1. Introduction

In fields such as wearable health monitoring [

1,

2], electronic skin [

3,

4], and robotic sensing [

5,

6,

7], there is an urgent need for high-precision, real-time temperature sensing that can conform closely to the human body or complex curved surfaces [

8,

9,

10]. Applications include monitoring surface body temperature distribution, human-machine interaction thermal feedback, and battery thermal safety management [

11]. Among mainstream flexible solutions, metal thin films (such as Pt, Ni) directly fabricated on flexible substrates can achieve relatively high sensing accuracy but suffer from low process maturity and high cost [

12]. Carbon-based materials (such as graphene, carbon nanotubes) or organic semiconductors [

13] directly built on flexible substrates offer advantages of good flexibility and stretchability but face challenges in maintaining linearity and long-term stability over a wide temperature range [

14,

15]. Hybrid integration of chips using flexible printed circuit boards (FPC) enables the direct use of mature CMOS integrated circuits while ensuring curved conformability of flexible sensing units [

16,

17].

Integrated circuit temperature sensing technology mainly relies on the temperature characteristics of silicon semiconductor PN junctions [

18]. It uses the negative correlation between the base-emitter voltage (V

BE) of bipolar transistors and temperature [

19]. A bandgap reference circuit weights and sums V

BE with a positive temperature coefficient voltage to generate a near-zero temperature drift reference voltage, which is then converted into a voltage output proportional to absolute temperature (PTAT). This method depends on the device layout matching of CMOS processes, but the core circuits are highly sensitive to stress interference, temperature drift, and electrostatic discharge [

20].

