Submitted:

13 August 2025

Posted:

14 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

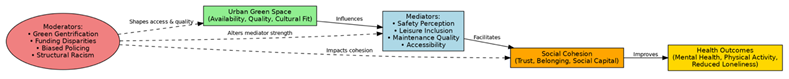

Problem Statement and Context

Gap Analysis

Objectives and Review Question(s)

- Population (P): Communities characterized by racial and ethnic variety, including traditionally disadvantaged populations in urban areas.

- Exposure (E): The availability and use of urban green places including parks, gardens, and forests.

- Comparison (C): Green areas of poor quality, safety, or cultural equality, or those that are limited or unequally accessible.

- Outcome (O): The level of community cohesion (e.g., trust, belonging, social capital) and the associated public health outcomes (e.g., mental health, physical activity, loneliness reduction).

Methods

Protocol Registration

Eligibility Criteria

Search Strategy

Data Extraction

- Demographic data (community classification, population characteristics)

- Accessibility of Green spaces

- Qualitative themes, quantitative metrics, and social cohesiveness indicators

- Health outcomes (psychological, physiological, and behavioral)

Quality Assessment

Data Synthesis and Statistical Methodology

Results

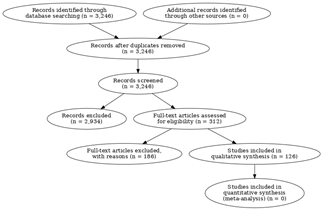

Study Selection

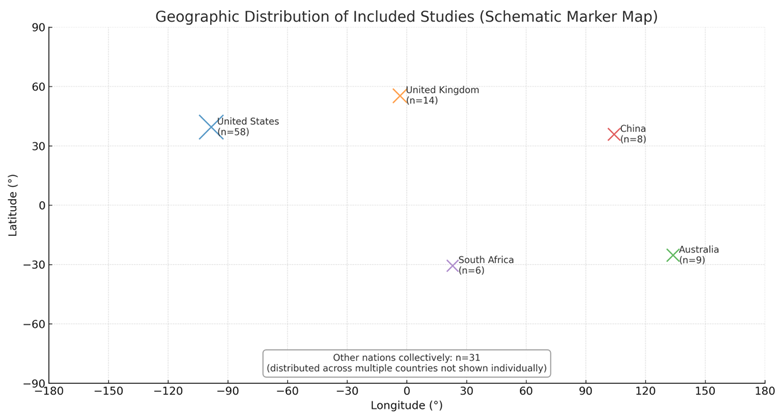

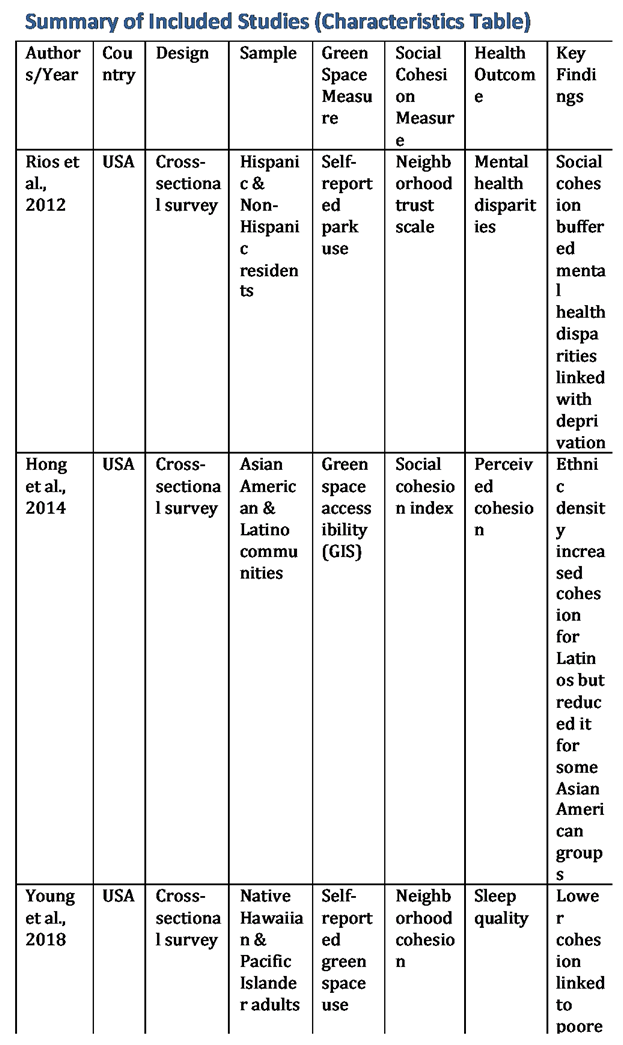

Study Characteristics

|

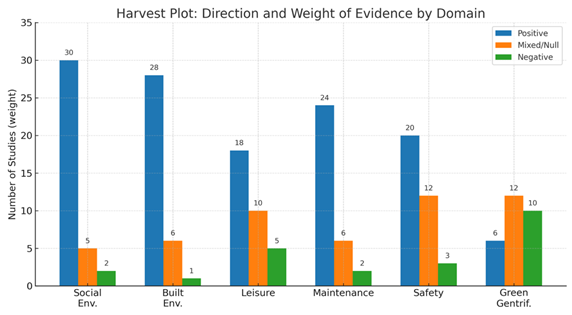

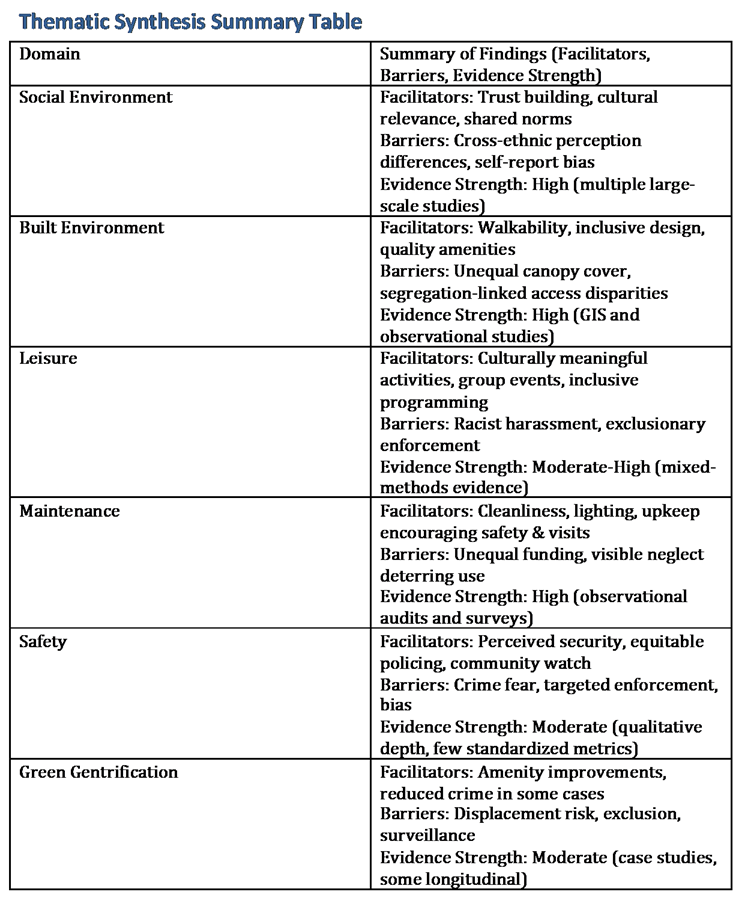

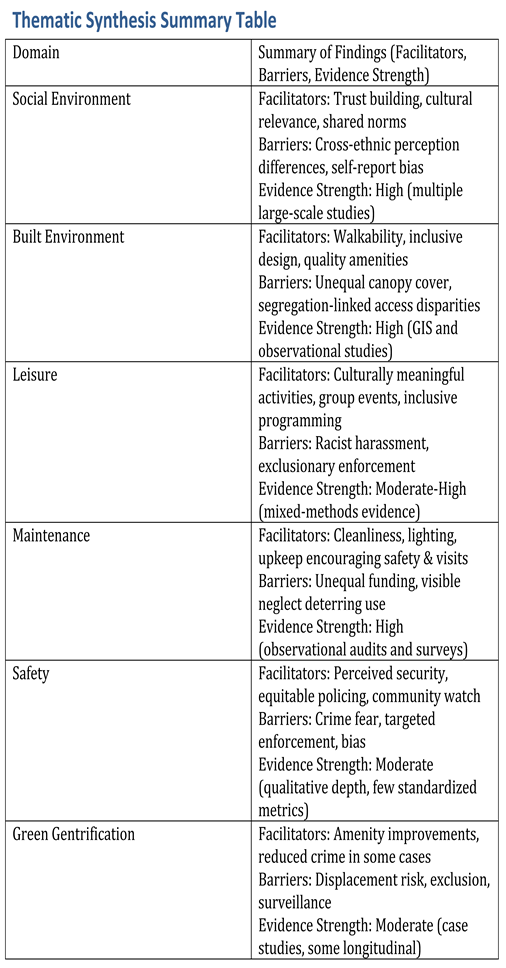

Synthesis of Findings

Agreements and Disagreements

- Agreements: In numerous geographic locations, green spaces that are culturally inclusive, well-maintained, secure, and well-designed are linked to improved health outcomes and increased social cohesiveness. Racially and ethnically diverse populations were disproportionately affected by disparities in access and quality.

- Disagreements: In regions that are characterized by elevated social tension or inadequate initial safety, certain research has indicated inconsistent or negligible correlations between social cohesiveness and access to green spaces (Hong et al., 2014). Comparison was made difficult by the inconsistent nature of cohesiveness and exposure measurement instruments. Furthermore, while certain studies linked green gentrification to a decrease in cohesiveness, others found no significant change or even minor improvements in social connections, particularly during the initial phases of projects.

Discussion

Summary of Main Findings

Comparison with Existing Literature

Strengths and Limitations of the Evidence Base

- Selection bias: A significant number of studies employed convenience samples or community volunteers, which may have resulted in a dominance of individuals who are already engaged with green spaces.

- Linguistic and cultural scope: The research that was examined was published in English, which may have resulted in the exclusion of relevant data from non-English-speaking contexts.

- Publication bias: The emphasis on peer-reviewed literature may distort findings in favor of favorable connections, resulting in a scarcity of reporting on null or negative effects.

- Quality variation: While some studies were deficient in precise exposure measurement or did not account for confounding factors, others utilized stringent geographical analysis and validated psychometric instruments (Kephart, 2022; Mullenbach et al., 2022).

- Search limitations: Although the database searches were comprehensive, they may not have incorporated developing information from urban planning or community development sources that are not indexed in biomedical databases.

