Submitted:

20 January 2023

Posted:

24 January 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Definition of Mitotic Network Activity Index (MNAI)

2.2. Datasets

2.3. Biological Evaluation of MNAI

2.4. Clinical Evaluation of MNAI

2.5. Multimodal Integration and Evaluation of MNAI and Cellular Morphometric Subtype

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

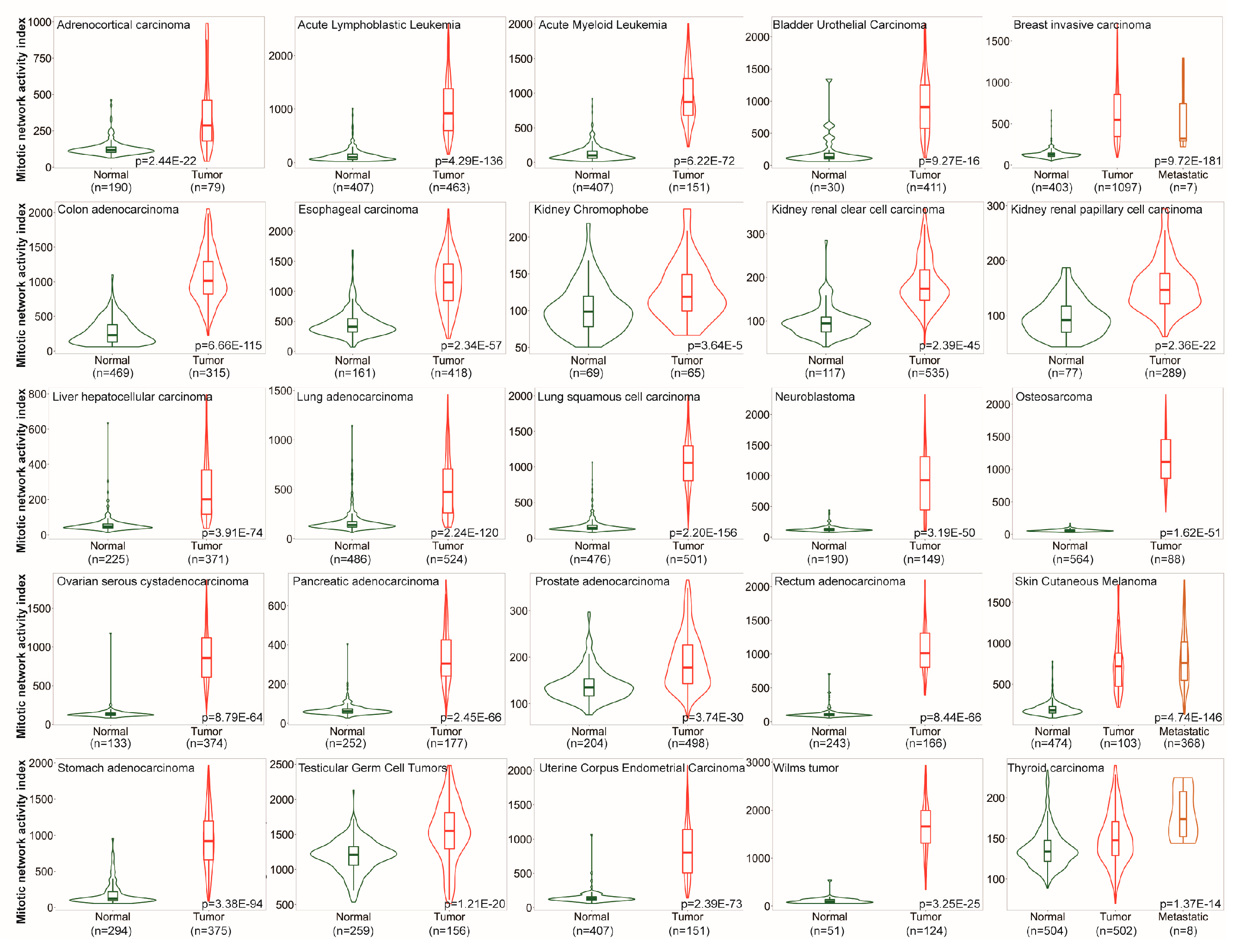

3.1. MNAI is Signficantly Elevated in Tumors compared to Normal Samples

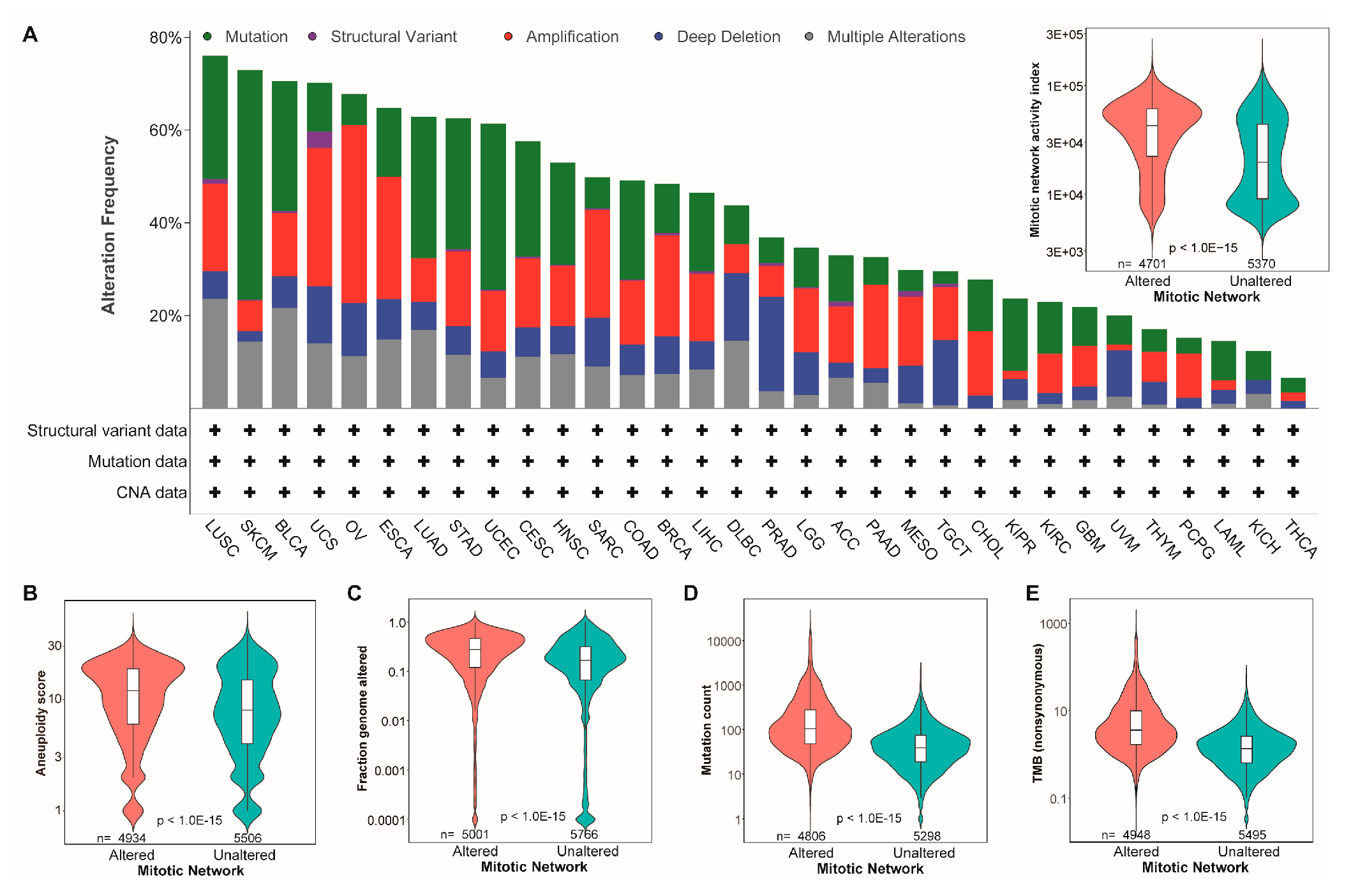

3.2. The MNAI Significantly Associates with Genetic Instability

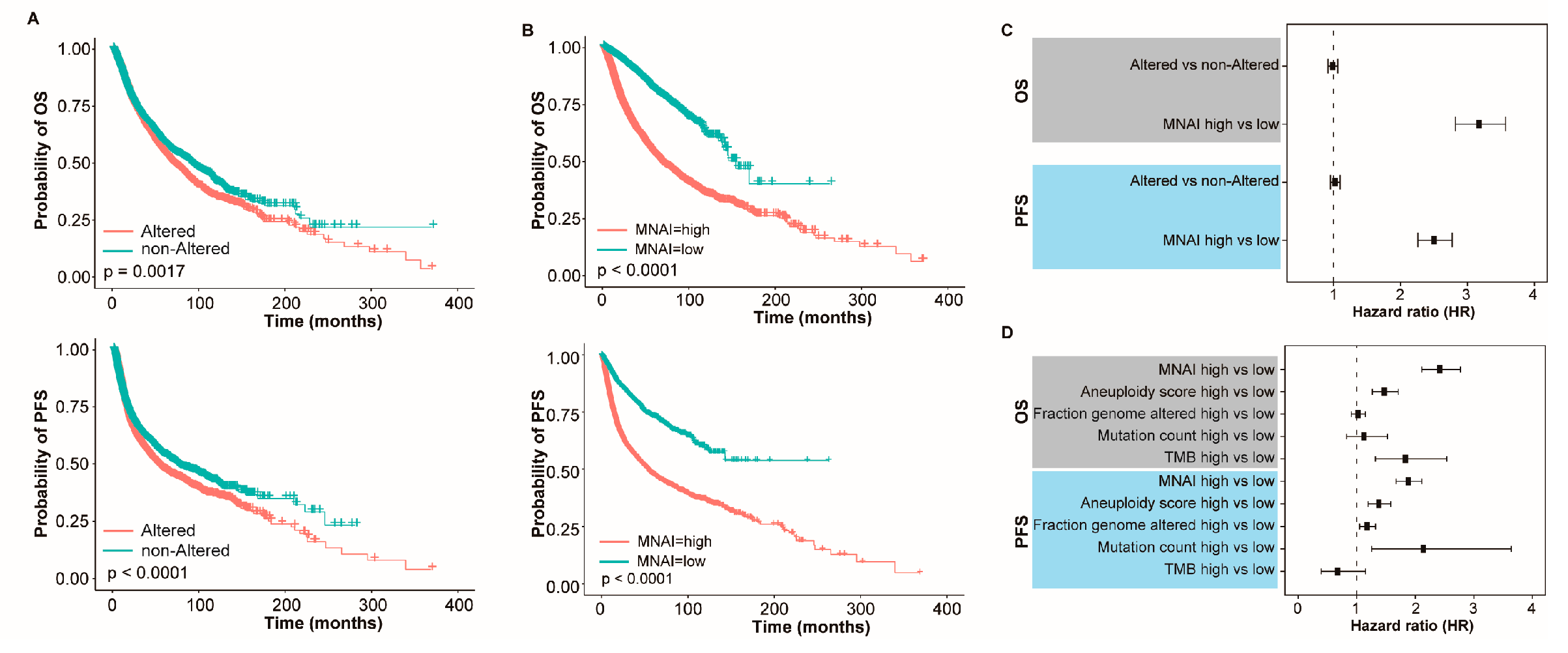

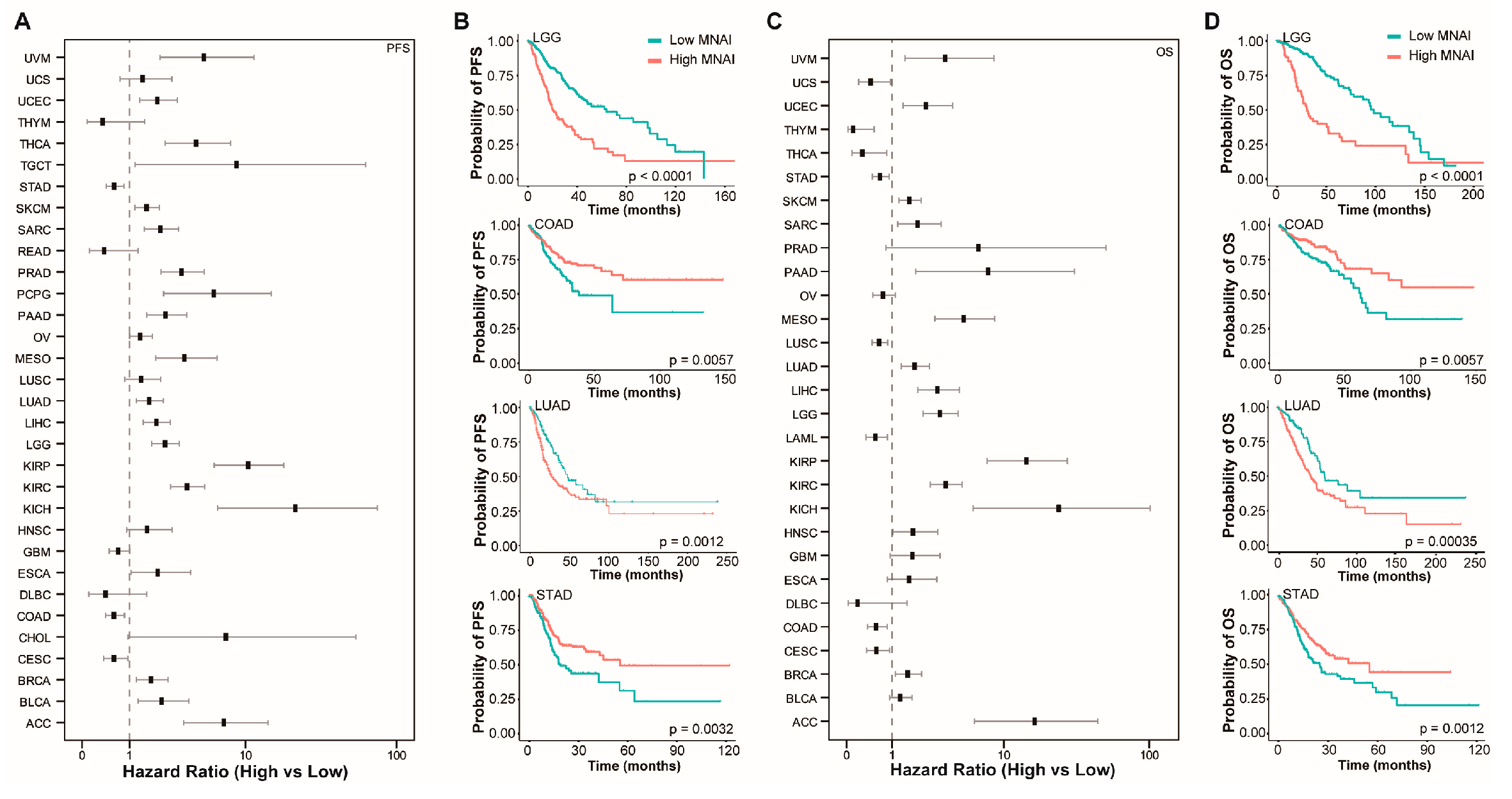

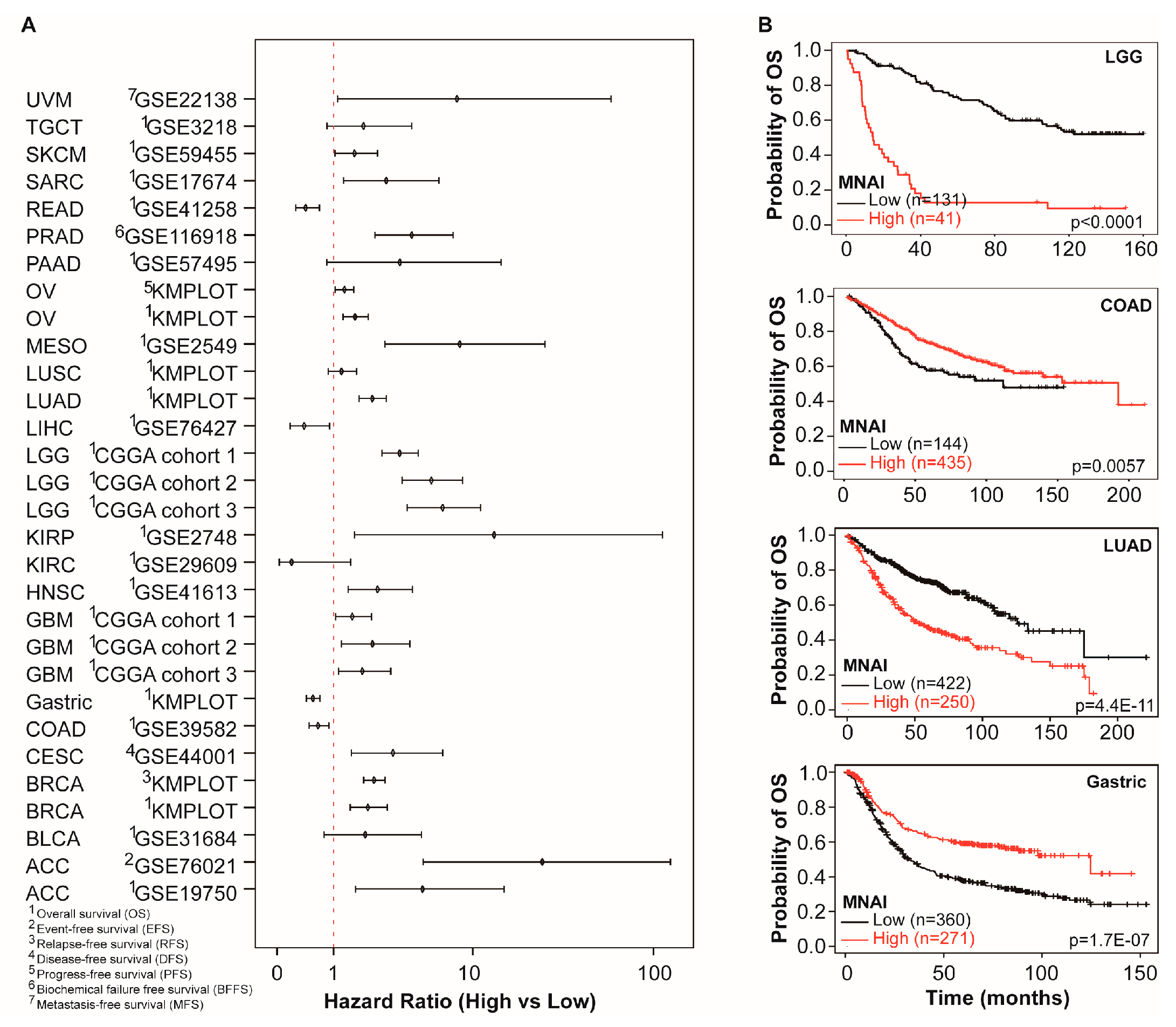

3.3. MNAI Signficantly Associates with Prognosis

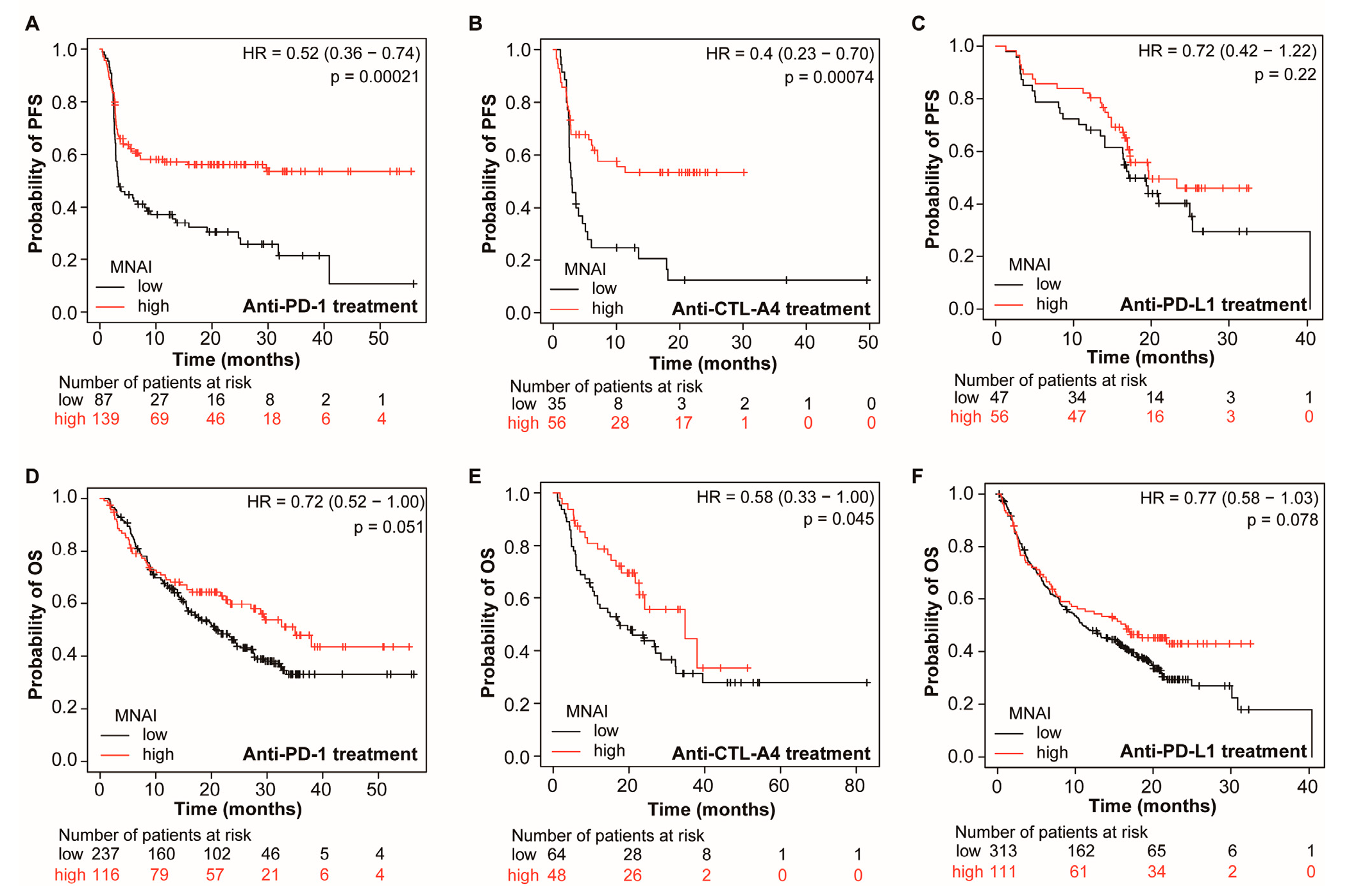

3.4. MNAI Predicts the Beneficial Effects of Immunotherapy

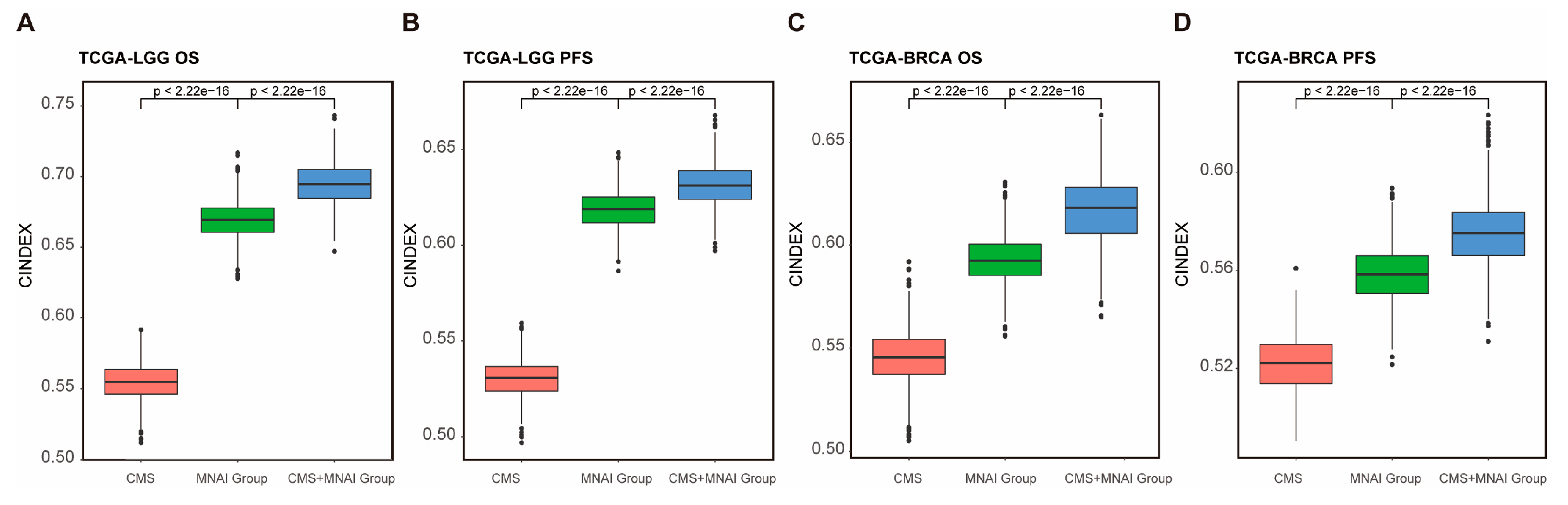

