1. Introduction

Sexual health is a state of physical, emotional, mental and social well-being in relation to sexuality; it is not merely the absence of disease, dysfunction or infirmity [

1]. In order to achieve and preserve sexual health, every person’s sexual rights must be respected, upheld, and fulfilled [

2]. Sexual and reproductive rights include the right and freedom of every individual to control his or her own sexual and reproductive life. Thus, adolescents and young adults should have the right to access sexual and reproductive health services and to control their own sexual and reproductive lives. Their sexual and reproductive health freedom is crucial to their overall health and well-being [

3].

Recognizing adolescent sexual and reproductive health and rights (ASRHR), the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development urged countries to address the educational and service requirements of adolescents so they can manage their sexuality in a healthy and responsible manner [

4]. According to Liang et al. (2019), ASRHR have advanced significantly in the 25 years since the 1994 conference [

5]. The 2030 Sustainable Development Goals have also motivated international efforts to enhance adolescents’ and young adults’s sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) [

6]. For example, compared to 25 years ago, adolescents are more likely to delay their first sexual experience and to use contraceptives [

5].

Despite the advancements in ASRHR over the past few years, there are still enormous challenges to be met. In Sub-Saharan Africa, where we continue to record the highest rates of sexual activity among young adolescents when compared to other regions of the world [

5], adolescents are not fully enjoying their sexual and reproductive health. Millions of girls are dropping out of school as a result of teenage pregnancies [

7]. Rural areas are disproportionately affected, with about 30% of girls becoming pregnant before the age of 19 [

7]. In Côte d’Ivoire, the number of school pregnancies is high. The National Council for Human Rights documented 3,588 cases of pregnancy in schools during the 2022-2023 academic year [

8]. About 4,137 cases of pregnancy while enrolled in schools were reported for the 2023-2024 academic year, representing a 15.3% increase compared to the previous year for the same period [

9]. According to statistics for the 2023-2024 school year, 1,313 cases of pregnancy were recorded in all administrative regions in general secondary schools, including 67 cases in Haut-Sassandra. The Haut-Sassandra region is one of the regions with the highest pregnancy rates recorded in general secondary schools [

10].

In many contexts, adolescents have limited capacity to exercise their rights with respect to sexual and reproductive health, and face unmet needs [

11,

12,

13]. In fact, the concept of freedom in terms of the sexual and reproductive rights of adolescents and young adults is not yet universally understood, accepted and/or applied. Everyone, but particularly those who interact with and play a specialized role with adolescents and young adults, must have a clear understanding of this if they are to enjoy their freedom of choice when it comes to SRHR. To the best of our knowledge, there is no information available on the freedom of choice of adolescents and young adults of Haut-Sassandra with regard to SRHR. Moreover, no study has yet been carried out to determine what Haut-Sassandra’s adult gatekeepers (ex. parents, teachers, religious leaders, and political leaders) think about adolescents’ and young adults’s SRHR. As it is important to combine adolescent-focused interventions with initiatives to increase acceptance of their implementation among adult gatekeepers [

14], we aimed to explore the perspectives of stakeholders on the freedom of choice of adolescents and young adults in Haut-Sassandra, Côte d’Ivoire, concerning sexual and reproductive health and rights.

This study is part of the Projet d’Appui à des Services de Santé Adaptés au Genre et Équitables (PASSAGE) in the Haut-Sassandra region of Côte d’Ivoire. The PASSAGE Project is a multi-sectoral initiative that adopts a comprehensive approach to health promotion. It is implemented by a consortium of Ivorian and Canadian partners. Among others, it aims to promote greater enjoyment of human rights relating to sexual and reproductive health by adolescents and young adults in the Haut-Sassandra region of Côte d’Ivoire, through targeted interventions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

This study used a qualitative descriptive research design to gain a better understanding of the perspectives of each category of stakeholder regarding adolescents’ and young adults’s freedom of choice in matters of SRHR in the Haut-Sassandra region, Côte d’Ivoire.

Data were collected in the Haut-Sassandra region, more specifically in Daloa, Gonaté and Bonoufla. Daloa is the most important town of the Haut-Sassandra region, situated in the Centre-West of Côte d’Ivoire. Daloa is located 408 km from Abidjan, the economic capital of Côte d’Ivoire [

15]. In 2021, the population of the city of Daloa was estimated at 705,378 with a population density of 184.7/km

2 [

16]. Gonaté and Bonoufla are located 24 km and 29 km from Daloa, respectively.

