Submitted:

24 August 2025

Posted:

26 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Mathematical Foundations of Quantization for Diffusion Models

2.1. Diffusion Model Formulation

2.2. Quantization as a Mapping Operator

2.3. Interaction Between Quantization and Diffusion Processes

- Model parameters: The neural network parameters are quantized to , altering the learned function [26].

- Intermediate activations: During inference, intermediate feature maps are quantized to [27].

- Noise predictions: The predicted noise is quantized, introducing additional bias to the reverse denoising process.

2.4. Precision-Performance Trade-Offs

2.5. Summary of Mathematical Insights

3. Quantization Techniques for Diffusion Models

4. Architectural Considerations and Layer-wise Sensitivity in Quantized Diffusion Models

5. Challenges and Open Problems in Quantizing Large-Scale Diffusion Models

6. Evaluation Metrics and Benchmarking Strategies for Quantized Diffusion Models

7. Future Directions and Emerging Research Opportunities in Quantized Diffusion Models

8. Conclusions and Synthesis of Insights on Quantization for Diffusion Models

References

- Watson, D.; Ho, J.; Norouzi, M.; Chan, W. Learning to efficiently sample from diffusion probabilistic models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2106.03802, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Tan, C.; Gao, Z.; Xu, Y.; Chen, G.; Heng, P.A.; Li, S.Z. A Survey on Generative Diffusion Models. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 2024, 36, 2814–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Chen, Q.; He, X.; Cheng, J. Towards accurate post-training network quantization via bit-split and stitching. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR; 2020; pp. 9847–9856. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.; Liu, L.; Liu, J.; Wu, W.; Zhou, H.; Zhuang, B. PTQD: Accurate Post-Training Quantization for Diffusion Models, 2023, [arXiv:cs.CV/2305.10657].

- Li, Y.; Gong, R.; Tan, X.; Yang, Y.; Hu, P.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, F.; Wang, W.; Gu, S. BRECQ: Pushing the Limit of Post-Training Quantization by Block Reconstruction. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, S.; Mitra, S.; Chakraborty, S.; Karanam, S.; Mukherjee, K.; Saini, S.K. Approximate Caching for Efficiently Serving {Text-to-Image} Diffusion Models. In Proceedings of the 21st USENIX Symposium on Networked Systems Design and Implementation (NSDI 24); 2024; pp. 1173–1189. [Google Scholar]

- Zniyed, Y.; Nguyen, T.P.; et al. Enhanced network compression through tensor decompositions and pruning. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2024, 36, 4358–4370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Dai, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, H. Efficient Quantization Strategies for Latent Diffusion Models, 2023, [arXiv:cs.CV/2312.05431].

- Chen, Y.H.; Sarokin, R.; Lee, J.; Tang, J.; Chang, C.L.; Kulik, A.; Grundmann, M. Speed is all you need: On-device acceleration of large diffusion models via gpu-aware optimizations. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2023, pp. 4651–4655.

- Wimbauer, F.; Wu, B.; Schoenfeld, E.; Dai, X.; Hou, J.; He, Z.; Sanakoyeu, A.; Zhang, P.; Tsai, S.; Kohler, J.; et al. Cache me if you can: Accelerating diffusion models through block caching. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024, pp. 6211–6220.

- Li, Y.; Xu, S.; Zhang, B.; Cao, X.; Gao, P.; Guo, G. Q-ViT: Accurate and Fully Quantized Low-bit Vision Transformer, 2022, [arXiv:cs.CV/2210.06707].

- He, Y.; Liu, J.; Wu, W.; Zhou, H.; Zhuang, B. EfficientDM: Efficient Quantization-Aware Fine-Tuning of Low-Bit Diffusion Models, 2023, [arXiv:cs.CV/2310.03270].

- Liu, L.; Ren, Y.; Lin, Z.; Zhao, Z. Pseudo Numerical Methods for Diffusion Models on Manifolds, 2022, [arXiv:cs.CV/2202.09778].

- Luo, S.; Tan, Y.; Patil, S.; Gu, D.; von Platen, P.; Passos, A.; Huang, L.; Li, J.; Zhao, H. Lcm-lora: A universal stable-diffusion acceleration module. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.05556 2023. [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Lee, J.; Shin, C.; Kim, S.; Kim, H.; Yoon, S. Perception Prioritized Training of Diffusion Models, 2022, [arXiv:cs.CV/2204.00227].

- Ma, X.; Fang, G.; Wang, X. Deepcache: Accelerating diffusion models for free. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024, pp. 15762–15772.

