1. Background

Worldwide, sickle cell anaemia (SCA) is the most common type of the rare blood disorder sickle cell disease (SCD), with an estimated 300,000 new cases annually.[

1] This autosomal recessive blood disease is associated with an array of acute and chronic morbidities characterised by recurrent ill-health, progressive organ damage and shortened lifespan.[

2] Significant mortality is attributed to SCA, and new data indicate that the reported 50–90% mortality rate is excessively high.[

3,

4]

The World Health Organization (WHO) recognises SCA as a global public health problem

,[

5] particularly in Sub-Sahara Africa (SSA), where it contributes significantly to child morbidity and mortality.[

1] A recent article in

The Lancet highlighted SCD as a leading cause of under-5 deaths, and that the burden of disease is almost 11 times higher than previously thought.[

6] Moreover, the global burden of SCA is expected to rise because of improved survival in high-prevalence, low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) and owing to population migration to high-income countries (HICs).[

7]

Healthcare professionals (HCPs) play vital roles providing care to SCA patients who typically present with anaemia plus frequent episodes of pain, life-threatening infections, jaundice, and stroke. Moreover, Delgadinho et al.

, described how genetic polymorphisms influence SCA phenotype.[

8] While some patients can suffer from osteonecrosis, strokes, multiple pain crises and usually require frequent hospitalisations, others only have mild anaemia and may not suffer from any complications for decades.[

8] Misconceptions and inadequate knowledge about SCA are an important barrier to providing appropriate care and support for patients.[

9]

To date, there has been limited published research on the level of knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) towards SCA among HCPs. KAP studies can provide information on what is known, considered, and done in relation to SCA and identify specific gaps that may influence the quality of life (QoL) of patients and their caregivers. In Nigeria, for example, good knowledge of SCA among HCPs, particularly regarding associated complications, have been reported.[

10] Similarly, high awareness among HCPs have been reported in Nigeria.[

11,

12] However, in some other countries (including Brazil, Ghana, Great Britain, Nigeria, and Saudi Arabia) knowledge of the treatment and management of SCA by HCPs is poor.[

13,

14,

15,

16,

17] Considering the clinical variability of this disease, studies point to the need for training healthcare workers to increase awareness, correct misconceptions of SCA[

14] and improve management.[

13,

18] Furthermore, the mixed report in Nigeria emphasises the need for country-specific information to educate HCPs about the dangers of the disease in order to help SCA patients maintain and improve their well-being; and the findings of research conducted in other countries cannot be simply applied by the Ministry of Health (MINSA; Ministério da Saúde) in Cabinda province. Assessing the KAP of HCPs is an essential step in generating evidence to inform the development of appropriate and culturally adapted interventions to support SCA patients.

Angola has one of the highest birth-rates of children with SCA in sub-Saharan Africa,[

7] with an estimated 12,000 children born with SCA annually.[

19] Cabinda province is an exclave of Angola surrounded by the Democratic Republic of Congo and the Republic of Congo, and clinical services for children and their families are limited. This region is among the most severely affected in Angola because of insufficient local services and specialists. As shown in this study, there is little or no evidence on HCPs’ KAP towards SCA in Cabinda.

The overall purpose of this study was to support and inform service provision regarding establishing an autonomous and functional SCA unit in Cabinda. The aim was to answer the research question: How do HCPs respond to the severe effects of SCD? The specific objectives were to: 1) identify HCPs’ knowledge towards SCA and to explore factors affecting the knowledge level in Cabinda province, Angola. 2) identify HCPs’ attitudes/beliefs toward SCA in Cabinda province, Angola. 3) identify HCPs’ practice on SCA in Cabinda province, Angola.

2. Methodological Approach

Study Design and Scope

This study is part of a broader mixed methods project aimed at evaluating healthcare system readiness for SCA care in Cabinda province. The overall design included both a cross-sectional survey of HCPs and focus group discussions with various stakeholders. The survey—used for this component of the study—employed both closed- and open-ended questions to assess the KAP of HCPs. This approach is especially suited given the underfunding and disproportionate impact of SCA in low-resource settings like Cabinda; it will help identify gaps and barriers in frontline care, providing actionable insights to guide targeted training, improve clinical practices, and inform and service improvements. While the broader study includes qualitative data from focus groups, this paper reports exclusively on findings from the survey component. Focus group data will be presented in a separate publication to enable deeper exploration of system-level themes and contextual influences on SCA care. Insights from the survey alone provide a robust snapshot of individual-level perceptions and behaviours within the health workforce.

