Submitted:

13 August 2025

Posted:

14 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

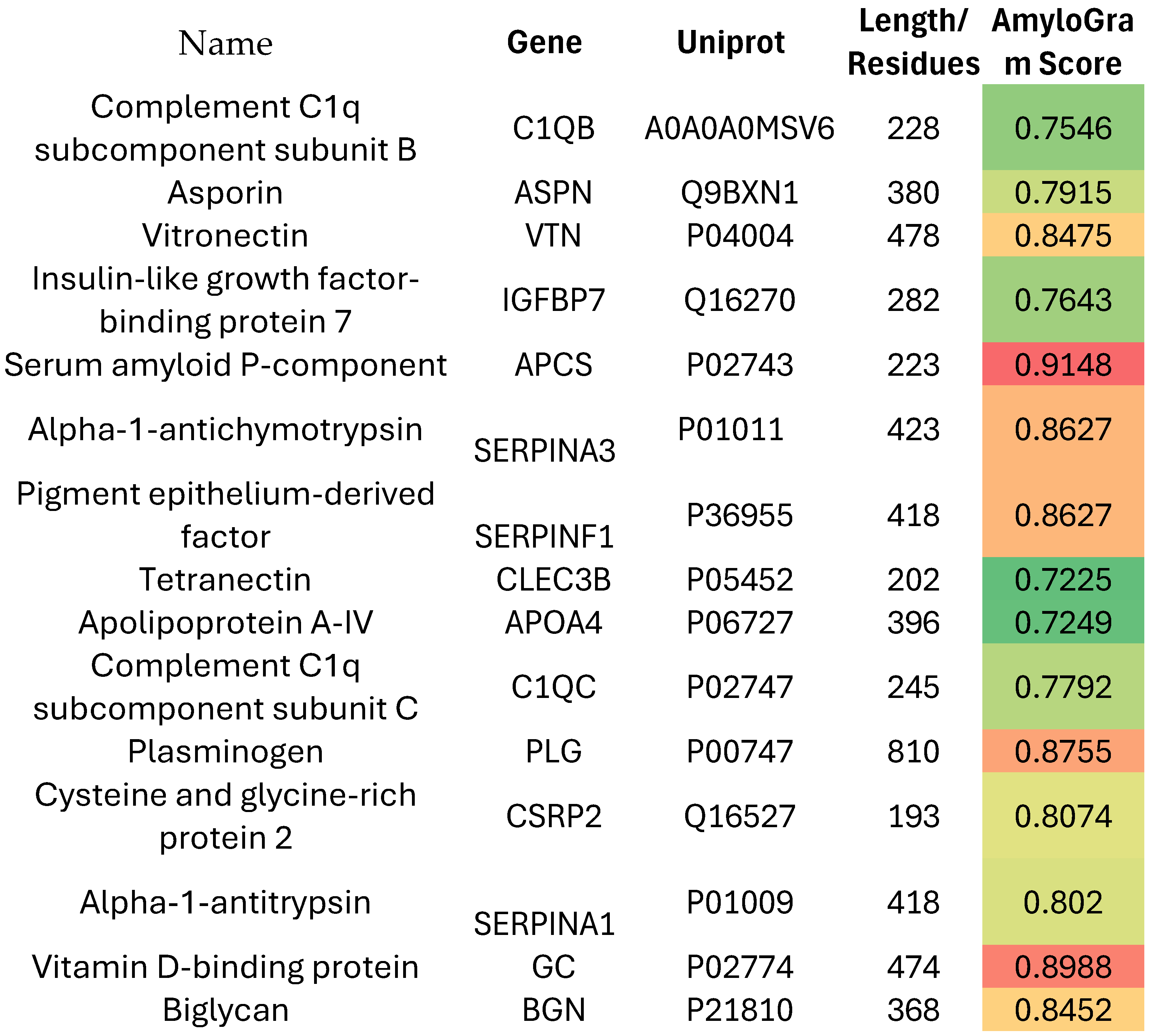

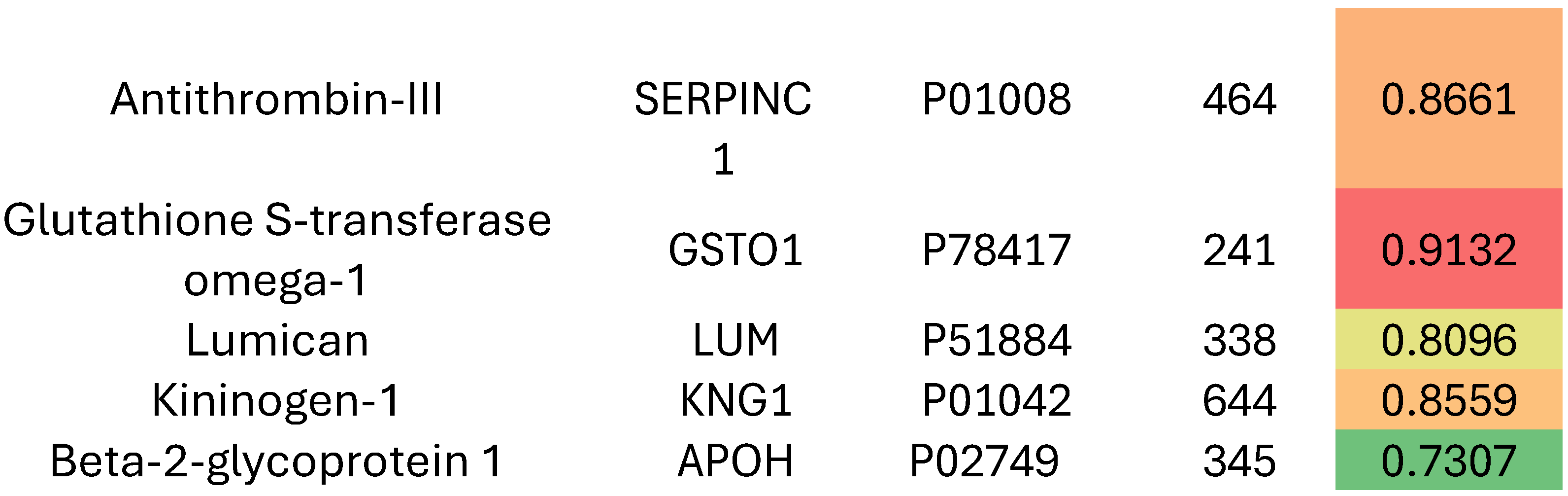

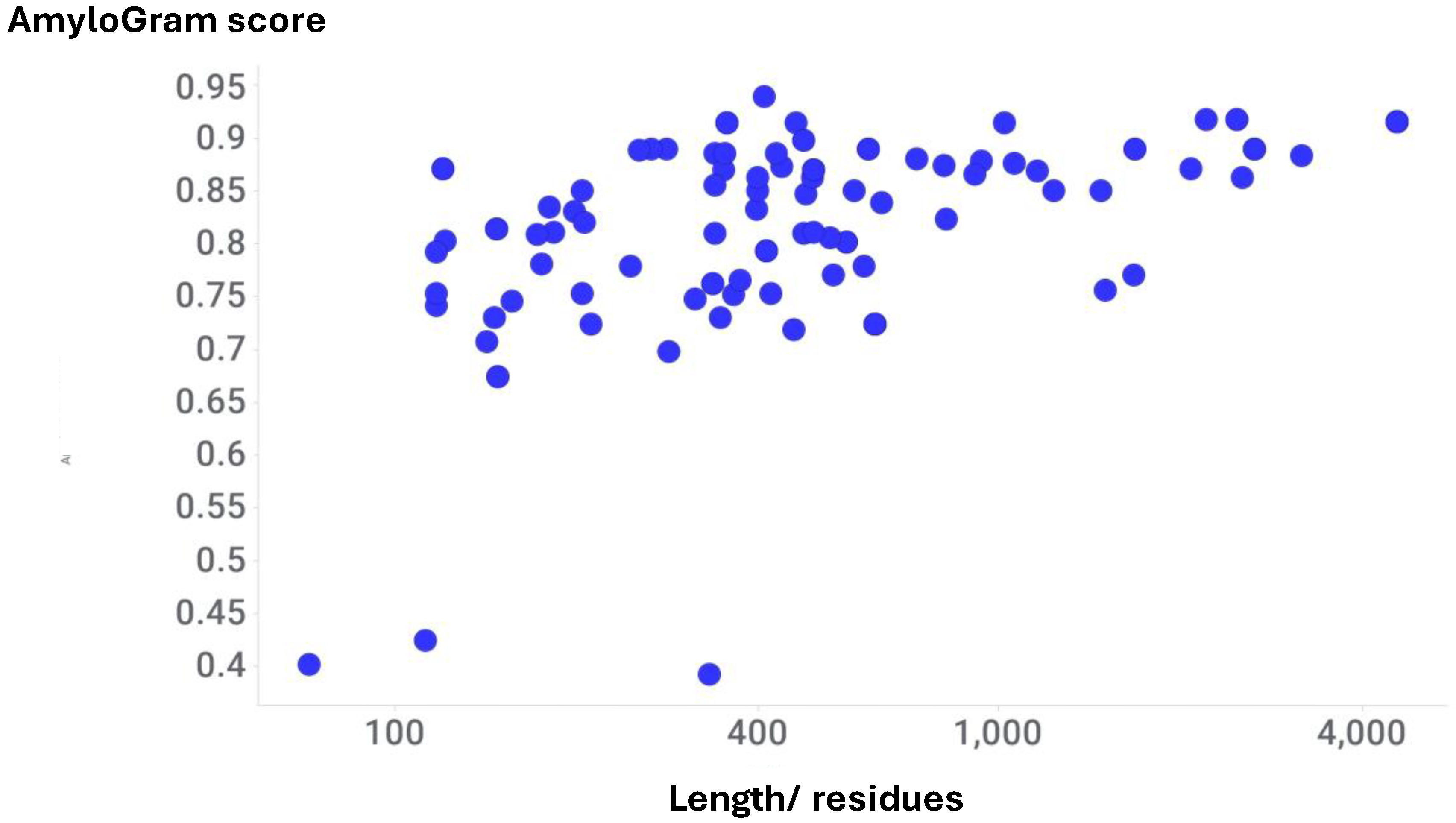

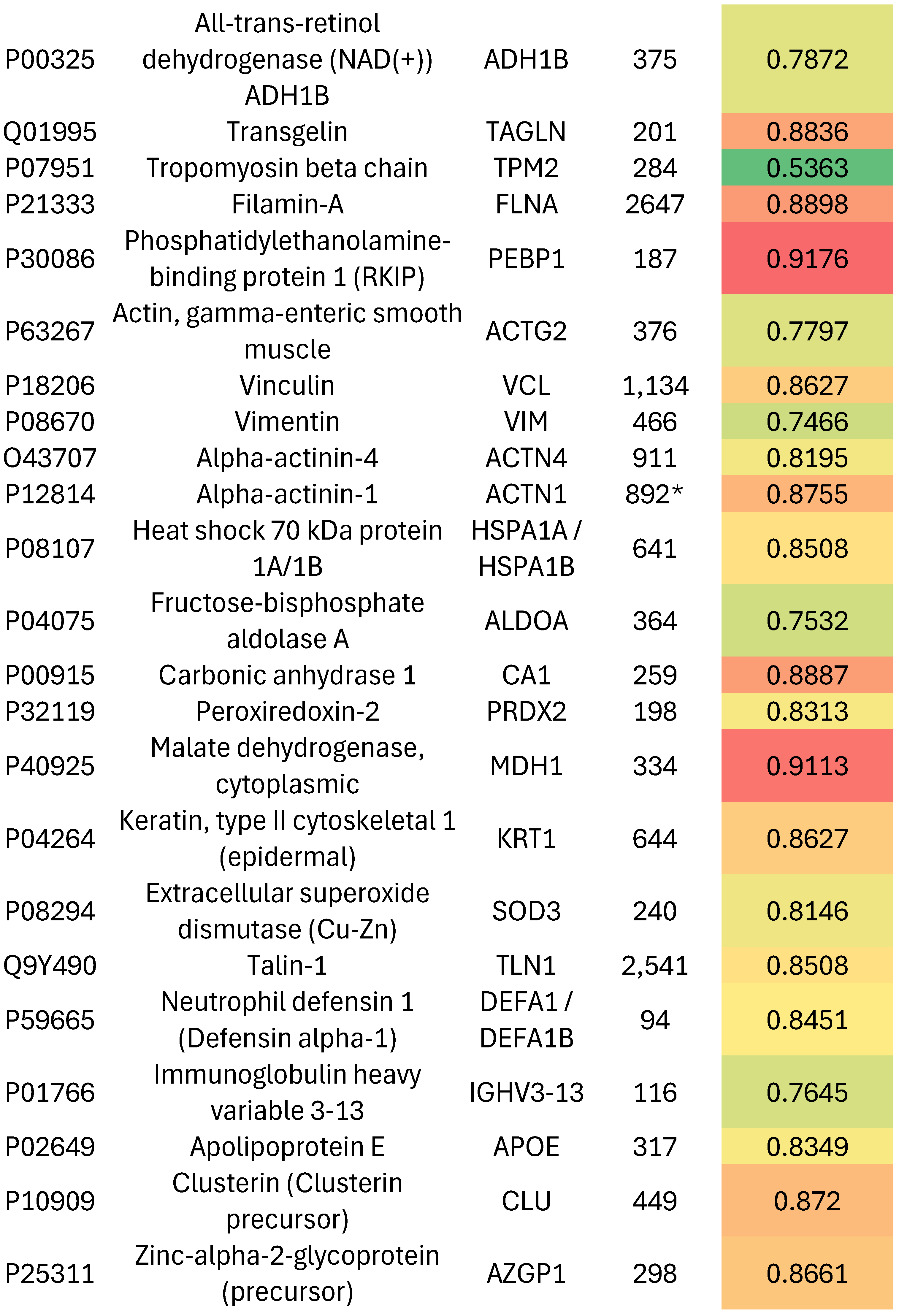

Results

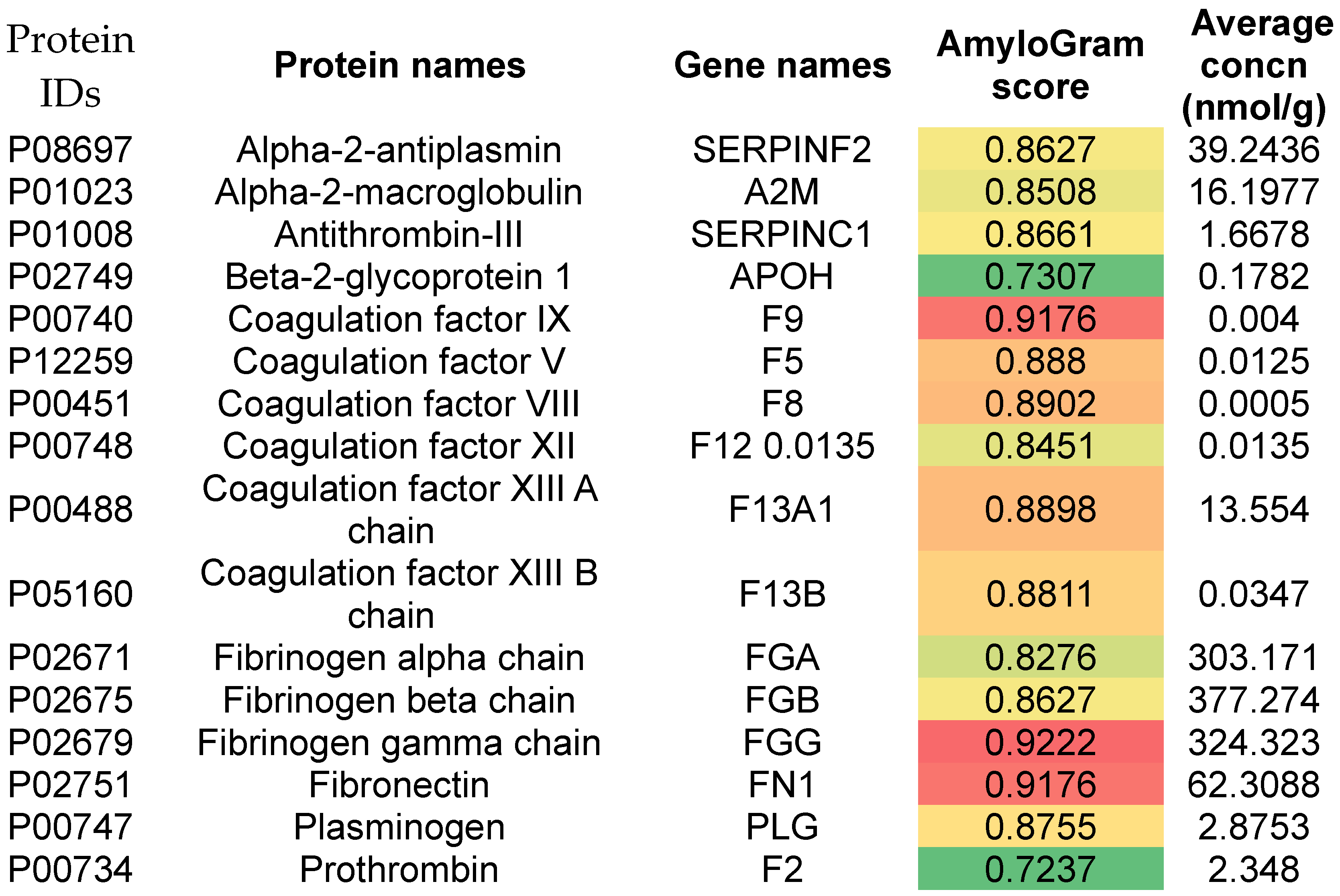

Venous Thromboembolism

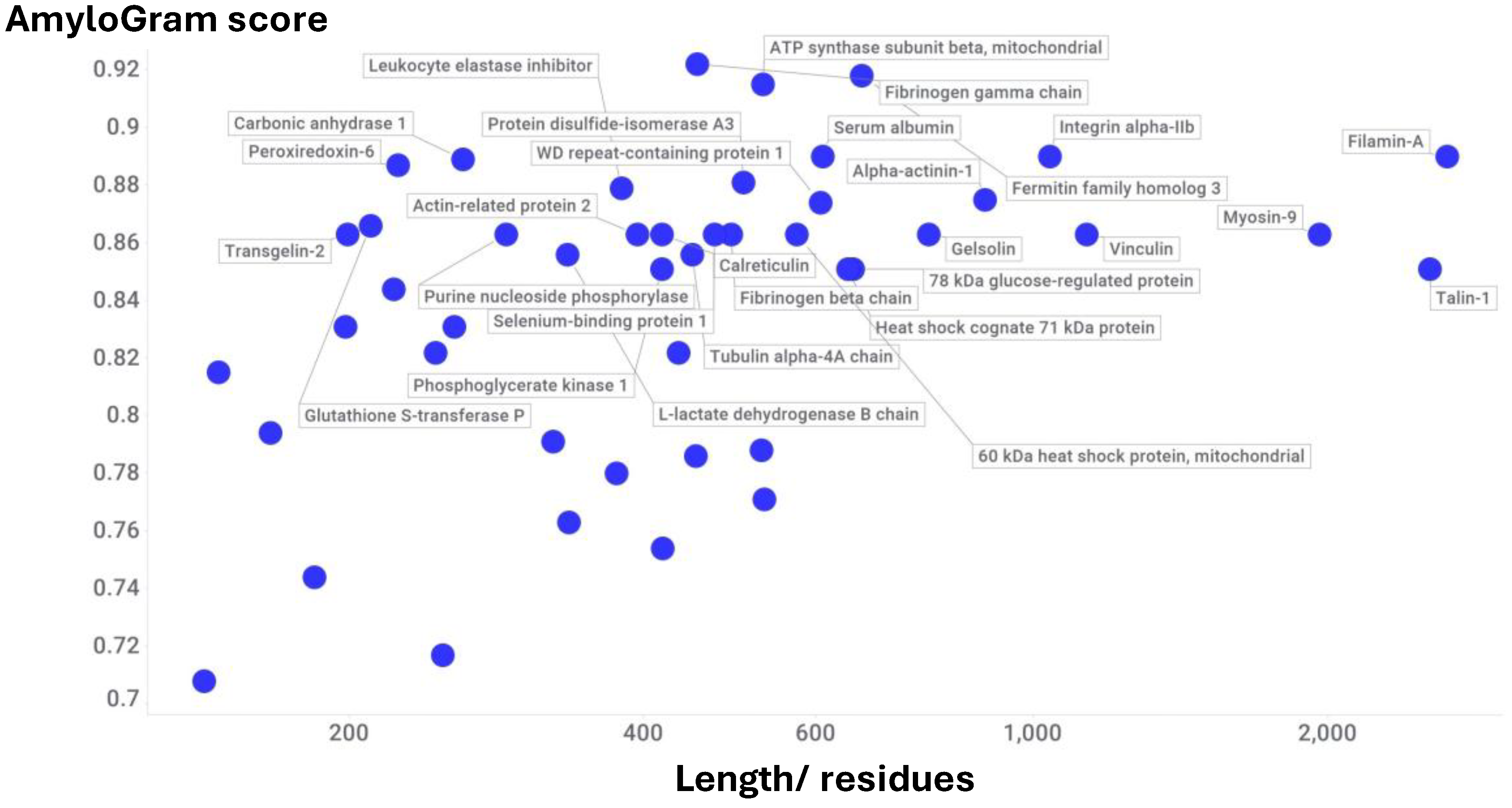

Pulmonary Embolism

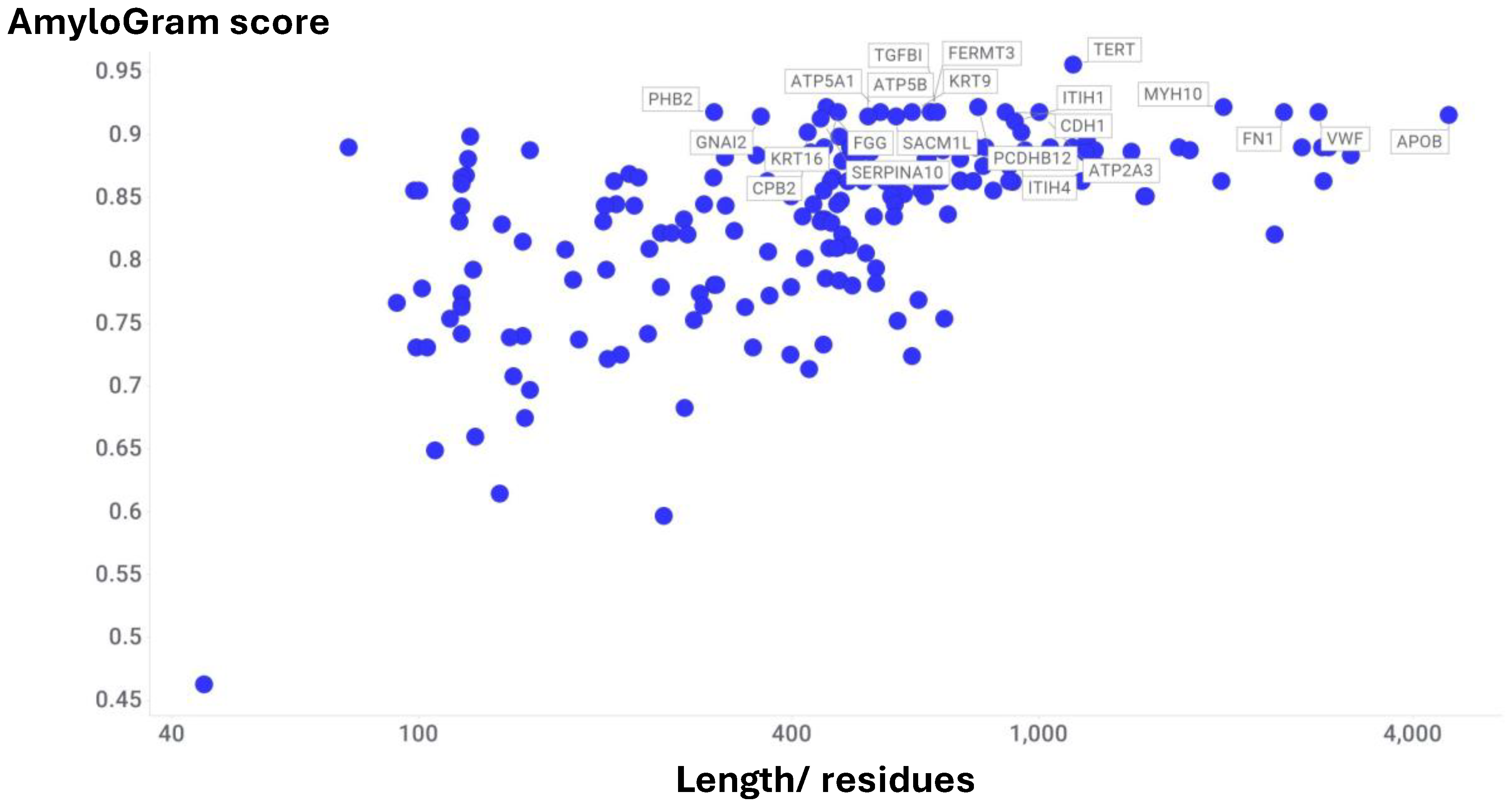

Atherosclerosis and Acute Myocardial Infarction

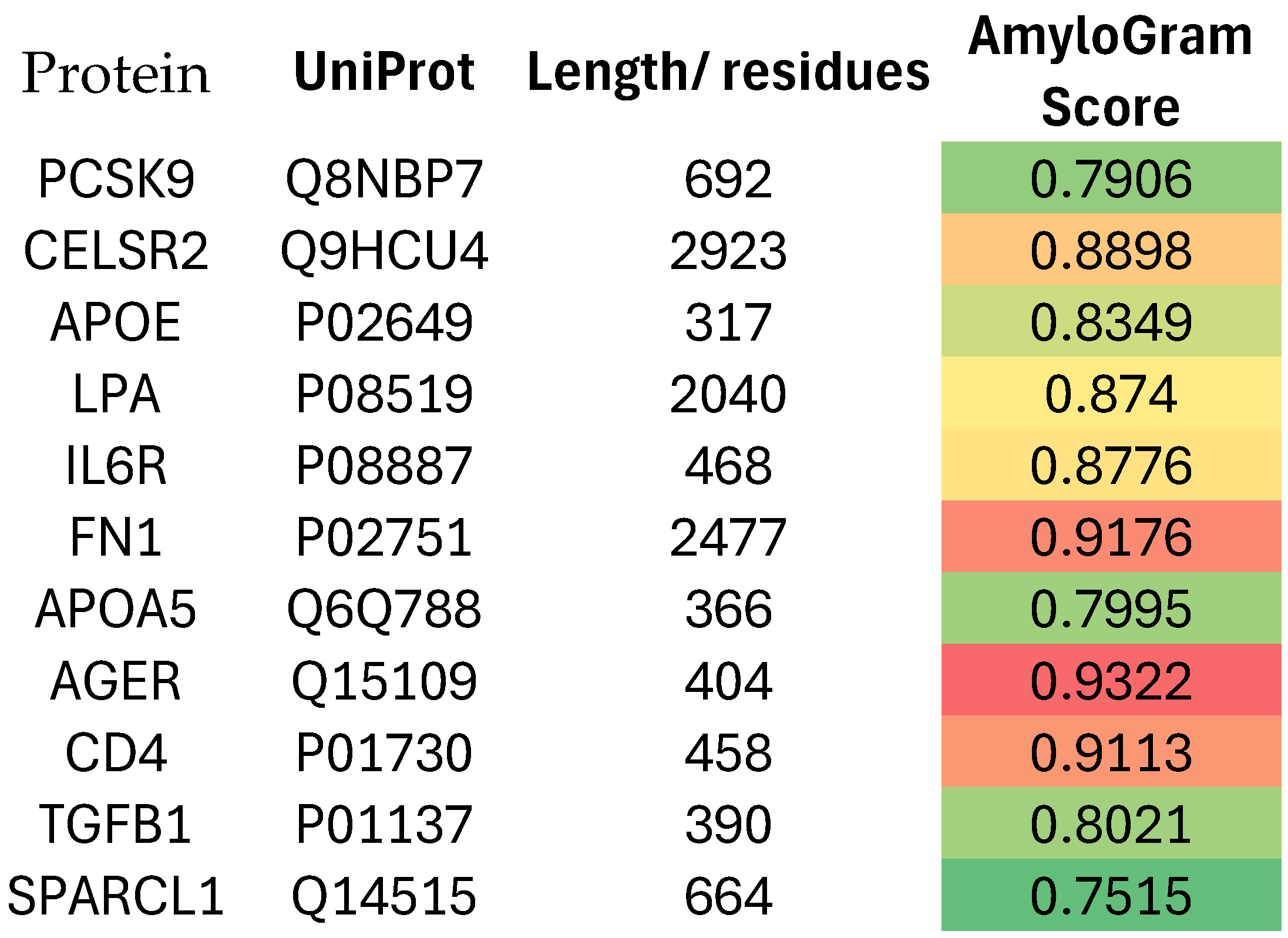

Fold-Switching Proteins

Discussion

Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pretorius, E. , Mbotwe, S., Bester, J., Robinson, C. J. and Kell, D. B. (2016) Acute induction of anomalous and amyloidogenic blood clotting by molecular amplification of highly substoichiometric levels of bacterial lipopolysaccharide. J R Soc Interface 2016, 123, 20160539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretorius, E. , Page, M. J., Hendricks, L., Nkosi, N. B., Benson, S. R. and Kell, D. B. (2018) Both lipopolysaccharide and lipoteichoic acids potently induce anomalous fibrin amyloid formation: assessment with novel Amytracker™ stains. J R Soc Interface 2018, 15, 20170941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kell, D. B. , Laubscher, G. J. and Pretorius, E. (2022) A central role for amyloid fibrin microclots in long COVID/PASC: origins and therapeutic implications. Biochem