Submitted:

13 August 2025

Posted:

14 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- How do professionals navigate ethical ambiguities when their work crosses traditional professional boundaries in digital contexts?

- What role do emotions play in identity construction when professionals face ethical dilemmas in platform-mediated work?

- How do different identity orientation strategies influence ethical decision-making under conditions of ambiguity?

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. The Changing Landscape of Professional Work

- Algorithmic mediation: Work processes increasingly delegated to or mediated by algorithms, raising questions about professional autonomy and accountability

- Platform governance tensions: Contradictory pressures from multiple stakeholders with competing interests and values

- Scale and velocity: Decision-making at unprecedented scale and speed, compressing the reflective space traditionally available for ethical deliberation

2.2. Ethical Gray Zones in Digital Work

- Jurisdictional ambiguity: Unclear which professional domain’s ethical standards should apply

- Consequential ambiguity: Difficulty predicting the downstream effects of decisions

- Value plurality: Multiple legitimate ethical frameworks suggesting different courses of action

2.3. Professional Identity and Identity Work

2.3.1. Ethical Identity Work and Related Constructs

2.4. Emotions and Ethical Decision-Making

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

- Qualitative exploration: In-depth interviews to identify identity orientation strategies and ethical challenges

- Experience sampling: Real-time capture of emotional responses to ethical dilemmas

- Experimental validation: Vignette studies testing relationships between identity salience, emotional responses, and ethical judgments

3.2. Sample and Data Collection

3.2.1. Phase 1: Qualitative Interviews

- AI ethics specialists (n=18)

- Content moderators (n=16)

- Platform governance professionals (n=13)

3.2.2. Phase 2: Experience Sampling

- Current work activity

- Ethical challenges encountered

- Emotional responses (using validated emotion measures from Mauss & Robinson, 2009)

- Decision-making approaches

- Identity salience (adapted from Aquino & Reed, 2002)

3.2.3. Phase 3: Experimental Validation

3.3. Data Analysis

3.3.1. Qualitative Analysis

- Initial template development: Based on theoretical frameworks and preliminary reading of transcripts

- Coding and template refinement: Iterative coding and revision of the template as new themes emerged

- Final coding: Application of the finalized template to all transcripts

3.3.2. Quantitative Analysis

3.4. Validity and Reliability Considerations

- Triangulation: Multiple data sources and methods to corroborate findings

- Member checking: Preliminary findings were shared with 12 participants for feedback

- Reflexivity: The research team maintained reflexive journals documenting analytical decisions

- Extended engagement: Ongoing relationships with key informants to deepen understanding