Study Setting and Data Collection

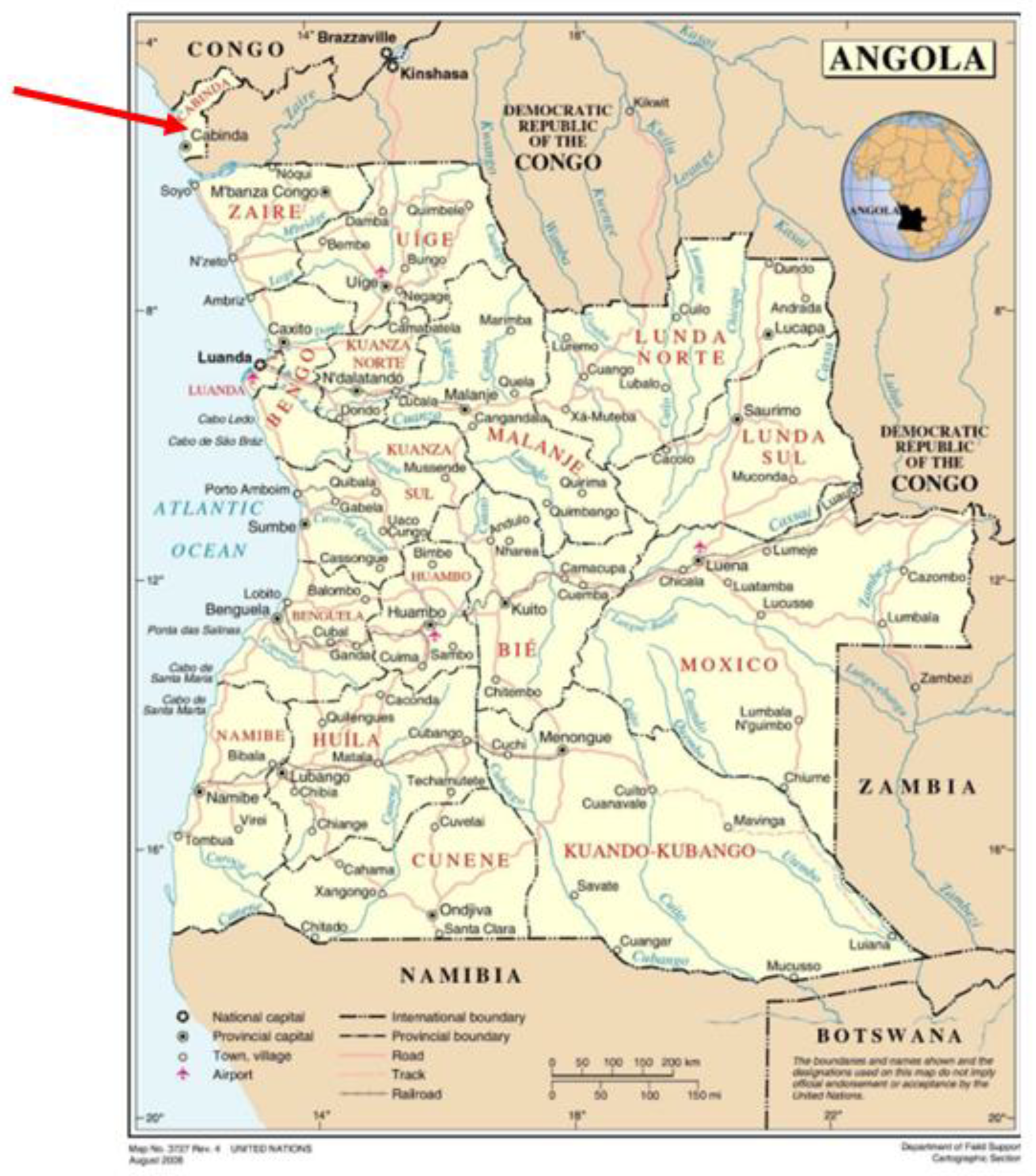

This cross-sectional study was conducted during June-September 2021 using a convenience sample of HCPs across healthcare facilities in Cabinda province. Cabinda is Angola’s smallest province, with an area of 7,290 km

2 divided into four municipalities—Belize, Buco-Zau, Cabinda and Cacongo. The estimated population in 2020 was 847,377.[

20] Participants eligible for inclusion in this study were HCPs practicing in Angola aged 18 years and above.

Figure 1 is a map of Angola, highlighting the location of Cabinda in the north.[

21] Participants were recruited after 500 questionnaires and information sheets were distributed to healthcare facilities across the province. Ethical approval was provided by the Joint Research Ethics Committee, Queen’s University Belfast and Universidade Onze Novembro, Cabinda, Angola. Participants read the consent form prior to completing the questionnaire. Returning responses was considered to constitute consent to participate in the study. All study documents were securely stored in a cabinet, and completed surveys were returned in a box located at each healthcare facility to guarantee confidentiality throughout the data collection process. The analysis was performed using de-identified data (unique ID number assigned to each respondent).

Questionnaire Design and Measures

To our knowledge, there is no validated questionnaire to investigate SCA KAP among healthcare workers. We therefore developed a fit-for-purpose questionnaire relevant to the Angolan cultural setting and SCA disease profile. The instrument was initially developed in English and back translated into Portuguese by two bilingual members of the research team. Items were reviewed for content validity and reliability by a licensed haematologist based in Texas, USA and pilot tested with five healthcare volunteers based in Cabina Province to assess clarity and redundancy. The final, paper-based, self-administered instrument took approximately 20 minutes to complete. It consisted of 12 questions about socio-demographic and occupational characteristics (age, gender, education, marital status, language, residence religious affiliation, job title, years of work experience, practising sector, position).

Quantitative Items

The closed-ended questions enabled the identification of broad patterns in knowledge and practice across respondents. To measure the levels of various aspects of KAP, a common scoring method was used. Each item in the questionnaire was awarded (‘1’ = correct response; ‘0’ = incorrect response, ‘don’t know’ or missing response). The knowledge section consisted of 37 items and covered SCA-related health outcomes, SCA manifestations and complications, control, and prevention of the complications, and management. Knowledge scores was obtained using 35 items since two questions covered awareness. The maximum possible score for the knowledge section was 35 points.

The attitudes/beliefs and practice section consisted of seven and five items, respectively. Given the influence of personal beliefs on professional attitudes and decision-making in healthcare,[

22] these items were to explore potential socio-cultural and spiritual views to better understand how these may shape practice in relation to SCA. Moreover, Angola has a set of beliefs, attitudes and health practices inherent to its cultural context.[

23] Participants’ attitude/belief toward SCA was assessed by their experiences with haemoglobin genotype status (three questions) and opinion on personal perception and decisions towards different domains of SCA (four questions). For the first three questions, ‘yes’ answers or providing a response were scored as 1. ‘No’ answers/don’t know or missing response were scored with 0. Thus, a higher cumulative score to the three questions indicated a higher familiarity with haemoglobin genotype status and more positive attitudes toward SCA. We reversed the scoring of the last four questions indicating attitudes against SCA; ‘no’ was assigned a score of 1 and ‘yes’, a score of 0, therefore higher attitude score indicated a more positive view of SCA personal perception and decisions in all 4 categories. The maximum possible score for the attitude/beliefs section was 7 points.

The items on practices were used to assess targeted actions on healthcare support services for SCA in different scenarios. The first four items had Likert-response options from strongly disagree to strongly agree. (‘1’ = strongly disagree, ‘2’ = disagree, ‘3’ = somewhat agree, ‘4’ = agree, ‘5’ = strongly agree); and the last question used ‘yes’/’no’/’don’t know’ options. We dichotomised the five-point Likert scale items into ‘yes’ (representing the subgroups “agree”, “somewhat agree”, and “strongly agree”), and ‘no’ (representing the subgroups “strongly disagree” and “disagree”); ‘yes’ scoring 1 and ‘no’ /’don’t know’ or ‘missing’ responses as 0. The maximum possible score for the practice section was 5 points. For each domain, total score was calculated and transformed into ‘percentage score’ by dividing the score with the maximum possible score and multiplying by 100. The levels of the percentage score were assessed based on a modified Bloom’s cut-off point of 60%, with each domain categorised into 2 levels instead of 3.[

24,

25,

26] A healthcare professional who scored ≥60% was considered as having “high knowledge,” “positive attitude,” and “good practice,” while one who scored <60% was considered as having “low knowledge,” “negative attitude,” and “poor practice.”

Qualitative Items

The unprompted open-ended questions that allowed for multiple responses were included to elicit deeper insights into participants’ reasoning, experiences, and beliefs. This was particularly important in uncovering how reasoning, cultural beliefs, resource limitations, and institutional constraints influence professional attitudes and behaviours. Thematic analysis using a combination of deductive codes drawn from the research questions and inductive codes generated by the data[

27] was used to analyse the qualitative items.

Data Analysis

Data were entered into Microsoft Office Excel for initial cleaning and inputted into Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) (v.27)[

28] for analysis. Cronbach’s alpha reliability was used to verify the internal consistency of the scales. A cut-off value of 0.6 was considered a good internal consistency of the items in the scale.[

29]

Descriptive statistics were generated for socio-demographic characteristics. Multiple imputation was used to deal with missing data as the pattern mixture of missing values indicated that about 9% of the socio-demographic characteristics were missing at random. The imputed datasets were used to conduct the analyses. Mean differences between sociodemographic characteristics were determined using the Mann–Whitney U-test (for variables with two levels), Kruskal-Wallis test (for variables with more than two levels) and Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons based on Dunn’s (1964) procedure.[

30] First-order analyses (i.e., Chi-square tests) was applied to prove the bias difference between the instrument items and compare the sub-samples. A combination of uni- and multivariate linear regression was performed to determine if the socio-demographic variables were good predictors of reporting knowledge of SCA using age, gender, education, experience, job title, facility, sector, marital status, language, regional language, and religious affiliation as the explanatory variables and knowledge scale as the dependent variable. A p-value of 0.05 was set as the cut-off for statistical significance.

