1. Introduction

Idiopathic Ventricular arrythmias (VAs) including ventricular premature contractions (VPCs) and ventricular tachycardia are common arrythmias. Theses arrythmias can be benign without any symptoms or consequences but can cause severe symptoms and can lead to arrythmia induced cardiomyopathy mainly when the burden of the arrythmia is high. Antiarrhythmic drugs are not always effective and may have proarrhythmic effect. However, catheter ablation of idiopathic VAs is highly successful and is accepted as a first-line therapy or as alternative for anti arrhythmic medications by current guidelines [

1]. Overall the success rate is about 90%. However, anatomic and or electrophysiologic limitations can reduce the success rate in some patients. VAs originated from papillary muscles, para-hisian area, and Left ventricular (LV) summit are examples of challenging sites for mapping and ablation and relatively low success sites compared to highly success site as right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) despite the advances in mapping and ablation techniques in the last years [

1]. LV summit is the highest portion of the LV epicardium, near the bifurcation of the left main coronary artery (LMCA), and accounts for up to 14.5% of LV VAs [

2]. LV summit is important origin for VA including VPC and ventricular tachycardia. However, the complex electroanatomic structure of LV summit and the surrounding anatomic sites, makes ablation of this arrythmia challenging. The likely reason for limited success of catheter ablation for these VAs is because their site of origin is subepicardial and/or intramural. Understanding the anatomy of LV summit and the adjacent anatomic structures and using different mapping techniques is crucial for localization of the origin of the arrythmia and the target site for ablation [

3,

4].

In this paper, we review the main strategies for mapping and ablation of LV summit VAs and summarize our experience in ablation of these challenging arrythmias.

2. Anatomy of LV Summit

LV summit is a triangular region situated in the most superior part of the left epicardial ventricular region covered more or less by epicardial isolating layers of fat [

5]. This triangular region bounded by the bifurcation between the left anterior descending (LAD) and the left circumflex (LCx) coronary arteries and is bisected laterally by the great cardiac vein (GCV) resulting in 2 regions: inaccessible area ( medial and more superior region, close to the apex of the triangle ) to catheter ablation because of close proximity to the major coronary vessels and the presence of epicardial fat; and accessible area to catheter ablation which is more lateral and inferior region, toward the base of the triangle [

2]. The endocardial site which is against to LV summit is the basal portion of the LV ostium next to the septum and in direct contact with the left coronary cusp (LCC). The LCC forms the lateral and posterolateral attachment of the aorta to the LV ostium and is in close proximity to the intramural component of the LV summit [

6]. On the other side, the anteroseptal aspect of the right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) is also adjacent to the LCC, in close proximity to the LAD and anterior interventricular vein (AIV), where as its posteroseptal aspect is adjacent to the right coronary cusp [

6].

The myocardium bounded between the epicardium of LV summit and LV endocardium below aortic cusps can be a source of arrythmias referred to LV summit VAs. Based on the anatomical definition of the LV summit, LV summit VAs can have different electrophysiologic characteristics and different anatomical approaches for ablation. Targeting these arrhythmias can be directly by ablating the exact origin or indirectly by targeting the adjacent structures and anatomic vantage points including left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT), LCC, GCV/AIV, RVOT, or pulmonic cusps [

7]. The septal branches of the LAD and the septal veins draining into the AIV could also be used for mapping and ablation of these arrhythmias [

6].

3. ECG Characteristics of LV Summit

Given the close proximity of LV summit to various anatomical structures, there is significant overlap of electrocardiographic pattern of VAs originated from LV summit, LVOT, aortomitral continuity, aortic cusps, coronary venous system and RVOT [

8,

9,

10,

11]. LV summit VAs typically have a right bundle branch block (RBBB) pattern with inferior axis and larger R waves in lead III compared to lead II but a left bundle branch block (LBBB) pattern with inferior axis and early transition (V2 or V3) also can be seen [

2]. A QS pattern in lead I is observed in 30% of patients [

6]. Another unique ECG pattern is the precordial “pattern break” in V2, consisting of an abrupt loss of R wave in lead V2 compared to V1 and V3 [

11]. This suggests an origin from the septal aspect of the LV summit (anatomically opposite to lead V2), usually in close proximity to the LAD and less likely to be eliminated from the epicardial aspect. Proximity to LAD precludes ablation in about half of patients. Long-term VA suppression could be achieved in only 58% of cases most commonly when the earliest site is at the anterior and leftward RVOT just under the pulmonic valve (PV) [

11]. Left bundle branch morphology and an abrupt R-wave transition in lead V

3 indicating the septal margin of LV summit was also reported. Eighty percent of outflow VA with abrupt R-wave transition in lead V

3 that overwhelmingly exhibited the earliest activation from the epicardium or mid-myocardium was eliminated by ablation from the vantage point of the interleaflet triangle below the right-left coronary junction as reported by Liao et al [

12].

4. Mapping

Because of the complex anatomy of LV summit , the highly variable anatomic relationships and the overlapping of ECG patterns with adjacent structures, it is important to performed detailed electroanatomical mapping of LV summit and all structures that are in close proximity or have anatomical connection to LV summit. RVOT and pulmonic cusps should be mapped. This is important not only for looking for early activation but also for potential anatomic sites for ablation in case of unsuccessful LV summit ablation or in ability to deliver energy in the left endocardial side or within coronary venous system because of close proximity of major coronary arteries or in case of intramural origin of outflow arrythmia. Coronary venous system should be also be mapped by advancing mapping catheter deep into coronary sinus (CS) to GCV- AIV junction. In many cases, ablation catheter can not be advanced deep in the coronary venous system mainly if the diameter of the vessels is small. Diagnostic catheters with small diameters can be used for these purpose and can used for anatomical reference that can help during anatomical ablation from RVOT or LVOT facing the earliest activation at GCV-AIV site. Recently, wires are used for unipolar mapping. Wires can be advanced deep into AIV septal branches. These wires can also serve as reference for anatomical ablation or can be used for ablation.

Then aortic cusps by retrograde approach , LVOT by retrograde or trans septal approach should be mapped in details. The LVOT should be carefully mapped including the area below the coronary cusps, aortomitral continuity and lateral LVOT area. The area just below the aortic cusps is a challenging area for mapping and can be missed. Combined retrograde transaortic approach and antegrade transseptal approach with a reversed S curve of the ablation catheter maybe needed to reach the anterosuperior LVOT below the aortic cusps as reported by Ouyang et al [

13]. Intracardiac echocardiography (ICE) can help for understanding and defining the anatomy of LV summit and marking the important sites of the LV summit and adjacent sites during mapping and ablation. Depending on the 3-dimensional mapping system used, a 3D anatomic map of the ventricles, outflow tracts , aortic cusps and pulmonic cusps can be constructed using ICE and dedicated modules. This 3D anatomic map can be integrated into and displayed on the 3D elctroanatomical map [

14]. Cardiac computed tomography (CT) can also be used and integrated into 3D mapping system to better understand the complex anatomy of RVOT, LVOT, coronary arteries and coronary venous system [

15].