- Negative case analysis: Active searching for disconfirming evidence

4. Results

4.1. Identity Orientation Strategies in Boundary-Spanning Digital Work

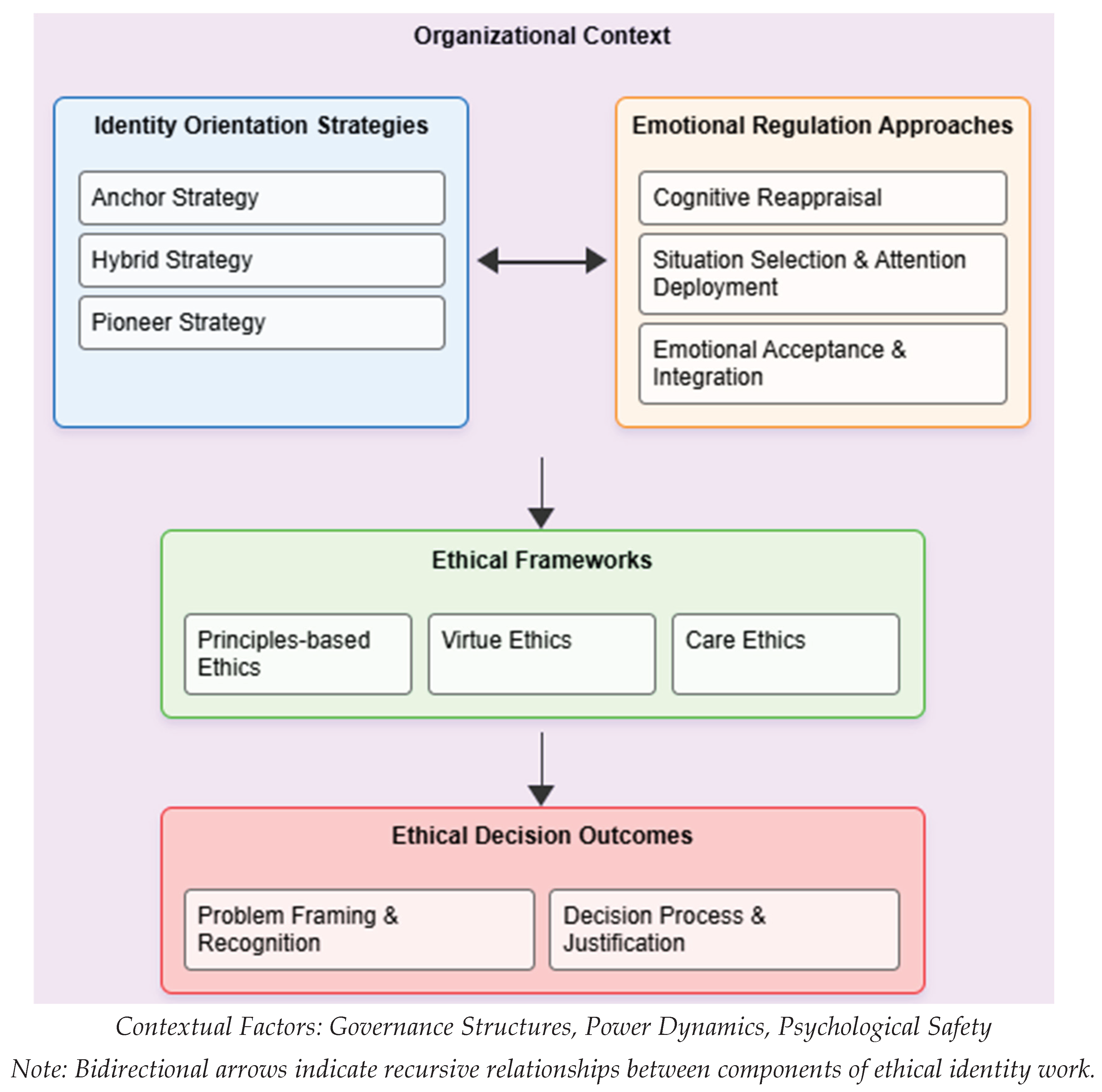

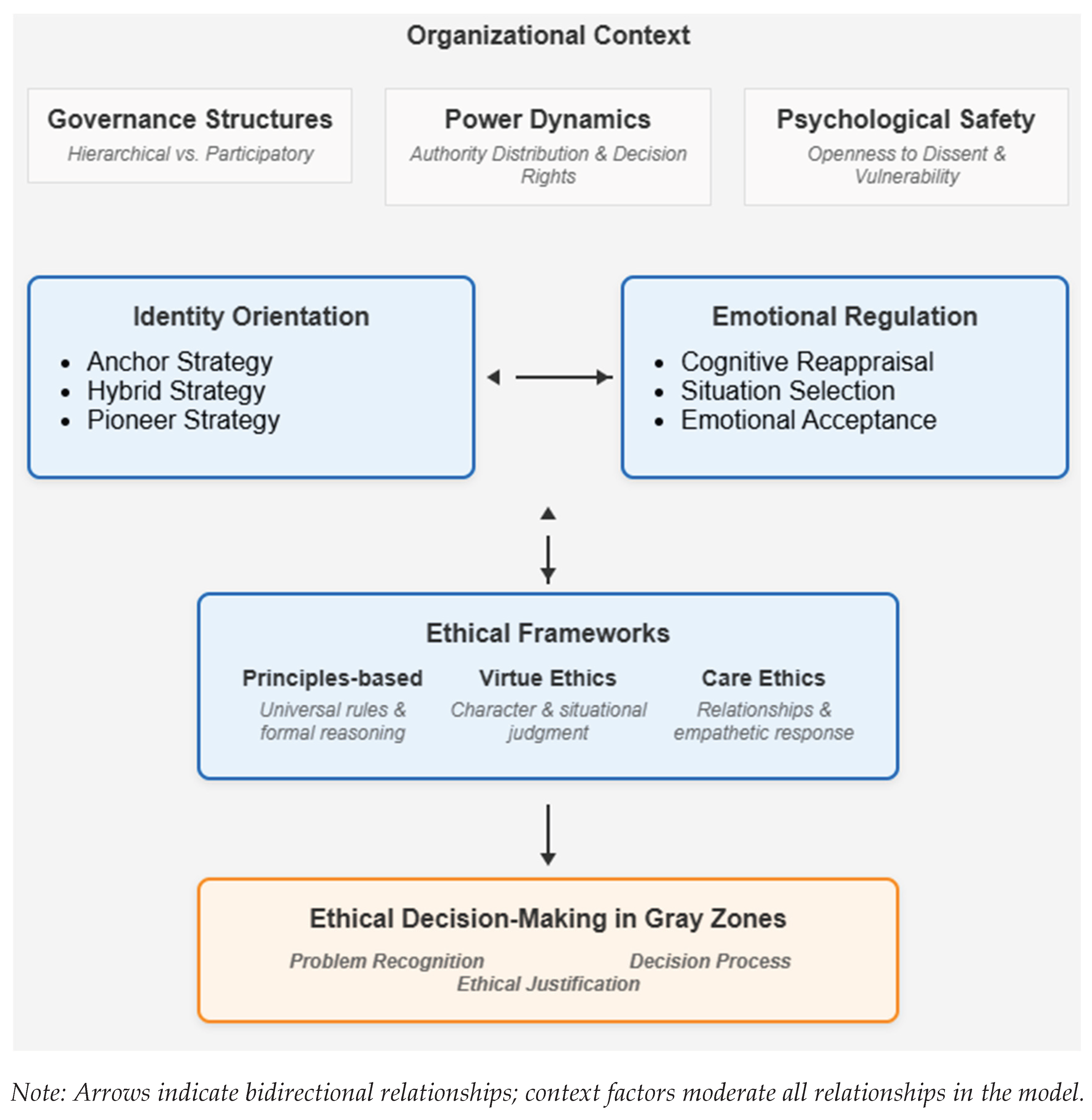

4.2. The Process Model of Ethical Identity Work

“After handling that content moderation case involving self-harm, I realized I couldn’t maintain the emotional distance my journalism training had taught me. It fundamentally changed how I see myself as a professional—I’ve had to develop a new