3.5. Multimodal integration of MNAI and CMS significantly improve the predictive power of prognosis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeshima, H.; Ushijima, T. Accumulation of genetic and epigenetic alterations in normal cells and cancer risk. npj Precision Oncology 2019, 3, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, S.Y.; Choi, M.; Lee, T.; Park, C.K. The Prognostic Role of Mitotic Index in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patients after Curative Hepatectomy. Cancer Res Treat 2016, 48, 180–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philips, P.; Kooby, D.A.; Maithel, S.; Merchant, N.B.; Weber, S.M.; Winslow, E.R.; et al. Grading Using Ki-67 Index and Mitotic Rate Increases the Prognostic Accuracy of Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Pancreas 2018, 47, 326–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, W.O.; Cohen, J.; Enzinger, F.; Hajdu, S.I.; Heise, H.; Martin, R.G.; et al. A clinical and pathological staging system for soft tissue sarcomas. Cancer 1977, 40, 1562–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medri, L.; Volpi, A.; Nanni, O.; Vecci, A.M.; Mangia, A.; Schittulli, F.; et al. Prognostic relevance of mitotic activity in patients with node-negative breast cancer. Mod Pathol 2003, 16, 1067–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romansik, E.M.; Reilly, C.M.; Kass, P.H.; Moore, P.F.; London, C.A. Mitotic Index Is Predictive for Survival for Canine Cutaneous Mast Cell Tumors. Veterinary Pathology 2007, 44, 335–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-J.; Ketter, R.; Steudel, W.-I.; Feiden, W. Prognostic Significance of the Mitotic Index Using the Mitosis Marker Anti–Phosphohistone H3 in Meningiomas. American Journal of Clinical Pathology 