1. Introduction

Because features of complex life emerge with tRNA and tRNAomes, evolution of tRNA is the central and most essential pathway to evolution of a genetic code and complex life [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. To generate complex life requires a genetic code, which cannot be generated except by evolving a genetic adapter. The tRNA molecule was evolved with specialized features that make tRNA difficult to improve or replace as a genetic adapter. Life on Earth coevolved with tRNA, tRNAomes and the genetic code. On another planet or moon, we suggest that life must evolve by a very similar mechanism, utilizing tRNA or a very similar tRNA-like molecule.

Evolution of tRNA, which occurred about 4.2 billion years ago, is described in detail [

1,

2,

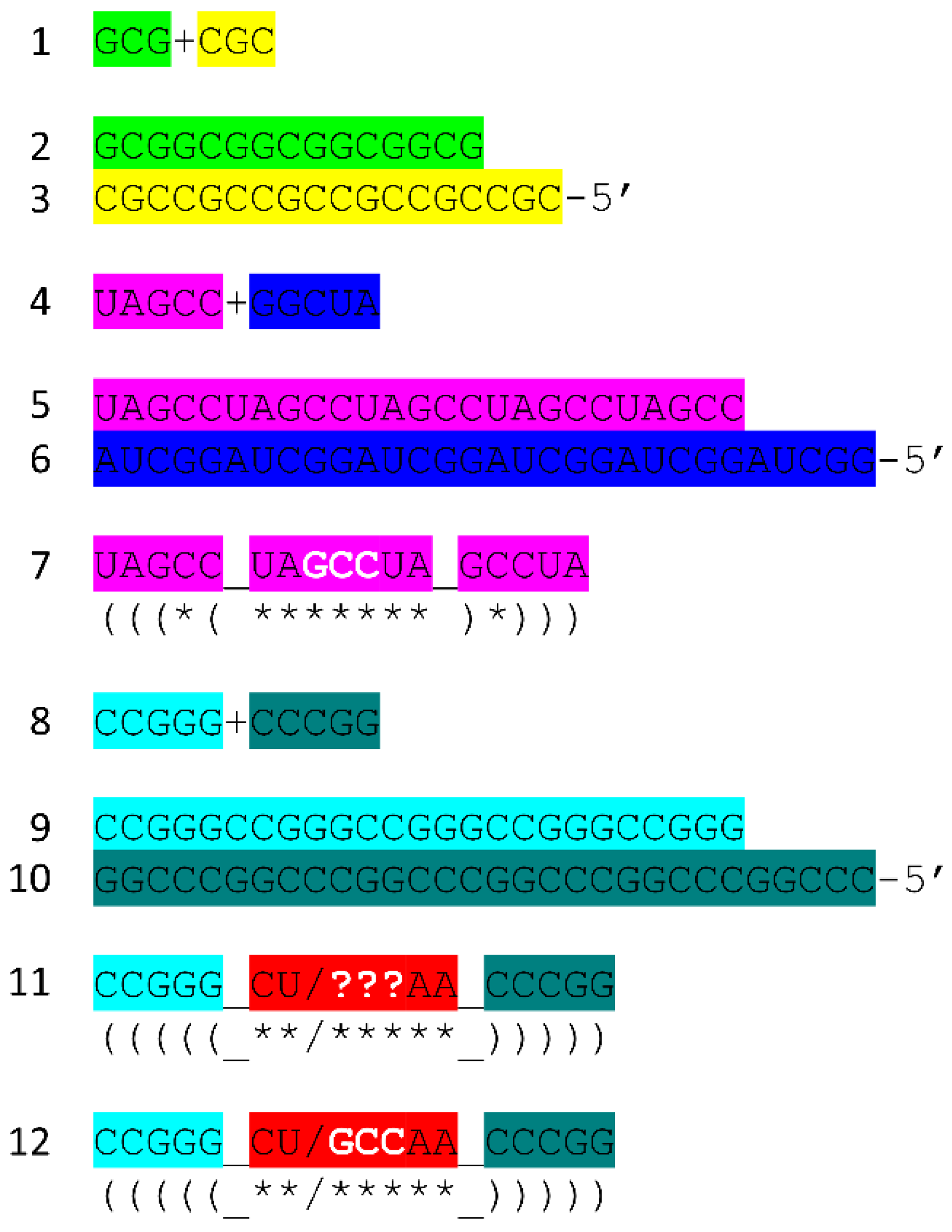

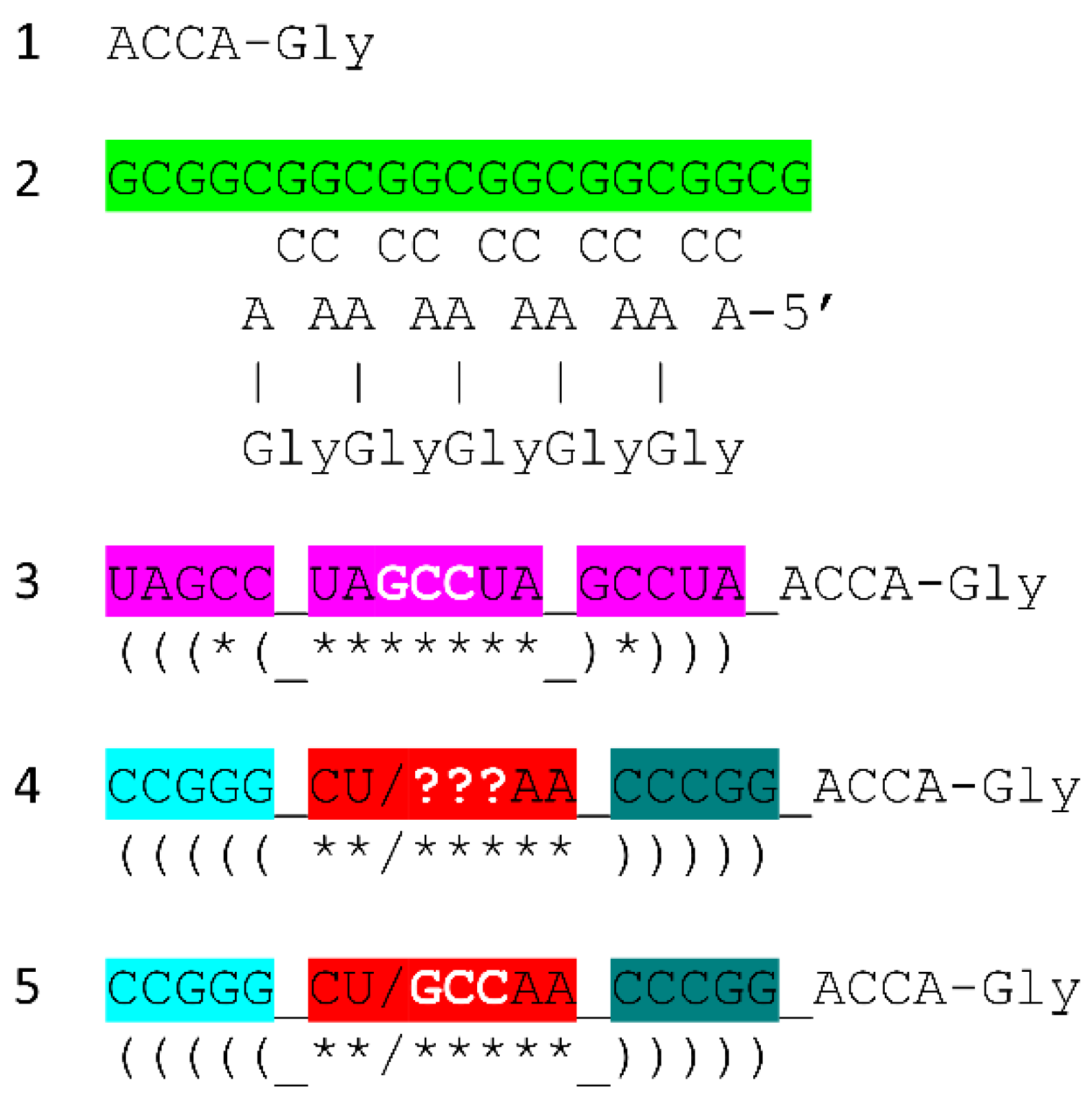

3]. The original tRNA molecule was generated from GCG, CGC and UAGCC repeats and stem-loop-stems (CCGGG_CU/???AA_CCCGG and UAGCCUAGCCUAGCCUA; _ separates sequence features such as stem-loop-stems) [

1,

2,

8,

9,

10,

11]. The pattern is obvious from analysis of typical tRNA diagrams and sequence logos. The original tRNA molecule evolved from ligation of three 31 nt minihelices of mostly known sequence (GCGGCGG_UAGCCUAGCCUAGCCUA_CCGCCGC and GCGGCGG_CCGGG_CU/???AA_CCCGG_CCGCCGC; ? indicates sequences scrambled in coding). In this paper, we substitute the glycine anticodon GCC for ??? We explain this simplifying and possibly correct assignment below. Ligation of 31 nt minihelices was followed by internal deletions of 9 nt within ligated acceptor stems (CCGCCGC_GCGGCGG). The only sequence ambiguities in the pathway (indicated by ?) are the bases that have been altered in coding to form tRNAomes. It is possible that the T loop of tRNA was generated from the complement of the anticodon loop minihelix sequence, because the complementary sequence is almost identical to the sequence given [

1]. ACCA-Gly ligated at the 3’-end allowed the initial tRNA molecule to be utilized to synthesize polyglyine. We posit that, before the advent of sequence-dependent proteins, polyglycine was a major initial chemical driving force behind evolution of living systems. The original print of the tRNA sequence, therefore, was highly patterned and ordered, and shows how the molecule was generated in pre-life. Life evolved around tRNA and the tRNA anticodon loop, explaining why tRNA sequences in living organisms are so highly conserved from pre-life while interacting systems are more innovated.

tRNA, tRNAomes, aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases, first proteins (proteins coevolved with the genetic code), the genetic code, ribosomes and first cells are coevolved. If the tRNA molecule were not generated early in the process, the complex coevolution could not have advanced. We posit that there are very few or no alternate routes to evolution of life on Earth or on other celestial bodies.

