1. Introduction

The Early Jurassic, particularly the Hettangian and Sinemurian, spanning from 201.4 to 192.9 Ma [

1], records the recovery and evolution of ecosystems following the End-Triassic biotic crisis, one of the so-called major mass extinction events of the Phanerozoic [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. The supercontinent Pangea, which began to fragment during the Triassic, continued to separate throughout the Jurassic [

11]. However, the close proximity of all the corresponding present-day continents implies that floras and faunas shared many common biological properties. Reconstructed high atmospheric CO

2 levels [

12,

13], the presence of vegetation at high latitudes, and a general lack of evidence for polar ice sheets suggest that warm and more or less humid climates extended to high latitudes [

14].

The Early Jurassic was a time of significant evolutionary change and diversification [

15]. On land, it was characterised by the dominance of gymnosperms, including conifers, cycads and ginkgos ([

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. These plants formed extensive forests that supported diverse terrestrial ecosystems. Indeed, for example, the evolution of early dinosaurs continued, with notable groups such as coelophysid and ceratosaurian theropods, basal sauropodomorphs and thyreophoran ornithischians diversifying and occupying different ecological niches [

18,

19,

20]. This period set the stage for the later dominance of dinosaurs in the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods [

21]. Mammal-like reptiles (synapsids) and early true mammals were also present, although they remained relatively small and ecologically subordinate to the dinosaurs [

22,

23,

24,

25].

In the oceans, several new biological groups also emerged and diversified during this time. These groups were mainly scleractinian corals, foraminifera, radiolarians, psiloceratoid ammonites, ray-finned fish and marine reptiles [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]). The latter include giant predators such as ichthyosaurs, plesiosaurs and pliosaurs, whose homeothermy and endothermy are still the subject of intense physiological, ecological and geochemical research [

33,

34,

35,

36]. Among the bivalves and gastropods, the oyster-like genus

Gryphaea, also known as “Devil’s Toenails” in the British folklore, was particularly abundant and serves sometimes as an index fossil for the Lower Jurassic along with ammonites [

37,

38,

39]. Specifically,

Gryphaea arcuata was a benthic organism that lived on the seafloor in shallow warm temperate marine environments [

40,

41]. Those bivalves thrived in the epicontinental seas that covered much of present-day Europe and parts of North America (

Figure 1). These seas were characterised by warm to cool temperatures, moderate to low energy environments and muddy to sandy substrates, providing suitable conditions for

Gryphaea arcuata ([

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43].

In the context of a Pangea that was just beginning to break up, the sedimentary marine deposits of western Europe (

Figure 2) record the influence of both the Tethys (warm) and the Boreal (cool) domains [

44]. The climatic context is therefore a crucial key to understanding the radiation of the marine species described above. It is important to mention that many temperature constructions have been made for the Jurassic and as far back as the Plienbaschian. However, only a few data are available for the Hettangian and the Sinemurian according to a compilation by [

45], which represent the Early Jurassic immediately following the Triassic-Jurassic boundary. These marine temperatures, mostly between 15°C and 20°C, have been inferred from the oxygen isotope composition of a few teeth of demersal and pelagic fishes,

Gryphaea sp., oysters and belemnites [

40,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49]. These marine temperatures appear to be much lower than those inferred from the early Plienbaschian and early Toarcian marine sediments [

45]. Thus, the addition of more marine temperature data is crucial to understand whether or not the documented biological radiation took place in the context of gently warm Jurassic climate dynamics.

We therefore studied 75 invertebrate samples including 53 specimens of

Gryphaea arcuata and 22 specimens of coexisting bivalves (11

Chlamys sp., 4

Plagiostoma sp. and 7

Pseudolimea sp.) from the Sinemurian (199.4 to 192.9 Ma; [

1]) calcareous and marly marine sediments of the Fresville quarry (Cotentin Peninsula, Normandy, France). The co-occurrence of

Arietites bucklandi (Sowerby 1818) and

Gryphaea arcuata allowed this ammonite and this bivalve to be used as index fossils for dating these strata. Consequently, the sedimentary column is thus known to represent the basal Early Sinemurian covering a period of about 1.3 My [

50].

The aim of our study is to evaluate the potential diagenesis of the fossils studied, the marine productivity of the water column in which they lived, and changes in seawater temperature. Our objectives will be achieved by determining and interpreting the stable carbon and oxygen isotope compositions of the bivalves together with their Sr and Mg contents. Temperature values and their changes will be discussed in relation to the oxygen isotope composition of Early Jurassic seawater, the paleogeography of Western Europe, lithology, faunal assemblages and the particular ecology of Gryphaea arcuata.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Geological Setting

At the beginning of the Jurassic, Pangea split to form several continental plates in response to a period of long-term extension [

51,

52]. A second-order transgression begins in the early Jurassic and continues until the middle of the Toarcian, with a change in the sedimentary regime [

50,

53]. A third-order transgression characterises the Early Sinemurian [

50]. During the Sinemurian, the Fresville region was located at the edge of the carbonate platform at a palaeolatitude of around 35°-36°N after [

54]) or around 31°-32°N after [

55] (

Figure 2). The transgression allowed the sea to invade the Fresville region from the eastern part of the platform, i.e. from the eastern edge of the Armorican massif [

56]. This region constituted a vast gulf of the early Jurassic sea bordering the Armorican continent involving a calm sea with a muddy bottom and influences from the open sea [

57].

Figure 2.

Paleogeographic map of western Europe during the Sinemurian with the location of Fresville in northwestern Normandy, France. After [

55]. Blue arrows: low-saline and cool southward currents; grey: land masses; dark grey: fluviatile/lacustrine environments; light blue: shallow marine environments; deep blue: deep epicontinental seas; dark blue: deep oceanic basin.

Figure 2.

Paleogeographic map of western Europe during the Sinemurian with the location of Fresville in northwestern Normandy, France. After [

55]. Blue arrows: low-saline and cool southward currents; grey: land masses; dark grey: fluviatile/lacustrine environments; light blue: shallow marine environments; deep blue: deep epicontinental seas; dark blue: deep oceanic basin.

The Fresville quarry is located in northwestern France, more specifically in the Cotentin Peninsula, department Manche, Normandy. This former limestone quarry, used for cement production until 1984, described in detail by [

56], is located at “le Goulet”. It features a marl-limestone alternation belonging to the Early Sinemurian (

Figure 3). This geological formation on this site rests on the Hettangian. Above this formation is a palaeosol of the same age as well as a detrital formation consisting of Cenomanian orbitoline sands. The change in lithology and the absence of Middle and Upper Jurassic deposits highlight variations in sea level and periods of emersion. The marl-limestone alternation can be seen over a height of around 20 m and contains an abundant and diverse [

56] of marine invertebrates, as well as shark [

57] and ichthyosaur remains, ichnofossils and plant remains.

Figure 3.

Lower Sinemurian outcrops in the Fresville quarry, Normandy, France, highlighting the marine stratigraphic sequence with the numbering of alternating limestone, marly limestone and marl layers. See also

Table 1.

Figure 3.

Lower Sinemurian outcrops in the Fresville quarry, Normandy, France, highlighting the marine stratigraphic sequence with the numbering of alternating limestone, marly limestone and marl layers. See also

Table 1.

Table 1.

Stratigraphy, lithology, taxonomy, stable isotope ratios and trace element contents of the mollusc shells collected from the lower Sinemurian of Fresville, Normandy, France.

Table 1.

Stratigraphy, lithology, taxonomy, stable isotope ratios and trace element contents of the mollusc shells collected from the lower Sinemurian of Fresville, Normandy, France.

The outcrop is bounded by two faults. The first is the result of an extensive tectonic regime during the breaking of Pangea in the Middle and Upper Jurassic. The second is the result of a compressional phase of Alpine age [

1]. From a lithological point of view, the marl-limestone formation observed is characterized by a little variation in the content of clay minerals, which are illite and kaolinite. Biomicritic clayey limestone is characterised by a calcium carbonate content of less than 40 wt%. The difference between clayey limestone and marl depends on the calcium carbonate (CaCO

3) content, the limit of which corresponds to a content of 35 wt%. The outcrop has a monoclinal structure with a gentle slope of 3° to 5° to the south-east, attributed to subsidence [

58].

In order to study the Early Sinemurian marine paleoenvironment recorded in the Fresville sedimentary sequence, the study was carried out in the south-eastern part of the quarry at geographical coordinates: N49°26’23.06 – W1°22’52.82’’ (

Figure 3). The study material was collected in the lower part of the quarry, at an altitude of around 13 m above sea level. This part forms the first step of the quarry and constitutes the base of the Sinemurian [

59]. The first step consists of alternating marly limestones and pyritic bluish-grey marls in the

Bucklandi biozone covering the period comprised between 199.3 and 198 Ma, according to [

50]. This biozone represents the first ammonite zone of the Sinemurian covering the period 199.3 Ma to 190.8 Ma [

1], which is also characterized by the presence of

Gryphaea arcuata while

Gryphaea obliquata is always absent.

At the time of our collecting visit, two sections were sampled: the lower part comprising layers 1 to 24 with a total thickness of 2.85 m and the upper part comprising layers 33 to 35 with a total thickness of 43 cm. These two lithological sections were separated by approximately 100 cm of outcrop, which was inaccessible for sampling due to the presence of a significant vegetation cover (

Figure 3). For a detailed illustrated description of the sections currently visible in the Fresville quarry, see Desquesne (2023).

2.2. Sample Collection

The marine invertebrate fossil fauna found in the Fresville quarry is abundant (

Figure 4). It consists of bivalves (e.g.

Gryphaea arcuata,

Chlamys sp,

Plagiostoma sp), ammonites (

Arietites bucklandi), gastropods, echinoderms, arthropods and brachiopods (

Spiriferina walcotti); for a detailed illustrated list, see [

56]. The fossil specimens used in this study were collected with the help of members of the Club de Géologie du Cotentin.

In this study, we mainly focus on the species

Gryphaea arcuata whose low-Mg calcite shells [

60,

61,

62] constitute a valuable material for seawater temperature reconstructions based on geochemical proxies. Indeed, low-Mg calcite is less sensitive to diagenesis as its solubility in aqueous fluids is much lower than aragonite [

63,

64,

65,

66].

