Submitted:

10 August 2025

Posted:

11 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Literature Corpus and Selection Strategy

2.2. Data Extraction and Synthesis

- Initial Familiarization: Each of the provided documents was reviewed in full to gain a comprehensive understanding of its scope, methodology, key findings, and conclusions. This step was crucial for identifying the core arguments and evidence presented in each paper.

-

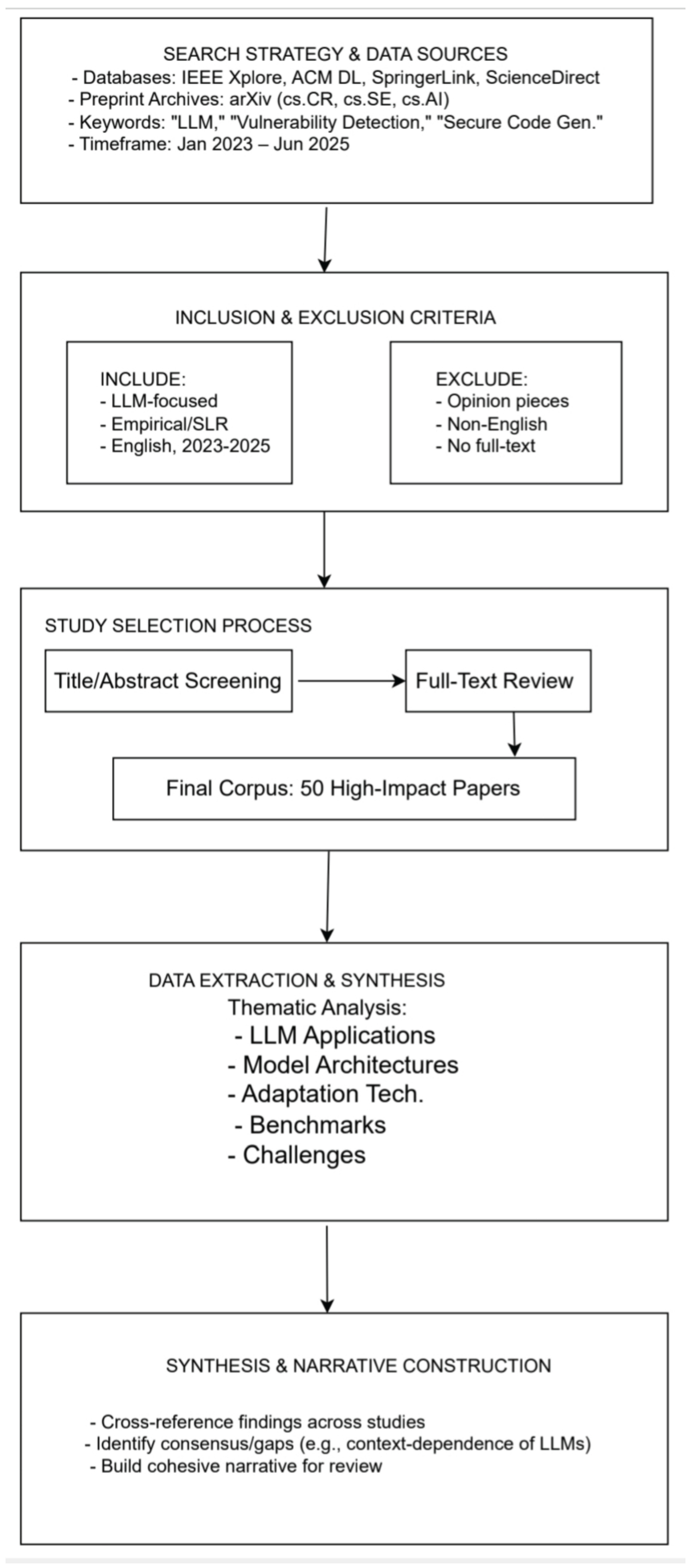

Thematic Data Extraction: Key information was systematically extracted from each paper and organized around predefined themes relevant to our research questions. These themes included:

- Model Architectures: The types of LLMs employed (encoder-only, decoder-only, encoder-decoder) and their suitability for different tasks.