To our knowledge, a simple review of tRNA sequence, structure and evolution, written for a broad audience, has not been published. Here, we attempt to construct a straightforward description of tRNA sequence, structure and evolution that can be used as a guide to recreate many of the core steps in emergence of complex life on Earth. Life can be defined in various ways. Here, we refer to complex life supported by a genetic code. Evolution of tRNA and tRNAomes was fundamental to evolve complex life.

2. Materials and Methods

tRNA sequences were obtained from the genomic tRNA database (gtRNAdb) [

12] and the tRNA Gene DataBase Curated by Experts (tRNADB-CE) [

13,

14,

15]. RCSB Protein data bank [

16,

17,

18] files were imaged using ChimeraX [

19,

20,

21].

3. Type II tRNA

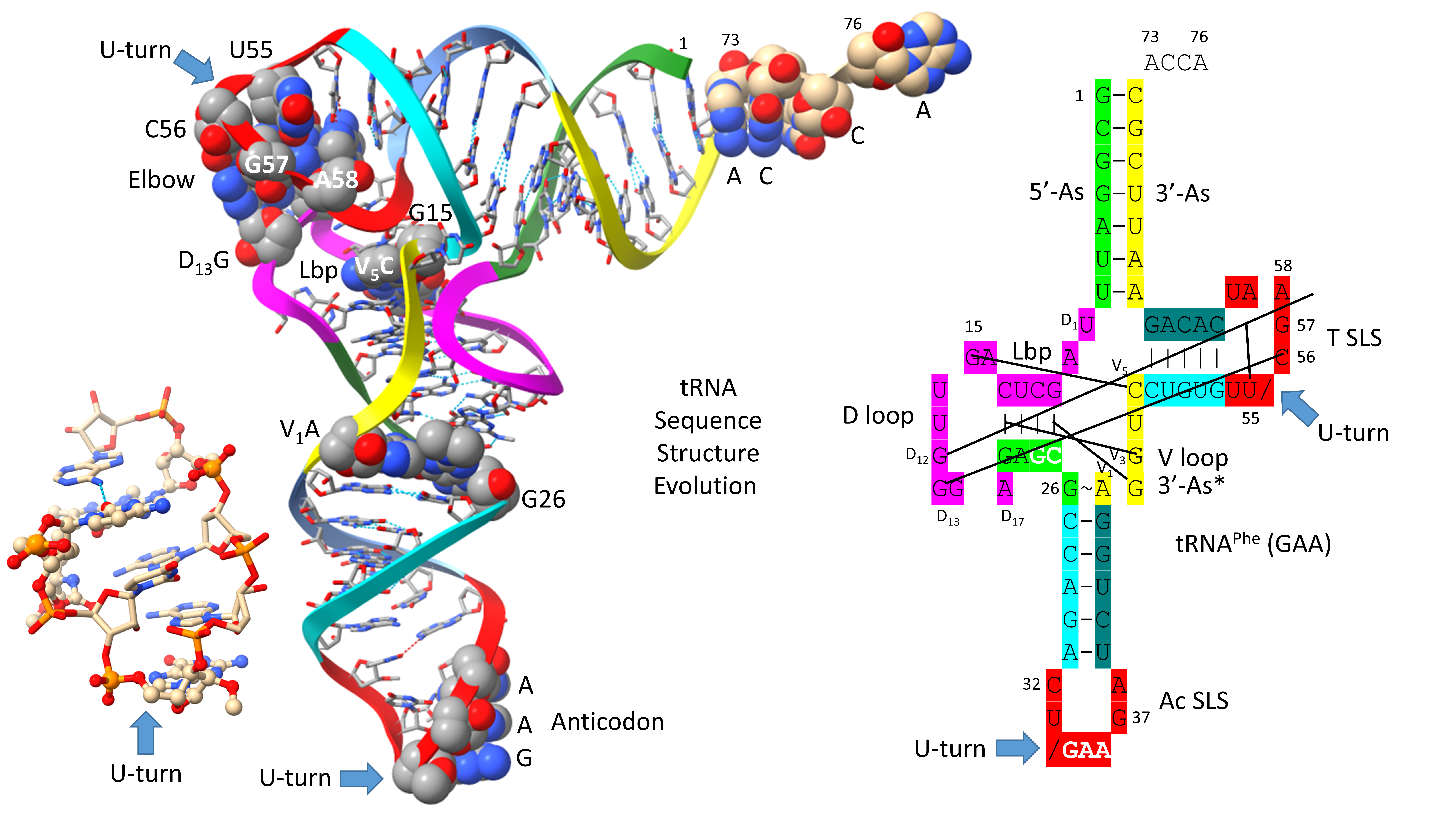

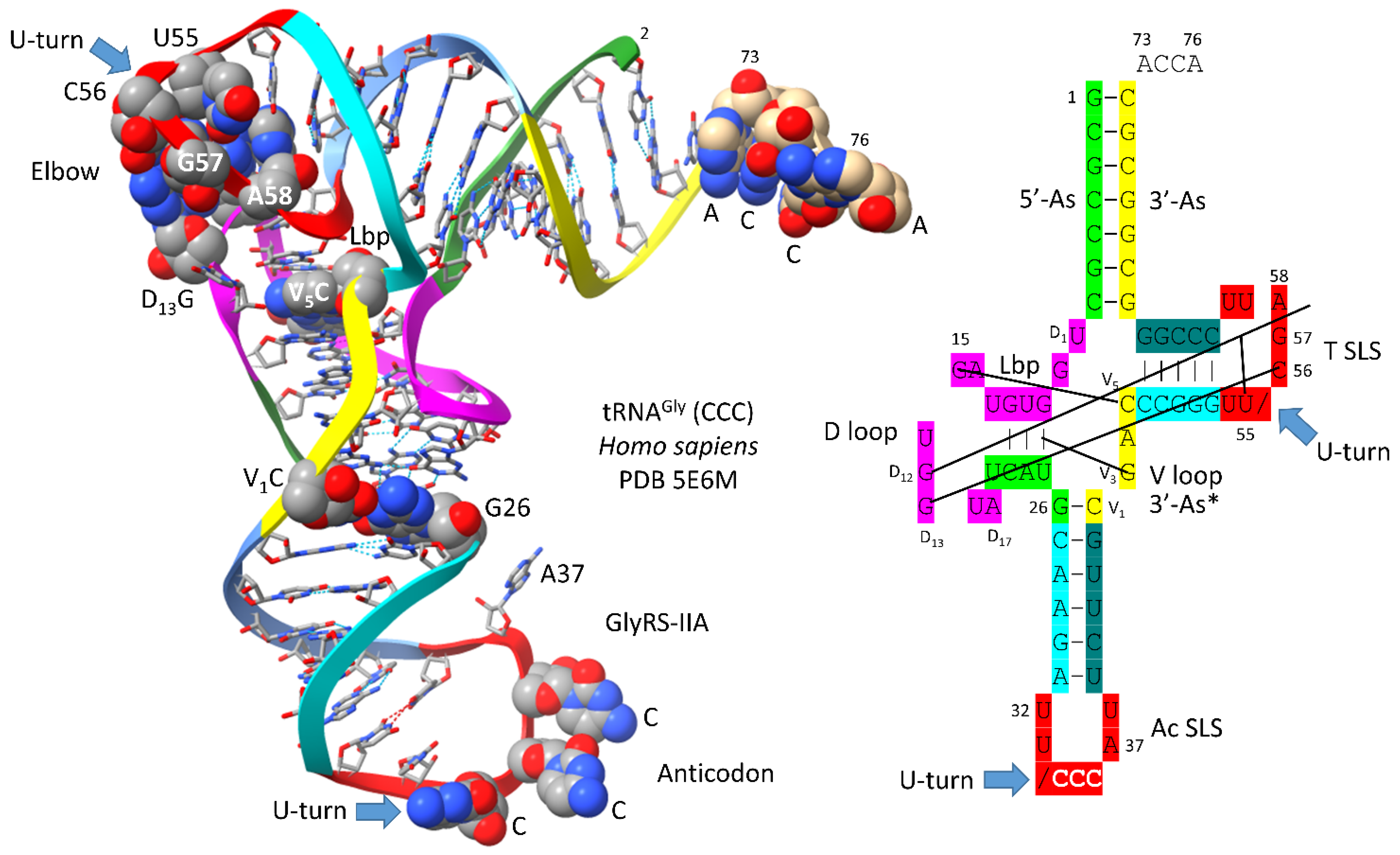

Figure 1 shows a type II tRNA

Leu (CAA) from the ancient Archaeon

Pyrococcus horikoshii, colored according to the three 31 nt minihelix tRNA evolution theorem [

1,

2,

9]. Sequences with a common color are homologous to one another. We posit that the

P. horikoshii tRNA

Leu (CAA) [

22,

23] is very similar to a tRNA

Leu from LUCA (the last universal common (cellular) ancestor), because its sequence is very close to the primordial sequence. To the right of the image is a 2-dimensional tRNA schematic diagram with consistent coloring. Historic numbering of tRNAs breaks down in the D loop, because of deletions, and in the type II V arm and type I V loop, because type II V arm and type I V loop sequences were misaligned and because of indels (insertions and deletions). Here, we use D loop numbering D

1 to D

17. For the type I V loop, we number V

1 to V

5. For the type II V arm, we number V

1 to V

n (V arm of n bases). In the absence of indels, V

1 to V

5 align for type I V loops and type II V arms. The type I V loop was processed from an early version of the type II V arm by a 9 nt internal deletion within ligated 3’- and 5’-acceptor stems (CCGCCGC_GCGGCGG→CCGCC with GC_GCGGCGG deleted).

