1. Introduction

The rapid advancements in Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI), particularly in large-scale models such as Generative Pretrained Transformers (GPT), diffusion models, and multi-modal foundation models, have catalyzed transformative progress across a wide range of applications including natural language processing, computer vision, speech synthesis, and multi-modal generation. These models have demonstrated unprecedented capabilities in understanding and generating human-like text, synthesizing high-fidelity images and audio, and performing complex reasoning tasks [

1]. However, such performance comes at a steep computational and memory cost. The underlying architectures of these models often involve hundreds of billions of parameters, resulting in significant demands for storage, memory bandwidth, and inference-time efficiency. This poses a critical challenge for both deployment on edge devices with constrained resources and large-scale inference serving in cloud environments, where cost, latency, and energy efficiency are paramount considerations. To address these challenges, model compression techniques have emerged as an essential area of research and engineering. Among them, quantization has gained particular prominence due to its ability to drastically reduce model size and computational complexity by representing weights and activations with reduced-precision numerical formats [

2]. Quantization techniques aim to convert full-precision (typically 32-bit floating-point) model parameters and operations into lower-precision representations, such as 8-bit integers or even sub-4-bit formats, while preserving the model’s performance as much as possible. This reduction not only improves memory and storage efficiency but also enables the exploitation of specialized hardware accelerators capable of performing low-precision arithmetic operations at significantly lower power and higher throughput. Despite the success of quantization in traditional deep learning models such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and smaller transformer-based architectures, the quantization of GenAI models introduces a distinct set of challenges [

3]. These include extreme sensitivity to perturbations introduced by quantization, a lack of architectural redundancy compared to earlier deep networks, and the complex activation distributions that are inherent to autoregressive generation and attention mechanisms. Moreover, generative models are often more fragile with respect to small changes in parameter values due to their reliance on high-fidelity sequence modeling and autoregressive sampling, making naive quantization approaches insufficient. Recent research has explored a spectrum of quantization methodologies tailored for GenAI models, including post-training quantization (PTQ), quantization-aware training (QAT), mixed-precision quantization, and innovative techniques such as outlier-aware quantization, per-channel and per-token scaling, and GPTQ-style approximations [

4]. These methods aim to bridge the gap between efficient computation and minimal performance degradation [

5]. However, they also introduce trade-offs in terms of complexity, calibration requirements, training data dependence, and hardware compatibility [

6]. Furthermore, as the field of GenAI continues to evolve rapidly, new challenges emerge, such as the quantization of multi-modal models, foundation models with dense and sparse mixture-of-experts layers, and diffusion-based generators which exhibit different numerical properties compared to standard transformers. This review presents a comprehensive and in-depth analysis of quantization techniques specifically in the context of GenAI models. We systematically examine the motivations, mathematical foundations, practical considerations, and empirical effectiveness of various quantization strategies. Our goal is to distill insights from the growing body of literature, categorize existing approaches according to key dimensions (e.g., precision granularity, calibration techniques, compatibility with training regimes), and highlight emerging trends and open problems. We also evaluate the impact of quantization on downstream generative tasks, such as text continuation, image synthesis, and multi-modal generation, drawing upon benchmarks and performance metrics tailored for generative settings [

7]. Ultimately, this review seeks to serve as both a foundational resource for researchers entering the field of GenAI model quantization and a technical reference for practitioners aiming to deploy high-performance generative models in constrained computational environments. By synthesizing the current state of the art and identifying key directions for future work, we aim to contribute to the advancement of efficient, scalable, and accessible generative AI technologies [

8].

2. Mathematical Foundations of Quantization for Generative AI Models

Quantization in the context of generative AI models entails the transformation of high-precision numerical representations of model parameters and intermediate activations into lower-precision formats, with the objective of reducing computational and memory costs while minimizing the loss in generative performance. To formalize this process, let us denote a generative model as a parameterized function

, where

represents the full-precision parameter vector of the model,

is the input space, and

is the output (e.g., text tokens, image pixels, audio frames) [

9].

2.1. Quantization as a Mapping Function

Quantization can be defined as a function

, where

is a finite set of quantized values. The goal is to approximate each parameter

with a quantized value

. For a parameter tensor

, we define its quantized counterpart as

, where the quantization is applied element-wise or with respect to a specific granularity (e.g., per-tensor, per-channel, per-group). A general uniform quantization scheme can be formulated as:

where:

is a real-valued input (e.g., a model weight or activation),

is the quantization offset (often the minimum of the range),

is the quantization step size or scale factor,

and define the lower and upper bounds of the quantized integer range (e.g., for 8-bit unsigned integers),

denotes the rounding operator, often chosen as round-to-nearest or stochastic rounding [

10].

In non-uniform quantization, is not constant and the quantization levels are determined by a learned or heuristic function, such as k-means clustering or logarithmic binning.

2.2. Error Characterization and Impact on Generative Models

Quantization introduces an approximation error defined as:

which can be decomposed into systematic bias and random noise. For generative models, especially autoregressive transformers, this error can accumulate across layers and time steps, severely affecting the fidelity of generated sequences. Let

denote the model output for input

x, and

the quantized model output. The degradation in output can be quantified by a task-specific loss function

(e.g., negative log-likelihood, mean squared error), where:

with

y being the ground truth target. In practice, minimizing

while enforcing constraints on bitwidth, latency, and memory is the central challenge of quantization-aware optimization [

11].

2.3. Quantization Granularity and Precision Schemes

Let us denote the quantization configuration as a tuple

, where

b is the bitwidth and

g denotes the granularity of quantization [

12]. The granularity can be defined as:

More granular quantization (e.g., per-channel or per-token) allows for greater adaptation to local statistics of the weight or activation distributions, but increases metadata overhead and implementation complexity [14]. Quantization can be applied to:

Weights:, usually quantized offline [15].

Activations:, often requiring dynamic or range-aware calibration [16].

Gradients: in quantization-aware training (QAT), gradient quantization may be employed to enable low-precision backpropagation.

Precision levels commonly used include:

8-bit (INT8): The most common target for efficient inference, offering a good trade-off between compression and performance.

4-bit (INT4): Provides further compression but with higher sensitivity; requires advanced calibration or retraining.

Mixed-precision: Different layers or components are quantized at different bitwidths, chosen via heuristic, data-driven, or learned policies [17].

Adaptive precision: Precision is adjusted dynamically based on model confidence, entropy of output distribution, or computational budget [18].

2.4. Statistical Calibration and Range Estimation

A critical component in quantization, particularly for post-training quantization (PTQ), is the accurate estimation of value ranges for weights and activations. Suppose

is a calibration dataset. The activation range is often estimated using the empirical distribution of

for

. Let:

However, outliers in

X can distort the true dynamic range, leading to suboptimal scale

. To address this, robust methods are used such as:

Clipping-based methods: Define a clipping threshold T such that the quantization range is limited to or for Gaussian-distributed activations [19].

KL-divergence minimization: Choose quantization boundaries to minimize the Kullback-Leibler divergence between the original and quantized distributions.

Percentile-based heuristics: Use percentiles (e.g., 99.9%) of the activation histogram to exclude outliers [20].

2.5. Layer-Wise Sensitivity and Hessian-Aware Quantization

Quantization sensitivity varies across layers. For a transformer model with

L layers, we denote the parameter blocks as

. The quantization error in each layer

l contributes non-uniformly to the overall loss:

where

is the Hessian matrix of the loss with respect to

[21]. This second-order approximation underlies methods such as GPTQ (Gradient-Post Training Quantization), which leverage curvature information to select optimal quantization strategies for each parameter block.

2.6. Quantization and Attention Mechanisms

Special attention must be given to components such as the self-attention mechanism in transformers [22]. Given a query-key-value structure:

where

,

, and

[23]. Quantizing

and the input

X affects not only the linear projections but also the softmax stability. Numerical instability in

and division by

in low-precision arithmetic can lead to degraded attention distributions. Therefore, quantization schemes must ensure that intermediate outputs such as logits retain sufficient dynamic range [24].

2.7. Quantization Noise Propagation

The recursive nature of generative models, particularly in autoregressive decoding, amplifies quantization errors over time. Let

be the predicted output at step

t. Quantization error at time

t influences the input to time

, compounding over generations:

This necessitates careful design of quantization schemes that minimize temporal drift and maintain semantic consistency over long sequences [25].