- Adaptation Techniques: Methods used to specialize LLMs, such as fine-tuning (full and parameter-efficient) and prompt engineering (e.g., zero-shot, few-shot, Chain-of-Thought).

- Identified Challenges: Recurring limitations such as high false positive rates, lack of interpretability, and the risk of generating insecure code.

- Future Directions: Proposed areas for future research and development.

- Synthesis and Narrative Construction: The extracted data was then analyzed to identify points of consensus, divergence, and research gaps across the literature. The synthesis focused on integrating these findings into a cohesive narrative that accurately represents the current state of the field. For example, we cross-referenced findings on the importance of context for LLM performance from empirical studies [[37,38,39,40],] with the broader conclusions of systematic reviews [[41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49]]. This method allowed us to build a comprehensive picture, moving beyond a simple summary of individual papers to a critical evaluation of the field as a whole. The resulting analysis forms the core sections of this review.

3. Methodology

-

Search Strategy and Data SourcesA structured literature search was conducted targeting major academic databases and preprint archives to capture both peer-reviewed and cutting-edge research. The primary data sources included:

- Academic Databases: IEEE Xplore, ACM Digital Library, SpringerLink, and ScienceDirect.

- Preprint Archives: arXiv (specifically the cs.CR, cs.SE, and cs.AI categories).

The search queries combined keywords related to large language models (e.g., "Large Language Model," "LLM," "Generative AI," "GPT") with terms related to software security (e.g., "vulnerability detection," "automated program repair," "software security," "secure coding," "exploit generation"). The search was restricted to a timeframe of January 2023 to June 2025 to ensure the review focused on the most recent advancements in this fast-evolving field. -

Inclusion and Exclusion CriteriaTo ensure the relevance and quality of the selected literature, a strict set of inclusion and exclusion criteria was applied during the screening process.Inclusion Criteria:

- The study’s primary focus must be on the application or analysis of LLMs in the context of software security.

- The paper must be an empirical study, a systematic literature review (SLR), a case study with clear data, or a framework proposal with an evaluation.

- The article must be published in English.

- The publication date must fall within the specified timeframe (2023-2025).

Exclusion Criteria:- Opinion pieces, editorials, or articles without empirical data or a structured review methodology.

- Studies where LLMs are mentioned but are not the central focus of the security application.

- Papers that were not available in full-text.

- Articles published in languages other than English.

-

Study Selection and SynthesisA two-stage screening technique was used in the selecting process. All retrieved publications’ titles and abstracts were first examined in light of the inclusion and exclusion criteria. After passing this preliminary screening, studies were subjected to a full-text review to verify their methodological rigour and relevance. This review is based on a final corpus of 50 high-impact papers that were chosen from this approach.

4. Methodological Organization

-

The Evolving Landscape of LLMs in Software SecurityOne of the biggest and most disruptive changes in contemporary software engineering is the incorporation of Large Language Models (LLMs) into the software development lifecycle. These models, which can comprehend and produce increasingly complex code, offer a dual-use paradigm that is changing the software security landscape. On the one side, LLMs are being used as effective defensive tools, automating labour-intensive, error-prone, and manual activities. However, because they rely on large, frequently unclean public code repositories for training, there is a significant concern that LLMs themselves could be used to spread existing security flaws or perhaps create new ones.The main problem facing the research community is how to optimise LLMs’ enormous potential for enhancing software security while also reducing the hazards that come with them. When these models’ code is carelessly included into applications, it can present minor vulnerabilities that bad actors could take advantage of. A new aspect of software supply chain risk has emerged as a result, whereby AI tools used to speed up development may unintentionally jeopardise the final product’s security. By looking at the main uses, approaches, and difficulties that characterise the present situation of LLMs in software security, the ensuing sections investigate this terrain.

