1. Introduction

Pancreatic cancer is among the most malignant tumors of the digestive system, and surgical resection remains the preferred therapeutic strategy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PAAD). Due to the extremely poor prognosis of this invasive disease, compounded by the fact that most patients are diagnosed at an advanced stage, only 15–20% of patients are eligible for surgical intervention at diagnosis, leading to one-year and five-year survival rates of 24% and 9%, respectively [1]. In recent years, the combination of first-line chemotherapy regimens such as FOLFIRINOX with agents including nivolumab (a PD-1 inhibitor) and nimotuzumab (an EGFR inhibitor) has modestly improved the survival rate of patients with PAAD. However, the overall therapeutic efficacy remains unsatisfactory [2,3]. Consequently, there is an urgent need to develop new therapeutic targets and establish prognostic models capable of evaluating patient outcomes to guide clinical decision-making.

The centrosome is the primary microtubule (MT) organizing center in animal cells, playing a pivotal role in cell polarity, migration, and cell division. It consists of a pair of orthogonally oriented centrioles that replicate during the S phase of the cell cycle and are equally distributed to the two daughter cells during mitosis, thereby forming the two poles of the mitotic spindle [4]. Over a century ago, Boveri first proposed that an increase in the number of centrosomes could lead to tumorigenesis [5]. In recent years, centrosome amplification—an aberrant increase in the number of centrosomes within a cell—has been recognized as a hallmark of cancer [6]. However, the specific factors that induce centrosome amplification and how they influence tumor development remain to be fully elucidated. Existing research indicates that alterations in the proteins involved in centrosome replication can trigger abnormal centrosome amplification. For instance, dysregulation of PLK4 disrupts centriole replication and causes abnormal numbers of centrosomes; Mittal K et al. identified a hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF1α)/PLK4 axis that drives centrosome amplification in cancer cells, promoting cell migration and invasion [7]. Additionally, the cell division cycle protein Cdc6, which interacts with Sas-6 under Plk4 regulation, suppresses excessive centrosome replication. One study demonstrated that knocking down Cdc6 promotes apoptotic cell death, accompanied by the activation of calpain-1 and caspase-9; these processes play crucial roles in the proliferation, cell cycle progression, and death of pancreatic cancer cells [8]. Nevertheless, most previous work has focused on the functions of individual genes rather than on a global transcriptomic analysis of centrosome amplification–related genes (CARGs). Therefore, a systematic investigation of CARGs in PAAD is warranted to gain novel insights into the underlying mechanisms of tumorigenesis and to identify new targets for cancer prevention and therapy.

In this study, we performed a comprehensive analysis of CARGs in 177 PAAD patients from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) dataset. We initially retrieved 724 Centrosome amplification-related genes from the GeneCards database. Of these, 23 showed elevated expression in PAAD tissues. Subsequently, using univariate Cox, LASSO-penalized Cox regression and multivariate Cox, we identified a five-gene signature (IFI27, KIF20A, KLK10, SPINK7, and TOP2A) from these 23 CARGs. We next investigated the associations between this centrosome amplification–related prognostic signature and immune infiltration, pathway enrichment, genetic mutations, and chemosensitivity in pancreatic cancer. Single-cell RNA sequencing data were utilized to investigate the expression patterns of the 5-gene signature across different pancreatic cell types and their intricate intercellular communication networks. Spatial transcriptomic analysis revealed the spatial distribution and molecular biological interactions associated with the signature. Finally, qPCR validation was performed using surgical specimens of pancreatic cancer.

4. Discussion

A growing body of both preclinical and clinical evidence suggests that centrosome amplification–related genes may serve as potential therapeutic targets in PAAD. Nevertheless, the precise role of centrosome amplification in tumorigenesis remains to be fully elucidated. In the present study, we conducted functional enrichment analysis of DEGs between PAAD and paired non-tumor tissues, providing preliminary evidence for the pivotal role of centrosome amplification in PAAD. We identified 23 genes that were both overexpressed in PAAD and associated with centrosome amplification. Subsequently, we developed a five-gene CARG-based signature that demonstrated robust diagnostic and prognostic performance in patients with PAAD. Collectively, our work offers a comprehensive transcriptomic analysis of centrosome amplification–related genes, shedding light on the function of centrosomes in PAAD.

Our CARG-based signature comprises IFI27, KIF20A, KLK10, SPINK7, and TOP2A. IFI27 (Interferon Alpha Inducible Protein 27), which is induced by interferon-α and located on chromosome 14q32 [12], is upregulated in multiple malignancies and associated with tumor proliferation, invasion, metastasis, and drug resistance. Originally cloned in the estrogen-induced MCF-7 breast cancer cell line, IFI27 has been linked to enhanced proliferation and migration in breast cancer, potentially by promoting epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) [13]. IFI27 also plays roles in the progression and drug resistance of ovarian cancer, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, and gastric cancer [14,15,16]. Moreover, IFI27 has been proposed as a potential prognostic biomarker in pancreatic cancer, where its overexpression correlates with increased cell proliferation, metastasis, and malignant progression [17]. Notably, IFI27 might modulate immune evasion and cell survival in pancreatic cancer cells by interfering with RIG-I signaling, although further study is warranted [18].

KIF20A (kinesin family member 20A) binds to microtubules and generates mechanical force through ATP hydrolysis, playing a crucial role in cell division [19]. Studies have revealed that KIF20A promotes tumor growth by regulating chromosome segregation, whereas its inhibition markedly attenuates the proliferation of pancreatic cancer cells. Overexpression of KIF20A in pancreatic tumors typically correlates with increased invasiveness and poor prognosis [20,21], suggesting its potential as a therapeutic target.

KLK10 (kallikrein-related peptidase 10), also known as normal epithelial cell–specific 1 (NES1), is a member of the human kallikrein-related peptidase family. Located on chromosome 19q13.3, it encodes a serine protease involved in cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis [22]. High KLK10 levels are associated with poor prognosis in certain cancers, including pancreatic cancer, where it may drive malignant progression by facilitating cell proliferation and migration. Moreover, KLK10 is aberrantly upregulated in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) and pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN), further implicating KLK10 in PDAC initiation and progression [23].

SPINK7 (serine peptidase inhibitor, Kazal type 7) was initially identified in studies aiming to uncover genes linked to human esophageal cancer [24]. Interestingly, SPINK7 has been reported to promote apoptosis by directly binding uPA, potentially suppressing tumor progression via the p53 pathway and playing an important role in overcoming drug resistance in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma [25]. Contrary to these findings, our data indicate that SPINK7 is highly expressed in pancreatic cancer tissues and correlates with poor prognosis. Few studies have addressed SPINK7 in PAAD, and no significant relationship has been reported between SPINK7 short tandem repeat (STR) polymorphisms and reduced pancreatic cancer risk or improved overall survival [26]. Hence, the role of SPINK7 in pancreatic cancer warrants further investigation.

TOP2A (topoisomerase IIα) is overexpressed in pancreatic cancer and linked to worse survival outcomes [27]. By activating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, TOP2A accelerates pancreatic tumor proliferation and migration. Knocking down TOP2A substantially hinders these oncogenic processes, underscoring its potential as a therapeutic target [28]. Consistent with previous reports, our findings suggest that these five genes strongly correlate with aggressive tumor behavior and chemotherapy resistance. Moreover, our results confirm that this five-gene signature is an independent predictor of overall survival, even when adjusting for established clinicopathological risk factors.

At present, CA19-9 remains the most widely employed blood-based biomarker for PAAD diagnosis, but its sensitivity is only 68.8% [29]. While CA19-9 is useful, its limited sensitivity necessitates the combined application of other diagnostic methods to enhance accuracy. Notably, our five-gene signature exhibits considerable sensitivity and specificity in distinguishing PAAD patients from both healthy controls and those with premalignant lesions. Therefore, this CARG-based signature may serve as a valuable biomarker for the diagnosis and prognosis of patients with PAAD.

To further elucidate the potential mechanisms by which centrosome amplification contributes to malignant progression and poor prognosis in PAAD patients, we investigated its relationship with the cell cycle and the tumor microenvironment. Dysregulated cell cycle progression leads to tumorigenesis and cancer development and is widely recognized as an important characteristic of cancer [30]. Indeed, uncontrolled cell proliferation—mediated by aberrant cell cycle regulation and activation of cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs)—is central to the pathological processes of cancer. Cell cycle regulators have long been pivotal targets in cancer therapy. For example, the next-generation selective CDK4/6 inhibitor palbociclib has been approved for treating HR+/HER2− advanced breast cancer [31]. Samuraciclib, a novel noncovalent, ATP-competitive CDK7 inhibitor, can effectively suppress proliferation of various cancer cells at lower concentrations and significantly inhibit tumor growth in a mouse xenograft model of colon cancer without evident side effects [32]. Under normal conditions, centrosome amplification is tightly controlled throughout the cell cycle, but when cell division fails, disrupted CDK activity triggers centrosome expansion, resulting in multipolar spindle formation and erroneous chromosome segregation—ultimately leading to aneuploidy and malignant transformation [33,34]. Consistent with these findings, our study showed that patients in the high-CARGs-risk group had significantly enriched cell cycle–related pathways, highlighting a close association between cell cycle dysregulation and centrosome amplification. In addition, patients with high CARGs scores appeared to exhibit greater activity in the PI3K/AKT/mTOR, Notch, p53, and TGF-β pathways, suggesting that centrosome amplification is intricately linked to multiple oncogenic signaling cascades.

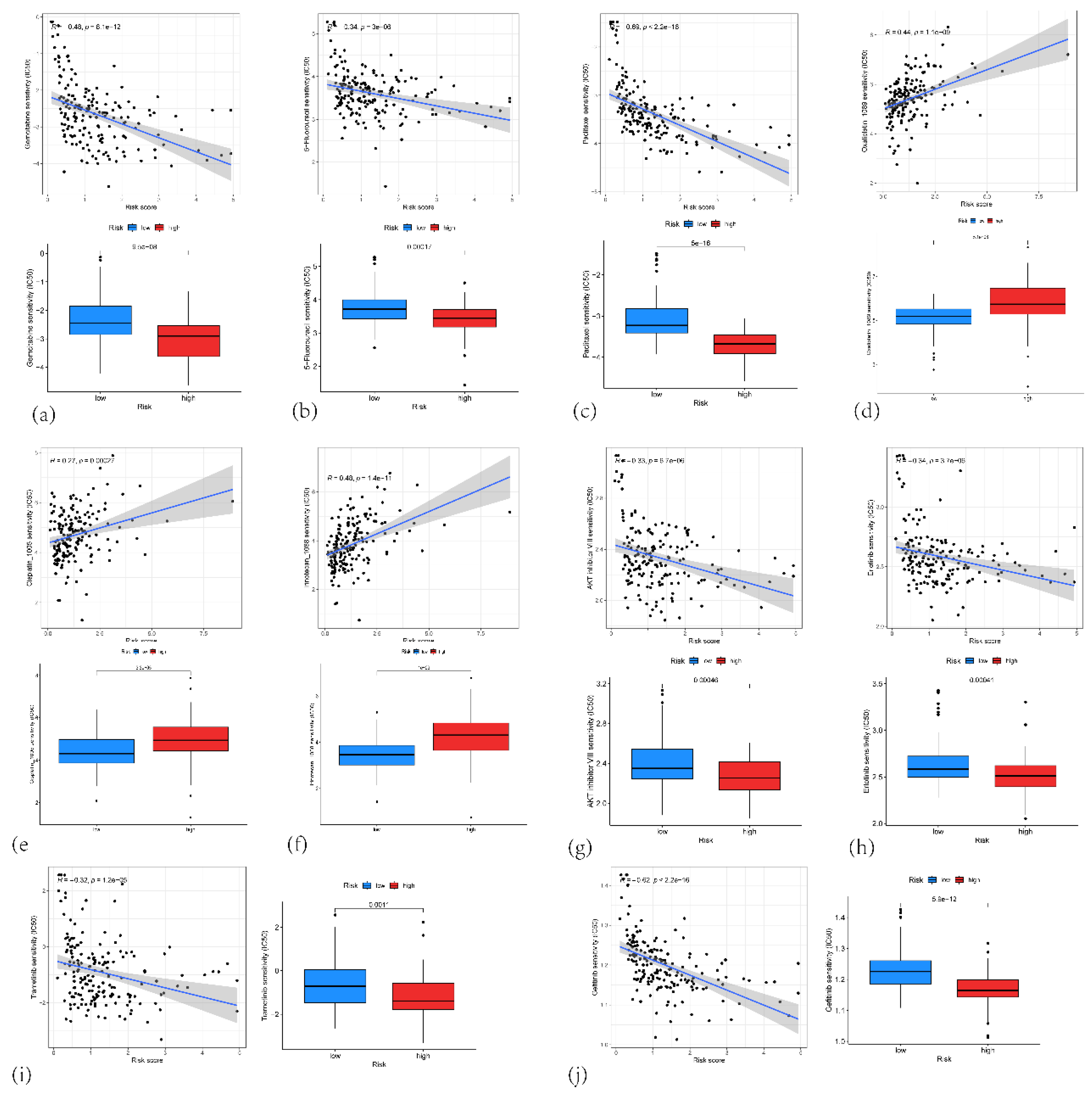

In our drug-sensitivity analysis, high-risk patients demonstrated a greater propensity for resistance to DNA synthesis inhibitors (gemcitabine, 5-FU), platinum-based drugs (oxaliplatin and cisplatin, which form platinum-DNA adducts blocking DNA replication and transcription) and the topoisomerase I inhibitor (irinotecan) [35,36,37,38]. Their efficacy in the low-risk group may be attributed to these tumors’ reliance on DNA damage responses. Enhanced DNA repair can facilitate the correction of topoisomerase I inhibitor–induced DNA breaks, diminishing the cytotoxic impact of irinotecan [39], which may correlate with our observation that DNA repair pathways are enriched in the high-risk group. As a microtubule inhibitor [40], paclitaxel displayed lower IC50 values in the high-risk group, potentially because cells with more active cell cycle–related pathways are faster-dividing and thus more vulnerable to microtubule disruption. Likewise, certain tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs)—such as gefitinib and erlotinib, which primarily target the EGFR pathway [41]—may exert enhanced antitumor effects in the high-risk group because of the elevated activity of EGFR and its downstream PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling in these patients. Trametinib, a MEK inhibitor that acts on the RAS downstream MEK/ERK pathway [42], could also be more effective in the high-risk group, given the high-level activation of RAS signaling in pancreatic cancer.

