Submitted:

14 August 2025

Posted:

18 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

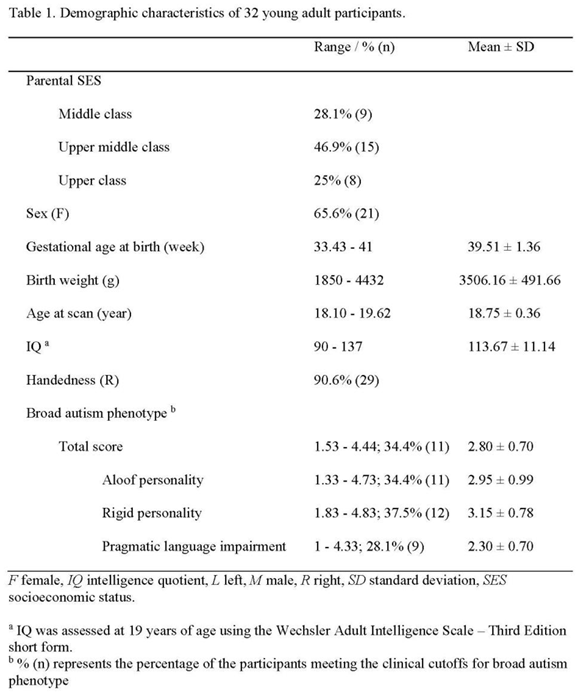

Participants

Ethical Approval

Broad Autism Phenotype

MRI Data Acquisition

MRI Data Preprocessing

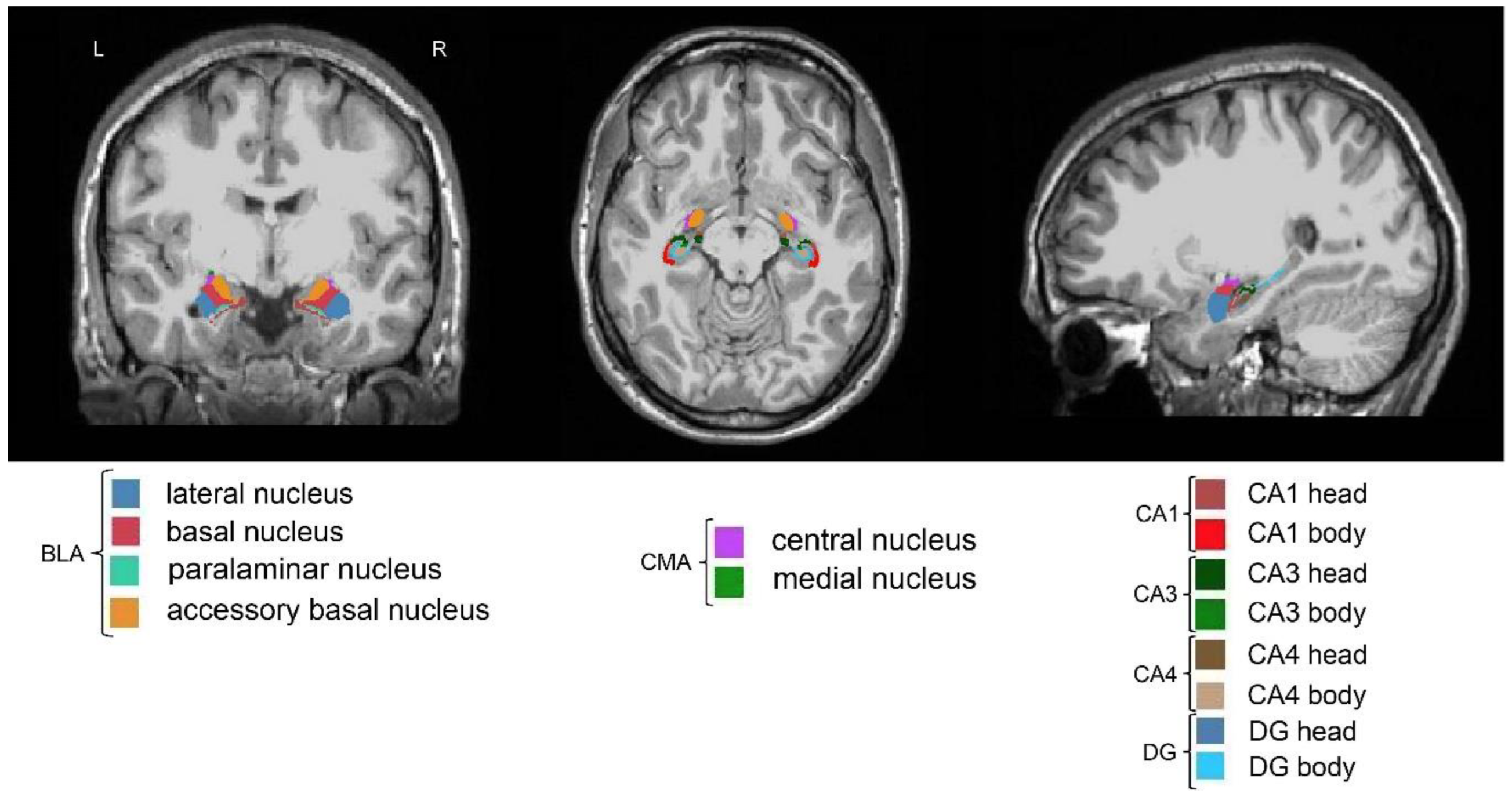

FreeSurfer Segmentation

Volume Analysis