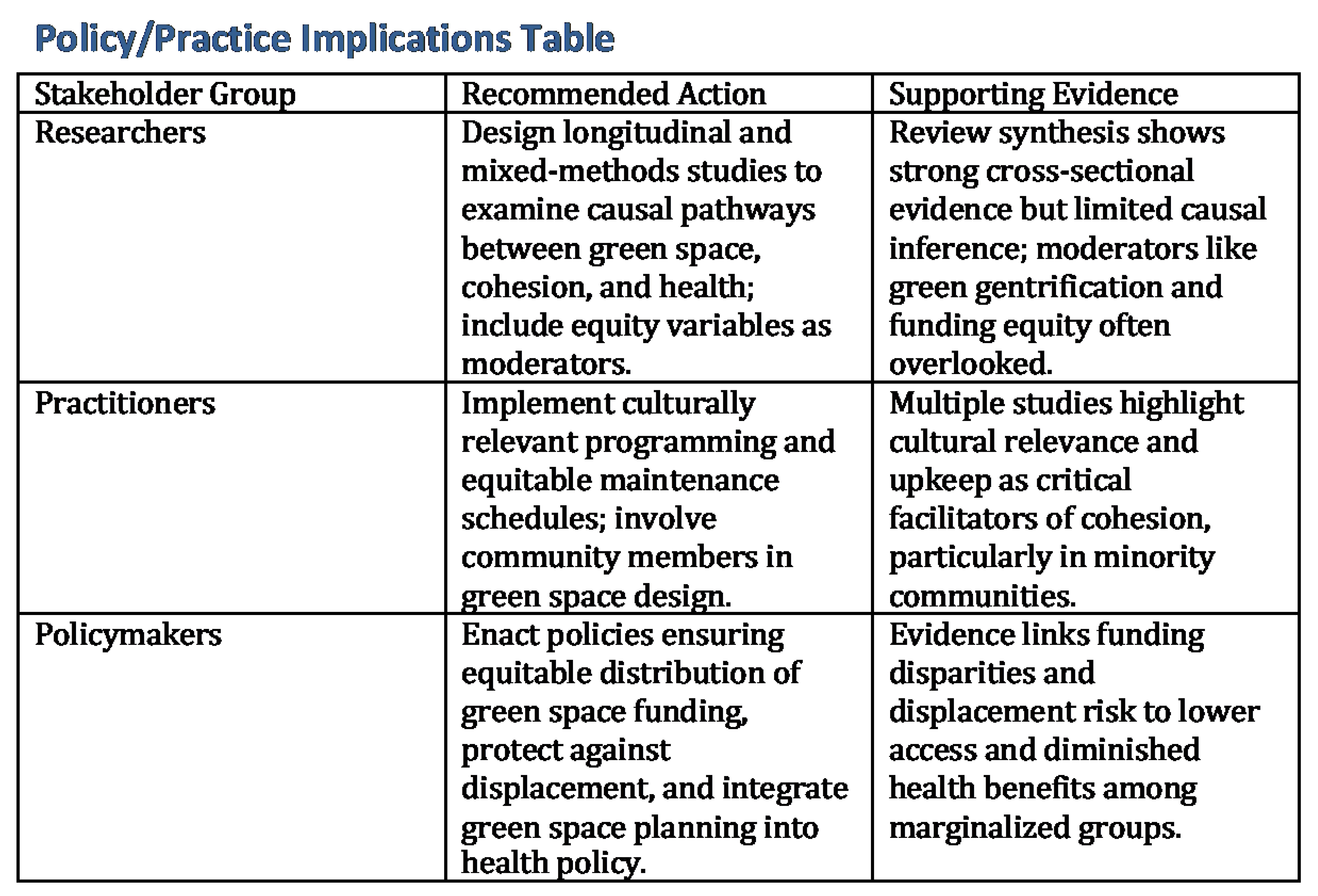

Implications for Practice, Research, and Policy

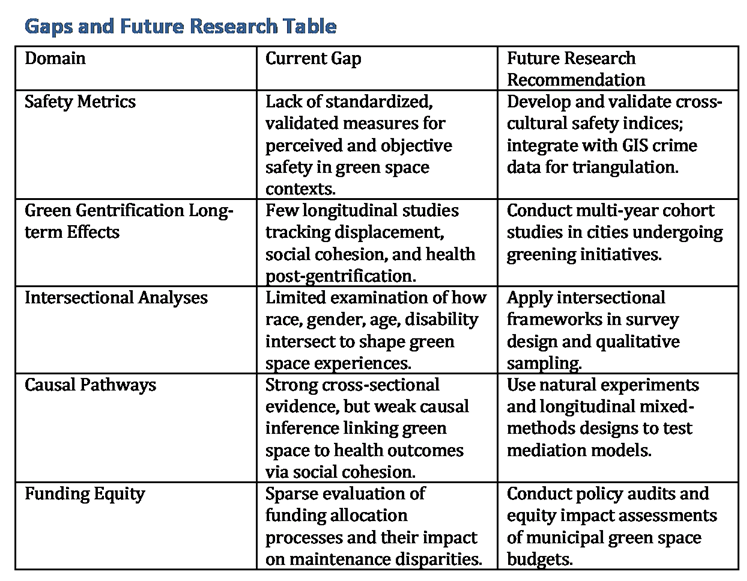

Unanswered Questions and Gaps

- Mechanistic pathways: While the correlations between social cohesiveness and green space are well-established, the specific mediating mechanisms, particularly in heterogeneous contexts, necessitate further clarification.

- Safety metrics: There is a scarcity of research that employs standardized, objective safety measures; the development and validation of such instruments could enhance comparability.

- Consequences of green gentrification in the long term: Particularly in regions that experience recurrent redevelopment cycles, there is a lack of evidence regarding the enduring effects of these changes over the course of decades.

Controversies and Ongoing Debates

Conclusion

Key Messages

Recommendations

- Prioritize longitudinal and mixed-methods research to clarify the causal relationships between health outcomes, social cohesiveness, and access to green spaces (Wan et al., 2021).

- Incorporate intersectional studies to investigate the cumulative effects of socioeconomic status, gender, ethnicity, and race (Roberts et al., 2022).

- Develop metrics for safety and cohesiveness that are standardized and have been proved effective in multicultural settings (Schiefer & van der Noll, 2017).

- Engage communities in co-design initiatives to ensure that the attributes of green spaces align with cultural preferences, safety requirements, and recreational interests (Oh et al., 2022).

- To prevent inequities in park quality, it is necessary to establish equitable maintenance schedules and infrastructural expenditures (Huang & Lin, 2021).

Future Research Directions

- Mechanistic Understanding: Investigate the mediating roles of leisure inclusion, safety perception, and cultural fit in the relationship between green space and social cohesiveness (Murillo et al., 2020).

- Standardization of Measures: Develop and verify cross-cultural instruments that assess both subjective and objective safety, as well as social cohesiveness attributes (Schiefer & van der Noll, 2017).

- Longitudinal Effects of Green Gentrification: Conduct extended follow-up studies in gentrifying districts to evaluate the long-term effects on community cohesiveness, health, and displacement (Anguelovski et al., 2019).

- Climate Adaptation Integration: Examine the influence of climate resilience initiatives in the context of green infrastructure on the cohesiveness of historically marginalized communities (Venter et al., 2020).

- Technology and Engagement: Evaluate the influence of digital technologies, such as participatory mapping platforms, on the enhancement of community engagement and the utilization of natural spaces.

