Submitted:

10 August 2025

Posted:

14 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

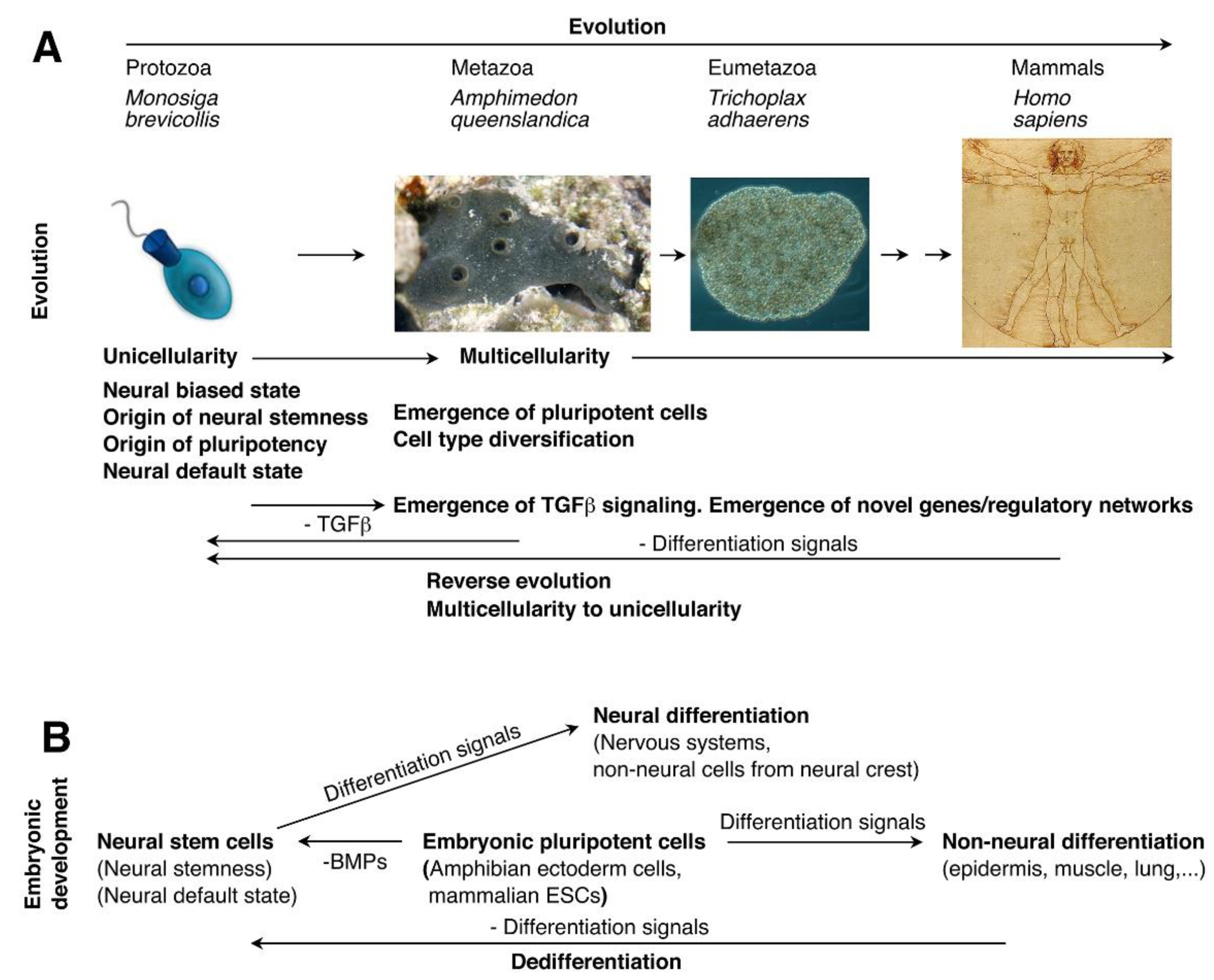

1. Neural Stemness Represents the General Stemness

1.1. Pluripotency of Neural Stem Cells (NSCs)

1.2. The ‘Neural Default State’ of Embryonic Pluripotent Cells

1.3. Unicellular Origin of Neural Stemness

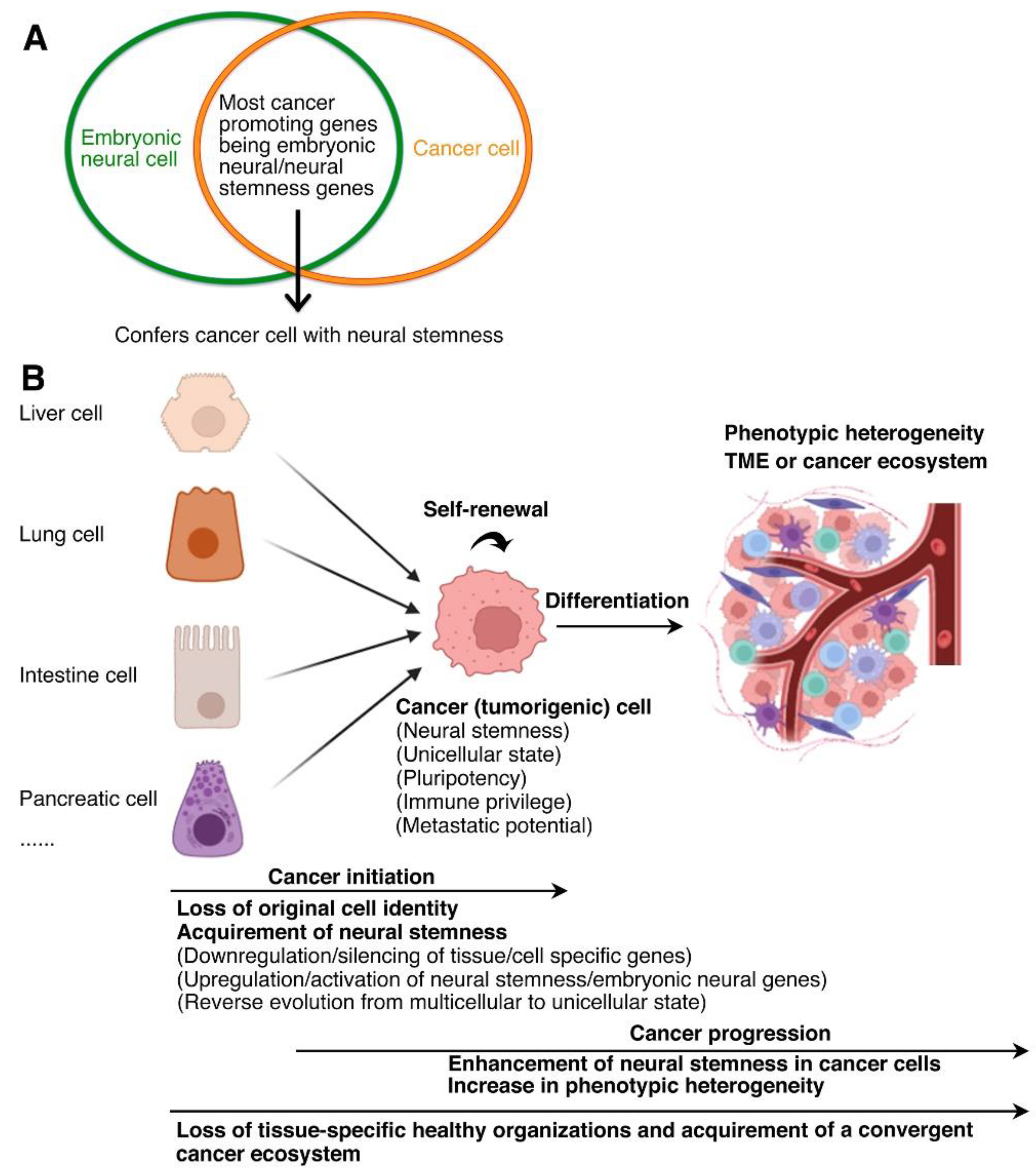

2. Neural Stemness as the Core Property of Cancer Cell

2.1. Cancer (Tumorigenic) Cells Are Characteristic of Neural Stem/Embryonic Neural Cells

2.2. Neural Stemness as the Source of Cell Tumorigenicity

2.3. Pluripotency and Tumorigenicity: Two Sides of a Same Coin

2.4. Neural Stemness or General Stemness Represents Cancer Stemness

2.5. Neural Stemness Unifies Phenotypic Traits of Cancer Cells

2.6. Neural Stemness and Immune Privilege of Cancer Cells

3. Neural Stemness Unifies Embryogenesis and Tumorigenesis

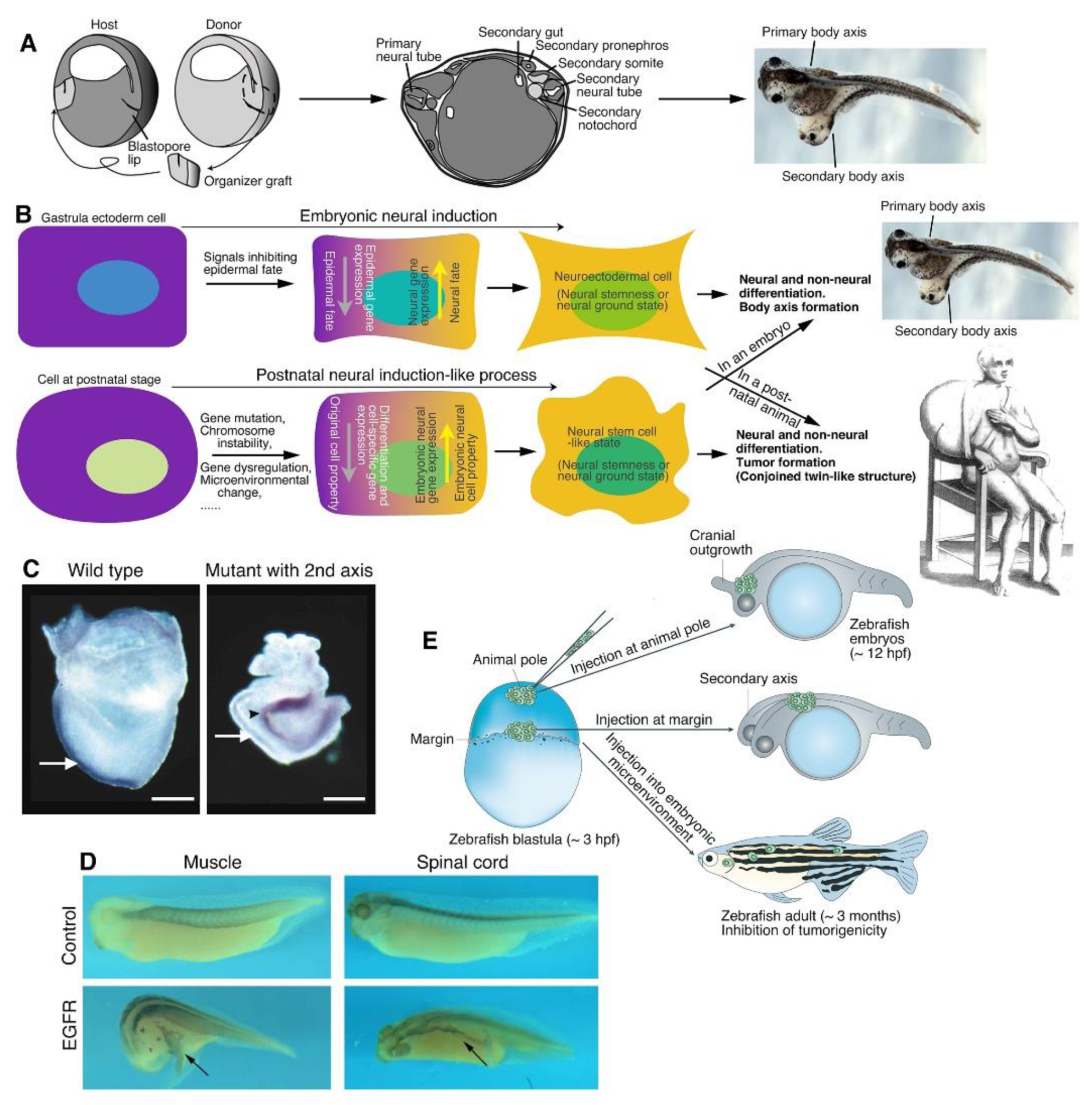

3.1. Embryonic Neural Induction, Body Axis Formation and Embryogenesis

3.2. Neural Induction-Like Process During Tumorigenesis, and the Hallmarks of Tumorigenesis as a Conjoined Twin-Like Formation in a Postnatal Animal/Human

4. Important Issues to Consider or Re-Consider in Cancer Research

5. Neural Stemness Being the Core Property of Cancer Cell Paves the Road to Differentiation Therapy of Cancer

Conclusion

Author Contributions

Acknowledgment

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adamska, M; Degnan, SM; Green, KM; Adamski, M; Craigie, A; Larroux, C; Degnan, BM. Wnt and TGF-beta expression in the sponge Amphimedon queenslandica and the origin of metazoan embryonic patterning. PLoS One 2007, 2(10), e1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguadé-Gorgorió, G; Anderson, ARA; Solé, R. Modeling tumors as complex ecosystems. iScience 2024, 27(9), 110699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agudo, J; Miao, Y. Stemness in solid malignancies: coping with immune attack. Nat Rev Cancer 2025, 25(1), 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F; Patrick, S; Sheikh, T; Sharma, V; Pathak, P; Malgulwar, PB; Kumar, A; Joshi, SD; Sarkar, C; Sen, E. Telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT)-enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) network regulates lipid metabolism and DNA damage responses in glioblastoma. J Neurochem 2017, 143(6), 671–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfarouk, KO; Shayoub, ME; Muddathir, AK; Elhassan, GO; Bashir, AH. Evolution of Tumor Metabolism might Reflect Carcinogenesis as a Reverse Evolution process (Dismantling of Multicellularity). Cancers (Basel) 2011, 3(3), 3002–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaravadi, LS; Neff, AW; Sleeman, JP; Smith, RC. Autonomous neural axis formation by ectopic expression of the protooncogene c-ski. Dev Biol 1997, 192(2), 392–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anatskaya, OV; Vinogradov, AE; Vainshelbaum, NM; Giuliani, A; Erenpreisa, J. Phylostratic Shift of Whole-Genome Duplications in Normal Mammalian Tissues towards Unicellularity Is Driven by Developmental Bivalent Genes and Reveals a Link to Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21(22), 8759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, C; Stern, CD. Organizers in Development. Curr Top Dev Biol 2016, 117, 435–54. [Google Scholar]