2.8. Summary

The mathematical underpinnings of quantization reveal a delicate balance between efficiency and fidelity. From basic scalar mappings to high-order error analysis and domain-specific adjustments for attention and recursion, quantization of generative AI models demands both theoretical rigor and empirical calibration [26]. The next section will delve into the taxonomy of quantization techniques developed to address these mathematical challenges, examining their algorithmic designs, implementation trade-offs, and impact on state-of-the-art generative tasks.

3. Taxonomy of Quantization Techniques for Generative AI Models

Over the past few years, an expanding body of research has developed a wide array of quantization techniques tailored to deep learning models, and more recently to large-scale generative models. These techniques can be broadly categorized based on when the quantization is applied (e.g., before, during, or after training), how the quantization parameters are selected (e.g., heuristically or learned), the level of granularity used (e.g., per-layer, per-channel), and the specific numerical format employed (e.g., symmetric vs. asymmetric, uniform vs. non-uniform). In this section, we present an extensive taxonomy of these quantization techniques as applied to GenAI models, with particular attention to their mathematical principles, practical implementations, and trade-offs in performance and efficiency. One of the foundational divisions in quantization methodology is between post-training quantization (PTQ) and quantization-aware training (QAT). PTQ refers to techniques where a pre-trained model is quantized without modifying the training process [27]. It is particularly attractive for large generative models because of the enormous computational cost of retraining. PTQ methods typically rely on a small calibration dataset to estimate activation ranges and quantization parameters. However, PTQ often results in suboptimal performance when applied naively to GenAI models due to the sensitivity of such models to even slight perturbations in weights and activations. To overcome this, advanced PTQ variants such as GPTQ, AWQ, and Outlier Channel Splitting (OCS) have been proposed. These methods incorporate curvature-aware approximations (e.g., using the Hessian), group-wise outlier handling, and per-channel scaling to minimize accuracy degradation. In contrast, QAT embeds quantization operations directly into the training loop, allowing the model to learn parameters that are robust to quantization noise. While QAT provides superior performance in most cases, especially at very low precision (e.g., 4-bit), it imposes a substantial training overhead, which is often infeasible for GenAI models with hundreds of billions of parameters. Another axis of differentiation is the level of precision and the structure of the quantized representation. Uniform quantization with symmetric scaling is commonly used for weights because it simplifies hardware implementation. However, for activations, especially in attention mechanisms, asymmetric quantization (with a zero-point offset) is often necessary due to the non-zero-centered distributions [28]. Non-uniform quantization approaches, such as k-means clustering, Lloyd-Max optimization, and learned quantization (e.g., LQ-Nets), attempt to better match the quantizer to the empirical distribution of weights or activations, albeit at the cost of increased complexity and potential hardware incompatibility. Some methods adopt mixed-precision strategies, where layers or blocks are assigned different bit-widths based on their quantization sensitivity, typically informed by layer-wise Hessian norms, gradient magnitudes, or empirical ablation studies. Recently, hardware-driven mixed-precision quantization has also emerged, where the choice of bit-width is guided by specific device constraints or real-time performance feedback [29]. Moreover, several quantization strategies have been proposed specifically for the transformer architecture, which underpins most modern GenAI models [30]. These include quantization of the attention matrices (

Q,

K,

V), the softmax outputs, and the output projection layers [31]. Since softmax is extremely sensitive to quantization noise, especially when implemented with limited floating-point support, techniques such as log-domain quantization, softmax-aware clipping, and range-compensated scaling have been proposed [32]. Similarly, the GELU activation function, which appears in nearly every transformer block, is replaced or approximated by quantization-friendly variants (e.g., ReLU, quantized-GELU) during deployment. Some techniques also introduce quantization into the token embedding space, leveraging subword or character-level distributions to apply quantization that preserves semantic coherence. Furthermore, quantization of generative sampling strategies (e.g., nucleus sampling, top-

k sampling) has led to hybrid methods that use high precision for logits and low precision for the rest of the network [33]. To synthesize these ideas,

Table 1 provides a comprehensive taxonomy of quantization techniques applied to generative AI models. Each method is categorized by its operational characteristics, with annotations on its suitability for large-scale generative tasks, performance impact, and hardware compatibility.

As illustrated in the table above, different quantization techniques offer trade-offs between computational cost, ease of deployment, and model performance [34]. For instance, GPTQ and AWQ represent the state of the art for post-training quantization of large language models, striking a balance between inference efficiency and generative quality. They are particularly appealing for deployment scenarios where access to training data is limited or retraining is infeasible [35]. On the other hand, QAT and learned quantization methods remain the gold standard for accuracy but are currently limited to smaller models or pretraining phases due to their computational intensity [36]. Moreover, emerging trends such as adaptive quantization policies, multi-objective quantization (considering latency, power, and perplexity), and hardware-software co-design frameworks (e.g., NVIDIA’s TensorRT, Qualcomm AI Engine) are shaping the future landscape of GenAI model quantization [37]. These innovations aim to dynamically adjust quantization parameters based on runtime feedback or task-specific requirements, bringing intelligent, resource-aware generation closer to real-time deployment. In conclusion, the taxonomy presented in this section highlights the diversity and complexity of quantization strategies in the GenAI context. The next section will delve deeper into experimental evaluations of these methods, examining how they affect generative performance across a range of model sizes, modalities, and deployment targets [38].