J 2022, 479, 537–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kell, D. B. and Pretorius, E. (2023) Are fibrinaloid microclots a cause of autoimmunity in Long Covid and other post-infection diseases? Biochem J 2023, 480, 1217–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, J. M. , Kruger, A., Proal, A., Kell, D. B. and Pretorius, E. (2022) The occurrence of hyperactivated platelets and fibrinaloid microclots in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS). Research Square 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, J. M. , Kruger, A., Proal, A., Kell, D. B. and Pretorius, E. (2022) The occurrence of hyperactivated platelets and fibrinaloid microclots in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS). Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2022, 15, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, S. , Naidoo, C., Usher, T., Kruger, A., Venter, C., Laubscher, G. J., Khan, M. A., Kell, D. B. and Pretorius, E. (2022) Increased levels of inflammatory molecules in blood of Long COVID patients point to thrombotic endotheliitis. medRxiv 2022, 2022.2010.2013.22281055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, S. , Khan, M. A., Putrino, D., Woodcock, A., Kell, D. B. and Pretorius, E. (2023) Long COVID: pathophysiological factors and abnormal coagulation. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2023, 34, 321–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, C. F. , de Oliveira, M. I. R., Stafford, P., Peake, N., Kane, B., Higham, A., Singh, D., Jackson, N., Davies, H., Price, D., Duncan, R., Tattersall, N., Barnes, A. and Smith, D. P. (2024) Increased fibrinaloid microclot counts in platelet-poor plasma are associated with Long COVID. medRxiv 2024, 2024.2004.2004.24305318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grixti, J. M. , Chandran, A., Pretorius, J. H., Walker, M., Sekhar, A., Pretorius, E. and Kell, D. B. (2024) The clots removed from ischaemic stroke patients by mechanical thrombectomy are amyloid in nature. medRxiv 2024, 10.1101/2024.1111.1101.24316555v24316551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grixti, J. M. , Theron, C. W., Salcedo-Sora, J. E., Pretorius, E. and Kell, D. B. (2024) Automated microscopic measurement of fibrinaloid microclots and their degradation by nattokinase, the main natto protease. J Exp Clin Appl Chin Med 2024, 5, 30–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kell, D. B. , Khan, M. A., Kane, B., Lip, G. Y. H. and Pretorius, E. (2024) Possible role of fibrinaloid microclots in Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS): focus on Long COVID. J Personalised Medicine 2024, 14, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kell, D. B. and Pretorius, E. (2024) Potential roles of fibrinaloid microclots in fibromyalgia syndrome. OSF preprint. [CrossRef]