- Aranda-Anzaldo, A; Dent, MAR. Landscaping the epigenetic landscape of cancer. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 2018, 140, 155–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascic, E; Åkerström, F; Sreekumar Nair, M; Rosa, A; Kurochkin, I; Zimmermannova, O; Catena, X; Rotankova, N; Veser, C; Rudnik, M; Ballocci, T; Schärer, T; Huang, X; de Rosa Torres, M; Renaud, E; Velasco Santiago, M; Met, Ö; Askmyr, D; Lindstedt, M; Greiff, L; Ligeon, LA; Agarkova, I; Svane, IM; Pires, CF; Rosa, FF; Pereira, CF. In vivo dendritic cell reprogramming for cancer immunotherapy. Science 2024, 386(6719), eadn9083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakir, B; Chiarella, AM; Pitarresi, JR; Rustgi, AK. EMT, MET, Plasticity, and Tumor Metastasis. Trends Cell Biol 2020, 30(10), 764–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balinth, S; Fisher, ML; Hwangbo, Y; Wu, C; Ballon, C; Sun, X; Mills, AA. EZH2 regulates a SETDB1/ΔNp63α axis via RUNX3 to drive a cancer stem cell phenotype in squamous cell carcinoma. Oncogene 2022, 41(35), 4130–4144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baralle, FE; Giudice, J. Alternative splicing as a regulator of development and tissue identity. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2017, 18(7), 437–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-David, U; Benvenisty, N. The tumorigenicity of human embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat Rev Cancer 2011, 11(4), 268–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berk, M; Desai, SY; Heyman, HC; Colmenares, C. Mice lacking the ski proto-oncogene have defects in neurulation, craniofacial, patterning, and skeletal muscle development. Genes Dev 1997, 11(16), 2029–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharya, R; Avdieiev, SS; Bukkuri, A; Whelan, CJ; Gatenby, RA; Tsai, KY; Brown, JS. The Hallmarks of Cancer as Eco-Evolutionary Processes. Cancer Discov 2025, 15(4), 685–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boumahdi, S; Driessens, G; Lapouge, G; Rorive, S; Nassar, D; Le Mercier, M; Delatte, B; Caauwe, A; Lenglez, S; Nkusi, E; Brohée, S; Salmon, I; Dubois, C; del Marmol, V; Fuks, F; Beck, B; Blanpain, C. SOX2 controls tumour initiation and cancer stem-cell functions in squamous-cell carcinoma. Nature 2014, 511(7508), 246–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwmeester, T; Kim, S; Sasai, Y; Lu, B; De Robertis, EM. Cerberus is a head-inducing secreted factor expressed in the anterior endoderm of Spemann's organizer. Nature 1996, 382(6592), 595–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brickman, JM; Burdon, TG. Pluripotency and tumorigenicity. Nat Genet 2002, 32(4), 557–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinster, RL. The effect of cells transferred into the mouse blastocyst on subsequent development. J Exp Med 1974, 140(4), 1049–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britsch, S; Li, L; Kirchhoff, S; Theuring, F; Brinkmann, V; Birchmeier, C; Riethmacher, D. The ErbB2 and ErbB3 receptors and their ligand, neuregulin-1, are essential for development of the sympathetic nervous system. Genes Dev 1998, 12(12), 1825–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, RJ; Cross, NA; Eaton, CL; Hamdy, FC; Cunliffe, VT. EZH2 promotes proliferation and invasiveness of prostate cancer cells. Prostate 2007, 67(5), 547–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhardt, P; Stegmann, CM; Cooper, B; Kloepper, TH; Imig, C; Varoqueaux, F; Wahl, MC; Fasshauer, D. Primordial neurosecretory apparatus identified in the choanoflagellate Monosiga brevicollis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011, 108(37), 15264–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, SJ; Chen, L; Tovar-Corona, JM; Urrutia, AO. Alternative splicing and the evolution of phenotypic novelty. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2017, 372(1713), 20150474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussey, KJ; Cisneros, LH; Lineweaver, CH; Davies, PCW. Ancestral gene regulatory networks drive cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017, 114(24), 6160–6162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y. Tumorigenesis as a process of gradual loss of original cell identity and gain of properties of neural precursor/progenitor cells. Cell Biosci 2017, 7, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y. Neural is Fundamental: Neural Stemness as the Ground State of Cell Tumorigenicity and Differentiation Potential. Stem Cell Rev Rep 2022, 18(1), 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y. Neural induction drives body axis formation during embryogenesis, but a neural induction-like process drives tumorigenesis in postnatal animals. Front Cell Dev Biol 2023, 11, 1092667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y. Lack of basic rationale in epithelial-mesenchymal transition and its related concepts. Cell Biosci 2024, 14(1), 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celià-Terrassa, T; Jolly, MK. Cancer Stem Cells and Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition in Cancer Metastasis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2020, 10(7), a036905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaffer, CL; San Juan, BP; Lim, E; Weinberg, RA. EMT, cell plasticity and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev 2016, 35(4), 645–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H; Lin, F; Xing, K; He, X. The reverse evolution from multicellularity to unicellularity during carcinogenesis. Nat Commun 2015, 6, 6367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L; Zhang, M; Fang, L; Yang, X; Cao, N; Xu, L; Shi, L; Cao, Y. Coordinated regulation of the ribosome and proteasome by PRMT1 in the maintenance of neural stemness in cancer cells and neural stem cells. J Biol Chem 2021, 297(5), 101275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, DL; Johansson, CB; Wilbertz, J; Veress, B; Nilsson, E; Karlström, H; Lendahl, U; Frisén, J. Generalized potential of adult neural stem cells. Science 2000, 288(5471), 1660–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M; Pinkus, H. Intrauterine transplantation of rat basal cell carcinoma as a model for reconversion of malignant to benign growth. Cancer Res 1977, 37 8 Pt 1, 2544–52. [Google Scholar]

