1. Introduction

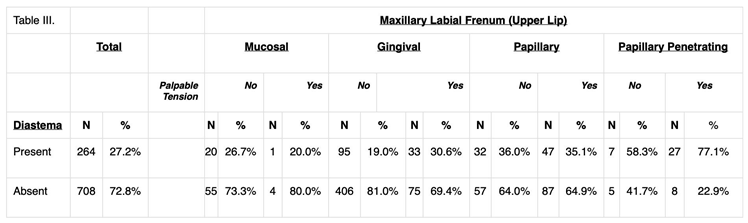

The maxillary labial frenum, also known as the upper labial frenum or superior labial frenum, is a small fold of tissue composed of mucosa and connective tissue that connects the up- per lip to the gingival tissue above the maxillary central incisors (

Figure 1) [

1]. The maxillary labial frenum often varies in size, shape, thickness, tightness, and attachment site between differ- ent individuals. Most babies are born with a frenum that inserts near the alveolar ridge (

Figure 2) [

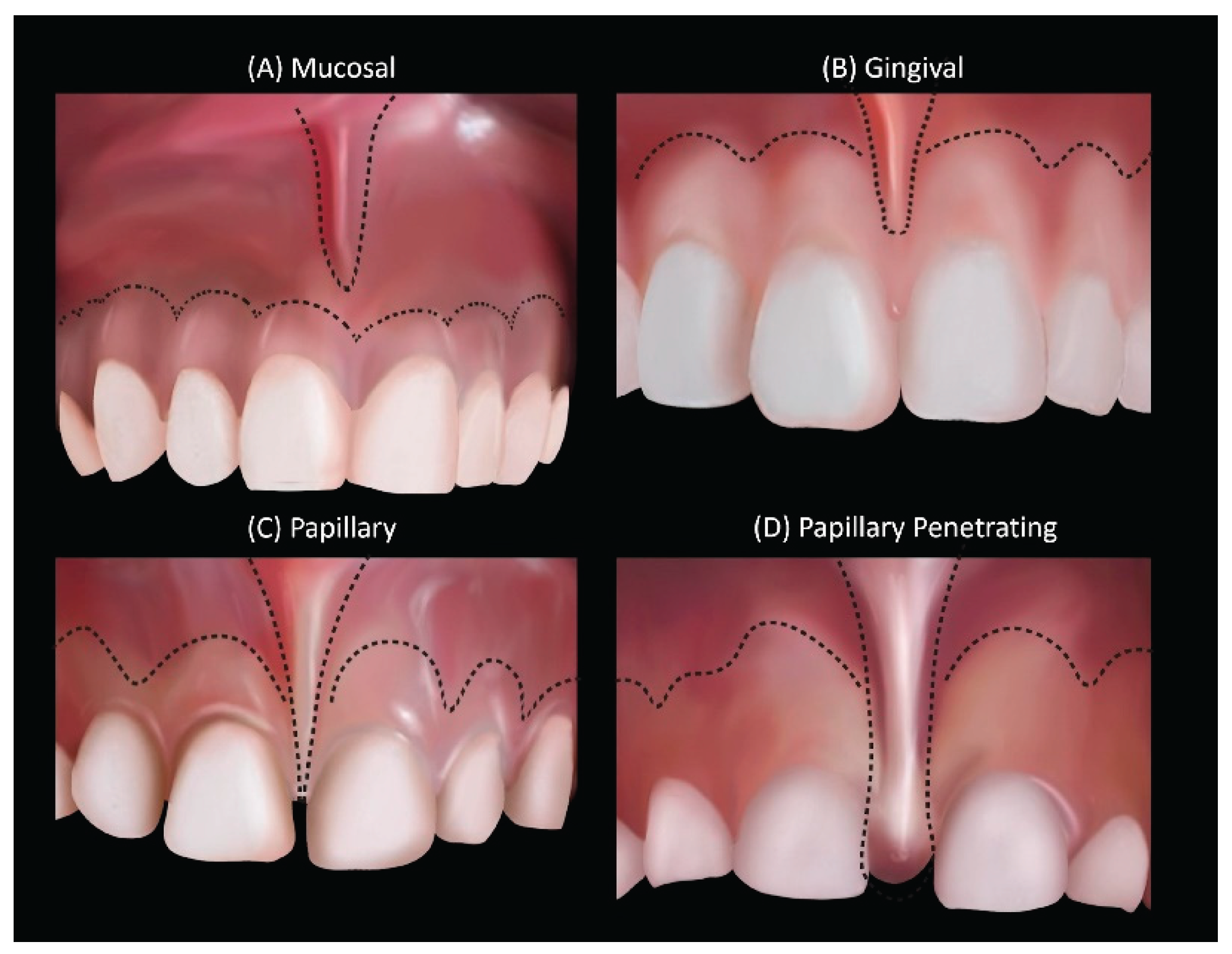

2]. Labial frenum are classified as mucosal, gingival, papillary, and papillary penetrating based on the location of the attachment site or insertion point [

3,

4].