The aim of mapping is to define target sites for ablation. It is important to realize that early activation during VPCs and or perfect pacemapping are not always exist and even if exist, ablation is not always possible or effective due to proximity to coronary arteries, presence of epicardial fat and or significantly high impedance as in coronary venous system or small coronary venous branches that prevent advancing of the ablation catheter to the target site. In these situation, the ablation can be performed indirectly by targeting adjacent sites, thus it is very important to precisely define the surrounding structures of the target site.

5. Ablation

As LV summit is the highest point of the LV epicardium it can be accessed directly via percutaneous pericardial puncture, but this approach usually is limited by the proximity to major coronary arteries and the presence of a thick layer of epicardial fat and should be considered if other strategies failed and ECG pattern and the activation mapping suggest an origin from the accessible epicardial area. Santegali et al [

9] reported a total of 23 consecutive patients with VAs arising from the LV summit who underwent percutaneous epicardial instrumentation for mapping and ablation because of unsuccessful ablation from the coronary venous system and multiple endocardial LV/right ventricular sites. Successful epicardial ablation was achieved in only 5 (22%) patients. A Q-wave ratio of >1.85 in aVL/aVR, a R/S ratio of >2 in V1, and absence of q waves in lead V1 was associated with successful epicardial ablation [

9].

Alternatively, LV summit can be mapped and ablated using the stepwise and sequential approach. This approach is the cornerstone of LV summit ablation [

6,

7]. It is based on anatomical approach if the earliest site can not be directly ablated due to close proximity to coronary arteries or if there is no earliest found after detailed mapping as all sites found equally early suggesting intramural origin.

LVS VAs can be targeted from the coronary venous system (GCV/AIV, septal veins) if early activation is found. Ablation should be attempted within the venous system If the earliest activation is recorded at the GCV/AIV and energy can be safely delivered [

6]. Safe distance (at least 5 mm ) from coronary artery should be confirmed by coronary angiography. Endocardial Ablation maybe be performed sequentially from adjacent structures such as the LCC, LVOT endocardium just below the aortic cusps, aorto mitral continuity , anteroseptal RVOT, or pulmonic cusps which ever is earliest and/or opposite to the earliest epicardial site in case of failure due to deep intramural site, in ability to deliver energy within the coronary venous system due to proximity to coronary arteries , high impedance, and or small vein diameter or if the earliest activation is recorded at a septal venous perforator. Importantly, safe distance from LCC should be confirmed as needed based on coronary angiogram, integrated CT scan or ICE based on institutional workflow.

For success of this "anatomical" approach, it is not mandatory to have optimal local activation time or the pace-mapping. An anatomic distance between the earliest ventricular activation site in the coronary venous system and endocardial ablation site (<13 mm) could be a predictor of a successful endocardial catheter ablation of LV summit VAs [

17]. Frankel et al [

18] described for the first time successful elimination of ventricular arrhythmias arising from the LV summit AIV region with ablation from the nearby RVOT. The anatomic separation between the earliest RVOT and AIV sites was less than 10 mm. The most anterior and leftward RVOT just under the PV was the site of successful ablation in part of patients with precordial “pattern break” in V2 suggesting an origin from the septal aspect of the LV summit [

11]. In some cases, ablation above the pulmonic valve may be needed as early activation could be present above the valve level given the anatomic proximity between the pulmonary artery and LV summit. Ablation at this site should be performed carefully using the reversed U technique to avoid damage to left coronary system.

In general, an endocardial anatomic approach for LV summit VAs is successful most commonly in the LVOT followed by the aortic cusps and rarely in the RVOT [

17]. Anecdotally, ablation of an LV summit ventricular tachycardia from the left atrium has also been reported [

19]. Jauregui Abularach et al [

8] reported that "anatomic" approach would be successful in more than half of cases.The stepwise anatomical approach was found to be feasible and effective in larger studies. Recently Enriquez et al [

20] reported stepwise anatomical approach to ablation of intramural outflow tract ventricular arrhythmias guided by septal coronary venous mapping. The intramural origin was confirmed by demonstration of earliest activation in a septal coronary vein. Radiofrequency (RF) ablation was performed from the closest endocardial site in the LVOT and/or RVOT independent of the local activation time. If there was no suppression by endocardial ablation, retrograde transvenous ethanol infusion with a single or double balloon technique was performed, targeting the earliest septal coronary vein. If venous anatomy was not suitable for ethanol ablation or if this failed, bipolar ablation was performed. In 87% of cases (n=52), endocardial ablation from the endocardial LVOT, RVOT or both was successful in eliminating the PVCs. In the remaining 8 patients, the PVCs were eliminated with ethanol infusion (n=7) and bipolar ablation (n=1). Multicenter series included 92 patients with intramural outflow tract PVCs defined by: earliest ventricular activation recorded in a septal coronary vein or ≥ 2 of the following criteria: (1) earliest endocardial or epicardial activation < 20ms pre-QRS; (2) Similar activation in different chambers; (3) no/transient PVCs suppression with ablation at earliest endocardial/epicardial site [

21]. In 32% of patients, direct mapping of the intramural septum was performed using an insulated wire or multielectrode catheter. Most patients required special ablation techniques (one or more), including sequential unipolar ablation in 73%, low-ionic irrigation in 26%, bipolar ablation in 15% and ethanol ablation in 1%. Acute PVCs suppression was achieved in 75% of patients.

RF Ablation with stepwise incremental of RF energy (target 20-40 W) is usually performed using of irrigated catheters. Irrigation is mandatory to deliver adequate power in the low-flow venous system. low-ionic irrigation which was required in 26% of 92 patients in a multicenter study with intramural outflow tract VAs can help to achieve transmural lesions [

21].

6. Special Ablation Techniques

Special techniques maybe needed in many cases after failure of standard RF ablation. Special techniques can be used as a part of stepwise/sequential approach or as a main primary technique

6.1. Prolonged Duration Ablation

The proximity of major coronary arteries and presence of fat generally precludes direct epicardial ablation. Transient suppression of VAs is well known issue after ablation. VAs may recur within few minutes after ablation indicating just heating of the tissue but not transmural lesion. An alternative strategy for targeting epicardial or intramural LVs VA is to create large lesions from adjacent locations, particularly the endocardium of the subvalvular LVOT and/or the aortic cusp region by delivering incremental RF energy over an extended duration (> 120 seconds) [

22]. Garg et el [

22] reported their experience with prolonged duration endocardial ablation strategy compared to standard ablation. For VAs suspected and/or confirmed to be originating from the LV summit region, energy was delivered from the lowest aspects of aortic cusp region and/or the subvalvular LVOT (<=0.5 cm from the valve). Lesions were typically created in clusters over the area demonstrating earliest activation and/or surrounding the site with the best pace-map matches beyond 120 seconds up to a maximum of 5 minutes, if standard RF ablation ( 60-120 seconds) was unable to consistently suppress the VAs. Power delivery was attenuated and/or terminated if rapid impedance drop, any impedance rise and/or rapidly expanding echogenicity (seen with ICE) during lesion creation was noticed. Short-term clinical success was achieved in 60% of patients with standard and in 79% of patients with prolonged duration RF ablation (P = 0.04) without differences in complications.

