Submitted:

11 August 2025

Posted:

13 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

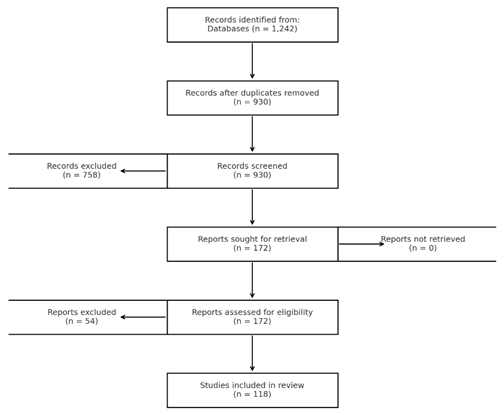

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence

3.2. Pathogenesis

3.3. Diagnostic Features

3.4. Management and Follow up of AI

3.5. Clinical Implications of AI

3.6. Particular Diagnostic Markers in AI

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Adrenal Incidentaloma |

| ACS | autonomous cortisol secretion |

| CT | computed tomography |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| UFC | 24-hours urine free cortisol |

| PET | positron emission tomography |

| FNA | fine-needle aspiration |

| HU | Hounsfield units |

References

- Terzolo, M.; Stigliano, A.; Chiodini, I.; Loli, P.; Furlani, L.; Arnaldi, G.; et al. AME position statement on adrenal incidentaloma. Eur J Endocrinol 2011, 164, 851–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin Fassnacht Wiebke Arlt Irina Bancos, H.D.; John Newell-Price Anju Sahdev Antoine Tabarin, M.T.; Dekkers Stylianos Tsagarakis, O.M. European Society of Endocrinology Clinical Practice Guideline in collaboration with the European Network for the Study of Adrenal 2016.

- Herrera, M.F.; Grant, C.S.; van Heerden, J.A.; Sheedy, P.F.I.D. Incidentally discovered adrenal tumors: an institutional perspective. Surgery (United States) 1991, 110, 101. [Google Scholar]

- Bovio, S.; Cataldi, A.; Reimondo, G.; Sperone, P.; Novello, S.; Berruti, A.; Borasio, P.; Fava, C.; Dogliotti, L.; Scagliotti, G.V.; Angeli, A.T.M. Prevalence of adrenal incidentaloma in a contemporary computerized tomography series. J Endocrinol Invest 2006, 29, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynnette, K. Nieman. Approach to the Patient with an Adrenal Incidentaloma. J CLIN ENDOCRINOL METAB 2010, 4106–13. [Google Scholar]

- Mark Sherlock Andrew Scarsbrook Afroze Abbas Sheila Fraser Padiporn Limumpornpetch Rosemary Dineen, P. S. Adrenal Incidentaloma. Endocr Rev 2020, 775–820. [CrossRef]

- Becker, J.; Woloszyn, J.; Bold, R.; Campbell, M.J. The Adrenal Incidentaloma: An Opportunity to Improve Patient Care. J Gen Intern Med 2018, 33, 256–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, A.; Ingargiola, E.; Solitro, F.; Bollito, E.; Puglisi, S.; Terzolo, M.; et al. May an adrenal incidentaloma change its nature? J Endocrinol Invest 2020, 43, 1301–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgio Arnaldi, M.B. Adrenal incidentaloma. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012, 405–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szychlińska, M.; Baranowska-Jurkun, A.; Matuszewski, W.; Wołos-Kłosowicz, K.; Bandurska-Stankiewicz, E. Markers of subclinical cardiovascular disease in patients with adrenal incidentaloma. Medicina (Lithuania) 2020, 56, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gicquel, C.; Bertherat, J.; Le Bouc, Y.; Bertagna, X. Pathogenesis of adrenocortical incidentalomas and genetic syndromes associated with adrenocortical neoplasms. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2000, 29, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espiard, S.; Bertherat, J. The Genetics of Adrenocortical Tumors. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2015, 44, 311–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faillot, S.; Assie, G. The genomics of adrenocortical tumors. Eur J Endocrinol 2016, 174, R249–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assié, G.; Jouinot, A.; Bertherat, J. The “omics” of adrenocortical tumours for personalized medicine. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2014, 10, 215–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, A.C.; Libutti, S.K. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1: Clinical manifestations and management. Cancer Treat Res 2010, 153, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.K. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Front Horm Res 2013, 41, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamilaris, C.D.C.; Stratakis, C.A. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1): An update and the significance of early genetic and clinical diagnosis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2019, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakker, R.V.; Newey, P.J.; Walls, G.V.; Bilezikian, J.; Dralle, H.; Ebeling, P.R.; et al. Clinical practice guidelines for multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1). Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2012, 97, 2990–3011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rami Alrezk, Fady Hannah-Shmouni CA, Stratakis. MEN4 and CDKN1B mutations: The latest of the MEN syndromes. Endocr Relat Cancer 2017, T195–T208. [CrossRef]

