Submitted:

12 August 2025

Posted:

13 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Campylobacter in Broilers –Biology and Public Health Impact

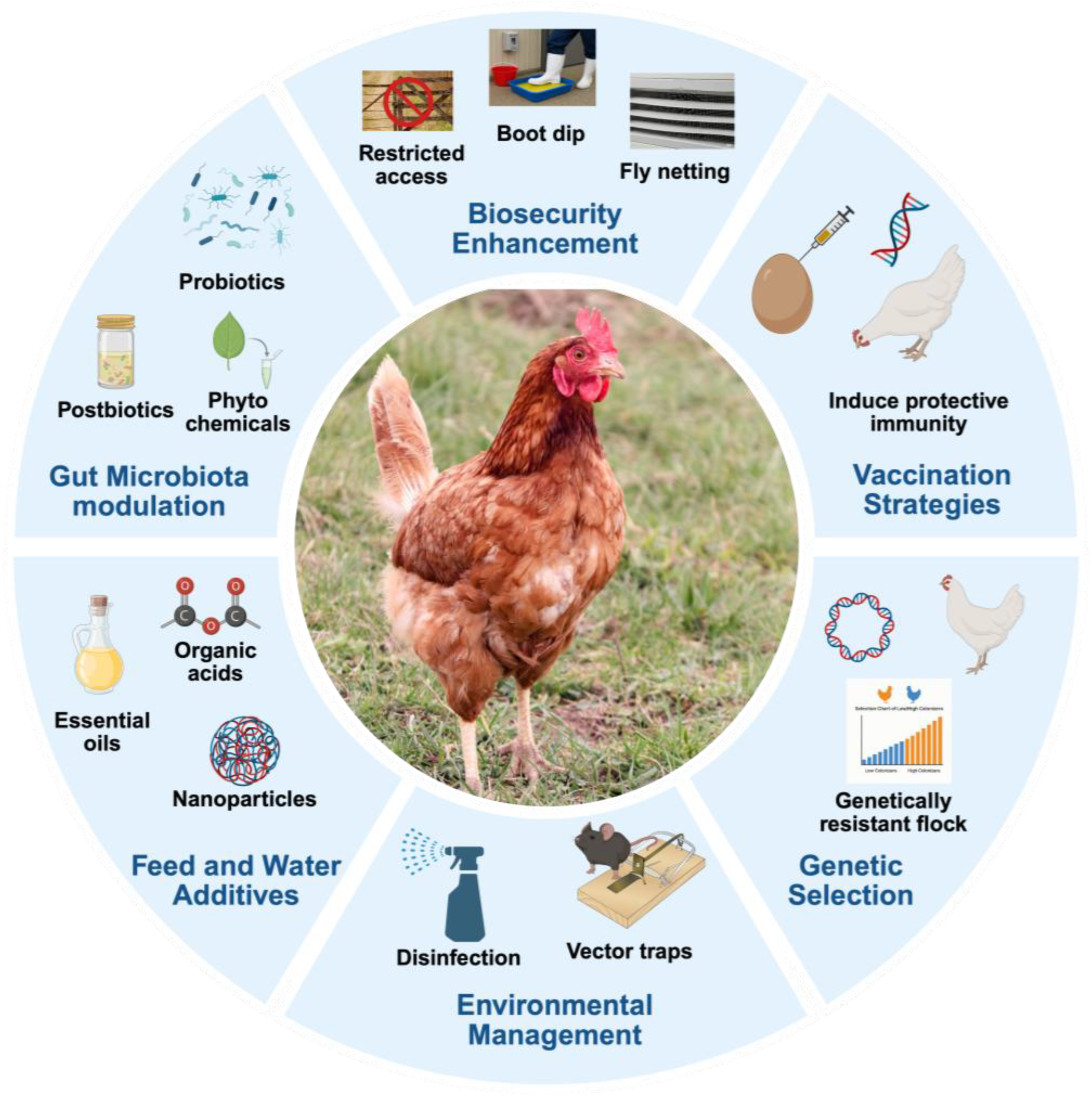

3. Overview of Preharvest Control Strategies

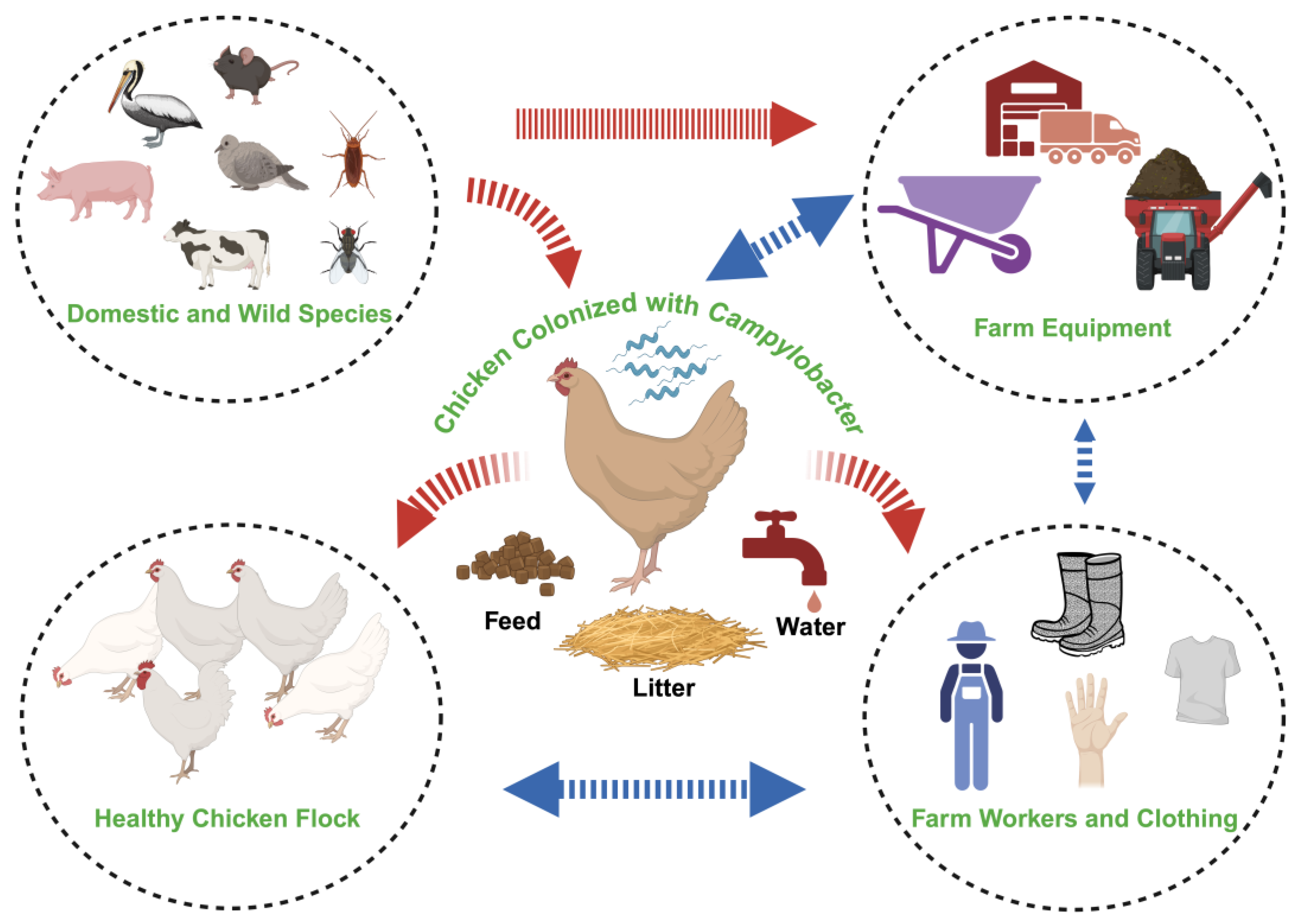

3.1. Biosecurity Measures

3.1.1. Managing Human Entry and Hygiene to Prevent Contamination

3.1.2. Equipment and Vehicle Sanitation

3.1.3. Pest and Wildlife Control

3.2. Probiotics, Prebiotics and Postbiotics

3.3. Bacteriophage Application in Campylobacter Control

3.4. Feed Additives

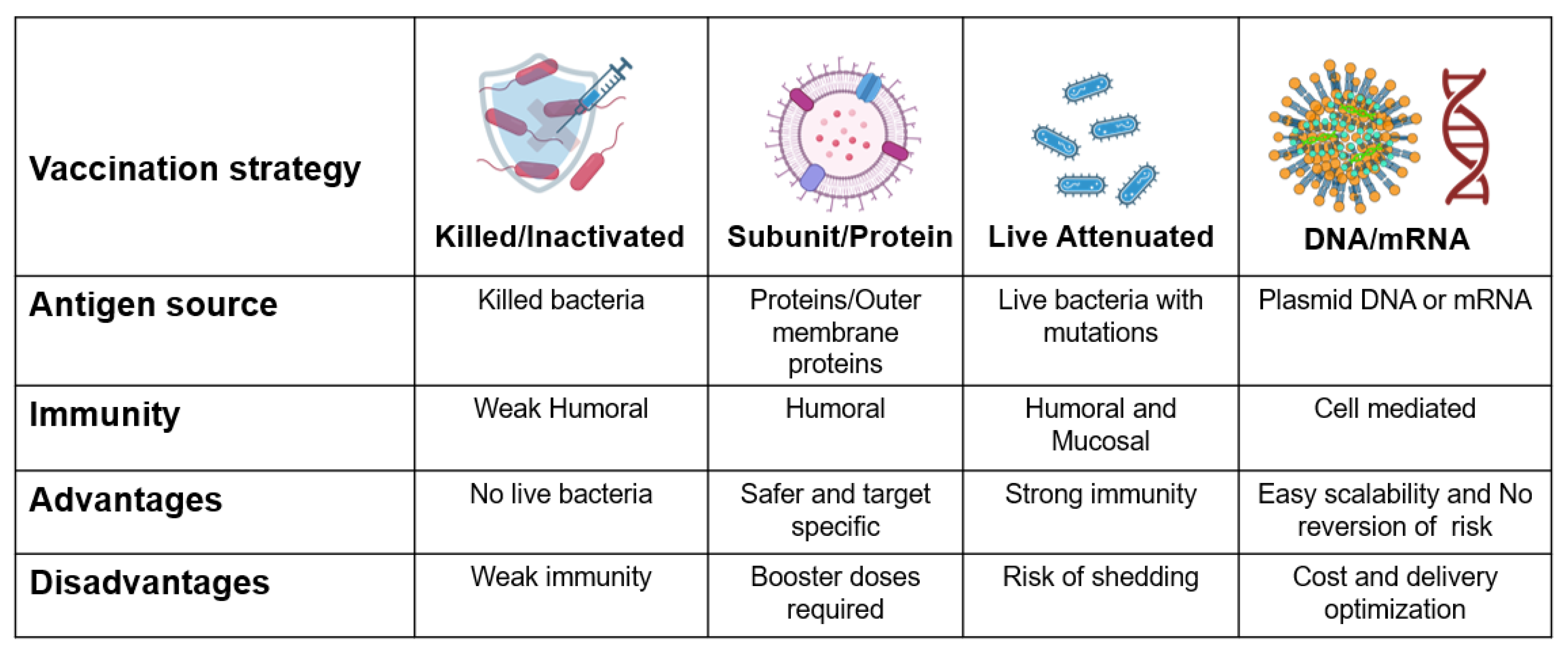

3.5. Vaccination – A Targeted Approach

3.5.1. Types of Poultry Campylobacter Vaccines

3.5.1.1. Subunit Vaccines

3.5.1.2. Live-Attenuated Vaccines

3.5.1.3. Inactivated/Killed Vaccines

3.5.1.4. DNA and mRNA Vaccines

3.5.2. Challenges in Campylobacter Vaccine Development

3.5.2.1. Campylobacter Properties

3.5.2.2. Host Factors Influencing Vaccinal Immunity

3.5.2.3. Administration and Management of Vaccines

3.5.3. Success Stories and Promising Campylobacter Vaccine Candidates

3.5.3.1. Autogenous Vaccines

3.5.3.2. Subunit Vaccines

3.5.3.3. Live Attenuated Vaccines

3.5.3.4. DNA Vaccine

| Vaccine | Chicken breed (chicken type) |

Age at Vaccination | Vaccination regimen |

Challenge |

Reduction in levels (mean log10 CFU/gram) of Campylobacter | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Strain (dose) | |||||||

| Live attenuated Salmonella vaccine expressing CfrA or CmeC proteins | Cornish x Rock (broiler) | Day 7 | Oral administration of 200 μl of Salmonella (1×109 CFU/ml) expressing CfrA or CmeC | Day 28 | C. jejuni NCTC 11168 (2×103 CFU/bird) | No significant reduction | [160] | |

| Nanoparticle-encapsulated OMPs of C. jejuni 81–176 |

Not specified | Day 7 and Day 21 |

Oral administration of 25 or 125 µg of nanoparticle-encapsulated OMPs or OMPs alone | Day 35 |