6.2. Bipolar Ablation

Bipolar ablation can overcome some of the problems of ablation of LV summit arrhythmias and increase a chance of achieving a transmural lesion. Bipolar RF ablation involves the application of alternating current between 2 ablation catheters positioned on opposite sites of the arrhythmogenic substrate, one connected to the active port of the RF generator (active catheter) and the second connected to the indifferent port instead of the skin dispersive “ground” patch (return catheter) [

23,

24]. Consequently, RF current flows between the distal tip of both catheters, resulting in higher current density to the myocardial tissue and increased lesion transmurality [

25]. The presence of multiple sites surrounding LV summit, which are accessible to classic ablation approaches, provides a broad spectrum of configurations for bipolar RF ablation, leaving the field clear for numerous approaches.

For anteromedial LV summit area, bipolar ablation can be performed between 2 ablation catheters : the first ablation catheter is positioned in the RVOT and serves as a return electrode during bipolar RF ablation , and the second, open irrigated ablation catheter is located in the subaortic region of LVOT. Such an approach was performed successfully in 4 patients without complications and with a notable success rate of 75% [

26]. For ablation of inaccessible LV summit (the most superior aspect of the LV summit region), bipolar RF can be anatomically performed between 2 open-irrigated ablation catheter: the first ablation catheter (acting as return electrode) is positioned in left pulmonic cusp and the second ablation catheter is located in the subaortic region of LVOT. Positioning ablation catheter into left pulmonic cusp can be performed using the reversed U- shape technique which allows positioning of the tip of the ablation catheter anatomically below the level of the proximal LAD artery [

27,

28]. This bipolar RF anatomic approach resulted in VA suppression in 5 of 7 patients with inaccessible LV summit VAs refractory to conventional RF catheter ablation without complications [

29]. For bipolar RF ablation of more lateral LV summit aspect (earliest local activation in the GCV or AIV), an active catheter is located in LVOT or RVOT at the site of earliest endocardial activation or the site anatomically closest to the earliest epicardial site , whereas a return catheter is positioned in the GCV/AIV [

23,

30,

31]. This bipolar RF ablation approach led to acute VAs elimination in all patients after failed unipolar ablation from sites of early activation (AIV/GCV, LVOT, aortic cusps, RVOT) without procedural-related complications [

23]. In general, bipolar ablation was required in 15 % of 92 patients in a multicenter study with intramural outflow tract VAs [

21].

6.3. Ethanol Infusion

Retrograde coronary venous ethanol Infusion is recently used for ablation of refractory LV summit VAs [

32,

33]. This approach requires detailed understanding of the individual coronary venous system anatomy. This approach is pioneered by Dr Valderrábano and his group [

32,

34,

35]. Briefly as described by Dr Valderrábano , when the earliest signals are detected in the region of the GCV/AIV junction after initial mapping, then if necessary vein targets can be defined by accessing the coronary sinus via the femoral vein with a sheath, through which a multielectrode catheter is used for mapping the GCV and AIV. The earliest sites in the GCV or AIV are defined. The multielectrode catheter is then removed, and a angioplasty guide catheter is advanced to perform venograms to identify suitable intramural vein branches near the earliest site. Once identified, an angioplasty wire is advanced selectively in the targeted branch and configured as a unipolar catheter by covering the wire with an angioplasty balloon leaving approximately 5 mm of the wire tip exposed. Local activation time in AIV branches and pace map correlations are used to define vein branches to be targeted based on earliest timing and best pace maps. Once a vein branch is defined as the target vein, the angioplasty wire is removed. Contrast is injected via the angioplasty balloon to assess the size of the branch and the extent of the targeted tissue reached (myocardial staining). Up to 7 injections of 1-ml ethanol followed, depending on the therapeutic response and the extent of myocardial staining. The same group have developed also a double-balloon technique for large substrate ablation [

36].

Retrograde coronary venous ethanol infusion offered a significant long-term effective treatment for patients ( 76% of patients had LV summit origin ) with drug and RF-refractory VAs based in a multicenter experience [

35]. Enriquez et al [

20] reported that ethanol infusion was needed to eliminated intramural outflow VAs in 7 out of 60 patients. Hanson et al [

21] reported that ethanol infusion was required in 1% of 92 patients in a multicenter study with intramural outflow tract VAs.

6.4. Wire Ablation

An epicardial LV summit origin is suggested when the ventricular activation time at the distal GCV or proximal AIV is earlier than other sites within the LVOT or RVOT. Mapping of the septal perforator vein using guidewire allows to distinguish VAs originating in the epicardium (earlier in GCV/AIV) from intramural foci (earlier in septal perforator) and efficiently direct the next mapping efforts accordingly. Efremidis et al [

37] reported 2 cases of RF ablation through a guidewire in the distal GCV/AIV using low energy protocols (10–20 W, impedance drop of 10 ohms for 20–30 seconds). RF was delivered by placing the proximal end of the guidewire in a saline bath along with the ablation catheter [

37]. Another case was reported in which, an angioplasty guidewire was used for successful mapping and ablation of LV summit VPCs within the distal part of GCV [

38]. In this case report, RF was delivered by leaving approximately 25 mm of wire tip exposed for ablation and by connecting the end part of the wire to the RF ablation. Finally, surgical ablation has been described as an option for patients who do not respond to endocardial and epicardial ablation [

39,

40].

7. Our Approach

All patients with outflow VAs during 2019-2024 were reviewed. Patients who found to have VAs originated from LV summit were included in this study. The diagnosis of LV summit VAs was based on ECG pattern and results of ablation. VAs with ECG patterns of inferior axis and RBBB pattern or LBBB and early precordial transition (at or less V3) or break pattern at V2 were suspected to originate from LV summit. LV summit was confirmed during procedure if earliest activation was at distal GCV or GCV-AIV junction (epicardial LV summit) or septal veins (intra mural LV summit) or if there is no earliest site found after detailed mapping or all adjacent sites found equally early suggesting intramural origin.

7.1. Procedure

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. In general electroanatomic mapping of the entire outflow tracts during point by- point catheter manipulation was performed using the CARTO (Biosense Webster) system. First mapping of RVOT and pulmonic cusps was performed, and then the coronary venous system including GCV-AIV and or septal veins. The mapping of the aortic cusps and LVOT is performed by retrograde approach. If LV summit origin was suspected based on the mentioned criteria or if standard endocardial ablation failed to suppress the VAs, then stepwise/sequential ablation approach was performed until suppression of VAs. Ablation would be performed first at GCV-AIV if early activation was confirmed at this epicardial site. If ablation within the coronary venous system was not feasible or not successful, then ablation was proceeded in adjacent sites mainly lateral LVOT and if needed LCC based on early activation and on anatomic distance from the earliest epicardial site. When intramural LV summit/septal margin of LV summit was suspected based on ECG pattern and or mapping, then ablation would be attempted at LVOT at earliest site just below aortic cusps (LCC or the interleaflet triangle below the right-left coronary junction) and if needed above the valve. If left side ablation failed or transiently suppressed the VAs, then ablation from RVOT (mainly at the most anterior and leftward part just below pulmonic valve) or the left pulmonic cusp was performed. Importantly, prolonged duration endocardial ablations are used if needed as previously described [

22]. Percutaneous epicardial ablation was used in rarely when epicardial origin was suspected and after failure of ablation from coronary venous system and endocardial ablation from LVOT/RVOT. Acute success was defined at elimination of VAs for at least 30 minutes.