2. Design and Fabrication

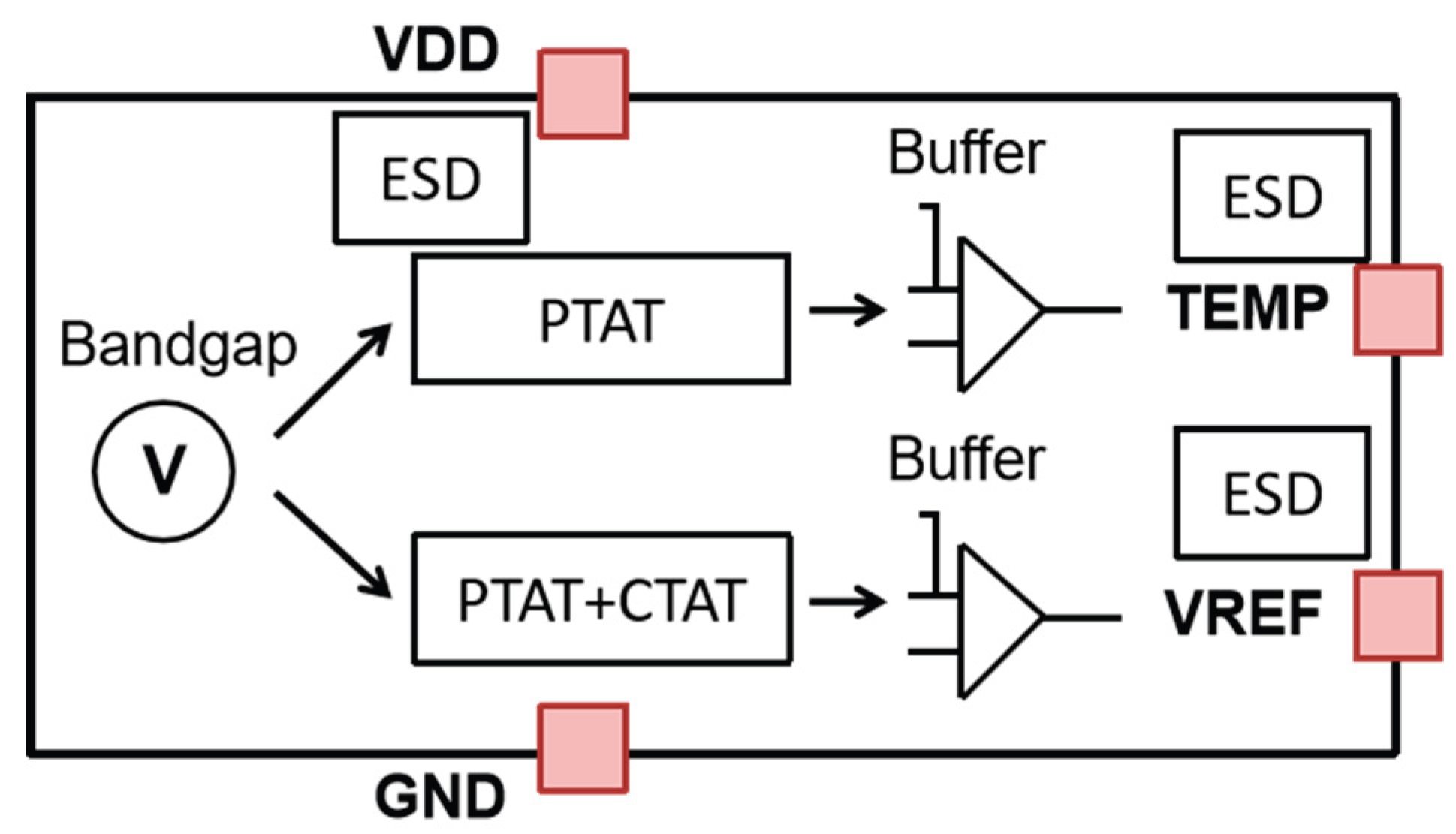

As shown in

Figure 1, the die generates a zero-temperature-drift reference voltage with a bandgap reference circuit as the core. Internally, a bipolar transistor’s ΔVBE drives the PTAT circuit to produce a positive temperature coefficient current, which is then proportionally combined with a CTAT (negative temperature coefficient) current in the zero-temperature-drift synthesis circuit to output a nearly zero-temperature-drift reference voltage signal. This signal is buffered through a buffer circuit and output from the VREF pin, ensuring strong load interference immunity. The PTAT circuit of the bandgap reference is directly buffered by a buffer circuit and output from the TEMP pin, providing a highly linear temperature sensing voltage signal. A dual-path ESD protection network covers all pins; a clamp structure is used between VDD and GND, and a secondary discharge path is added at the TEMP and VREF pins, forming full-domain electrostatic protection. The four pins have clear functions: VDD for power supply (4.5–5.5 V), GND for ground, TEMP outputs the temperature voltage, and VREF provides the reference voltage, achieving integrated sensing, referencing, and protection.