-

Large Language Models for Vulnerability DetectionAutomated vulnerability discovery is one of the most promising uses of LLMs in cybersecurity. Early investigations into the capabilities of early models frequently yielded conflicting findings, with studies pointing to problems with high false-positive rates and unreliability. More recent research, however, has clearly come to the conclusion that the quality and depth of the context an LLM is given has a significant impact on how well it does in vulnerability identification.Many classes of vulnerabilities are difficult for LLMs to correctly discover when tested on isolated, out-of-context code snippets. When they have access to a more comprehensive picture of the program, which includes details about data flow, control flow, variable scope, and inter-procedural relationships, their performance significantly improves. The main obstacle is a restriction in understanding about intricate code relationships without enough information, not a failure to identify vulnerability patterns.To address this, current research focuses on developing methodologies that enrich the input provided to the LLM. This includes leveraging traditional program analysis techniques to extract and abstract relevant contextual information, thereby filtering out noise and presenting the model with a more focused and informative prompt. This shift from simple binary classification ("is this code vulnerable?") to context-aware analysis represents a significant maturation of the field, enabling LLMs to move closer to emulating the nuanced understanding of a human security expert.

-

Automated Program Repair (APR) with Large Language ModelsBecause of their generative capabilities, LLMs are well suited for Automated Program Repair (APR), which goes beyond simple defect identification to automatically fix found issues. This capacity ranges from repairing basic programming errors to addressing intricate security flaws, with the ultimate goal of developing "self-healing" software systems.The calibre of the cues used to direct the model has a direct impact on how well LLM-based APR works. Advanced methods entail giving the LLM a wealth of data to direct the restoration procedure. For example, the model can produce more conceptually sound and accurate fixes if it is given the design rationale, which is the high-level conceptual planning, intent, and reasoning that a human developer uses prior to writing code and is frequently found in developer comments, commit messages, or issue logs. This methodology simulates the human development process by providing the AI with insight into the "why" of the code, rather than just the "what."

-

Architectures, Adaptation, and Optimization TechniquesThe evolution of LLMs for code has been marked by shifts in both model architecture and the techniques used to adapt them for security-specific tasks.Model Architectures: The kinds of models being used in the field have clearly evolved. Early research frequently used encoder-only models, which are excellent at comprehending and categorising code (e.g., BERT and its descendants like CodeBERT). Although they are still useful for some analysis tasks, decoder-only models (like the GPT series and Llama) and encoder-decoder models (like T5) are becoming more and more popular. Because these designs are generative by nature, they are far better suited to the job of producing security explanations, code fixes, and other natural language artefacts that are essential to a contemporary security workflow. This tendency towards structures specifically designed for the subtleties of programming languages is further exemplified by the creation of specialised, code-native models such as CodeLlama and CodeGemma. .Adaptation and Optimization: To bridge the gap between general-purpose models and the specific demands of software security, two primary adaptation strategies are prevalent:

- Fine-Tuning: A pre-trained model is retrained on a smaller, domain-specific dataset in this procedure. This entails specialising the model for software security by utilising carefully selected datasets of susceptible code, security patches, and other pertinent examples. The community has widely adopted Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning (PEFT) techniques, like Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA), which enable significant task-specific adaptation by updating only a small proportion of the model’s parameters, in response to the enormous computing cost of full fine-tuning.

- Prompt Engineering: Prompt engineering, a potent and adaptable substitute or addition to fine-tuning, concentrates on carefully constructing the input to the LLM. From straightforward zero-shot or few-shot prompts to more complex, multi-step reasoning techniques, the research shows a definite trend. It has been demonstrated that methods like as Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting, which leads the model through an explicit reasoning process, greatly enhance performance on challenging code analysis and repair jobs.

-

Evaluation and Benchmarking: Measuring What MattersThe capacity to thoroughly assess the efficacy of LLM-based security technologies is essential to their advancement. The constraints of the available datasets, which typically included unfinished, non-executable code snippets and lacked standardised evaluation metrics, regularly hindered early attempts in this field. Because of this, it was challenging to evaluate and contrast the capabilities of various models with accuracy.In response, the research community has focused on developing a new generation of robust benchmarks and evaluation frameworks. These modern benchmarks are characterized by several key features designed to enable more reliable and automated assessment:

- Executable Code and Test Cases: Instead of isolated snippets, new benchmarks provide complete, runnable programs along with a suite of test cases. This allows for the automated evaluation of functional correctness using metrics like Pass@k, which measures the likelihood that a model generates a correct solution within k attempts.