The image and schematic are colored according to the internal homologies in tRNAs. The 17 nt anticodon and the 17 nt T stem-loop-stems are homologs. Because the complementary sequence of the anticodon stem-loop-stem is almost the same as the forward sequence, the T stem-loop-stem may be derived from the complement of the anticodon stem-loop-stem rather than the direct anticodon stem-loop-stem sequence [

1]. The 5’-As* sequence (tRNA-22 to tRNA-26; green) is homologous to tRNA-3 to tRNA-7 of the 5’-As (As for acceptor stem).

The tRNA

Leu (CAA) image in

Figure 1 is from a co-crystal with the LeuRS-IA charging enzyme [

22,

23]. The 3’-ACCA is bent down into the LeuRS-IA aminoacylating active site for addition of leucine (the “hairpin” conformation). LeuRS-IA binding causes some unwinding of the tRNA

Leu anticodon loop, although LeuRS-IA does not bind the anticodon loop directly. Because leucine is in a 6-codon box in the standard code, LeuRS-IA binds the type II V arm instead of the anticodon loop as a determinant for cognate tRNA

Leu charging.

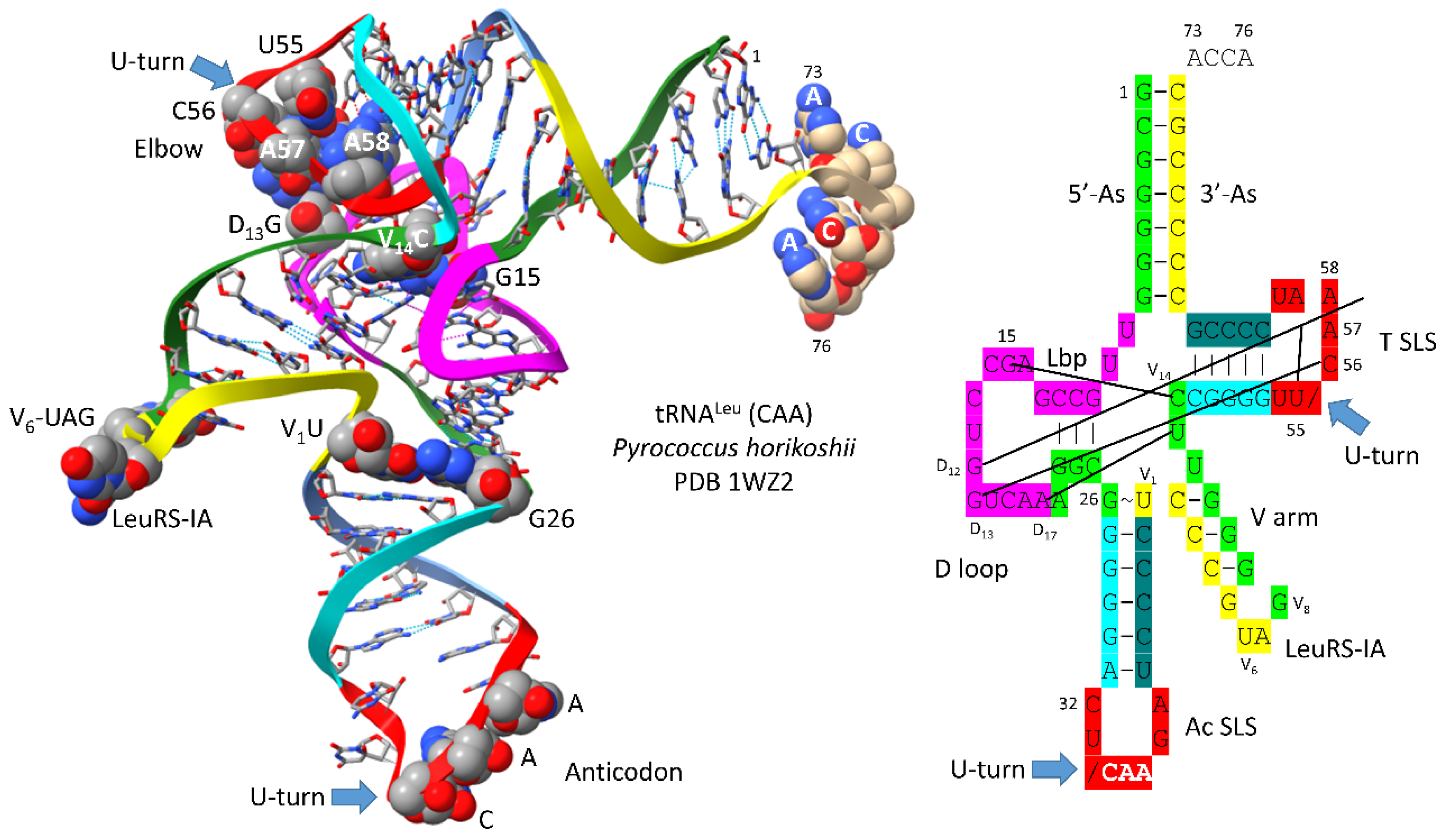

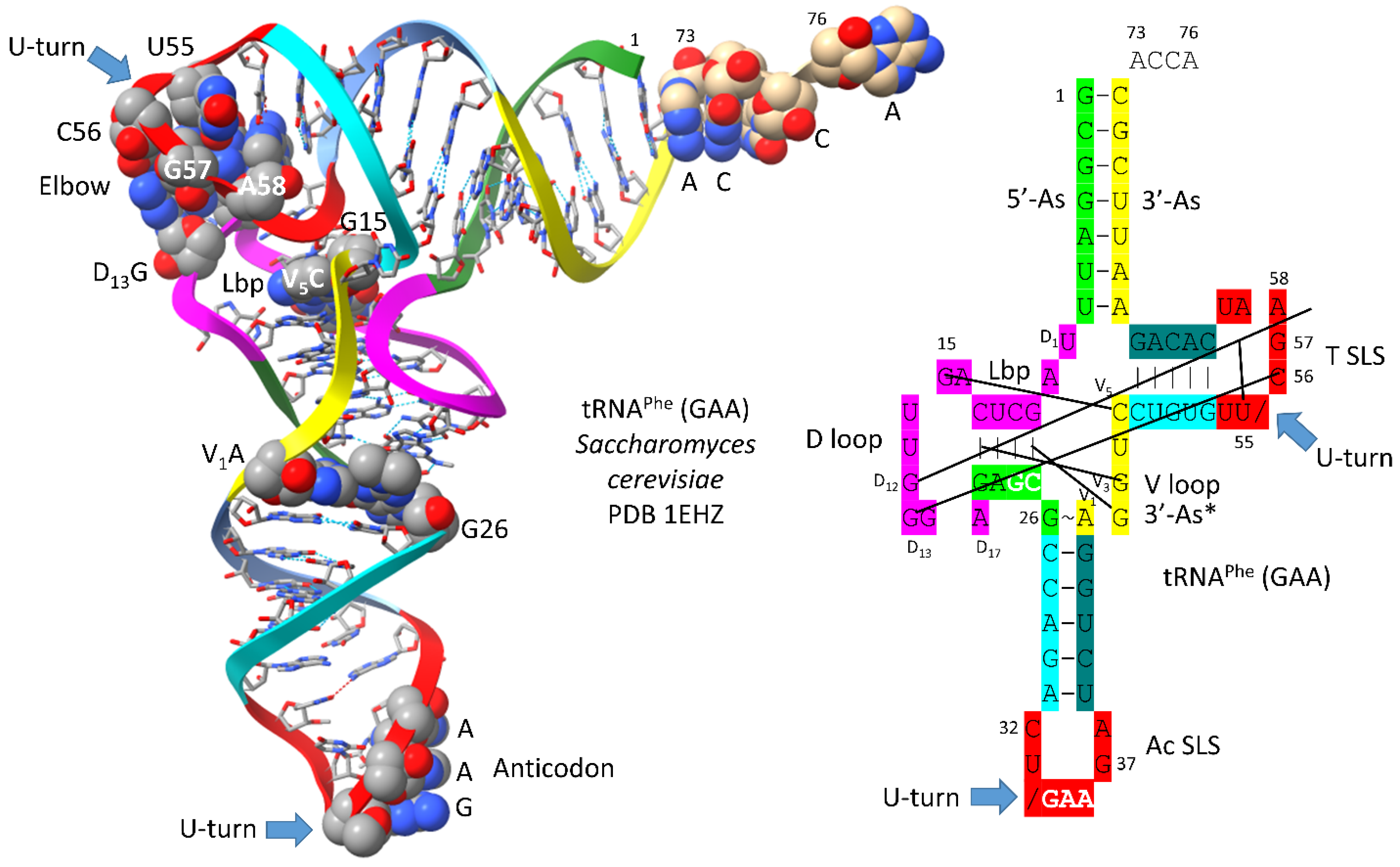

Figure 2 shows a comparison of type II V arms and type I V loops [

1,

8]. Type II V arms were derived from ligation of a 7 nt 3’-acceptor stem (CCGCCGC) to a 7 nt 5’-acceptor stem (GCGGCGG) [

1,

7,

8]. Such a 14 nt sequence could pair along its entire length. This 14 nt sequence evolved to the tRNA

Leu and tRNA

Ser type II V arms by forming distinct stem-loop-stems with different cognate trajectories from the tRNA body. V

1U interacts with tRNA-26G. The V arm is utilized as a determinant for cognate Leu and Ser charging at the tRNA 3’-CCA end. The trajectory of the V arm from the tRNA body is determined from the number of unpaired bases between the 3’-V arm stem and the Levitt base CV

n (for a V arm of n nucleotides). To specify cognate charging, the trajectory of the V arms is almost always distinct for the set of tRNA

Leu (5 tRNAs) and the set of tRNA

Ser (4 tRNAs) and is a determinant for cognate recognition [

8].