3. Results

Internal Consistency

The analysis of internal consistency indicated that the questionnaire had a good ability to measure knowledge (Cronbach’s α-coefficient: 0.75, 35 items), attitudes (Cronbach’s α-coefficient: 0.68, 7 items) and practices about SCA (Cronbach’s α-coefficient: 0.74, 5 items). The overall internal consistency of the KAP questions was (Cronbach’s α-coefficient: 0.79, 47 items), indicating a satisfactory internal consistency. The removal of any single-item value did not significantly alter these reliability measures.

Group Characteristics

Of 500 distributed questionnaires, there were 293 (59%) responses; 82% of the sample were female. Altogether, 175 nurses, 43 technician therapists, 27 doctors, 20 clinical psychologists, 16 healthcare students and 12 other healthcare professionals completed the survey. The modal subgroup was aged 36-45 years (31%), lived in Cabinda City (69%), the capital and largest city in Cabinda province were single (79%), had completed a university-level education, had over 10 years’ work experience (41%) and did not hold any administrative or political position (90%). A pooled analysis of healthcare professionals’ characteristics is presented in

Table 1.

Awareness

In general, 98% of respondents had heard about SCA while the remaining 2% were not aware of the condition.

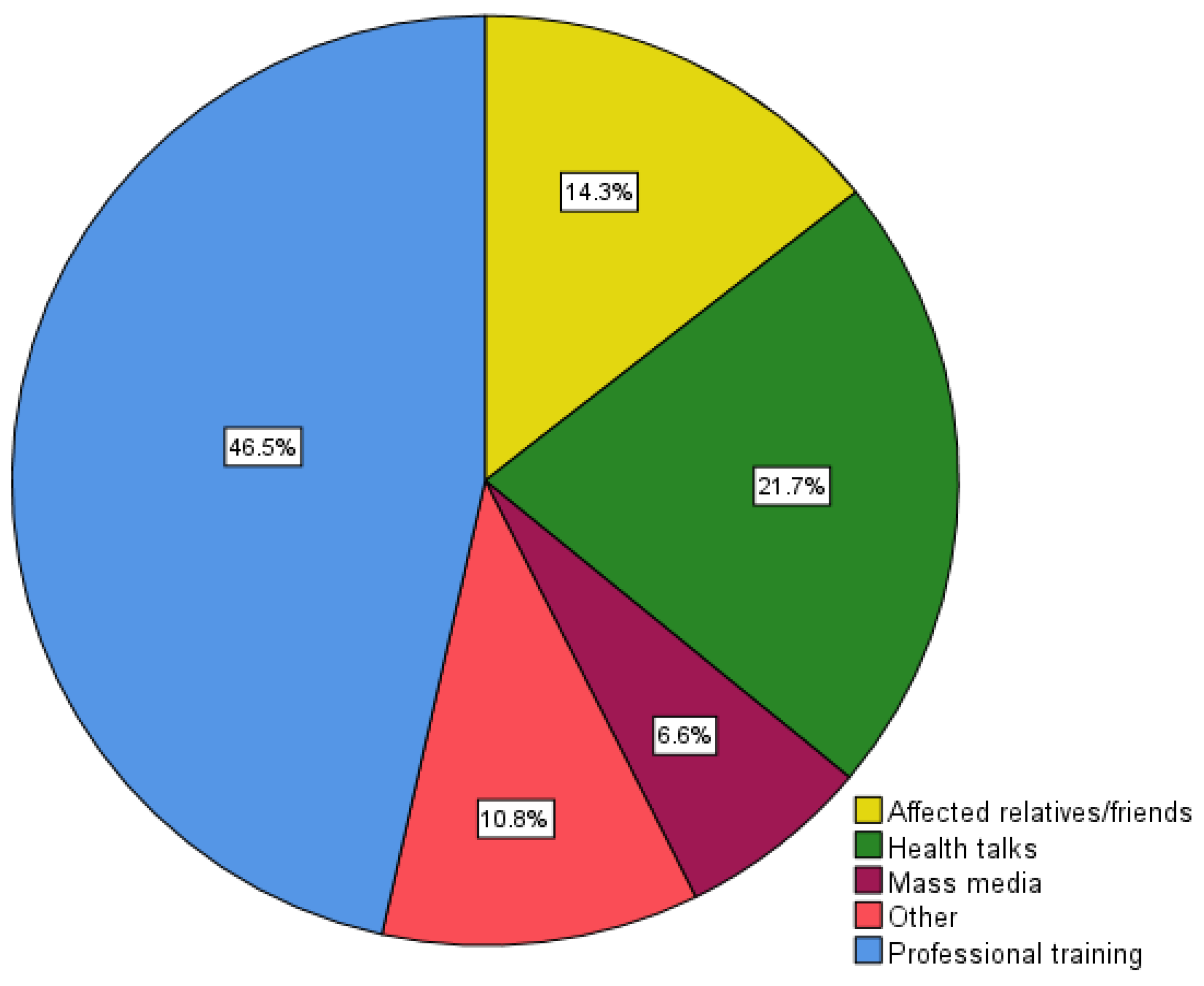

Figure 2 summarises the information sources used by respondent healthcare professionals seeking information on SCA, with professional training (47%) being the main source of knowledge, followed by health talks (22%) and affected relatives/friends (14%). The least used source was mass media (7%).

Figure 2.

Source of information towards SCA.

Figure 2.

Source of information towards SCA.

Quantitative Results

Knowledge

The average knowledge score was 14.79 (SD = 4.95, achieved score range 0–27 out of 35 points). The Mann-Whitney and Kruskal-Wallis tests showed that knowledge scores between groups were significantly different (p<0.05) in terms of profession, level of education, marital status, and religion, respectively,

Table 1. However, knowledge scores based on other background variables did not differ significantly,

Table 1. Groups with higher SCA knowledge scores included doctors (P<0.05), university-degree holders (p<0.05), those who were married (P<0.05), and Protestants/Other (versus Catholics) (P<0.05).

After categorising participants into high versus low SCA knowledge groups, the Chi-square tests resulted in significant differences in percentage knowledge scores by gender, (χ2 (1) = 6.972, p< 0.001), and profession, (χ2 (5) = 11.466, p< 0.05). Stratifying by gender revealed significant evidence of a difference in percentage knowledge score across age group (χ2 (3) = 8.938, p< 0.05) with 66% of the females having a high score compared to 34% of the males, and participants in the 26-35-year-old age group had a significantly higher score compared to females and males in other age groups. Similarly, there was a significant difference across residence (χ2 (3) = 31.534, p< 0.05), with participants living in Cabinda city having a higher knowledge compared to females and males in other municipalities. There was also a significant difference in percentage knowledge score based on position (administrative or political) (χ2 (1) = 19.391, p < 0.05); females not in an administrative or political position (95%) had higher scores compared to males in that occupational group (64%). There were no significant differences for the remaining variables.