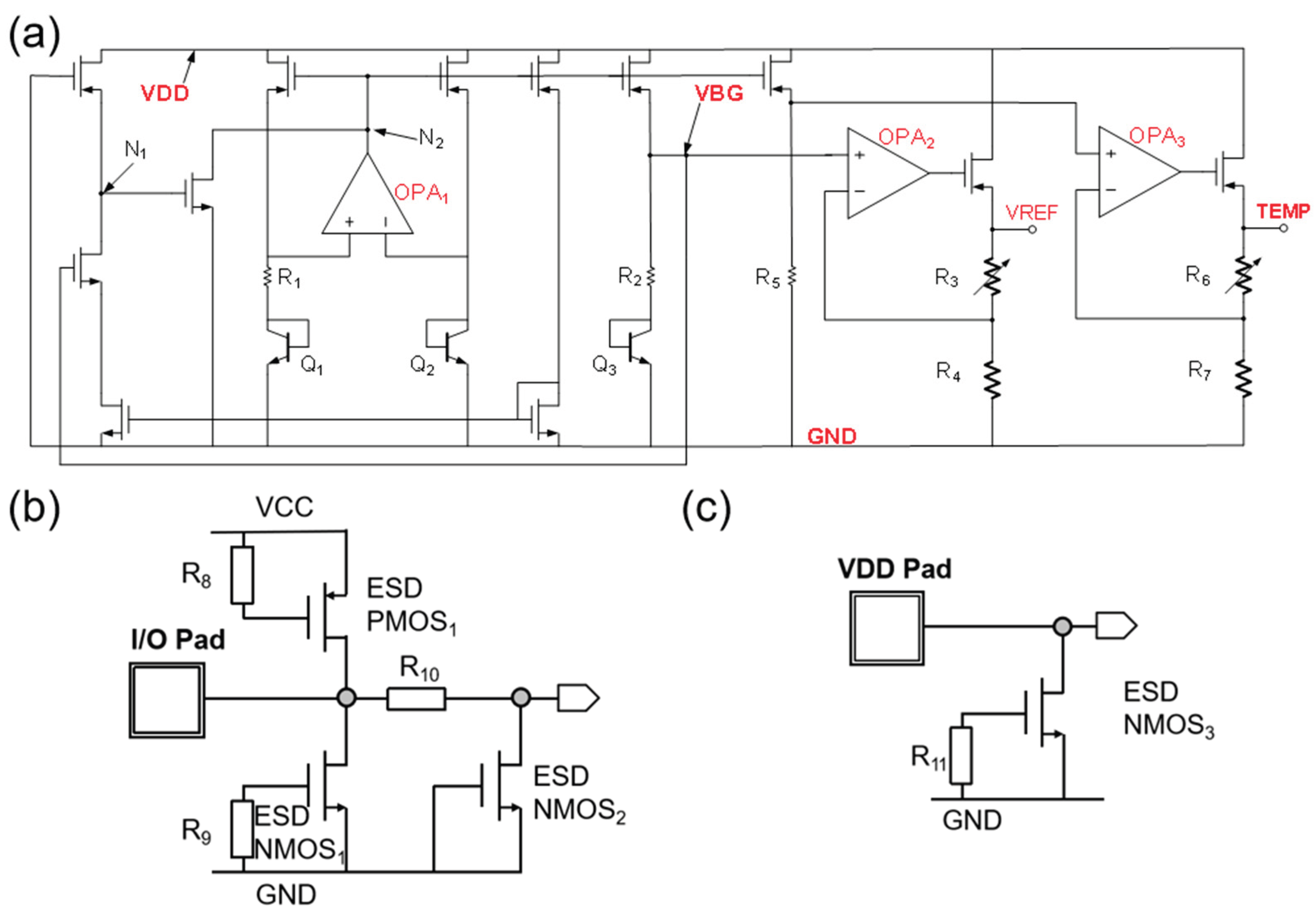

The circuit schematic of the sensing die is shown in

Figure 2(a). From left to right, it sequentially integrates a soft-start circuit (to suppress power surge impact), a bandgap reference core, a V

BG circuit combining PTAT/CTAT currents, and a buffer amplifier circuit (implementing voltage proportional amplification through a resistor feedback network, respectively driving the reference output VREF and the temperature signal TEMP).

To raise the bias voltage and achieve layout matching, the parallel count ratio of Q

1 to Q

2 is selected as 16:2. The voltage division on resistor R

1 in the bandgap reference core is expressed as follows [

21]:

where

represents the voltage difference between the base and emitter of the transistors. According to the current mirror current replication relationship, the following holds in the PTAT/CTAT fusion circuit [

22]:

where I_PTAT is the PTAT current generated by the bandgap reference core, copied to branch Q

3 through a current mirror, forming a PTAT voltage across resistor R

2. The transistor Q

3 provides the CTAT voltage. By adjusting the ratio between R

1 and R

2, the first-order temperature coefficient of V

BG can be corrected. The output reference voltage is given by [

23]:

The resistor ratio circuit constructed by OPA

2 enables the VREF pin to have both strong driving capability and high input impedance, without affecting the voltage value of the V

BG circuit. The temperature sensing pin is expressed as [

24]:

where I_PTAT is the PTAT current generated by the bandgap reference core and copied via a current mirror to the R

5 branch, forming a PTAT voltage across resistor R

5. Additionally, because the resistor ratio circuit is constructed by OPA

3, the TEMP pin possesses both large driving capability and high input impedance.