A restrictive labial frenum is called “ankylolabia” and is more commonly known as “lip-tie” [

5,

6]. The maxillary labial frenum is considered restrictive when there are specific structural characteristics (such as palpable tension or visual blanching of the tissue when lifting) that direct- ly contribute to significant functional concerns. Among studies focused on infants, a restrictive maxillary labial frenum in certain cases has been associated with difficulty in nursing and bottle feeding, trouble with reflux, gassiness, and other infant issues involving aerophagia [

7,

8,

9,

10]. In children, previous studies have reported issues with speech, especially bilabial speech sounds (/b/, /p/, /m/, and /w/), lip incompetence leading to mouth breathing, predisposition to dental caries, and diastema between the front teeth [

11,

12]. Studies on the maxillary labial frenum in adults are limited [

13].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This cross-sectional study recruited a convenience sample of 1086 subjects who presented for routine dental examinations at two private pediatric dentistry clinics. Data were collected prospectively by two pediatric dentists (SS, CH) who were trained and formally calibrated on the assessments. This study was approved by the human subject ethics board of the University ofCalifornia Los Angeles (UCLA) Institutional Review Board (IRB approval #22-001626) and was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 as revised in 2013. The study conforms to STROBE standards for cross-sectional studies [

18]. This study was self-funded.

2.2. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Subjects with a history of prior maxillary labial frenectomy were excluded. There was no exclusion based on other factors, such as special needs.

2.3. Data Collection

The following characteristics were recorded: age, sex, history of prior labial frenectomy, dentition type (primary, mixed, permanent), and presence of diastema between the central maxil- lary incisors. Assessment and classification of the maxillary and mandibular labial frenum were performed for the maxillary and mandibular labial frenum, respectively, based on the following criteria: (1) insertion site or attachment point of the labial frenum (mucosal, gingival, papillary, papillary penetrating); (2) presence of palpable tension when lifting or retracting the lip (yes or no) [

11,

18,

19]. Palpable tension was assessed by manually retracting the lip and running a finger across the frenum, noting the presence of any resistance or strain contrasting with the surrounding soft tissue.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using JMP Pro 16.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Continuous vari- ables were summarized as mean (M) ± standard deviation (SD). Categorical variables were sum- marized as frequencies and percentages ± standard error (SE). Univariate analysis with Pearson Chi-Square was performed to assess the associations of the various characteristics based on age cohort and dentition type. Bonferroni correction was applied to the interpretation of statistical significance due to the testing of multiple variables for each outcome, such that a two-tailed p- value of <0.001 was required to achieve statistical significance. The sample size required to as- sess a 10% difference in proportions between age cohorts, assuming a standard deviation of 20% with alpha = 0.001 and power of 99.9%, was calculated as n=511.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

Among the 1086 subjects who were assessed, 18 were excluded due to a history of prior maxillary labial frenectomy. As such, 1068 subjects were included in the study with a mean age of 9.3 ± 5.3 years, ranging from a 1-day-old infant to 47 years old. The study population com- prised 28% primary dentition (n=279), 51% mixed dentition (n=507), and 21% permanent denti- tion cases (n=209); there were n=73 cases where dentition status was not recorded. The sex dis- tribution was 52.7% females (n=558) and 47.3% males (n=501); there were n=9 cases where sex was not recorded.

