Submitted:

12 August 2025

Posted:

13 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Characterization Methods

2.3. Synthesis of Polymer Stabilized Gold Nanoparticles (AuNP@Polymer) in Water

2.3.1. Postsynthetic Addition Reaction

2.3.2. One-Pot Synthesis

2.4. Transfer of Polymer Stabilized Gold Nanoparticles (AuNP@Polymer) from Water to Ethanol

2.5. Loading of DASA on the AuNP@Polymer Conjugates

3. Results and Discussion

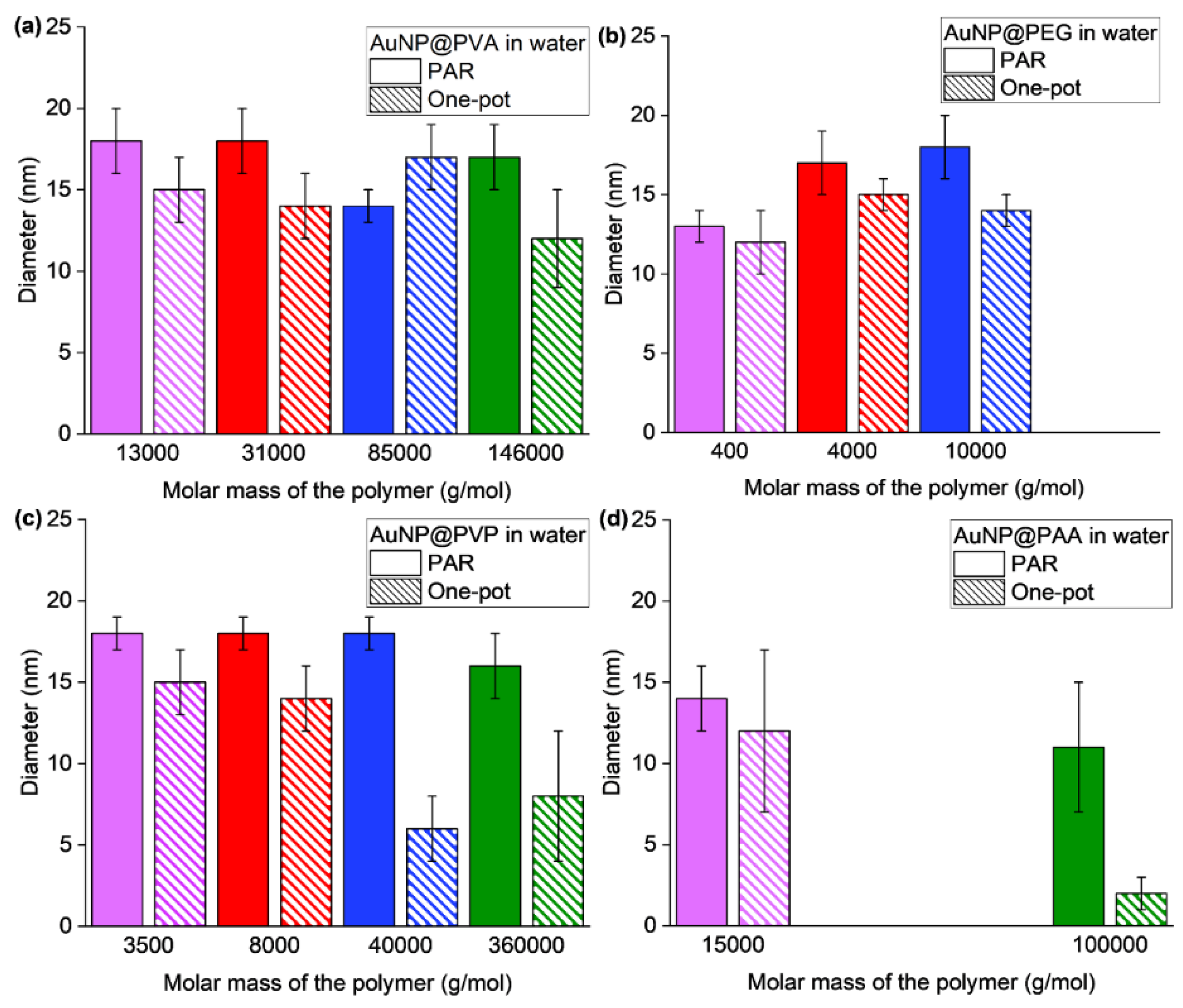

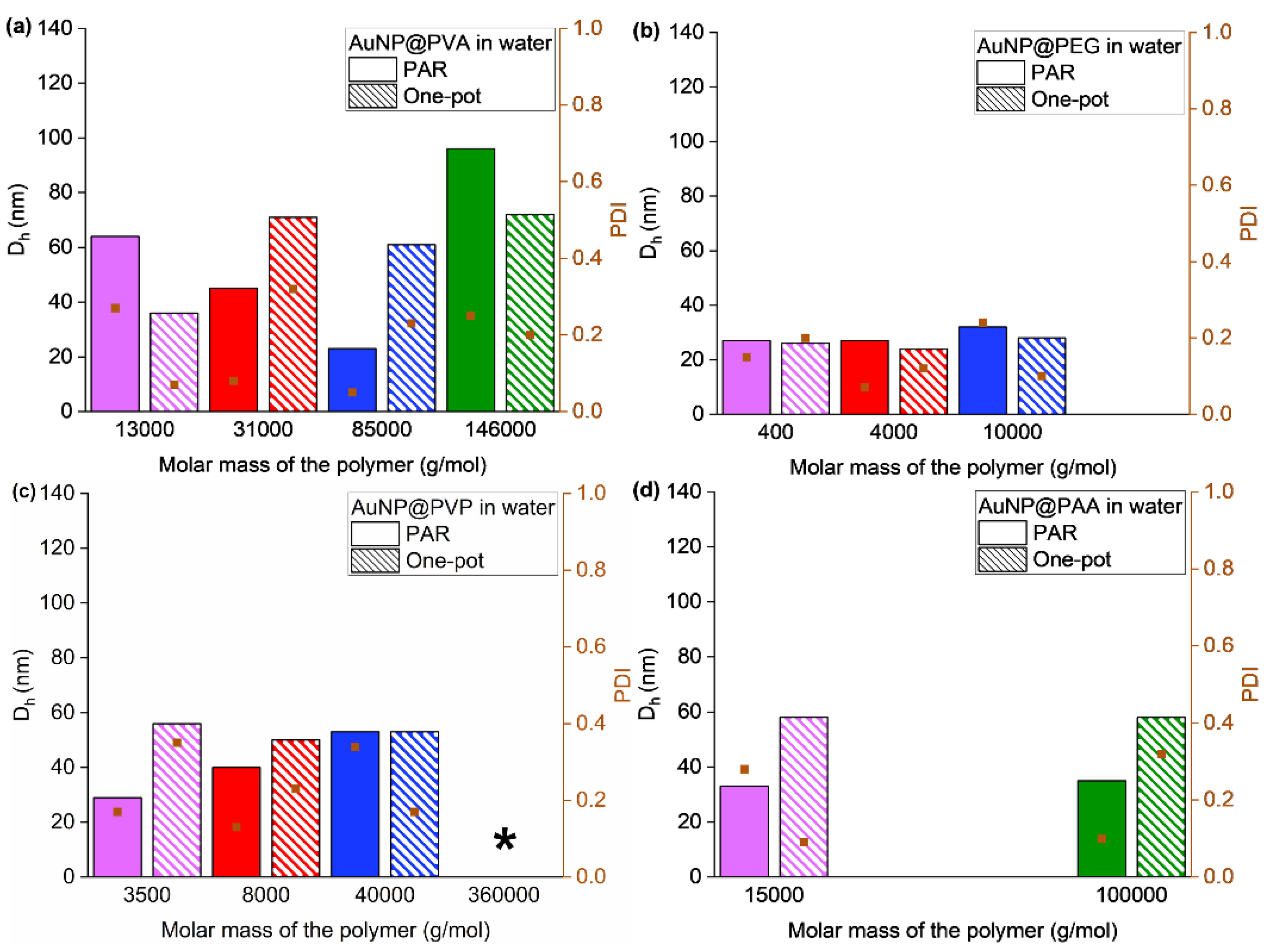

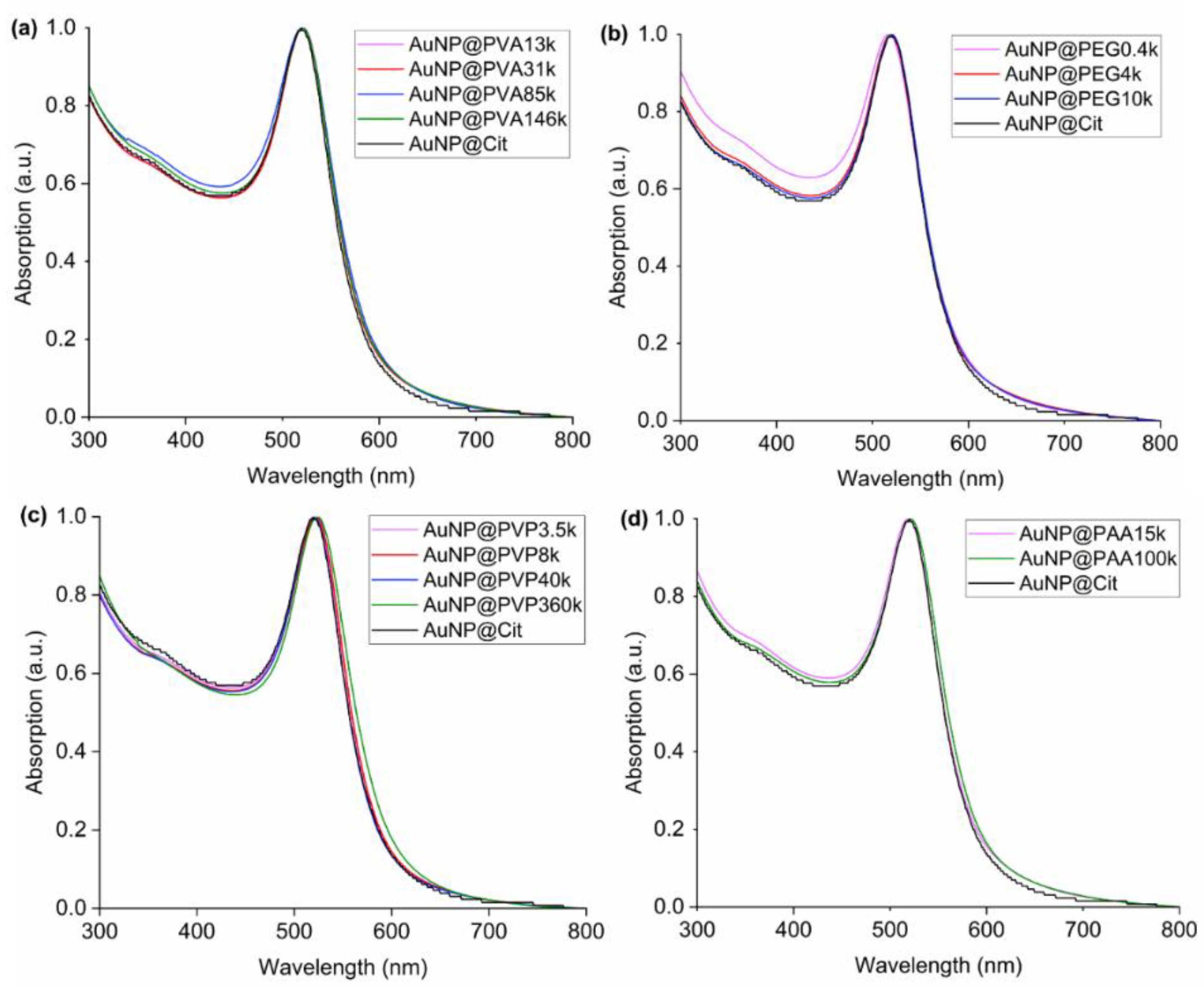

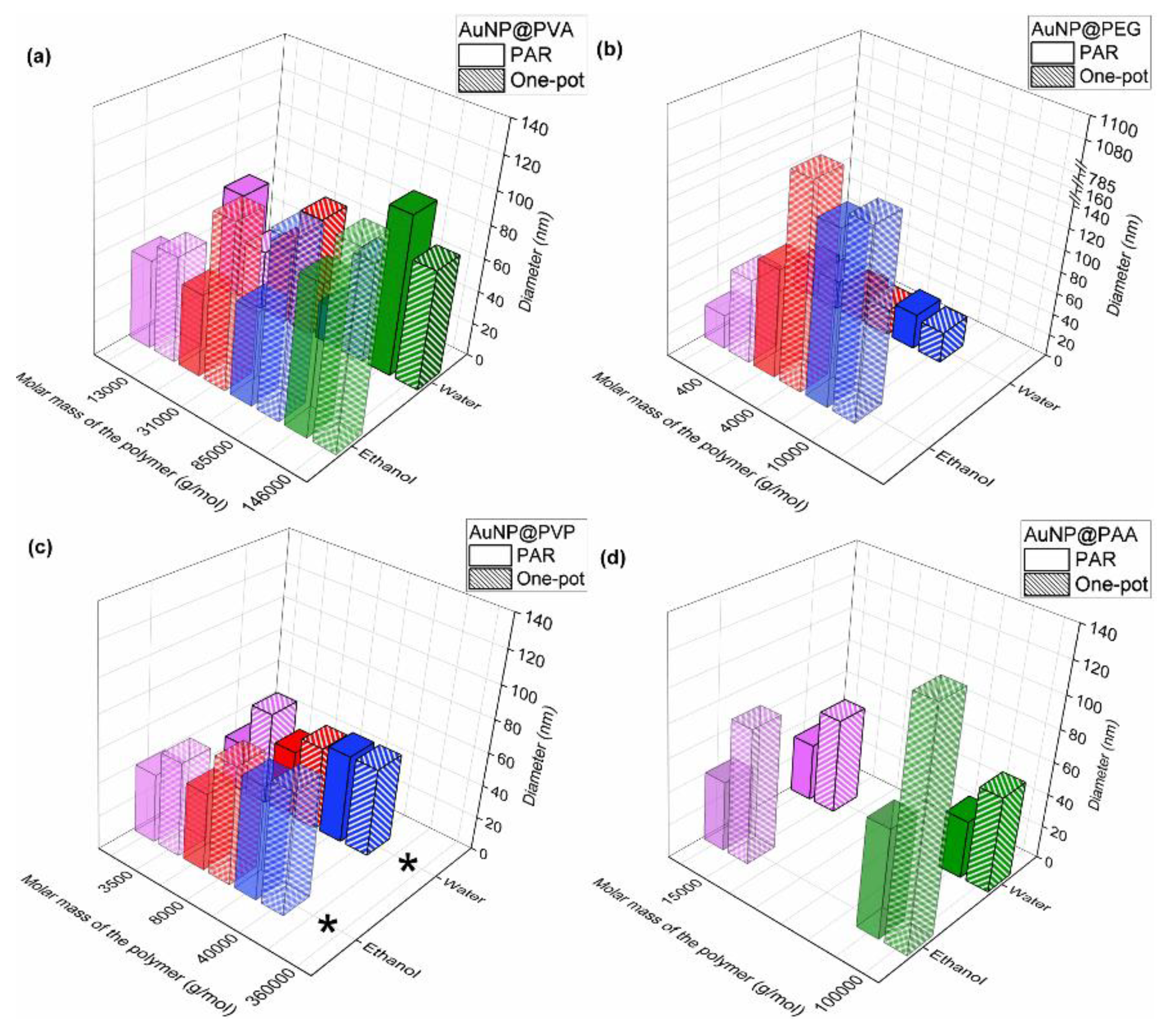

3.1. Synthesis and Characterization of the AuNP Samples in Water

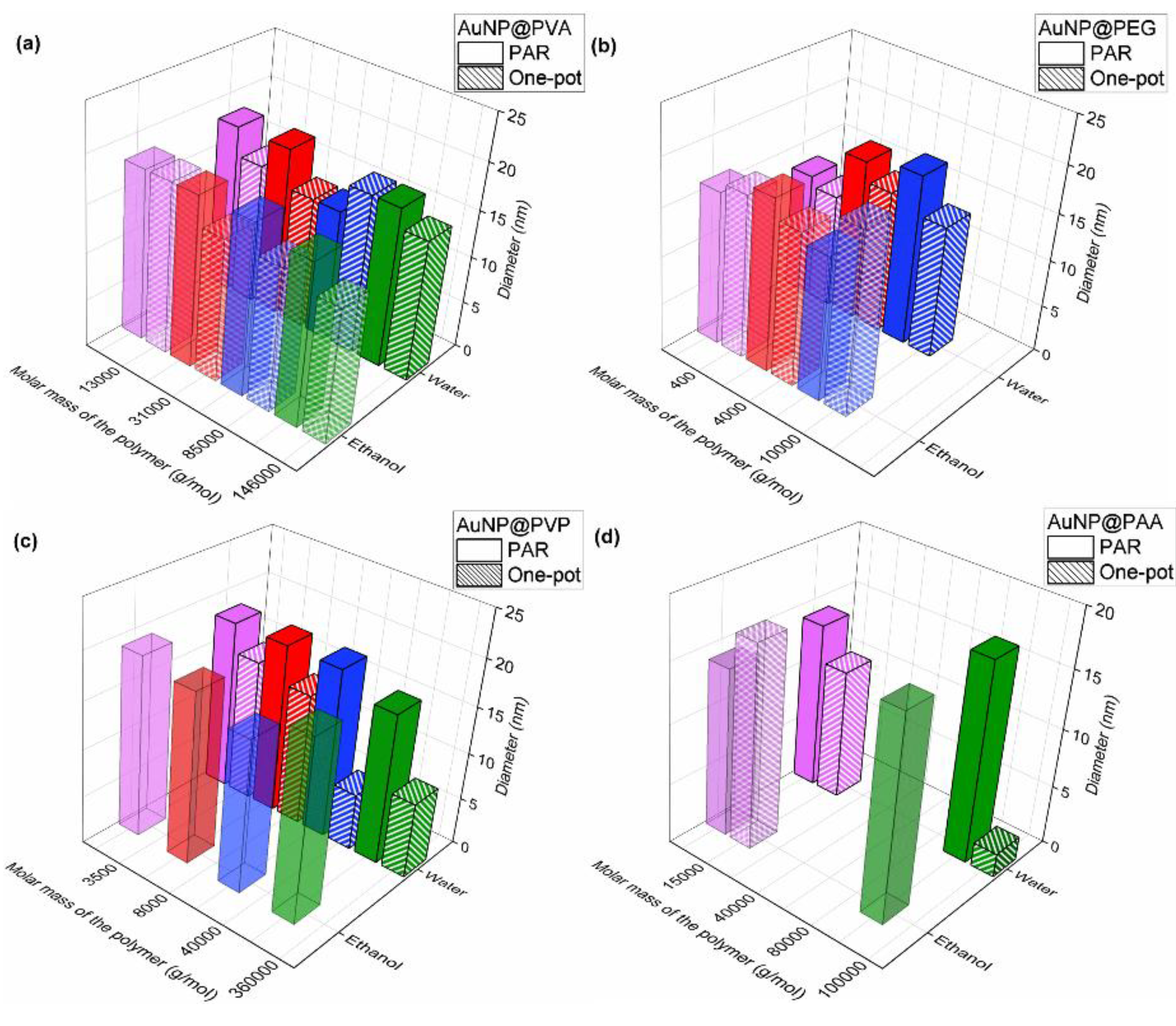

3.2. Characterization of the AuNP Samples Transferred to Ethanol

3.3. Loading of DASA on the AuNP@Polymer Conjugates

