3.1. Surface Morphology of the Ni-Containing CrMoNbTaVW Thin Film

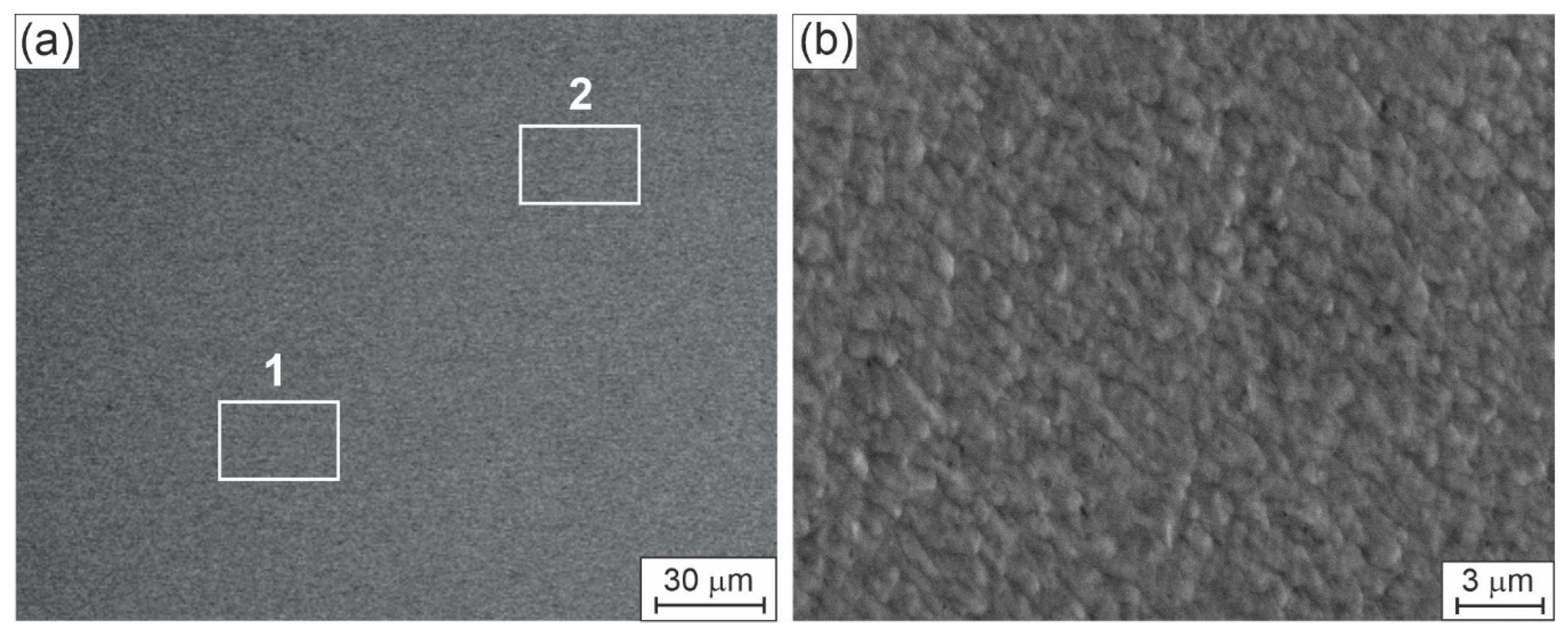

Figure 1 shows SEM images of the surface of the investigated HEA thin film on different scales.

On the large scale in

Figure 1a we observe a very smooth and homogeneous surface of the HEA thin film. This is confirmed by the SEM image on a smaller scale in

Figure 1b: it is clearly visible, that the thin film exhibits a surface topography with significant growth features, i.e. a homogeneous, dense columnar structure is indicated. This is supported by further TEM observations (see below Figs. 3 and 4c), which clearly show that the grains in the HEA thin film are columnar with diameters up to few hundred nm. These columnar grains end at the thin film surface and form the topography observed in

Figure 1b. The elemental SEM-EDX maps (not shown here) reveal a homogeneous distribution of all elements on both large and small scale. Note, that the SEM-EDX signal is obtained from a large area of the layer with a depth up to 1 μm, which leads to a bulk-like average in the determination of the elemental concentrations. The results of the EDX measurements on the surface in two different areas 1 and 2 of the HEA thin film in

Figure 1a and indicated by white rectangles with sizes of ca. 30 μm x 20 μm are presented in

Table 1.