- El-Maouche, D.; Welch, J.; Agarwal, S.K.; Weinstein, L.S.; Simonds, W.F.M.S. A patient with MEN1 typical features and MEN2-like features. Int J Endocr Oncol 2016, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekinci, F.; Soyaltin, U.E.; Kutbay, Y.B.; Yaşar, H.Y.; Demirci Yıldırım, T.; Akar, H. Jak2 v617f mutation scanning in patients with adrenal incidentaloma. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 2017, 13, 150–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eker, F.; Gungunes, A.; Durmaz, S.; Kisa, U.; Celik, Z.R. Nonfunctional adrenal incidentalomas may be related to bisphenol-A. Endocrine 2021, 71, 459–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansmann, G.; Lau, J.; Balk, E.; Rothberg, M.; Miyachi, Y.; Bornstein, S.R. The clinically inapparent adrenal mass: Update in diagnosis and management. Endocr Rev 2004, 25, 309–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Risi-Pugliese, T.; Genc, S.; Bertherat, J.; Larousserie, F.; Bollet, M.; Bassi, C.; etal. Classic Kaposi Sarcoma: An exceptional cause of adrenal incidentaloma. J Endocr Soc 2017, 1, 737–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedia, R.R.; Muinov, L.; Lele, S.M.; Shivaswamy, V. Adrenal oncoctyoma of uncertain malignant potential: A rare etiology of adrenal incidentaloma. Clin Case Rep 2016, 4, 303–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieman, L.K.; Biller, B.M.K.; Findling, J.W.; Newell-Price, J.; Savage, M.O.; Stewart, P.M.; et al. The diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome: An endocrine society clinical practice guideline. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2008, 93, 1526–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.M.; Kim, M.K.; Ko, S.H.; Koh, J.M.; Kim, B.Y.; Kim, S.W.; et al. Clinical guidelines for the management of adrenal incidentaloma. Endocrinology and Metabolism 2017, 32, 200–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Dalmazi, G. Adrenal Incidentaloma: Picking out the High-Risk Patients. Experimental and Clinical Endocrinology and Diabetes 2019, 127, 178–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccato, F.; Barbot, M.; Scaroni, C.; Boscaro, M. Frequently asked questions and answers (if any) in patients with adrenal incidentaloma. J Endocrinol Invest 2021, 44, 2749–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasir, S. Elhassan, Fares Alahdab, Alessandro Prete, Danae A. Delivanis, Aakanksha Khanna, Larry Prokop, Mohammad H. Murad, Michael W. O’ReillyWiebke Arlt IB. Natural History of Adrenal Incidentalomas With and Without Mild Autonomous Cortisol Excess. Ann Intern Med 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cawood, T.J.; Hunt, P.J.; O’Shea, D.; Cole, D.; Soule, S. Recommended evaluation of adrenal incidentalomas is costly, has high false-positive rates and confers a risk of fatal cancer that is similar to the risk of the adrenal lesion becoming malignant; time for a rethink? Eur J Endocrinol 2009, 161, 513–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debono, M.; Bradburn, M.; Bull, M.; Harrison, B.; Ross, R.J.; Newell-Price, J. Cortisol as a marker for increased mortality in patients with incidental adrenocortical adenomas. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2014, 99, 4462–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irina Bancos, A.P. Approach to the Patient With Adrenal Incidentaloma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2021, 106, 3331–3353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenders, J.W.M.; Eisenhofer, G. Update on Modern Management of Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma. Endocrinology and Metabolism 2017, 32, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirică AIBet, a.l. Current approaches and recent developments in the clinical management of catecholamine-producing neuroendocrine tumors. Curr Health Sci J 2016, 42, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Farrugia, F.A.; charalampopoulos, A. Pheochromocytoma. Endocr Regul 2019, 53, 191–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paun, D.L.; Mirica, A. Pheochromocytoma a focus on genetic. 2016.

- Păun, D.L.; Mirica, A. Pheochromocytomas and Paragangliomas: Genotype-Phenotype Correlations. IntechOpen, 2021.