A high KRAS mutation frequency is one of the most prominent characteristics of pancreatic cancer. The MAPK pathway, which is closely integrated with the cell cycle, orchestrates Ras activation to promote tumor cell proliferation, survival, and migration [43]. The Ras oncogene can signal centrosome amplification through cyclin D1/Cdk4 and Nek2, promoting tumorigenesis [44]. TP53, a tumor suppressor gene closely linked to cell cycle control, has been implicated in early centrosome amplification, with some studies suggesting that its function is lost due to both the loss of wild-type TP53 expression and hotspot mutations [45]. In our study, KRAS and TP53 mutations were significantly more frequent in the high-risk group than in the low-risk group, further affirming that TP53 and KRAS mutations play critical roles in centrosome amplification.

Previous research indicates that centrosome amplification can induce spindle multipolarity during cell division, leading to chromosomal missegregation and ultimately chromosomal instability (CIN). CIN, a hallmark in many cancers, has been shown to correlate with tumor progression and poor prognosis [46]. Apart from directly increasing genomic instability in tumor cells, CIN caused by centrosome amplification also alters the tumor microenvironment by secreting various cytokines and chemokines. These secreted factors can recruit and reprogram macrophages, promoting M0 macrophage infiltration and polarization toward an M2 phenotype—for instance, tumor-secreted chemokines such as CCL2 can attract M0 macrophages and induce M2 polarization via signaling pathways such as STAT3 [47]. Importantly, aneuploidy in tumor cells is associated with increased M2 macrophage populations and reduced cytotoxic T cells [48]. Similarly, CIN tumors show activation of suppressive inflammatory pathways (including cGAS/STING/APP), inducing immunosuppressive signals such as TGF-β and IL-10 that drive M0 macrophages toward M2 differentiation and exhibit defective MHC class I antigen presentation [49]. In agreement with previous reports, our findings demonstrated that, from an immune-function perspective, the low-risk group exhibited significantly higher Type II IFN Response and cytolytic activity than the high-risk group, whereas the Type I IFN Response, para-inflammation, MHC class I expression, and APC co-inhibition scores were significantly lower than those of the high-risk group. These observations imply that the low-risk group has stronger antitumor immunity, while the high-risk group displays more pronounced immunosuppressive features. Patients with high CARGs scores showed reduced infiltration of antitumor immune cells—such as activated CD8+ T cells, activated B cells, and monocytes—alongside an elevated infiltration of immunosuppressive Th2 cells. Additionally, increased infiltration of M0 macrophages in the high-risk group may represent an undifferentiated macrophage state prone to M2 polarization under proper stimuli, thereby facilitating tumor progression and immune evasion. Although our study noted a marked elevation in activated CD4+ T cells in the high-risk group, this observation does not necessarily contradict the conclusion of enhanced immunosuppression. CD4+ T cells can differentiate into a variety of subtypes, including helper T cells (Th1, Th2, Th17) and regulatory T cells (Tregs). While activated CD4+ T cell counts may be higher in the high-risk group, a larger proportion could be Tregs, which exert immunosuppressive effects, thereby augmenting the overall immunosuppressive environment. Moreover, the higher MDSC scores observed in the low-risk group might reflect an immune editing mechanism that modulates immune responses. Several immune checkpoints, including CD274 (PD-L1), CD276, CD44, and TNFSF9, were also elevated in patients with high CARGs scores. Therapeutics targeting these molecules may hold promise for high-risk individuals and warrant further investigation. However, the TCIA analysis indicated no clear difference in response to CTLA-4 or PD-L1 blockade therapy between the risk groups, possibly attributable to pancreatic tumors being viewed as “cold tumors” [50], which generally respond poorly to immunotherapy. Hence, immunotherapeutic strategies for pancreatic malignancies require deeper investigation. Predictions of ICB therapy indicate that high-risk tumors may experience greater immune escape, leading to inferior responses to ICB. Thus, the CARGs score could serve as a biomarker to identify patients more likely to benefit from such treatments.

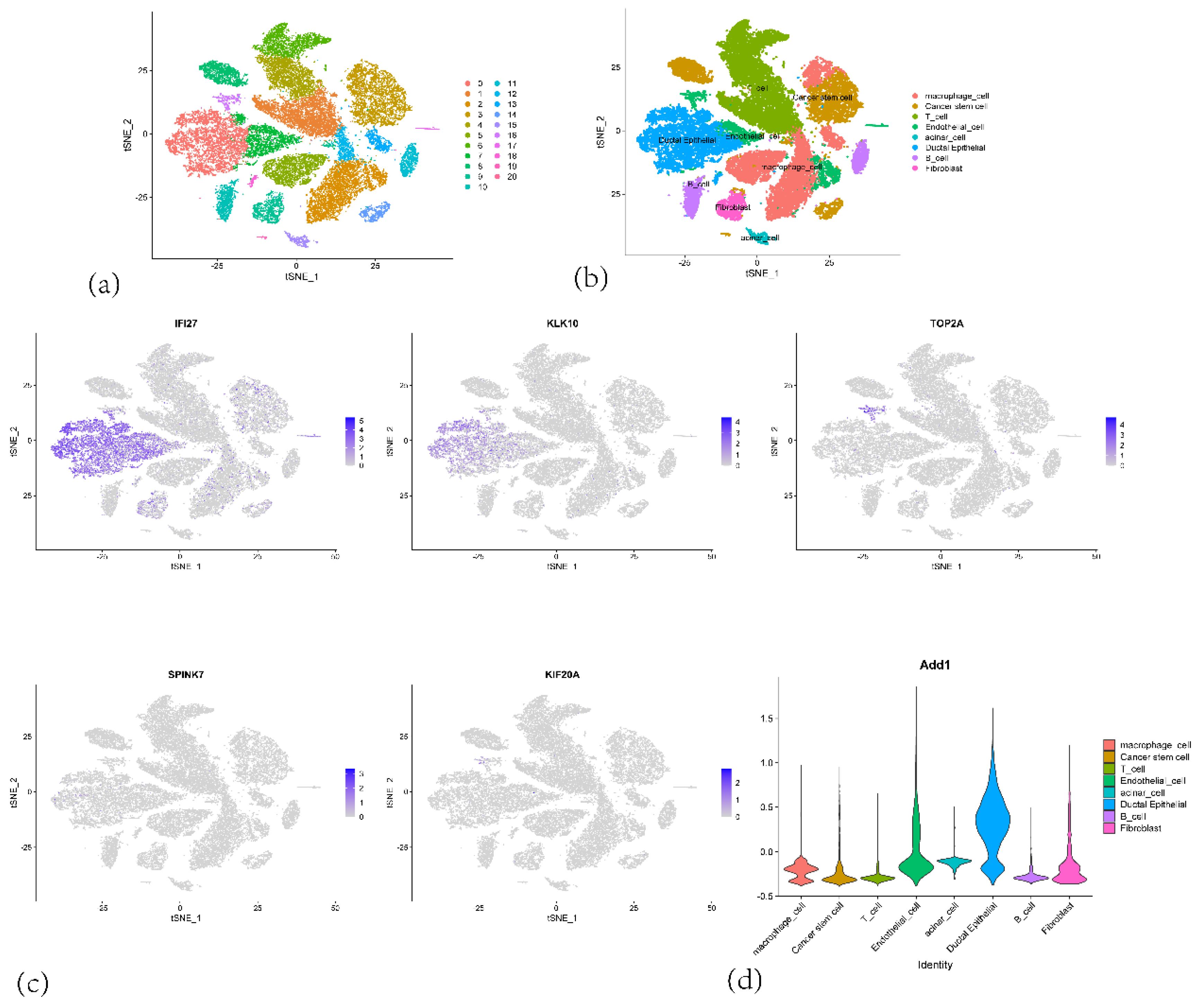

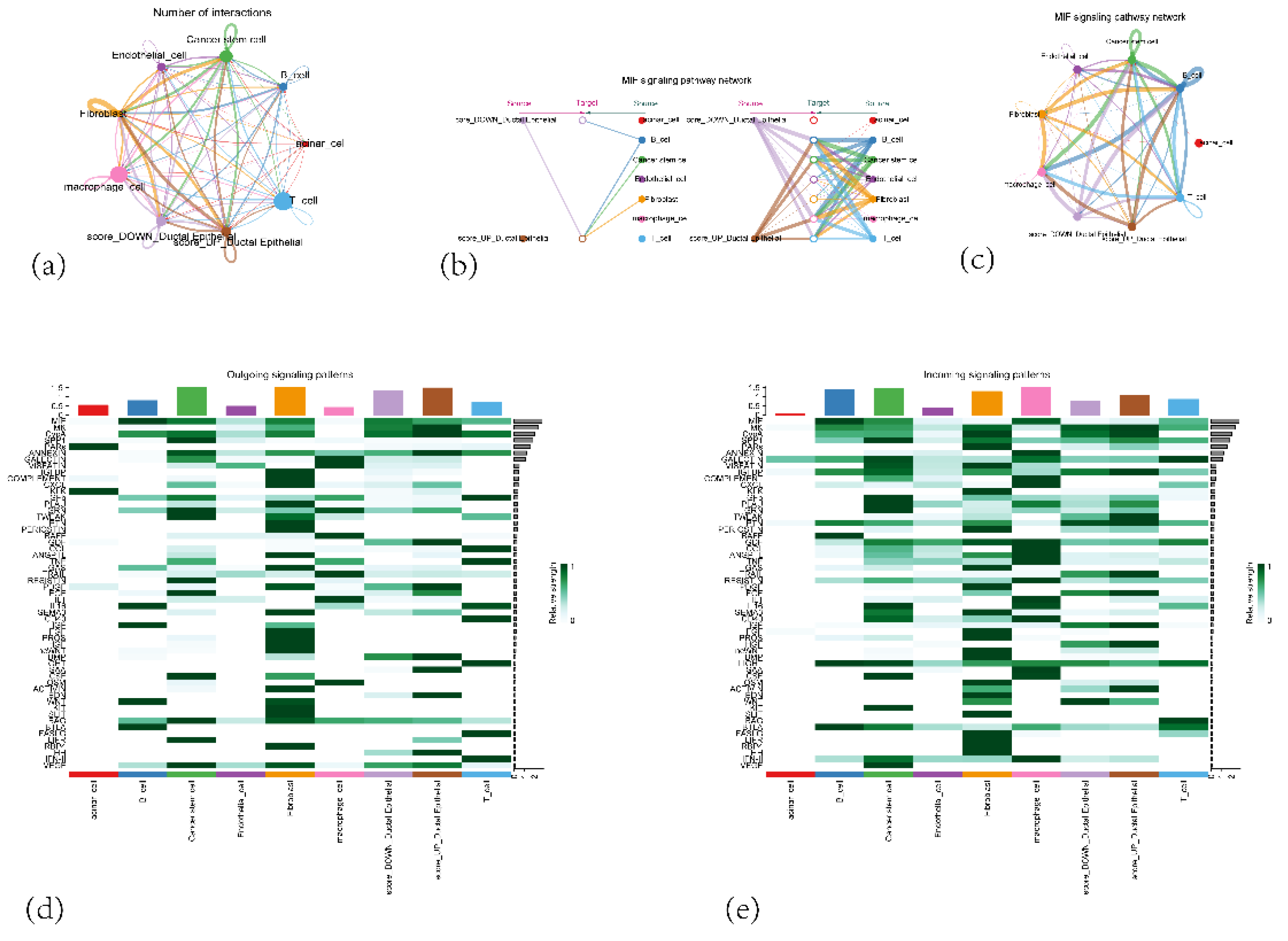

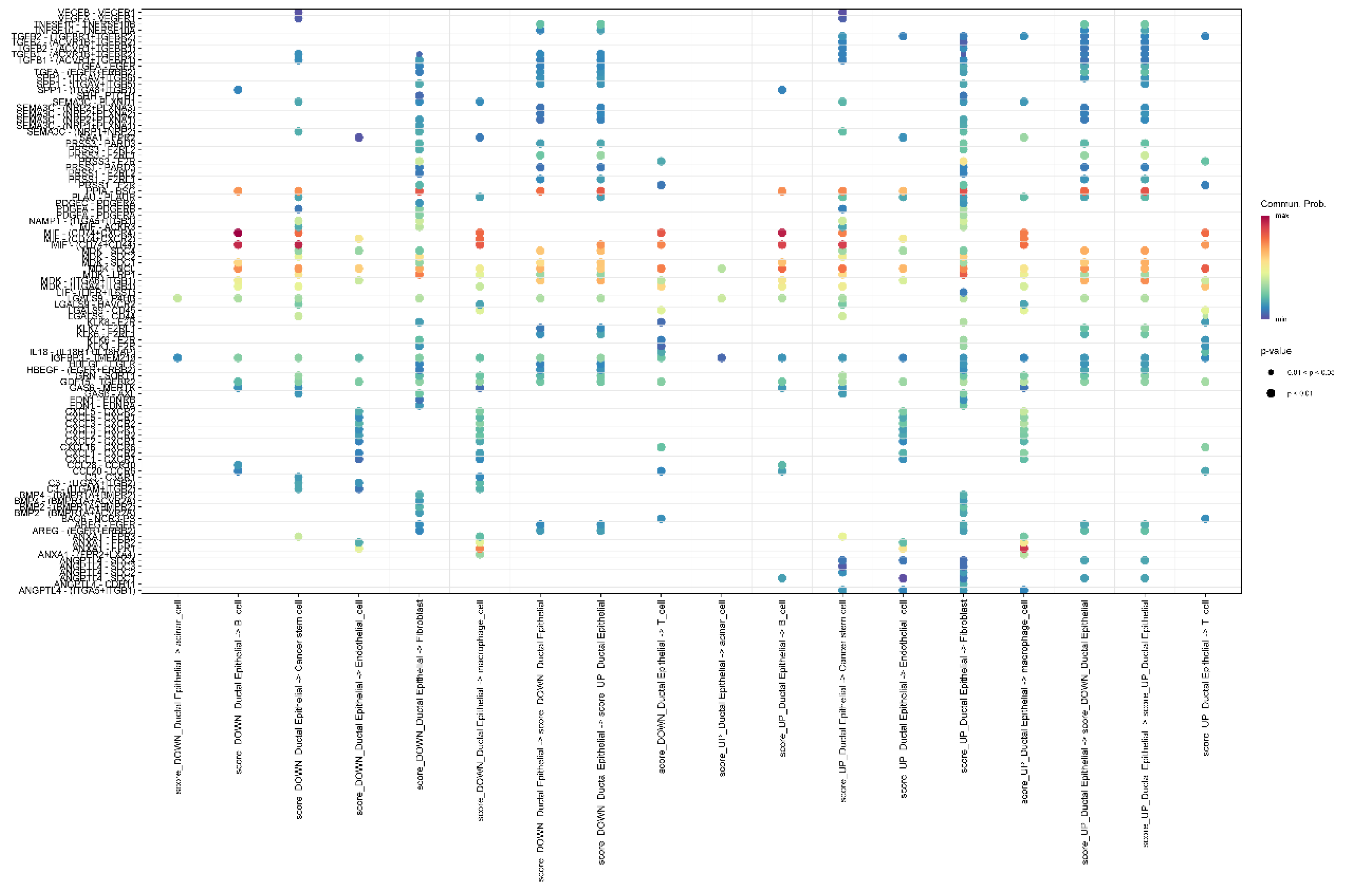

Our single-cell analysis revealed that CARGs-related genes are primarily expressed in ductal epithelial cells, with IFI27 and KLK10 exhibiting high expression in pancreatic ductal cells, and IFI27 also presenting high expression in fibroblasts. These findings suggest a strong association of these genes with malignant transformation and progression of ductal epithelial cells in pancreatic cancer. By contrast, these genes showed relatively low expression in immune cells (T cells, B cells, macrophages) and cancer stem cells, possibly reflecting the immunologically “cold tumor” property of pancreatic cancer [50], where immune cell activity is suppressed by a strong immunosuppressive microenvironment. Cell–cell communication analysis highlighted complex interactions between cell populations, particularly elevated crosstalk among high-scoring ductal epithelial cells, fibroblasts, and macrophages. Notably, the MIF signaling pathway was significantly implicated, suggesting a protumor function for fibroblasts—especially cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs)—and macrophages, as well as a pivotal role for MIF in modulating immune responses and promoting pancreatic tumor cell proliferation. Future work employing functional studies to validate these key signaling pathways and explore their therapeutic potential in PAAD is warranted.

