1. Introduction

The Mediterranean Basin, characterized by its distinctive climate of hot, dry summers and mild, wet winters, plays a critical role in shaping the region’s diverse ecosystems. This climate supports a wide range of vegetation types, including dense forests, shrublands such as maquis and garrigue, coniferous and broad-leaved reforestations, and open woodlands [

1,

2].

In addition to natural factors, intensive agricultural practices, urban development, and tourism have significantly influenced the ecological dynamics of the region. Despite its rich ecological and cultural heritage, the Mediterranean Basin faces increasing environmental threats. Climate change, land degradation, and intensified human encroachment have compounded the pressures on these ecosystems. Among these challenges, forest fires represent a persistent and growing hazard, profoundly reshaping both natural landscapes and human settlements [

3,

4]. Historically, wildfires in the Mediterranean have been closely linked to climatic and ecological conditions and have long played an ecological role in maintaining and regenerating forest ecosystems [

5,

6,

7]. Lightning strikes were often the primary ignition source [

8,

9]. However, in recent decades, human activity has dramatically altered fire regimes. Urban expansion and rural abandonment have reduced traditional land management practices, leading to the accumulation of flammable biomass. The lack of silvicultural interventions has increased fuel loads and facilitated more intense fire propagation [

9,

10]. Consequently, the frequency, scale, and severity of wildfires have escalated, driven by depopulation, expanded wildland-urban interfaces, and climate change [

1,

11,

12].

Wildfires now pose a severe and escalating risk to ecological integrity, socioeconomic stability, and public safety across the Mediterranean. They can lead to the loss of biodiversity, ecosystem functions, and livelihoods, and they carry the potential for human fatalities [

13,

14,

15]. Approximately 80% of Europe’s annually burned area is concentrated in Southern regions [

16], where extensive forested landscapes and dry conditions allow large-scale fires to spread rapidly [

17,

18]. In such environments, the Mediterranean scrub’s ecological functions and services are often compromised post-fire [

19].

Climate change has become a dominant driver in shaping the fire regime of the region. Rising temperatures, extended droughts, and increased vegetation dryness intensify fire risks and alter plant community compositions [

20]. The interaction between natural conditions, climate change, and human activities creates a potent mix that heightens the probability and severity of forest fires in the Mediterranean Basin [

21].

Given this scenario, effective fire management strategies are essential to mitigate adverse impacts and preserve the ecological and cultural legacy of the Mediterranean. Shifts in fire behavior due to climate and human factors also influence post-fire regeneration trajectories, necessitating a thorough understanding of recovery dynamics to promote ecosystem resilience. Post-fire management strategies should prioritize practices that facilitate natural vegetation recovery and adapt to the evolving disturbance regimes.

Forest type, structure, and composition greatly influence vulnerability to fire. Monospecific conifer plantations, especially those poorly managed, are among the most fire-prone stands [

22,

23]. In southern Italy, conifer reforestation projects launched in past decades (e.g., Aleppo pine

Pinus halepensis Mill, maritime pine

Pinus pinaster Aiton, stone pine

Pinus pinea L.) were designed for soil stabilization and slope protection [

24]. However, their dense planting patterns and lack of silvicultural care have led to structurally homogeneous and ecologically fragile stands, often marked by unhealthy trees and excessive deadwood, further raising fire susceptibility [

25,

26,

27], particularly in a global change scenario.

Restoring fire-affected forests remains a technically challenging and economically burdensome endeavor [

28,

29]. In Italy, regulatory constraints (Law No. 353/2000) limit the scope of publicly funded post-fire remediation. As an alternative, post-fire natural regeneration, especially when supported by fencing to prevent wildlife grazing, offers a cost-effective and ecologically sound strategy to reestablish forest structure and function.

The main objective of this study was to evaluate the post-fire ecological response of a Mediterranean Aleppo pine forest seven years after a crown fire event, with a specific focus on contrasting stand types: a pure pine forest and a mixed pine–eucalyptus forest. The research pursued the following specific objectives: (1) to quantify the density, spatial distribution, and species composition of post-fire natural regeneration, and to assess whether the regeneration patterns reflect auto-successional processes or facilitate the establishment of new species; (2) to compare regeneration dynamics between forest types affected by different fire severities (high vs. moderate), with particular attention to differences in seedling abundance, height, and collar diameter; (3) to evaluate the influence of residual necromass (deadwood) on seedling recruitment and microhabitat conditions, testing its potential role as a facilitator of natural regeneration; (4) to analyze key soil physical and chemical properties (pH, organic matter content, bulk density) in both forest types, and to examine how these edaphic conditions may affect regeneration performance; (5) to identify implications for post-fire forest management, particularly regarding the effectiveness of low-intervention strategies that promote spontaneous regeneration, and to offer guidance for future restoration efforts in fire-prone Mediterranean environments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The study was conducted in the southernmost part of Sicily, Italy, within the province of Caltanissetta, in the Raffo Rosso State Forest (37°12’52’’N, 14°22’22’’E). The forest covers approximately 2,500 hectares and lies at elevations ranging from 200 to 300 meters above sea level. It is managed by the Department of State Forestry of the Sicilian Region.

In 1985, reforestation activities were carried out using Aleppo pine (Pinus halepensis) and Eucalyptus spp. The Aleppo pine plantations (hereafter referred to as the “pure pine forest”) were established at a planting density of 2,500 trees per hectare. Eucalyptus groves were managed as coppice, and Aleppo pine was planted between the rows (hereinafter called as "mixed pine forest"). Both stand types received no further silvicultural interventions after planting, resulting in dense, continuous canopy structures. The understory vegetation was dominated by Ampelodesma and Hyparrhenia species.

The region has a hot Mediterranean climate with semi-arid features, characterized by autumn-winter rainfall and a prolonged dry season from May to September. The average annual precipitation is 354.2 mm, and the mean annual temperature is 17.3 °C. According to the FAO soil classification [

30], soils are classified as Vertisols with clay textures.

