1. Introduction

Camel farming is predominantly developed in the steppe and semi-desert regions of eastern Central Asia, Mongolia, and neighboring territories of Russia and China [

1,

2,

3]. This is due to the fact that the camel, as a livestock, successfully combines high meat and dairy productivity, as well as working capacity [

2,

4,

5]. Camels have adapted to living in a sharply continental, dry climate with hot and dry summers and very cold and snowy winters [

6,

7,

8]. In their natural habitat, they often face a lack of food and water. During the evolutionary development, these circumstances led to the emergence of various types of adaptive mechanisms in the organisms of these animals [

9,

10,

11]. One of them is fat accumulation. Fat is a reserve supply of nutrients, energy, and water. Its accumulation in certain parts of the organism prevents excessive excretion of water. The liver is directly involved in fat metabolism since it synthesizes cholesterol and other forms of lipoproteins [

12,

13,

14]. Features of fat metabolism, manifested in increased secretion and accumulation of lipids, inevitably have a direct impact on its structure [

7,

15,

16,

17]. Considering the latter, the goal of this research is to establish the features of the microstructural organization of the liver of the Bactrian camel (

Camelus bactrianus).

2. Materials and Methods

The studies were conducted using liver tissue fragments obtained during the planned slaughter of five 2.5-year-old Kazakh camels raised on a private farm in the Astrakhan Region. Further processing of selected tissue samples for the purpose of producing ultrathin sections was carried out following generally accepted methods [

18,

19]. The sections were contrasted with a 2.0% aqueous solution of uranyl acetate and a lead citrate solution and examined using a Jem-1011 electron microscope (JEOL, Japan) at magnifications of 2500–8000. When designating cellular and non-cellular structures, the terminology corresponding to the International Histological Nomenclature was used [

20].

Complied with the basic requirements set out in the “Rules of Laboratory Practice” in accordance with the Order of the Ministry of Health and Social Development of the Russian Federation dated August 23, 2010 No. 708n “on approval of the Rules of Laboratory Practice”. Ethical principles for the treatment of animals were observed in accordance with the “European Convention for the Protection of Vertebral Animals Used for Experimental and Other Scientific Purposes. cets no. 123.” All manipulations with the animals were carried out in accordance with the ethical principles approved by the Ethics Committees at the Russian Eye and Plastic Surgery Centre of the Bashkir State Medical University, Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Education “Ural State Agrarian University” and Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Education “Saint-Petersburg State University of Veterinary Medicine”.