The genus

Gryphaea belongs to the Class Bivalvia, the Order Ostreida and Family Gryphaeidae. The chronostratigraphic distribution of

Gryphaea extends from the Jurassic to the Cretaceous [

1], and this genus was particularly abundant during the Sinemurian [

1]. During the Hettangian and Sinemurian, the paleogeographic domain of

Gryphaea extended between 33°N and 55°N latitude in western Europe [

40].

According to [

67] and [

68],

Gryphaea arcuata has an elongated, relatively thick, arched shell no more than 6 cm long. The hook is protruding and curved towards the upper valve. The shell of

G. arcuata is highly inequivalve, meaning the two valves differ significantly in size and shape. The larger left valve is convex and strongly curved, resembling a claw or a crescent, while the smaller right valve is flat or slightly concave, serving primarily as a lid. Growth lines and ridges are prominent on the surface of the valves, indicating shell growth rhythms through time.

Gryphaea arcuata was living in the warm temperate shallow marine environments (0 to 50 m depth; [

69]), fixed to the seabed, and feeding by filtering seawater [

40]. They are considered to only thrive in a euhaline environment ([

40]). Such marine environment with a normal salinity is suggested by the assemblage of invertebrate fauna that have been documented in the Fresville quarry:

Gryphaea arcuata, ammonites and brachiopods [

40].

2.3. Analytical Techniques

2.3.1. Sample Preparation

Samples were selected according to some recommendations given by [

66], including the use of sub-mature to adult part of the shells to avoid isotopic disequilibrium with ambient seawater during the fast growth of the shell [

70]. Careful examination of shell fragments obtained from smooth-textured shell surfaces was performed, then inspected under a binocular microscope. Only about two thirds of the collected samples in the field were kept for the cleaning protocol. Those selected samples underwent cleaning with double distilled water in an ultrasonic bath to remove marl particles from the shell without damaging it. To do this, each piece was placed in a beaker filled with distilled water, and the beaker was placed in the ultrasonic bath for 2 minutes. This step was repeated until the piece was completely clean. The second step was to take a shell sample from the surface by drilling the adult part close to the main growth axis using a Dremel™ equipped with a diamond-coated rotating head. The aliquots were finally ground to a powder (≈ 100 to 150 μm in size) in an agate mortar. The identification of the calcium carbonate polymorph was determined with Raman spectroscopy. Potential diagenesis has been discussed by interpreting the observed trends linking the δ

13C values (‰ VPDB), δ

18O values (‰ VPDB), Mg and Sr contents in ppm of low-Mg calcite shells.

2.3.2. Raman Spectroscopy

The Raman analyses were carried out at the Laboratoire de Géologie, École Normale Supérieure of Lyon. The Raman spectra of 58 samples were obtained during this study. Of these 58 samples, 56 bivalve samples, including 37 samples of Gryphaea arcuata, 7 Pseudolimea sp., 4 Plagiostoma sp. as well as 8 Chlamys sp distributed along the sedimentary sequence. Raman spectra were collected using a visible JY LabRam HR800 Raman spectrometer using a laser with a wavelength of 514.532 nm at ambient temperature and pressure. Each sample was measured at minima at one point. The spectra obtained cover the low and high frequencies, from 130 (130.071) to 1100 (1099.77) cm-1. The acquisition time was equal to two acquisitions of 5 seconds each.

2.3.3. Trace Elements

Measurements were performed at the Ecole Normale Supérieure de Lyon, France. Sr and Mg concentrations were obtained by dissolving about 10 mg of carbonate powder in 10 ml of HNO

3 2%. For all samples, pairs of aliquots were prepared with 10 times dilution along with a fixed amount of Scandium and Indium that were added to correct concentrations from instrument drift. Solutions were analysed using a quadrupole ICP-Mass Spectrometer (i-CAP-Q ICP-MS), for minor and trace elements, respectively. The reproducibility of measurements was assessed through the analysis of the carbonate standard CCH1 [

71].

2.3.4. Carbon and Oxygen Stable Isotopes

Measurements were performed at the “Laboratoire de Géologie de Lyon”, Université Claude Bernard, Lyon, France. Stable isotope ratios were determined by using an auto sampler MultiPrep

TM system coupled to a dual–inlet GV Isoprime

TM isotope ratio mass spectrometer (IRMS). Aliquot size was about 300 μg of calcium carbonate. All aliquots were reacted with anhydrous oversaturated phosphoric acid at 90°C during 20 minutes. Oxygen isotope ratios of calcium carbonate are computed assuming an acid fractionation factor 1000lnα(CO

2–CaCO

3) of 8.1 between carbon dioxide and calcite [

72]. All sample measurements were duplicated and adjusted to the international references NIST NBS18 (δ

18O

VPDB = -23.2‰; δ

13C

VPDB = -5.01‰) and NBS19 (δ

18O

VPDB = -2.20‰; δ

13C

VPDB = +1.95‰). External reproducibility is close to ±0.1‰ for δ

18O and ±0.05 for δ

13C (2σ).

3. Results

3.1. Raman Spectra

Raman analyses of the shells studied are given in

Table 1 and, for example, two spectra of Gryphaea arcuata are shown in

Figure 5. All bivalve shells are made of low-Mg calcite that was readily identified from the low frequency part of the spectra, and especially from the position and splitting of the symmetric bending mode which occurs as a single peak at 712 cm

-1 in calcite [

73]

. The peaks obtained at 156 cm

-1 and 282 cm

-1 are attributed to the translation and rotation mode known as the lattice mode [

74]. The strongest band for calcite, located at 1087 cm

-1, is an internal mode resulting from the symmetrical stretching of the carbonate ion, known as the stretching mode.

3.2. Sr and Mg Contents of Gryphaea arcuata and Other Associated Bivalves

Sr and Mg contents of Gryphaea arcuata range from 335 ppm to 6161 ppm and from 160 ppm to 2076 ppm, respectively (

Table 1). The distribution of both set of data does not follow a normal distribution according to a Shapiro-Wilk test (

Table 2). However, the data are statistically positively correlated according to a Spearman test (r = 0.572) which is adapted to data not following a normal distribution (

Table 3). The linear regression model highlights the presence of outliers for Sr (44124, 4318 and 6161 ppm) and for Mg (2076 ppm) that correspond to the highest contents measured in the sub-mature parts of the shells. A Mann-Whitney U test was also applied to the Sr and Mg values of Gryphaea arcuata depending on the mineralogy of the host sediment to investigate its possible influence of the isotope composition of the bivalve shells. The hypothesis H

0 stating similar quantitative distributions in marls-limestones and marls-marly limestones was thus verified for Sr contents with acceptable p-values of 0.523 and 0.786, respectively. The same hypothesis and groups were also verified for Mg contents with an acceptable p-value of 0.440 for marls-limestones while a very low p value of 0.062 is observed for marls-marly limestones, respectively. Sr and Mg contents of Chlamys (n = 11) range from 1197 ppm to 4666 ppm and from 576 ppm to 1629 ppm, respectively. Both variables are not significantly correlated according to a Spearman test (r = -0.158;

Table 4). The linear regression model highlights the presence of outliers for Sr (3232 and 4666 ppm). For the two remaining studied bivalves, the very restricted number of samples precludes the use of any kind of statistical test. Both bivalve genera exhibit large ranges of trace elements. Indeed, Sr and Mg contents of Pseudolimea (n = 7) range from 613 ppm to 4627 ppm and from 440 ppm to 1343 ppm, respectively, while those for Plagiostoma (n = 4) range from 335 ppm to 2000 ppm and from 160 ppm to 1070 ppm, respectively (

Table 5).