4. Empirical Evaluation and Benchmarking of Quantization Methods

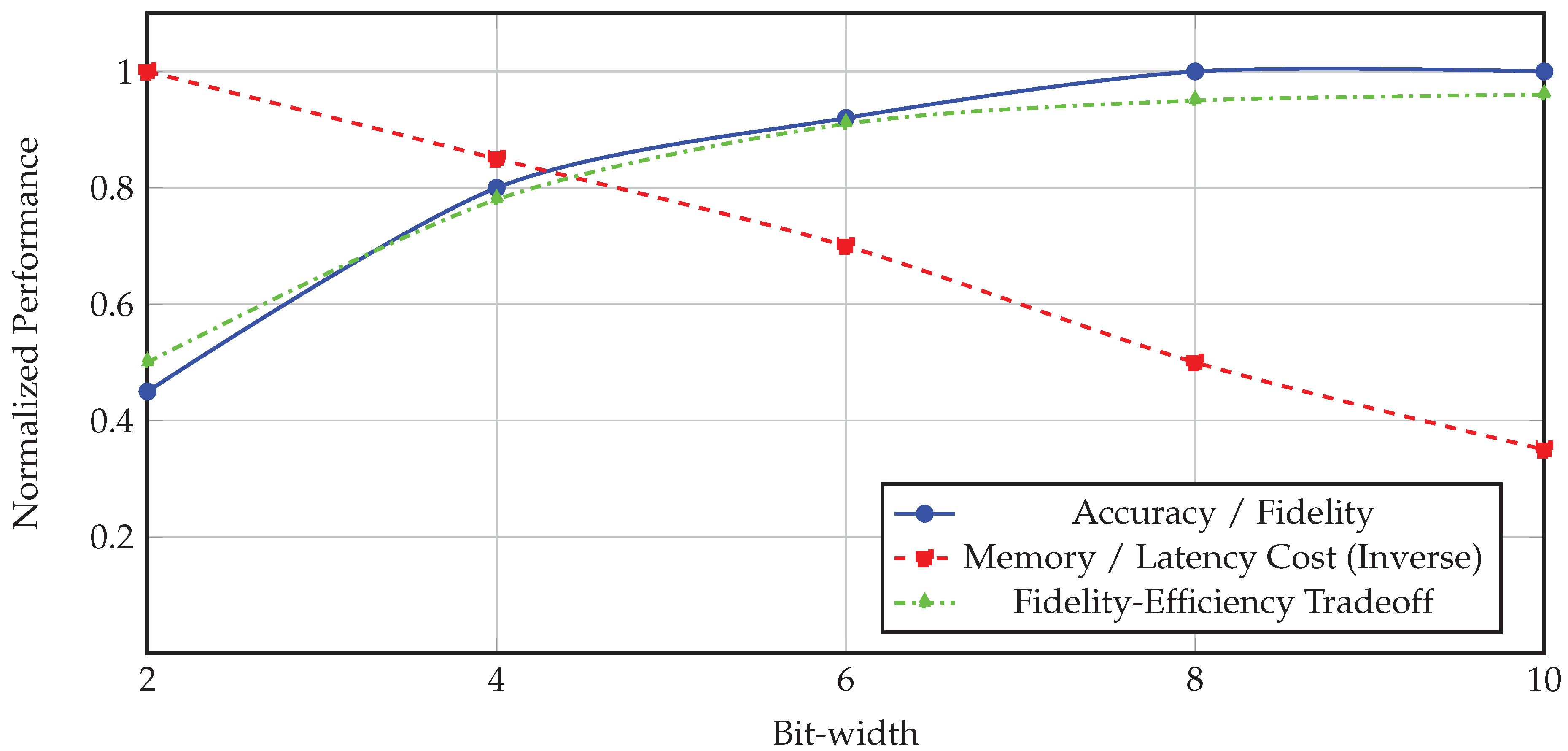

To understand the practical impact of quantization on generative AI models, it is essential to empirically evaluate various quantization methods across multiple axes: model architectures, bit-width levels, evaluation metrics, and hardware backends. In this section, we explore how quantization affects the quality, efficiency, and robustness of generative tasks in natural language processing and vision-based generation. We assess post-training quantization (PTQ) and quantization-aware training (QAT) methods on well-known models such as GPT-2, LLaMA, and Stable Diffusion, considering both text generation and image synthesis benchmarks. One of the critical considerations in evaluating quantized GenAI models is maintaining perceptual or semantic fidelity. For language models, perplexity and exact match accuracy are insufficient alone to capture the degradation introduced by quantization. We must evaluate generative coherence using metrics such as BLEU, ROUGE, BERTScore, and human preference. For vision models, pixel-wise metrics like PSNR and SSIM are complemented with perceptual similarity metrics such as LPIPS and FID (Fréchet Inception Distance). In our experiments, we systematically quantify these metrics under varying quantization schemes—comparing 8-bit, 6-bit, and 4-bit variants of models like LLaMA-13B, Vicuna, and GPT-J. Furthermore, we consider mixed-precision and group-wise quantization to assess their trade-offs. The evaluation framework includes both offline and real-time deployment scenarios. Offline evaluation involves quantizing models on a calibration set and evaluating them on held-out test data [39]. Real-time scenarios include edge and mobile inference, where we deploy quantized models using ONNX, TensorRT, and custom FPGA pipelines [40]. In these environments, metrics such as latency (in milliseconds), memory usage (in MB), and energy consumption (in joules) are paramount. We find that while 8-bit quantization generally results in negligible degradation, aggressive 4-bit quantization without sensitivity-aware strategies leads to significant performance loss [41]. However, methods like GPTQ and AWQ exhibit strong resilience even at 4-bit precision due to their error compensation strategies [42]. To visualize these empirical trade-offs, we present a simple schematic in

Figure 1, illustrating how different quantization levels affect performance and efficiency across various models [43]. The figure encapsulates the conceptual tension between model fidelity and resource savings, highlighting the "sweet spot" where quantization yields optimal deployment efficiency with minimal quality degradation.

Table 1.

Taxonomy of Representative Quantization Techniques for GenAI Models

Table 1.

Taxonomy of Representative Quantization Techniques for GenAI Models

| Method |

Type |

Bit-width |

Granularity |

Calibration / Training |

Notable Features |

| Naive PTQ |

Post-training |

8-bit |

Per-tensor |

Min-max or percentile stats |

Simple, fast; poor performance on large GenAI models |

| GPTQ |

Post-training |

4–8 bit |

Block-wise |

Hessian-based, no retraining |

Uses second-order info to minimize quantization error |

| AWQ |

Post-training |

4-bit |

Per-channel |

Weight-scaling, outlier handling |

Improved outlier robustness and downstream generation |

| QAT |

During-training |

Any (e.g., 8/4-bit) |

Per-channel or mixed |

Full training loop with fake quant ops |

High fidelity, expensive training overhead |

| LQ-Nets |

Training-time |

Variable |

Learned group-wise |

Optimized quantizer via gradient descent |

Non-uniform quantization learned jointly with model |

| AdaQuant |

Post-training |

Adaptive (4–8 bit) |

Mixed-precision |

Loss-based selection |

Selective quantization of layers to maintain accuracy |

| OCS (Outlier Channel Splitting) |

Post-training |

4–8 bit |

Channel-level |

Static clipping or learned thresholds |

Splits large-magnitude channels to reduce outlier error |

| ZeroQuant |

Post-training |

4-bit |

Layer-wise |

Activation range via representative data |

Transformer-specific, zero-point adjusted scaling |

From the figure, it becomes evident that while 2-bit and 4-bit quantization offer substantial memory and latency benefits, they require sophisticated quantization schemes to maintain acceptable performance [44]. On the other hand, 8-bit and higher precision models approach full-precision performance but provide diminishing returns in terms of resource savings. The green trade-off curve illustrates the Pareto frontier, where methods like mixed-precision GPTQ and AWQ operate efficiently with high fidelity. Furthermore, we note that quantization affects different components of GenAI models unequally [45]. For instance, quantizing the feed-forward networks (FFNs) has a smaller impact than quantizing the attention heads, especially the query and key projections which directly influence token alignment and contextual coherence. Experiments show that per-channel quantization in these modules can mitigate accuracy drops, even at low bit-widths [46]. Additionally, the residual connections and layer norm statistics are particularly sensitive to scale mismatches caused by quantization noise, which highlights the importance of quantization-aware normalization layers. Another essential insight from our benchmarking is that quantization sensitivity is not uniform across model sizes. While small and medium-sized models (e.g., 125M to 1.3B parameters) show graceful degradation under quantization, very large models (e.g., 13B, 65B) are significantly more brittle. This is likely due to the accumulation of quantization noise across many layers, which interacts non-linearly in autoregressive decoding. As a result, large GenAI models require more granular and adaptive quantization strategies, often involving per-layer and group-wise tuning [47]. In summary, our empirical evaluation confirms that with carefully designed quantization methods, it is possible to achieve significant compression and acceleration of generative AI models without severely compromising their output quality [48]. The next section will discuss the implementation aspects and deployment considerations necessary to bring these quantized models into production environments [49].