C. jejuni 81–176 (2×107 CFU/bird) | No significant reduction |

[221] | |

| Subcutaneous administration of 25 or 125 µg of nanoparticle-encapsulated OMPs or OMPs alone | ||||||||

| Live Salmonella Typhimurium ΔaroA strain expressing CjaA of C. jejuni | Light Sussex (broiler) | Day 1 and Day 14 | Oral gavage of 0.3 ml of stationary phase culture (1×108 CFU/ml) | Day 28 | C. jejuni M1 (1×107 CFU/bird) | Significant 1.4 log10 CFU/g reduction | [211] | |

| Purified recombinant CjaA | Light Sussex chickens (broiler) | Day 1 and Day 15, or Day 15 and Day 29 | Subcutaneous administration of 14 μg of rCjaA with TiterMax adjuvant | Day 29/Day 44 | No significant reduction | |||

| Autogenous poultry vaccine | Ross (broiler) | 14 and 18 weeks of age | Intramuscular administration of 0.5 ml of oil-based autogenous vaccine | Not a challenge study | Measured natural colonization | No significant reduction | [220] | |

| FliD and FspA | White Leghorn (layer) | Day 1 and Day 14 | Subcutaneous administration of 4.3×1010 moles of each recombinant protein, FliD and FspA, with TiterMax Gold adjuvant | Day 28 |

C. jejuni M1 (1×107 CFU/bird) |

2 log10 CFU/g in reduction with FliD (statistically significant) | [228] | |

| Eimeria tenella-expressing CjaA | White Leghorn (layer) | Group 1: Day 1 Group 2: 1/3/7/20 | Oral administration of 100, 500, 3000, and 5000 fourth-generation CjaA-transfected parasites | Day 28 | C. jejuni 02M6380 (1×105 CFU/bird) | One order reduction (statistically significant) | [229] | |

| FlpA with ten N-heptasaccharide glycan Moieties | White Leghorn (layer) | Day 0 and Day 14 | Subcutaneous administration of 100 μg of FlpA with TiterMax Gold or the molar equivalent of FlpA-10×GT in 100 µl | Day 28 | C. jejuni NCTC11168H (1 × 105 CFU/bird ) | No significant reduction | [230] | |

| Ent–KLH conjugate vaccine | White Leghorn (layer) | Day 7, Day 21, and Day 35 | Intramuscular administration of 100 μg of Ent–KLH conjugate vaccine with Montanide adjuvant | Day 49 | C. jejuni (1 × 104 CFU/bird ) | 3-4 log10 unit reduction in the cecum (statistically significant) | [231] | |

| White Leghorn (layer) | Day 7 and Day 21 | Intramuscular administration of 100 μg of Ent–KLH conjugate vaccine with Montanide adjuvant | Day 35 | C. jejuni ( 1× 104 CFU/bird ) | 3-4 log10 unit reduction in the cecum (statistically significant) | |||

| Recombinant YP437 protein | Ross 308 (broiler) | Day 5 and Day 12 | Intramuscular administration of 100 µg of recombinant YP437 protein (YP437 I2, P I2, YP437 I4, and P I4) emulsified with adjuvant MONTANIDETM ISA 78 VG | Day 19 | C. jejuni (1×104 CFU/bird) | No significant reduction | [232] | |

| Plasmid DNA prime/recombinant protein boost vaccination (YP437 and YP9817) | Ross 308 (broiler) | Day 12 | Intramuscular administration of 100 µg of recombinant protein emulsified in MONTANIDE™ ISA 78 VG | Day 19 | C. jejuni C97Anses640 ( 1× 104 CFU/bird) | No significant reduction | [181] | |

| Ross 308 (broiler) | Day 5 | Intramuscular administration of 50 μg of plasmid DNA | ||||||

| Lactococcus lactis expressing JlpA | Vencobb (broiler) | Day 7 |

Oral gavage of 1x109 CFU /100 µl of Lactococcus lactis expressing recombinant JlpA | Day 28 | C. jejuni isolate BCH71 (1×108 CFU/bird) | No significant reduction |

[233] | |

| Subcutaneous administration of 50 µg of recombinant JlpA emulsified in incomplete Freund's adjuvant | ||||||||

| Bacterin vaccine (Mix of 13 Campylobacter suspensions) | Ross 308 (broiler) | 28, 30, 32, and 34 weeks |

Intramuscular administration of 8.1 log10 CFU inactivated Campylobacter (7 log10 CFU/Campylobacter strain) | Day 7 Day 14 Day 21 |

C. jejuni

strain KC40 (102.5 and 103.5 CFU/bird) |

No significant reduction |

[203] | |

| Subunit vaccine (6 immunodominant Campylobacter antigens) | Ross 308 (broiler) | Intramuscular administration of 75 µg of protein with Freund's complete and incomplete adjuvant | ||||||

| Diphtheria toxoid C. jejuni capsular polysaccharide- vaccine (CPSconj) | Ross 308 (broiler) | Day 7 and Day 21 | Subcutaneous administration of 25 μg of CPSconj with 10 μg CpG or 100 μl Addavax adjuvant | Day 29 | C. jejuni 81-176 (2×107 CFU/bird) | 0.64 log10 reduction (statistically significant) | [234] | |

| Chitosan/pCAGGS-flaA nanoparticles | White Leghorn (layer) | Day 1, Day 15, and Day 29 | Intranasal administration of 150 μg chitosan/pCAGGS-flaA nanoparticles | Day 42 | C. jejuni ALM-80 (5×107 CFU/bird) | 2 log10 in the cecum (statistically significant) | [222] | |

| LT-B/fla hybrid protein | Breed not specified (broiler) | Day 7 and Day 21 | Oral administration of 250 μg, 500 μg, 750 μg, and 1mg of LT-B/fla hybrid protein; intramuscular administration of 250µg, and 1 mg of LT-B/Fla hybrid protein | Day 28 | C. jejuni A74 (2x108 CFU/bird) | Statistically significant reduction of the number of Campylobacter positive birds | [213] | |

| CjaA, CjaD, and hybrid protein rCjaAD of C. jejuni |

Hy-line (layer) | Day 1, Day 9, and Day 19 | Oral or subcutaneous administration of 2.5×109 CFU of L. salivarius GEM particles with CjaALysM and CjaDLysM | Day 30 | C. jejuni 12/2 (1x104 CFU/bird) | No significant reduction |

[213] |

|

| Rosa 1 (broiler) | 18-day-old embryo | In ovo administration of 0.1 ml of inoculum rCjaAD with GRM s particles or liposomes into the amniotic fluid | Day 14 | C. jejuni 12/2 (1x106 CFU/bird) | Statistically significant reduction of cecal loads of Campylobacter | |||

| Live attenuated Salmonella Typhimurium strain expressing C. jejuni CjaA | Cobb 500 (broiler) | Day 1 and Day 14 | Oral administration of ~108 CFU of S. Typhimurium strain χ9718 harboring pUWM1161 (Asd+ vector carrying the cjaA gene) | Day 28 | C. jejuni Wr1 (1x105 CFU/bird) | No significant reduction |

[235] | |

| Live attenuated Salmonella expressing linear peptides of C. jejuni (Cj0113, Cj0982c, and Cj0420) | Cobb-500 (broiler) | Day 1 |

Oral gavage of 108 CFU/ml Salmonella | Day 21 | C. jejuni PHLCJ1-J3 (2.5×106 CFU/bird) | 4.8-log reduction in the ileum with Cj0113 (statistically significant) | [210] | |

| 4-log reduction - undetectable level in the ileum with Cj0113 (statistically significant) | ||||||||

| Live attenuated Salmonella expressing linear peptides of C. jejuni (Cj0113) | Oral gavage of 108 CFU/ml Salmonella 108 CFU/ml | |||||||

| CmeC and CfrA | Cobb 500 (broiler) | 18-day-old embryo | In ovo administration of 50 µg pCmeC-K or 50 µg pCfrA into the amniotic fluid | Day 14 | C. jejuni NCTC 11168 (5×107 CFU/bird) | No significant reduction | [180] | |

| In ovo administration of DNA vaccines emulsified with incomplete Freund’s adjuvant | Day 21 | No significant reduction |

||||||

| pcDNA3-YP DNA vaccines YP_001000437.1, YP_001000562.1, YP_999817.1, and YP_999838.1 | Ross PM3 (broiler) | Day 5 and Day 12 | Intramuscular administration of with 300 μg of pcDNA3-YP, supplemented with 50 μg of unmethylated CpG ODN2007 followed by intramuscular administration of 100 μg of recombinant proteins emulsified in MONTANIDE™ ISA70 VG | Day 19 | C. jejuni C97Anses640 (1×105 CFU/bird) | 2.03, 3.61, 4.27 and 2.08 log 10 reductions of P562, YP437, YP9817 and P9838 groups, respectively (statistically significant) | [226] | |

| Intramuscular administration of with 300 μg of pcDNA3-YP9817, supplemented with 50 μg of unmethylated CpG ODN2007 followed by intramuscular administration of 100 μg of recombinant proteins emulsified in MONTANIDE™ ISA70 VG | No significant reduction | |||||||

| CmeC | Breed not specified (broiler) | Day 7 and Day 21 |

Oral gavage with 50 or 200 μg of CmeC vaccine with or without with 10 μg of mLT |