- Real-World Difficulty Metrics: Metrics from real-world situations are starting to be incorporated into benchmarks to give a more realistic assessment of task difficulty. For instance, the "First Solve Time" (FST), which is the amount of time it took the first human team to solve a problem, can be used to objectively quantify the difficulty of assignments from professional Capture the Flag (CTF) contests.

- Granular Process Evaluation: Acknowledging that intricate security jobs need several processes, sophisticated frameworks are presenting the idea of "subtasks." This makes it possible to assess an LLM agent’s approach to problem-solving at a more detailed level. The agent’s capacity to finish intermediate tasks can be assessed, even if it is unable to accomplish the ultimate goal (such as capturing the flag), which offers important information about its shortcomings.

-

Persistent Challenges and the Road AheadNotwithstanding the quick advancements, the literature agrees that a number of enduring issues need to be resolved in order to fully utilise LLMs in software security. Reliability and false positives continue to be major concerns. Models that repeatedly identify secure code as insecure or offer inaccurate fixes can undermine developer confidence and cause "alert fatigue," which eventually reduces the usefulness of the models.The "black-box" nature and lack of interpretability of many LLMs pose another significant hurdle. For security-critical applications, it is often not enough for a model to simply provide an answer; developers and security analysts need to understand the reasoning behind the model’s conclusion to trust and verify it.Additionally, a fundamental difficulty remains the representativeness and quality of training data. The models may unintentionally pick up and spread biases and security vulnerabilities from the large public codebases utilised for pre-training. This brings up the most important risk: the possibility that LLMs could create a false impression of security by introducing new, subtle flaws when trying to build or repair code.The way forward entails a multifaceted research endeavour aimed at conquering these obstacles. A particularly intriguing path is the creation of hybrid systems, which combine the deterministic accuracy of formal methods and classical static analysis with the probabilistic, pattern-matching capabilities of LLMs. The investigation of multi-agent frameworks is another crucial field in where many LLMs, sometimes with varying specialisations, can cooperate, discuss, and validate one another’s findings to provide more solid and trustworthy results. Lastly, to remove the curtain of opacity, make model thinking explicit, and encourage the human-in-the-loop cooperation required to develop the next generation of reliable, AI-powered security technologies, a sustained and heightened focus on explainable AI (XAI) is crucial.

- (a)

-

Critique of Datasets and Benchmarks: The Risk of "Teaching to the Test"When it comes to AI research, the saying "what gets measured gets improved" has two sides. Although the drive for more reliable, executable benchmarks is a step in the right direction, there is a chance that it will lead to the emergence of a new type of overfitting. Significant biases exist in many of the security datasets available today, even those that are based on actual vulnerabilities. They might under-represent more subtle, logic-based, or architectural vulnerabilities while over-representing some common vulnerability types (such as buffer overflows or SQL injection). Because of this lack of diversity, models that are very good at benchmark tasks may become fragile and ineffectual when confronted with new, out-of-distribution dangers in the wild.Additionally, rather than understanding the fundamentals of secure coding, the research community may unintentionally optimise models to take advantage of the benchmarks’ own artefacts, a phenomenon known as benchmark decay. This leads to a "teach-to-the-test" situation in which advancements on a leaderboard metric might not result in a significant enhancement in security in the actual world, creating a fictitious impression of progress.

- (b)

-

Open-Source vs. Proprietary Models: The Trust and Auditability DilemmaThe choice between using proprietary, closed-source models (e.g., OpenAI’s GPT-4, Anthropic’s Claude) and open-source models (e.g., Llama, Mixtral) has profound implications for security applications.

- Proprietary Models: These models are readily available through APIs and frequently reflect the state-of-the-art in terms of raw capacity. However, there are serious problems with auditability and trust when they are used in security workflows. There is a serious risk to data privacy when using a third-party, closed-source methodology to analyse sensitive, proprietary source code. Organisations are also vulnerable to the terms of service, fees, and prospective API updates of the provider, and their "black-box" nature makes it impossible to thoroughly examine their training data for biases or potential backdoors.

- Open-Source Models: The issue of auditability and privacy can be resolved with open-source models. Because they can be hosted locally, businesses can examine code without disclosing it to outside parties. More examination of their architecture and, in some situations, their training data is made possible by their transparency. Nevertheless, open-source models need a lot of internal knowledge and processing power to properly optimise, implement, and maintain, and they might not perform as well as their proprietary equivalents in terms of state-of-the-art performance.