7.2. Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were presented as mean and standard deviation. Categorical variables were presented as numbers and percentages.

8. Results

8.1. Patients' Characteristics

All consecutive patients with outflow VAs referred to ablation in our institute between 2019 and 2024 who eventually diagnosed to have LV summit origin were included in this cohort. A total of 38 patients were found to have VAs from LV summit origin: 37 patients had VPCs and 1 had ventricular tachycardia. Five patients were after at least 1 failed ablation. Baseline characteristics are summarized in

Table 1. Transition was seen in V1 in 15 patients, V2 in 12 patients, and V3 in 11 patients. Four patients had R wave pattern break in lead V2.

8.2. Ablation Sites

Table 2 summarizes the sites of ablation. Seventeen patients had successful ablation from LVOT below LCC or the right-left coronary junction (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). Sequential ablation at LCC and LVOT was successful in 8 out of 9 patients. Sequential ablation from LVOT/LCC and RVOT/LPC was succesful in 7 patients.

Table 2.

Sites of ablation.

Table 2.

Sites of ablation.

| |

Total= 38 |

Failure=3 |

comments |

| LVOT below LCC |

17 |

0 |

|

| LCC+ LVOT |

9 |

1 |

|

| LVOT/LCC+RVOT/LPC |

7 |

0 |

Ablation at LPC was performed in 2 patients |

| LVOT+ GCV-AIV |

2 |

1 |

|

| RVOT only |

1 |

0 |

|

| Percutaneous epicardial ablation after failure of endocardial ablation |

2 |

1 |

Endocardial ablation included LCC/LVOT |

The local endocardial electrogram at the sites of endocardial ablation preceded QRS less than 20 ms in all patients. Ablation was performed at these endocardial sites as the early activation was found to be in these sites or ablation at early activation site within coronary venous system was not found to be feasible. All patients needed prolonged endocardial ablation duration (more than 120 ms) for sustained suppression of VAs.

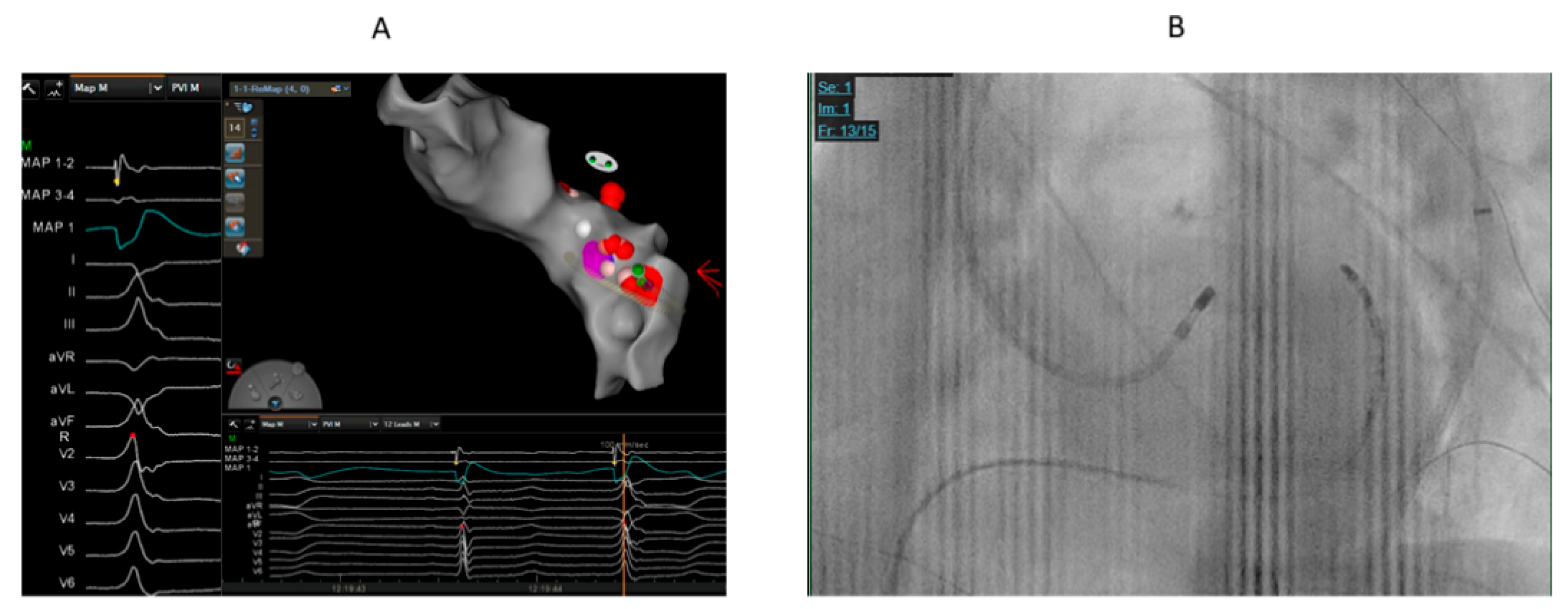

Figure 1.

68 years old male with high burden VPCs (RBBB pattern and inferior axis) and mildly reduced left ventricular function. A. The earliest activation (19 ms before QRS) was at LVOT below and lateral to left coronary cusp. We could not advance catheter to GCV-AIV. We supposed that the origin might be close to GCV-AIV. Cluster ablation for prolonged duration (240 ms) at lateral part of LVOT summit was performed that eventually eliminated the VPCs. B. The catheter ablation at successful ablation site at LVOT.

Figure 1.

68 years old male with high burden VPCs (RBBB pattern and inferior axis) and mildly reduced left ventricular function. A. The earliest activation (19 ms before QRS) was at LVOT below and lateral to left coronary cusp. We could not advance catheter to GCV-AIV. We supposed that the origin might be close to GCV-AIV. Cluster ablation for prolonged duration (240 ms) at lateral part of LVOT summit was performed that eventually eliminated the VPCs. B. The catheter ablation at successful ablation site at LVOT.