3. Results

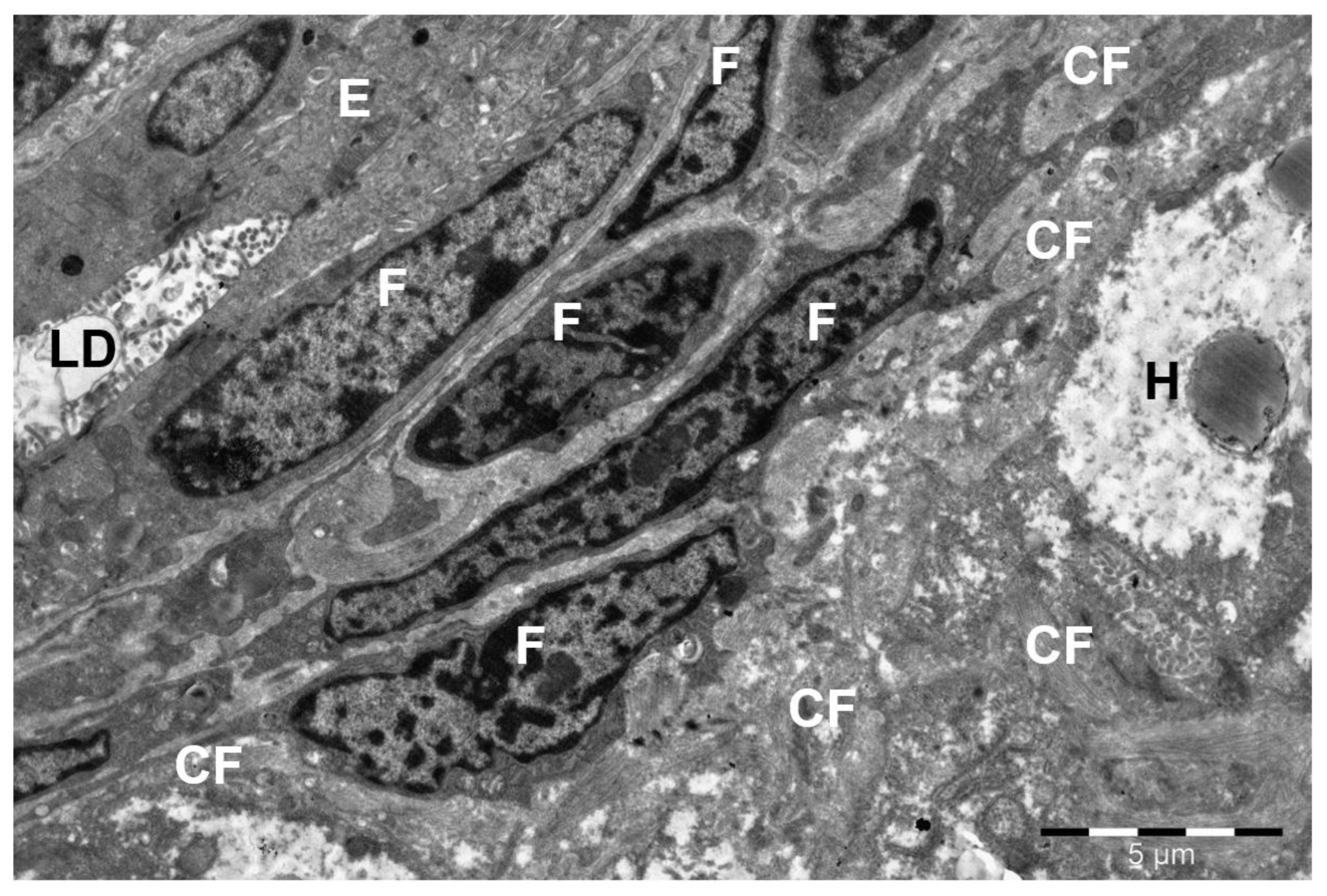

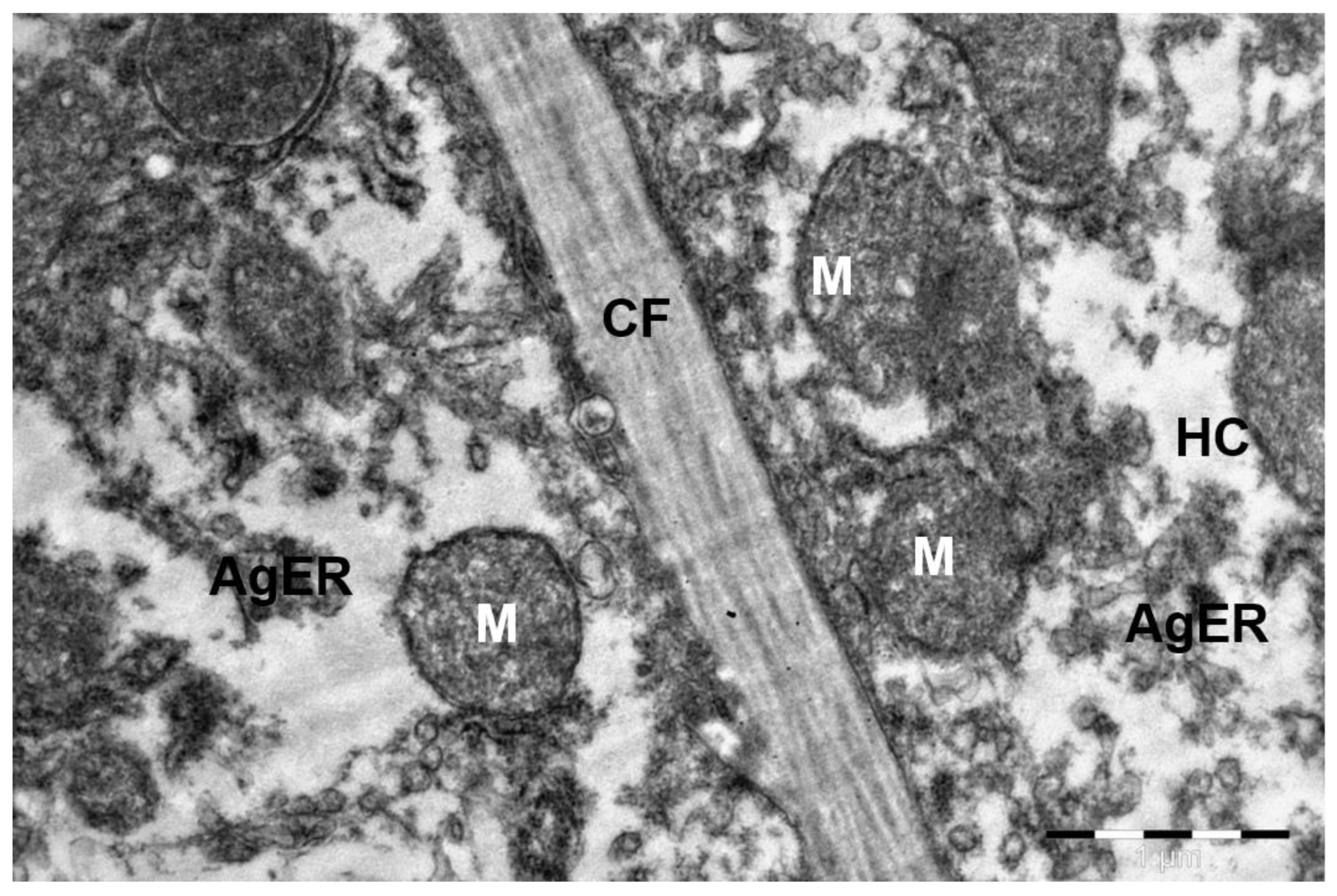

It was established that in the camel, the portal tracts lay predominantly in the area of the lateral edges of the lobules adjacent to each other and were formed by the interlobular arteries and veins, as well as the interlobular excretory bile duct. During histological examination, it was noted that the liver lobules of the studied animals have a prismatic shape and are clearly delimited from each other by a layer of connective tissue, which was confirmed by electron microscopic studies. The connective tissue reached its greatest development in the area of the portal tracts and its least development in the area of contact of the lobules with each other by their lateral surfaces (

Figure 1,

Figure 2).

The connective tissue separating the lobules gave rise to connective tissue strands, which thinned as they moved toward the center. In turn, the central vein lay surrounded by ring-shaped bundles of connective tissue, penetrated by sinusoidal capillaries flowing into it (

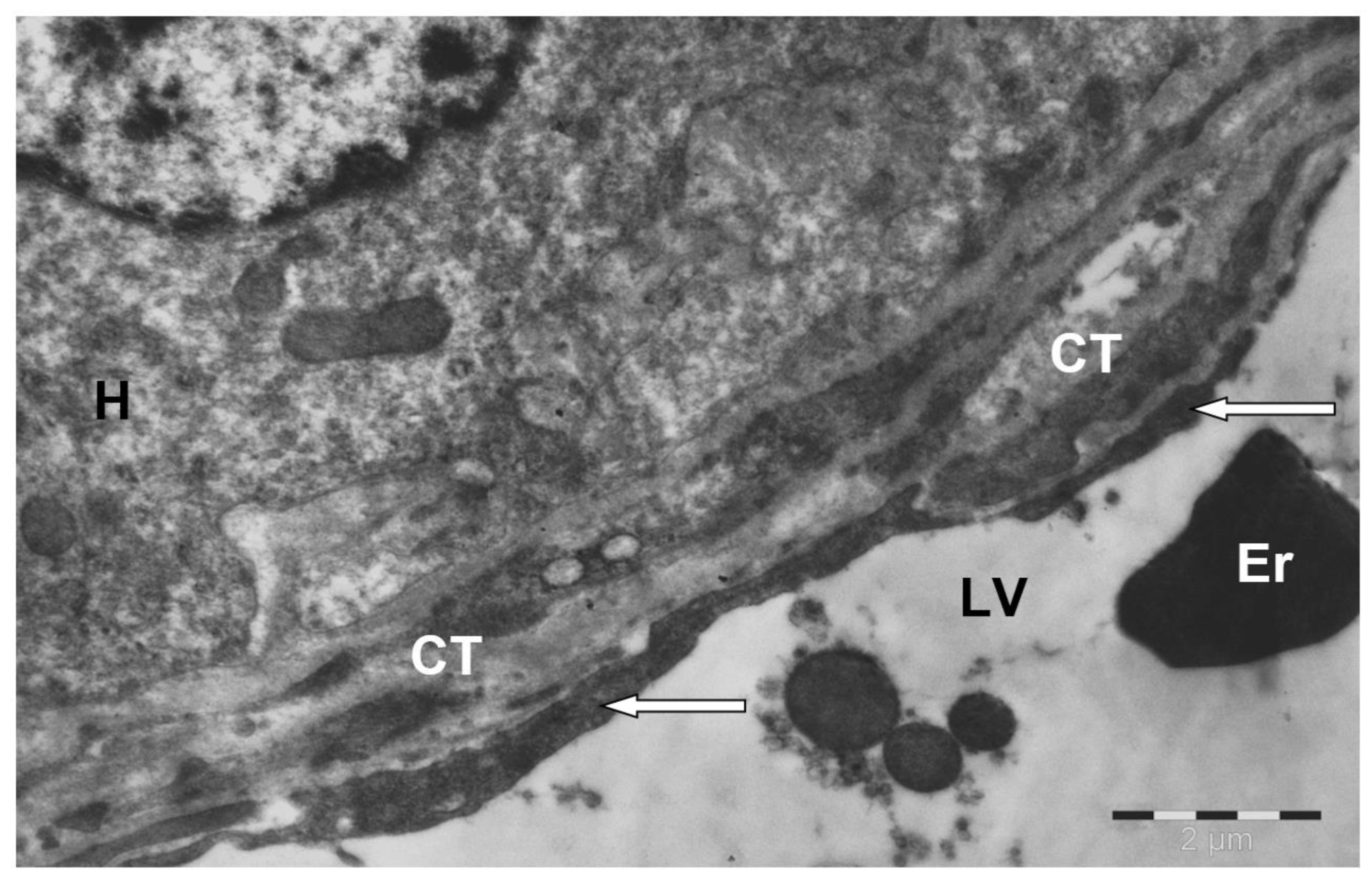

Figure 3).

The bulk of the camel liver parenchyma was formed by hepatocytes, which were epithelial cells of a round or polygonal shape. Electron microscopy showed that their cytoplasmic membrane was represented by two layers—outer and inner. They were separated by a light osmiophobic space, the width of which varied between 2.0 and 3.0 nm. Lining up in rows, hepatocytes formed hepatic beams, in the center of which there was a space for the accumulation and excretion of the bile they produced—the bile capillary. Thus, one pole of the cells—biliary—was directed into the lumen of the bile capillary formed by them, and the other, vascular, adjoined the wall of the sinusoidal capillary. The specified topographic location causes differences in the ultrastructural organization of these cell parts, determined by the function performed.