- Guo, H.; Lu, C.; Bao, F.; Pang, T.; Yan, S.; Du, C.; Li, C. Gaussian mixture solvers for diffusion models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Yang, L.; Jiang, X.; Lu, H.; Di, Z.; Lu, W.; Chen, J.; Liu, K.; Yu, Y.; Lan, T.; et al. SwiftDiffusion: Efficient Diffusion Model Serving with Add-on Modules, 2024, [arXiv:cs.DC/2407.02031].

- Hyvärinen, A.; Dayan, P. Estimation of non-normalized statistical models by score matching. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2005, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Wang, Z.; Xu, X.; Tang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Lu, J. Towards Accurate Data-free Quantization for Diffusion Models, 2023, [arXiv:cs.CV/2305.18723].

- Schuster, T.; Fisch, A.; Gupta, J.; Dehghani, M.; Bahri, D.; Tran, V.; Tay, Y.; Metzler, D. Confident adaptive language modeling. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 17456–17472. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, Z.; Ping, W.; Huang, J.; Zhao, K.; Catanzaro, B. Diffwave: A versatile diffusion model for audio synthesis. arXiv preprint arXiv:2009.09761 2020. [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Li, Z.; Li, R.; Li, X.; Gao, J. Diffusion models for time-series applications: a survey. Frontiers of Information Technology & Electronic Engineering 2024, 25, 19–41. [Google Scholar]

- Schuster, T.; Fisch, A.; Jaakkola, T.; Barzilay, R. Consistent accelerated inference via confident adaptive transformers. arXiv preprint arXiv:2104.08803 2021. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Lian, L.; Yang, H.; Dong, Z.; Kang, D.; Zhang, S.; Keutzer, K. Q-diffusion: Quantizing diffusion models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2023, pp. 17535–17545.

- Mao, W.; Xu, C.; Zhu, Q.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y. Leapfrog diffusion model for stochastic trajectory prediction. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2023, pp. 5517–5526.

- Pilipović, R.; Bulić, P.; Risojević, V. Compression of convolutional neural networks: A short survey. In Proceedings of the 2018 17th International Symposium INFOTEH-JAHORINA (INFOTEH). IEEE; 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Nichol, A.Q.; Dhariwal, P. Improved denoising diffusion probabilistic models. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR; 2021; pp. 8162–8171. [Google Scholar]

- Rabin, J.; Peyré, G.; Delon, J.; Bernot, M. Wasserstein barycenter and its application to texture mixing. In Proceedings of the Scale Space and Variational Methods in Computer Vision: Third International Conference, SSVM 2011, Ein-Gedi, Israel, 2011, Revised Selected Papers 3. Springer, 2012, May 29–June 2; pp. 435–446.

- Zhang, Q.; Chen, Y. Diffusion normalizing flow. Advances in neural information processing systems 2021, 34, 16280–16291. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Y.; Wang, X.; Wu, J.Z.; Shi, Y.; Chen, Y.; Fan, Z.; Xiao, W.; Zhao, R.; Chang, S.; Wu, W.; et al. Mix-of-show: Decentralized low-rank adaptation for multi-concept customization of diffusion models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J.; Jo, W.; Hong, S.; Kwon, B.; Park, W.; Yoo, H.J. A 28.6 mJ/iter Stable Diffusion Processor for Text-to-Image Generation with Patch Similarity-based Sparsity Augmentation and Text-based Mixed-Precision. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.04982 2024. [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Mei, S.; Fan, J.; Wang, M. An overview of diffusion models: Applications, guided generation, statistical rates and optimization. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.07771 2024. [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition, 2015, [arXiv:cs.CV/1512.03385].

- Rombach, R.; Blattmann, A.; Lorenz, D.; Esser, P.; Ommer, B. High-resolution image synthesis with latent diffusion models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2022, pp. 10684–10695.

- Zhang, L.; Rao, A.; Agrawala, M. Adding conditional control to text-to-image diffusion models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2023, pp. 3836–3847.

- Xu, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, G.; Wang, K.; Shi, H. Versatile diffusion: Text, images and variations all in one diffusion model. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2023, pp. 7754–7765.