Knowledge of healthcare professionals about SCA was low in the study group. However, 67% indicated that SCA was an important problem in Angola, but there was limited knowledge regarding painful episodes,

Table 2. Only 15% correctly answered when asked “

if sickle cell trait (SCT) carriers experience painful episodes”. When asked about the complications of SCA, only 26%, 28% and 18% knew that kidney failure, stroke and gallstones are common complications of SCA. Moreover, 98% did not know that glaucoma is not a manifestation or complication of SCA, while only 10% knew that blindness is a manifestation or complication of SCA. SCA often causes retinopathy with potential for retinal detachment or vision loss. In addition, only 55% and 39% knew that frequent blood transfusion and hydroxyurea (HU) therapy can control or prevent SCA complications, respectively. Furthermore, only 39% knew that early diagnosis and treatment can prevent complications associated with SCA. With regards SCA management, 57% knew that children with this condition should always remain hydrated, whereas only 39% knew that HU is an oral medication that can be used to improve the QoL of SCA patients. The responses are summarised in

Table 2.

Univariate linear regression showed that doctors had an almost 5-times higher SCA knowledge score than other professions (B = 4.724, p-value<0.05). For the goodness of fit, the model presented an R2 value of 0.053, meaning that profession accounted for 5% of the variability of SCA knowledge scores. The knowledge score of healthcare professionals with an undergraduate degree was twice that of those with only a secondary education (B =1.667, R2 = 3% p-value <0.05). Married healthcare professionals had 4 times higher SCA knowledge score compared to those that are single, divorced, separated, or widowed (B =3.743, R2 = 3% p-value <0.05). Multivariate linear regression to explore the association between SCA knowledge and socio-demographic variables demonstrated no significant differences.

Attitudes/Beliefs

Table 3 depicts the attitudinal response of respondent healthcare professionals’ toward SCA. Overall, the opinions of the healthcare professionals surveyed were predominantly negative regarding SCA (76% negative and 24% positive). Eighty-four percent of respondents disagreed with the statement that having a child with SCA is a form of divine punishment, suggesting that most participants did not associate the condition with religious or moral judgment. However, 26% would be in favour of ending the pregnancy if SCA was found in the embryo while it was still in the womb. While this reflects personal beliefs, such views may indirectly shape HCPs’ engagement with patients and families.

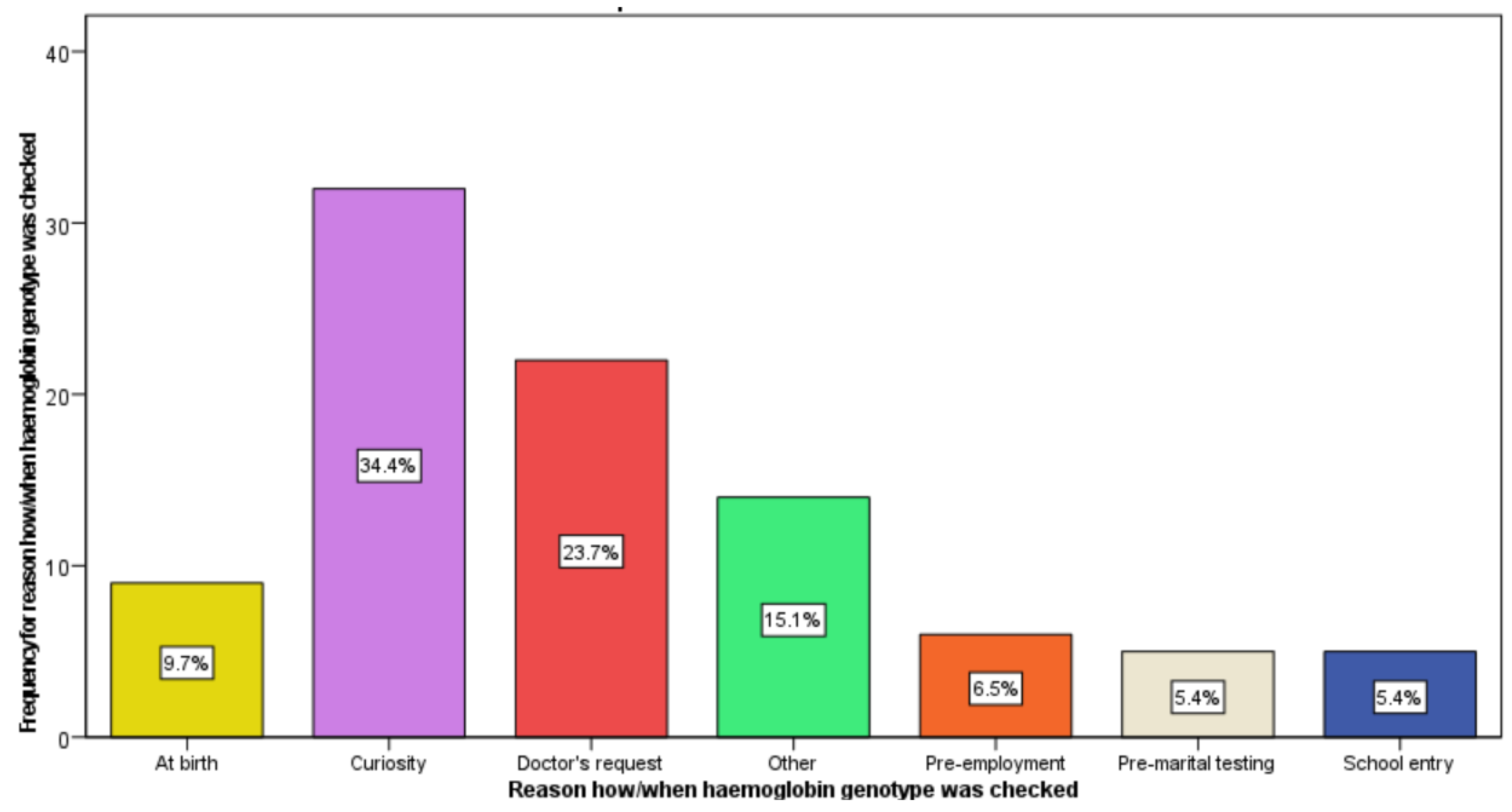

Only 22% of respondents provided their haemoglobin genotype status, with 19% reporting ‘AA’ status (i.e., the genotype with normal haemoglobin) and 3% reporting ‘AS’ status (i.e., the genotype with sickle cell trait). The most frequently given reason for healthcare professionals checking their haemoglobin genotype status was curiosity (34%) followed by doctor’s advice (24%), as a standard practice at birth (15%) and pre-employment (10%). Very few indicated it was at school entry or pre-marital testing (5% each),

Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Reason how/when haemoglobin genotype was checked.