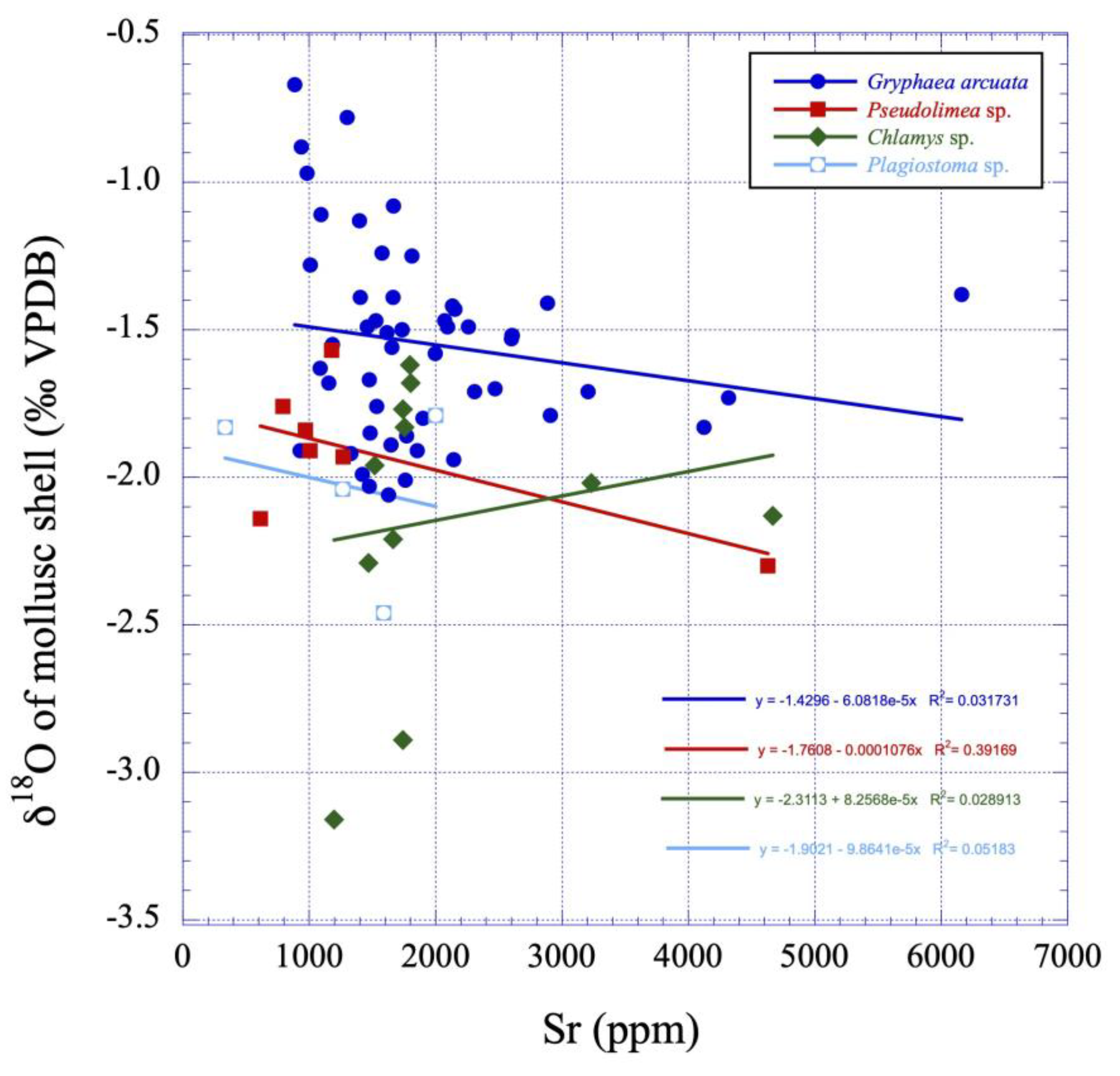

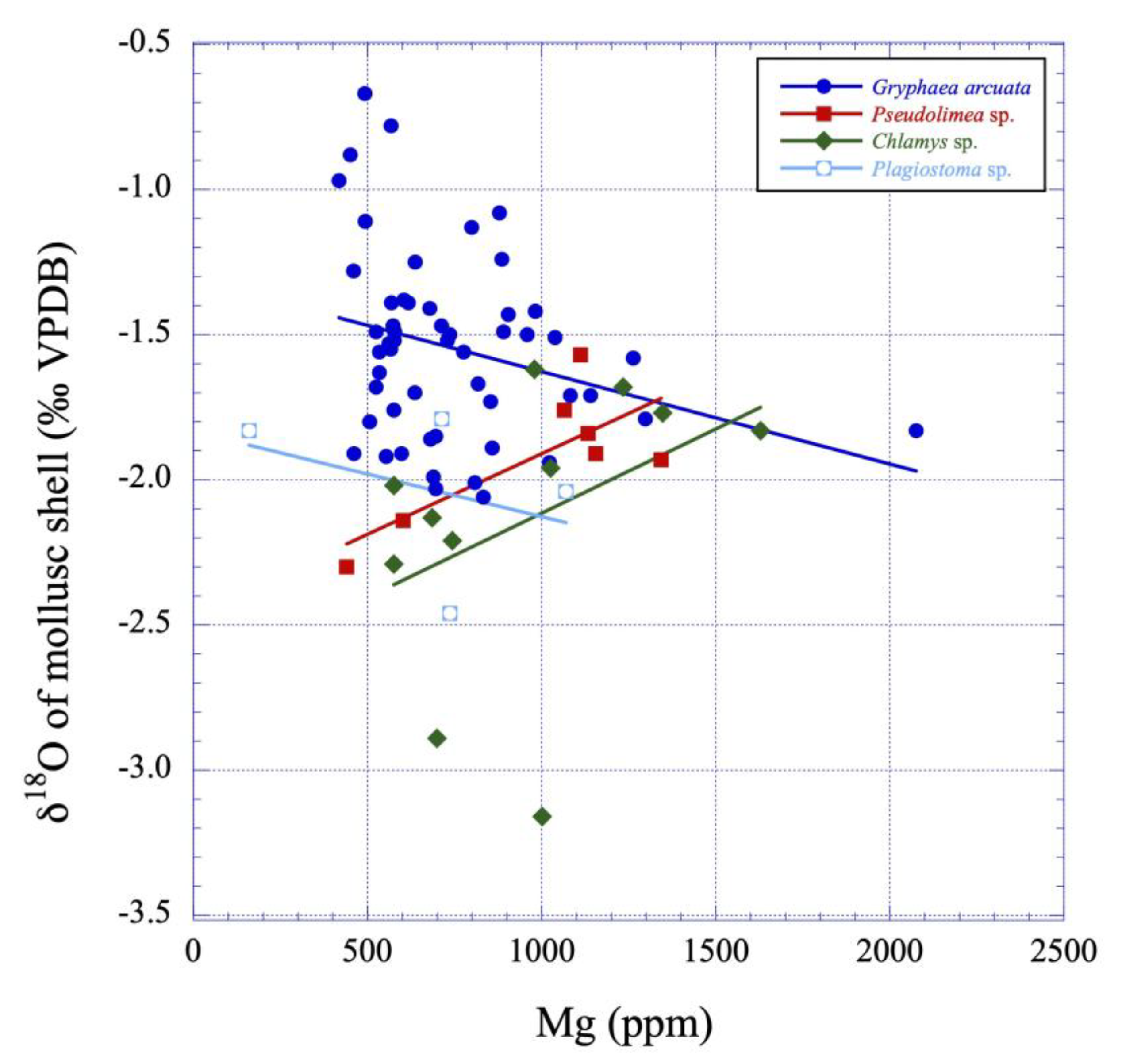

3.3. Carbon and Oxygen Isotope Ratios of Gryphaea arcuata and Other Associated Bivalves

Both δ

13C and δ

18O values for mollusc shells, especially Gryphaea arcuata, which was sampled throughout the sequence, show no significant temporal trend when plotted against the stratigraphic sequence, however, the lowest δ

18O values and the highest δ

13C values are located in the middle part of the sequence (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7). The dataset (

Table 1) for Gryphaea arcuata is characterized by δ

13C and δ

18O values ranging respectively from 0.57‰ to 3.79‰ (mean = 2.52±0.72‰) and -3.16 to -0.67‰ (mean = -1.72±0.43‰). A significant positive correlation between δ

13C and δ

18O is observed according to both Pearson and Spearman tests (

Table 3;

Figure 8). The statistical analysis of data also reveals that both δ

13C and δ

18O values follow a normal distribution after the removal of a few outliers (

Table 2). Indeed, two of the lowest values measured for δ

13C (0.64 and 0.84 ‰ VPDB) and two of the highest δ

18O (-0.78 and -0.67) appear as outliers in the regression linear model. Consequently, those values will not be considered further in the calculation of the living water of these bivalves. It is also worthy to note that both δ

13C and δ

18O values are not significantly correlated to either Sr or Mg contents (

Table 3;

Figure 9 and

Figure 10). Mann-Whitney U tests were also applied to the δ

13C and δ

18O values of Gryphaea arcuata depending on the mineralogy of the host sediment to investigate its possible influence on the isotopic composition of the bivalve shells. Mean values, generally close to each other, are reported in the

Table 5 depending on the lithologies that were distinguished as three groups: limestones, marly limestones and marls. The hypothesis H

0 stating similar quantitative distributions in marls-limestones and marls-marly limestones was thus verified for δ

18O values with acceptable p-values of 0.305 and 0.397, respectively. The same hypothesis and groups were also verified for δ

13C values with an acceptable p-value of 0.949 for marls-marly limestones while a very low p value of 0.082 is observed for marls-limestones, respectively. Both δ

13C and δ

18O values of Chlamys are not significantly correlated to either Sr or Mg contents (

Table 4;

Figure 9 and

Figure 10) but are significantly correlated between themselves (

Table 4;

Figure 8). For the two remaining studied bivalves, the very restricted number of samples precludes the use of any kind of statistical test. δ

13C and δ

18O values of Pseudolimea (n = 7) range from 1.39‰ ppm to 3.23‰ and from -2.30‰ to -1.57‰, respectively, while those for Plagiostoma (n = 4) range from 1.32‰ ppm to 2.22‰ and from -2.46‰ to -1.79‰, respectively (

Table 5).

4. Discussion

4.1. Paleoecology of Gryphaea arcuata

The paleoecology of Gryphaea arcuata can be summarized on the basis of previous studies published by [

40,

61,

67,

68,

75]. Gryphaea arcuata, commonly known as the “devil’s toenail,” is a well-studied fossil oyster from the Lower Jurassic. This species is particularly notable for its distinctive, curved shell shape. Indeed, Gryphaea arcuata is characterized by its asymmetrical, strongly curved shell with a prominent umbo. The left valve is larger and more convex, while the right valve is flatter and fits snugly into the left valve. These morphological features are adaptations to its sessile lifestyle, allowing it to anchor itself to the substrate in a stable manner. As a suspension feeder and benthic organism, Gryphaea arcuata filtered plankton and organic particles from the water column. This feeding strategy indicates that Gryphaea arcuata played a crucial role in the marine food web, contributing to the cycling of nutrients within its ecosystem.

Gryphaea arcuata, like many bivalves, lived in shallow marine environments characterized by euhaline waters and at depths most likely comprised between the limit of storm wave action (< 15 m) and the lower limit of the euphotic zone, comprised between 100 m and 200 m, depending on the seafloor topography and water turbidity. This bivalve thrived in the epicontinental seas that were characterized by relatively warm to subtropical temperatures. At the margins of the Tethys marine basin in western Europe, it has been documented in the latitude range 33°–50°N, restricted to moderate to low energy environments, and muddy to sandy substrates. [

40] estimated on the basis of the stable isotope ratios of their sub-mature shells that this bivalve lived in marine waters whose temperature was comprised between 14°C and 21°C.

[

40] shown that the modification of shape in Gryphaea arcuata was influenced by climatic conditions, nutrient availability and water oxygenation. Two distinct morphotypes have been identified, although it is possible that a continuum of forms exists, as intermediate forms have also been documented. The first environment, characterised by tropical temperatures and high relative humidity along with a nutrient-rich ecosystem, was colonised by slow-growing Gryphaea arcuata, which exhibited the following characteristics: small, wide and thin shells. The second environment was inhabited by Gryphaea arcuata, which exhibited long, large, thick, and narrow shells with a rapid growth rate. These shells were observed to thrive in a cooler environment that aligned with the optimal requirements for Gryphaea arcuata.

