1. Introduction

The discipline of economics has undergone periodic transformations in its fundamental assumptions and objectives. From Adam Smith’s An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776), which provided the philosophical basis for capitalism, to the contemporary social business models championed by Nobel laureate Mohammad Yunus (2007, 2010, 2017), the concept of economic value has been redefined to encompass more than profit. Smith’s “invisible hand” framed self-interest as a driver of efficiency and resource allocation, while acknowledging the role of moral sentiments (Smith, 1759/2002). However, the realities of the 21st century—marked by widening inequality, climate crisis, and persistent poverty—highlight the limitations of Capitalism I, which prioritizes efficiency over inclusivity (Hasnat et al., 2025; Santos, 2012).

Yunus’s concept of social business offers a model of Capitalism II: a form of market capitalism in which enterprises are financially sustainable but reinvest profits to solve social and environmental problems rather than maximize shareholder wealth (Yunus, 2007, 2010). This transition is not a rejection of market principles but a reorientation toward collective well-being. The aim of this paper is to theorize a global framework for implementing social business capitalism as a systemic response to the failures of Capitalism I, with explicit alignment to the SDGs.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Adam Smith and Moral Capitalism

Adam Smith’s dual works—The Wealth of Nations (1776) and The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759/2002)—together portray a complex view of human behavior, in which economic actors pursue self-interest but are also guided by moral considerations. While The Wealth of Nations is often interpreted as legitimizing competitive, profit-maximizing markets, Smith acknowledged that markets function best within an ethical framework. This recognition of moral responsibility offers a conceptual bridge to contemporary debates about embedding social objectives into capitalism (Elahi & Islam, 2003; Farooq & Ahmad, 2022).

2.2. Critiques and Limitations of Capitalism I

The model that emerged from classical and neoclassical economics—here referred to as Capitalism I—has produced unprecedented economic growth but also entrenched the “90/10 paradox,” in which 90% of resources are concentrated in the hands of 10% of the population (Hasnat et al., 2025). This concentration generates negative externalities including environmental degradation, unemployment, and systemic deprivation (Molla et al., 2014). Welfare states have attempted to mitigate these effects, yet budget constraints and political shifts often erode social protections (Santos, 2012).