- Nagel, M.; Amjad, R.A.; Van Baalen, M.; Louizos, C.; Blankevoort, T. Up or down? adaptive rounding for post-training quantization. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR. 2020; pp. 7197–7206. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Y.; Lee, K. Optimizing DDPM Sampling with Shortcut Fine-Tuning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR; 2023; pp. 9623–9639. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Cai, T.; Cao, J.; Zhang, Q.; Cai, H.; Bai, J.; Jia, Y.; Li, K.; Han, S. Distrifusion: Distributed parallel inference for high-resolution diffusion models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024, pp. 7183–7193.

- So, J.; Lee, J.; Ahn, D.; Kim, H.; Park, E. Temporal dynamic quantization for diffusion models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, X.; Fang, Y.; Li, L.; Chen, X.; Lu, Y.; Liu, J.; Yin, W.; Feng, S.; et al. ERNIE-ViLG 2.0: Improving Text-to-Image Diffusion Model With Knowledge-Enhanced Mixture-of-Denoising-Experts. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), June 2023, pp. 10135–10145.

- Song, Y.; Durkan, C.; Murray, I.; Ermon, S. Maximum likelihood training of score-based diffusion models. Advances in neural information processing systems 2021, 34, 1415–1428. [Google Scholar]

- Peebles, W.; Xie, S. Scalable Diffusion Models with Transformers, 2023, [arXiv:cs.CV/2212.09748].

- Kim, D.; Kim, Y.; Kwon, S.J.; Kang, W.; Moon, I.C. Refining generative process with discriminator guidance in score-based diffusion models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2211.17091 2022. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Peng, H.Y.; Liu, Y.T.; Gu, J.; Hu, S.M. Diffusion Models for 3D Generation: A Survey. Computational Visual Media 2025, 11, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Lu, C.; Wang, Y.; Bao, F.; Li, C.; Su, H.; Zhu, J. Prolificdreamer: High-fidelity and diverse text-to-3d generation with variational score distillation. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, X.; Gong, R.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Yu, F. QDrop: Randomly Dropping Quantization for Extremely Low-bit Post-Training Quantization, 2023, [arXiv:cs.CV/2203.05740].

- chengzeyi. Stable Fast. https://github.com/chengzeyi/stable-fast, 2024.

- Tian, Y.; Jia, Z.; Luo, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wu, C. DiffusionPipe: Training Large Diffusion Models with Efficient Pipelines, 2024, [arXiv:cs.DC/2405.01248].

- Barratt, S.; Sharma, R. A Note on the Inception Score, 2018, [arXiv:stat.ML/1801.01973].

- Couairon, G.; Verbeek, J.; Schwenk, H.; Cord, M. Diffedit: Diffusion-based semantic image editing with mask guidance. arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.11427 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Fang, G.; Mi, M.B.; Wang, X. Learning-to-Cache: Accelerating Diffusion Transformer via Layer Caching. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.01733 2024. [CrossRef]

- Hang, T.; Gu, S. Improved noise schedule for diffusion training. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.03297 2024. [CrossRef]

- Walker, H.F.; Ni, P. Anderson acceleration for fixed-point iterations. SIAM Journal on Numerical Analysis 2011, 49, 1715–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Jin, Q.; Hu, J.; Chemerys, P.; Fu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Tulyakov, S.; Ren, J. Snapfusion: Text-to-image diffusion model on mobile devices within two seconds. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.; Kwon, G.; Ye, J.C. ED-NeRF: Efficient Text-Guided Editing of 3D Scene using Latent Space NeRF. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.02712.

- Blattmann, A.; Rombach, R.; Ling, H.; Dockhorn, T.; Kim, S.W.; Fidler, S.; Kreis, K. Align your latents: High-resolution video synthesis with latent diffusion models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2023, pp. 22563–22575.

- Jolicoeur-Martineau, A.; Li, K.; Piché-Taillefer, R.; Kachman, T.; Mitliagkas, I. Gotta go fast when generating data with score-based models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2105.14080 2021. [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Sohl-Dickstein, J.; Kingma, D.P.; Kumar, A.; Ermon, S.; Poole, B. Score-based generative modeling through stochastic differential equations. arXiv preprint arXiv:2011.13456 2020. [CrossRef]

- Shih, A.; Belkhale, S.; Ermon, S.; Sadigh, D.; Anari, N. Parallel sampling of diffusion models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Daras, G.; Chung, H.; Lai, C.H.; Mitsufuji, Y.; Ye, J.C.; Milanfar, P.; Dimakis, A.G.; Delbracio, M. A Survey on Diffusion Models for Inverse Problems, 2024, [arXiv:cs.LG/2410.00083].