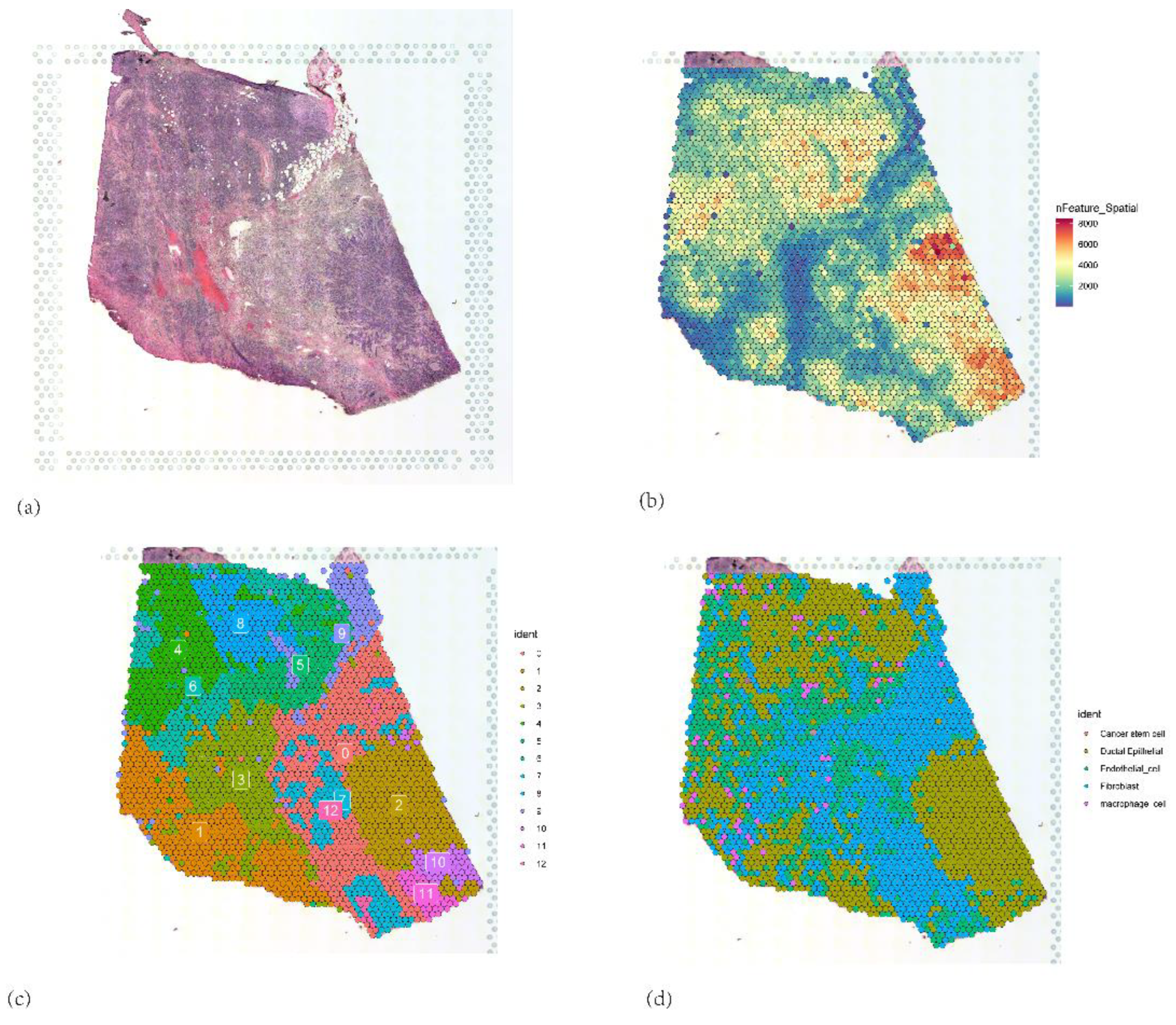

Further spatial transcriptomic analysis demonstrated that the expression of IFI27 aligns with single-cell annotation data, predominantly localized in ductal epithelial cells. Notably, IFI27 exhibited significantly elevated expression in the highly malignant Subcluster B (comprising ductal epithelial and neoplastic cell subpopulations), with its expression levels progressively increasing during tumor cell developmental stages, suggesting its potential involvement in late-stage regulation of malignant transformation. This finding reinforces its putative role in tumor epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) or invasive phenotypes. Pseudotime trajectory analysis revealed that KIF20A and TOP2A peaked in expression during mid-cell developmental phases, implicating their primary participation in tumor cell proliferation stages, particularly mitotic regulation, which is mechanistically linked to centrosome amplification processes. Spatial colocalization networks identified significant co-enrichment of endothelial niches with M2 tumor-associated macrophages (M2-TAMs) and cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), while CAFs coexisted with both M1 and M2 macrophages, potentially reflecting their synergistic contributions to immunosuppressive microenvironment formation and coupling of angiogenesis with invasive progression.

Overall, our study offers the first systematic analysis of centrosome amplification in PAAD. We uncovered an aberrant centrosome amplification–associated expression profile and demonstrated the oncogenic effects of centrosome amplification in PAAD. Moreover, we established a centrosome amplification–related predictive signature—IFI27, KIF20A, KLK10, SPINK7, and TOP2A—that shows high sensitivity and specificity in diagnosing and prognosticating PAAD patients. In addition, this CARG-based feature is closely tied to tumor aggressiveness, an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment, and chemotherapeutic responses. Collectively, a comprehensive evaluation of centrosome amplification–associated genes in PAAD advances our understanding of the disease’s mechanisms and paves the way for innovative therapeutic interventions.

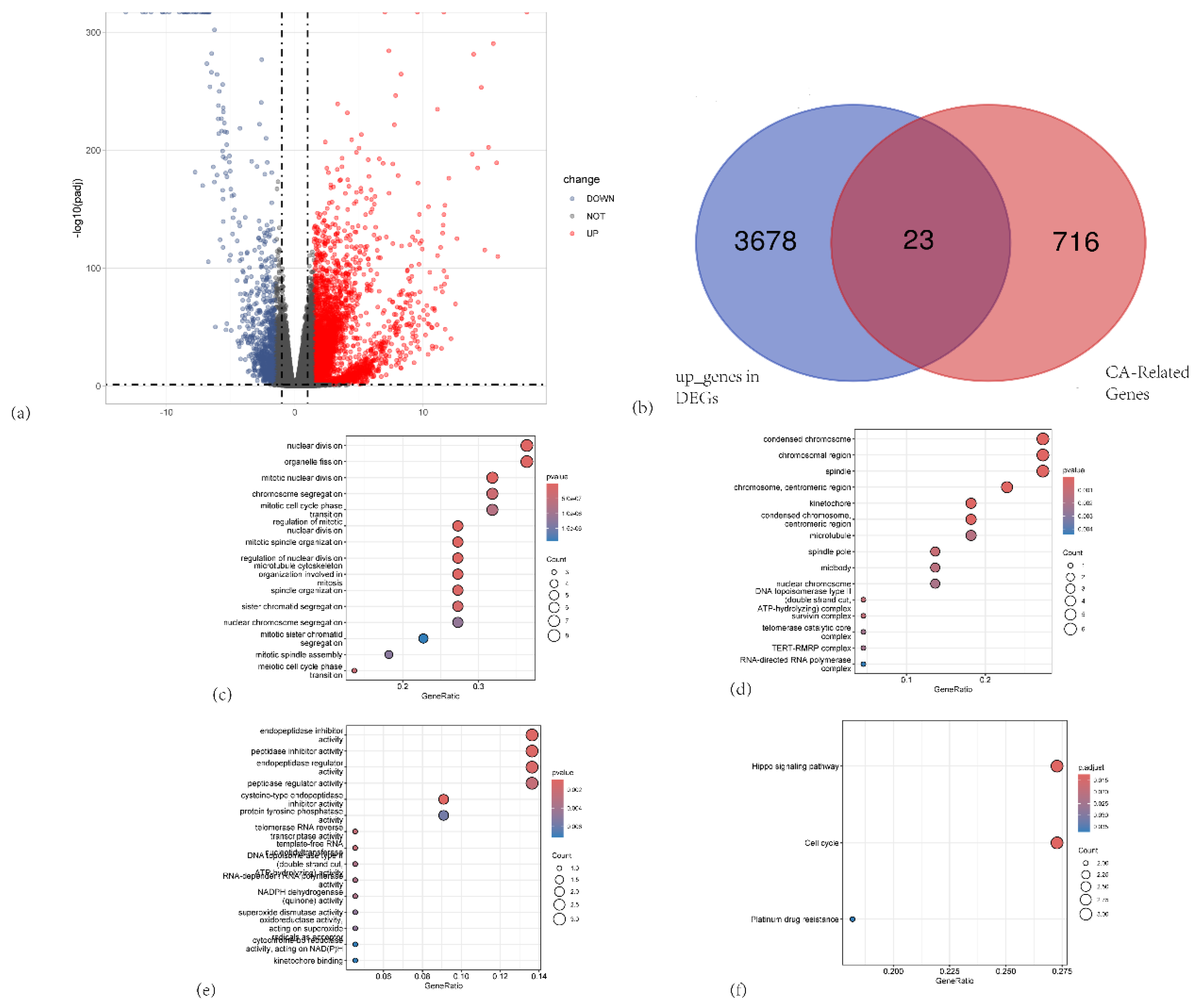

Figure 1.

(a) Volcano plot illustrating differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between PAAD tumor tissues and normal pancreatic tissues. (b)Venn diagram showing the intersection between upregulated DEGs (blue circle) and centrosome amplification–related genes (red circle) .(c–e) Bubble charts depicting Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analyses of the 23 overlapping genes. (c) Biological process (BP) terms; (d) Cellular component (CC) terms; and (e) Molecular function (MF) terms. (f) KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of the 23 overlapping genes.

Figure 1.

(a) Volcano plot illustrating differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between PAAD tumor tissues and normal pancreatic tissues. (b)Venn diagram showing the intersection between upregulated DEGs (blue circle) and centrosome amplification–related genes (red circle) .(c–e) Bubble charts depicting Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analyses of the 23 overlapping genes. (c) Biological process (BP) terms; (d) Cellular component (CC) terms; and (e) Molecular function (MF) terms. (f) KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of the 23 overlapping genes.

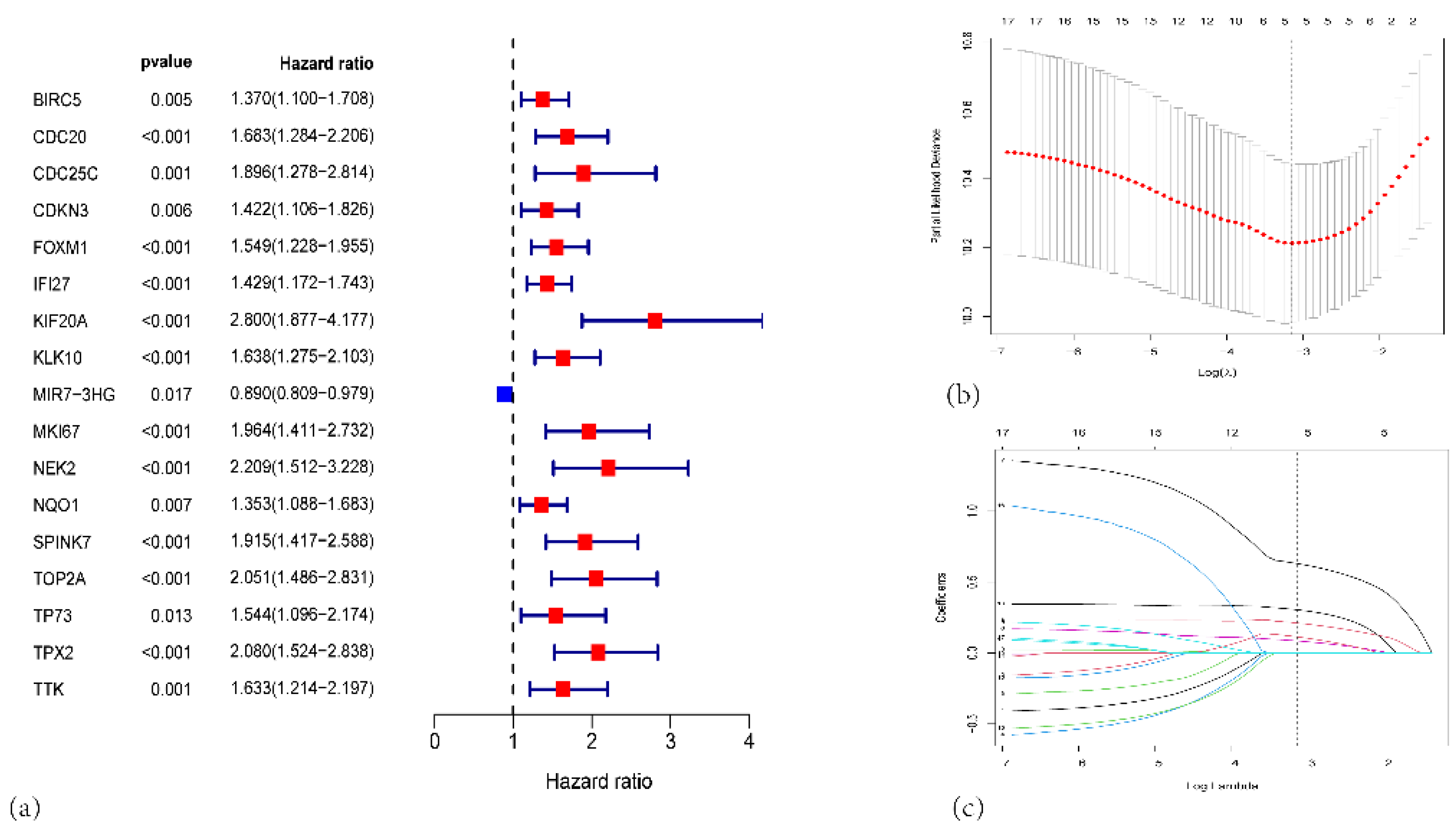

Figure 2.