approach that integrates more of the emotional dimension. ”(P16, content moderator with journalism background)

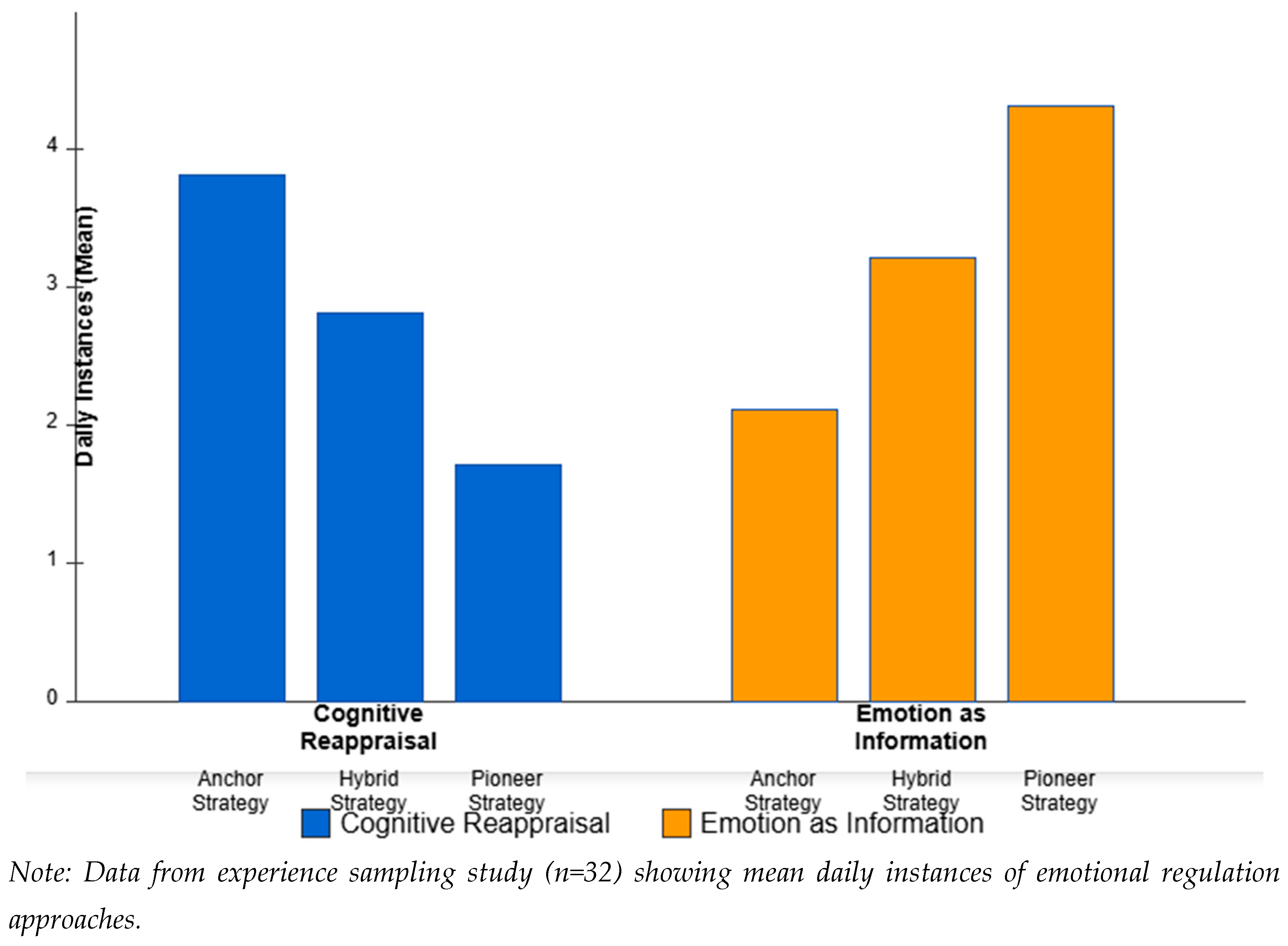

4.2.1. Identity Orientation and Emotional Regulation

“When I feel disturbed by a content decision, I consciously reframe it using my journalism training. I ask: What serves the public interest? What promotes transparent discourse? That helps me manage the emotional impact while staying true to my professional values.”(P12, content policy specialist with journalism background)