- Crea, F; Paolicchi, E; Marquez, VE; Danesi, R. Polycomb genes and cancer: time for clinical application? Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2012, 83(2), 184–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Magalhães, JP. Every gene can (and possibly will) be associated with cancer. Trends Genet 2022, 38(3), 216–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, J; Wang, ES; Jenkins, RW; Li, S; Dries, R; Yates, K; Chhabra, S; Huang, W; Liu, H; Aref, AR; Ivanova, E; Paweletz, CP; Bowden, M; Zhou, CW; Herter-Sprie, GS; Sorrentino, JA; Bisi, JE; Lizotte, PH; Merlino, AA; Quinn, MM; Bufe, LE; Yang, A; Zhang, Y; Zhang, H; Gao, P; Chen, T; Cavanaugh, ME; Rode, AJ; Haines, E; Roberts, PJ; Strum, JC; Richards, WG; Lorch, JH; Parangi, S; Gunda, V; Boland, GM; Bueno, R; Palakurthi, S; Freeman, GJ; Ritz, J; Haining, WN; Sharpless, NE; Arthanari, H; Shapiro, GI; Barbie, DA; Gray, NS; Wong, KK. CDK4/6 Inhibition Augments Antitumor Immunity by Enhancing T-cell Activation. Cancer Discov 2018, 8(2), 216–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, J; Zhang, Y; Xie, Y; Zhang, L; Tang, P. Cell Transplantation for Spinal Cord Injury: Tumorigenicity of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Neural Stem/Progenitor Cells. Stem Cells Int 2018, 2018, 5653787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sá Fernandes, C; Novoszel, P; Gastaldi, T; Krauß, D; Lang, M; Rica, R; Kutschat, AP; Holcmann, M; Ellmeier, W; Seruggia, D; Strobl, H; Sibilia, M. The histone deacetylase HDAC1 controls dendritic cell development and anti-tumor immunity. Cell Rep 2024, 43(6), 114308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Thé, H. Differentiation therapy revisited. Nat Rev Cancer 2018, 18(2), 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Robertis, EM. Spemann's organizer and self-regulation in amphibian embryos. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2006, 7(4), 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Robertis, EM. Spemann's organizer and the self-regulation of embryonic fields. Mech Dev 2009, 126(11-12), 925–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Robertis, EM; Kuroda, H. Dorsal-ventral patterning and neural induction in Xenopus embryos. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2004, 20, 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhanasekaran, R; Deutzmann, A; Mahauad-Fernandez, WD; Hansen, AS; Gouw, AM; Felsher, DW. The MYC oncogene-the grand orchestrator of cancer growth and immune evasion. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2022, 19(1), 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiBerardino, MA; Mizell, M; Hoffner, NJ; Friesendorf, DG. Frog larvae cloned from nuclei of pronephric adenocarcinoma. Differentiation 1983, 23(3), 213–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domazet-Loso, T; Brajković, J; Tautz, D. A phylostratigraphy approach to uncover the genomic history of major adaptations in metazoan lineages. Trends Genet 2007, 23(11), 533–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domazet-Loso, T; Tautz, D. Phylostratigraphic tracking of cancer genes suggests a link to the emergence of multicellularity in metazoa. BMC Biol 2010, 8, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dongre, A; Weinberg, RA. New insights into the mechanisms of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and implications for cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2019, 20(2), 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donohoe, ME; Zhang, X; McGinnis, L; Biggers, J; Li, E; Shi, Y. Targeted disruption of mouse Yin Yang 1 transcription factor results in peri-implantation lethality. Mol Cell Biol 1999, 19(10), 7237–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drukker, M; Katchman, H; Katz, G; Even-Tov Friedman, S; Shezen, E; Hornstein, E; Mandelboim, O; Reisner, Y; Benvenisty, N. Human embryonic stem cells and their differentiated derivatives are less susceptible to immune rejection than adult cells. Stem Cells 2006, 24(2), 221–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fändrich, F; Dresske, B; Bader, M; Schulze, M. Embryonic stem cells share immune-privileged features relevant for tolerance induction. J Mol Med (Berl) 2002, 80(6), 343–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatma, H; Maurya, SK; Siddique, HR. Epigenetic modifications of c-MYC: Role in cancer cell reprogramming, progression and chemoresistance. Semin Cancer Biol 2022, 83, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faust, C; Schumacher, A; Holdener, B; Magnuson, T. The eed mutation disrupts anterior mesoderm production in mice. Development 1995, 121(2), 273–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlay, JB; Ireland, AS; Hawgood, SB; Reyes, T; Ko, T; Olsen, RR; Abi Hachem, R; Jang, DW; Bell, D; Chan, JM; Goldstein, BJ; Oliver, TG. Olfactory neuroblastoma mimics molecular heterogeneity and lineage trajectories of small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Cell 2024, 42(6), 1086–1105.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, RG; Lytle, NK; Jaquish, DV; Park, FD; Ito, T; Bajaj, J; Koechlein, CS; Zimdahl, B; Yano, M; Kopp, J; Kritzik, M; Sicklick, J; Sander, M; Grandgenett, PM; Hollingsworth, MA; Shibata, S; Pizzo, D; Valasek, M; Sasik, R; Scadeng, M; Okano, H; Kim, Y; MacLeod, AR; Lowy, AM; Reya, T. Image-based detection and targeting of therapy resistance in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Nature 2016, 534(7607), 407–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funayama, N; Fagotto, F; McCrea, P; Gumbiner, BM. Embryonic axis induction by the armadillo repeat domain of beta-catenin: evidence for intracellular signaling. J Cell Biol 1995, 128(5), 959–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabel, HW; Kinde, B; Stroud, H; Gilbert, CS; Harmin, DA; Kastan, NR; Hemberg, M; Ebert, DH; Greenberg, ME. Disruption of DNA-methylation-dependent long gene repression in Rett syndrome. Nature 2015, 522(7554), 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galassi, C; Musella, M; Manduca, N; Maccafeo, E; Sistigu, A. The Immune Privilege of Cancer Stem Cells: A Key to Understanding Tumor Immune Escape and Therapy Failure. Cells 2021, 10(9), 2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, H; de Visser, KE. Immune crosstalk in cancer progression and metastatic spread: a complex conversation. Nat Rev Immunol 2020, 20(8), 483–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gassmann, M; Casagranda, F; Orioli, D; Simon, H; Lai, C; Klein, R; Lemke, G. Aberrant neural and cardiac development in mice lacking the ErbB4 neuregulin receptor. Nature 1995, 378(6555), 390–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhart, J. Evolution of the organizer and the chordate body plan. Int J Dev Biol 2001, 45(1), 133–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germain, ND; Hartman, NW; Cai, C; Becker, S; Naegele, JR; Grabel, LB. Teratocarcinoma formation in embryonic stem cell-derived neural progenitor hippocampal transplants. Cell Transplant 2012, 21(8), 1603–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerschenson, M; Graves, K; Carson, SD; Wells, RS; Pierce, GB. Regulation of melanoma by the embryonic skin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1986, 83(19), 7307–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glinka, A; Wu, W; Onichtchouk, D; Blumenstock, C; Niehrs, C. Head induction by simultaneous repression of Bmp and Wnt signalling in Xenopus. Nature 1997, 389(6650), 517–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godsave, SF; Slack, JM. Clonal analysis of mesoderm induction in Xenopus laevis. Dev Biol 1989, 134(2), 486–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Göhde, R; Naumann, B; Laundon, D; Imig, C; McDonald, K; Cooper, BH; Varoqueaux, F; Fasshauer, D; Burkhardt, P. Choanoflagellates and the ancestry of neurosecretory vesicles. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2021, 376(1821), 20190759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, JR; Lee, CK; Kim, HM; Kim, J; Jeon, J; Park, S; Cho, KH. Control of Cellular Differentiation Trajectories for Cancer Reversion. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2025, 12(3), e2402132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gootwine, E; Webb, CG; Sachs, L. Participation of myeloid leukaemic cells injected into embryos in haematopoietic differentiation in adult mice. Nature 1982, 299(5878), 63–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grunz, H; Tacke, L. Neural differentiation of Xenopus laevis ectoderm takes place after disaggregation and delayed reaggregation without inducer. Cell Differ Dev 1989, 28(3), 211–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajdu, SI. A note from history: landmarks in history of cancer, part 2. Cancer 2011, 117(12), 2811–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamed, AA; Hua, K; Trinh, QM; Simons, BD; Marioni, JC; Stein, LD; Dirks, PB. Gliomagenesis mimics an injury response orchestrated by neural crest-like cells. Nature 2025, 638(8050), 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harland, R. Induction into the Hall of Fame: tracing the lineage of Spemann's organizer. Development 2008, 135(20), 3321–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harland, R. Neural induction. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2000, 10(4), 357–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmati-Brivanlou, A; Melton, DA. Inhibition of activin receptor signaling promotes neuralization in Xenopus. Cell 1994, 77(2), 273–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henrique, D; Abranches, E; Verrier, L; Storey, KG. Neuromesodermal progenitors and the making of the spinal cord. Development 2015, 142(17), 2864–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrix, MJ; Seftor, EA; Seftor, RE; Kasemeier-Kulesa, J; Kulesa, PM; Postovit, LM. Reprogramming metastatic tumour cells with embryonic microenvironments. Nat Rev Cancer 2007, 7(4), 246–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hori, J; Ng, TF; Shatos, M; Klassen, H; Streilein, JW; Young, MJ. Neural progenitor cells lack immunogenicity and resist destruction as allografts. Stem Cells 2003, 21(4), 405–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochedlinger, K; Blelloch, R; Brennan, C; Yamada, Y; Kim, M; Chin, L; Jaenisch, R. Reprogramming of a melanoma genome by nuclear transplantation. Genes Dev 2004, 18(15), 1875–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S; Soto, AM; Sonnenschein, C. The end of the genetic paradigm of cancer. PLoS Biol 2025, 23(3), e3003052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Illmensee, K; Mintz, B. Totipotency and normal differentiation of single teratocarcinoma cells cloned by injection into blastocysts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1976, 73(2), 549–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intlekofer, AM; Finley, LWS. Metabolic signatures of cancer cells and stem cells. Nat Metab 2019, 1(2), 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itakura, G; Ozaki, M; Nagoshi, N; Kawabata, S; Nishiyama, Y; Sugai, K; Iida, T; Kashiwagi, R; Ookubo, T; Yastake, K; Matsubayashi, K; Kohyama, J; Iwanami, A; Matsumoto, M; Nakamura, M; Okano, H. Low immunogenicity of mouse induced pluripotent stem cell-derived neural stem/progenitor cells. Sci Rep 2017, 7(1), 12996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, F; Watabe, T; Miyazono, K. Roles of TGF-β family signals in the fate determination of pluripotent stem cells. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2014, 32, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalluri, R; Weinberg, RA. The basics of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Clin Invest 2009, 119(6), 1420–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanungo, J; Kozmik, Z; Swamynathan, SK; Piatigorsky, J. Gelsolin is a dorsalizing factor in zebrafish. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003, 100(6), 3287–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karasarides, M; Cogdill, AP; Robbins, PB; Bowden, M; Burton, EM; Butterfield, LH; Cesano, A; Hammer, C; Haymaker, CL; Horak, CE; McGee, HM; Monette, A; Rudqvist, NP; Spencer, CN; Sweis, RF; Vincent, BG; Wennerberg, E; Yuan, J; Zappasodi, R; Lucey, VMH; Wells, DK; LaVallee, T. Hallmarks of Resistance to Immune-Checkpoint Inhibitors. Cancer Immunol Res 2022, 10(4), 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, GM; Erezyilmaz, DF; Moon, RT. Induction of a secondary embryonic axis in zebrafish occurs following the overexpression of beta-catenin. Mech Dev 1995, 53(2), 261–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerk, SA; Papagiannakopoulos, T; Shah, YM; Lyssiotis, CA. Metabolic networks in mutant KRAS-driven tumours: tissue specificities and the microenvironment. Nat Rev Cancer 2021, 21(8), 510–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, DY; Rhee, I; Paik, J. Metabolic circuits in neural stem cells. Cell Mol Life Sci 2014, 71(21), 4221–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, HJ; Cantor, H; Cosmopoulos, K. Overcoming Immune Checkpoint Blockade Resistance via EZH2 Inhibition. Trends Immunol 2020, 41(10), 948–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, N; Westbrook, MJ; Young, SL; Kuo, A; Abedin, M; Chapman, J; Fairclough, S; Hellsten, U; Isogai, Y; Letunic, I; Marr, M; Pincus, D; Putnam, N; Rokas, A; Wright, KJ; Zuzow, R; Dirks, W; Good, M; Goodstein, D; Lemons, D; Li, W; Lyons, JB; Morris, A; Nichols, S; Richter, DJ; Salamov, A; Sequencing, JG; Bork, P; Lim, WA; Manning, G; Miller, WT; McGinnis, W; Shapiro, H; Tjian, R; Grigoriev, IV; Rokhsar, D. The genome of the choanoflagellate Monosiga brevicollis and the origin of metazoans. Nature 2008, 451(7180), 783–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, TJ; DiBerardino, MA. Transplantation of nuclei from the frog renal adenocarcinoma. I. Development of tumor nuclear-transplant embryos. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1965, 126(1), 115–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knecht, AK; Bronner-Fraser, M. Induction of the neural crest: a multigene process. Nat Rev Genet 2002, 3(6), 453–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulesa, PM; Kasemeier-Kulesa, JC; Teddy, JM; Margaryan, NV; Seftor, EA; Seftor, RE; Hendrix, MJ. Reprogramming metastatic melanoma cells to assume a neural crest cell-like phenotype in an embryonic microenvironment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006, 103(10), 3752–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lasse-Opsahl, EL; Barravecchia, I; McLintock, E; Lee, JM; Ferris, SF; Espinoza, CE; Hinshaw, R; Cavanaugh, S; Robotti, M; Rober, L; Brown, K; Abdelmalak, KY; Galban, CJ; Frankel, TL; Zhang, Y; Pasca di Magliano, M; Galban, S. KRASG12D drives immunosuppression in lung adenocarcinoma through paracrine signaling. JCI Insight 2025, 10(1), e182228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Douarin, NM; Dupin, E. The Pluripotency of Neural Crest Cells and Their Role in Brain Development. Curr Top Dev Biol 2016, 116, 659–78. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, A; Chen, L; Zhang, M; Yang, X; Xu, L; Cao, N; Zhang, Z; Cao, Y. EZH2 Regulates Protein Stability via Recruiting USP7 to Mediate Neuronal Gene Expression in Cancer Cells. Front Genet 2019, 10, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, M. Twinning and embryonic left-right asymmetry. Laterality 1999, 4(3), 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L; Connelly, MC; Wetmore, C; Curran, T; Morgan, JI. Mouse embryos cloned from brain tumors. Cancer Res 2003, 63(11), 2733–6. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z; Guo, X; Huang, H; Wang, C; Yang, F; Zhang, Y; Wang, J; Han, L; Jin, Z; Cai, T; Xi, R. A Switch in Tissue Stem Cell Identity Causes Neuroendocrine Tumors in Drosophila Gut. Cell Rep 2020, 30(6), 1724–1734.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linde, MH; Fan, AC; Köhnke, T; Trotman-Grant, AC; Gurev, SF; Phan, P; Zhao, F; Haddock, NL; Nuno, KA; Gars, EJ; Stafford, M; Marshall, PL; Dove, CG; Linde, IL; Landberg, N; Miller, LP; Majzner, RG; Zhang, TY; Majeti, R. Reprogramming Cancer into Antigen-Presenting Cells as a Novel Immunotherapy. Cancer Discov 2023, 13(5), 1164–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y; Wang, C; Li, J; Cao, Y. Differentiation status determines tumorigenicity and immunogenicity of cancer cells. bioRxiv 2025, 656250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llombart, V; Mansour, MR. Therapeutic targeting of "undruggable "MYC. EBioMedicine 2022, 75, 103756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, JJ; Ma, S. Hallmarks of cancer stemness. Cell Stem Cell 2024, 31(5), 617–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, W; Kang, Y. Epithelial-Mesenchymal Plasticity in Cancer Progression and Metastasis. Dev Cell 2019, 49(3), 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacColl Garfinkel, A; Mnatsakanyan, N; Patel, JH; Wills, AE; Shteyman, A; Smith, PJS; Alavian, KN; Jonas, EA; Khokha, MK. Mitochondrial leak metabolism induces the Spemann-Mangold Organizer via Hif-1α in Xenopus. Dev Cell 2023, 58(22), 2597–2613.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magliocca, JF; Held, IK; Odorico, JS. Undifferentiated murine embryonic stem cells cannot induce portal tolerance but may possess immune privilege secondary to reduced major histocompatibility complex antigen expression. Stem Cells Dev 2006, 15(5), 707–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahadevan, KK; McAndrews, KM; LeBleu, VS; Yang, S; Lyu, H; Li, B; Sockwell, AM; Kirtley, ML; Morse, SJ; Moreno Diaz, BA; Kim, MP; Feng, N; Lopez, AM; Guerrero, PA; Paradiso, F; Sugimoto, H; Arian, KA; Ying, H; Barekatain, Y; Sthanam, LK; Kelly, PJ; Maitra, A; Heffernan, TP; Kalluri, R. KRASG12D inhibition reprograms the microenvironment of early and advanced pancreatic cancer to promote FAS-mediated killing by CD8+ T cells. Cancer Cell 2023, 41(9), 1606–1620.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malaguti, M; Nistor, PA; Blin, G; Pegg, A; Zhou, X; Lowell, S. Bone morphogenic protein signalling suppresses differentiation of pluripotent cells by maintaining expression of E-Cadherin. Elife 2013, 2, e01197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maman, S; Witz, IP. A history of exploring cancer in context. Nat Rev Cancer 2018, 18(6), 359–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez Arias, A; Steventon, B. On the nature and function of organizers. Development 2018, 145(5), dev159525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrail, K; González-Sánchez, E; Granado-Martínez, P; Orsenigo, R; Ding, Y; Ferrer, B; Hernández-Losa, J; Ortega, I; Martín-Caballero, J; Muñoz-Couselo, E; García-Patos, V; Recio, JA. Loss of Lkb1 cooperates with BrafV600E and ultraviolet radiation, increasing melanoma multiplicity and neural-like dedifferentiation. Mol Oncol 2025, 19(2), 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meacham, CE; Morrison, SJ. Tumour heterogeneity and cancer cell plasticity. Nature 2013, 501(7467), 328–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlo, LM; Pepper, JW; Reid, BJ; Maley, CC. Cancer as an evolutionary and ecological process. Nat Rev Cancer 2006, 6(12), 924–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyers, EA; Kessler, JA. TGF-β Family Signaling in Neural and Neuronal Differentiation, Development, and Function. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2017, 9(8), a022244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, DM; Thomas, SD; Islam, A; Muench, D; Sedoris, K. c-Myc and cancer metabolism. Clin Cancer Res 2012, 18(20), 5546–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mintz, B; Illmensee, K. Normal genetically mosaic mice produced from malignant teratocarcinoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1975, 72(9), 3585–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorman, A; Benitez, EK; Cambulli, F; Jiang, Q; Mahmoud, A; Lumish, M; Hartner, S; Balkaran, S; Bermeo, J; Asawa, S; Firat, C; Saxena, A; Wu, F; Luthra, A; Burdziak, C; Xie, Y; Sgambati, V; Luckett, K; Li, Y; Yi, Z; Masilionis, I; Soares, K; Pappou, E; Yaeger, R; Kingham, TP; Jarnagin, W; Paty, PB; Weiser, MR; Mazutis, L; D'Angelica, M; Shia, J; Garcia-Aguilar, J; Nawy, T; Hollmann, TJ; Chaligné, R; Sanchez-Vega, F; Sharma, R; Pe'er, D; Ganesh, K. Progressive plasticity during colorectal cancer metastasis. Nature 2025, 637(8047), 947–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Sanjuán, I; Brivanlou, AH. Neural induction, the default model and embryonic stem cells. Nat Rev Neurosci 2002, 3(4), 271–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakanishi, Y; Seno, H; Fukuoka, A; Ueo, T; Yamaga, Y; Maruno, T; Nakanishi, N; Kanda, K; Komekado, H; Kawada, M; Isomura, A; Kawada, K; Sakai, Y; Yanagita, M; Kageyama, R; Kawaguchi, Y; Taketo, MM; Yonehara, S; Chiba, T. Dclk1 distinguishes between tumor and normal stem cells in the intestine. Nat Genet 2013, 45(1), 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicoglou, A. Waddington's epigenetics or the pictorial meetings of development and genetics. Hist Philos Life Sci 2018, 40(4), 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, S; Chang, C. Regulation of early Xenopus development by ErbB signaling. Dev Dyn 2006, 235(2), 301–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieto, MA; Huang, RY; Jackson, RA; Thiery, JP. EMT: 2016. Cell 2016, 166(1), 21–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nylund, P; Atienza Párraga, A; Haglöf, J; De Bruyne, E; Menu, E; Garrido-Zabala, B; Ma, A; Jin, J; Öberg, F; Vanderkerken, K; Kalushkova, A; Jernberg-Wiklund, H. A distinct metabolic response characterizes sensitivity to EZH2 inhibition in multiple myeloma. Cell Death Dis 2021, 12(2), 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ougolkov, AV; Bilim, VN; Billadeau, DD. Regulation of pancreatic tumor cell proliferation and chemoresistance by the histone methyltransferase enhancer of zeste homologue 2. Clin Cancer Res 2008, 14(21), 6790–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozair, MZ; Kintner, C; Brivanlou, AH. Neural induction and early patterning in vertebrates. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol 2013, 2(4), 479–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozaki, M; Iwanami, A; Nagoshi, N; Kohyama, J; Itakura, G; Iwai, H; Nishimura, S; Nishiyama, Y; Kawabata, S; Sugai, K; Iida, T; Matsubayashi, K; Isoda, M; Kashiwagi, R; Toyama, Y; Matsumoto, M; Okano, H; Nakamura, M. Evaluation of the immunogenicity of human iPS cell-derived neural stem/progenitor cells in vitro. Stem Cell Res 2017, 19, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pajanoja, C; Hsin, J; Olinger, B; Schiffmacher, A; Yazejian, R; Abrams, S; Dapkunas, A; Zainul, Z; Doyle, AD; Martin, D; Kerosuo, L. Maintenance of pluripotency-like signature in the entire ectoderm leads to neural crest stem cell potential. Nat Commun 2023, 14(1), 5941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaioannou, VE; McBurney, MW; Gardner, RL; Evans, MJ. Fate of teratocarcinoma cells injected into early mouse embryos. Nature 1975, 258(5530), 70–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascual, G; Domínguez, D; Elosúa-Bayes, M; Beckedorff, F; Laudanna, C; Bigas, C; Douillet, D; Greco, C; Symeonidi, A; Hernández, I; Gil, SR; Prats, N; Bescós, C; Shiekhattar, R; Amit, M; Heyn, H; Shilatifard, A; Benitah, SA. Dietary palmitic acid promotes a prometastatic memory via Schwann cells. Nature 2021, 599(7885), 485–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, SE; Loring, JF. Genomic instability in pluripotent stem cells: implications for clinical applications. J Biol Chem 2014, 289(8), 4578–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, GB; Wallace, C. Differentiation of malignant to benign cells. Cancer Res 1971, 31(2), 127–34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pla, P; Monsoro-Burq, AH. The neural border: Induction, specification and maturation of the territory that generates neural crest cells. Dev Biol 2018, 444 Suppl 1, S36–S46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podesta, AH; Mullins, J; Pierce, GB; Wells, RS. The neurula stage mouse embryo in control of neuroblastoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1984, 81(23), 7608–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raymond, JH; Aktary, Z; Pouteaux, M; Petit, V; Luciani, F; Wehbe, M; Gizzi, P; Bourban, C; Decaudin, D; Nemati, F; Martianov, I; Davidson, I; Tomasetto, CL; White, RM; Mahuteau-Betzer, F; Vergier, B; Larue, L; Delmas, V. Targeting GRPR for sex hormone-dependent cancer after loss of E-cadherin. Nature 2025, 643(8072), 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, H. Cancer as a dynamic developmental disorder. Cancer Res 1985, 45(7), 2935–42. [Google Scholar]