Figure 3.

Reason how/when haemoglobin genotype was checked.

Practices

The distribution of responses for each question in this section of the questionnaire is presented in

Table 4. Over one-third of all respondents (37%) ‘agreed’ or ‘strongly agreed’ that leaders or senior managers of healthcare facilities support and openly promote SCA patient care. However, 40% ‘disagreed’ or ‘strongly disagreed’ that “

Clear and simple instructions of SCA patient care are made visible for every healthcare provider”. Overall, more respondents revealed good adherence to healthcare practices and support services for SCA in Cabinda (good: 66% vs. poor: 34%). In addition, more respondents (77%) revealed that the healthcare and support services adopt good practice measures concerning caring for SCA patients with 100% supporting establishment of a standalone clinic for SCA patients in Cabinda. This suggests that a high proportion of HCPs may be willing to improve awareness and support in caring for SCA patients. Furthermore, it was noted by the licensed haematologist involved this research that the health authorities in Cabinda had previously expressed support for the establishment of an independent SCA clinic for children in Cabinda city. This could ultimately improve the QoL for SCA patients and their families.

Qualitative Results

The process of thematic analysis of the open-ended questions identified three overarching and overlapping themes which were selected to represent the data. These themes included: Knowledge Gaps in SCA Management, Expectations of Family Responsibility and Implicit Bias, and Systemic Barriers to Good Practice.

The results highlighted the existence of four categories of knowledge gaps in SCA management, which are differentiated by their genetic literacy awareness and knowledge gaps, whether SCA occurs only in African descendants or not, SCA diagnoses in unborn babies, and whether children with SCA should always remain hydrated or not. SCA is particularly common among people whose ancestors come from sub-Saharan Africa, India, Saudi Arabia and Mediterranean countries. Diagnosis can be identified in unborn babies, and children with SCA are expected to always remain hydrated as dehydration worsens symptoms. Yet, there were some inconsistencies due to lack of genetic knowledge of SCA, testing information, and hydration and nutritional strategies to promote the health of patients who seek medical care. This indicates a potential gap in the HCP’s knowledge for effective SCA management which may affect how care is delivered or withheld in practice.

The breakthrough of relieving pain for SCA patients is found in hydroxyurea which increases the production of foetal haemoglobin and prevents clumps of the sickle-shaped cells from forming in the bloodstream. It is a known fact that a daily dose significantly decrease the frequency and severity of the pain and tissue damage they experienced. Moreover, there is a need for HCPs to know the right way to care and treat these patients on time during episodes of severe pain to prevent potential life-threatening complications and make them feel better. Despite some understanding of the need for better care for SCA patients, many respondents mentioned that there is no comparison between caring SCA care and other conditions. The main reason for this response was that “diagnostic is different, and each disease require its own care”.

Some are unaware of the real efficacy of hydroxyurea and in their opinion children with SCA are required to follow a strict diet. One respondent emphasised that “each disease require different care and treatment; in this case, SCA patients need to keep hydrated, nutritious diet and regular and controlled physical activities”. Some also expressed the view that parents should play a proactive role in recognising early signs of a sickle cell crisis and that successful SCA management depends heavily on family resources and adherence. For instance, one respondent stated, “children with SCA require more attention; parents must know impending signs of crises”, while another noted that, “children with SCA must control their diet and have money available for blood transfusion”. The statements suggest a belief in shared responsibility, but they also imply that health outcomes depend heavily on parental action, potentially overlooking the socio-economic constraints many families face in low-resource settings like Cabinda.

To understand willingness to support comprehensive care for SCA, educational concerns, perceived systemic effectiveness and general practice characteristics that might influence outcomes were examined in the qualitative data. The respondents acknowledge that limited resources make it hard to provide comprehensive care and shared their concerns on the recognised need for specialist care and facilities, quoting that establishing an independent clinic would significantly improve the QoL for SCA patients. For instance, one respondent noted: “We need more trainings about the SCA treatment and how to take care the patients,” another said, “To improve the health care and services for SCA in Cabinda it would require implementing an autonomous healthcare unit.” And another respondent highlighted that “An autonomous SCA unit in Cabinda should be the right first step in this process.”

Currently in Cabinda province, there is no specialised centre with a multi-specialist team dedicated to providing SCA patient care. Respondents felt they lacked adequate supplies and equipment to provide SCA patient care and required more professional training across healthcare units. This is reflected in some of their responses as one respondent highlighted, “Federal government needs to provide adequate healthcare resources for the health care professionals to provide better care for patients affected by SCA.” Another respondent reported the need to, “Train more professionals in this area, especially those who directly deal with these patients.” This suggests that despite the perceived structural barriers, HCPs expressed how beneficial the SCA unit would effectively improve SCA patient care and indicated their willingness to support possible actions.

4. Discussion

This cross-sectional survey provides baseline information and investigates the KAP regarding SCA among healthcare professionals in Cabinda, a province with the highest number of children testing positive for SCA in Angola.[

31] Overall, the study found poor knowledge, negative attitudes/beliefs and positive practices that could be improved with training and support for an independent clinic with the aim of delivering comprehensive care. About 98% of the study respondents had heard about SCA, suggesting a good level of awareness similar to that of studies conducted in Nigeria.[

11,

12] High awareness may be explained by high prevalence in this setting. However, this did not appear to translate to high levels of knowledge about SCA among respondents healthcare professionals in line with previous studies conducted in Brazil, Ghana, Great Britain, Nigeria, and Saudi Arabia;[

13,

14,

15,

16,

17] and is in contrast with one study conducted in Nigeria.[

10]

Regular training for healthcare professionals is paramount to quality management of SCA. Diniz et al., (2019) highlighted the positive impact on the acquisition of knowledge by professional healthcare providers following participation in a distance education course on SCD.[

32] It is expected that healthcare professionals require high-level competence to improve quality of care for people with SCD.[

33] Thus, healthcare professionals’ suboptimal knowledge regarding SCA may contribute to the increased economic and morbidity burden. For instance, there was inadequate knowledge about HU, a proven disease-modifying treatment to reduce morbidity and mortality.[

34] This may be the result of lack of HU treatment available for SCD in Angola. Furthermore, low levels of basic knowledge found in this study are consistent with reports from other groups in relation to the treatment and management of SCA among healthcare professionals.[

14,

15] These results point to a need for health authorities and policymakers to develop cost-effective strategies to increase awareness with regards to management and treatment to reduce pain and improve the QoL of patients. This will further help in prevention of complications in SCA patients and improve clinical management of the condition.

Although it seems obvious that there is a significant difference in knowledge based on education and profession, the difference based on marital status may be explained by information shared among married individuals or by living with other affected relatives as well as experience gained while caring for SCA patients. There is also a need to consider the cultural background of Angola. Under the influence of religion, Angolan society is characterised by a conservative perspective with Catholicism being the majority; those of this faith had lower SCA knowledge.[

35] It can also be argued that increased knowledge of SCA is associated with positive attitudes and increased support to reduce SCA burden. Healthcare professionals who have a high level of knowledge are in a better position to promote better care for patients. Stratifying by gender indicated some differences in SCA knowledge based on age group, position (administrative or political), and residence.

