Submitted:

11 August 2025

Posted:

13 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Two Competing Models for Carcinogenesis

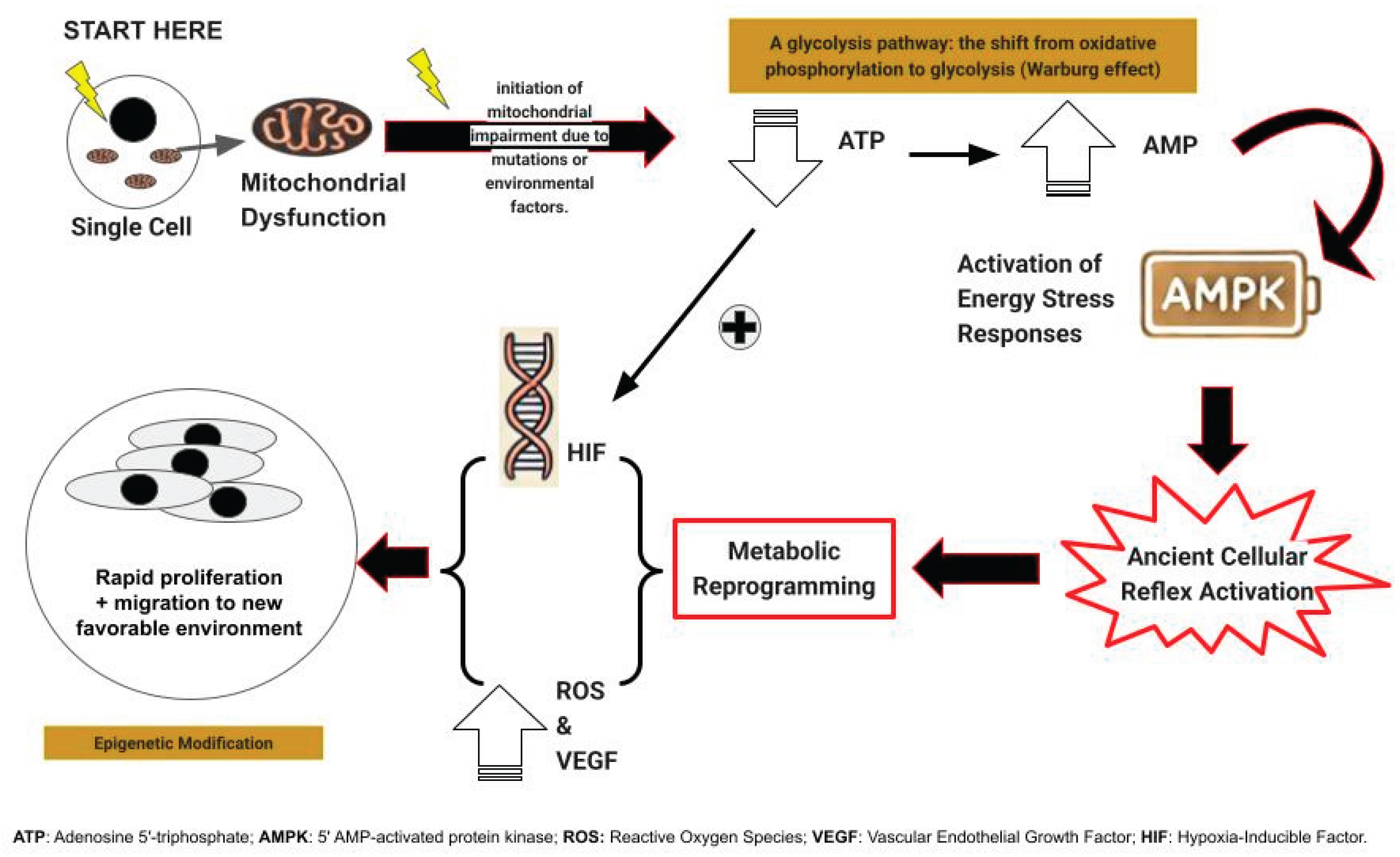

2. An Alternate Hypothesis for Carcinogenesis

3. Manifestations of the Atavistic Reflex in Modern Multicellular Organisms

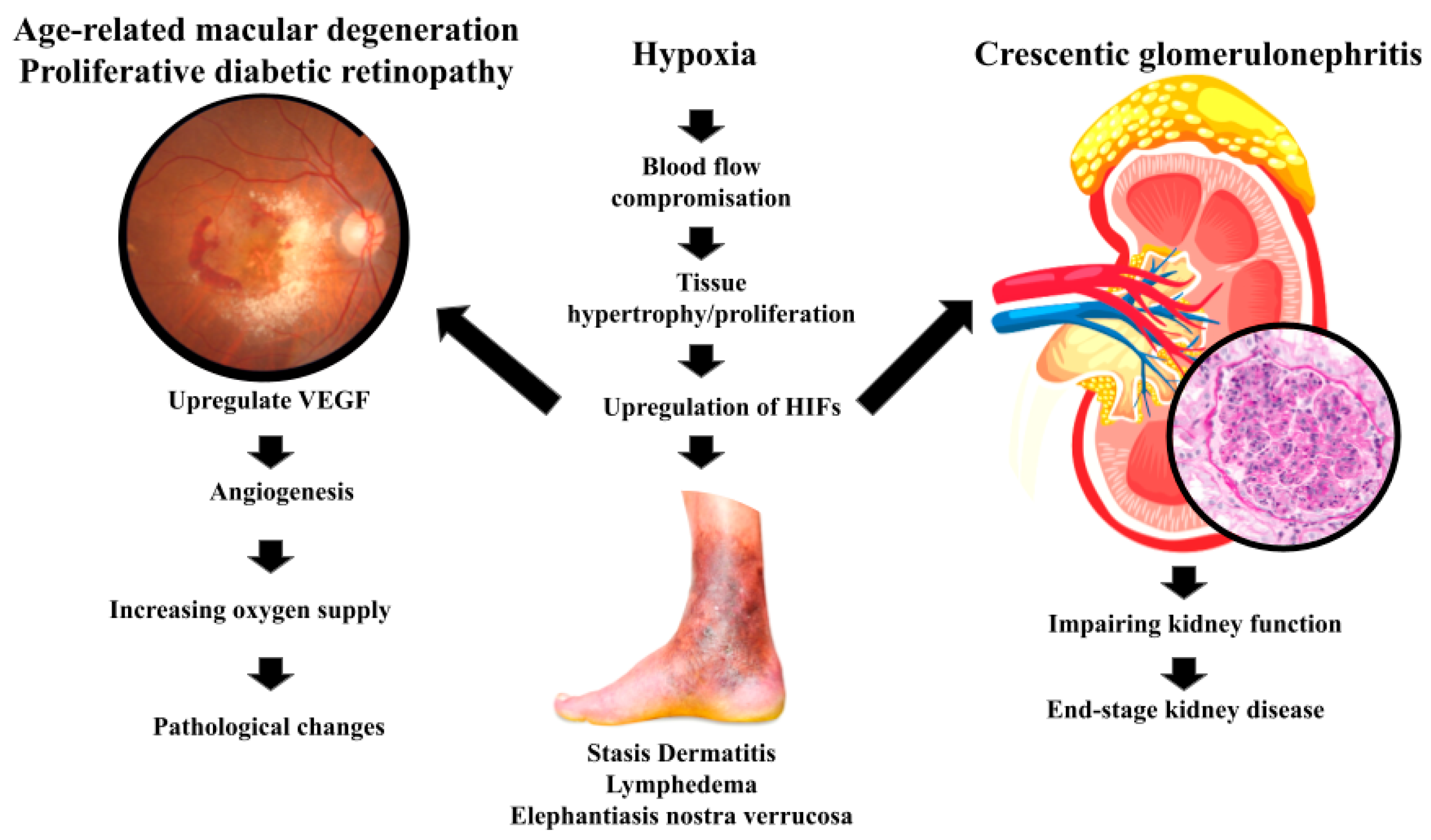

4. Manifestations of the Atavistic Reflex Beyond Cancer

5. Metabolic Reprogramming in Cancer

6. Additional Supporting Evidence: Stem Cells, Autophagy, and AMPK

7. Animal Models and Human Trials Targeting Metabolic Pathways

8. Implications for Cancer Research and Therapy

9. Obesity, Sugary Food and Drink, and Cancer

10. Implications of These Findings for Disorders Other than Cancer

11. Addressing Counterarguments

Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sinkala, M.; et al. Mutational Landscape of Cancer-Driver Genes across Human Cancers. Sci Rep, 2023, 13, 12742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, L.; Venkatachalam, A.; Ben-Neriah, Y.; et al. Tissue-Predisposition to Cancer Driver Mutations. Cells. [CrossRef]