“My emotional response is data. If I feel uncomfortable with an algorithmic decision, that discomfort is telling me something important about potential harms or unexamined assumptions. I’ve learned to lean into that feeling rather than dismiss it.”(P4, AI ethics specialist)

4.2.2. Identity Orientation and Ethical Frameworks

4.2.3. The Role of Organizational Context

- Governance structures: Organizations with more participatory governance approaches supported greater integration of emotional information into ethical decision-making (β = .34, p < .01, 95% CI [.16, .52])

- Power dynamics: Hierarchical structures amplified anchoring identity strategies and principles-based ethics, while flatter structures facilitated pioneering strategies (β = .29, p < .01, 95% CI [.11, .47])

- Psychological safety: Higher psychological safety correlated with more diverse emotional regulation strategies and ethical approaches (β = .43, p < .001, 95% CI [.26, .60])

“The official stance is that we should apply the community standards consistently with minimal interpretation. But in reality, many of us are developing more nuanced approaches that consider context and impact. We just don’t always document that part of our process.”(P8, content moderator)

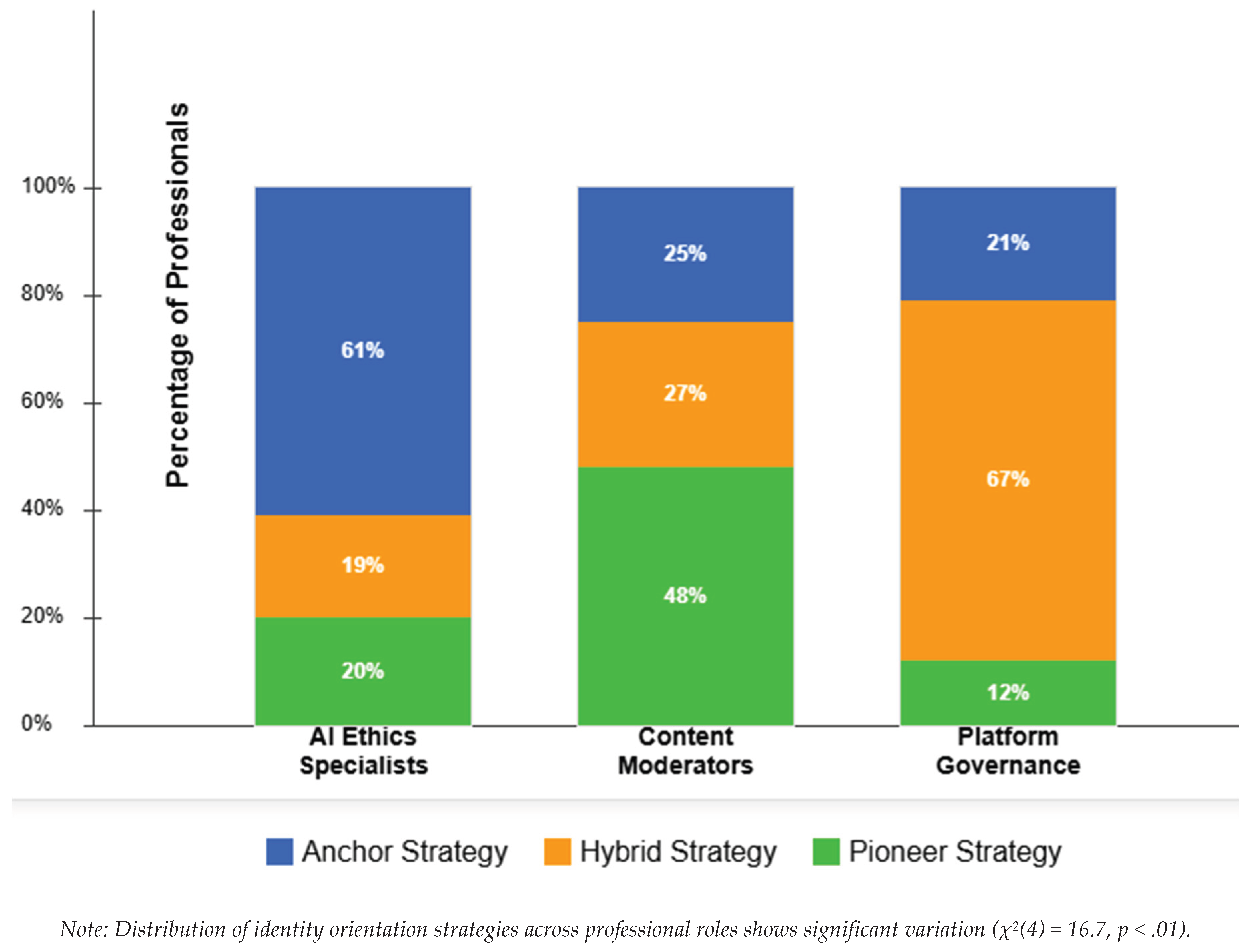

4.3. Comparative Analysis Across Professional Roles

| Professional Role | Predominant Identity Strategy | Distinctive Ethical Challenges | Characteristic Identity-Emotion Patterns |