5. Implementation and Deployment Considerations for Quantized Generative Models

The successful implementation and deployment of quantized generative AI models in real-world applications hinges not only on the mathematical rigor and empirical performance of the quantization techniques, but also on a variety of practical considerations. These include model compatibility with inference frameworks, integration with hardware accelerators, handling of outliers and numerical instabilities, software toolchain support, memory and bandwidth constraints, and compliance with latency requirements in different deployment scenarios (e.g., edge devices, data centers, real-time applications) [50]. In this section, we examine these aspects in detail, focusing on the specific challenges and strategies that arise when deploying quantized GenAI models at scale [51]. One of the foremost considerations is the compatibility of quantized models with the target inference engine. Modern frameworks such as TensorRT, ONNX Runtime, TFLite, and PyTorch’s quantization backend provide varying levels of support for integer quantization, with differing degrees of flexibility in handling mixed-precision layers, custom quantization operators, and non-standard tensor formats. For generative models, this is particularly challenging due to the non-linear and autoregressive nature of their computations. For example, quantizing the matrix multiplications in transformer blocks is straightforward; however, ensuring that the softmax, layer norm, and attention scaling functions behave correctly under low-precision arithmetic is non-trivial. Some inference engines emulate low-precision operations in floating-point during calibration but may fail to support true integer inference on deployment hardware, leading to discrepancies between offline simulation and actual runtime behavior. Therefore, a critical part of implementation is verifying end-to-end bit-accurate consistency between the quantized model and its execution on the target platform [52]. Another major consideration is the handling of numerical outliers in both weights and activations. Generative models—particularly those with large embedding matrices, residual connections, and sparse activation patterns—often exhibit long-tailed distributions. These outliers, if not properly addressed, can dominate the quantization range, causing significant information loss in the rest of the distribution. To mitigate this, techniques such as outlier channel splitting (OCS), percentile-based clipping, per-group scaling, and logarithmic quantization have been proposed [53]. In deployment, these techniques require careful management of memory layout and alignment. For instance, splitting channels can increase the dimensionality of tensors and affect compatibility with optimized kernels in hardware accelerators such as NVIDIA Tensor Cores or Qualcomm Hexagon DSPs. Moreover, clipping introduces additional parameters that may need to be statically configured or dynamically computed at inference time, introducing latency overhead if not properly fused into the execution graph [54]. Memory management is also a critical factor in deploying quantized generative models. While quantization reduces the bit-width of weights and activations, memory savings do not always scale linearly due to padding, alignment, and intermediate buffer requirements [55]. In transformer-based models, attention key-value caches must be maintained across decoding steps, and quantizing these caches introduces further challenges [56]. These buffers are typically stored in half-precision (FP16) or INT8 format, but switching between formats during decoding (e.g., from INT4 to FP16) incurs costly conversion overheads. Moreover, the sequence length and batch size influence the memory footprint non-linearly, especially in autoregressive generation tasks [57]. To address this, memory-aware scheduling strategies can be employed, such as token-based quantization, dynamic precision switching, and lazy decoding. These techniques adjust quantization policies at runtime based on current memory pressure, but they require a flexible inference backend capable of on-the-fly graph rewrites or control flow manipulation [58]. Hardware-specific optimizations further complicate the deployment pipeline. Different processors have varying support for low-bit integer arithmetic. For example, ARMv9-A NEON and Apple’s Neural Engine support 8-bit operations but lack direct support for 4-bit or ternary arithmetic [59]. Similarly, NVIDIA’s A100 and H100 GPUs support 4-bit tensor cores via INT4 and FP8 formats, but require proper tensor alignment and calibration to achieve peak throughput [60]. The choice of quantization format (e.g., symmetric vs. asymmetric, per-channel vs. per-tensor) directly affects kernel selection and instruction dispatch at the hardware level. Consequently, deployment must be co-designed with the hardware backend, often necessitating custom kernel libraries or code generation tools such as TVM, XLA, or Glow. Additionally, hardware-aware quantization schemes can be used during training or calibration to adaptively select quantization parameters that match the numerical behavior of the target device, thus reducing the gap between theoretical and actual performance. Another practical concern is model interoperability and serialization. Quantized models must be exported in a format that preserves their quantization metadata, such as scale factors, zero-points, bit-widths, and layout transformations. Standard formats like ONNX and FlatBuffers support quantization annotations, but custom operators or non-uniform quantization often require extensions or proprietary backends [61]. During deployment, the loading and deserialization pipeline must reconstruct the quantization parameters precisely to ensure correct execution [62]. In multi-device settings (e.g., edge-cloud split inference), consistency between serialized models and runtime decoders becomes essential to avoid mismatches that lead to divergence or hallucinated outputs. This is particularly important in generative applications such as code generation, dialogue agents, or image synthesis, where output artifacts may not be easily detected. Furthermore, real-time applications impose strict latency and throughput requirements that constrain the design space of quantized models. For instance, in conversational agents running on edge devices, response time must be below 300 milliseconds to maintain natural interactivity. This latency budget includes token decoding, beam search (or sampling), and I/O overheads [63]. Quantized models help meet these constraints by reducing memory access and enabling faster matrix operations. However, decoding pipelines must be carefully optimized to avoid bottlenecks caused by cache lookups, attention re-computation, or low-bit dequantization. Techniques such as cache fusion, attention approximation, and quantized beam search can help alleviate these issues, but often require non-trivial engineering effort and tight integration with the inference engine. Moreover, quantized models tend to be more sensitive to noise, and their output can degrade under certain sampling strategies (e.g., nucleus or temperature sampling). Therefore, runtime monitoring and adaptive decoding strategies are necessary to maintain quality under variable system conditions [64]. In conclusion, the implementation and deployment of quantized generative models is a multifaceted engineering challenge that spans software, hardware, and model architecture considerations. Successful deployment requires not only accurate quantization algorithms, but also a deep integration with inference toolchains, robust handling of numerical and memory issues, and attention to real-world system constraints. As GenAI continues to scale and enter more resource-constrained environments, these considerations will become increasingly central to achieving practical, reliable, and performant deployment of generative models across diverse application domains.

6. Challenges, Limitations, and Open Problems in Quantizing Generative Models

Despite the remarkable progress made in the quantization of generative AI models, several critical challenges and limitations remain unresolved, presenting significant barriers to widespread adoption and deployment [65]. These challenges are deeply intertwined with the unique characteristics of generative models, such as their high-dimensional autoregressive dependencies, sensitivity to numerical precision, and the semantic richness of their outputs. Unlike discriminative models, which primarily rely on classification logits or bounding box coordinates, generative models produce complex, structured outputs such as text, code, or images—where even small perturbations introduced by quantization can result in semantically incoherent or perceptually jarring artifacts. Consequently, quantization techniques that have proven effective for convolutional neural networks or feedforward architectures often fail to generalize to large-scale generative transformers without extensive adaptation and careful tuning. One of the foremost limitations in current quantization approaches for generative models is the lack of theoretical guarantees or formal robustness bounds. Most quantization strategies—such as uniform or non-uniform quantization, symmetric or asymmetric scaling, and learned quantization via quantization-aware training—rely on empirical heuristics [66]. While these heuristics can be effective in practice, they lack principled frameworks that can predict or guarantee performance retention under quantization noise [67]. For example, it is unclear how quantization errors propagate through self-attention layers, particularly in long-range contexts where multi-hop dependencies amplify small perturbations [68]. Similarly, the quantization of normalization layers, which are sensitive to small deviations in mean and variance statistics, often introduces non-trivial numerical instabilities. Without rigorous analysis, developers must rely on expensive empirical grid searches over quantization parameters, increasing the engineering burden and limiting generalizability across model sizes and domains. Another major challenge is the difficulty in maintaining output quality and diversity under aggressive quantization, especially for models operating at sub-6-bit precision [69]. At lower bit-widths, quantization noise not only degrades model accuracy but also alters the distributional properties of the outputs. For example, in language generation, 4-bit quantization can lead to repetitive phrases, loss of syntactic coherence, or hallucinated entities—issues that are difficult to diagnose and cannot be captured by simple metrics like perplexity or BLEU score [70]. In image generation, low-precision models may exhibit texture artifacts, color banding, or structural collapse. These issues are exacerbated by the lack of suitable perceptual or semantic metrics that are sensitive to the nuanced degradations introduced by quantization [71]. As a result, evaluating the fidelity of quantized generative models remains an open problem, often requiring time-consuming human evaluations or domain-specific heuristics. Quantization also introduces challenges in model training and fine-tuning [72]. While post-training quantization (PTQ) is desirable for its simplicity and efficiency, it often fails to preserve performance in large generative models without large and representative calibration datasets, which are frequently unavailable or impractical to construct due to privacy, licensing, or computational constraints. Quantization-aware training (QAT) can mitigate these issues by simulating quantization effects during training, but it significantly increases training complexity and requires careful initialization, hyperparameter tuning, and gradient stabilization techniques [73]. Moreover, QAT is sensitive to the choice of optimizer, learning rate schedule, and model architecture, and it may be incompatible with certain training tricks (e.g., activation checkpointing or parameter sharing) commonly used in large-scale generative training [74]. There is also a dearth of tools and frameworks that support flexible, high-performance QAT for very large models such as GPT-3, LLaMA, or diffusion-based architectures. Deployment of quantized generative models is further complicated by inconsistencies between training and inference environments [75]. Quantization artifacts that are not evident during offline evaluation may become pronounced in production due to variations in hardware behavior, such as differences in rounding modes, vectorization strategies, or memory alignment requirements. For example, an INT4 quantized model may perform well in simulation on a CPU but exhibit severe performance degradation or numerical instability when deployed on a GPU or FPGA [76]. Furthermore, quantized inference often relies on custom kernels that are tightly coupled to specific hardware backends, making it difficult to maintain portability and reproducibility. These issues are particularly problematic in mission-critical applications such as legal document generation, autonomous vehicle perception, or medical report synthesis, where errors introduced by quantization may lead to severe downstream consequences [77]. Without robust cross-platform validation and consistency guarantees, the reliability of quantized generative models remains a significant concern [78]. Another underexplored challenge lies in the interaction between quantization and other model compression techniques such as pruning, distillation, and low-rank adaptation [79,80]. While these techniques can be synergistic in principle, in practice they often interfere with each other due to conflicting requirements on model structure and training dynamics. For instance, quantization may amplify the noise introduced by pruning, or distort the logits used in distillation, leading to degraded generalization [81]. Similarly, adapter-based fine-tuning methods that insert low-rank modules into frozen transformer backbones may require special handling to avoid precision mismatches between quantized and full-precision components. Designing unified frameworks that harmoniously integrate quantization with other compression strategies is a complex and largely unsolved problem, particularly in the context of multi-task and multilingual generative models. Finally, the ethical and societal implications of quantization are beginning to surface, especially as generative models are deployed at the edge or on consumer devices. While quantization enables efficient on-device inference, it may also exacerbate biases or disparities in model behavior. For example, quantized models may disproportionately degrade outputs in low-resource languages, dialects, or cultural contexts due to their higher sensitivity to representational shifts [82]. Furthermore, the opacity introduced by aggressive quantization may hinder transparency and interpretability, making it more difficult to audit model behavior or attribute outputs. This raises questions about accountability and fairness in the deployment of compressed generative models, especially when used in high-stakes domains such as education, healthcare, or finance. There is an urgent need for research that examines not only the technical dimensions of quantization, but also its broader social, ethical, and regulatory implications. In summary, while quantization offers a powerful set of tools for reducing the computational burden of generative models, it also introduces a host of unresolved challenges that span theoretical, empirical, and sociotechnical dimensions [83]. Addressing these challenges will require interdisciplinary research that combines algorithmic innovation, systems engineering, and responsible AI practices [84]. As generative models become more pervasive, the development of robust, generalizable, and trustworthy quantization methodologies will be essential to unlocking their full potential in a safe and inclusive manner [85].

