Submitted:

11 August 2025

Posted:

13 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Experimental Models.

2.2. Obtaining Nerve Samples.

2.3. Sampling Other Organs.

2.4. Assays for LP and Protein Carbonyl Groups.

2.5. Estimation of DNA Synthesis and Compensatory Cell Proliferation During Wallerian Degeneration of the Sciatic Nerve

2.6. Assessment of Apoptosis.

2.7. Determination of Redox-Pair Cytosolic Metabolites, NO Metabolism and Activity of Cytochrome Oxidase

2.8. Calculations and Statistics

3. Results

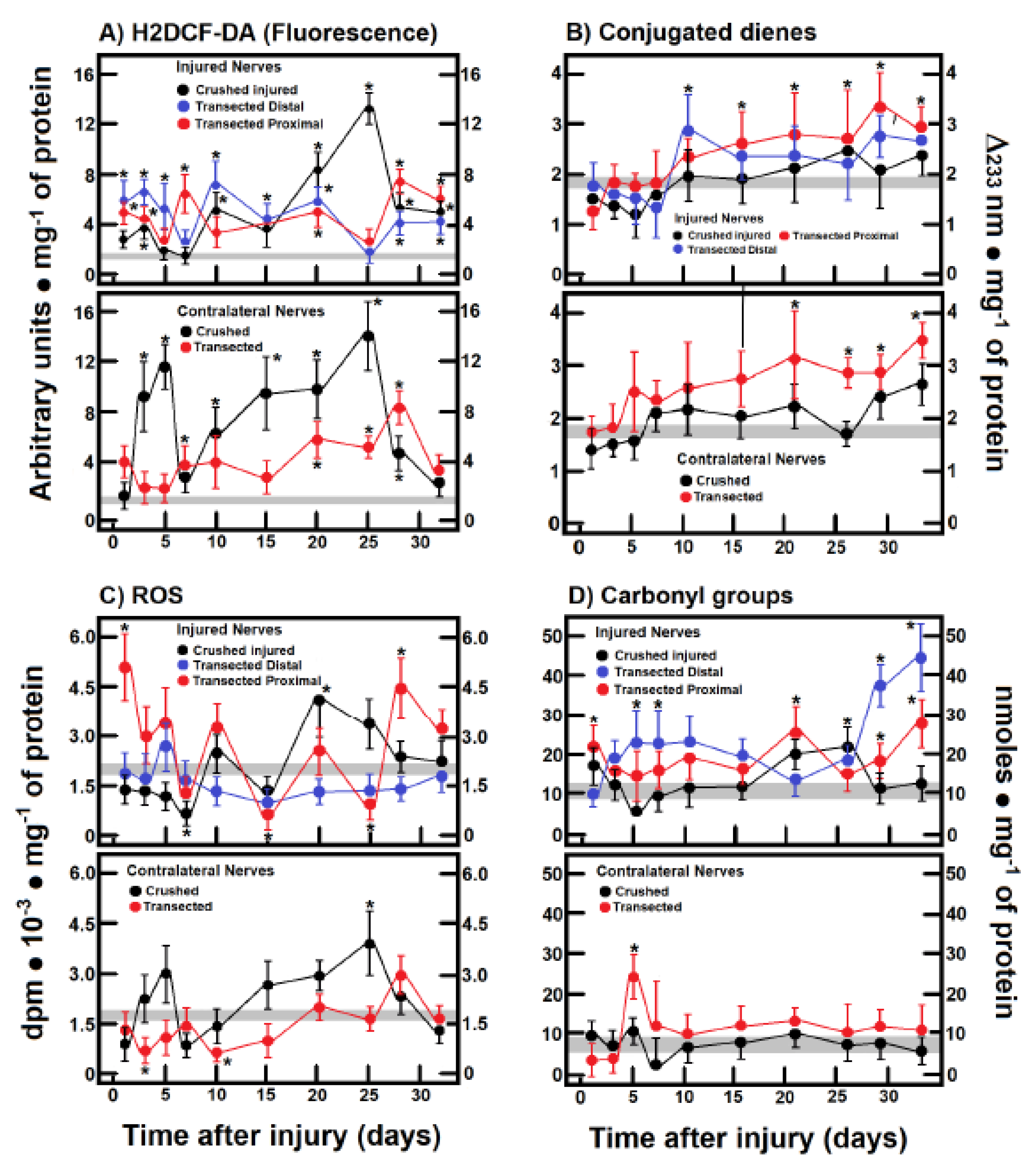