- Post-Pandemic Patterns: Evaluate the influence of modifications in park utilization during the COVID-19 recovery process on the trajectory of cohesiveness in a variety of communities (Holt-Lunstad, 2022).

References

- Berkman, L. F.; Glass, T. Social integration, social networks, social support, and health. Social Epidemiology 2000, 1, 137–173. [Google Scholar]

- Berger-Schmitt, R. Considering social cohesion in quality of life assessments: Concept and measurement. Social Indicators Research 2002, 58(3), 403–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratman, G. N.; Daily, G. C.; Levy, B. J.; Gross, J. J. The benefits of nature experience: Improved affect and cognition. Landscape and Urban Planning 2015, 138, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, M.; Wallace, C.; Cadaval, S.; Anderson, E.; Egerer, M.; Dinkins, L.; Platero, R. Factors that enhance or hinder social cohesion in urban greenspaces: A literature review. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2023, 84, 127936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, S.; van Dillen, S. M.; Groenewegen, P. P.; Spreeuwenberg, P. Streetscape greenery and health: Stress, social cohesion and physical activity as mediators. Social Science & Medicine 2013, 94, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finney, C. Black faces, white spaces: Reimagining the relationship of African Americans to the great outdoors; UNC Press Books, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gee, G. C.; Payne-Sturges, D. Environmental health disparities: A framework integrating psychosocial and environmental concepts. Environmental Health Perspectives 2005, 113(12), A18–A20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T.; Mitchell, R.; de Vries, S.; Frumkin, H. Nature and health. Annual Review of Public Health 2014, 35, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haslam, S. A.; Fong, P.; Haslam, C.; Cruwys, T. Connecting to community: A social identity approach to neighborhood mental health. Personality and Social Psychology Review 2023. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt-Lunstad, J. Social connection as a public health issue: The evidence and a systemic framework for prioritizing the “social” in social determinants of health. Annual Review of Public Health 2022, 43, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, P.; Banay, R. F.; Hart, J. E.; Laden, F. A review of the health benefits of greenness. Current Epidemiology Reports 2015, 2, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, V.; Bamkole, O. The relationship between social cohesion and urban green space: An avenue for health promotion. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2019, 16(3), 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, V.; Larson, L.; Yun, J. Advancing sustainability through urban green space: Cultural ecosystem services, equity, and social determinants of health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2016, 13(2), 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawachi, I.; Berkman, L. Social cohesion, social capital, and health. In Social Epidemiology; 2000; pp. 174–190. [Google Scholar]

- Larson, L.; Jennings, V.; Cloutier, S. A. Public parks and wellbeing in urban areas of the United States. PLoS ONE 2016, 11(4), e0153211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, H. N.; Thornton, C. P.; Rodney, T.; Thorpe, R. J., Jr.; Allen, J. Social cohesion in health: A concept analysis. ANS. Advances in Nursing Science 2020, 43(4), 375–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustakas, L. Social cohesion: Definitions, causes and consequences. Encyclopedia 2023, 3(3), 1028–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, R. J. The neighborhood context of well-being. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 2003, 46(3), S53–S64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiefer, D.; van der Noll, J. The essentials of social cohesion: A literature review. Social Indicators Research 2017, 132(2), 579–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanahan, D.; Lin, B.; Bush, R.; Gaston, K.; Dean, J.; Barber, E.; Fuller, R. Toward improved public health outcomes from urban nature. American Journal of Public Health 2015, 105(3), 470–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D. E. The rise of the environmental justice paradigm injustice framing and the social construction of environmental discourses. American Behavioral Scientist 2000, 43(4), 508–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Shen, G. Q.; Choi, S. Underlying relationships between public urban green spaces and social cohesion: A systematic literature review. City, Culture and Society 2021, 24, 100383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, K. L.; Lam, S. T.; McKeen, J. K.; Richardson, G. R.; van den Bosch, M.; Bardekjian, A. C. Urban trees and human health: A scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17(12), 4371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahirrao, P.; Khan, S. Assessing public open spaces: A case of city Nagpur, India. Sustainability 2021, 13(9), 4997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astell-Burt, T.; Hartig, T.; Putra, I. G. N. E.; Walsan, R.; Dendup, T.; Feng, X. Green space and loneliness: A systematic review with theoretical and methodological guidance for future research. Science of the Total Environment 2022, 847, 157521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astell-Burt, T.; Walsan, R.; Davis, W.; Feng, X. What types of green space disrupt a lonelygenic environment? A cohort study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 2023, 58(4), 745–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cock, J.; Fig, D. From colonial to community based conservation: Environmental justice and the national parks of South Africa. Social Dynamics 2012, 31(1), 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, D.; Sallis, J. F.; Kerr, J.; Lee, S.; Rosenberg, D. E. Neighborhood environment and physical activity among youth. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 2011, 41(4), 442–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, R. C.; Larson, B. M. H.; Burdsey, D. What limits Muslim communities’ access to nature? Barriers and opportunities in the United Kingdom; Nature and Space; Environment and Planning E, 2022; Volume 6, 3, pp. 880–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Astell-Burt, T. Lonelygenic environments: A call for research on multilevel determinants of loneliness. The Lancet Planetary Health 2022, 6(11), e933–e934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagliardi, C.; Pillemer, K.; Gambella, E.; Piccinini, F.; Fabbietti, P. Benefits for older people engaged in environmental volunteering and socializing activities in city parks: Preliminary results of a program in Italy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17(10), 3772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. A deep learning-based methodology to re-construct optimized re-structured mesh from architectural presentations. Doctoral dissertation, Texas A&M University). Texas A&M University, 2024. Available online: https://oaktrust.library.tamu.edu/items/0efc414a-f1a9-4ec3-bd19-f99d2a6e3392.

