↑ |

| Phrenic nerve and exophagus damage | ↓ | ↑ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).