3.1. Production of ROS By-Products and Conjugated Dienes in the Injured Sciatic Nerve After Crushing or Transection

3.2. H2DCF-DA Reacting By-Products Content in Other Tissues During Wallerian Degeneration of Crushed Nerves

3.3. Production of Free Radicals Detected by Chemiluminescence in Crushed or Transected Sciatic Nerves

3.4. Rate of Protein Oxidation (Carbonyl Groups) in Crushed or Transected Nerves

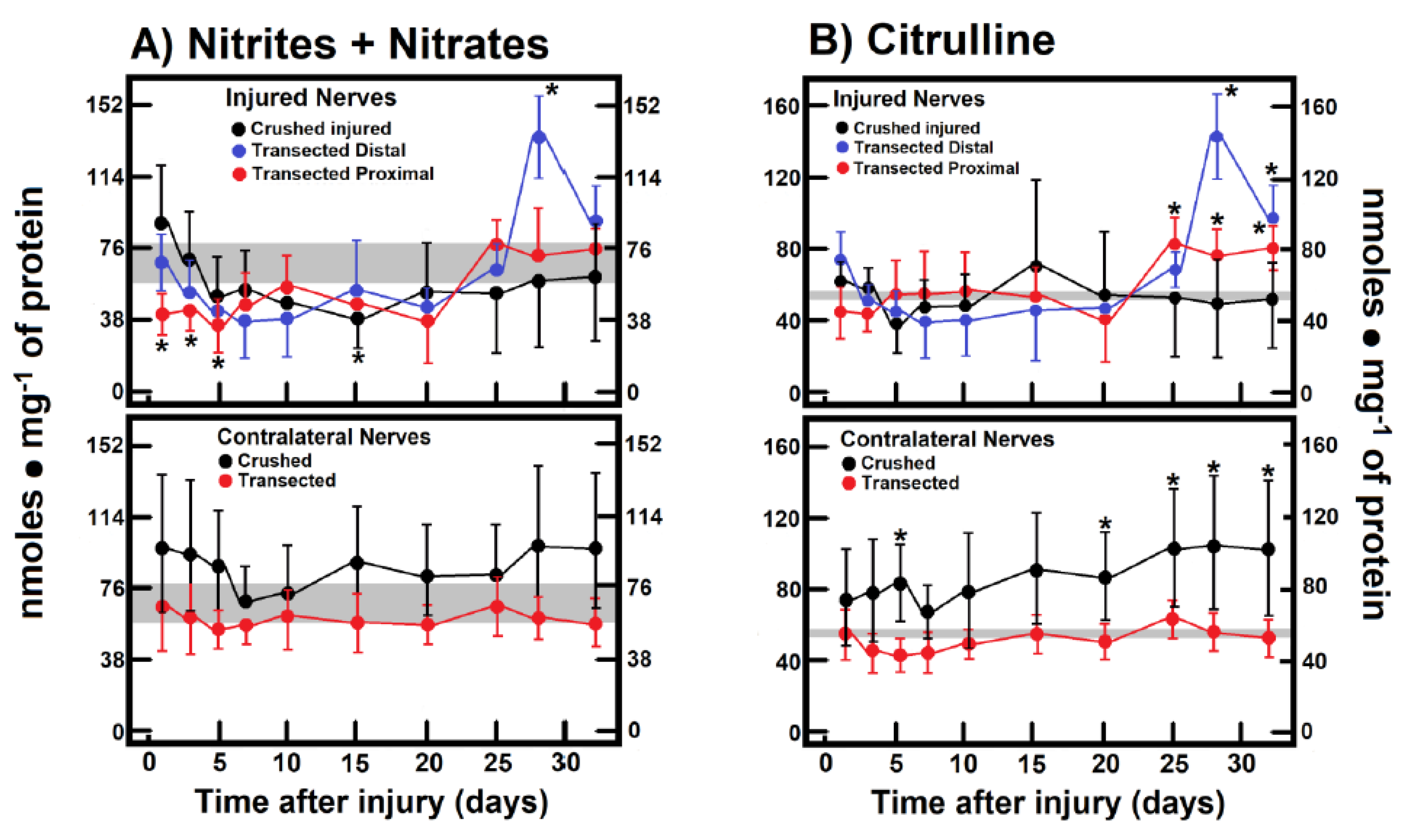

3.5. NO Metabolism in Crushed and Transected Sciatic Nerves

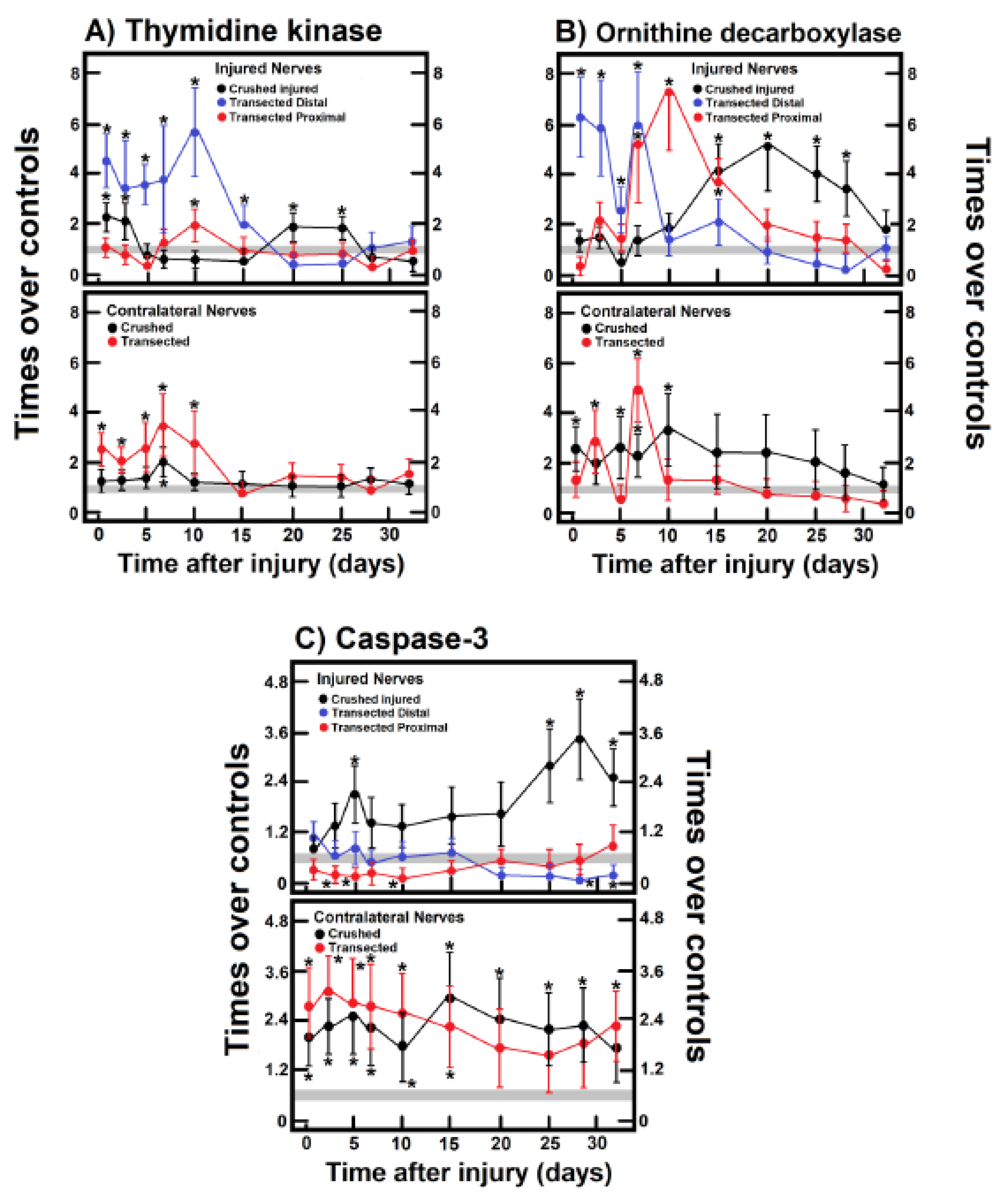

3.6. Parameters Indicative of Cell Proliferation in Crushed and Transected Sciatic Nerves

3.7. Activity of Caspase-3 in the Injured Sciatic Nerve After Crushing or Transection

3.8. Changes in the Cell Redox State (Cytoplasmic) in the Injured Sciatic Nerve After Crushing or Transection

3.9. Mitochondrial Cytochrome Oxidase Activity in the Injured Sciatic Nerve After Crushing or Transection

3.10. Parameters Are Indicative of Oxidant Stress, Proliferation and Apoptosis in Leg Muscles After Crushing the Right Sciatic Nerve

3.11. Correlations Among Parameters Indicative of Oxidant Stress, Cell Proliferation, Apoptosis, and Onset of Mitochondrial Biogenesis in Crushed and Transected Sciatic Nerves with Their Respective Contralateral Nerves