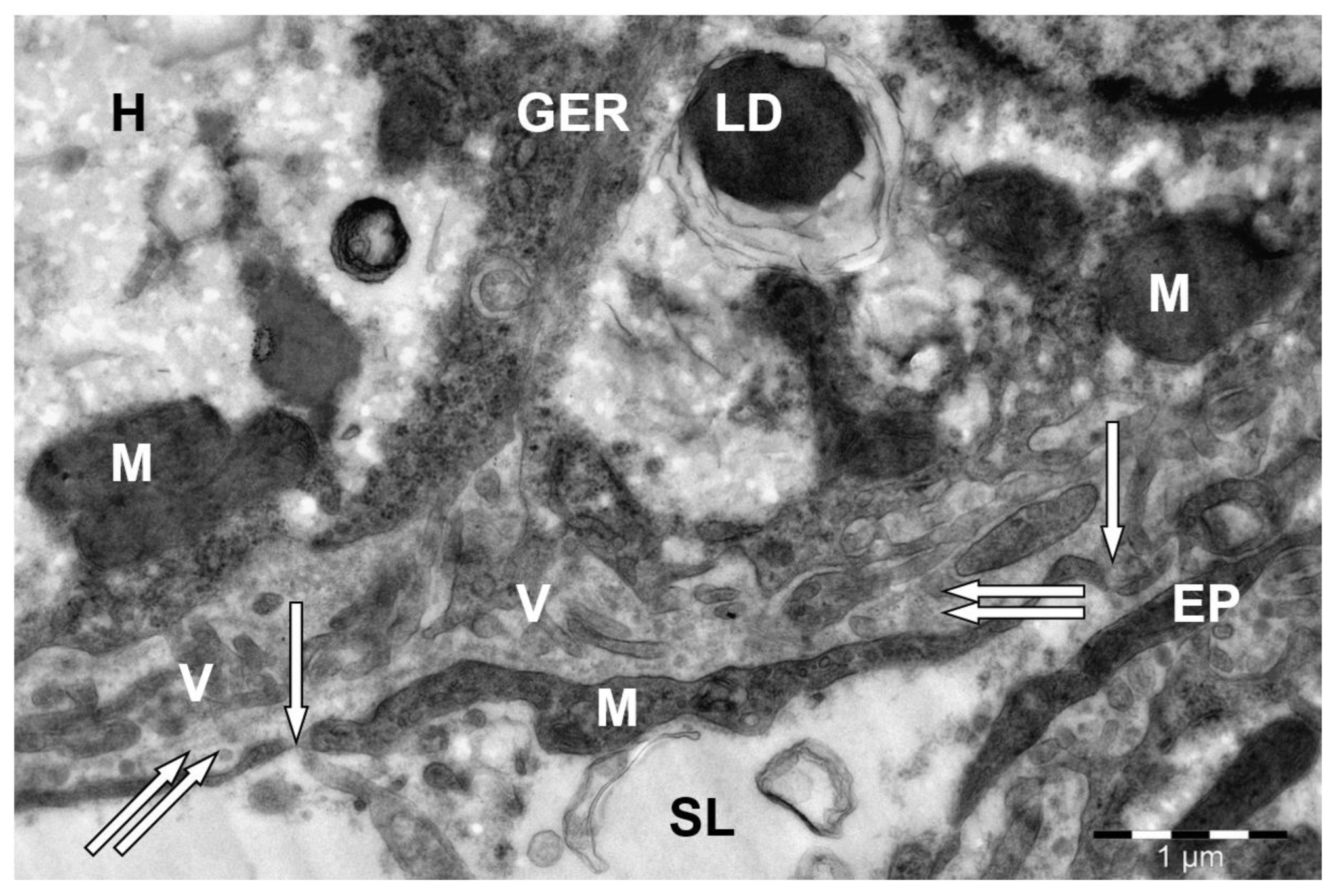

The vascular (sinusoid) side of the hepatocytes facing the lumen of the hemocapillary formed numerous microvilli of varying length (

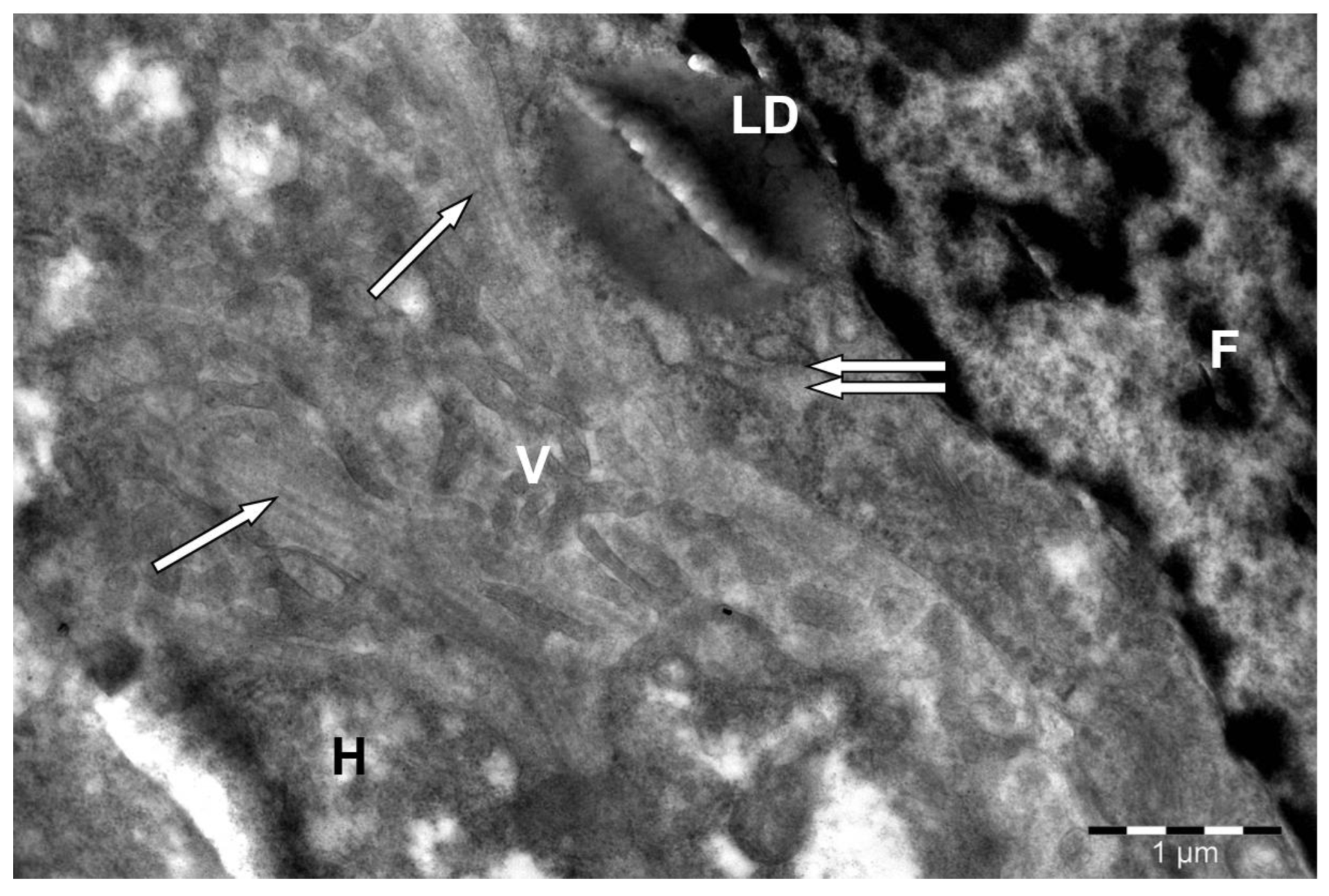

Figure 4). This side of the hepatocytes and the endothelial cells lining the entire surface of the sinusoid capillaries and their long processes formed a space called the Disse space.

Short microvilli were located mainly in the presinusoidal space, while long ones penetrated it and, passing through the pores of the sinusoid endothelial cells lying on the discontinuous basement membrane, penetrated into its lumen, directly contacting the blood. In many areas of the Disse space, a three-dimensional network of thin collagen fibers was detected together with fibroblasts (

Figure 5). In some areas, not only the processes of the sinusoid endothelial cells but also their elongated large bodies containing a large flattened nucleus were visible in the field of view. The cytoplasm of endothelial cells contained ribosomes and polyribosomes, single short cisterns of the granular endoplasmic reticulum, small oval mitochondria, and a large number of vesicles and bubbles.