Figure 2(b) illustrates the ESD protection paths for the I/O pins such as VREF and TEMP, adopting a PMOS-NMOS bidirectional discharge structure (PMOS discharges towards the power supply, NMOS discharges towards ground), with a secondary NMOS discharge plus current-limiting resistor introduced to enhance transient response robustness.

Figure 2(c) shows the ESD protection path for the power pins; VDD is directly connected to a large-size NMOS discharge transistor to ground, with a gate-integrated current-limiting resistor to prevent false triggering. This architecture ensures an ESD protection capability exceeding 4 kV HBM from the circuit design perspective.

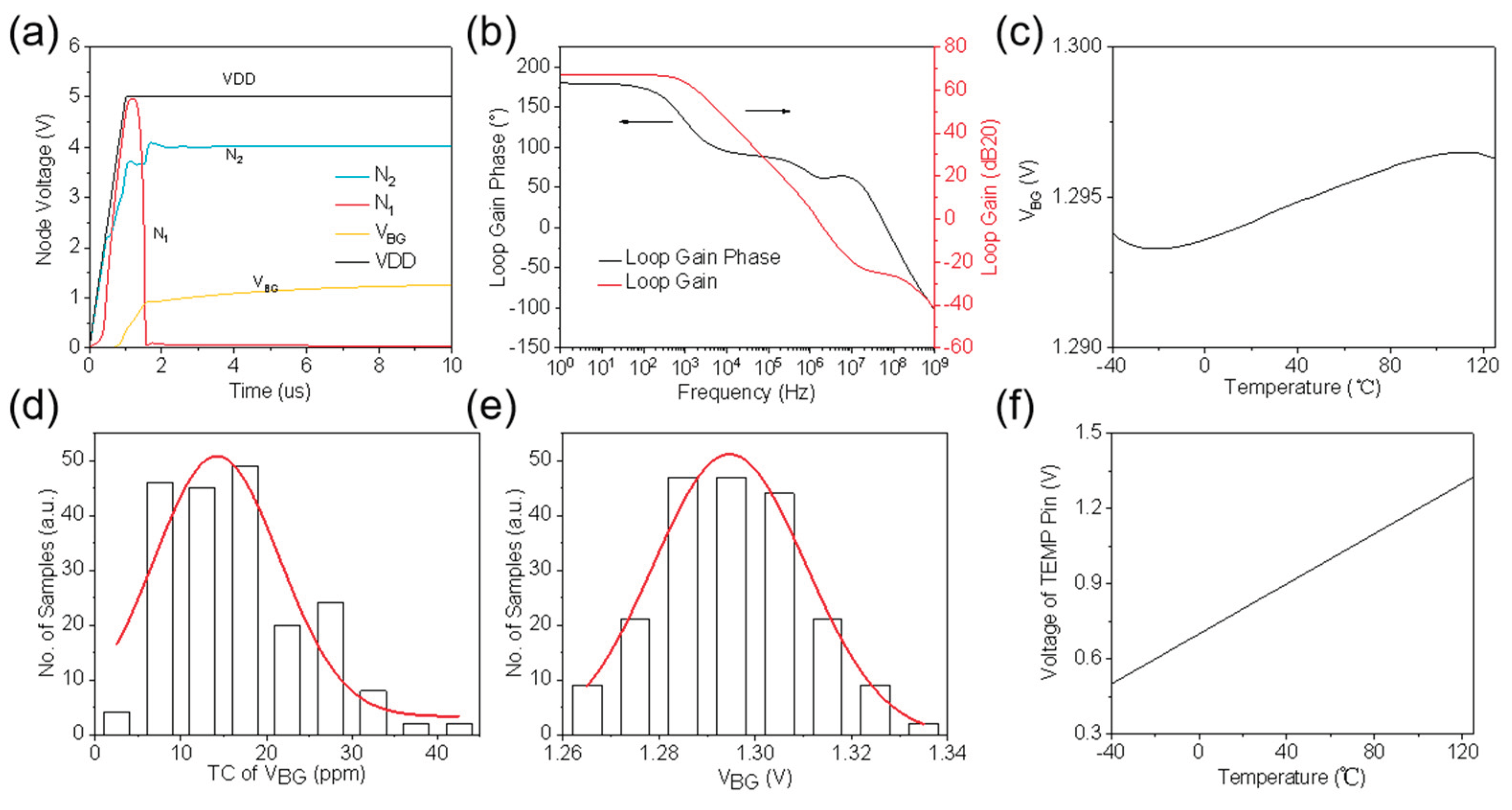

Circuit simulation verification based on the commercial 180nm CMOS process PDK shows that under a 5 V/μs power supply slew rate,

Figure 3(a) confirms the bandgap reference core powers up normally with an overshoot of less than 5%. Loop stability analysis in

Figure 3(b) sets the phase margin above 55°, ensuring no risk of oscillation.

Figure 3(c) shows the typical temperature drift of the reference voltage is 20 ppm/°C over the range of -40 to 125°C. PVT and Monte Carlo simulations (

Figure 3d,e) indicate the worst-case temperature drift is ≤ 45 ppm/°C, and the reference voltage deviation is less than 8 mV (3σ).

Figure 3(f) further verifies the temperature sensing voltage linearity over the full temperature range, with the reference output voltage at 25°C being 0.83 V and sensitivity stable at 5 mV/°C. These simulation results provide critical parameter boundaries for system redundancy design, supporting layout optimization during chip fabrication to achieve both temperature drift suppression and enhanced robustness.

Figure 3.

Simulation analysis of the schematic based on the foundry PDK. (a) Transient timing simulation of the startup circuit; (b) Stability simulation of the bandgap reference core loop; (c) Relationship between bandgap reference voltage and temperature; (d) Distribution of the temperature coefficient of the bandgap reference voltage based on Monte Carlo simulation; (e) Distribution of the bandgap reference voltage based on Monte Carlo simulation; (f) Relationship between the output voltage at the temperature output pin and temperature.

Figure 3.

Simulation analysis of the schematic based on the foundry PDK. (a) Transient timing simulation of the startup circuit; (b) Stability simulation of the bandgap reference core loop; (c) Relationship between bandgap reference voltage and temperature; (d) Distribution of the temperature coefficient of the bandgap reference voltage based on Monte Carlo simulation; (e) Distribution of the bandgap reference voltage based on Monte Carlo simulation; (f) Relationship between the output voltage at the temperature output pin and temperature.