2007, 128, 118–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Mao, J.H.; Curtis, C.; Huang, G.; Gu, S.; Heiser, L.; et al. Genome co-amplification upregulates a mitotic gene network activity that predicts outcome and response to mitotic protein inhibitors in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res 2016, 18, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaillard, H.; García-Muse, T.; Aguilera, A. Replication stress and cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer 2015, 15, 276–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vader, G.; Lens, S.M. The Aurora kinase family in cell division and cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta 2008, 1786, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, C. Genomic profiling of breast cancers. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2015, 27, 34–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, S.L.; Eklund, A.C.; Kohane, I.S.; Harris, L.N.; Szallasi, Z. A signature of chromosomal instability inferred from gene expression profiles predicts clinical outcome in multiple human cancers. Nat Genet 2006, 38, 1043–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strebhardt, K.; Becker, S.; Matthess, Y. Thoughts on the current assessment of Polo-like kinase inhibitor drug discovery. Expert Opin Drug Discov 2015, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.-P.; Jin, X.; Seyed Ahmadian, S.; Yang, X.; Tian, S.-F.; Cai, Y.-X. Clinical significance and molecular annotation of cellular morphometric subtypes in lower-grade gliomas discovered by machine learning. Neuro-Oncology 2022, noac154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Yang, X.; Moore, J.; Liu, X.-P.; Jen, K.