In August 2016, approximately 50 hectares of forest were affected by wildfire. Fire severity was moderate in the mixed pine forest but escalated to high severity in the pure pine forest, largely due to the accumulation of dead branches on the forest floor. In the pure pine forest, the crown scorch reached 90%, with only a few surviving trees scattered throughout the area. In the mixed pine forest, crown scorch was less severe, ranging between 50% and 70%. The eucalyptus grove layer experienced partial shoot burning but little to no damage to the stumps. After the fire, all burned logs were removed from the mixed pine forest, while only 50% of burned logs were removed from the pure pine forest. The affected area was fenced to exclude grazing and allow for natural regeneration.

2.2. Vegetation and Soil Sampling

Post-fire regeneration surveys were conducted in 2023, seven years after the fire, in both stand types. Six linear transects (1 × 20 m) were established: three in the pure pine forest (TP1, TP2, TP3) and three in the mixed pine forest (TE4, TE5, TE6), all distributed along slopes with similar exposures and soil conditions. Each transect was divided into 20 plots 1 m² quadrats. Within each quadrat, all naturally regenerated seedlings were counted, and for each seedling, species, height (cm), and collar diameter (mm) were recorded. In addition, for surviving post-fire trees, diameter at breast height (DBH, cm) and total height (m) were measured.

To assess the soil conditions influencing post-fire regeneration, soil sampling was performed in 2023 at five points per both stand types (pure and mixed pine forests), located near the vegetation transects. At each point, three subsamples were collected at a depth of 0–10 cm using a hand auger and were subsequently pooled to form a composite sample. For each composite sample, the following analyses were conducted: (1) Soil pH, measured in a 1:2.5 soil–water suspension using a calibrated pH meter, following the ISO 10390 standard; (2) Organic Matter content (%), determined by loss-on-ignition (LOI) at 550 °C in a muffle furnace [

31]; (3) Bulk Density (g/cm³), determined using 100 cm³ undisturbed soil cores dried at 105 °C for 48 hours [

32]. These parameters were selected to assess soil fertility, structure, and potential influence on seedling establishment and early growth in post-fire environments.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Independent-sample T-tests and Mann–Whitney U-tests were used to assess differences in regeneration density and dendrometric parameters between forest types. The Mann–Whitney U-test, being non-parametric, was preferred when normality assumptions were not met. One-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey's test, was used to compare seedling densities across transects within each forest type. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to evaluate the relationships between regeneration density and seedling height and collar diameter. Soil parameters were compared between forest types using independent sample T-tests. All statistical tests used a significance threshold of p < 0.05. All data were analyses using the R programming language (version 4.3.2).

3. Results

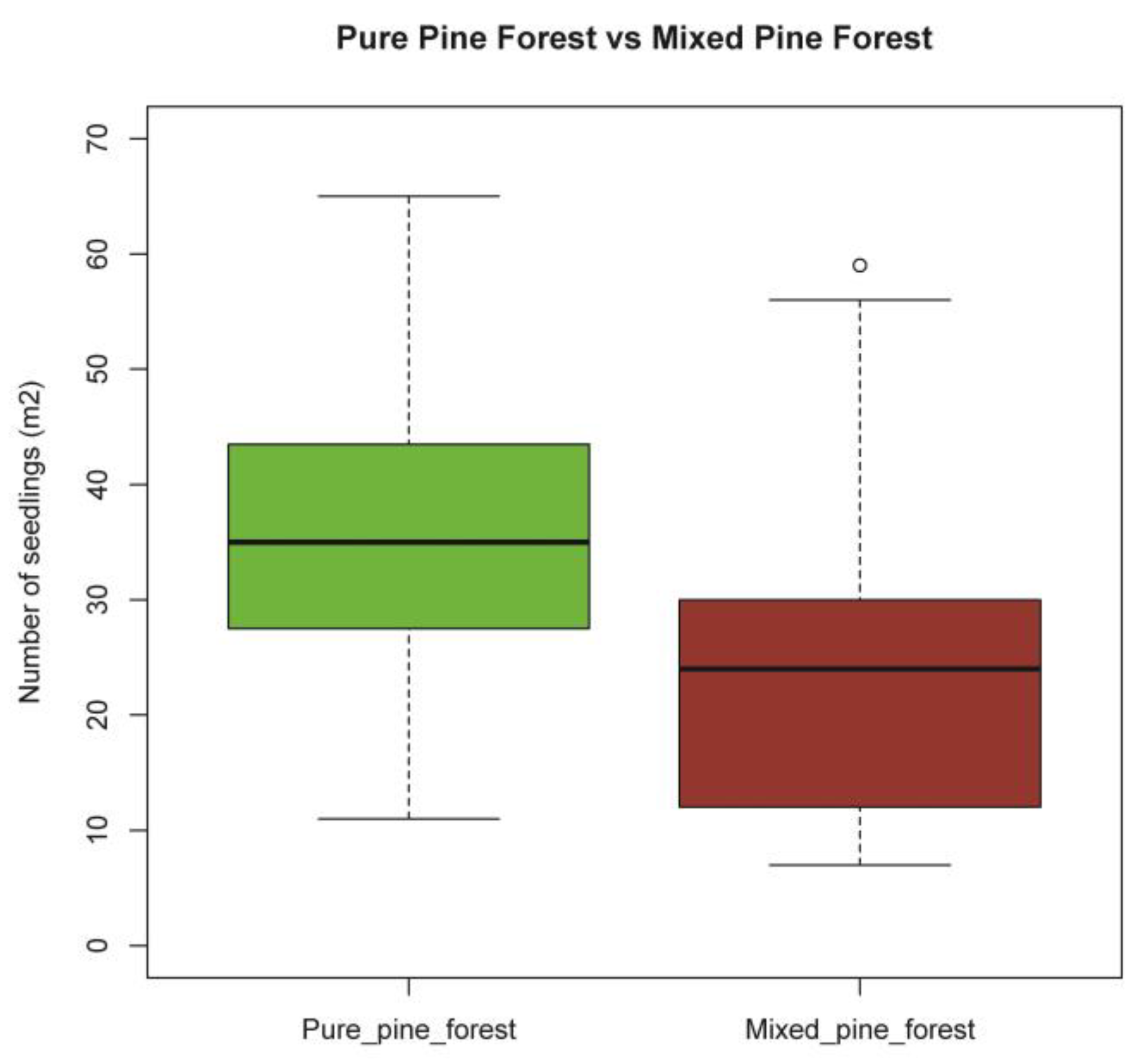

The biometric data of post-fire natural regeneration recorded seven years after the fire are shown in

Table 1. Natural regeneration was abundant and consisted exclusively of Aleppo pine, with no other woody species observed. Regeneration density was significantly higher in the pure pine forest, which was affected by high fire severity, reaching an average of 36.5 seedlings per m², compared to 23.7 seedlings per m² in the mixed pine forest, which experienced moderate fire severity (

Figure 1). These differences were statistically significant, as indicated by both the independent sample test (

Table 2).