- Kell, D. B. , Lip, G. Y. H. and Pretorius, E. (2024) Fibrinaloid Microclots and Atrial Fibrillation. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kell, D. B. and Pretorius, E. (2024) Proteomic evidence for amyloidogenic cross-seeding in fibrinaloid microclots. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 10809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kell, D. B. and Pretorius, E. (2025) The proteome content of blood clots observed under different conditions: successful role in predicting clot amyloid(ogenicity). Molecules 2025, 30, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kell, D. B. , Pretorius, E. and Zhao, H. (2025) A direct relationship between ‘blood stasis’ and fibrinaloid microclots in chronic, inflammatory and vascular diseases, and some traditional natural products approaches to treatment. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grixti, J. M. , Chandran, A., Pretorius, J. H., Walker, M., Sekhar, A., Pretorius, E. and Kell, D. B. (2025) Amyloid presence in acute ischemic stroke thrombi: observational evidence for fibrinolytic resistance. Stroke 2025, 56, e165–e167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blancas-Mejía, L. M. and Ramirez-Alvarado, M. (2013) Systemic amyloidoses. Annu Rev Biochem 2013, 82, 745–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavatelli, F. , di Fonzo, A., Palladini, G. and Merlini, G. (2016) Systemic amyloidoses and proteomics: The state of the art. EuPA Open Proteom 2016, 11, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nevone, A. , Merlini, G. and Nuvolone, M. (2020) Treating protein misfolding diseases: therapeutic successes against systemic amyloidoses. Front Pharmacol 2020, 11, 1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palladini, G. and Merlini, G. (2013) Systemic amyloidoses: what an internist should know. Eur J Intern Med 2013, 24, 729–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhuri, P. , Prajapati, K. P., Anand, B. G., Dubey, K. and Kar, K. (2019) Amyloid cross-seeding raises new dimensions to understanding of amyloidogenesis mechanism. Ageing Res Rev 2019, 56, 100937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, W. Y. , Deng, X., Shi, W. P., Lin, W. J., Chen, L. L., Liang, H., Wang, X. T., Zhang, T. D., Zhao, F. Z., Guo, W. H. and Yin, D. C. (2023) Amyloid protein cross-seeding provides a new perspective on multiple diseases in vivo. Biomacromolecules 2023, 24, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, M. I. , Lin, Y., Lee, Y. H., Zheng, J. and Ramamoorthy, A. (2021) Biophysical processes underlying cross-seeding in amyloid aggregation and implications in amyloid pathology. Biophys Chem 2021, 269, 106507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, J. , Hellstrand, E., Hammarström, P. and Nyström, S. (2023) SARS-CoV-2 Spike amyloid fibrils specifically and selectively accelerates amyloid fibril formation of human prion protein and the amyloid β peptide. bioRxiv 2023, 2023.2009.2001.555834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, B. , Zhang, Y., Zhang, M., Liu, Y., Zhang, D., Gong, X., Feng, Z., Tang, J., Chang, Y. and Zheng, J. (2019) Fundamentals of cross-seeding of amyloid proteins: an introduction. J Mater Chem B 2019, 7, 7267–7282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westermark, G. T. , Fandrich, M., Lundmark, K. and Westermark, P. (2018) Noncerebral Amyloidoses: Aspects on Seeding, Cross-Seeding, and Transmission. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2018, 8, a024323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruger, A. , Vlok, M., Turner, S., Venter, C., Laubscher, G. J., Kell, D. B. and Pretorius, E. (2022) Proteomics of fibrin amyloid microclots in Long COVID/ Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) shows many entrapped pro-inflammatory molecules that may also contribute to a failed fibrinolytic system. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2022, 21, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretorius, E. , Vlok, M., Venter, C., Bezuidenhout, J. A., Laubscher, G. J., Steenkamp, J. and Kell, D. B. (2021) Persistent clotting protein pathology in Long COVID/ Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) is accompanied by increased levels of antiplasmin. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2021, 20, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schofield, J. , Abrams, S. T., Jenkins, R., Lane, S., Wang, G. and Toh, C. H. (2024) Microclots, as defined by amyloid-fibrinogen aggregates, predict risks of disseminated intravascular coagulation and mortality. Blood Adv 2024, 8, 2499–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, V. , Chilimoniuk, J., Pintado-Grima, C., Barcenas, O., Ventura, S. and Burdukiewicz, M. (2024) Aggregating amyloid resources: A comprehensive review of databases on amyloid-like aggregation. Comput Struct Biotechnol J 2024, 23, 4011–4018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdukiewicz, M. , Sobczyk, P., Rödiger, S., Duda-Madej, A., Mackiewicz, P. and Kotulska, M. (2017) Amyloidogenic motifs revealed by n-gram analysis. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 12961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szulc, N. , Burdukiewicz, M., Gąsior-Głogowska, M., Wojciechowski, J. W., Chilimoniuk, J., Mackiewicz, P., Šneideris, T., Smirnovas, V. and Kotulska, M. (2021) Bioinformatics methods for identification of amyloidogenic peptides show robustness to misannotated training data. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 8934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