- Rao, D.; Peitzsch, M.; Prejbisz, A.; Hanus, K.; Fassnacht, M.; Beuschlein, F.; et al. Plasma methoxytyramine: Clinical utility with metanephrines for diagnosis of pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Eur J Endocrinol 2017, 177, 103–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenders, J.W.M.; Duh, Q.Y.; Eisenhofer, G.; Gimenez-Roqueplo, A.P.; Grebe, S.K.G.; Murad, M.H.; et al. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: An endocrine society clinical practice guideline. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2014, 99, 1915–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adapa, S.; Naramala, S.; Gayam, V.; Gavini, F.; Dhingra, H.; Hazard, F.K.G.; et al. Adrenal Incidentaloma: Challenges in Diagnosing Adrenal Myelolipoma. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep 2019, 7, 0–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vurallı, D.; Kandemir, N.; Clark, G.; Orhan, D.; Alikaşifoğlu, A.; Gönç, N.; et al. A pheochromocytoma case diagnosed as adrenal incidentaloma. Turkish Journal of Pediatrics 2017, 59, 200–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavropoulos, K.; Imprialos, K.P.; Katsiki, N.; Petidis, K.; Kamparoudis, A.; Petras, P.; et al. Primary aldosteronism in patients with adrenal incidentaloma: Is screening appropriate for everyone? J Clin Hypertens 2018, 20, 942–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funder, J.W.; Carey, R.M.; Mantero, F.; Murad, M.H.; Reincke, M.; Shibata, H.; et al. The management of primary aldosteronism: Case detection, diagnosis, and treatment: An endocrine society clinical practice guideline. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2016, 101, 1889–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Gutiérrez, R.; Bautista-Medina, M.A.; Teniente-Sanchez, A.E.; Zapata-Rivera, M.A.; Montes-Villarreal, J. Pure Androgen-Secreting Adrenal Adenoma Associated with Resistant Hypertension. Case Rep Endocrinol 2013, 2013, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buitenwerf, E.; Links, T.P.; Kema, I.P.; Haadsma, M.L.; Kerstens, M.N. Congenital adrenal hyperplasia as a cause of adrenal incidentaloma. Netherlands Journal of Medicine 2017, 75, 298–300. [Google Scholar]

- Azoury Saïd, Nagarajan Neeraja; Youn Allen, Mathur Aarti; Prescott Jason; Fishma Elliot ZM. Computed Tomography in the Management of Adrenal Tumors: Does Size Still Matter? J Comput Assist Tomogr 2017, 41, 628–32. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pogorzelski, R.; Celejewski, K.; Toutounchi, S.; Krajewska, E.; Woloszko, T.; Szostek, M.; et al. Adrenal incidentaloma - diagnostic and treating problem - own experience. Open Medicine 2018, 13, 281–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muangnoo, N.; Manosroi, W.; Leelathanapipat, N.; Meejun, T.; Chowchaiyaporn, P.; Teetipsatit, P. Predictive Factors of Functioning Adrenal Incidentaloma: A 15-Year Retrospective Study. Medicina (Lithuania) 2022, 58, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirică Aet, a.l. A rare case of metastasized non-functional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor with a good long-term survival. J Med Life 2016, 9, 369–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinnes, J.; Bancos, I.; Di Ruffano, L.F.; Chortis, V.; Davenport, C.; Bayliss, S.; et al. Management of endocrine disease: Imaging for the diagnosis of malignancy in incidentally discovered adrenal masses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Endocrinol 2016, 175, R51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherlock, M.; Scarsbrook, A.; Abbas, A.; Fraser, S.; Limumpornpetch, P.; Dineen, R.; et al. Adrenal incidentaloma. vol. 41. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.L.; Yuan, X.X.; Chen, M.K.; Dai, Y.P.; Qin, Z.K.; Zheng, F.F. Management of adrenal incidentaloma: The role of adrenalectomy may be underestimated. BMC Surg 2016, 16, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iñiguez-Ariza, N.M.; Kohlenberg, J.D.; Delivanis, D.A.; Hartman, R.P.; Dean, D.S.; Thomas, M.A.; et al. Clinical, Biochemical, and Radiological Characteristics of a Single-Center Retrospective Cohort of 705 Large Adrenal Tumors. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes 2018, 2, 30–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plouin, P.F.; Amar, L.; Dekkers, O.M.; Fassnach, M.; Gimenez-Roqueplo, A.P.; Lenders, J.W.M.; et al. European Society of Endocrinology Clinical Practice Guideline for long-term follow-up of patients operated on for a phaeochromocytoma or a paraganglioma. Eur J Endocrinol 2016, 174, G1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaujoux, S.; Mihai, R.; Carnaille, B.; Dousset, B.; Fiori, C.; Porpiglia, F.; et al. European Society of Endocrine Surgeons (ESES) and European Network for the Study of Adrenal Tumours (ENSAT) recommendations for the surgical management of adrenocortical carcinoma. British Journal of Surgery 2017, 104, 358–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirica, R.M.; Paun, S. Surgical Approach in Pheochromocytoma. IntechOpen, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Morelli, V.; Reimondo, G.; Giordano, R.; Della Casa, S.; Policola, C.; Palmieri, S.; et al. Long-term follow-up in adrenal incidentalomas: An Italian multicenter study. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2014, 99, 827–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- L. P, J. C, M. R, P. G, M. O, A. K-Z. Bilateral adrenal incidentaloma with subclinical hypercortisolemia: Indications for surgery. Pol Arch Med Wewn 2014, 124, 387–94. [CrossRef]