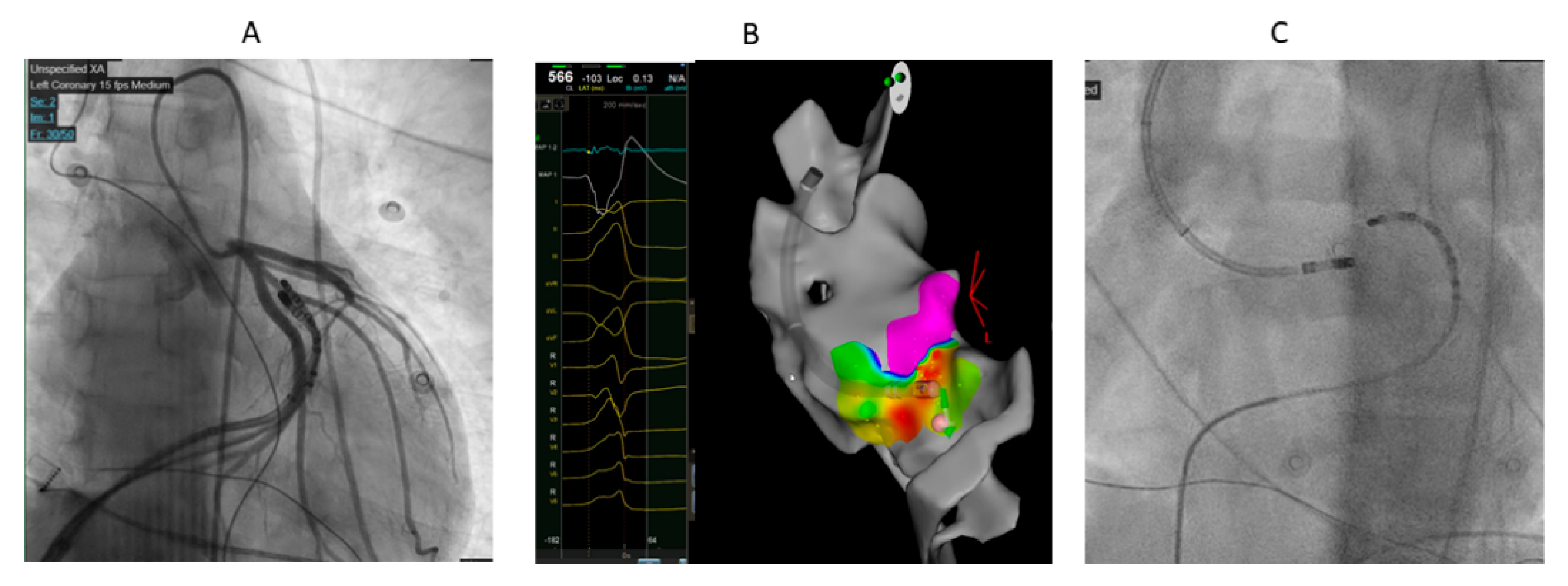

Figure 2.

33 years old male with high burden VPCs with V3 transition and inferior axis. A. The earliest activation was at GCV-AIV junction. However, ablation was judged to be unsafe in this site because of proximity to coronary arteries. Ablation at LVOT adjacent to earliest site failed to eliminate VPCs in first ablation. B. In redo procedure, prolonged duration (240 ms) anatomical ablation at LVOT adjacent to earliest site at GCV-AIV as showed by electroanatomical mapping successfully eliminated the VPCs. C. Fluoroscopic image showing the ablation catheter in LVOT adjacent to diagnostic catheter at GCV-AIV.

Figure 2.

33 years old male with high burden VPCs with V3 transition and inferior axis. A. The earliest activation was at GCV-AIV junction. However, ablation was judged to be unsafe in this site because of proximity to coronary arteries. Ablation at LVOT adjacent to earliest site failed to eliminate VPCs in first ablation. B. In redo procedure, prolonged duration (240 ms) anatomical ablation at LVOT adjacent to earliest site at GCV-AIV as showed by electroanatomical mapping successfully eliminated the VPCs. C. Fluoroscopic image showing the ablation catheter in LVOT adjacent to diagnostic catheter at GCV-AIV.

Ablation from GCV-AIV after failure of ablation from LVOT eliminated VA in 1 of 2 patients it was attempted. Ablation from RVOT only (at the anterior and leftward RVOT just under the pulmonary valve) was successful in 1 patient with R wave pattern break in V2 (Figure 3). Percutaneous epicardial ablation was attempted in 2 patients after failed endocardial ablation, but failed to eliminate the VA in one of them. Complications were not reported except pseudoaneurysm of the femoral artery treated by local thrombin injection.

8.3. Clinical Follow up

All patients who had acute suppression of VA, have sustained reduction of VA burden except one. The patient who had failed percutaneous epicardial ablation was treated with flecainide with control of VA. One patient who had failure of endocardial ablation at LCC/LVOT had significant reduction of VA burden after 1 year of follow up.