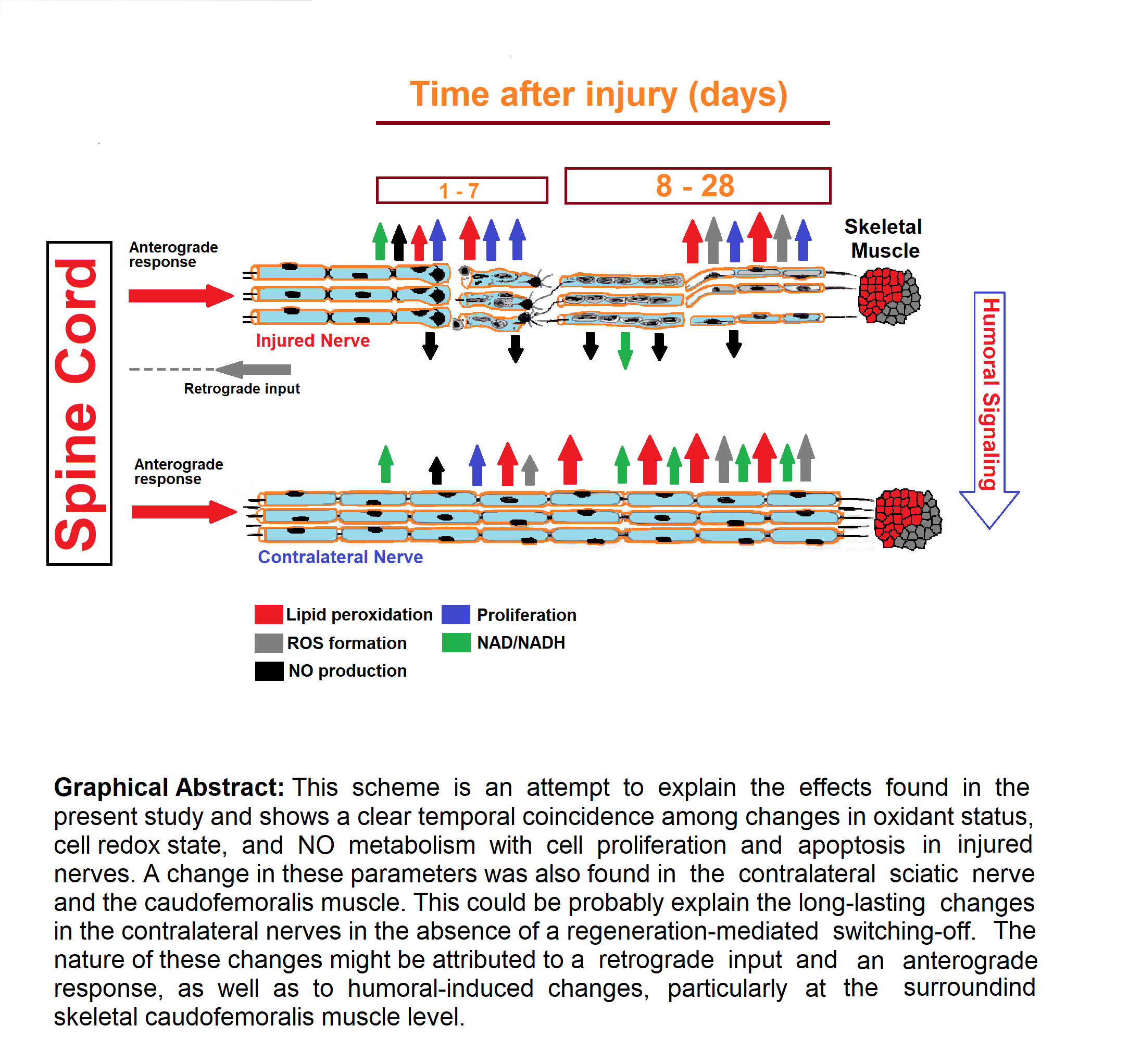

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Faroni, A.; Mobasseri, S.A.; Kingham, P.J.; Reid, A.J. Peripheral nerve regeneration: experimental strategies and future perspectives. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2015, 82-83, 160-167. [PubMed: 25446133]. [CrossRef]

- Ide, C. Peripheral nerve regeneration. Neurosci. Res. 1996, 25, 101–121, [PubMed: 8829147].. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jessen, K.R.; Mirsky, R. The repair Schwann cell and its function in regenerating nerves. J. Physiol. 2016, 594, 3521–3531, [PubMed: 26864683]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricaud, N.; Park, H.T. Wallerian demyelination: chronicle of a cellular cataclysm. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2017, 74, 4049–4057, [PubMed: 28600652]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoll, G.; Griffin, J.W.; Li, C.Y.; Trapp, B.D. Wallerian degeneration in the peripheral nervous system: participation of both Schwann cells and macrophages in myelin degradation. J. Neurocytol. 1989, 18, 671–683, [PubMed: 2614485]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Piao, X.; Bonaldo, P. Role of macrophages in Wallerian degeneration and axonal regeneration after peripheral nerve injury. Acta Neuropathol. 2015, 130, 605–618, [PubMed: 26419777]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, H.C.; Köhne, A.; Meyer zu Hörste, G.; Dehmel, T.; Kiehl, O.; Hartung, H.P.; Kastenbauer, S.; Kieseier, B.C. Role of nitric oxide as mediator of nerve injury in inflammatory neuropathies. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2007, 66, 305–312, [PubMed: 17413321]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panthi, S.; Gautam, K. Roles of nitric oxide and ethyl pyruvate after peripheral nerve injury. Inflamm. Regen. 2017, 2;37:20. [PubMed: 29259719].