- Gorjian, M. Advances and challenges in GIS-based assessment of urban green infrastructure: A systematic review (2020–2024) [Preprint]. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. Green gentrification and community health in urban landscape: A scoping review of urban greening’s social impacts [Preprint, Version 1]. Research Square 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. Green schoolyard investments and urban equity: A systematic review of economic and social impacts using spatial-statistical methods [Preprint]. In Research Square; 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. Green schoolyard investments influence local-level economic and equity outcomes through spatial-statistical modeling and geospatial analysis in urban contexts. arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. Greening schoolyards and the spatial distribution of property values in Denver, Colorado [Preprint]. arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. Analyzing the relationship between urban greening and gentrification: Empirical findings from Denver, Colorado [Working paper]. In SSRN; 15 July 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. Greening schoolyards and urban property values: A systematic review of geospatial and statistical evidence [Preprint]. arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. Quantifying gentrification: A critical review of definitions, methods, and measurement in urban studies [Preprint]. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. Schoolyard greening, child health, and neighborhood change. arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. The impact of greening schoolyards on residential property values [Working paper]. In SSRN; 11 July 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. The impact of greening schoolyards on surrounding residential property values: A systematic review [Preprint, Version 1]. Research Square 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M. Urban schoolyard greening: A systematic review of child health and neighborhood change [Preprint]. Research Square 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M.; Quek, F. Enhancing consistency in sensible mixed reality systems: A calibration approach integrating haptic and tracking systems [Preprint]. In EasyChair; 2024; Available online: https://easychair.org/publications/preprint/KVSZ.

- Gorjian, M.; Caffey, S. M.; Luhan, G. A. Exploring architectural design 3D reconstruction approaches through deep learning methods: A comprehensive survey. Athens Journal of Sciences 2024, 11(2), 1–29. Available online: https://www.athensjournals.gr/sciences/2024-6026-AJS-Gorjian-02.pdf.

- Gorjian, M.; Caffey, S. M.; Luhan, G. A. Exploring architectural design 3D reconstruction approaches through deep learning methods: A comprehensive survey. Athens Journal of Sciences 2025, 12, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M.; Luhan, G. A.; Caffey, S. M. Analysis of design algorithms and fabrication of a graph-based double-curvature structure with planar hexagonal panels. arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, M.; Caffey, S. M.; Luhan, G. A. Exploring architectural design 3D reconstruction approaches through deep learning methods: A comprehensive survey. Athens Journal of Sciences 2024, 11(2), 1–29. Available online: https://www.athensjournals.gr/sciences/2024-6026-AJS-Gorjian-02.pdf.

- Jahangir, S. Perceived meaning of urban local parks and social well-being of elderly men: A qualitative study of Delhi and Kolkata. International Journal of Review of Research in Social Sciences 2018, 6(3), 243–247. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, R.; Xiao, Y.; Huang, B.; Chen, H.; Li, Z. Exploring the linkage between greenness exposure and depression among Chinese people: Mediating roles of physical activity, stress and social cohesion and moderating role of urbanicity. Health & Place 2019, 58, 102168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Office of the Surgeon General. Our epidemic of loneliness and isolation: The US Surgeon General’s advisory on the healing effects of social connection and community. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2023. Available online: https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/surgeon-general-social-connection-advisory.pdf.