Day 35 |

C. jejuni NCTC 11168 (1×106 CFU/bird) | No significant reduction | [236] | |

| White Leghorn chickens (layer) | Day 21 and Day 35 |

Oral and subcutaneous administration of 50 or 200 μg of CmeC vaccine with or without 70 μg of mLT | Day 49 | C. jejuni NCTC 11168 (1×105 CFU/bird) | No significant reduction |

|||

| Lactococcus lactis NZ3900/pNZ8149 expressing cjaA | White leghorn (layer) |

Day 5 to 11, and Day 19 to 25 |

Oral administration of 2 × 1010 CFU of L. lactis NZ3900-sCjaA-Ltb, NZ3900-sCjaA, NZ3900-pNZ8149s, and NZ3900-pNZ8149 | Day 33 | C. jejuni NCTC 11168 (1.5 × 106 CFU/bird) | 2.35 log10 and 2.05 log10 reduction with NZ3900-sCjaA vaccine group at post 5 DPI (statistically significant) | [162] | |

| Glycoproteins of FlpA and SodB | White Leghorn (layer) | Day 6 and Day 16 | Intramuscular administration of 240 µg of FlpA and G-FlpA or 138 µg of SodB and G-SodB. | Day 20 | C. jejuni M1 (1×107 CFU/bird) | No significant reduction | [237] | |

| C. jejuni M1 (102 CFU/bird) | No significant reduction | |||||||

| Glycoprotein G-ExoA | White Leghorn (layer) | Day 6 and Day 16 | Intramuscular administration of 95 µg protein of ExoA or G-ExoA with MontanideTM ISA 70 VG adjuvant | Day 20 | C. jejuni M1 (1×102 CFU/bird) | Reduction on Day 37 with ExoA-vaccinated group (statistically significant) | [238] | |

| C. jejuni 11168H. C. jejuni M1 (1×104 CFU/bird) | Reduction on Day 37 with ExoA and G-ExoA-vaccinated groups (statistically significant) | |||||||

| Bacterin and subunit vaccine | Ross 308 (broiler) | 18-day-old embryo | In ovo administration of 7.4 log10 CFU inactivated Campylobacter/bacterin dose of bacterin vaccine injected into the amniotic cavity | Day 19 | C. jejuni KC4 (1 × 107 CFU/bird) | No significant reduction | [239] | |

| In ovo administration of 28.5 μg of 6 immunodominant Campylobacter antigens with ESSAI IMS 1505101OVO1 adjuvant | ||||||||

| C. jejuni Dps | Cornish × Rock (broiler) | Day 10 and Day 24 | Subcutaneous administration of 0.2 mg recombinant Dps protein with Freund's complete adjuvant | Day 34 | C. jejuni NCTC11168 (1×105 CFU/bird) | No reduction | [224] | |

| Day 3, Day 10, and Day 16 | Oral gavage of Salmonella Typhimurium strain χ9088 expressing C. jejuni Dps in 0.5 ml | Day 26 | 2.92 log10 reduction (statistically significant) | |||||

| PLGA-encapsulated CpG ODN | Breed is not specified (layer) | Day 14 | Oral administration of 5 µg or 50 µg of soluble CpG | Day 15 | C. jejuni (107 CFU/bird) | 1.23 and 1.32 log reduction at 8-day post infection with low and high dose, respectively (statistically significant) | [240] | |

| Breed is not specified (layer) | Oral administration of 5 µg E-CpG | 0.9, 1.9 and 1.89 log reduction at 8, 15 and 22 days of post-infection (statistically significant) | ||||||

| Breed is not specified (layer) | Oral administration with a high dose of E-CpG (25 µg) | 1.46 log10 reduction at day 22 post-infection (statistically significant) | ||||||

| Breed is not specified (broiler) | Oral administration of a low dose of C. jejuni lysate (4.3 µg protein) | 2.14 and 2.14 log10 at day 8 and day 22 post-infection, respectively (statistically significant) | ||||||

| Breed is not specified (broiler) | Oral administration of combination of E-CpG ODN (25 µg) and C. Oral administration of a combination of E-CpG ODN (25 µg) and C. jejuni lysate (4.3 µg protein) | 2.42 log10 at day 22 post-infection (statistically significant) | ||||||

| C. jejuni Type VI secretion system (T6SS) protein Hcp | Vencobb (broiler) | Day 7, Day 14, and Day 21 | Oral gavage of 50 μg rhcp loaded CS-TPP NPs (CS-TPP-Hcp) | Day 28 | C. jejuni isolate BCH71 (1×108 CFU/bird) | 1 log reduction (statistically significant) | [241] | |

| Subcutaneous administration of 50 μg of rhcp emulsified with Incomplete Freund’s adjuvant | 0.5 log reduction (statistically significant) | |||||||

| Recombinant NHC flagellin | Ross 308 (broiler) | 18.5-day-old embryo | In ovo administration of 40 or 20 μg NHC flagellar protein with 10 mM Tris (pH 9.0), 20% glycerol, 5 mM sucrose | day 18 | C. jejuni ( 1× 105 CFU/bird ) | No significant reduction |

[242] | |

| Recombinant C. jejuni peptides of CadF, FlaA, FlpA, CmeC, and CadF-FlaA-FlpA fusion protein | Cornish cross (broiler) | Day 6 and Day 16 |

Intramuscular administration of 240 µg of GST-tagged 90 mer peptides or equal mixure of CadF-His, FlaA-His, and FlpA-His (trifecta group) emulsified in Montanide ISA 70 VG | Day 20 | C. jejuni (2×108 CFU/bird) | 3.1, 3.3, 3.1, and 1.7 log reductions observed with Trifecta, FlpA, FlaA and CadF, respectively (statistically significant) | [163] | |

4. Conclusion and Future Perspectives of Campylobacter Control:

4.1. Future Prospects:

4.1.1. Biosecurity Enhancing Innovations

4.1.2. Studies Targeting Campylobacter and Host Interactions

4.1.3. Genetic Selection of Campylobacter-Resistant Breeds

4.1.4. Developing Effective Vaccination Strategies

4.1.5. Microbiota Targeting Interventions

4.1.6. Cross-Sectoral Collaboratory Efforts (One Health)

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMR | Antimicrobial resistance |

| CFU | Colony forming units |

| EOs | Essential oils |

| FMT | Fecal microbiota transplantation |

| FOS | Fructooligosaccharides |

| GBS | Guillain-Barré Syndrome |

| GIT | Gastrointestinal tract |

| GLAT | Gut-associated lymphoid tissue |

| GOS | Galactooligosaccharides |

| IBS | Irritable bowel syndrome |

| IMO | Isomalto-oligosaccharides |

| MHC | Major histocompatibility complex |

| PPE | Personal protective equipment |

| QTL | Quantitative Trait Loci |

| VBNC | Viable but non-culturable state |

References

- Scallan, E.; Hoekstra, R.M.; Angulo, F.J.; Tauxe, R. V.; Widdowson, M.A.; Roy, S.L.; Jones, J.L.; Griffin, P.M. Foodborne Illness Acquired in the United States-Major Pathogens. Emerg Infect Dis 2011, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, S.M.; Devleesschauwer, B. Estimates of Global Disease Burden Associated with Foodborne Pathogens. In Foodborne Infections and Intoxications; 2021.

- Prevention, C. for D.C. and Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States 2019. Cdc 2019.

- Hermans, D.; Pasmans, F.; Heyndrickx, M.; Van Immerseel, F.; Martel, A.; Van Deun, K.; Haesebrouck, F. A Tolerogenic Mucosal Immune Response Leads to Persistent Campylobacter Jejuni Colonization in the Chicken Gut. Crit Rev Microbiol 2012, 38, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrano, L.D.; Levy, K.; Menezes, N.P.; Freeman, M.C. Human Diarrhea Infections Associated with Domestic Animal Husbandry: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2014, 108, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, G.V.; Ramires, T.; Kleinubing, N.R.; Scheik, L.K.; Fiorentini, Â.M.; Padilha da Silva, W. Virulence Factors of Foodborne Pathogen Campylobacter Jejuni. Microb Pathog 2021, 161. [Google Scholar]

- Kaakoush, N.O.; Castaño-Rodríguez, N.; Mitchell, H.M.; Man, S.M. Global Epidemiology of Campylobacter Infection. Clin Microbiol Rev 2015, 28, 687–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finsterer, J. Triggers of Guillain–Barré Syndrome: Campylobacter Jejuni Predominates. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Nyati, K.K.; Prasad, K.N.; Rizwan, A.; Verma, A.; Paliwal, V.K. TH1 and TH2 Response to Campylobacter Jejuni Antigen in Guillain-Barré Syndrome. Arch Neurol 2011, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, S.; Prasad, K.N.; Jain, D.; Nyati, K.K.; Pradhan, S.; Agrawal, S. Immunoglobulin IgG Fc-Receptor Polymorphisms and HLA Class II Molecules in Guillain-Barré Syndrome. Acta Neurol Scand 2010, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, J.; Spadaro, A.; Koyfman, A.; Long, B. High Risk and Low Prevalence Diseases: Guillain-Barré Syndrome. American Journal of Emergency Medicine 2024, 75. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, J.A.; Willison, H.J. Guillain-Barré Syndrome: A Century of Progress. Nat Rev Neurol 2016, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Gölz, G.; Rosner, B.; Hofreuter, D.; Josenhans, C.; Kreienbrock, L.; Löwenstein, A.; Schielke, A.; Stark, K.; Suerbaum, S.; Wieler, L.H.; et al. Relevance of Campylobacter to Public Health–the Need for a One Health Approach. International Journal of Medical Microbiology 2014, 304, 817–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, O.; Morishita, T.Y.; Zhang, Q. Campylobacter Colonization in Poultry: Sources of Infection and Modes of Transmission. Animal health research reviews / Conference of Research Workers in Animal Diseases 2002, 3, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, S.M. The Significance of Campylobacter Jejuni Infection in Poultry: A Review. Avian Pathology 1992, 21, 189–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, N.J.; Clavero, M.R.; Bailey, J.S.; Cox, N.A.; Robach, M.C. Campylobacter Spp. in Broilers on the Farm and after Transport. Poult Sci 1995, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corry, J.E.; Atabay, H.I. Poultry as a Source of Campylobacter and Related Organisms. Symp Ser Soc Appl Microbiol 2001, 96S–114S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.D.; Newell, D.G. Campylobacter in Poultry: Filling an Ecological Niche. Avian Dis 2006, 50, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagenaar, J.A.; Van Bergen, M.A.P.; Mueller, M.A.; Wassenaar, T.M.; Carlton, R.M. Phage Therapy Reduces Campylobacter Jejuni Colonization in Broilers. Vet Microbiol 2005, 109, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, S.; Chaloner, G.; Kemmett, K.; Davidson, N.; Williams, N.; Kipar, A.; Humphrey, T.; Wigley, P. Campylobacter Jejuni Is Not Merely a Commensal in Commercial Broiler Chickens and Affects Bird Welfare. mBio 2014, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.K.; AbuOun, M.; Cawthraw, S.A.; Humphrey, T.J.; Rothwell, L.; Kaiser, P.; Barrow, P.A.; Jones, M.A. Campylobacter Colonization of the Chicken Induces a Proinflammatory Response in Mucosal Tissues. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 2008, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meade, K.G.; Narciandi, F.; Cahalane, S.; Reiman, C.; Allan, B.; O’Farrelly, C. Comparative in Vivo Infection Models Yield Insights on Early Host Immune Response to Campylobacter in Chickens. Immunogenetics 2009, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Zoete, M.R.; Keestra, A.M.; Roszczenko, P.; Van Putten, J.P.M. Activation of Human and Chicken Toll-like Receptors by Campylobacter Spp. Infect Immun 2010, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, W.A.; Molnár, A.; Aschenbach, J.R.; Ghareeb, K.; Khayal, B.; Hess, C.; Liebhart, D.; Dublecz, K.; Hess, M. Campylobacter Infection in Chickens Modulates the Intestinal Epithelial Barrier Function. Innate Immun 2015, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, W.D.K.; Close, A.J.; Humphrey, S.; Chaloner, G.; Lacharme-Lora, L.; Rothwell, L.; Kaiser, P.; Williams, N.J.; Humphrey, T.J.; Wigley, P.; et al. Cytokine Responses in Birds Challenged with the Human Food-Borne Pathogen Campylobacter Jejuni Implies a Th17 Response. R Soc Open Sci 2016, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawshaw, T.R.; Chanter, J.I.; Young, S.C.L.; Cawthraw, S.; Whatmore, A.M.; Koylass, M.S.; Vidal, A.B.; Salguero, F.J.; Irvine, R.M. Isolation of a Novel Thermophilic Campylobacter from Cases of Spotty Liver Disease in Laying Hens and Experimental Reproduction of Infection and Microscopic Pathology. Vet Microbiol 2015, 179, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van, T.T.H.; Elshagmani, E.; Gor, M.C.; Scott, P.C.; Moore, R.J. Campylobacter Hepaticus Sp. Nov., Isolated from Chickens with Spotty Liver Disease. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2016, 66, 4518–4524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharbi, M.; Béjaoui, A.; Hamrouni, S.; Arfaoui, A.; Maaroufi, A. Persistence of Campylobacter Spp. in Poultry Flocks after Disinfection, Virulence, and Antimicrobial Resistance Traits of Recovered Isolates. Antibiotics 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibreel, A.; Taylor, D.E. Macrolide Resistance in Campylobacter Jejuni and Campylobacter Coli. J Antimicrob Chemother 2006, 58, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfredson, D.A.; Korolik, V. Antibiotic Resistance and Resistance Mechanisms in Campylobacter Jejuni and Campylobacter Coli. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2007, 277. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, E.; Jeon, B. Contribution of Surface Polysaccharides to the Resistance of Campylobacter Jejuni to Antimicrobial Phenolic Compounds. Journal of Antibiotics 2015, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.R.T.; Fliss, I.; Biron, E. Insights in the Development and Uses of Alternatives to Antibiotic Growth Promoters in Poultry and Swine Production. Antibiotics 2022, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Wickramasuriya, S.S.; Ault, J.; Ritchie, S.; Gay, C.G.; Lillehoj, H.S. Alternatives to Antibiotic Growth Promoters for Poultry: A Bibliometric Analysis of the Research Journals. Poult Sci 2024, 103, 103987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phongsisay, V.; Strachan, N.J.C.; Forbes, K.J.; Efsa; Nauta, M.N.J.; Johannessen, G.; Laureano Adame, L.; Williams, N.; Rosenquist, H.; Bertolo, L.; et al. Campylobacter Vaccination of Poultry : Clinical Trials , Quantitative Microbiological Methods and Decision Support Tools for the Control of Campylobacter in Poultry. Int J Food Microbiol 2015, 9.

