1. Introduction

The mining industry accounts for 4.2% of Brazil's GDP, according to the PNM (National Mining Plan). In order to be exported or even absorbed by the domestic industry, minerals must undergo treatment or beneficiation processes, which consist of several unit operations and, finally, the disposal of tailings (ANM, 2023).

The final disposal of tailings has become an increasingly significant global challenge, as the most common methods—such as dams or piles—require vast land areas. This can conflict with land use and occupation issues, especially environmental concerns. Moreover, when these structures are built improperly, they pose serious risks to society, the environment, and the economy, as seen in the tailings dam disasters in Mariana and Brumadinho, in the state of Minas Gerais, in 2015 and 2019, respectively.

New methodologies must be employed for tailings disposal, either by improving the beneficiation efficiency to generate less waste, or by developing new, safer technologies for disposing of this material, or even giving these materials an alternative use.

The reuse of tailings as construction material has been frequently studied in recent years; however, the mechanical properties of tailings are often not suitable for engineering purposes, so it is necessary to improve those properties. One efficient way of improving the properties of soils — and can be applied to tailings — is the incorporation of stabilizing agents. The most common agents applied in the stabilization technique are cement, lime, fly ashes, asphalt emulsion, and residue from construction and demolition, according to Ferreira et al. (2021).

Recently, a few researchers started studying the use of polymers to stabilize soils and tailings, such as Carneiro et al. (2020), Alelvan et al. (2022), and Boaventura et al. (2023). All three studies demonstrated that the use of polymers as a physical-mechanical stabilizing agent may be viable, with great improvement in the material's resistance.

As highlighted in the literature, compressive strength and indirect tensile strength are the primary parameters used to evaluate the mechanical behavior of soil-cement mixtures. In this context, two key factors play a fundamental role in understanding strength development: the void ratio, expressed through porosity (η, Equation (1)), and the volumetric cement content (

Civ, Equation (2)). These parameters form the basis of the conceptual framework proposed by Consoli et al. (2007) for analyzing cement-stabilized soils,

where C is the cement amount in the mass of dry soil;

is the specific mas of the sample;

is the density of the cement agent;

is the dry unit mass of soil grains and

is the total volume of the sample.

To evaluate the influence of the cementing agent content on a single index, a new index called volumetric cement content (

), was proposed, as follows:

where

is the cement agent volume;

is the total volume of the sample;

is the cement agent mass and

is the density of the cement agent.

The general equation for both compressive and tensile strengths associate

η/

with the curing time (

), and the β and B adjustment exponents (Equation (3)).

While many studies have explored the mechanical behavior of ore tailings, fully understanding these materials remains a significant challenge. There is still a considerable knowledge gap regarding how tailings interact with chemical stabilizers—an understanding that is essential for their safe and effective use in civil construction.

To bridge this gap, microstructural analysis offers valuable support. These techniques allow researchers to investigate the internal behavior of tailings in a non-invasive and non-destructive manner. Moreover, they require only small sample sizes and yield insights that are critical for validating theories and advancing knowledge in tailings mechanics (Alelvan et al., 2022).

With all of this in mind, the present study aims to evaluate the effects of incorporating an acrylic-styrene copolymer into ultrafine iron ore tailings, with a focus on identifying the optimal polymer dosage that enhances the material’s physical and mechanical properties. The research also seeks to perform a comprehensive chemical, geological, and mineralogical analysis to support a deeper understanding of tailings stabilization processes. Additionally, a dosage study will be proposed to establish a mathematical correlation between polymer content and key physical and mechanical parameters of the composite. Finally, microstructural investigations using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and X-ray microtomography will be conducted to examine the interactions between tailings particles and the polymer.

2. Materials and Methods

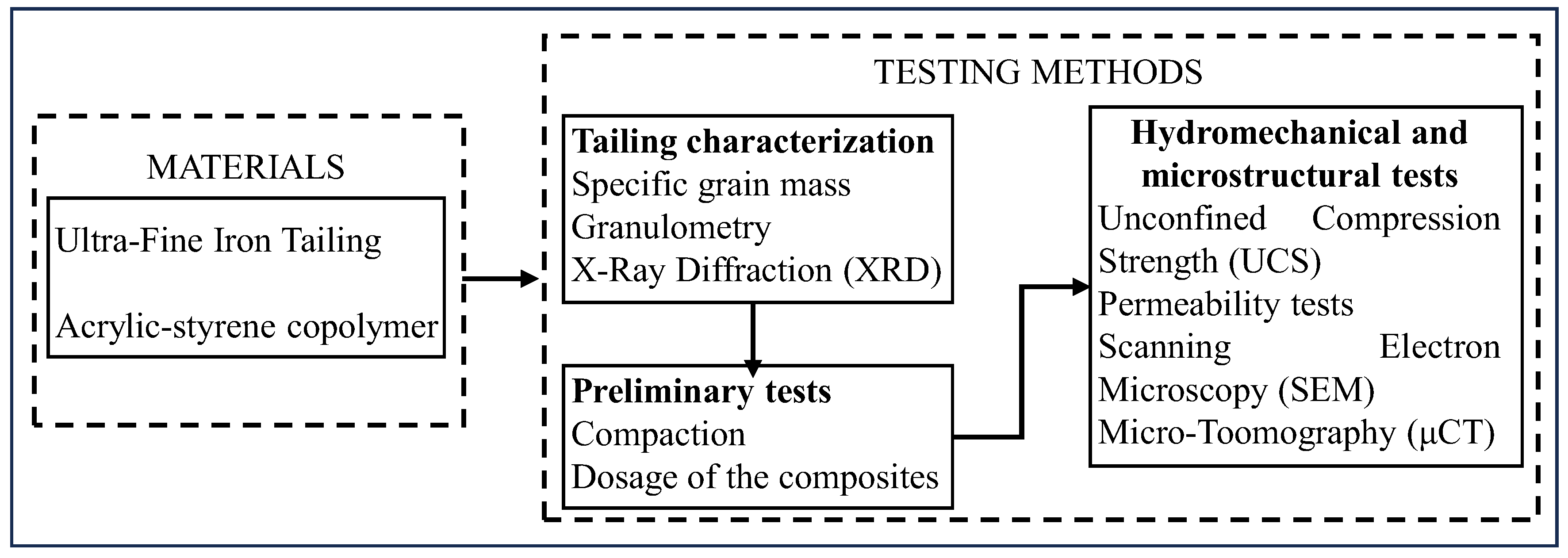

Figure 1 shows the flowchart of the materials selection and the sequential methods applied to the research.

2.1. Materials

The ultrafine iron tailing (

Figure 2a) originates from the Maravilhas II dam mine, located at Mina do Pico in the city of Itabirito, Minas Gerais. This mine is one of the main dams in the Complex; it is of the downstream type, implemented in 1994, holds a volume of 94 million cubic meters, is 97.9 meters high, and currently has 109 monitoring instruments (CMBH, 2019).

The polymer stabilizer used in this work (

Figure 2b) was provided by a supplier. It consists of an organic acrylic-styrene copolymer and is presented in the form of an aqueous emulsion of anionic character. It has a pH of 8.0–9.0, density of 0.98–1.04 g/cm

3, and viscosity of 3.000-10.000 centipoise (cP). In addition, it is completely soluble in water.