Functional Connectivity Analysis

Results

Associations Between Amygdala and Hippocampal Volumes and BAP Total Score

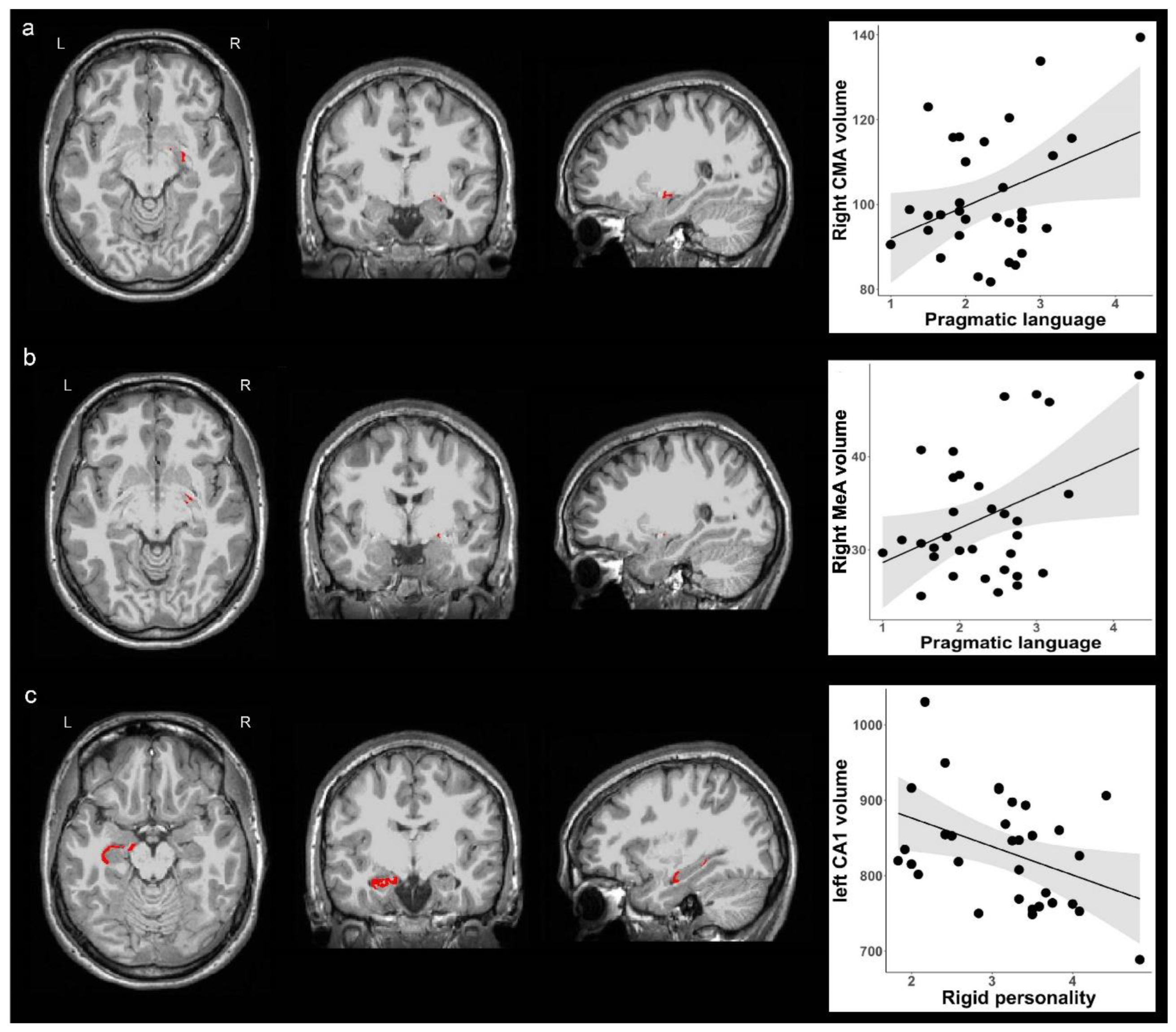

Associations Between Amygdala and Hippocampal Volumes and BAP Subdomain Scores

Associations Between Amygdala and Hippocampal Functional Connectivity and BAP Total Score