- Ma, J.; Chen, C.; Xie, Q.; Lu, H. PEA-Diffusion: Parameter-Efficient Adapter with Knowledge Distillation in non-English Text-to-Image Generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.17086 2023. [CrossRef]

- Nahshan, Y.; Chmiel, B.; Baskin, C.; Zheltonozhskii, E.; Banner, R.; Bronstein, A.M.; Mendelson, A. Loss aware post-training quantization. Machine Learning 2021, 110, 3245–3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, T.; Fu, D.; Ermon, S.; Rudra, A.; Ré, C. Flashattention: Fast and memory-efficient exact attention with io-awareness. Advances in neural information processing systems 2022, 35, 16344–16359. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, C.; Zhou, Y.; Bao, F.; Chen, J.; Li, C.; Zhu, J. Dpm-solver++: Fast solver for guided sampling of diffusion probabilistic models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2211.01095 2022. [CrossRef]

- So, J.; Lee, J.; Ahn, D.; Kim, H.; Park, E. Temporal Dynamic Quantization for Diffusion Models, 2023, [arXiv:cs.CV/2306.02316].

- Deng, J.; Dong, W.; Socher, R.; Li, L.J.; Li, K.; Fei-Fei, L. Imagenet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. Ieee; 2009; pp. 248–255. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Lian, L.; Yang, H.; Dong, Z.; Kang, D.; Zhang, S.; Keutzer, K. Q-Diffusion: Quantizing Diffusion Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), October 2023, pp. 17535–17545.

- Yang, Y.; Wang, W.; Peng, L.; Song, C.; Chen, Y.; Li, H.; Yang, X.; Lu, Q.; Cai, D.; Wu, B.; et al. LoRA-Composer: Leveraging Low-Rank Adaptation for Multi-Concept Customization in Training-Free Diffusion Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.11627 2024. [CrossRef]

- Mo, S. Efficient 3D Shape Generation via Diffusion Mamba with Bidirectional SSMs. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.05038 2024. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xu, S.; Cao, X.; Zhang, B.; Sun, X. Q-DM: An Efficient Low-bit Quantized Diffusion Model. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS 2023, October 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B.; Ye, J.C. Denoising mcmc for accelerating diffusion-based generative models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.14593 2022. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Deng, F.; Kawaguchi, K.; Gulcehre, C.; Ahn, S. Simple hierarchical planning with diffusion. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.02644 2024. [CrossRef]

- Salimans, T.; Ho, J. Progressive distillation for fast sampling of diffusion models. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ceylan, D.; Huang, C.H.P.; Mitra, N.J. Pix2video: Video editing using image diffusion. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2023, pp. 23206–23217.

- Kim, J.; Halabi, M.E.; Ji, M.; Song, H.O. LayerMerge: Neural Network Depth Compression through Layer Pruning and Merging. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.12837 2024. [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z.; Feng, Q.; Chen, H.; Dai, Q.; Hu, H.; Xu, H.; Wu, Z.; Jiang, Y.G. A survey on video diffusion models. ACM Computing Surveys 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Ling, S.; Fu, F.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Xiao, X.; Cui, B. Training-free and Adaptive Sparse Attention for Efficient Long Video Generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.21079 2025. [CrossRef]

- Ho, J.; Salimans, T.; Gritsenko, A.; Chan, W.; Norouzi, M.; Fleet, D.J. Video diffusion models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 8633–8646. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Niu, L.; Yuan, Z.; Yang, D.; Wang, X.; Liu, W. PD-Quant: Post-Training Quantization based on Prediction Difference Metric, 2023, [arXiv:cs.CV/2212.07048].

- Liu, L.; Ren, Y.; Lin, Z.; Zhao, Z. Pseudo numerical methods for diffusion models on manifolds. arXiv preprint arXiv:2202.09778 2022. [CrossRef]

- Sohl-Dickstein, J.; Weiss, E.; Maheswaranathan, N.; Ganguli, S. Deep unsupervised learning using nonequilibrium thermodynamics. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR; 2015; pp. 2256–2265. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Z.; Gu, S.; Wang, C.; Zhang, T.; Bao, J.; Chen, D.; Guo, B. Volumediffusion: Flexible text-to-3d generation with efficient volumetric encoder. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.11459 2023. [CrossRef]

- Esser, S.K.; McKinstry, J.L.; Bablani, D.; Appuswamy, R.; Modha, D.S. Learned step size quantization. arXiv preprint arXiv:1902.08153 2019. [CrossRef]