- Poudel, S.; Li, T.; Chen, S.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, W.-H.; Sukumaran, A.T.; Kiess, A.S.; Zhang, L. Prevalence, Antimicrobial Resistance, and Molecular Characterization of Campylobacter Isolated from Broilers and Broiler Meat Raised without Antibiotics. Microbiol Spectr 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Hack, M.E.; El-Saadony, M.T.; Salem, H.M.; El-Tahan, A.M.; Soliman, M.M.; Youssef, G.B.A.; Taha, A.E.; Soliman, S.M.; Ahmed, A.E.; El-kott, A.F.; et al. Alternatives to Antibiotics for Organic Poultry Production: Types, Modes of Action and Impacts on Bird’s Health and Production. Poult Sci 2022, 101. [Google Scholar]

- Slader, J.; Domingue, G.; Jørgensen, F.; McAlpine, K.; Owen, R.J.; Bolton, F.J.; Humphrey, T.J. Impact of Transport Crate Reuse and of Catching and Processing on Campylobacter and Salmonella Contamination of Broiler Chickens. Appl Environ Microbiol 2002, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, S.A.; Allen, V.M.; Domingue, G.; Jørgensen, F.; Frost, J.A.; Ure, R.; Whyte, R.; Tinker, D.; Corry, J.E.L.; Gillard-King, J.; et al. Sources of Campylobacter Spp. Colonizing Housed Broiler Flocks during Rearing. Appl Environ Microbiol 2006, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagenaar, J.A.; French, N.P.; Havelaar, A.H. Preventing Campylobacter at the Source: Why Is It so Difficult? Clinical Infectious Diseases 2013, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakeem, M.J.; Lu, X. Survival and Control of Campylobacter in Poultry Production Environment. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2021, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Nauta, M.; Johannessen, G.; Laureano Adame, L.; Williams, N.; Rosenquist, H. The Effect of Reducing Numbers of Campylobacter in Broiler Intestines on Human Health Risk. Microb Risk Anal 2016, 2–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenquist, H.; Nielsen, N.L.; Sommer, H.M.; Nørrung, B.; Christensen, B.B. Quantitative Risk Assessment of Human Campylobacteriosis Associated with Thermophilic Campylobacter Species in Chickens. Int J Food Microbiol 2003, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scientific Opinion on Campylobacter in Broiler Meat Production: Control Options and Performance Objectives and/or Targets at Different Stages of the Food Chain. EFSA Journal 2011, 9. [CrossRef]

- Soro, A.B.; Whyte, P.; Bolton, D.J.; Tiwari, B.K. Strategies and Novel Technologies to Control Campylobacter in the Poultry Chain: A Review. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 2020, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, R.Z.; Alsayeqh, A.F.; Aqib, A.I. Role of Bacteriophages for Optimized Health and Production of Poultry. Animals 2022, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Newell, D.G.; Elvers, K.T.; Dopfer, D.; Hansson, I.; Jones, P.; James, S.; Gittins, J.; Stern, N.J.; Davies, R.; Connerton, I.; et al. Biosecurity-Based Interventions and Strategies to Reduce Campylobacter Spp. on Poultry Farms. Appl Environ Microbiol 2011, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J. Novel Approaches for Campylobacter Control in Poultry. Foodborne Pathog Dis 2009, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Solow, B.T.; Cloak, O.M.; Fratamico, P.M. Effect of Temperature on Viability of Campylobacter Jejuni and Campylobacter Coli on Raw Chicken or Pork Skin. J Food Prot 2003, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soro, A.B.; Whyte, P.; Bolton, D.J.; Tiwari, B.K. Modelling the Effect of UV Light at Different Wavelengths and Treatment Combinations on the Inactivation of Campylobacter Jejuni. Innovative Food Science and Emerging Technologies 2021, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagle, B.R.; Donoghue, A.M.; Jesudhasan, P.R. Select Phytochemicals Reduce Campylobacter Jejuni in Postharvest Poultry and Modulate the Virulence Attributes of C. Jejuni. Front Microbiol 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wideman, N.; Bailey, M.; Bilgili, S.F.; Thippareddi, H.; Wang, L.; Bratcher, C.; Sanchez-Plata, M.; Singh, M. Evaluating Best Practices for Campylobacter and Salmonella Reduction in Poultry Processing Plants. Poult Sci 2016, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakarienė, G.; Novoslavskij, A.; Meškinis, Š.; Vasiliauskas, A.; Tamulevičienė, A.; Tamulevičius, S.; Alter, T.; Malakauskas, M. Diamond like Carbon Ag Nanocomposites as a Control Measure against Campylobacter Jejuni and Listeria Monocytogenes on Food Preparation Surfaces. Diam Relat Mater 2018, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Ezeike, G.O.I.; Doyle, M.P.; Hung, Y.C.; Howell, R.S. Reduction of Campylobacter Jejuni on Poultry by Low-Temperature Treatment. J Food Prot 2003, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-S.; Kim, T.-Y.; Lim, M.-C.; Khan, M.S.I. Campylobacter Control Strategies at Postharvest Level. Food Sci Biotechnol 2024, 33, 2919–2936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaakoush, N.O.; Castaño-Rodríguez, N.; Mitchell, H.M.; Man, S.M. Global Epidemiology of Campylobacter Infection. Clin Microbiol Rev 2015, 28, 687–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facciolà, A.; Riso, R.; Avventuroso, E.; Visalli, G.; Delia, S.A.; Laganà, P. Campylobacter: From Microbiology to Prevention. J Prev Med Hyg 2017, 58. [Google Scholar]

- Hermans, D.; Van Deun, K.; Martel, A.; Van Immerseel, F.; Messens, W.; Heyndrickx, M.; Haesebrouck, F.; Pasmans, F. Colonization Factors of Campylobacter Jejuni in the Chicken Gut. Vet Res 2011, 42. [Google Scholar]

- Batz, M.B.; Hoffmann, S.; Morris, J.G. Ranking the Disease Burden of 14 Pathogens in Food Sources in the United States Using Attribution Data from Outbreak Investigations and Expert Elicitation. J Food Prot 2012, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronese, P.; Dodi, I. Campylobacter Jejuni/Coli Infection: Is It Still a Concern? Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- dessouky, Y. El; Elsayed, S.W.; Abdelsalam, N.A.; Saif, N.A.; Álvarez-Ordóñez, A.; Elhadidy, M. Genomic Insights into Zoonotic Transmission and Antimicrobial Resistance in Campylobacter Jejuni from Farm to Fork: A One Health Perspective. Gut Pathog 2022, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Korsak, D.; Maćkiw, E.; Rozynek, E.; Zyłowska, M. Prevalence of Campylobacter Spp. in Retail Chicken, Turkey, Pork, and Beef Meat in Poland between 2009 and 2013. J Food Prot 2015, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasschaert, G.; De Zutter, L.; Herman, L.; Heyndrickx, M. Campylobacter Contamination of Broilers: The Role of Transport and Slaughterhouse. Int J Food Microbiol 2020, 322. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, D.A. Infective Dose of Campylobacter Jejuni in Milk. Br Med J 1981, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, R.E.; Levine, M.M.; Clements, M. Lou; Hughes, T.P.; Blaser, M.J.; Black, R.E. Experimental Campylobacter Jejuni Infection in Humans. Journal of Infectious Diseases 1988, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cawthraw, S.A.; Wassenaar, T.M.; Ayling, R.; Newell, D.G. Increased Colonization Potential of Campylobacter Jejuni Strain 81116 after Passage through Chickens and Its Implication on the Rate of Transmission within Flocks. Epidemiol Infect 1996, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassenaar, T.M.; Van der Zeijst, B.A.M.; Ayling, R.; Newell, D.G. Colonization of Chicks by Motility Mutants of Campylobacter Jejuni Demonstrates the Importance of Flagellin A Expression. J Gen Microbiol 1993, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, D.G.; Fearnley, C. Sources of Campylobacter Colonization in Broiler Chickens. Appl Environ Microbiol 2003, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha-Abdelaziz, K.; Singh, M.; Sharif, S.; Sharma, S.; Kulkarni, R.R.; Alizadeh, M.; Yitbarek, A.; Helmy, Y.A. Intervention Strategies to Control Campylobacter at Different Stages of the Food Chain. Microorganisms 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadek, S.A.S.; Shaapan, R.M.; Barakat, A.M.A. Campylobacteriosis in Poultry: A Review. J Worlds Poult Res 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, M.I.; Malkawi, I.; Walker, M.; Alaboudi, A.; Abu-Basha, E.; Blake, D.P.; Guitian, J.; Crotta, M. The Transmission Dynamics of Campylobacter Jejuni among Broilers in Semi-Commercial Farms in Jordan. Epidemiol Infect 2019, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawson, T.; Dawkins, M.S.; Bonsall, M.B. A Mathematical Model of Campylobacter Dynamics within a Broiler Flock. Front Microbiol 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Yin, T.; Du, X.; Yang, W.; Huang, J.; Jiao, X. Occurrence and Genotypes of Campylobacter Species in Broilers during the Rearing Period. Avian Pathology 2017, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO/WHO Risk Assessment of Campylobacter Spp in Broiler Chickens: Technical Report; 2009; Vol. 180;

- Rosenquist, H.; Boysen, L.; Galliano, C.; Nordentoft, S.; Ethelberg, S.; Borck, B. Danish Strategies to Control Campylobacter in Broilers and Broiler Meat: Facts and Effects. Epidemiol Infect 2009, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, N.J.; Hiett, K.L.; Alfredsson, G.A.; Kristinsson, K.G.; Reiersen, J.; Hardardottir, H.; Briem, H.; Gunnarsson, E.; Georgsson, F.; Lowman, R.; et al. Campylobacter Spp. in Icelandic Poultry Operations and Human Disease. Epidemiol Infect 2003, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The European Union Summary Report on Antimicrobial Resistance in Zoonotic and Indicator Bacteria from Humans, Animals and Food in 2022–2023. EFSA Journal 2025, 23. [CrossRef]

- Olvera-Ramírez, A.M.; McEwan, N.R.; Stanley, K.; Nava-Diaz, R.; Aguilar-Tipacamú, G. A Systematic Review on the Role of Wildlife as Carriers and Spreaders of Campylobacter Spp. Animals 2023, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Vaddu, S.; Bhumanapalli, S.; Mishra, A.; Applegate, T.; Singh, M.; Thippareddi, H. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Sources of Campylobacter in Poultry Production (Preharvest) and Their Relative Contributions to the Microbial Risk of Poultry Meat. Poult Sci 2023, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, E.; Barnhart, H.; Dreesen, D.W.; Stern, N.J.; Corn, J.L. Epidemiological Study of Campylobacter Spp. in Broilers: Source, Time of Colonization, and Prevalence. Avian Dis 1997, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hald, B.; Skovgård, H.; Bang, D.D.; Pedersen, K.; Dybdahl, J.; Jespersen, J.B.; Madsen, M. Flies and Campylobacter Infection of Broiler Flocks. Emerg Infect Dis 2004, 10, 1490–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, D.G. The Ecology of Campylobacter Jejuni in Avian and Human Hosts and in the Environment. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2002, 6, S16–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FSIS Compliance Guideline for Controlling Salmonella and Campylobacter in Poultry. Third Edition 2010.

