Submitted:

15 August 2025

Posted:

18 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Data Pre-Processing and Variable Definition

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Vaccine Type and Time of Vaccination

3.2. Production Metrics in Vaccinated and Non-Vaccinated Cows

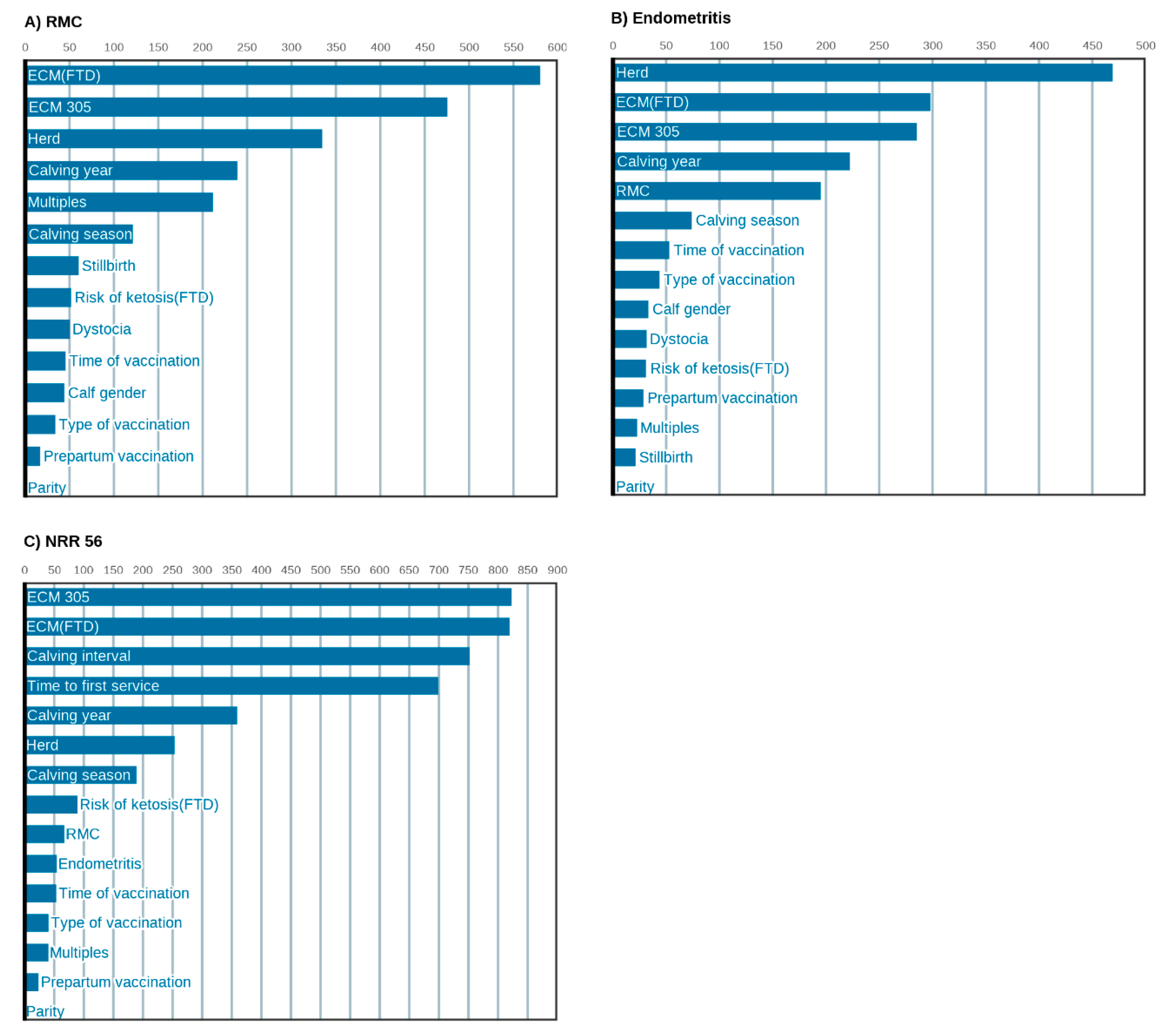

3.3. Milk Yield, Performance and Herd Management Are Most Relevant for Uterine Health and Fertility

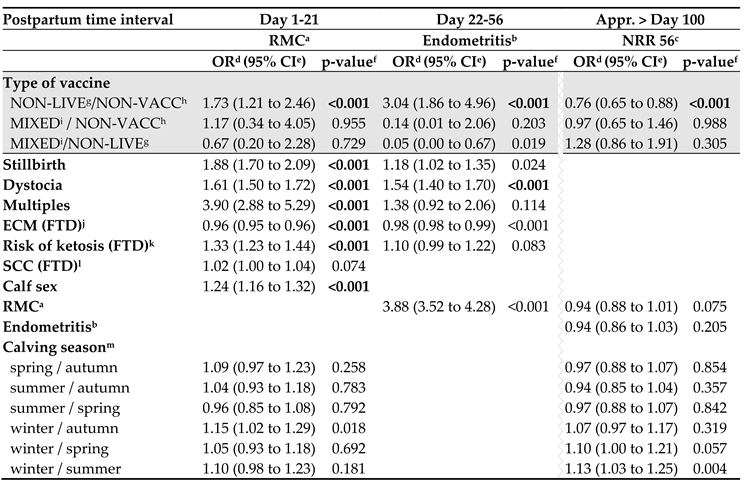

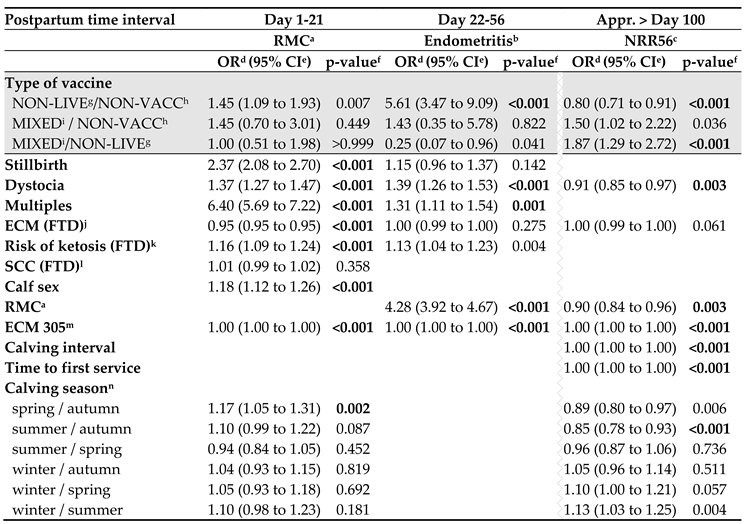

3.4. Prepartum Non-Live Vaccination Affects Uterine Health and Fertility

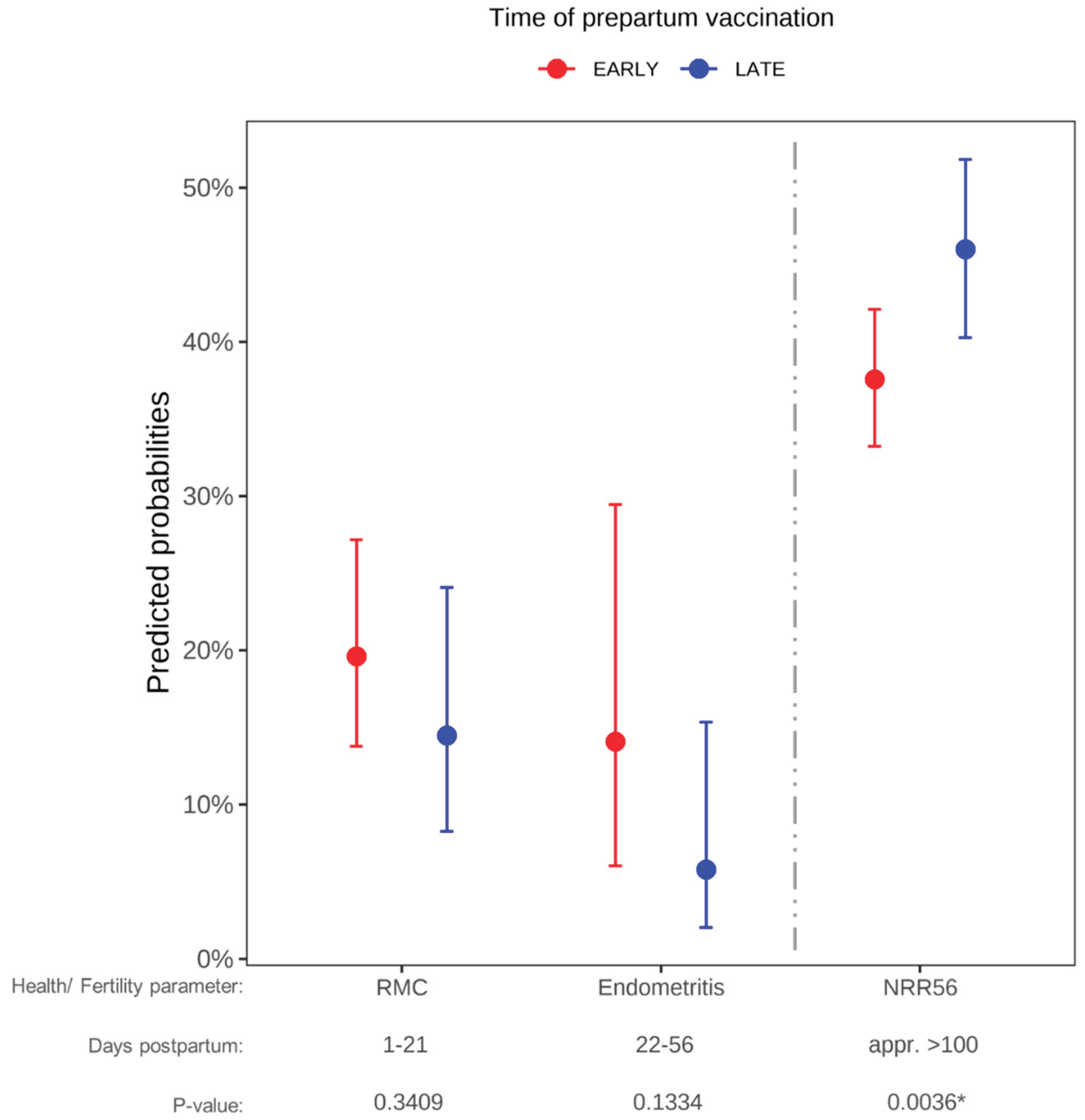

3.4. Time of Vaccination Affects Fertility in Non-Live Vaccinated Cows

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- de Bree, L.C.J.; Koeken, V.; Joosten, L.A.B.; Aaby, P.; Benn, C.S.; van Crevel, R.; Netea, M.G. Non-specific effects of vaccines: Current evidence and potential implications. Semin. Immunol. 2018, 39, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arega, S.M.; Knobel, D.L.; Toka, F.N.; Conan, A. Non-specific effects of veterinary vaccines: a systematic review. Vaccine 2022, 40, 1655–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benn, C.S.; Fisker, A.B.; Rieckmann, A.; Sørup, S.; Aaby, P. Vaccinology: time to change the paradigm? The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2020, 20, e274–e283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Casillas, A.; Rodriguez-Quintero, C.M.; Redwan, E.M.; Gupta, M.N.; Uversky, V.N.; Raszek, M. Do vaccines increase or decrease susceptibility to diseases other than those they protect against? Vaccine 2024, 42, 426–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra-Maupome, M.; Vang, D.X.; McGill, J.L. Aerosol vaccination with Bacille Calmette-Guerin induces a trained innate immune phenotype in calves. PloS one 2019, 14, e0212751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weikard, R.; Demasius, W.; Hadlich, F.; Kühn, C. Different Blood Cell-Derived Transcriptome Signatures in Cows Exposed to Vaccination Pre- or Postpartum. PloS one 2015, 