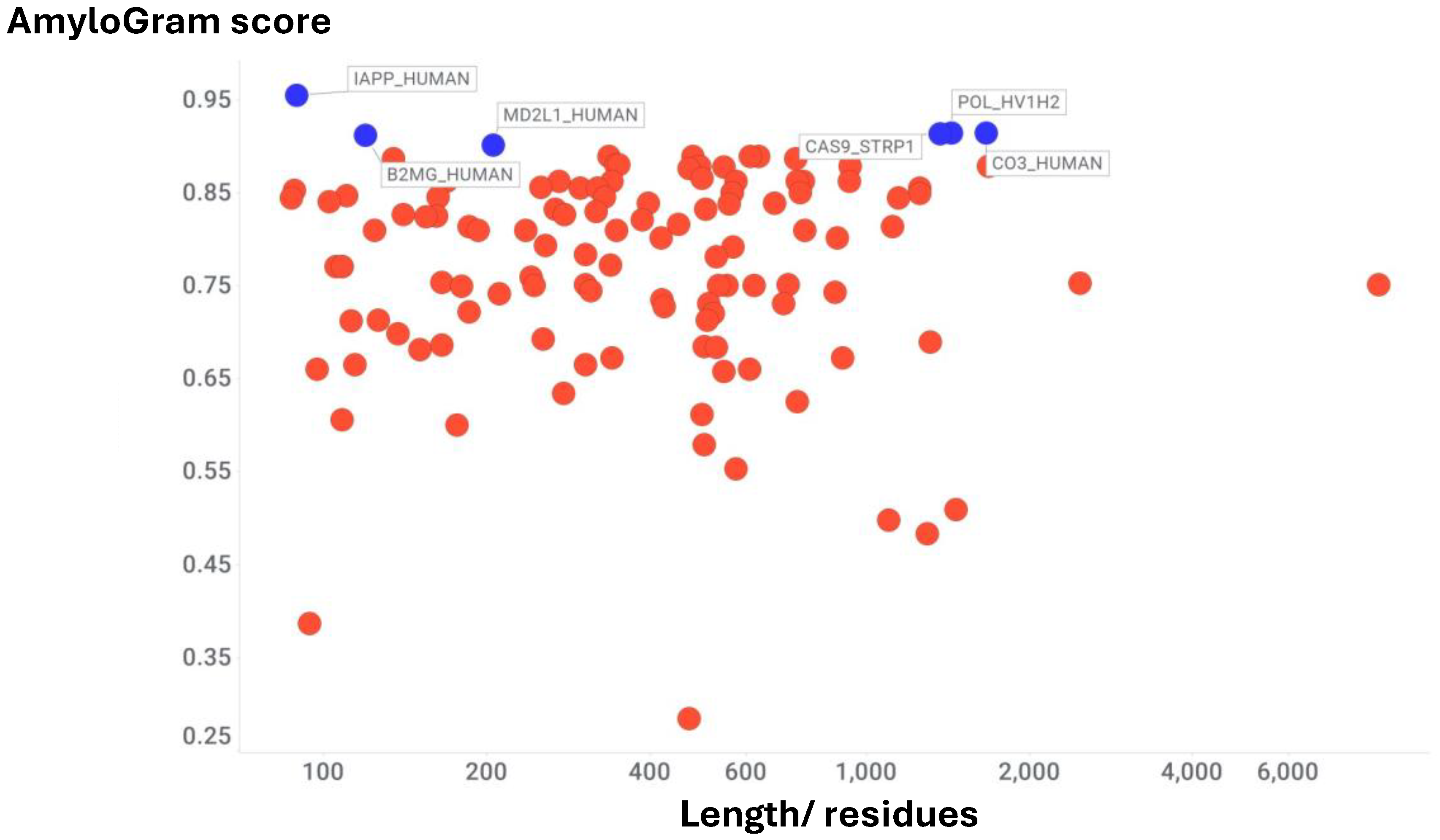

- Kell, D. B. , Doyle, K. M., Salcedo-Sora, E., Sekhar, A., Walker, M. and Pretorius, E. (2025) AmyloGram reveals amyloidogenic potential in stroke thrombus proteomes. bioRxiv 2025, 2025.2007.2007.663482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stachowicz, A. , Siudut, J., Suski, M., Olszanecki, R., Korbut, R., Undas, A. and Wisniewski, J. R. (2017) Optimization of quantitative proteomic analysis of clots generated from plasma of patients with venous thromboembolism. Clin Proteomics 2017, 14, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryk, A. H. , Natorska, J., Ząbczyk, M., Zettl, K., Wisniewski, J. R. and Undas, A. (2020) Plasma fibrin clot proteomics in patients with acute pulmonary embolism: Association with clot properties. J Proteomics 2020, 229, 103946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieddu, G. , Formato, M. and Lepedda, A. J. (2023) Searching for Atherosclerosis Biomarkers by Proteomics: A Focus on Lesion Pathogenesis and Vulnerability. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 15175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, P. , Ren, Y., Pasterkamp, G., Moll, F. L., de Kleijn, D. P. V. and Sze, S. K. (2014) Deep proteomic profiling of human carotid atherosclerotic plaques using multidimensional LC-MS/MS. Proteomics Clin Appl 2014, 8, 631–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragonès, G. , Auguet, T., Guiu-Jurado, E., Berlanga, A., Curriu, M., Martinez, S., Alibalic, A., Aguilar, C., Hernandez, E., Camara, M. L., Canela, N., Herrero, P., Ruyra, X., Martin-Paredero, V. and Richart, C. (2016) Proteomic profile of unstable atheroma plaque: increased neutrophil defensin 1, clusterin, and apolipoprotein E levels in carotid secretome. J Proteome Res 2016, 15, 933–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagnato, C. , Thumar, J., Mayya, V., Hwang, S. I., Zebroski, H., Claffey, K. P., Haudenschild, C., Eng, J. K., Lundgren, D. H. and Han, D. K. (2007) Proteomics analysis of human coronary atherosclerotic plaque: a feasibility study of direct tissue proteomics by liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry. Mol Cell Proteomics 2007, 6, 1088–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso-Orgaz, S. , Moreno-Luna, R., López, J. A., Gil-Dones, F., Padial, L. R., Moreu, J., de la Cuesta, F. and Barderas, M. G. (2014) Proteomic characterization of human coronary thrombus in patients with ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction. J Proteomics 2014, 109, 368–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langley, S. R. , Willeit, K., Didangelos, A., Matic, L. P., Skroblin, P., Barallobre-Barreiro, J., Lengquist, M., Rungger, G., Kapustin, A., Kedenko, L., Molenaar, C., Lu, R., Barwari, T., Suna, G., Yin, X., Iglseder, B., Paulweber, B., Willeit, P., Shalhoub, J., Pasterkamp, G., Davies, A. H., Monaco, C., Hedin, U., Shanahan, C. M., Willeit, J., Kiechl, S. and Mayr, M. (2017) Extracellular matrix proteomics identifies molecular signature of symptomatic carotid plaques. J Clin Invest 2017, 127, 1546–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorentzen, L. G. , Hansen, G. M., Iversen, K. K., Bundgaard, H. and Davies, M. J. (2022) Proteomic Characterization of Atherosclerotic Lesions In Situ Using Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Angioplasty Balloons-Brief Report. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2022, 42, 857–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandran, M. , S, S., Abhirami, Chandran, A., Jaleel, A. and Plakkal Ayyappan, J. (2023) Defining atherosclerotic plaque biology by mass spectrometry-based omics approaches. Mol Omics 2023, 19, 6–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theofilatos, K. , Stojkovic, S., Hasman, M., van der Laan, S. W., Baig, F., Barallobre-Barreiro, J., Schmidt, L. E., Yin, S., Yin, X., Burnap, S., Singh, B., Popham, J., Harkot, O., Kampf, S., Nackenhorst, M. C., Strassl, A., Loewe, C., Demyanets, S., Neumayer, C., Bilban, M., Hengstenberg, C., Huber, K., Pasterkamp, G., Wojta, J. and Mayr, M. (2023) Proteomic Atlas of Atherosclerosis: The Contribution of Proteoglycans to Sex Differences, Plaque Phenotypes, and Outcomes. Circ Res 2023, 133, 542–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-González, G. , Meschia, J. F., Madden, B. J., Prudencio, M., Polania-Sandoval, C. A., Hartwell, J., Oyefeso, E., Benchaaboune, R., Brigham, T., Sandhu, S. J. S., Charlesworth, C., Pujari, G. P., Petrucelli, L., Pandey, A. and Erben, Y. (2024) Recent advances in proteomic analysis to study carotid artery plaques. JVS Vasc Sci 2024, 5, 100215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorentzen, L. G. , Yeung, K., Eldrup, N., Eiberg, J. P., Sillesen, H. H. and Davies, M. J. (2024) Proteomic analysis of the extracellular matrix of human atherosclerotic plaques shows marked changes between plaque types. Matrix Biol Plus 2024, 21, 100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorentzen, L. G. , Yeung, K., Zitkeviciute, A., Yang-Jensen, K. C., Eldrup, N., Eiberg, J. P. and Davies, M. J. (2025) N-Terminal Proteomics Reveals Distinct Protein Degradation Patterns in Different Types of Human Atherosclerotic Plaques. J Proteome Res 2025, 24, 144–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C. , Feng, Y., Liu, X., Sun, H., Guo, Z., Shao, J., Li, K., Chen, J., Shu, K., Kong, D., Wang, J., Li, Y., Lei, X., Li, C., Liu, B., Sun, W. and Lai, Z. (2025) Molecular landscape of atherosclerotic plaque progression: insights from proteomics, single-cell transcriptomics and genomics. BMC Med 2025, 23, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H. , Xie, F., Wang, M., Ji, J., Song, Y., Dai, Y., Wang, L., Kang, Z. and Cao, L. (2025) Identification of potential therapeutic targets for coronary atherosclerosis from an inflammatory perspective through integrated proteomics and single-cell omics. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26, 6201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocchiccioli, S. , Pelosi, G., Rosini, S., Marconi, M., Viglione, F., Citti, L., Ferrari, M., Trivella, M. G. and Cecchettini, A. (2013) Secreted proteins from carotid endarterectomy: an untargeted approach to disclose molecular clues of plaque progression. J Transl Med 2013, 11, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bale, M. D. , Westrick, L. G. and Mosher, D. F. (1985) Incorporation of thrombospondin into fibrin clots. J Biol Chem 1985, 260, 7502–7508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bale, M. D. and Mosher, D. F. (1986) Effects of thrombospondin on fibrin polymerization and structure. J Biol Chem 1986, 261, 862–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bale, M. D. (1987) Noncovalent and covalent interactions of thrombospondin with polymerizing fibrin. Semin Thromb Hemost 1987, 13, 326–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, C. , Ward, N. L., Rice, M., Ball, N. J., Walle, P., Najdek, C., Kilinc, D., Lambert, J. C., Chapuis, J. and Goult, B. T. (2024) The structure of an amyloid precursor protein/talin complex indicates a mechanical basis of Alzheimer's disease. Open Biol 2024, 14, 240185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otake, M. and Abe, D. (2023) Coronary Artery Thrombus in Cardiac Amyloidosis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2023, 16, 2454–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westermark, P. , Mucchiano, G., Marthin, T., Johnson, K. H. and Sletten, K. (1995) Apolipoprotein A1-derived amyloid in human aortic atherosclerotic plaques. Am J Pathol 1995, 147, 1186–1192. [Google Scholar]

- Mucchiano, G. I. , Jonasson, L., Haggqvist, B., Einarsson, E. and Westermark, P. (2001) Apolipoprotein A-I-derived amyloid in atherosclerosis. Its association with plasma levels of apolipoprotein A-I and cholesterol. Am J Clin Pathol 2001, 115, 298–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howlett, G. J. and Moore, K. J. (2006) Untangling the role of amyloid in atherosclerosis. Curr Opin Lipidol 2006, 17, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teoh, C. L. , Griffin, M. D. and Howlett, G. J. (2011) Apolipoproteins and amyloid fibril formation in atherosclerosis. Protein Cell 2011, 2, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlett, G. J. , Ryan, T. M. and Griffin, M. D. W. (2019) Lipid-apolipoprotein interactions in amyloid fibril formation and relevance to atherosclerosis. Biochim Biophys Acta Proteins Proteom 2019, 1867, 502–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khowdiary, M. M. , Al-Kuraishy, H. M., Al-Gareeb, A. I., Albuhadily, A. K., Elhenawy, A. A., Rashwan, E. K., Alexiou, A., Papadakis, M., Fetoh, M. E. A. and Batiha, G. E. (2025) The Peripheral Amyloid-beta Nexus: Connecting Alzheimer's Disease with Atherosclerosis through Shared Pathophysiological Mechanisms. Neuromolecular Med 2025, 27, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansmeier, N. , Buttigieg, J., Kumar, P., Pelle, S., Choi, K. Y., Kopriva, D. and Chao, T. C. (2018) Identification of mature atherosclerotic plaque proteome signatures using aata-independent acquisition mass spectrometry. J Proteome Res 2018, 17, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riek, R. and Eisenberg, D. S. (2016) The activities of amyloids from a structural perspective. Nature 2016, 539, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biancalana, M. , Makabe, K. and Koide, S. (2010) Minimalist design of water-soluble cross-beta architecture. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010, 107, 3469–3474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahn, T. R. , Makin, O. S., Morris, K. L., Marshall, K. E., Tian, P., Sikorski, P. and Serpell, L. C. (2010) The common architecture of cross-beta amyloid. J Mol Biol 2010, 395, 717–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, R. , Sawaya, M. R., Balbirnie, M., Madsen, A. O., Riekel, C., Grothe, R. and Eisenberg, D. (2005) Structure of the cross-beta spine of amyloid-like fibrils. Nature 2005, 435, 773–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabaté, R. and Ventura, S. (2013) Cross-beta-sheet supersecondary structure in amyloid folds: techniques for detection and characterization. Methods Mol Biol 2013, 932, 237–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawaya, M. R. , Hughes, M. P., Rodriguez, J. A., Riek, R. and Eisenberg, D. S. (2021) The expanding amyloid family: Structure, stability, function, and pathogenesis. Cell 2021, 184, 4857–4873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biancalana, M. , Makabe, K., Koide, A. and Koide, S. (2009) Molecular mechanism of thioflavin-T binding to the surface of beta-rich peptide self-assemblies. J Mol Biol 2009, 385, 1052–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biancalana, M. and Koide, S. (2010) Molecular mechanism of Thioflavin-T binding to amyloid fibrils. Biochim Biophys Acta 2010, 1804, 1405–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gade Malmos, K. , Blancas-Mejia, L. M., Weber, B., Buchner, J., Ramirez-Alvarado, M., Naiki, H. and Otzen, D. (2017) ThT 101: a primer on the use of thioflavin T to investigate amyloid formation. Amyloid 2017, 24, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, C. , Lin, T. Y., Chang, D. and Guo, Z. (2017) Thioflavin T as an amyloid dye: fibril quantification, optimal concentration and effect on aggregation. R Soc Open Sci 2017, 4, 160696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiti, F. and Dobson, C. M. (2009) Amyloid formation by globular proteins under native conditions. Nat Chem Biol 2009, 5, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, F. E. and Prusiner, S. B. (1998) Pathologic conformations of prion proteins. Annu Rev Biochem 1998, 67, 793–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arden, B. G. , Borotto, N. B., Burant, B., Warren, W., Akiki, C. and Vachet, R. W. (2020) Measuring the Energy Barrier of the Structural Change That Initiates Amyloid Formation. Anal Chem 2020, 92, 4731–4735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kell, D. B. and Pretorius, E. (2017) Proteins behaving badly. Substoichiometric molecular control and amplification of the initiation and nature of amyloid fibril formation: lessons from and for blood clotting. Progr Biophys Mol Biol 2017, 123, 16–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noji, M. , Samejima, T., Yamaguchi, K., So, M., Yuzu, K., Chatani, E., Akazawa-Ogawa, Y., Hagihara, Y., Kawata, Y., Ikenaka, K., Mochizuki, H., Kardos, J., Otzen, D. E., Bellotti, V., Buchner, J. and Goto, Y. (2021) Breakdown of supersaturation barrier links protein folding to amyloid formation. Commun Biol 2021, 4, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arutyunyan, A. , Seuma, M., Faure, A. J., Bolognesi, B. and Lehner, B. (2025) Massively parallel genetic perturbation suggests the energetic structure of an amyloid-beta transition state. Sci Adv 2025, 11, eadv1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frauenfelder, H. , Sligar, S. G. and Wolynes, P. G. (1991) The energy landscapes and motions of proteins. Science 1991, 254, 1598–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, I. A. , Haft, D. H., Getzoff, E. D., Tainer, J. A., Lerner, R. A. and Brenner, S. (1985) Identical short peptide sequences in unrelated proteins can have different conformations: a testing ground for theories of immune recognition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1985, 82, 5255–5259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrudan, A. , Pujalte Ojeda, S., Joshi, C. K., Greenig, M., Engelberger, F., Khmelinskaia, A., Meiler, J., Vendruscolo, M. and Knowles, T. P. J. (2025) Multi-state Protein Design with DynamicMPNN. ed.)^eds.). arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.21938. [Google Scholar]