Appropriate knowledge is crucial for embracing better attitudes and adopting precautionary practices to prevent and control SCA complications. In this study, respondents had negative attitude towards SCA. Only 27% have checked their haemoglobin genotype status, suggesting a negative attitude towards prevention and control of SCA. This may be a reflective of test availability or cost. About 49% of respondents would support that couples at risk of having a child with SCA be dissuaded from marriage by law. The qualitative response highlight how HCPs’ expectations of family involvement in SCA management may be shaped by implicit biases. While promoting parental engagement is important, the assumption that families can readily afford nutritious diets or cover the cost of blood transfusions may unintentionally shift the burden of care onto caregivers without acknowledging structural barriers such as poverty, limited health literacy, and weak social support systems.

Such perspectives risk reinforcing health inequities by normalising care gaps as personal shortcomings. Nevertheless, respondents had good practice towards SCA, which reflects the understanding that appropriate support and system capacity is essential for sustainable and equitable SCA service delivery. The respondents’ emphasis that more education is appropriate for SCA patient care reflects on their desire to be equipped with structured, role-specific, and context-relevant learning that would improve their clinical knowledge (e.g., pathophysiology), communication skills (e.g., genetic counselling, awareness campaigns), cultural competence (e.g., understanding stigma, religious/spiritual beliefs), and systems knowledge (e.g., using protocols). In the context of Cabinda’s under-resourced health system, these expectations underscore the need for more inclusive approaches that provide targeted education to enhance the frontline workforce’s preparedness to deliver SCA care. Evidence from existing SCA care models, including the Newborn Screening Programme and Project ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes), supports the effectiveness of structured, context-specific training.[

36,

37,

38,

39,

40] As part of the new SCA unit’s development, education should be embedded into service delivery, linked to performance evaluation, and adapted to address both clinical and cultural competencies.

The WHO recommends the establishment of dedicated centres to provide preventive care and treatment in high SCA prevalent regions.[

2,

41] All respondents supported the establishment of a standalone SCA unit in Cabinda. As SCA has a great impact on morbidity and mortality in Cabinda, it is vital that healthcare professionals across the healthcare system have adequate understanding of the disease and associated clinical competencies. Lack of knowledge about specific risk factors associated with SCA in general are the most potent barriers to access and care. This should be addressed through multi-faceted strategies with focus on specific clinical manifestations that results in complications in patients using peer-education and other community-based interventions. Appropriate patient care interventions might be achieved when healthcare professionals are knowledgeable about SCA and possess a positive attitude towards patients with SCA.

A need for increased training of healthcare professionals about SCA, particularly those who interact directly with SCA patients, was identified in the study. However, having the required resources by the MINSA and donors/ Official development assistance (ODA) is a concern; given that Angola’s total health expenditure is significantly low overall and has several challenges to achieving universal health coverage and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). To this end, in accordance with the “Luanda Declaration on Primary Health Care and Immunisation in Angola,” which mandates, among other things, a sustainable increase in equitable health financing,[

42,

43] targeted interventions focusing on training healthcare professionals in SCA management, communication, and care competencies and establishing a standalone unit are required.

Strengths, Weaknesses and Future Directions

To our knowledge, this is the first study examining what healthcare professionals in Angola know about SCA and their willingness to support the establishment of a standalone unit providing holistic SCA care. The focus on healthcare professionals makes it a highly important and relevant contribution considering the gap in research and that the disease burden greatly affects the QoL of patients in the country.

A weakness of the study is that there is no previously validated standardised tool for assessing KAP of healthcare professionals on SCA. However, the questionnaire was formulated through objectively designed investigative questions based on WHO guidelines and report on SCA.[

6] Although the survey incorporated both closed- and open-ended questions, providing a degree of methodological breadth, the depth of qualitative data was inherently limited by the format. Open-ended responses, while valuable, were often brief and lacked the nuance and elaboration typically captured through interviews or focus groups. This constrained the ability to fully explore complex attitudes, cultural influences, and experiential factors influencing practice. Nevertheless, there was a good response rate, and reliability was an acceptable average alpha value larger than 0.6 across instruments. In addition, only healthcare professionals in Cabinda province were surveyed and the results of this study may not reflect the KAP of healthcare professionals in the entire country. Given the focus on Cabinda, a hard-to-reach province in Angola with a very high prevalence rate of SCA, where practitioners may be quite different from those working in other parts of the country, the findings may not be equally relevant in other parts of the country or different low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Nonetheless, the findings from this research could aid the identification and targeting of SCA education intervention in Cabinda Province.

Future research should consider adopting a more expansive mixed methods design, such as a sequential explanatory or convergent parallel approach, combining surveys with in-depth interviews or focus groups with only HCPs. This would enable a more robust exploration of underlying beliefs, systemic challenges, and the lived experience of HCPs, particularly in under-resourced contexts like Cabinda, which will ultimately support more tailored and impactful policy and training interventions.

5. Conclusion

This study provides a relevant contribution and an opportunity for healthcare authorities and policymakers to improve the complex and systemic nature of managing SCA, a condition that remains under-recognised, underfunded, and disproportionately affects populations in low-resource settings like Cabinda. The study highlights not only gaps in HCPs knowledge but also in attitudes and practices relating to the care of patients with SCA with direct implications for service development, education, and policy. Doctors and clinical psychologists had higher mean knowledge score than nurses who are often the first healthcare professional that patients meet.

While general awareness of the condition was evident, qualitative data revealed persistent misconceptions, such as doubts around patient-reported pain, and experiential justification, including perceptions of caring for patients with SCA compared to patients with other conditions. These attitudes may influence clinical behaviour, leading to delays in pain management, inconsistent use of guidelines, and fragmented care experiences for patients. Therefore, for a structured, tiered education strategy embedded within the establishment of a dedicated SCA unit is needed. The training component should not only strengthen clinical competence but also challenge harmful attitudes, build empathy, and promote evidence-based decision-making. Culturally sensitive communication and reflective learning approaches can help address the attitudinal dimensions identified in this study that may affect care. Embedding evaluation into the rollout will ensure the model improves both provider performance and patient outcomes while fostering more equitable and consistency of care. This approach offers a practical roadmap for strengthening SCA services, informing health system planning and return on investment (ROI).

Importantly, the burden of SCA is felt most acutely among children, where delayed diagnosis, inadequate pain management, and fragmented care directly threaten health, wellbeing, and survival. Strengthening SCA services is therefore not only a response to a specific disease but a vital contribution to advancing child health equity. Ensuring early access to coordinated care, informed providers, and responsive systems will support better outcomes for children living with SCA and contribute to broader goals around child survival and quality of life in Cabinda Province.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research. This work was supported by the Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF) - Internal Pump Priming Fund (IPPF) Award. The Scottish Funding Council (SFC).