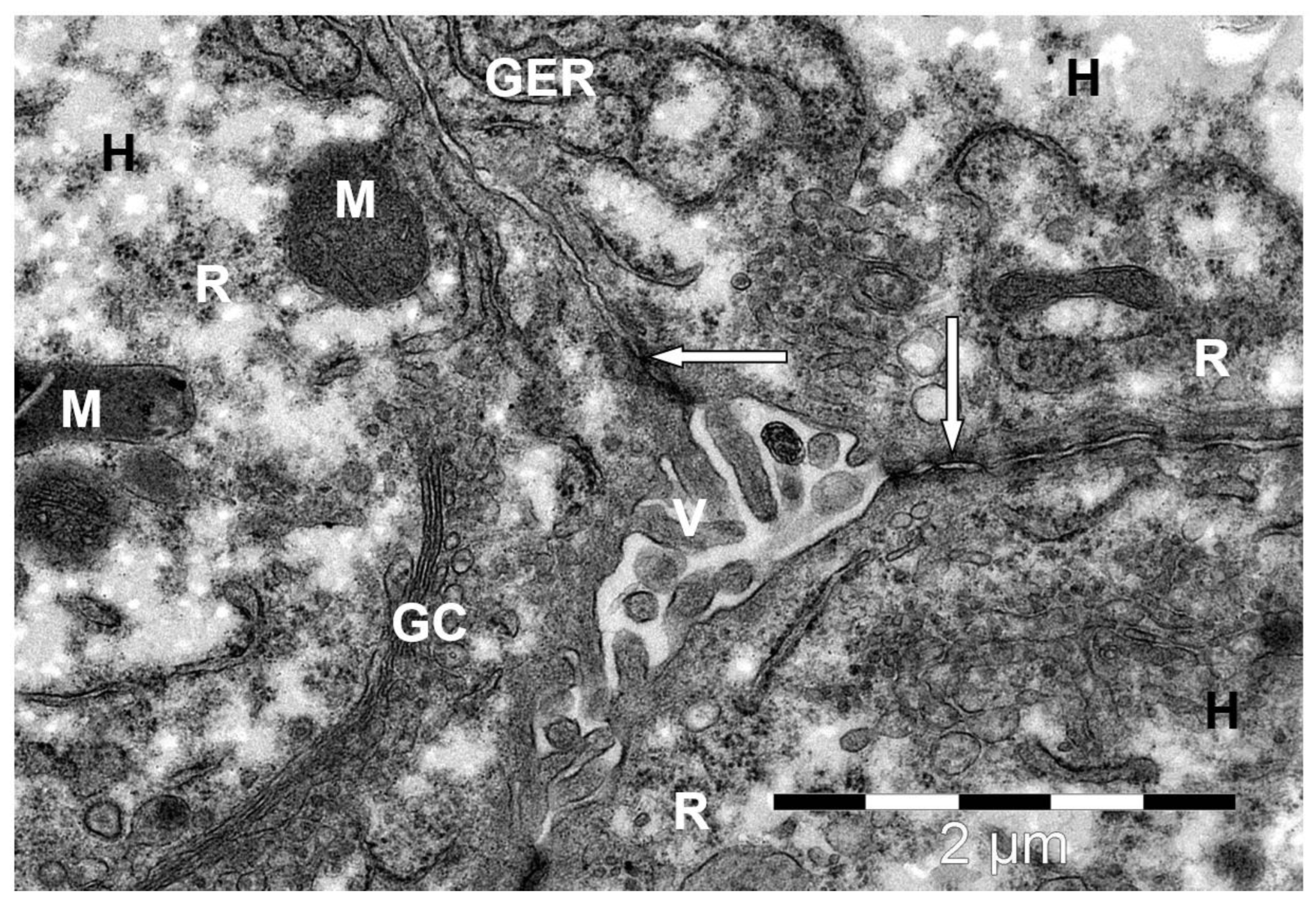

The opposite (biliary) surface of the hepatocytes, facing the bile capillary, formed many microvilli facing its lumen (

Figure 6). Very often, in the cytoplasm of hepatocytes near the bile canaliculi, in addition to long cisterns of granular endoplasmic reticulum, free ribosomes, and polyribosomes, the Golgi complex was clearly visible in the form of flattened cisterns arranged in parallel stacks with numerous vesicles surrounding them. This probably indicates the participation of the described organelle in the synthesis of bile components.

It should be noted that the lateral parts of the liver cells near the bile capillary were in contact with each other via dense osmiophilic desmosomes, which provided increased strength of the intercellular connection.

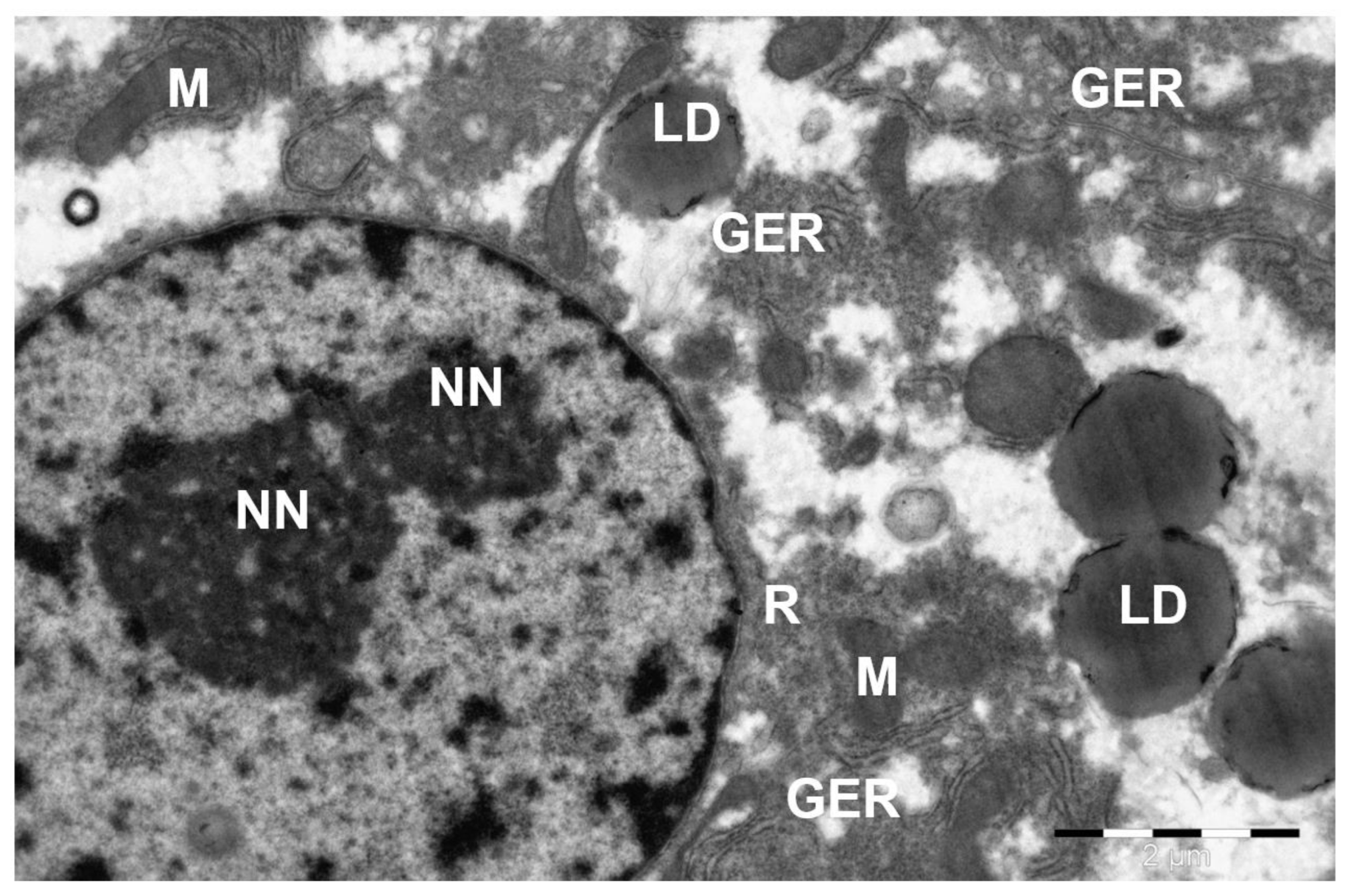

The nuclei of the hepatocytes were sometimes located in the center, sometimes eccentrically. Their position also depended on the amount of inclusions accumulated in the cytoplasm, especially of a lipid nature. Two layers separated by a light strip of perinuclear space represented the nuclear membrane. The nuclear matrix was electron-light in its composition. Inclusions of finely dispersed euchromatin were distinguishable. At the same time, heterochromatin in the form of small conglomerates was concentrated along the inner nuclear membrane. The sizes of the hepatocyte nuclei varied, with one or two electron-dense nucleoli being detected in almost every one of them (

Figure 7).