- Bonomi, M. and Vendruscolo, M. (2019) Determination of protein structural ensembles using cryo-electron microscopy. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2019, 56, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Osés, G. , Osuna, S., Gao, X., Sawaya, M. R., Gilson, L., Collier, S. J., Huisman, G. W., Yeates, T. O., Tang, Y. and Houk, K. N. (2014) The role of distant mutations and allosteric regulation on LovD active site dynamics. Nat Chem Biol 2014, 10, 431–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osuna, S. , Jiménez-Osés, G., Noey, E. L. and Houk, K. N. (2015) Molecular dynamics explorations of active site structure in designed and evolved enzymes. Acc Chem Res 2015, 48, 1080–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tycko, R. (2015) Amyloid polymorphism: structural basis and neurobiological relevance. Neuron 2015, 86, 632–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubrey, L. D. , Blakeman, B. J. F., Lutter, L., Serpell, C. J., Tuite, M. F., Serpell, L. C. and Xue, W. F. (2020) Quantification of amyloid fibril polymorphism by nano-morphometry reveals the individuality of filament assembly. Commun Chem 2020, 3, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S. , Baghel, D., Edmonds, H. O. and Ghosh, A. (2024) Heterotypic Seeding Generates Mixed Amyloid Polymorphs. Small Sci 2024, 4, 2400109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Q. , Boyer, D. R., Sawaya, M. R., Ge, P. and Eisenberg, D. S. (2019) Cryo-EM structures of four polymorphic TDP-43 amyloid cores. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2019, 26, 619–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, G. , Fennema Galparsoro, D., Sancataldo, G., Leone, M., Fodera, V. and Vetri, V. (2020) Probing ensemble polymorphism and single aggregate structural heterogeneity in insulin amyloid self-assembly. J Colloid Interface Sci 2020, 574, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Errico, S. , Fani, G., Ventura, S., Schymkowitz, J., Rousseau, F., Trovato, A., Vendruscolo, M., Bemporad, F. and Chiti, F. (2025) Structural commonalities determined by physicochemical principles in the complex polymorphism of the amyloid state of proteins. Biochem J 2025, 482, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzadfard, A. , Kunka, A., Mason, T. O., Larsen, J. A., Norrild, R. K., Dominguez, E. T., Ray, S. and Buell, A. K. (2024) Thermodynamic characterization of amyloid polymorphism by microfluidic transient incomplete separation. Chem Sci 2024, 15, 2528–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenther, E. L. , Ge, P., Trinh, H., Sawaya, M. R., Cascio, D., Boyer, D. R., Gonen, T., Zhou, Z. H. and Eisenberg, D. S. (2018) Atomic-level evidence for packing and positional amyloid polymorphism by segment from TDP-43 RRM2. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2018, 25, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heerde, T. , Schütz, D., Lin, Y. J., Münch, J., Schmidt, M. and Fändrich, M. (2023) Cryo-EM structure and polymorphic maturation of a viral transduction enhancing amyloid fibril. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 4293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakinen, A. , Adamcik, J., Wang, B., Ge, X., Mezzenga, R., Davis, T. P., Ding, F. and Ke, P. C. (2018) Nanoscale inhibition of polymorphic and ambidextrous IAPP amyloid aggregation with small molecules. Nano Res 2018, 11, 3636–3647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmer, M. , Close, W., Funk, L., Rasmussen, J., Bsoul, A., Schierhorn, A., Schmidt, M., Sigurdson, C. J., Jucker, M. and Fändrich, M. (2019) Cryo-EM structure and polymorphism of Abeta amyloid fibrils purified from Alzheimer's brain tissue. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 4760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D. and Liu, C. (2023) Molecular rules governing the structural polymorphism of amyloid fibrils in neurodegenerative diseases. Structure 2023, 31, 1335–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louros, N. , van der Kant, R., Schymkowitz, J. and Rousseau, F. (2022) StAmP-DB: a platform for structures of polymorphic amyloid fibril cores. Bioinformatics 2022, 38, 2636–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lövestam, S. , Li, D., Wagstaff, J. L., Kotecha, A., Kimanius, D., McLaughlin, S. H., Murzin, A. G., Freund, S. M. V., Goedert, M. and Scheres, S. H. W. (2024) Disease-specific tau filaments assemble via polymorphic intermediates. Nature 2024, 625, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matiiv, A. B. , Trubitsina, N. P., Matveenko, A. G., Barbitoff, Y. A., Zhouravleva, G. A. and Bondarev, S. A. (2022) Structure and Polymorphism of Amyloid and Amyloid-Like Aggregates. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2022, 87, 450–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, B. A. , Singh, V., Afrin, S., Yakubovska, A., Wang, L., Ahmed, Y., Pedretti, R., Fernandez-Ramirez, M. D. C., Singh, P., Pekala, M., Cabrera Hernandez, L. O., Kumar, S., Lemoff, A., Gonzalez-Prieto, R., Sawaya, M. R., Eisenberg, D. S., Benson, M. D. and Saelices, L. (2024) Structural polymorphism of amyloid fibrils in ATTR amyloidosis revealed by cryo-electron microscopy. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostermeier, L. , de Oliveira, G. A. P., Dzwolak, W., Silva, J. L. and Winter, R. (2021) Exploring the polymorphism, conformational dynamics and function of amyloidogenic peptides and proteins by temperature and pressure modulation. Biophys Chem 2021, 268, 106506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pansieri, J. , Halim, M. A., Vendrely, C., Dumoulin, M., Legrand, F., Sallanon, M. M., Chierici, S., Denti, S., Dagany, X., Dugourd, P., Marquette, C., Antoine, R. and Forge, V. (2018) Mass and charge distributions of amyloid fibers involved in neurodegenerative diseases: mapping heterogeneity and polymorphism. Chem Sci 2018, 9, 2791–2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K. , Stockert, F., Shenoy, J., Berbon, M., Abdul-Shukkoor, M. B., Habenstein, B., Loquet, A., Schmidt, M. and Fändrich, M. (2024) Cryo-EM observation of the amyloid key structure of polymorphic TDP-43 amyloid fibrils. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shenoy, J. , Lends, A., Berbon, M., Bilal, M., El Mammeri, N., Bertoni, M., Saad, A., Morvan, E., Grelard, A., Lecomte, S., Theillet, F. X., Buell, A. K., Kauffmann, B., Habenstein, B. and Loquet, A. (2023) Structural polymorphism of the low-complexity C-terminal domain of TDP-43 amyloid aggregates revealed by solid-state NMR. Front Mol Biosci 2023, 10, 1148302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Kant, R. , Louros, N., Schymkowitz, J. and Rousseau, F. (2022) Thermodynamic analysis of amyloid fibril structures reveals a common framework for stability in amyloid polymorphs. Structure 2022, 30, 1178–1189 e1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, M. , Xu, Y., Thacker, D., Taylor, A. I. P., Fisher, D. G., Gallardo, R. U., Radford, S. E. and Ranson, N. A. (2023) Structural evolution of fibril polymorphs during amyloid assembly. Cell 2023, 186, 5798–5811 e5726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M. , Hu, R., Chen, H., Gong, X., Zhou, F., Zhang, L. and Zheng, J. (2015) Polymorphic Associations and Structures of the Cross-Seeding of Abeta1-42 and hIAPP1-37 Polypeptides. J Chem Inf Model 2015, 55, 1628–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Close, W. , Neumann, M., Schmidt, A., Hora, M., Annamalai, K., Schmidt, M., Reif, B., Schmidt, V., Grigorieff, N. and Fändrich, M. (2018) Physical basis of amyloid fibril polymorphism. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fändrich, M. , Nyström, S., Nilsson, K. P. R., Bockmann, A., LeVine, H., 3rd and Hammarström, P. (2018) Amyloid fibril polymorphism: a challenge for molecular imaging and therapy. J Intern Med 2018, 283, 218–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cendrowska, U. , Silva, P. J., Ait-Bouziad, N., Muller, M., Guven, Z. P., Vieweg, S., Chiki, A., Radamaker, L., Kumar, S. T., Fändrich, M., Tavanti, F., Menziani, M. C., Alexander-Katz, A., Stellacci, F. and Lashuel, H. A. (2020) Unraveling the complexity of amyloid polymorphism using gold nanoparticles and cryo-EM. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117, 6866–6874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubrey, L. D. and Radford, S. E. (2025) How is the Amyloid Fold Built? Polymorphism and the Microscopic Mechanisms of Fibril Assembly. J Mol Biol 2025, 169008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, P. N. and Orban, J. (2010) Proteins that switch folds. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2010, 20, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dishman, A. F. , Tyler, R. C., Fox, J. C., Kleist, A. B., Prehoda, K. E., Babu, M. M., Peterson, F. C. and Volkman, B. F. (2021) Evolution of fold switching in a metamorphic protein. Science 2021, 371, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, L. L. (2021) Predictable fold switching by the SARS-CoV-2 protein ORF9b. Protein Sci 2021, 30, 1723–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artsimovitch, I. and Ramirez-Sarmiento, C. A. (2022) Metamorphic proteins under a computational microscope: Lessons from a fold-switching RfaH protein. Comput Struct Biotechnol J 2022, 20, 5824–5837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakravarty, D. , Schafer, J. W. and Porter, L. L. (2023) Distinguishing features of fold-switching proteins. Protein Sci 2023, 32, e4596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakravarty, D. and Porter, L. L. (2025) Fold-switching Proteins. ed.)