2.2. Characterization of the Tailing

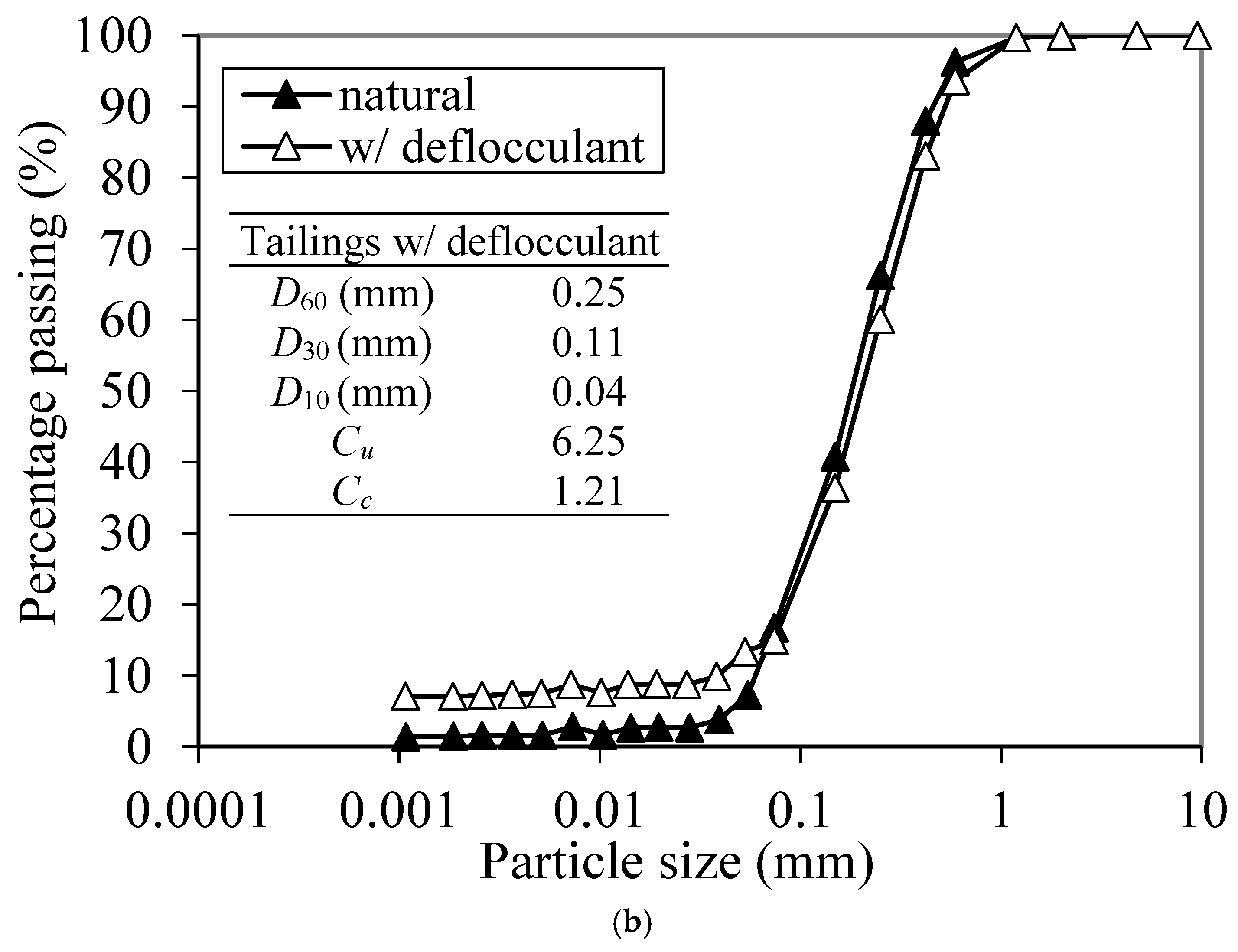

The determination of the specific grain mass was carried out using the pentapycnometer equipment model Pentapyc 5200e as established by ASTM D5550 (2014). The granulometric distribution curve was carried out following ASTM D7928 (2021) and D6913 (2017), with and without deflocculant, since there is no specific standard for tailings. Despite this, it is considered a good approach to carry out this type of test to classify the particle size of tailings particles.

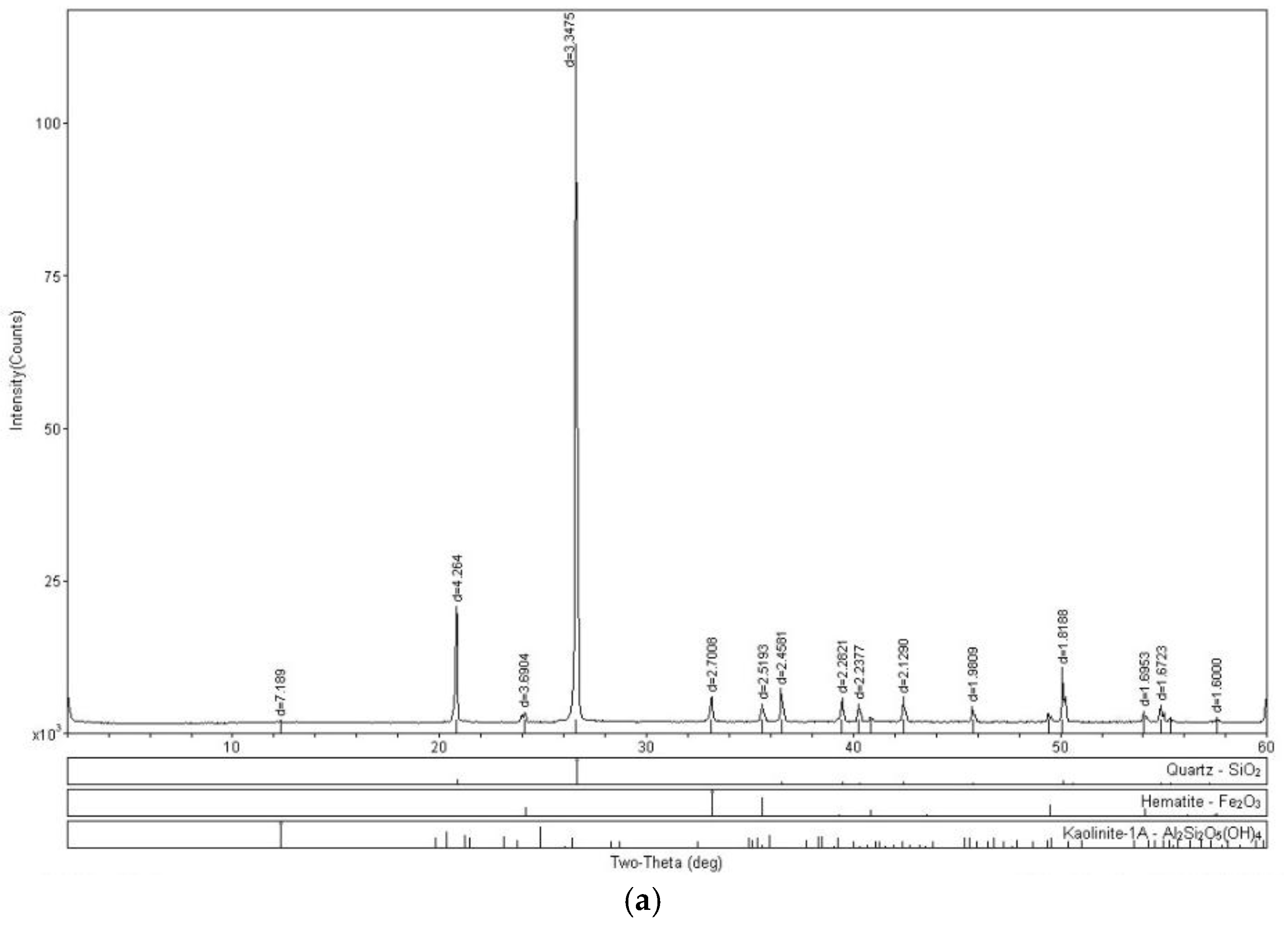

The X-ray Diffraction (XRD) tests were carried out to identify the crystalline structure present in pure tailing from a sample passing through 75 μm sieve and dried in an oven at 105°C. The analysis was carried out on a Rigaku diffractometer, under a voltage of 35 kV and 15 mA, an angular amplitude of 2θ, a measurement range between 2-100°, and a speed of 0.05°/min. Mineralogical identification was carried out using the reference standards of the JADE 9.0 software database. Tests in the tailing-polymer composite were not performed since the polymer is organic and does not present a crystalline structure.

2.3. Compaction Tests

Proctor compaction tests under standard effort (600 kJ/m

3) were carried out according to ASTM D698-12 (2021). During this experimental phase, it was noticed that the addition of water generates a type of mud that harms and hinders the workability of the pure tailing. Consequently, the moistened tailing leaks through the spaces between the spacer disc and the mold, preventing the adoption of the standard procedure as per the norm, highlighting the challenge of using the methodological framework of soil mechanics for tailings mechanics. On top of that, water increments in the tailings affected the structure generated by the process (

Figure 3).

The tailing was statically compacted in three layers, with slightly scarification from the previous layer and Mini-MCT compaction tests following DNER-ME 228/94 (DNER, 1994) for iron tailings and tailing-polymer composites.

2.4. Dosage Tests of Tailing-Polymer Composite

The determination of polymer content for the ultrafine iron tailing from the point of view of mechanical behavior, tailing-polymer composite samples were molded in distinct dosages of polymer, namely: 10%, 20%, 30%, 40%, 50% and 60%. From a moisture content value of 15% and an initial dry density of 1.91 g/cm

3, the percentages of polymer were calculated from the percentage of water added to the tailing; therefore, the actual percentage of polymer added to the composite was calculated proportionally to the 15% moisture content. The experimental conditions investigated, polymer effective percentages, and abbreviations used here are given in

Table 1.

Samples measuring 100 mm height and 50 mm diameter were molded, in triplicate, for each experimental condition. The composites were air cured for 14 days before the unconfined compressive strength (UCS) tests, based on previous works (Boaventura et al.,2023; Carneiro et al., 2020; Alelvan et al., 2022). The curing period for dosage was established taking into account that resistance gains are typically observed after 14 days.