The lower density observed in the mixed pine forest may be attributed to the partial survival of the pre-existing understory, specifically

Ampelodesma and

Hyparrhenia, whose stumps likely persisted after the moderate-severity fire and exerted competitive pressure on pine seedling establishment. In contrast, although regeneration was denser in the pure pine forest, such density may lead to increased intraspecific competition in the future, potentially resulting in self-thinning and mortality of suppressed individuals. Despite variability in seedling counts among the individual transects (

Table 1), these differences were not statistically significant within either forest type. Thus, post-fire regeneration was relatively homogeneous across the sampled plots in both the pure and mixed pine forests, although absolute seedling densities differed between them.

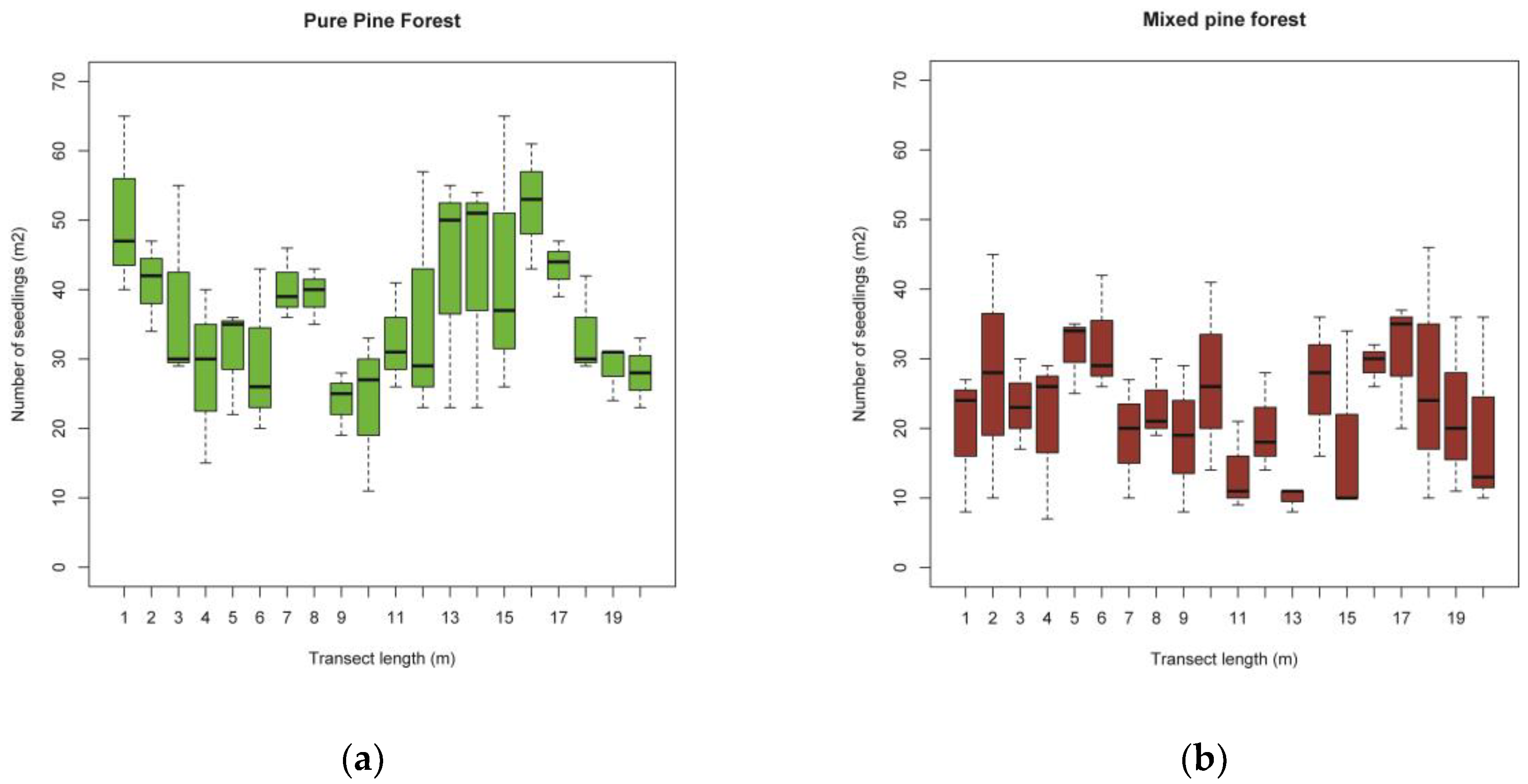

Variation in seedling numbers was also observed at the micro-plot level (individual 1 m² squares), as shown in

Figure 2. In the pure pine forest (

Figure 2b), seedling density peaked in areas where dead logs were present on the forest floor, particularly at the beginning and around the 15-meter mark of the transects. In contrast, the mixed pine forest (

Figure 2c) showed a more uniform seedling distribution along the transects, with no evident clustering, and maximum values around 6 meters (reaching approximately 32 seedlings m

-²). Notably, no coarse woody debris was observed on the ground in the mixed forest.