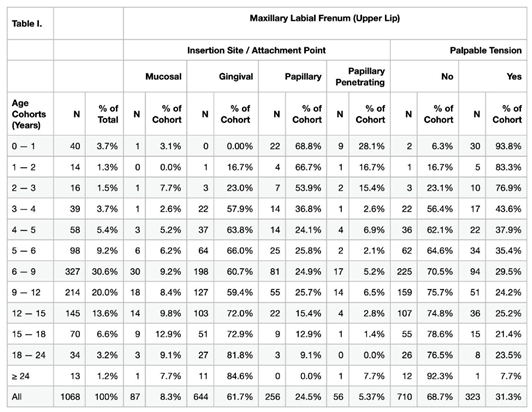

3.2. Maxillary Labial Frenum: Morphology by Age-Cohort and Dentition Type

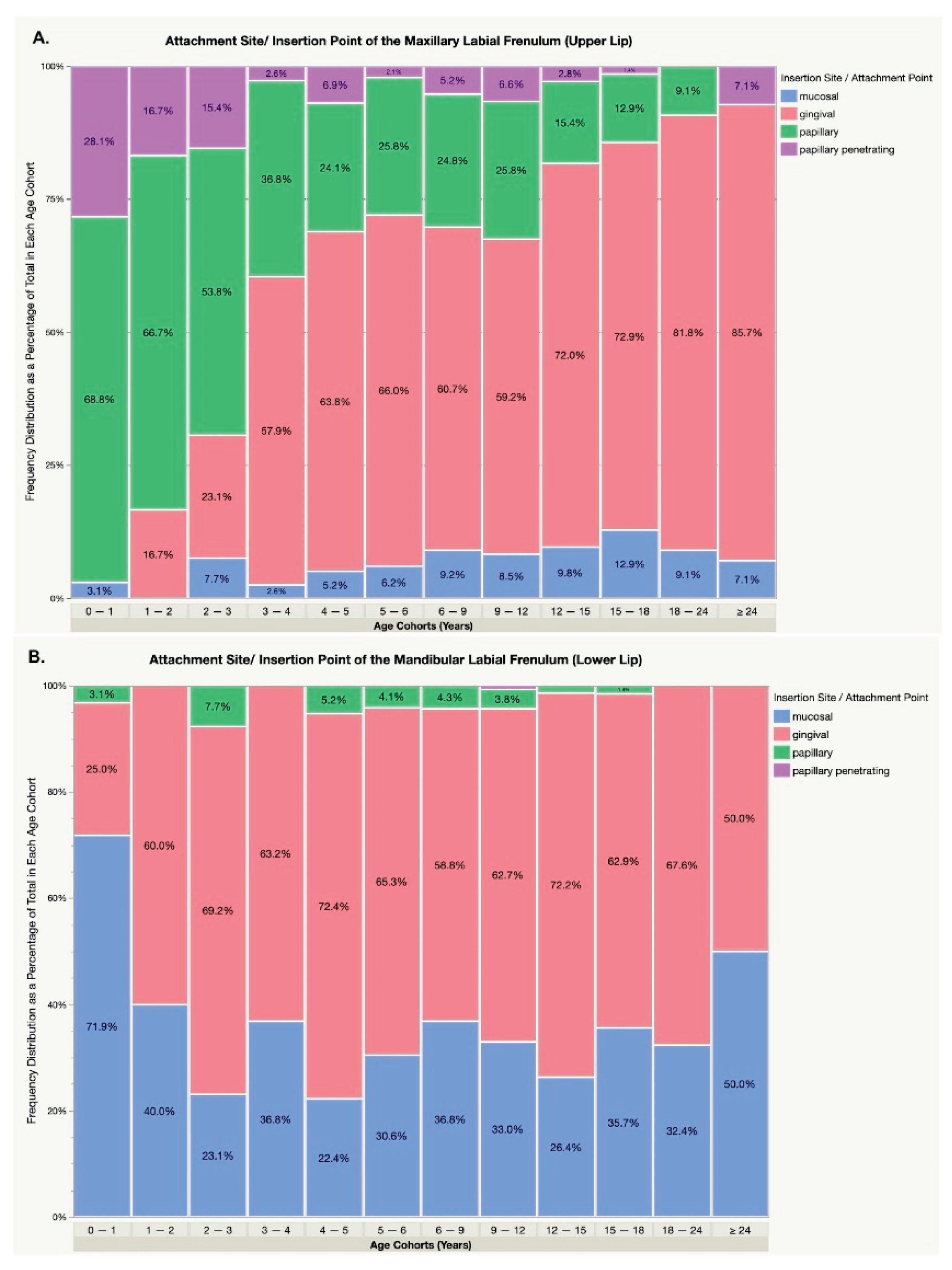

Statistical analysis showed a significant association between age and the attachment site of the maxillary labial frenum, with a transition from papillary and papillary penetrating to gingival and mucosal attachments across age cohorts (Pearson Chi-Square Analysis, p<0.001). (Table I). In the age groups 0-3 years compared to ≥3 years, the observed frequencies of attachment sites were: mucosal (3.9% vs. 8.6%), gingival (7.8% vs. 64.5%), papillary (64.7% vs. 22.5%), and papillary penetrating (23.5% vs. 4.4%). (