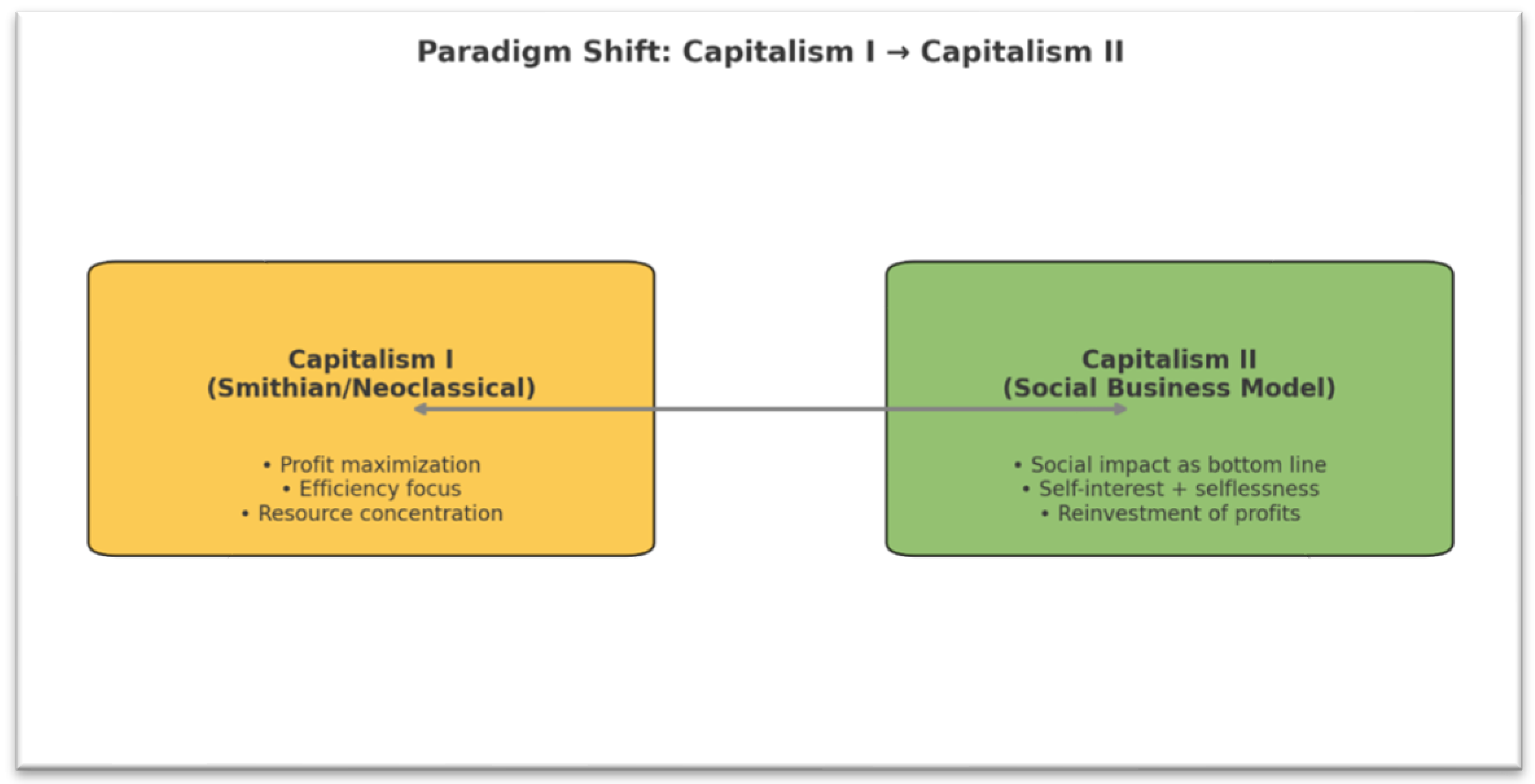

2.3. The Paradigm Shift to Capitalism II

Drawing on Kuhn’s (1962) theory of scientific revolutions, the transition to Capitalism II can be seen as a paradigmatic shift from a purely self-interest-based economic model to one that institutionalizes selflessness. Yunus (2007, 2010) argues that humans are not solely motivated by profit but also by the desire to contribute positively to society. Social business operationalizes this dual motivation by creating enterprises that are financially sustainable yet dedicated to solving social problems. This approach aligns with broader calls in the literature for hybrid organizational forms that bridge market efficiency with social equity (Santos, 2012; Andreoli, 2022).

2.4. Social Business in the Context of Sustainable Development

Social business aligns directly with the SDGs, particularly in addressing poverty (SDG 1), promoting decent work (SDG 8), reducing inequalities (SDG 10), and fostering partnerships (SDG 17). Yunus’s initiatives—ranging from microfinance through Grameen Bank to renewable energy via Grameen Shakti—exemplify how market-based solutions can target social needs while remaining sustainable (Yunus, 2007, 2010; Yunus, 2017). Empirical studies from Bangladesh and beyond suggest that social businesses can achieve measurable social impact without relying on continuous charitable subsidies (Huda, 2024; Qudrat-I Elahi & Rahman, 2006).

3. Theoretical Framework

3.1. Capitalism I: Market Efficiency and its Discontents

Capitalism I, as developed from Smithian economics and expanded through neoclassical theory, prioritizes market efficiency, competition, and the maximization of shareholder value. While this system has produced economic growth, it has also generated structural inequalities, resource concentration, and environmental degradation (Hasnat et al., 2025; Molla et al., 2014). Externalities—including pollution, social disruption, and unemployment—are often excluded from pricing mechanisms, leading to what Yunus (2010) terms “systemic deprivation.”

3.2. Capitalism II: Embedding Social Purpose in Market Systems

Capitalism II retains the market’s allocative mechanisms but redefines the purpose of enterprise: the bottom line becomes societal benefit rather than private gain. This transformation rests on a revised conception of human nature that recognizes both self-interest and selflessness as coexisting motivations (Yunus, 2007). Profit becomes an intermediate goal to ensure sustainability rather than an end in itself (Santos, 2012). In this sense, Capitalism II is not socialism—it is a hybrid market system that aligns entrepreneurial innovation with public good delivery.