Authors’ contributions

J.C. conceived the original idea of the project and oversaw the overall direction and data collection process of the study. J.C., L.A., F.C., L. D’A., L.L. and G.A. planned and designed the study A.I. analysed the data and wrote the manuscript with supervision from L.A and D’A. All authors provided critical feedback that helped shape the research, analysis and final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Joint Research Ethics Committee of Queen’s University Belfast (QUB) and Universidade Onze Novembro (UON), Cabinda, Angola and followed the Declaration of Helsinki Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. Completing the questionnaire was voluntary and signing the consent and information sheet forms implied willingness to participate in the study.

Availability of data and materials

Data for this study is not available for sharing due to ethical restrictions. Participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly; therefore, supporting data is not available.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and are the product of professional research. They do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated institution, funder, or that of the publisher. The authors are responsible for this article’s results, findings, and content.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank and acknowledge Prof. Lesley Anderson for her input and invaluable assistance in securing the funds for this study. We are sincerely grateful for the time and effort invested by the stakeholders. We also extend our most sincere gratitude to Dr Ruben Buco, the Cabinda Provincial Head Secretary of the Ministry of Health in Angola, for his support and collaborative spirit throughout this research endeavour.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Grosse, S. D., Odame, I., Atrash, H. K., Amendah, D. D., Piel, F. B., & Williams, T. N. Sickle cell disease in Africa: a neglected cause of early childhood mortality. American journal of preventive medicine [serial online]. 2011 [cited 2023 Sep 02];182(5): 41(6), S398-S405. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S074937971100626X.

- Adewoyin, A. S. Management of sickle cell disease: a review for physician education in Nigeria (sub-saharan Africa). Anaemia [serial online]. 2015 [cited 2023 Sep 02]. Available from: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/anemia/2015/791498/. [CrossRef]

- Nnodu, O.E., Oron, A.P., Sopekan, A., Akaba, G.O., Piel, F.B., Chao, D.L Child mortality from sickle cell disease in Nigeria: a model-estimated, population-level analysis of data from the 2018 Demographic and Health Survey. Lancet Haematology [serial online]. 2021 [cited 2023 Sep 02]. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Ranque, B., Kitenge, R., Ndiaye, D.D., Ba, M.D., Adjoumani, L., Traore, H., Coulibaly, C., Guindo, A., Boidy, K., Mbuyi, D., Ly, I.D., Offredo, L., Diallo, D.A., Tolo, A., Kafando, E., Tshilolo, L., Diagne, I. Estimating the risk of child mortality attributable to sickle cell anaemia in sub-Saharan Africa: a retrospective, multicentre, case-control study. Lancet Haematology [serial online]. 2022 [cited 2023 Sep 05] Mar;9(3): e208-e216. Available from. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. Fifty-Ninth World Health Assembly. Sickle-cell anaemia Report by the Secretariat. [document on the Internet]. 2006. [cited 2023 Sep 20]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/gb/archive/pdf_files/WHA59/A59_9-en.pdf.

- GBD 2021 Sickle Cell Disease Collaborators. Global, regional, and national prevalence and mortality burden of sickle cell disease, 2000-2021: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Haematol [serial online]. 2023 [cited 2023 Sep 25]. Aug;10(8): e585-e599. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Piel, F. B., Hay, S. I., Gupta, S., Weatherall, D. J., & Williams, T. N. Global burden of sickle cell anaemia in children under five, 2010–2050: modelling based on demographics, excess mortality, and interventions. PLoS medicine [serial online]. 2013 [cited 2023 Sep 25].10(7), e1001484. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1001484. [CrossRef]

- Delgadinho, M., Ginete, C., Santos, B., Miranda, A., & Brito, M. Genotypic Diversity among Angolan Children with Sickle Cell Anemia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health [serial online]. 2021[cited 2023 Sep 25]. 18(10), 5417. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8158763/pdf/ijerph-18-05417.pdf.

- Brennan-Cook, J., Bonnabeau, E., Ravenne Aponte, C. A., & Tanabe, P. Barriers to care for persons with sickle cell disease: the case manager’s opportunity to improve patient outcomes. Professional case management [serial online]. 2018 [cited 2024 Jan 10]; (4), 213. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5981859/.

- Adeyemi, A. S., & Adekanle, D. A. Knowledge and attitude of female health workers towards prenatal diagnosis of sickle cell disease. Nigerian Journal of Medicine [serial online]. 2007 [cited 2024 Jan 10]; 16(3), 268-270. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17937168/.

- Animasahun, B. A., Akitoye, C. O., & Njokanma, O. F. Sickle cell anaemia: awareness among health professionals and medical students at the Lagos University Teaching Hospital, Lagos. Nigerian Quarterly Journal of Hospital Medicine [serial online]. 2009 [cited 2024 Jan 10];19(4). Available from: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/nqjhm/article/view/54524. [CrossRef]

- Animasahun, B. A., Nwodo, U., & Njokanma, O. F. Prenatal screening for sickle cell anemia: awareness among health professionals and medical students at the Lagos University Teaching Hospital and the concept of prevention by termination. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology [serial online]. 2012 [cited 2024 Apr 15]; 34(4), 252-256. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22538322/.

- Gomes, L. M., Vieira, M. M., Reis, T. C., Barbosa, T. L., & Caldeira, A. P. Knowledge of family health program practitioners in Brazil about sickle cell disease: a descriptive, cross-sectional study. BMC Family Practice [serial online]. 2011 [cited 2024 Apr 15]; 12(1), 1-7. Available from: https://bmcprimcare.biomedcentral.com/track/pdf/10.1186/1471-2296-12-89.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Dennis-Antwi, J. A., Opoku, S. A., & Osei-Amoh, B. Survey of educational needs of health workers and consumers in Ghana prior to the institution of newborn screening for sickle cell disease in Kumasi. Health Courier [serial online]. 1995 [cited 2024 Jan 10];19(4). 5(4), 28-32. Available from: https://www.primescholars.com/articles/healthcare-provision-for-sickle-cell-disease-in-ghana-challenges-for-the-african-context.pdf.

- Waters, J., & Thomas, V. Pain from sickle-cell crisis. Nursing Times [serial online]. 1995 [cited 2024 Jan 10];91(16), 29-31. Available from: https://europepmc.org/article/med/7731853.