Leucine and serine are in 6-codon boxes in the standard genetic code. The type II V arm is utilized as a major determinant for cognate leucine and serine charging of tRNAs. In Archaea, the type II V arm is only utilized by tRNA

Leu (5 tRNAs) and tRNA

Ser (4 tRNAs). In Bacteria, tRNA

Tyr, tRNA

Leu and tRNA

Ser utilize type II V arms [

8]. In Archaea, almost all tRNA

Leu V arms are 14 nt in length, which is the primordial length. Ligating a 7 nt 3’-acceptor stem to a 7 nt 5’-acceptor stem generates a 14 nt sequence (initially CCGCCGC_GCGGCGG) (

Figure 2, line 1). The type II tRNA

Leu and tRNA

Ser V arms evolved to form stem-loop-stems utilized as determinants by LeuRS-IA and SerRS-IIA for cognate amino acid charging at tRNA-76A. The type I V loop was processed from the primordial type II V arm sequence (initially CCGCCGC_GCGGCGG processed to CCGCC) (line 4).

Type II tRNAs and type I tRNAs are homologous over their entire lengths except for the 9 nt deleted segment in the type I tRNA V loop region. Most contacts in type II tRNAs and type I tRNAs are the same. Some core interactions are noted in

Figure 1. The “elbow” of tRNA is where the D loop and the T loop interact. D

12G intercalates between tRNA-57A (sometimes 57G) and tRNA-58A and hydrogen bonds to tRNA-55U, just before the T loop U-turn. D

13G forms a slightly bent Watson-Crick pair with tRNA-56C. The Levitt reverse Watson-Crick base pair connects tRNA-15G (D

8G) and V

14C. A reverse Watson-Crick pair is similar to a Watson-Crick pair with one of the bases flipped over. A G=C reverse Watson-Crick pair forms two hydrogen bonds.

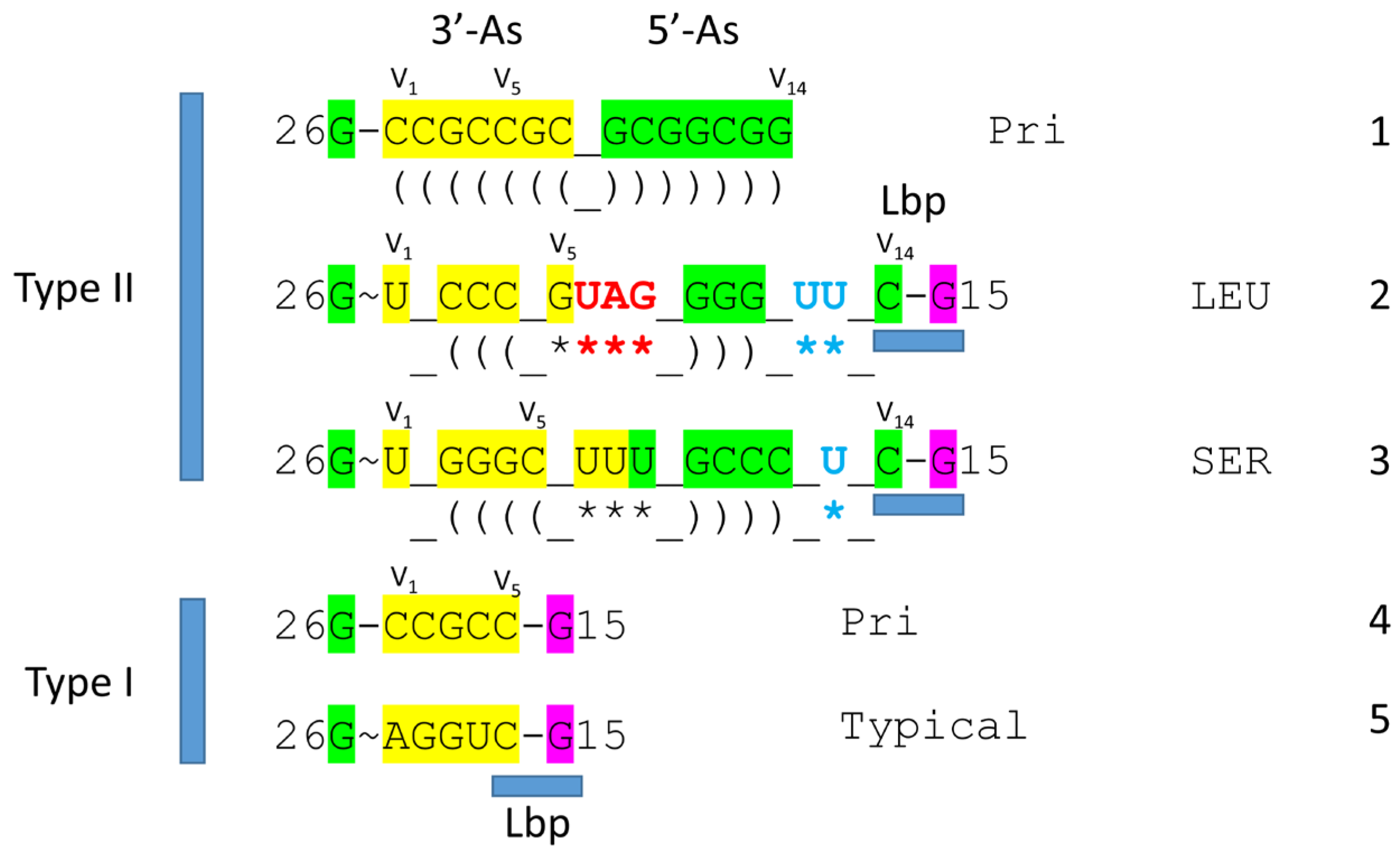

4. Type I tRNA

A type I tRNA

Phe (GAA) from

Saccharomyces cerevisiae is shown in

Figure 3 [

24]. Although this is a eukaryotic tRNA

Phe, it is very similar in structure and sequence to an archaeal tRNA

Phe. The PDB 1EHZ structure was selected because of its high resolution and completeness. Also, this tRNA

Phe (GAA) is fully modified as in vivo. The discussion above for type II tRNA

Leu mostly describes the tRNA

Phe (GAA) structure. The 17 nt D loop core sequence (magenta) has 3 nts deleted. The V loop sequence is 5 nt in length with the typical and common sequence V

1-AGGUC-V

5 (

Figure 2; line 5). V

1A interacts with tRNA-26G. V

2G interacts with the D stem. tRNA-10G (D

3G) pairs with tRNA-25C, and V

2G-10G-25C form a triplex interaction. Similarly, V

3G forms a triplex interaction with tRNA-22G=tRNA-13C (D

6C). V

4U flips away from the body of the tRNA. The elbow contacts and Levitt reverse Watson-Crick pair (tRNA-15G (D

8G) binds V

5C) are as described above for the type II tRNA

Leu in

Figure 1.

5. The First tRNA Was a tRNAGly

Figure 4 shows a human tRNA

Gly (CCC) [

25]. The image was selected as the best available tRNA

Gly image with the highest similarity to archaeal tRNA

Gly. The tRNA

Gly (CCC) was taken from a co-crystal with GlyRS-IIA. GlyRS-IIA unwinds the anticodon loop to expose 35-CCA-37 as a determinant for cognate tRNA

Gly (CCC) charging with glycine at 3’-ACCA (at the 3’-O of the ribose ring of 76A). From the primordial sequence, 4 nt were deleted from the 17 nt D loop core, as indicated in the schematic. One nt (V

2 or V

3) was deleted within the type I V loop. V

3G forms a triplex interaction with D stem residues D

3G and 25U, as indicated in the schematic.