2.2. Study Population

Participants were stakeholders from civil society. Here we refer to actors who play a role or exert an influence in the field of SRHR in general, and more specifically among adolescents and young adults, as stakeholders. They were grouped into three categories: 1) school and university teachers and administrators; 2) community leaders; and 3) parents.

For the purposes of this study, we adopt the United Nations definition of adolescence and young adults. The United Nations does, in fact, consider adolescents to be those between the ages of 10 and 19 and young adults to be those between the ages of 15 and 24. Adolescents and young adults are collectively referred to as “youth” which includes the age range of 10 to 24 [

17,

18].

2.3. Inclusion Criteria

To be included in the study, teachers must regularly teach in an educational institution. Only primary school teachers who teach 4th grade and upwards were included in the study, to ensure that they are actually in contact with schoolchildren in the age group of interest to the project. Community leaders must be acknowledged members of the community who use their influence to provide guidance on societal issues. Their leadership must be recognized by community members. They can be political, religious, or cultural leaders. Parents must have at least one teenage or young child. All stakeholders must agree to participate in the study.

2.4. Recruitment

Participants in this study were selected using a purposive sampling method with convenience and snowball techniques [

19]. As consideration was given to the representation of men and women, as well as to that of residential areas (urban, rural, semi-urban), we planned to recruit at least 63 teachers, 60 parents and 20 community leaders, until data saturation was reached.

To recruit teachers, we contacted the administration of the target institutions, who in turn relayed the information and invited their members to take part in the study. Teachers who were interested and available on the planned data collection dates participated in the study.

Parents were recruited by the interviewers, who were divided amongst the three data collection localities. They aimed to recruit and interview parents (fathers and mothers) who met the selection criteria. After each interview, they asked the participating parent to refer other potentially interested parents.

Community leaders were also recruited by the interviewers, based on the mapping of community leaders carried out in the areas covered by the project. They contacted community leaders in their assigned areas and recruited those who were available and interested in participating in the study.

2.5. Data Collection

The interviewers were community workers with experience in data collection, who also attended an information session on study objectives and data collection procedures.

Data were collected through individual semi-structured face-to-face interviews and focus group discussions, using an interview guide. The interview guide was co-constructed by the Canadian and Ivorian partners. The Canadian partners were

Fédération des cégeps, Laval University and

the Réseau francophone international pour la promotion de la santé. The Ivorian partners were

Association Ivoirienne pour le Bien-être Familial,

Association Ivoirienne des Professionnels de la Santé Publique, Institut National de Formation des Agents de Santé, Mission des jeunes pour la Santé, la Solidarité et l’Inclusion, Ministère de l’Éducation Nationale et de l’Alphabétisation, Ministère de la Santé de l’Hygiène Publique et de la Couverture Maladie Universelle, and the

Association des infirmiers et infirmières de la Côte d’Ivoire. Together, they drew inspiration from the conceptual framework for sexual ethics of equal rights and responsibilities [

20] to formulate semi-structured interview guide questions.

The questions focused on stakeholders’ perceptions of adolescents’ and young adults’s freedom of choice or decisions regarding their sexual and reproductive health in general, and also specific topics such as choosing abstinence, choosing to have sex, choosing a partner, and deciding for oneself to go to a health centre.

Individual interview locations were selected according to participants’ preferences. Focus group discussions were conducted at teachers’ workplaces, i.e., in schools and one university. At the beginning of the interview, the interviewer introduced him or herself and gave some background information on the project and its objectives. The interviewer then presented the consent form to the participant. After the participant had read (or heard) and signed the consent form, the interviewer collected some socio-demographic information (location, urban, semi-urban or rural environment, biological sex, title/function, and age) before administering the questions from the interview guide. Interviews lasted approximately 20 to 25 mintes.

All interviews were conducted in French. Interviews were recorded using an audio recorder following written consent from the participants. All participants consented to the audio recording of the interviews. Recruitment and data collection took place between September 1 and October 31, 2023.

2.6. Data Analysis

Of the interviewers who collected the data, six were chosen to transcribe the interview audios. To take part in data transcription, interviewers had to be experienced and have access to a computer. The transcribers attended a capacity-building session given by a research team member (MMN). Transcriptions were made after the data collection phase. Audio recordings of the interviews were transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were not returned to participants for comment or correction.

We carried out a deductive thematic analysis following the six steps recommended by Braun and Clarke (2006) [

21]. Data analysis was conducted by four research team members (MMN, LGK and TTA under the supervision of MJD) including an Ivorian analyst with the necessary expertise in local terminologies. The analysis was carried out in tables using Word and Excel. Each analyst examined a sample of the verbatim responses to familiarize themselves with the data. They then proceeded individually to analyze the verbatims by stakeholder category. The team met several times to: 1) resolve issues of text comprehension related to the local terminologies used by study participants; 2) discuss differences in analysis; 3) pool results by identified theme; and 4) interpret the data. The conflicts were resolved by MJD.