- Ricci-Vitiani, L; Lombardi, DG; Pilozzi, E; Biffoni, M; Todaro, M; Peschle, C; De Maria, R. Identification and expansion of human colon-cancer-initiating cells. Nature 2007, 445(7123), 111–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahakyan, AB; Balasubramanian, S. Long genes and genes with multiple splice variants are enriched in pathways linked to cancer and other multigenic diseases. BMC Genomics 2016, 17, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Escabillas, DJ; Hoffman, MT; Brender, SM; Moore, JS; Wen, HJ; Benitz, S; Davis, ET; Long, D; Wombwell, AM; Chianis, ERD; Allen-Petersen, BL; Steele, NG; Sears, RC; Matsumoto, I; DelGiorno, KE; Crawford, HC. Tuft cells transdifferentiate to neural-like progenitor cells in the progression of pancreatic cancer. Dev Cell 2025, 60(6), 837–852.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambasivan, R; Steventon, B. Neuromesodermal Progenitors: A Basis for Robust Axial Patterning in Development and Evolution. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 8, 607516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasai, Y; Lu, B; Steinbeisser, H; Geissert, D; Gont, LK; De Robertis, EM. Xenopus chordin: a novel dorsalizing factor activated by organizer-specific homeobox genes. Cell 1994, 79(5), 779–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satijn, DP; Hamer, KM; den Blaauwen, J; Otte, AP. The polycomb group protein EED interacts with YY1, and both proteins induce neural tissue in Xenopus embryos. Mol Cell Biol 2001, 21(4), 1360–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, SM; Sargent, TD. Development of neural inducing capacity in dissociated Xenopus embryos. Dev Biol 1989, 134(1), 263–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selleck, MA; Bronner-Fraser, M. Origins of the avian neural crest: the role of neural plate-epidermal interactions. Development 1995, 121(2), 525–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Q; Chen, Y; Li, Y; Qin, S; Yang, Y; Gao, Y; Zhu, L; Wang, D; Zhang, Z. Cross-tissue multicellular coordination and its rewiring in cancer. Nature 2025, 643(8071), 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, WC; Harland, RM. Expression cloning of noggin, a new dorsalizing factor localized to the Spemann organizer in Xenopus embryos. Cell 1992, 70(5), 829–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smukler, SR; Runciman, SB; Xu, S; van der Kooy, D. Embryonic stem cells assume a primitive neural stem cell fate in the absence of extrinsic influences. J Cell Biol 2006, 172(1), 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sogabe, S; Hatleberg, WL; Kocot, KM; Say, TE; Stoupin, D; Roper, KE; Fernandez-Valverde, SL; Degnan, SM; Degnan, BM. Pluripotency and the origin of animal multicellularity. Nature 2019, 570(7762), 519–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solter, D. From teratocarcinomas to embryonic stem cells and beyond: a history of embryonic stem cell research. Nat Rev Genet 2006, 7(4), 319–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosa, EA; Moriyama, Y; Ding, Y; Tejeda-Muñoz, N; Colozza, G; De Robertis, EM. Transcriptome analysis of regeneration during Xenopus laevis experimental twinning. Int J Dev Biol 2019, 63(6-7), 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, AM; Sonnenschein, C. Emergentism as a default: cancer as a problem of tissue organization. J Biosci 2005, 30(1), 103–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southall, TD; Davidson, CM; Miller, C; Carr, A; Brand, AH. Dedifferentiation of neurons precedes tumor formation in Lola mutants. Dev Cell 2014, 28(6), 685–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spemann, H. Embryonic development and induction”; New Haven; Yale University Press, 1938; p. 401. [Google Scholar]