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AuNPs | Gold nanoparticles |

| PAR | Postsynthetic addition reaction |

| PVA | Poly(vinyl alcohol) |

| PEG | Poly(ethylene glycol) |

| PVP | Poly(vinyl pyrrolidone) |

| PAA | Poly(acrylic acid) |

| TEM | Transmission electron microscopy |

| DLS | Ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy |

| HPLC | High-performance liquid chromatography |

| NaCit | Sodium citrate dihydrate |

| PDI | Polydispersity index |

| DASA | Dasatinib |

References

- Liang, M.; Lin, I.-C.; Whittaker, M.R.; Minchin, R.F.; Monteiro, M.J.; Toth, I. Cellular Uptake of Densely Packed Polymer Coatings on Gold Nanoparticles. ACS Nano 2010, 4 (11), 403-413. [CrossRef]

- Richards, S.-J.; Gibson, M.I. Optimization of the Polymer Coating for Glycosylated Gold Nanoparticle Biosensors to Ensure Stability and Rapid Optical Readouts. ACS Macro Lett. 2014, 3 (10), 1004-1008. [CrossRef]

- Silva, V.C.J.D.; Silva, R.N.O.; Colli, L.G.; Carvalho, M.H.C.; Rodrigues, S.F. Gold nanoparticles carrying or not anti-VEGF antibody do not change glioblastoma multiforme tumor progression in mice. Heliyon 2020, 6 (11). [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.H.; Cho, J.; Ko, Y.T. Investigation on the effect of nanoparticle size on the blood-brain tumor barrier permeability by in situ perfusion via internal carotid artery in mice. J. Drug Target. 2018, 27 (1), 103-110. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Feng, X. Gold nanoparticles for skin drug delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 2022, 625, 122122. [CrossRef]