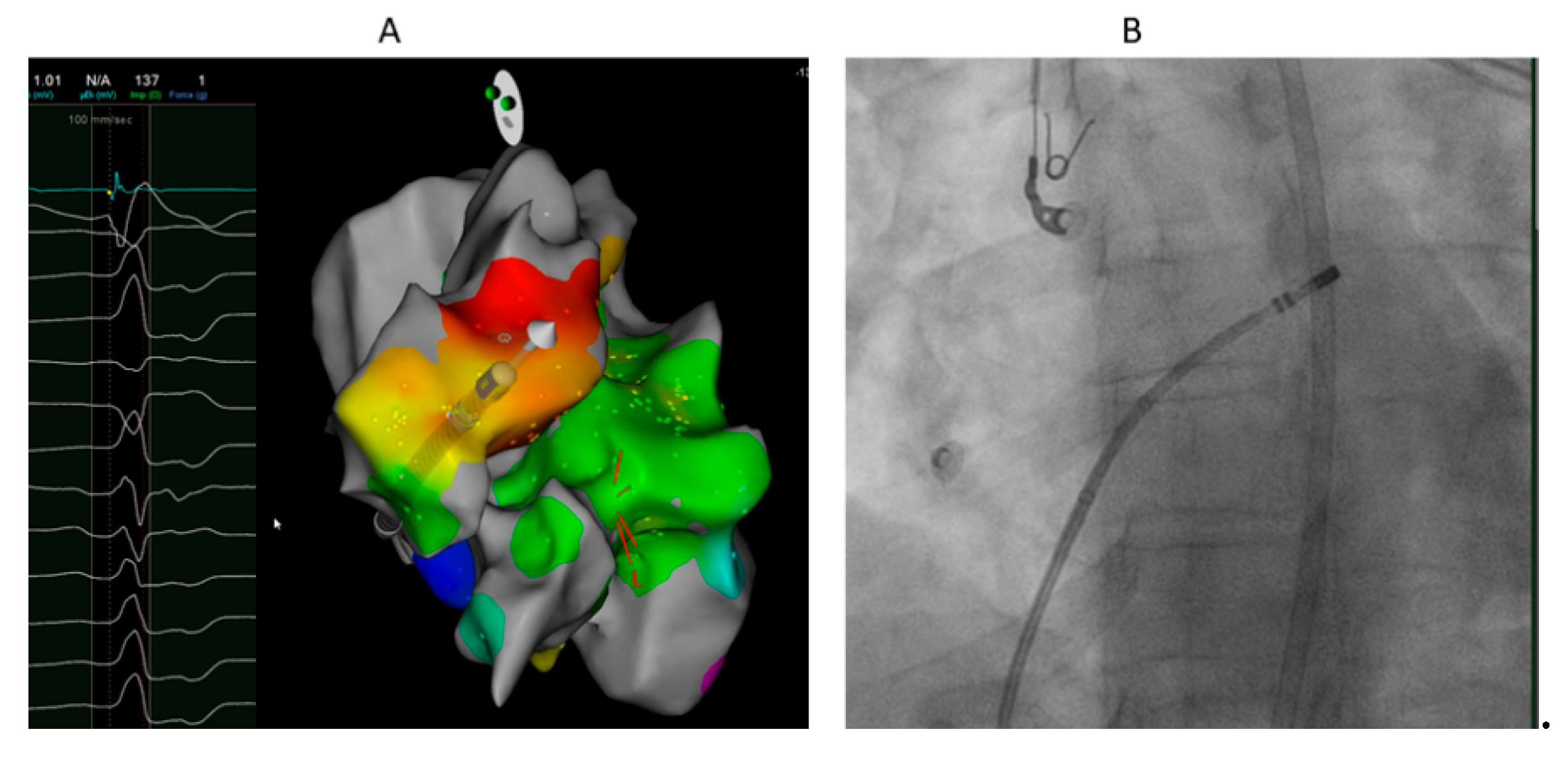

Figure 3.

40 years old female with high burden VPCs with R wave pattern break in V2. A. Local electrogram at ablation catheter located at the anterior and leftward RVOT just under the pulmonary valve preceding QRS by 19 ms which was earlier than sites from LVOT and GCV-AIV. Ablation at this site eliminated the VPCs. B. LAO fluoroscopic projection showing the ablation catheter at the most anterior and leftward RVOT just under the pulmonary valve.

Figure 3.

40 years old female with high burden VPCs with R wave pattern break in V2. A. Local electrogram at ablation catheter located at the anterior and leftward RVOT just under the pulmonary valve preceding QRS by 19 ms which was earlier than sites from LVOT and GCV-AIV. Ablation at this site eliminated the VPCs. B. LAO fluoroscopic projection showing the ablation catheter at the most anterior and leftward RVOT just under the pulmonary valve.

9. Discussion

Stepwise mapping approach and sequential ablation approach is effective to suppress VAs originated from LV summit area. Complications were not reported except vascular complication in 1 patient.

Ablation of LV summit VAs is challenging. There are many approaches and strategies reported in the literature as mentioned earlier. In general all these strategies are based on deep understanding of the anatomy of LV summit and surrounding sites. ECG patterns can give us clues to the site of successful ablation: GCV/AIV when RBBB pattern is exist, the vantage point of the interleaflet triangle below the right-left coronary junction when the pattern of left bundle branch morphology and an abrupt R-wave transition in lead V3 is exist, and the most anterior and leftward RVOT below the left pulmonic valve when R wave pattern break in lead V2 is exist . However, it is crucial to perform detailed electroanatomical mapping of all sites that are related and adjacent to LV summit as there is overlap of ECG patterns and as it is important for applying the sequential approach. The stepwise and sequential approach is the key to successful ablation regardless of the ablation technique used. Special techniques may be needed in a significant number of patients like prolonged duration as in our cohort or bipolar ablation or alcohol venous ablation as reported in other studies.

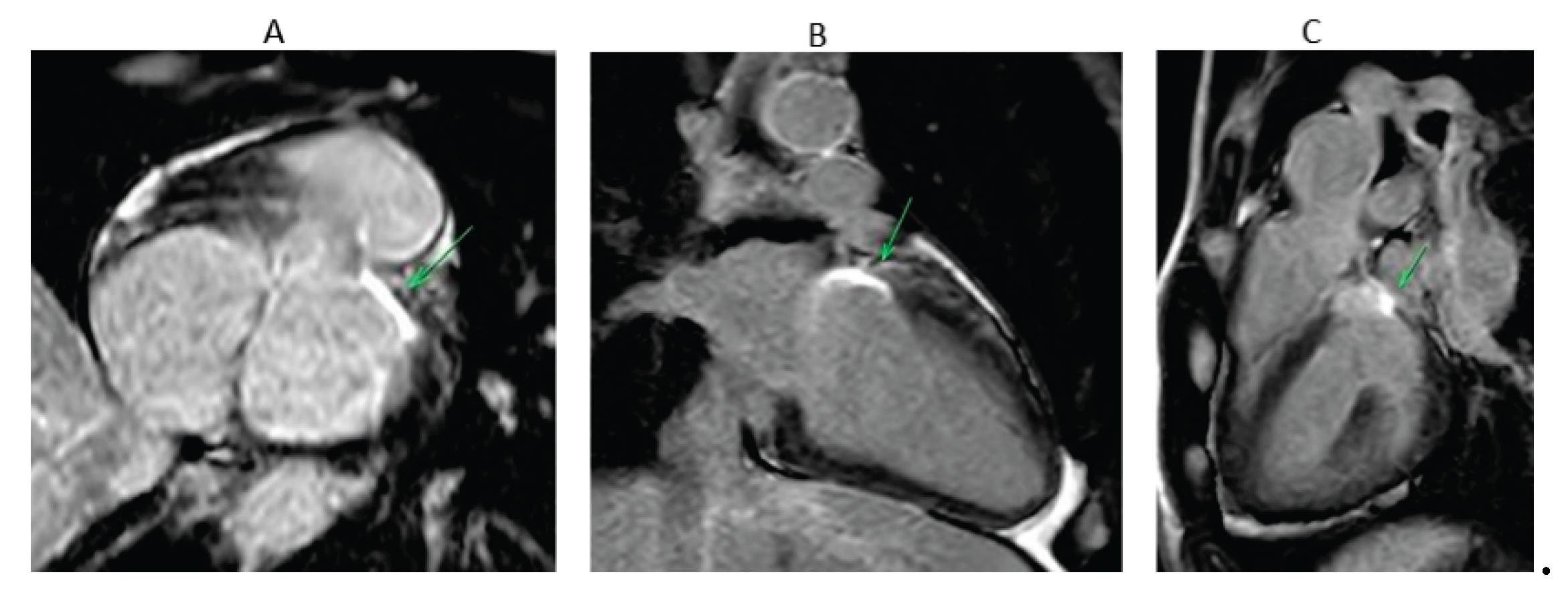

The aim of these techniques is to achieve trans mural lesion that can be detected by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (

Figure 4). Preclinical and early clinical studies have shown that late Gadolinium enhancement (LGE)-MRI identified lesion volume and depth correlate with histopathology and, in some cases, with electroanatomic mapping during repeat procedures [

41,

42]. For LV summit ablation, where catheter stability, contact force, and transmurality are often suboptimal due to anatomical constraints, such imaging may offer valuable insights into long-term lesion durability and efficacy. Although promising, LGE-MRI lesion assessment in the ventricle has yet to be validated as a routine clinical endpoint. For electrophysiologists managing LV summit VA, integrating follow-up LGE-MRI may improve procedural evaluation, guide re-intervention, and refine long-term risk stratification.