- Spemann, H.; Mangold, H. Induction of embryonic primordia by implantation of organizers from a different species. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2001, 45, 13–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spemann, H.; Mangold, H. Über Induktion von Embryonalanlagen durch, Implantation artfremder Organisatoren. Arch. Mikrosk. Anat. EntwMech. 1924, 100, 599–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spranger, S; Bao, R; Gajewski, TF. Melanoma-intrinsic β-catenin signalling prevents anti-tumour immunity. Nature 2015, 523(7559), 231–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, M; Simakov, O; Chapman, J; Fahey, B; Gauthier, ME; Mitros, T; Richards, GS; Conaco, C; Dacre, M; Hellsten, U; Larroux, C; Putnam, NH; Stanke, M; Adamska, M; Darling, A; Degnan, SM; Oakley, TH; Plachetzki, DC; Zhai, Y; Adamski, M; Calcino, A; Cummins, SF; Goodstein, DM; Harris, C; Jackson, DJ; Leys, SP; Shu, S; Woodcroft, BJ; Vervoort, M; Kosik, KS; Manning, G; Degnan, BM; Rokhsar, DS. The Amphimedon queenslandica genome and the evolution of animal complexity. Nature 2010, 466(7307), 720–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanger, BZ; Wahl, GM. Cancer as a Disease of Development Gone Awry. Annu Rev Pathol 2024, 19, 397–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanton, C; Bernard, E; Abbosh, C; André, F; Auwerx, J; Balmain, A; Bar-Sagi, D; Bernards, R; Bullman, S; DeGregori, J; Elliott, C; Erez, A; Evan, G; Febbraio, MA; Hidalgo, A; Jamal-Hanjani, M; Joyce, JA; Kaiser, M; Lamia, K; Locasale, JW; Loi, S; Malanchi, I; Merad, M; Musgrave, K; Patel, KJ; Quezada, S; Wargo, JA; Weeraratna, A; White, E; Winkler, F; Wood, JN; Vousden, KH; Hanahan, D. Embracing cancer complexity: Hallmarks of systemic disease. Cell 2024, 187(7), 1589–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanabe, S. Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition and Cancer Stem Cells. Adv Exp Med Biol 2022, 1393, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Threadgill, DW; Dlugosz, AA; Hansen, LA; Tennenbaum, T; Lichti, U; Yee, D; LaMantia, C; Mourton, T; Herrup, K; Harris, RC; et al. Targeted disruption of mouse EGF receptor: effect of genetic background on mutant phenotype. Science 1995, 269(5221), 230–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y; Gao, WQ; Liu, Y. Metabolic heterogeneity in cancer: An overview and therapeutic implications. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer 2020, 1874(2), 188421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigos, AS; Pearson, RB; Papenfuss, AT; Goode, DL. Altered interactions between unicellular and multicellular genes drive hallmarks of transformation in a diverse range of solid tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017, 114(24), 6406–6411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigos, AS; Pearson, RB; Papenfuss, AT; Goode, DL. How the evolution of multicellularity set the stage for cancer. Br J Cancer 2018, 118(2), 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tropepe, V; Hitoshi, S; Sirard, C; Mak, TW; Rossant, J; van der Kooy, D. Direct neural fate specification from embryonic stem cells: a primitive mammalian neural stem cell stage acquired through a default mechanism. Neuron 2001, 30(1), 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turajlic, S; Sottoriva, A; Graham, T; Swanton, C. Resolving genetic heterogeneity in cancer. Nat Rev Genet 2019, 20(7), 404–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varela, C; Denis, JA; Polentes, J; Feyeux, M; Aubert, S; Champon, B; Piétu, G; Peschanski, M; Lefort, N. Recurrent genomic instability of chromosome 1q in neural derivatives of human embryonic stem cells. J Clin Invest 2012, 122(2), 569–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermeulen, L; Todaro, M; de Sousa Mello, F; Sprick, MR; Kemper, K; Perez Alea, M; Richel, DJ; Stassi, G; Medema, JP. Single-cell cloning of colon cancer stem cells reveals a multi-lineage differentiation capacity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008, 105(36), 13427–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinogradov, AE; Anatskaya, OV. Cell dedifferentiation "versus "evolutionary reversal "theories of cancer: The direct contest of transcriptomic features. Int J Cancer 2025, 156(9), 1802–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelstein, B; Kinzler, KW. The multistep nature of cancer. Trends Genet 1993, 9(4), 138–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watterson, A; Coelho, MA. Cancer immune evasion through KRAS and PD-L1 and potential therapeutic interventions. Cell Commun Signal 2023, 21(1), 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, CG; Gootwine, E; Sachs, L. Developmental potential of myeloid leukemia cells injected into midgestation embryos. Dev Biol 1984, 101(1), 221–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, RS; Miotto, KA. Widespread inhibition of neuroblastoma cells in the 13-to 17-day-old mouse embryo. Cancer Res 1986, 46 4 Pt 1, 1659–62. [Google Scholar]