The results of the analysis are presented by theme. For each theme, we include a specific quote from a participant to support the idea. The quotes have been translated from French into English for publication purposes.

We reported data using verbal counting such as few, some, many, and most [

22]. We define few as occurring in less than 20% of participants, some as occurring between 30 and 50%, many as occurring between 50 and 70% and most occurring for more than 70% of participants. This applies to all participants or to each category of participants.

We reported this study using the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ), a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups [

23].

2.7. Ethical Considerations

The project was approved by the Comité National d’Éthique des Sciences de la Vie et de la Santé in Côte d’Ivoire (N/Réf: 114-23/MSHPCMU/CNESVS-km) and by the Research Ethics Committee of the CHU de Québec-Université Laval in Canada (Project 2024-7017).

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Participants

Table 1 presents the socio-demographic characteristics of the participants. Overall, 137 stakeholders participated in the study: twenty primary, secondary and university teachers, 12 community leaders and 63 parents. Five focus group discussions were conducted with 37 school and university teachers and administrators. There were 6 to 9 participants per focus group. One focus group was conducted with five community leaders.

The overall mean age was 46.1. For stakeholders who participated in individual interviews, the mean age was 41.6 for teachers and administrators, 55.6 for community leaders and 41.2 years for parents. A third of the stakeholders came from an urban area (Daloa), another third came from a semi-urban area (Bonoufla) and the rest from a rural area (Gonaté).

3.2. Main Results

3.2.1. Age as a Determinant of Freedom

Study participants’ perceptions of freedom of choice in sexual and reproductive health for adolescents and young adults vary. Age appears to be the main factor determining adolescents’ and young adults’s freedom of choice concerning their sexual and reproductive health (SRH). For some stakeholders, age is the condition that determines absolute freedom or the absence of freedom.

Absolute Freedom for Ages 18 and Over

Some teachers, one community leader and few fathers think that adolescents and young adults are free to make their own choices about SRH.

“Indeed, given the fact that in Côte d’Ivoire today, children of the age group you’ve just mentioned are already in school and being taught about contraceptive methods, we believe that this is a reality, so we have to give them the freedom to make their choice; otherwise, it will be an infringement of their rights.” High school teacher, participant #19

This opinion has been nuanced by most mothers who said that absolute freedom of choice only made sense for young adults aged 18 to 24, adding that not giving them this choice is violating their rights. In addition, from the point of view of some community leaders and teachers, from the age of 18 - 24, adolescents and young adults can freely make their choice without any intermediary. This opinion is also shared by one father who thinks that children should have this free choice from puberty onwards, or as soon as they are old enough to get married.

“No, the teenager isn’t old enough, because we’re talking about a teenager who isn’t old enough to get married. He’s got to take it easy first. Everything has its time. When his time comes, he’ll get married to avoid a lot of things.” Parent – father, participant #48

Absolute freedom of choice also applies to the choice of partner for certain stakeholders. For the choice of partner or the choice of having a partner, teachers and fathers believe that everyone should be free to choose his or her partner, as forced marriage is not a good practice. Parents should not oppose their children’s choice of partner. A young person over 18 is free to have a partner. One father also points out that, contrary to what is expected, there are certain parents who encourage/pressure their daughters to find a partner.

No Freedom for Adolescents and Young Adults Under 18

Lack of freedom is due to young age (mostly young adolescence). Some teachers believe that adolescents and those between the ages of 10 and 18 should not be free to make their own choices about their sexual and reproductive health. The same applies to community leaders who said that it doesn’t make sense for children to be free to make their own choices when it comes to SRH. As pointed out by one of them, 10 years old is too young to choose. Even two fathers are adamant that 10-year-olds aren’t free to make their own choices and shouldn’t even be involved in such matters. As stated by a mother: “A 10-year-old can’t decide anything.” Another mother says she doesn’t support teenagers’ freedom in this respect. Thus, several mothers believe that it’s the parent, or the mother specifically, who must decide or make the choices for their adolescents in matters of sexual health.

“That’s what I always say, the girl if she’s 14, her parents can decide for her but when she’s 24, she’s a woman and decides for herself.” Parent - mother, participant #54.

