1. Introduction

Severe asthma is defined by the ERS/ATS (European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society) 2014 consensus as “asthma that requires treatment with high-dose inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) plus a second controller (and/or systemic corticosteroids) to prevent it from becoming uncontrolled, or which remains uncontrolled despite this therapy”. It continues to pose a significant and persistent therapeutic challenge for both patients and healthcare providers, despite the advent of a growing arsenal of targeted biologic therapies designed to address the underlying inflammatory mechanisms of the disease.

Although these biologics—each targeting different arms of type 2 inflammation—have expanded our treatment options considerably, approximately 3 to 5% of the total asthmatic population continues to meet criteria for severe, difficult-to-treat, or uncontrolled asthma.

This is despite adherence to guideline-recommended, high-intensity treatment regimens that include maximum doses of inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs) in combination with long-acting β₂-agonists (LABAs), with or without long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs). Many of them continue to depend on daily oral corticosteroids (OCS), often leading to substantial long-term side effects [

1] and a diminished quality of life.

In response to these challenges, the clinical practice of switching between biologics has become increasingly common in specialized asthma centers [

2,

3], particularly in cases where patients fail to achieve adequate control on a first-line agent like anti-IgE (omalizumab), anti-IL-5 (mepolizumab), or anti-IL-5R (benralizumab) therapies, and are therefore switched to anti-IL-4Rα agents such as dupilumab, which blocks both IL-4 and IL-13 signaling pathways.

This trend has been supported by data from large real-world observational studies, which report switch rates ranging from 15 to 20% in select populations [

4]. Still, despite the growing frequency of these therapeutic shifts, hard data on the outcomes—both in terms of clinical improvement and changes in relevant biomarkers—remains relatively limited [

5].

Among the existing biologics, omalizumab has long held a prominent place in the management of allergic asthma, with its ability to reduce exacerbation rates, improve pulmonary function, and enhance patients quality of life safely and effectively [

6,

7], it has secured its role as a well-established add-on therapy in patients who remain symptomatic despite optimized inhaled therapy [

8].

Current guidelines have emphasized the importance of a personalized, biomarker-driven strategy when initiating or modifying biologic treatment [

9], taking into account factors such as blood eosinophil counts, serum IgE levels, FeNO, and specific allergen sensitivities.

Given the heterogeneity and complexity of type 2 inflammation in asthma, there is a solid clinical rationale for redirecting treatment toward a different immunologic pathway when one approach proves ineffective [

10].

In light of all this, our study set out to evaluate the real-world impact of switching to dupilumab in a cohort of patients with severe asthma who had experienced suboptimal outcomes with a prior biologic. Specifically, we aimed to assess not only symptomatic and functional improvements but also changes in key biomarkers, using retrospective data collected from our Allergology and Clinical Immunology unit.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

This was a retrospective, observational study carried out at the Allergy and Clinical Immunology Unit of Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli-IRCCS between January and June 2025. We used the ERS/ATS international guidelines to define severe asthma, [

11] and followed the STROBE recommendations for reporting observational data.[

12]

Fifteen adults (12 women, 3 men) with uncontrolled severe asthma were included after signing informed consents. All had been on at least 6 months of a previous biologic—benralizumab (n=7), omalizumab (n=4), or mepolizumab (n=4)—without adequate symptom control. The decision to switch to dupilumab was made as part of routine clinical care, based on ongoing symptoms and shared decision-making with patients.

2.2. Data Collection and Outcomes

We reviewed clinical and laboratory data at the time of switch (t₀) and again 12 months later (t₁₂). We looked at the following variables:

Forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV₁ % predicted)

Blood eosinophil counts, total IgE, and eosinophil cationic protein (ECP)

Serum free light chains (kappa and lambda) [

13]

Specific IgE to staphylococcal enterotoxins

Fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) [

14]

All baseline samples were collected at least 8 weeks after the last dose of the previous biologic to avoid overlap effects.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

We reported continuous data as mean ± standard deviation or median with interquartile range, and categorical data as counts and percentages. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to check for normal distribution. Paired t-tests or Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were used to compare data between t₀ and t₁₂. Correlations were assessed using Pearson or Spearman coefficients, depending on distribution. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed with SPSS v25.0.[

15] Agreement statistics followed the Bland & Altman method.[

16]