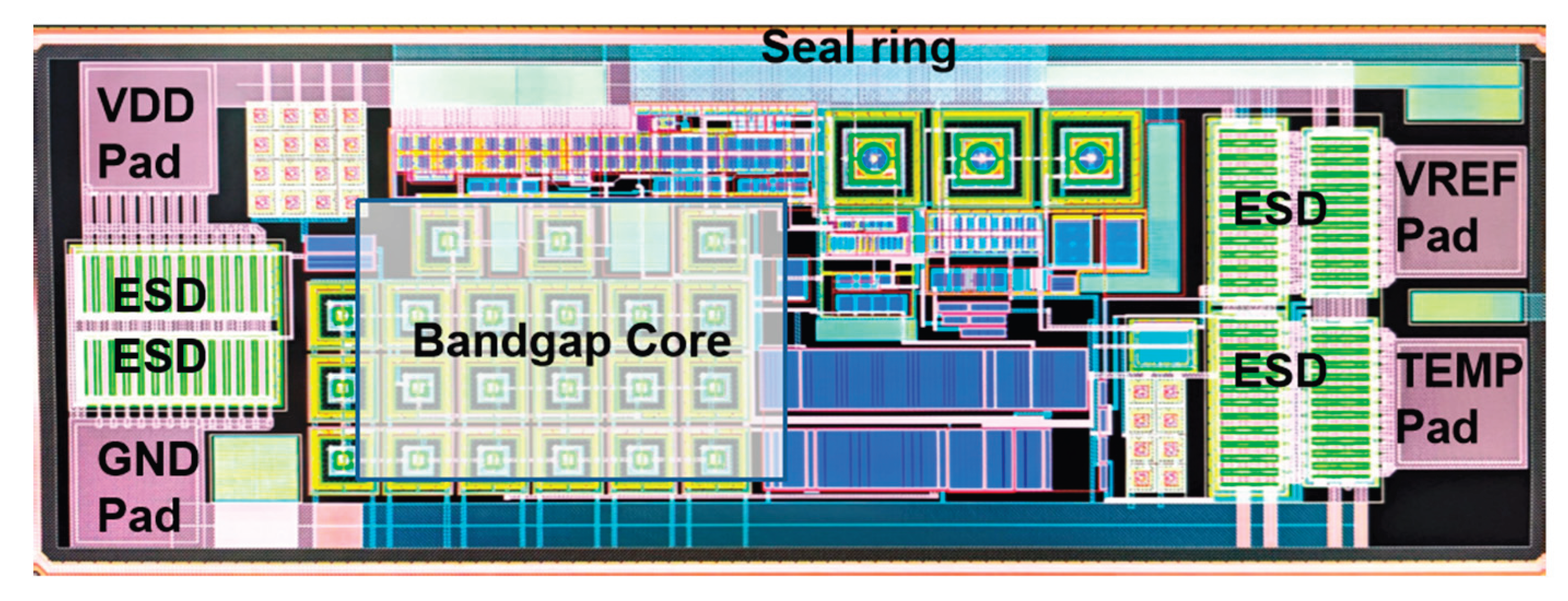

Figure 4.

Layout drawing based on the foundry PDK.

Figure 4.

Layout drawing based on the foundry PDK.

The layout strictly follows the 180 nm CMOS process design rules. The core area includes the bandgap reference source (occupying 0.08 mm², using common-centroid matched layout to suppress gradient errors), a dual-path ESD protection network (with large-size clamp transistors integrated at the VDD/GND pins, accounting for 22% of the area), and four aluminum-copper alloy pins (VDD/GND/TEMP/VREF, each with a width of 80 μm). The periphery is equipped with a double-layer seal ring structure (20 μm wide, deeply grounded region ring) to provide mechanical stress buffering. Key signal routing employs shielding protection (temperature sensing lines with 3 μm width and 2 μm spacing), and the reference voltage path is routed as differential symmetrical lines to reduce crosstalk. The entire layout has passed DRC/LVS verification with zero errors.