- Nejati, K.; Dadashpour, M., Gharibi, T.; Mellatyar, H.; Akbarzadeh, A. Biomedical Applications of Functionalized Gold Nanoparticles: A Review. J. Clust. Sci. 2022, 33, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Sani, A.; Cao, C.; Cui, D. Toxicity of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs): A review. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2021, 26, 100991. [CrossRef]

- Kesharwani, P., Ma, R., Sang, L.; Fatima, M.; Sheikh, A.; Abourehab, M.A.S.; Gupta, N.; Chen, Z.-S.; Zhou, Y. Gold nanoparticles and gold nanorods in the landscape of cancer therapy. Mol Cancer 2023, 22 (98),. [CrossRef]

- Jain, P.K.; Lee, K.S.; El-Sayed, I.H.; El-Sayed, M.A. Calculated Absorption and Scattering Properties of Gold Nanoparticles of Different Size, Shape, and Composition: Applications in Biological Imaging and Biomedicine. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110 (14), 7238-7248. [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; El-Sayed, I.H.; Qian, W.; El-Sayed, M.A. Cancer Cell Imaging and Photothermal Therapy in the Near-Infrared Region by Using Gold Nanorods. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128 (6), 2115-2120. [CrossRef]

- Ghobashy, M.M.; Alkhursani, S.A.; Alqahtani, H.A.; El-damhougy, T.K.; Madani, M. Gold Nanoparticles in microelectronics advancements and biomedical applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2024, 301, 117191. [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.H.; Abu Bakar, N.F.; Mustapa, A.N.; Low, K.-F.; Othman, N.H.; Adam, F. Synthesis of Various Size Gold Nanoparticles by Chemical Reduction Method with Different Solvent Polarity. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2020, 15 (140). [CrossRef]