Even, when it comes to the choice of abstinence or having sexual relations, some community leaders and parents believe that sexuality must have a well-defined framework. Sexuality concerns married people. Adolescents and young adults must remain abstinent until marriage. Once married, they can take certain liberties. They think adolescents are too young to talk about sex and to start having sex. According to their perception, it’s not normal for children to have sex. They must be abstinent until they reach the appropriate age. One mother said that a 10-year-old can’t have sex.

“I think that from the age of 10 to 18, they’re not allowed to talk about sex. At least if you say from 18 to 24, they’re a bit mature on their own and can make their own choices. From 10 to 18, frankly, I don’t agree with that.” Parent - mother, participant #43.

Lack of freedom also applies to the choice to consult a health service, as parents believe they should accompany their children to the health centers, firstly, to be present at their side, and secondly to prevent their children from withholding information from them.

“No, she[talking about the teenage girl or young woman]needs to be accompanied, because right now it’s very dangerous. If she makes a choice like that, it’s as if she’s free. No, she must be accompanied. You have to accompany her, or a parent to accompany her is better.” Parent – mother, participant #51

3.2.2. Other Conditions Pertaining to Freedom

In addition to age, stakeholders grant conditional freedom of choice to adolescents and young adults. Thus, freedom of choice is also conditional on parental involvement, education, autonomy and perceived maturity. Conditional freedom of choice also applies to the choice of partner for certain stakeholders.

Prior Education and Parental Involvement

Some teachers believe that adolescents and young adults are free to make their choice as long as they are sensitized and educated.

Community leaders, teachers and mothers highlight the need for the involvement of parents with respect to freedom of choice in general and the choice of their children’s partner. They say adolescents and young adults are free, but there’s always a BUT! For instance, community leaders recognize that it’s not up to parents to choose their child’s partner, but children should involve their parents in the choice of the partner, to receive advice. Two fathers said that adolescents need their parents’ support, and they need to communicate with them and involve them in their choices. This also reflects the mothers’ position. One community leader stated that the young girl needs her mother’s advice.

“ ...it’s your mother who has to accompany you, even to choose, because in any case you have to confide in your mother, even if you love someone, you have to[take him to see your parents]. It’s the old people who know who’s good and who’s not. When you[the parent]talk to the person you’ve sent, he will find out if he[the partner]wants to get serious with your child or not. Mom knows. You don’t just get up and throw yourself at him, and say that’s who I want. You can choose him, but you have to talk to the parents. The parents will talk to him and that’s it.” Parent - mother, participant #60

The condition of parents ‘involvement also applies to the choice of partner. One teacher goes further, stating that free choice is too much, because parents must help children choose a partner. Another said that parents must approve the chosen partner; otherwise, traditional marriage cannot take place. Moreover, for those under 18, this also applies to the choice of partner. According to two mothers, from the age of 15 - 16, children can decide to have a partner. As one mother puts it, “From 16 onwards, my daughter can have a boyfriend, but the boy has to come to the house, because even if you refuse, they’ll do it outside.” In other words, parents’ opposition to adolescent girls having boyfriends can encourage them to be secretive.

“Well... leaving them free to make their choices is a bit of libertarianism. I think that… from the age of 10 to 18, the child can’t choose his or her partner. The child can’t afford to go out at any time without parental consent. But over 18s, as they are said to have come of age, they[the teenagers or young adults]can come home with their partner to introduce them to the family, so that the parents can help them to see if the partner is alright[if the partner is recommendable].” Primary school teacher, participant #20

Conditional freedom also applies to the choice of healthcare services. In fact, some community leaders believe that young adults need their parents’ permission to visit a health center.

Autonomy

According to parents, another condition for adolescents’ freedom of choice when it comes to SRH is autonomy. Parents think that adolescents can’t make decisions on their own, as they fall under their responsibility. As one father said: “Whoever has the means money can make his/her decision.” Thus, adolescents and young adults can decide for themselves when they grow up.

Perceived Maturity

Due to perceived maturity, parents grant a kind of relative freedom to adolescents and young adults. Indeed, parents (fathers and mothers) think that freedom of choice in this context is relative and depends on the children. As they said, there are intelligent children who care about their health, children who do what they want, and children who find it hard to contain themselves, etc. Some children are free to make their own choices, while others need advice.

“It all depends on the child. There are intelligent children, but there are also children who do what they want. Intelligent children know that when there’s health, it’s for themselves. There are also children who don’t listen to anyone; they do what they want. “Parent - father, participant #33.

No Condition

It is just with respect to the choice to consult a health service that teachers do not set any conditions. They believe that young adults should systematically visit dedicated health centers to receive advice and make informed choices about their sexuality. They shouldn’t wait until they reach the age of majority to get the information they need. This perception of teachers is different from that of mothers and community leaders.