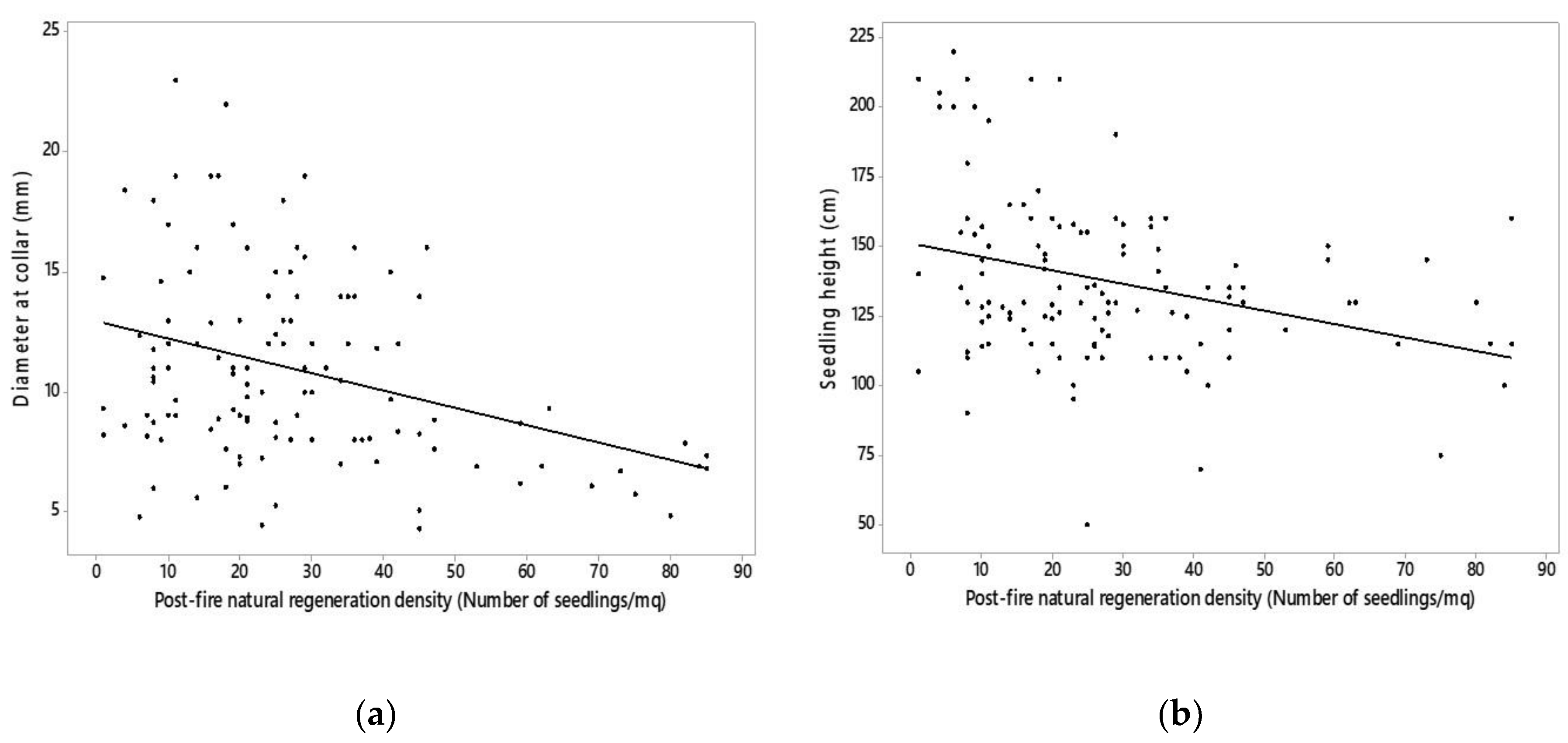

Regarding seedling growth, the mixed pine forest showed greater collar diameter and average height values than the pure pine forest (

Table 1). However, while significant differences emerged for diameters between the two stands (

Table 2), the differences for heights were not significant. The larger diameters in the mixed pine are likely due to lower regeneration density and reduced competition.

Correlations between post-fire natural regeneration density and seedling dendrometric parameters (collar diameter and height) are shown in

Figure 3. In both cases, significant negative correlations were found, suggesting that increased seedling density is associated with reduced growth. These results imply that intense post-fire regeneration leads to stronger competition for resources, thereby limiting seedling development.