- Royden, A.; Christley, R.; Prendiville, A.; Williams, N.J. The Role of Biosecurity in the Control of Campylobacter: A Qualitative Study of the Attitudes and Perceptions of UK Broiler Farm Workers. Front Vet Sci 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiev, M.; Beauvais, W.; Guitian, J. Effect of Enhanced Biosecurity and Selected On-Farm Factors on Campylobacter Colonization of Chicken Broilers. Epidemiol Infect 2017, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The European Union Summary Report on Antimicrobial Resistance in Zoonotic and Indicator Bacteria from Humans, Animals and Food in 2021–2022. EFSA Journal 2024, 22. [CrossRef]

- Santos, L.S.; Rossi, D.A.; Braz, R.F.; Fonseca, B.B.; Guidotti–Takeuchi, M.; Alves, R.N.; Beletti, M.E.; Almeida-Souza, H.O.; Maia, L.P.; Santos, P. de S.; et al. Roles of Viable but Non-Culturable State in the Survival of Campylobacter Jejuni. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Chaisowwong, W.; Kusumoto, A.; Hashimoto, M.; Harada, T.; Maklon, K.; Kawamoto, K. Physiological Characterization of Campylobacter Jejuni under Cold Stresses Conditions: Its Potential for Public Threat. Journal of Veterinary Medical Science 2012, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemelka, K.W.; Brown, A.W.; Wallace, S.M.; Jones, E.; Asher, L. V.; Pattarini, D.; Applebee, L.; Gilliland, T.C.; Guerry, P.; Baqar, S. Immune Response to and Histopathology of Campylobacter Jejuni Infection in Ferrets (Mustela Putorius Furo). Comp Med 2009, 59. [Google Scholar]

- Marks, S.L.; Rankin, S.C.; Byrne, B.A.; Weese, J.S. Enteropathogenic Bacteria in Dogs and Cats: Diagnosis, Epidemiology, Treatment, and Control. J Vet Intern Med 2011, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macartney, L.; Al-Mashat, R.R.; Taylor, D.J.; McCandlish, I.A. Experimental Infection of Dogs with Campylobacter Jejuni. Vet Rec 1988, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemmons, E.A.; Jean, S.M.; Machiah, D.K.; Breding, E.; Sharma, P. Extraintestinal Campylobacteriosis in Rhesus Macaques (Macaca Mulatta). Comp Med 2014, 64. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, Y.K.; Oh, J.Y.; Jeong, O.M.; Moon, O.K.; Kang, M.S.; Jung, B.Y.; An, B.K.; Youn, S.Y.; Kim, H.R.; Jang, I.; et al. Prevalence of Campylobacter Species in Wild Birds of South Korea. Avian Pathology 2017, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wysok, B.; Sołtysiuk, M.; Stenzel, T. Wildlife Waterfowl as a Source of Pathogenic Campylobacter Strains. Pathogens 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, C.; Bahrndorff, S.; Lowenberger, C. Campylobacter Jejuni in Musca Domestica: An Examination of Survival and Transmission Potential in Light of the Innate Immune Responses of the House Flies. Insect Sci 2017, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hald, B.; Skovgård, H.; Pedersen, K.; Bunkenborg, H. Influxed Insects as Vectors for Campylobacter Jejuni and Campylobacter Coli in Danish Broiler Houses. Poult Sci 2008, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Guk, J.H.; Mun, S.H.; An, J.U.; Kim, W.; Lee, S.; Song, H.; Seong, J.K.; Suh, J.G.; Cho, S. The Wild Mouse (Micromys Minutus): Reservoir of a Novel Campylobacter Jejuni Strain. Front Microbiol 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olkkola, S.; Rossi, M.; Jaakkonen, A.; Simola, M.; Tikkanen, J.; Hakkinen, M.; Tuominen, P.; Huitu, O.; Niemimaa, J.; Henttonen, H.; et al. Host-Dependent Clustering of Campylobacter Strains From Small Mammals in Finland. Front Microbiol 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerburg, B.G.; Jacobs-Reitsma, W.F.; Wagenaar, J.A.; Kijlstra, A. Presence of Salmonella and Campylobacter Spp. in Wild Small Mammals on Organic Farms. Appl Environ Microbiol 2006, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- on Biological Hazards (BIOHAZ), E.P. Scientific Opinion on Campylobacter in Broiler Meat Production: Control Options and Performance Objectives and/or Targets at Different Stages of the Food Chain. EFSA Journal 2011, 9, 2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansson, I.; Ederoth, M.; Andersson, L.; Vågsholm, I.; Engvall, E.O. Transmission of Campylobacter Spp. to Chickens during Transport to Slaughter. J Appl Microbiol 2005, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindels, L.B.; Delzenne, N.M.; Cani, P.D.; Walter, J. Opinion: Towards a More Comprehensive Concept for Prebiotics. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015, 12. [Google Scholar]

- FAO/WHO Health and Nutritional Properties of Probiotics in Food Including Powder Milk with Liver Lactic Acid Bacteria. Food and Agriculture Organization and World Health Organization Joint Report. Prevention 2001, 5.

- Verschuere, L.; Rombaut, G.; Sorgeloos, P.; Verstraete, W. Probiotic Bacteria as Biological Control Agents in Aquaculture. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 2000, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouwehand, A.C.; Salminen, S.; Isolauri, E. Probiotics: An Overview of Beneficial Effects. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, International Journal of General and Molecular Microbiology 2002, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, G.R.; Roberfroid, M.B. Dietary Modulation of the Human Colonic Microbiota: Introducing the Concept of Prebiotics. Journal of Nutrition 1995, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, L.; Bermudez-Brito, M.; Plaza-Diaz, J.; Muñoz-Quezada, S.; Gil, A. Sources, Isolation, Characterisation and Evaluation of Probiotics. British Journal of Nutrition 2013, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermudez-Brito, M.; Plaza-Díaz, J.; Muñoz-Quezada, S.; Gómez-Llorente, C.; Gil, A. Probiotic Mechanisms of Action. Ann Nutr Metab 2012, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhari, A.A.; Lee, Y.; Lillehoj, H.S. Beneficial Effects of Dietary Supplementation of Bacillus Strains on Growth Performance and Gut Health in Chickens with Mixed Coccidiosis Infection. Vet Parasitol 2020, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, F.; Muccee, F.; Shahab, A.; Safi, S.Z.; Alomar, S.Y.; Qadeer, A. Isolation and in Vitro Assessment of Chicken Gut Microbes for Probiotic Potential. Front Microbiol 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Long, S.; Mahfuz, S.; Wu, D.; Wang, X.; Wei, X.; Piao, X. Effects of Probiotics as Antibiotics Substitutes on Growth Performance, Serum Biochemical Parameters, Intestinal Morphology, and Barrier Function of Broilers. Animals 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.; Junaid, N.; Kumawat, M.; Qureshi, S.; Mandal, A.B. Influence of Dietary Supplementation of Probiotics on Intestinal Histo-Morphometry, Blood Chemistry and Gut Health Status of Broiler Chickens. S Afr J Anim Sci 2019, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruwa, C.E.; Pillay, C.; Nyaga, M.M.; Sabiu, S. Poultry Gut Health – Microbiome Functions, Environmental Impacts, Microbiome Engineering and Advancements in Characterization Technologies. J Anim Sci Biotechnol 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedford, M.R.; Apajalahti, J.H. The Role of Feed Enzymes in Maintaining Poultry Intestinal Health. J Sci Food Agric 2022, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabetafika, H.N.; Razafindralambo, A.; Ebenso, B.; Razafindralambo, H.L. Probiotics as Antibiotic Alternatives for Human and Animal Applications. Encyclopedia 2023, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varastegani, A.; Dahlan, I. Influence of Dietary Fiber Levels on Feed Utilization and Growth Performance in Poultry. J. Anim. Pro. Adv. 2014, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, Y.; Kumar, S.; Oakley, B.; Kim, W.K. Chicken Gut Microbiota: Importance and Detection Technology. Front Vet Sci 2018, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clavijo, V.; Flórez, M.J.V. The Gastrointestinal Microbiome and Its Association with the Control of Pathogens in Broiler Chicken Production: A Review. Poult Sci 2018, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, J.M.D.; Casanova, N.A.; Miyakawa, M.E.F. Microbiota, Gut Health and Chicken Productivity: What Is the Connection? Microorganisms 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torok, V.A.; Hughes, R.J.; Mikkelsen, L.L.; Perez-Maldonado, R.; Balding, K.; MacAlpine, R.; Percy, N.J.; Ophel-Keller, K. Identification and Characterization of Potential Performance-Related Gut Microbiotas in Broiler Chickens across Various Feeding Trials. Appl Environ Microbiol 2011, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idowu, P.A.; Mpofu, T.J.; Magoro, A.M.; Modiba, M.C.; Nephawe, K.A.; Mtileni, B. Impact of Probiotics on Chicken Gut Microbiota, Immunity, Behavior, and Productive Performance—a Systematic Review. Frontiers in Animal Science 2025, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourabedin, M.; Zhao, X. Prebiotics and Gut Microbiota in Chickens. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2015, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, T.; Lu, Y.; Ding, W.; Xu, B.; Zhang, C.; Li, L.; Jian, F.; Huang, S. The Role of Probiotics, Prebiotics, Synbiotics, and Postbiotics in Livestock and Poultry Gut Health: A Review. Metabolites 2025, 15, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M.; Bourassa, D. Probiotics in Poultry: Unlocking Productivity Through Microbiome Modulation and Gut Health. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, R.; Das, R.; Oak, S.; Mishra, P. Probiotics (Direct-fed Microbials) in Poultry Nutrition and Their Effects on Nutrient Utilization, Growth and Laying Performance, and Gut Health: A Systematic Review. Animals 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaggìa, F.; Mattarelli, P.; Biavati, B. Probiotics and Prebiotics in Animal Feeding for Safe Food Production. Int J Food Microbiol 2010, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, T.; Lu, Y.; Ding, W.; Xu, B.; Zhang, C.; Li, L.; Jian, F.; Huang, S. The Role of Probiotics, Prebiotics, Synbiotics, and Postbiotics in Livestock and Poultry Gut Health: A Review. Metabolites 2025, 15, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsilingiri, K.; Rescigno, M. Postbiotics: What Else? Benef Microbes 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcial-Coba, M.S.; Pjaca, A.S.; Andersen, C.J.; Knøchel, S.; Nielsen, D.S. Dried Date Paste as Carrier of the Proposed Probiotic Bacillus Coagulans BC4 and Viability Assessment during Storage and Simulated Gastric Passage. LWT 2019, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salminen, S.; Collado, M.C.; Endo, A.; Hill, C.; Lebeer, S.; Quigley, E.M.M.; Sanders, M.E.; Shamir, R.; Swann, J.R.; Szajewska, H.; et al. The International Scientific Association of Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) Consensus Statement on the Definition and Scope of Postbiotics. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Burcelin, R.; Serino, M.; Chabo, C.; Blasco-Baque, V.; Amar, J. Gut Microbiota and Diabetes: From Pathogenesis to Therapeutic Perspective. Acta Diabetol 2011, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thu, T. V.; Loh, T.C.; Foo, H.L.; Yaakub, H.; Bejo, M.H. Effects of Liquid Metabolite Combinations Produced by Lactobacillus Plantarum on Growth Performance, Faeces Characteristics, Intestinal Morphology and Diarrhoea Incidence in Postweaning Piglets. Trop Anim Health Prod 2011, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Guo, Q.; Wang, J.; Tan, H.; Jin, X.; Fan, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhao, S.; Zheng, J.; Peng, N. Postbiotics from Pichia Kudriavzevii Promote Intestinal Health Performance through Regulation of Limosilactobacillus Reuteri in Weaned Piglets. Food Funct 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachi, S.; Kanmani, P.; Tomosada, Y.; Kobayashi, H.; Yuri, T.; Egusa, S.; Shimazu, T.; Suda, Y.; Aso, H.; Sugawara, M.; et al. Lactobacillus Delbrueckii TUA4408L and Its Extracellular Polysaccharides Attenuate Enterotoxigenic Escherichia Coli-Induced Inflammatory Response in Porcine Intestinal Epitheliocytes via Toll-like Receptor-2 and 4. Mol Nutr Food Res 2014, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.; Sawant, S.; Hauff, K.; Hampp, G. Validated Postbiotic Screening Confirms Presence of Physiologically-Active Metabolites, Such as Short-Chain Fatty Acids, Amino Acids and Vitamins in Hylak® Forte. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodridge, L.D.; Bisha, B. Phage-Based Biocontrol Strategies to Reduce Foodborne Pathogens in Foods. Bacteriophage 2011, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenquist, H.; Boysen, L.; Krogh, A.L.; Jensen, A.N.; Nauta, M. Campylobacter Contamination and the Relative Risk of Illness from Organic Broiler Meat in Comparison with Conventional Broiler Meat. Int J Food Microbiol 2013, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinivasagam, H.N.; Estella, W.; Maddock, L.; Mayer, D.G.; Weyand, C.; Connerton, P.L.; Connerton, I.F. Bacteriophages to Control Campylobacter in Commercially Farmed Broiler Chickens, in Australia. Front Microbiol 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, P.J.; Connerton, P.L.; Connerton, I.F. Phage Biocontrol of Campylobacter Jejuni in Chickens Does Not Produce Collateral Effects on the Gut Microbiota. Front Microbiol 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waghmare, S.; Gupta, M.; Bahiram, K.B.; Korde, J.P.; Bhat, R.; Datar, Y.; Rajora, P.; Kadam, M.M.; Kaore, M.; Kurkure, N.V. Effects of Organic Acid Blends on the Growth Performance, Intestinal Morphology, Microbiota, and Serum Lipid Parameters of Broiler Chickens. Poult Sci 2025, 104, 104546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Xin, H.; Yang, C.; Yang, X. Impact of Essential Oils and Organic Acids on the Growth Performance, Digestive Functions and Immunity of Broiler Chickens. Animal Nutrition 2018, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, R.U.; Naz, S.; Raziq, F.; Qudratullah, Q.; Khan, N.A.; Laudadio, V.; Tufarelli, V.; Ragni, M. Prospects of Organic Acids as Safe Alternative to Antibiotics in Broiler Chickens Diet. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2022, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani-López, E.; García, H.S.; López-Malo, A. Organic Acids as Antimicrobials to Control Salmonella in Meat and Poultry Products. Food Research International 2012, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibner, J.J.; Buttin, P. Use of Organic Acids as a Model to Study the Impact of Gut Microflora on Nutrition and Metabolism. Journal of Applied Poultry Research 2002, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movahedi, F.; Nirmal, N.; Wang, P.; Jin, H.; Grøndahl, L.; Li, L. Recent Advances in Essential Oils and Their Nanoformulations for Poultry Feed. J Anim Sci Biotechnol 2024, 15, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusdi, R.; Hasanuddin, A.; Arief, R. Evaluation of Eleutherine (Eleutherine Americana) Potential As Feed Additive for Poultry. Jurnal Agrisains 2016, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Kamatou, G.P.P.; Viljoen, A.M. A Review of the Application and Pharmacological Properties of α-Bisabolol and α-Bisabolol-Rich Oils. JAOCS, Journal of the American Oil Chemists’ Society 2010, 87.