- Woltjen, K; Stanford, WL. Inhibition of Tgf-beta signaling improves mouse fibroblast reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell 2009, 5(5), 457–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, X; Zhong, J; Biermann, J; Duan, H; Zhang, X; Shi, Y; Gao, Y; He, K; Zhai, D; Luo, F; Lai, Y; Xiao, F; Wang, W; Wang, M; Xu, J; Liu, H; Tang, J; Chu, L; Chen, T; D'Souza, EK; Caprio, L; Ebel, L; Biswas, D; Cottarelli, A; Mou, Y; Izar, B; Zhang, N; Bai, F. Pan-cancer human brain metastases atlas at single-cell resolution. Cancer Cell 2025, S1535-6108(25)00126-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L; Zhang, M; Shi, L; Yang, X; Chen, L; Cao, N; Lei, A; Cao, Y. Neural stemness contributes to cell tumorigenicity. Cell Biosci 2021, 11(1), 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X; Liu, X; Dollar, JJ; Liu, X; Jasani, N; Posorske, B; Sriramareddy, SN; Jarajapu, V; Kuznetsoff, JN; Sinard, J; Bennett, RL; Licht, JD; Smalley, KSM; Harbour, JW; Yu, X; Karreth, FA. A multi-step immune-competent genetic mouse model reveals phenotypic plasticity in uveal melanoma. bioRxiv [Preprint] 2025, 2025.06.04.657841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J; Antin, P; Berx, G; Blanpain, C; Brabletz, T; Bronner, M; Campbell, K; Cano, A; Casanova, J; Christofori, G; Dedhar, S; Derynck, R; Ford, HL; Fuxe, J; García de Herreros, A; Goodall, GJ; Hadjantonakis, AK; Huang, RYJ; Kalcheim, C; Kalluri, R; Kang, Y; Khew-Goodall, Y; Levine, H; Liu, J; Longmore, GD; Mani, SA; Massagué, J; Mayor, R; McClay, D; Mostov, KE; Newgreen, DF; Nieto, MA; Puisieux, A; Runyan, R; Savagner, P; Stanger, B; Stemmler, MP; Takahashi, Y; Takeichi, M; Theveneau, E; Thiery, JP; Thompson, EW; Weinberg, RA; Williams, ED; Xing, J; Zhou, BP; Sheng, G; EMT International Association (TEMTIA). Guidelines and definitions for research on epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2020, 21(6), 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X; Cao, N; Chen, L; Liu, L; Zhang, M; Cao, Y. Suppression of Cell Tumorigenicity by Non-neural Pro-differentiation Factors via Inhibition of Neural Property in Tumorigenic Cells. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9, 714383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ying, QL; Nichols, J; Chambers, I; Smith, A. BMP induction of Id proteins suppresses differentiation and sustains embryonic stem cell self-renewal in collaboration with STAT3. Cell 2003, 115(3), 281–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zalc, A; Sinha, R; Gulati, GS; Wesche, DJ; Daszczuk, P; Swigut, T; Weissman, IL; Wysocka, J. Reactivation of the pluripotency program precedes formation of the cranial neural crest. Science 2021, 371(6529), eabb4776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M; Liu, Y; Shi, L; Fang, L; Xu, L; Cao, Y. Neural stemness unifies cell tumorigenicity and pluripotent differentiation potential. J Biol Chem 2022, 298(7), 102106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z; Lei, A; Xu, L; Chen, L; Chen, Y; Zhang, X; Gao, Y; Yang, X; Zhang, M; Cao, Y. Similarity in gene-regulatory networks suggests that cancer cells share characteristics of embryonic neural cells. J Biol Chem 2017, 292(31), 12842–12859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X; Boyer, L; Jin, M; Mertens, J; Kim, Y; Ma, L; Ma, L; Hamm, M; Gage, FH; Hunter, T. Metabolic reprogramming during neuronal differentiation from aerobic glycolysis to neuronal oxidative phosphorylation. Elife 2016, 5, e13374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L; Mudianto, T; Ma, X; Riley, R; Uppaluri, R. Targeting EZH2 Enhances Antigen Presentation, Antitumor Immunity, and Circumvents Anti-PD-1 Resistance in Head and Neck Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2020, 26(1), 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerli, D; Brambillasca, CS; Talens, F; Bhin, J; Linstra, R; Romanens, L; Bhattacharya, A; Joosten, SEP; Da Silva, AM; Padrao, N; Wellenstein, MD; Kersten, K; de Boo, M; Roorda, M; Henneman, L; de Bruijn, R; Annunziato, S; van der Burg, E; Drenth, AP; Lutz, C; Endres, T; van de Ven, M; Eilers, M; Wessels, L; de Visser, KE; Zwart, W; Fehrmann, RSN; van Vugt, MATM; Jonkers, J. MYC promotes immune-suppression in triple-negative breast cancer via inhibition of interferon signaling. Nat Commun 2022, 13(1), 6579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermannova, O; Ferreira, AG; Ascic, E; Velasco Santiago, M; Kurochkin, I; Hansen, M; Met, Ö; Caiado, I; Shapiro, IE; Michaux, J; Humbert, M; Soto-Cabrera, D; Benonisson, H; Silvério-Alves, R; Gomez-Jimenez, D; Bernardo, C; Bauden, M; Andersson, R; Höglund, M; Miharada, K; Nakamura, Y; Hugues, S; Greiff, L; Lindstedt, M; Rosa, FF; Pires, CF; Bassani-Sternberg, M; Svane, IM; Pereira, CF. Restoring tumor immunogenicity with dendritic cell reprogramming. Sci Immunol 2023, 8(85), eadd4817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zingg, D; Debbache, J; Schaefer, SM; Tuncer, E; Frommel, SC; Cheng, P; Arenas-Ramirez, N; Haeusel, J; Zhang, Y; Bonalli, M; McCabe, MT; Creasy, CL; Levesque, MP; Boyman, O; Santoro, R; Shakhova, O; Dummer, R; Sommer, L. The epigenetic modifier EZH2 controls melanoma growth and metastasis through silencing of distinct tumour suppressors. Nat Commun 2015, 6, 6051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zylka, MJ; Simon, JM; Philpot, BD. Gene length matters in neurons. Neuron 2015, 86(2), 353–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Neural stem/progenitor cells (References) | Cancer cells (References) | Pluripotent stem cell (PSCs) (References) |