3. Results

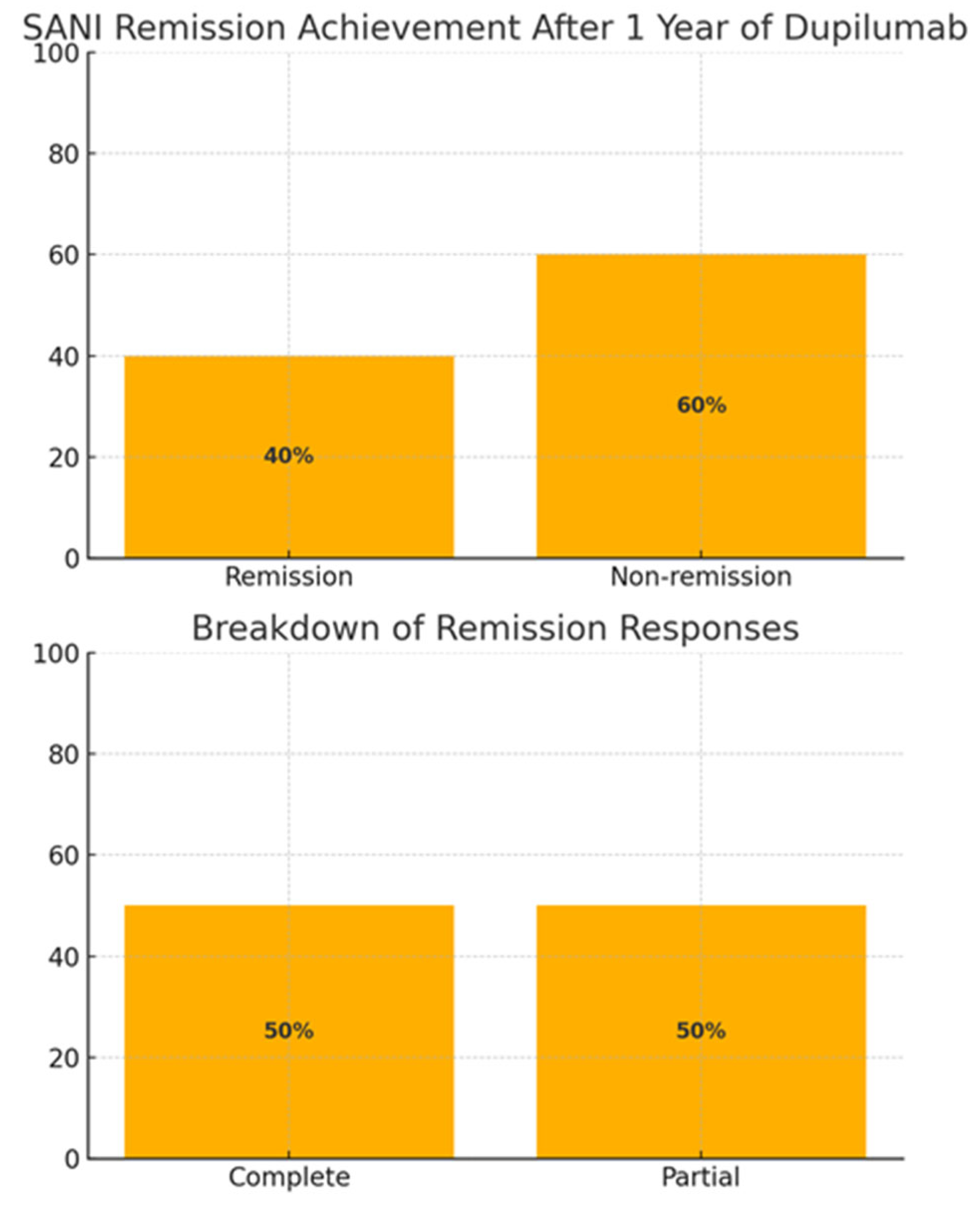

A clinically meaningful response—defined as either a ≥10% gain in FEV₁ or a ≥50% drop in eosinophils—was seen in 6 out of 15 patients (40%), with 3 achieving partial remission, and 3 patients reaching complete remission (according to the SANI definition), as shown in the following image (

Figure 1).