- Miguel, M.G. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activities of Essential Oils: A Short Review. Molecules 2010, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, M.; Stanley, R.; Cusack, A.; Yasmina, S. Combinations of Plant-Derived Compounds AgainstCampylobacter in Vitro. Journal of Applied Poultry Research 2015, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sar, T.; Akbas, M.Y. Antimicrobial Activities of Olive Oil Mill Wastewater Extracts against Selected Microorganisms. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, S.R.; Davoodi, H. Herbal Plants and Their Derivatives as Growth and Health Promoters in Animal Nutrition. Vet Res Commun 2011, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannenas, I.; Bonos, E.; Filliousis, G.; Stylianaki, I.; Kumar, P.; Lazari, D.; Christaki, E.; Florou-Paneri, P. Effect of a Polyherbal or an Arsenic-Containing Feed Additive on Growth Performance of Broiler Chickens, Intestinal Microbiota, Intestinal Morphology, and Lipid Oxidation of Breast and Thigh Meat. Journal of Applied Poultry Research 2019, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, S. Essential Oils: Their Antibacterial Properties and Potential Applications in Foods - A Review. Int J Food Microbiol 2004, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windisch, W.; Schedle, K.; Plitzner, C.; Kroismayr, A. Use of Phytogenic Products as Feed Additives for Swine and Poultry. J Anim Sci 2008, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwata, T.; Watanabe-Yanai, A.; Tamamura-Andoh, Y.; Arai, N.; Akiba, M.; Kusumoto, M. Tryptanthrin Reduces Campylobacter Jejuni Colonization in the Chicken Gut by a Bactericidal Mechanism. Appl Environ Microbiol 2023, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World health organization WHO | WHO Department on Immunization, Vaccines and Biologicals. Who 2017.

- Igwaran, A.; Okoh, A.I. Molecular Determination of Genetic Diversity among Campylobacter Jejuni and Campylobacter Coli Isolated from Milk, Water, and Meat Samples Using Enterobacterial Repetitive Intergenic Consensus PCR (ERIC-PCR). Infect Ecol Epidemiol 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, B.; Saisom, T.; Sasipreeyajan, J.; Luangtongkum, T. Live-Attenuated Oral Vaccines to Reduce Campylobacter Colonization in Poultry. Vaccines (Basel) 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelo Taboada, A.C.; Pavic, A. Vaccinating Meat Chickens against Campylobacter and Salmonella: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Vaccines (Basel) 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermans, D.; Van Deun, K.; Messens, W.; Martel, A.; Van Immerseel, F.; Haesebrouck, F.; Rasschaert, G.; Heyndrickx, M.; Pasmans, F. Campylobacter Control in Poultry by Current Intervention Measures Ineffective: Urgent Need for Intensified Fundamental Research. Vet Microbiol 2011, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, L.J.; Zeng, X.; Lin, J. Development and Evaluation of Two Live Salmonella-Vectored Vaccines for Campylobacter Control in Broiler Chickens. Foodborne Pathog Dis 2019, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meunier, M.; Guyard-Nicodème, M.; Dory, D.; Chemaly, M. Control Strategies against Campylobacter at the Poultry Production Level: Biosecurity Measures, Feed Additives and Vaccination. J Appl Microbiol 2016, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhou, H.; Guo, F.; Yang, B.; Su, X.; Lin, J.; Xu, F. Oral Immunization of Chickens with Lactococcus Lactis Expressing CjaA Temporarily Reduces Campylobacter Jejuni Colonization. Foodborne Pathog Dis 2020, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal-McKinney, J.M.; Samuelson, D.R.; Eucker, T.P.; Nissen, M.S.; Crespo, R.; Konkel, M.E. Reducing Campylobacter Jejuni Colonization of Poultry via Vaccination. PLoS One 2014, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyszyńska, A.; Raczko, A.; Lis, M.; Jagusztyn-Krynicka, E.K. Oral Immunization of Chickens with Avirulent Salmonella Vaccine Strain Carrying C. Jejuni 72Dz/92 CjaA Gene Elicits Specific Humoral Immune Response Associated with Protection against Challenge with Wild-Type Campylobacter. Vaccine 2004, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, F.A.; Cortines, J. dos R.; Essus, V.A.; da Silva, I.B.N. Vaccine Engineering & Structural Vaccinology. In System Vaccinology: The History, the Translational Challenges and the Future; 2022.

- Nothaft, H.; Perez-Muñoz, M.E.; Gouveia, G.J.; Duar, R.M.; Wanford, J.J.; Lango-Scholey, L.; Panagos, C.G.; Srithayakumar, V.; Plastow, G.S.; Coros, C.; et al. Coadministration of the Campylobacter Jejuni N-Glycan-Based Vaccine with Probiotics Improves Vaccine Performance in Broiler Chickens. Appl Environ Microbiol 2017, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pumtang-On, P.; Mahony, T.J.; Hill, R.A.; Vanniasinkam, T. A Systematic Review of Campylobacter Jejuni Vaccine Candidates for Chickens. Microorganisms 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Head, J.R.; Vos, A.; Blanton, J.; Müller, T.; Chipman, R.; Pieracci, E.G.; Cleaton, J.; Wallace, R. Environmental Distribution of Certain Modified Live-Virus Vaccines with a High Safety Profile Presents a Low-Risk, High-Reward to Control Zoonotic Diseases. Sci Rep 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, J.P. Principles of Immunization. In Travel Medicine; 2018.