- Ostroverkhova, D.; Przytycka, T. M.; Panchenko, A. R.; et al. Cancer Driver Mutations: Predictions and Reality. Trends Mol Med 2023, 29, 554–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Jiménez, F.; Muiños, F.; Sentís, I.; Deu-Pons, J.; Reyes-Salazar, I.; Arnedo-Pac, C.; Mularoni, L.; Pich, O.; Bonet, J.; Kranas, H.; Gonzalez-Perez, A.; Lopez-Bigas, N.; et al. A Compendium of Mutational Cancer Driver Genes. Nat Rev Cancer, 2020, 20, 555–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, M. H.; Tokheim, C.; Porta-Pardo, E.; Sengupta, S.; Bertrand, D.; Weerasinghe, A.; Colaprico, A.; Wendl, M. C.; Kim, J.; Reardon, B.; Kwok-Shing Ng, P.; Jeong, K. J.; Cao, S.; Wang, Z.; Gao, J.; Gao, Q.; Wang, F.; Liu, E. M.; Mularoni, L.; Rubio-Perez, C.; Nagarajan, N.; Cortés-Ciriano, I.; Zhou, D. C.; Liang, W. W.; Hess, J. M.; Yellapantula, V. D.; Tamborero, D.; Gonzalez-Perez, A.; Suphavilai, C.; Ko, J. Y.; Khurana, E.; Park, P. J.; Van Allen, E. M.; Liang, H.; Lawrence, M. S.; Godzik, A.; Lopez-Bigas, N.; Stuart, J.; Wheeler, D.; Getz, G.; Chen, K.; Lazar, A. J.; Mills, G. B.; Karchin, R.; Ding, L.; Group, M. W.; Network, C. G. A. R.; et al. Comprehensive Characterization of Cancer Driver Genes and Mutations. Cell, 2018, 174, 1034–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, F.; Wu, Q.; et al. Quantitation of Dynamic Total-Body PET Imaging: Recent Developments and Future Perspectives. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging, 2023, 50, 3538–3557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, W. C.; Truong, T. M.; Gagna, C. E.; Lambert, M. W.; Lea, M.; et al. Otto Warburg. Skinmed, 2021, 19, 412–413. [Google Scholar]

- BURK, D.; SCHADE, A. L.; et al. On Respiratory Impairment in Cancer Cells. Science, 1956, 124, 270–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppenol, W. H.; Bounds, P. L.; Dang, C. V.; et al. Otto Warburg’s Contributions to Current Concepts of Cancer Metabolism. Nat Rev Cancer 2011, 11, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, J. S.; Manda, G.; et al. Metabolic Pathways of the Warburg Effect in Health and Disease: Perspectives of Choice, Chain or Chance. Int J Mol Sci. [CrossRef]

- Liberti, M. V.; Locasale, J. W.; et al. Correction to: “The Warburg Effect: How Does It Benefit Cancer Cells?”: [Trends in Biochemical Sciences, 41 (2016) 211]. Trends Biochem Sci, 2016, 41, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaitheesvaran, B.; Xu, J.; Yee, J.; Q-Y, L.; Go, V. L.; Xiao, G. G.; Lee, W. N.; et al. The Warburg Effect: A Balance of Flux Analysis. Metabolomics, 2015, 11, 787–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburg, O.; Wind, F.; Negelein, E.; et al. THE METABOLISM OF TUMORS IN THE BODY. J Gen Physiol, 1927, 8, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warburg, O.; et al. THE CHEMICAL CONSTITUTION OF RESPIRATION FERMENT. Science, 1928, 68, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WARBURG, O.; et al. On Respiratory Impairment in Cancer Cells. Science, 1956, 124, 269–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WEINHOUSE, S.; et al. On Respiratory Impairment in Cancer Cells. Science, 1956, 124, 267–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, A.; Lee, D.; Shim, H.; et al. Metabolic Positron Emission Tomography Imaging in Cancer Detection and Therapy Response. Semin Oncol 2011, 38, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, W. C.; Truong, T. M.; Gagna, C. E.; Lambert, M. W.; Lea, M.; et al. Otto Warburg versus Molecular Biologists: Who Is Correct About Human Carcinogenesis, and Why Does It Matter to Dermatologists? Skinmed 2021, 19, 412–413. [Google Scholar]