|---|---|---|---|

| AI Ethics Specialists | Anchoring (61%) | Long-term consequential ambiguity; technical-social translation | Greater cognitive reappraisal; emphasis on epistemic emotions (curiosity, surprise) |

| Content Moderators | Pioneering (48%) | Exposure to harmful content; high-velocity decisions; scale challenges | Higher emotional intensity; more acceptance strategies; greater compassion fatigue |

| Platform Governance Professionals | Hybridizing (67%) | Stakeholder management; value conflicts across constituencies | Complex emotion differentiation; more situation selection; emphasis on social emotions |

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Boundary Conditions and Limitations

5.3. Practical Implications

5.3.1. Developing Identity Resources for Boundary-Spanning Professionals

- Professional community building: Creating spaces for identity negotiation and collective sense-making among professionals facing similar challenges

- Identity narratives: Developing and sharing narratives that help professionals make meaning of their work and its ethical dimensions

- Role clarity within ambiguity: Defining core professional commitments and values while acknowledging zones of legitimate ethical discretion

“The company wants consistency and scalability, but ethical work requires individual judgment and sometimes creative approaches. There’s a fundamental tension there.”(P23, AI ethics specialist)

5.3.2. Integrating Emotions into Ethical Infrastructure

- Emotional impact assessments: Systematically considering how technologies affect emotional wellbeing alongside other impacts

- Reflective spaces: Creating temporal and physical spaces for emotional processing and ethical reflection

- Emotion-sensitive ethics training: Developing approaches to ethics education that integrate emotional and analytical capacities

“We need to move beyond the idea that being professional means being unemotional. In ethical work, emotions provide crucial signals about values and impacts.”(P37, platform governance professional)

5.3.3. Governance Mechanisms for Ethical Gray Zones

- Ethical sense-making forums: Structured processes for collective deliberation about novel ethical challenges

- Principled flexibility: Clear ethical principles combined with discretionary space for contextual judgment

- Ethics mentorship: Pairing less experienced professionals with ethics mentors who can guide identity development and ethical reasoning

5.4. Future Research Directions

- Longitudinal identity development: How do identity orientation strategies evolve over professional careers in boundary-spanning digital work? Longitudinal studies could examine identity trajectories and critical transition points, identifying factors that trigger shifts between strategies.

- Cross-cultural comparisons: How do cultural contexts shape identity work and emotional regulation in ethical gray zones? Comparative studies across different national and cultural contexts could illuminate how cultural norms around emotions and professional identity influence ethical identity work.

- Technology-mediated identity work: How do digital tools themselves shape identity construction and ethical decision-making? Research could examine how technologies both enable and constrain different identity orientation strategies, particularly as AI systems increasingly augment professional judgment.

- Identity work and ethical outcomes: What is the relationship between different identity orientation strategies and ethical outcomes? Studies could explore whether certain approaches lead to more ethically robust decisions in different contexts, perhaps using expert evaluation or stakeholder impact assessments to measure ethical quality.

- Collective identity processes: How do teams and communities of practice develop shared identity resources for navigating ethical gray zones? Research could examine collective identity work in boundary-spanning digital teams, exploring how shared identity resources emerge and how they influence team-level ethical approaches.

- Resistance and power dynamics: How do professionals navigate organizational constraints that conflict with their ethical identity work? Research could explore the political dimensions of ethical identity work, examining how professionals resist or reshape organizational expectations when these conflict with their ethical self-concepts.

6. Conclusions

Appendix A. Interview Protocol

- Semi-Structured Interview Guide: Identity Work in Ethical Gray Zones

-

Introduction

- Thank participant for their time

- Review informed consent procedures

- Explain purpose of research and interview structure

- Ask permission to record

-

Professional Background and Identity

- Could you tell me about your current professional role and responsibilities?

- How did you come to work in this field? What is your professional background?

- How would you describe yourself professionally? What kind of professional do you consider yourself to be?

- Has your sense of professional identity changed since beginning work in this role? If so, how?

- To what extent do you draw on previous professional experiences or training in your current role?

- When people ask what you do, how do you describe your work?

-

Ethical Challenges and Gray Zones

- 7.

- What are the most challenging ethical situations you face in your work?

- 8.

-

Could you describe a specific ethical dilemma you’ve encountered recently?