3.3. Self-Interest, Selflessness, and the Paradigm Shift

Yunus’s approach challenges the homo economicus assumption by positing that individuals can derive utility from altruistic impact (Andreoli, 2022). In the language of Kuhn’s (1962) paradigm shifts, this represents a move from a single-variable utility model (profit) to a multi-variable one (profit + social impact). The shift is not merely rhetorical—it demands new institutional structures, funding mechanisms, and performance metrics to operationalize selflessness in business.

Figure 1.

Capitalism I to Capitalism II.

Figure 1.

Capitalism I to Capitalism II.

4. Models of Social Business

The social business model is defined by two core principles: (1) it operates as a market-based enterprise offering goods or services, and (2) profits are reinvested to further the social mission rather than distributed to investors (Yunus, 2010). Below are some key examples, drawn from models mentioned in Yunus’s books.

4.1. Grameen-Danone Foods Ltd. (Nutrition for Children)

Established in partnership with Groupe Danone in 2006, this initiative addresses child malnutrition in rural Bangladesh by producing fortified yogurt at an affordable price point (Yunus, 2007). The product is distributed through local women entrepreneurs, enhancing both nutrition and livelihoods. The enterprise measures success by the number of children receiving adequate nutrition and reductions in malnutrition-related illnesses (Huda, 2024).

4.2. Grameen-Veolia Water Ltd. (Access to Safe Water)

This joint venture with Veolia Water focuses on providing arsenic-free drinking water to rural communities at a price affordable to the poor. The model employs community-based distribution systems and aims to reduce waterborne diseases while maintaining financial sustainability (Yunus, 2010; Qudrat-I Elahi & Rahman, 2006).

4.3. Grameen-BASF (Disease Prevention through Mosquito Nets)

Partnering with BASF, this project manufactures and distributes insecticide-treated mosquito nets to prevent malaria and other vector-borne diseases. The initiative integrates local production, creating jobs while reducing disease prevalence (Yunus, 2010).

4.4. Grameen-Intel (ICT for Healthcare Access)

Launched with Intel Corporation, this program leverages information and communication technologies to deliver remote health consultations and advice. It addresses the gap in rural healthcare accessibility and tracks impacts in terms of consultations provided and preventable diseases averted (Yunus, 2010).

4.5. Grameen-Adidas (Affordable Footwear)

In collaboration with Adidas, this venture produces low-cost shoes to prevent parasitic diseases caused by walking barefoot. The program combines public health outcomes with dignified access to quality footwear for low-income communities (Yunus, 2010).

4.6. Grameen Shakti (Renewable Energy for Rural Communities)

Founded in 1996, Grameen Shakti provides solar home systems to off-grid rural households, promoting energy access and reducing reliance on kerosene (Yunus, 2007). The initiative aligns with SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy) and demonstrates the scalability of renewable energy in low-income contexts (Santos, 2012).

4.7. Grameen Bank (Microfinance for Poverty Reduction)

The flagship microfinance model offers collateral-free loans to the poor, particularly women, to enable entrepreneurial activity. Empirical evidence suggests significant impacts on poverty reduction, education, and women’s empowerment (Huda, 2024; Qudrat-I Elahi & Rahman, 2006).

4.8. Grameen Eye Care Hospitals (Affordable Eye Health Services)

These hospitals offer low-cost, high-quality eye care to underserved populations, cross-subsidizing costs through a tiered pricing model. This approach directly contributes to SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being) (Yunus, 2017).

4.9. Grameen Telecom (Mobile Connectivity for Rural Areas)

Through its Village Phone program, Grameen Telecom has enabled rural women to operate mobile phone services in their communities, enhancing communication, market access, and emergency response capabilities (Yunus, 2007).

Table 1.

Social Business Model and Mechanism.

Table 1.