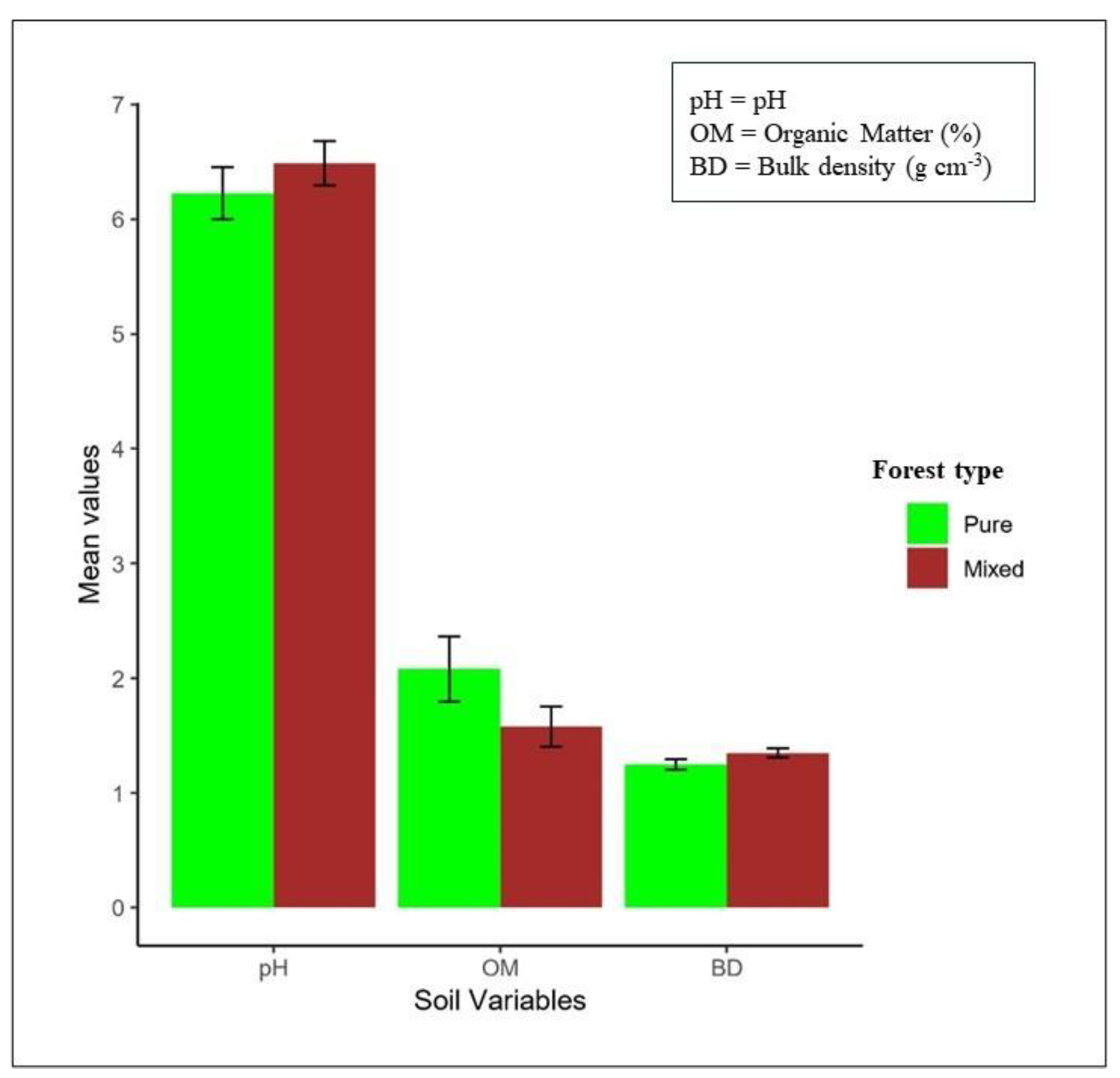

Soil analysis revealed significant differences between the two stand types (

Table 2). The pure pine forest exhibited a lower pH (mean = 6.23 ± 0.22) compared to the mixed pine forest (mean = 6.49 ± 0.19), suggesting slightly more acidic conditions (

Figure 4). Organic matter content was significantly higher in the pure pine forest (2.08 ± 0.28%) than in the mixed pine forest (1.58 ± 0.17%). In contrast, bulk density was lower in the pure stand (1.25 ± 0.05 g/cm³) compared to the mixed stand (1.35 ± 0.04 g/cm³), indicating better soil porosity and structure in areas where regeneration was denser.

4. Discussion

This study confirms that in Aleppo pine-dominated forests, post-fire vegetation dynamics typically do not favor the establishment of new species. Instead, they initiate ecological processes such as auto-succession [

33], which lead to a gradual return to the pre-fire community composition. These dynamics are consistent with findings from previous studies [

34,

35] and align with the “initial floristic composition” model, whereby pre-fire species dominate and perpetuate self-succession.

Our results showed higher post-fire regeneration density in the p pine forest. This pattern appears to be closely linked to the presence of fallen deadwood. Deadwood likely played a facilitative role by enhancing microclimatic conditions favourable to natural regeneration. It acted as a source of biomass, slowly releasing nutrients, and provided a preferential substrate for seedling establishment. Moreover, the necromass itself may have helped mitigate water stress by offering shade, thereby increasing seedling survival rates [

23,

24,

36].

Conversely, trees removal (salvage logging), currently one of the most widespread post-fire interventions, can significantly hinder natural regeneration [

37]. In our study area, dead trees were left on the ground, and this did not negatively impact post-fire regeneration; on the contrary, seedling density was particularly high in the pure pine stand, reaching approximately 33 seedlings per m². In a similar case in Apulia (Southern Italy), Maiullari et al. [

38] reported that six years after fire, seedling density was significantly higher in areas where deadwood removal was delayed (16 months post-fire) compared to those where it occurred early (4 months post-fire). Likewise, Parro et al. [

39] found that post-fire clearing of burned areas in a managed

Pinus sylvestris forest in Estonia significantly reduced post-fire regeneration compared to uncleared areas.

These findings suggest that leaving deadwood on site can enhance microhabitat conditions for seedling establishment, while salvage logging may disrupt successional pathways by introducing a secondary disturbance that interacts negatively with the initial fire [

40]. Suprting this, Bujoczek et al. [

41] observed that spruce seedling establishment on deadwood increased with wood decay stage in a subalpine forest. Soil accumulation upstream of logs may also contribute to creating microsites favourable to seedling recruitment [

40,

41,

42].

In recent years, numerous studies have shown that salvage logging following fire can impair natural regeneration, alter successional dynamics, and negatively affect ecosystem processes [

43,

44,

45,

46]. Therefore, unless specific management actions are needed for public safety or infrastructure protection, retaining necromass on-site may be a viable and ecologically beneficial strategy. We propose that the strategic use of deadwood as a facilitator of post-fire regeneration should be considered a key component of sustainable forest management.

The abundant natural regeneration observed in the pure pine forest highlights the dual role of fire as both a destructive force and a catalyst for ecological renewal [

47,

48,

49].

Table 1 indicates that seedling height and collar diameter are inversely related to fire severity, such that seedlings in the mixed forest achieved greater height and collar diameter over time. This trend likely reflects reduced intraspecific competition due to lower seedling density. Our findings align with other studies in Southern Europe [

24,

38] and the mixed conifer forests of the Blue Mountains in Washington State, USA, where Andrus et al. [

50] reported reduced seedling height in areas affected by high-severity fires. While some authors have demonstrated that fire severity directly affects microhabitat conditions and seedling growth [

51], others suggest that seedling size post-fire is influenced by a more complex interplay of factors, including fire intensity, soil characteristics, species traits, climatic variables, and interspecific interactions [

26]. For instance, Bond & Midgley [

52] found that seedling growth was enhanced in areas with large canopy openings (<30% cover), while Tilman [

53] observed that higher biodiversity in low-severity zones increased interspecific competition, resulting in smaller seedlings.