4.2. Diagenetic Alteration of the Studied Samples

All the bivalve shells initially composed of aragonite were transformed into calcite, clearly demonstrating the action of diagenetic processes that may have deeply modified their geochemical composition following deposition. Indeed, despite a lower number of analysed samples relative to

Gryphaea, they exhibit lower minimal, mean and maximal δ

18O values (

Table 5). In the case of Sr contents, only

Plagiostoma and

Pseudolimea show lower contents than

Gryphaea. The trace element compositions and stable isotope ratios of these samples will therefore not be considered as potential proxies for their marine palaeoenvironment. Moreover, interpreting such lower δ

18O values would lead to the calculation of overestimated marine temperatures [

76,

77,

78,

79].

Gryphaea arcuata, which originally consisted of low-Mg calcite (Carter, 1990), offers some interesting geochemical criteria in favour of a good preservation of its stable isotope ratios.

Indeed, a statistical analysis of the data reveals a negligible influence of the host lithology (limestone, marl-limestone, marl) on the values of δ

18O, δ

13C, Mg and Sr contents. It should be noted, however, that there are some exceptions with the samples F45, F49 and F67, which are particularly rich in Sr and hosted either in limestones or marly limestones (

Table 1). It can thus be observed that there is a minimal or non-existent influence of lithological control on the values of δ

13C, δ

18O, Mg and Sr. This implies that these sedimentary alternations most likely do not represent cycles resulting from internal (volcanism) or external (orbital astronomical) factors. It can be concluded that the observed variations in the chemical composition of the sediments are not the result of climatic forcing, but rather of early diagenetic processes. These processes involve the movement of fluids containing calcium, strontium and magnesium, which occur during the dissolution of aragonite and the precipitation of calcite in chemically supersaturated zones [

80,

81,

82,

83]. It seems plausible that these processes occurred during the compaction of sedimentary layers linked to hydrostatic pressure. It can thus be postulated that these lithological alternations represent chemical diffusion fronts, which would explain why they do not reflect the original differences in nutrient availability (δ

13C proxy) or water temperature (δ

18O proxy). Consequently, the early Sinemurian may have been a period of relative environmental stability in this region of the Earth. Furthermore, there are two arguments in favour of a non-existent or minor role for late diagenesis involving interactions between these marine sediments and crustal fluids ultimately of meteoric origin.

In the case of late diagenesis, platform sediments that emerge following a sea level fall resulting from glacio-eustatic or tectono-eustatic processes, are subject to water-rock interactions involving freshwater of meteoric origin. These waters are distinguished by markedly low Sr and Mg concentrations [

84,

85,

86,

87] relative to marine waters and oxygen isotope compositions exhibiting a depletion in

18O compared to SMOW. Indeed, for latitudes between 30° and 35°, the δ

18O values of meteoric waters should be between -6‰ and -4‰ (VSMOW) after a correction of data from [

88], which considers the Earth without ice caps. In this framework, the δ

18O of the oceans would have been -0.75(±0.10‰) instead of 0‰ on the VSMOW scale. This value is calculated considering the melting of about 2.6x10

19 kg of continental ice [

89], with a mean δ

18O value of about -40‰ VSMOW [

90], into 1.38x10

21 kg of liquid oceanic water. Furthermore, carbon isotope compositions of fresh waters are influenced by the input of dissolved atmospheric carbon and the oxidation of soil organic matter, as evidenced for example by speleothems [

91,

92] or soil carbonates [

93]. Consequently, this dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) exhibits δ

13C values that can be as low as -14‰ on the VPDB scale in the case the source of carbon is the oxidation of C3 plants [

83]. On the contrary, DIC displays distinctly positive values (0.5‰ < δ

13C DIC < +2.5‰ VPDB for an atmospheric pCO

2 of ≈ 330±10 ppm and its δ

13C value of -7.5±0.2‰ prevailing during the 1971-1978 GEOSECS sampling program), reflecting primary productivity in the photic zone of the water column [

94]. As a consequence of this late diagenesis, the values of δ

18O, δ

13C and Sr and Mg contents tend to linearly decrease, as evidenced by the bivariate diagrams (

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10). In the case of the Fresville study site, however, such trends were not observed, except for

Chlamys, for which a sufficient number of samples made it possible to test the significance of a linear correlation between the δ

13C and δ

18O variables (

Table 4;

Figure 8). The δ

13C and δ

18O data distributions for the Gryphaea samples follow normal distributions once the few outliers are removed from the data set. This observation supports the idea that diagenesis has had little or no effect on the isotopic compositions because biomineral-water interactions generally result in highly asymmetric data distributions, as has been shown by numerical simulations and data sets in the case of biogenic apatites [

95].

4.3. The Marine Paleotemperatures, Water Depth and Seawater δ18O Value

Ostreids belong to the phylum of bivalve molluscs that are known to secrete shell calcite or aragonite in oxygen isotope equilibrium with the ambient water [

70,

96,

97,

98,

99]. Ostreids therefore record fluctuations in the physico-chemical parameters of the aquatic environment in which they grew. The conventional calculation of marine palaeotemperatures from the δ

18O of biominerals is an inherently indeterminate problem from a mathematical standpoint. Two possible approaches can be taken: either an assumption must be made about the δ

18O of the water in the living environment, or it must be determined by an independent method. The theory based on ‘clumped isotopes’ is a sophisticated one, as the measurements of mass 47 (∆

47) allow for the calculation of an absolute temperature, thus enabling the determination of the water δ

18O value. However, this method requires specific calibrations contingent on the taxa under investigation, as evidenced by a recent study [

100] conducted on brachiopods whose shells are composed of low-magnesium calcite. Indeed, at a given temperature, the measured values of ∆

47 are distinct from those measured for foraminifera [

101,

102,

103,

104], inorganic calcites precipitated in the laboratory [

105,

106,

107] cave calcites [

106,

108] and bivalve calcites [

109]. In the absence of precise calibration, uncertainties in temperature may be as high as ±3°C to 5°C, which renders them of limited interest.

In the present case study, it is possible to estimate the δ

18O of seawater based on a pair of data acquired on phosphate remains (teeth) of a plesiosaur associated with a shark tooth collected close to the village of Crussol in the French Ardennes [

33]. The two fossils were deposited in marine sediments of Sinemurian age at a latitude comparable to that at which the remains of the Fresville invertebrate faunas were deposited, indicating that they originated from the same water mass (

Figure 2). [

36] have shown that plesiosaurs partially thermoregulated their bodies, with a body temperature of approximately 32°C determined at latitudes between 30° and 35°N [

36]. This data can be utilized to calculate the δ

18O value of the Sinemurian water mass using equation (1), adapted from [

110]:

with A = 117.4; B = -4.50; δ

18O

p = 18.8‰ (VSMOW) and δ

18O

bw = δ

18O

w + ε

18bw-w, ε

18bw-w being the oxygen isotope enrichment factor between body water (bw) and ambient water (w). Thus, a δ

18O

w value of -0.98 (‰ VSMOW) is calculated from formula (2) as follows:

The temperature (T) of surface marine waters is obtained from the tooth δ

18O value (19.7‰ VSMOW) of

Sphenodus, which was most likely a pelagic neoselachian shark according to its morphological features [

111]. Here, we highlight that his sample has been collected from the same sedimentary bed as that of

Plesiosaurus. So, using equation (1), in which the value of δ

18O

sw is substituted for δ

18O

bw, we obtain a temperature of 24°C for the

Sphenodus living marine environment.

The seawater δ

18O value is then input into a calcite-water isotope fractionation equation [

112] in order to calculate the average temperature of the water in which the

Gryphaea lived. The temperature of 17°C is lower than that of surface water, which is in accordance with the hypothesis that these invertebrates lived in a benthic environment. In the upper part of the water column (≤ 100 m), the vertical temperature gradient is between 0.1°C and 0.2°C per metre for latitudes close to 30° [

113]. Therefore, a temperature difference of 7°C between pelagic and benthic organisms can be equated to a depth difference comprised between 35 m and 70 m.

4.4. Implications on the Regional Paleoclimate and Hydrological Budget

The calculated seawater δ

18O value close to -1‰ (VSMOW) is lower than that calculated in

section 5.1 for a world without polar caps consisting of freshwater, which was -0.75‰ (VSMOW). A mass balance calculation indicates that this value of -1‰ corresponds to a mixture of 92‰ marine water with 8% fresh water. This mass balance is predicated on the assumption that the δ

18O value of meteoric waters at these latitudes should be comprised between -6‰ and -4‰ (VSMOW), subsequent to correction for the oceanic reservoir, which was depleted by 0.75‰ relative to the present value of 0‰ (SMOW reference). The addition of 8% freshwater has a minimal impact on the salinity of marine water, with a change of approximately -1 g.L

-1. This preserves the euhaline character of the water mass, which is a defining feature of the presence of

Gryphaea arcuata and ammonites like

Arietites bucklandi. The presence of

Gryphaea at depths of approximately 50 m is not unexpected. This average depth falls within the euphotic zone, provided that the water column is not significantly affected by turbidity and is sheltered from storm waves. Additionally, some modern and native European and Pacific oysters have been observed at depths down to 80 m [

114,

115]. A seawater δ

18O value of approximately -1‰ (VSMOW) for the Lower Sinemurian at latitudes of 30-35°N indicates a positive water balance (precipitation/evaporation > 1), suggesting that a relatively humid climate must have prevailed over land. Assuming a mean temperature of 24°C, the climatic regime would have corresponded to what is currently designated a humid subtropical climate.