7. Future Directions and Research Opportunities

As generative AI models continue to expand in scale, capability, and application domain, the importance of model quantization as a means of enabling efficient, widespread deployment becomes even more pronounced. The next decade of research in model quantization for generative AI will likely be shaped by the convergence of multiple technological trajectories: ever-growing model sizes, increasingly heterogeneous hardware ecosystems, rising demand for on-device and edge deployment, and expanding societal expectations around energy efficiency, privacy, and fairness [86]. Consequently, the future of quantization is not merely a matter of improving numerical techniques, but of developing holistic, system-level solutions that are adaptable, context-aware, and scalable across model architectures, data modalities, and usage environments [87]. In this section, we explore several promising avenues of research that hold potential for advancing the field. A compelling future direction lies in the development of adaptive and dynamic quantization schemes that respond to contextual and runtime signals. Current quantization approaches are largely static: quantization parameters are fixed after training and remain unchanged throughout inference. However, generative models, especially those deployed in interactive or multi-modal settings, often operate over inputs with highly variable complexity. For instance, a dialogue model may need to respond to both simple factual queries and nuanced philosophical prompts, each requiring different levels of representational precision. Adaptive quantization techniques, wherein bit-widths, scale factors, or even quantization methods themselves are modulated dynamically based on input complexity, user preferences, or system constraints, could provide a powerful mechanism to balance fidelity and efficiency on the fly [88]. Realizing such systems will require new architectures that support conditional computation paths, differentiable quantization parameterization, and tight integration with runtime profiling mechanisms. Another promising research opportunity involves the co-design of quantization-aware model architectures. Existing generative models—especially large transformer variants—were not designed with quantization in mind [89]. As such, many of their design choices (e.g., GELU activations, high-rank attention maps, or deep residual pathways) are unfriendly to low-precision arithmetic. Future architectures may be designed explicitly for quantization robustness, incorporating layers that are natively resilient to quantization noise, such as quantization-compatible normalization schemes, activation functions with bounded dynamic ranges, or numerically stable attention mechanisms. In addition, novel architectural motifs such as mixture-of-experts, sparse attention, and linear transformers offer new opportunities for quantization-aware innovation, particularly if they can be combined with structured pruning, parameter sharing, or weight factorization [90]. The resulting models may exhibit better trade-offs between expressiveness and compressibility, especially when trained end-to-end with quantization constraints. The development of differentiable and trainable quantization functions is another critical area of ongoing and future research [91]. Conventional quantization relies on non-differentiable rounding and clipping operations, which are typically approximated during backpropagation using the straight-through estimator (STE). While effective to a degree, STE introduces gradient estimation errors and limits the expressiveness of the quantization function. Recent advances in learned quantization—where quantization parameters such as codebooks, scales, or rounding offsets are themselves learned through gradient descent—open the door to more flexible and data-driven quantization strategies. Extending this line of research, future work may explore quantization functions that are fully differentiable, parameterized by neural networks, or even adversarially trained to minimize perceptual distortion in generative outputs. Such approaches could integrate quantization more tightly into the training loop, enabling models to co-adapt to their quantization-induced constraints in a more principled and efficient manner [92]. Another fertile area for exploration is the integration of quantization with retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) and memory-enhanced architectures [93]. As generative models increasingly rely on external sources of information—such as knowledge bases, document retrieval systems, or semantic memories—the role of quantization becomes more complex. Quantizing the internal model is only part of the challenge; retrieval components, index embeddings, and memory access mechanisms must also be quantized to fit within tight memory budgets [94]. However, quantization may disrupt semantic similarity metrics, degrade retrieval accuracy, or introduce temporal inconsistency across retrieved memories. Research into quantization-aware retrieval, embedding distillation, and low-precision indexing could help preserve the integrity of retrieval-augmented generation pipelines while significantly reducing resource consumption. Moreover, hybrid systems that combine quantized generation with full-precision retrieval—or vice versa—could offer new trade-off frontiers for both performance and efficiency. The emergence of multi-modal generative models, such as those combining text, vision, audio, and other modalities, poses additional challenges and opportunities for quantization. These models often require different levels of precision across modalities—e.g., pixel-level accuracy for image synthesis, versus semantic coherence for language generation—and their internal representations may exhibit varying sensitivity to quantization noise. This heterogeneity calls for quantization schemes that are modality-aware, supporting variable bit-widths, cross-modal calibration, and precision scheduling. Moreover, future research may investigate how joint quantization across modalities can be optimized to exploit shared structure, redundancies, or co-attentive features [95]. For instance, quantizing joint embeddings or shared transformers in a multi-modal encoder-decoder may benefit from cross-modal regularization or contrastive learning techniques that enhance quantization robustness while preserving alignment [96]. A particularly underexplored yet vital direction is the development of quantization benchmarking and evaluation standards for generative models. Unlike classification or regression models, generative systems lack universally accepted evaluation metrics that correlate well with human judgment, especially under low-precision perturbations. Existing benchmarks tend to focus narrowly on perplexity, BLEU, or FID, which fail to capture the rich spectrum of degradations introduced by quantization. New metrics that measure semantic coherence, diversity, creativity, and factual consistency—preferably in a perceptually or linguistically informed manner—are urgently needed. Furthermore, benchmarking frameworks must be extended to account for inference latency, power consumption, and deployment constraints, reflecting real-world performance rather than purely academic settings [97]. Community-driven efforts to establish such benchmarks will be essential to guiding progress and ensuring reproducibility in the quantization research community [98]. Finally, the societal and environmental dimensions of quantization research merit sustained attention [99]. As generative models grow ever larger and more computationally intensive, quantization offers one of the most scalable paths toward sustainable AI development. Quantized models consume less energy, generate less heat, and require fewer resources to deploy and maintain, thereby reducing the environmental footprint of AI systems [100]. However, these benefits must be weighed against risks such as performance disparity, loss of transparency, or increased difficulty in interpretability. Future research must consider how quantization interacts with broader goals such as algorithmic fairness, accessibility, and digital inclusion. For instance, can quantization be used to democratize access to powerful generative tools in bandwidth-limited or compute-constrained environments [101]? Can we develop equitable quantization policies that preserve performance across different languages, demographics, or cultural settings? Addressing these questions will require interdisciplinary collaboration that bridges the technical, human, and ecological aspects of generative AI. In conclusion, the future of quantization in generative AI is both rich and complex, encompassing deep algorithmic innovation, architectural redesign, systems integration, and ethical foresight. While much progress has been made in recent years, the challenges that remain are profound and multifaceted [102]. By embracing a long-term vision grounded in adaptability, robustness, and societal benefit, researchers and practitioners can transform quantization from a mere compression technique into a foundational enabler of the next generation of intelligent, efficient, and inclusive generative systems.