3.2.3. Reasons Why Stakeholders Believe Adolescents and Young Adults Do Not Have Freedom of Choice Regarding Their Sexual and Reproductive Health

There are many reasons why stakeholders believe that adolescents and young adults aged between 10 and 18 do not have freedom of choice when it comes to their SSR. In their view, this freedom is synonymous with giving their children an inadequate upbringing, encouraging promiscuity and disengagement. At this age, they are still immature and don’t realize the consequences of their actions. They risk making bad decisions that will catch up with them later. They run the risk of being abused. This can lead to unwanted pregnancies.

Also, they’re still under parental control and dependent on them. For other stakeholders, adolescents shouldn’t talk about sex or be interested in sexual relationships. The only choice they must make is abstinence. They have to be advised, guided and supervised by their parents, who must make decisions for their young children. Their sexuality must, therefore, be controlled by their parents. Some stakeholders believe that children should be forbidden to have sex until they are mature.

Finally, stakeholders also pointed out that the cultural and religious context imposes an attitude on adolescents and young adults. For example, according to Islam, young adults should not have sex before marriage.

3.2.4. Reasons Why Stakeholders Believe That Adolescents and Young Adults Have Freedom of Choice Regarding Their Sexual and Reproductive Health

Because they recognize the rights of adolescents and young adults, as well as the importance of health, some stakeholders believe that they have freedom of choice regarding their sexual and reproductive health. Other justifications include the fact that the choice is a personal one, and that young adults make it for their own benefit. For this reason, they need to take their choice seriously. Free choice enables them to take charge of their own lives. They inform themselves through the media, and expose themselves to all kinds of information on sexuality, which allows them to make their own choices. Free choice enables them to go to health centers for information, to opt for a contraceptive method to avoid unwanted pregnancies, and to choose the partner that suits them.

“… you can’t force a child to do something because today... all children have access to the media, so the child is exposed to all kinds of sexual teaching; so, it’s preferable to educate the child and allow him, give him the freedom, to choose what he should do but at the same time encourage him to really follow what can be, will be good for his future. There you go. You can’t force something on a child...; the child has the full right to choose his sexual education...” Secondary school teacher, focus group #3, participant #3

3.2.5. Strategies Used by Parents to Prevent Children from Taking SRH Liberties

To prevent children from taking SRH liberties, parents use a few strategies. First and foremost, all stakeholders agree that parents need to talk to their children, advise them, educate them, raise awareness and encourage them to learn about family planning. Many of them insist on educating girls.

Some parents advise them to abstain for religious reasons, and in their opinion, abstinence will enable them to concentrate on their studies, extend their education, and avoid sexually transmitted diseases, as well as unwanted pregnancies. Some parents keep an eye on their children to prevent them from getting into mischief, as they say. This surveillance can take the form of controlling outings and dating, imposing curfews, etc. Other parents may even force their preferences on their adolescents and young children.

“At a certain age, children do what they want, and it’s us parents who have to force them not to get pregnant. We have to watch over them to make sure they don’t do anything stupid and now, from the age of 17, they indulge in a lot of things; otherwise in my house it’s abstinence or nothing before marriage.” Parent - father, participant #47.