Social Business Model and Mechanism.

| Social Business Model |

Social Need |

Business Mechanism |

Primary SDG Targets |

Impact Indicators |

| Grameen-Danone Foods Ltd. |

Child malnutrition |

Fortified yogurt sold at low cost via local women entrepreneurs |

SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), SDG 3 (Good Health) |

Reduced child malnutrition rates; local income generation |

| Grameen-Veolia Water Ltd. |

Unsafe drinking water |

Community-based arsenic-free water supply systems |

SDG 3 (Good Health), SDG 6 (Clean Water) |

Lower incidence of waterborne diseases |

| Grameen-BASF |

Vector-borne diseases |

Locally produced insecticide-treated mosquito nets |

SDG 3 (Good Health) |

Reduced malaria and dengue cases |

| Grameen-Intel |

Healthcare access gaps |

ICT-enabled rural health consultations |

SDG 3 (Good Health), SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation) |

Increased consultations; early disease detection |

| Grameen-Adidas |

Parasitic diseases from barefoot walking |

Low-cost footwear production and distribution |

SDG 3 (Good Health) |

Lower incidence of soil-transmitted diseases |

| Grameen Shakti |

Lack of electricity in rural areas |

Solar home systems for off-grid households |

SDG 7 (Clean Energy), SDG 13 (Climate Action) |

Increased clean energy access; reduced CO₂ emissions |

| Grameen Bank |

Poverty and lack of credit access |

Collateral-free microfinance for the poor |

SDG 1 (No Poverty), SDG 5 (Gender Equality) |

Higher household income; women’s empowerment |

| Grameen Eye Care Hospitals |

Preventable blindness |

Low-cost, high-quality eye health services with cross-subsidy |

SDG 3 (Good Health) |

Reduced blindness prevalence; improved vision health |

| Grameen Telecom |

Rural communication barriers |

Village Phone micro-entrepreneurship program |

SDG 8 (Decent Work), SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation) |