2.5. Unconfined Compressive Strength tests

From the dosage tests, the concentrations of 30% and 40% were identified as more effective for the mechanical tests. To expand the understanding of the behavior of tailing-polymer, keeping the content fixed, the composites' dry densities were varied by 1.91, 1.96, and 2.01 g/cm3. Then, samples in triplicate with 100 mm height and 50 mm diameter for pure tailing and the tailing-polymer composite were molded and air cured for 28 days. The curing period was established considering that most reactions occur within this period; longer periods present minimal impact on strength gains, as seen from Boaventura et al. (2023). After that, the mechanical behavior from UCS tests was carried to ASTM D 2166 (2024).

The tests occurred under a controlled deformation of 1.27 mm/min up to 10% of deformation. As an acceptance criterion for UCS tests, it was established that the strength of the replicates, molded with the same characteristics, should not deviate more than 10% from the average strength.

2.6. Permeability tests

The evaluation of hydraulic behavior is essential in chemical stabilization studies with tailings for geotechnical purposes, since there may be the presence of heavy metals in the material. Additionally, to mechanical behavior, it is fundamental that the proposed solution retains or minimizes the potential for leaching if any of these elements are present.

Thus, permeability tests were carried out for pure tailings and 40% polymer-stabilized tailings for a dry density of 1.91, 1.96, and 2.01 g/cm3 and a curing time of 28 days to evaluate the influence of the polymer and the density on the permeability coefficient. Permeability tests were conducted using the falling-head method based on ASTM D5084-16a (2016). Water flowed through the specimen from a standpipe. Following specimen saturation over two days, the reservoir was filled, and water discharge was initiated. Water column height was measured at intervals of over 24 hours, with a total of 14 readings per specimen to obtain a representative average coefficient of permeability (k) for each experimental condition.

2.7. Microstructural tests

The microstructure of the pure tailing and tailing-polymer composites was assessed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and X-ray micro-tomography (μCT) tests. SEM was performed using a JEOL JSM-7001F microscope, which has a field emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM) with a hot electron gun (Schottky) optimized for analytical applications. Tests were operated under an acceleration voltage of 5 kV. Both pure tailing and composite were evaluated by cylindrical specimens with 30 mm height and 15 mm diameter. The ultrafine iron tailing sample was prepared by passing through 75 μm sieve and dried in an oven at 105°C for 24 hours before analysis. For the analysis of the tailing-polymer composite, a compacted cylinder 30 mm high and 15 mm in diameter was prepared.

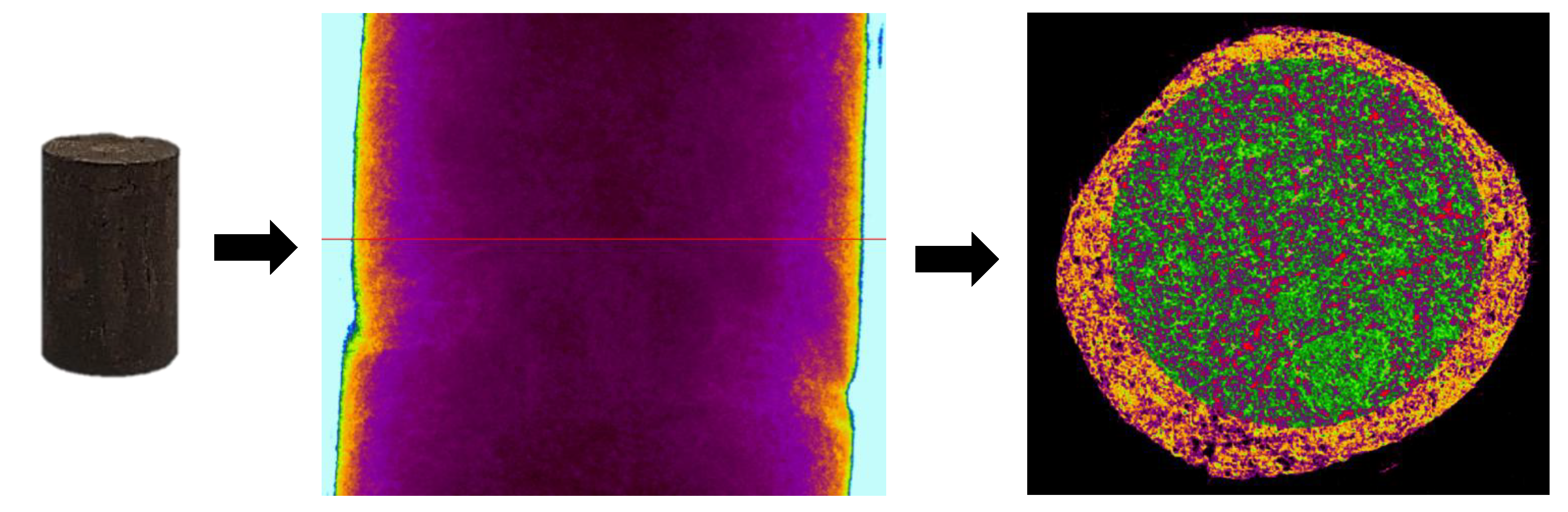

X-Ray micro-tomography (μCT) analysis is a powerful microstructural technique to seek the effect of the polymer in the tailing matrix and the three-dimensional model of the composite. The experimental conditions evaluated in the test were pure tailing and tailing stabilized with 40% polymer, both at 1.91 g/cm

3 dry density, with 30 mm height and 15 mm in diameter. To discount edge effects, data acquisition was performed in a volume of interest (VOI) measuring 12.5 mm in diameter by 12.5 cm in height (

Figure 4).

The cylindrical samples were analyzed at a Bruker SkyScan 1172 MicroCT system throughout 666 images. They were obtained with 3150 ms exposure time using an aluminum filter of 0.5 mm. They had an imaging resolution of 4.96 μm, with a voltage and electric current of 70 kV and 129 μA for all investigated materials. The reconstruction of the three-dimensional model was performed in the NRecon software.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Ultrafine Iron Tailings Characterization

Figure 5a presents the mineral composition of ultrafine iron ore tailings. The result shows that the iron tailing studied is predominantly composed of quartz [SiO

2], hematite [Fe

2O

3], and kaolinite [Al

2Si

2O

5(OH)

4]. These results are similar to others carried out in distinct iron ore tailings such as Santos et al. (2018) and Carneiro et al. (2020). The tailings specific gravity is 3.23 g/cm

3, the value is slightly higher from the literature since the present material is ultrafine, which leads to a greater quantity of physically heavy mineral particles, such as hematite, by volume when compared to the others works (Santos et al., 2018, Carneiro et al., 2020, Sotomayor et al., 2024).

Figure 5b presents the granulometric analysis of the material. It is possible to note that the iron tailing is mostly composed of sand fraction size, 92.7%, although the material under study is an iron tailing and does not behave as a soil.