- Levy, D.; Kubes, P.; Zochodne, D.W. Delayed peripheral nerve degeneration, regeneration, and pain in mice lacking inducible nitric oxide synthase. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2001, 60, 411–421, [PubMed: 11379816]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keilhoff, G.; Fansa, H.; Wolf, G. Differences in peripheral nerve degeneration/regeneration between wild-type and neuronal nitric oxide synthase knockout mice. J. Neurosci. Res. 2002, 68, 432–441, [PubMed: 11992469]. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, K.J.; Kapoor, R. Felts; P.A. Demyelination: the role of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. Brain Pathol. 1999, 9, 69–92, [PubMed: 9989453]. [Google Scholar]

- Zochodne, D.W.; Misra, M.; Cheng, C.; Sun, H. Inhibition of nitric oxide synthase enhances peripheral nerve regeneration in mice. Neurosci. Lett. 1997, 228, 71–4, [PubMed: 9209101]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecchini, T.; Cuppini, R.; Ciaroni, S.; Del Grande, P. Effect of vitamin E-deficiency on regeneration of the sciatic nerve. Arch. Ital. Anat. Embriol. 1990, 95, 155–165, [PubMed: 2078094]. [Google Scholar]

- Cuppini, R.; Cecchini, T.; Ciaroni, S.; Ambrogini, P.; Del Grande, P. Nodal and terminal sprouting by regenerating nerve in vitamin E-deficient rats. J. Neurol. Sci. 1993, 117, 61–67, [PubMed: 8410068]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayan, H.; Ugurlu, B.; Babül, A.; Take, G.; Erdogan, D. Effects of L-arginine and NG-nitro L-arginine methyl ester on lipid peroxide, superoxide dismutase and nitrate levels after experimental sciatic nerve ischemia-reperfusion in rats. Int. J. Neurosci. 2004, 114, 349–364, [PubMed: 14754660]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrera, G.; Pizzimenti, S.; Dianzani, M.U. Lipid peroxidation: control of cell proliferation, cell differentiation and cell death. Mol. Aspects Med. 2008, 29, 1–8, [PubMed: 18037483]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara-Ramírez, R.; Segura-Anaya, E.; Martínez-Gómez, A.; Dent, M.A.R. Expression of interleukin-6 receptor alpha in normal and injured rat sciatic nerve. Neuroscience 2008, 152, 601–608, [PubMed: 18313228]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viarengo, A.; Burlando, B.; Cavaletto, M.; Marchi, B.; Ponzano, E.; Blasco, J. Role of metallothionein against oxidative stress in the mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis. Am. J. Physiol. 1999, 277, R1612–1619, [PubMed: 10600906]. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Muñoz, R.; Montiel-Ruíz, C.; Vázquez-Martínez, O. Gastric mucosal cell proliferation in ethanol-induced chronic mucosal injury is related to oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation in rats. Lab. Invest. 2000, 80, 1161–1169, [PubMed: 10950107]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadenas, E.; Sies, H. Low-level chemiluminescence as an indicator of singlet molecular oxygen in biological systems. Methods Enzymol. 1984, 5, 221–231, [PubMed: 6328183]. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, R.L.; Garland, D.; Oliver, C.N.; Amici, A.; Climent, I.; Lenz, A.G.; Ahn, B.W.; Shaltiel, S.; Stadtman, E.R. Determination of carbonyl content in oxidatively modified proteins. Methods Enzymol. 1990, 186, 464–478, [PubMed: 1978225]. [Google Scholar]

- Sauer, H.; Wilmanns, H. Thymidine kinase. In: Bermeyer H. U., ed. Methods of Enzymatic Analysis, Vol. 3. Deerfield Beach, FL: VCH, 1985, pp. 468-473.