After 12 months of treatment with dupilumab, we observed significant improvements across several key clinical and inflammatory markers. These changes are summarized in

Table 1 and discussed below:

Forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV₁) increased by a mean of 10.8% predicted (p = 0.002), indicating a substantial improvement in lung function.

Fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) levels dropped by an average of 22 parts per billion (ppb) (p = 0.005), suggesting a reduction in airway inflammation.

Peripheral blood eosinophil counts decreased by approximately 400 cells/µL (p = 0.003), consistent with reduced systemic eosinophilic inflammation.

Eosinophil cationic protein (ECP) levels fell by 13 µg/L (p = 0.009), further supporting the anti-inflammatory effects of dupilumab.

Kappa free light chains (FLCs), which have been proposed as novel biomarkers in severe asthma, also showed a significant mean reduction of 2.5 mg/L (p = 0.04).

Taken together, these data reflect a clear biomarker and functional response to dupilumab in this difficult-to-treat cohort. In terms of clinical outcomes, a meaningful response, defined as either a ≥10% gain in FEV₁ or a ≥50% reduction in blood eosinophils, was observed in 6 out of 15 patients (40%). Among these responders, 3 individuals achieved partial remission, while the remaining 3 met the criteria for complete remission, based on the SANI (Severe Asthma Network Italy) definition. These rates are visually summarized in

Figure 1 and are noteworthy, given the previous lack of efficacy with other biologics.

Additionally, we performed correlation analyses to explore the relationships among baseline biomarkers. Blood eosinophil counts were strongly correlated with both ECP (rho = 0.84) and kappa FLCs (rho = 0.81), with p < 0.001 for both associations. Similarly, total IgE levels exhibited a robust correlation with kappa FLCs (rho = 0.80, p < 0.001). These strong correlations reinforce the potential utility of these biomarkers in predicting and monitoring response to treatment.

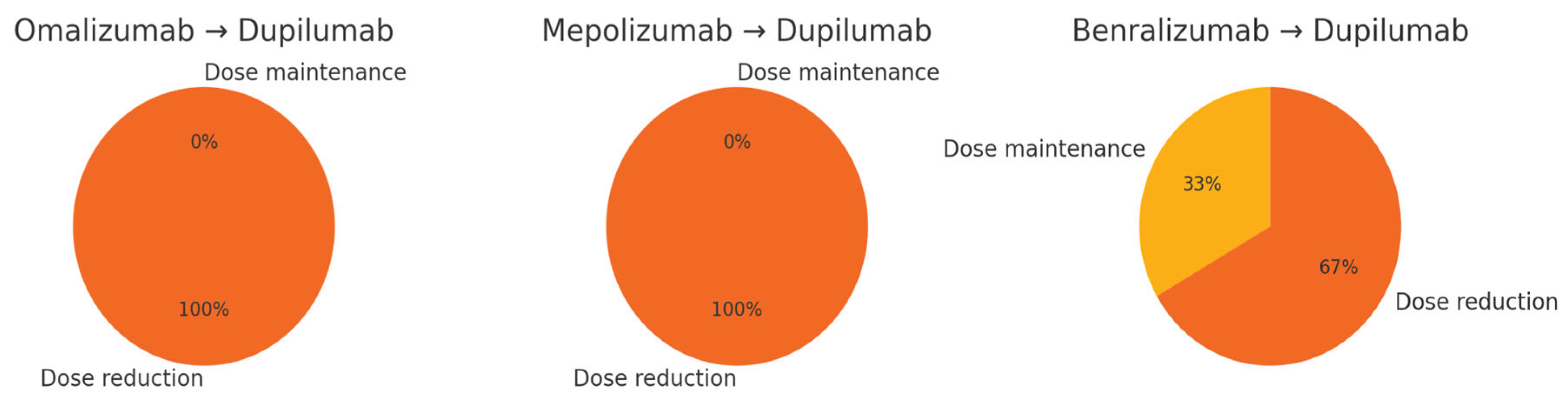

Furthermore, we observed a substantial reduction in oral corticosteroid (OCS) dependency. While specific dose data varied across patients, the majority experienced significant annual reductions in OCS use after switching to dupilumab. This finding is illustrated in the pie charts in

Figure 2 and suggests a meaningful shift toward steroid-sparing outcomes—a particularly relevant benefit given the known long-term adverse effects of OCS-dependency.