- Aboudzadeh, M.A.; Kruse, J.; Iglesias, M.S.; Cangialosi, D.; Alegria, A.; Grzelczak, M.; Barroso-Bujans, F. Gold nanoparticles endowed with low-temperature colloidal stability by cyclic polyethylene glycol in ethanol. Soft Matter. 2021, 17 (33), 7792-7801. [CrossRef]

- Reznickova, A.; Slepicka, P.; Slavikova, N.; Staszek, M.; Svorcik, V. Preparation, aging and temperature stability of PEGylated gold nanoparticles. Colloid. Surf. A 2017, 523, 91-97. [CrossRef]

- Tsutsui, G.; Huang, S.; Sakaue, H.; Shingubara, S.; Takahagi, T. Well-size-controlled Colloidal Gold Nanoparticles Dispersed in Organic Solvents. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2001, 40, 346-349. [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, P.; Chaki, S.; Sen, A.; Dasgupta, S. Cataractous Eye Protein Isolate Stabilized Gold Nanoparticles Prevent Their Ethanol-Induced Aggregation. J. Phys. Chem. B 2024, 129 (7), 1934-1945. [CrossRef]

- Sen, G.T.; Ozkemahli, G.; Shahbazi, R.; Erkekoglu, P.; Ulubayram, K.; Kocer-Gumusel, B. The Effects of Polymer Coating of Gold Nanoparticles on Oxidative Stress and DNA Damage. Int. J. Toxicol. 2020, 39 (4), 328-340. [CrossRef]

- Albanese A, Chan W.C. Effect of gold nanoparticle aggregation on cell uptake and toxicity. ACS Nano 2011, 5 (7), 5478-89. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, L.; Xu, l.; Bai, R.; Ji, Y.; Wu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, C. Surface chemistry and aspect ratio mediared cellular uptake of Au nanorods. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 7606-7619. [CrossRef]

- Anniebell, S.; Gopinath, S.C.B. Polymer Conjugated Gold Nanoparticles in Biomedical Applications. Curr. Med. Chem. 2018, 25 (12), 1433-1445. [CrossRef]

- Hecold, M.; Buczkowska, R.; Mucha, A.; Grzesiak, J.; Rac-Rumijowska, O.; Teterycz, H.; Marycz, K. The Effect of PEI and PVP-Stabilized Gold Nanoparticles on Equine Platelets Activation: Potential Application in Equine Regenerative Medicine. J. Nanomater. 2017, 1, 8706921. [CrossRef]

- Retout, M.; Blond, P.; Jabin, I.; bruylants, G. Ultrastable PEGylated Calixarene-Coated Gold Nanoparticles with a Tunable Bioconjugation Density for Biosensing Applications. Bioconjugate Chem. 2021, 32 (2), 290-300. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Guo, X.; Kang, X.; Yang, H.; Guo, W.; Guan, L.; Wu, H.; Du, L. Surface Functionalization of Pegylated Gold Nanoparticles with Antioxidants Suppresses Nanoparticle-Induced Oxidative Stress and Neurotoxicity. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2020, 33 (5), 1195-1205. [CrossRef]

- Kozics, K.; Sramkova, M.; Kopecka, K.; Begerova, P.; Manova, A.; Krivosikova, Z.; Sevcikova, Z.; Liskova, A.; Rollerova, E.; Dubaj, T.; Puntes, V.; Wsolova, L.; Simon, P.; Tulinska, J.; Gabelova, A. Pharmacokinetics, Biodistribution, and Biosafety of PEGylated Gold Nanoparticles In Vivo. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1702. [CrossRef]

- Pedziwiatr-Werbicka, E.; Gorzkiewicz, M.; Horodecka, K.; Lach, D.; Barrios-Gumiel, A.; Sánchez-Nieves, J.; Gómez, R.; de la Mata, F.J.; Bryszewska, M. PEGylation of Dendronized Gold Nanoparticles Affects Their Interaction with Thrombin and siRNA. J. Phys. Chem. B 2021, 125, 1196–1206. [CrossRef]

- Soares, S.; Faria, I.; Aires, F.; Monteiro, A.; Pinto, G.; Sales, M.G.; Correa-Duarte, M.A.; Guerreiro, S.G.; Fernandes, R. Application of Gold Nanoparticles as Radiosensitizer for Metastatic Prostate Cancer Cell Lines. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4122. [CrossRef]

