Submitted:

06 August 2025

Posted:

15 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Framing

2.1. Sustainable Rural Livelihood Framework

2.2. Multidimensional Poverty and Composite Indices

2.3. Spatial and Dynamic Dimensions of Poverty

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Data Sources

3.3. Composite Index Construction

3.3.1. Indicator Selection

- 1.

- Number of high school institutions:

- 5 = Worst condition (0.00–0.80)

- ...

- 1 = Optimal condition (3.20–4.00)

- 2.

- Source of drinking water:

- 1 = Branded bottled water

- ...

- 5 = River, rainwater, etc.

- 3.

- Access to a financial credit institution:

- 1 = presence

- 5 = absence

- 4.

- Distance to nearest higher education institution (km):

- 1 = Optimal condition (3.00–22.38)

- ...

- 5 = Worst condition (80.52–99.90)

3.3.2. Normalization

- is the raw class score (1 to 5),

- is the normalized value,

3.3.3. Weighting

3.3.4. Aggregation

- = composite index for unit (e.g., village)

- = normalized score of indicator or unit

- = final weight for indicator

4. Results

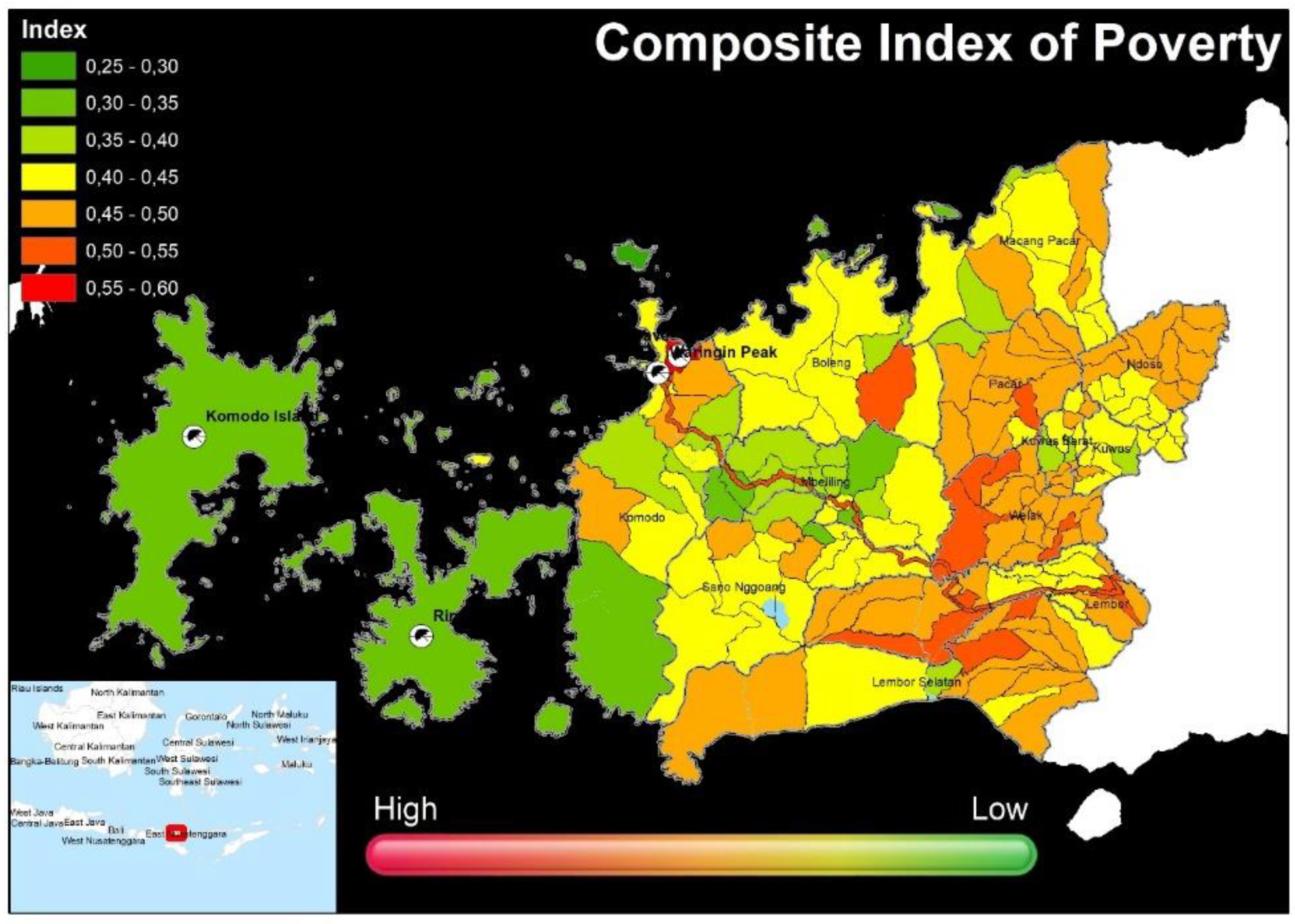

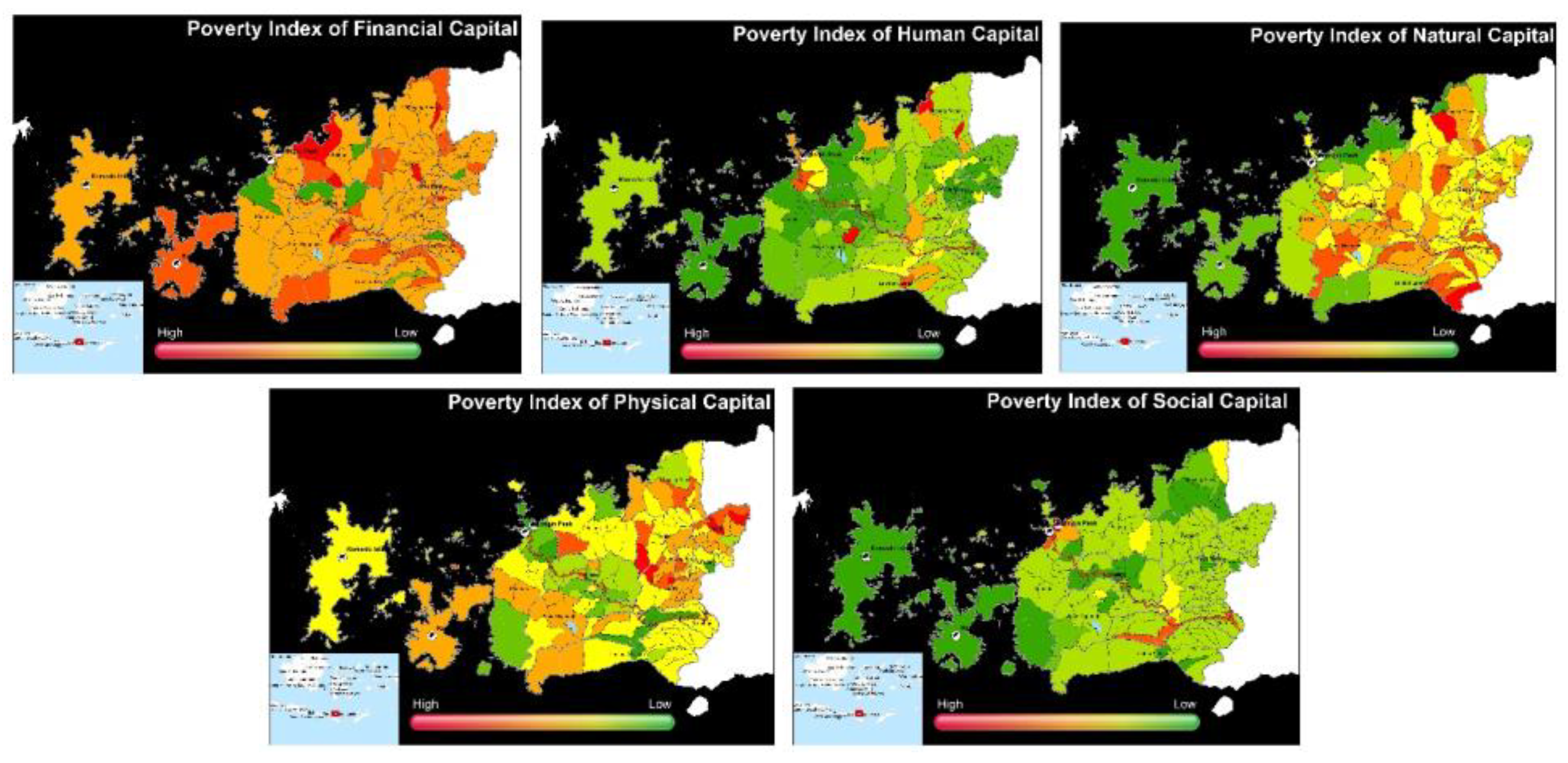

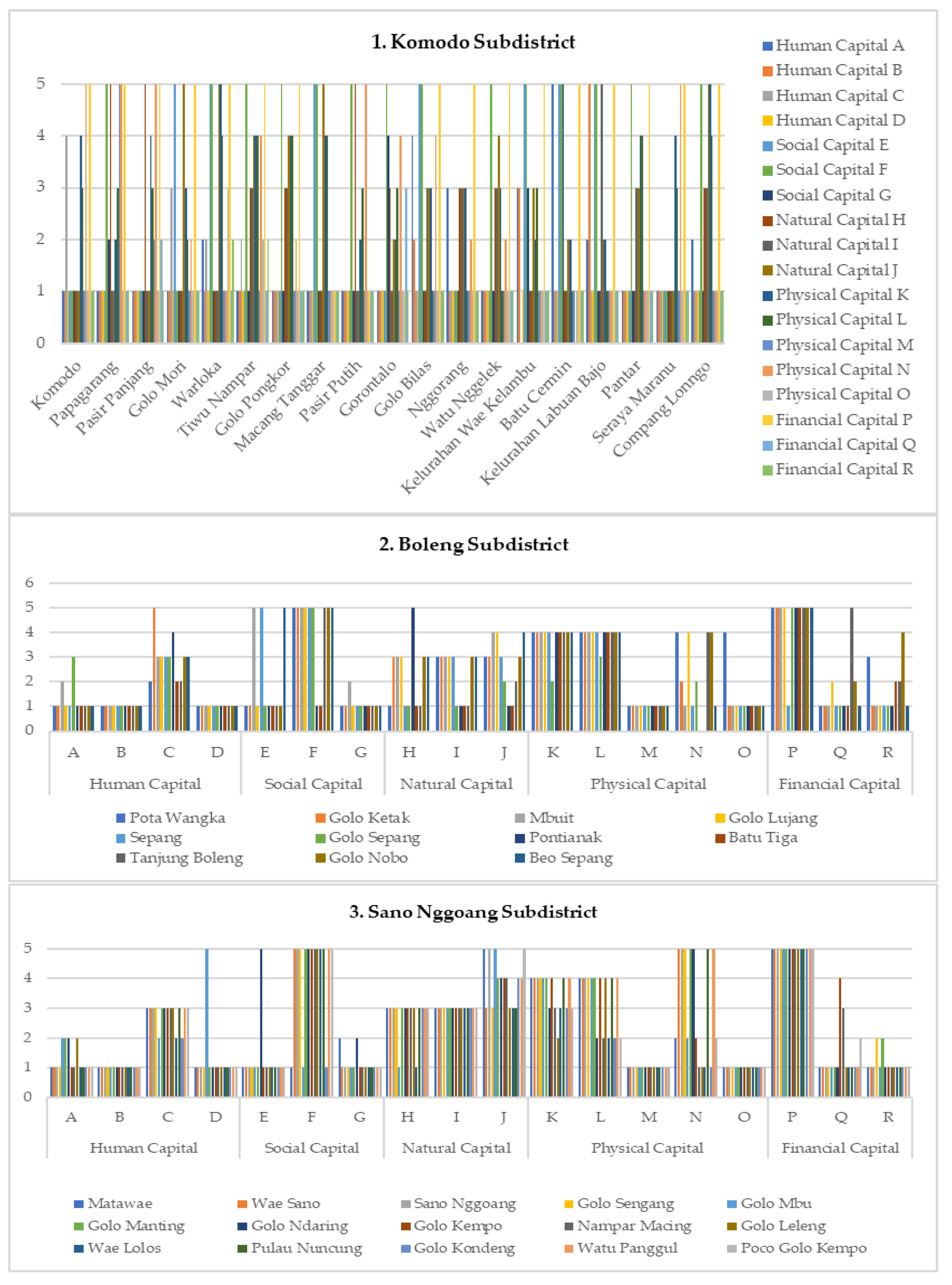

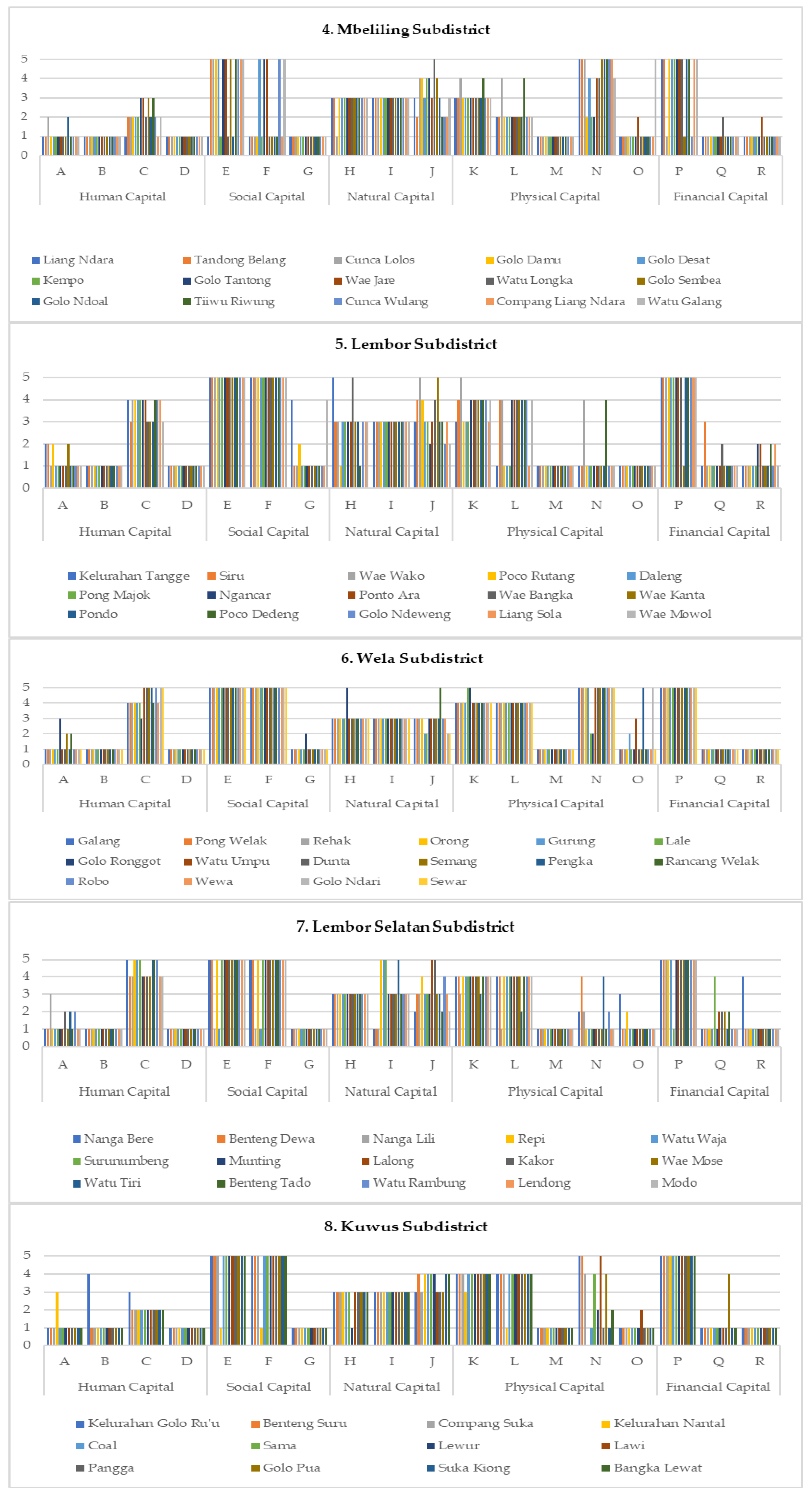

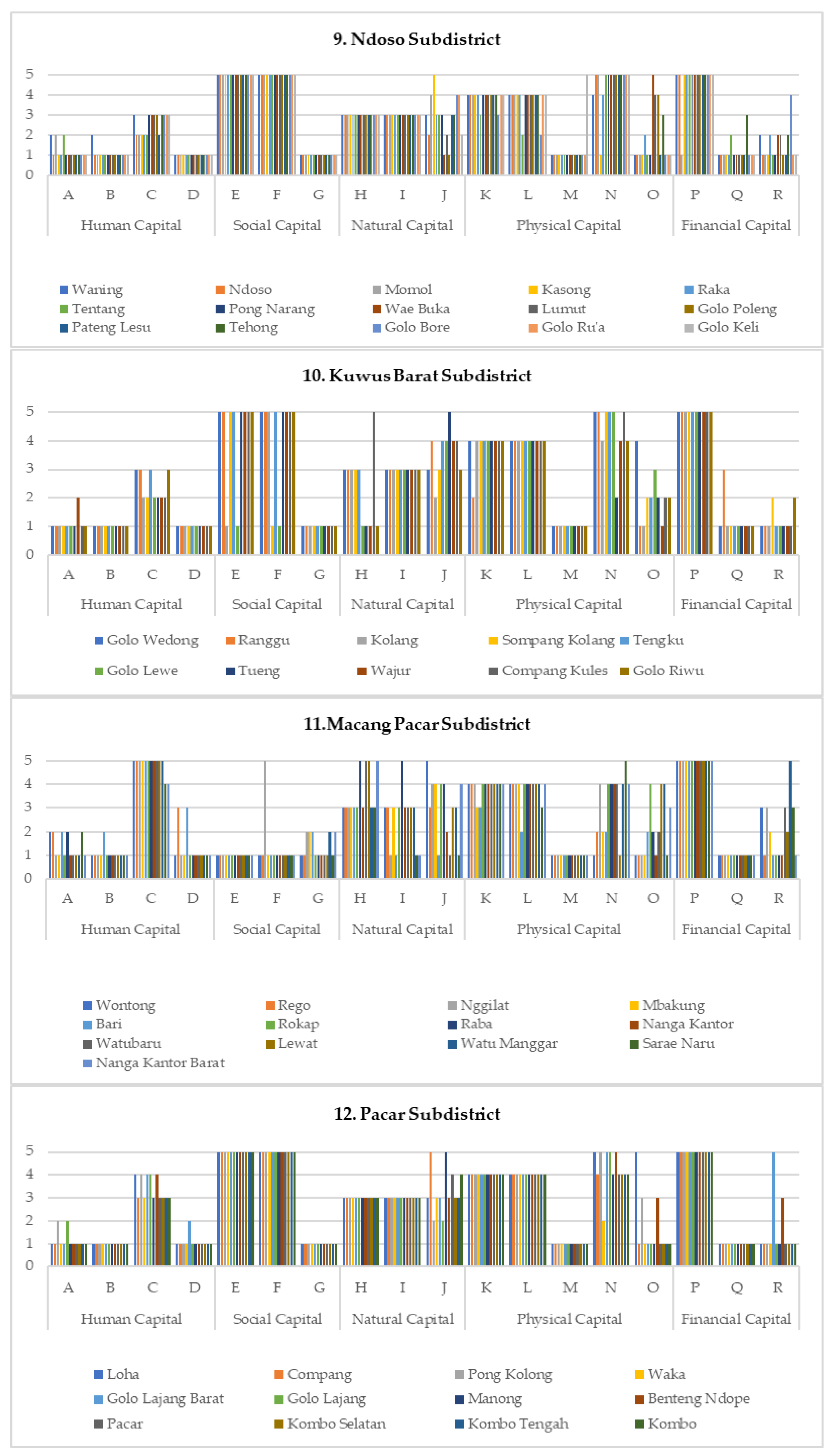