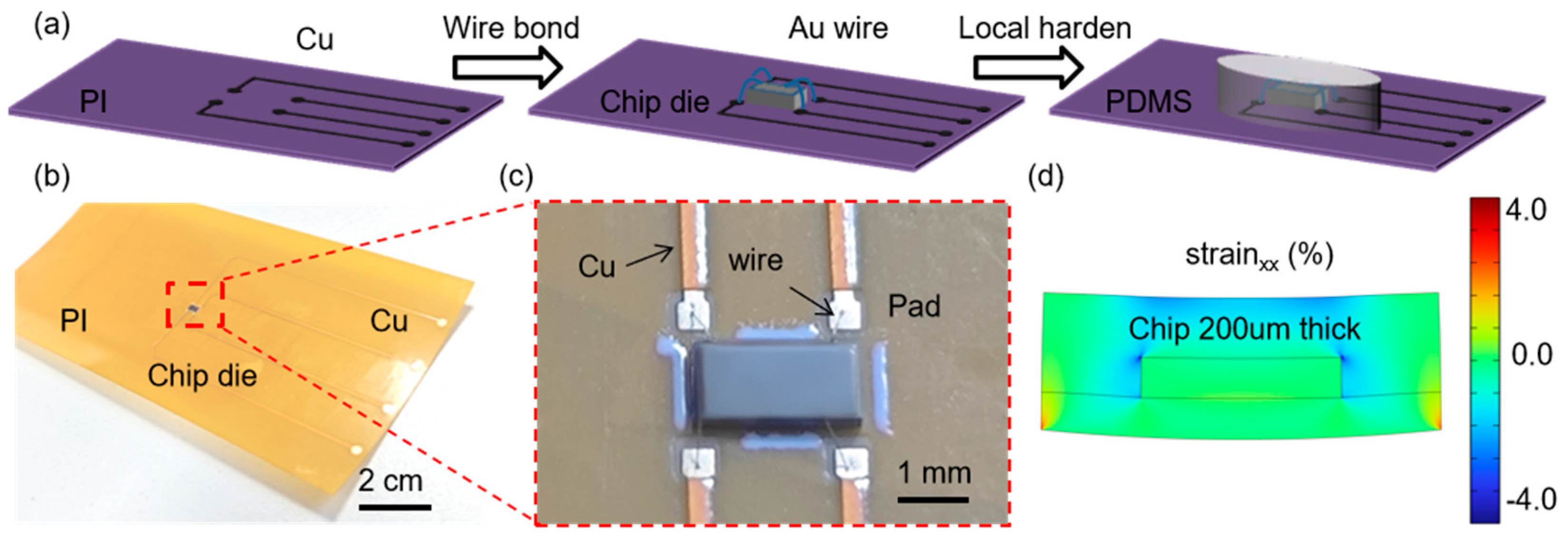

The fabrication process [

25] of the flexible hybrid-integrated temperature sensor is shown in

Figure 5(a). Based on a standardized process (FPC → die conductive epoxy mounting → gold wire bonding → PDMS encapsulation), high-precision integration of a 1.2 × 0.6 mm² CMOS sensing bare die with a flexible printed circuit board is achieved. A photograph of the flexible sensor is shown in

Figure 5(b), and close-up photos of the gold wire bonding and encapsulation are shown in

Figure 5(c). To minimize strain on the die during bending of the flexible device, the back of the die is polished to a thickness of 200 μm before assembly. As a result, the overall thickness of the flexible sensor is only 0.3 mm. Through finite element simulation modeling and analysis, at a bending radius of 10 mm, the maximum strain in the xx direction in the die area is less than 0.5%, and the strain at the bonding points in the xx direction is less than 3% (below the failure threshold), ensuring mechanical reliability of the bare die under dynamic deformation. The entire fabrication process relies on a mature fabless model, ensuring design reproducibility and mass production capability.