- Pokle, A.; Geng, Z.; Kolter, J.Z. Deep equilibrium approaches to diffusion models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 37975–37990. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, Z.; Wang, J.; Loy, C.C. Resshift: Efficient diffusion model for image super-resolution by residual shifting. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Xie, B.; Wu, B.; Yan, Y. Post-training Quantization on Diffusion Models. In Proceedings of the CVPR; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Thickstun, J.; Gulrajani, I.; Liang, P.S.; Hashimoto, T.B. Diffusion-lm improves controllable text generation. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 4328–4343. [Google Scholar]

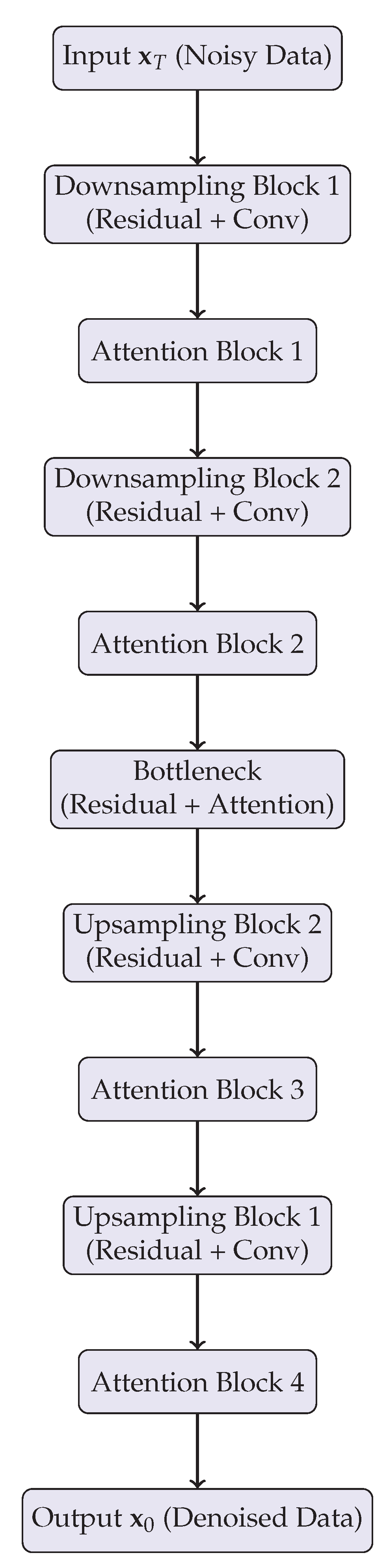

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation, 2015, [arXiv:cs.CV/1505.04597].

- Yuan, Z.; Xue, C.; Chen, Y.; Wu, Q.; Sun, G. PTQ4ViT: Post-Training Quantization Framework for Vision Transformers with Twin Uniform Quantization, 2022, [arXiv:cs.CV/2111.12293].

- Vahdat, A.; Kreis, K.; Kautz, J. Score-based generative modeling in latent space. Advances in neural information processing systems 2021, 34, 11287–11302. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Ma, J.; Peng, J.; et al. Instaflow: One step is enough for high-quality diffusion-based text-to-image generation. In Proceedings of the The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Dockhorn, T.; Vahdat, A.; Kreis, K. Score-based generative modeling with critically-damped langevin diffusion. arXiv preprint arXiv:2112.07068 2021. [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Liu, X.; Pan, J.; Liew, J.H.; Liu, Q.; Feng, J. Perflow: Piecewise rectified flow as universal plug-and-play accelerator. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.07510 2024. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Li, X.; Cheng, C.; Liu, J.; Guo, R.; Cai, S.; Yao, C.; Yang, F.; Yi, X.; Wu, C.; et al. Oneflow: Redesign the distributed deep learning framework from scratch. arXiv preprint arXiv:2110.15032 2021. [CrossRef]

- Luo, W. A comprehensive survey on knowledge distillation of diffusion models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.04262 2023. [CrossRef]

- Sheynin, S.; Ashual, O.; Polyak, A.; Singer, U.; Gafni, O.; Nachmani, E.; Taigman, Y. kNN-Diffusion: Image Generation via Large-Scale Retrieval. In Proceedings of the The Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.g.; Kim, H.; Shin, C.; Tan, X.; Liu, C.; Meng, Q.; Qin, T.; Chen, W.; Yoon, S.; Liu, T.Y. PriorGrad: Improving Conditional Denoising Diffusion Models with Data-Dependent Adaptive Prior. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Zhang, R.; Hinton, G. Analog bits: Generating discrete data using diffusion models with self-conditioning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2208.04202 2022. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Zhang, T.; Sun, P.; Li, Z.; Zhou, S. Fq-vit: Post-training quantization for fully quantized vision transformer. arXiv preprint arXiv:2111.13824 2021. [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Kwak, S.; Jang, H.; Jeong, J.; Huang, J.; Shin, J.; Xie, S. Representation alignment for generation: Training diffusion transformers is easier than you think. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.06940 2024. [CrossRef]