5. Conclusions

A geochemical study of the shells of molluscs present in the Sinemurian marl-limestone alternations at Fresville (Normandy, France) initially demonstrated that the low-Mg calcite shells of the oyster Gryphea arcuata exhibited resilience to the diagenetic processes inherent to marine platform deposits. In the case of the bivalves Pseudolimea, Plagiostoma and Chlamys, the polymorphic transformation of their shells from aragonite to calcite, as evidenced by Raman spectroscopy, serves to highlight the significant alterations that have occurred in their original geochemical compositions as a result of diagenetic processes. The trace element contents and stable isotope ratios of these fossils are unsuitable as proxies for marine paleoenvironmental conditions due to their lower δ18O values, which could lead to an overestimation of marine paleotemperatures. In contrast, the shells of Gryphaea arcuata, which were originally composed of low-Mg calcite, retained well-preserved stable isotope ratios. This conclusion was reached on the basis of the observation that there was a minimal lithological influence on their δ¹³C, δ18O, Mg, and Sr values. Furthermore, there was a lack of linear trends in geochemical markers that are generally the result of mineral-water interactions. Additionally, the normal distribution of δ13C and δ18O values in Gryphaea samples suggests that there were relatively steady environmental conditions during the Early Sinemurian. It was thus concluded that minimal late diagenesis involving meteoric waters, which typically results in a decrease in δ13C, δ18O, Sr, and Mg values due to freshwater interactions, occurred at the Fresville site. The combination of their δ13C and δ18O values with data from the literature concerning teeth (fish and Plesiosaurus) enabled the estimation of the δ18O of Sinemurian seawater (-1‰ VSMOW or -1.27‰ VPDB) in this region, located at approximately 30-35°N, as well as the temperatures of the surface waters (T = 24°C) and the benthic domain (T = 17°C) inhabited by molluscs. It is notable that the surface water temperatures of 24°C are slightly higher than those previously proposed in the literature (T = 15°C to 20°C). However, they are still within the range that could be expected for such latitudes during a greenhouse effect period with an atmosphere that is likely to have had a higher concentration of CO2 than that of the Quaternary. The estimated average temperature of 17°C for Gryphaea arcuata is consistent with the temperature range that is optimal for the survival of these benthic molluscs, which inhabit a depth of approximately 50 m. In addition, 13C-enriched carbon isotope compositions of Gryphaea arcuata calcite shells relative to the VPDB marine reference indicate a marine environment characterized by a high rate of marine productivity. The seawater δ18O value of approximately -1‰ (VSMOW) for the Lower Sinemurian at latitudes of 30°N-35°N indicates a positive water balance (precipitation/evaporation > 1), which suggests that a relatively humid climate must have prevailed over land. Assuming a mean temperature of 24°C for surface marine waters, the climatic regime would have corresponded to a humid subtropical climate, as observed nowadays in the southeastern United States, northern Argentina, southeastern China, or eastern Australia, according to the Köppen-Geiger climate classification.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.L. and E.B.; methodology, L.P., F.F., R.A., C.L., F.A.-G.; formal analysis, C.L., L.P., F.F..; investigation, C.L., E.B., H.T.; writing—original draft preparation, L.P., C.L.; writing—review and editing, C.L.; supervision, C.L.; funding acquisition, C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

This study has been funded by CNRS and IUF (CL). We are especially grateful to the members of the Club de Géologie du Cotentin, which manages the Fresville quarry, for their invaluable help during the collection of the samples used in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cohen, K.M., Finney, S.C., Gibbard, P.L., and Fan, J.-X. The Ics International Chronostratigraphic Chart. Episodes Journal of International Geoscience 2013, 36, no. 3, 199-204.

- Hallam, A., and Wignall, P.B. Mass Extinctions and Their Aftermath: Oxford University Press, UK, 1997.

- Erwin, D.H. Lessons from the Past: Biotic Recoveries from Mass Extinctions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2001, 98, no. 10, 5399-403. [CrossRef]

- McElwain, J.C., Popa, M.E., Hesselbo, S.P., Haworth, M., and Surlyk, F. Macroecological Responses of Terrestrial Vegetation to Climatic and Atmospheric Change across the Triassic/Jurassic Boundary in East Greenland. Paleobiology 2007, 33, no. 4, 547-73. [CrossRef]

- McElwain, J.C., Wagner, P.J., and Hesselbo, S.P. Fossil Plant Relative Abundances Indicate Sudden Loss of Late Triassic Biodiversity in East Greenland. Science 2009, 324, no. 5934, 1554-56.

- Van de Schootbrugge, B., Quan, T., Lindström, S., Püttmann, W., Heunisch, C., Pross, J., Fiebig, J., Petschick, R., Röhling, H.-G., and Richoz, S. Floral Changes across the Triassic/Jurassic Boundary Linked to Flood Basalt Volcanism. Nature Geoscience 2009, 2, no. 8, 589-94. [CrossRef]

- Ros, S., and Echevarría, J. Ecological Signature of the End-Triassic Biotic Crisis: What Do Bivalves Have to Say? Historical Biology 2012, 24, no. 5, 489-503.

- Damborenea, S.E., Echevarría, J., and Ros-Franch, S. Biotic Recovery after the End-Triassic Extinction Event: Evidence from Marine Bivalves of the Neuquén Basin, Argentina. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 2017, 487, 93-104.

- Slater, S.M., Kustatscher, E., and Vajda, V. “An Introduction to Jurassic Biodiversity and Terrestrialenvironments.” 1-5: Springer, 2018.

- Schoepfer, S.D., Algeo, T.J., van de Schootbrugge, B., and Whiteside, J.H. “The Triassic–Jurassic Transition–a Review of Environmental Change at the Dawn of Modern Life.” 104099: Elsevier, 2022.

- McLoughlin, S. The Breakup History of Gondwana and Its Impact on Pre-Cenozoic Floristic Provincialism. Australian Journal of Botany 2001, 49, no. 3, 271-300. [CrossRef]

- McElwain, J.C., Wade-Murphy, J., and Hesselbo, S.P. Changes in Carbon Dioxide During an Oceanic Anoxic Event Linked to Intrusion into Gondwana Coals. Nature 2005, 435, no. 7041, 479-82.

- Steinthorsdottir, M., and Vajda, V. Early Jurassic (Late Pliensbachian) Co2 Concentrations Based on Stomatal Analysis of Fossil Conifer Leaves from Eastern Australia. Gondwana Research 2015, 27, no. 3, 932-39.

- Vakhrameev, V.A. Jurassic and Cretaceous Floras and Climates of the Earth: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

- Little, C.T., and Benton, M.J. Early Jurassic Mass Extinction: A Global Long-Term Event. Geology 1995, 23, no. 6, 495-98.

- Gee, C.T., Anderson, H.M., Anderson, J.M., Ash, S.R., Cantrill, D.J., van Konijnenburg-van Cittert, J.H., Vajda, V., Vajda, V., Gee, C.T., and Cantrill, D.J. Postcards from the Mesozoic: Forest Landscapes with Giant Flowering Trees, Enigmatic Seed Ferns, and Other Naked-Seed Plants. In Nature through Time: Virtual Field Trips through the Nature of the Past, 159-85: Springer, 2020.

- Wachtler, M. The Fossil Flora of the Early Jurassic. Dolomythos, Innichen, Italy, 2024.

- Benton, M.J. Origin and Early Evolution of Dinosaurs: Indiana University Press Bloomington, Indiana, 1997.

- Sander, P.M., Christian, A., Clauss, M., Fechner, R., Gee, C.T., Griebeler, E.M., Gunga, H.C., Hummel, J., Mallison, H., and Perry, S.F. Biology of the Sauropod Dinosaurs: The Evolution of Gigantism. Biological Reviews 2011, 86, no. 1, 117-55.

- Chiarenza, A.A. The Macroecology of Mesozoic Dinosaurs. Biology Letters 2024, 20, no. 11, 20240392.

- Benton, M.J. The Dinosaur Boom in the Cretaceous. Geological Society, London, Special Publications 2025, 544, no. 1, SP544-2023-70. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.-X., Crompton, A.W., and Sun, A.-L. A New Mammaliaform from the Early Jurassic and Evolution of Mammalian Characteristics. Science 2001, 292, no. 5521, 1535-40.

- Sidor, C.A. Simplification as a Trend in Synapsid Cranial Evolution. Evolution 2001, 55, no. 7, 1419-42.

- Riese, D.J., Hasiotis, S.T., and Odier, G.P. Synapsid Burrows and Associated Trace Fossils in the Lower Jurassic Navajo Sandstone, Southeastern Utah, USA, Indicates a Diverse Community Living in a Wet Desert Ecosystem. Journal of Sedimentary Research 2011, 81, no. 4, 299-325. [CrossRef]

- Newham, E., Gill, P.G., Brewer, P., Benton, M.J., Fernandez, V., Gostling, N.J., Haberthür, D., Jernvall, J., Kankaanpää, T., and Kallonen, A. Reptile-Like Physiology in Early Jurassic Stem-Mammals. Nature Communications 2020, 11, no. 1, 5121.

- Stanley Jr, G.D. Early History of Scleractinian Corals and Its Geological Consequences. Geology 1981, 9, no. 11, 507-11.

- Smith, A.S., and Vincent, P. A New Genus of Pliosaur (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) from the Lower Jurassic of Holzmaden, Germany. Palaeontology 2010, 53, no. 5, 1049-63. [CrossRef]

- Thuy, B., Kiel, S., Dulai, A., Gale, A.S., Kroh, A., Lord, A.R., Numberger-Thuy, L.D., Stöhr, S., and Wisshak, M. First Glimpse into Lower Jurassic Deep-Sea Biodiversity: In Situ Diversification and Resilience against Extinction. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2014, 281, no. 1786, 20132624.

- Bardet, N., Falconnet, J., Fischer, V., Houssaye, A., Jouve, S., Suberbiola, X.P., Pérez-García, A., Rage, J.-C., and Vincent, P. Mesozoic Marine Reptile Palaeobiogeography in Response to Drifting Plates. Gondwana Research 2014, 26, no. 3-4, 869-87. [CrossRef]

- Kocsis, Á.T., Kiessling, W., and Pálfy, J. Radiolarian Biodiversity Dynamics through the Triassic and Jurassic: Implications for Proximate Causes of the End-Triassic Mass Extinction. Paleobiology 2014, 40, no. 4, 625-39.

- Dommergues, J.-L., Laurin, B., and Meister, C. Evolution of Ammonoid Morphospace During the Early Jurassic Radiation. Paleobiology 1996, 22, no. 2, 219-40. [CrossRef]

- Stumpf, S., Ansorge, J., Pfaff, C., and Kriwet, J. Early Jurassic Diversification of Pycnodontiform Fishes (Actinopterygii, Neopterygii) after the End-Triassic Extinction Event: Evidence from a New Genus and Species, Grimmenodon Aureum. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 2017, 37, no. 4, e1344679.