- Nguyenova, H.Y.; Kalbacova, M.H.; Dendisova, M.; Sikorova, M.; Jarolimkova, J.; Kolska, Z.; Ulrychova, L.; Weber, J.; Reznickova, A. Stability and biological response of PEGylated gold nanoparticles. Heliyon 2024, 10 (9). [CrossRef]

- Shan, Y.; Ma, S.; Nie, L.; Shang, X.; Hao, X.; Tang, Z.; Wang, H. Size-dependent endocytosis of single gold nanoparticles. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 8091-8093. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, L.; Xu, L.; Bai, R.; Ji, Y.; Wu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen. C. Surface chemistry and aspect ration mediated cellular uptake of Au nanorods. Biomaterials 2010, 31 (30), 7606-19. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zheng, X.; Chen, L.; Gong, X.; Yang, H.; Duan, X.; Zhu, Y. Multifunctional Gold Nanoparticles in Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment. Int. J. Nanomed. 2022, 17, 2041-2067. [CrossRef]

- Giesen, B.; Nickel, A.-C.; Barthel, J.; Kahlert, U.D.; Janiak, C. Augmented Therapeutic Potential of Glutaminase Inhibitor CB839 in Glioblastoma Stem Cells Using Gold Nanoparticle Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 295. [CrossRef]

- Kaul, M.; Sanin, A.Y.; Shi, W.; Janiak, C.; Kahlert, U.D. Nanoformulation of dasatinib cannot overcome therapy resistance of pancreatic cancer cells with low LYN kinase expression. Pharmacol. Rep. 2024, 76, 793–806. [CrossRef]

- Chechiek, V. Reduced Reactivity of Aged Au Nanoparticles in Ligand Exchange Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126 (25), 7780-7781. [CrossRef]

- Woehrle, G.H.; Brown, L.O.; Hutchison, J.E. Thiol-Functionalized, 1.5-nm Gold Nanoparticles through Ligand Exchange Reactions: Scope and Mechanism of Ligand Exchange. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127 (7), 2172-2183. [CrossRef]

- Ishida, Y.; Suzuki, J.; Akita, I.; Yonezawa, T. Ultrarapid Cationization of Gold Nanoparticles via a Single-Step Ligand Exchange Reaction. Langmuir 2018, 34 (36), 10668-10672. [CrossRef]

- Turkevich, J.; Stevenson, P.C.; Hillier, J. A study of the nucleation and growth processes in the synthesis of colloidal gold. Discuss. Faraday Soc. 1951, 11, 55-75. [CrossRef]

- Shimmin, R.G.; Schoch, A-B.; Braun, P.V. Polymer Size and Concentration Effects on the Size of Gold Nanoparticles Capped by polymeric Thiols. Langmuir 2004, 20 (13), 5613-5620. [CrossRef]

- Tomaszewska, E.; Soliwoda, K.; Kadziola, K.; Tkacz-Szczesna, B.; Celichowski, G.; Cichomski, M.; Szmaja, W.; Grobelny, J. Detection Limits of DLS and UV-Vis Spectroscopy in Characterization of Polydisperse Nanoparticles Colloids. J. Nanomater. 2013, 1, 313081. [CrossRef]

- Gharib, R.; Greige-Gerges, H.; Fourmentin, S.; Charcosset, C. Hydroxypropyl-ß-cyclodextrin as a membrane protectant during freeze-drying of hydrogenated and non-hydrogenated liposomes and molecule-in-cyclodextrin-in- liposomes: Application to trans-anethole. Food Chem. 2018, 267, 67-74. [CrossRef]

- Danaei, M.; Dehghankhold, M.; Ataei, S.; Hasanzadeh Davarani, F.; Javanmard, R.; Dokhani, A.; Khorasani, S.; Mozafari, M.R. Impact of Particle Size and Polydispersity Index on the Clinical Applications of Lipidic Nanocarrier Systems. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10 (2), 57. [CrossRef]

- Hoseini, B.; Jaafari, M.R.; Golabpour, A.; Momtazi-Borojeni, A.A.; Karimi, M.; Eslami, S. Application of ensemble machine learning approach to assess the factors affecting size and polydispersity index of liposomal nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13 (1), 18012. [CrossRef]

- Feller, D.; Otten, M.; Hildebrandt, M.; Krüsmann, M.; Bryant, G.; Karg, M. Translational and rotational diffusion coefficients of gold nanorods functionalized with a high molecular weight, thermoresponsive ligand: a depolarized dynamic light scattering study. Soft Matter 2021, 17, 4019. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Jimmy Huang, P.-J.; Servos, M.R.; Liu, J. Effects of Polyethylene Glycol on DNA Adsorption and Hybridization on Gold Nanoparticles and Graphene Oxide. Langmuir 2012, 28, 14330-14337. [CrossRef]