- Diehl, A.M.; Wells, M.; Brown, N.D.; Thorgeirsson, S.S.; Steer, C.J. Effect of ethanol on polyamine synthesis during liver regeneration in rats. J. Clin. Invest. 1990, 85, 385–390, [PubMed: 2298913]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornberry, N.A. Interleukin-1 beta converting enzyme. Methods Enzymol. 1994, 244, 615–631, [PubMed: 7845238]. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Olguín-Martínez, M.; Hernández-Espinosa, D.R.; Hernández-Muñoz, R. α-Tocopherol administration blocks adaptive changes in cell NADH/NAD+ redox state and mitochondrial function leading to inhibition of gastric mucosa cell proliferation in rats. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 65, 1090–1100, [PubMed: 23994576]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez-Zamora, S.; Méndez-Rodríguez, M.L.; Olguín-Martínez, M.; Sánchez-Sevilla, L.; Quintana-Quintana, M.; García-García, N.; Hernández-Muñoz, R. Increased erythrocytes by-products of arginine catabolism are associated with hyperglycemia and could be involved in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus. PLoS One. 2013, 24;8(6):e66823. [PubMed: 23826148].

- Stubbs, M.; Veech, R.L.; Krebs, H.A. Control of the redox state of the nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide couple in rat liver cytoplasm. Biochem. J. 1972, 126, 59–65, [PubMed: 4342386]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkins, H.M.; Harris, J.L.; Carl, S.M.; Lezi, E.; Lu, J.; Eva Selfridge, J.; Roy, N.; Hutfles, L.; Koppel, S.; Morris, J.; Burns, J.M.; Michaelis, M.L.; Michaelis, E.K.; Brooks, W.M.; Swerdlow, R.H. Oxaloacetate activates brain mitochondrial biogenesis, enhances the insulin pathway, reduces inflammation and stimulates neurogenesis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014, 23, 6528–6541, [PubMed: 25027327]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheeseman, K.H.; Collins, M.; Maddix, S.; Milia, A.; Proudfoot, K.; Slater, T.F.; Burton, G.W.; Webb, A.; Ingold, K.U. Lipid peroxidation in regenerating rat liver. FEBS Lett. 1986, 209, 191–196, [PubMed: 3098579]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alison, M.R. Regulation of hepatic growth. Physiol. Rev. 1986, 66, 499–541, [PubMed: 2426724]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, K.R.; Barrett, J.C. Reactive oxygen species as double-edged swords in cellular processes: low-dose cell signaling versus high-dose toxicity. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2002, 21, 71–75, [PubMed: 12102499]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdon, R.H. Superoxide and hydrogen peroxide in relation to mammalian cell proliferation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1995, 18, 775–794, [PubMed: 7750801]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuppini, R.; Ciaroni, S.; Cecchini, T.; Ambrogini, P.; Ferri, P.; Del Grande, P.; Papa, S. Alpha-tocopherol controls cell proliferation in the adult rat dentate gyrus. Neurosci. Lett. 2001, 303, 198–200, [PubMed: 11323119]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuzil, J.; Zhao, M.; Ostermann, G.; Sticha, M.; Gellert, N.; Weber, C.; Eaton, J.W.; Brunk, U.T. Alpha-tocopheryl succinate, an agent with in vivo anti-tumour activity, induces apoptosis by causing lysosomal instability. Biochem. J. 2002, 362, 709–715, [PubMed: 11879199]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Delfín, I.; López-Barrera, F.; Hernández-Muñoz, R. Selective enhancement of lipid peroxidation in plasma membrane in two experimental models of liver regeneration: partial hepatectomy and acute CC14 administration. Hepatology 1996, 24, 657–662, [PubMed: 8781339]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trejo-Solís, C.; Chagoya De Sánchez, V.; Aranda-Fraustro, A.; Sánchez-Sevilla, L.; Gómez-Ruíz, C.; Hernández-Muñoz, R. Inhibitory effect of vitamin e administration on the progression of liver regeneration induced by partial hepatectomy in rats. Lab. Invest. 2003, 83, 1669–1679, [PubMed: 14615420]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, M.; Matsuoka, I.; Wetmore, C.; Olson, L.; Thoenen, H. Enhanced synthesis of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the lesioned peripheral nerve: different mechanisms are responsible for the regulation of BDNF and NGF mRNA. J. Cell Biol. 1992, 119, 45–54, [PubMed: 1527172]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zawia, N.H.; Harry, G.J. Correlations between developmental ornithine decarboxylase gene expression and enzyme activity in the rat brain. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 1993, 71, 53–57, [PubMed: 8431999]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilad, G.M.; Gilad, V.H.; Eliyayev, Y.; Rabey, J.M. Developmental regulation of the brain polyamine-stress-response. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 1998, 16, 271–278, [PubMed: 9785123]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilad, G.M.; Gilad, V.H. Reciprocal regulation of ornithine decarboxylase and choline kinase activities by their respective reaction products in the developing rat cerebellar cortex. J. Neurochem. 1984, 43, 1538–1543, [PubMed: 6092541]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulraj, R.; Behari, J. Biochemical changes in rat brain exposed to low intensity 9. 9 GHz microwave radiation. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2012, 63, 97–102, [PubMed: 22426826]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, K.; Packianathan, S.; Longo, L.D. Free radical-induced elevation of ornithine decarboxylase activity in developing rat brain slices. Brain Res. 1997, 763, 232–238, [PubMed: 9296564]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, N.K.; MacLean, H.E. Polyamines, androgens, and skeletal muscle hypertrophy. J. Cell Physiol. 2011, 226, 1453–1460, [PubMed: 21413019]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zochodne, D.W.; Levy, D. Nitric oxide in damage, disease and repair of the peripheral nervous system. Cell Mol. Biol. (Noisy-le-grand). 2005, 51, 255–267, [PubMed: 16191393]. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborti, S.; Mandal, M.; Das, S.; Mandal, A.; Chakraborti, T. Regulation of matrix metalloproteinases: an overview. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2003, 253, 269–285, [PubMed: 14619979]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conti, G.; Rostami, A.; Scarpini, E.; Baron, P.; Galimberti, D.; Bresolin, N.; Contri, M.; Palumbo, C.; De Pol, A. Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in immune-mediated demyelination and Wallerian degeneration of the rat peripheral nervous system. Exp. Neurol. 2004, 187, 350–358, [PubMed: 15144861]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Shin, T. Expression of constitutive endothelial and inducible nitric oxide synthase in the sciatic nerve of Lewis rats with experimental autoimmune neuritis. J. Neuroimmunol. 2002, 126, 78–85, [PubMed: 12020959]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Förstermann, U.; Sessa, W.C. Nitric oxide synthases: regulation and function. Eur. Heart J. 2012, 33, 829–837, [PubMed: 21890489]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jegatheesan, P.; De Bandt, J.P. Hepatic steatosis: a role for citrulline. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2016, 19, :360–365, [PubMed: 27380311]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, X.; Vivó, M. Valero-Cabré; A Neural plasticity after peripheral nerve injury and regeneration. Prog. Neurobiol. 2007, 82, 163–201, [PubMed: 17643733]. [Google Scholar]