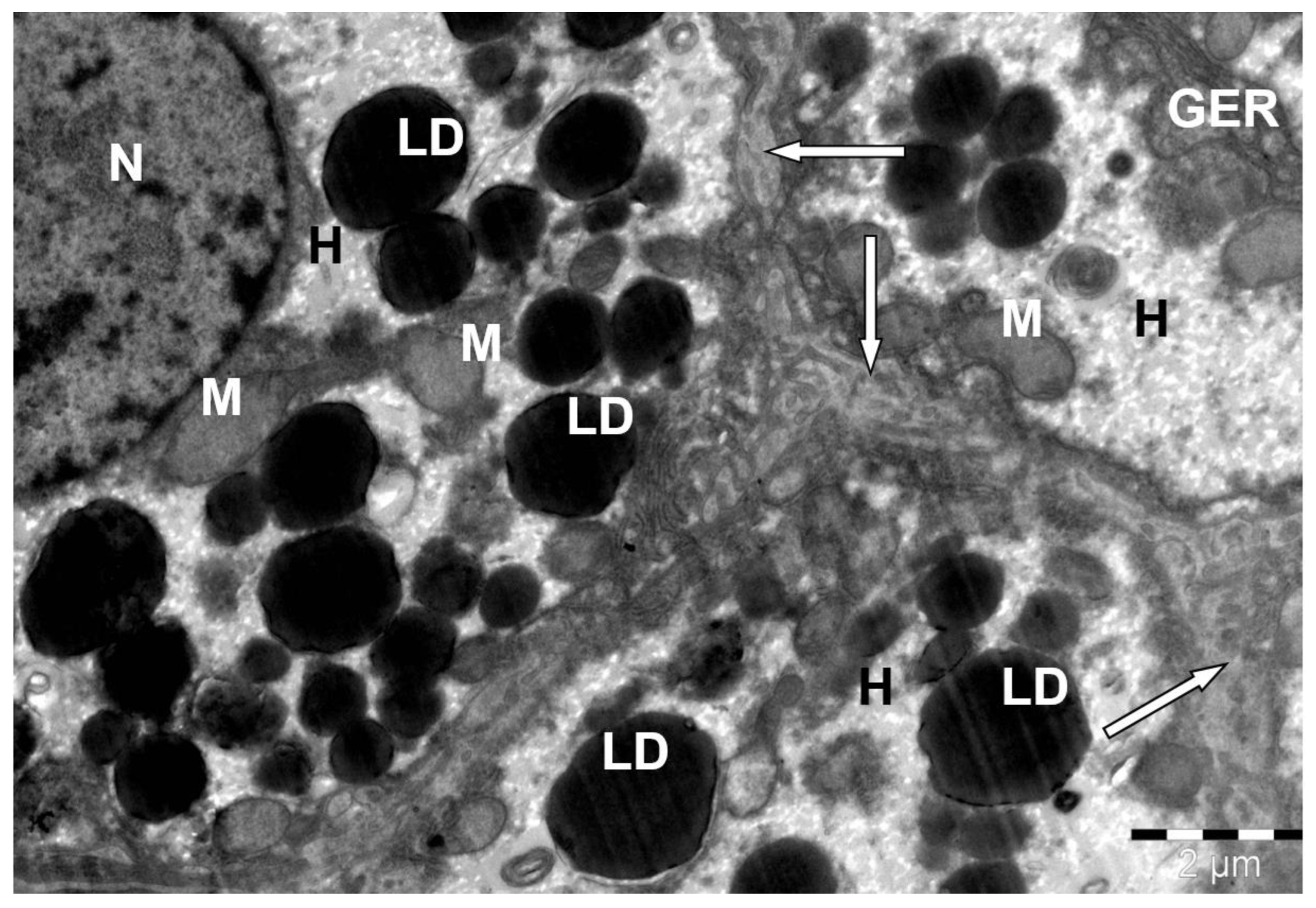

In addition to round and oval mitochondria with thin cristae and dark mitochondrial matrix, elongated thin cisterns of granular and short bubble-shaped tubules of smooth endoplasmic reticulum and accumulations of glycogen and lipid droplets were detected in the cytoplasm of hepatocytes. Very small glycogen granules in the cytosol of hepatocytes were both scattered and grouped, but most often surrounding fat droplets. In the case of accumulation of lipids in the cytoplasm of hepatocytes, as a rule, many large lipid droplets were detected.

Sometimes hepatocytes with small and medium-sized fat droplets were found, and these inclusions were located predominantly in the cytoplasm of the sinusoid pole of hepatocytes (

Figure 8). It should also be noted that their accumulation occurred most intensively in the hepatocytes of the peripheral and middle zones of the liver lobules, rather than in their center.

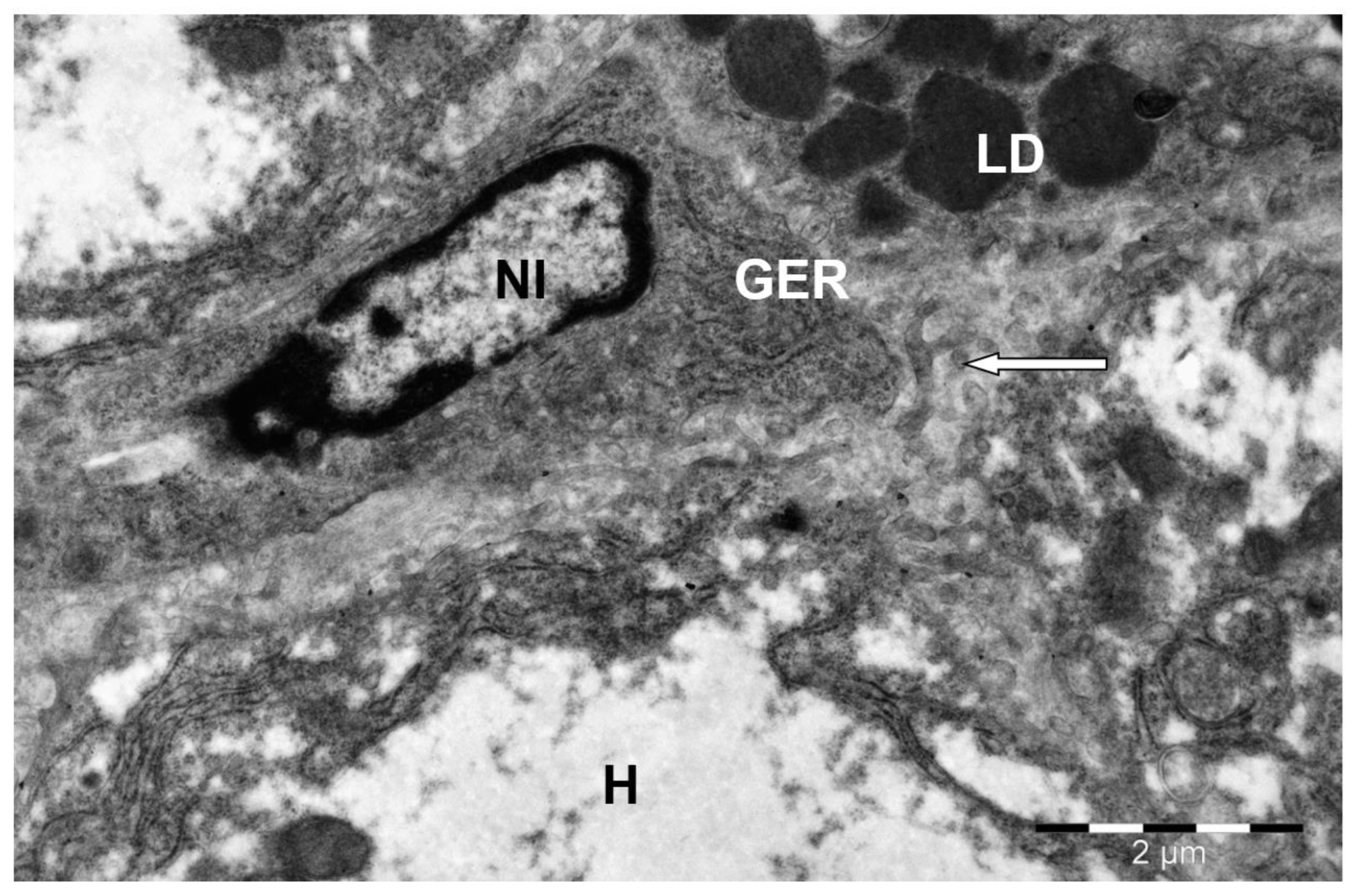

In the liver of the animals studied, perisinusoidal fat-accumulating Ito cells, which are characterized by collagen synthesis, were very often found (

Figure 9). These are elongated stellate cells, localized most often within the Disse space, but they were also often detected in the connective tissue stroma of the liver lobules, especially near the portal tracts. With a strong accumulation of lipids, their large drops displaced the nucleus to the periphery of the cell, thereby changing its shape. In addition to lipid droplets, many cisterns of the granular endoplasmic reticulum were characteristically detected in the cytoplasm of these cells.