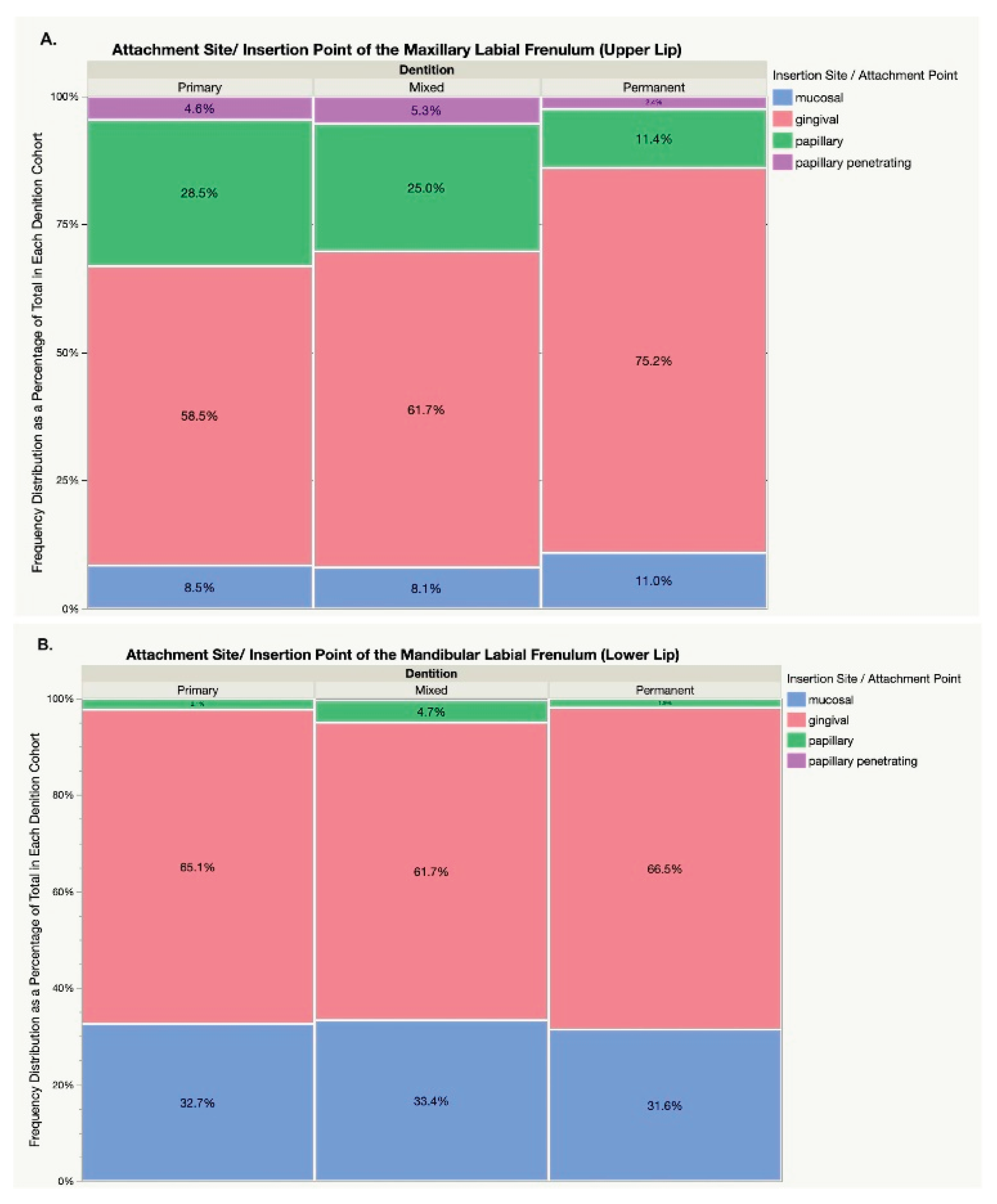

Figure 3). Additionally, the presence of permanent dentition significantly reduced the incidence of papillary attachments compared to mixed and prima- ry dentition (11.4% vs. 25.0% and 28.5%, respectively; p<0.001). (

Figure 4).