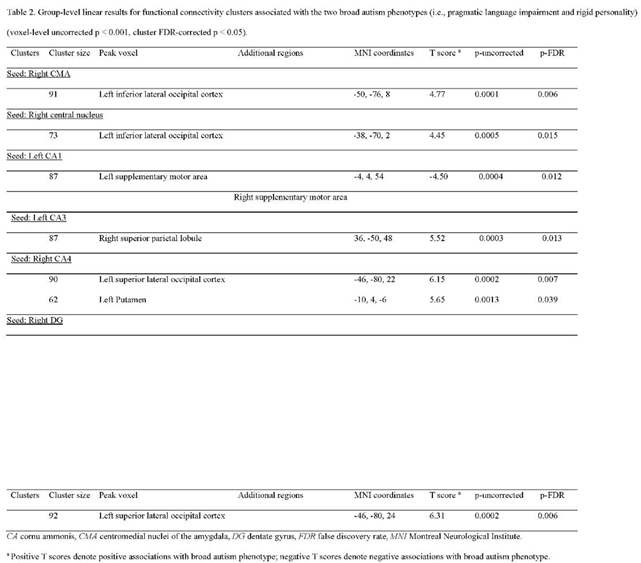

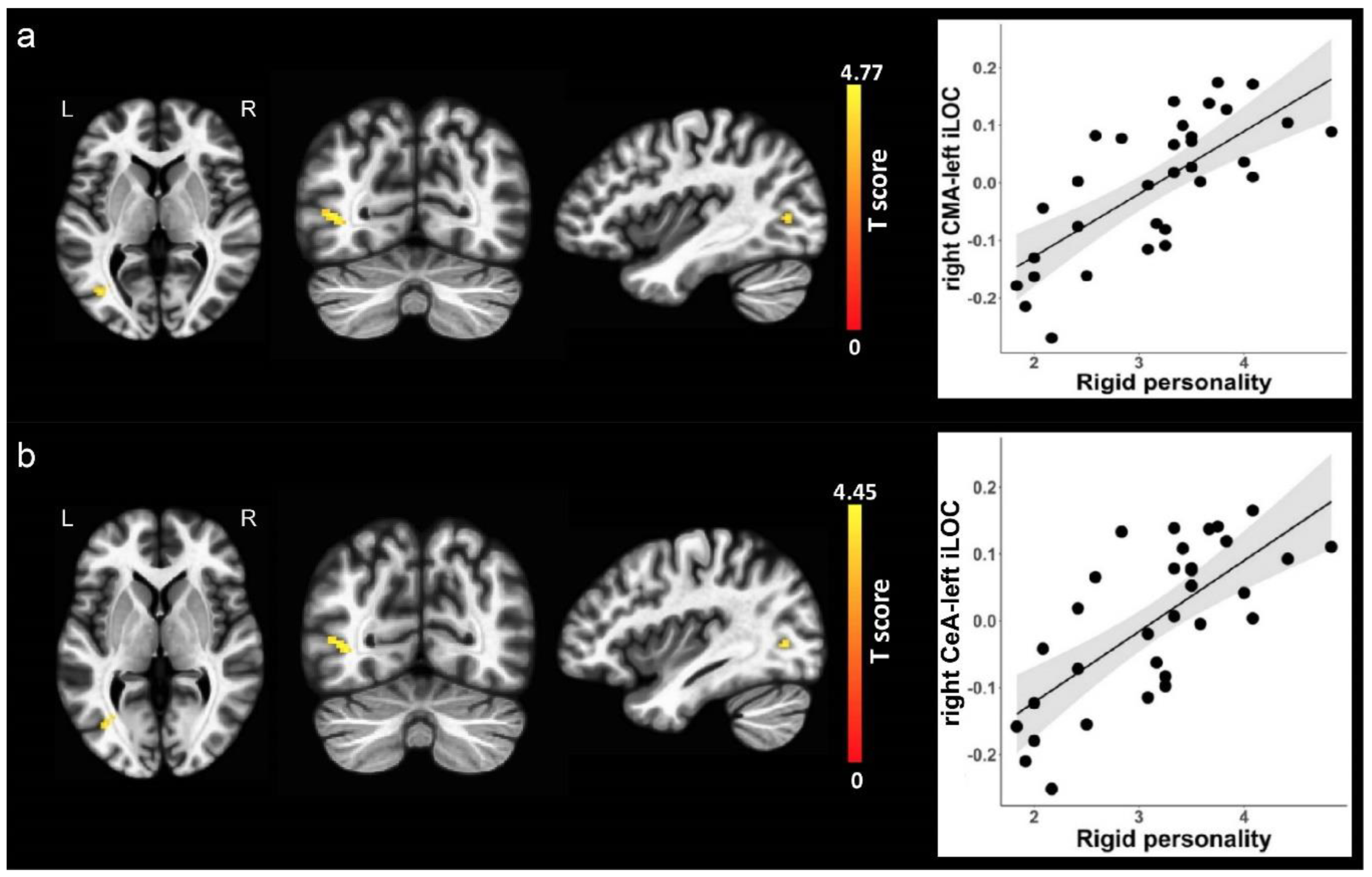

Associations Between Amygdala and Hippocampal Functional Connectivity and BAP Subdomain Scores

Discussion

Author Contributions

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Association, A. P. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. DSM-5, 5th ed 21 (2013).

- Uljarević, M. et al. Exploring Social Subtypes in Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Preliminary Study. Autism research : official journal of the International Society for Autism Research 13, 1335-1342 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Constantino, J. N. & Todd, R. D. Autistic traits in the general population: a twin study. Archives of general psychiatry 60, 524-530 (2003). [CrossRef]

- Robinson, E. B. et al. Evidence that autistic traits show the same etiology in the general population and at the quantitative extremes (5%, 2.5%, and 1%). Archives of general psychiatry 68, 1113-1121 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Lundström, S. et al. Autism spectrum disorders and autistic like traits: similar etiology in the extreme end and the normal variation. Archives of general psychiatry 69, 46-52 (2012). [CrossRef]

- De Groot, K. & Van Strien, J. W. Evidence for a broad autism phenotype. Advances in Neurodevelopmental Disorders 1, 129-140 (2017).

