Submitted:

13 August 2025

Posted:

13 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Study Population and Enrollment Procedures

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Ethical Considerations

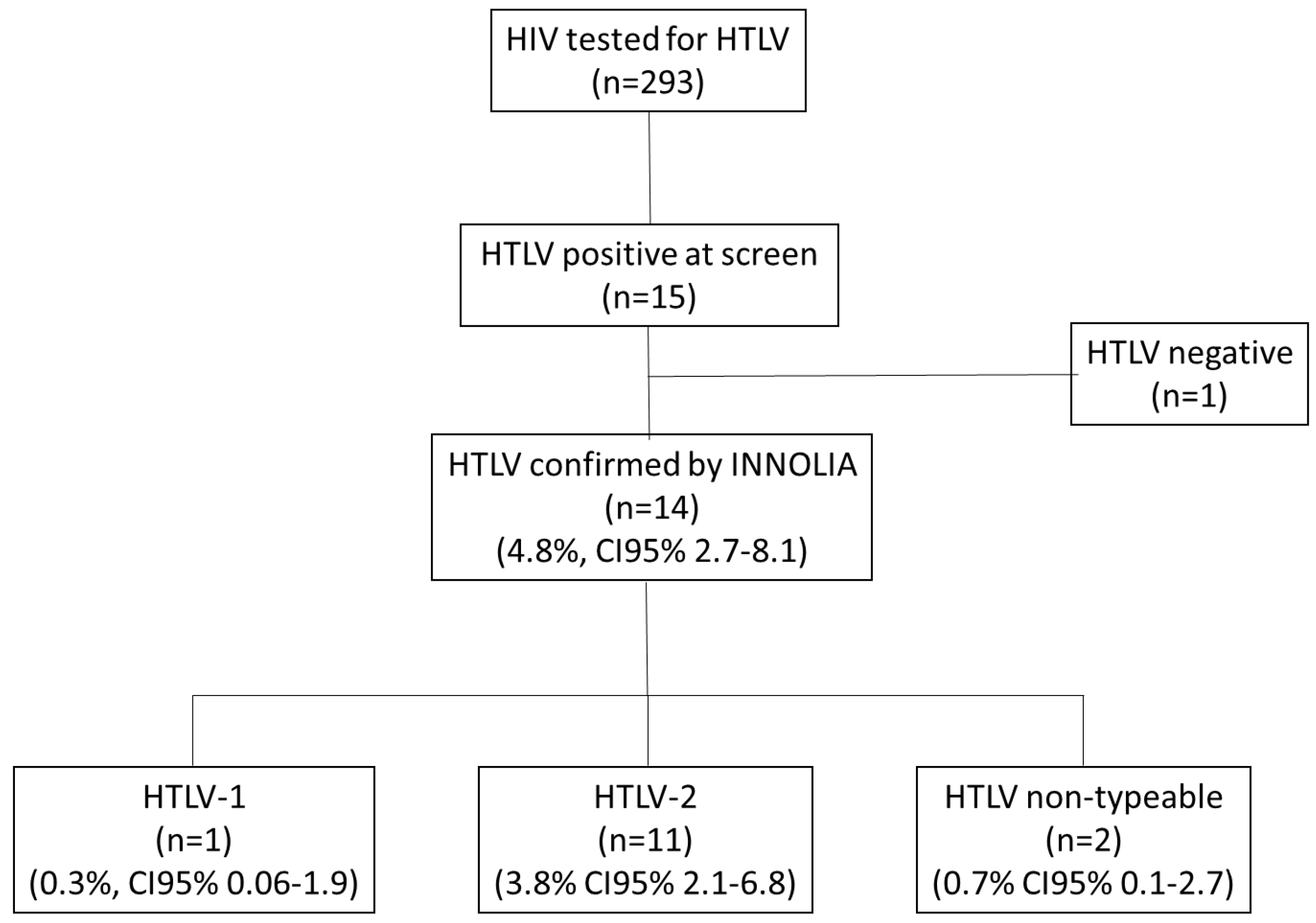

3. Results

3.1. Overview of the Study Population

3.2. HTLV Subtypes

3.3. Description of Co-Infection HTLV-HIV

3.4. Differences HTLV Positive vs. HTLV Negative

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HTLV | Human T-Cell Lymphotropic Virus |