- What made this situation challenging?

- How did you approach making a decision?

- What resources, frameworks, or guidelines did you draw upon?

- 9.

- In situations where there isn’t a clear precedent or guideline, how do you determine what to do?

- 10.

- To what extent do existing professional ethical frameworks or codes apply to your work? Where do they fall short?

-

Emotions and Decision-Making

- 11.

- What emotions typically arise when you face ethically challenging situations?

- 12.

- How do you deal with these emotions?

- 13.

- What role do you think emotions play in your ethical decision-making process?

- 14.

- How do you distinguish between emotional responses that are helpful versus those that might interfere with good judgment?

- 15.

- Could you describe a situation where your emotional response provided important insight into an ethical issue?

-

Identity and Ethics Integration

- 16.

- How does your sense of who you are as a professional influence how you approach ethical dilemmas?

- 17.

- To what extent do you feel your professional values align with the ethical demands of your role?

- 18.

- When facing an ethical dilemma, what aspects of your professional identity become most salient or important?

- 19.

- How do you maintain a coherent sense of professional self while navigating ethically ambiguous situations?

-

Organizational Context

- 20.

- How does your organization support (or hinder) your ethical decision-making?

- 21.

- What formal or informal resources exist to help you navigate ethical challenges?

- 22.

- How do power dynamics or authority structures influence ethical decision-making in your context?

- 23.

- To what extent can you openly discuss ethical concerns or emotional responses with colleagues?

-

Closing Questions

- 24.

- How has your approach to ethical dilemmas evolved over time in this role?

- 25.

- What advice would you give to someone new to your field about navigating ethical challenges?

- 26.

- Is there anything I haven’t asked about that you think is important for understanding how professionals in your position navigate ethical gray zones?

-

Demographics and Follow-up

- Collect demographic information (age range, gender, years of experience, educational background)

- Ask about willingness to participate in experience sampling phase

- Thank participant and explain next steps

Appendix B. Experience Sampling Protocol

- Experience Sampling Methodology: Identity, Emotions, and Ethical Decision-Making

- Participant Instructions

- Sample Survey Items

-

Current Activity

- What are you currently working on? (open text)

- How long have you been engaged in this activity? (dropdown: < 15 min, 15-30 min, 30-60 min, > 60 min)

- Does this activity involve making decisions with ethical dimensions? (5-point scale: Not at all - Very much)

-

Ethical Challenge Assessment (if rated 3 or higher on ethical dimensions)

- Briefly describe the ethical aspect of this situation (open text)

- How ambiguous is the “right” course of action in this situation? (5-point scale)

-

What type of ethical challenge does this represent? (select all that apply)

- ○

- Unclear which standards/rules apply

- ○

- Difficult to predict consequences

- ○

- Multiple competing values at stake

- ○

- Other (please specify)

-

Emotional Response

-

To what extent are you currently experiencing each of the following emotions? (7-point scale for each)

- ○

- Anxiety

- ○

- Confidence

- ○

- Frustration

- ○

- Compassion

- ○

- Moral distress

- ○

- Interest/curiosity

- ○

- Satisfaction

- ○

- Other (please specify)

- How intensely are you experiencing emotions overall? (7-point scale)

- To what extent are you using your emotional responses as information for decision-making? (7-point scale)

- To what extent are you trying to set aside emotions to make an objective decision? (7-point scale)

-

-

Identity Salience

-

In this moment, how strongly do you identify with each of the following professional identities? (7-point scale for each)

- ○

- Technical professional (e.g., engineer, data scientist)

- ○

- Ethical guardian/advocate

- ○

- Organizational representative

- ○

- Policy professional

- ○

- Industry expert

- ○

- Other (specified in enrollment)

- How central is your professional identity to how you’re approaching this situation? (7-point scale)

- Which aspect of your background or training feels most relevant right now? (open text)

-

-

Decision Approach (if ethical decision indicated)

-

How are you approaching this decision? (select all that apply)

- ○

- Applying established rules or principles

- ○

- Considering consequences for affected parties

- ○

- Consulting with colleagues

- ○

- Drawing on past precedent

- ○

- Relying on professional intuition

- ○

- Other (please specify)

- Whose perspectives are you considering in this decision? (open text)

- How confident do you feel in your approach to this situation? (7-point scale)

-

-

Technical Implementation Notes

- The mobile application will be programmed to send notifications at random intervals within participants’ specified working hours

- Participants will have the option to temporarily silence notifications during meetings or sensitive work periods

- All responses will be encrypted and transmitted securely to the research database

- Participants will have access to a “pause” function if they need to take a break from the study

Appendix C. Experimental Vignette Materials

- Vignette Study: Identity Orientation and Ethical Decision-Making

- Overview

- Part 1: Identity Orientation Priming

- Anchoring Identity Prime:

- Hybridizing Identity Prime:

- Pioneering Identity Prime:

- Manipulation Check:

- I primarily draw on one established professional tradition in my work

- I synthesize methods and values from multiple professional backgrounds

- I am creating new professional approaches that don’t fit established categories

- My professional identity is firmly rooted in an established field

- My professional identity involves bridging multiple domains

- My professional identity involves pioneering new territory

- Part 2: Ethical Vignettes

- Measures Following Each Vignette:

-

Emotional Response:

- Rate the intensity of your emotional response to this situation (7-point scale)

-

Indicate the extent to which you feel each of the following emotions (7-point scale for each):

- ○

- Concern

- ○

- Confidence

- ○

- Frustration

- ○

- Compassion

- ○

- Moral distress

- ○

- Interest/curiosity

- ○

- Certainty

- ○

- Other (please specify)

-

Emotional Regulation:

-

How would you approach your emotions in this situation? (7-point agreement scales)

- ○

- I would try to reinterpret my emotional reactions through professional frameworks

- ○

- I would focus on aspects of the situation that align with my professional values

- ○

- I would accept my emotional responses as valuable information

- ○

- I would set aside my emotions to make an objective decision

- ○

- I would use my emotional responses to identify potential harms

-

-

Decision Approach:

-

How would you approach making a decision in this situation? (select all that apply)

- ○

- Apply universal ethical principles or rules

- ○

- Consider consequences for all affected stakeholders

- ○

- Draw on professional virtues and character

- ○

- Focus on relationships and care for affected parties

- ○

- Follow established organizational procedures

- ○

- Other (please specify)

-

What factors would be most important in your decision? (rank order)

- ○

- Compliance with policies and principles

- ○

- Impact on affected individuals and communities

- ○

- Professional integrity and character

- ○

- Organizational implications

- ○

- Technical considerations

- ○

- Precedent for future cases

-

-

Decision Outcome:

- What would you decide in this situation? (scenario-specific options)

- How confident are you in this decision? (7-point scale)

- How would you justify your decision to others? (open text)

- Debriefing:

References

- Abbott, A. The system of professions: An essay on the division of expert labor. University of Chicago Press. 1988.

- Aquino, K.; Reed, A. The self-importance of moral identity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2002, 83, 1423–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashforth, B. E.; Kreiner, G. E.; Fugate, M. All in a day’s work: Boundaries and micro role transitions. Academy of Management Review, 2000, 25, 472–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B. E.; Schinoff, B. S. Identity under construction: How individuals come to define themselves in organizations. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 2016, 3, 111–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, L. F. How emotions are made: The secret life of the brain. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger, N., & Laurenceau, J. P. Intensive longitudinal methods: An introduction to diary and experience sampling research. Guilford Press. 2013.

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (3rd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2017). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Eisenhardt, K. M.; Furr, N. R.; Bingham, C. B. CROSSROADS—Microfoundations of performance: Balancing efficiency and flexibility in dynamic environments. Organization Science, 2010, 21, 1263–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraj, S.; von Krogh, G.; Monteiro, E.; Lakhani, K. R. Online community as space for knowledge flows. Information Systems Research, 2018, 29, 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Grandey, A. A.; Gabriel, A. S. Emotional labor at a crossroads: Where do we go from here? Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 2015, 2, 323–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, J. D. Beyond point-and-shoot morality: Why cognitive (neuro)science matters for ethics. Ethics, 2014, 124, 695–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidt, J. The emotional dog and its rational tail: A social intuitionist approach to moral judgment. Psychological Review, 2001, 108, 814–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haidt, J. (2012). The righteous mind: Why good people are divided by politics and religion. Vintage.

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

- Ibarra, H. Provisional selves: Experimenting with image and identity in professional adaptation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 1999, 44, 764–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Kellogg, K. C.; Valentine, M. A.; Christin, A. Algorithms at work: The new contested terrain of control. Academy of Management Annals, 2020, 14, 366–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, N. (2004). Using templates in the thematic analysis of text. In C. Cassell & G. Symon (Eds.), Essential guide to qualitative methods in organizational research (pp. 257-270). Sage Publications.

- LeBoeuf, R. A.; Shafir, E.; Bayuk, J. B. The conflicting choices of alternating selves. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 2010, 111, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, K. Ethical implications and accountability of algorithms. Journal of Business Ethics, 2019, 160, 835–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, J. A. (2013). Qualitative research design: An interactive approach (3rd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Mauss, I. B.; Robinson, M. D. Measures of emotion: A review. Cognition and Emotion, 2009, 23, 209–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesquita, B., De Leersnyder, J., & Albert, D. (2014). The cultural regulation of emotions. In J. J. Gross (Ed.), Handbook of emotion regulation (2nd ed., pp. 284-301). Guilford Press.

- Metcalf, J.; Moss, E.; boyd, d. Owning ethics: Corporate logics, Silicon Valley, and the institutionalization of ethics. Social Research: An International Quarterly, 2019, 86, 449–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nippert-Eng, C. E. (1996). Home and work: Negotiating boundaries through everyday life. University of Chicago Press.