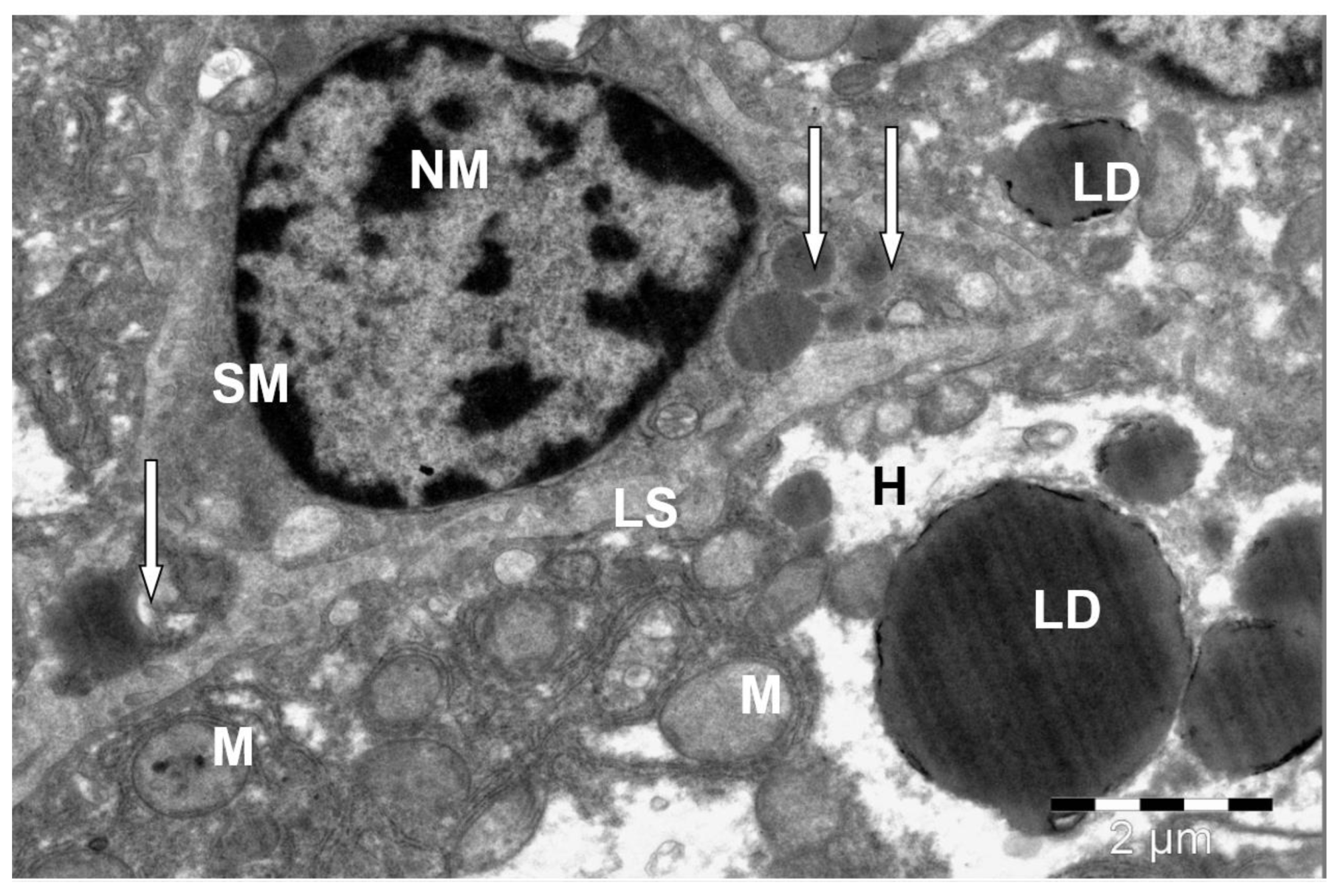

Large dendritic cells with high phagocytic activity, stellate macrophages (Kupffer cells) (

Figure 10), were found in the lumens of sinusoidal capillaries. They had one large nucleus of an elongated oval or irregular shape, sometimes with strongly jagged edges. A large amount of heterochromatin was determined in the nuclei, which lay on the internal karyolemma or were diffusely located in large clumps throughout the nuclear matrix.

These cells were anchored with their basal ends in the bifurcations between hepatocytes, while their bodies and processes lay freely in the lumen of the sinusoidal capillary.

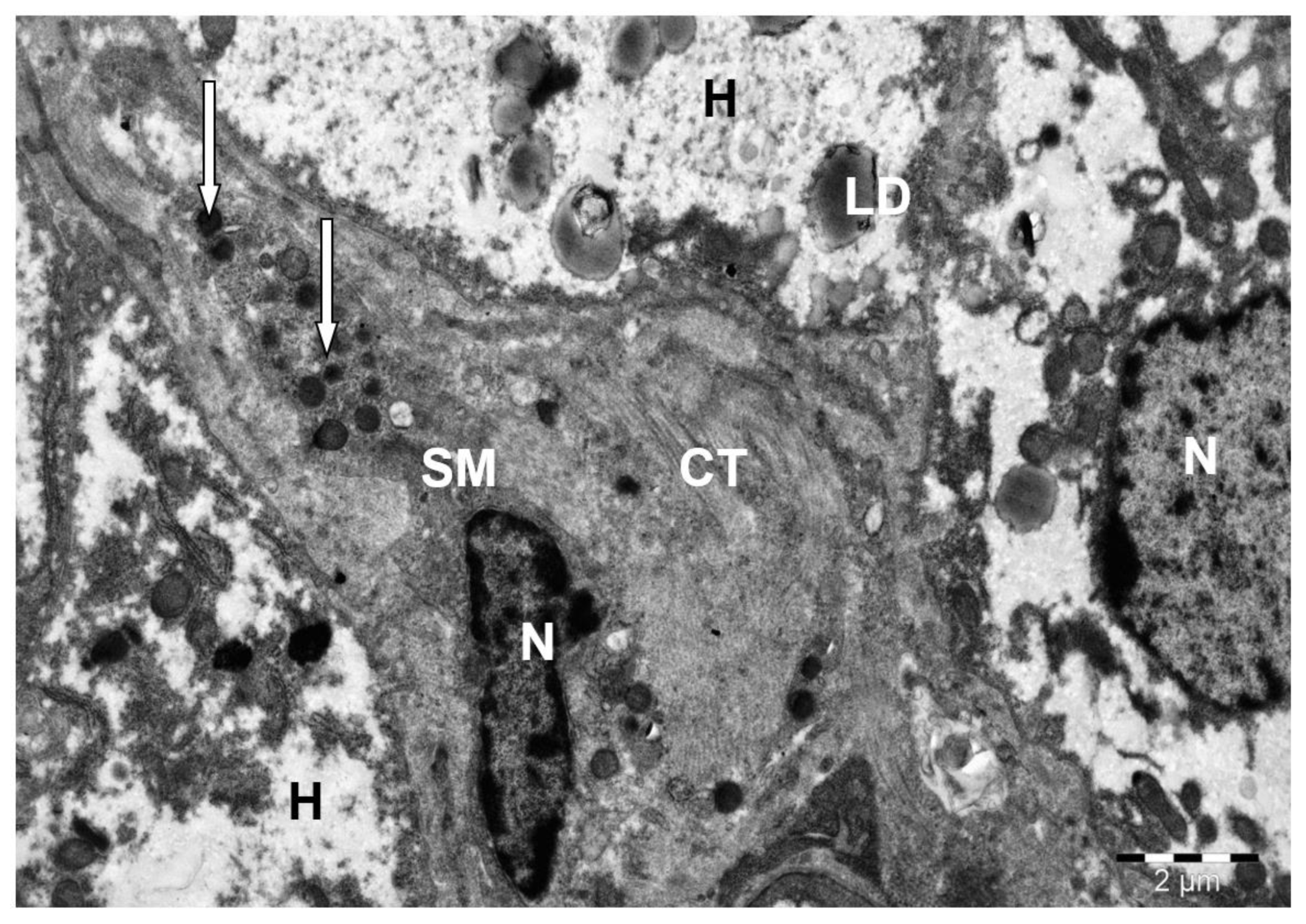

This type of cell was characterized by optically dark cytoplasm, which was due to the high content of ribosomes, polyribosomes, small granules and vesicles, lysosomes, and heterogeneous phagolysosomes. Their cytoplasm could also contain many rounded small mitochondria, a well-developed Golgi complex, and short cisterns of the granular endoplasmic reticulum. Sometimes parts of obsolete erythrocytes and hemosiderin inclusions were found in the cytoplasm. Also, in many areas of the liver parenchyma, along with the presence of stellate macrophages, many sinusoidal capillaries were filled with strands of connective tissue (

Figure 11).

4. Discussion

Unlike other mammals, the camel’s liver exhibits a number of characteristics that can be linked to its lifestyle and metabolic requirements [

2,

5,

8].