| HIV | Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| PWH | People with HIV |

| ELISA | Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| IQRs | Interquartile Ranges |

| CIs | Confidence Intervals |

| ART | Anti-retroviral therapy. |

References

- Branda, F.; Romano, C.; Pavia, G.; Bilotta, V.; Locci, C.; Azzena, I.; Deplano, I.; Pascale, N.; Perra, M.; Giovanetti, M.; et al. Human T-Lymphotropic Virus (HTLV): Epidemiology, Genetic, Pathogenesis, and Future Challenges. Viruses 2025, 17, 664. [CrossRef]

- Legrand, N.; McGregor, S.; Bull, R.; Bajis, S.; Valencia, B.M.; Ronnachit, A.; Einsiedel, L.; Gessain, A.; Kaldor, J.; Martinello, M. Clinical and Public Health Implications of Human T-Lymphotropic Virus Type 1 Infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2022, 35, e0007821. [CrossRef]

- Solorzano-Salazar, D.M.; Hernández-Vásquez, A.; Visconti-Lopez, F.J.; Azañedo, D. Research on HTLV-1 and HTLV-2 in Latin America and the Caribbean over the last ten years. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13800. [CrossRef]

- Carneiro-Proietti, A.B.F.; Catalan-Soares, B.; Proietti, F.A. Human T Cell Lymphotropic Viruses (HTLV-I/II) in South America: Should It Be a Public Health Concern?. J. Biomed. Sci. 2002, 9, 587–595. [CrossRef]

- Abreu, I.N.; Lima, C.N.C.; Sacuena, E.R.P.; Lopes, F.T.; Torres, M.K.d.S.; dos Santos, B.C.; Freitas, V.d.O.; de Figueiredo, L.G.C.P.; Pereira, K.A.S.; de Lima, A.C.R.; et al. HTLV-1/2 in Indigenous Peoples of the Brazilian Amazon: Seroprevalence, Molecular Characterization and Sociobehavioral Factors Related to Risk of Infection. Viruses 2022, 15, 22. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira-Filho, A.B.; Araújo, A.P.S.; Souza, A.P.C.; Gomes, C.M.; Silva-Oliveira, G.C.; Martins, L.C.; Fischer, B.; Machado, L.F.A.; Vallinoto, A.C.R.; Ishak, R.; et al. Human T-lymphotropic virus 1 and 2 among people who used illicit drugs in the state of Pará, northern Brazil. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Ishak, R.; Ishak, M.d.O.G.; Azevedo, V.N.; Machado, L.F.A.; Vallinoto, I.M.C.; Queiroz, M.A.F.; Costa, G.d.L.C.; Guerreiro, J.F.; Vallinoto, A.C.R. HTLV in South America: Origins of a silent ancient human infection. Virus Evol. 2020, 6, veaa053. [CrossRef]

- Vieira, B.A.; Bidinotto, A.B.; Dartora, W.J.; Pedrotti, L.G.; de Oliveira, V.M.; Wendland, E.M. Prevalence of human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 and 2 (HTLV-1/-2) infection in pregnant women in Brazil: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Galetto, L.R.; Lunge, V.R.; Béria, J.U.; Tietzmann, D.C.; Stein, A.T.; Simon, D. Short Communication: Prevalence and Risk Factors for Human T Cell Lymphotropic Virus Infection in Southern Brazilian HIV-Positive Patients. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 2014, 30, 907–911. [CrossRef]

- Alencar, S.P.; Souza, M.d.C.; Fonseca, R.R.d.S.; Menezes, C.R.; Azevedo, V.N.; Ribeiro, A.L.R.; Lima, S.S.; Laurentino, R.V.; Barbosa, M.d.A.d.A.P.; Freitas, F.B.; et al. Prevalence and Molecular Epidemiology of Human T-Lymphotropic Virus (HTLV) Infection in People Living With HIV/AIDS in the Pará State, Amazon Region of Brazil. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 572381. [CrossRef]