- Nishikawa, T.; Gulbahce, N.; Motter, A. E.; et al. Spontaneous Reaction Silencing in Metabolic Optimization. PLoS Comput Biol 2008, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, P.; Kodra, A.; Tomic-Canic, M.; Golinko, M. S.; Ehrlich, H. P.; Brem, H.; et al. The Role of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor in Wound Healing. J Surg Res 2009, 153, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Lin, X.; Fu, X.; An, Y.; Zou, Y.; Wang, J.-X.; Wang, Z.; Yu, T.; et al. Lactate Metabolism in Human Health and Disease. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2022, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybyla-Zawislak, B.; Gadde, D. M.; Ducharme, K.; McCammon, M. T.; et al. Genetic and Biochemical Interactions Involving Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle (TCA) Function Using a Collection of Mutants Defective in All TCA Cycle Genes. Genetics 1999, 152, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín-Aguilar, F.; Pavillard, L. E.; Giampieri, F.; Bullón, P.; Cordero, M. D.; et al. Adenosine Monophosphate (AMP)-Activated Protein Kinase: A New Target for Nutraceutical Compounds. Int J Mol Sci 2017, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.-S.; Jiang, J.; Chen, B.-J.; Wang, K.; Tang, Y.-L.; Liang, X.-H.; et al. Plasticity of Cancer Cell Invasion: Patterns and Mechanisms. Transl Oncol 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novikov, N. M.; Zolotaryova, S. Y.; Gautreau, A. M.; Denisov, E. V.; et al. Mutational Drivers of Cancer Cell Migration and Invasion. Br J Cancer 2021, 124, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardaci S; Ciriolo MR; et al. TCA Cycle Defects and Cancer: When Metabolism Tunes Redox State. Int J Cell Biol. 2012, 161837. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Cui, L.; Lu, S.; Xu, S.; et al. Amino Acid Metabolism in Tumor Biology and Therapy. Cell Death Dis 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, L. R.; Tompkins, S. C.; Taylor, E. B.; et al. Regulation of Pyruvate Metabolism and Human Disease. Cell Mol Life Sci 2014, 71, 2577–2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, G.; Liu, Y.; et al. Hypoxia-Inducible Factors in Cancer Stem Cells and Inflammation. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2015, 36, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zera, K.; Zastre, J.; et al. Thiamine Deficiency Activates Hypoxia Inducible Factor-1α to Facilitate pro-Apoptotic Responses in Mouse Primary Astrocytes. PLoS One 2017, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zera, K.; Zastre, J.; et al. Stabilization of the Hypoxia-Inducible Transcription Factor-1 Alpha (HIF-1α) in Thiamine Deficiency Is Mediated by Pyruvate Accumulation. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2018, 355, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihaylova, M. M.; Shaw, R. J.; et al. The AMPK Signalling Pathway Coordinates Cell Growth, Autophagy and Metabolism. Nat Cell Biol 2011, 13, 1016–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberti, M. V.; Locasale, J. W.; et al. The Warburg Effect: How Does It Benefit Cancer Cells? Trends Biochem Sci, 2016, 41, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopal, K.; Abdualkader, A. M.; Li, X.; Greenwell, A. A.; Karwi, Q. G.; Altamimi, T. R.; Saed, C.; Uddin, G. M.; Darwesh, A. M.; Jamieson, K. L.; Kim, R.; Eaton, F.; Seubert, J. M.; Lopaschuk, G. D.; Ussher, J. R.; Al Batran, R.; et al. Loss of Muscle PDH Induces Lactic Acidosis and Adaptive Anaplerotic Compensation via Pyruvate-Alanine Cycling and Glutaminolysis. J Biol Chem 2023, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yip, W. L.; et al. Influence of Oxygen on Wound Healing. Int Wound J 2015, 12, 620–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cen, R.; Wang, L.; He, Y.; Yue, C.; Tan, Y.; Li, L.; Lei, X.; et al. Dermal Fibroblast Migration and Proliferation Upon Wounding or Lipopolysaccharide Exposure Is Mediated by Stathmin. Front Pharmacol 2021, 12, 781282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knoedler, S.; Broichhausen, S.; Guo, R.; Dai, R.; Knoedler, L.; Kauke-Navarro, M.; Diatta, F.; Pomahac, B.; Machens, H.-G.; Jiang, D.; Rinkevich, Y.; et al. Fibroblasts - the Cellular Choreographers of Wound Healing. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1233800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atlante, A.; Valenti, D.; et al. Mitochondria Have Made a Long Evolutionary Path from Ancient Bacteria Immigrants within Eukaryotic Cells to Essential Cellular Hosts and Key Players in Human Health and Disease. CIMB 2023, 45, 4451–4479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stine, Z. E.; Schug, Z. T.; Salvino, J. M.; Dang, C. V.; et al. Targeting Cancer Metabolism in the Era of Precision Oncology. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2022, 21, 141–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelicano, H.; Martin, D. S.; Xu, R.-H.; Huang, P.; et al. Glycolysis Inhibition for Anticancer Treatment. Oncogene 2006, 25, 4633–4646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Icard, P.; Loi, M.; Wu, Z.; Ginguay, A.; Lincet, H.; Robin, E.; Coquerel, A.; Berzan, D.; Fournel, L.; Alifano, M.; et al. Metabolic Strategies for Inhibiting Cancer Development. Advances in Nutrition 2021, 12, 1461–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaw, F.-Y.; Huang, C.-F.; Wu, Y.-C.; Wu, B.-Y.; et al. Elephantiasis Nostras Verrucosa: Swelling with Verrucose Appearance of Lower Limbs. Can Fam Physician 2012, 58, e551–553. [Google Scholar]