- Stoll, G.; Müller, HW. Nerve injury, axonal degeneration and neural regeneration: basic insights. Brain Pathol. 1999, 9, 313–325, [PubMed: 10219748]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirata, H.; Hibasami, H.; Hineno, T.; Shi, D.; Morita, A.; Inada, H.; Fujisawa, K.; Nakashima, K.; Ogihara, Y. Role of ornithine decarboxylase in proliferation of Schwann cells during Wallerian degeneration and its enhancement by nerve expansion. Muscle Nerve 1995, 18, 1341–1343, [PubMed: 7565936]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, A.N.; Fan, T.W. Regulation of mammalian nucleotide metabolism and biosynthesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43:2466-2485. [PubMed: 25628363].

- Tran, D.H.; Kim, D.; Kesavan, R.; Brown, H.; Dey, T.; Soflaee, M.H.; Vu, H.S.; Tasdogan, A.; Guo, J.; et al. De novo and salvage purine synthesis pathways across tissues and tumors. Cell 2024, 187, 3602–3618, [PubMed: 38823389]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirata, H.; Hibasami, H.; Yoshida, T.; Morita, A.; Ohkaya, S.; Matsumoto, M.; Sasaki, H.; Uchida, A. Differentiation and apoptosis without DNA fragmentation in cultured Schwann cells derived from Wallerian-degenerated nerve. Apoptosis 1998, Oct;3(5):353-360. [PubMed: 14646482].

- Raff, M.C.; Whitmore, A.V.; Finn, J.T. Axonal self-destruction and neurodegeneration. Science 2002, 296(5569), 868-871. [PubMed: 11988563].