| Tumorigenic (Xu et al., 2021) | Tumorigenic | Tumorigenic (Ben-David and Benvenisty, 2011) |

| Migratory | Migratory | Migratory |

| Immune privileged (Hori et al., 2003; Itakura et al., 2017; Ozaki et al., 2017) | Immune privileged | Immune privileged (Drukker et al., 2006; Fändrich et al., 2002; Magliocca et al., 2006;) |

| Defined by ancestral regulatory networks (Domazet-Loso et al., 2007; Xu et al., 2021) | Dependent on activation of ancestral regulatory networks (Bussey et al., 2017; Domazet-Loso and Tautz, 2010; Trigos et al., 2017; Trigos et al., 2018) | Unknown |

| Neural stemness | Neural stemness (Cao, 2017; Cao, 2022; Chen et al., 2021; Lei et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2022) | Neural stemness as the default state of PSC (Malaguti et al., 2013; Muñoz-Sanjuán and Brivanlou, 2002; Smukler et al., 2006; Tropepe et al., 2001; Ying et al., 2003) |

| Pluripotent differentiation potential (Clarke et al., 2000; Tropepe et al., 2001; Xu et al., 2021) | Pluripotent differentiation potential (Mintz and Illmensee, 1975; Papaioannou et al., 1975; Xu et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2022) | Pluripotent differentiation potential |

| Characteristic of aerobic glycolysis. Differentiation into neurons decreases glycolysis (Kim et al., 2014; Zheng et al., 2016) | Characteristic of aerobic glycolysis | Characteristic of aerobic glycolysis. Turning into NSCs does not change or increases glycolysis; differentiation into mesoderm and endoderm decreases glycolysis (Intlekofer and Finley, 2019; Zheng et al., 2016) |

| Unicellular origin (Cao, 2022; Xu et al., 2021) | Resulting from loss of original cell identity and acquirement of neural stemness, and reverse evolution from multicellular to unicellular state (Alfarouk et al., 2011; Anatskaya et al., 2020; Bussey et al., 2017; Cao, 2022; Chen et al., 2015; Vinogradov and Anatskaya, 2025; Xu et al., 2021) | Unicellular origin of pluripotency (Sogabe et al., 2019) |

| Prone to genomic instability (Varela et al., 2012) | Genomic instability | Prone to genomic instability (Peterson and Loring, 2014) |

| Enriched in long genes with more splice variants (Gabel et al., 2015; Xu et al., 2021; Zylka et al., 2015) | Enriched in long genes with more splice variants (Sahakyan and Balasubramanian, 2016) | Unknown |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).