Many patients may need re ablation. Bipolar ablation and alcohol infusion within venous system are promising techniques that may be needed if other "standard approaches" fail to suppress VAs. However, these techniques need special tools and appropriate training that is not yet available in most of centers. In addition, randomized studies are needed to determine if these techniques are more effective than other techniques like prolonged duration ablation. Every center should build its own mapping strategy and ablation technique based on the availability of mapping systems, imaging tools and the expertise of operators. In addition, operators should seek to be familiar with special techniques such as bipolar ablation and alcohol infusion.

Other energy sources like pulsed field ablation (PFA) which recently emerged as a new treatment option for atrial fibrillation [

43,

44,

45,

46], may be used in the future in ablation of LV summit arrythmias. PFA is a non-thermal ablation modality highly specific for cardiac muscle, resulting in less collateral damage in other tissues including coronary arteries [47.48]. Accordingly, PFA may result in transmural lesions which will be effective in intramural foci without causing damage to coronary arteries. Benali et al [

49] reported 2 cases of PVCs originating from the LV summit region, responsible for severe PVC-induced cardiomyopathy, successfully treated with PFA using the lattice-tip catheter after multiple failed RF ablation procedures and ethanol infusion. Spenkelink et al [

50] reported a case of a patient with symptomatic epicardial LV summit PVCs underwent successful PFA via a subxiphoid approach, where RF ablation could not be used due to the proximity of the coronary arteries.

In summary, stepwise mapping and sequential ablation approach with prolonged ablation duration can suppress VAs originated from LV summit in most of patients. Randomized studies are needed to compare this approach to other techniques.

References

- Zeppenfeld, K.; Tfelt-Hansen, J.; De Riva, M.; Winkel, B.G.; Behr, E.R.; Blom, N.A.; et al. 2022 ESC guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death. Eur Heart J 2022, 43, 3997–4126. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yamada, T.; McElderry, H.T.; Doppalapudi, H.; Okada, T.; Murakami, Y.; Yoshida Yet, a.l. Idiopathic Ventricular Arrhythmias Originating From the Left Ventricular Summit. Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology 2010, 3, 616–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, T.; Kumar, V.; Yoshida, N.; Doppalapudi, H. Eccentric Activation Patterns in the Left Ventricular Outflow Tract during Idiopathic Ventricular Arrhythmias Originating From the Left Ventricular Summit. Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology 2019; 12. [CrossRef]

- Motonaga, K.S.; Hsia, H.H. Road to the Summit May Follow an Eccentric Path. Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology 2019, 12.

- Kuniewicz, M.; Baszko, A.; Ali, D.; Karkowski, G.; Loukas, M.; Walocha JAet, a.l. Left Ventricular Summit—Concept, Anatomical Structure and Clinical Significance. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enriquez, A.; Malavassi, F.; Saenz, L.C.; Supple, G.; Santangeli, P.; Marchlinski FEet, a.l. How to map and ablate left ventricular summit arrhythmias. Heart Rhythm 2017, 14, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero, J.; Gamero, M.; Alviz, I.; et al. Catheter Ablation of Left Ventricular Summit Arrhythmias from Adjacent Anatomic Vantage Points. Card Electrophysiol Clin. 2023, 15, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jauregui Abularach, M.E.; Campos, B.; Park, K.-M.; Tschabrunn, C.M.; Frankel, D.S.; Park, R.E.; et al. Ablation of ventricular arrhythmias arising near the anterior epicardial veins from the left sinus of Valsalva region: ECG features, anatomic distance, and outcome. Heart Rhythm. 2012, 9, 865–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santangeli, P.; Marchlinski, F.E.; Zado, E.S.; Benhayon, D.; Hutchinson, M.D.; Lin Det, a.l. Percutaneous Epicardial Ablation of Ventricular Arrhythmias Arising From the Left Ventricular Summit. Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology 2015, 8, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazan, V.; Gerstenfeld, E.P.; Garcia, F.C.; Bala, R.; Rivas, N.; Dixit Set, a.l. Site-specific twelve-lead ECG features to identify an epicardial origin for left ventricular tachycardia in the absence of myocardial infarction. Heart Rhythm 2007, 4, 1403–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, T.; Santangeli, P.; Pathak, R.K.; Muser, D.; Liang, J.J.; Castro SAet, a.l. Outcomes of Catheter Ablation of Idiopathic Outflow Tract Ventricular Arrhythmias With an R Wave Pattern Break in Lead V2: A Distinct Clinical Entity. Journal of Cardiovascular Electrophysiology 2017, 28, 504–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Wei, W.; Tanager, K.S.; Miele, F.; Upadhyay, G.A.; Beaser ADet, a.l. Left ventricular summit arrhythmias with an abrupt V3 transition: Anatomy of the aortic interleaflet triangle vantage point. Heart Rhythm 2021, 18, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, F.; Mathew, S.; Wu, S.; Kamioka, M.; Metzner, A.; Xue Yet, a.l. Ventricular Arrhythmias Arising From the Left Ventricular Outflow Tract Below the Aortic Sinus Cusps. Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology 2014, 7, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benhayon, D.; Cogan, J.; Young, M. Left atrial appendage as a vantage point for mapping and ablating premature ventricular contractions originating in the epicardial left ventricular summit. Clinical Case Reports 2018, 6, 1124–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marai, I.; Boulos, M.; Lessick, J.; Abadi, S.; Blich, M.; Suleiman, M. Outflow tract ventricular arrhythmia originating from the aortic cusps: our approach for challenging ablation. Journal of Interventional Cardiac Electrophysiology 2015, 45, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Sensi, F.; Miracapillo, G.; Cresti, A.; Paneni, F.; Limbruno, U. Image integration guided ablation of left outflow tract ventricular tachycardia: Is coronary angiography still necessary? . Indian Pacing and Electrophysiology Journal 2018, 18, 73–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, T. Predictors of Successful Endocardial Ablation of Epicardial Left Ventricular Summit Arrhythmias. Cardiac Electrophysiology Clinics 2023, 15, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frankel, D.S.; Mountantonakis, S.E.; Dahu, M.I.; Marchlinski, F.E. Elimination of Ventricular Arrhythmias Originating From the Anterior Interventricular Vein With Ablation in the Right Ventricular Outflow Tract. Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology 2014, 7, 984–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sosa, E.; Scanavacca, M.; d’Avila, A. Catheter Ablation of the Left Ventricular Outflow Tract Tachycardia from the Left Atrium. Journal of Interventional Cardiac Electrophysiology 2002, 7, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enriquez, A.; Yogasundaram, H.; Neira, V.; Guandalini, G.; Markman, T.; Shivamurthy Pet, a.l. Stepwise Anatomical Approach to Ablation of Intramural Outflow Tract Ventricular Arrhythmias Guided by Septal Coronary Venous Mapping. Circulation 2025. [CrossRef]

- Hanson, M.; Futyma, P.; Bode, W.; Liang, J.J.; Tapia, C.; Adams Cet, a.l. Catheter ablation of intramural outflow tract premature ventricular complexes: a multicentre study. Europace 2023; 25.