These contrasting observations indicate that seedling development after medium to high-severity fires can vary greatly depending on local biotic and abiotic factors, especially during early successional stages [

24]. Therefore, seedling size and survival in post-fire pine forests are governed by complex interactions between fire severity and environmental conditions. A clear understanding of these ecological processes is essential for designing effective post-disturbance management strategies that enhance resilience in Mediterranean pine ecosystems, together with our ability to mitigate the impacts of future wildfires on these forest systems, especially in a scenario driven by climate change.

The differences observed in soil characteristics between the pure and mixed pine forests may have contributed to the contrasting regeneration dynamics. The higher organic matter content and lower bulk density in the pure pine forest likely created more favourable conditions for seedling establishment, such as improved water retention, nutrient availability, and root penetration capacity. These factors are known to play a critical role in post-fire environments, where early soil recovery and microclimate stabilization strongly influence vegetation resilience [

54,

55,

56].

The slightly more acidic pH in the pure pine forest may reflect higher organic matter decomposition rates and the accumulation of necromass resulting from the absence of salvage logging. This observation aligns with studies showing that coarse woody debris contributes to microsite diversity, enhances soil heterogeneity, and facilitates seedling recruitment by buffering temperature and moisture extremes [

40,

41,

42].

In contrast, the lower organic matter and higher bulk density observed in the mixed pine forest suggest a more compacted soil structure, possibly due to reduced biomass input and the absence of decomposing wood. Additionally, the competitive pressure from fire-resilient grasses such as

Ampelodesma and

Hyparrhenia may have further inhibited seedling establishment. Similar findings have been reported in Mediterranean post-fire environments where aggressive herbaceous regrowth suppresses tree regeneration [

57,

58]. Overall, these soil-related factors appear to mediate post-fire vegetation dynamics and should be considered in the design of post-disturbance management strategies.

Forests affected by wildfires must be managed with great care. Inappropriate interventions can delay recovery, reduce biodiversity, and compromise the resilience of stands to future disturbances. The intensity, severity, and frequency of wildfires are critical determinants of post-fire ecological trajectories. Severe fires may degrade soils [

26], increase erosion rates, and eliminate seed banks, factors that can significantly impede natural regeneration. Lastly, climate change plays an increasingly influential role in post-fire dynamics. Rising temperatures, altered precipitation regimes, and prolonged droughts are changing the timing, frequency, and intensity of wildfires. These shifts pose serious challenges to the regeneration capacity of Mediterranean pine forests, reinforcing the need for adaptive management strategies under a rapidly changing climate.

5. Conclusions

This study provides insights into post-fire regeneration dynamics and soil conditions in Aleppo pine forests of southern Italy, seven years after a high-severity crown fire. The results highlight that natural regeneration can be both abundant and spatially continuous, particularly in pure pine stands where fire severity was higher and deadwood was partially retained. These conditions appeared to favour seedling establishment by improving microclimatic conditions and reducing herbaceous competition.

While seedling density was greater in the pure pine stand, seedlings in the mixed stand exhibited larger biometric dimensions, likely due to lower intra-specific competition. This indicates that fire severity, vegetation composition, and deadwood management strongly influence both regeneration abundance and growth patterns.

Soil analysis further revealed that organic matter content was higher and bulk density lower in the pure pine forest, suggesting more favourable physical conditions for root development and water retention. These findings confirm that soil properties play a non-negligible role in supporting post-fire recovery.