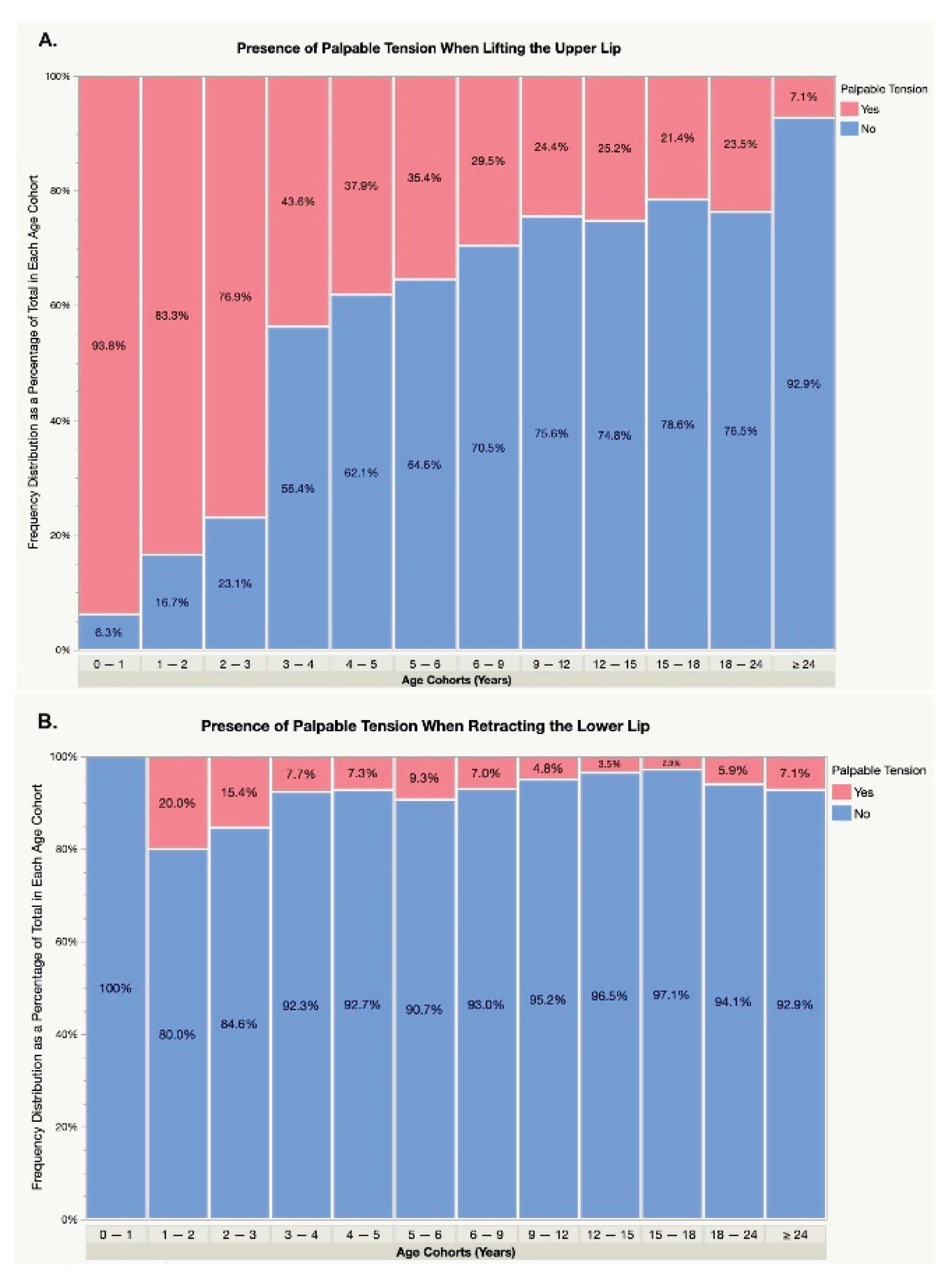

3.3. Maxillary Labial Frenum: Incidence of Palpable Tension by Age Cohort

Statistical analysis demonstrated significant correlation between age and the presence of palpable tension in the maxillary labial frenum when lifting the upper lip (p<0.001). The inci- dence of palpable tension was highest in infants under one year at over 90%, followed by 80% in children aged 1-3 years, 30-40% in children aged 3-9 years, 20-25% in individuals aged 9-24 years, and under 10% in adults over 24 years. (

Figure 5).

3.4. Mandibular Labial Frenum: Morphology by Age-Cohort and Dentition Type

The incidence of papillary and papillary penetrating insertion was overall low for all age cohorts (35/1041, 3.7 ± 3.4%, range 0–12.9%) with no clinically significant difference or percep- tible trend between the age cohorts (p=0.08). (Table II) and (

Figure 3). There was no significant association between the dentition type and attachment site for the mandibular labial frenum (p=0.35). (

Figure 4).