- Uz, M.; Bulmus, V.; Altinkaya, S.A. Effect of PEG Grafting Density and Hydrodynamic Volume on Gold Nanoparticle−Cell Interactions: An Investigation on Cell Cycle, Apoptosis, and DNA Damage. Langmuir 2016, 32, 5997-6009. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Paholak, H.; Ito, M.; Sansanaphongpricha, K.; Qian, W.; Che, Y.; Sun, D. ‘Living’ PEGylation on gold nanoparticles to optimize cancer cell uptake by controlling targeting ligand and charge densities. Nanotechnology 2013, 24, 355101. [CrossRef]

- Mohsen-Nia, M.; Amiri, H.; Jazi, B. Dielectric Constants of Water, Methanol, Ethanol, Butanol and Acetone: Measurement and Computational Study. J. Solution Chem. 2010, 39, 701-708. [CrossRef]

- Tseng, K.-H.; Liao, C.-Y.; Huang, J.-C.; Tien, D.-C.; Tsung, T.-T. Characterization of gold nanoparticles in organic or inorganic medium (ethanol/water) fabricated by spark discharge method. Mater. Lett. 2008, 62 (19), 3341-3344. [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, W.; Xu, L.; Ge, C.; Liu, J.; Gu, N. Linear aggregation of gold nanoparticles in ethanol. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochem. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2003, 223 (1-3), 177-183. [CrossRef]

- Tilaki, R.M.; Iraji zad, A.; Mahdavi, S.M. The effect of liquid environment on size and aggregation of gold nanoparticles prepared by pulsed laser ablation. J. Nanopart. Res. 2007, 9, 853-860. [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Huang, W.M.; Fu, Y.Q.; Leng, J. Quantitative separation of the influence of hydrogen bonding of ethanol-water mixture on the shape recovery behavior of polyurethane shape memory polymer. Smart Mater. Struct. 2014, 23, 125041. [CrossRef]

- Jewrajka, S.K.; Chatterjee, U. Block copolymer mediated synthesis of amphiphilic gold nanoparticles in water and an aqueous tetrahydrofuran medium: An approach for the preparation of polymer–gold nanocomposites. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 2006, 44 (6), 1841-1854. [CrossRef]

- Mani, S.; Khabaz, F.; Godbole, R.V.; Hedden, R.C.; Khare, R. Structure and Hydrogen Bonding of Water in Polyacrylate Gels: Effects of Polymer Hydrophilicity and Water Concentration. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2015, 119 (49), 15381-15393. [CrossRef]

- Galanis, E.; Anderson, S.K., Twohy, E.L.; Carrero, X.W.; Dixon, J.G.; Tran, D.D.; Jeyapalan, S.A.; Anderson, D.M.; Kaufmann, T.J.; Feathers, R.W.; Giannini, C.; Buckner, J.C.; Anastasiadis, P.Z.; Schiff, D. A phase 1 and randomized, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial of bevacizumab plus dasatinib in patients with recurrent glioblastoma: Alliance/North Central Cancer Treatment Group N0872. Cancer 2019, 125 (21), 3790-3800. [CrossRef]

- Gnoni, A.; Marech, I.; Silvestris, N.; Vacca, A.; Lorusso, V. Dasatinib: an anti-tumour agent via Src inhibition. Curr. Drug Targets 2011, 12, 563-578. [CrossRef]

- Usama, S.M.; Jiang, Z.; Pflug, K.; Sitcheran, R.; Burgess, K. Conjugation of Dasatinib with MHI-148 Has a Significant Advantageous Effect in Viability Assays for Glioblastoma Cells. ChemMedChem 2019, 14 (17), 1575-1579. [CrossRef]

- Dumont, R.A.; Hildebrandt, I.; Su, H.; Haubner, R.; Reischl, G.; Czernin, J.G.; Mischel, P.S.; Weber, W.A. Noninvasive imaging of alphaVbeta3 function as a predictor of the antimigratory and antiproliferative effects of dasatinib. Cancer Res. 2009, 69 (7), 3173-3179. [CrossRef]

- de Groot, J.; Milano, V. Improving the prognosis for patients with glioblastoma: the rationale for targeting Src. J. Neurooncol. 2009, 95 (2), 151-163. [CrossRef]

- Teng, T.; Cai, Y.; Pi, W.; Gao, L.; Shay, C. Augmentation of the anticancer activity of CYT997 in human prostate cancer by inhibiting Src activity. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2017, 10 (1), 118. [CrossRef]

- Rice, L.; Lepler, S.; Pampo, C.; Siemann, D.W. Impact of the SRC inhibitor dasatinib on the metastatic phenotype of human prostate cancer cells. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 2012, 29 (2), 133-142. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).