- Bernard, A., Lécuyer, C., Vincent, P., Amiot, R., Bardet, N., Buffetaut, E., Cuny, G., Fourel, F., Martineau, F., and Mazin, J.-M. Regulation of Body Temperature by Some Mesozoic Marine Reptiles. Science 2010, 328, no. 5984, 1379-82.

- Fleischle, C.V., Wintrich, T., and Sander, P.M. Quantitative Histological Models Suggest Endothermy in Plesiosaurs. PeerJ 2018, 6, e4955. [CrossRef]

- Brice, P., and Grigg, G. Modeling Gigantothermy Endorses the Whole-Body Tachymetabolic Endothermy of Ichthyosaurs, Mosasaurs, and Plesiosaurs (Sauropsida). Ruling Reptiles: Crocodylian Biology and Archosaur Paleobiology 2023, 312.

- Séon, N., Vincent, P., Delsett, L.L., Poulallion, E., Suan, G., Lécuyer, C., Roberts, A.J., Fourel, F., Charbonnier, S., and Amiot, R. Reassessment of Body Temperature and Thermoregulation Strategies in Mesozoic Marine Reptiles. Palaeobiology 2025, in press.

- Trueman, A.E. The Use of Gryphaea in the Correlation of the Lower Lias. Geological Magazine 1922, 59, no. 6, 256-68. [CrossRef]

- Hallam, A., and Gould, S.J. The Evolution of British and American Middle and Upper Jurassic Gryphaea: A Biometric Study. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B. Biological Sciences 1975, 189, no. 1097, 511-42.

- Hallam, A. Patterns of Speciation in Jurassic Gryphaea. Paleobiology 1982, 8, no. 4, 354-66.

- Nori, L., and Lathuilière, B. Form and Environment of Gryphaea Arcuata. Lethaia 2003, 36, no. 2, 83-96. [CrossRef]

- Radley, J. Gryphaea Beds (Upper Scunthorpe Mudstone Formation; Lower Jurassic) at Scunthorpe, North Lincolnshire, North-East England. Proceedings of the Yorkshire Geological Society 2008, 57, no. 2, 107-12.

- Dera, G., Pellenard, P., Neige, P., Deconinck, J.-F., Pucéat, E., and Dommergues, J.-L. Distribution of Clay Minerals in Early Jurassic Peritethyan Seas: Palaeoclimatic Significance Inferred from Multiproxy Comparisons. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 2009a, 271, no. 1-2, 39-51.

- Hudson, A.J.L. Magnitude and Pacing of Early Jurassic Palaeoclimate Change: Chemostratigraphy and Cyclostratigraphy of the British Lower Jurassic (Sinemurian–Pliensbachian): University of Exeter (United Kingdom), 2020.

- Doyle, P. Lower Jurassic-Lower Cretaceous Belemnite Biogeography and the Development of the Mesozoic Boreal Realm. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 1987, 61, 237-54. [CrossRef]

- Dera, G., Pucéat, E., Pellenard, P., Neige, P., Delsate, D., Joachimski, M.M., Reisberg, L., and Martinez, M. Water Mass Exchange and Variations in Seawater Temperature in the Nw Tethys During the Early Jurassic: Evidence from Neodymium and Oxygen Isotopes of Fish Teeth and Belemnites. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 2009b, 286, no. 1-2, 198-207. [CrossRef]

- Hesselbo, S.P., Meister, C., and Gröcke, D.R. A Potential Global Stratotype for the Sinemurian–Pliensbachian Boundary (Lower Jurassic), Robin Hood’s Bay, Uk: Ammonite Faunas and Isotope Stratigraphy. Geological Magazine 2000, 137, no. 6, 601-07.

- McArthur, J., Donovan, D., Thirlwall, M., Fouke, B., and Mattey, D. Strontium Isotope Profile of the Early Toarcian (Jurassic) Oceanic Anoxic Event, the Duration of Ammonite Biozones, and Belemnite Palaeotemperatures. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 2000, 179, no. 2, 269-85.

- Jenkyns, H.C., Jones, C.E., GrÖcke, D.R., Hesselbo, S.P., and Parkinson, D.N. Chemostratigraphy of the Jurassic System: Applications, Limitations and Implications for Palaeoceanography. Journal of the Geological Society 2002, 159, no. 4, 351-78. [CrossRef]

- Van de Schootbrugge, B., Bailey, T.R., Rosenthal, Y., Katz, M.E., Wright, J.D., Miller, K.G., Feist-Burkhardt, S., and Falkowski, P.G. Early Jurassic Climate Change and the Radiation of Organic-Walled Phytoplankton in the Tethys Ocean. Paleobiology 2005, 31, no. 1, 73-97.

- Brigaud, B., Vincent, B., Carpentier, C., Robin, C., Guillocheau, F., Yven, B., and Huret, E. Growth and Demise of the Jurassic Carbonate Platform in the Intracratonic Paris Basin (France): Interplay of Climate Change, Eustasy and Tectonics. Marine and Petroleum Geology 2014, 53, 3-29. [CrossRef]

- Stampfli, G.M., and Borel, G. A Plate Tectonic Model for the Paleozoic and Mesozoic Constrained by Dynamic Plate Boundaries and Restored Synthetic Oceanic Isochrons. Earth and Planetary science letters 2002, 196, no. 1-2, 17-33. [CrossRef]

- Stampfli, G., Hochard, C., Vérard, C., and Wilhem, C. The Formation of Pangea. Tectonophysics 2013, 593, 1-19.

- Golonka, J., and Ford, D. Pangean (Late Carboniferous–Middle Jurassic) Paleoenvironment and Lithofacies. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 2000, 161, no. 1-2, 1-34.

- Smith, A.G., Smith, D.G., and Funnell, B.M. Atlas of Mesozoic and Cenozoic Coastlines: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Baghli, H., Mattioli, E., Spangenberg, J., Bensalah, M., Arnaud-Godet, F., Pittet, B., and Suan, G. Early Jurassic Climatic Trends in the South-Tethyan Margin. Gondwana Research 2020, 77, 67-81. [CrossRef]

- Desquesne, A. La carrière de Fresville. Le Sinémurien. Club de Géologie du Cotentin: Fresville, France, 2023.

- Lepage, Y., Cuny, G., Desquesne, A. Première découverte d’Acrodus nobilis Agassiz, 1838, dans le Sinémurien du Cotentin (Normandie, France). Bulletin Sciences et Géologie Normandes, 2011, 3, p. 7-13.

- Lepage, Y., Buffetaut, E. Compte-rendu d’une excursion pluridisciplinaire dans le Cotentin (50 - Manche) (Du dimanche 7 au dimanche 14 juin 2009). Bulletin Sciences et Géologie Normandes, 2010, 1, p. 55-67.

- Corna, M., Dommergues, J.a., Meister, C., Mouterde, R., and Bloos, G. Sinémurien. Groupe franais d’étude du Jurassique: Biostratigraphie du Jurassique ouest-européen et méditerranéen: zonations parallles et distribution des invertébrés et microfossiles. Cariou E. and Hantzpergue P 1997, 9-14.

- Jones, D.S., and Quitmyer, I.R. Marking Time with Bivalve Shells: Oxygen Isotopes and Season of Annual Increment Formation. Palaios 1996, 340-46.

- Jones, D.S., and Gould, S.J. Direct Measurement of Age in Fossil Gryphaea: The Solution to a Classic Problem in Heterochrony. Paleobiology 1999, 25, no. 2, 158-87. [CrossRef]

- Danise, S., Price, G.D., Alberti, M., and Holland, S.M. Isotopic Evidence for Partial Geochemical Decoupling between a Jurassic Epicontinental Sea and the Open Ocean. Gondwana Research 2020, 82, 97-107. [CrossRef]

- Al-Aasm, I.S., and Veizer, J. Chemical Stabilization of Low-Mg Calcite; an Example of Brachiopods. Journal of Sedimentary Research 1982, 52, no. 4, 1101-09.

- Veizer, J. Trace Elements and Isotopes in Sedimentary Carbonates. Reviews in mineralogy 1983, 11, 265-300.

- Marshall, J.D. Climatic and Oceanographic Isotopic Signals from the Carbonate Rock Record and Their Preservation. Geological magazine 1992, 129, no. 2, 143-60.

- Ullmann, C.V., and Korte, C. Diagenetic Alteration in Low-Mg Calcite from Macrofossils: A Review. Geological Quarterly 2015, 59, no. 1, 3-20, doi: 10.7306/gq. 1217.

- Hallam, A. On the Supposed Evolution of Gryphaea in the Lias. Geological Magazine 1959, 96, no. 2, 99-108. [CrossRef]

- Gould, S.J. Allometric Fallacies and the Evolution of Gryphaea: A New Interpretation Based on White’s Criterion of Geometric Similarity. Evolutionary Biology: Volume 6 1972, 91-119.

- Lartaud, F. Les Fluctuations Haute Fréquence De L’environnement Au Cours Des Temps Géologiques: Mise Au Point D’un Modèle De Référence Actuel Sur L’enregistrement Des Contrastes Saisonniers Dans L’atlantique Nord. Paris 6, 2007.

- Huyghe, D., Emmanuel, L., de Rafélis, M., Renard, M., Ropert, M., Labourdette, N., and Lartaud, F. Oxygen Isotope Disequilibrium in the Juvenile Portion of Oyster Shells Biases Seawater Temperature Reconstructions. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 2020, 240, 106777.

- Roelandts, I., and Duchesne, J. Awi-1 Sbo-1, Pri-1, and Dwa-1, Belgian Sedimentary Rock Reference Materials. Geostandards Newsletter 1988, 12, no. 1, 13-38. [CrossRef]

- Swart, P.K., Burns, S., and Leder, J. Fractionation of the Stable Isotopes of Oxygen and Carbon in Carbon Dioxide During the Reaction of Calcite with Phosphoric Acid as a Function of Temperature and Technique. Chemical Geology: Isotope Geoscience section 1991, 86, no. 2, 89-96. [CrossRef]

- Urmos, J., Sharma, S., and Mackenzie, F. Characterization of Some Biogenic Carbonates with Raman Spectroscopy. American Mineralogist 1991, 76, no. 3-4, 641-46.

- Bischoff, W.D., Sharma, S.K., and MacKenzie, F.T. Carbonate Ion Disorder in Synthetic and Biogenic Magnesian Calcites: A Raman Spectral Study. American Mineralogist 1985, 70, no. 5-6, 581-89.