- Peters, K.; Elands, B.; Buijs, A. Social interactions in urban parks: Stimulating social cohesion? Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2010, 9(2), 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quagraine, V. K.; Asibey, M. O.; Mosner-Ansong, K. F. Factors that influence user patronage and satisfaction of urban parks in Ghanaian cities: Case of the Rattray Park in Nhyiaeso, Kumasi. Local Environment 2024, 29(2), 224–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raina, A. S.; Mone, V.; Gorjian, M.; Quek, F.; Sueda, S.; Krishnamurthy, V. R. Blended physical-digital kinesthetic feedback for mixed reality-based conceptual design-in-context. In Proceedings of the 50th Graphics Interface Conference (Article 6; ACM, 2024; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, D.; Pasimeni, M. R.; Petrosillo, I. The role of green infrastructures in Italian cities by linking natural and social capital. Ecological Indicators 2020, 108, 105694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, Z. S.; Shackleton, C. M.; Van Staden, F.; Selomane, O.; Masterson, V. A. Green apartheid: Urban green infrastructure remains unequally distributed across income and race geographies in South Africa. Landscape and Urban Planning 2020, 203, 103889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abada, T.; Hou, F.; Ram, B. Racially mixed neighborhoods, perceived neighborhood social cohesion, and adolescent health in Canada. Social Science & Medicine 2007, 65(10), 2004–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhasan, D. M.; Gaston, S. A.; Gullett, L. R.; Braxton Jackson, W.; Stanford, F. C.; Jackson, C. L. Neighborhood social cohesion and obesity in the United States. Endocrine and Metabolic Science 11 2023, 100129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhasan, D. M.; Gaston, S. A.; Jackson, W. B.; Williams, P. C.; Kawachi, I.; Jackson, C. L. Neighborhood social cohesion and sleep health by age, sex/gender, and race/ethnicity in the United States. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17(24), 9475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, J. O.; Mueller, M.; Newman, S. D.; Magwood, G.; Ahluwalia, J. S.; White, K.; Tingen, M. S. The association of individual and neighborhood social cohesion, stressors, and crime on smoking status among African-American women in southeastern US subsidized housing neighborhoods. Journal of Urban Health 2014, 91(6), 1158–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleton, A. A.; Holdsworth, E. A.; Kubzansky, L. D. A systematic review of the interplay between social determinants and environmental exposures for early-life outcomes. Current Environmental Health Reports 2016, 3(3), 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, D. S.; Williams, D. R. Understanding the role of ethnicity in outdoor recreation experiences. Journal of Leisure Research 1993, 25(1), 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpiano, R. M. Toward a neighborhood resource-based theory of social capital for health: Can Bourdieu and sociology help? Social Science & Medicine 2006, 62(1), 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaparro, M. P.; Pina, M. F.; de Oliveira Cardoso, L.; Santos, S. M.; Barreto, S. M.; Gonçalves, L. G.; de Matos, S. M. A.; da Fonseca, M. D. J. M.; Chor, D.; Griep, R. H. The association between the neighbourhood social environment and obesity in Brazil: A cross-sectional analysis of the ELSA-Brasil study. BMJ Open 2019, 9(9), e026800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, Y.-C.; Chuang, K.-Y.; Yang, T.-H. Social cohesion matters in health. International Journal for Equity in Health 12 2013, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coll-Planas, L.; Carbó-Cardeña, A.; Jansson, A.; Dostálová, V.; Bartova, A.; Rautiainen, L.; Kolster, A.; Masó-Aguado, M.; Briones-Buixassa, L.; Blancafort-Alias, S.; et al. Nature-based social interventions to address loneliness among vulnerable populations: A common study protocol for three related randomized controlled trials in Barcelona, Helsinki, and Prague within the RECETAS European project. BMC Public Health 24 2024, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulin, A. J.; Park, J. W.; Scarpaci, M. M.; Dionne, L. A.; Sims, M.; Needham, B. L.; Fava, J. L.; Eaton, C. B.; Kanaya, A. M.; Kandula, N. R. Examining relationships between perceived neighborhood social cohesion and ideal cardiovascular health and whether psychosocial stressors modify observed relationships among JHS, MESA, and MASALA participants. BMC Public Health 22 2022, 1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeverría, S.; Diez-Roux, A. V.; Shea, S.; Borrell, L. N.; Jackson, S. Associations of neighborhood problems and neighborhood social cohesion with mental health and health behaviors: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Health & Place 2008, 14(4), 853–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.; Das, K. V.; Chen, Q. Neighborhood green, social support, physical activity, and stress: Assessing the cumulative impact. Health & Place 2011, 17(6), 1202–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Floyd, M. F.; Gramann, J. H.; Saenz, R. Ethnic factors and the use of public outdoor recreation areas: The case of Mexican Americans. Leisure Sciences 1993, 15(2), 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobster, P. H. Managing urban parks for a racially and ethnically diverse clientele. Leisure Sciences 2002, 24(2), 143–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, E. Puerto Ricans and recreation participation: Methodological, cultural, and perceptual considerations. World Leisure Journal 2002, 44(2), 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C. P. Levels of racism: A theoretic framework and a gardener’s tale. American Journal of Public Health 2000, 90(8), 1212–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knobel, P.; Kondo, M.; Maneja, R.; Zhao, Y.; Dadvand, P.; Schinasi, L. H. Associations of objective and perceived greenness measures with cardiovascular risk factors in Philadelphia, PA: A spatial analysis. Environmental Research 197 2021, 110990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koltko-Rivera, M. E. Rediscovering the later version of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs: Self-transcendence and opportunities for theory, research, and unification. Review of General Psychology 2006, 10(4), 302–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubzansky, L. D.; Seeman, T. E.; Glymour, M. M. Biological pathways linking social conditions and health. In Social epidemiology, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press, 2014; pp. 512–561. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, N. Building a network theory of social capital. In Social capital; Routledge, 2017; pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow, A. H. A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review 1943, 50(4), 370–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, K. A.; Kubzansky, L. D.; Dunn, E. C.; Waldinger, R.; Vaillant, G.; Koenen, K. C. Childhood social environment, emotional reactivity to stress, and mood and anxiety disorders across the life course. Depression and Anxiety 2010, 27(12), 1087–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, R.; Coutts, C.; Mohamadi, A. Neighborhood urban form, social environment, and depression. Journal of Urban Health 2012, 89(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouratidis, K.; Poortinga, W. Built environment, urban vitality and social cohesion: Do vibrant neighborhoods foster strong communities? Landscape and Urban Planning 204 2020, 103951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulvaney-Day, N. E.; Alegría, M.; Sribney, W. Social cohesion, social support, and health among Latinos in the United States. Social Science & Medicine 2007, 64(2), 477–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, L.; Arredondo, E.; McKenzie, T.; Holguin, M.; Elder, J.; Ayala, G. Neighborhood social cohesion and depressive symptoms among Latinos: Does use of community resources for physical activity matter? Journal of Physical Activity & Health 2015, 12(10), 1361–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios, R.; Aiken, L. S.; Zautra, A. J. Neighborhood contexts and the mediating role of neighborhood social cohesion on health and psychological distress among Hispanic and non-Hispanic residents. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 2012, 43(1), 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaull, S. L.; Gramann, J. H. The effect of cultural assimilation on the importance of family-related and nature-related recreation among Hispanic Americans. Journal of Leisure Research 1998, 30(1), 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Zhang, X.; Xuan, Y. Linking neighborhood green spaces to loneliness among elderly residents—A path analysis of social capital. Cities 149 2024, 104952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Commerce; Economics and Statistics Administration. Demographic turning points for the United States: Population projections for 2020 to 2060; U.S. Government Printing Office, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Vespa, J.; Armstrong, D. M.; Medina, L. Demographic turning points for the United States: Population projections for 2020 to 2060; U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D. R.; Stremthal, M. Understanding racial-ethnic disparities in health: Sociological contributions. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 2010, 51(S), S15–S27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M. C.; Gerber, M. W.; Ash, T.; Horan, C. M.; Taveras, E. M. Neighborhood social cohesion and sleep outcomes in the Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander National Health Interview Survey. Sleep 2018, 41(8), zsy097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Zhang, W.; Walton, E. Neighborhoods and mental health: Exploring ethnic density, poverty, and social cohesion among Asian Americans and Latinos. Social Science & Medicine 2014, 111, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, V.; Baptiste, A. K.; Osborne Jelks, N. T.; Skeete, R. Urban green space and the pursuit of health equity in parts of the United States. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2017, 14(11), 1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, J.; Aspinall, P. A.; Ward Thompson, C. Understanding relationships between health, ethnicity, place and the role of urban green space in deprived urban communities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2016, 13(7), 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J. D.; Dickinson, K. L.; Hendricks, M. D.; Jennings, V. I can’t breathe: Examining the legacy of American racism on determinants of health and the ongoing pursuit of environmental justice. Current Environmental Health Reports 2022, 9, 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schell, C. J.; Dyson, K.; Fuentes, T. L.; Des Roches, S.; Harris, N. C.; Miller, D. S.; Woelfle-Erskine, C. A.; Lambert, M. R. The ecological and evolutionary consequences of systemic racism in urban environments. Science 2020, 369(6510), eaay4497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullenbach, L. E.; Breyer, B.; Cutts, B. B.; Rivers, L., III; Larson, L. R. An antiracist, anticolonial agenda for urban greening and conservation. Conservation Letters 2022, 15(5), e12889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. J.; Fernandez, M.; Scott, D.; Floyd, M. Slow violence in public parks in the U.S.: Can we escape our troubling past? Social & Cultural Geography 2023, 24(8), 1185–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kephart, L. How racial residential segregation structures access and exposure to greenness and green space: A review. Environmental Justice 2022, 15(3), 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dannenberg, A. L.; Frumkin, H.; Jackson, R. J. Making healthy places: Designing and building for health, well-being, and sustainability; Island Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Koo, B. W.; Guhathakurta, S.; Botchwey, N. How are neighborhood and street-level walkability factors associated with walking behaviors? A big data approach using street view images. Environment and Behavior 2022, 54(2), 211–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullenbach, L. E.; Larson, L. R.; Floyd, M. F.; Marquet, O.; Huang, J.-H.; Alberico, C.; Ogletree, S. S.; Hipp, J. A. Cultivating social capital in diverse, low-income neighborhoods: The value of parks for parents with young children. Landscape and Urban Planning 2022, 219, 104313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calise, T. V.; Chow, W.; Ryder, A.; Wingerter, C. Food access and its relationship to perceived walkability, safety, and social cohesion. Health Promotion Practice 2018, 20(6), 858–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo, R.; Reesor-Oyer, L. M.; Liu, Y.; Desai, S.; Hernandez, D. C. The role of neighborhood social cohesion in the association between seeing people walk and leisure-time walking among Latino adults. Leisure Sciences 2020, 45(5), 594–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, F.-A.; Lim, T. C. Examining privilege and power in US urban parks and open space during the double crises of antiblack racism and COVID-19. Socio-Ecological Practice Research 2021, 3(1), 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, R. R. Y.; Zhang, Y.; Nghiem, L. T. P.; Chang, C.-C.; Tan, C. L. Y.; Quazi, S. A.; Shanahan, D. F.; Lin, B. B.; Gaston, K. J.; Fuller, R. A.; others. Connection to nature and time spent in gardens predicts social cohesion. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2022, 74, 127655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broyles, S. T.; Mowen, A. J.; Theall, K. P.; Gustat, J.; Rung, A. L. Integrating social capital into a park-use and active-living framework. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 2011, 40(5), 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, L.; Guzman, P.; Glowa, K. M.; Drevno, A. G. Can home gardens scale up into movements for social change? The role of home gardens in providing food security and community change in San Jose, California. Local Environment 2014, 19(2), 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malberg Dyg, P.; Christensen, S.; Peterson, C. J. Community gardens and wellbeing amongst vulnerable populations: A thematic review. Health Promotion International 2019, 35(4), 790–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, H. O.; Tsuchiya, K.; Nguyen, A. W.; Mueller, C. Sociodemographic factors and neighborhood/environmental conditions associated with social isolation among Black older adults. Journal of Aging and Health 2023, 35(3–4), 294–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendricks, M. D. Leveraging critical infrastructure within an environmental justice framework for public health prevention. American Journal of Public Health 2022, 112(7), 972–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, M. R.; Diez-Roux, A. V.; Hajat, A.; Kershaw, K. N.; O’Neill, M. S.; Guallar, E.; Post, W. S.; Kaufman, J. D.; Navas-Acien, A. Race/ethnicity, residential segregation, and exposure to ambient air pollution: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). American Journal of Public Health 2014, 104(11), 2130–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne-Sturges, D.; Gee, G. C. National environmental health measures for minority and low-income populations: Tracking social disparities in environmental health. Environmental Research 2006, 102(2), 154–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, V.; Johnson Gaither, C.; Gragg, R. Promoting environmental justice through urban green space access: A synopsis. Environmental Justice 2012, 5(1), 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesdale, B. M.; Morello-Frosch, R.; Cushing, L. The racial/ethnic distribution of heat risk-related land cover in relation to residential segregation. Environmental Health Perspectives 2013, 121(7), 811–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branas, C. C.; South, E.; Kondo, M. C.; Hohl, B. C.; Bourgois, P.; Wiebe, D. J.; MacDonald, J. M. Citywide cluster randomized trial to restore blighted vacant land and its effects on violence, crime, and fear. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2018, 115(12), 2946–2951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, K. P.; Eberly, L. A.; Julien, H. M.; Giri, J.; Fanaroff, A. C.; Groeneveld, P. W.; Khatana, S. A. M.; Nathan, A. S.; others. Association between racial residential segregation and Black-White disparities in cardiovascular disease mortality. American Heart Journal 2023, 264, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, M.; Maloney, T. N. Latino residential isolation and the risk of obesity in Utah: The role of neighborhood socioeconomic built-Environmental, and Subcultural Context. In J. Immigr. Minor. Health; CrossRef, n.d.; Volume 13, pp. 1134–1141. [Google Scholar]