4. Discussion

Our findings align closely with those reported in major clinical trials investigating dupilumab for the treatment of type 2 severe asthma, which have consistently demonstrated significant improvements in lung function (as measured by forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV₁)), alongside a marked reduction in oral corticosteroids dependency [

17,

18]. A growing body of real-world evidence also supports the effectiveness of dupilumab in patients who have previously received other biologic therapies, such as anti-IgE or anti-IL-5/5R agents [

19,

20,

21,

22]. These studies reflect the complexities of everyday clinical practice and reinforce the notion that therapeutic switching—particularly to a drug with a different mechanism of action—can be a valuable strategy in cases of suboptimal response. In our own clinical experience, the process of switching to dupilumab was conducted safely and effectively without the implementation of a washout period between biologics, as no serious adverse events were observed during the transition [

23]. However, we did observe a few cases of transient eosinophilia in the early phases of treatment, which underscores the importance of ongoing clinical and laboratory monitoring during the switch, especially in patients with high baseline eosinophil counts [

24]. Our data add to the growing recognition that specific biomarkers, such as blood eosinophil levels, fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO), serum IgE, and free light chains (FLCs), are likely valuable predictors for identifying patients who are more likely to respond favorably to dupilumab [

25]. Therefore, including these biomarkers into routine assessment may enable for a more tailored approach to biologic selection and switch effectiveness. Some comparative studies also suggest that biologic treatment with dupilumab might result in fewer exacerbations and lower steroid requirements when compared to other biologic agents targeting IL-5 or IgE [

26,

27,

28]

. It should, however, be noted that previous studies have reported similar improvements when switching from anti-IgE therapies like omalizumab to anti-IL-5 agents such as mepolizumab or benralizumab, further validating this strategy across different biologic classes [

29,

30]. Overall, these findings support a nuanced, stepwise approach to asthma management—one that is guided by biomarkers, tailored to each patient’s inflammatory profile, and thus can yield meaningful clinical improvements even after prior biologic failure.

5. Limitations

This was a small, single-center, retrospective study, so the findings should be interpreted with caution. We can’t draw firm conclusions about cause and effect. Larger prospective trials that stratify patients based on biomarkers will be key to confirming these results.[

31,

32]

6. Conclusions

In this real-world cohort of patients with severe asthma, transitioning to dupilumab after the failure of a prior biologic therapy resulted in clinically meaningful improvements, both in terms of symptom control and biomarker modulation. These findings suggest that a switch to dupilumab can be a valuable therapeutic option in cases of inadequate response to other biologics. Moreover, elevated baseline levels of type 2 inflammatory markers, particularly blood eosinophils, eosinophil cationic protein (ECP), total IgE, and serum free light chains (FLCs), appear to be associated with a more favorable response, highlighting their potential role as predictive tools in guiding individualized treatment strategies.

References

- Lefebvre P, Duh MS, Lafeuille MH, et al. Acute and chronic systemic corticosteroid-related complications in patients with severe asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015, 136, 1488–1495. [CrossRef]

- Dragonieri S, Portacci A, Quaranta VN, Carpagnano GE. Advancing care in severe asthma: the art of switching biologics. Adv Respir Med. 2024, 92, 110–122. [CrossRef]

- Scioscia G, Nolasco S, Campisi R, Quarato CMI, Caruso C, Pelaia C, Portacci A, Crimi C. Switching Biological Therapies in Severe Asthma. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 May 31, 24, 9563. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Menzies-Gow AN, McBrien C, Unni B, et al. Real-world biologic use and switch patterns in severe asthma. J Asthma Allergy. 2022, 15:63-78.

- Politis J, Bardin PG. Switching biological therapies in adults with severe asthma: dilemmas and outcomes. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2022, 19, 1965–1970. [CrossRef]

- Cullell-Young, M., Bayes, M., Leeson, P.A. Omalizumab: Anti-IgE monoclonal antibody E25, E25, humanised anti-IgE MAb, IGE 025, monoclonal antibody E25, Olizumab, Xolair, rhuMAb-E25. BioDrugs 2002, 16, 380–386.

- Bagnasco, D., Canevari, R.F., Del Giacco, S., Ferrucci, S., Pigatto, P., Castelnuovo, P., Marseglia, G.L., Yalcin, A.D., Pelaia, G., Canonica, G.W. Omalizumab and cancer risk: Current evidence in allergic asthma, chronic urticaria, and chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. World Allergy Organ. J. 2022, 15, 100721.