10, e0136927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demasius, W.; Weikard, R.; Hadlich, F.; Müller, K.E.; Kühn, C. Monitoring the immune response to vaccination with an inactivated vaccine associated to bovine neonatal pancytopenia by deep sequencing transcriptome analysis in cattle. Veterinary research 2013, 44, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhn, C.; Zerbe, H.; Schuberth, H.-J.; Römer, A.; Kraatz-Van Egmond, D.; Wesenauer, C.; Resch, M.; Stoll, A.; Zablotski, Y. Prepartum Vaccination Against Neonatal Calf Diarrhea and Its Effect on Mammary Health and Milk Yield of Dairy Cows: A Retrospective Study Addressing Non-Specific Effects of Vaccination. Animals 2025, 15, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.I.; Rieger, R.H.; Dickens, C.M.; Schultz, R.D.; Aceto, H. Anti-bovine herpesvirus and anti-bovine viral diarrhea virus antibody responses in pregnant Holstein dairy cattle following administration of a multivalent killed virus vaccine. American Journal of Veterinary Research 2015, 76, 913–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidlund, J.; Gelalcha, B.D.; Gillespie, B.E.; Agga, G.E.; Schneider, L.; Swanson, S.M.; Frady, K.D.; Kerro Dego, O. Efficacy of novel staphylococcal surface associated protein vaccines against Staphylococcus aureus and non-aureus staphylococcal mastitis in dairy cows. Vaccine 2024, 42, 1247–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliá-Burchés, C.; Martínez-Varea, A. An Update on COVID-19 Vaccination and Pregnancy. Journal of Personalized Medicine 2023, 13, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaby, P.; Martins, C.L.; Ravn, H.; Rodrigues, A.; Whittle, H.C.; Benn, C.S. Is early measles vaccination better than later measles vaccination? Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2015, 109, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berendsen, M.L.T.; Smits, J.; Netea, M.G.; Van Der Ven, A. Non-specific Effects of Vaccines and Stunting: Timing May Be Essential. EBioMedicine 2016, 8, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menichetti, B.T.; Garcia-Guerra, A.; Lakritz, J.; Weiss, W.P.; Velez, J.S.; Bothe, H.; Merchan, D.; Schuenemann, G.M. Effects