4.1. Spatial Disparities in Multidimensional Poverty

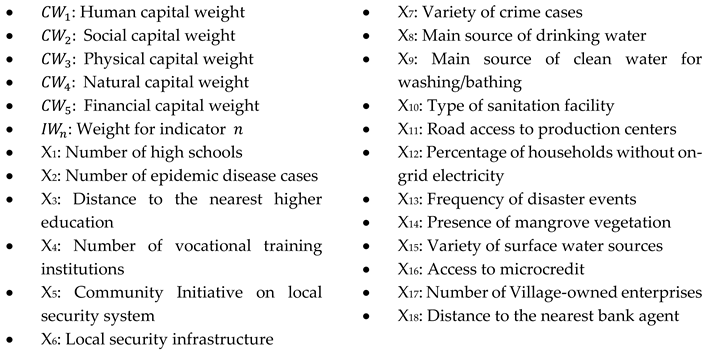

- Human Capital: Access to senior high schools (A), prevalence of communicable diseases (B), access to higher education (C), access to vocational training (D), and neighborhood safety initiatives (E).

- Social Capital: Neighborhood safety initiatives (E), maintenance of local security systems (F), and variations in crime rates (G).

- Natural Capital: Trends in disaster occurrences (H), presence of mangrove ecosystems (I), and access to surface water sources (J).

- Physical Capital: Access to drinking water (K), access to clean water (L), sanitation facilities (M), road infrastructure quality (N), and access to electricity (O).

- Financial Capital: Access to financial credit (P), presence of village-owned enterprises (BUMDes) (Q), and access to banking services (R).