- Sleigh, B. C.; Manna, B.; et al. Lymphedema. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Yosipovitch, G.; Nedorost, S. T.; Silverberg, J. I.; Friedman, A. J.; Canosa, J. M.; Cha, A.; et al. Stasis Dermatitis: An Overview of Its Clinical Presentation, Pathogenesis, and Management. Am J Clin Dermatol 2023, 24, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castilla, D. M.; Liu, Z.-J.; Velazquez, O. C.; et al. Oxygen: Implications for Wound Healing. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle) 2012, 1, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litin, S. C. , Nanda, S., Mayo Clinic, Eds.; et al. Mayo Clinic Family Health Book, Fifth edition. Mayo Clinic: Rochester, MN, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y. B.; Kim, J.-I.; et al. Genetic Studies of Actinic Keratosis Development: Where Are We Now? Ann Dermatol 2023, 35, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, J. W.; Weedon, D.; et al. Weedon’s Skin Pathology, Fifth edition.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Calonje, E. , Brenn, T., Lazar, A. J., MacKee, P. H., Billings, S. D., Eds.; et al. McKee’s Pathology of the Skin: With Clinical Correlations, Fifth edition. Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrington, D. A.; Fisher, C. R.; Kowluru, R. A.; et al. Mitochondrial Defects Drive Degenerative Retinal Diseases. Trends Mol Med 2020, 26, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahidatul-Adha, M.; Zunaina, E.; Aini-Amalina, M. N.; et al. Evaluation of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) Level in the Tears and Serum of Age-Related Macular Degeneration Patients. Sci Rep 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrington, D. A.; Fisher, C. R.; Kowluru, R. A.; et al. Mitochondrial Defects Drive Degenerative Retinal Diseases. Trends Mol Med 2020, 26, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yumnamcha, T.; Guerra, M.; Singh, L. P.; Ibrahim, A. S.; et al. Metabolic Dysregulation and Neurovascular Dysfunction in Diabetic Retinopathy. Antioxidants (Basel) 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majidova, S. R.; et al. Evaluation of Hypoxia and Microcirculation Factors in the Progression of Diabetic Retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2024, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrester, J. V.; Shafiee, A.; Schröder, S.; Knott, R.; McIntosh, L.; et al. The Role of Growth Factors in Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy. Eye 1993, 7, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delbet, J.-D.; Anquetil, V.; Saitoski, K.; Toso, A.; Baumert, T.; Toovey, S.; Manenti, L.; Iacone, R.; Ulinski, T.; Lenoir, O.; Teixeira, G.; Tharaux, P.-L.; et al. #2837 Novel Therapeutic for Crescentic Glomerulonephritis through Targeting CLDN1 in Parietal Epithelial Cells. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation 2024, 39 (Supplement_1), gfae069-0018–2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Lee, K.; D’Agati, V. D.; Wei, C.; Fu, J.; Guan, T.-J.; He, J. C.; Schlondorff, D.; Agudo, J.; et al. Bowman’s Capsule Provides a Protective Niche for Podocytes from Cytotoxic CD8+ T Cells. J Clin Invest 2018, 128, 3413–3424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, Y.; Shimizu, A.; Mori, T.; Ishiwata, T.; Kitamura, H.; Ohashi, R.; Ishizaki, M.; Asano, G.; Sugisaki, Y.; Yamanaka, N.; et al. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Enhances Glomerular Capillary Repair and Accelerates Resolution of Experimentally Induced Glomerulonephritis. Am J Pathol 2001, 159, 599–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, G.; et al. Capillary Rarefaction, Hypoxia, VEGF and Angiogenesis in Chronic Renal Disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2011, 26, 1132–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, X.; Xiao, Z.; Chen, T.; Liang, S. H.; Guo, H.; et al. Glucose Metabolism on Tumor Plasticity, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Front Oncol 2020, 10, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberti, M. V.; Locasale, J. W.; et al. The Warburg Effect: How Does It Benefit Cancer Cells? Trends Biochem Sci 2016, 41, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Ma, J.; Lu, W.; et al. The Significance of Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Peng, Q.; Jiang, X.; Tan, S.; Yang, Y.; Yang, W.; Han, Y.; Chen, Y.; Oyang, L.; Lin, J.; Xia, L.; Peng, M.; Wu, N.; Tang, Y.; Li, J.; Liao, Q.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Metabolic Reprogramming and Epigenetic Modifications in Cancer: From the Impacts and Mechanisms to the Treatment Potential. Exp Mol Med 2023, 55, 1357–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, C.; Wang, X.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, J.; Shi, Y.; et al. An Epigenetic Role of Mitochondria in Cancer. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicks, E. E.; Semenza, G. L.; et al. Hypoxia-Inducible Factors: Cancer Progression and Clinical Translation. J Clin Invest 2022, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, B.; Li, F.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, H.; et al. The Connection between Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle Enzyme Mutations and Pseudohypoxic Signaling in Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2023, 14, 1274239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nong, S.; Han, X.; Xiang, Y.; Qian, Y.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, T.; Tian, K.; Shen, K.; Yang, J.; Ma, X.; et al. Metabolic Reprogramming in Cancer: Mechanisms and Therapeutics. MedComm 2023, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes, F.; Williams, H. C.; San Martin, A.; et al. Metabolic Adaptation in Hypoxia and Cancer. Cancer Letters 2021, 502, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluckova, K.; Tennant, D. A.; et al. Metabolic Implications of Hypoxia and Pseudohypoxia in Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma. Cell Tissue Res 2018, 372, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, M. Y.; Spivak-Kroizman, T.; Venturini, S.; Welsh, S.; Williams, R. R.; Kirkpatrick, D. L.; Powis, G.; et al. Molecular Mechanisms for the Activity of PX-478, an Antitumor Inhibitor of the Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1α. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics 2008, 7, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, W. Y.; McGee, S. L.; Connor, T.; Mottram, B.; Wilkinson, A.; Whitehead, J. P.; Vuckovic, S.; Catley, L.; et al. Dichloroacetate Inhibits Aerobic Glycolysis in Multiple Myeloma Cells and Increases Sensitivity to Bortezomib. Br J Cancer 2013, 108, 1624–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, W.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Jin, R.; Wang, Y.; Guo, H.; Tang, Y.; Yao, X.; et al. Recent Advances of IDH1 Mutant Inhibitor in Cancer Therapy. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 982424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doherty, J. R.; Cleveland, J. L.; et al. Targeting Lactate Metabolism for Cancer Therapeutics. J. Clin. Invest. 2013, 123, 3685–3692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Xia, Z.; Xia, W.; Jiang, P.; et al. Metabolic Reprogramming, Sensing, and Cancer Therapy. Cell Reports 2024, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigerup, C.; Påhlman, S.; Bexell, D.; et al. Therapeutic Targeting of Hypoxia and Hypoxia-Inducible Factors in Cancer. Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2016, 164, 152–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. L. M.; Whitehall, J. C.; Greaves, L. C.; et al. Mitochondrial DNA Mutations in Ageing and Cancer. Mol Oncol 2022, 16, 3276–3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberti, M. V.; Locasale, J. W.; et al. The Warburg Effect: How Does It Benefit Cancer Cells? Trends Biochem Sci 2016, 41, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Ma, J.; Lu, W.; et al. The Significance of Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, K.; Suda, T.; et al. Metabolic Requirements for the Maintenance of Self-Renewing Stem Cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2014, 15, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldsmith, J.; Levine, B.; Debnath, J.; et al. Autophagy and Cancer Metabolism. Methods Enzymol 2014, 542, 25–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberti, M. V.; Locasale, J. W.; et al. The Warburg Effect: How Does It Benefit Cancer Cells? Trends Biochem Sci 2016, 41, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Saud, S. M.; Young, M. R.; Chen, G.; Hua, B.; et al. Targeting AMPK for Cancer Prevention and Treatment. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 7365–7378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.-T.; Xu, J.-Y.; Wang, W.; Zeng, Y.; Jiang, J.; et al. Obesity and Cancer: Mouse Models Used in Studies. Front Oncol 2023, 13, 1125178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stine, Z. E.; Schug, Z. T.; Salvino, J. M.; Dang, C. V.; et al. Targeting Cancer Metabolism in the Era of Precision Oncology. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2022, 21, 141–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, T. A.; Kumar, S.; Chaudhary, A. K.; Yadav, N.; Chandra, D.; et al. Restoration of Mitochondria Function as a Target for Cancer Therapy. Drug Discov Today 2015, 20, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Peng, Q.; Jiang, X.; Tan, S.; Yang, Y.; Yang, W.; Han, Y.; Chen, Y.; Oyang, L.; Lin, J.; Xia, L.; Peng, M.; Wu, N.; Tang, Y.; Li, J.; Liao, Q.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Metabolic Reprogramming and Epigenetic Modifications in Cancer: From the Impacts and Mechanisms to the Treatment Potential. Exp Mol Med 2023, 55, 1357–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivas, U. S.; Tan, B. W. Q.; Vellayappan, B. A.; Jeyasekharan, A. D.; et al. ROS and the DNA Damage Response in Cancer. Redox Biol 2019, 25, 101084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawley, D. J.; Holmberg, L.; Melvin, J. C.; Loda, M.; Chowdhury, S.; Rudman, S. M.; Van Hemelrijck, M.; et al. Serum Glucose and Risk of Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, W.; Shen, X.; Lei, J.; Xu, Q.; Yu, Y.; Li, R.; Wu, E.; Ma, Q.; et al. Hyperglycemia, a Neglected Factor during Cancer Progression. Biomed Res Int 2014, 2014, 461917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, D. D.; Kane, S. M.; et al. Phocomelia. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ferriero, R.; Manco, G.; Lamantea, E.; Nusco, E.; Ferrante, M. I.; Sordino, P.; Stacpoole, P. W.; Lee, B.; Zeviani, M.; Brunetti-Pierri, N. Phenylbutyrate Therapy for Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Complex Deficiency and Lactic Acidosis. Sci Transl Med 2013, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-C.; Tseng, L.-M.; Lee, H.-C.; et al. Role of Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Cancer Progression. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2016, 241, 1281–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fendt, S.-M.; Frezza, C.; Erez, A.; et al. Targeting Metabolic Plasticity and Flexibility Dynamics for Cancer Therapy. Cancer Discov 2020, 10, 1797–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).