3.2. Compaction

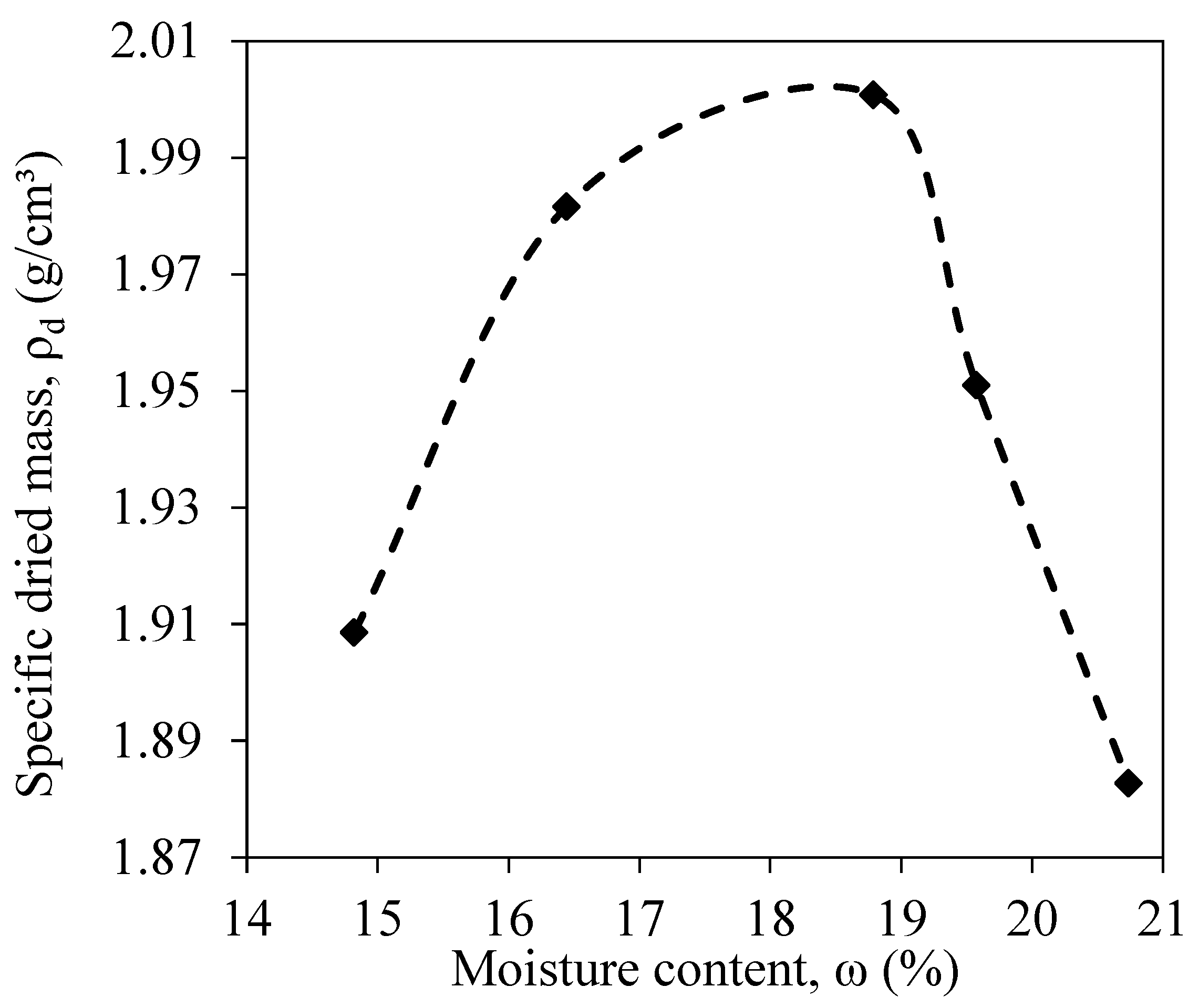

Figure 6 shows the results of the compaction tests. As previously stated, the behavior of the tailing in contact with water in the compaction tests did not follow the traditional trend. The maximum dry unit mass obtained was 2.0 g/cm

3 with an optimum moisture content of approximately 19%. It is important to point out that the values cannot be considered valid, since the higher the moisture content added to the samples, the more they lose material, thereby compromising the structural integrity of the material.

Analyzing the curve, it is possible to notice that the parameters diverge from a curve predominantly composed of sandy soil, mainly related to a low optimum moisture value, which reinforces the challenges of working with tailings using soil methodologies, emphasizing the importance of adapting procedures to develop the area of tailings mechanics. The basis explanation for the divergence between the granulometry and compaction results is that the iron tailing did not undergo the weathering processes that Brazilian tropical soils usually do, the iron tailing is a byproduct of the waste processing process that goes through physical processes and significant chemicals that can alter the behavior of the material (Coelho et al., 2024).

The behavior identified during compaction points out the challenge of using this type of tailing in its natural state, motivating the present stabilization study using polymer. So, a moisture content value of 15% and an initial dry density of 1.91 g/cm3 were set, which was the level that remained more stable and was possible to perform the tests.

3.3. Dosage Tests of Tailing-Polymer Composite

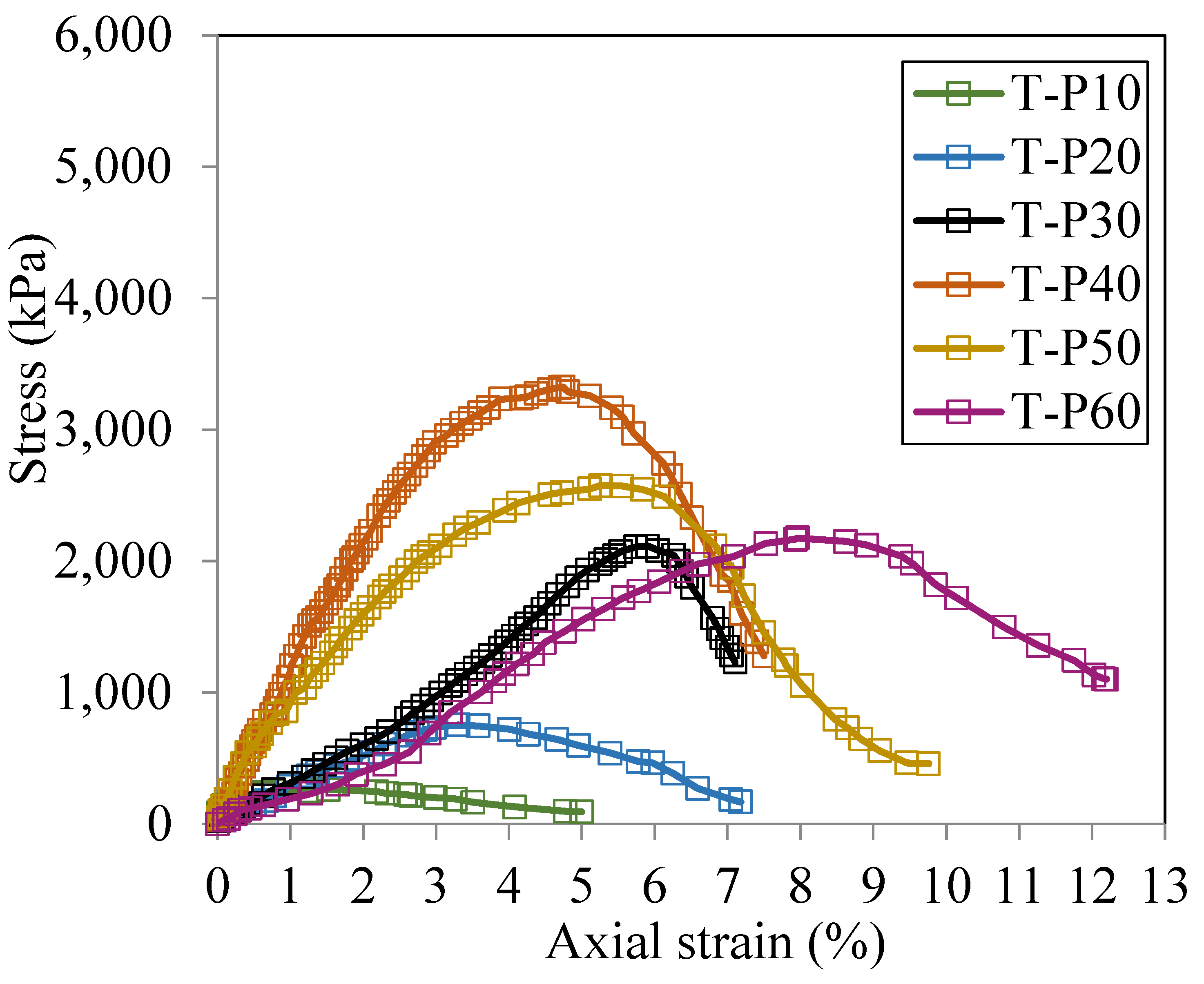

Figure 7 shows the results of unconfined compression tests for distinct polymer dosages under air curing process for 14 days. From the stress-strain curves, it can be noted that the addition of polymer improves the compressive strength of the tailing. The gains increase with the addition of polymer by up to 40%, after which, the compressive strength peaks tend to present smaller magnitudes. It is important to note that compacted pure tailing exhibited a stress peak of 49 kPa under 0.05% axial strain, which was not plotted due to the scale magnitude.

The results demonstrated the satisfactory physical-chemical interaction of the ultrafine iron tailing with the polymer, which is seen by the greater bearing capacity of the composites. In addition to a significant gain in the material's peak resistance, it showed satisfactory ductility when compared to other tailing-polymer composites, considering that the peak occurred at axial strain from 4% to 8%, while those studied by Carneiro et al. (2020) and Alelvan et al. (2022) presented their peaks at 1-4% axial strain. After the peak, an abrupt drop in strength is observed, indicating that the polymer stabilizing the tailings is not effective in post-peak resistance.

Considering that the polymer acts as a glue effect joining the particles, once the peak is reached, it is expected that this cementing effect will break (Alelvan et al., 2022). If post-peak resistance is an important factor in design, studies such as Festugato et al. (2015), Consoli et al. (2017), Sotomayor et al. (2024) inserted fiber in stabilized tailings to ensure better distribution of stresses and reduce the drastic post-peak drop.

Table 2 shows the peak stress values for each composite as well as the percentage of resistance gain compared to the compacted pure tailing. From the results, it is evident the optimum dosage content at 40% of the polymer solution. Nevertheless, composites with 30% polymer also exhibited satisfactory results and represent a less costly solution, thereby justifying the study of both concentrations. It is important to point out that particle shape and size, mineralogical composition, affect the optimum polymeric content, as indicated by (Boaventura et al., 2023; Alelvan et al., 2022).