From a management perspective, our results suggest that passive restoration strategies, such as avoiding salvage logging and allowing for natural processes, may effectively promote ecosystem resilience in Mediterranean pine forests. However, the ecological responses vary by stand type and fire severity, underlining the importance of site-specific assessments. Future studies integrating long-term monitoring and functional soil indicators could improve our understanding of post-fire successional pathways, particularly under the pressures of climate change and increasing fire frequency.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.A.M.; methodology, P.A.M.; investigation, P.A.M., S.B., E.E. and M.M.; resources, P.A.M; writing—original draft preparation, P.A.M.; writing—review and editing, P.A.M., S.B., E.E. and M.M.; supervision, P.A.M.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Next Generation EU—Italian NRRP, Mission 4, Component 2, Investment 1.5, call for the creation and strengthening of ‘Innovation Ecosystems’, building ‘Territorial R&D Leaders’ (Directorial Decree n. 2021/3277)—Project Tech4You—Technologies for climate change adaptation and quality of life improvement, n. ECS0000009. This work reflects only the authors’ views and opinions; neither the Ministry for University and Research nor the European Commission can be considered responsible for them.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lange, M.A. Climate Change in the Mediterranean: Environmental Impacts and Extreme Events. IEMed. Mediterranean Yearbook 2020, 2020, 30–45. Available online: https://www.iemed.org/publication/climate-change-in-the-mediterranean-environmental-impacts-and-extreme-events/ (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Salis, M.; Del Giudice, L.; Alcasena-Urdiroz, F.; Jahdi, R.; Arca, B.; Pellizzaro, G.; Scarpa, C.; Duce, P. Assessing Cross-Boundary Wildfire Hazard, Transmission, and Exposure to Communities in the Italy-France Maritime Cooperation Area. Front. For. Glob. Change 2023, 6, 1241378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiot, J.; Cramer, W. Climate Change: The 2015 Paris Agreement Thresholds and Mediterranean Basin Ecosystems. Science 2016, 354, 465–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, M.; Bertolín, C.; Arlanzón, D.; Ortiz, P.; Ortiz, R. Climate Change, Large Fires, and Cultural Landscapes in the Mediterranean Basin: An Analysis in Southern Spain. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, P.M.; Monteiro-Henriques, T.; Guiomar, N.; Loureiro, C.; Barros, A.M.G. Bottom-Up Variables Govern Large-Fire Size in Portugal. Ecosystems 2016, 19, 1362–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, S.M.B.; Bento-Gonçalves, A.; Franca-Rocha, W.; Baptista, G. Assessment of Burned Forest Area Severity and Postfire Regrowth in Chapada Diamantina National Park (Bahia, Brazil) Using dNBR and RdNBR Spectral Indices. Geosciences 2020, 10, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.; Cunill Camprubí, À.; Balaguer-Romano, R.; Coco Megía, C.J.; Castañares, F.; Ruffault, J.; Fernandes, P.M.; Resco de Dios, V. Drivers and Implications of the Extreme 2022 Wildfire Season in Southwest Europe. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 859, 160320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, T.; Fèvre, J.; Carcaillet, F.; Carcaillet, C. For a Few Years More: Reductions in Plant Diversity 70 Years after the Last Fire in Mediterranean Forests. Plant Ecol. 2020, 221, 559–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrhám, J.; Soukupova, J.; Prochazka, P. Wildfires and Tourism in the Mediterranean: Balancing Conservation and Economic Interests. BioResources 2025, 20, 500–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupuy, J.L.; Fargeon, H.; Martin-StPaul, N.; et al. Climate Change Impact on Future Wildfire Danger and Activity in Southern Europe: A Review. Ann. For. Sci. 2020, 77, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Anez, N.; Krasovskiy, A.; Muller, M.; Vacik, H.; Baetens, J.; Hukić, E.; Kapovic Solomun, M.; Atanassova, I.; Glushkova, M.; Bogunović, I.; et al. Current Wildland Fire Patterns and Challenges in Europe: A Synthesis of National Perspectives. Air Soil Water Res. 2021, 14, e117862212110281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miebach, A.; Power, M.J.; Resag, T.R.; Netzel, T.; Colombaroli, D.; Litt, T. Changing Fire Regimes during the First Olive Cultivation in the Mediterranean Basin: New High-Resolution Evidence from the Sea of Galilee, Israel. Glob. Planet. Change 2022, 210, 103774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeley, J.E.; Bond, W.J.; Bradstock, R.A.; Pausas, J.G.; Rundel, P.W. Fire in Mediterranean Ecosystems: Ecology, Evolution and Management; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Molina-Terrén, D.M.; Xanthopoulos, G.; Diakakis, M.; Ribeiro, L.; Caballero, D.; Delogu, G.M.; et al. Analysis of Forest Fire Fatalities in Southern Europe: Spain, Portugal, Greece and Sardinia (Italy). Int. J. Wildland Fire 2019, 28, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forzieri, G.; Girardello, M.; Ceccherini, G.; Spinoni, J.; Feyen, L.; Hartmann, H.; et al. Emergent Vulnerability to Climate-Driven Disturbances in European Forests. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salis, M.; Del Giudice, L.; Alcasena-Urdiroz, F.; Jahdi, R.; Arca, B.; Pellizzaro, G.; Scarpa, C.; Duce, P. Assessing Cross-Boundary Wildfire Hazard, Transmission, and Exposure to Communities in the Italy-France Maritime Cooperation Area. Front. For. Glob. Change 2023, 6, 1241378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galizia, L.F.; Curt, T.; Barbero, R.; Rodrigues, M. Understanding Fire Regimes in Europe. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2022, 31, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San-Miguel-Ayanz, J.; Durrant, T.; Boca, R.; Maianti, P.; Liberta, G.; Oom, D.; et al. Advance Report on Forest Fires in Europe, Middle East and North Africa 2022; EUR 31479 EN, Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2023.

- Sanesi, G.; Lafortezza, R.; Colangelo, G.; Marziliano, P.A.; Davies, C. Root System Investigation in Sclerophyllous Vegetation: An Overview. Ital. J. Agron. 2013, 8, e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salesa, D.; Baeza, M.J.; Santana, V.M. Fire Severity and Prolonged Drought Do Not Interact to Reduce Plant Regeneration Capacity but Alter Community Composition in a Mediterranean Shrubland. Fire Ecol. 2024, 20, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, F.; Ascoli, D.; Safford, H.; Adams, M.A.; Moreno, J.M.; Pereira, J.M.C.; Catry, F.X.; Armesto, J.; Bond, W.; González, M.E.; et al. Wildfire Management in Mediterranean-Type Regions: Paradigm Change Needed. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 011001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cos, J.; Doblas-Reyes, F.; Jury, M.; Marcos, R.; Bretonnière, P.A.; Samsó, M. The Mediterranean Climate Change Hotspot in the CMIP5 and CMIP6 Projections. Earth Syst. Dyn. 2022, 13, 321–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marziliano, P.A.; Lombardi, F.; Cataldo, M.F.; Mercuri, M.; Papandrea, S.F.; Manti, L.M.; Bagnato, S.; Alì, G.; Fusaro, P.; Pantano, P.S.; Scuro, C. Forest Fires: Silvicultural Prevention and Mathematical Models for Predicting Fire Propagation in Southern Italy. Fire 2024, 7, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bombino, G.; D’Agostino, D.; Marziliano, P.A.; Pérez Cutillas, P.; Praticò, S.; Proto, A.R.; Manti, L.M.; Lofaro, G.; Zimbone, S.M. A Nature-Based Approach Using Felled Burnt Logs to Enhance Forest Recovery Post-Fire and Reduce Erosion Phenomena in the Mediterranean Area. Land 2024, 13, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coello, J.; Cortina, J.; Valdecantos, A.; Varela, E. Forest Landscape Restoration Experiences in Southern Europe: Sustainable Techniques for Enhancing Early Tree Performance; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2015; Volume 66. [Google Scholar]

- Romeo, F.; Marziliano, P.A.; Turrión, M.B.; Muscolo, A. Short-Term Effects of Different Fire Severities on Soil Properties and Pinus halepensis Regeneration. J. For. Res. 2020, 31, 1271–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iovino, F.; Nicolaci, A.; Marziliano, P.A.; Pignataro, F.; Sanesi, G. Lessons Learned from the Past: Forestry Initiatives for Effective Carbon Stocking in Southern Italy. Ann. Silvic. Res. 2021, 46, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proto, A.R.; Bernardini, V.; Cataldo, M.F.; Zimbalatti, G. Whole Tree System Evaluation of Thinning a Pine Plantation in Southern Italy. Ann. Silvic. Res. 2020, 45, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Pagter, T.; Lucas-Borja, M.E.; Navidi, M.; Carra, B.G.; Baartman, J.; Zema, D.A. Effects of Wildfire and Post-Fire Salvage Logging on Rainsplash Erosion in a Semi-Arid Pine Forest of Central Eastern Spain. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 329, 117059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. World Reference Base for Soil Resources: International Soil Classification System for Naming Soils and Creating Legends for Soil Maps; World Soil Resources Reports No. 106; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2014.