We observe almost equal atomic concentrations of the 6 metallic elements Cr, Mo, Nb, Ta, V and W in the HEA thin film in the range 15-17 at. % and a small amount of Ni, ~ 3.6 at. %. It is obvious, that the elemental composition of the thin film deviates significantly from that of the sputter target, especially the Ni concentration of the film is much lower in the HEA thin film than in the target. An explanation of this observation can be found in the plasma conditions applied for the magnetron sputter deposition, which depends clearly on gas pressure, gas flow, substrate temperature, target-to-substrate distance and magnetic field configuration at the target.

3.2. Structure of the Ni-Containing CrMoNbTaVW Thin Film

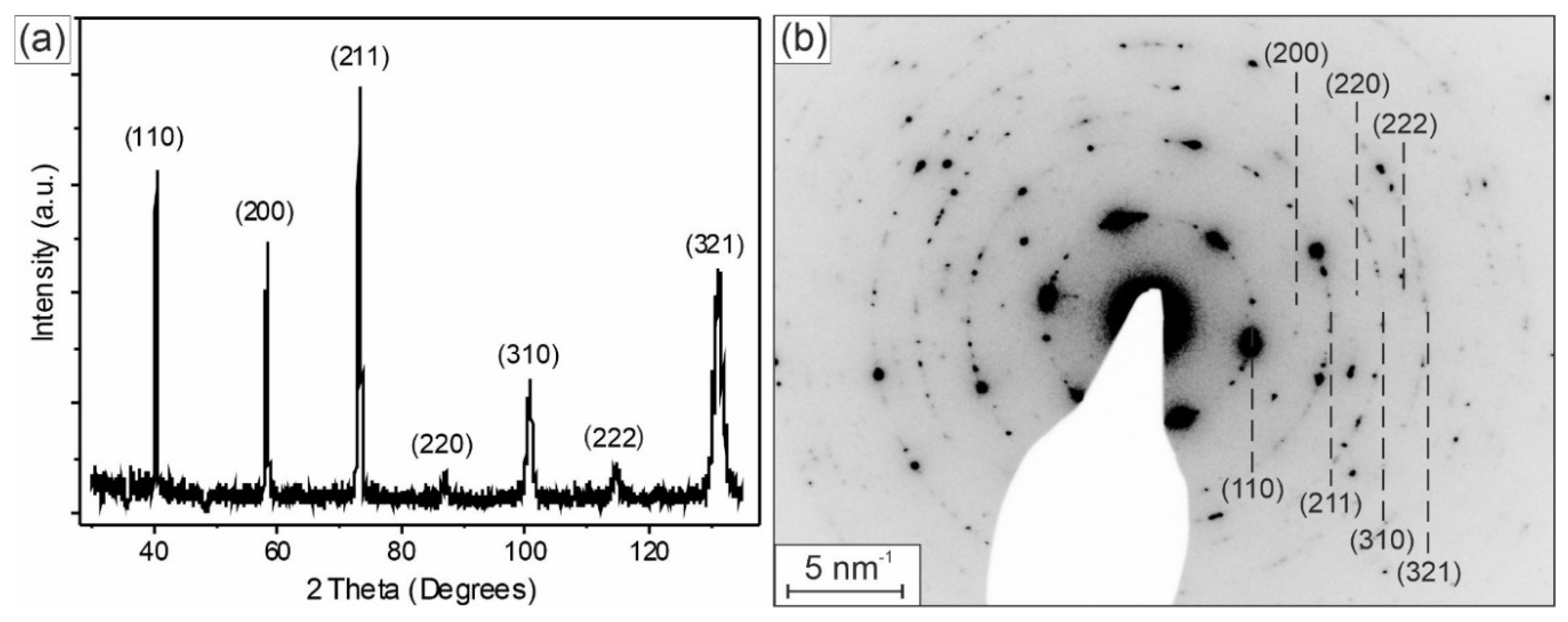

Figure 2 shows X-ray diffraction (a) and electron diffraction (b) patterns of HEA thin film.