- Adegoke, S. A., Akinlosotu, M. A., Adediji, O. B., Oyelami, O. A., Adeodu, O. O., and Adekile, A. D. Sickle Cell Disease in Southwestern Nigeria: Assessment of Knowledge of Primary Health Care Workers and Available Facilities. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. [serial online]. 2018 [cited 2024 Jul 24];112 (2), 81–87 Available from: https://academic.oup.com/trstmh/article-abstract/112/2/81/4951476. [CrossRef]

- Al-Suwaid, H. A., Darwish, M. A., & Sabra, A. A. Knowledge and misconceptions about sickle cell anemia and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency among adult sickle cell anemia patients in al Qatif Area (eastern KSA). International Journal of Medicine and Public Health [serial online]. 2015 [cited 2024 Jul 24]; 5(1). Available from: https://ijmedph.org/sites/default/files/IntJMedPublicHealth_2015_5_1_86_151269.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Weinreich, S. S., de Lange-de Klerk, E. S., Rijmen, F., Cornel, M. C., de Kinderen, M., & Plass, A. M. C. Raising awareness of carrier testing for hereditary haemoglobinopathies in high-risk ethnic groups in the Netherlands: a pilot study among the general public and primary care providers. BMC Public Health [serial online]. 2009 [cited 2024 Jul 24]; 9(1), 1-9. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/1471-2458-9-338. [CrossRef]

- McGann, P. T., Ferris, M. G., Ramamurthy, U., Santos, B., de Oliveira, V., Bernardino, L., & Ware, R. E.. A prospective newborn screening and treatment program for sickle cell anemia in Luanda, Angola. American journal of hematology [serial online]. 2013 [cited 2024 Jul 24]; 88(12), 984-989. Available from: http://wileyonlinelibrary.com/cgi-bin/jhome/351052. [CrossRef]

- Angola: Administrative Division (Provinces and Municipalities) - Population Statistics, Charts and Map”. Citypopulation.de. Population of provinces and municipalities in Angola. [homepage on the Internet]. No date [cited 2024 Jan 10]. Available from: https://www.citypopulation.de/en/angola/admin/.

- UNICEF Angola HP [homepage on the Internet]. No date [cited 2024 Mar 24]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/angola/o-que-fazemos-em-angola.

- de Oliveira Tavares, E. A., & Ramos, M. N. Cultural influence on Angolan maternal care of newborns and health strategies: health professionals’ perspective. Research, Society and Development [serial online]. 2023 [cited 2024 Sep 18];12(4). Available from. [CrossRef]

- Moyo, M., Goodyear-Smith, F.A., Weller, J. et al. Healthcare practitioners’ personal and professional values. Adv in Health Sci Educ [serial online]. 2016 [cited 2024 Sep 18];21, 257–286. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Bloom, B.S. Learning for mastery. Instruction and curriculum. Regional Education Laboratory for the Carolinas and Virginia, topical papers and reprints, number 1. Eval Comment [serial online]. 1968 [cited 2024 Nov];1(2):12. Available from: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED053419.

- Kaliyaperumal, K. I. E. C. Guideline for conducting a knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) study. AECS illumination [serial online]. 2004 [cited 2023 Sep 02]; 4(1), 7. Available from: https://www.v2020eresource.org/content/files/guideline_kap_Jan_mar04.pdf.

- Wahidiyat, P.A., Yo, E.C., Wildani, M.M., Triatmono, V.R., Yosia, M. Cross sectional study on knowledge, attitude and practice towards thalassaemia among Indonesian youth. BMJ Open [serial online]. 2021 [cited 2024 Dec 20];11: e054736. Available from: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/bmjopen/11/12/e054736.full.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Saldaña, J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. [cited 2025 Mar 15]; SAGE Publications Ltd ISBN 978-1-44624-736-5. 2021; p.54-65. Available from: https://www.karlancer.com/api/file/1689576529-m4EL.pdf.

- IBM Corp. IBM statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) for windows, (version 28.0). Armonk, NY, USA: IBM Corp; 2021.

- Dall’Oglio A.M., Rossiello B., Coletti M.F., et al. Developmental evaluation at age 4: Validity of an Italian parental questionnaire. J. Paediatr Child Health. serial online]. 2010 [cited 2024 Jul 24]; 46:419–26. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Dunn, O. J. Multiple comparisons using rank sums. Technometrics, [serial online]. 1964 [cited 2024 Jul 24];6, 241-252. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Angola Sickle Cell Initiative (ASCI) [document on the Internet]. Texas Children’s Hospital: no date [cited 2024 Jul 24]. Available from: https://www.texaschildrens.org/departments/global-hematology-oncology-pediatric-excellence-hope/angola-sickle-cell-initiative-asci.

- Diniz, K. K. S., Pagano, A. S., Fernandes, A. P. P. C., Reis, I. A., Pinheiro Júnior, L. G., & Torres, H. D. C. Knowledge of professional healthcare providers about sickle cell disease: Impact of a distance education course. Hematology, Transfusion and Cell Therapy [serial online]. 2019 [cited 2025 Apr 25];41, 62-68. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Dennis-Antwi, J.A., Dyson, S., Ohene-Frempong, K. Healthcare provision for sickle cell disease in Ghana: challenges for the African context. Divers Health Soc Care [serial online]. 2008 [cited 2025 Apr 25]; 5:241–254. Available from: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:21437310.

- Steinberg MH, Barton F, Castro O, et al. Effect of Hydroxyurea on Mortality and Morbidity in Adult Sickle Cell Anemia: Risks and Benefits Up to 9 Years of Treatment. JAMA. [serial online]. 2003 [cited 2025 Apr 25]; 289(13):1645–1651. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17937168/.

- Morier-Genoud, E. Introduction: Religions in Angola: History, Gender and Politics. Social Sciences and Missions [serial online]. 2015 [cited 2024 Mar 08]; 28(3-4), 211-215. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Therrell, B. L., Lloyd-Puryear, M. A., Ohene-Frempong, K., et al. Empowering newborn screening programs in African countries through establishment of an international collaborative effort. Journal of Community Genetics [serial online]. 2020 [cited 2024 Mar 25]; 11, 253-268. Available from: http://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7295888/pdf/12687_2020_Article_463.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Shook, L. M., Farrell, C. B., Kalinyak, K. A., et al. Translating sickle cell guidelines into practice for primary care providers with Project ECHO. Medical Education Online [serial online]. 2016 [cited 2025 Apr 28]; 21(1). Available from. [CrossRef]

- Kanter, J., Smith, W. R., Desai, P. C., et al. Building access to care in adult sickle cell disease: defining models of care, essential components, and economic aspects. Blood Advances [serial online]. 2020 [cited 2025 Apr 28];4(16), 3804-3813. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32785684/. [CrossRef]

- Bartolucci, P. Novel clinical care models for patients with sickle cell disease. Hematology, [serial online]. 2024 [cited 2025 Apr 28]; (1), 618-622. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11665723/. [CrossRef]

- Mosley, C., Farrell, C. B., Quinn, C. T., & Shook, L. M. A Mixed-Methods Evaluation of a Project ECHO Program for the Evidence-Based Management of Sickle Cell Disease. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health [serial online]. 2024 [cited 2025 Apr 28];21(5), 530. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38791745/. [CrossRef]

- Executive Board, 118. Thalassaemia and other haemoglobinopathies: report by the Secretariat. World Health Organisation. 2006 [cited 2025 Mar 15]; EB118/5. Available from: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/21519.

- WHO. Strengthen primary health care in Angola. 2022 [cited 2025 Mar 15]; Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/pt/countries/angola/news/reforcar-os-cuidados-de-saude-primarios-em-angola.

- UNICEF. Understanding Angola’s health & nutrition sectors: A public expenditure review. 2023 [cited 2025 Mar 15]; License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/esa/media/13401/file/UNICEF-Angola-PER-Health-Nutrition-Sectors-2023.pdf.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).