Submitted:

04 August 2025

Posted:

12 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

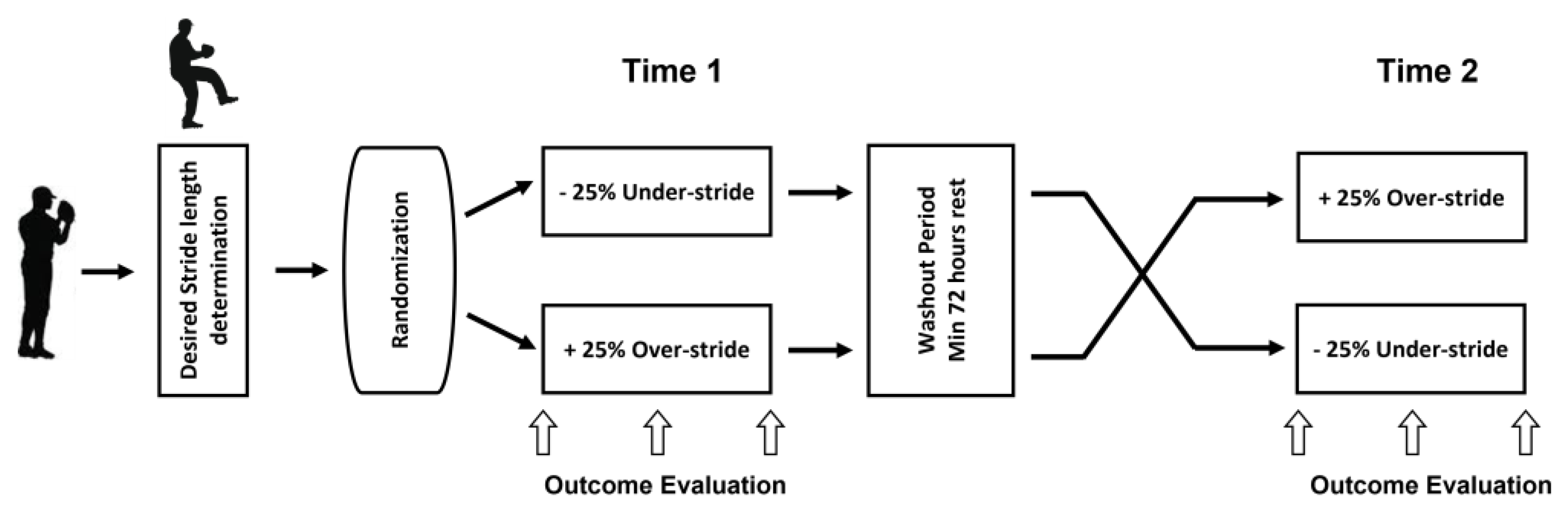

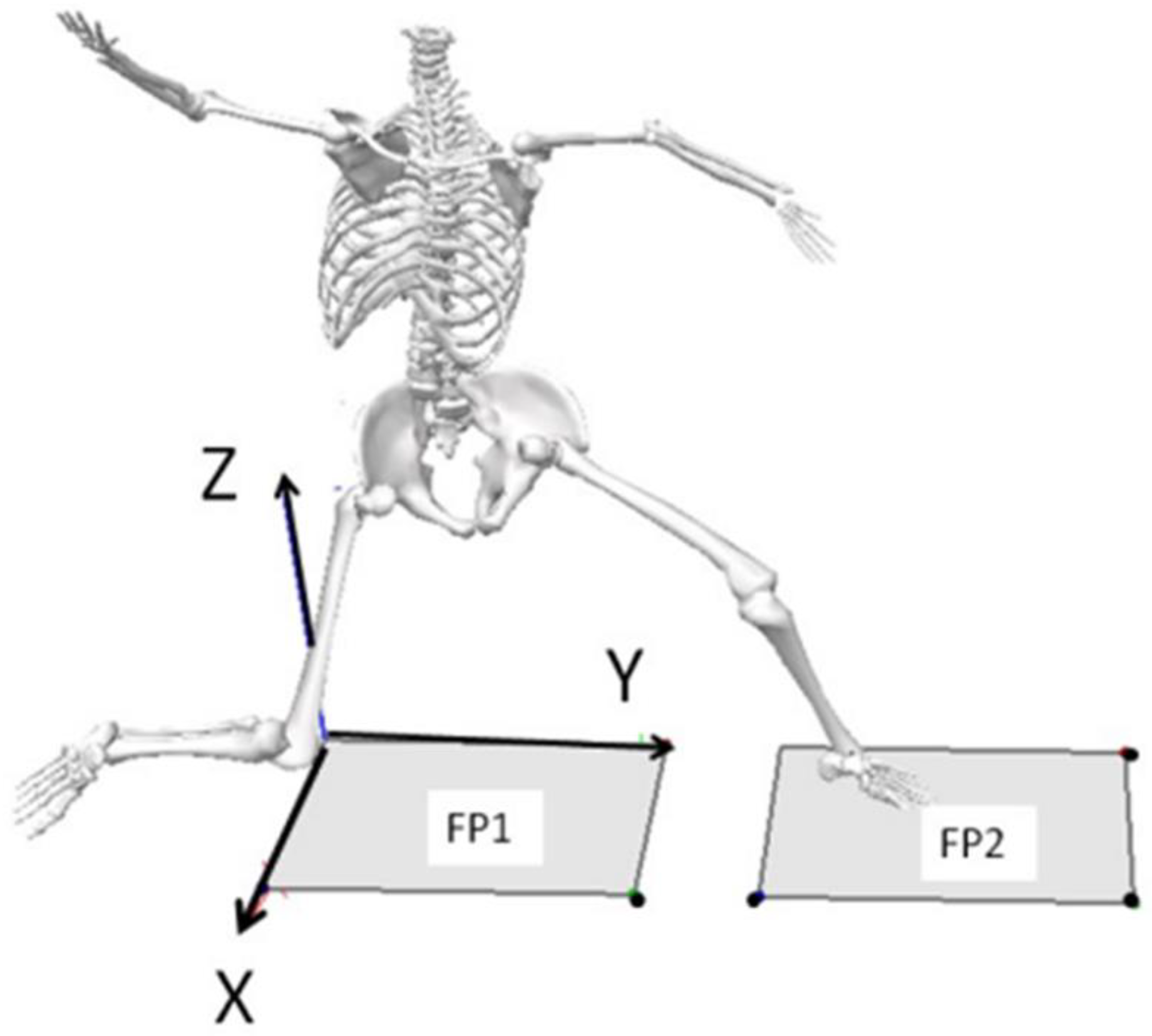

2. Materials and Methods

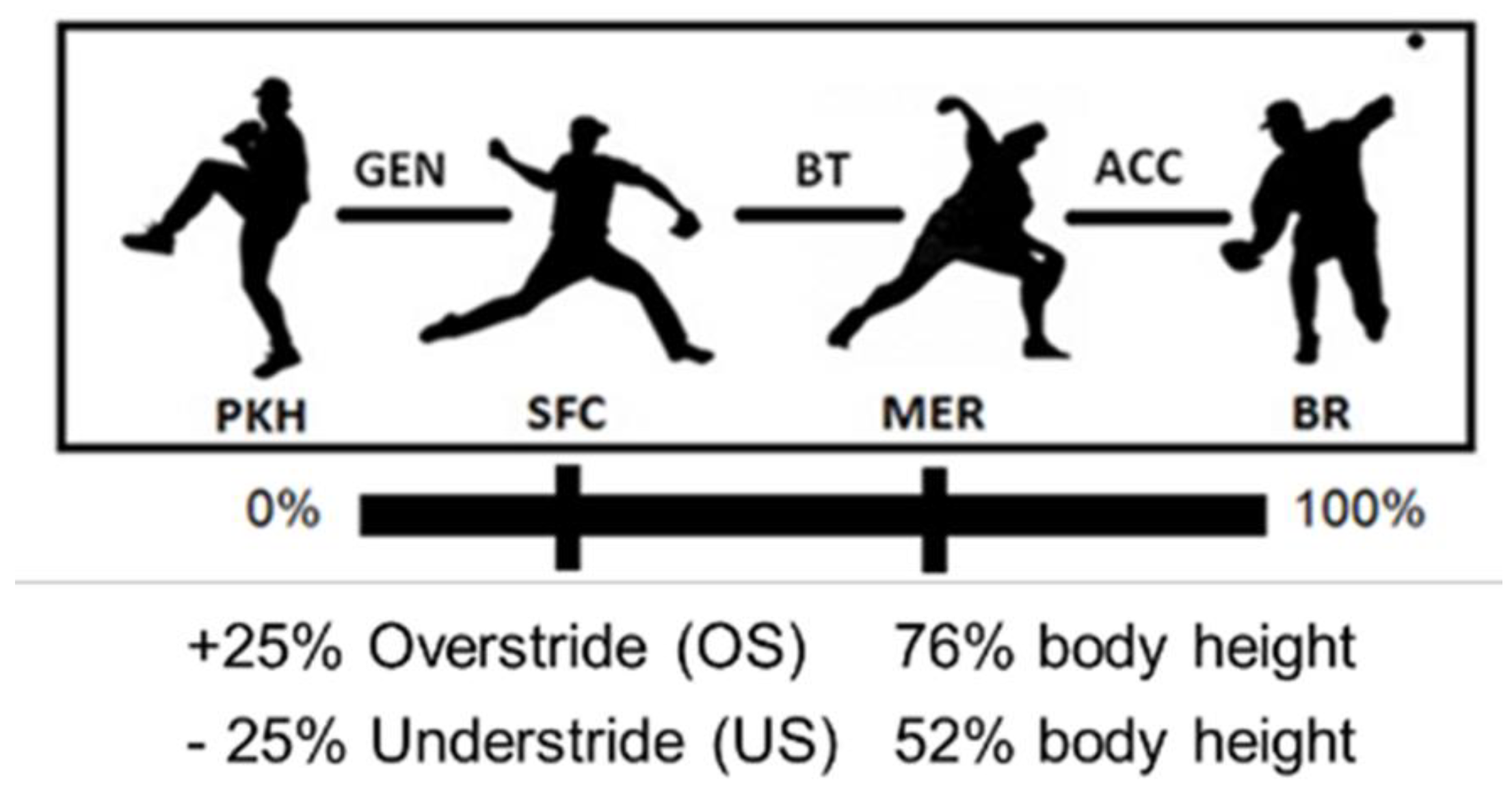

- (i)

- Generation (GEN) Phase: from PKH to SFC

- (ii)

- Brace-Transfer (BT) Phase: between SFC to MER, and

- (iii)

- Acceleration (ACC) Phase: from MER to BR.

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

Transverse Plane Kinematics

4. Discussion

Considerations and limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PTS | Axial pelvic-trunk separation |

| PPE | Proximal plyometric effect |

| OS | Over-stride |

| US | Under-stride |

| PKH | Peak knee height |

| SFC | Stride foot contact |

| MER | maximal external rotation |