(a) Forest plot from univariate Cox proportional hazards analysis of the centrosome amplification–related genes in PAAD. (b) LASSO regression model selection using 10-fold cross-validation. (c) Coefficient profiles of the survival-associated genes as a function of log(λ).

Figure 2.

(a) Forest plot from univariate Cox proportional hazards analysis of the centrosome amplification–related genes in PAAD. (b) LASSO regression model selection using 10-fold cross-validation. (c) Coefficient profiles of the survival-associated genes as a function of log(λ).

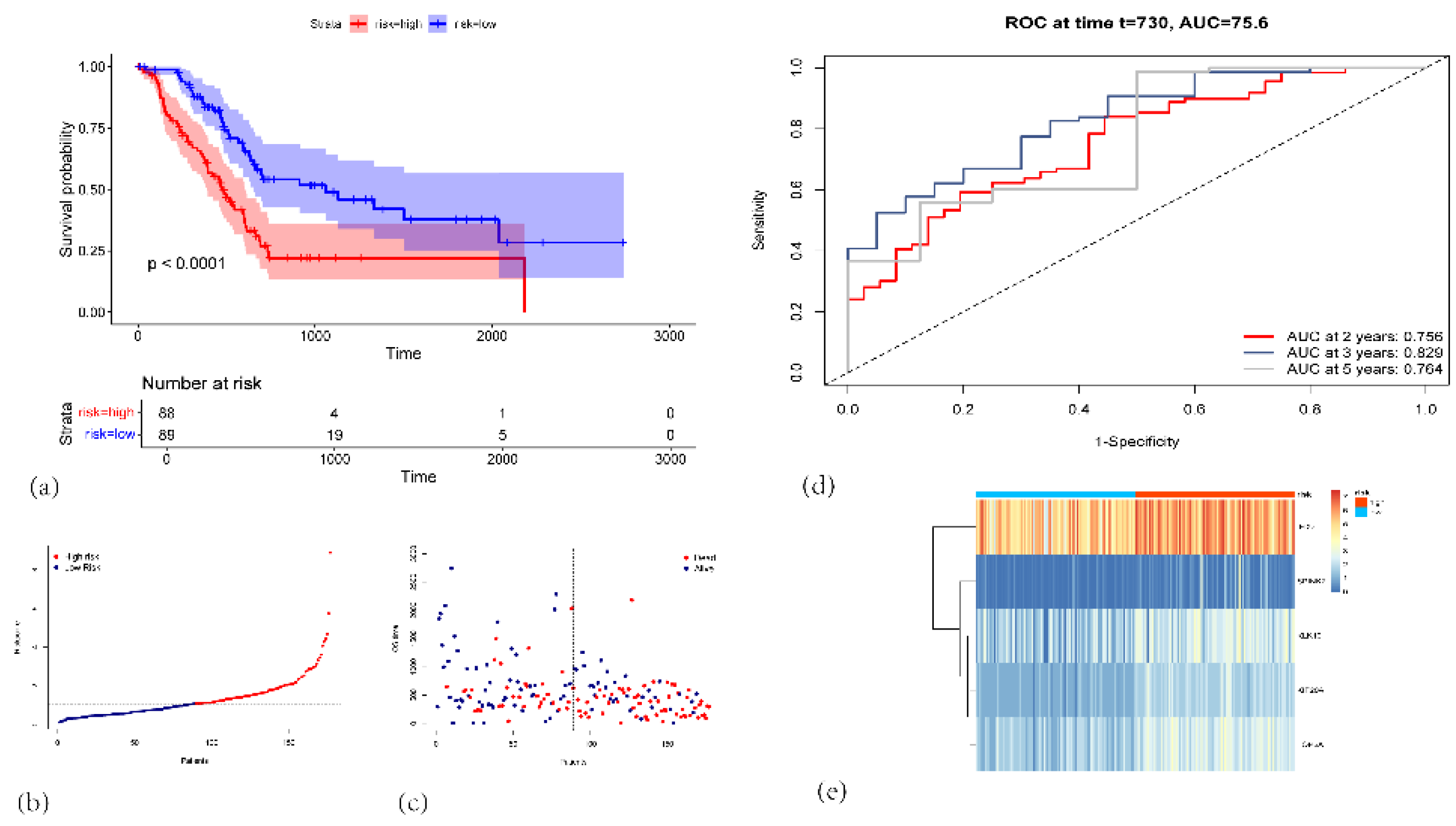

Figure 3.

(a) Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the high-risk (red, n=88) and low-risk (blue, n=89) groups in the TCGA-PAAD cohort. (b) Risk score distribution plot. Each dot represents an individual patient. (c) Scatter plot showing each patient’s survival status (alive or dead) and OS time. (d) Time-dependent ROC curves for 2-, 3-, and 5-year OS prediction. (e) Heatmap illustrating the expression patterns of the five signature genes (IFI27, SPINK7, KLK10, KIF20A, and TOP2A) in high-risk (red) and low-risk (blue) patients.

Figure 3.

(a) Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the high-risk (red, n=88) and low-risk (blue, n=89) groups in the TCGA-PAAD cohort. (b) Risk score distribution plot. Each dot represents an individual patient. (c) Scatter plot showing each patient’s survival status (alive or dead) and OS time. (d) Time-dependent ROC curves for 2-, 3-, and 5-year OS prediction. (e) Heatmap illustrating the expression patterns of the five signature genes (IFI27, SPINK7, KLK10, KIF20A, and TOP2A) in high-risk (red) and low-risk (blue) patients.

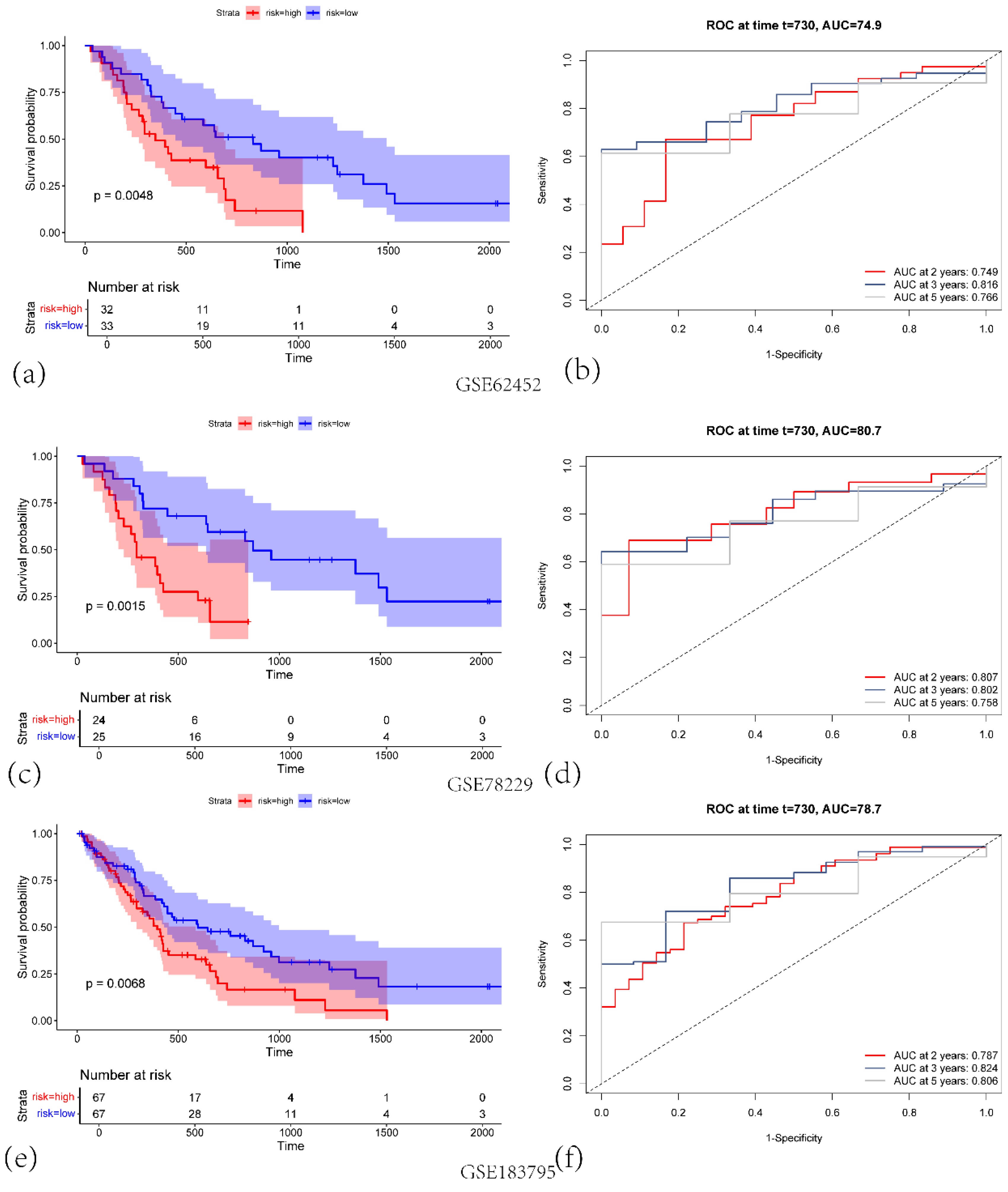

Figure 4.

(a) KM survival curves for the high-risk (red) and low-risk (blue) groups in GSE62452 validation cohort. (b)Corresponding ROC curves for predicting 2-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival (OS), with the respective AUC values indicated in GSE62452 validation cohort. (c)KM survival curves for high-risk versus low-risk groups in GSE78229 validation cohort. (d) Time-dependent ROC curves at 2, 3, and 5 years, illustrating the predictive performance of the signature in GSE78229 validation cohort. (e) KM survival curves showing significant differences in OS between high-risk and low-risk groups in GSE183795 validation cohort. (f) ROC curves demonstrating the model’s performance at 2, 3, and 5 years in GSE183795 validation cohort.

Figure 4.

(a) KM survival curves for the high-risk (red) and low-risk (blue) groups in GSE62452 validation cohort. (b)Corresponding ROC curves for predicting 2-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival (OS), with the respective AUC values indicated in GSE62452 validation cohort. (c)KM survival curves for high-risk versus low-risk groups in GSE78229 validation cohort. (d) Time-dependent ROC curves at 2, 3, and 5 years, illustrating the predictive performance of the signature in GSE78229 validation cohort. (e) KM survival curves showing significant differences in OS between high-risk and low-risk groups in GSE183795 validation cohort. (f) ROC curves demonstrating the model’s performance at 2, 3, and 5 years in GSE183795 validation cohort.

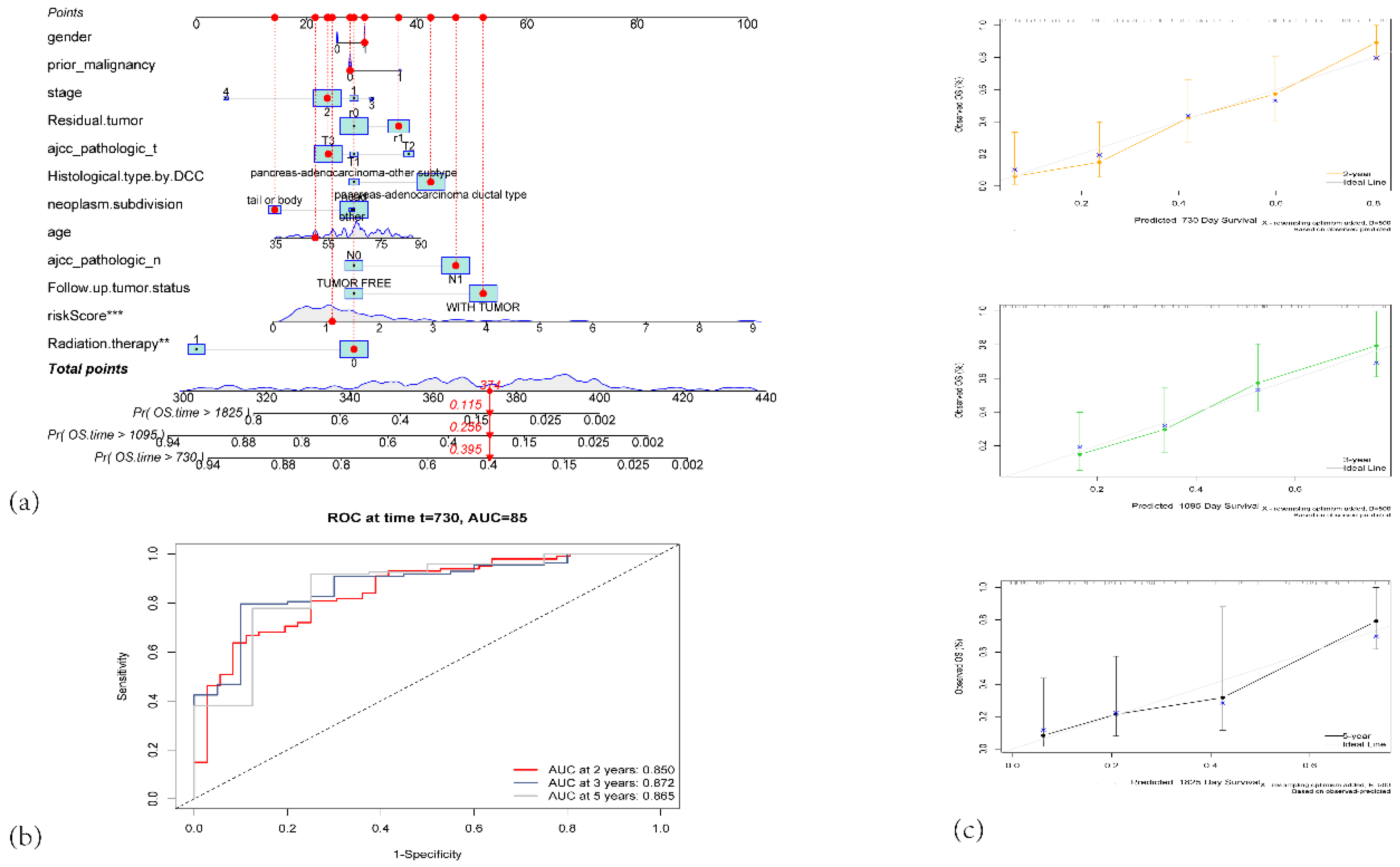

Figure 5.