3.2.6. Summary of the Different Types of Freedom

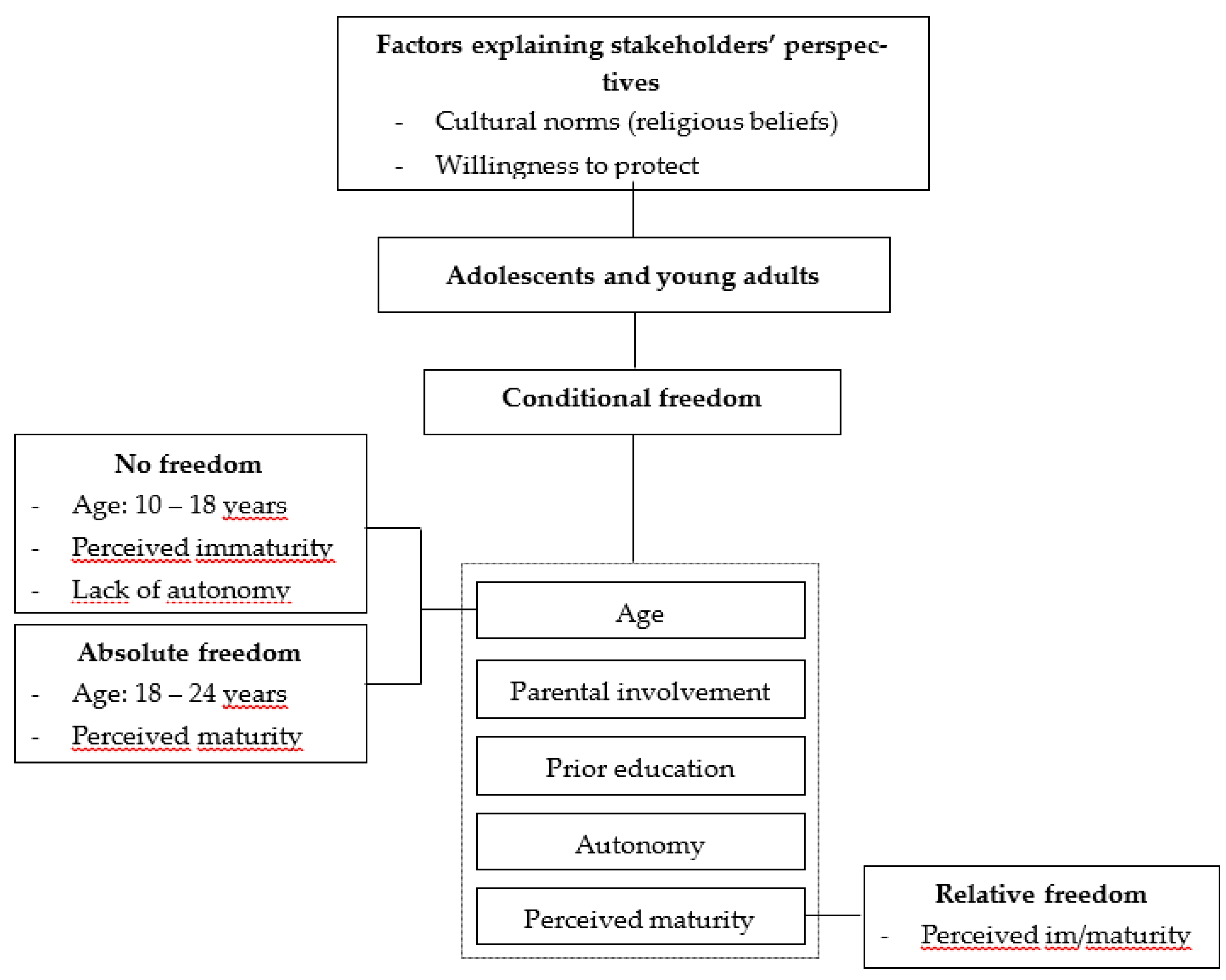

There are many conditions affecting the freedom of choice of adolescents and young adults: age, parental involvement, prior education, autonomy and perceived maturity. The factors causing the lack of freedom are age (10 – 18 years), perceived immaturity and lack of autonomy. The factor linked to relative freedom is perceived maturity or immaturity. The factors that promote absolute freedom are age (18 – 24 years) and perceived maturity.

Factors explaining stakeholders’ perspectives on the freedom of adolescents and young adults with regard to sexual and reproductive health and rights are cultural norms (religious beliefs), willingness to protect and the feeling of disengagement (See

Figure 1).

4. Discussion and Interpretation

In this study, we explored the perspectives of stakeholders on the freedom of choice of adolescents and young adults with regard to sexual and reproductive health and rights in Haut-Sassandra, Côte d’Ivoire. We found that there were many conditions affecting the freedom of choice of adolescents and young adults. These conditions determine the type of freedom granted to them. It may be an absolute lack of freedom, or conditional or even relative freedom. Factors explaining stakeholders’ perspectives on the freedom of adolescents and young adults with respect to sexual and reproductive health and rights are cultural norms (religious beliefs), the desire to protect and the feeling of disengagement. These results lead us to make the following observations.

First, there is a lack of stakeholder consistency in the concept of freedom of choice for adolescents and young adults in matters of SHRH. There is a level of maturity that stakeholders expect in order to give teenagers and young adults total freedom of choice. If there is freedom, it depends on the age of the adolescent or young adult and thus on “a kind of systematic perceived maturity” related to majority (18 years old+). Clearly, maturity is mostly equated here with age. However, even if age is an important factor, it’s difficult to consider it as the only factor of maturity. Maturity is measurable with a set of characteristics related to emotional, intellectual, moral, social, and biological dimensions; and can not be considered only from an anthropological or morphological perspective [

24]. Moreover, participants often respond using the term “child or children,” rather than “adolescents and young adults.” It would seem that Louis-Philippe Dalembert’s quote: “In the eyes of parents, especially mothers, children never grow up...” applies even more to the Haut-Sassandra context. This can also be explained by the fact that in many communities, the notion of adolescence does not exist. We simply go from childhood to adulthood. Interventions with stakeholders should help them understand the needs of the new generation of children, regardless of their maturity.