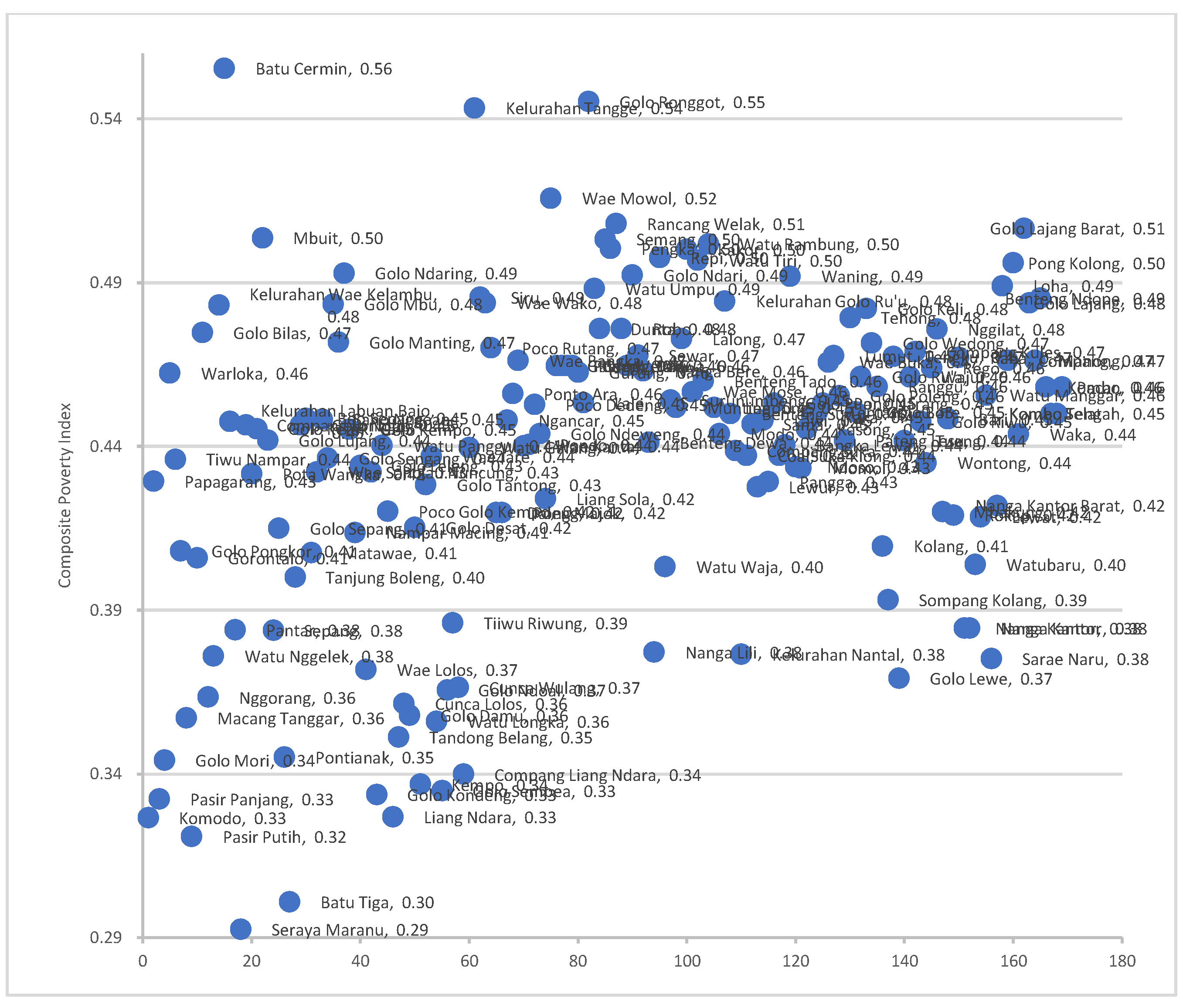

4.2. Composite Poverty Index Distribution

| Livelihood Capital | Capital Weight | Indicator | Indicator Weight | IW x CW |

| (CW) | (IW) | |||

| Human Capital | 0,371 | Number of senior high schools (SMA/MA/SMK) | 0,368 | 0,137 |

| Number of Epidemic Disease Cases | 0,14 | 0,052 | ||

| Distance to the nearest higher education institution | 0,153 | 0,057 | ||

| Number of Vocational training institutions | 0,339 | 0,126 | ||

| Social Capital | 0,239 | Activation of neighbourhood security system initiated by residents | 0,11 | 0,026 |

| Construction/maintenance of local security systems | 0,309 | 0,074 | ||

| Number of crime type variations | 0,581 | 0,139 | ||

| Natural Capital | 0,123 | Trend in the number of disaster events | 0,261 | 0,032 |

| Presence of mangrove vegetation | 0,411 | 0,051 | ||

| Number of surface water source types available | 0,328 | 0,04 | ||

| Physical Capital | 0,167 | Main drinking water source | 0,189 | 0,032 |

| Primary water source for bathing/washing | 0,257 | 0,043 | ||

| Predominant type of sanitation facility used | 0,276 | 0,046 | ||

| Road access from production areas to trade centers | 0,095 | 0,016 | ||

| Percentage of households not using electricity | 0,183 | 0,031 | ||

| Financial Capital | 0,1 | Availability of small business credit facilities (KUK) | 0,548 | 0,055 |

| Number of village-owned enterprises (BUMDes) | 0,241 | 0,024 | ||

| Distance to the nearest banking agent | 0,211 | 0,021 |

5. Discussion

5.1. Spatial Dimensions of Multidimensional Poverty in Rural Context

5.2. Construction and Interpretation of the Composite Poverty Index

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roblek V, Kejžar A. A comprehensive examination of indicators for evaluating poverty and social exclusion. Discov Glob Soc [Internet]. 2025;3(1). Available from. [CrossRef]

- Ayele AW, Ewinetu Y, Delesho A, Alemayehu Y, Edemealem H. Prevalence and associated factors of multidimensional poverty among rural households in East Gojjam zone, Northern Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2025;25(1). [CrossRef]

- World Bank Group. Poverty & Equity Brief [Internet]. World Bank Group. 2019. Available from: https://databankfiles.worldbank.org/public/ddpext_download/poverty/33EF03BB-9722-4AE2-ABC7-AA2972D68AFE/Global_POVEQ_IDN.pdf.

- BPS-Statistics of Manggarai Barat Regency. Manggarai Barat Regency in Figures [Internet]. Labuan Bajo; 2024. Available from: https://manggaraibaratkab.bps.go.id/id/publication/2024/02/28/b3f41d3b859a25216d016797/kabupaten-manggarai-barat-dalam-angka-2024.html.

- Gai A, Ernan R, Fauzi A, Barus B, Putra D. Poverty Reduction Through Adaptive Social Protection and Spatial Poverty Model in Labuan Bajo, Indonesia’s National Strategic Tourism Areas. Sustain. 2025;17(2):1–17. [CrossRef]

- Hickel, J. The true extent of global poverty and hunger: questioning the good news narrative of the Millennium Development Goals. Third World Q [Internet]. 2016 May 3;37(5):749–67. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Béné C, Newsham A, Davies M, Ulrichs M, Godfrey-Wood R. Resilience, poverty and development. J Int Dev. 2014;26(5):598–623.