- Hallam, A. Morphology, Palaeoecology and Evolution of the Genus Gryphaea in the British Lias. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences 1968, 254, no. 792, 91-128.

- Lohmann, K.C., and Walker, J.C. The Δ18o Record of Phanerozoic Abiotic Marine Calcite Cements. Geophysical Research Letters 1989, 16, no. 4, 319-22.

- Gao, G., and Land, L.S. Geochemistry of Cambro-Ordovician Arbuckle Limestone, Oklahoma: Implications for Diagenetic Δ18o Alteration and Secular Δ13c and 87sr86sr Variation. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 1991, 55, no. 10, 2911-20.

- Ahm, A.-S.C., Bjerrum, C.J., Blättler, C.L., Swart, P.K., and Higgins, J.A. Quantifying Early Marine Diagenesis in Shallow-Water Carbonate Sediments. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 2018, 236, 140-59.

- Wostbrock, J.A., and Sharp, Z.D. Triple Oxygen Isotopes in Silica–Water and Carbonate–Water Systems. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry 2021, 86, no. 1, 367-400.

- Ricken, W. Diagenetic Bedding: A Model for Marl-Limestone Alternations. Lecture Notes in Earth Sciences, Berlin Springer Verlag 1986, 6.

- Westphal, H., Munnecke, A., Böhm, F., and Bornholdt, S. Limestone-Marl Alternations in Epeiric Sea Settings–Witnesses of Environmental Changes or Diagenesis. Dynamics of Epeiric Seas: Sedimentological, Paleontological and Geochemical Perspectives. Geol. Assoc. Can. SP 2008a, 48, 389-406.

- Westphal, H., Munnecke, A., and Brandano, M. Effects of Diagenesis on the Astrochronological Approach of Defining Stratigraphic Boundaries in Calcareous Rhythmites: The Tortonian Gssp. Lethaia 2008b, 41, no. 4, 461-76.

- Li, T.-Y., Huang, C.-X., Tian, L., Suarez, M.B., and Gao, Y. Variation of D13c in Plant-Soil-Cave Systems in Karst Regions with Different Degrees of Rocky Desertification in Southwest China and Implications for Paleoenvironment Reconstruction. Journal of Cave and Karst Studies 2018, 80, no. 4.

- Meybeck, M. Total Mineral Dissolved Transport by World Major Rivers/Transport En Sels Dissous Des Plus Grands Fleuves Mondiaux. Hydrological Sciences Journal 1976, 21, no. 2, 265-84. [CrossRef]

- Meybeck, M. Global Analysis of River Systems: From Earth System Controls to Anthropocene Syndromes. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences 2003, 358, no. 1440, 1935-55.

- Salve, P., Maurya, A., Wate, S., and Devotta, S. Chemical Composition of Major Ions in Rainwater. Bulletin of environmental contamination and toxicology 2008, 80, no. 3, 242-46.

- Berner, E.K., and Berner, R.A. Global Environment: Water, Air, and Geochemical Cycles: Princeton University Press, 2012.

- Bowen, G.J., and Wilkinson, B. Spatial Distribution of Δ18o in Meteoric Precipitation. Geology 2002, 30, no. 4, 315-18.

- Otosaka, I.N., Shepherd, A., Ivins, E.R., Schlegel, N.-J., Amory, C., van den Broeke, M., Horwath, M., Joughin, I., King, M., and Krinner, G. Mass Balance of the Greenland and Antarctic Ice Sheets from 1992 to 2020. Earth System Science Data Discussions 2022, 2022, 1-33.

- Blunier, T., and Brook, E.J. Timing of Millennial-Scale Climate Change in Antarctica and Greenland During the Last Glacial Period. science 2001, 291, no. 5501, 109-12.

- McDermott, F. Palaeo-Climate Reconstruction from Stable Isotope Variations in Speleothems: A Review. Quaternary Science Reviews 2004, 23, no. 7-8, 901-18. [CrossRef]

- Dorale, J.A., and Liu, Z. Limitations of Hendy Test Criteria in Judging the Paleoclimatic Suitability of Speleothems and the Need for Replication. Journal of cave and karst studies 2009, 71, no. 1, 73-80.

- Salomons, W., and Mook, W. Isotope Geochemistry of Carbonates in the Weathering Zone. Handbook of environmental isotope geochemistry 1986, 2, 239-69.

- Kroopnick, P. The Distribution of 13c of Σco2 in the World Oceans. Deep Sea Research Part A. Oceanographic Research Papers 1985, 32, no. 1, 57-84.

- Lécuyer, C., and Flandrois, J.-P. Mitigation of the Diagenesis Risk in Biological Apatite Δ18o Interpretation. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 2023, 630, 111812.

- Kirby, M.X., Soniat, T.M., and Spero, H.J. Stable Isotope Sclerochronology of Pleistocene and Recent Oyster Shells (Crassostrea Virginica). Palaios 1998, 13, no. 6, 560-69. [CrossRef]

- Ullmann, C.V., Böhm, F., Rickaby, R.E., Wiechert, U., and Korte, C. The Giant Pacific Oyster (Crassostrea Gigas) as a Modern Analog for Fossil Ostreoids: Isotopic (Ca, O, C) and Elemental (Mg/Ca, Sr/Ca, Mn/Ca) Proxies. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems 2013, 14, no. 10, 4109-20.

- Lécuyer, C., Reynard, B., and Martineau, F. Stable Isotope Fractionation between Mollusc Shells and Marine Waters from Martinique Island. Chemical Geology 2004, 213, no. 4, 293-305.

- Tynan, S., Dutton, A., Eggins, S., and Opdyke, B. Oxygen Isotope Records of the Australian Flat Oyster (Ostrea Angasi) as a Potential Temperature Archive. Marine Geology 2014, 357, 195-209.

- Letulle, T., Gaspard, D., Daëron, M., Arnaud-Godet, F., Vinçon-Laugier, A., Suan, G., and Lécuyer, C. Multi-Proxy Assessment of Brachiopod Shell Calcite as a Potential Archive of Seawater Temperature and Oxygen Isotope Composition. Biogeosciences 2023, 20, no. 7, 1381-403.

- Breitenbach, S.F., Mleneck-Vautravers, M.J., Grauel, A.-L., Lo, L., Bernasconi, S.M., Müller, I.A., Rolfe, J., Gázquez, F., Greaves, M., and Hodell, D.A. Coupled Mg/Ca and Clumped Isotope Analyses of Foraminifera Provide Consistent Water Temperatures. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 2018, 236, 283-96. [CrossRef]

- Daëron, M., Blamart, D., Peral, M., and Affek, H.P. Absolute Isotopic Abundance Ratios and the Accuracy of Δ47 Measurements. Chemical Geology 2016, 442, 83-96.

- Meinicke, N., Ho, S., Hannisdal, B., Nürnberg, D., Tripati, A., Schiebel, R., and Meckler, A. A Robust Calibration of the Clumped Isotopes to Temperature Relationship for Foraminifers. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 2020, 270, 160-83. [CrossRef]

- Peral, M., Bassinot, F., Daëron, M., Blamart, D., Bonnin, J., Jorissen, F., Kissel, C., Michel, E., Waelbroeck, C., and Rebaubier, H. On the Combination of the Planktonic Foraminiferal Mg/Ca, Clumped (Δ47) and Conventional (Δ18o) Stable Isotope Paleothermometers in Palaeoceanographic Studies. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 2022, 339, 22-34.

- Jautzy, J., Savard, M., Dhillon, R., Bernasconi, S.M., and Smirnoff, A. Clumped Isotope Temperature Calibration for Calcite: Bridging Theory and Experimentation. Geochemical Perspectives Letters 2020, 14, 36-41.

- Anderson, N., Kelson, J.R., Kele, S., Daëron, M., Bonifacie, M., Horita, J., Mackey, T.J., John, C.M., Kluge, T., and Petschnig, P. A Unified Clumped Isotope Thermometer Calibration (0.5–1,100 C) Using Carbonate-Based Standardization. Geophysical Research Letters 2021, 48, no. 7, e2020GL092069. [CrossRef]

- Fiebig, J., Daëron, M., Bernecker, M., Guo, W., Schneider, G., Boch, R., Bernasconi, S.M., Jautzy, J., and Dietzel, M. Calibration of the Dual Clumped Isotope Thermometer for Carbonates. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 2021, 312, 235-56.

- Daëron, M., Drysdale, R.N., Peral, M., Huyghe, D., Blamart, D., Coplen, T.B., Lartaud, F., and Zanchetta, G. Most Earth-Surface Calcites Precipitate out of Isotopic Equilibrium. Nature communications 2019, 10, no. 1, 429.

- Huyghe, D., Daëron, M., de Rafelis, M., Blamart, D., Sébilo, M., Paulet, Y.-M., and Lartaud, F. Clumped Isotopes in Modern Marine Bivalves. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 2022, 316, 41-58.

- Lécuyer, C., Amiot, R., Touzeau, A., and Trotter, J. Calibration of the Phosphate 18O Thermometer with Carbonate–Water Oxygen Isotope Fractionation Equations. Chemical Geology 2013, 347, 217-26. [CrossRef]

- Villalobos-Segura, E., Stumpf, S., Türtscher, J., Jambura, P.L., Begat, A., López-Romero, F.A., Fischer, J., and Kriwet, J. A Synoptic Review of the Cartilaginous Fishes (Chondrichthyes: Holocephali, Elasmobranchii) from the Upper Jurassic Konservat-Lagerstätten of Southern Germany: Taxonomy, Diversity, and Faunal Relationships. Diversity 2023, 15, no. 3, 386.

- Kim, S.-T., and O’Neil, J.R. Equilibrium and Nonequilibrium Oxygen Isotope Effects in Synthetic Carbonates. Geochimica et cosmochimica acta 1997, 61, no. 16, 3461-75. [CrossRef]

- Levitus, S., Boyer, T.P. World ocean atlas 1994. volume 4. temperature (No. PB-95-270112/XAB; NESDIS-4). National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service, Washington, DC (United States), 1994.