- Etzel, A.; Shibata, G.Y.; Rozman, M.; Jorge, M.L.S.G.; Damas, C.D.; Segurado, A.A.C. HTLV-1 and HTLV-2 Infections in HIV-Infected Individuals From Santos, Brazil: Seroprevalence and Risk Factors. Am. J. Ther. 2001, 26, 185–190. [CrossRef]

- Caterino-De-Araujo, A.; Sacchi, C.T.; Gonçalves, M.G.; Campos, K.R.; Magri, M.C.; Alencar, W.K.; the Group of Surveillance and Diagnosis of HTLV of São Paulo (GSuDiHTLV-SP) Short Communication: Current Prevalence and Risk Factors Associated with Human T Lymphotropic Virus Type 1 and Human T Lymphotropic Virus Type 2 Infections Among HIV/AIDS Patients in São Paulo, Brazil. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 2015, 31, 543–549. [CrossRef]

- Tattsbridge, J.; Wiskin, C.; de Wildt, G.; Llavall, A.C.; Ramal-Asayag, C. HIV understanding, experiences and perceptions of HIV-positive men who have sex with men in Amazonian Peru: a qualitative study. BMC Public Heal. 2020, 20, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Zavaleta, C.; Fernández, C.; Konda, K.; Valderrama, Y.; Vermund, S.H.; Gotuzzo, E. HIGH PREVALENCE OF HIV AND SYPHILIS IN A REMOTE NATIVE COMMUNITY OF THE PERUVIAN AMAZON. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2007, 76, 703–705. [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, E.C.; Zavaleta, C.; Fernández, C.; Razuri, H.; Vilcarromero, S.; Vermund, S.H.; Gotuzzo, E. Expansion of HIV and syphilis into the Peruvian Amazon: a survey of four communities of an indigenous Amazonian ethnic group. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2008, 12, e89–e94. [CrossRef]

- Quiros-Roldan, E.; Moretti, F.; Torti, C.; Casari, S.; Castelli, F.; Beltrame, A.; Carosi, G. HIV/HTLV Co-infection: Frequency and Epidemiological Characteristics among Patients Admitted to an Italian Hospital. Infection 2003, 31, 172–173. [CrossRef]

- Islam, N.; Mili, M.A.; Jahan, I.; Chakma, C.; Munalisa, R. Immunological and Neurological Signatures of the Co-Infection of HIV and HTLV: Current Insights and Future Perspectives. Viruses 2025, 17, 545. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, F.M.; Santos, F.L.N.; Silva, Â.A.O.; Nascimento, N.M.; Almeida, M.d.C.C.; Carreiro, R.P.; Galvão-Castro, B.; Grassi, M.F.R. Distribution of Human Immunodeficiency Virus and Human T-Leukemia Virus Co-infection in Bahia, Brazil. Front. Med. 2022, 8, 788176. [CrossRef]

- La Rosa, A.M.; Zunt, J.R.; Peinado, J.; Lama, J.R.; Ton, T.G.N.; Suarez, L.; Pun, M.; Cabezas, C.; Sanchez, J.; Peruvian HIV Sentinel Surveillance Working Group Retroviral Infection in Peruvian Men Who Have Sex with Men. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009, 49, 112–117. [CrossRef]

- Abad-Fernández, M.; Hernández-Walias, F.J.; de León, M.J.R.; Vivancos, M.J.; Pérez-Elías, M.J.; Moreno, A.; Casado, J.L.; Quereda, C.; Dronda, F.; Moreno, S.; et al. HTLV-2 Enhances CD8+ T Cell-Mediated HIV-1 Inhibition and Reduces HIV-1 Integrated Proviral Load in People Living with HIV-1. Viruses 2022, 14, 2472. [CrossRef]

- Medeot, S.; Nates, S.; Recalde, A.; Gallego, S.; Maturano, E.; Giordano, M.; Serra, H.; Reategui, J.; Cabezas, C. Prevalence of antibody to human T cell lymphotropic virus types 1/2 among aboriginal groups inhabiting northern Argentina and the Amazon region of Peru.. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1999, 60, 623–629. [CrossRef]