All diffraction peaks on the X-ray diffraction pattern obtained from the Ni-containing HEA thin film in

Figure 2a and the diffraction circles and spots from the large area of the thin film cross-section TEM sample in

Figure 2b have been identified as belonging to a perfect body centered cubic (BCC) phase. The indexes of the crystal planes corresponding to the XRD peaks are indicated in

Figure 2a. Usually, for uniform homogeneous materials, the intensity of the XRD peaks decreases with increasing lattice plane indexes. Texture can be recognized as an enhancement of the relative intensity of some Bragg reflections and a reduction of others. In

Figure 2a, we observe a higher intensity of the (110), (211) and (321) peaks, which reveals a tendency to a growth with preferred orientation or even the presence of textures of these crystal planes in the investigated HEA thin film. The identical lattice planes of the BCC crystal structure are displayed and indexed in the electron diffraction pattern in

Figure 2b, obtained from large area of the cross-section TEM sample. Here, besides with strong (110) spots, we also observe many spots of (211) and (321) reflections, that also support the statement on its texture. The lattice parameter of the BCC phase, determined from

Figure 2a and

Figure 2b is

a = 0.316 ± 0.001 nm.

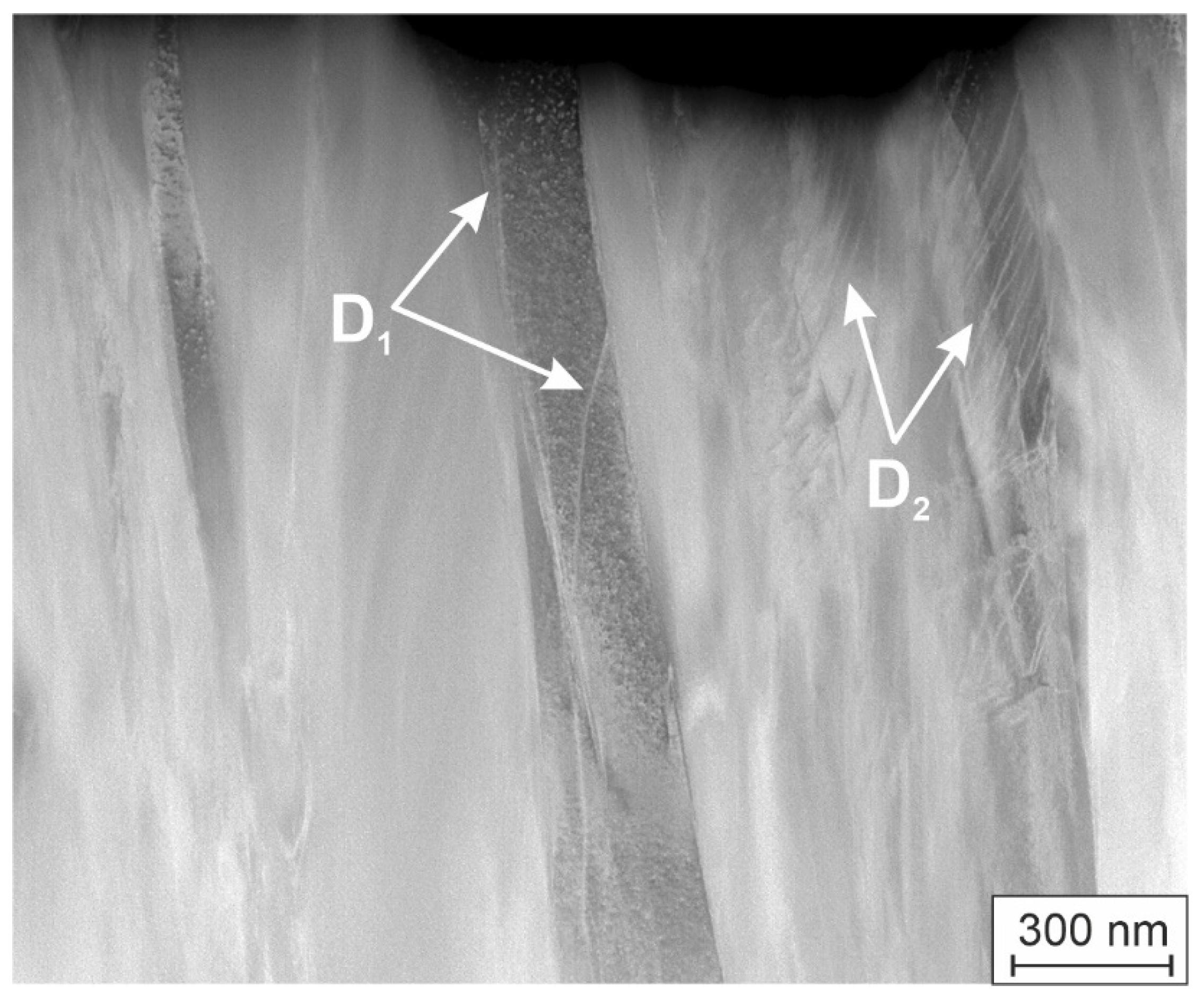

Figure 3 shows a cross-section HAADF image of the HEA thin film, that was oriented parallel to the substrate surface (horizontal edge).

The grains of the thin film are columns, extended in growth direction but not exactly perpendicular to the substrate surface. The width of the grains is changed in the growth direction and reaches a few hundred nm. This geometrical appearance of the V-shaped columnar grains matches well the growth of magnetron sputtered thin films. Further, we observe dislocations inside the grains. These are single dislocations inside the grains (please see a grain in

Figure 3 on the left side with dislocations indicated by white arrows and marked as D

1), while other grains contain assemblies of the dislocations (please see a grain in

Figure 3 on the right side with dislocations indicated by white arrows and marked as D

2), which are parallel and arranged in the same planes. Similar groups of dislocations in another area of the thin film are shown in Figure 6 (see below). Such phenomenon is often observed when compressive residual stresses have developed during the growth of the thin films.