In

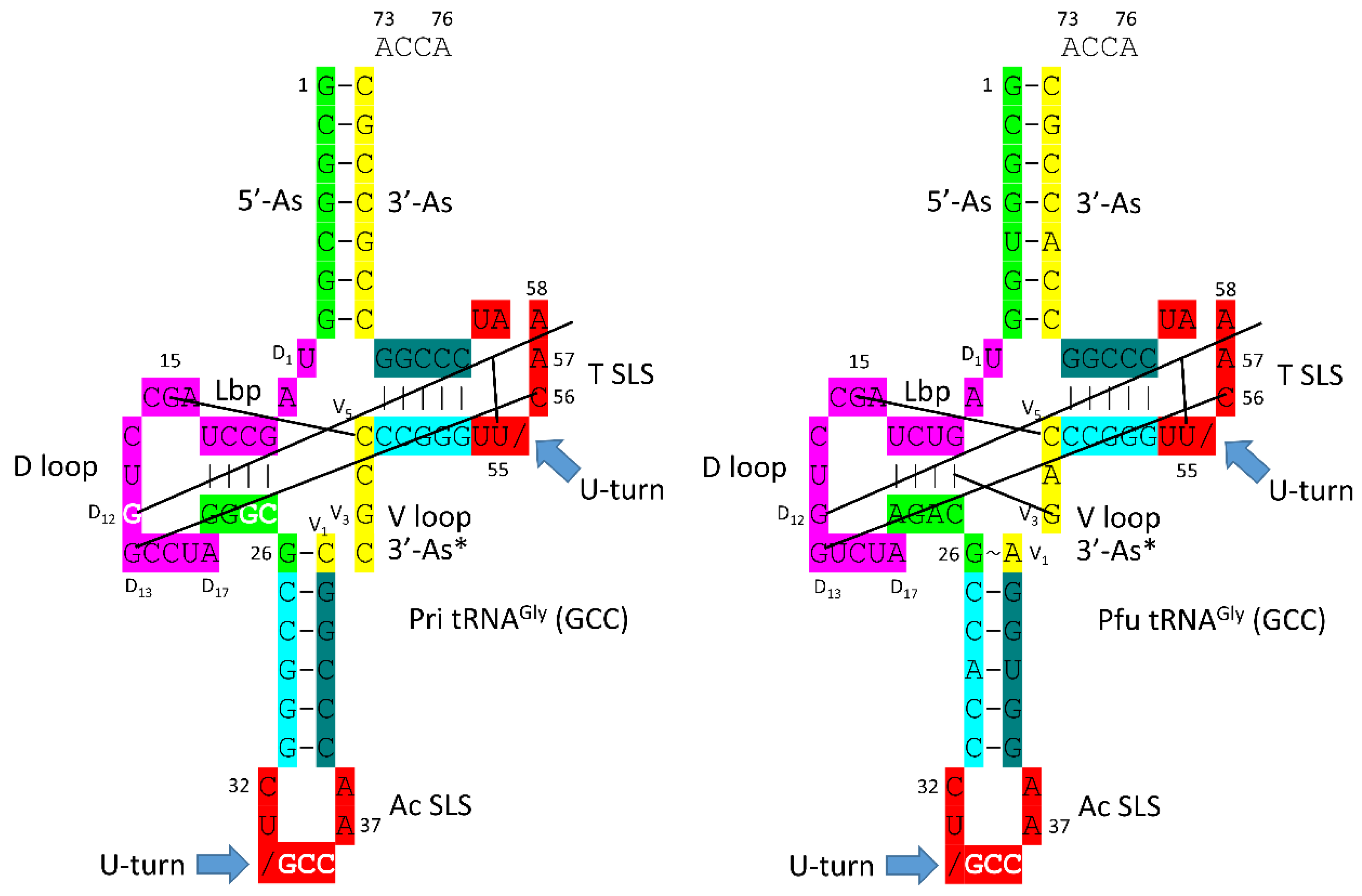

Figure 5, schematic diagrams of a primordial (Pri) type I tRNA and an archaeal

Pyrococcus furiosus tRNA

Gly (GCC) are shown. We have assigned a GCC anticodon to tRNA

Pri, as we explain below. The sequences are very similar after ~4.2 billion years, making tRNA

Gly derived from an ancient Archaeon a living fossil of the inception of life. We posit that the first tRNAs on Earth were utilized to synthesize polyglycine. Selection for polyglycine is posited to have driven evolution of the first cells. tRNA

Gly appears to be the first tRNA from which other tRNAs were derived [

26]. In an ancient Archaeon, tRNA

Gly is the most similar tRNA to tRNA

Pri.

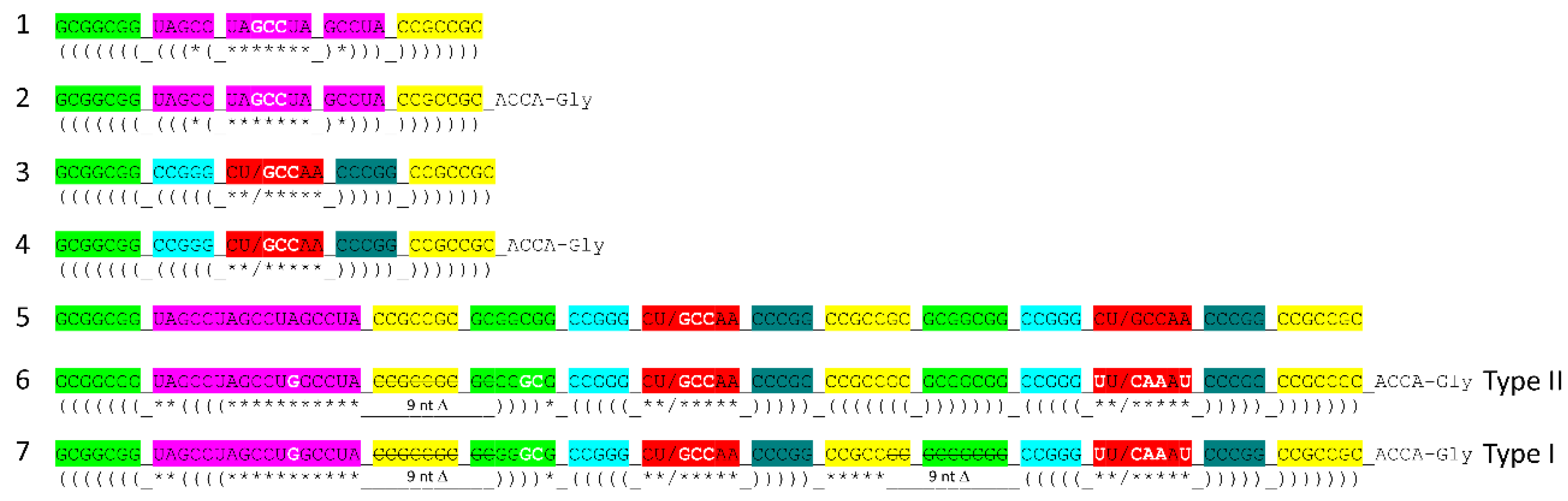

In

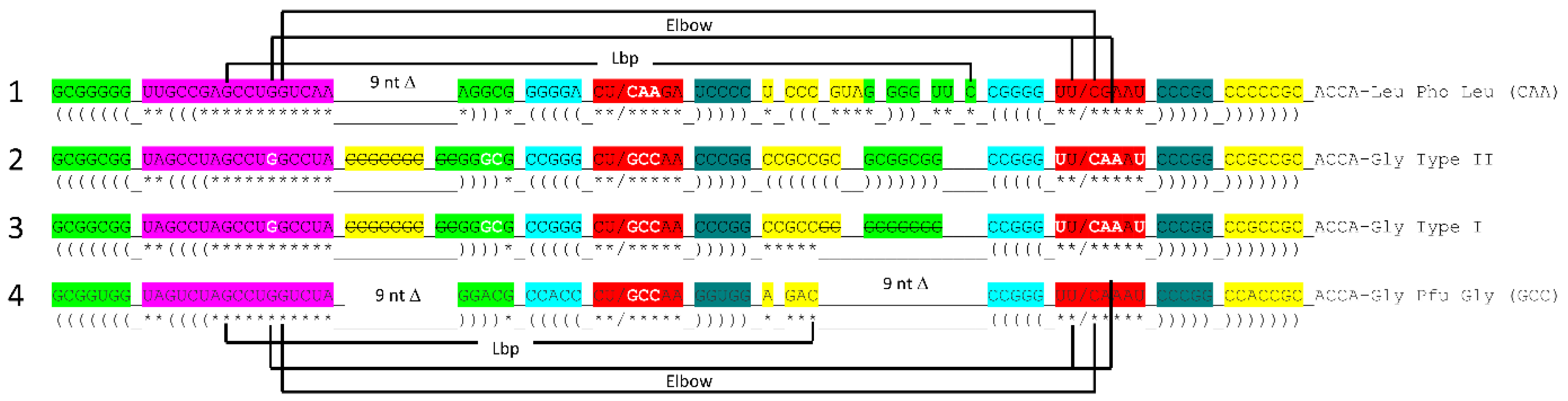

Figure 6, evolution of the first type II and type I tRNAs is summarized. tRNA

Leu (CAA) from

Pyrococcus horikoshii is shown in line 1 (see also

Figure 1). The primordial type II tRNA sequence from which tRNA

Leu and tRNA

Ser were derived is shown in line 2. A tRNA

Gly (GCC) from

Pyrococcus furiosus, which is an ancient Archaeon, is shown in line 4 (

Figure 5; right panel).

6. Breaking tRNAPri into Its Component Parts

To generate complex life in a laboratory requires directed evolution of tRNA

Pri. Fortunately, tRNA

Pri was evolved from RNA repeats (GCG, CGC and UAGCC) and inverted repeats (CCGGG_CU/???AA_CCCGG), making this goal feasible. The only slight deviation from the order is 3’-ACCA-Gly, which is a short adapter molecule that was attached to many RNAs during chemical evolution of life [

1]. tRNA

Pri, therefore, can be broken into its separate parts. Those components can then be separated and combined, and processes can be inferred for transitions that resulted in tRNA

Pri evolution. Because tRNA

Pri was so highly ordered, its evolution pathway was defined and intermediates in tRNA evolution were identified. Reproducing transitions between these components would be a major contribution to understanding the evolution of life.

Figure 7 shows the tRNA

Pri components that require synthesis. 5’-acceptor stems evolved from GCG repeats. 3’-acceptor stems evolved from complementary CGC repeats. We infer that a chemical mechanism evolved to generate GCG and complementary CGC repeats on pre-life Earth (

Figure 7, lines 1-3). The conservation of GCG and CGC repeats in tRNAs implies a complementary replication mechanism on pre-life Earth. Because processive 5’→3’ ribozyme complementary replication has been somewhat difficult to reproduce in laboratories, perhaps ligation on a template was the mechanism utilized for initial complementary replication [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31].

More complex RNA repeats were also synthesized. The 17 nt D loop minihelix core was based on a UAGCC repeat (initially UAGCCUAGCCUAGCCUA) (

Figure 7, lines 4-7). Because GCG and CGC repeats are complementary, we infer that GGCUA repeats (blue) were also synthesized on pre-life Earth (lines 4 and 6). We note that a 17 nt UAGCC repeat can fold into a stem-loop-stem that presents a GCC anticodon (line 7). We infer that this molecule could attach 3’-ACCA-Gly for use in polyglycine synthesis using an extended GCG repeat (line 2) as template. Because the GGCUA repeat (line 6) was not preserved in tRNA sequences, this sequence appears now to be extinct. We infer that many RNA repeats and inverted repeats were present on pre-life Earth, and, perhaps, only those repeats preserved in tRNA sequences survived the transition to Darwinian selection with evolution of the first cells.