| BR | ball release |

| GEN | Generation Phase |

| BT | Brace-Transfer Phase |

| ACC | Acceleration Phase |

References

- Crotin, R. L., Kozlowski, K., Horvath, P., and Ramsey, D. K. (2014). “Altered stride length in response to increasing exertion among baseball pitchers.” Med Sci Sports Exerc., 46(3), 565-571.

- Ramsey, D. K., Crotin, R. L.*, White, S., (2014). Effect of stride length on overarm throwing delivery: A linear momentum response. Hum Mov Sci. 38, 185-196.

- Crotin, R. L., and Ramsey, D. K. (2015). “Stride length: A Reactive Response to Prolonged Exertion and its Effect on Ball Velocity Among Baseball Pitchers.” Int J Perform Anal Sport., 15(1), 254-267.

- Crotin, R. L., Bhan, S., and Ramsey, D. K. (2015). “An inferential investigation into how stride length influences temporal parameters within the baseball pitching delivery.” Hum Mov Sci., 41.

- Ramsey, D.K., and Crotin, R.L.* (2016) “Effect of Stride Length on Overarm Throwing Delivery: Part II: An Angular Momentum Response”. Hum Mov Sci., 46, 30-38.

- Ramsey DK. and Crotin RL. Stride length: The Impact on Propulsion and Bracing Ground Reaction Force in Overhand Throwing. Sports Biomech. (2019) 18:5, 553-570.

- Crotin R, Ramsey D. Grip Strength Measurement in Baseball Pitchers: A Clinical Examination to Indicate Stride Length Inefficiency. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy 2021;16(5):1330-1337.

- Ramsey DK and Crotin RL. Stride Length Impacts on Sagittal Knee Biomechanics in Flat Ground Baseball Pitching. Applied Sciences. Special Issue: Applied Biomechanics: Sport Performance and Injury Prevention II. 2022; 12(3):995.

