Submitted:

08 August 2025

Posted:

11 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction:

Conclusions and future directions:

References

- Agbor, L.N.; Elased, K.M.; Walker, M.K. Endothelial cell-specific aryl hydrocarbon receptor knockout mice exhibit hypotension mediated, in part, by an attenuated angiotensin II responsiveness. Biochemical pharmacology 2011, 82, 514–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, A.; Eubig, P.A.; Schantz, S.L. Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a focused overview for children’s environmental health researchers. Environmental health perspectives 2010, 118, 1646–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aliyu, M.H.; Alio, A.P.; Salihu, H.M. To breastfeed or not to breastfeed: a review of the impact of lactational exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) on infants. Journal of Environmental Health 2010, 73, 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Bäcklin, B.M.; Persson, E.; Jones, C.J.; Dantzer, V. Polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) exposure produces placental vascular and trophoblastic lesions in the mink (Mustela vison): a light and electron microscopic study. Apmis 1998, 106, 785–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, K.; Staecker, H. Low Dose Oxidative Stress Induces Mitochondrial Damage in Hair Cells. The Anatomical Record 2012, 295, 1868–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandara, S.B.; Eubig, P.A.; Sadowski, R.N.; Schantz, S.L. Developmental PCB exposure increases audiogenic seizures and decreases glutamic acid decarboxylase in the inferior colliculus. Toxicological Sciences 2016, 149, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, M. Ultrastructural features of the murine cutaneous microvasculature after exposure to polychlorinated biphenyl compounds (PCBs) and benzo-(a)-pyrene (BAP). Virchows Archiv B Cell Pathology Including Molecular Pathology 1983, 42, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, J. Thyroid hormone receptors in brain development and function. Nature clinical practice Endocrinology & metabolism 2007, 3, 249–259. [Google Scholar]

- Beyer, A.; Biziuk, M. Environmental fate and global distribution of polychlorinated biphenyls. Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology Vol 2009, 201, 137–158. [Google Scholar]

- Boucher, O.; Bastien, C.H.; Saint-Amour, D.; Dewailly, É.; Ayotte, P.; Jacobson, J.L.; Jacobson, S.W.; Muckle, G. Prenatal exposure to methylmercury and PCBs affects distinct stages of information processing: an event-related potential study with Inuit children. Neurotoxicology 2010, 31, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boucher, O.; Muckle, G.; Bastien, C.H. Prenatal exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls: a neuropsychologic analysis. Environmental health perspectives 2009, 117, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullert, A.J.; Doorn, J.A.; Stevens, H.E.; Lehmler, H.-J. The effects of polychlorinated biphenyl exposure during adolescence on the nervous system: A comprehensive review. Chemical research in toxicology 2021, 34, 1948–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Gaw, J.; Wong, C.; Chen, C. Levels and gas chromatographic patterns of polychlorinated biphenyls in the blood of patients after PCB poisoning in Taiwan. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol.;(United States), 1980; 25. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.J.; Hsu, C.C. EFFECTS OF PRENATAL EXPOSURE TO PCBs ON THE NEUROLOGICAL FUNCTION OF CHILDREN: A NEUROPSYCHOLOGICAL AND NEUROPHYSIOLOGY STUDY. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 1994, 36, 312–320. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, W.; Eum, S.Y.; Lee, Y.W.; Hennig, B.; Robertson, L.W.; Toborek, M. PCB 104-induced proinflammatory reactions in human vascular endothelial cells: relationship to cancer metastasis and atherogenesis. Toxicological Sciences 2003, 75, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choksi, N.Y.; Kodavanti, P.R.S.; Tilson, H.A.; Booth, R.G. Effects of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) on brain tyrosine hydroxylase activity and dopamine synthesis in rats. Fundamental and Applied Toxicology 1997, 39, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crofton, K.; Kodavanti, P.; Derr-Yellin, E.; Casey, A.; Kehn, L. PCBs, thyroid hormones, and ototoxicity in rats: cross-fostering experiments demonstrate the impact of postnatal lactation exposure. Toxicological Sciences 2000, 57, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