- Busse,W.W., Massanari, M., Kianifard, F., Geba, G.P. Effect of omalizumab on the need for rescue systemic corticosteroid treatment in patients with moderate-to-severe persistent IgE-mediated allergic asthma: A pooled analysis. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2007, 23, 2379–2386. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agache I, Akdis CA, Akdis M, et al. EAACI biologicals guidelines—recommendations for severe asthma. Allergy. 2021, 76, 14–44. [CrossRef]

- Fahy, JV. Type 2 inflammation in asthma—present in most, absent in many. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015, 15, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung KF, Wenzel SE, Brozek JL, et al. International ERS/ATS guidelines on definition, evaluation, and treatment of severe asthma. Eur Respir J. 2014, 43, 343–373. [CrossRef]

- von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The STROBE statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007, 370, 1453–1457.

- Caruso C, Ciasca G, Baglivo I, et al. Immunoglobulin free light chains in severe asthma: a new biomarker? Allergy. 2024, 79, 2414–2422. [CrossRef]

- Ledda AG, Costanzo G, Sambugaro G, et al. Eosinophil cationic protein variation in asthma patients treated with dupilumab. Life (Basel). 2023, 13, 1884.

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics. 5th ed. Sage, 2018.

- Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1995, 346, 307–310.

- Castro M, Corren J, Pavord ID, et al. Dupilumab efficacy and safety in moderate-to-severe uncontrolled asthma. N Engl J Med. 2018, 378, 2486–2496. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabe KF, Nair P, Brusselle G, et al. Dupilumab in glucocorticoid-dependent severe asthma. N Engl J Med. 2018, 378, 2475–2485. [CrossRef]

- Mümmler C, Munker D, Barnikel M, et al. Dupilumab improves control in patients with insufficient outcome during previous antibody therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021, 9, 1177–1185. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campisi R, Crimi C, Nolasco S, et al. Real-world experience with dupilumab in severe asthma: one-year data. J Asthma Allergy. 2021, 14, 575–583. [CrossRef]

- Numata T, Araya J, Miyagawa H, et al. Real-world effectiveness of dupilumab for severe asthma. J Asthma Allergy. 2022, 15, 395–405. [CrossRef]

- Gollinucci C, Visca D, Spanevello A, et al. Dupilumab effectiveness in severe allergic asthma non-responsive to omalizumab. J Pers Med. 2025, 15, 43. [CrossRef]

- Higo H, Ichikawa H, Arakawa Y, et al. Switching to dupilumab from other biologics without a treatment interval in severe asthma. J Clin Med. 2023, 12, 5174.

- Eger K, Pet L, Weersink EJ, Bel EH. Complications after switching from anti-IL-5/5R to dupilumab in corticosteroid-dependent asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021, 9, 2913–2915. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bult L, Thelen JC, Rauh SP, et al. Dupilumab responder types and predicting factors in type 2 severe asthma. Respir Med. 2024, 231, 107720. [CrossRef]

- Bleecker ER, Blaiss MS, Jacob-Nara J, et al. Comparative effectiveness of dupilumab and omalizumab on exacerbations and steroid use. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2024, 154, 1500–1510.

- Kearney C, Sangani R, Shankar D, et al. Comparative effectiveness of mepolizumab, benralizumab, and dupilumab in difficult-to-control asthma. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2024, 21, 866–874. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung CT, Hung YC, Suk CW, et al. Multinational comparative effectiveness of dupilumab versus anti-IL-5/5R in asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2025, Online ahead of print.

- Chapman KR, Albers FC, Chipps BE, et al. Mepolizumab replacing omalizumab in uncontrolled severe eosinophilic asthma. Allergy. 2019, 74, 1716–1726. [CrossRef]

- Magnan A, Bourdin A, Prazma CM, et al. Treatment response with mepolizumab in severe eosinophilic asthma after omalizumab. Allergy. 2016, 71, 1335–1344. [CrossRef]

- Sedgwick, P. Retrospective cohort studies: advantages and disadvantages. BMJ. 2014, 348, g1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, DR. Retrospective studies and chart reviews. Respir Care. 2004, 49, 1171–1174. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).