^eds.). p. arXiv:2507. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.10839. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, A. K. and Porter, L. L. (2021) Functional and Regulatory Roles of Fold-Switching Proteins. Structure 2021, 29, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LiWang, A. , Porter, L. L. and Wang, L. P. (2021) Fold-switching proteins. Biopolymers 2021, 112, e23478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, L. L. and Looger, L. L. (2018) Extant fold-switching proteins are widespread. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018, 115, 5968–5973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retamal-Farfán, I. , González-Higueras, J., Galaz-Davison, P., Rivera, M. and Ramírez-Sarmiento, C. A. (2023) Exploring the structural acrobatics of fold-switching proteins using simplified structure-based models. Biophys Rev 2023, 15, 787–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuber, P. K. , Daviter, T., Heissmann, R., Persau, U., Schweimer, K. and Knauer, S. H. (2022) Structural and thermodynamic analyses of the beta-to-alpha transformation in RfaH reveal principles of fold-switching proteins. Elife 2022, 11, e76630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M. , Ying, J., Lopez, J. M., Huang, Y. and Clore, G. M. (2025) Unraveling structural transitions and kinetics along the fold-switching pathway of the RfaH C-terminal domain using exchange-based NMR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2025, 122, e2506441122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, N. , Sood, D., Guo, S. C., Chen, N., Antoszewski, A., Marianchuk, T., Dey, S., Xiao, Y., Hong, L., Peng, X., Baxa, M., Partch, C., Wang, L. P., Sosnick, T. R., Dinner, A. R. and LiWang, A. (2024) Temperature-dependent fold-switching mechanism of the circadian clock protein KaiB. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2024, 121, e2412327121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seifi, B. and Wallin, S. (2025) Impact of N-Terminal Domain Conformation and Domain Interactions on RfaH Fold Switching. Proteins 2025, 93, 608–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schafer, J. W. and Porter, L. L. (2023) Evolutionary selection of proteins with two folds. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 5478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lella, M. and Mahalakshmi, R. (2017) Metamorphic proteins: emergence of dual protein folds from one primary sequence. Biochemistry 2017, 56, 2971–2984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodchild, S. C. , Curmi, P. M. G. and Brown, L. J. (2011) Structural gymnastics of multifunctional metamorphic proteins. Biophys Rev 2011, 3, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadid, I. , Kirshenbaum, N., Sharon, M., Dym, O. and Tawfik, D. S. (2010) Metamorphic proteins mediate evolutionary transitions of structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010, 107, 7287–7292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appadurai, R. , Nagesh, J. and Srivastava, A. (2021) High resolution ensemble description of metamorphic and intrinsically disordered proteins using an efficient hybrid parallel tempering scheme. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhurima, K. , Nandi, B. and Sekhar, A. (2021) Metamorphic proteins: the Janus proteins of structural biology. Open Biol 2021, 11, 210012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N. , Das, M., LiWang, A. and Wang, L. P. (2020) Sequence-Based Prediction of Metamorphic Behavior in Proteins. Biophys J 2020, 119, 1380–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, M. , Chen, N., LiWang, A. and Wang, L. P. (2021) Identification and characterization of metamorphic proteins: Current and future perspectives. Biopolymers 2021, 112, e23473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, L. L. , Artsimovitch, I. and Ramírez-Sarmiento, C. A. (2024) Metamorphic proteins and how to find them. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2024, 86, 102807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerbott, K. B. , Monhemi, H., Travaglini, L., Sawicki, A., Ramamurthy, S., Slocik, J. M., Dennis, P. B., Glover, D. J., Walsh, T. R. and Knecht, M. R. (2025) Metamorphic Proteins to Achieve Conformationally Selective Material Surface Binding. Small 2025, 21, e2408141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toso, J. , Pennacchietti, V., Di Felice, M., Ventura, E. S., Toto, A. and Gianni, S. (2025) Topological determinants in protein folding dynamics: a comparative analysis of metamorphic proteins. Biol Direct 2025, 20, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LiWang, A. and Orban, J. (2025) Unveiling the cold reality of metamorphic proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2025, 122, e2422725122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dishman, A. F. and Volkman, B. F. (2022) Design and discovery of metamorphic proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2022, 74, 102380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomon, T. L. , He, Y., Sari, N., Chen, Y., Gallagher, D. T., Bryan, P. N. and Orban, J. (2023) Reversible switching between two common protein folds in a designed system using only temperature. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2023, 120, e2215418120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S. , Looger, L. L. and Porter, L. L. (2019) Inaccurate secondary structure predictions often indicate protein fold switching. Protein Sci 2019, 28, 1487–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, G. J. S. , Day, A. J., Willis, A. C., Roberts, A. N., Reid, K. B. M. and Leighton, B. (1989) Amylin and the amylin gene: structure, function and relationship to islet amyloid and to diabetes mellitus. Biochim Biophys Acta 1989, 1014, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höppener, J. W. M. , Oosterwijk, C., van Hulst, K. L., Verbeek, J. S., Capel, P. J. A., de Koning, E. J. P., Clark, A., Jansz, H. S. and Lips, C. J. M. (1994) Molecular physiology of the islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP)/amylin gene in man, rat, and transgenic mice. J Cell Biochem 1994, 55, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe-Nakayama, T. , Sahoo, B. R., Ramamoorthy, A. and Ono, K. (2020) High-Speed Atomic Force Microscopy Reveals the Structural Dynamics of the Amyloid-beta and Amylin Aggregation Pathways. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichner, T. and Radford, S. E. (2011) Understanding the complex mechanisms of beta2-microglobulin amyloid assembly. FEBS J 2011, 278, 3868–3883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heegaard, N. H. H. (2009) beta2-microglobulin: from physiology to amyloidosis. Amyloid 2009, 16, 151–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radford, S. E. , Gosal, W. S. and Platt, G. W. (2005) Towards an understanding of the structural molecular mechanism of beta(2)-microglobulin amyloid formation in vitro. Biochim Biophys Acta 2005, 1753, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shim, K. H. , Kim, D., JuKang, M., Pyun, J. M., Park, Y. H., Youn, Y. C., Park, K., Suk, K., Lee, H. W., Gomes, B. F., Zetterberg, H., An, S. S. A., Kim, S. and Alzheimers Dis All Markers (ADAM) Research Group. (2024) Subsequent correlated changes in complement component 3 and amyloid beta oligomers in the blood of patients with Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers & Dementia 2024, 20, 2731–2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T. , Dejanovic, B., Gandham, V. D., Gogineni, A., Edmonds, R., Schauer, S., Srinivasan, K., Huntley, M. A., Wang, Y. Y., Wang, T. M., Hedehus, M., Barck, K. H., Stark, M., Ngu, H., Foreman, O., Meilandt, W. J., Elstrott, J., Chang, M. C., Hansen, D. V., Carano, R. A. D., Sheng, M. and Hanson, J. E. (2019) Complement C3 Is Activated in Human AD Brain and Is Required for Neurodegeneration in Mouse Models of Amyloidosis and Tauopathy. Cell Reports 2019, 28, 2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, S. , Yamashiro, T., Yamauchi, M., Yamamoto, Y., Noguchi, M., Tomita, T., Kawakami, D., Shikata, M., Tanaka, T. and Ihara, M. (2022) Complement 3 Is a Potential Biomarker for Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy. Journal of Alzheimers Disease 2022, 89, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, R. J. , Pal, S., Achim, C. L., Sundermann, E., Moore, D. J., Soontornniyomkij, V. and Feldman, H. (2024) Alzheimer-type cerebral amyloidosis in the context of HIV infection: implications for a proposed new treatment approach. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 2024, 19, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergaglio, T. , Synhaivska, O. and Nirmalraj, P. N. (2023) Digital holo-tomographic 3D maps of COVID-19 microclots in blood to assess disease severity. bioRxiv 2009, 2023.2009.2012.557318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuducu, Y. K. , Boribong, B., Ellett, F., Hajizadeh, S., VanElzakker, M., Haas, W., Pillai, S., Fasano, A., Irimia, D. and Yonker, L. (2024) Evidence Circulating Microclots and Activated Platelets Contribute to Hyperinflammation Within Pediatric Post Acute Sequala of COVID. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2024, 209, A2247. [Google Scholar]