Second, we found that for most stakeholders, there is always a “BUT” to the freedom of choice of adolescents and young adults. While they assert the need for parental input, the limit of their input remains unclear. A priori, we can say that it is normal that adolescents and young adults inform their parents and discuss such matters with them, and that parents, in turn, advise their children. One can even say that it’s not so much a condition! But the teachers’ reaction leads us to believe that it could be a little more than simple advice, in the sense that the parents’ opinion really counts. This applies to the extent that sometimes, if their opinion is not considered, this could prevent certain decisions/actions by the young adolescent, such as choosing a partner, especially in the African context, where the blessing of the parents is important and can be decisive for a successful marriage. This even calls into question the absolute freedom of adolescents and young adults over 18 years old in regard to SRHR. Also, those supporting conditional freedom speak as if the age of minority refers to the time to receive sexual education/counseling and the age of majority corresponds to the time they can initiate sexual activities; and that those two times are sequential and cannot occur concurrently. In fact, it seems as if education is replacing the freedom of choice of adolescents and young adults under 18 years old. In order to meet the objectives of the PASSAGE project and Sustainable Development Goals concerning the health and well-being of populations and workers, interventions with this population should therefore focus on knowledge and awareness of adolescents’ sexual and reproductive rights, to enable them to have a fulfilling sexual and reproductive life.

Third, this study identifies factors explaining stakeholders’ perspectives on the freedom of adolescents and young adults with respect to sexual and reproductive health and rights. These factors include root causes such as religious norms. However, for effective interventions, further studies need to be conducted to have an accurate picture of all root factors explaining stakeholders’ perspectives. For instance, as highlighted by Hindin and Fatusi (2009), it might be difficult for today’s parents to impart important knowledge to their children because the majority of them were not taught sexual and reproductive health by their own parents or even in school [

25]. Thus, a parent who didn’t have freedom in matters of sexual and reproductive health during his or her adolescence will tend to reproduce the same pattern with his or her children, ignoring the fact that the environment in which they grew up differs greatly from that of their children. Moreover, the views of stakeholders should be confronted with those of adolescents and young adults. All this should be further explored, as the data from the latter suggest a gap between the different perspectives.

This study has several limitations. First, we considered both the sexual and reproductive health of adolescents and young adults, and therefore a broad age range. This led some of the study participants to often choose the age range that spoke to or challenged them the most in their responses. Second, some participants had low literacy skills. As a result, some responses were difficult to understand and analyse. However, this concerned very few participants and our Ivorian analyst helped us understand some of these responses. Third, our study did not explore stakeholders’ socio-demographic factors that could explain their different perspectives. However, we recruited several categories of stakeholders belonging to different generations, which enabled us to gain cross-generational viewpoints. Several young stakeholders seemed to share the same opinion as older stakeholders. Finally, we don’t qualitatively explore adolescents’ and young adults’ perspectives on their freedom of choice about the SRHR.

5. Conclusions

This study explored the perspectives of stakeholders on the freedom of choice of adolescents and young adults regarding sexual and reproductive health and rights in Haut-Sassandra, Côte d’Ivoire. There are many conditions affecting the freedom of choice of adolescents and young adults that determine the type of freedom granted to them. Multiple factors explain stakeholders’ perspectives on the freedom of adolescents and young adults with regard to SRH. This study highlights the need to carry out interventions focusing on stakeholders’ knowledge and awareness of adolescents’ sexual and reproductive rights.

Author Contributions

Funding acquisition, conceptualization, and methodology: A.A., J.R., S.D., M.J.D.; Data curation: M.K., S.D.; Formal analysis: T.T.A., M.M.N., L.G.K., M.J.D.; Writing– original draft: T.T.A., M.J.D.; Writing– review & editing: All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

The PASSAGE project is funded by Global Affairs Canada.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all partners, in particular the field team in the Ivory Coast, the interviewers and transcribers, for their contribution to this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SRHR |

Sexual and reproductive health rights |

| ASRHR |

Adolescent sexual and reproductive health and rights |

| PASSAGE |

Projet d’Appui à des Services de Santé Adaptés au Genre et Équitables |

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Sexual and Reproductive Health and Research (SRH). Including the Human Reproduction Special Programme (HRP). Defining sexual health. Available online: https://www.who.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Sexual health and its linkages to reproductive health: an operational approach. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/978924151288. ISSN: 9241512881. 2017.