- Lovelace, J.; Kishore, V.; Wan, C.; Shekhtman, E.; Weinberger, K.Q. Latent diffusion for language generation. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.Y.; Huang, Z.; Shi, X.; Bian, W.; Song, G.; Liu, Y.; Li, H. Animatelcm: Accelerating the animation of personalized diffusion models and adapters with decoupled consistency learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.00769 2024.

- Peluchetti, S. Non-denoising forward-time diffusions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.14589 2023. [CrossRef]

- Poole, B.; Jain, A.; Barron, J.T.; Mildenhall, B. DreamFusion: Text-to-3D using 2D Diffusion. arXiv 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, K.; Lu, C.; Chen, J.; Zhu, J. Improved techniques for maximum likelihood estimation for diffusion odes. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR; 2023; pp. 42363–42389. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.; Dhariwal, P. Improved techniques for training consistency models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.14189 2023. [CrossRef]

- Fang, G.; Ma, X.; Wang, X. Structural pruning for diffusion models. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Buckwar, E.; Winkler, R. Multistep methods for SDEs and their application to problems with small noise. SIAM journal on numerical analysis 2006, 44, 779–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Fang, J.; Li, A.; Pan, J. Unveiling Redundancy in Diffusion Transformers (DiTs): A Systematic Study. arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.13588 2024. [CrossRef]

- Castells, T.; Song, H.K.; Kim, B.K.; Choi, S. LD-Pruner: Efficient Pruning of Latent Diffusion Models using Task-Agnostic Insights. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024, pp. 821–830.

- Chen, J.; Zhang, A.; Li, M.; Smola, A.; Yang, D. A cheaper and better diffusion language model with soft-masked noise. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.04746 2023. [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Dhariwal, P.; Chen, M.; Sutskever, I. Consistency models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.01469 2023.

- Wang, J.; Fang, J.; Li, A.; Yang, P. PipeFusion: Displaced Patch Pipeline Parallelism for Inference of Diffusion Transformer Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.14430 2024. [CrossRef]

- Hessel, J.; Holtzman, A.; Forbes, M.; Bras, R.L.; Choi, Y. CLIPScore: A Reference-free Evaluation Metric for Image Captioning, 2022, [arXiv:cs.CV/2104.08718].

- Shen, M.; Chen, P.; Ye, P.; Xia, G.; Chen, T.; Bouganis, C.S.; Zhao, Y. MD-DiT: Step-aware Mixture-of-Depths for Efficient Diffusion Transformers. In Proceedings of the Adaptive Foundation Models: Evolving AI for Personalized and Efficient Learning.

| Technique | Precision Allocation | Training Strategy | Hardware Compatibility | Advantages | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uniform PTQ | Fixed, evenly spaced levels | Post-training only | Very high (efficient integer ops) | Simple, hardware-friendly, no retraining | Poor quality under low bitwidths |

| Non-uniform PTQ | Adaptive, density-based | Post-training only | Moderate (requires LUTs or nonlinear ops) | Lower quantization error, preserves distributions | Higher hardware complexity |

| Quantization-Aware Training (QAT) | Flexible, learned during training | Retraining or fine-tuning | High (depends on hardware/software stack) | High robustness at low bitwidths | Requires heavy retraining |

| Hybrid PTQ+QAT | Selective, per-module precision | Limited fine-tuning | High | Balance of efficiency and robustness | Complex design, tuning required |

| Mixed-Precision Quantization | Per-layer or per-module bitwidths | Post-training or QAT | High (widely supported) | Exploits sensitivity heterogeneity | Requires careful profiling |

| Timestep-Adaptive Quantization | Stage-dependent bitwidths | QAT or post-hoc adjustments | Moderate | Matches error sensitivity across timesteps | Complex scheduling, less hardware support |

| Dynamic Quantization | Input-dependent bitwidths | On-the-fly, runtime adjustment | Low to moderate | Highly adaptive, efficient in practice | High runtime overhead, less predictable |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).