Expanded connectivity; increased rural entrepreneurship |

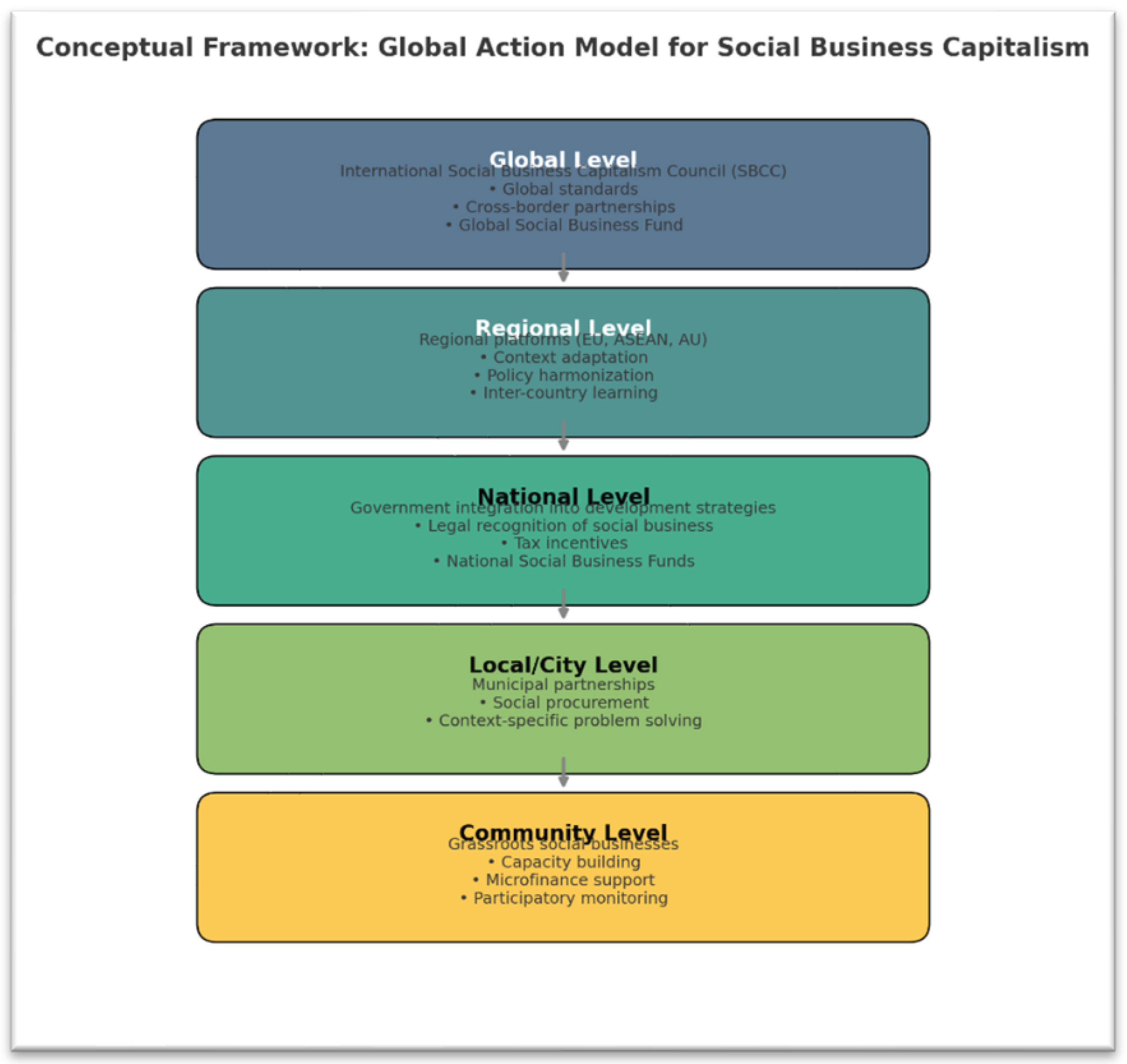

5. Proposing a Global Action Model for Social Business Capitalism

I am going to propose a Social Business Global Action Model (SOB-GAM) which will be a multi-tiered framework designed to integrate social business capitalism into global, regional, national, and local economic systems. It is premised on the understanding that systemic transformation requires both top-down policy alignment and bottom-up innovation. The GAM aims to operationalize Capitalism II by embedding market-based, non-dividend social enterprises into socio-economic planning and SDG implementation strategies.

This framework responds to two pressing challenges:

- (a)

The structural limitations of Capitalism I in addressing social and environmental externalities (Hasnat et al., 2025; Molla et al., 2014).

- (b)

The need for scalable models that translate field-level social business innovations into policy-supported, globally networked solutions (Yunus, 2007, 2010).

5.1. Structural Levels of the Model

5.1.1. Global Level

At the highest tier, an ‘international organization (IO)’ would coordinate global strategies, maintain a knowledge hub, and manage a Global Social Business Fund. This body could be formed as a specialized UN body with a global mandate. For now, we may call it UN Social Business Capitalism Council (UN-SBCC), which will be autonomous but linked to UN agencies (e.g., UNDP, UNIDO) to ensure SDG alignment and facilitate cross-border partnerships. Activities would include:

Setting global standards for social business performance metrics.

Facilitating South–South and North–South collaboration.

Mobilizing blended finance instruments (public, private, and philanthropic capital).

5.1.2. Regional/Continental Level

There would be a regional hub center for this UNSBCC to oversee, coordinate, and consolidate regional and national level initiatives. In parallel, Regional platforms (e.g., EU, ASEAN, African Union, SAARC) would adapt global principles to their socio-economic contexts, developing policy toolkits and fostering inter-country learning. Emphasis would be placed on harmonizing legal frameworks for social enterprises and enabling trade in socially impactful goods and services.

5.1.3. National Level

In line with the above, the regional hubs, there would be national hub offices or centers to oversee, coordinate, and consolidate national and local level initiatives. In parallel, National governments would integrate social business policies into economic development strategies, incentivizing capital allocation toward non-dividend enterprises through tax benefits, procurement preferences, and concessional financing. National Social Business Funds could be co-managed by public agencies and private sector representatives to ensure both efficiency and accountability.

5.1.4. Local – City and Community Level

Coming from the national level, the local city and community level, there would be national hub offices or centers to oversee, coordinate, and consolidate national and local level initiatives. In parallel, Municipal City and other local level authorities would partner with local social businesses to address context-specific challenges—such as waste management, urban poverty, and localized renewable energy solutions—while embedding social procurement into municipal budgets.