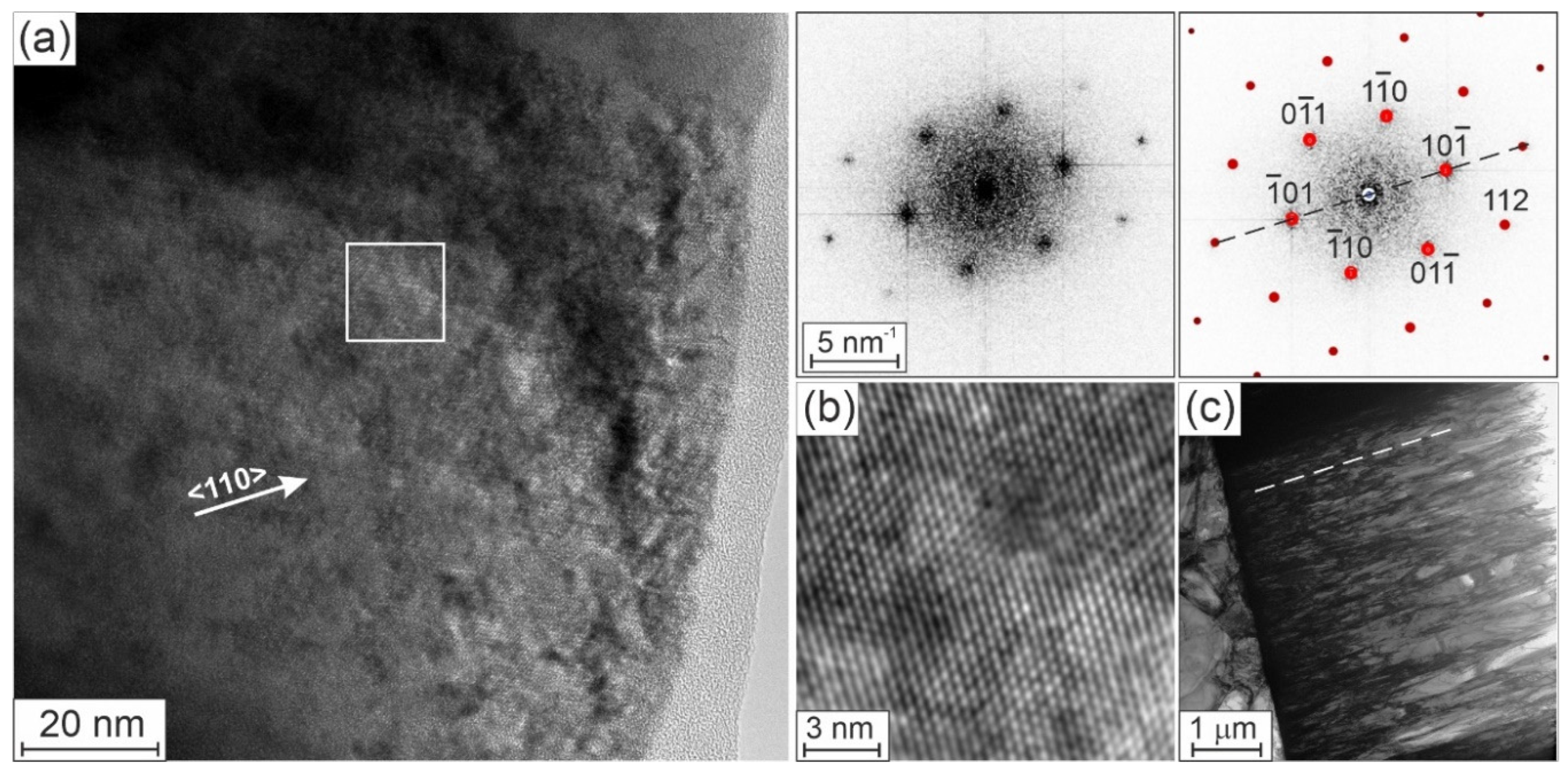

Figure 4 shows a HRTEM image of the HEA thin film with evaluated (left hand side) and simulated (right hand side) diffractograms from the area marked by the white square in the HRTEM image and the corresponding enlarged point pattern of the HRTEM image. The simulation of the diffractogram shows a BCC crystal structure close to [111]-zone axis orientation.

In

Figure 4a we see only a part of a columnar grain, which is elongated in the growth direction and cropped from the top during the FIB preparation of the TEM sample. The comparison of the HRTEM image in

Figure 4a with the identically oriented bright-field overview image in

Figure 4c shows, that the grain in

Figure 4a is elongated in <110> crystal direction of the HEA thin film.

It is known, that in pure BCC metals the {110} crystal planes have a lowest surface energy [

12]. Raabe [

13] has observed {110}, {211} and {321} rolling textures of BCC metals in his simulations and related them to the activation of slip systems. In the BCC crystal structure, which was clearly identified as the only crystalline phase of the investigated HEA thin film, there are three slip systems that can be activated during plastic deformation: {110}<111>, {211}<111>, and {321}<111>. The activation of these slip systems depends on factors such as the temperature, strain rate, chemical composition, and crystal orientations [

14]. The slip in a BCC structure occurs always in the closest packed ⟨111⟩ direction. As an example, in BCC Ta slip is predominantly on the {110} planes at low temperatures. As temperature increases, slip is observed on the {110}, {211} and {321} planes at room temperature and higher temperature. The transition temperature from the {110} to the {112} slip has been found to be between 100 K and room temperature especially for tantalum materials [

15,

16,

17]. The dominant dislocation slips on the {211} planes were experimentally observed in tantalum single crystals under compression at room temperature [

16]. The breakdown of so-called Schmid’s law (slip on {110} plans) was reported for group V and VI BCC transition metals, by numerous atomistic simulations and physically informed continuum crystal plasticity model studies [