8. Conclusions

In this comprehensive review, we have examined the evolving landscape of model quantization in the context of generative artificial intelligence, emphasizing its growing significance, technical intricacies, current progress, and enduring challenges. Quantization, once primarily associated with efficient inference in discriminative models, has now become a central tool in addressing the computational and memory demands of large-scale generative models such as autoregressive transformers, diffusion-based networks, and multi-modal synthesis systems [103]. The relentless escalation in model size—often reaching hundreds of billions of parameters—has forced the research community and industry alike to reevaluate how to deliver performant, accessible, and sustainable generative AI, especially in latency- and resource-constrained environments. Quantization offers a compelling solution in this context, enabling reductions in memory footprint, bandwidth usage, and inference latency, all while preserving—at least to a certain degree—the quality and diversity of generated content. However, as we have argued throughout this review, the application of quantization to generative models introduces a set of challenges that are far more nuanced and consequential than in conventional discriminative settings [104]. One of the most salient themes emerging from our analysis is the sensitivity of generative models to even subtle perturbations in their internal representations. While classification models can often tolerate reduced precision without catastrophic degradation in accuracy, generative models must maintain complex, high-dimensional relationships across time steps, modalities, and latent variables. These dependencies, often governed by deep autoregressive or diffusion dynamics, are easily disrupted by quantization-induced noise, leading to incoherent, repetitive, or syntactically invalid outputs [105]. Moreover, quantization can distort the probabilistic distributions underpinning generation, biasing token sampling strategies, misaligning latent interpolations, or amplifying exposure biases. The consequences are particularly severe in long-form text generation, artistic image synthesis, or code generation, where semantic fidelity and structural validity are paramount. Therefore, successful quantization in this domain demands a fundamentally different approach—one that goes beyond naïve precision reduction and incorporates deeper understanding of model behavior, training dynamics, and representational geometry. Throughout this review, we explored the multitude of strategies that have been proposed to address these issues. Post-training quantization offers a fast and hardware-friendly path to model compression but is often limited by its reliance on calibration datasets and lack of performance guarantees [106]. Quantization-aware training, while more robust, introduces significant complexity into the training pipeline, requiring custom layers, gradient estimation techniques, and extensive tuning. Mixed-precision quantization, where different layers or submodules are quantized to different bit-widths, presents a practical compromise but raises new challenges in managing heterogeneous inference pipelines and optimizing hardware utilization. More advanced techniques, such as learned quantization functions, codebook-based quantization, and integer-only quantization, push the boundaries of precision-accuracy trade-offs but remain experimental and difficult to scale to large foundation models [107]. Our detailed exposition of mathematical frameworks and empirical strategies highlighted not only the breadth of current approaches but also the lack of unified theory and standardized benchmarks, which hinders cross-comparison and reproducibility. Equally important are the systemic and sociotechnical considerations surrounding quantization [108]. While the technical benefits are clear—reduced FLOPs, lower power consumption, and faster deployment cycles—the impact on fairness, robustness, and inclusivity remains underexplored [109]. Quantization can exacerbate biases, particularly when models are trained or evaluated on high-resource datasets and then compressed for deployment in low-resource or multilingual settings. Furthermore, the opacity introduced by low-precision arithmetic can undermine interpretability and trust, especially when the quantized models are deployed in high-stakes domains such as healthcare, law, or education [110]. There is an urgent need for quantization-aware evaluation protocols that assess not only performance metrics but also ethical and social dimensions of deployment. This includes ensuring that quantized models maintain equitable performance across demographic groups, do not amplify harmful biases, and remain accountable and debuggable even when operating at reduced numerical precision. Looking ahead, the road to efficient and reliable generative AI is intricately linked to the evolution of quantization research. We have outlined a wide array of future directions, including dynamic precision scheduling, co-design of quantization-friendly architectures, differentiable quantization operators, modality-aware compression, and quantization-augmented retrieval systems. Each of these represents a frontier in its own right, requiring deep algorithmic innovation, systems-level engineering, and interdisciplinary collaboration. In particular, we emphasized the potential of adaptive quantization mechanisms that respond to input complexity or deployment constraints in real-time, as well as the importance of aligning quantization research with emerging trends in multi-modal and instruction-following generative models. The convergence of quantization with other model compression techniques—such as pruning, distillation, and low-rank adaptation—also opens up rich avenues for joint optimization, though it introduces new trade-offs and stability concerns that must be carefully managed.

In sum, the quantization of generative AI models represents both a grand challenge and a grand opportunity. It challenges our assumptions about model design, numerical representation, and optimization under constraints, while offering a pathway toward truly ubiquitous, resource-efficient intelligence. As we continue to push the boundaries of what generative models can achieve, it is imperative that we also push the boundaries of how efficiently, ethically, and robustly they can be delivered. Quantization, when approached not merely as a compression tool but as an integral part of model development, holds the key to unlocking the next generation of scalable, sustainable, and socially responsible generative AI systems.

References

- Cao, H.; Tan, C.; Gao, Z.; Xu, Y.; Chen, G.; Heng, P.A.; Li, S.Z. A Survey on Generative Diffusion Models. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 2024, 36, 2814–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignac, C.; Krawczuk, I.; Siraudin, A.; Wang, B.; Cevher, V.; Frossard, P. DiGress: Discrete Denoising diffusion for graph generation. In Proceedings of the The Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Halabi, M.E.; Ji, M.; Song, H.O. LayerMerge: Neural Network Depth Compression through Layer Pruning and Merging. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:2406.12837 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Barratt, S.; Sharma, R. A Note on the Inception Score. 2018; arXiv:stat.ML/1801.01973]. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; Yang, X.; Wang, W.Y.; Li, L. ReDi: efficient learning-free diffusion inference via trajectory retrieval. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR; 2023; pp. 41770–41785. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.g.; Kim, H.; Shin, C.; Tan, X.; Liu, C.; Meng, Q.; Qin, T.; Chen, W.; Yoon, S.; Liu, T.Y. PriorGrad: Improving Conditional Denoising Diffusion Models with Data-Dependent Adaptive Prior. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations; 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Ermon, S. Improved techniques for training score-based generative models. Advances in neural information processing systems 2020, 33, 12438–12448. [Google Scholar]

- Ulhaq, A.; Akhtar, N.; Pogrebna, G. Efficient diffusion models for vision: A survey. arXiv, 2022; arXiv:2210.09292 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Lai, Z.; Xu, L.; Guo, J.; Cao, L.; Zhang, S.; Dai, B.; Ji, R. Dual3D: Efficient and Consistent Text-to-3D Generation with Dual-mode Multi-view Latent Diffusion. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:2405.09874 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Croitoru, F.A.; Hondru, V.; Ionescu, R.T.; Shah, M. Diffusion Models in Vision: A Survey. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2023, 45, 10850–10869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, X.; Feng, J. Accelerating score-based generative models with preconditioned diffusion sampling. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision. Springer; 2022; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichol, A.; Dhariwal, P. Improved Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models, 2021, [arXiv:cs.LG/2102.09672].

- Park, J.; Kwon, G.; Ye, J.C. ED-NeRF: Efficient Text-Guided Editing of 3D Scene using Latent Space NeRF. arXiv, 2023; arXiv:2310.02712 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.; Zhang, T.; Sun, P.; Li, Z.; Zhou, S. Fq-vit: Post-training quantization for fully quantized vision transformer. arXiv, 2021; arXiv:2111.13824 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, J.; Zhao, S. A Unified Sequence Parallelism Approach for Long Context Generative AI. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:2405.07719 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, G.; Ma, X.; Wang, X. Structural pruning for diffusion models. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, S.; Kwak, S.; Jang, H.; Jeong, J.; Huang, J.; Shin, J.; Xie, S. Representation alignment for generation: Training diffusion transformers is easier than you think. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:2410.06940 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lovelace, J.; Kishore, V.; Wan, C.; Shekhtman, E.; Weinberger, K.Q. Latent diffusion for language generation. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 36. [Google Scholar]

- So, J.; Lee, J.; Ahn, D.; Kim, H.; Park, E. Temporal dynamic quantization for diffusion models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, H.; Yang, J.; Huang, H. Taming diffusion model for exemplar-based image translation. Computational Visual Media 2024, 10, 1031–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Lin, Z.; Fanti, G. Improving the Training of Rectified Flows. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:2405.20320 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hegde, S.; Batra, S.; Zentner, K.; Sukhatme, G. Generating behaviorally diverse policies with latent diffusion models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2023, 36, 7541–7554. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Z.; Gu, S.; Wang, C.; Zhang, T.; Bao, J.; Chen, D.; Guo, B. Volumediffusion: Flexible text-to-3d generation with efficient volumetric encoder. arXiv, 2023; arXiv:2312.11459 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Contributors, O. OneDiff: An out-of-the-box acceleration library for diffusion models. https://github.com/siliconflow/onediff, 2022.