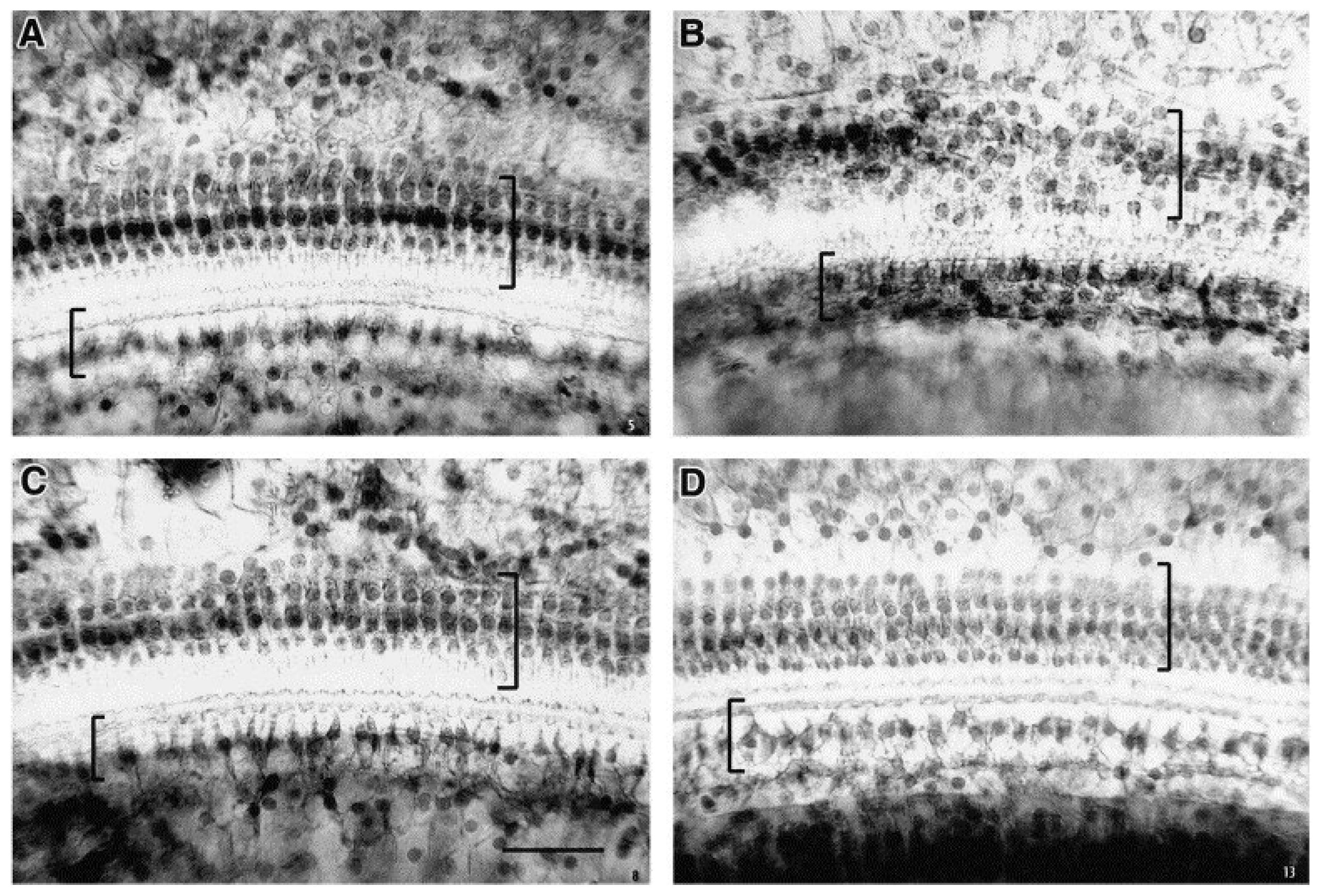

- Crofton, K.M.; Ding, D.-L.; Padich, R.; Taylor, M.; Henderson, D. Hearing loss following exposure during development to polychlorinated biphenyls: a cochlear site of action. Hearing research 2000, 144, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crofton, K.M.; Rice, D.C. Low-frequency hearing loss following perinatal exposure to 3, 3′, 4, 4′, 5-pentachlorobiphenyl (PCB 126) in rats. Neurotoxicology and teratology 1999, 21, 299–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, J.K.; Felty, Q. PCB153-induced overexpression of ID3 contributes to the development of microvascular lesions. PLoS One 2014, 9, e104159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desa, D.E.; Nichols, M.G.; Smith, H.J. Aminoglycosides rapidly inhibit NAD(P)H metabolism increasing reactive oxygen species and cochlear cell demise. J Biomed Opt 2018, 24, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickerson, S.M.; Cunningham, S.L.; Patisaul, H.B.; Woller, M.J.; Gore, A.C. Endocrine disruption of brain sexual differentiation by developmental PCB exposure. Endocrinology 2011, 152, 581–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donahue, D.A.; Dougherty, E.J.; Meserve, L.A. Influence of a combination of two tetrachlorobiphenyl congeners (PCB 47; PCB 77) on thyroid status, choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) activity, and short-and long-term memory in 30-day-old Sprague–Dawley rats. Toxicology 2004, 203, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Shimy, A.A.; Nada, E.; Quriba, A.; Galhoum, D. Assessment of Higher Cognitive Function Using p300 in Children with Specific Language Impairment: Data from Zagazig University Hospital. Zagazig University Medical Journal 2023, 29, 1456–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eubig, P.A.; Aguiar, A.; Schantz, S.L. Lead and PCBs as risk factors for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Environmental health perspectives 2010, 118, 1654–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faingold, C.L. Role of GABA abnormalities in the inferior colliculus pathophysiology–audiogenic seizures. Hearing research 2002, 168, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahvar, A.; Darwish, N.H.; Sladek, S.; Meisami, E. Marked recovery of functional metabolic activity and laminar volumes in the rat hippocampus and dentate gyrus following postnatal hypothyroid growth retardation: a quantitative cytochrome oxidase study. Experimental neurology 2007, 204, 556–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrest, D.; Erway, L.C.; Ng, L.; Altschuler, R.; Curran, T. Thyroid hormone receptor β is essential for development of auditory function. Nature genetics 1996, 13, 354–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Cairasco, N. A critical review on the participation of inferior colliculus in acoustic-motor and acoustic-limbic networks involved in the expression of acute and kindled audiogenic seizures. Hearing Research 2002, 168, 208–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldey, E.S.; Crofton, K.M. Thyroxine replacement attenuates