- Sasson, N. J. et al. The broad autism phenotype questionnaire: prevalence and diagnostic classification. Autism research : official journal of the International Society for Autism Research 6, 134-143 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Elsabbagh, M. et al. Global prevalence of autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. Autism research : official journal of the International Society for Autism Research 5, 160-179 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Ronald, A. & Hoekstra, R. A. Autism spectrum disorders and autistic traits: a decade of new twin studies. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 156b, 255-274 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Hurley, R. S., Losh, M., Parlier, M., Reznick, J. S. & Piven, J. The broad autism phenotype questionnaire. Journal of autism and developmental disorders 37, 1679-1690 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, R., Paliwal, J. K. & Kuhad, A. Neuropsychopathology of Autism Spectrum Disorder: Complex Interplay of Genetic, Epigenetic, and Environmental Factors. Adv Neurobiol 24, 97-141 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Chen, L. C. et al. Association of parental depression with offspring attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder: A nationwide birth cohort study. Journal of affective disorders 277, 109-114 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Gao, L. et al. Association between Prenatal Environmental Factors and Child Autism: A Case Control Study in Tianjin, China. Biomedical and environmental sciences : BES 28, 642-650 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Say, G. N., Karabekiroğlu, K., Babadağı, Z. & Yüce, M. Maternal stress and perinatal features in autism and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics international : official journal of the Japan Pediatric Society 58, 265-269 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y. et al. [Pregnancy-related anxiety and subthreshold autism trait in preschool children based a birth cohort study]. Zhonghua yu fang yi xue za zhi [Chinese journal of preventive medicine] 50, 118-122 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Walder, D. J. et al. Prenatal maternal stress predicts autism traits in 6½ year-old children: Project Ice Storm. Psychiatry research 219, 353-360 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Laplante, D. P., Elgbeili, G. & King, S. Preconception and prenatal maternal stress are associated with broad autism phenotype in young adults: Project Ice Storm. J Dev Orig Health Dis, 1-9 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Cao-Lei L, E. G., Laplante D, Szyf M, King S. DNA methylation mediates the association between prenatal maternal stress and the broad autism phenotype in adolescence: Project Ice Storm. Biology. Submitted. (2024).

- Cortes Hidalgo, A. P. et al. Observed infant-parent attachment and brain morphology in middle childhood- A population-based study. Dev Cogn Neurosci 40, 100724 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Gotts, S. J. et al. Fractionation of social brain circuits in autism spectrum disorders. Brain : a journal of neurology 135, 2711-2725 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Ochsner, K. N. et al. Bottom-up and top-down processes in emotion generation: common and distinct neural mechanisms. Psychol Sci 20, 1322-1331 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Emery, N. J. et al. The effects of bilateral lesions of the amygdala on dyadic social interactions in rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta). Behav Neurosci 115, 515-544 (2001).

- Amunts, K. et al. Cytoarchitectonic mapping of the human amygdala, hippocampal region and entorhinal cortex: intersubject variability and probability maps. Anat Embryol (Berl) 210, 343-352 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Odriozola, P. et al. Atypical frontoamygdala functional connectivity in youth with autism. Developmental cognitive neuroscience 37, 100603 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Rausch, A. et al. Altered functional connectivity of the amygdaloid input nuclei in adolescents and young adults with autism spectrum disorder: a resting state fMRI study. Molecular autism 7, 13 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Sah, P., Faber, E. S., Lopez De Armentia, M. & Power, J. The amygdaloid complex: anatomy and physiology. Physiol Rev 83, 803-834 (2003). [CrossRef]

- Pessoa, L. Emotion and cognition and the amygdala: from "what is it?" to "what's to be done?". Neuropsychologia 48, 3416-3429 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Laurita, A. C. & Nathan Spreng, R. The hippocampus and social cognition. The hippocampus from cells to systems: Structure, connectivity, and functional contributions to memory and flexible cognition, 537-558 (2017).

- Rubin, R. D., Watson, P. D., Duff, M. C. & Cohen, N. J. The role of the hippocampus in flexible cognition and social behavior. Frontiers in human neuroscience 8, 742 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Schafer, M. & Schiller, D. The Hippocampus and Social Impairment in Psychiatric Disorders. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 83, 105-118 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Banker, S. M., Gu, X., Schiller, D. & Foss-Feig, J. H. Hippocampal contributions to social and cognitive deficits in autism spectrum disorder. Trends Neurosci 44, 793-807 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Ergorul, C. & Eichenbaum, H. The hippocampus and memory for "what," "where," and "when". Learn Mem 11, 397-405 (2004). [CrossRef]

- Norris, J. E. & Maras, K. Supporting autistic adults' episodic memory recall in interviews: The role of executive functions, theory of mind, and language abilities. Autism : the international journal of research and practice 26, 513-524 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Naito, M., Hotta, C. & Toichi, M. Development of Episodic Memory and Foresight in High-Functioning Preschoolers with ASD. Journal of autism and developmental disorders 50, 529-539 (2020). [CrossRef]