(a) Nomogram for predicting 2-year, 3-year, and 5-year overall survival (OS) in PAAD patients. (b)Time-dependent ROC curves of the nomogram for predicting 2-year, 3-year, and 5-year survival. (c) Calibration plots for predicted survival at 2 years (orange), 3 years (green), and 5 years (black).

Figure 5.

(a) Nomogram for predicting 2-year, 3-year, and 5-year overall survival (OS) in PAAD patients. (b)Time-dependent ROC curves of the nomogram for predicting 2-year, 3-year, and 5-year survival. (c) Calibration plots for predicted survival at 2 years (orange), 3 years (green), and 5 years (black).

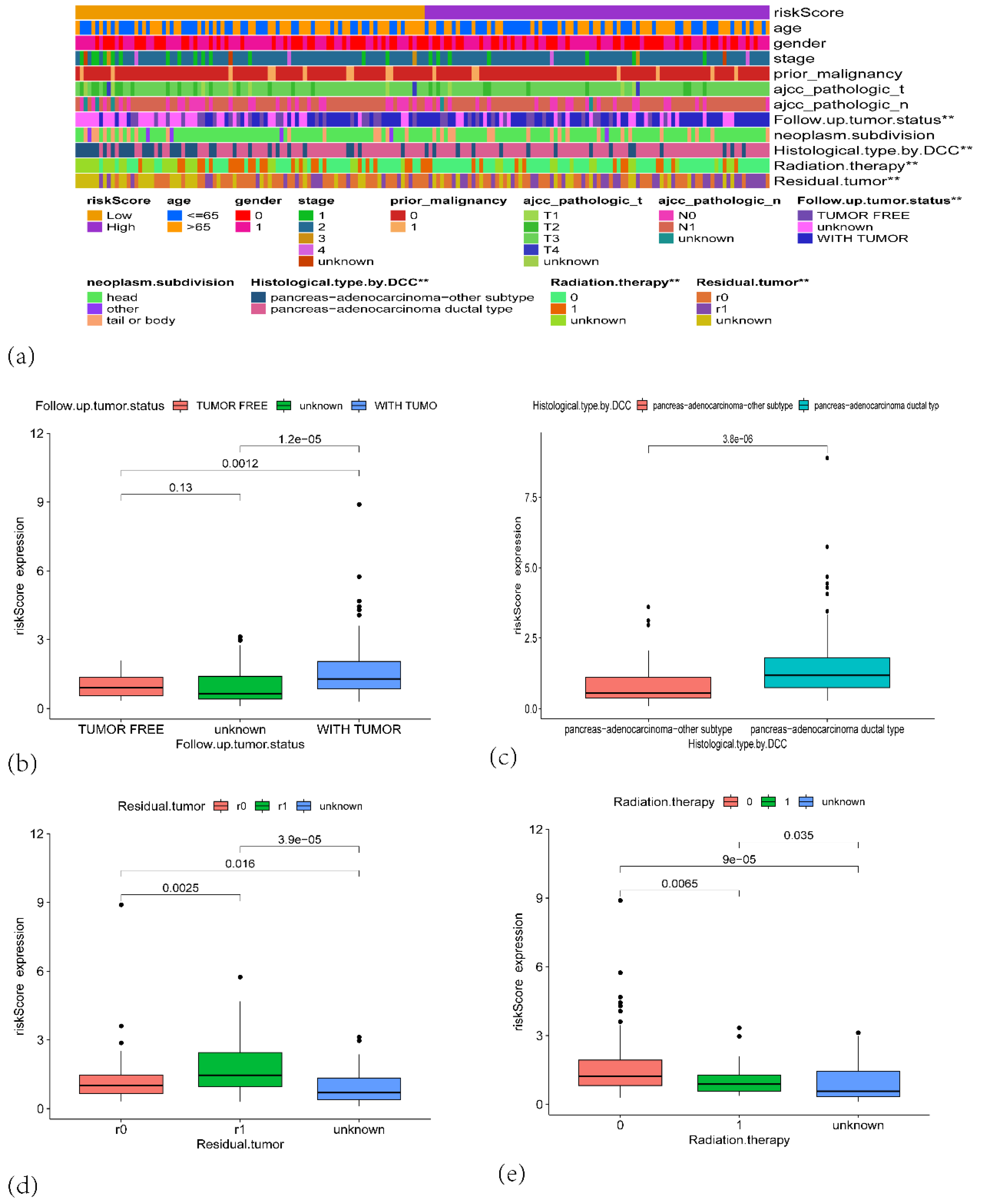

Figure 6.

(a) A heatmap showing the distribution of clinical features and risk scores across high-risk and low-risk groups. (b) Boxplot showing the risk score expression distribution based on the follow-up tumor status. (c) Boxplot comparing the risk score expression based on histological type by DCC. (d) Boxplot of risk score expression based on residual tumor status. (e) Boxplot of risk score expression based on radiation therapy status.

Figure 6.

(a) A heatmap showing the distribution of clinical features and risk scores across high-risk and low-risk groups. (b) Boxplot showing the risk score expression distribution based on the follow-up tumor status. (c) Boxplot comparing the risk score expression based on histological type by DCC. (d) Boxplot of risk score expression based on residual tumor status. (e) Boxplot of risk score expression based on radiation therapy status.

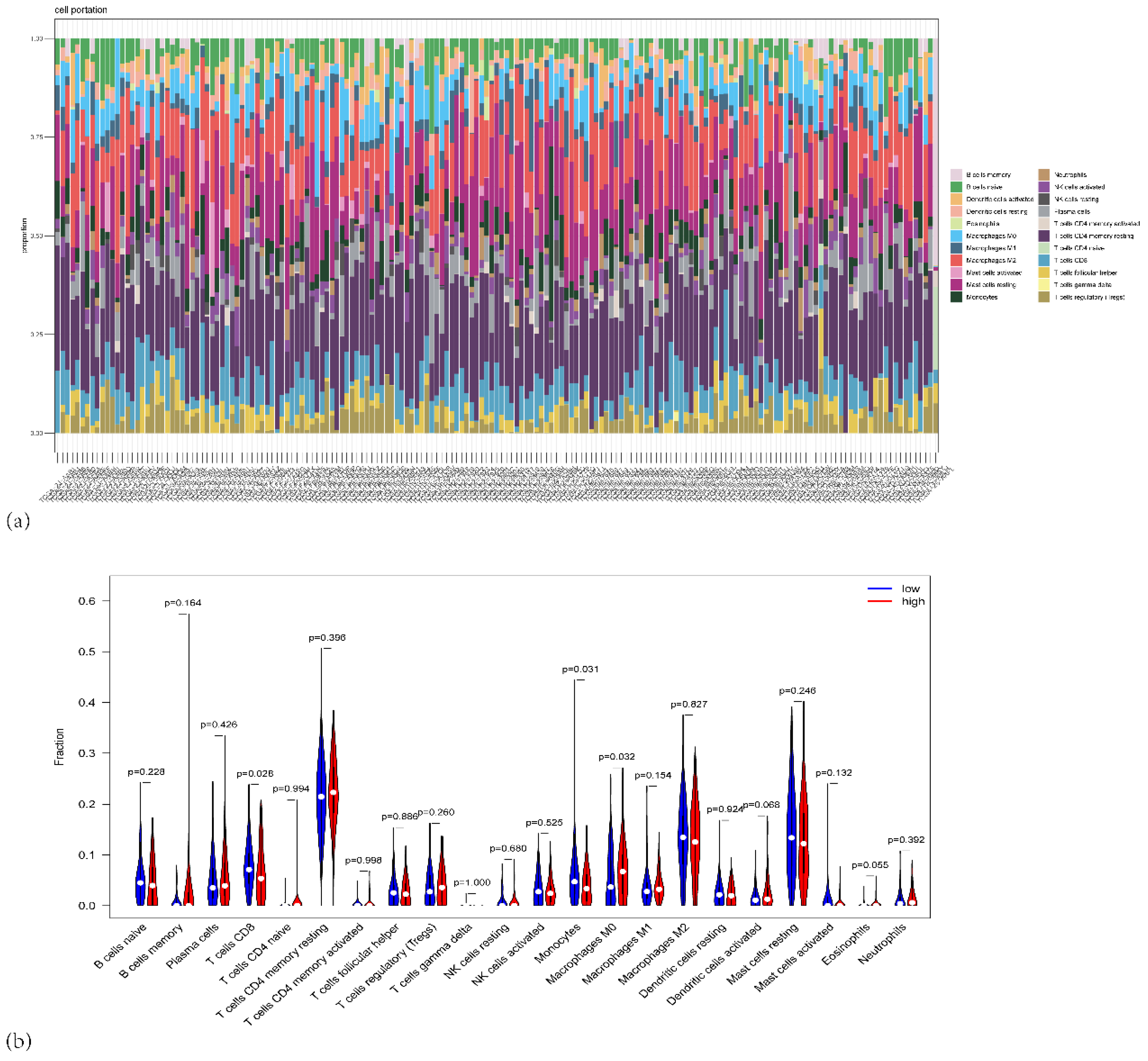

Figure 7.

(a) Stacked bar plot showing the proportion of different immune cell types across the PAAD patients in TCGA. (b) Violin plots depicting the distribution of immune cell fractions across high-risk (red) and low-risk (blue) groups.

Figure 7.

(a) Stacked bar plot showing the proportion of different immune cell types across the PAAD patients in TCGA. (b) Violin plots depicting the distribution of immune cell fractions across high-risk (red) and low-risk (blue) groups.

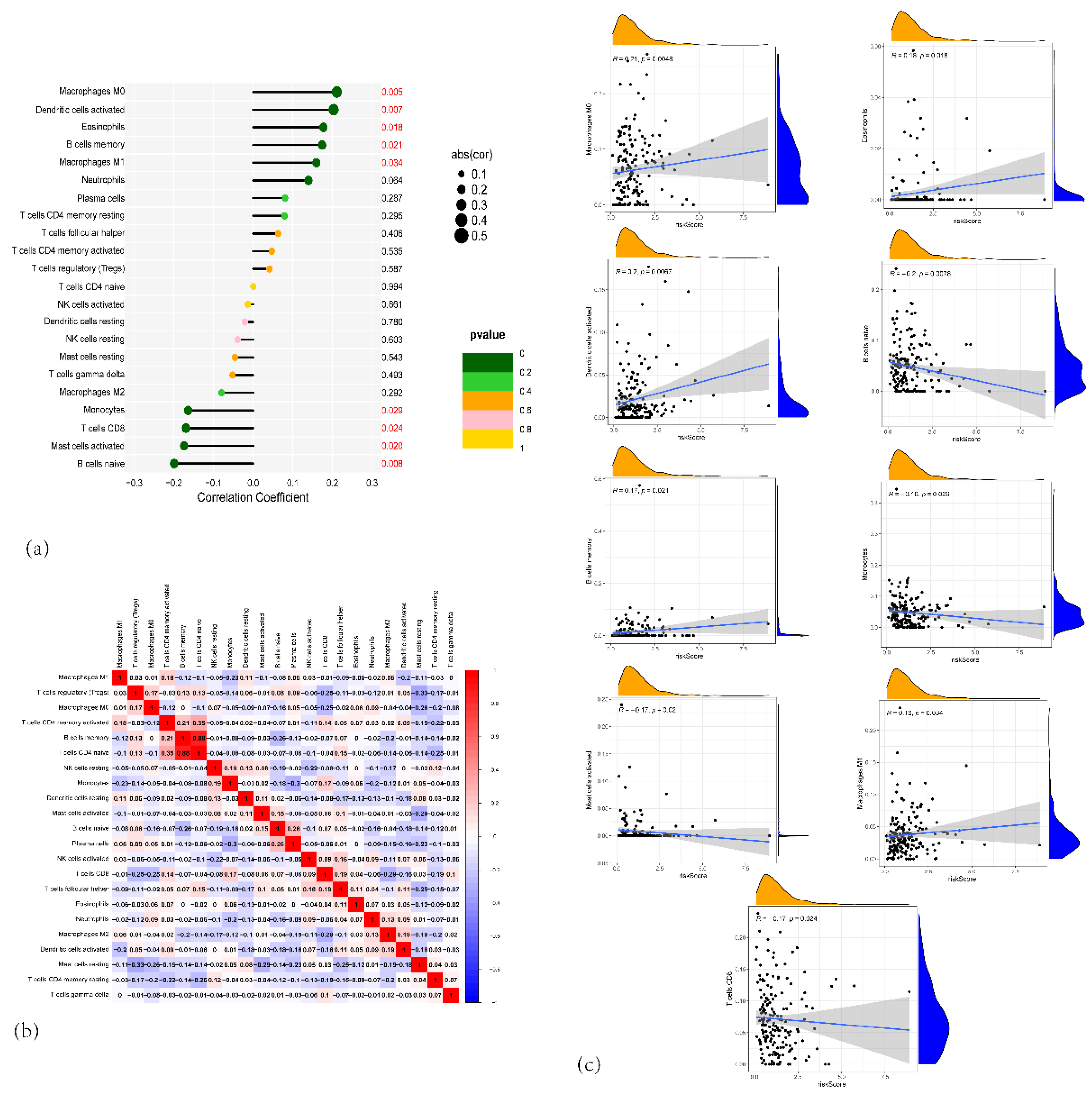

Figure 8.

(a) Forest plot of the correlation between the proportion of different immune cells and risk scores. (b) Heatmap showing the correlation matrix between the different immune cell fractions. (c) Scatter plots showing the relationship between risk scores and specific immune cell types.

Figure 8.

(a) Forest plot of the correlation between the proportion of different immune cells and risk scores. (b) Heatmap showing the correlation matrix between the different immune cell fractions. (c) Scatter plots showing the relationship between risk scores and specific immune cell types.