3.4. UCS

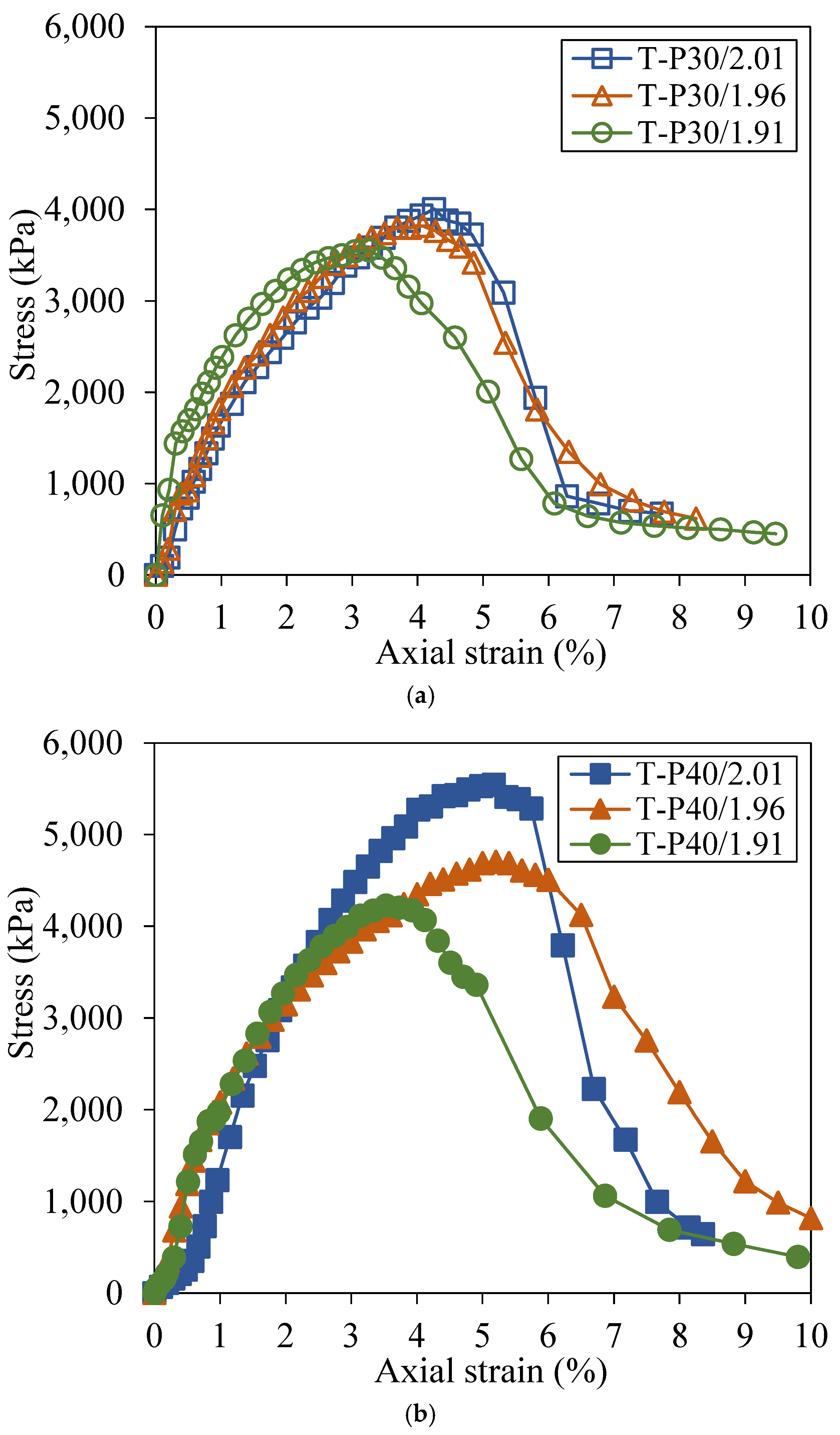

From the stress-strain curves of tailings stabilized with 30% (

Figure 8a) and 40% polymer (

Figure 8b), it is seen that both polymer content and dry density affected the mechanical behavior of the material.

The increase in density from 1.91 to 1.96 and 2.01 g/cm3 positively influenced the peak resistances presented by both contents, improving in T-P30 from 3,659 kPa to 3,818 kPa and 4,008 kPa, respectively. Considering T-P40 composites, values increased from 4,226 kPa (T-P40-1.91) to 4,707 kPa (T-P40-1.96) and 5,547 kPa (T-P40-2.01). Still, comparing the effects of increasing the polymer content (Table 2) with increasing the dry density, the first has a more pronounced effect on the mechanical behavior of the composite.

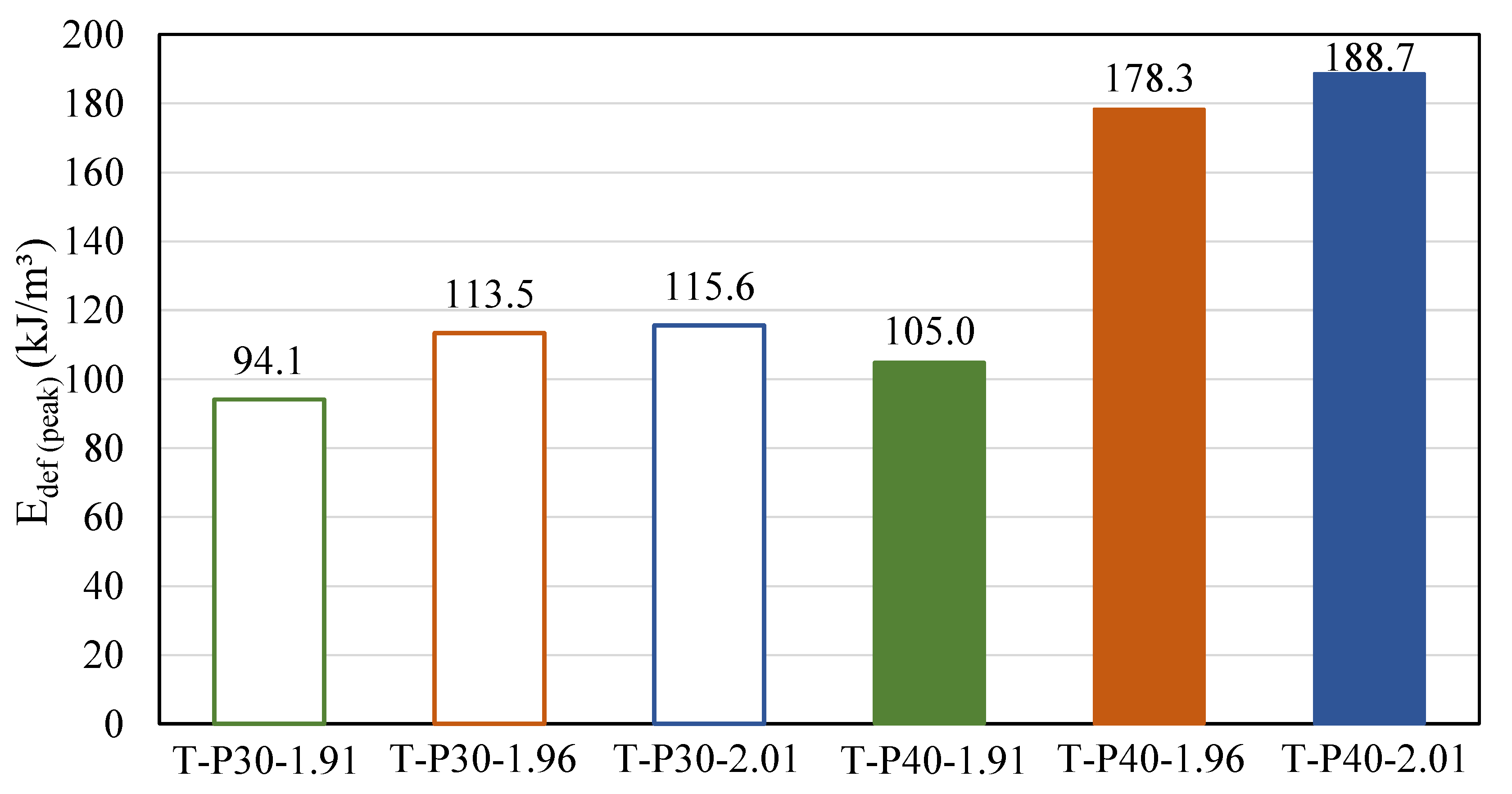

To highlight the effect of the polymer on mechanical behavior of tailings, the tenacity of the composites was assessed by the strain energy absorption capacity (ε

def), which is a quantity numerically equal to the area under the stress

vs. axial strain curve, evaluated up to the peak strength (

Figure 9). It is shown that the greater the amount of polymer in the composite, the greater the material's ability to absorb energy up to peak strength, which is in agreement with Alelvan et al., 2022. Particularly regarding dry densities, it is observed that the increase from 1.91 to 1.96 yields considerable gains, i.e., 20.6% and 69.9% for T-P30 and T-P40, respectively. However, the increase from 1.96 to 2.01 does not result in significant magnitudes of improvement.