- Rigolon, A.; Browning, M.; Jennings, V. Inequities in the quality of urban park systems: An environmental justice investigation of cities in the United States. Landscape and Urban Planning 2018, 178, 156–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Cho, A.; Nguyen, Q.; Nsoesie, E. O. Association of neighborhood racial and ethnic composition and historical redlining with built environment indicators derived from street view images in the US. JAMA Network Open 2023, 6, e2251201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cushing, L.; Morello-Frosch, R.; Wander, M.; Pastor, M. The haves, the have-nots, and the health of everyone: The relationship between social inequality and environmental quality. Annual Review of Public Health 2015, 36, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, E. B.; Seyfried, A. P.; Pender, S. E.; Heard, K.; Meindl, G. A. Racial disparities in access to public green spaces: Using geographic information systems to identify underserved populations in a small American city. Environmental Justice 2022, 15, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korah, P. I.; Akaateba, M. A.; Akanbang, B. A. A. Spatio-temporal patterns and accessibility of green spaces in Kumasi, Ghana. Habitat International 2024, 144, 103010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, V.; Johnson Gaither, C. Approaching environmental health disparities and green spaces: An ecosystem services perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2015, 12, 1952–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Liu, Y.; Cao, J.; Ye, R. The impact of perceived racism on walking behavior during the COVID-19 lockdown. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 2022, 109, 103335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.; Rigolon, A.; Choi, D. A.; Lyons, T.; Brewer, S. Transit to parks: An environmental justice study of transit access to large parks in the US West. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2021, 60, 127055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, J.; Yue, X. Design and social factors affecting the formation of social capital in Chinese community gardens. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyden, K. M. Social capital and the built environment: The importance of walkable neighborhoods. American Journal of Public Health 2003, 93, 1546–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lwin, K. K.; Murayama, Y. Modelling of urban green space walkability: Eco-friendly walk score calculator. Computers, Environment and Urban Systems 2011, 35, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barajas, J. M. Biking where Black: Connecting transportation planning and infrastructure to disproportionate policing. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 2021, 99, 103027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. J.; Casper, J.; Powell, R.; Floyd, M. F. African Americans’ outdoor recreation involvement, leisure satisfaction, and subjective well-being. Current Psychology 2023, 42, 27840–27850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Han, A. Leisure-time physical activity mediates the relationship between neighborhood social cohesion and mental health among older adults. Journal of Applied Gerontology 2019, 39, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Recreation and Parks Association. 2020 engagement with parks report. National Recreation and Parks Association. 2020. Available online: https://www.nrpa.org/publications-research.