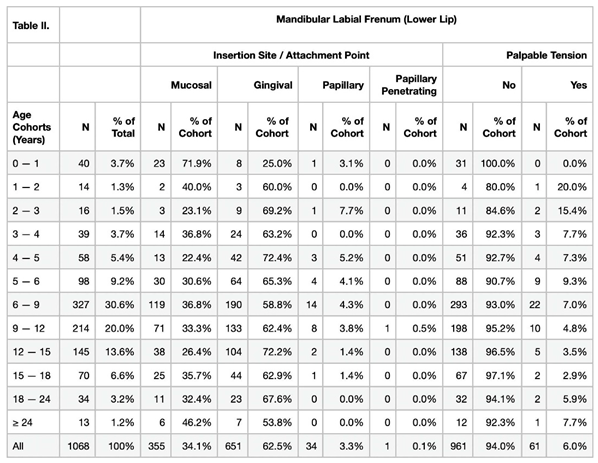

3.5. Diastema Between Maxillary Central Incisors: Association with Maxillary Labial Frenum Morphology and Palpable Tension

The overall incidence of diastema between maxillary central incisors was 27.1% (264/972). The incidence of diastema was significantly higher in the papillary penetrating and papillary max- illary labial frenum phenotypes (34/47, 72.3 ±6.5 % and 70/225, 31.1 ± 3.1%, respectively) than in the gingival and mucosal attachments (128/612, 20.9 ± 1.6% and 23/85, 27.1± 4.8%, respec- tively; p <0.001). The presence of palpable tension was also associated with an increased likeli- hood of diastema (108/283, 38.2 ± 2.9% vs. 154/678, 22.7± 1.6%; p<0.001). (Table III).

4. Discussion

The maxillary labial frenum is a highly variable yet normal anatomical structure that appears to change in morphology in most individuals by 3-6 years of age. The results of this study show that in infants and toddlers under three years old, most patients had a papillary-penetrating or papillary maxillary labial frenum, and as they matured, especially above 3 years of age, the frenum was found to be in a more apical position, resulting in a gingival or even mucosal presen- tation. The incidence of palpable tension when elevating the upper lip decreases with age, with the highest incidence in infants and decreasing through preschool, school age, adolescence, and adulthood. A diastema between the maxillary central incisors mainly occurred with papillary pen- etration and papillary maxillary labial frenum. Increased tension in the maxillary labial frenum was also associated with diastema.

These patterns, trends, and variations with age did not hold for the mandibular labial frenum. Most mandibular labial frena are mucosal or gingival attachments with little variation across ages. The incidence of papillary attachment and the presence of palpable tension are low and often associated with only minimal clinical impact. Some studies have shown that a restric- tive mandibular labial frenum may contribute to recession, and in those cases, frenectomy and gingival graft have been shown to benefit the patient. [

14,

15,

16,

17]

Additional support for the age-related shift in frenum morphology is provided by retrospective data demonstrating that nearly half of children exhibited a Kotlow class 3 maxillary frenum in early childhood, with scores decreasing significantly with age. A higher Kotlow classification in younger children was also found to be strongly associated with frenotomy intervention and the presence of diastema, reinforcing the association between frenum phenotype, clinical tension, and dental spacing. [

27]

The observed apical migration of the frenum over time is likely influenced by multiple bio-logical processes. Histological reviews of primary dentition have highlighted the role of passive eruption and natural shedding of the dentition in driving this shift, supporting a model of tissue remodeling rather than purely traumatic or mechanical causes. [

28]

This is an observational study, and the findings are based only on cross-sectional data; moreover, the published literature only shows a few uncontrolled studies on these topics. Never- theless, based on current data and theories, the maxillary labial frenum appears to recede around 2 to 3 years of age and continues to evolve as the maxillary incisors are replaced and the canines erupt around the age of 6-12 years.20,21 The reasons for this finding are likely attributable to one of two main factors: (1) growth/development (the maxilla grows downward and forward, leading to a relative apical migration of the frenum from the papilla or at the alveolar ridge to a more gin- gival presentation), and (2) trauma during childhood. Labial frena are more prominent in younger children and naturally migrate apically during the growth of the craniofacial structures. Although many toddlers fall and rip the frenulum, it is often an incomplete release of the tissue and leaves an appendage or small nodule in the middle of the frenum where it is attached to the ridge. [

19,

22,

23] These two factors are likely to explain the findings.

In this study, papillary penetrating and papillary maxillary attachment sites were correlated with maxillary diastema, and especially in the presence of tension, diastema was more likely to be present. A recent study demonstrated that maxillary labial frenectomy has been associated with the resolution or decrease in the width of diastema in 94.5% of patients.11 The morphology of the maxillary labial frenum alone is not a singular predictive factor for diastema or other functional issues. Eruption, migration, teeth movement, the anterior component of the force of occlusion, and the increase in the size of jaws with accompanying increase in tonicity of facial musculature all tend to influence closure of diastema and apical migration of the maxillary labial frenum at- tachment. Orthodontic alignment can also influence the position and tension of both the maxillary and mandibular labial frenum [

20,

24,

25].