17,

18]. The main reason for non-Schmid behaviour in transition metals was revealed to be the cores of 1/2<111> screw dislocations spreading on various {110} planes in the <111> zone.

In many component BCC crystals, consisting of group V and VI BCC refractory metals, the slip is not studied in detail. So, in the case of 4-component NbMoTaW columnar thin films [

19,

20], it has been generally observed that slip activity predominantly occurs on {110} planes at room temperature. The columns were mainly extended in <110> growth direction.

Our investigated complex HEA thin film contains 6 refractory metals with an additional small Ni amount. It has also a perfect BCC structure. The increased intensities of some XRD peaks in

Figure 2a and the presence of solid spots in the electron diffraction pattern in

Figure 2b reveal the presence of a texture of {110}, {211} and {321} crystal planes in the investigated HEA thin film. In general, a texture can be due to templating from the crystalline orientation of the substrate, minimizing the surface energy during deposition, or the competition between surfaces with anisotropic growth rates from grains with different orientations. In our case, the substrate has large grains with sizes higher than 1 μm (

Figure 4c). The different crystal planes of the substrate grains can come to the substrate - HEA thin film interface We carried out XRD analyses also of the pure substrate (not shown here) and found that one peak from crystal planes of the substrate exactly corresponds to {211} peak of the investigated HEA layer. It means, that there are crystal planes in the substrate and in the HEA thin films with the same lattice plane distance. Close to the XRD {321} peak of the HEA thin film there is also a small peak from the substrate. The other peaks are far apart. Thus, the texture of the {110} crystal planes can be explained by their lowest surface energy, meanwhile the texture of the {211} and {321} crystal planes may be caused by the “epitaxial growth” of the HEA thin film on the substrate.