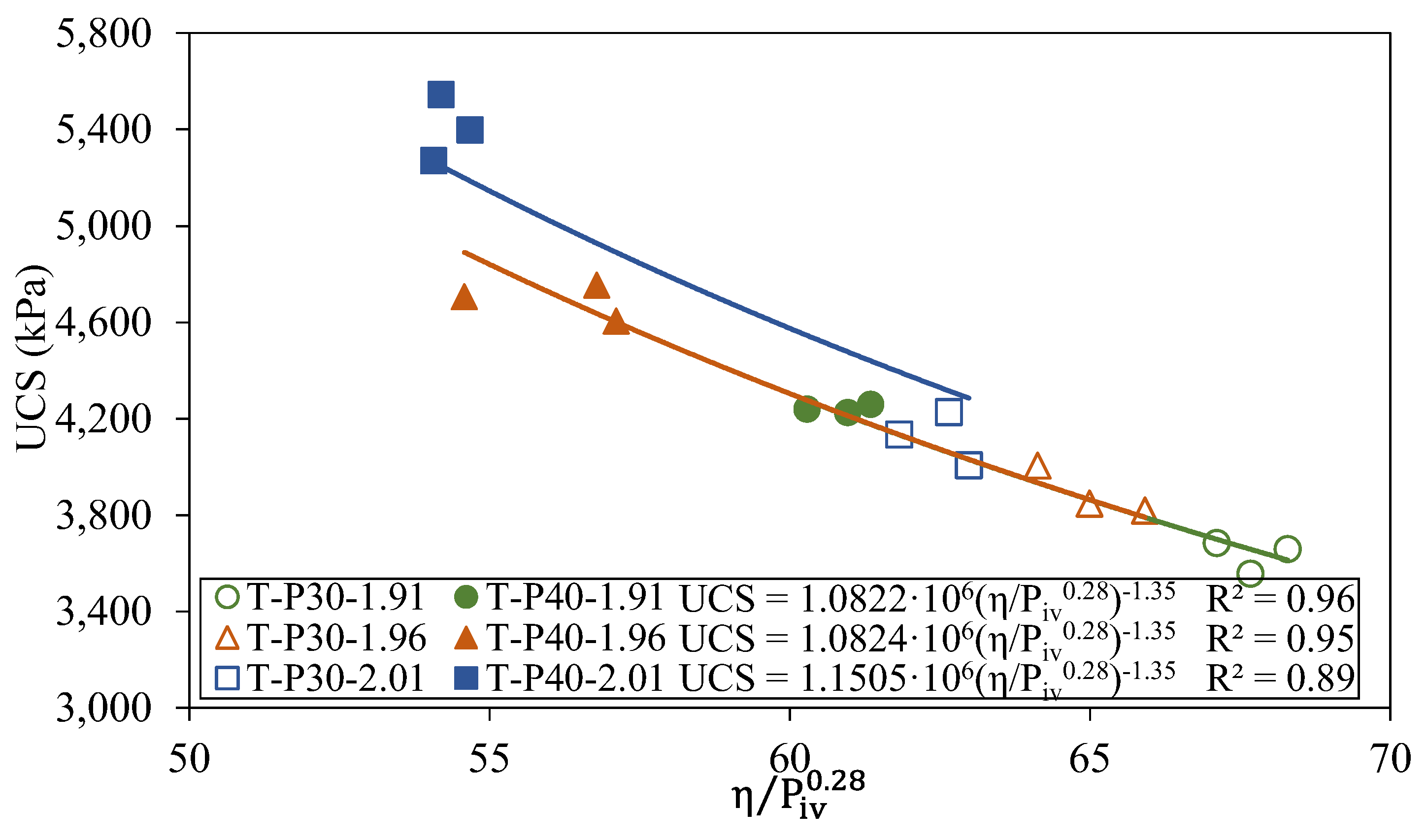

Based on Equations (1) and (2), the unconfined compressive strength of tailings-polymer composites as a function of porosity/volumetric polymer content index (η/P

iv) are demonstrated in

Figure 10. Overall, the results demonstrate that lower porosity of the composite corresponds to higher UCS. In particular, it is important to highlight that grouping the results by the dry mass of the composites leads to an overlap of the trend curves, showing that identical resistance values can be achieved either by increasing the polymeric solution or by increasing the density.

From mathematical adjustments, an external exponent equals to 0.28 was applied in Piv to fit the data accordingly. The external exponent value used was identical to that of Consoli et al. (2007, 2020a) and Scheuermann Filho (2024) using lime, cement fly ash to stabilize residual soil. As the external exponent expresses the relative importance of the porosity and the amount of polymeric solution, as noted by Consoli et al. (2020b), the adjustment indicates that porosity remains as the main factor in the strength of the mixtures regardless of whether the matrix is soil or tailings.

By fitting results in a power function, satisfactory correlations were obtained (R2 ≥ 0.90), in which A and -B are scalars related to matrix characteristics, nature of the stabilizing agent, and the first is also strongly associated with the curing time.

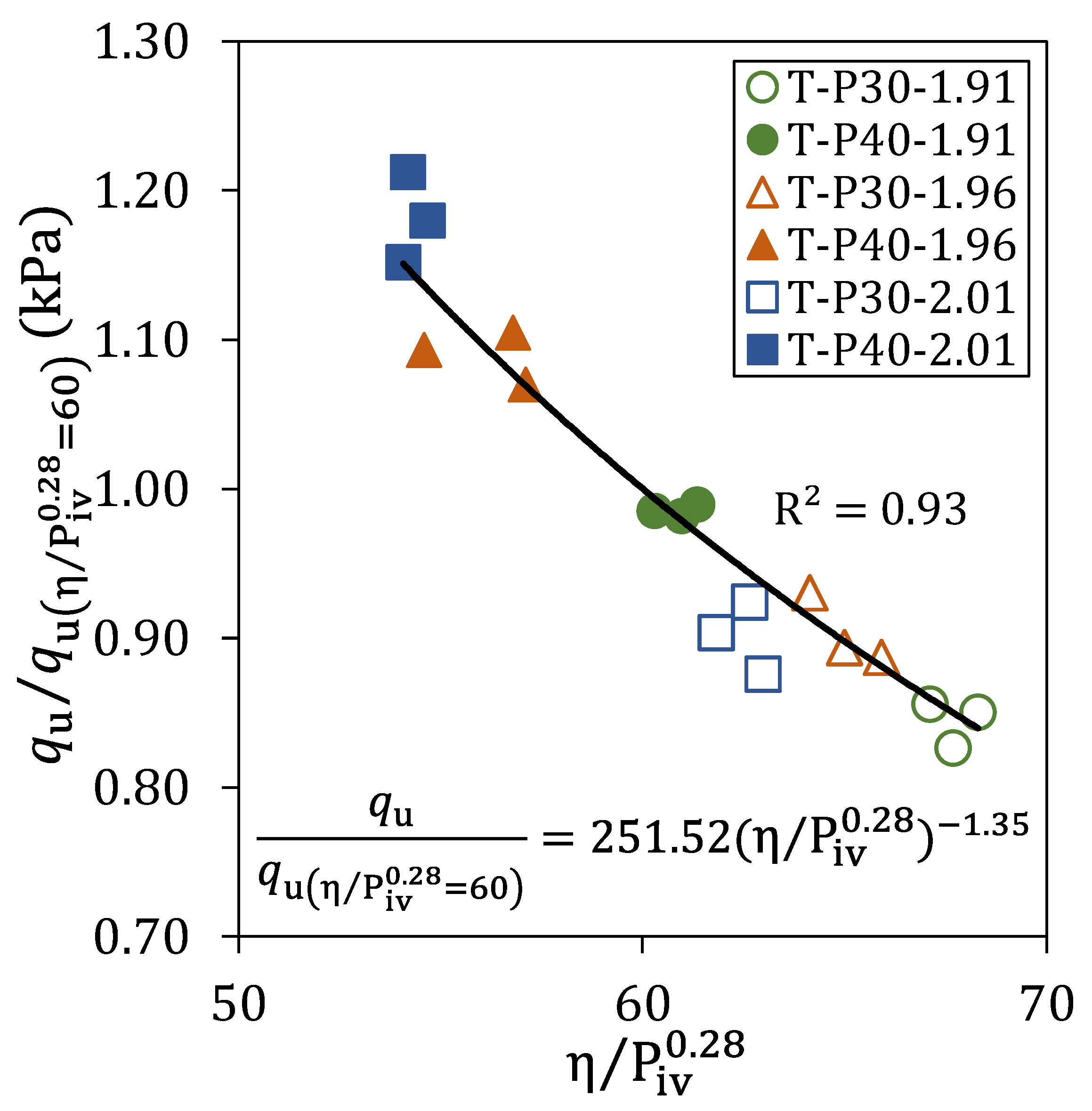

Lastly, data normalization of compressive strength is proposed in

Figure 11 by dividing both left and right sides of the equations controlling the mechanical behavior from q

u of η/P

iv equals to 57 (Equation (3)), an intermediate value within the range from 50 to 65 of this study. Additional details of the mathematical normalization process can be found in the relevant literature (Ferreira et al., 2021; Alelvan et al., 2022; Scheuermann Filho, 2024).