- Nissenbaum, H. A contextual approach to privacy online. Daedalus, 2011, 140, 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petriglieri, G.; Ashford, S. J.; Wrzesniewski, A. Agony and ecstasy in the gig economy: Cultivating holding environments for precarious and personalized work identities. Administrative Science Quarterly, 2018, 64, 124–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudenbush, S. W., & Bryk, A. S. (2002). Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Tenbrunsel, A. E.; Smith-Crowe, K. Ethical decision making: Where we’ve been and where we’re going. Academy of Management Annals, 2008, 2, 545–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, P. H., Ocasio, W., & Lounsbury, M. (2012). The institutional logics perspective: A new approach to culture, structure, and process. Oxford University Press.

| Higher-Order Theme | Sub-themes | Example Codes |

|---|---|---|

| Identity Orientation Strategies | Anchoring Strategy | Professional heritage; Extension of traditional role; Reference to established profession |

| Hybridizing Strategy | Integration; Synthesis; Multiple traditions; Selective borrowing | |

| Pioneering Strategy | Novel archetype; Creating new standards; Defining new territory | |

| Emotional Regulation | Cognitive Reappraisal | Reframing; Professional distance; Analytical reinterpretation |

| Situation Selection | Selective focus; Attention direction; Choosing engagement points | |

| Emotional Acceptance | Emotions as information; Emotional integration; Authentic response | |

| Ethical Frameworks | Principles-based | Universal rules; Procedural fairness; Consistent standards |

| Virtue Ethics | Character; Professional judgment; Balance and wisdom | |

| Care Ethics | Relationship focus; Harm prevention; Contextual understanding | |

| Contextual Factors | Governance Structures | Decision authority; Review processes; Accountability mechanisms |

| Power Dynamics | Hierarchical constraints; Advocacy resources; Voice opportunities | |

| Psychological Safety | Emotional expression norms; Error tolerance; Vulnerability acceptance |

| Strategy | Description | Prevalence | Illustrative Quote |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anchoring Strategy | Maintaining strong identification with an established profession while extending its boundaries to encompass new ethical challenges | 38% (most common among AI ethics specialists with technical backgrounds) | “At heart, I’m still an engineer. I approach ethical questions with the same analytical mindset, just applied to a different domain of problems.” (P7, AI ethics specialist) |

| Hybridizing Strategy | Selectively integrating elements from multiple professional traditions to create a coherent but novel professional identity | 42% (most common among platform governance professionals) | “I draw from my legal training for procedural thinking, my policy background for stakeholder analysis, and my technical knowledge for implementation constraints. I’m not any one of those things—I’m a new synthesis.” (P31, platform governance professional) |

| Pioneering Strategy | Embracing the lack of established templates as an opportunity to develop entirely new professional archetypes | 20% (most common among content moderators and junior professionals) | “There’s no roadmap for this role. I’m creating a new type of professional identity that doesn’t fit existing categories. That’s challenging but also liberating.” (P22, content moderator) |

| Identity Strategy | Primary Emotional Regulation Approach | Characteristic Emotional Patterns | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anchoring | Cognitive reappraisal (reinterpreting emotional responses through established professional lenses) | Lower emotional intensity but potential emotional suppression | Stronger reappraisal tendencies in vignette responses (β = .42, p < .01, 95% CI [.24, .60]) |

| Hybridizing | Situation selection and attention deployment (choosing and focusing on aspects of situations that align with integrated identity elements) | Moderate emotional intensity with selective engagement | Greater emotional flexibility in response to ambiguous situations (β = .37, p < .01, 95% CI [.18, .56]) |

| Pioneering | Emotional acceptance and integration (treating emotional responses as valid data points) | Higher reported emotional intensity with greater integration into decision processes | Higher scores on measures of emotional acceptance (β = .39, p < .01, 95% CI [.21, .57]) |

| Identity Strategy | Primary Ethical Framework | Characteristic Approach to Ethical Dilemmas | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anchoring | Principles-based ethics (emphasizing universal ethical principles and formal reasoning processes) | Seeking to establish clear standards and procedures; preference for rule-based approaches | Stronger ratings for principle-based justifications in vignettes (β = .46, p < .001, 95% CI [.29, .63]) |

| Hybridizing | Virtue ethics (focusing on professional character and virtues that guide situational judgment) | Developing and applying context-sensitive professional judgment; emphasis on balance | Higher ratings for character-based considerations in ethical reasoning (β = .38, p < .01, 95% CI [.19, .57]) |

| Pioneering | Care ethics (prioritizing relationships, context, and empathetic response) | Attending to impacts on affected communities; emphasis on contextual understanding | Greater weight on relationship and harm considerations in ethical decisions (β = .41, p < .001, 95% CI [.23, .59]) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).