At the grassroots, social businesses would emerge from locally identified needs, supported by capacity-building programs and microfinance schemes. Community-level governance would ensure accountability, while participatory monitoring mechanisms would measure both social and environmental impact.

Figure 2.

Layers of SB GAM.

Figure 2.

Layers of SB GAM.

6. Discussion

6.1. SDG integrated Diffusion Model

The GAM draws on diffusion of innovations theory (Rogers, 2003), positing that successful adoption of social business models requires a phased approach:

Innovators: Social entrepreneurs piloting solutions in niche contexts.

Early adopters: Communities and policymakers championing replication.

Early majority: Broader institutional and investor engagement.

Late majority and laggards: Scaling to mainstream economic systems.

The model also incorporates systems thinking, recognizing that multi-level governance, financial flows, and cultural norms interact to shape adoption rates (Santos, 2012).

6.1.1. SDG Integration

Social business capitalism is uniquely positioned to operationalize the SDGs at scale. The GAM aligns with multiple SDGs:

SDG 1: Poverty eradication through inclusive economic participation.

SDG 3: Health improvements via social health enterprises.

SDG 7: Affordable, clean energy through renewable energy businesses.

SDG 8: Decent work and economic growth in underserved areas.

SDG 10: Reduced inequalities through accessible goods and services.

SDG 17: Strengthened global partnerships for sustainable development.

By embedding social business within SDG frameworks, the GAM ensures that impact is both measurable and globally comparable, addressing the current gap between high-level sustainability goals and on-the-ground enterprise models.

6.2. Financing Mechanisms

The model proposes a blended finance approach—combining concessional loans, equity-like grants, and results-based financing. This structure reduces risk for early-stage social businesses while attracting impact investors seeking measurable returns in social and environmental outcomes (Andreoli, 2022). Every country will give a subscription. Then it will operate as a social business itself. That means it will take advantage of Public Private Partnership (PPP) model. The Global and national hub will invest in social business centers and businesses. Every local level social business hub will give subscription from the revenue generation of their businesses.

6.3. Policy Implications

The Global Action Model (GAM) offers a structured pathway for embedding social business into multi-level governance systems. At the global level, aligning the GAM with the UN’s SDG monitoring frameworks could enable social businesses to access international climate finance, development assistance, and cross-border partnerships (Hasnat et al., 2025). For national governments, adopting pro-social business legislation—such as legal recognition of non-dividend enterprises and tax incentives—would institutionalize Yunus’s vision within national development strategies (Yunus, 2010, 2017).

Furthermore, public procurement reform could prioritize contracts for social businesses, ensuring that government spending directly contributes to social and environmental objectives (Santos, 2012). For example, Grameen Shakti’s solar home systems could be integrated into national rural electrification programs, creating synergies between policy and enterprise-level action.

6.4. Scalability Challenges

While Yunus’s case studies demonstrate local success, scaling social business models faces multiple barriers:

Capital Constraints: The non-dividend nature of social business may deter traditional investors seeking financial returns (Andreoli, 2022).

Regulatory Gaps: Many jurisdictions lack legal definitions or frameworks for social business, creating uncertainty for entrepreneurs and investors (Molla et al., 2014).

Cultural Factors: The success of social business models often depends on community trust, which may not easily transfer across cultural contexts (Qudrat-I Elahi & Rahman, 2006).

To address these barriers, the GAM’s financing mechanism—blended finance with performance-based incentives—can bridge the gap between impact philanthropy and market investment.

6.5. Diffusion and Institutionalization

Drawing on Rogers’ (2003) diffusion of innovations framework, the GAM’s success depends on moving beyond early adopters to engage the early majority through institutional buy-in. This requires:

Demonstration Effects: Publishing rigorous impact evaluations of flagship projects.

Policy Coherence: Harmonizing social business policies with broader development and sustainability strategies.

Cross-Sector Partnerships: Leveraging corporate social responsibility (CSR) channels to incubate and co-finance social business ventures (Hasnat et al., 2025).