- South, M., Newton, T. & Chamberlain, P. D. Delayed reversal learning and association with repetitive behavior in autism spectrum disorders. Autism research : official journal of the International Society for Autism Research 5, 398-406 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, T., Yokota, S., Matsuzaki, Y. & Kawashima, R. Intrinsic hippocampal functional connectivity underlying rigid memory in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: A case-control study. Autism : the international journal of research and practice 25, 1901-1912 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Mueller, S. G., Chao, L. L., Berman, B. & Weiner, M. W. Evidence for functional specialization of hippocampal subfields detected by MR subfield volumetry on high resolution images at 4 T. Neuroimage 56, 851-857 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Groen, W., Teluij, M., Buitelaar, J. & Tendolkar, I. Amygdala and hippocampus enlargement during adolescence in autism. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 49, 552-560 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Nordahl, C. W. et al. Increased rate of amygdala growth in children aged 2 to 4 years with autism spectrum disorders: a longitudinal study. Archives of general psychiatry 69, 53-61 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z. et al. Alterations in volumes and MRI features of amygdala in Chinese autistic preschoolers associated with social and behavioral deficits. Brain Imaging Behav 12, 1814-1821 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Barnea-Goraly, N. et al. A preliminary longitudinal volumetric MRI study of amygdala and hippocampal volumes in autism. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 48, 124-128 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Rojas, D. C. et al. Regional gray matter volumetric changes in autism associated with social and repetitive behavior symptoms. BMC Psychiatry 6, 56 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q., Zuo, C., Liao, S., Long, Y. & Wang, Y. Abnormal development pattern of the amygdala and hippocampus from childhood to adulthood with autism. J Clin Neurosci 78, 327-332 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Aylward, E. H. et al. MRI volumes of amygdala and hippocampus in non-mentally retarded autistic adolescents and adults. Neurology 53, 2145-2150 (1999). [CrossRef]

- Nacewicz, B. M. et al. Amygdala volume and nonverbal social impairment in adolescent and adult males with autism. Archives of general psychiatry 63, 1417-1428 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Howard, M. A. et al. Convergent neuroanatomical and behavioural evidence of an amygdala hypothesis of autism. Neuroreport 11, 2931-2935 (2000). [CrossRef]

- Haznedar, M. M. et al. Limbic circuitry in patients with autism spectrum disorders studied with positron emission tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. Am J Psychiatry 157, 1994-2001 (2000). [CrossRef]

- Piven, J., Bailey, J., Ranson, B. J. & Arndt, S. No difference in hippocampus volume detected on magnetic resonance imaging in autistic individuals. Journal of autism and developmental disorders 28, 105-110 (1998). [CrossRef]

- Schumann, C. M. et al. The amygdala is enlarged in children but not adolescents with autism; the hippocampus is enlarged at all ages. J Neurosci 24, 6392-6401 (2004). [CrossRef]

- Seguin, D. et al. Amygdala subnuclei development in adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: Association with social communication and repetitive behaviors. Brain Behav 11, e2299 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Li, G. et al. Volumetric Analysis of Amygdala and Hippocampal Subfields for Infants with Autism. Journal of autism and developmental disorders (2022). [CrossRef]

- Nees, F. et al. Global and Regional Structural Differences and Prediction of Autistic Traits during Adolescence. Brain Sci 12 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Iidaka, T., Miyakoshi, M., Harada, T. & Nakai, T. White matter connectivity between superior temporal sulcus and amygdala is associated with autistic trait in healthy humans. Neurosci Lett 510, 154-158 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Kleinhans, N. M. et al. Subregional differences in intrinsic amygdala hyperconnectivity and hypoconnectivity in autism spectrum disorder. Autism research : official journal of the International Society for Autism Research 9, 760-772 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Piven, J. The broad autism phenotype: a complementary strategy for molecular genetic studies of autism. American journal of medical genetics 105, 34-35 (2001).