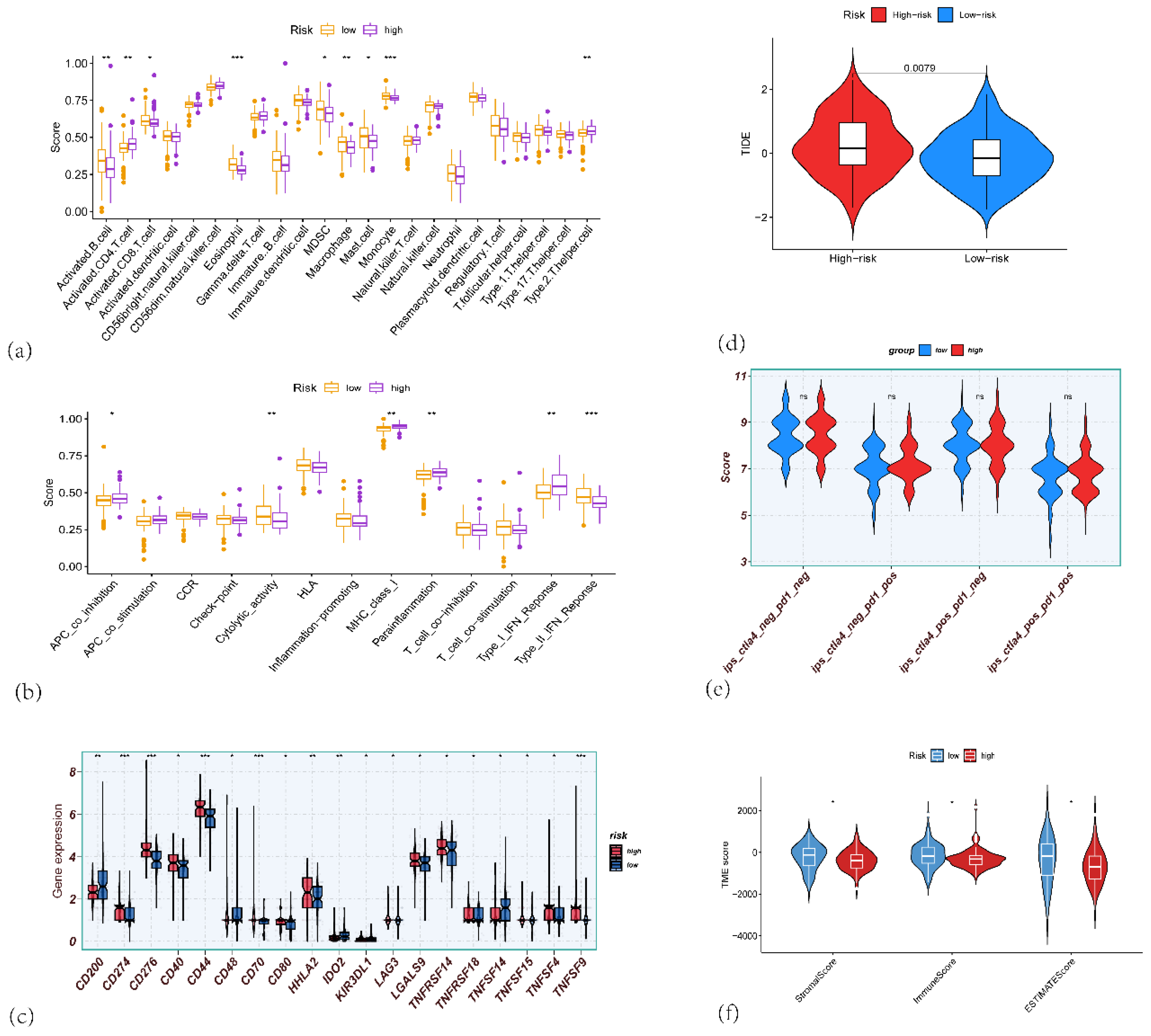

Figure 9.

(a) Box plots showing the immune scores for various immune cells across high-risk and low-risk groups in PAAD. (b) Box plots showing the differences in immune-related function between the high-risk and low-risk groups. (c) Box plots showing the gene expression of immune checkpoint genes such as CD201, CD276, CD70, HLA, and others, comparing high-risk and low-risk PAAD patients. (d) Violin plots showing the TIDE scores between high-risk (red) and low-risk (blue) groups, indicating the potential of immune evasion in the two risk groups. (e) Violin plots comparing the IPS (Immune-related Pathway Signature) scores between high-risk and low-risk PAAD patients, (f) Violin plots showing the differences in ImmuneScore, StromalScore, and ESTIMATEScore, calculated by the ESTIMATE algorithm, comparing high-risk and low-risk PAAD patients.

Figure 9.

(a) Box plots showing the immune scores for various immune cells across high-risk and low-risk groups in PAAD. (b) Box plots showing the differences in immune-related function between the high-risk and low-risk groups. (c) Box plots showing the gene expression of immune checkpoint genes such as CD201, CD276, CD70, HLA, and others, comparing high-risk and low-risk PAAD patients. (d) Violin plots showing the TIDE scores between high-risk (red) and low-risk (blue) groups, indicating the potential of immune evasion in the two risk groups. (e) Violin plots comparing the IPS (Immune-related Pathway Signature) scores between high-risk and low-risk PAAD patients, (f) Violin plots showing the differences in ImmuneScore, StromalScore, and ESTIMATEScore, calculated by the ESTIMATE algorithm, comparing high-risk and low-risk PAAD patients.

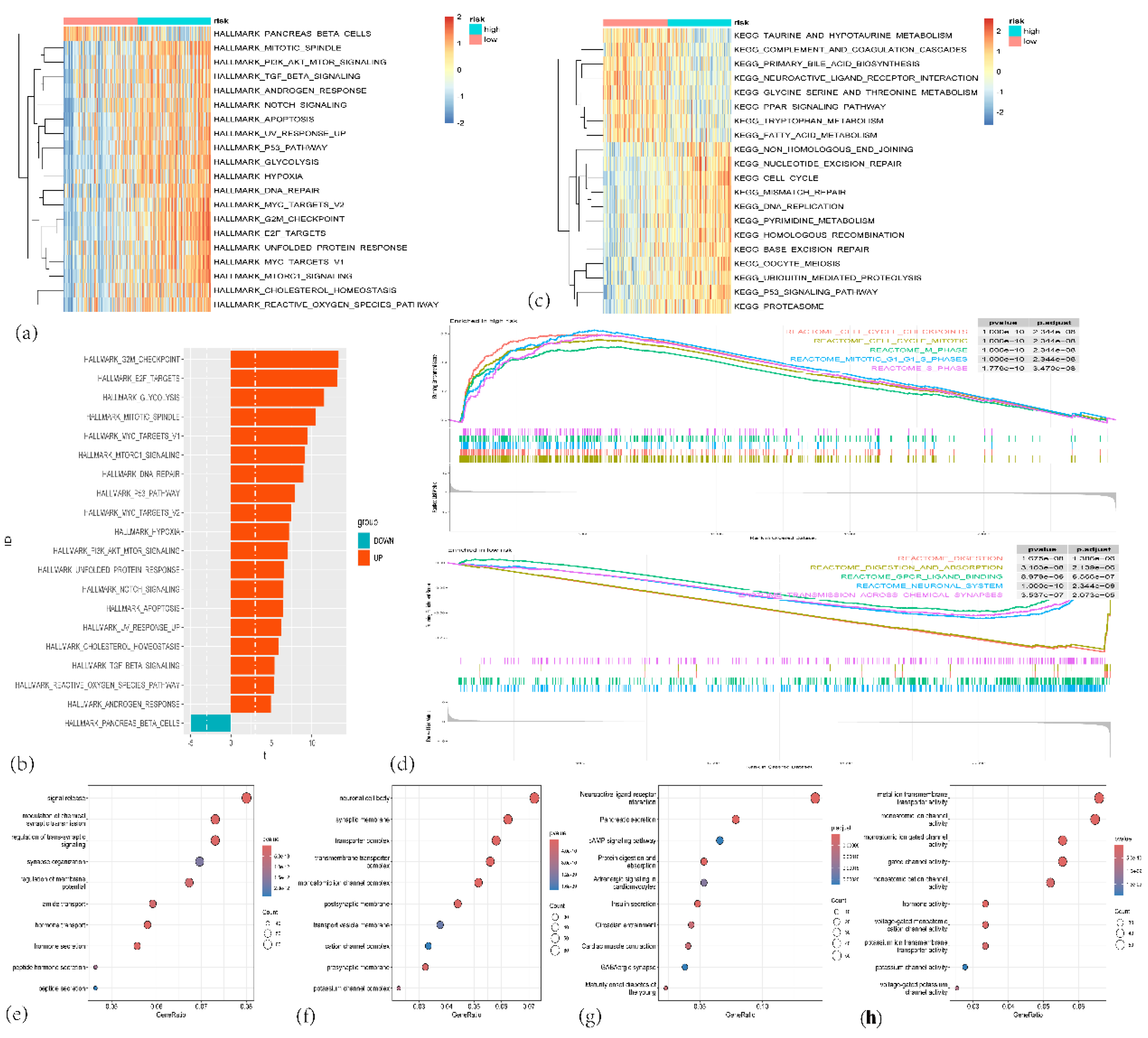

Figure 10.

(a) Heatmap showing the enrichment of hallmark gene sets between high-risk and low-risk groups. (b) Bar plot depicting the number of differentially expressed hallmark gene sets between high-risk and low-risk groups. (c) Heatmap showing the enrichment of KEGG gene sets in high-risk and low-risk groups. (d)The important pathway of Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) plot comparing the high-risk and low-risk groups. (e–g) Bubble charts depicting Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analyses of different genes in high-risk and low-risk groups. (c) Biological process (BP) terms; (d) Cellular component (CC) terms; and (e) Molecular function (MF) terms. (h) KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of different genes in high-risk and low-risk groups.

Figure 10.

(a) Heatmap showing the enrichment of hallmark gene sets between high-risk and low-risk groups. (b) Bar plot depicting the number of differentially expressed hallmark gene sets between high-risk and low-risk groups. (c) Heatmap showing the enrichment of KEGG gene sets in high-risk and low-risk groups. (d)The important pathway of Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) plot comparing the high-risk and low-risk groups. (e–g) Bubble charts depicting Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analyses of different genes in high-risk and low-risk groups. (c) Biological process (BP) terms; (d) Cellular component (CC) terms; and (e) Molecular function (MF) terms. (h) KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of different genes in high-risk and low-risk groups.

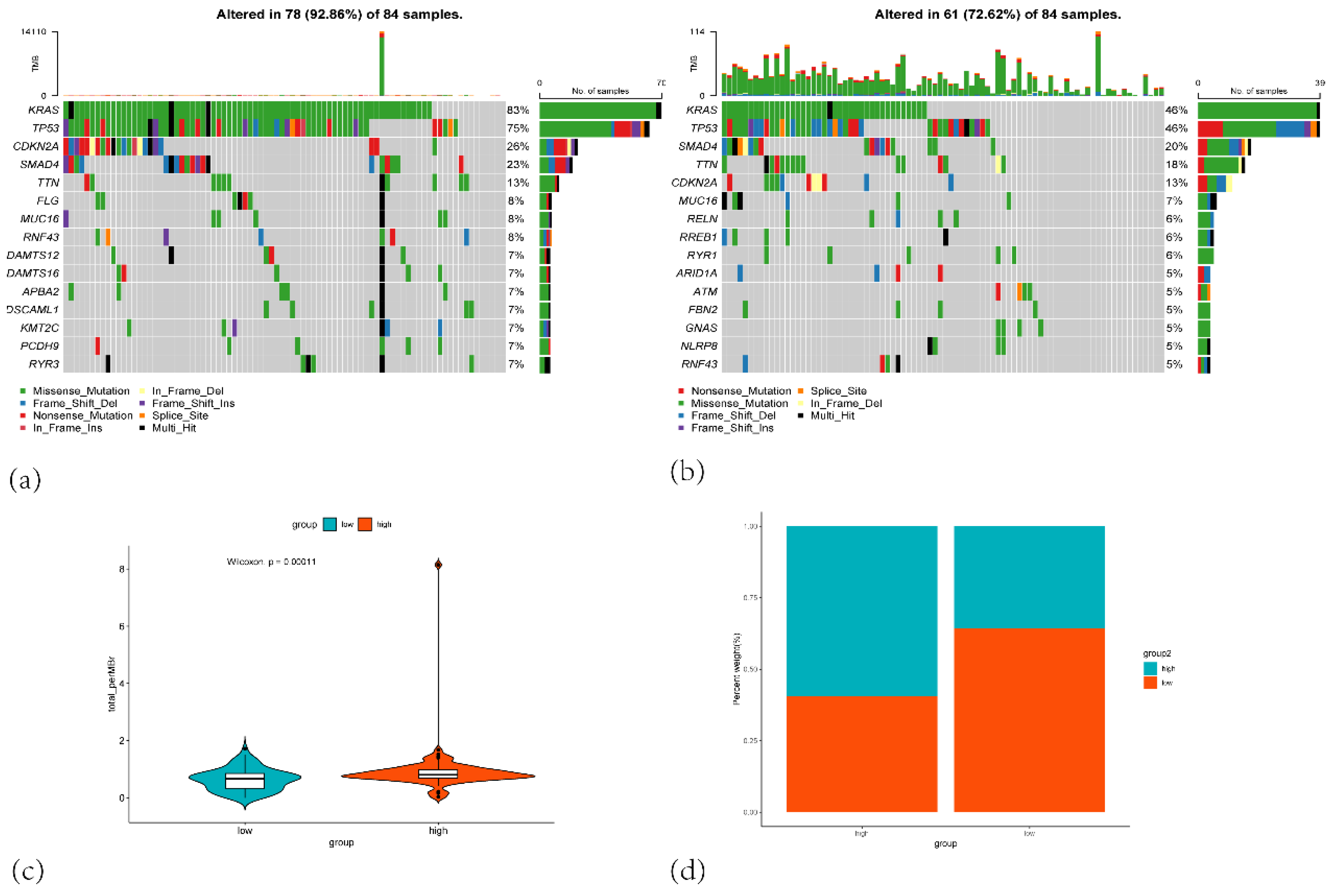

Figure 11.

(a) Oncoprint of mutations in the top 10 most frequently altered genes in the high-risk group. (b) Oncoprint of mutations in the top 10 most frequently altered genes in the low-risk group. (c) Violin plot comparing the total number of mutations (total mutation count per megabase) between the low-risk (blue) and high-risk (orange) groups. (d) Stacked bar plot showing the percentage distribution of patients in the high-risk and low-risk groups based on mutation burden.

Figure 11.

(a) Oncoprint of mutations in the top 10 most frequently altered genes in the high-risk group. (b) Oncoprint of mutations in the top 10 most frequently altered genes in the low-risk group. (c) Violin plot comparing the total number of mutations (total mutation count per megabase) between the low-risk (blue) and high-risk (orange) groups. (d) Stacked bar plot showing the percentage distribution of patients in the high-risk and low-risk groups based on mutation burden.