- Crotin RL and Ramsey DK. An Exploratory Investigation Evaluating the Impact of Fatigue-Induced Stride Length Compensations on Ankle Biomechanics among Skilled Baseball Pitchers. Life. 2023; 13(4):986.

- Aguinaldo AL, Buttermore J, Chambers H. Effects of upper trunk rotation on shoulder joint torque among baseball pitchers of various levels. J Appl Biomech. 2007;23(1):42-51.

- Wight J, Richards J, Hall S. Influence of pelvis rotation styles on baseball pitching mechanics. Sports Biom. 2004;3(1):67-83.

- Dowling B, Knapik DM, Luera MJ, Garrigues GE, Nicholson GP, Verma NN. Influence of Pelvic Rotation on Lower Extremity Kinematics, Elbow Varus Torque, and Ball Velocity in Professional Baseball Pitchers. Orthop J Sports Med. 2022;10(11):23259671221130340. Published 2022 Nov 29. [CrossRef]

- Crotin, Ryan Lewis. A kinematic and kinetic comparison of baseball pitching mechanics influenced by stride length. State University of New York at Buffalo ProQuest Dissertations & Theses, 2013. 3565735.

- Elliot, B., Grove, J. R., and Gibson, B. (1988). Timing of the lower limb drive and throwing limb movement in baseball pitching. Int J Sports Biomech, 4(1), 59-67.

- Elliott, B., Grove, J., Gibson, B., and Thurston, B. (1986). A three-dimensional cinematographic analysis of the fastball and curveball pitches in baseball. Int J Sport Biomech, 2, 20-28.

- Escamilla, R. F., Barrentine, S. W., Fleisig, G. S., Zheng, N., Takada, Y., Kingsley, D., and Andrews, J. R. (2007). Pitching biomechanics as a pitcher approaches muscular fatigue during a simulated baseball game. Am J Sports Med, 35(1), 23.

- Escamilla, R. F., Fleisig, G. S., Barrentine, S. W., Zheng, N., and Andrews, J. R. (1998). Kinematic comparisons of throwing different types of baseball pitches. J Appl Biomech, 14, 1.

- Fleisig, G. S., Bolt, B., Fortenbaugh, D., Wilk, K. E., and Andrews, J. R. (2011). Biomechanical comparison of baseball pitching and long-toss: implications for training and rehabilitation. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther, 41(5), 296.

- Fleisig, G. S., Kingsley, D. S., Loftice, J. W., Dinnen, K. P., Ranganathan, R., Dun, S., and Andrews, J. R. (2006). Kinetic comparison among the fastball, curveball, change-up, and slider in collegiate baseball pitchers. Am J Sports Med, 34(3), 423.

- Guo, L. Y., Lin, W. Y., Tsai, Y. J., Hou, Y. Y., Chen, C. C., Yang, C. H., and Liu, Y. H. (2010). Different Limb Kinematic Patterns during Pitching Movement Between Amateur and Professional Baseball Players. J Med Bio Eng, 30(3), 177-180.

- Aguinaldo A, Chambers H. Correlation of throwing mechanics with elbow valgus load in adult baseball pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(10):2043.

- Oi T, Takagi Y, Tsuchiyama K, et al. Three-dimensional kinematic analysis of throwing motion focusing on pelvic rotation at stride foot contact. JSES Open Access. 2018;2(1):115-119. Published 2018 Feb 21. [CrossRef]

- Crotin RL, Ramsey DK. Injury Prevention for Throwing Athletes Part I: Baseball Bat Training to Enhance Medial Elbow Dynamic Stability. Strength Cond J. 2012;34(2):79.

- Lin HT, Su FC, Nakamura Dowling B, Knapik DM, Luera MJ, Garrigues GE, Nicholson GP, Verma NN. Influence of Pelvic Rotation on Lower Extremity Kinematics, Elbow Varus Torque, and Ball Velocity in Professional Baseball Pitchers. Orthop J Sports Med. 2022;10(11):23259671221130340. Published 2022 Nov 29. [CrossRef]

- Fleisig GS, Andrews JR, Dillman CJ, Escamilla RF. Kinetics of baseball pitching with implications about injury mechanisms. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23(2):233.