- Koltzenburg, M.; Wall, P.D.; McMahon, S.B. Does the right side know what the left is doing? Trends Neurosci. 1999, 22, 122–127, [PubMed: 10199637]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oaklander, A.L.; Brown, J.M. Unilateral nerve injury produces bilateral loss of distal innervation. Ann. Neurol. 2004, 55, 639–644, [PubMed: 15122703]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubový, P.; Tucková, L.; Jancálek, R.; Svízenská, I.; Klusáková, I. Increased invasion of ED-1 positive macrophages in both ipsi- and contralateral dorsal root ganglia following unilateral nerve injuries. Neurosci. Lett. 2007, 427, 88–93, [PubMed: 17931774]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozin, F.; Genant, H.K.; Bekerman, C.; McCarty, D.J. The reflex sympathetic dystrophysyndrome. II. Roentgenographic and scintigraphic evidence of bilaterality and of periarticular accentuation. Am. J Med. 1976, 60, 332–338, [PMID: 56892]. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas-Ruiz, F.; Galindo-Romero, C.; Albaladejo-García, V.; Vidal-Sanz, M.; Agudo-Barriuso, M. Mechanisms implicated in the contralateral effect in the central nervous system after unilateral injury: focus on the visual system. Neural Regen. Res. 2021, 16, 2125–2131, [PubMed: 33818483]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.S.; Xie, K.Q.; Zhang, C.L.; Zhu, Y.J.; Zhang, LP.; Guo, X.; Yu, S.F. Allyl chloride-induced time dependent changes of lipid peroxidation in rat nerve tissue. Neurochem. Res. 2005, 30, 1387–1395, [PubMed: 16341935]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Kaundal, R.K.; Iyer, S.; Sharma, S.S. Effects of resveratrol on nerve functions, oxidative stress and DNA fragmentation in experimental diabetic neuropathy. Life Sci. 2007, 80, 1236–1244, [PubMed: 17289084]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araki, T.; Sasaki, Y.; Milbrandt, J. Increased nuclear NAD biosynthesis and SIRT1 activation prevent axonal degeneration. Science 2004, 305(5686), 1010-1013. [PubMed: 15310905].

- Mack, T.G.; Reiner, M.; Beirowski, B.; Mi, W.; Emanuelli, M.; Wagner, D.; Thomson, D.; Gillingwater, T.; Court, F.; et al. Wallerian degeneration of injured axons and synapses is delayed by a Ube4b/Nmnat chimeric gene. Nat. Neurosci. 2001, 4, 1199–1206, [PubMed: 11770485]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rone, M.B.; Cui, Q.L.; Fang, J.; Wang, L.C.; Zhang, J.; Khan, D.; Bedard, M.; Almazan, G.; Ludwin, S.K.; et al. Oligodendrogliopathy in Multiple Sclerosis: Low Glycolytic Metabolic Rate Promotes Oligodendrocyte Survival. J. Neurosci. 2016, 36, 4698–4707, [PubMed: 27122029]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, J.D.; Brushart, T.M.; George, E.B.; Griffin, J.W. Prolonged survival of transected nerve fibres in C57BL/Ola mice is an intrinsic characteristic of the axon. J. Neurocytol. 1993, 22, 311–321, [PubMed: 8315413]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, I.R.; Gilliatt, R.W. Regeneration distal to a prolonged conduction block. J. Neurol. Sci. 1977 33, 267-273. [PubMed: 409804].

- Wee, A.S. Effects of acute and chronic denervation on human myotonia. Electromyogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2004, 44, 443–446, [PubMed: 15559079]. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lunn, E.R.; Brown, M.C.; Perry, V.H. The pattern of axonal degeneration in the peripheral nervous system varies with different types of lesion. Neuroscience 1990, 35, 157–165, [PubMed: 2359492]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beirowski, B.; Adalbert, R.; Wagner, D.; Grumme, D.S.; Addicks, K.; Ribchester, R.R.; Coleman, M.P. The progressive nature of Wallerian degeneration in wild-type and slow Wallerian degeneration (WldS) nerves. BMC Neurosci. 2005, Feb 1;6:6. [PubMed: 15686598].

| Parameter | Lipid Peroxidation (Arbitrary units ∙ 102 ∙ mg-1 of protein) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organ | Brain Cortex | Brachial Nerve | Liver | Muscle |

| Control values | 5.8 ± 1.6 | 2.7 ± 0.7 | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 1.4 ± 0.5 |

| Time after Surgery | ||||

| Day 1 | 6.1 ± 1.8 | 2.3 ± 0.7 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 3.0 ± 0.7* |

| Day 3 | 6.2 ± 2.0 | 1.7 ± 0.4* | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 4.1 ± 0.4* |

| Day 5 | 6.1 ± 4.0 | 1.3 ± 0.4* | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.4 |

| Day 7 | 6.0 ± 4.0 | 2.0 ± 0.7 | 3.3 ± 1.3* | 1.6 ± 0.4 |

| Day 10 | 5.9 ± 4.0 | 2.7 ± 1.1 | 2.0 ± 0.7 | 1.7 ± 0.5 |

| Day 15 | 6.0 ± 1.8 | 1.8 ± 0.7 | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 2.4 ± 0.7* |

| Day 20 | 5.7 ± 1.8 | 1.6 ± 0.7 | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 3.0 ± 0.7* |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).