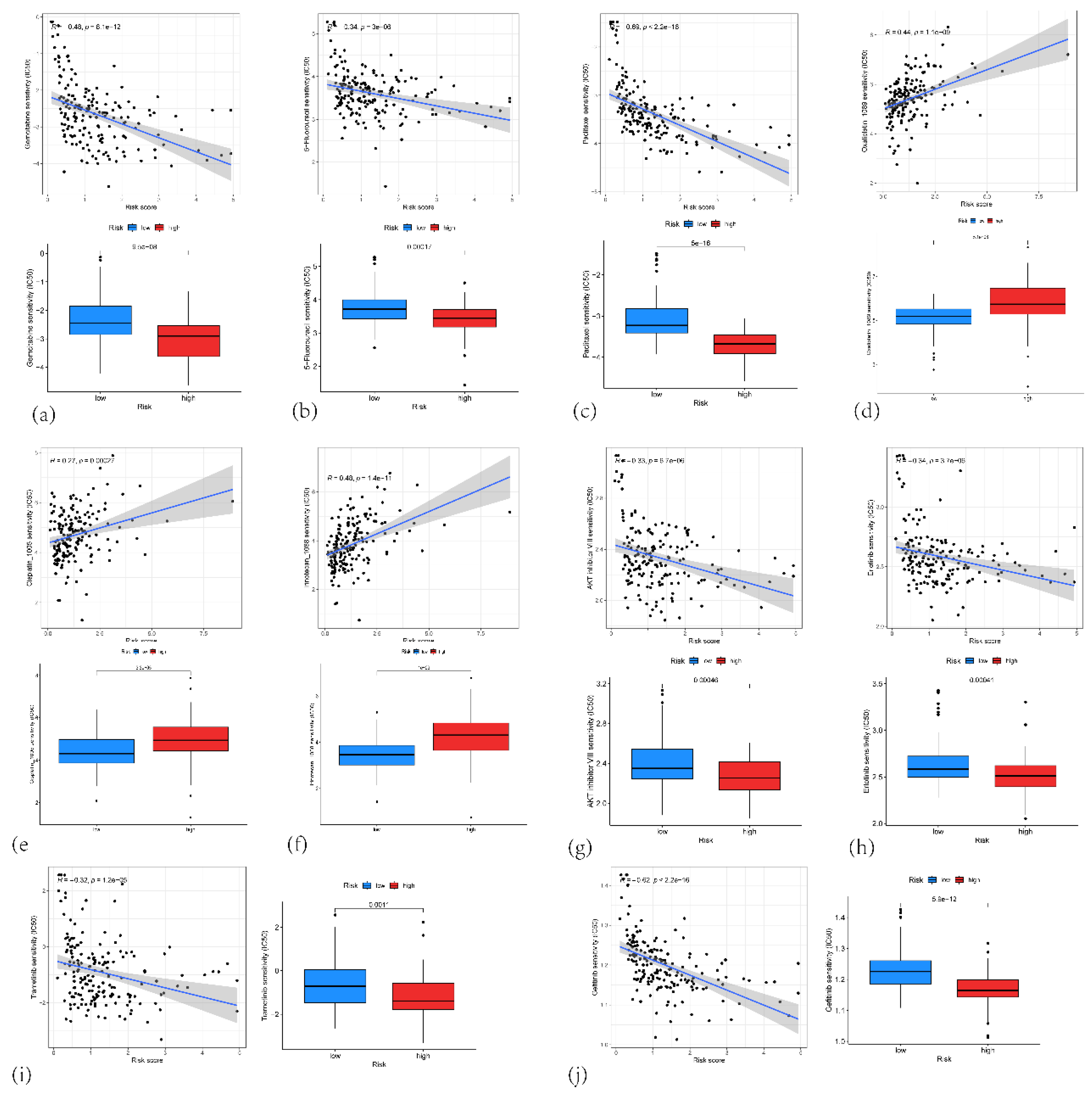

Figure 12.

(a) Correlation plot showing the correlation between the risk score and the IC50 of Gemcitabine and Boxplots of the estimated IC50 of Gemcitabine in the high-risk and low-risk group. (b) Correlation plot showing the correlation between the risk score and the IC50 of 5-fluorouracil and Boxplots of the estimated IC50 of 5-fluorouracil in the high-risk and low-risk group. (c) Correlation plot showing the correlation between the risk score and the IC50 of paclitaxel and Boxplots of the estimated IC50 of paclitaxel in the high-risk and low-risk group. (d) Correlation plot showing the correlation between the risk score and the IC50 of oxaliplatin and Boxplots of the estimated IC50 of oxaliplatin in the high-risk and low-risk group. (e) Correlation plot showing the correlation between the risk score and the IC50 of cisplatin and Boxplots of the estimated IC50 of cisplatin in the high-risk and low-risk group. (f) Correlation plot showing the correlation between the risk score and the IC50 of irinotecan and Boxplots of the estimated IC50 of irinotecan in the high-risk and low-risk group. (g) Correlation plot showing the correlation between the risk score and the IC50 of AKT inhibitor VIII and Boxplots of the estimated IC50 of AKT inhibitor VIII in the high-risk and low-risk group. (h) Correlation plot showing the correlation between the risk score and the IC50 of erlotinib and Boxplots of the estimated IC50 of erlotinib in the high-risk and low-risk group. (i) Correlation plot showing the correlation between the risk score and the IC50 of trametinib and Boxplots of the estimated IC50 of trametinib in the high-risk and low-risk group. (j) Correlation plot showing the correlation between the risk score and the IC50 of gefitinib and Boxplots of the estimated IC50 of gefitinib in the high-risk and low-risk group.

Figure 12.

(a) Correlation plot showing the correlation between the risk score and the IC50 of Gemcitabine and Boxplots of the estimated IC50 of Gemcitabine in the high-risk and low-risk group. (b) Correlation plot showing the correlation between the risk score and the IC50 of 5-fluorouracil and Boxplots of the estimated IC50 of 5-fluorouracil in the high-risk and low-risk group. (c) Correlation plot showing the correlation between the risk score and the IC50 of paclitaxel and Boxplots of the estimated IC50 of paclitaxel in the high-risk and low-risk group. (d) Correlation plot showing the correlation between the risk score and the IC50 of oxaliplatin and Boxplots of the estimated IC50 of oxaliplatin in the high-risk and low-risk group. (e) Correlation plot showing the correlation between the risk score and the IC50 of cisplatin and Boxplots of the estimated IC50 of cisplatin in the high-risk and low-risk group. (f) Correlation plot showing the correlation between the risk score and the IC50 of irinotecan and Boxplots of the estimated IC50 of irinotecan in the high-risk and low-risk group. (g) Correlation plot showing the correlation between the risk score and the IC50 of AKT inhibitor VIII and Boxplots of the estimated IC50 of AKT inhibitor VIII in the high-risk and low-risk group. (h) Correlation plot showing the correlation between the risk score and the IC50 of erlotinib and Boxplots of the estimated IC50 of erlotinib in the high-risk and low-risk group. (i) Correlation plot showing the correlation between the risk score and the IC50 of trametinib and Boxplots of the estimated IC50 of trametinib in the high-risk and low-risk group. (j) Correlation plot showing the correlation between the risk score and the IC50 of gefitinib and Boxplots of the estimated IC50 of gefitinib in the high-risk and low-risk group.

Figure 13.

(a) t-SNE plot showing the clustering of single-cell RNA sequencing data from PAAD samples. (b) t-SNE plot showing the clustering of single-cell RNA sequencing data with Cell type annotations (c) t-SNE plot highlighting the expression of IFI27, KLK10, TOP2A, SPINK7 and KIF20A in the single cells. (d) Violin plot showing the expression of 5 genes in various cell types.

Figure 13.

(a) t-SNE plot showing the clustering of single-cell RNA sequencing data from PAAD samples. (b) t-SNE plot showing the clustering of single-cell RNA sequencing data with Cell type annotations (c) t-SNE plot highlighting the expression of IFI27, KLK10, TOP2A, SPINK7 and KIF20A in the single cells. (d) Violin plot showing the expression of 5 genes in various cell types.

Figure 14.

(a) A network graph showing the number of interactions between different cell types in the tumor microenvironment. (b) A hierarchical layout diagram of the MIF (Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor) signaling pathway network. (c) A network diagram of the MIF (Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor) signaling pathway network.(d) A heatmap displaying outgoing signaling patterns from the different cell types. (e) A heatmap displaying incoming signaling patterns to the different cell types.

Figure 14.

(a) A network graph showing the number of interactions between different cell types in the tumor microenvironment. (b) A hierarchical layout diagram of the MIF (Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor) signaling pathway network. (c) A network diagram of the MIF (Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor) signaling pathway network.(d) A heatmap displaying outgoing signaling patterns from the different cell types. (e) A heatmap displaying incoming signaling patterns to the different cell types.

Figure 15.

A heatmap showing the interaction probabilities between different signaling pathways and cell to cell relationship.

Figure 15.

A heatmap showing the interaction probabilities between different signaling pathways and cell to cell relationship.

Figure 16.

(a) Pancreatic tumor tissue section (b) Spatial distribution patterns of UMIs and gene counts on the tissue section (c) UMAP dimensionality reduction plot showing the clustering of ST from PAAD tissue (d) Cell type annotation of the tissue section by RCTD deconvolution algorithm.

Figure 16.

(a) Pancreatic tumor tissue section (b) Spatial distribution patterns of UMIs and gene counts on the tissue section (c) UMAP dimensionality reduction plot showing the clustering of ST from PAAD tissue (d) Cell type annotation of the tissue section by RCTD deconvolution algorithm.

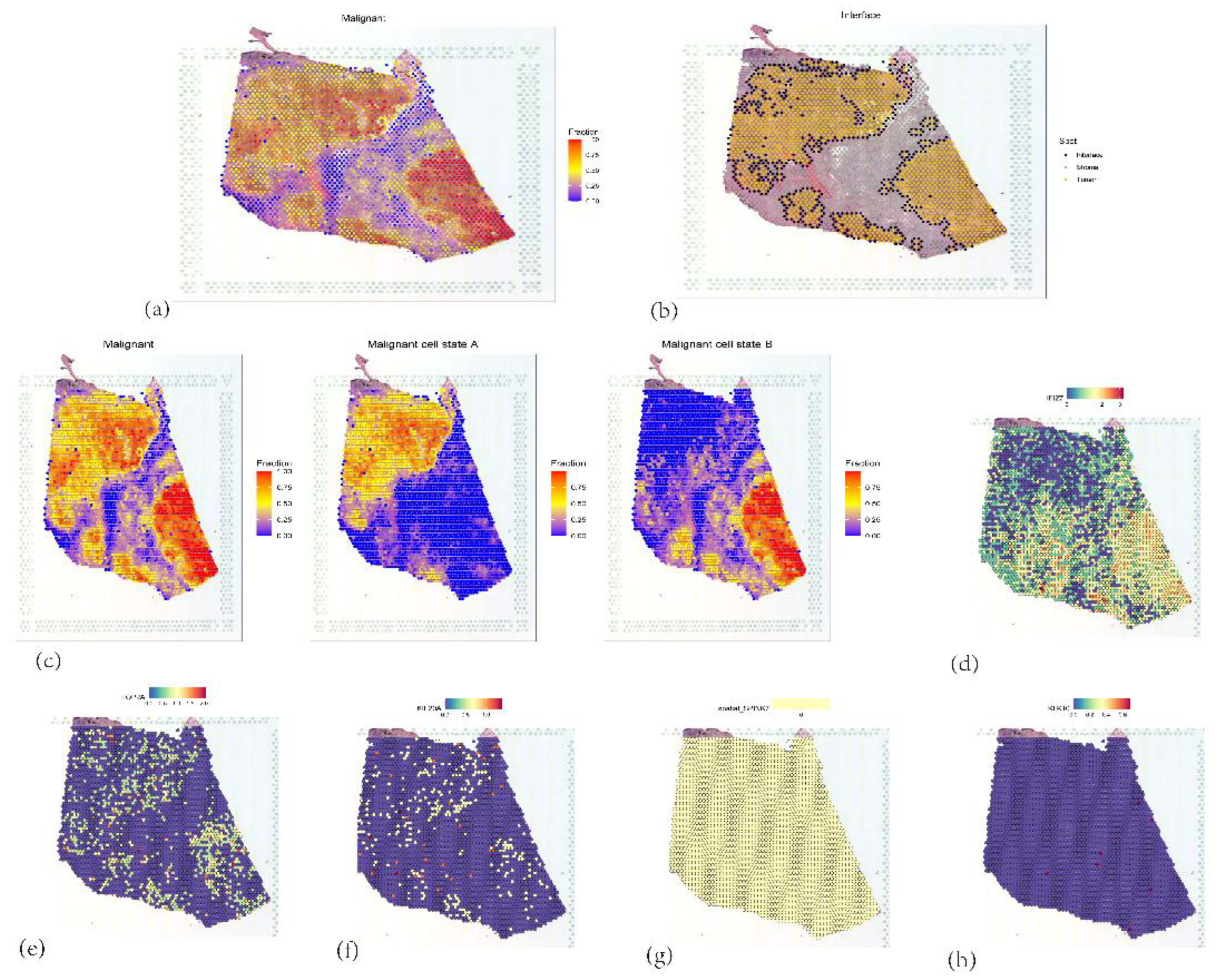

Figure 17.

(a) Identification and distribution of malignant tumor cells. (b) Interface of malignant tumor cells (c) Staging of malignant tumor cells. (d, e, f, g, h) Expression of 5 core genes.

Figure 17.

(a) Identification and distribution of malignant tumor cells. (b) Interface of malignant tumor cells (c) Staging of malignant tumor cells. (d, e, f, g, h) Expression of 5 core genes.