- Appelman, B. , Charlton, B. T., Goulding, R. P., Kerkhoff, T. J., Breedveld, E. A., Noort, W., Offringa, C., Bloemers, F. W., van Weeghel, M., Schomakers, B. V., Coelho, P., Posthuma, J. J., Aronica, E., Joost Wiersinga, W., van Vugt, M. and Wüst, R. C. I. (2024) Muscle abnormalities worsen after post-exertional malaise in long COVID. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasouli, R. , Hartl, B. and Konecky, S. D. (2025) Low-intensity ultrasound lysis of amyloid microclots in a lab-on-chip model. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2025, 13, 1604447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexandrov, A. I. , Serpionov, G. V., Kushnirov, V. V. and Ter-Avanesyan, M. D. (2016) Wild type huntingtin toxicity in yeast: Implications for the role of amyloid cross-seeding in polyQ diseases. Prion 2016, 10, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, B. G. , Prajapati, K. P. and Kar, K. (2018) Abeta(1-40) mediated aggregation of proteins and metabolites unveils the relevance of amyloid cross-seeding in amyloidogenesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2018, 501, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardin, T. , Daskalov, A., Barrouilhet, S., Granger-Farbos, A., Salin, B., Blancard, C., Kauffmann, B., Saupe, S. J. and Coustou, V. (2021) Partial Prion Cross-Seeding between Fungal and Mammalian Amyloid Signaling Motifs. mBio 2021, 12, e02782-02720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daskalov, A. , Martinez, D., Coustou, V., El Mammeri, N., Berbon, M., Andreas, L. B., Bardiaux, B., Stanek, J., Noubhani, A., Kauffmann, B., Wall, J. S., Pintacuda, G., Saupe, S. J., Habenstein, B. and Loquet, A. (2021) Structural and molecular basis of cross-seeding barriers in amyloids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2021, 118, e2014085118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X. , Zhang, X., Yan, J., Xu, H., Zhao, W., Ding, F., Huang, F. and Sun, Y. (2024) Computational Investigation of Coaggregation and Cross-Seeding between Abeta and hIAPP Underpinning the Cross-Talk in Alzheimer's Disease and Type 2 Diabetes. J Chem Inf Model 2024, 64, 5303–5316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, K. , Brender, J. R., Monde, K., Ono, A., Evans, M. L., Popovych, N., Chapman, M. R. and Ramamoorthy, A. (2013) Bacterial curli protein promotes the conversion of PAP248-286 into the amyloid SEVI: cross-seeding of dissimilar amyloid sequences. PeerJ 2013, 1, e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, M. , Ho, G., Takamatsu, Y., Wada, R., Sugama, S., Takenouchi, T., Waragai, M. and Masliah, E. (2019) Possible Role of Amyloid Cross-Seeding in Evolvability and Neurodegenerative Disease. J Parkinsons Dis 2019, 9, 793–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R. , Ren, B., Zhang, M., Chen, H., Liu, Y., Liu, L., Gong, X., Jiang, B., Ma, J. and Zheng, J. (2017) Seed-Induced Heterogeneous Cross-Seeding Self-Assembly of Human and Rat Islet Polypeptides. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 784–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koloteva-Levine, N. , Aubrey, L. D., Marchante, R., Purton, T. J., Hiscock, J. R., Tuite, M. F. and Xue, W. F. (2021) Amyloid particles facilitate surface-catalyzed cross-seeding by acting as promiscuous nanoparticles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2021, 118, e2104148118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, A. , Malmström, S. and Westermark, P. (2011) Signs of cross-seeding: aortic medin amyloid as a trigger for protein AA deposition. Amyloid 2011, 18, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nirwal, S. , Bharathi, V. and Patel, B. K. (2021) Amyloid-like aggregation of bovine serum albumin at physiological temperature induced by cross-seeding effect of HEWL amyloid aggregates. Biophys Chem 2021, 278, 106678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peim, A. , Hortschansky, P., Christopeit, T., Schroeckh, V., Richter, W. and Fandrich, M. (2006) Mutagenic exploration of the cross-seeding and fibrillation propensity of Alzheimer's beta-amyloid peptide variants. Protein Sci 2006, 15, 1801–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, R. , Luo, Y., Wei, G., Nussinov, R. and Ma, B. (2015) Aβ “Stretching-and-Packing” Cross-Seeding Mechanism Can TriggerTau Protein Aggregation. J Phys Chem Lett 2015, 6, 3276–3282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, B. , Hu, R., Zhang, M., Liu, Y., Xu, L., Jiang, B., Ma, J., Ma, B., Nussinov, R. and Zheng, J. (2018) Experimental and Computational Protocols for Studies of Cross-Seeding Amyloid Assemblies. Methods Mol Biol 2018, 1777, 429–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y. , Zhang, D., Zhang, Y., Liu, Y., Miller, Y., Gong, K. and Zheng, J. (2022) Cross-seeding between Abeta and SEVI indicates a pathogenic link and gender difference between alzheimer diseases and AIDS. Commun Biol 2022, 5, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y. , Zhang, D., Liu, Y., Zhang, Y., Zhou, Y., Chang, Y., Zheng, B., Xu, A. and Zheng, J. (2022) A new strategy to reconcile amyloid cross-seeding and amyloid prevention in a binary system of alpha-synuclein fragmental peptide and hIAPP. Protein Sci 2022, 31, 485–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y. , Zhang, D. and Zheng, J. (2023) Repurposing Antimicrobial Protegrin-1 as a Dual-Function Amyloid Inhibitor via Cross-seeding. ACS Chem Neurosci 2023, 14, 3143–3155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y. , Zhang, D., Chang, Y. and Zheng, J. (2023) Atrial Natriuretic Peptide Associated with Cardiovascular Diseases Inhibits Amyloid-beta Aggregation via Cross-Seeding. ACS Chem Neurosci 2023, 14, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaneyck, J. , Segers-Nolten, I., Broersen, K. and Claessens, M. M. A. E. (2021) Cross-seeding of alpha-synuclein aggregation by amyloid fibrils of food proteins. J Biol Chem 2021, 296, 100358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, N. , Matsuzaki, K. and Yanagisawa, K. (2005) Cross-seeding of wild-type and hereditary variant-type amyloid beta-proteins in the presence of gangliosides. J Neurochem 2005, 95, 1167–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuzu, K. , Yamamoto, N., Noji, M., So, M., Goto, Y., Iwasaki, T., Tsubaki, M. and Chatani, E. (2021) Multistep Changes in Amyloid Structure Induced by Cross-Seeding on a Rugged Energy Landscape. Biophys J 2021, 120, 284–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M. , Hu, R., Liang, G., Chang, Y., Sun, Y., Peng, Z. and Zheng, J. (2014) Structural and energetic insight into the cross-seeding amyloid assemblies of human IAPP and rat IAPP. J Phys Chem B 2014, 118, 7026–7036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M. , Hu, R., Ren, B., Chen, H., Jiang, B., Ma, J. and Zheng, J. (2017) Molecular Understanding of Abeta-hIAPP Cross-Seeding Assemblies on Lipid Membranes. ACS Chem Neurosci 2017, 8, 524–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y. , Zhang, M., Liu, Y., Zhang, D., Tang, Y., Ren, B. and Zheng, J. (2021) Dual amyloid cross-seeding reveals steric zipper-facilitated fibrillization and pathological links between protein misfolding diseases. J Mater Chem B 2021, 9, 3300–3316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y. , Smith, D., Leong, B. J., Brannstrom, K., Almqvist, F. and Chapman, M. R. (2012) Promiscuous cross-seeding between bacterial amyloids promotes interspecies biofilms. J Biol Chem 2012, 287, 35092–35103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burdukiewicz, M. , Rafacz, D., Barbach, A., Hubicka, K., Bąkaaronla, L., Lassota, A., Stecko, J., Szymańska, N., Wojciechowski, J. W., Kozakiewicz, D., Szulc, N., Chilimoniuk, J., Jęśkowiak, I., Gąsior-Glogowska, M. and Kotulska, M. (2023) AmyloGraph: a comprehensive database of amyloid-amyloid interactions. Nucleic Acids Res 2023, 51, D352–D357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, S. , Humphreys, C., Fraser, E., Brancale, A., Bochtler, M. and Dale, T. C. (2011) Amyloid-associated nucleic acid hybridisation. PLoS One 2011, 6, e19125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Domizio, J. , Zhang, R., Stagg, L. J., Gagea, M., Zhuo, M., Ladbury, J. E. and Cao, W. (2012) Binding with nucleic acids or glycosaminoglycans converts soluble protein oligomers to amyloid. J Biol Chem 2012, 287, 736–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Domizio, J. , Dorta-Estremera, S., Gagea, M., Ganguly, D., Meller, S., Li, P., Zhao, B., Tan, F. K., Bi, L., Gilliet, M. and Cao, W. (2012) Nucleic acid-containing amyloid fibrils potently induce type I interferon and stimulate systemic autoimmunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012, 109, 14550–14555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rha, A. K. , Das, D., Taran, O., Ke, Y., Mehta, A. K. and Lynn, D. G. (2020) Electrostatic Complementarity Drives Amyloid/Nucleic Acid Co-Assembly. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2020, 59, 358–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretorius, E. , Thierry, A., Sanchez, C., Ha, T., Pastor, B., Mirandola, A., Pisareva, E., Prevostel, C., Laubscher, G., Usher, T., Venter, C., Turner, S., Waters, M. and Kell, D. B. (2024) Circulating microclots are structurally associated with Neutrophil Extracellular Traps and their amounts are strongly elevated in long COVID patients. Res Square 4666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukreja, R. and Latham, M. P. (2025) Molecular recognition and structural plasticity in amyloid-nucleic acid complexes. J Struct Biol 2025, 217, 108233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguzzi, A. and Calella, A. M. (2009) Prions: protein aggregation and infectious diseases. Physiol Rev 2009, 89, 1105–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, A. , Schmidt, M., Rennegarbe, M., Haupt, C., Liberta, F., Stecher, S., Puscalau-Girtu, I., Biedermann, A. and Fändrich, M. (2021) AA amyloid fibrils from diseased tissue are structurally different from in vitro formed SAA fibrils. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambeth, T. R. and Julian, R. R. (2021) Proteolysis of amyloid β by lysosomal enzymes as a function of fibril morphology. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 31520–31527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schönfelder, J. , Pfeiffer, P. B., Pradhan, T., Bijzet, J., Hazenberg, B. P. C., Schönland, S. O., Hegenbart, U., Reif, B., Haupt, C. and Fändrich, M. (2021) Protease resistance of ex vivo amyloid fibrils implies the proteolytic selection of disease-associated fibril morphologies. Amyloid 2021, 28, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stepanenko, O. V. , Sulatsky, M. I., Mikhailova, E. V., Stepanenko, O. V., Kuznetsova, I. M., Turoverov, K. K. and Sulatskaya, A. I. (2021) Trypsin induced degradation of amyloid fibrils. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 4828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).