- Naguib, M.; Sharma, S.; Schneider, A.; Wehmueller, S.; Abdelaziz, K. Comparative Effectiveness of Various Multi-Antigen Vaccines in Controlling Campylobacter Jejuni in Broiler Chickens. Vaccines (Basel) 2024, 12, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamura, M.; Tominaga, A.; Ueda, M.; Ohshima, R.; Kobayashi, M.; Tsukada, M.; Yokoyama, E.; Takehara, K.; Deguchi, K.; Honda, T.; et al. Irrelevance between the Induction of Anti-Campylobacter Humoral Response by a Bacterin and the Lack of Protection against Homologous Challenge in Japanese Jidori Chickens. Journal of Veterinary Medical Science 2012, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konkel, M.E.; Joens, L.A. Adhesion to and Invasion of HEp-2 Cells by Campylobacter Spp. Infect Immun 1989, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burakova, Y.; Madera, R.; McVey, S.; Schlup, J.R.; Shi, J. Adjuvants for Animal Vaccines. Viral Immunol 2018, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravikumar, R.; Chan, J.; Prabakaran, M. Vaccines against Major Poultry Viral Diseases: Strategies to Improve the Breadth and Protective Efficacy. Viruses 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodman-Harris, O.; Rollier, C.S.; Iqbal, M. Approaches to Enhance the Potency of Vaccines in Chickens. Vaccines (Basel) 2024, 12, 1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whalen, R.G. DNA Vaccines, Cyberspace and Self-Help Programs. Intervirology 1996, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mor, G. Plasmid DNA: A New Era in Vaccinology. Biochem Pharmacol 1998, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leitner, W.W.; Ying, H.; Restifo, N.P. DNA and RNA-Based Vaccines: Principles, Progress and Prospects. Vaccine 1999, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Yuan, F. A Comprehensive Comparison of DNA and RNA Vaccines. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2024, 210, 115340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Adams, L.J.; Zeng, X.; Lin, J. Evaluation of in Ovo Vaccination of DNA Vaccines for Campylobacter Control in Broiler Chickens. Vaccine 2019, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gloanec, N.; Guyard-Nicodème, M.; Brunetti, R.; Quesne, S.; Keita, A.; Chemaly, M.; Dory, D. Plasmid DNA Prime/Protein Boost Vaccination against Campylobacter Jejuni in Broilers: Impact of Vaccine Candidates on Immune Responses and Gut Microbiota. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meunier, M.; Guyard-Nicodème, M.; Vigouroux, E.; Poezevara, T.; Béven, V.; Quesne, S.; Amelot, M.; Parra, A.; Chemaly, M.; Dory, D. A DNA Prime/Protein Boost Vaccine Protocol Developed against Campylobacter Jejuni for Poultry. Vaccine 2018, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gote, V.; Bolla, P.K.; Kommineni, N.; Butreddy, A.; Nukala, P.K.; Palakurthi, S.S.; Khan, W. A Comprehensive Review of MRNA Vaccines. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capozzo, A.V.E.; Ramírez, K.; Polo, J.M.; Ulmer, J.; Barry, E.M.; Levine, M.M.; Pasetti, M.F. Neonatal Immunization with a Sindbis Virus-DNA Measles Vaccine Induces Adult-Like Neutralizing Antibodies and Cell-Mediated Immunity in the Presence of Maternal Antibodies. The Journal of Immunology 2006, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manickan, E.; Yu, Z.; Rouse, B.T. DNA Immunization of Neonates Induces Immunity despite the Presence of Maternal Antibody. Journal of Clinical Investigation 1997, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannotta, G.; Murrone, A.; Giannotta, N. COVID-19 MRNA Vaccines: The Molecular Basis of Some Adverse Events. Vaccines (Basel) 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, M.R.; Poland, G.A. Critical Aspects of Packaging, Storage, Preparation, and Administration of MRNA and Adenovirus-Vectored COVID-19 Vaccines for Optimal Efficacy. Vaccine 2021, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefébure, T.; Bitar, P.D.P.; Suzuki, H.; Stanhope, M.J. Evolutionary Dynamics of Complete Campylobacter Pan-Genomes and the Bacterial Species Concept. Genome Biol Evol 2010, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, D.; Lévesque, S.; Kumar, N.; Fresia, P.; Ferrés, I.; Lawley, T.D.; Iraola, G. Pangenome Analysis Reveals Genetic Isolation in Campylobacter Hyointestinalis Subspecies Adapted to Different Mammalian Hosts. Sci Rep 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemmell, M.R.; Berry, S.; Mukhopadhya, I.; Hansen, R.; Nielsen, H.L.; Bajaj-Elliott, M.; Nielsen, H.; Hold, G.L. Comparative Genomics of Campylobacter Concisus: Analysis of Clinical Strains Reveals Genome Diversity and Pathogenic Potential. Emerg Microbes Infect 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C.; Qu, B.; Hu, G.; Ning, K. Pan-Genome Analysis of Campylobacter: Insights on the Genomic Diversity and Virulence Profile. Microbiol Spectr 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cayrou, C.; Barratt, N.A.; Ketley, J.M.; Bayliss, C.D. Phase Variation During Host Colonization and Invasion by Campylobacter Jejuni and Other Campylobacter Species. Front Microbiol 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, K.L.; Atack, J.M.; Srikhanta, Y.N.; Eckert, A.; Novotny, L.A.; Bakaletz, L.O.; Jennings, M.P. Selection for Phase Variation of Los Biosynthetic Genes Frequently Occurs in Progression of Non-Typeable Haemophilus Influenzae Infection from the Nasopharynx to the Middle Ear of Human Patients. PLoS One 2014, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Woude, M.W.; Bäumler, A.J. Phase and Antigenic Variation in Bacteria. Clin Microbiol Rev 2004, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Woude, M.W. Re-Examining the Role and Random Nature of Phase Variation. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2006, 254. [Google Scholar]

- van der Woude, M.W. Phase Variation: How to Create and Coordinate Population Diversity. Curr Opin Microbiol 2011, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burnham, P.M.; Hendrixson, D.R. Campylobacter Jejuni: Collective Components Promoting a Successful Enteric Lifestyle. Nat Rev Microbiol 2018, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Marmion, M.; Ferone, M.; Wall, P.; Scannell, A.G.M. On Farm Interventions to Minimise Campylobacter Spp. Contamination in Chicken. Br Poult Sci 2021, 62. [Google Scholar]

- Sahin, O.; Luo, N.; Huang, S.; Zhang, Q. Effect of Campylobacter-Specific Maternal Antibodies on Campylobacter Jejuni Colonization in Young Chickens. Appl Environ Microbiol 2003, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shreeve, J.E.; Toszeghy, M.; Pattison, M.; Newell, D.G. Sequential Spread of Campylobacter Infection in a Multipen Broiler House. Avian Dis 2000, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs-Reitsma, W.F.; Van de Giessen, A.W.; Bolder, N.M.; Mulder, R.W.A.W. Epidemiology of Campylobacter Spp. at Two Dutch Broiler Farms. Epidemiol Infect 1995, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, S.J.; Sayers, A.R. A Longitudinal Study of Campylobacter Infection of Broiler Flocks in Great Britain. Prev Vet Med 2000, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haems, K.; Van Rysselberghe, N.; Goossens, E.; Strubbe, D.; Rasschaert, G.; Martel, A.; Pasmans, F.; Garmyn, A. Reducing Campylobacter Colonization in Broilers by Active Immunization of Naive Broiler Breeders Using a Bacterin and Subunit Vaccine. Poult Sci 2023, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haems, K.; Strubbe, D.; Van Rysselberghe, N.; Rasschaert, G.; Martel, A.; Pasmans, F.; Garmyn, A. Role of Maternal Antibodies in the Protection of Broiler Chicks against Campylobacter Colonization in the First Weeks of Life. Animals 2024, 14, 1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eliasson, E.; Sun, L.; Cervin, G.; Pavia, H.; Tällberg, G.; Ellström, P.; Ivarsson, E. No Colonization Resistance to Campylobacter Jejuni in Broilers Fed Brown Algal Extract-Supplemented Diets. Front Microbiol 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naguib, M.; Sharma, S.; Schneider, A.; Bragg, Ari.J.; Abdelaziz, K. A Multi-Antigen Campylobacter Vaccine Enhances Antibody Responses in Layer Breeders and Sustains Elevated Maternal Antibody Levels in Their Offspring. Poult Sci 2025, 104, 104898. [CrossRef]

- Lacharme-Lora, L.; Chaloner, G.; Gilroy, R.; Humphrey, S.; Gibbs, K.; Jopson, S.; Wright, E.; Reid, W.; Ketley, J.; Humphrey, T.; et al. B Lymphocytes Play a Limited Role in Clearance of Campylobacter Jejuni from the Chicken Intestinal Tract. Sci Rep 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chintoan-Uta, C.; Cassady-Cain, R.L.; Al-Haideri, H.; Watson, E.; Kelly, D.J.; Smith, D.G.E.; Sparks, N.H.C.; Kaiser, P.; Stevens, M.P. Superoxide Dismutase SodB Is a Protective Antigen against Campylobacter Jejuni Colonisation in Chickens. Vaccine 2015, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrow, P.A.; Huggins, M.B.; Lovell, M.A.; Simpson, J.M. Observations on the Pathogenesis of Experimental Salmonella Typhimurium Infection in Chickens. Res Vet Sci 1987, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layton, S.L.; Morgan, M.J.; Cole, K.; Kwon, Y.M.; Donoghue, D.J.; Hargis, B.M.; Pumford, N.R. Evaluation of Salmonella-Vectored Campylobacter Peptide Epitopes for Reduction of Campylobacter Jejuni in Broiler Chickens. Clinical and Vaccine Immunology 2011, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, A.M.; Wang, J.; Hudson, D.L.; Grant, A.J.; Jones, M.A.; Maskell, D.J.; Stevens, M.P. Evaluation of Live-Attenuated Salmonella Vaccines Expressing Campylobacter Antigens for Control of C. Jejuni in Poultry. Vaccine 2010, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilroy, R.; Wedley, A.; Jopson, S.; Hall, J.; Wigley, P. The Immunobiology of Persistent Intestinal Infection by Campylobacter Jejuni in the Chicken 2024.

- Kobierecka, P.A.; Wyszynska, A.K.; Gubernator, J.; Kuczkowski, M.; Wisniewski, O.; Maruszewska, M.; Wojtania, A.; Derlatka, K.E.; Adamska, I.; Godlewska, R.; et al. Chicken Anti-Campylobacter Vaccine - Comparison of Various Carriers and Routes of Immunization. Front Microbiol 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccopieri, C.; Madej, J.P. Chicken Secondary Lymphoid Tissues—Structure and Relevance in Immunological Research. Animals 2024, 14, 2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Kaiser, P. Antigen Presenting Cells in a Non-Mammalian Model System, the Chicken. Immunobiology 2011, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Matos, R.; Morrisey, J.K. Marek’s Disease. In Comparative Veterinary Anatomy; Elsevier, 2022; pp. 1355–1363.