In infants, the maxillary labial frenum morphology is mostly papillary and papillary pene- trating, and the tension is high in most babies. Therefore, treatment based on appearance alone may result in unnecessary procedures since the frenum often but not always recedes in childhood. A symptom-based approach could be adopted to help address clinically impactful restrictive max- illary labial frenum in symptomatic infants and recommend watchful waiting to those without obvious symptoms. Infant symptoms may include an insufficient flange of the lips, leading to a poor seal at the breast or bottle, and can lead to aerophagia, or “eating air” [

7]. Associated symp- toms of air ingestion include gassiness, reflux, spitting up, fussiness, colic, and anterior loss of milk, which have been found to improve in certain patients after maxillary labial frenectomy [

12,

26].

The clinical implications of this cross-sectional study show that the maxillary frenum is highly variable in appearance, and a multifaceted treatment approach is warranted. Certainly, a low and tense frenum may cause significant issues in some infants or children, while a frenum of similar morphology may cause virtually no issues in others. The decision to perform maxillary labial frenectomy should be based on an awareness of the heterogeneous presentation, the poten- tial risks and benefits of treatment, as well as an awareness of the variation of the morphology and insertion of the frenum and how it may change without intervention over time.

These findings reinforce the need for clinicians to consider age, function, and frenum ten- sion, rather than visual appearance alone when evaluating the need for intervention.

Limitations: This was a cross-sectional observational study on frenum morphology. A longitudinal obser- vational study that follows individual patients would be more ideal.

5. Conclusions

Age-dependent variations in the morphology of the maxillary labial frenum appear to occur by around 3 to 6 years of age. Papillary attachment of the maxillary labial frenulum, especially in the setting of palpable tension, is associated with an increased incidence of diastema. The mandibular labial frenum did not appear to demonstrate age-dependent variations in morphology or attach- ment site.

These results underscore the importance of individualized assessment of frenum morphology and functional symptoms before recommending surgical intervention. Clinicians should consider both patient age and the presence of symptoms such as diastema, feeding challenges, or oral motor restrictions when determining whether treatment is warranted. Relying on visual appearance alone may lead to unnecessary procedures in cases where spontaneous regression is possible.

This study reinforces a developmental and functional approach to the evaluation of labial frena in pediatric populations. Further prospective longitudinal studies are recommended to clarify the natural history of frenum migration and its relationship to clinical outcomes, which may help guide optimal timing and indications for intervention.

Author Contributions

Dr Audrey Yoon and Dr. Soroush Zaghi conceptualized and designed the study, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. Dr Shifa Shamsudeen, and Dr. Caroline Hu designed the data collection instruments, collected data, carried out the initial analyses, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. Dr. Richard Baxter drafted the initial manuscript, critically reviewed, and revised the manuscript. Dr. Reuben Kim conceptualized and designed the study, processed IRB, supervised data collection and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Decla- ration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Cali- fornia, Los Angeles (IRB#22-001626; exemption certified on January 25, 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the retrospective design of the study and the use of fully de-identified data collected during routine dental examinations. The study was approved as exempt by the UCLA Institutional Review Board (IRB#22-001626).

Data Availability Statement

New data was created and analyzed.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Leyli Norouz-Knutsen and The Breathe Institute for their support with manuscript formatting and assistance during the submission process. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publica- tion.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have indicated they have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IRB |

Institutional Review Board |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

| SE |

Standard Error |

| STROBE |

Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology |

References

- Henry, S.W.; Levin, M.P.; Tsaknis, P.J. Histologic features of the superior labial frenum. J Periodontol. 1976, 47, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flinck, A.; Paludan, A.; Matsson, L.; Holm, A.K.; Axelsson, I. Oral findings in a group of newborn Swedish children. Int J Paediatr Dent. 1994, 4, 67–73. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7748853. [CrossRef]

- Santa Maria, C.; Aby, J.; Truong, M.T.; Thakur, Y.; Rea, S.; Messner, A. The Superior Labial Frenulum in Newborns: What Is Normal? Glob Pediatr Health. 2017, 4, 2333794X17718896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotlow, L.A. Oral diagnosis of abnormal frenum attachments in neonates and infants: evaluation and treatment of the maxillary and lingual frenum using the Erbium: YAG laser. J Pediatric Dent Care. 2004, 10, 11–14. https://www.kiddsteeth.com/assets/ pdfs/articles/finaslttfrenarticleoct2004.pdf.