- Garg, L.; Daubert, T.; Lin, A.; Dhakal, B.; Santangeli, P.; Schaller Ret, a.l. Utility of Prolonged Duration Endocardial Ablation for Ventricular Arrhythmias Originating From the Left Ventricular Summit. JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology 2022, 8, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enriquez, A.; Hanson, M.; Nazer, B.; Gibson, D.N.; Cano, O.; Tokioka Set, a.l. Bipolar ablation involving coronary venous system for refractory left ventricular summit arrhythmias. Heart Rhythm O2 2024, 5, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Futyma, P.; Sauer, W.H. Bipolar Radiofrequency Catheter Ablation of Left Ventricular Summit Arrhythmias. Cardiac Electrophysiology Clinics 2023, 15, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.T.; Zheng, L.; Zipse, M.M.; Borne, R.T.; Tzou, W.S.; Fleeman Bet, a.l. Bipolar radiofrequency ablation creates different lesion characteristics compared to simultaneous unipolar ablation. Journal of Cardiovascular Electrophysiology 2019, 30, 2960–2967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teh, A.W.; Reddy, V.Y.; Koruth, J.S.; et al. Bipolar radiofrequency catheter ablation for refractory ventricular outflow tract arrhythmias. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2014, 25, 1093–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeger, C.; Kuck, K.; Ouyang, F. Catheter ablation of pulmonary sinus cusp-derived ventricular arrhythmias by the reversed U-curve technique. Journal of Cardiovascular Electrophysiology 2017, 28, 776–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Tang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Su, X. Pulmonary sinus cusp mapping and ablation: A new concept and approach for idiopathic right ventricular outflow tract arrhythmias. Heart Rhythm 2018, 15, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Futyma, P.; Santangeli, P.; Pürerfellner, H.; Pothineni, N.V.; Głuszczyk, R.; Ciąpała Ket, a.l. Anatomic approach with bipolar ablation between the left pulmonic cusp and left ventricular outflow tract for left ventricular summit arrhythmias. Heart Rhythm 2020, 17, 1519–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Futyma, P.; Sauer, W.H. Bipolar Radiofrequency Catheter Ablation of Left Ventricular Summit Arrhythmias. Cardiac Electrophysiology Clinics 2023, 15, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Futyma, P.; Sander, J.; Ciąpała, K.; et al. Bipolar radiofrequency ablation delivered from coronary veins and adjacent endocardium for treatment of refractory left ventricular summit arrhythmias. J Interv Card Electrophysiol.

- Flautt, T.; Valderrábano, M. Retrograde Coronary Venous Ethanol Infusion for Ablation of Refractory Left Ventricular Summit Arrhythmias. Card Electrophysiol Clin. 2023, 15, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, S.; Valderrábano, M. Venous Ethanol Ablation Approaches for Radiofrequency-Refractory Cardiac Arrhythmias. Current Cardiology Reports 2023, 25, 917–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, L.; Valderrábano, M. Retrograde venous ethanol ablation for ventricular tachycardia. Heart Rhythm 2019, 16, 478–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, L.; Lador, A.; Fuentes, S.; Da-wariboko, A.; Blaszyk, K.; Malaczynska-Rajpold Ket, a.l. Intramural Venous Ethanol Infusion for Refractory Ventricular Arrhythmias. JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology 2020, 6, 1420–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da-Wariboko, A.; Lador, A.; Tavares, L.; Dave, A.S.; Schurmann, P.A.; Peichl Pet, a.l. Double-balloon technique for retrograde venous ethanol ablation of ventricular arrhythmias in the absence of suitable intramural veins. Heart Rhythm 2020, 17, 2126–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Efremidis, M.; Vlachos, K.; Bazoukis, G.; Frontera, A.; Martin, C.A.; Dragasis Set, a.l. Novel technique targeting left ventricular summit premature ventricular contractions using radiofrequency ablation through a guidewire. HeartRhythm Case Reports 2021, 7, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xuan, F.; Liang, M.; Li, S.; Zuo, Z.; Han, Y.; Wang, Z. Guidewire ablation of epicardial ventricular arrhythmia within the coronary venous system: A case report. HeartRhythm Case Reports 2022, 8, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, E.-K.; Nagashima, K.; Lin, K.Y.; Kumar, S.; Barbhaiya, C.R.; Baldinger SHet, a.l. Surgical cryoablation for ventricular tachyarrhythmia arising from the left ventricular outflow tract region. Heart Rhythm 2015, 12, 1128–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, Z.; Moss, J.D.; Jabbarzadeh, M.; Hellstrom, J.; Balkhy, H.; Tung, R. Totally endoscopic robotic epicardial ablation of refractory left ventricular summit arrhythmia: First-in-man. Heart Rhythm 2017, 14, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mont, L.; Roca-Luque, I.; Althoff, T.F. Ablation Lesion Assessment with MRI. Arrhythmia & Electrophysiology Review 2022, 11.

- Dickfeld, T.; Tian, J.; Ahmad, G.; Jimenez, A.; Turgeman, A.; Kuk Ret, a.l. MRI-Guided Ventricular Tachycardia Ablation. Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology 2011, 4, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benali, K.; Vlachos, K.; Reddy, V.Y.; Verma, A.; Chun, J.; Andrade Jet, a.l. Pulsed field ablation for atrial fibrillation in real-life settings: Efficacy, safety, and lesion durability in patients with recurrences. Heart Rhythm 2024, 21, 962–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruwald, M.H.; Johannessen, A.; Hansen, M.L.; Haugdal, M.; Worck, R.; Hansen, J. Focal pulsed field ablation and ultrahigh-density mapping — versatile tools for all atrial arrhythmias? Initial procedural experiences. Journal of Interventional Cardiac Electrophysiology 2023, 67, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, V.Y.; Peichl, P.; Anter, E.; Rackauskas, G.; Petru, J.; Funasako Met, a.l. A Focal Ablation Catheter Toggling Between Radiofrequency and Pulsed Field Energy to Treat Atrial Fibrillation. JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology 2023, 9, 1786–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Qian, F.; Ji, S.; Li, L.; Liu, Q.; Zhou Set, a.l. Pulsed Field Ablation for Atrial Fibrillation: Mechanisms, Advantages, and Limitations. Reviews in Cardiovascular Medicine 2024; 25.

- du Pré, B.C.; van Driel, V.J.; van Wessel, H.; Loh, P.; Doevendans, P.A.; Goldschmeding, R.e.t.al. Minimal coronary artery damage by myocardial electroporation ablation. EP Europace 2012, 15, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neven, K.; van Driel, V.; van Wessel, H.; van Es, R.; du Pré, B.; Doevendans PAet, a.l. Safety and Feasibility of Closed Chest Epicardial Catheter Ablation Using Electroporation. Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology 2014, 7, 913–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benali, K.; Yokoyama, M.; Vlachos, K.; Kneizeh, K.; Monaco, C.; Sava Ret, a.l. Targeting the Left Ventricular Summit. JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology 2025, 11, 1080–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spenkelink, D.; van Wessel, H.; van Driel, V.J.; Ramanna, H.; van der Heijden, J.F. Pulsed field ablation as a feasible option for the treatment of epicardial left ventricular summit premature complex foci near the coronary arteries: a case report. European Heart Journal - Case Reports 2024, 8.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).