The unresolved challenge for the field is how to balance the cutting-edge performance of proprietary systems with the transparency, control, and privacy benefits of open-source alternatives. - (c)

-

Ethical Considerations and Responsible AIThe power of LLMs to analyze and generate code creates a new set of ethical responsibilities that the community is only beginning to address.

- Data Privacy and Intellectual Property: Code with different licenses and perhaps sensitive information contained in comments or commit history are inevitable when LLMs are taught on public repositories. There is serious ethical and legal concern about the possibility that these models will "regurgitate" private information or bits of proprietary code. Data sanitisation and intellectual property compliance in model training require clear guidelines.

- Dual-Use and Model Misuse:By definition, an LLM who is skilled at discovering vulnerabilities and addressing them is also skilled at recognising them maliciously. There is a significant risk that these models may be exploited to uncover zero-day vulnerabilities at scale or automate the creation of exploits.

- Accountability and Bias: Who is at fault if a significant breach occurs as a result of an LLM-powered tool’s failure to identify a critical vulnerability? Who made the model, the company that implemented it, or the developer who used the tool? Creating distinct lines of accountability is a difficult moral and legal issue. Additionally, models may perform poorly on code written by non-native English speakers or those that utilise less typical coding styles due to biases in the training data, resulting in unequal protection.

5. Discussion

5.1. Synthesis of Findings: Beyond Detection to Reasoning

5.2. Trends and Future Trajectory: Towards Hybrid, Verifiable Systems

5.3. Limitations and Gaps in Existing Work

- The Interpretability Problem: The "black-box" nature of LLMs remains a fundamental barrier to their adoption in security-critical domains. If a model cannot explain why it has flagged a piece of code as vulnerable or why its proposed patch is secure, developers and security analysts cannot be expected to trust it. The lack of progress in explainable AI (XAI) for code is a major bottleneck for the entire field.

- Reliability and False Positives: While context improves accuracy, the issue of false positives has not been eliminated. High noise levels from security tools can lead to alert fatigue, causing developers to ignore warnings and eroding trust in the system. The challenge is to maintain high recall without sacrificing precision to the point where the tool becomes impractical.

- Security of the LLMs Themselves: A crucial and still under-explored area is the risk of the LLMs themselves introducing new, more subtle vulnerabilities. The potential for data poisoning attacks on training data or the inadvertent generation of insecure-but-functional code represents a systemic risk. Much of the current research focuses on using LLMs as a tool, with less attention paid to securing the tool itself.

- Scalability and Real-World Complexity: Most evaluations, even the more advanced ones, are still conducted on function- or file-level code. There is a significant gap in understanding how these models perform on large, complex, multi-repository enterprise codebases where vulnerabilities often emerge from the unforeseen interactions between disparate components.

5.4. Contribution of This Review

6. Conclusion

References

- E. Basic and A. Giaretta, “Large language models and code security: A systematic literature review,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.15004, 2024. [CrossRef]

- N. Tihanyi, R. Jain, Y. Charalambous, M. A. Ferrag, Y. Sun, and L. C. Cordeiro, “A new era in software security: Towards self-healing software via large language models and formal verification,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.14752, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Temitope, “Automated security-aware code generation with large language models (llms),” 02 2025.

- Y. Zhang, W. Song, Z. Ji, N. Meng et al., “How well does llm generate security tests?” arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.00710, 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. C. Das, M. H. Amini, and Y. Wu, “Security and privacy challenges of large language models: A survey,” ACM Computing Surveys, vol. 57, no. 6, pp. 1–39, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Y. Nong, M. Aldeen, L. Cheng, H. Hu, F. Chen, and H. Cai, “Chain-of-thought prompting of large language models for discovering and fixing software vulnerabilities,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.17230, 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. Huang, B. Chen, Y. Lu, S. Wu, D. Wang, Y. Huang, H. Jiang, Z. Zhou, J. Cao, and X. Peng, “Lifting the veil on the large language model supply chain: Composition, risks, and mitigations,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.21218, 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Whitman, A. El-Karim, P. Nandakumar, F. Ortega, L. Zheng, and C. James, “Adversarial-robust large language models (llms) for secured code generation assistants in devsecops,” 12 2024.