of prepartum vaccination timing relative to pen change with an acidogenic diet on serum and colostrum immunoglobulins in Holstein dairy cows. Journal of Dairy Science 2021, 104, 11072–11081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menichetti, B.T.; Garcia-Guerra, A.; Lakritz, J.; Weiss, W.P.; Velez, J.S.; Bothe, H.; Merchan, D.; Schuenemann, G.M. Effect of timing of prepartum vaccination relative to pen change with an acidogenic diet on lying time and metabolic profile in Holstein dairy cows. Journal of Dairy Science 2021, 104, 11059–11071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drackley, J.K. Biology of dairy cows during the transition period: the final frontier? Journal of Dairy Science 1999, 82, 2259–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopreiato, V.; Mezzetti, M.; Cattaneo, L.; Ferronato, G.; Minuti, A.; Trevisi, E. Role of nutraceuticals during the transition period of dairy cows: a review. Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology 2020, 11, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horst, E.A.; Kvidera, S.K.; Baumgard, L.H. Invited review: The influence of immune activation on transition cow health and performance-A critical evaluation of traditional dogmas. J Dairy Sci 2021, 104, 8380–8410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBlanc, S.J. Postpartum uterine disease and dairy herd reproductive performance: a review. The Veterinary Journal 2008, 176, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascottini, O.B.; LeBlanc, S.J. Modulation of immune function in the bovine uterus peripartum. Theriogenology 2020, 150, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheldon, I.M.; Molinari, P.C.C.; Ormsby, T.J.R.; Bromfield, J.J. Preventing postpartum uterine disease in dairy cattle depends on avoiding, tolerating and resisting pathogenic bacteria. Theriogenology 2020, 150, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, E. Drivers of Post-partum Uterine Disease in Dairy Cattle. Reproduction in Domestic Animals 2013, 48, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, V.S.; Silva, T.H. Adaptive immunity in the postpartum uterus: Potential use of vaccines to control metritis. Theriogenology 2020, 150, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheldon, I.M.; Lewis, G.S.; LeBlanc, S.; Gilbert, R.O. Defining postpartum uterine disease in cattle. Theriogenology 2006, 65, 1516–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeBlanc, S.J. Review: Postpartum reproductive disease and fertility in dairy cows. Animal 2023, 17 Suppl 1, 100781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeBlanc, S. Assessing the association of the level of milk production with reproductive performance in dairy cattle. The Journal of reproduction and development 2010, 56 Suppl, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghavi Hossein-Zadeh, N.; Ardalan, M. Cow-specific risk factors for retained placenta, metritis and clinical mastitis in Holstein cows. Vet Res Commun 2011, 35, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, T.J.; Guitian, J.; Fishwick, J.; Gordon, P.J.; Sheldon, I.M. Risk factors for clinical endometritis in postpartum dairy cattle. Theriogenology 2010, 74, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourichon, C.; Seegers, H.; Malher, X. Effect of disease on reproduction in the dairy cow: a meta-analysis. Theriogenology 2000, 53, 1729–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Team, R.C. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Machine Learning 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, I.J. The Interface Between Statistics and Philosophy of Science. Statistical Science 1988, 3, 386–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Cohen, P.; Chen, S. How Big is a Big Odds Ratio? Interpreting the Magnitudes of Odds Ratios in Epidemiological Studies. Communications in Statistics - Simulation and Computation 2010, 39, 860–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BfArM. Bovigen Scour. Available online: https://portal.dimdi.de/amguifree/am/docoutput/jpadocdisplay.xhtml?globalDocId=D177C92C25144319A39E604576AF1AF1&directdisplay=true&docid=1 (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- BfArM. Zusammenfassung der Merkmale des Tierarzneimittels. Available online: https://portal.dimdi.de/amispb/doc/pei/Web/2603670-spcde-20131101.pdf (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- BfArM. Gebrauchsinformation: Rotavec Corona. Available online: https://portal.dimdi.de/amispb/doc/pei/Web/2603419-palde-20100501.pdf (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Kreienbrock, L.; Pigeot, I.; Ahrens, W. Epidemiologische Methoden, 5 ed.; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Garzon, A.; Basbas, C.; Schlesener, C.; Silva-Del-Rio, N.; Karle, B.M.; Lima, F.S.; Weimer, B.C.; Pereira, R.V. WGS of intrauterine E. coli from cows with early postpartum uterine infection reveals a non-uterine specific genotype and virulence factors. mBio 2024, e0102724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammon, D.S.; Evjen, I.M.; Dhiman, T.R.; Goff, J.P.; Walters, J.L. Neutrophil function and energy status in Holstein cows with uterine health disorders. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2006, 113, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, E.S.; Gomes, G.; Greco, L.F.; Cerri, R.L.A.; Vieira-Neto, A.; Monteiro, P.L.J.; Lima, F.S.; Bisinotto, R.S.; Thatcher, W.W.; Santos, J.E.P. Carryover effect of postpartum inflammatory diseases on developmental biology and fertility in lactating dairy cows. Journal of Dairy Science 2016, 99, 2201–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascottini, O.B.; Leroy, J.; Opsomer, G. Maladaptation to the transition period and consequences on fertility of dairy cows. Reprod Domest Anim 2022, 57, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emanuelson, U.; Oltenacu, P.A.; Gröhn, Y.T. Nonlinear mixed model analyses of five production disorders of dairy cattle. J Dairy Sci 1993, 76, 2765–2772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praeger, W. Untersuchungen zur Auswirkungen von prophylaktischen Maßnahmen zum Mutterschutz bei Milchkühen auf die Gesundheit der Kälber und der Mütter in der Folgelaktation. 2020.