- Esteban, O. et al. fMRIPrep: a robust preprocessing pipeline for functional MRI. Nature methods 16, 111-116 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Avants, B. B., Epstein, C. L., Grossman, M. & Gee, J. C. Symmetric diffeomorphic image registration with cross-correlation: evaluating automated labeling of elderly and neurodegenerative brain. Medical image analysis 12, 26-41 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Brady, M. & Smith, S. Segmentation of brain MR images through a hidden Markov random field model and the expectation-maximization algorithm. IEEE transactions on medical imaging 20, 45-57 (2001). [CrossRef]

- Jenkinson, M. & Smith, S. A global optimisation method for robust affine registration of brain images. Medical image analysis 5, 143-156 (2001). [CrossRef]

- Pruim, R. H. R. et al. ICA-AROMA: A robust ICA-based strategy for removing motion artifacts from fMRI data. Neuroimage 112, 267-277 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Fischl, B. FreeSurfer. NeuroImage 62, 774-781 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Saygin, Z. M. et al. High-resolution magnetic resonance imaging reveals nuclei of the human amygdala: manual segmentation to automatic atlas. NeuroImage 155, 370-382 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, J. E. et al. A computational atlas of the hippocampal formation using ex vivo, ultra-high resolution MRI: Application to adaptive segmentation of in vivo MRI. NeuroImage 115, 117-137 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Li, X. et al. Neural correlates of disaster-related prenatal maternal stress in young adults from Project Ice Storm: Focus on amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex. Front Hum Neurosci 17, 1094039 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Jalbrzikowski, M. et al. Development of White Matter Microstructure and Intrinsic Functional Connectivity Between the Amygdala and Ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex: Associations With Anxiety and Depression. Biological psychiatry 82, 511-521 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Whitfield-Gabrieli, S. & Nieto-Castanon, A. Conn: a functional connectivity toolbox for correlated and anticorrelated brain networks. Brain connectivity 2, 125-141 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Landa, R. et al. Social language use in parents of autistic individuals. Psychological medicine 22, 245-254 (1992). [CrossRef]

- Biggs, L. M. & Meredith, M. Functional connectivity of intercalated nucleus with medial amygdala: A circuit relevant for chemosignal processing. IBRO Neurosci Rep 12, 170-181 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Courchesne, E. et al. Unusual brain growth patterns in early life in patients with autistic disorder: an MRI study. Neurology 57, 245-254 (2001). [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M. S., Davis, R., Karmiloff-Smith, A., Knowland, V. C. & Charman, T. The over-pruning hypothesis of autism. Dev Sci 19, 284-305 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Yankowitz, L. D. et al. Evidence against the "normalization" prediction of the early brain overgrowth hypothesis of autism. Mol Autism 11, 51 (2020). [CrossRef]

- van de Ven, V., Waldorp, L. & Christoffels, I. Hippocampus plays a role in speech feedback processing. Neuroimage 223, 117319 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Duff, M. C. & Brown-Schmidt, S. The hippocampus and the flexible use and processing of language. Frontiers in human neuroscience 6, 69 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Bonhage, C. E., Mueller, J. L., Friederici, A. D. & Fiebach, C. J. Combined eye tracking and fMRI reveals neural basis of linguistic predictions during sentence comprehension. Cortex 68, 33-47 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Covington, N. V. & Duff, M. C. Expanding the Language Network: Direct Contributions from the Hippocampus. Trends Cogn Sci 20, 869-870 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Piai, V. et al. Direct brain recordings reveal hippocampal rhythm underpinnings of language processing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113, 11366-11371 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Hertrich, I., Dietrich, S. & Ackermann, H. The role of the supplementary motor area for speech and language processing. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews 68, 602-610 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Kurczek, J. & Duff, M. C. Cohesion, coherence, and declarative memory: Discourse patterns in individuals with hippocampal amnesia. Aphasiology 25, 700-712 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Zammit, A. R. et al. Roles of hippocampal subfields in verbal and visual episodic memory. Behav Brain Res 317, 157-162 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Buckner, R. L. The role of the hippocampus in prediction and imagination. Annual review of psychology 61, 27-48, c21-28 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Baas, D. et al. Evidence of altered cortical and amygdala activation during social decision-making in schizophrenia. Neuroimage 40, 719-727 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Viñas-Guasch, N. & Wu, Y. J. The role of the putamen in language: a meta-analytic connectivity modeling study. Brain structure & function 222, 3991-4004 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Farley, S. J., Albazboz, H., De Corte, B. J., Radley, J. J. & Freeman, J. H. Amygdala central nucleus modulation of cerebellar learning with a visual conditioned stimulus. Neurobiol Learn Mem 150, 84-92 (2018). [CrossRef]