hypothyroxinemia, hearing loss, and motor deficits following developmental exposure to Aroclor 1254 in rats. Toxicological Sciences 1998, 45, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Goldey, E.S.; Kehn, L.S.; Lau, C.; Rehnberg, G.L.; Crofton, K.M. Developmental exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls (Aroclor 1254) reduces circulating thyroid hormone concentrations and causes hearing deficits in rats. Toxicology and applied pharmacology 1995, 135, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grandjean, P.; Weihe, P.; Burse, V.W.; Needham, L.L.; Storr-Hansen, E.; Heinzow, B.; Debes, F.; Murata, K.; Simonsen, H.; Ellefsen, P. Neurobehavioral deficits associated with PCB in 7-year-old children prenatally exposed to seafood neurotoxicants. Neurotoxicology and teratology 2001, 23, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, L.; Slapnick, S.; Kennedy, H.; Hackney, C. Ryanodine receptor localisation in the mammalian cochlea: an ultrastructural study. Hearing research 2006, 219, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra-Ojeda, S.; Suarez, A.; Valls, A.; Verdu, D.; Pereda, J.; Ortiz-Zapater, E.; Carretero, J.; Mauricio, M.D.; Serna, E. The role of aryl hydrocarbon receptor in the endothelium: a systematic review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 13537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Prasad, A.; Singh, R.; Gupta, G. Auditory and visual P300 responses in early cognitive assessment of children and adolescents with epilepsy. Journal of pediatric neurosciences 2020, 15, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, D.; Bielefeld, E.C.; Harris, K.C.; Hu, B.H. The role of oxidative stress in noise-induced hearing loss. Ear and hearing 2006, 27, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henry, K.R. Auditory brainstem volume-conducted responses: origins in the laboratory mouse. Ear and Hearing 1979, 4, 173–178. [Google Scholar]

- Hens, B.; Hens, L. Persistent Threats by Persistent Pollutants: Chemical Nature, Concerns and Future Policy Regarding PCBs-What Are We Heading For? Toxics 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrick, R.F.; Meeker, J.D.; Altshul, L. Serum PCB levels and congener profiles among teachers in PCB-containing schools: a pilot study. Environmental Health 2011, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holcomb, P.J.; Ackerman, P.T.; Dykman, R.A. Auditory event-related potentials in attention and reading disabled boys. International Journal of Psychophysiology 1986, 3, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, A.S.; Fitzpatrick, R.; Pessah, I.; Kostyniak, P.; Lein, P.J. Polychlorinated biphenyls induce caspase-dependent cell death in cultured embryonic rat hippocampal but not cortical neurons via activation of the ryanodine receptor. Toxicology and applied pharmacology 2003, 190, 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, B.A.; Llano, D.A. Aging and central auditory disinhibition: is it a reflection of homeostatic downregulation or metabolic vulnerability? Brain Sciences 2019, 9, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