- Kelton, D.F.; Lissemore, K.D.; Martin, R.E. Recommendations for recording and calculating the incidence of selected clinical diseases of dairy cattle. J Dairy Sci 1998, 81, 2502–2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenz, J.R.; Giebel, S.K. Retrospective evaluation of health event data recording on 50 dairies using Dairy Comp 305. Journal of Dairy Science 2012, 95, 4699–4706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, L.; Campos-Chillon, F.; Sargolzaei, M.; Peterson, D.G.; Sprayberry, K.A.; McArthur, G.; Anderson, P.; Golden, B.; Pokharel, S.; Abo-Ismail, M.K. Molecular Mechanisms Associated with the Development of the Metritis Complex in Dairy Cattle. Genes (Basel) 2024, 15, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunert, E. Buiatrik: Euterkrankheiten, Geburtshilfe und Gynäkologie, Andrologie und Besamung; Schaper: Hannover, Germany, 1996; p. 320. [Google Scholar]

- Prunner, I.; Wagener, K.; Pothmann, H.; Ehling-Schulz, M.; Drillich, M. Risk factors for uterine diseases on small- and medium-sized dairy farms determined by clinical, bacteriological, and cytological examinations. Theriogenology 2014, 82, 857–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niozas, G.; Tsousis, G.; Malesios, C.; Steinhöfel, I.; Boscos, C.; Bollwein, H.; Kaske, M. Extended lactation in high-yielding dairy cows. II. Effects on milk production, udder health, and body measurements. Journal of dairy science 2019, 102, 811–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niozas, G.; Tsousis, G.; Steinhöfel, I.; Brozos, C.; Römer, A.; Wiedemann, S.; Bollwein, H.; Kaske, M. Extended lactation in high-yielding dairy cows. I. Effects on reproductive measurements. Journal of dairy science 2019, 102, 799–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawson, L.G.; Bruun, J.; Coelli, T.; Agger, J.F.; Lund, M. Relationships of efficiency to reproductive disorders in Danish milk production: a stochastic frontier analysis. J Dairy Sci 2004, 87, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rearte, R.; LeBlanc, S.J.; Corva, S.G.; de la Sota, R.L.; Lacau-Mengido, I.M.; Giuliodori, M.J. Effect of milk production on reproductive performance in dairy herds. Journal of Dairy Science 2018, 101, 7575–7584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, J.G.; Green, M.J. Use of early lactation milk recording data to predict the calving to conception interval in dairy herds. J Dairy Sci 2016, 99, 4699–4706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madouasse, A.; Huxley, J.N.; Browne, W.J.; Bradley, A.J.; Dryden, I.L.; Green, M.J. Use of individual cow milk recording data at the start of lactation to predict the calving to conception interval. Journal of Dairy Science 2010, 93, 4677–4690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Time of prepartum vaccination | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NON VACCa | EARLYb | LATEc | EARLY or LATEd | Total | ||

| Type of vaccine | NON VACCa | 57,166 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 57,166 |

| VACCh (N=63,228) | ||||||

| NON LIVEe | 0 | 11,238 | 6,336 | 18,199 | 35,773 | |

| MIXEDf | 0 | 519 | 7,833 | 0 | 8,352 | |

| UNKNOWNg | 0 | 18,876 | 0 | 227 | 19,103 | |

| Total | 57,166 | 30,633 | 14,169 | 18,426 | 120,394 | |

| Primiparous cows | Multiparous cows | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

n: |

NON VACCa 27,081 |

VACCb 19,028 |

NON VACCa 30,085 |

VACCb 44,200 |

| ECM 305c | 8,683 | 8,683 | 10,968 | 10,371 |

| Time to first serviced | 73 | 72 | 75 | 75 |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).