- Dun S, Fleisig GS, Loftice J, Kingsley D, Andrews JR. The relationship between age and baseball pitching kinematics in professional baseball pitchers. J Biomech. 2007;40(2):265-270.

- Logan G, McKinney W. The serape effect. In: Anatomic Kinesiology (3rd ed.). A. Lockhart, ed. Dubuque, IA: Brown. 1970:287-302.

- Santana JC. The serape effect: A kinesiological model for core training. Strength Cond J. 2003;25(2):73. M, Chao EYS. Complex chain of momentum transfer of body segments in the baseball pitching motion. J Chinese Inst Eng. 2003;26(6):861-868.

- Stodden DF, Fleisig GS, McLean SP, Andrews JR. Relationship of biomechanical factors to baseball pitching velocity: within pitcher variation. J Appl Biomech. 2005;21(1):44-56.

- Fleisig GS, Kingsley DS, Loftice JW, et al. Kinetic comparison among the fastball, curveball, change-up, and slider in collegiate baseball pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(3):423.

- Grantham WJ, Byram IR, Meadows MC, Ahmad CS. The Impact of Fatigue on the Kinematics of Collegiate Baseball Pitchers. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine. 2014 vol. 2 no. 6. [CrossRef]

- Fleisig GS, Bolt B, Fortenbaugh D, Wilk KE, Andrews JR. Biomechanical comparison of baseball pitching and long-toss: implications for training and rehabilitation. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2011;41(5):296.

- Nissen CW, Solomito M, Garibay E, Õunpuu S, Westwell M. A Biomechanical Compar-ison of Pitching From a Mound Versus Flat Ground in Adolescent Baseball Pitchers. Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach. 2013;5(6):530-536.

- Badura J, Raasch W, Barber M, Harris G. A kinematic and kinetic biomechanical model for baseball pitching and its use in the examination and comparison of flat-ground and mound pitching: a preliminary report. Paper presented at: Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, 2003. Proceedings of the 25th Annual International Conference of the IEEE, 2003.