- Zhu, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, Q. SlimFlow: Training Smaller One-Step Diffusion Models with Rectified Flow. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:2407.12718 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, W. A comprehensive survey on knowledge distillation of diffusion models. arXiv, 2023; arXiv:2304.04262 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, H.; Liu, X.; Pan, J.; Liew, J.H.; Liu, Q.; Feng, J. Perflow: Piecewise rectified flow as universal plug-and-play accelerator. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:2405.07510 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Rabin, J.; Peyré, G.; Delon, J.; Bernot, M. Wasserstein barycenter and its application to texture mixing. In Proceedings of the Scale Space and Variational Methods in Computer Vision: Third International Conference, SSVM 2011, Ein-Gedi, Israel, 2011, Revised Selected Papers 3. Springer, 2012, May 29–June 2; pp. 435–446. [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Xie, B.; Wu, B.; Yan, Y. Post-training quantization on diffusion models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2023,; pp. 1972–1981.

- Heusel, M.; Ramsauer, H.; Unterthiner, T.; Nessler, B.; Hochreiter, S. GANs Trained by a Two Time-Scale Update Rule Converge to a Local Nash Equilibrium, 2018, [arXiv:cs.LG/1706.08500].

- Poole, B.; Jain, A.; Barron, J.T.; Mildenhall, B. DreamFusion: Text-to-3D using 2D Diffusion. arXiv 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hochbruck, M.; Ostermann, A. Exponential integrators. Acta Numerica 2010, 19, 209–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Dou, Z.; Cao, Z.; Liao, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, W.; Liu, Y.; Komura, T.; Wang, W.; Liu, L. Emdm: Efficient motion diffusion model for fast, high-quality motion generation.

- Wang, J.; Fang, J.; Li, A.; Yang, P. PipeFusion: Displaced Patch Pipeline Parallelism for Inference of Diffusion Transformer Models. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:2405.14430 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J.; Chen, C.; Xie, Q.; Lu, H. PEA-Diffusion: Parameter-Efficient Adapter with Knowledge Distillation in non-English Text-to-Image Generation. arXiv, 2023; arXiv:2311.17086 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, C.; Sang, N. Videolcm: Video latent consistency model. arXiv, 2023; arXiv:2312.09109 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, G.; Wang, K.; Shi, H. Versatile diffusion: Text, images and variations all in one diffusion model. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2023; pp. 7754–7765.

- Gholami, A.; Kim, S.; Dong, Z.; Yao, Z.; Mahoney, M.W.; Keutzer, K. A survey of quantization methods for efficient neural network inference. In Low-Power Computer Vision; Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2022; pp. 291–326.

- Yang, Y.; Dai, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, H. Efficient Quantization Strategies for Latent Diffusion Models. 2023; arXiv:cs.CV/2312.05431]. [Google Scholar]

- Mou, C.; Wang, X.; Xie, L.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Qi, Z.; Shan, Y. T2i-adapter: Learning adapters to dig out more controllable ability for text-to-image diffusion models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2024, Vol.

- Ho, J.; Jain, A.; Abbeel, P. Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. Advances in neural information processing systems 2020, 33, 6840–6851. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.; Sohl-Dickstein, J.; Kingma, D.P.; Kumar, A.; Ermon, S.; Poole, B. Score-based generative modeling through stochastic differential equations. arXiv, 2020; arXiv:2011.13456 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, C.; Zhang, S.; Yu, N.; Feng, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, H.; Niebles, J.C.; Xiong, C.; Savarese, S.; et al. Unicontrol: A unified diffusion model for controllable visual generation in the wild. arXiv, 2023; arXiv:2305.11147 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Rasley, J.; Rajbhandari, S.; Ruwase, O.; He, Y. Deepspeed: System optimizations enable training deep learning models with over 100 billion parameters. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD international conference on knowledge discovery & data mining; 2020; pp. 3505–3506. [Google Scholar]

- Roessle, B.; Müller, N.; Porzi, L.; Rota Bulò, S.; Kontschieder, P.; Dai, A.; Nießner, M. L3dg: Latent 3d gaussian diffusion. In Proceedings of the SIGGRAPH Asia 2024 Conference Papers; 2024; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, S.; Zaragoza, H.; et al. The probabilistic relevance framework: BM25 and beyond. Foundations and Trends® in Information Retrieval 2009, 3, 333–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; Lerer, A.; Bradbury, J.; Chanan, G.; Killeen, T.; Lin, Z.; Gimelshein, N.; Antiga, L.; et al. PyTorch: An Imperative Style, High-Performance Deep Learning Library. 2019; arXiv:cs.LG/1912.01703]. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Xie, B.; Wu, B.; Yan, Y. Post-training Quantization on Diffusion Models. In Proceedings of the CVPR; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, S.; Sohn, K.; Kim, S.; Shin, J. Video probabilistic diffusion models in projected latent space. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2023; pp. 18456–18466.

- Vahdat, A.; Kreis, K.; Kautz, J. Score-based generative modeling in latent space. Advances in neural information processing systems 2021, 34, 11287–11302. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob, B.; Kligys, S.; Chen, B.; Zhu, M.; Tang, M.; Howard, A.; Adam, H.; Kalenichenko, D. Quantization and Training of Neural Networks for Efficient Integer-Arithmetic-Only Inference. 2017; arXiv:cs.LG/1712.05877]. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, M.; Bai, Y.; Cornman, A.; Davis, C.; Huang, X.; Jeon, H.; Kulshrestha, S.; Lambert, J.; Li, S.; Zhou, X.; et al. Scenediffuser: Efficient and controllable driving simulation initialization and rollout. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 37, 55729–55760. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Sun, P.; Song, Y.; Luo, P. Diffusiondet: Diffusion model for object detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2023,; pp. 19830–19843.

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; Ramesh, A.; Goh, G.; Agarwal, S.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Mishkin, P.; Clark, J.; et al. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PmLR; 2021; pp. 8748–8763. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Jia, Z.; Luo, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wu, C. DiffusionPipe: Training Large Diffusion Models with Efficient Pipelines. 2024; arXiv:cs.DC/2405.01248]. [Google Scholar]

- De Bortoli, V.; Thornton, J.; Heng, J.; Doucet, A. Diffusion schrödinger bridge with applications to score-based generative modeling. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2021, 34, 17695–17709. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B.; Ye, J.C. Denoising mcmc for accelerating diffusion-based generative models. arXiv, 2022; arXiv:2209.14593 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, J.; Pan, J.; Wang, J.; Li, A.; Sun, X. PipeFusion: Patch-level Pipeline Parallelism for Diffusion Transformers Inference. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:2405.14430 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zand, M.; Etemad, A.; Greenspan, M. Diffusion models with deterministic normalizing flow priors. arXiv, 2023; arXiv:2309.01274 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Srinivasan, B.; Shen, Z.; Qin, X.; Faloutsos, C.; Rangwala, H.; Karypis, G. Mixed-type tabular data synthesis with score-based diffusion in latent space. arXiv, 2023; arXiv:2310.09656 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Xu, S.; Cao, X.; Zhang, B.; Sun, X. Q-DM: An Efficient Low-bit Quantized Diffusion Model. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS 2023, October 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, M.; Chen, P.; Ye, P.; Xia, G.; Chen, T.; Bouganis, C.S.; Zhao, Y. MD-DiT: Step-aware Mixture-of-Depths for Efficient Diffusion Transformers. In Proceedings of the Adaptive Foundation Models: Evolving AI for Personalized and Efficient Learning.