In addition to the 17 nt UAGCCUAGCCUAGCCUA stem-loop-stem (

Figure 7, line 7), an essential 17 nt stem-loop-stem with a 7 nt U-turn loop evolved (

Figure 7, lines 8-12) (CCGGG_CU/???AA_CCCGG or CCGGG_CU/GCCAA_CCCGG). We argue that the 7 nt U-turn loop (i.e., CU/???AA or CU/GCCAA) was the most important innovation in chemical evolution of life on Earth. Without this specialized and ribozyme nuclease-resistant loop, tRNA could not have evolved as the genetic adapter. Without a genetic adapter as good or better than tRNA, complex life could not have evolved. By the time of LUCA, the sequence designated ??? was scrambled in evolution of tRNAomes. If the anticodon sequence was originally GCC, as for the 17 nt UAGCC repeat, and with 3’-ACCA-Gly added at the RNA 3’-end, an extended GCG repeat could be utilized as a template to synthesize polyglycine. We favor the idea that polyglycine was the main selective driver of chemical evolution during pre-life on Earth.

7. Chemical Evolution of the First Translation Systems

In

Figure 8, we show a model for one of the first translation systems, and one that should be capable of synthesis of polyglycine in a laboratory. Through Darwinian selection, the model ought, also, to be capable of extension to evolve a fairly modern form of the ribosome. We propose that ACCA-Gly found in most tRNAs was the most primitive adapter molecule [

1]. An extended GCG repeat includes many iterations of the sequence CGGC which can pair with ACCA-Gly to bring many ACCA-Gly into proximity within an RNA environment (

Figure 8, lines 1 and 2). Synthesis of polyglycine and polypeptides involves dehydration. The peptidyl-transferase center of the modern ribosome can be viewed as a dehydration and orientation center to facilitate tRNA-linked peptide bond formations at the A and P sites (A for aminoacyl- and P for peptidyl-sites). A tangled GCG repeat forms a dehydrating environment because polar RNA binds water. Also, wet-dry cycles can be done to promote dehydration for glycine polymerization. We posit that the system shown schematically in line 2 can be utilized with wet-dry cycles to form polyglycine using published procedures [

32].

A second generation polyglycine synthesis system is also indicated (

Figure 8, lines 3-5). We posit that ACCA-Gly was ligated to many RNAs during pre-life. 17 nt stem-loop-stems with 3’-ACCA-Gly, combined with an extended GCG repeat (a primitive pre-ribosome), with wet-dry cycles, should be capable of synthesizing polyglycine. From analysis of tRNA evolution and sequence, we see no reason to require synthesis of more complex polypeptides than polyglycine prior to evolution of tRNA. This does not mean that more complex polypeptides than polyglycine were not present, but they likely would have been synthesized using other mechanisms. Lines 3-5 indicate evolution of stem-loop-stem snap-back primers for complementary replication, which may have initially involved assembly and ligations of short RNAs on a complementary RNA template framed by snap-back primers. Such a mechanism requires a ribozyme ligase and endonucleases to excise products.

8. Evolution of 3rd and 4th Generation Polyglycine Synthesis Systems

Figure 9 indicates further evolution of polyglycine synthesis systems, 31 nt minihelices (lines 1-4) and tRNAs (lines 5-7). As previously described, tRNA was generated by ligation of three 31 nt minihelices: one 31 nt D loop minihelix (line 1) and two 31 nt anticodon stem-loop-stem minihelices (line 3) [

1,

2,

9]. Thus, a 93 nt tRNA precursor was formed as a replication intermediate for 31 nt minihelices. We imagine the 93 nt tRNA precursor as part of a much larger molecule that includes snap-back primers and the complementary strand. The 93 nt precursor was then processed by a single 9 nt internal deletion within ligated 3’- and 5’-acceptor stems to form a primordial type II tRNA (line 6). To form type I tRNA, an additional internal 9 nt deletion occurred within the V loop region (line 7). Remarkably, the two internal 9 nt deletions to form type I tRNAs are identical on complementary strands, once again indicating complementary replication in the pre-life world.

The mechanism proposed for synthesis of the first tRNAs (

Figure 9, lines 1-7) can be extended to more complex molecules, such as rRNAs and first proteins [

1]. Very clearly large complex RNAs could be generated by ligation of multiple RNAs. The 93 nt precursor from which tRNA was derived is thought to be part of a much larger, circular RNA molecule capped with ligation of stem-loop-stems (i.e.,

Figure 7, lines 7, 11 and 12; and

Figure 9, lines 1 and 3) before the excision of tRNAs. Once translation systems evolved, translation of ligated RNAs would generate some of the first complex proteins. There is little reason to assume that the first RNAs and proteins were necessarily simple molecules that assumed more complex forms later in evolution. In pre-life, many RNAs and first proteins that coevolved with the genetic code were long, varied and complex.

9. Alternate Genetic Adapters

Somewhat surprisingly, there does not appear to be a large number of alternatives to the genetic adapter tRNA evolved on planet Earth. Part of the problem is illustrated in Figure 10. If the D loop minihelix were to be replaced at the 5’-end of the tRNA precursor by a third anticodon loop minihelix, folding into a tRNA becomes much more unlikely. The greater flexibility of the D loop 17 nt minihelix core, compared to the stiffness of the anticodon stem-loop-stem minihelix, allows for tRNA folding. Three anticodon stem-loop-stem minihelices (Figure 10, line 1) are expected to be processed to three anticodon stem-loop-stem 31 nt minihelices (line 2), because of their more stable folding (compare to

Figure 9, lines 5-7). Our claims can be tested computationally and by experiment. We posit that in evolution many alternate adapter folds and sequences were tested against the pathway that produced type II and type I tRNAs (

Figure 9, lines 5-7). The mechanisms that were chemically selected were the fastest mechanism that resulted in the most successful adapter molecule.

Life as we know it on Earth evolved chemically using the RNA adapter tRNA in an aqueous environment. We know of no other chemistries than aqueous chemistry and RNA chemistry that would have been likely to evolve as enabling a genetic adapter as tRNA. We can imagine a sequence substitution for the 17 nt D loop minihelix core, but that substitution likely could not be a 17 nt anticodon stem-loop-stem (compare

Figure 9 and Figure 10). tRNA was generated from RNA repeats and inverted repeats that, apparently, were generated accurately on pre-life Earth. Stem-loop-stems were chemically evolved, perhaps to cap linear RNAs for accurate complementary replication via ligation (a ribozyme ligase) or accurate processive replication. Replacing the 7 nt U-turn loop within the anticodon and T stem-loop-stems also appears problematic. The 7 nt U-turn loop is a compact loop that projects a 3 nt anticodon. The 7 nt U-turn loop, furthermore, is expected to have resisted attack by ribozyme nucleases on pre-life Earth. The tight tRNA anticodon loop (see

Figure 3), therefore, appears to have been chemically selected versus competing loops on pre-life Earth. Also, 31 nt minihelices have longer stems than tRNAs (compare

Figure 9, lines 1-4 with lines 5-7). This suggests that there was a chemical advantage to folding into the more complex tRNA compared to minihelices. We posit that tRNAs were easier to melt and replicate on pre-life Earth than minihelices.