| STRIDE LENGTH |

Generation PKH to SFC (% Time) |

Brace-Transfer SFC to MER (% Time) |

Acceleration MER to BR (% Time) |

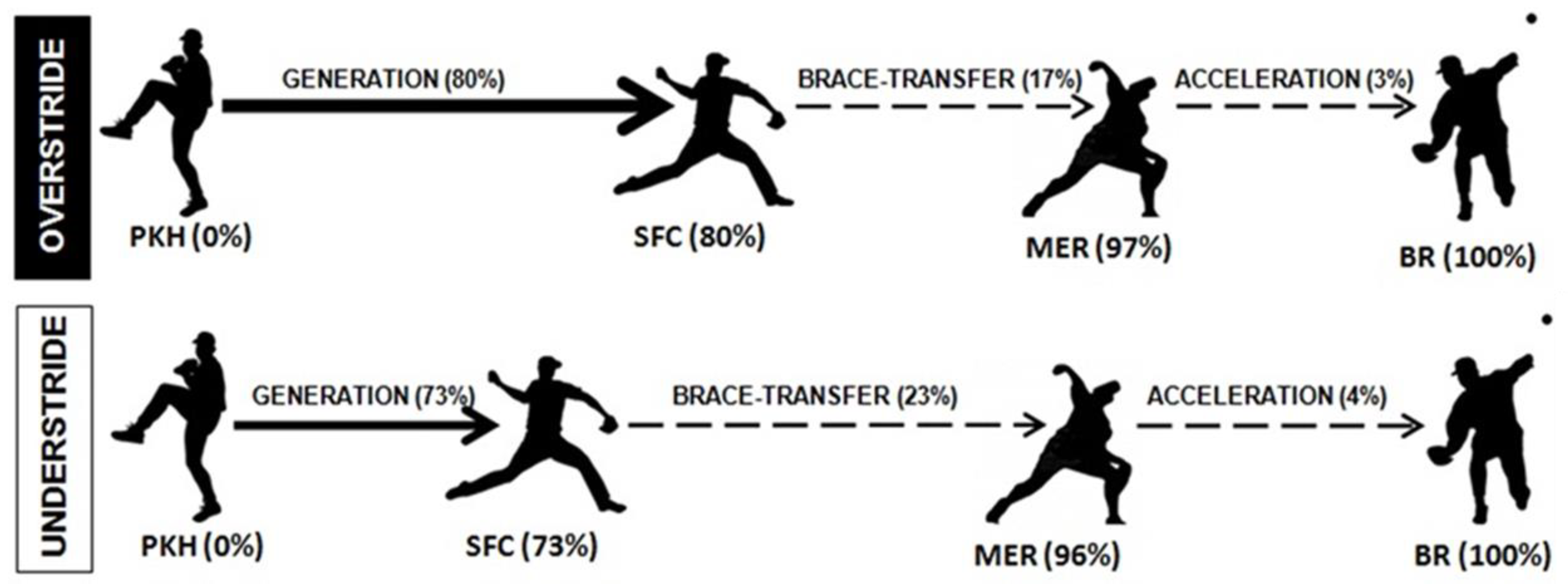

| OVERSTRIDE | 79.95 (2.79)** | 16.95 (3.18)** | 3.10 (1.39) |

| UNDERSTRIDE | 73.25 (4.68) | 23.20 (4.84) | 3.55 (1.46) |

| PKH | SFC | MER | BR | GEN | BT | ACC | ||

|

Pelvis Angle (°) |

OVER-STRIDE |

-115.9 (36.5) |

-61.0** (21.1) | 1.74 (7.53) |

7.79 (7.87) |

-103.6** (16.1) | -27.3* (19.8) | 5.87 (1.79) |

|

UNDER-STRIDE |

-112.7 (38.8) |

-85.2 (15.0) |

1.88 (12.1) |

10.7 (10.7) |

-110.9 (9.63) |

-44.5 (28.2) |

7.72 (2.71) |

|

|

Pelvis Velocity (°/s) |

OVER-STRIDE |

-13.8 (35.5) |

417.7 (90.1) |

283.1 (120.2) |

92.7 (92.7) |

118.8** (88.9) | 461.6 (71.3) |

157.6 (58.6) |

| UNDER-STRIDE | 9.44 (56.4) |

302.6 (166.9) |

357.4 (146.1) |

95.0 (126.2) |

73.3 (53.7) |

506.0 (99.0) |

203.1 (93.0) |

|

| TrunkAngle (°) | OVER-STRIDE | -108.7 (27.6) |

-99.9* (25.3) | -15.8 (7.82) |

-2.96 (6.28) |

-114.8** (3.41) | -60.7* (27.4) | -7.29 (3.95) |

| UNDER-STRIDE | -106.9 (28.5) |

-116.5 (13.1) |

-17.8 (12.4) |

2.02 (8.93) |

-116.5 (1.67) |

-79.9 (31.6) |

-5.45 (6.42) |

|

|

Trunk Velocity (°/s) |

OVER-STRIDE | -13.7 (30.7) |

334.4* (191.9) | 474.9* (105.3) | 255.1 (86.6) |

30.3** (64.0) | 621.2 (123.9) |

333.7 (67.1) |

| UNDER-STRIDE | -9.94 (38.5) |

141.9 (185.1) |