-Y.; Snijders, A.M.; et al. From Mouse to Human: Cellular Morphometric Subtype Learned From Mouse Mammary Tumors Provides Prognostic Value in Human Breast Cancer. Frontiers in Oncology 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- XY M, J P-L, M A, M R-G, CA R, JH M, et al. iCEMIGE: Integration of CEll-morphometrics, MIcrobiome, and GEne biomarker signatures for risk stratification in breast cancers. World Journal of Clinical Oncology 2022, 13, 616–29. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ma, X.; Hu, H. The Influence of Cell Cycle Regulation on Chemotherapy. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strickler, J.H.; Hanks, B.A.; Khasraw, M. Tumor Mutational Burden as a Predictor of Immunotherapy Response: Is More Always Better? Clin Cancer Res 2021, 27, 1236–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristescu, R.; Aurora-Garg, D.; Albright, A.; Xu, L.; Liu, X.Q.; Loboda, A.; et al. Tumor mutational burden predicts the efficacy of pembrolizumab monotherapy: a pan-tumor retrospective analysis of participants with advanced solid tumors. J Immunother Cancer 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssen, A.; Kops, G.J.; Medema, R.H. Elevating the frequency of chromosome mis-segregation as a strategy to kill tumor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009, 106, 19108–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ippolito, M.R.; Martis, V.; Martin, S.; Tijhuis, A.E.; Hong, C.; Wardenaar, R.; et al. Gene copy-number changes and chromosomal instability induced by aneuploidy confer resistance to chemotherapy. Dev Cell 2021, 56, 2440–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.; Pachynski, R.K.; Narayan, V.; Fléchon, A.; Gravis, G.; Galsky, M.D.; et al. Nivolumab Plus Ipilimumab for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer: Preliminary Analysis of Patients in the CheckMate 650 Trial. Cancer Cell 2020, 38, 489–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibney, G.T.; Weiner, L.M.; Atkins, M.B. Predictive biomarkers for checkpoint inhibitor-based immunotherapy. Lancet Oncol 2016, 17, e542–e51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, M.; Aoudjeghout, W.; Pimpie, C.; Pocard, M.; Mirshahi, M. Mitosis in Cancer Cell Increases Immune Resistance via High Expression of HLA-G and PD-L1. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R.; Chaudhary, K.; Gupta, S.; Singh, H.; Kumar, S.; Gautam, A.; et al. CancerDR: cancer drug resistance database. Sci Rep 2013, 3, 1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Borowsky, A.; Barner, K.; Spellman, P.; Parvin, B. Stacked Predictive Sparse Decomposition for Classification of Histology Sections. International Journal of Computer Vision 2014, 13, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).