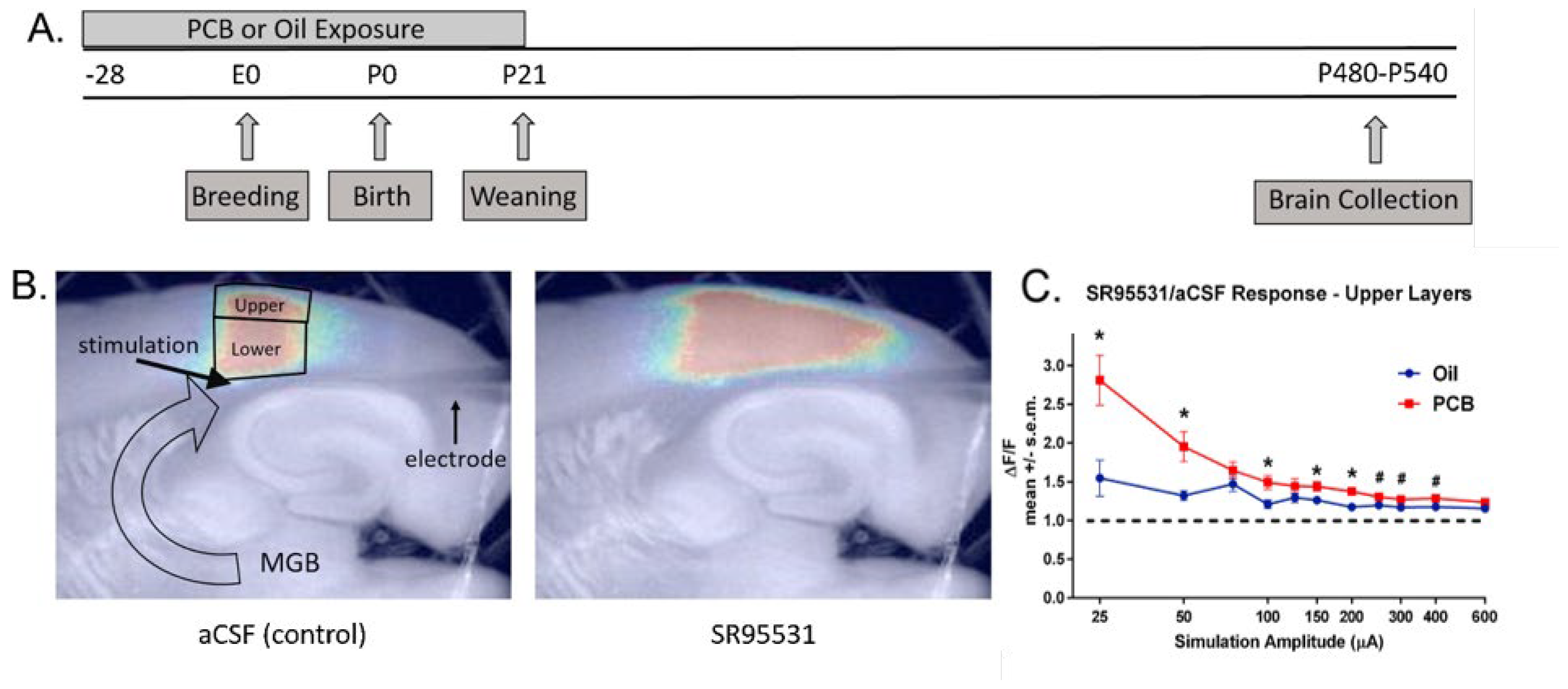

- Ibrahim, B.A.; Louie, J.J.; Shinagawa, Y.; Xiao, G.; Asilador, A.R.; Sable, H.J.; Schantz, S.L.; Llano, D.A. Developmental exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls prevents recovery from noise-induced hearing loss and disrupts the functional organization of the inferior colliculus. Journal of Neuroscience 2023, 43, 4580–4597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imamoglu, I.; Christensen, E.R. PCB sources, transformations, and contributions in recent Fox River, Wisconsin sediments determined from receptor modeling. Water Research 2002, 36, 3449–3462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, J.L.; Jacobson, S.W. Intellectual impairment in children exposed to polychlorinated biphenyls in utero. New England Journal of Medicine 1996, 335, 783–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, J.; Wahlang, B.; Shi, H.; Hardesty, J.E.; Falkner, K.C.; Head, K.Z.; Srivastava, S.; Merchant, M.L.; Rai, S.N.; Cave, M.C.; Prough, R.A. Dioxin-like and non-dioxin-like PCBs differentially regulate the hepatic proteome and modify diet-induced nonalcoholic fatty liver disease severity. Med Chem Res 2020, 29, 1247–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jursa, S.; Chovancová; J; Petrík, J. ; Lokša, J. Dioxin-like and non-dioxin-like PCBs in human serum of Slovak population. Chemosphere 2006, 64, 686–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jusko, T.A.; Sisto, R.; Iosif, A.-M.; Moleti, A.; Wimmerová, S; Lancz, K. ; Tihányi, J.; Šovčiková, E; Drobná, B; Palkovičová, L. Prenatal and postnatal serum PCB concentrations and cochlear function in children at 45 months of age. Environmental health perspectives 2014, 122, 1246–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenet, T.; Froemke, R.C.; Schreiner, C.E.; Pessah, I.N.; Merzenich, M.M. Perinatal exposure to a noncoplanar polychlorinated biphenyl alters tonotopy, receptive fields, and plasticity in rat primary auditory cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007, 104, 7646–7651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, E.; Tohyama, C. Embryonic and postnatal expression of aryl hydrocarbon receptor mRNA in mouse brain. Frontiers in neuroanatomy 2017, 11, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knipper, M.; Zinn, C.; Maier, H.; Praetorius, M.; Rohbock, K.; Köpschall, I.; Zimmermann, U. Thyroid hormone deficiency before the onset of hearing causes irreversible damage to peripheral and central auditory systems. Journal of Neurophysiology 2000, 83, 3101–3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopke, R.; Bielefeld, E.; Liu, J.; Zheng, J.; Jackson, R.; Henderson, D.; Coleman, J.K. Prevention of impulse noise-induced hearing loss with antioxidants. Acta oto-laryngologica 2005, 125, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuratsune, M.; Yoshimura, T.; Matsuzaka, J.; Yamaguchi, A. Epidemiologic study on Yusho, a poisoning caused by ingestion of rice oil contaminated with a commercial brand of polychlorinated biphenyls. Environmental Health Perspectives 1972, 1, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasky, R.E.; Widholm, J.J.; Crofton, K.M.; Schantz, S.L. Perinatal exposure to Aroclor 1254 impairs distortion product otoacoustic emissions (DPOAEs) in rats. Toxicological sciences 2002, 68, 458–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.M.; Sadowski, R.N.; Schantz, S.L.; Llano, D.A. Developmental PCB exposure disrupts synaptic transmission and connectivity in the rat auditory cortex, independent of its effects on peripheral hearing threshold. Eneuro 