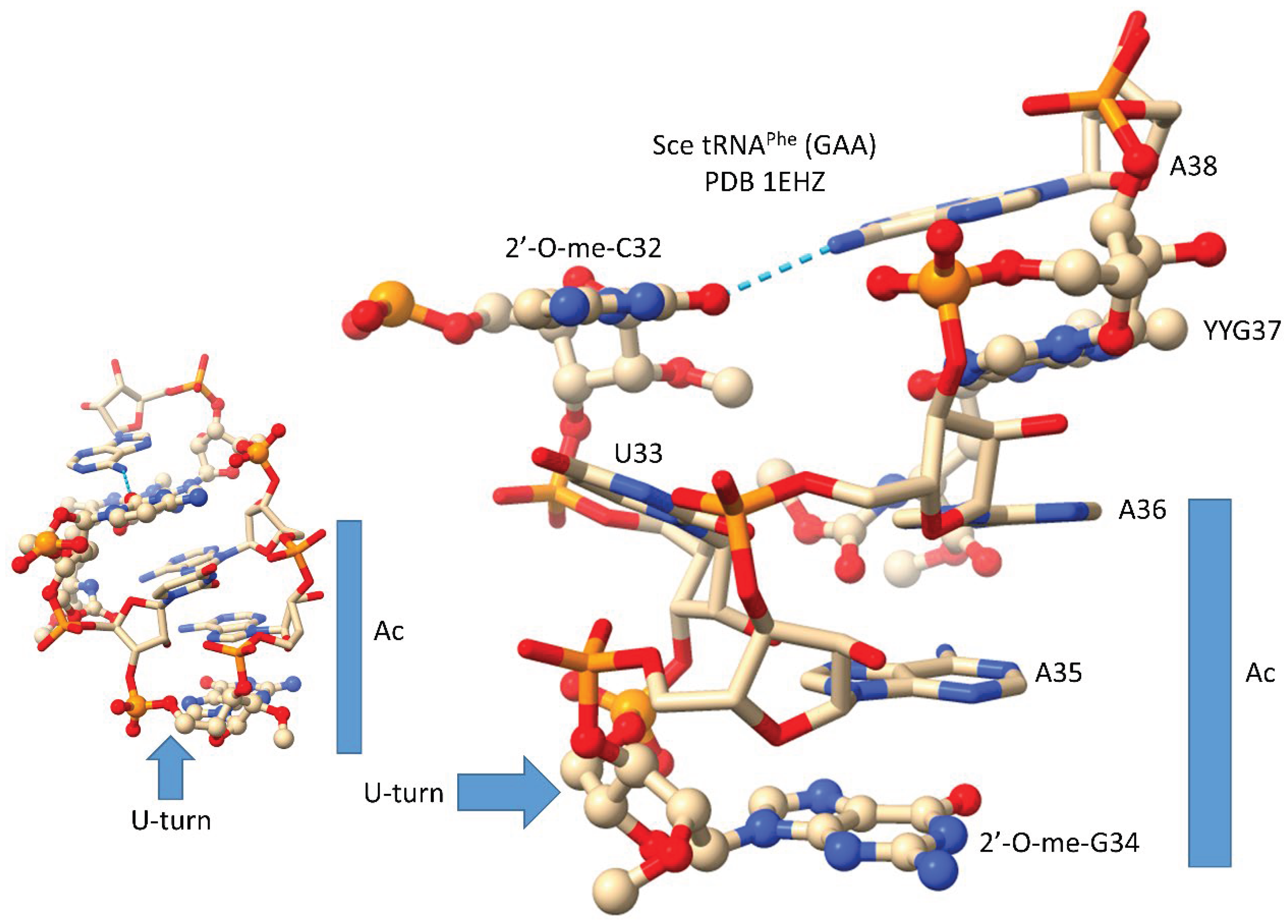

10. The Anticodon Loop as Essential Intellectual Property to Evolve Life on Earth

In

Figure 11, we show the anticodon loop of

Saccharomyces cerevisiae tRNA

Phe (GAA) (see also

Figure 3) [

24]. We argue that the compact 7 nt U-turn anticodon loop was necessary intellectual property to evolve life on planet Earth. Any attempt to substitute the loop with an RNA loop of another length or alternate sequence would probably be unsuccessful to evolve a code. The U-turn is a U-shaped turn in the anticodon loop backbone. A U-turn loop was necessary to form the tight and compact loop to resist ribozyme endonucleases in the pre-life world. The U-turn also projects three nucleotides to form the anticodon. We posit that, initially, both tRNA-34 and tRNA-36 were wobble positions [

1,

2,

3]. Wobbling at tRNA-36 was suppressed, in part, by modification of tRNA-37. In the tRNA

Phe (GAA) shown, tRNA-37 is modified to YYG (wybutosine; a G modification). At the base of code evolution, to read anticodon tRNA-36A, required a tRNA-37G modification (originally, 37m

1G). To read tRNA-36U required a tRNA-37A modification (originally, 37t

6A). With unmodified wobble U, tRNA-34U reads mRNA A, G, C and U. This is referred to as “superwobbling” and is utilized in mitochondria in 4-codon boxes to shrink the size of the organelle genetic code [

3,

33,

34]. To read tRNA-34U in the standard code, therefore, U must be modified to restrict its reading to mRNA wobble 3A and 3G. A first protein named elongator Elp3 evolved along with the genetic code to support use of tRNA-34U and to restrict its reading. tRNA-34A was not utilized at the base of code evolution. Numerous first proteins coevolved with tRNAomes and the genetic code to generate the first cells. Because 2’-O-me-C32 and 38A interact (a reverse Hoogsteen interaction), these bases stack with the anticodon stem. Wobbling at tRNA-36 was suppressed, but wobbling at tRNA-34 could not be suppressed in the same way. For one thing, tRNA-33U is on the other side of the U-turn from the anticodon, so modification of tRNA-33U would not alter the reading of tRNA-34. The anticodon loop has specialized properties, modifications and characteristics that could not easily be substituted by an alternate RNA loop.

11. Determinants on tRNA for Cognate Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetase Recognition

tRNAomes coevolved with the first proteins aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (AARS). Most tRNAs are type I. Only a small number can be type II. In Archaea, only tRNA

Leu and tRNA

Ser are type II. Leucine and serine are in 6-codon boxes in the standard genetic code. Having 5 tRNA

Leu and 4 tRNA

Ser presented a problem for cognate tRNA charging utilizing the anticodon loop as a determinant, as for most tRNAs. tRNA

Leu and tRNA

Ser, therefore, utilized their distinct type II V arms as a major determinant for accurate charging by LeuRS-IA (

Figure 1) and SerRS-IIA [

8]. Arginine is also within a 6-codon sector of the code, but tRNA

Arg is a type I tRNA (5 tRNAs). ArgRS-IA substantially unwinds the anticodon loop to expose additional bases for cognate recognition [

35]. GlyRS-IIA unwinds the tRNA

Gly anticodon loop (3 tRNAs) to expose tRNA-35-CCA-37 for recognition (

Figure 3) [

25]. Apparently, two strategies (type II V arm (Leu and Ser) and anticodon loop (Arg)) were necessary to support three amino acids in 6-codon boxes at the base of code evolution [

1]. Additional determinants are also utilized for cognate amino acid charging including: 1) tRNA-73 is the discriminator base, which can be A, G, U or C (initially A); 2) the acceptor stem; 3) the anticodon loop (for all amino acids except alanine, leucine and serine); 4) the type II V arm (for leucine and serine in Archaea); and 5) the elbow [

36,

37].

12. Dirty Polyglycine and Emulsification at the Origin of Life

When we consider polyglycine to emulsify pre-cell chemistries, we consider “dirty” polyglycine [

1]. That is to say that polyglycine was part of a background of complementary chemisties. Polyglycine can be modified in many ways on pre-life Earth to increase its length, cross-linking, hydrophilicity and charge. Many such modifications would potentially render polyglycine a better emulsifier of pre-life chemistry. We suggest that polyglycine be tested for its potential reactivity on pre-life Earth and for its promotion of the protocell to cell transitions.

13. Ribozymes and RNA in Pre-Life

Objections to an RNA world include the possible instability of RNA and some limited capacities of ribozymes to catalyze some necessary reactions. RNA that is modified at the 2’-O of the ribose ring, however, is as stable as DNA to base hydrolysis [

32]. For instance, 2’-O-methyl single-stranded RNAs and ribozymes would be stablized. RNA modifications are certainly more ancient than the genetic code because multiple tRNA modifications (i.e., Elp3 modification of U, m

1G, t

6A, C→agmatidine, 2’-O-meC) were necessary to generate the code [

1,

2]. Here, we advocate for a complex mod-RNA-amino acid-protein-metabolism world [

32] (mod-RNA for modified RNA). Our view is supported by analysis of tRNA, tRNAome and genetic code evolution.

14. The Three 31 nt Minihelix tRNA Evolution Theorem

There are no theorems (proven models) in biology, but the three 31 nt minihelix tRNA evolution theorem is very close to a proven model. If there is a rational objection to the theorem, we are not aware of it. There have been other tRNA evolution models, but none can be correct [

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51]. No convergent or accretion model can be correct, because, at the origin of tRNAomes, all tRNAs are homologous along their entire length. Only a divergent model can be adequate for tRNA evolution. tRNAs evolved from a 93 nt precursor that was processed differentially for type II and type I tRNAs. All tRNAs in the tRNAsphere radiated from these forms. No other model can account for internal tRNA homologies. No other model can account for the RNA 3 nt (GCG and CGC) and 5 nt (UAGCC) repeats in tRNA or the conserved inverted repeats (initially ~CCGGG_CU/GCCAA_CCCGG; anticodon and T stem-loop-stems). We posit that tRNA is the most strongly conserved sequence for the pre-life to complex life transition. As such, tRNA sequence provides a powerful gateway to understand the transition on Earth to complex life. The three 31 nt tRNA evolution theorem is strongly supported by statistical analyses [

7,

10,

26], and most of its features can readily be confirmed by inspection of conserved sequence. We advocate for the universal acceptance of the three 31 nt minihelix tRNA evolution theorem.

15. Discussion

tRNA is the most highly conserved sequence from pre-life. tRNA was generated from RNA repeats and inverted repeats of known sequence. ACCA-Gly was the primitive adapter molecule. tRNA evolved initially to synthesize polyglycine. We posit that polyglycine was selected chemically in pre-life for two reasons: 1) polyglycine emulsified pre-cellular components; and 2) polyglycine helped form the first protocells and cells [

1]. After polyglycine, the genetic code evolved to synthesize GADV polymers [

52,

53]. At an 8 amino acid stage, the code may have been GADVLSER [

1,

3,

4]. Amino acid-linked chemistry can generate D→N, E→Q and S→C to generate an 11 amino acid stage of code evolution [

1,

3,

4,

54]. Suppression of tRNA-36 wobbling allowed the code to expand to 20 amino acids and stops. Fidelity mechanisms froze the code. Because the type II tRNA V arm is a determinant for cognate tRNA charging, only a small number of type II tRNAs are utilized [

8]. We posit that, originally, tRNAs were a mixture of type I and type II that were sorted later in evolution.

We have taken a top-down, sequence-based approach to the origin of life. A bottom-up approach would be to reproduce pre-life chemistry in a laboratory [

55]. When top-down strategies meet bottom-up approaches, an adequate understanding of the pre-life to life transition should emerge. We were surprised at how powerful the top-down strategy proved to be. We were surprised that tRNA sequences were so highly ordered and related such a reliable history of the pre-life to life transition on Earth.

tRNA structure and function are core lessons in biochemistry, biology and genetics. Incorporating evolution of tRNA and coding will improve science education. For tRNA databases, we advocate for a version of our presentation shown here to further advance the core importance of tRNA and coding evolution at the inception of biology.