Firstly, the significant number of hepatocytes and their special morphological characteristics indicate a high capacity for metabolism and detoxification [

21,

22]. The narrow sinusoids and widened spatial thresholds observed in the liver may facilitate efficient interactions between hepatocytes and Kupffer cells, which is critical for immune defense and metabolism in settings where parasitic and microbial infections are highly likely.

Secondly, the observed increase in the amount of fat deposits in hepatocytes may be a sign of adaptation to periods of food shortage. It may also indicate a role for the liver in regulating energy metabolism and accumulating nutrient reserves necessary for survival in arid conditions [

23,

24,

25].

The observed differences in the structure of the cellular tissue may also reflect the interaction of the liver with other organs and systems. For example, the presence of a branched vascular system may indicate the need for more intense perfusion associated with increased metabolic demands during physiological activity in camels [

1,

2,

3,

10]. Thus, increasing vascular supply may be a key aspect in adapting to their environmental conditions.

Our studies highlight the great diversity of dromedary liver structure and raise important questions about the influence of various environmental factors on its morphology. These results can form the basis for further research in the field of comparative anatomy and physiology, as well as for assessing the health and productivity of camels in pasture and farm animal husbandry conditions.

It is also worth noting that the specificity of the liver microstructure may be useful for veterinary practice, in particular for the development of preventive measures against liver diseases in camels. Understanding the liver’s unique adaptations may help develop less invasive diagnostic and therapeutic methods, which in turn may improve the care of these animals [

26,

27,

28].

This study sheds light on important aspects of the microstructural organization of the dromedary liver and highlights the need for further study of this topic to better understand the adaptive mechanisms that allow this species to thrive in extreme conditions.

5. Conclusions

The structural organization of the liver of the Bactrian camel does not differ fundamentally from that of other mammals, although it does have some peculiarities. The liver of camels is characterized by a strong development of fibrous connective tissue not only in the portal tracts, but also between hepatocytes, in the lumen of sinusoidal capillaries, and even in small quantities in the persinusoidal spaces of Disse. A large number of fat-accumulating Ito cells are noted, participating in the synthesis and accumulation of collagen fibers. Along with the pronounced fatty infiltration of most hepatocytes, they may also indicate an important role of the liver in lipogenesis in this animal species.

During the study of the microstructural organization of the liver of the one-humped camel, many unique features were revealed, reflecting the adaptation mechanisms of this species to extreme living conditions. Characterization of the histological structure of the liver demonstrates a high degree of development of various cellular elements, such as hepatocytes, Kupffer cells and cellular elements of mesenchymal origin, which indicates a complex functional organization of the organ.

Structural changes such as increased sinusoid size and vascular network features indicate high metabolic activity and the ability to accumulate nutrients necessary for survival in conditions of low moisture and food supply. The data obtained are important for understanding the physiology of the dromedary camel liver and can also serve as a basis for further research in veterinary medicine and zoology.

The analysis of the liver microstructure also opens up new horizons for studying diseases of this animal, which can contribute to the development of more effective diagnostic and therapeutic methods. The study of the microstructural organization of the dromedary camel liver emphasizes the importance of the adaptation of this species to its habitat and opens up new perspectives for studying the functional biology and ecology of camels in general.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: title; Table S1: title; Video S1: title.

Author Contributions

Musina L.A. – The concept and design of the study, Collecting and interpreting the data.

Lebedeva A.I.- Sample preparation, Literature overview.

Drozdova L.I. - Drafting the manuscript, Revising the manuscript.

Prusakov A.V. - The concept and design of the study, Collecting and interpreting the data.

Ponamarev V.S. - Revising the manuscript, Translating the manuscript, Editing the manuscript.

Funding

The study supported by the grant of the Russian Science Foundation No. 24-76-10011, https://rscf.ru/project/24-76-10011/

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committees at the Russian Eye and Plastic Surgery Centre of the Bashkir State Medical University, Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Education “Ural State Agrarian University” and Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Education “Saint-Petersburg State University of Veterinary Medicine”.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Available in section

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their sincere thanks to the members of the Russian Eye and Plastic Surgery Centre of the Bashkir State Medical University, Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Education “Ural State Agrarian University” and Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Education “Saint-Petersburg State University of Veterinary Medicine” for their help and support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ali MA, Abu Damir H, Adem MA, et al. Effects of long-term dehydration on stress markers, blood parameters, and tissue morphology in the dromedary camel (Camelus dromedarius). Front Vet Sci. 2023; 10: 1236425. [CrossRef]

- Riley J, Garner MM, Kiupel M, et al. Disseminated toxoplasmosis in a captive adult dromedary camel (Camelus dromedarius). J Zoo Wildl Med. 2017;48(3):937-940. [CrossRef]

- Zeyadi M. Effect of organic additives on storage stability of camel liver catalase against environmental conditions. Main Group Chem. 2022;21(1):225-231. [CrossRef]

- Tharwat M, Alkheraif AA, Oikawa S. Production diseases in farm animals: A comprehensive and illustrated clinical, laboratory, and pathological overview. Open Vet J. 2025;15(1):18-34. [CrossRef]

- Yashin A, Kasatkina E, Prusakov A, et al. The T-RFLP research method in the study of rumen microbiota in dairy cows with subclinical ketosis. In: Bio Web Conf: Int Sci Pract Conf “Agrarian Science – 2023” (AgriScience2023); April 25–26, 2023; Moscow, Russia. EDP Sciences; 2023:06001. [CrossRef]

- Terab AMA, Abdel Wahab GED, Ishag HZA, et al. Pathology, bacteriology and molecular studies on caseous lymphadenitis in Camelus dromedarius in the Emirate of Abu Dhabi, UAE, 2015–2020. PLoS One. 2021;16(6):e0252893. [CrossRef]

- Tharwat M. Ultrasonography of the liver in healthy and diseased camels (Camelus dromedarius). J Vet Med Sci. 2020;82(4):399-407. [CrossRef]

- Tharwat M, Ali H, Alkheraif AA. Clinical insights on paratuberculosis in Arabian camels (Camelus dromedarius): A review. Open Vet J. 2025;15(1):8-17. [CrossRef]

- Al-Bar OAM, El-Shishtawy RM, Mohamed SA. Immobilization of camel liver catalase on nanosilver-coated cotton fabric. Catalysts. 2021;11(8). [CrossRef]

- El Saftawy EA, Abdelmoktader A, Sabry MM, et al. Histological and immunological insights to hydatid disease in camels. Vet Parasitol Reg Stud Rep. 2021;26:100635. [CrossRef]

- Panwar A, Thanvi PK, Dangi A, et al. Histochemical studies of the liver of dromedary camel (Camelus dromedarius). Int J Adv Biochem Res. 2025;9(3S):5-9. [CrossRef]

- Alekhin YN, Popova OS, Ponomarev VS, et al. Effect of farnesoid X receptor agonist on postprandial lipemia in rats fed a diet containing a supraphysiological dose of fat. Dev Regist Drugs. 2023;12(2):174-184. [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsov YuE, Lunegov AM, Ponomarev VS, et al. Correlation relationships between the content of total bile acids and the main biochemical parameters of blood in minks (Mustela vison Schreber, 1777). Agric Biol. 2022;57(6):1217-1224. [CrossRef]

- Prusakova A, Zelenevskiy N, Prusakov A, et al. Organization of histo-hematic barriers of the liver in Anglo-Nubian goat. Online J Anim Feed Res. 2023;13(4):242-245. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim A, El-Ghareeb WR, Aljazzar A, et al. Hepatic lobe torsion in 3 dromedary camels. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2021;33(1):136-139. [CrossRef]

- Ponamarev V, Popova O, Kostrova A, et al. A new method for assessing the toxic properties of various medicinal substances on the hepatobiliary system functionality in the context of the ecopharmacology development. In: II Int Conf Sustainable Development: Agriculture, Veterinary Medicine and Ecology (VMAEE-II-2023); April 21–22, 2023; Karshi, Russia. AIP Publishing; 2023:20027. [CrossRef]

- Prusakova AV, Zelenevskiy NV, Prusakov AV, et al. Ultrastructural organization of liver hepatocytes of the Anglo-Nubian goat. Vet Glasn. 2023;77(2):176-187. [CrossRef]

- Anwar Ul-H. A Beginners’ Guide to Scanning Electron Microscopy. 1st ed. Springer Nature; 2018.