- King, N.G., Wilmes, S.B., Smyth, D., Tinker, J., Robins, P.E., Thorpe, J., Jones, L., and Malham, S.K. Climate Change Accelerates Range Expansion of the Invasive Non-Native Species, the Pacific Oyster, Crassostrea Gigas. ICES Journal of Marine Science 2021, 78, no. 1, 70-81. [CrossRef]

- McCormick, H., Debney, A., Gamble, C., Gillies, C., Hancock, B., t Laugen, A., Pouvreau, S., Preston, J., and Strand, Å. European Native Oyster Reef Ecosystems Are Universally Collapsed. Conservation Letters 2024, e13068. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Paleogeographic map during the lower Jurassic showing the extent of epicontinental seas in western Europe.

Figure 1.

Paleogeographic map during the lower Jurassic showing the extent of epicontinental seas in western Europe.

Figure 4.

Photo plate of hand specimens of mollusc fossils from the lower Sinemurian of Fresville, Normandy, France.

Figure 4.

Photo plate of hand specimens of mollusc fossils from the lower Sinemurian of Fresville, Normandy, France.

Figure 5.

Raman spectra for two specimens of studied Gryphaea arcuata from the lower Sinemurian of Fresville, Normandy, France. See the text for interpretation.

Figure 5.

Raman spectra for two specimens of studied Gryphaea arcuata from the lower Sinemurian of Fresville, Normandy, France. See the text for interpretation.

Figure 6.

Variations in δ18O values of mollusc shells from the lower Sinemurian of Fresville versus their position in the stratigraphic sequence in cm above the base of the layer#1.

Figure 6.

Variations in δ18O values of mollusc shells from the lower Sinemurian of Fresville versus their position in the stratigraphic sequence in cm above the base of the layer#1.

Figure 7.

Variations in δ13C values of mollusc shells from the lower Sinemurian of Fresville versus their position in the stratigraphic sequence in cm above the base of the layer#1.

Figure 7.

Variations in δ13C values of mollusc shells from the lower Sinemurian of Fresville versus their position in the stratigraphic sequence in cm above the base of the layer#1.

Figure 8.

δ

13C values

versus δ

18O values

plot illustrating the putative linear correlations between those variables for the studied mollusc calcite shells (Gryphaea arcuata, Pseudolimea, Plagiostoma and Chlamys

) from the lower Sinemurian of Fresville, Normandy, France. See also Table 3 and

Table 4 for Gryphaea arcuata and Chlamys statistical tests.

Figure 8.

δ

13C values

versus δ

18O values

plot illustrating the putative linear correlations between those variables for the studied mollusc calcite shells (Gryphaea arcuata, Pseudolimea, Plagiostoma and Chlamys

) from the lower Sinemurian of Fresville, Normandy, France. See also Table 3 and

Table 4 for Gryphaea arcuata and Chlamys statistical tests.

Figure 9.

δ

18O values

versus Sr contents

plot illustrating the putative linear correlations between those variables for the studied mollusc calcite shells (Gryphaea arcuata, Pseudolimea, Plagiostoma and Chlamys

) from the lower Sinemurian of Fresville, Normandy, France. See also Table 3 and

Table 4 for Gryphaea arcuata and Chlamys statistical tests.

Figure 9.

δ

18O values

versus Sr contents

plot illustrating the putative linear correlations between those variables for the studied mollusc calcite shells (Gryphaea arcuata, Pseudolimea, Plagiostoma and Chlamys

) from the lower Sinemurian of Fresville, Normandy, France. See also Table 3 and

Table 4 for Gryphaea arcuata and Chlamys statistical tests.

Figure 10.

δ

18O values

versus Mg contents

plot illustrating the putative linear correlations between those variables for the studied mollusc calcite shells (Gryphaea arcuata, Pseudolimea, Plagiostoma and Chlamys

) from the lower Sinemurian of Fresville, Normandy, France. See also Table 3 and

Table 4 for Gryphaea arcuata and Chlamys statistical tests.

Figure 10.

δ

18O values

versus Mg contents

plot illustrating the putative linear correlations between those variables for the studied mollusc calcite shells (Gryphaea arcuata, Pseudolimea, Plagiostoma and Chlamys

) from the lower Sinemurian of Fresville, Normandy, France. See also Table 3 and

Table 4 for Gryphaea arcuata and Chlamys statistical tests.

Table 2.

Shapiro-Wilk normal distribution tests for δ13C and δ18O values, Sr and Mg contents of Gryphaea arcuata calcite shells collected from the lower Sinemurian of Fresville, Normandy, France. H0 = normal distribution (95% probability).

Table 2.

Shapiro-Wilk normal distribution tests for δ13C and δ18O values, Sr and Mg contents of Gryphaea arcuata calcite shells collected from the lower Sinemurian of Fresville, Normandy, France. H0 = normal distribution (95% probability).

| Variable |

n |

p |

H0

|

W |

95% |

outliers |

p without |

H0

|

| |

|

|

|

|

interval |

|

outliers |

|

| Sr |

53 |

1.88E-07 |

rejected |

0.7817 |

[0.9562,1] |

6161, 4124, 4318 |

0.027 |

rejected |

| Mg |

53 |

6.05E-07 |

rejected |

0.8038 |

[0.9562,1] |

2076, 1298 |

0.008 |

rejected |

| δ13C |

53 |

0.019 |

rejected |

0.9463 |

[0.9562,1] |

0.84, 0.64 |

0.269 |

accepted |

| δ18O |

53 |

0.047 |

rejected |

0.9556 |

[0.9562,1] |

-0.67, -0.78 |

0.279 |

accepted |

Table 3.

Pearson and Spearman correlation tests for δ13C and δ18O values, Sr and Mg contents of Gryphaea arcuata calcite shells collected from the lower Sinemurian of Fresville, Normandy, France. H0 = no correlation between paired variables (95% probability).

Table 3.

Pearson and Spearman correlation tests for δ13C and δ18O values, Sr and Mg contents of Gryphaea arcuata calcite shells collected from the lower Sinemurian of Fresville, Normandy, France. H0 = no correlation between paired variables (95% probability).

| Pair of variables |

|

Pearson |

Spearman |

Outliers |

Outliers |

| |

n |

r |

p |

r |

p |

Y |

X |

| Sr, Mg |

53 |

0.437 |

0.001 |

0.572 |

0.001 |

4124, 4318, 6161 |

2076 |

| δ13C, 18O |

53 |

0.438 |

0.001 |

0.474 |

3.40E-04 |

0.64, 0.84 |

-0.78, -0.67 |

| δ13C, Sr |

53 |

-0.055 |

0.698 |

-0.075 |

0.598 |

0.64, 0.84 |

4124, 4318, 6161 |

| δ13C, Mg |

53 |

0.002 |

0.988 |

-0.06 |

0.647 |

0.64, 0.84 |

2076 |

| δ18O, Sr |

53 |

-0.18 |

0.202 |

-0.2 |

0.141 |

-0.78, -0.67 |

4124, 4318, 6161 |

| δ18O, Mg |

53 |

-0.28 |

0.042 |

-0.27 |

0.048 |

-0.78, -0.67 |

2076 |

Table 4.

Pearson and Spearman correlation tests for δ13C and δ18O values, Sr and Mg contents of Chlamys calcite shells collected from the lower Sinemurian of Fresville, Normandy, France. H0 = no correlation between paired variables (95% probability).

Table 4.

Pearson and Spearman correlation tests for δ13C and δ18O values, Sr and Mg contents of Chlamys calcite shells collected from the lower Sinemurian of Fresville, Normandy, France. H0 = no correlation between paired variables (95% probability).

| Pair of variables |

|

Pearson |

Spearman |

Outliers |

Outliers |

| |

n |

r |

p |

r |

p |

Y |

X |

| Sr, Mg |

11 |

-0.354 |

0.315 |

-0.158 |

0.663 |

3232, 4666 |

– |

| δ13C, 18O |

11 |

0.680 |

0.021 |

0.546 |

8.70E-02 |

– |

– |

| δ13C, Sr |

11 |

-0.096 |

0.793 |

0.152 |

0.676 |

– |

3232, 4666 |

| δ13C, Mg |

11 |

0.389 |

0.266 |

0.213 |

0.555 |

– |

– |

| δ18O, Sr |

11 |

0.207 |

0.556 |

0.552 |

0.098 |

-3.16 |

3232, 4666 |

| δ18O, Mg |

11 |

0.350 |

0.322 |

0.462 |

0.179 |

-3.16 |

– |

Table 5.

Minimal, maximal and mean values for δ13C and δ18O values, Sr and Mg contents of studied mollusc shells collected from the lower Sinemurian of Fresville, Normandy, France. Gr = Gryphaea arcuata; Ch = Chlamys; Ps = Pseudolimea; Pl = Plagiostoma.

Table 5.

Minimal, maximal and mean values for δ13C and δ18O values, Sr and Mg contents of studied mollusc shells collected from the lower Sinemurian of Fresville, Normandy, France. Gr = Gryphaea arcuata; Ch = Chlamys; Ps = Pseudolimea; Pl = Plagiostoma.

| |

Minimum |

Maximum |

Mean |

| Sr (Gr) |

885 |

6161 |

1911 |

| Sr (Ch) |

1197 |

4666 |

2052 |

| Sr (Ps) |

613 |

4627 |

1492 |

| Sr (Pl) |

335 |

2000 |

1297 |

| Mg (Gr) |

418 |

2076 |

743 |

| Mg (Ch) |

576 |

1629 |

954 |

| Mg (Ps) |

440 |

1343 |

979 |

| Mg (Pl) |

160 |

1070 |

670 |

| δ13C (Gr) |

0.64 |

3.79 |

2.70 |

| δ13C (Ch) |

0.57 |

2.63 |

1.90 |

| δ13C (Ps) |

1.39 |

3.23 |

2.70 |

| δ13C (Pl) |

1.32 |

2.22 |

1.86 |

| δ18O (Gr) |

-2.06 |

-0.67 |

-1.55 |

| δ18O (Ch) |

-3.16 |

-1.62 |

-2.14 |

| δ18O (Ps) |

-2.30 |

-1.57 |

-1.92 |

| δ18O (Pl) |

-2.46 |

-1.79 |

-2.03 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).