From the other side, during the growth of the HEA thin film the columnar grains extend also in perpendicular direction and contact each other with different crystal planes, which leads to stress or deformation in the layer. Deformation mechanisms in BCC materials are primarily related with slip deformation. In the investigated HEA thin film we observe assemblies of dislocations in Figs. 3 and 6, which are arranged on {110} slip planes. This reveals plastic deformation inside the layer during the growth of the different textured grains. Thus, the activation of the all slip systems may play a role in the formation of {110}, {211} and {321} textures in the investigated HEA thin films.

3.2. Composition of the Ni-Containing CrMoNbTaVW Thin Film

An HAADF STEM image of the HEA thin film and elemental EDX maps are presented in

Figure 5. EDX measurements of the HEA thin film in TEM on the small scale show almost equal atomic concentrations of Cr, Mo, Nb, Ta, V and W elements of around 15-17 at. % with uniform distribution as well as we have observed in SEM on the large scale (s.

Table 1). On the Ni-map, there are regions with changing Ni-concentration, which are indicated by arrows in

Figure 5. The local measurements of Ni-concentration in the thin film are in range 0.5 at. % to 4.7 at. %. Considering the thickness averaging in TEM samples along the electron beam, regions without Ni could exist.

Note, that the constituting metals Cr, Mo, Nb, Ta, V and W originally have BCC crystal structures, while Ni has face-centered cubic crystal structure. From a thermodynamic equilibrium point of view, Ni has different solubilities with the individual metals and it may not match with the BCC crystal structure of the investigated HEA thin film. Moreover, the solubility of Ni may be low for such complex systems as the 6-elemental HEA. Considering the kinetics of thin film formation in physical vapor deposition, especially in magnetron sputtering processes (i.e. reflecting very high colling rates up to 10

13 K/s from the vapor phase), the solubility of Ni in such alloys could be enhanced. The key question is up to what concentration Ni can be dissolved in the BCC structure and whether it is energetically more favorable for Ni to be dissolved in the BCC crystal or to accumulate at the grain boundaries. These three factors may contribute to the inhomogeneity of the Ni-distribution, which we observe in elemental EDX maps in

Figure 5.

For the determination of an exact location of Ni, inside grains or at grain boundaries, an EDX analysis on larger scale was carried out. This is presented in

Figure 6.

Like in

Figure 3, in the inverted HAADF STEM image in

Figure 6 there are groups of dislocations, which are reflected by dark lines and marked by white arrows and annotated as D. In the EDX maps, beside almost the homogeneous distribution of the elements Cr, Mo, Nb, Ta, V and W, we observe a changing Ni-concentration in the range 3.35 at, % to 4.65 at. % perpendicular to the columnar grains. Two peaks of maximums of the Ni-concentration from right hand side are observed in ~ 50 nm wide regions, whereas regions with increasing Ni-concentration from left hand and decreasing Ni-concentration in middle of the linescan are more than 200 nm wide. The existence of Ni-rich areas with a small variation of only ca. 1 % with sizes comparable with the grain width observed in

Figure 6 does not allow to finally conclude about a possible Ni-segregation at the grain boundaries in the investigated HEA thin film. Note, that the distributions of Cr, Mo, Nb, Ta, V and W along the linescan (here are not shown) is also varied in the range up to 2%. Moreover, it was shown in [

11], that the solubility of Ni in similar, but only in 3 component NbMoTa refractory HEA, occurs up to 45 at. % over wide range of temperatures. Therefore, and with regard of the present XRD and TEM analyses shown, we suggest that in our investigated HEA thin film grains with a different Ni-concentration exist. The structural model for the HEA thin film of this investigation is a single-phase solid solution in BCC structure with 3.6 at. % Ni incorporated in the BCC crystal.