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Huang, L.; Yang, J. Differential expression of ryanodine receptor in the developing rat cochlea. European Journal of Histochemistry: EJH 2009, 53, e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilienthal, H.; Hack, A.; Roth-Härer, A.; Grande, S.W.; Talsness, C.E. Effects of developmental exposure to 2, 2′, 4, 4′, 5-pentabromodiphenyl ether (PBDE-99) on sex steroids, sexual development, and sexually dimorphic behavior in rats. Environmental health perspectives 2006, 114, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lilienthal, H.; Heikkinen, P.; Andersson, P.L.; van der Ven, L.T.; Viluksela, M. Auditory effects of developmental exposure to purity-controlled polychlorinated biphenyls (PCB52 and PCB180) in rats. Toxicological Sciences 2011, 122, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Little, C.C.; Barlow, J.; Alsen, M.; van Gerwen, M. Association between polychlorinated biphenyl exposure and thyroid hormones: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Environ Sci Health C Toxicol Carcinog 2022, 40, 248–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Tan, Y.; Song, E.; Song, Y. A critical review of polychlorinated biphenyls metabolism, metabolites, and their correlation with oxidative stress. Chemical research in toxicology 2020, 33, 2022–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyall, K.; Croen, L.A.; Sjödin, A.; Yoshida, C.K.; Zerbo, O.; Kharrazi, M.; Windham, G.C. Polychlorinated biphenyl and organochlorine pesticide concentrations in maternal mid-pregnancy serum samples: association with autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability. Environmental health perspectives 2017, 125, 474–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marek, R.F.; Thorne, P.S.; Herkert, N.J.; Awad, A.M.; Hornbuckle, K.C. Airborne PCBs and OH-PCBs inside and outside urban and rural US schools. Environmental science & technology 2017, 51, 7853–7860. [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz, G. From Industrial Toxins to Worldwide Pollutants: A Brief History of Polychlorinated Biphenyls. Public Health Rep 2018, 133, 721–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meerts, I.A.; Lilienthal, H.; Hoving, S.; Van Den Berg, J.H.; Weijers, B.M.; Bergman, Å.; Koeman, J.H.; Brouwer, A. Developmental exposure to 4-hydroxy-2, 3, 3′, 4′, 5-pentachlorobiphenyl (4-OH-CB107): long-term effects on brain development, behavior, and brain stem auditory evoked potentials in rats. Toxicological sciences 2004, 82, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milbrandt, J.; Holder, T.; Wilson, M.; Salvi, R.; Caspary, D. GAD levels and muscimol binding in rat inferior colliculus following acoustic trauma. Hearing research 2000, 147, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, J.-Y.; Kim, R.; Min, K.-B. Serum polychlorinated biphenyls concentrations and hearing impairment in adults. Chemosphere 2014, 102, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadparast-Tabas, P.; Arab-Zozani, M.; Naseri, K.; Darroudi, M.; Aramjoo, H.; Ahmadian, H.; Ashrafipour, M.; Farkhondeh, T.; Samarghandian, S. Polychlorinated biphenyls and thyroid function: a scoping review. Rev Environ Health 2024, 39, 679–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton-Jones, R.; Cannell, M.; Jeyakumar, L.; Fleischer, S.; Housley, G. Differential expression of ryanodine receptors in the rat cochlea. Neuroscience 2006, 137, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- N, V.C.S. , M, L., P, S. Impact of combined developmental PCB and noise exposure on the cerebral microvasculature in mouse. 2024.