601.3 (149.3) |

307.3 (114.4) |

4.46 (20.5) |

562.8 (235.4) |

444.3 (105.0) |

|

Pelvis Internal Rotation |

% TIME |

Trunk Internal Rotation |

% TIME |

|||

|

Peak Angular Velocity (°/s) |

OVER-STRIDE | 584.1** (62.7) |

85.4 (8.71) |

OVER-STRIDE | 797.0* (82.5) |

89.8 (3.78) |

| UNDER-STRIDE | 658.9 (73.3) |

87.5 (3.47) |

UNDER-STRIDE | 851.0 (94.2) |

90.3 (2.43) |

| PKH | SFC | MER | BR | GEN | BT | ACC | ||

|

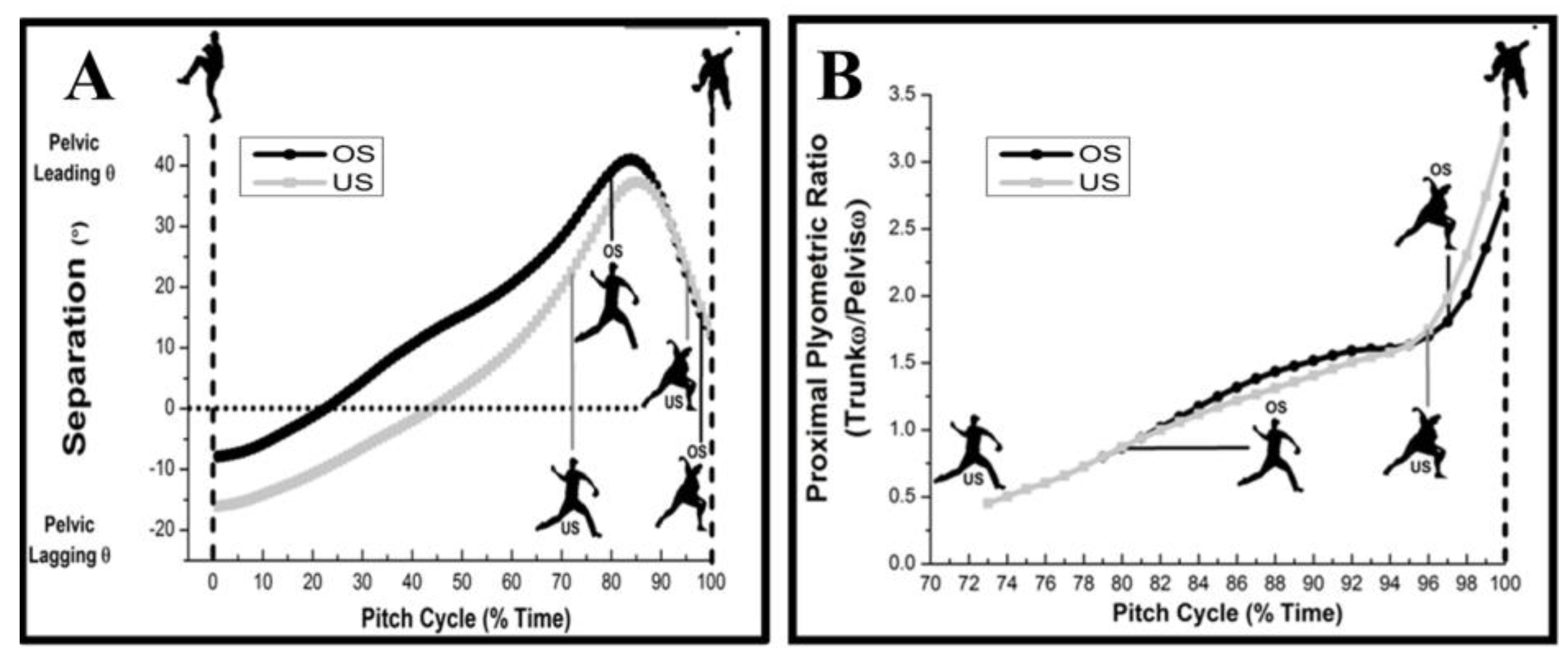

Separation Angle (°) |

OVERSTRIDE | -7.89* (26.7) | 38.9*(9.40) | 17.5 (10.5) |

10.7 (8.92) |

11.2**(13.5) | 33.4 (8.04) |

13.2 (2.16) |

| UNDERSTRIDE | -16.1 (30.0) |

25.3 (24.1) |

20.0 (10.3) |

10.9 (16.1) |

-1.45 (11.2) |

31.7 (4.89) |

14.7 (3.17) |

|

|

Proximal Plyometric Effect (Trunkω/Pelvisω) |

OVERSTRIDE | 1.53 (1.18) |

0.77 (0.39) |

1.81 (0.51) |

2.75* (0.28) | 1.34 (1.76) |

1.53* (0.69) | 2.23* (0.41) |

| UNDERSTRIDE | 1.36 (2.10) |

0.53 (0.34) |

1.75 (0.73) |

3.37 (0.22) |

1.53 (1.96) |

1.05 (0.40) |

2.40 (0.60) |

|

| Angle | % time | Ratio | % Time | |||||

|

Peak Separation (°) |

OVERSTRIDE | 41.2 (5.38) |

84.1 (6.13) |

Peak Plyometric Ratio (Trunkω/Pelvisω) |

OVERSTRIDE | 2.75* (0.28) | 98.0 (1.25) |

|

| UNDERSTRIDE | 37.3 (7.83) |

85.4 (7.84) |

UNDERSTRIDE | 3.37 (0.12) |

98.6 (1.15) |

|||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).