- Morata, T.; López, P.; Marzo, T.; Palasí, E. The influence of leisure-based community activities on neighborhood support and the social cohesion of communities in Spain. International Social Work 2021, 66, 568–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowen, A. J.; Rung, A. L. Park-based social capital: Are there variations across visitors with different socio-demographic characteristics and behaviours? Leisure/Loisir 2016, 40, 297–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, A.; Mowatt, R. A.; Floyd, M. F. A people’s future of leisure studies: Political cultural Black outdoors experiences. Journal of Park and Recreation Administration 2022, 40, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A. L.; Adams, A. E.; Stein, T. V. Equity, identity, and representation in outdoor recreation: ‘I am not an outdoors person’. Leisure Studies 2023. Advance online publication.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Baker, B. L.; Pitas, N. A.; Benfield, J. A.; Hickerson, B. D.; Mowen, A. J. Perceived ownership of urban parks: The role of the social environment. Journal of Leisure Research 2023, 54, 72–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemmell, E.; Ramsden, R.; Brussoni, M.; Brauer, M. Influence of neighborhood built environments on the outdoor free play of young children: A systematic, mixed-studies review and thematic synthesis. Journal of Urban Health 2023, 100, 118–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hordyk, S. R.; Hanley, J.; Richard, É. Nature is there; it’s free: Urban greenspace and the social determinants of health of immigrant families. Health & Place 2015, 34, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramovic, J.; Turner, B.; Hope, C. Entangled recovery: Refugee encounters in community gardens. Local Environment 2019, 24, 696–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietsch, A. M.; Jazi, E.; Floyd, M. F.; Ross-Winslow, D.; Sexton, N. R. Trauma and transgression in nature-based leisure. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living 2021, 3, 735024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stodolska, M.; Shinew, K. J.; Acevedo, J. C.; Izenstark, D. Perceptions of urban parks as havens and contested terrains by Mexican-Americans in Chicago neighborhoods. Leisure Sciences 2011, 33, 103–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, K.; Klusaritz, H.; Dupuis, R.; Bolick, A.; Graves, A.; Lipman, T. H.; Cannuscio, C. Reconciling opposing perceptions of access to physical activity in a gentrifying urban neighborhood. Public Health Nursing 2019, 36, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Lin, G. The relationship between urban green space and social health of individuals: A scoping review. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2023, 85, 127969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raap, S.; Knibbe, M.; Horstman, K. Clean spaces, community building, and urban stage: The coproduction of health and parks in low-income neighborhoods. Journal of Urban Health 2022, 99, 680–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groshong, L.; Wilhelm Stanis, S. A.; Kaczynski, A. T.; Hipp, J. A. Attitudes about perceived park safety among residents in low-income and high minority Kansas City, Missouri, neighborhoods. Environment and Behavior 2020, 52(7), 639–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, B. K.; Jim, C. Y. Contributions of human and environmental factors to concerns of personal safety and crime in urban parks. Security Journal 2022, 35(3), 263–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, J. G.; Holland, S. M. Strategies in use to reduce incivilities, provide security and reduce crime in urban parks. Security Journal 2015, 28(4), 374–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, D. M.; Furr, L. A. The effects of neighborhood conditions on perceptions of safety. Journal of Criminal Justice 2002, 30(5), 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcelli, P. Leveling the playing field? Urban disparities in funding for local parks and recreation in the Los Angeles region; Economy and Space; Environment and Planning A, 2010; Volume 42, 5, pp. 1174–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, G. R.; Yuen, H. K.; Rose, E. J.; Maher, A. I.; Gregory, K. C.; Cotton, M. E. Disparities in quality of park play spaces between two cities with diverse income and race/ethnicity composition: A pilot study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2015, 12(6), 8009–8022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruton, C.; Floyd, M. Disparities in built and natural features of urban parks: Comparisons by neighborhood level race/ethnicity and income. Journal of Urban Health 2014, 91(5), 894–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suminski, R. R.; Connolly, E. K.; May, L. E.; Wasserman, J.; Olvera, N.; Lee, R. E. Park quality in racial/ethnic minority neighborhoods. Environmental Justice 2012, 5(5), 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruijsbroek, A.; Droomers, M.; Groenewegen, P. P.; Hardyns, W.; Stronks, K. Social safety, self-rated general health and physical activity: Changes in area crime, area safety feelings and the role of social cohesion. Health & Place 31 2015, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, A.; Sallis, J. F.; King, A. C.; Conway, T. L.; Saelens, B.; Cain, K. L.; Fox, E. H.; Frank, L. D. Linking green space to neighborhood social capital in older adults: The role of perceived safety. Social Science & Medicine 207 2018, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).