- United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). Adolescent sexual and reproductive health. Health sector national guidelines. Available online: https://platform.who.int/docs/default-source/mca-documents/policy-documents/guideline/swz-ad-17-01-guideline-2013-eng-adolescent-sexual-and-reproductive-health---health-sector-na.pdf; 2013.

- United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). Programme of Action of the International Conference on Population Development. 20th Anniversary Edition. 2014. Available online: https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/programme_of_action_Web%20ENGLISH.

- Liang, M.; Simelane, S.; Fillo, G.F.; Chalasani, S.; Weny, K.; Canelos, P.S.; Jenkins, L.; Moller, A.-B.; Chandra-Mouli, V.; Say, L. The state of adolescent sexual and reproductive health. Journal of Adolescent Health 2019, 65, S3–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowshin, N.; Kapiriri, L.; Davison, C.M.; Harms, S.; Kwagala, B.; Mutabazi, M.G.; Niec, A. Sexual and reproductive health and rights of “last mile” adolescents: a scoping review. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters 2022, 30, 2077283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denya, T.S. Teen pregnancy hinders education in sub-Saharan Africa. Available online: https://www.developmentaid.org/news-stream/post/186346/teen-pregnancy-in-sub-saharan-africa.

- Conseil National des Droits de l’Homme (CNDH). Rapport Annuel CNDH 2023. Available online: https://cndh.ci/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/RAP-ANNUEL-2023-CNDH.pdf; 2023; p 67.

- Conseil National des Droits de l’Homme (CNDH). Communiqué de presse numéro 3. Available online: https://cndh.ci/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/COMMUNIQUE-DE-PRESSE-N%C2%B003.pdf. 2024.

- Ministère de l’éducation nationale et de l’alphabétisation. Direction des stratégies, de la planification et des statistiques. Statistiques scolaires de poche, Rapport 2023-2024. MENA / DESPS. 2024.

- Iqbal, S.; et al. Perceptions of adolescents’ sexual and reproductive health and rights: a cross-sectional study in Lahore District, Pakistan. BMC international health and human rights 2017, 17, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remez, L.; Woog, V.; Mhloyi, M. Sexual and reproductive health needs of adolescents in Zimbabwe. Available online: https://www.guttmacher.org/report/sexual-and-reproductive-health-needs-adolescents-zimbabwe. Guttmacher Institute. 2014 Series, No. 3.

- Rashid, S.F. Human rights and reproductive health: political realities and pragmatic choices for married adolescent women living in urban slums, Bangladesh. BMC International Health and Human Rights 2011, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandra-Mouli, V.; Svanemyr, J.; Amin, A.; Fogstad, H.; Say, L.; Girard, F.; Temmerman, M. Twenty years after International Conference on Population and Development: where are we with adolescent sexual and reproductive health and rights? Journal of Adolescent Health 2015, 56, S1–S6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OCDE/CSAO. L'économie locale du département de Daloa - Synthèse, Écoloc, Gérer l'économie localement en Afrique : Évaluation et prospective, Éditions OCDE, Paris. 2002. [CrossRef]

- Brinkhoff, T. Daloa, Department in Ivory Coast. 2022. Available online: https://www.citypopulation.de/en/ivorycoast/admin/haut_sassandra/1011__daloa/.

- Morris, J.L.; Rushwan, H. Adolescent sexual and reproductive health: The global challenges. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 2015, 131, S40–S42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). Adolescent and youth demographics: A brief overview. Available online: http://www.unfpa.org/resources/adolescent-and-youth-demographicsa-brief-overview.

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Fourth Edition. Sage publications. ISBN 978-1-5063-3020-4; 2016.

- Dixon-Mueller, R.; Germain, A.; Fredrick, B.; Bourne, K. Towards a sexual ethics of rights and responsibilities. Reproductive Health Matters 2009, 17, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandelowski, M. Real qualitative researchers do not count: The use of numbers in qualitative research. Research in nursing & health 2001, 24, 230–240. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International journal for quality in health care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rerke, V.I. Scientific discourse on the categories of “maturity” and “psychological maturity” of personality. Education & Pedagogy Journal 2023, 2, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Hindin, M.J.; Fatusi, A.O. Adolescent sexual and reproductive health in developing countries: an overview of trends and interventions. International perspectives on sexual and reproductive health 2009, 35, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).