- Scoones, I. Sustainable livelihoods and rural development. Practical Action Publishing Rugby; 2015.

- Morse, S. Having Faith in the Sustainable Livelihood Approach: A Review. Sustainability. 2025;17(539):1–27. [CrossRef]

- Amaliah Y, Husni AHAA, Ansar MC, Chowdhury K. The research landscape of rural sustainable livelihood: a scientometric analysis. Front Sustain. 2025;6(May). [CrossRef]

- Natarajan N, Newsham A, Rigg J, Suhardiman D. A sustainable livelihoods framework for the 21st century. World Dev. 2022;155:105898. [CrossRef]

- DFID, GS. Sustainable livelihoods guidance sheets, Section 2. Framework. 2000.

- Sen, A. Development as Freedom (1999). In: Roberts JT, Hite AB, Chorev N, editors. The Globalization and Development Reader: Perspectives on Development and Global Change [Internet]. Second edi. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell; 2015. p. 525–48. Available from: https://diarium.usal.es/agustinferraro/files/2020/01/Roberts-Hite-and-Chorev-2015-The-Globalization-and-Development-Reader.pdf#page=539.

- Serrat, O. The Sustainable Livelihoods Approach. In: Knowledge Solutions. Springer Singapore; 2017. p. 21–6.

- Scoones, I. Sustainable rural livelihoods: a framework for analysis. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers R, Conway G. Sustainable rural livelihoods: practical concepts for the 21st century. 1992.

- Alkire S, Foster J. Counting and multidimensional poverty measurement. J Public Econ. 2011;95(7–8):476–87. [CrossRef]

- Zanganeh M, Akbari E. Zoning and spatial analysis of poverty in urban areas (Case Study: Sabzevar City-Iran). J Urban Manag. 2019;8(3):342–54. [CrossRef]

- Farrugia, N. Conceptual issues in constructing composite indices. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Saltelli, A. Composite indicators between analysis and advocacy. Soc Indic Res. 2007;81(1):65–77. [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Gamboa J, Cabrera-Barona P, Jácome-Estrella H. Financial inclusion and multidimensional poverty in Ecuador: A spatial approach. World Dev Perspect. 2021;22:100311. [CrossRef]

- Liu M, Ge Y, Hu S, Stein A, Ren Z. The spatial–temporal variation of poverty determinants. Spat Stat. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Deng Q, Li E, Zhang P. Livelihood sustainability and dynamic mechanisms of rural households out of poverty: An empirical analysis of Hua County, Henan Province, China. Habitat Int [Internet]. 2020;99:102160. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Barman P, Sarkar B, Islam N. Livelihood assessment through the sustainable livelihood security index in Majuli river Island, Assam. GeoJournal [Internet]. 2025;90(3):105. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Anselin, L. Spatial econometrics: methods and models. Vol. 4. Springer Science & Business Media; 1988. [CrossRef]

- Tian J, Sui C, Zeng S, Ma J. Spatial Differentiation Characteristics, Driving Mechanisms, and Governance Strategies of Rural Poverty in Eastern Tibet. Land. 2024;13(7). [CrossRef]

- Liu M, Ge Y, Hu S, Hao H. The Spatial Effects of Regional Poverty: Spatial Dependence, Spatial Heterogeneity and Scale Effects. ISPRS Int J Geo-Information. 2023;12(12). [CrossRef]

- Alongi, DM. Mangrove forests: resilience, protection from tsunamis, and responses to global climate change. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci. 2008;76(1):1–13.

- Walters, BB. Mangrove forests and human security. CABI Rev. 2008;(2008):1–9. [CrossRef]

- Walters, BB. Local management of mangrove forests in the Philippines: successful conservation or efficient resource exploitation? Hum Ecol. 2004;32(2):177–95. [CrossRef]

- Primavera, JH. Integrated mangrove-aquaculture systems in Asia. Integr Coast Zo Manag. 2000;121–30.

- Brown B, Fadillah R, Nurdin Y, Soulsby I, Ahmad R. Case Study: Community Based Ecological Mangrove Rehabilitation (CBEMR) in Indonesia. From small (12-33 ha) to medium scales (400 ha) with pathways for adoption at larger scales (> 5000 ha). SAPI EN S Surv Perspect Integr Environ Soc. 2014;(7.2).

- Unesco. The United Nations World Water Development Report 2021: Valuating Water. 2021st ed. Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO); 2021. 206 p.

- Choudhary N, Schuster RC, Brewis A, Wutich A. Household water insecurity affects child nutrition through alternative pathways to WASH: evidence from India. Food Nutr Bull. 2021;42(2):170–87. [CrossRef]

- Cairncross S, Valdmanis V. Water supply, sanitation and hygiene promotion (chapter 41). 2006.

- Dercon S, Gilligan DO, Hoddinott J, Woldehanna T. The impact of agricultural extension and roads on poverty and consumption growth in fifteen Ethiopian villages. Am J Agric Econ. 2009;91(4):1007–21. [CrossRef]

- Fan S, Chan-Kang C. Road development, economic growth, and poverty reduction in China. Vol. 12. Intl Food Policy Res Inst; 2005.