6.6. Future Research Directions

There is a need for longitudinal studies tracking the performance of social businesses over time, especially in measuring non-financial impacts such as health outcomes, educational attainment, and environmental quality. Comparative studies between different regions implementing the GAM could identify context-specific success factors and potential pitfalls. Additionally, more research is needed on impact measurement methodologies that balance academic rigor with operational feasibility in low-resource settings.

7. Conclusions

The evolution from Adam Smith’s moral capitalism to Mohammad Yunus’s social business capitalism represents more than an incremental reform—it is a paradigmatic shift in economic thought and practice. Capitalism I, while effective in driving efficiency and wealth creation, has produced systemic inequalities, environmental degradation, and social exclusion. Capitalism II, as articulated through Yunus’s social business model, reframes the purpose of enterprise toward sustained social impact without abandoning market efficiency.

The Global Action Model proposed in this article offers a multi-level framework—spanning global, regional, national, local, and community tiers—that integrates social business into sustainable development strategies. By embedding SDG alignment, adopting blended finance structures, and leveraging diffusion of innovation principles, the GAM provides a viable roadmap for scaling social business capitalism.

Yet, implementation will require supportive legal frameworks, innovative financing mechanisms, and cross-sector partnerships. The examples discussed—from Grameen-Danone’s fortified yogurt to Grameen Shakti’s solar home systems—demonstrate that socially motivated enterprises can be financially viable, scalable, and impactful. The challenge ahead lies in institutionalizing such models across contexts while preserving their commitment to social purpose over profit maximization.

This paradigm shift demands both visionary leadership and empirical rigor, ensuring that the ideals of Capitalism II are realized not only in theory but also in measurable, transformative outcomes for people and the planet.

References

- Andreoli, E. (2022). Bridging the gap: Ethical finance and microcredit through Bangladesh and India from 1928 to today [Master’s thesis, University of Padua]. University of Padua Digital Library. https://thesis.unipd.it/handle/20.500.12608/70362.

- Elahi, K. Q.; Islam, M. Z. Microfinance: Social entrepreneurship and social consciousness-driven capitalism? Bangladesh Journal of Agricultural Economics 2003, 26, 79–102. Available online: https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/200707.

- Farooq, M. O.; Ahmad, A. U. F. Conscious capitalism and Islam: Convergence and divergence. In The spirit of conscious capitalism: Contributions of Islamic thought; Springer, 2022; pp. 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasnat, M. A.; Khandakar, H.; Rahman, M. A. Capitalism in modern ignorance (jahilliyah): Exploring Islamic alternatives to reshape human behaviour and provide solutions for the 21st century. International Journal of Ethics and Systems 2025, 41, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huda, M. M. (2024). The role of social business on social transformation: Evidences from Bangladesh (Doctoral dissertation). University of Dhaka Repository. http://reposit.library.du.ac.bd:8080/xmlui/handle/123456789/3167.

- Kuhn, T. S. The structure of scientific revolutions; University of Chicago Press, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Molla, R. I., Alam, M. M., Bhuiyan, A. B., & Alam, F. (2014). Social and Islamic entrepreneurships for social justice: A structural framework for social enterprise economics. Universiti Utara Malaysia Institutional Repository. https://repo.uum.edu.my/id/eprint/15708.

- Qudrat-I Elahi, K.; Rahman, M. L. Micro-credit and micro-finance: Functional and conceptual differences. Development in Practice 2006, 16, 476–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E. M. Diffusion of innovations, 5th ed.; Free Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, F. M. A positive theory of social entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Ethics 2012, 111, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. (2002). The theory of moral sentiments (K. Haakonssen, Ed.). Cambridge University Press. (Original work published 1759).

- Smith, A. (1776). An inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations. W. Strahan and T. Cadell.

- Yunus, M. (2007). Creating a world without poverty: Social business and the future of capitalism. PublicAffairs.

- Yunus, M. (2010). Building social business: The new kind of capitalism that serves humanity’s most pressing needs. PublicAffairs.

- Yunus, M. (2017). A world of three zeros: The new economics of zero poverty, zero unemployment, and zero net carbon emissions. PublicAffairs.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).