- Maloney, E.M.; Biggar, R.J.; Neel, J.V.; Taylor, M.E.; Hahn, B.H.; Shaw, G.M.; Blattner, W.A. Endemic Human T Cell Lymphotropic Virus Type II Infection among Isolated Brazilian Amerindians. J. Infect. Dis. 1992, 166, 100–107. [CrossRef]

- Fani, M.; Rezayi, M.; Meshkat, Z.; Rezaee, S.A.; Makvandi, M.; Abouzari-Lotf, E.; Ferns, G.A. Current approaches for detection of human T-lymphotropic virus Type 1: A systematic review. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 12433–12441. [CrossRef]

- Campos, K.R.; Gonçalves, M.G.; Caterino-De-Araujo, A. Short Communication: Failures in Detecting HTLV-1 and HTLV-2 in Patients Infected with HIV-1. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 2017, 33, 382–385. [CrossRef]

- Hall, W.W.; Ishak, R.; Zhu, S.W.; Novoa, P.; Eiraku, N.; Takahashi, H.; Ferreira, M.d.C.; Azevedo, V.; Ishak, M.O.G.; Ferreira, O.d.C.; et al. Human T Lymphotropic Virus Type II (HTLV-II): Epidemiology, Molecular Properties, and Clinical Features of Infection. Am. J. Ther. 1996, 13, S204–S214. [CrossRef]

| Variables |

Overall (N=293) |

HTLV positive (N = 14) |

HTLV negative (N = 279) |

pvalue |

| Epidemiology | ||||

| Sex, male, n (%) | 196 (66.9%) | 9 (64.3) | 187 (66,9) | 0.789 |

| Age, median (IQR), years | 40 (30-49) | 55 (52-61) | 39 (29-47) | <0.001 |

| Age >50 years, n (%) | 72 (24.6) | 12 (85.7) | 60 (21.5) | <0.001 |

| Residence, n (%) | ||||

| Iquitos district | 97 (33.1) | 7 (50.0) | 90 (32.3) | 0.932 |

| Punchana district | 84 (28.7) | 4 (28.6) | 80 (28.7) | |

| San Juan district | 64 (21.8) | 64 (7.1) | 63 (22.6) | |

| Belen district | 33 (11.3) | 2 (14.3) | 31 (11.1) | |

| Outside of Iquitos city | 15 (5.1) | 0 (0.0) | 15 (5.3) | |

| Occupation, n (%) | ||||

| Unemployed or student | 111 (37.9) | 5 (35.7) | 106 (38.0) | 0.54 |

| Self-employment | 100 (34.1) | 5 (35.7) | 95 (34.1) | |

| Cattle, agriculture or construction | 47 (16.0) | 3 (21.4) | 44 (15.8) | |

| Intellectual work | 28 (9.8) | 0 (0.0) | 28 (10.7) | |

| Craft work | 7 (2.4) | 1 (7.1) | 6 (2.2) | |

| Education, n (%) | ||||

| None or only attended primary school | 49 (16.7) | 5 (35.7) | 44 (15.4) | 0.05 |

| Attended secondary school or university | 244 (83.3) | 9 (64.3) | 235 (84.2) | |

| Epidemiological risk factors, n (%) | ||||

| Breastfeeding | 277 (94.5) | 13 (92.9) | 264 (94.6) | 0.55 |

| Blood transfusion | 64 (21.8) | 3 (21.4) | 61 (21.9) | 1.0 |

| Comorbidity, n (%) | ||||

| Diabetes or high blood pressure | 21 (7.2) | 2 (14.3) | 19 (6.8) | 0.26 |

| Digestive disease | 12 (4.1) | 2 (14.39 | 10 (3.6) | 0.10 |

| Other cardiovascular disease | 10 (3.49 | 1 (7.1) | 9 (3.2) | 0.39 |

| Previous infections, n (%) | ||||

| Strongyloides serology positive | 167 (57.0) | 6 (42.9) | 161 (57.7) | 0.29 |

| Tuberculosis test positive | 55 (18.8) | 4 (28.6) | 51 (18.3) | 0.30 |

| Prior Gonorrhea | 33 (11.3) | 3 (21.4) | 30 (10.8) | 0.20 |

| Prior Syphilis | 41 (14.0) | 3 (21.3) | 38 (13.6) | 0.42 |

| Chronic hepatitis | 19 (6.5) | 2 (14.3) | 17 (6.7) | 0.23 |

| Prior Cerebral toxoplasmosis | 13 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) | 13 (4.7) | 0.41 |