- A. K. Zhang, N. Perry, R. Dulepet, J. Ji, C. Menders, J. W. Lin, E. Jones, G. Hussein, S. Liu, D. Jasper et al., “Cybench: A framework for evaluating cybersecurity capabilities and risks of language models,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.08926, 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Mary and R. Hoover, “Enhancing software development lifecycle efficiency with generative ai: Approaches to automated code generation, testing, and continuous integration,” Automation, vol. 10, 12 2024.

- A. Lops, F. Narducci, A. Ragone, M. Trizio, and C. Bartolini, “A system for automated unit test generation using large language models and assessment of generated test suites,” 08 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Agoro and S. Andre, “A comparative study of frameworks used to evaluate large language models in automated software testing,” 01 2025.

- J. Jiang, F. Wang, J. Shen, S. Kim, and S. Kim, “A survey on large language models for code generation,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.00515, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Deng, C. S. Xia, H. Peng, C. Yang, and L. Zhang, “Large language models are zero-shot fuzzers: Fuzzing deep-learning libraries via large language models,” in Proceedings of the 32nd ACM SIGSOFT international symposium on software testing and analysis, 2023, pp. 423–435.

- Q. Zhang, T. Zhang, J. Zhai, C. Fang, B. Yu, W. Sun, and Z. Chen, “A critical review of large language model on software engineering: An example from chatgpt and automated program repair,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.08879, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Mohsin, H. Janicke, A. Wood, I. H. Sarker, L. Maglaras, and N. Janjua, “Can we trust large language models generated code? a framework for in-context learning, security patterns, and code evaluations across diverse llms,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.12513, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Z. He, Z. Li, S. Yang, H. Ye, A. Qiao, X. Zhang, X. Luo, and T. Chen, “Large language models for blockchain security: A systematic literature review,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.14280, 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Chen and M. A. Babar, “Security for machine learning-based software systems: A survey of threats, practices, and challenges,” ACM Computing Surveys, vol. 56, no. 6, pp. 1–38, 2024. [CrossRef]

- F. N. Motlagh, M. Hajizadeh, M. Majd, P. Najafi, F. Cheng, and C. Meinel, “Large language models in cybersecurity: State-of-the-art,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.00891, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Q. Zhang, C. Fang, Y. Xie, Y. Ma, W. Sun, Y. Yang, and Z. Chen, “A systematic literature review on large language models for automated program repair,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.01466, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yao, J. Duan, K. Xu, Y. Cai, Z. Sun, and Y. Zhang, “A survey on large language model (llm) security and privacy: The good, the bad, and the ugly,” High-Confidence Computing, p. 100211, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Abdelouareth, “Ai-driven quantum software engineering: A comprehensive framework for automated code generation and optimization,” p. 3, 06 2025.

- H. Xu, S. Wang, N. Li, K. Wang, Y. Zhao, K. Chen, T. Yu, Y. Liu, and H. Wang, “Large language models for cyber security: A systematic literature review,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.04760, 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Khlaaf, P. Mishkin, J. Achiam, G. Krueger, and M. Brundage, “A hazard analysis framework for code synthesis large language models,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2207.14157, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Z. Sheng, Z. Chen, S. Gu, H. Huang, G. Gu, and J. Huang, “Large language models in software security: A survey of vulnerability detection techniques and insights,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.07049, 2025. [CrossRef]

- J. Wang, X. Luo, L. Cao, H. He, H. Huang, J. Xie, A. Jatowt, and Y. Cai, “Is your ai-generated code really safe? evaluating large language models on secure code generation with codeseceval,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.02395, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Kumar V, “Next-generation software engineering: A study on ai-augmented development, devsecops and low-code frameworks,” pp. 3048–832, 04 2025. [CrossRef]

- R. Butteddi and S. Butteddi, “Automated software generation framework: Bridging the gap between requirements and executable solutions,” International Journal of Innovative Research in Science Engineering and Technology, vol. 13, p. 15425, 08 2024.