From this analytical approach is possible to determine the required resistance from a single equation using just one experimental test with a molded sample of a specific polymer quantity and density, in a particular porosity. Thus, saving time and materials, and making the analysis more efficient. It is important to clarify that the investigation of mechanical behavior is restricted to the scope of the experimental program.

3.5. Permeability

The permeability coefficient obtained for the pure tailings and tailing composites with 40% polymer is shown in Table 3

Overall, no significant change in k was observed between the pure and stabilized tailings, maintaining the order of magnitude practically constant across all experimental conditions investigated (10^ (- 6) cm/s). For identical dry densities, the addition of polymer slightly reduces the permeability coefficient due to the agglomeration effect among the ultrafine tailings’ particles. Nevertheless, the amount of polymer used is insufficient to induce significant changes in permeability property, unlike the effects observed in mechanical behavior.

3.6. Microstructure

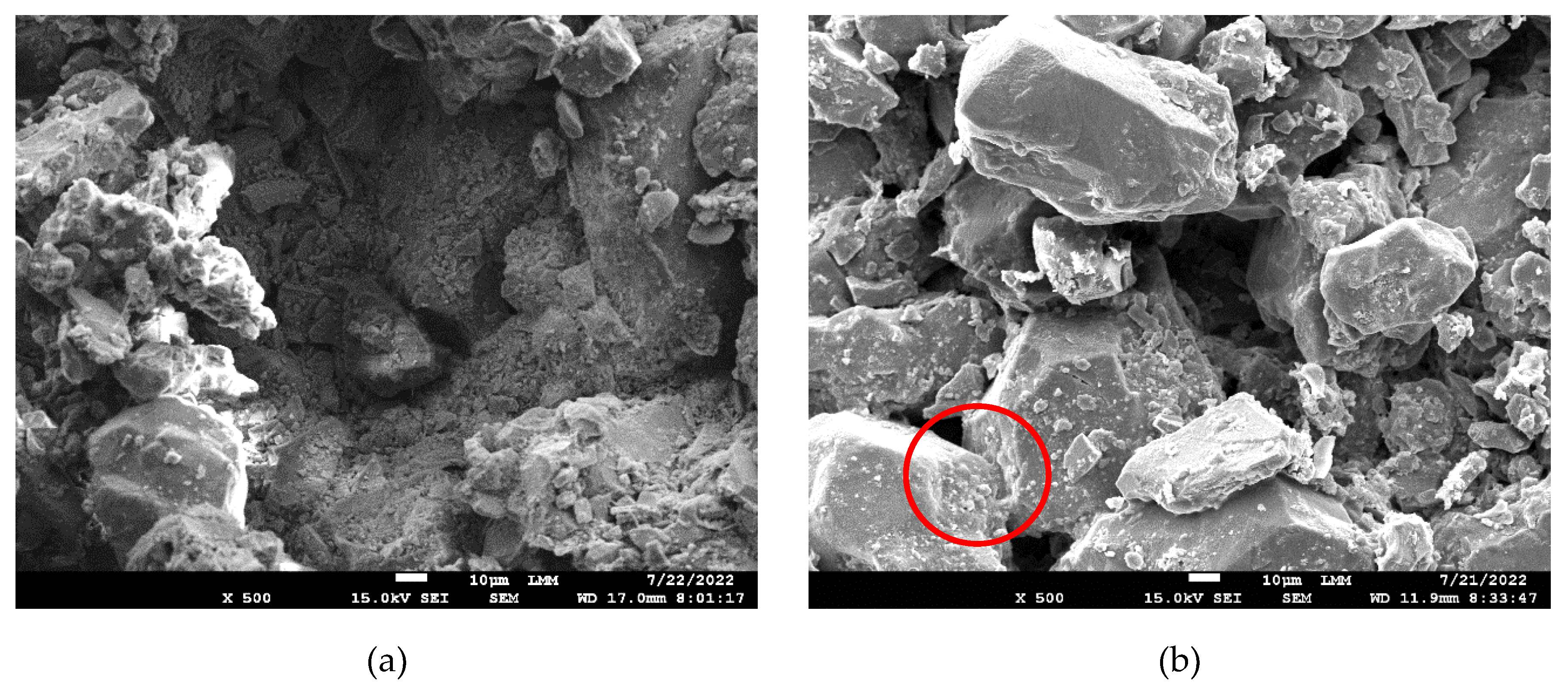

Figure 12 shows the SEM images of pure tailing and the composites T-P40-1.91, T-P40-1.96, T-P40-2.01 magnified at 500x. Ultrafine iron tailings particles present varied particle sizes with an emphasis on their angular shape, corroborating the result of the granulometric analysis. On the other hand, the addition of polymer improves the homogeneity in the distribution of particles along the investigated surface.

Considering that both pure tailing and T-P40-1.91 exhibit the same density and, consequently, porosity, the SEM images (

Figure 12a,b) reveal a difference in the size of the voids. Unlike cement, where reactions fill the spaces (Milani et al., 2022), it is hypothesized that polymer stabilization alone does not fill these voids. Instead, its effect lies in the agglutination of the particles, which reduces the size of the macropores and increases their relative frequency. Consequently, there is an increase in the contact points between the particles, leading to improved load distribution when stressed, as evidenced by the obtained mechanical properties.

Regarding the increase in the density in composites of tailings stabilized with 40% polymer, it is clear that higher densities bring the particles closer together and, consequently, enhance the binding effect of the polymer. This phenomenon is evident in the T-P40-2.01 composite (

Figure 12d), where a substantial area exhibiting this effect can be delimited.

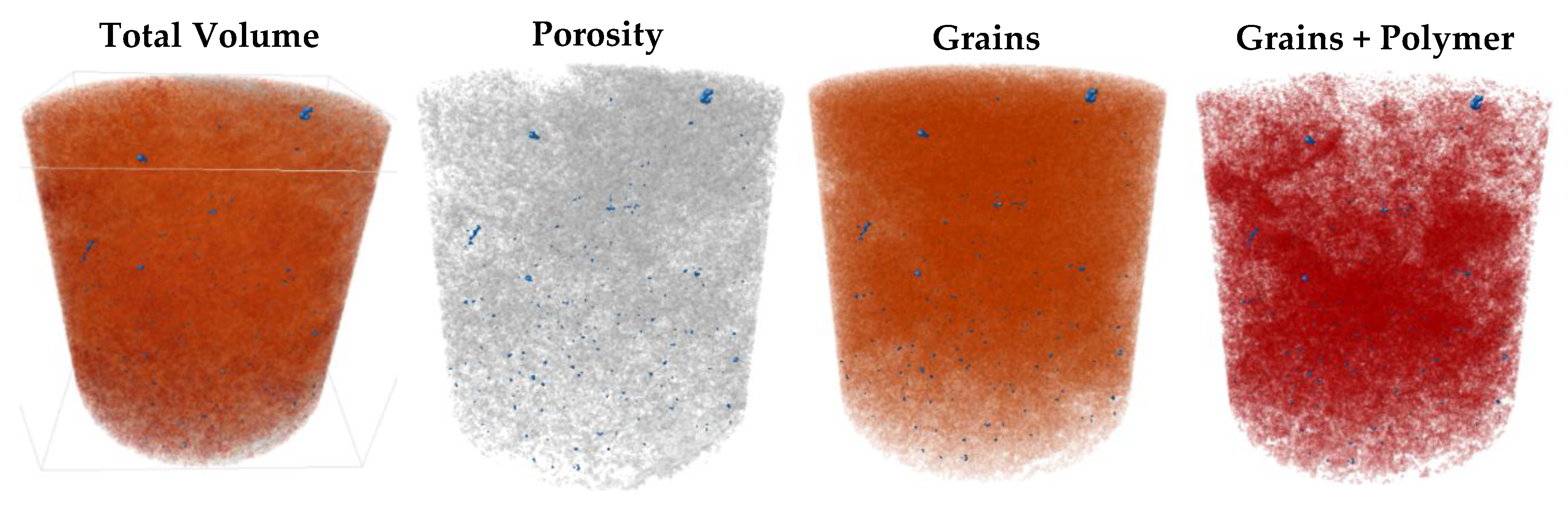

Microtomography analysis brought the possibility of evaluating the behavior and structure of the composite from several aspects. The two-dimensional images generated for the Pure Tailing and Tailing + 40% Polymer samples are shown in

Figure 13a,c. It is possible to observe the effect on the samples. In the regions closest to the mold, there is a lower density, represented by the colors blue, green, and yellow, and as it approaches the center, a greater density and greater homogeneity are presented by purple.