- Muir, W.I.; Bryden, W.L.; Husband, A.J. Immunity, Vaccination and the Avian Intestinal Tract. Dev Comp Immunol 2000, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nochi, T.; Jansen, C.A.; Toyomizu, M.; Eden, W. van The Well-Developed Mucosal Immune Systems of Birds and Mammals Allow for Similar Approaches of Mucosal Vaccination in Both Types of Animals. Front Nutr 2018, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Guérin, J.L.; Balloy, D.; Pinson, M.; Jbenyeni, A.; Delpont, M. Vaccination Technology in Poultry: Principles of Vaccine Administration. Avian Dis 2023, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calland, J.K.; Pesonen, M.E.; Mehat, J.; Pascoe, B.; Haydon, D.J.; Lourenco, J.; Lukasiewicz, B.; Mourkas, E.; Hitchings, M.D.; La Ragione, R.M.; et al. Genomic Tailoring of Autogenous Poultry Vaccines to Reduce Campylobacter from Farm to Fork. NPJ Vaccines 2024, 9, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Annamalai, T.; Pina-Mimbela, R.; Kumar, A.; Binjawadagi, B.; Liu, Z.; Renukaradhya, G.J.; Rajashekara, G. Evaluation of Nanoparticle-Encapsulated Outer Membrane Proteins for the Control of Campylobacter Jejuni Colonization in Chickens. Poult Sci 2013, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, X.A.; Huang, J.L.; Yin, Y.X.; Pan, Z.M.; Zhang, G.; Zhu, A.P.; Liu, X.F. Intranasal Immunization with Chitosan/PCAGGS-Fla A Nanoparticles Inhibits Campylobacter Jejuni in a White Leghorn Model. J Biomed Biotechnol 2010, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyszyńska, A.; Raczko, A.; Lis, M.; Jagusztyn-Krynicka, E.K. Oral Immunization of Chickens with Avirulent Salmonella Vaccine Strain Carrying C. Jejuni 72Dz/92 CjaA Gene Elicits Specific Humoral Immune Response Associated with Protection against Challenge with Wild-Type Campylobacter. Vaccine 2004, 22, 1379–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoret, J.R.; Cooper, K.K.; Zekarias, B.; Roland, K.L.; Law, B.F.; Curtiss, R.; Joens, L.A. The Campylobacter Jejuni Dps Homologue Is Important for in Vitro Biofilm Formation and Cecal Colonization of Poultry and May Serve as a Protective Antigen for Vaccination. Clinical and Vaccine Immunology 2012, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-Barrios, P.; Hempen, M.; Messens, W.; Stella, P.; Hugas, M. Quantitative Microbiological Risk Assessment (QMRA) of Food-Borne Zoonoses at the European Level. Food Control 2013, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meunier, M.; Guyard-Nicodème, M.; Vigouroux, E.; Poezevara, T.; Beven, V.; Quesne, S.; Bigault, L.; Amelot, M.; Dory, D.; Chemaly, M. Promising New Vaccine Candidates against Campylobacter in Broilers. PLoS One 2017, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meunier, M.; Guyard-Nicodème, M.; Hirchaud, E.; Parra, A.; Chemaly, M.; Dory, D. Identification of Novel Vaccine Candidates against Campylobacter through Reverse Vaccinology. J Immunol Res 2016, 2016, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chintoan-Uta, C.; Cassady-Cain, R.L.; Stevens, M.P. Evaluation of Flagellum-Related Proteins FliD and FspA as Subunit Vaccines against Campylobacter Jejuni Colonisation in Chickens. Vaccine 2016, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.D.; Oakes, R.D.; Redhead, K.; Crouch, C.F.; Francis, M.J.; Tomley, F.M.; Blake, D.P. Eimeria Species Parasites as Novel Vaccine Delivery Vectors: Anti-Campylobacter Jejuni Protective Immunity Induced by Eimeria Tenella-Delivered CjaA. Vaccine 2012, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corona-Torres, R.; Vohra, P.; Chintoan-Uta, C.; Bremner, A.; Terra, V.S.; Mauri, M.; Cuccui, J.; Vervelde, L.; Wren, B.W.; Stevens, M.P. Evaluation of a FlpA Glycoconjugate Vaccine with Ten N-Heptasaccharide Glycan Moieties to Reduce Campylobacter Jejuni Colonisation in Chickens. Vaccines (Basel) 2024, 12, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Guo, F.; Guo, J.; Cao, X.; Wang, H.; Yang, B.; Zhou, H.; Su, X.; Zeng, X.; Lin, J.; et al. Immunization of Chickens with the Enterobactin Conjugate Vaccine Reduced Campylobacter Jejuni Colonization in the Intestine. Vaccines (Basel) 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gloanec, N.; Guyard-Nicodème, M.; Brunetti, R.; Quesne, S.; Keita, A.; Chemaly, M.; Dory, D. Evaluation of Two Recombinant Protein-Based Vaccine Regimens against Campylobacter Jejuni: Impact on Protection, Humoral Immune Responses and Gut Microbiota in Broilers. Animals 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorain, C.; Singh, A.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Kundu, A.; Lahiri, A.; Gupta, S.; Mallick, A.I. Mucosal Delivery of Live Lactococcus Lactis Expressing Functionally Active JlpA Antigen Induces Potent Local Immune Response and Prevent Enteric Colonization of Campylobacter Jejuni in Chickens. Vaccine 2020, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodgins, D.C.; Barjesteh, N.; St. Paul, M.; Ma, Z.; Monteiro, M.A.; Sharif, S. Evaluation of a Polysaccharide Conjugate Vaccine to Reduce Colonization by Campylobacter Jejuni in Broiler Chickens. 2015; 8. [CrossRef]

- Łaniewski, P.; Kuczkowski, M.; Chrzastek, K.; Woźniak, A.; Wyszyńska, A.; Wieliczko, A.; Jagusztyn-Krynicka, E.K. Evaluation of the Immunogenicity of Campylobacter Jejuni CjaA Protein Delivered by Salmonella Enterica Sv. Typhimurium Strain with Regulated Delayed Attenuation in Chickens. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 2014, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Xu, F.; Lin, J. Development and Evaluation of CmeC Subunit Vaccine against Campylobacter Jejuni. J Vaccines Vaccin 2010, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vohra, P.; Chintoan-uta, C.; Terra, V.S.; Bremner, A.; Cuccui, J.; Wren, B.W.; Vervelde, L.; Stevens, M.P. Evaluation of Glycosylated FLPA and SODB as Subunit Vaccines against Campylobacter Jejuni Colonisation in Chickens. Vaccines (Basel) 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vohra, P.; Chintoan-Uta, C.; Bremner, A.; Mauri, M.; Terra, V.S.; Cuccui, J.; Wren, B.W.; Vervelde, L.; Stevens, M.P. Evaluation of a Campylobacter Jejuni N-Glycan-ExoA Glycoconjugate Vaccine to Reduce C. Jejuni Colonisation in Chickens. Vaccine 2021, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandeputte, J.; Martel, A.; Van Rysselberghe, N.; Antonissen, G.; Verlinden, M.; De Zutter, L.; Heyndrickx, M.; Haesebrouck, F.; Pasmans, F.; Garmyn, A. In Ovo Vaccination of Broilers against Campylobacter Jejuni Using a Bacterin and Subunit Vaccine. Poult Sci 2019, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha-Abdelaziz, K.; Hodgins, D.C.; Alkie, T.N.; Quinteiro-Filho, W.; Yitbarek, A.; Astill, J.; Sharif, S. Oral Administration of PLGA-Encapsulated CpG ODN and Campylobacter Jejuni Lysate Reduces Cecal Colonization by Campylobacter Jejuni in Chickens. Vaccine 2018, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Nisaa, K.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Mallick, A.I. Immunogenicity and Protective Efficacy of Mucosal Delivery of Recombinant Hcp of Campylobacter Jejuni Type VI Secretion System (T6SS)in Chickens. Mol Immunol 2019, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radomska, K.A.; Vaezirad, M.M.; Verstappen, K.M.; Wösten, M.M.S.M.; Wagenaar, J.A.; Van Putten, J.P.M. Chicken Immune Response after in Ovo Immunization with Chimeric TLR5 Activating Flagellin of Campylobacter Jejuni. PLoS One 2016, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibanda, N.; McKenna, A.; Richmond, A.; Ricke, S.C.; Callaway, T.; Stratakos, A.C.; Gundogdu, O.; Corcionivoschi, N. A Review of the Effect of Management Practices on Campylobacter Prevalence in Poultry Farms. Front Microbiol 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boodhoo, N.; Shoja Doost, J.; Sharif, S. Biosensors for Monitoring, Detecting, and Tracking Dissemination of Poultry-Borne Bacterial Pathogens Along the Poultry Value Chain: A Review. Animals 2024, 14, 3138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilli, G.; Laconi, A.; Galuppo, F.; Mughini-Gras, L.; Piccirillo, A. Assessing Biosecurity Compliance in Poultry Farms: A Survey in a Densely Populated Poultry Area in North East Italy. Animals 2022, 12, 1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelaude, P.; Schlepers, M.; Verlinden, M.; Laanen, M.; Dewulf, J. Biocheck. UGent: A Quantitative Tool to Measure Biosecurity at Broiler Farms and the Relationship with Technical Performances and Antimicrobial Use. Poult Sci 2014, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, S.; Meade, K.G.; Allan, B.; Lloyd, A.T.; Kenny, E.; Cormican, P.; Morris, D.W.; Bradley, D.G.; O’Farrelly, C. Avian Resistance to Campylobacter Jejuni Colonization Is Associated with an Intestinal Immunogene Expression Signature Identified by MRNA Sequencing. PLoS One 2012, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.K.; Kaiser, P.; Rothwell, L.; Humphrey, T.; Barrow, P.A.; Jones, M.A. Campylobacter Jejuni-Induced Cytokine Responses in Avian Cells. Infect Immun 2005, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaughnessy, R.G.; Meade, K.G.; Cahalane, S.; Allan, B.; Reiman, C.; Callanan, J.J.; O’Farrelly, C. Innate Immune Gene Expression Differentiates the Early Avian Intestinal Response between Salmonella and Campylobacter. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 2009, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Li, D.; Yang, X.; Wei, F.; Wen, Q.; Feng, Y.; Jin, X.; Liu, D.; Guo, Y.; Hu, Y. Integrated Multi-Omics Reveals the Roles of Cecal Microbiota and Its Derived Bacterial Consortium in Promoting Chicken Growth. mSystems 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, L.; Soh, P.X.Y.; McEnearney, T.E.; Cain, J.A.; Dale, A.L.; Cordwell, S.J. Multi-Omics of Campylobacter Jejuni Growth in Chicken Exudate Reveals Molecular Remodelling Associated with Altered Virulence and Survival Phenotypes. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagle, B.R.; Quach, A.; Yeo, S.; Assumpcao, A.L.F.V.; Arsi, K.; Donoghue, A.M.; Jesudhasan, P.R.R. A Multiomic Analysis of Chicken Serum Revealed the Modulation of Host Factors Due to Campylobacter Jejuni Colonization and In-Water Supplementation of Eugenol Nanoemulsion. Animals 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Xu, H.; Ning, C.; Xiang, L.; Ren, Q.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, R. Multi-Omics Approach Reveals the Potential Core Vaccine Targets for the Emerging Foodborne Pathogen Campylobacter Jejuni. Front Microbiol 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Psifidi, A.; Kranis, A.; Rothwell, L.M.; Bremner, A.; Russell, K.; Robledo, D.; Bush, S.J.; Fife, M.; Hocking, P.M.; Banos, G.; et al. Quantitative Trait Loci and Transcriptome Signatures Associated with Avian Heritable Resistance to Campylobacter. Sci Rep 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psifidi, A.; Fife, M.; Howell, J.; Matika, O.; van Diemen, P.M.; Kuo, R.; Smith, J.; Hocking, P.M.; Salmon, N.; Jones, M.A.; et al. The Genomic Architecture of Resistance to Campylobacter Jejuni Intestinal Colonisation in Chickens. BMC Genomics 2016, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintel, B.K.; Prongay, K.; Lewis, A.D.; Raué, H.-P.; Hendrickson, S.; Rhoades, N.S.; Messaoudi, I.; Gao, L.; Slifka, M.K.; Amanna, I.J. Vaccine-Mediated Protection against Campylobacter -Associated Enteric Disease. Sci Adv 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meunier, M.; Guyard-Nicodème, M.; Hirchaud, E.; Parra, A.; Chemaly, M.; Dory, D. Identification of Novel Vaccine Candidates against Campylobacter through Reverse Vaccinology. J Immunol Res 2016, 2016, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Kumar, A. Designing an Efficient Multi-Epitope Vaccine against Campylobacter Jejuni Using Immunoinformatics and Reverse Vaccinology Approach. Microb Pathog 2020, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saggese, A.; Baccigalupi, L.; Donadio, G.; Ricca, E.; Isticato, R. The Bacterial Spore as a Mucosal Vaccine Delivery System. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śmiałek, M.; Kowalczyk, J.; Koncicki, A. The Use of Probiotics in the Reduction of Campylobacter Spp. Prevalence in Poultry. Animals 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, J.; Looft, T.; Zhang, Q.; Sahin, O. Deciphering the Association between Campylobacter Colonization and Microbiota Composition in the Intestine of Commercial Broilers. Microorganisms 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, J.; Beyi, A.F.; Looft, T.; Zhang, Q.; Sahin, O. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Reduces Campylobacter Jejuni Colonization in Young Broiler Chickens Challenged by Oral Gavage but Not by Seeder Birds. Antibiotics 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gölz, G.; Rosner, B.; Hofreuter, D.; Josenhans, C.; Kreienbrock, L.; Löwenstein, A.; Schielke, A.; Stark, K.; Suerbaum, S.; Wieler, L.H.; et al. Relevance of Campylobacter to Public Health–the Need for a One Health Approach. International Journal of Medical Microbiology 2014, 304, 817–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babo Martins, S.; Rushton, J.; Stärk, K.D.C. Economics of Zoonoses Surveillance in a “One Health” Context: An Assessment of Campylobacter Surveillance in Switzerland. Epidemiol Infect 2017, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharafutdinov, I.; Linz, B.; Tegtmeyer, N.; Backert, S. Therapeutic and Protective Approaches to Combat Campylobacter Jejuni Infections. Front Pharmacol 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).