- Ritonga DHS. The Effectiveness Of Layanan Keuangan Tanpa Kantor Dalam Rangka Keuangan Inklusif (Laku Pandai) Study On Brilink Pt Bank Rakyat Indonesia (Persero) Tbk. North Sumatera Regional Office. Universitas Brawijaya; 2019.

- Demirgüç-Kunt A, Singer D. Financial inclusion and inclusive growth: A review of recent empirical evidence. World bank policy Res Work Pap. 2017;(8040).

- Psacharopoulos G, Patrinos* HA. Returns to investment in education: a further update. Educ Econ. 2004;12(2):111–34.

- Agency(IEA), IE. Energy Access Outlook Report. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rockström J, Falkenmark M, Folke C, Lannerstad M, Barron J, Enfors E, et al. Water resilience for human prosperity. Cambridge University Press; 2014.

- Adeningsih, SH. Capacity Building of Village-Owned Enterprises (BUMDes) in Encouraging Village Economic Welfare. Riwayat Educ J Hist Humanit. 2025;8(1):602–9. [CrossRef]

- Putra IRAS, Wibowo RA, Purwadi, Andari T, Asrori, Christy NNA, et al. Village-Owned Enterprises Perspectives Towards Challenges and Opportunities in Rural Entrepreneurship: A Qualitative Study with Maxqda Tools. Adm Sci. 2025;15(3):74. [CrossRef]

- Wulandari RD, Laksono AD, Nantabah ZK, Rohmah N, Zuardin Z. Hospital utilization in Indonesia in 2018: do urban–rural disparities exist? BMC Health Serv Res [Internet]. 2022;22(1):1–11. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Firmansyah MR, Antariksa A, Ridjal AM. Pola Ruang Pura Kahyangan Jawa Timur Dan Bali Berdasarkan Susunan Kosmos Tri Angga Dan Tri Hita Karana. Brawijaya University; 2017.

- Altbach, PG. Access means inequality. In: The international imperative in higher education. Springer; 2013. p. 21–4.

- Alkire S, Santos ME. Acute multidimensional poverty: A new index for developing countries. 2011.

- Subiyantoro H, Tarziraf A, Asmara A. The role of vocational education as the key to economic development in Indonesia. In: Proceedings of the 3rd Multidisciplinary International Conference, MIC. 2023.

- Chakravarty S, Lundberg M, Nikolov P, Zenker J. Vocational training programs and youth labor market outcomes: Evidence from Nepal. J Dev Econ. 2019;136:71–110. [CrossRef]

- Lanjouw PF, Tarp F. Poverty, vulnerability and Covid-19: Introduction and overview. Rev Dev Econ. 2021;25(4):1797–802.

- Kanbur R, Venables AJ. Spatial inequality and development overview of unu-wider project. 2005.

- Kraay A, McKenzie D. Do poverty traps exist? Assessing the evidence. J Econ Perspect. 2014;28(3):127–48.

- Collins D, Morduch J, Rutherford S, Ruthven O. Portfolios of the poor: how the world’s poor live on $2 a day. Princeton University Press; 2009.

- Ghosh, J. Microfinance and the challenge of financial inclusion for development. Cambridge J Econ. 2013;37(6):1203–19. [CrossRef]

- Barbier EB, Hacker SD, Kennedy C, Koch EW, Stier AC, Silliman BR. The value of estuarine and coastal ecosystem services. Ecol Monogr. 2011;81(2):169–93. [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, P. The economics of biodiversity: the Dasgupta review. Hm Treasury; 2021.

- Adger, WN. Social capital, collective action, and adaptation to climate change. Economic Geography79: 387-404. 2003.

- Woolcock M, Narayan D. Social capital: Implications for development theory, research, and policy. world bank Res Obs. 2000;15(2):225–49. [CrossRef]

- Putnam, RD. Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital. In: Culture and politics: A reader. Springer; 2000. p. 223–34.

- Alkire S, Roche JM, Vaz A. Changes over time in multidimensional poverty: Methodology and results for 34 countries. World Dev. 2017;94:232–49. [CrossRef]

| Livelihood Capital | Indicators |

| Human Capital | Literacy rate, school attendance, number of high schools, distance to nearest university, incidence of extraordinary disease cases, etc. |

| Social Capital | Number of village-owned enterprises (BUMDes), group participation (proxied through the presence of community security measures), neighbourhood security activation, etc. |

| Natural Capital | Access to clean water (drinking and bathing), source of drinking water (categorized into five classes), presence of mangrove ecosystem, etc. |

| Physical Capital | Road accessibility, household toilet type, electricity usage (inverse of percentage of non-users), crime variation, distance to nearest hospital, etc. |

| Financial Capital | Household income level (via proxy), number of bank agents within radius, access to a credit institution, etc. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).