| HIV acquisition, n (%) | ||||

| Sexual | 263 (89.9) | 12 (85.7) | 251 (90.0) | 0.71 |

| Vertical | 2 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.1) | |

| Unknown | 27 (9.2) | 2 (14.39 | 25 (9.0) | |

| Virology, Immunology and Adherence of treatment | ||||

| Nadir CD4+/uL, median (IQR) | 228 (109-363) | 213 (123-360) | 230 (109-363) | 0.91 |

| Current CD4+, median (IQR) | 446 (303-597) | 455 (385-613) | 441 (299-593) | 0.47 |

| Current CD4+ < 200/mL n (%) | 22 (10.7) | 0 (0.0) | 22 (11.3) | 0.61 |

| Current undetectable HIV viral load (< 20 copies/ml), n (%) | 216 (76.3) | 12 (92.39 | 204 (75.6) | 0.31 |

| Poor ART adherence, ≤ 95%), n (%) | 22 (13.4) | 2 (15.4) | 30 (13.3) | 0.89 |

| N |

Type of HTLV |

Age | Sex | Ethnicity |

Origin of parents |

Breast- feeding |

Sexual behavior/ number of sexual partners |

Non-sterilized proceduresa |

Transfusion |

Living in rural areab |

Chronic hepatitis |

ITS |

CD4 count nadir/last |

HIV viral load |

| 1 | HTLV-1 | 62 | M | Mestizo | Tarapoto | Yes | Transexual / < 5 | No | Yes | No | No | No | 479 / 677 | < 20 |

| 2 | HTLV-2 | 52 | M | Mestizo | Iquitos | Yes | Homosexual / < 5 | No | No | No | No | No | 218 / 674 | < 20 |

| 3 | HTLV-2 | 56 | M | Kukuma | Marañón River | Yes | Homosexual / < 5 | No | No | No | No | No | 287 / 684 | < 20 |

| 4 | HTLV-2 | 60 | F | Mestizo | Nauta | Yes | Heterosexual / >5 | No | No | No | No | No | 113 / 113 | < 20 |

| 5 | HTLV-2 | 61 | M | Mestizo | Requena | Yes | Heterosexual / >5 | No | Yes | No | No | No | 134 / 322 | < 20 |

| 6 | HTLV-2 | 53 | M | Mestizo | Cuzco | Yes | Bisexual / > 5 | No | Yes | No | Yes | Gonorrhea Syphilis |

52 / 371 | < 20 |

| 7 | HTLV-2 | 60 | M | Mestizo | LOF | Yes | Heterosexual / LOF | LOF | No | No | Yes | No | NA | < 20 |

| 8 | Non-typable HTLV |

43 | F | Mestizo | Pebas | Yes | Heterosexual / <5 | No | No | No | No | No | 261 / 261 | < 20 |

| 9 | Non-typable HTLV |

55 | M | Mestizo | Iquitos | Yes | Heterosexual / <5 | No | No | No | No | Gonorrhea Syphilis |

455 / 455 | < 20 |

| 10 | HTLV-2 | 54 | F | Mestizo | Marañón River | Yes | Heterosexual / >5 | Scarification | No | No | No | Syphilis | 76 / 525 | < 20 |

| 11 | HTLV-2 | 64 | M | Mestizo | LOF | Yes | Heterosexual / LOF | LOF | No | No | No | No | 171 / 399 | < 20 |

| 12 | HTLV-2 | 66 | F | Mestizo | Ucayali River | Yes | Heterosexual / <5 | No | No | No | No | No | 519 / 519 | < 20 |

| 13 | HTLV-2 | 45 | M | Mestizo | Iquitos | Yes | Heterosexual / <5 | No | No | No | No | No | 434 / 434 | < 20 |

| 14 | HTLV-2 | 50 | M | Mestizo | Iquitos | No | Heterosexual / <5 | No | No | No | No | Gonorrhea |

344 / 344 | < 20 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).