- McKinnon, C. J. et al. Restricted and Repetitive Behavior and Brain Functional Connectivity in Infants at Risk for Developing Autism Spectrum Disorder. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging 4, 50-61 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Bishop, S. L. et al. Subcategories of restricted and repetitive behaviors in children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of autism and developmental disorders 43, 1287-1297 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Bartsch, T., Döhring, J., Rohr, A., Jansen, O. & Deuschl, G. CA1 neurons in the human hippocampus are critical for autobiographical memory, mental time travel, and autonoetic consciousness. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108, 17562-17567 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Havekes, R., Nijholt, I. M., Luiten, P. G. & Van der Zee, E. A. Differential involvement of hippocampal calcineurin during learning and reversal learning in a Y-maze task. Learn Mem 13, 753-759 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Wagner, A. D., Shannon, B. J., Kahn, I. & Buckner, R. L. Parietal lobe contributions to episodic memory retrieval. Trends Cogn Sci 9, 445-453 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Dimsdale-Zucker, H. R., Ritchey, M., Ekstrom, A. D., Yonelinas, A. P. & Ranganath, C. CA1 and CA3 differentially support spontaneous retrieval of episodic contexts within human hippocampal subfields. Nat Commun 9, 294 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Travis, S. G. et al. High field structural MRI reveals specific episodic memory correlates in the subfields of the hippocampus. Neuropsychologia 53, 233-245 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Ho Kim, J. et al. Proteome-wide characterization of signalling interactions in the hippocampal CA4/DG subfield of patients with Alzheimer's disease. Sci Rep 5, 11138 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Duvernoy, H. M. The human hippocampus: an atlas of applied anatomy. (JF Bergmann-Verlag, 2013).

- Piven, J. et al. Personality characteristics of the parents of autistic individuals. Psychological medicine 24, 783-795 (1994). [CrossRef]

- Losh, M. et al. Defining genetically meaningful language and personality traits in relatives of individuals with fragile X syndrome and relatives of individuals with autism. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 159b, 660-668 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Blundell, J. et al. Neuroligin-1 deletion results in impaired spatial memory and increased repetitive behavior. J Neurosci 30, 2115-2129 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Schacter, D. L., Guerin, S. A. & St Jacques, P. L. Memory distortion: an adaptive perspective. Trends Cogn Sci 15, 467-474 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Litwińczuk, M. C., Muhlert, N., Cloutman, L., Trujillo-Barreto, N. & Woollams, A. Combination of structural and functional connectivity explains unique variation in specific domains of cognitive function. Neuroimage 262, 119531 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Uddin, L. Q. Complex relationships between structural and functional brain connectivity. Trends Cogn Sci 17, 600-602 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Mansour, L. S., Tian, Y., Yeo, B. T. T., Cropley, V. & Zalesky, A. High-resolution connectomic fingerprints: Mapping neural identity and behavior. Neuroimage 229, 117695 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Birn, R. M. et al. The effect of scan length on the reliability of resting-state fMRI connectivity estimates. Neuroimage 83, 550-558 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Nag, H. E., Nordgren, A., Anderlid, B. M. & Nærland, T. Reversed gender ratio of autism spectrum disorder in Smith-Magenis syndrome. Mol Autism 9, 1 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Bolton, P. et al. A case-control family history study of autism. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 35, 877-900 (1994). [CrossRef]

- Piven, J., Palmer, P., Jacobi, D., Childress, D. & Arndt, S. Broader autism phenotype: evidence from a family history study of multiple-incidence autism families. Am J Psychiatry 154, 185-190 (1997). [CrossRef]

- Pickles, A. et al. Variable expression of the autism broader phenotype: findings from extended pedigrees. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 41, 491-502 (2000).

- Schwichtenberg, A. J., Young, G. S., Sigman, M., Hutman, T. & Ozonoff, S. Can family affectedness inform infant sibling outcomes of autism spectrum disorders? J Child Psychol Psychiatry 51, 1021-1030 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Wheelwright, S., Auyeung, B., Allison, C. & Baron-Cohen, S. Defining the broader, medium and narrow autism phenotype among parents using the Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ). Mol Autism 1, 10 (2010). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).