- Yener, S.; Ertilav, S.; Secil, M.; Akinci, B.; Demir, T.; Kebapcilar, L.; et al. Increased risk of unfavorable metabolic outcome during short-term follow-up in subjects with nonfunctioning adrenal adenomas. Medical Principles and Practice 2012, 21, 429–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; De Luca, A.; Dutton, H.; Malcolm, J.C.; Doyle, M.A. Cardiovascular outcomes in autonomous cortisol secretion and nonfunctioning adrenal adenoma: A systematic review. J Endocr Soc 2019, 3, 996–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Dalmazi, G. Update on the risks of benign adrenocortical incidentalomas. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 2017, 24, 193–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giordano, R.; Guaraldi, F.; Berardelli, R.; Karamouzis, I.; D’Angelo, V.; Marinazzo, E.; et al. Glucose metabolism in patients with subclinical Cushing’s syndrome. Endocrine 2012, 41, 415–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiodini, I.; Vainicher, C.E.; Morelli, V.; Palmieri, S.; Cairoli, E.; Salcuni, A.S.; et al. Endogenous subclinical hypercortisolism and bone: A clinical review. Eur J Endocrinol 2016, 175, R265–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osella, G.; Reimondo, G.; Peretti, P.; Alì, A.; Paccotti, P.; Angeli, A.; et al. The patients with incidentally discovered adrenal adenoma (incidentaloma) are not at increased risk of osteoporosis. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2001, 86, 604–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiodini, I.; Morelli, V.; Salcuni, A.S.; Eller-Vainicher, C.; Torlontano, M.; Coletti, F.; et al. Beneficial metabolic effects of prompt surgical treatment in patients with an adrenal incidentaloma causing biochemical hypercortisolism. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2010, 95, 2736–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirica, A.; Badarau, I.A.; Stefanescu, A.M.; Mirica, R.; Paun, S.; Andrada, D.; et al. The Role of Chromogranin A in Adrenal Tumors. REVCHIM(Bucharest) 2018, 69, 34–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirica A BI et al. Clinical use of plasma chromogranin A in neuroendocrine tumors. Current Health Science Journal 2015, 41, 69–76.

- Glinicki Piotr Wojciech Jeske, L.B.; KasperlikZałuska, A.; Elżbieta Rosłonowska, M.G.; Zgliczyński, W. Chromogranin A (CgA) in adrenal tumours. Endokrynol Pol 2013, 64, 358–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernini, G.; Moretti, A.; Fontana, V.; Orlandini, C.; Miccoli, P.; Berti, P.; et al. Plasma chromogranin A in incidental non-functioning, benign, solid adrenocortical tumors. Eur J Endocrinol 2004, 151, 215–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arlt, W.; Lang, K.; Sitch, A.J.; Dietz, A.S.; Rhayem, Y.; Bancos, I.; et al. Steroid metabolome analysis reveals prevalent glucocorticoid excess in primary aldosteronism. JCI Insight 2017, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Adrenal masses associated with hormonal activity | Adrenal masses whitout hormonal secretion |

|---|---|

| Adrenal Adenoma –cortisol/aldosterone secretion | Lymphoma |

| Pheochromocytoma | Metastases |

| Primary bilateral macronodular adrenal hyperplasia | Myelolipoma |

| Nodular variant of Cushing’s disease | Neuroblastoma |

| Congenital adrenal hyperplasia | Hemangioma |

| Adrenal carcinoma | Cyst |

| Adrenal masses associated with hormonal activity | Hemorrhage |

| Granuloma | |

| Amyloidosis | |

| Ganglioneuroma | |

| Infiltrative disease |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).