- R. Zhu, “Securecoder: A framework for mitigating vulnerabilities in automated code generation using large language models,” Applied and Computational Engineering, vol. 116, pp. None–None, 12 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Mary and R. Hoover, “Enhancing software development lifecycle efficiency with generative ai: Approaches to automated code generation, testing, and continuous integration,” Automation, vol. 10, 12 2024.

- S. Abdali, R. Anarfi, C. Barberan, and J. He, “Securing large language models: Threats, vulnerabilities and responsible practices,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.12503, 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Pearce, B. Tan, B. Ahmad, R. Karri, and B. Dolan-Gavitt, “Examining zero-shot vulnerability repair with large language models,” in 2023 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), 2023, pp. 2339–2356. [CrossRef]

- I. Hasanov, S. Virtanen, A. Hakkala, and J. Isoaho, “Application of large language models in cybersecurity: A systematic literature review,” IEEE Access, vol. 12, pp. 176 751–176 778, 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Vadisetty, A. Polamarasetti, S. Prajapati, J. B. Butani et al., “Leveraging generative ai for automated code generation and security compliance in cloud-based devops pipelines: A review,” Available at SSRN 5218298, 2023.

- S. Hou, Z. Shen, H. Wu, J. Liang, H. Jiao, Q. Yaxian, X. Zhang, X. Li, Z. Gui, X. Guan, and L. Xiang, “Autogeeval: A multimodal and automated framework for geospatial code generation on gee with large language models,” 05 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Salek, M. Chowdhury, M. Munir, Y. Cai, M. Hasan, J. M. Tine, L. Khan, and M. Rahman, “A large language model-supported threat modeling framework for transportation cyber-physical systems,” 06 2025. [CrossRef]

- A. Raheem, I. Kolawole, A. Osilaja, and V. Essien, “Leveraging artificial intelligence for automated testing and quality assurance in software development lifecycles,” International Journal of Research Publication and Reviews, vol. 5, 12 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Alturkistani and S. Chuprat, “Artificial intelligence and large language models in advancing cyber threat intelligence: A systematic literature review,” 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Pahune and Z. Akhtar, “Transitioning from mlops to llmops: Navigating the unique challenges of large language models,” Information, vol. 16, no. 2, p. 87, 2025. [CrossRef]

- R. Pesl, “Adopting large language models to automated system integration,” 04 2025. [CrossRef]

- A. Omran Almagrabi and R. A. Khan, “Optimizing secure ai lifecycle model management with innovative generative ai strategies,” IEEE Access, vol. 13, pp. 12 889–12 920, 2025. [CrossRef]

- B. Chen, Z. Zhang, N. Langrené, and S. Zhu, “Unleashing the potential of prompt engineering in large language models: a comprehensive review,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.14735, 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Li, Y.-T. Yang, Y. Pan, and Q. Zhu, “From texts to shields: Convergence of large language models and cybersecurity,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.00841, 2025. [CrossRef]

- J. A. Goldstein, G. Sastry, M. Musser, R. DiResta, M. Gentzel, and K. Sedova, “Generative language models and automated influence operations: Emerging threats and potential mitigations,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2301.04246, 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. Peterson, “Leveraging large language models for automated code generation, testing, and debugging in modern development pipelines,” 04 2025.

- M. Sheokand and P. Sawant, “Codemixbench: Evaluating large language models on code generation with code-mixed prompts,” 05 2025. [CrossRef]

- X. Hou, Y. Zhao, Y. Liu, Z. Yang, K. Wang, L. Li, X. Luo, D. Lo, J. Grundy, and H. Wang, “Large language models for software engineering: A systematic literature review,” ACM Transactions on Software Engineering and Methodology, vol. 33, no. 8, pp. 1–79, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Bhatt, S. Chennabasappa, C. Nikolaidis, S. Wan, I. Evtimov, D. Gabi, D. Song, F. Ahmad, C. Aschermann, L. Fontana et al., “Purple llama cyberseceval: A secure coding benchmark for language models,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.04724, 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Cui, Y. Wang, C. Fu, Y. Xiao, S. Li, X. Deng, Y. Liu, Q. Zhang, Z. Qiu, P. Li et al., “Risk taxonomy, mitigation, and assessment benchmarks of large language model systems,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.05778, 2024. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).