Author Contributions

ZFB and LL wrote the paper and prepared the figures.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AARS |

Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase (ligase) |

| LUCA |

Last Universal Common (Cellular) Ancestor |

| Elp3 |

Elongator Protein 3 |

| Indel |

Insertions and Deletions |

References

- Lei, L.; Burton, Z.F. Chemical Evolution of Life on Earth. Genes (Basel) 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, L.; Burton, Z.F. The 3 31 Nucleotide Minihelix tRNA Evolution Theorem and the Origin of Life. Life (Basel) 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, L.; Burton, Z.F. "Superwobbling" and tRNA-34 Wobble and tRNA-37 Anticodon Loop Modifications in Evolution and Devolution of the Genetic Code. Life (Basel) 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, L.; Burton, Z.F. Evolution of the genetic code. Transcription 2021, 12, 28–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Burton, Z.F. Evolution of Life on Earth: tRNA, Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetases and the Genetic Code. Life (Basel) 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Opron, K.; Burton, Z.F. A tRNA- and Anticodon-Centric View of the Evolution of Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetases, tRNAomes, and the Genetic Code. Life (Basel) 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kowiatek, B.; Opron, K.; Burton, Z.F. Type-II tRNAs and Evolution of Translation Systems and the Genetic Code. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Burton, Z.F. Origin of Type II tRNA Variable Loops, Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetase Allostery from Distal Determinants, and Diversification of Life. DNA 2024, 4, 252–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, Z.F. The 3-Minihelix tRNA Evolution Theorem. J Mol Evol 2020, 88, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pak, D.; Root-Bernstein, R.; Burton, Z.F. tRNA structure and evolution and standardization to the three nucleotide genetic code. Transcription 2017, 8, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Root-Bernstein, R.; Kim, Y.; Sanjay, A.; Burton, Z.F. tRNA evolution from the proto-tRNA minihelix world. Transcription 2016, 7, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, P.P.; Lowe, T.M. GtRNAdb 2.0: an expanded database of transfer RNA genes identified in complete and draft genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 2016, 44, D184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, T.; Inokuchi, H.; Yamada, Y.; Muto, A.; Iwasaki, Y.; Ikemura, T. tRNADB-CE: tRNA gene database well-timed in the era of big sequence data. Front Genet 2014, 5, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, T.; Ikemura, T.; Sugahara, J.; Kanai, A.; Ohara, Y.; Uehara, H.; Kinouchi, M.; Kanaya, S.; Yamada, Y.; Muto, A.; et al. tRNADB-CE 2011: tRNA gene database curated manually by experts. Nucleic Acids Res 2011, 39, D210–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, T.; Ikemura, T.; Ohara, Y.; Uehara, H.; Kinouchi, M.; Kanaya, S.; Yamada, Y.; Muto, A.; Inokuchi, H. tRNADB-CE: tRNA gene database curated manually by experts. Nucleic Acids Res 2009, 37, D163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burley, S.K.; Piehl, D.W.; Vallat, B.; Zardecki, C. RCSB Protein Data Bank: supporting research and education worldwide through explorations of experimentally determined and computationally predicted atomic level 3D biostructures. IUCrJ 2024, 11, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bittrich, S.; Bhikadiya, C.; Bi, C.; Chao, H.; Duarte, J.M.; Dutta, S.; Fayazi, M.; Henry, J.; Khokhriakov, I.; Lowe, R.; et al. RCSB Protein Data Bank: Efficient Searching and Simultaneous Access to One Million Computed Structure Models Alongside the PDB Structures Enabled by Architectural Advances. J Mol Biol 2023, 435, 167994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burley, S.K.; Bhikadiya, C.; Bi, C.; Bittrich, S.; Chao, H.; Chen, L.; Craig, P.A.; Crichlow, G.V.; Dalenberg, K.; Duarte, J.M.; et al. RCSB Protein Data Bank (RCSB.org): delivery of experimentally-determined PDB structures alongside one million computed structure models of proteins from artificial intelligence/machine learning. Nucleic Acids Res 2023, 51, D488–D508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, E.C.; Goddard, T.D.; Pettersen, E.F.; Couch, G.S.; Pearson, Z.J.; Morris, J.H.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF ChimeraX: Tools for structure building and analysis. Protein Sci 2023, 32, e4792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Meng, E.C.; Couch, G.S.; Croll, T.I.; Morris, J.H.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF ChimeraX: Structure visualization for researchers, educators, and developers. Protein Sci 2021, 30, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Meng, E.C.; Pettersen, E.F.; Couch, G.S.; Morris, J.H.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF ChimeraX: Meeting modern challenges in visualization and analysis. Protein Sci 2018, 27, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukunaga, R.; Yokoyama, S. Aminoacylation complex structures of leucyl-tRNA synthetase and tRNALeu reveal two modes of discriminator-base recognition. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2005, 12, 915–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukunaga, R.; Yokoyama, S. Crystal structure of leucyl-tRNA synthetase from the archaeon Pyrococcus horikoshii reveals a novel editing domain orientation. J Mol Biol 2005, 346, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Moore, P.B. The crystal structure of yeast phenylalanine tRNA at 1.93 A resolution: a classic structure revisited. RNA 2000, 6, 1091–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Deng, X.; Chen, L.; Xie, W. Crystal Structure of the Wild-Type Human GlyRS Bound with tRNA(Gly) in a Productive Conformation. J Mol Biol 2016, 428, 3603–3614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pak, D.; Du, N.; Kim, Y.; Sun, Y.; Burton, Z.F. Rooted tRNAomes and evolution of the genetic code. Transcription 2018, 9, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, N.; Joyce, G.F. A self-replicating ligase ribozyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002, 99, 12733–12740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakoti, A.; Joyce, G.F. RNA Polymerase Ribozyme That Recognizes the Template-Primer Complex through Tertiary Interactions. Biochemistry 2023, 62, 1916–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjhung, K.F.; Shokhirev, M.N.; Horning, D.P.; Joyce, G.F. An RNA polymerase ribozyme that synthesizes its own ancestor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117, 2906–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samanta, B.; Horning, D.P.; Joyce, G.F. 3'-End labeling of nucleic acids by a polymerase ribozyme. Nucleic Acids Res 2018, 46, e103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horning, D.P.; Joyce, G.F. Amplification of RNA by an RNA polymerase ribozyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016, 113, 9786–9791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller, F.; Escobar, L.; Xu, F.; Wegrzyn, E.; Nainyte, M.; Amatov, T.; Chan, C.Y.; Pichler, A.; Carell, T. A prebiotically plausible scenario of an RNA-peptide world. Nature 2022, 605, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkatib, S.; Scharff, L.B.; Rogalski, M.; Fleischmann, T.T.; Matthes, A.; Seeger, S.; Schottler, M.A.; Ruf, S.; Bock, R. The contributions of wobbling and superwobbling to the reading of the genetic code. PLoS Genet 2012, 8, e1003076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogalski, M.; Karcher, D.; Bock, R. Superwobbling facilitates translation with reduced tRNA sets. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2008, 15, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephen, P.; Ye, S.; Zhou, M.; Song, J.; Zhang, R.; Wang, E.D.; Giege, R.; Lin, S.X. Structure of Escherichia coli Arginyl-tRNA Synthetase in Complex with tRNA(Arg): Pivotal Role of the D-loop. J Mol Biol 2018, 430, 1590–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giege, R.; Eriani, G. The tRNA identity landscape for aminoacylation and beyond. Nucleic Acids Res 2023, 51, 1528–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawfik, D.S.; Gruic-Sovulj, I. How evolution shapes enzyme selectivity - lessons from aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases and other amino acid utilizing enzymes. FEBS J 2020, 287, 1284–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demongeot, J.; Seligmann, H. Evolution of small and large ribosomal RNAs from accretion of tRNA subelements. Biosystems 2022, 222, 104796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demongeot, J.; Seligmann, H. Codon assignment evolvability in theoretical minimal RNA rings. Gene 2021, 769, 145208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giulio, M. An RNA Ring was Not the Progenitor of the tRNA Molecule. J Mol Evol 2020, 88, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demongeot, J.; Seligmann, H. Theoretical minimal RNA rings mimick molecular evolution before tRNA-mediated translation: codon-amino acid affinities increase from early to late RNA rings. C R Biol 2020, 343, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demongeot, J.; Seligmann, H. RNA Rings Strengthen Hairpin Accretion Hypotheses for tRNA Evolution: A Reply to Commentaries by Z.F. Burton and M. Di Giulio. J Mol Evol 2020, 88, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demongeot, J.; Seligmann, H. The primordial tRNA acceptor stem code from theoretical minimal RNA ring clusters. BMC Genet 2020, 21, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demongeot, J.; Seligmann, H. The Uroboros Theory of Life's Origin: 22-Nucleotide Theoretical Minimal RNA Rings Reflect Evolution of Genetic Code and tRNA-rRNA Translation Machineries. Acta Biotheor 2019, 67, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Giulio, M. A polyphyletic model for the origin of tRNAs has more support than a monophyletic model. J Theor Biol 2013, 318, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Giulio, M. The 'recently' split transfer RNA genes may be close to merging the two halves of the tRNA rather than having just separated them. J Theor Biol 2012, 310, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giulio, M. The origin of the tRNA molecule: Independent data favor a specific model of its evolution. Biochimie 2012, 94, 1464–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branciamore, S.; Di Giulio, M. The presence in tRNA molecule sequences of the double hairpin, an evolutionary stage through which the origin of this molecule is thought to have passed. J Mol Evol 2011, 72, 352–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giulio, M. Transfer RNA genes in pieces are an ancestral character. EMBO Rep 2008, 9, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widmann, J.; Di Giulio, M.; Yarus, M.; Knight, R. tRNA creation by hairpin duplication. J Mol Evol 2005, 61, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giulio, M. The origin of the tRNA molecule: implications for the origin of protein synthesis. J Theor Biol 2004, 226, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikehara, K. Why Were [GADV]-amino Acids and GNC Codons Selected and How Was GNC Primeval Genetic Code Established? Genes (Basel) 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikehara, K. [GADV]-protein world hypothesis on the origin of life. Orig Life Evol Biosph 2014, 44, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehbi, S.; Wheeler, A.; Morel, B.; Manepalli, N.; Minh, B.Q.; Lauretta, D.S.; Masel, J. Order of amino acid recruitment into the genetic code resolved by last universal common ancestor's protein domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2024, 121, e2410311121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikehara, K. Evolutionary Steps in the Emergence of Life Deduced from the Bottom-Up Approach and GADV Hypothesis (Top-Down Approach). Life (Basel) 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).