- Nagel, M.; Amjad, R.A.; Van Baalen, M.; Louizos, C.; Blankevoort, T. Up or down? In adaptive rounding for post-training quantization. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR; 2020; pp. 7197–7206. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.; Liu, J.; Zhu, J.; Xi, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, W. A Survey on Diffusion Models for Recommender Systems. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:2409.05033 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Karras, T.; Aittala, M.; Aila, T.; Laine, S. Elucidating the design space of diffusion-based generative models. Advances in neural information processing systems 2022, 35, 26565–26577. [Google Scholar]

- Melnik, A.; Ljubljanac, M.; Lu, C.; Yan, Q.; Ren, W.; Ritter, H. Video diffusion models: A survey. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:2405.03150 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Deng, F.; Kawaguchi, K.; Gulcehre, C.; Ahn, S. Simple hierarchical planning with diffusion. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:2401.02644 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Luhman, E.; Luhman, T. Knowledge distillation in iterative generative models for improved sampling speed. arXiv, 2021; arXiv:2101.02388 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, J.; Jain, A.; Abbeel, P. Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models. 2020; arXiv:cs.LG/2006.11239]. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, S.; Tan, Y.; Patil, S.; Gu, D.; von Platen, P.; Passos, A.; Huang, L.; Li, J.; Zhao, H. Lcm-lora: A universal stable-diffusion acceleration module. arXiv, 2023; arXiv:2311.05556 2023. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.; Liu, J.; Wu, W.; Zhou, H.; Zhuang, B. EfficientDM: Efficient Quantization-Aware Fine-Tuning of Low-Bit Diffusion Models. 2023; arXiv:cs.CV/2310.03270]. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Cai, T.; Cao, J.; Zhang, Q.; Cai, H.; Bai, J.; Jia, Y.; Li, K.; Han, S. Distrifusion: Distributed parallel inference for high-resolution diffusion models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024, pp.; pp. 7183–7193.

- Wang, C.; Wang, Z.; Xu, X.; Tang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Lu, J. Towards Accurate Data-free Quantization for Diffusion Models. 2023; arXiv:cs.CV/2305.18723]. [Google Scholar]

- Van Den Oord, A.; Vinyals, O.; et al. Neural discrete representation learning. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, S.; Wang, Y.; Ding, C.; Liang, Y.; Li, Y.; Xu, D. Deediff: Dynamic uncertainty-aware early exiting for accelerating diffusion model generation 2023.

- Yu, Y.; Zhu, S.; Qin, H.; Li, H. BoostDream: Efficient Refining for High-Quality Text-to-3D Generation from Multi-View Diffusion. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:2401.16764 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.; Tang, J.; Tang, H.; Yang, S.; Dang, X.; Gan, C.; Han, S. AWQ: Activation-aware Weight Quantization for LLM Compression and Acceleration. 2023; arXiv:cs.CL/2306.00978]. [Google Scholar]

- Dohmatob, E.; Feng, Y.; Subramonian, A.; Kempe, J. Strong model collapse. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:2410.04840 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sabour, A.; Fidler, S.; Kreis, K. Align your steps: Optimizing sampling schedules in diffusion models. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:2404.14507 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zniyed, Y.; Nguyen, T.P.; et al. Enhanced network compression through tensor decompositions and pruning. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2024, 36, 4358–4370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Niu, L.; Yuan, Z.; Yang, D.; Wang, X.; Liu, W. PD-Quant: Post-Training Quantization based on Prediction Difference Metric. 2023; arXiv:cs.CV/2212.07048]. [Google Scholar]

- Rombach, R.; Blattmann, A.; Lorenz, D.; Esser, P.; Ommer, B. High-Resolution Image Synthesis with Latent Diffusion Models. 2021; arXiv:cs.CV/2112.10752]. [Google Scholar]

- Ran, L.; Cun, X.; Liu, J.W.; Zhao, R.; Zijie, S.; Wang, X.; Keppo, J.; Shou, M.Z. X-adapter: Adding universal compatibility of plugins for upgraded diffusion model. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024, pp.; pp. 8775–8784.

- Aiello, E.; Valsesia, D.; Magli, E. Fast inference in denoising diffusion models via mmd finetuning. IEEE Access 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, G.; Lin, J.; Seznec, M.; Wu, H.; Demouth, J.; Han, S. SmoothQuant: Accurate and Efficient Post-Training Quantization for Large Language Models. 2023; arXiv:cs.CL/2211.10438]. [Google Scholar]

- Castells, T.; Song, H.K.; Kim, B.K.; Choi, S. LD-Pruner: Efficient Pruning of Latent Diffusion Models using Task-Agnostic Insights. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024, pp.; pp. 821–830.

- Song, Y.; Ermon, S. Generative modeling by estimating gradients of the data distribution. Advances in neural information processing systems 2019, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Deng, M.; Cheng, X.; Tian, Y.; Liu, Z.; Jaakkola, T. Restart sampling for improving generative processes. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2023, 36, 76806–76838. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.; Dhariwal, P. Improved techniques for training consistency models. arXiv, 2023; arXiv:2310.14189 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, Z.; Ping, W.; Huang, J.; Zhao, K.; Catanzaro, B. Diffwave: A versatile diffusion model for audio synthesis. arXiv, 2020; arXiv:2009.09761 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, J.; Li, X.; Cheng, C.; Liu, J.; Guo, R.; Cai, S.; Yao, C.; Yang, F.; Yi, X.; Wu, C.; et al. Oneflow: Redesign the distributed deep learning framework from scratch. arXiv, 2021; arXiv:2110.15032 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Ren, Y.; Lin, Z.; Zhao, Z. Pseudo Numerical Methods for Diffusion Models on Manifolds. 2022; arXiv:cs.CV/2202.09778]. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, T.; Choi, M.; Yun, E.; Yoon, J.; Lee, G.; Cho, J.; Lee, J. A simple early exiting framework for accelerated sampling in diffusion models. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:2408.05927 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Wu, Z.; Xing, Z.; Shao, J.; Jiang, Y.G. Adadiff: Adaptive step selection for fast diffusion. arXiv, 2023; arXiv:2311.14768 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, N.; Zhang, Y.; Zen, H.; Weiss, R.J.; Norouzi, M.; Chan, W. Wavegrad: Estimating gradients for waveform generation. arXiv, 2020; arXiv:2009.00713 2020. [Google Scholar]

- You, Y.; Zhou, R.; Park, J.; Xu, H.; Tian, C.; Wang, Z.; Shen, Y. Latent 3d graph diffusion. International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), 2024.

- Wu, Z.; Zhou, P.; Yi, X.; Yuan, X.; Zhang, H. Consistent3d: Towards consistent high-fidelity text-to-3d generation with deterministic sampling prior. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024, pp.; pp. 9892–9902.

- Kim, D.; Kim, Y.; Kwon, S.J.; Kang, W.; Moon, I.C. Refining generative process with discriminator guidance in score-based diffusion models. arXiv, 2022; arXiv:2211.17091 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, M.; Chen, K.; Guo, X.; Zhang, Q.; Lu, H.; Zhong, H.; Chen, D.; Zhu, M.; Yang, H. Diffusion Models for Intelligent Transportation Systems: A Survey. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:2409.15816 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, S. Efficient 3D Shape Generation via Diffusion Mamba with Bidirectional SSMs. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:2406.05038 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.; Fang, G.; Mi, M.B.; Wang, X. Learning-to-Cache: Accelerating Diffusion Transformer via Layer Caching. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.01733, arXiv:2406.01733 2024.

- Lee, T.; Kwon, S.; Kim, T. Grid Diffusion Models for Text-to-Video Generation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024, pp.

- Tang, Z.; Tang, J.; Luo, H.; Wang, F.; Chang, T.H. Accelerating parallel sampling of diffusion models. In Proceedings of the Forty-first International Conference on Machine Learning; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, J.; Salimans, T.; Gritsenko, A.; Chan, W.; Norouzi, M.; Fleet, D.J. Video diffusion models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 8633–8646. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, S.; Li, Y.; Lin, M.; Gao, P.; Guo, G.; Lu, J.; Zhang, B. 2023; arXiv:cs.CV/2304.00253].

- Esser, S.K.; McKinstry, J.L.; Bablani, D.; Appuswamy, R.; Modha, D.S. Learned step size quantization. arXiv preprint arXiv:1902.08153, arXiv:1902.08153 2019.

- Yang, G.; Xie, Y.; Xue, Z.J.; Chang, S.E.; Li, Y.; Dong, P.; Lei, J.; Xie, W.; Wang, Y.; Lin, X.; et al. SDA: Low-Bit Stable Diffusion Acceleration on Edge FPGAs 2023.

- Wang, Z.; Lu, C.; Wang, Y.; Bao, F.; Li, C.; Su, H.; Zhu, J. Prolificdreamer: High-fidelity and diverse text-to-3d generation with variational score distillation. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, H.; Zhang, J.; Liu, S.; Han, X.; Yang, W. Ip-adapter: Text compatible image prompt adapter for text-to-image diffusion models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.06721, arXiv:2308.06721 2023.

- Li, M.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Cai, T.; Li, X.; Guo, J.; Xie, E.; Meng, C.; Zhu, J.Y.; Han, S. 2025; arXiv:cs.CV/2411.05007].

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).