In

Figure 13b,d the sections of interest for each sample analyzed are represented. They are generated to determine the region of the samples in which the microtomographic analyses will be carried out. The sections of interest presented correspond to the section area for the red line shown in images (a) and (b) of

Figure 13. In them, the edges of the sample are eliminated to make an analysis of the region more homogeneous, the part represented in yellow in these figures is eliminated from the analysis, and then this section is applied throughout the entire specimen.

Figure 14 presents the Pure Tailing sample three-dimensional analysis, representing the total volume of the specimen, the porosity, the tailing grains, and the heaviest minerals (in blue). This discrimination was made based on the decomposition of the histogram generated by the passage of the X-ray through the samples.

Figure 15 shows the Tailing + 40% Polymer sample three-dimensional analysis, which has a new category represented, which is believed to be formed by the union of tailing grains with the polymer, as this has a higher density detected in the histogram.

Table 4 shows the percentages of each category taken from the histogram for the two samples analyzed. Notably, the porosity in percentage shows a decrease of 1.78% for the sample with the addition of 40% polymer compared to the sample of pure tailing, again showing that the polymer can close some pores in the composite structure.

Conclusions

This research conducted initial studies to evaluate the physicochemical, mechanical, mineralogical, and microstructural behavior of an ultrafine iron ore tailing chemically stabilized with an acrylic-styrene copolymer. The following conclusions can be drawn:

Although the composition of this tailing is mainly based on quartz particles and the granulometric analysis tends to classify this material as sand, its behavior is far distant from a sandy soil or even from soil at all.

The addition of a polymer to stabilize the tailing in the study was essential. After some tests, it was established that the best relative percentages of polymer added to the tailing were 30% and 40%.

From the UCS tests, it is seen that both polymer content and dry density affected the mechanical behavior of the material. The increase in density increases the strength of the material, while the increase of polymer increases the strength up to 40%, after that it decreases.

The UCS tests showed that the greater the amount of polymer in the composite, the greater the material's ability to absorb energy up to peak strength.

The porosity/cement ratio proved to be a useful tool for normalizing the compressive and indirect tensile strength results, considering different densities and polymer dosage. By fitting results in a power function, satisfactory correlations were obtained (R2 ≥ 0.90).

No significant change in k was observed from the pure to stabilized tailings, maintaining the order of magnitude practically constant across all experimental conditions investigated (10-6 cm/s).

According to SEM images, the addition of polymer improves the homogeneity in the distribution of particles along the investigated surface. It is hypothesized that polymer stabilization agglutinates the tailing particles, which increases the contact points between the particles, leading to improved load distribution when stressed.

Microtomography analysis demonstrated that there is a decrease in the porosity in percentage, which indicates that the polymer can close some pores in the composite structure.

References

- Consoli, N.C.; Nierwinski, H.P.; Silva, A.P.E.; Sosnoski, J. Durability and Strength of fiber-reinforced compacted gold tailings-cement blends. Geotextiles and Geomembranes 2017, 45, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festugato, L.; Consoli, N.C.; Fourie, A. Cyclic shear behaviour of fibre reinforced mine tailings. Geosynthetics International 2015, 22, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotomayor, J.M.G.; Alelva, G.M.; Casagrande, M.D.T.; Pierozan, R.C. Geomechanical Performance of Gold Ore Tailings-Synthetic Fiber Composites. Geotechnical and Geological Engineering 2024, 42, 4805–4822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, T.G.; Lopes, M.M.; Ribeiro, L.F.M. Geochemical evaluation of soil mixtures with iron ore tailings for use in civil engineering works. Memorias del XXIV CAMSIG-Congreso Argentino de Mecánica de Suelos e Ingeniría Geotécnica. 17-18 y 19 de Octubre de 2018, Salta, Argentina; compilado por Lía Orosco; Silvina Echazú. - 1a ed. - Salta : Universidad Católica de Salta. Eucasa, 2018. 2018; ISBN 978-950-623-154-5. [Google Scholar]

- Alelvan, G.M.; Ferreira, J.W.d.S.; Casagrande, M.D.T.; Consoli, N.C. ; Proposal of New Construction Material: Polymer-Stabilized Gold Ore Tailings Composite. Sustainability 2022 2022, 14, 13648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.W.d.S.; Casagrande, M.D.T.; Teixeira, R.S. Sample dimension effect on equations controlling tensile and compressive strength of cement-stabilized sandy soil under optimal compaction conditions. Case Studies in Construction Materials 2021, 15, e00763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CMBH (2019, June 18). Maravilhas II só voltará a operar após laudo previsto para setembro. https://www.cmbh.mg.gov.br/comunicação/notícias/2019/06/maravilhas-ii-só-voltará-operar-após-laudo-previsto-para-setembro.

- Standard test methods for compressive strength of molded soil-cement cylinders, ASTM Int. ASTM D1633; 2017; pp. 1–4. [CrossRef]

- ASTM D5550, Standard Test Method for Specific Gravity of Soil Solids by Gas Pycnometer, ASTM Int. (2014) 1–5. [CrossRef]

- ASTM D7928, Standard Test Method for Particle-Size Distribution (Gradation) of Fine-Grained Soils Using the Sedimentation (Hydrometer) Analysis, ASTM Int. (2021) 1–23. [CrossRef]

- ASTM D698, Standard Test Methods for Laboratory Compaction Characteristics of Soil Using Standard Effort (12 400 ft-lbf/ft3 or 600 kN-m/m3), ASTM Int. (2021) 1–15. [CrossRef]

- ASTM D2166, Standard Test Method for Unconfined Compressive Strength of Cohesive Soil, ASTM Int. (2024) 1–7. [CrossRef]

- ASTM D5084, Standard Test Methods for Measurement of Hydraulic Conductivity of Saturated Porous Materials Using a Flexible Wall Permeameter, ASTM Int. (2016) 1–30. [CrossRef]

- DNER-ME 228/94, Solos – Compactação em equipamento miniatura, DNER (1994) 1–14.

- Carneiro, A.A.; Casagrande, M.D.T. ; Mechanical and environmental performance of polymer stabilized iron ore tailings. Soils and Rocks 2020, 43, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, P.; Camacho, D. ; The Experimental Characterization of Iron Ore Tailings from a Geotechnical Perspective. Applied Sciences 2024 2024, 14, 5033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boaventura, N.F.; Sousa, T.F. d. P.; Casagrande, M.D.T. The Application of an Eco-Friendly Synthetic Polymer as a Sandy Soil Stabilizer. Polymers 2023, 15, 4626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Consoli, N.C.; Foppa, D.; Festugato, L.; Heineck, K.S. ; Key parameters for strength control of artificially cemented soils. Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering 2007, 133, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheuermann Filho, H.C.; Consoli, N.C. ; Effect of porosity/cement index on behavior of a cemented soil: the role of dosage change. Geotechnical and Geological Engineering 42 2024, 351–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milani, D.M.; Ferreira, J.W. d. S.; Casagrande, M.D.T.; Andrello, A.C.; Teixeira, R.S. Effect of Sandy Soil Partial Replacement by Construction Waste on Mechanical Behavior and Microstructure of Cemented Mixtures. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consoli, N.C.; Marin, E.J.B.; Samaniego, R.A.Q.; Scheuermann Filho, H.C.; Cristelo, N.M.C. Field and laboratory behaviour of fine-grained soil stabilized with lime. Canadian Geotechnical Journal 2020, 57, 933–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consoli, N.C.; da Silva, A.; Barcelos, A.M.; Festugato, L.; Favretto, F. Porosity/Cement Index Controlling Flexural Tensile Strength of Artificially Cemented Soils in Brazil. Geotechnical and Geological Engineering. 2020, 38, 713–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANM – National Mining Agency. (2023). Brazilian mineral yearbook: Main metallic substances (K. A. Medeiros, Tech. Coord.). ANM.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).