- Ramezanpour H, Yousefi H, Rezaei M, et al. Effects of rotational motion in robotic needle insertion. J Biomed Phys Eng. 2015;5(4):207-216.

- Semchenko VV. International Histological Nomenclature. Kolosova; 1999.

- Ahmed A, Malik A, Jagirdar H, et al. Copper-induced inactivation of camel liver glutathione S-transferase. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2016;169(1):69-76. [CrossRef]

- Asli M, Azizzadeh M, Moghaddamjafari A, et al. Copper, iron, manganese, zinc, cobalt, arsenic, cadmium, chrome, and lead concentrations in liver and muscle in Iranian camel (Camelus dromedarius). Biol Trace Elem Res. 2020;194(2):390-400. [CrossRef]

- Chafik A, Essamadi A, Çelik SY, et al. Partial purification and some interesting properties of glutathione peroxidase from liver of camel (Camelus dromedarius). Russ J Bioorg Chem. 2018;44(1):41-51. [CrossRef]

- Maharem TM, Emam MA, Said YA. Purification and characterization of L-glutaminase enzyme from camel liver: enzymatic anticancer property. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;150:1213-1222. [CrossRef]

- Maharem TM, Zahran WE, Hassan RE, et al. Unique properties of arginase purified from camel liver cytosol. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;108:88-97. [CrossRef]

- Ponamarev V, Popova O, Kostrova A, et al. The concept of development of new ecologically based methods of diagnostics and pharmacocorrection in veterinary medicine (on the example of pathologies of the hepatobiliary system). In: II Int Conf Sustainable Development: Agriculture, Veterinary Medicine and Ecology (VMAEE-II-2023); April 21–22, 2023; Karshi, Russia. AIP Publishing; 2023:20028. [CrossRef]

- Ponamarev V, Yashin A, Prusakov A, et al. Influence of modern probiotics on morphological indicators of pigs’ blood in toxic dyspepsia. In: Agriculture Digitalization and Organic Production: Proc Second Int Conf; June 6–8, 2022; St. Petersburg, Russia. Springer; 2022:133-142. [CrossRef]

- Prusakova AV, Zelenevskiy NV, Prusakov AV, et al. Ultra-structural organization of the gallbladder mucous membrane of Anglo-Nubian goat. Vet Res Forum. 2024;15(3):165-169. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Fragment of the portal tract of the camel liver. LD - lumen of the bile duct; E - bile duct epithelial cells; F - fibroblast cells; CF - collagen fibers; H - fragment of a hepatocyte with a lipid droplet in the cytoplasm. Electron microphotography.

Figure 1.

Fragment of the portal tract of the camel liver. LD - lumen of the bile duct; E - bile duct epithelial cells; F - fibroblast cells; CF - collagen fibers; H - fragment of a hepatocyte with a lipid droplet in the cytoplasm. Electron microphotography.

Figure 2.

Collagen fibers between the lateral surfaces of the hepatic lobules in a camel liver. HC - hepatocyte cytoplasm; M - mitochondria; AgER - agranular endoplasmic reticulum channels; CF - collagen fibers between the liver lobules. Electron microphotography.

Figure 2.

Collagen fibers between the lateral surfaces of the hepatic lobules in a camel liver. HC - hepatocyte cytoplasm; M - mitochondria; AgER - agranular endoplasmic reticulum channels; CF - collagen fibers between the liver lobules. Electron microphotography.

Figure 3.

Annularly arranged bundles of connective tissue (CT) around the central vein in the camel liver. LV - lumen of the central vein; H - hepatocyte; endothelial cells (↑) of the vein wall; Er - erythrocyte in the lumen of the vein. Electron microphotography.

Figure 3.

Annularly arranged bundles of connective tissue (CT) around the central vein in the camel liver. LV - lumen of the central vein; H - hepatocyte; endothelial cells (↑) of the vein wall; Er - erythrocyte in the lumen of the vein. Electron microphotography.

Figure 4.

Vascular (sinusoid) side of a hepatocyte (H) in camel liver. V - hepatocyte villi; M - mitochondria; GER - granular endoplasmic reticulum channels; R - ribosomes; LD - lipid droplet; EP - endothelial cell processes; endothelial cell pores (↑); perisinusoidal space of Disse (↑↑); SL - sinusoid lumen. Electron microphotography.

Figure 4.

Vascular (sinusoid) side of a hepatocyte (H) in camel liver. V - hepatocyte villi; M - mitochondria; GER - granular endoplasmic reticulum channels; R - ribosomes; LD - lipid droplet; EP - endothelial cell processes; endothelial cell pores (↑); perisinusoidal space of Disse (↑↑); SL - sinusoid lumen. Electron microphotography.

Figure 5.

Sinusoidal side of a hepatocyte (H) in camel liver. F - fibroblast; dilated channels of the granular endoplasmic reticulum (↑↑); LD - lipid droplet; V - hepatocyte villi; collagen fibers (↑) in the perisinusoidal space of Disse. Electron microphotography.

Figure 5.

Sinusoidal side of a hepatocyte (H) in camel liver. F - fibroblast; dilated channels of the granular endoplasmic reticulum (↑↑); LD - lipid droplet; V - hepatocyte villi; collagen fibers (↑) in the perisinusoidal space of Disse. Electron microphotography.

Figure 6.

Bile canaliculi with villi (V) on the biliary side of a camel liver hepatocyte. H - hepatocyte; desmosomes (↑); GC - Golgi complex; M - mitochondria; GER - granular endoplasmic reticulum channels; R - ribosomes and polyribosomes. Electron microphotography.

Figure 6.

Bile canaliculi with villi (V) on the biliary side of a camel liver hepatocyte. H - hepatocyte; desmosomes (↑); GC - Golgi complex; M - mitochondria; GER - granular endoplasmic reticulum channels; R - ribosomes and polyribosomes. Electron microphotography.

Figure 7.

Structure of a camel liver hepatocyte. NN - nucleolus in the nucleus; LD - lipid droplet; M - mitochondria; GER - granular endoplasmic reticulum channels; R - ribosomes and polyribosomes. Electron microphotography.

Figure 7.

Structure of a camel liver hepatocyte. NN - nucleolus in the nucleus; LD - lipid droplet; M - mitochondria; GER - granular endoplasmic reticulum channels; R - ribosomes and polyribosomes. Electron microphotography.

Figure 8.

Structure of a camel liver hepatocyte. H - hepatocyte; N - nucleus; LD - lipid droplets; M - mitochondria; GER - granular endoplasmic reticulum channels; sinusoidal capillaries (↑). Electron microphotography.

Figure 8.

Structure of a camel liver hepatocyte. H - hepatocyte; N - nucleus; LD - lipid droplets; M - mitochondria; GER - granular endoplasmic reticulum channels; sinusoidal capillaries (↑). Electron microphotography.

Figure 9.

Fat-storing Ito cell in the camel liver. H - hepatocyte; NI - Ito cell nucleus; LD - lipid inclusions; GER - granular endoplasmic reticulum channels; hepatocyte villi in sinusoids (↑). Electron microphotography.

Figure 9.

Fat-storing Ito cell in the camel liver. H - hepatocyte; NI - Ito cell nucleus; LD - lipid inclusions; GER - granular endoplasmic reticulum channels; hepatocyte villi in sinusoids (↑). Electron microphotography.

Figure 10.

Stellate macrophage (Cooper cell) in the liver of a camel. H - hepatocyte; SM - stellate macrophage; NM- macrophage nucleus; LS - sinusoid lumen; LD - lipid inclusions; M - mitochondria; lysosomes and phagolysosomes (↑). Electron microphotography.

Figure 10.

Stellate macrophage (Cooper cell) in the liver of a camel. H - hepatocyte; SM - stellate macrophage; NM- macrophage nucleus; LS - sinusoid lumen; LD - lipid inclusions; M - mitochondria; lysosomes and phagolysosomes (↑). Electron microphotography.

Figure 11.

Connective tissue (CT) strands and a stellate macrophage (Cooper cell) (SM) in the lumen of a dilated sinusoidal capillary of camel liver. G - hepatocyte; N - nucleus; L - lipid inclusions; M - mitochondria; lysosomes and phagolysosomes (↑). Electron microphotography.

Figure 11.

Connective tissue (CT) strands and a stellate macrophage (Cooper cell) (SM) in the lumen of a dilated sinusoidal capillary of camel liver. G - hepatocyte; N - nucleus; L - lipid inclusions; M - mitochondria; lysosomes and phagolysosomes (↑). Electron microphotography.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).