3. Results and Discussion

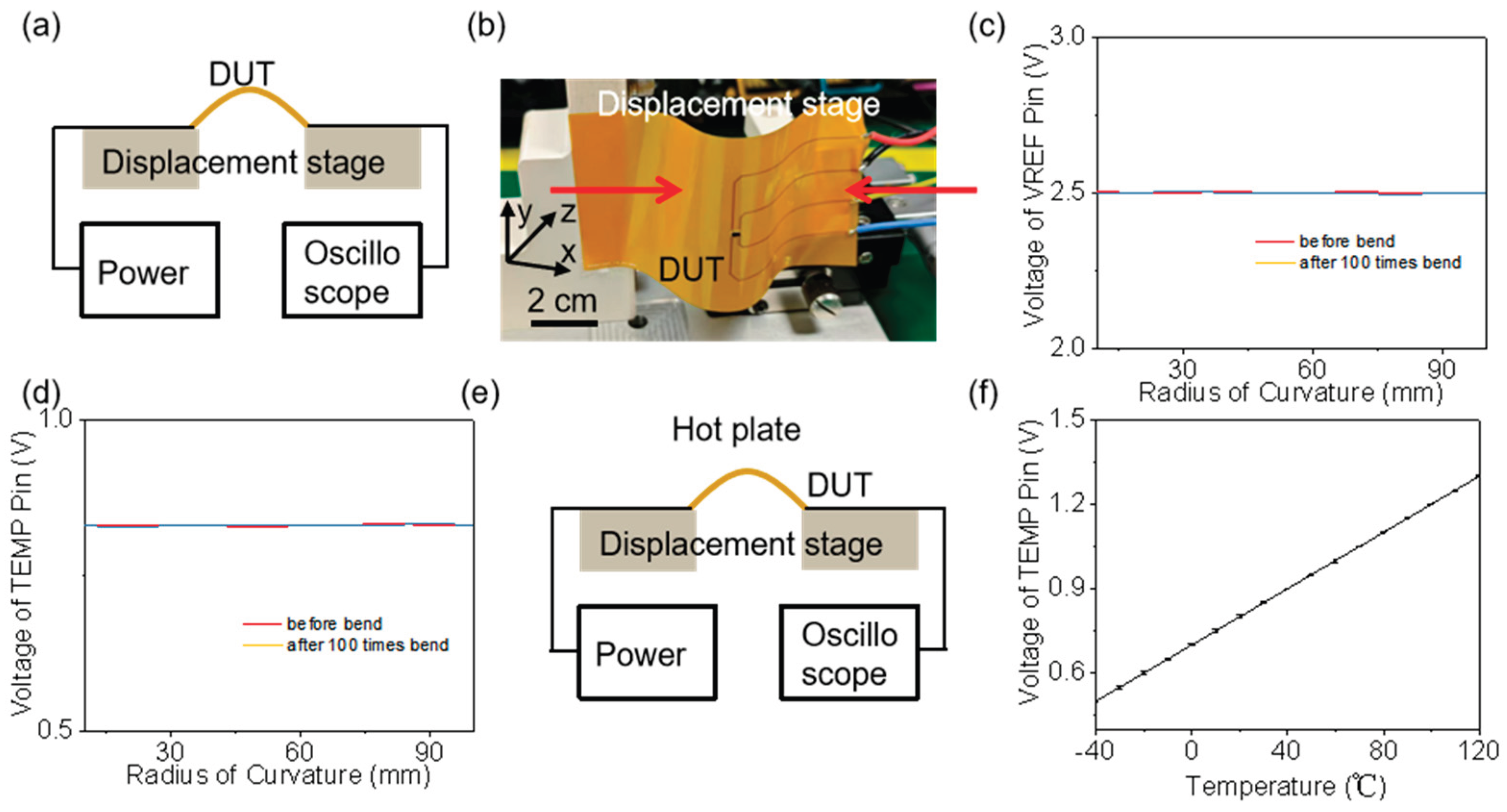

The testing setup is shown in

Figure 6(a,b). A digital power supply provides adjustable voltage signals (1.8 V / 2.5 V / 3.3 V / 5 V), with the flexible device’s pins connected to the sensing die. An oscilloscope captures the output voltage’s time-domain signal, and a multimeter monitors the static voltage, enabling verification of electrical characteristics. Both ends of the flexible device are mounted on a bidirectional displacement platform; displacement along the x-axis causes bending of the flexible device. A microscope is positioned along the y-axis to capture the device’s contour and determine the bending radius at the sensing die location.

The relationship between reference voltage output, temperature pin voltage output, and bending radius before bending and after 100 bending cycles of the flexible hybrid-integrated temperature sensor is shown in

Figure 6(c,d). It can be observed that at bending radii above 10 mm, the slight strain endured by the die does not alter the electrical performance of the reference and temperature outputs, indicating the flexible device has strong mechanical stability.

Figure 6(e) is a schematic of the experimental setup for testing the temperature drift characteristics of the flexible device. A hot plate is used to change the temperature at the die’s location; after stabilizing for 20 minutes, the temperature pin voltage output is recorded. The results, shown in

Figure 6(f), indicate an output voltage of 0.825 V at 25°C, with sensitivity stable at 5.0 mV/°C and linearity of 0.99%. This demonstrates that the temperature sensor has an output offset of less than ±0.5°C and a full-temperature-range testing accuracy error stable within ±1°C. Additionally, five samples underwent ESD testing (HBM, CDM, MM); all pins withstood electrostatic discharge stresses of HBM/4 kV, CDM/500 V, and MM/200 V.