- Nelson, D.W.; Sommers, L.E. Total Carbon, Organic Carbon, and Organic Matter. In Methods of Soil Analysis. Part 3—Chemical Methods; Sparks, D.L., Ed.; Soil Science Society of America and American Society of Agronomy: Madison, WI, USA, 1996; pp. 961–1010. [CrossRef]

- Blake, G.R.; Hartge, K.H. Bulk Density. In Methods of Soil Analysis. Part 1—Physical and Mineralogical Methods, 2nd ed.; Klute, A., Ed.; American Society of Agronomy and Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 1986; pp. 363–375. [CrossRef]

- Naveh, Z. The Evolutionary Significance of Fire in the Mediterranean Region. Science 1975, 188, 1007–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, B.J.; Holzman, B.A. Divergent Successional Pathways of Stand Development Following Fire in a California Closed-Cone Pine Forest. J. Veg. Sci. 2014, 25, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.B. Does the Initial Floristic Composition Model of Succession Really Work? ” J. Veg. Sci. 2014, 25, 4–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghetti, M.; Colangelo, M.; Ripullone, F.; Rita, A. Ondate di Siccità e Calore, Spunti per una Selvicoltura Adattativa. Forest@-Journal of Silviculture and Forest Ecology 2021, 18, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindenmayer, D.B.; Noss, R.F. Salvage Logging, Ecosystem Processes, and Biodiversity Conservation. Conserv. Biol. 2006, 20, 949–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiullari, G.; Leone, V.; Lovreglio, R. Post-Fire Regeneration in Artificial Stands of Pinus halepensis Miller. L’Italia Forestale e Montana 2005, 6, 287–702. [Google Scholar]

- Parro, K.; Metslaid, M.; Renel, G.; Sims, A.; Stanturf, J.A.; Jõgiste, K.; Köster, K. Impact of Postfire Management on Forest Regeneration in a Managed Hemiboreal Forest, Estonia. Can. J. For. Res. 2015, 45, 1192–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcolin, E.; Marzano, R.; Vitali, A.; Garbarino, M.; Lingua, E. Post-Fire Management Impact on Natural Forest Regeneration through Altered Microsite Conditions. Forests 2019, 10, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujoczek, L.; Bujoczek, M.; Banaś, J.; Zięba, S. Spruce regeneration on woody microsites in a subalpine forest in the western Carpathians. Silva Fenn. 2015, 49, id–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rammig, A.; Fahse, L.; Bebi, P.; Bugmann, H. Wind disturbance in mountain forests: Simulating the impact of management strategies, seed supply, and ungulate browsing on forest succession. For. Ecol. Manag. 2007, 242, 142–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donato, D.C.; Fontaine, J.B.; Campbell, J.L.; Robinson, W.D.; Kauffman, J.B.; Law, B.E. Post-wildfire logging hinders regeneration and increases fire risk. Science 2006, 311, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzano, R.; Garbarino, M.; Marcolin, E.; Pividori, M.; Lingua, E. Deadwood anisotropic facilitation on seedling establishment after a stand-replacing wildfire in Aosta Valley (NW Italy). Ecol. Eng. 2013, 51, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorn, S.; Bässler, C.; Svoboda, M.; Müller, J. Effects of natural disturbances and salvage logging on biodiversity. Lessons from the Bohemian Forest. For. Ecol. Manag. 2017, 388, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leverkus, A.B.; Rey Benayas, J.M.; Castro, J.; Boucher, D.; Brewer, S.; Collins, B.M.; Donato, D.; Fraver, S.; Kishchuk, B.E.; Lee, E.J.; et al. Salvage logging effects on regulating and supporting ecosystem services—A systematic map. Can. J. For. Res. 2018, 48, 983–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloret, F.; et al. Effects of fire on Mediterranean ecosystems: A review. Environ. Manag. 2004, 33, 30–45. [Google Scholar]

- Riba, M.; Retana, J. Fire effects on pine reproductive ecology mediated by vegetation structure. For. Ecol. Manag. 2008, 255, 117–125. [Google Scholar]

- Souza-Alonso, P.; Saiz, G.; García, R.A.; Pauchard, A.; Ferreira, A.; Merino, A. Post-fire ecological restoration in Latin American forest ecosystems: Insights and lessons from the last two decades. For. Ecol. Manag. 2022, 509, 120083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrus, R.A.; Droske, C.A.; Franz, M.C.; Hudak, A.T.; Lentile, L.B.; Lewis, S.A.; Morgan, P.; Robichaud, P.R.; Meddens, A.J.H. Spatial and temporal drivers of post-fire tree establishment and height growth in a managed forest landscape. Fire Ecol. 2022, 18, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeley, J.E.; Fotheringham, C.J.; Baer-Keeley, M. Factors affecting plant diversity during post-fire recovery and succession of Mediterranean-climate shrublands in California, USA. Divers. Distrib. 2005, 11, 525–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, W.J.; Midgley, G.F. Ecology of sprouting in woody plants: The persistence niche. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2001, 16, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilman, D. Community invasibility, recruitment limitation, and grassland biodiversity. Ecology 1997, 78, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Certini, G. Effects of fire on properties of forest soils: A review. Oecologia 2005, 143, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveh, Z. The role of fire in the Mediterranean: Human-environment interactions. In Fire and the Environment; Goldammer, J.G., Moreno, J., Eds.; SPB Academic Publishing: The Hague, The Netherlands, 1994; pp. 163–173.

- Mataix-Solera, J.; et al. Fire effects on soil aggregation: A review. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2009, 92, 141–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trabaud, L. Postfire plant community dynamics in the Mediterranean Basin. In Plant–animal interactions in Mediterranean-type ecosystems; Arianoutsou, M.J., Groves, R.H., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1994; pp. 1–15.

- Retana, J.; et al. Regeneration of Mediterranean pine forests after fire: The role of vegetation structure and competition. For. Ecol. Manag. 2002, 160, 221–231. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).