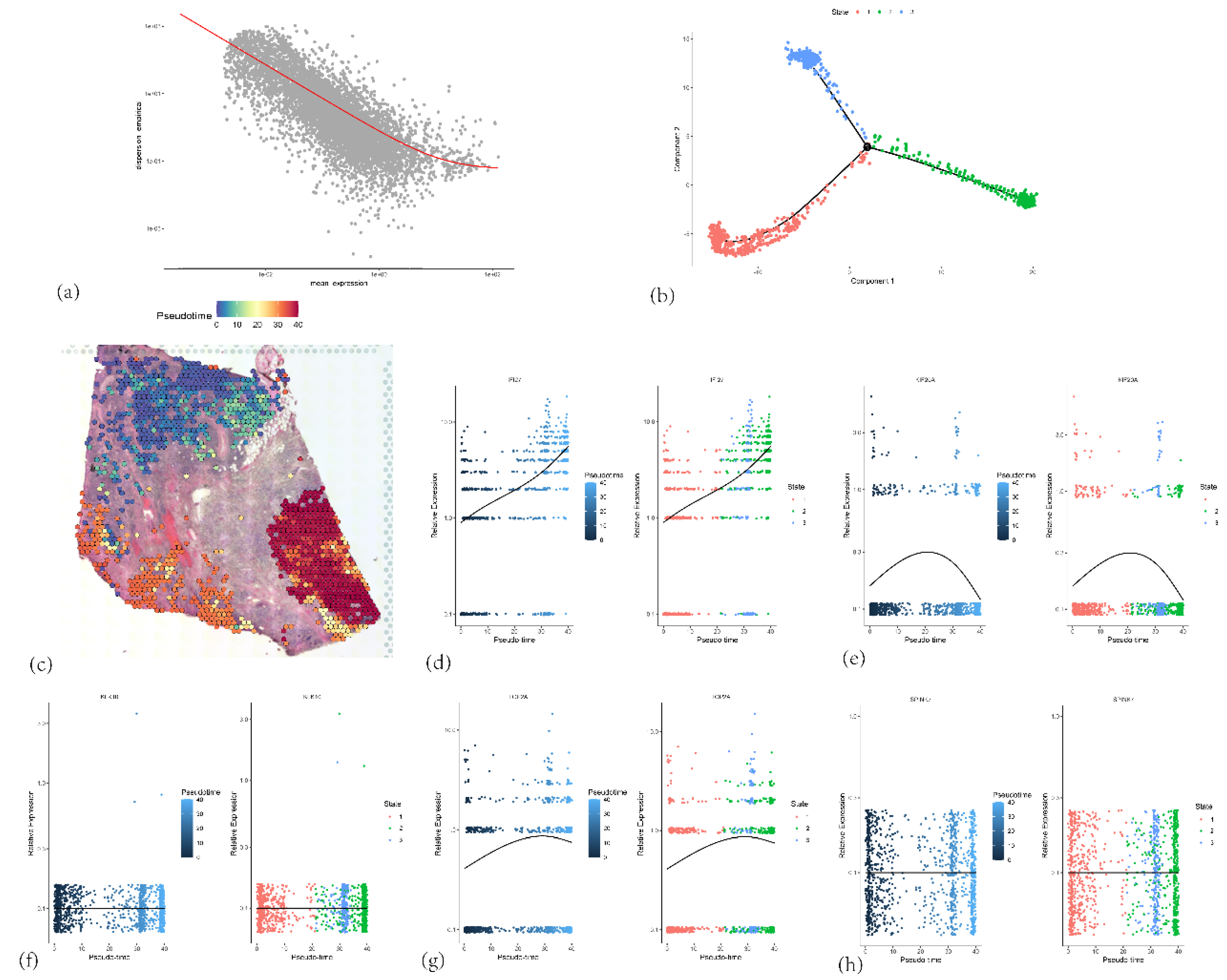

Figure 18.

(a) Relationship between gene expression intensity and stability in ductal epithelial cells. (b) Branch states of ductal epithelial cell subpopulations (c) Spatial distribution of pseudotime values, with color gradient reflecting the temporal progression of cellular differentiation. (d, e, f, g, h) Expression patterns of five core genes in relation to pseudotime.

Figure 18.

(a) Relationship between gene expression intensity and stability in ductal epithelial cells. (b) Branch states of ductal epithelial cell subpopulations (c) Spatial distribution of pseudotime values, with color gradient reflecting the temporal progression of cellular differentiation. (d, e, f, g, h) Expression patterns of five core genes in relation to pseudotime.

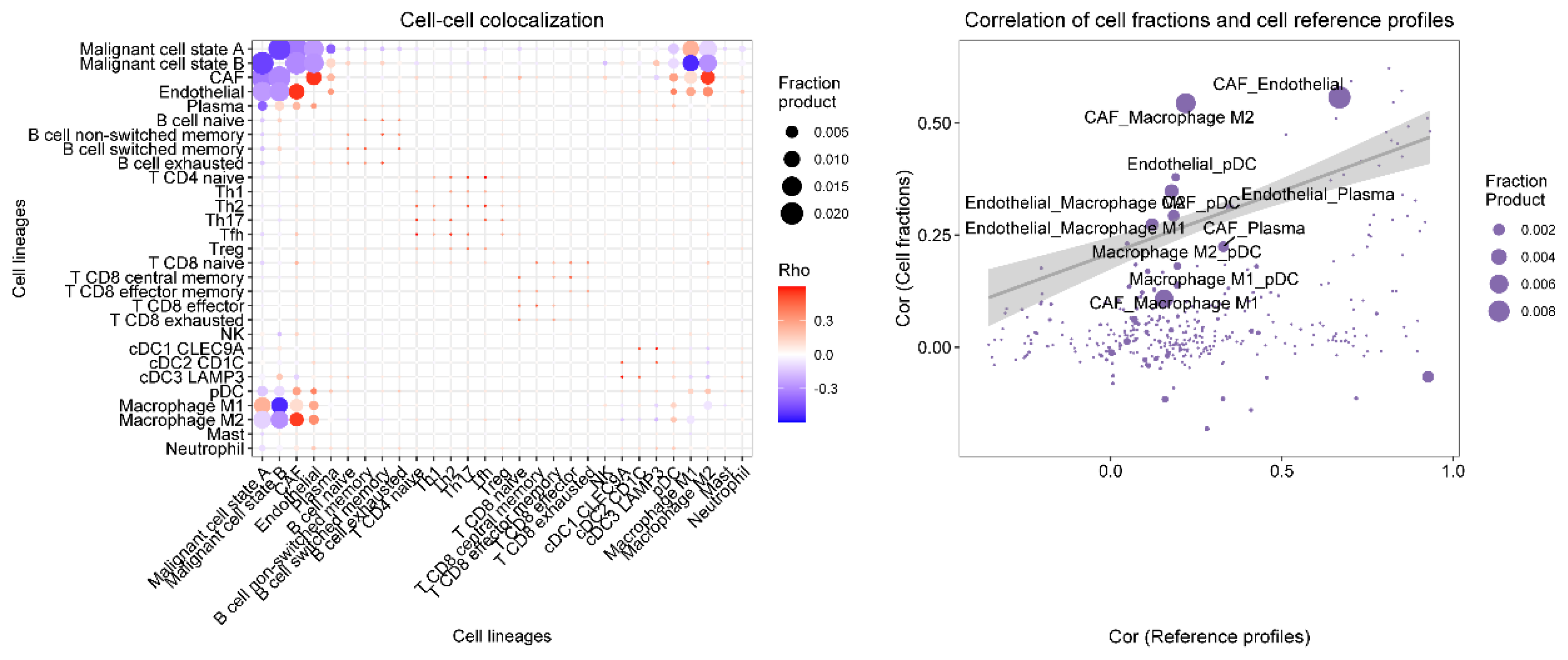

Figure 19.

The spatial colocalization characteristics and correlations of different cell types in the tumor microenvironment.

Figure 19.

The spatial colocalization characteristics and correlations of different cell types in the tumor microenvironment.

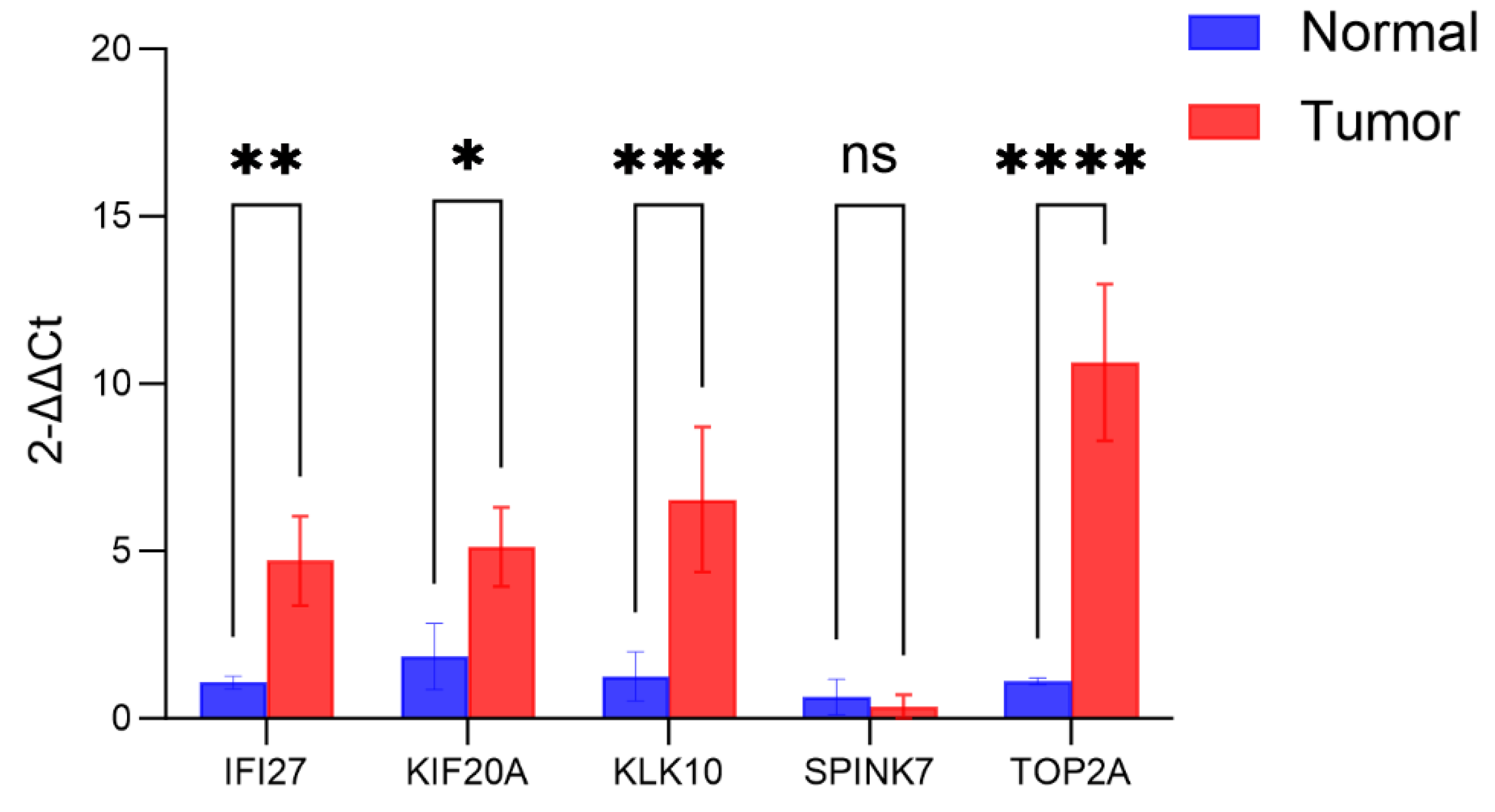

Figure 20.

The expression levels of 5 core genes in pancreatic cancer tissues and normal tissues based on PCR analysis.

Figure 20.

The expression levels of 5 core genes in pancreatic cancer tissues and normal tissues based on PCR analysis.

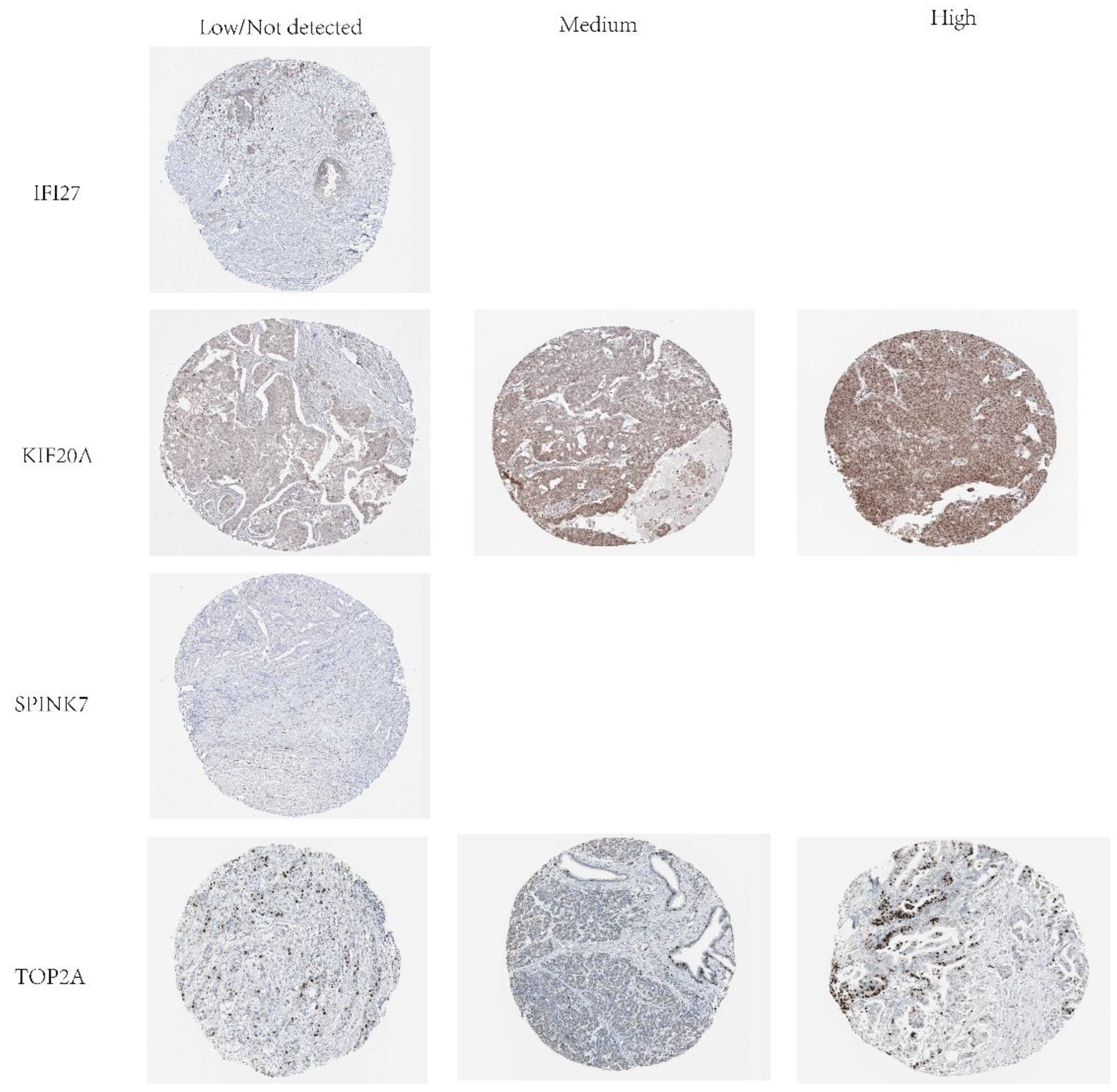

Figure 21.

Protein expression levels of IFI27, KIF20A, SPINK7 and TOP2A in PAAD tumor tissues.

Figure 21.

Protein expression levels of IFI27, KIF20A, SPINK7 and TOP2A in PAAD tumor tissues.