- Siegel, S.A. Surgical treatment of tethered oral tissues (TOTs): Effects on speech articulation disorders in children a review. Res Pediatr Neonatol 2018. Published online June 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Walner, D.L.; Popova, Y.; Walner, E.G. Tongue-tie and breastfeeding. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2022, 160, 111242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, S.A. Aerophagia Induced Reflux in Breastfeeding Infants With Ankyloglossia and Shortened Maxillary Labial Frenula (Tongue and Lip Tie). International Journal of Clinical Pediatrics. 2016, 5, 6–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaheri, B.A.; Cole, M.; Fausel, S.C.; Chuop, M.; Mace, J.C. Breastfeeding improvement following tongue-tie and lip-tie release: A prospective cohort study. Laryngoscope. 2017, 127, 1217–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benoiton, L.; Morgan, M.; Baguley, K. Management of posterior ankyloglossia and upper lip ties in a tertiary otolaryngology out- patient clinic. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2016, 88, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pransky, S.M.; Lago, D.; Hong, P. Breastfeeding difficulties and oral cavity anomalies: The influence of posterior ankyloglossia and upper-lip ties. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2015, 79, 1714–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, R.T.; Zaghi, S.; Lashley, A.P. Safety and efficacy of maxillary labial frenectomy in children: A retrospective comparative cohort study. Int Orthod 2022, 100630, Published online March 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, R.; Agarwal, R.; Musso, M.; et al. Tongue-Tied: How a Tiny String Under the Tongue Impacts Nursing, Speech, Feeding, and More. 1 edition. Alabama Tongue-Tie Center; 2018. https://www.amazon.com/Tongue-Tied-String-Impacts-Nursing-Feed- ing/dp/1732508208/ref=tmm_pap_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=1531133036&sr=1-1.

- Townsend, J.A.; Brannon, R.B.; Cheramie, T.; Hagan, J. Prevalence and variations of the median maxillary labial frenum in children, adolescents, and adults in a diverse population. Gen Dent. 2013, 61, 57–60, quiz 61. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/ 23454324. [PubMed]

- Jati, A.S.; Furquim, L.Z.; Consolaro, A. Gingival recession: its causes and types, and the importance of orthodontic treatment. Dental Press J Orthod. 2016, 21, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoner, J.E.; Mazdyasna, S. Gingival recession in the lower incisor region of 15-year-old subjects. J Periodontol. 1980, 51, 74–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monnet-Corti, V.; Antezack, A.; Moll, V. Vestibular frenectomy in periodontal plastic surgery. Journal of Dentofacial Anomalies and Orthodontics. 2018, 21, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, D.; Fatima, N. “Gingival Recession And Root Coverage Up To Date, A literature Review. ” Dentistry Review. 2022, 2, 100008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007, 370, 1453–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyanka, M.; Sruthi, R.; Ramakrishnan, T.; Emmadi, P.; Ambalavanan, N. An overview of frenal attachments. J Indian Soc Peri- odontol. 2013, 17, 12–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.J.; Creath, C.J. The midline diastema: a review of its etiology and treatment. Pediatr Dent. 1995, 17, 171–179. https:// www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7617490. [PubMed]

- Taylor, J.E. Clinical observations relating to the normal and abnormal frenum labii superioris. Am J Orthod Oral Surg. 1939, 25, 646–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Children’s Hospital Colorado. Mouth Injury. Accessed January 28, 2024. https://www.childrenscolorado.org/conditions-and- advice/conditions-and-symptoms/symptoms/mouth-injury/.

- Maguire, S.; Hunter, B.; Hunter, L.; et al. Diagnosing abuse: a systematic review of torn frenum and other intra-oral injuries. Arch Dis Child. 2007, 92, 1113–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajani, E.R.; Biswas, P.P.; Emmatty, R. Prevalence of variations in morphology and attachment of maxillary labial frenum in vari- ous skeletal patterns - A cross-sectional study. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2018, 22, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceremello, P.J. The superior labial frenum and the midline diastema and their relation to growth and development of the oral structures. Am J Orthod. 1953, 39, 120–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Callahan, C.; Macary, S.; Clemente, S. The effects of office-based frenotomy for anterior and posterior ankyloglossia on breastfeeding. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2013, 77, 827–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortin, T.; Chan, J.; Patel, A.; et al. Age-dependent trends in pediatric maxillary frenum classification: A retrospective cohort analysis. Int J Pediatr Dent. 2024, Forthcoming. [Manuscript in press. [Google Scholar]

- Soskolne, W.A.; Bimstein, E. Apical migration of the junctional epithelium in the primary dentition. J Clin Periodontol. 1989, 16, 473–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).