- Nakagawa, K.; Itoya, M.; Takemoto, N.; Matsuura, Y.; Tawa, M.; Matsumura, Y.; Ohkita, M. Indoxyl sulfate induces ROS production via the aryl hydrocarbon receptor-NADPH oxidase pathway and inactivates NO in vascular tissues. Life Sciences 2021, 265, 118807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, L.; Kelley, M.W.; Forrest, D. Making sense with thyroid hormone—the role of T3 in auditory development. Nature Reviews Endocrinology 2013, 9, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panesar, H.K.; Kennedy, C.L.; Keil Stietz, K.P.; Lein, P.J. Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs): risk factors for autism spectrum disorder? Toxics 2020, 8, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patandin, S.; Lanting, C.I.; Mulder, P.G.H.; Boersma, E.R.; Sauer, P.J.J.; Weisglas-Kuperus, N. Effects of environmental exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls and dioxins on cognitive abilities in Dutch children at 42 months of age. The Journal of Pediatrics 1999, 134, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellacani, C.; Tagliaferri, S.; Caglieri, A.; Goldoni, M.; Giordano, G.; Mutti, A.; Costa, L.G. Synergistic interactions between PBDEs and PCBs in human neuroblastoma cells. Environmental Toxicology 2014, 29, 418–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peper, J.S.; Koolschijn, P.C.M. Sex steroids and the organization of the human brain. Journal of Neuroscience 2012, 32, 6745–6746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, J.T.; Petriello, M.C.; Newsome, B.J.; Hennig, B. Polychlorinated biphenyls and links to cardiovascular disease. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2016, 23, 2160–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, J.T.; Petriello, M.C.; Newsome, B.J.; Hennig, B. Polychlorinated biphenyls and links to cardiovascular disease. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2016, 23, 2160–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, S.L.; Curran, M.A.; Marconi, S.A.; Carpenter, C.D.; Lubbers, L.S.; McAbee, M.D. Distribution of mRNAs encoding the arylhydrocarbon receptor, arylhydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator, and arylhydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator-2 in the rat brain and brainstem. Journal of Comparative Neurology 2000, 427, 428–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petriello, M.C.; Brandon, J.A.; Hoffman, J.; Wang, C.; Tripathi, H.; Abdel-Latif, A.; Ye, X.; Li, X.; Yang, L.; Lee, E. Dioxin-like PCB 126 increases systemic inflammation and accelerates atherosclerosis in lean LDL receptor-deficient mice. Toxicological Sciences 2018, 162, 548–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisani, A.; Paciello, F.; Montuoro, R.; Rolesi, R.; Galli, J.; Fetoni, A.R. Antioxidant therapy as an effective strategy against noise-induced hearing loss: From experimental models to clinic. Life 2023, 13, 1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, E.; Bandara, S.B.; Allen, J.B.; Sadowski, R.N.; Schantz, S.L. Developmental PCB exposure increases susceptibility to audiogenic seizures in adulthood. NeuroToxicology 2015, 46, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, E.; Powers, B.E.; McAlonan, R.M.; Ferguson, D.C.; Schantz, S.L. Effects of developmental exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls and/or polybrominated diphenyl ethers on cochlear function. Toxicological Sciences 2011, 124, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porte, C.; Albaigés, J. Bioaccumulation patterns of hydrocarbons and polychlorinated biphenyls in bivalves, crustaceans, and fishes. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 1994, 26, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, B.E.; Poon, E.; Sable, H.J.; Schantz, S.L. Developmental exposure to PCBs, MeHg, or both: long-term effects on auditory function. Environmental health perspectives 2009, 117, 1101–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, B.E.; Widholm, J.J.; Lasky, R.E.; Schantz, S.L. Auditory deficits in rats exposed to an environmental PCB mixture during development. Toxicological Sciences 2006, 89, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, M.; Gao, Z.; Qiu, Y.; Wang, R.; Tian, K.; Yue, B.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, P.; Wu, Z.; Zhu, Q. NOX2 Contributes to High-Frequency Outer Hair Cell Vulnerability in the Cochlea. Advanced Science 2025, e08830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramkumar, V.; Mukherjea, D.; Dhukhwa, A.; Rybak, L.P. Oxidative Stress and Inflammation Caused by Cisplatin Ototoxicity. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribak, C.E.; Morin, C.L. The role of the inferior colliculus in a genetic model of audiogenic seizures. Anatomy and embryology 1995, 191, 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roegge, C.S.; Morris, J.R.; Villareal, S.; Wang, V.C.; Powers, B.E.; Klintsova, A.Y.; Greenough, W.T.; Pessah, I.N.; Schantz, S.L. Purkinje cell and cerebellar effects following developmental exposure to PCBs and/or MeHg. Neurotoxicology and teratology 2006, 28, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roegge, C.S.; Wang, V.C.; Powers, B.E.; Klintsova, A.Y.; Villareal, S.; Greenough, W.T.; Schantz, S.L. Motor impairment in rats exposed to PCBs and methylmercury during early development. Toxicol Sci 2004, 77, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogan, W.J.; Gladen, B.C.; McKinney, J.D.; Carreras, N.; Hardy, P.; Thullen, J.; Tingelstad, J.; Tully, M. Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and dichlorodiphenyl dichloroethene (DDE) in human milk: effects of maternal factors and previous lactation. American journal of public health 1986, 76, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogan, W.J.; Gladen, B.C.; McKinney, J.D.; Carreras, N.; Hardy, P.; Thullen, J.; Tinglestad, J.; Tully, M. Neonatal effects of transplacental exposure to PCBs and DDE. The Journal of pediatrics 1986, 109, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, J.A.; Salvi, R. Ototoxicity of divalent metals. Neurotoxicity research 2016, 30, 268–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowand, C. How old are America's public schools. Education Statistics Quarterly 1999, 1, 53–56. [Google Scholar]

- Sadowski, R.N.; Stebbings, K.A.; Slater, B.J.; Bandara, S.B.; Llano, D.A.; Schantz, S.L. Developmental exposure to PCBs alters the activation of the auditory cortex in response to GABAA antagonism. Neurotoxicology 2016, 56, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagiv, S.K.; Thurston, S.W.; Bellinger, D.C.; Altshul, L.M.; Korrick, S.A. Neuropsychological measures of attention and impulse control among 8-year-old children exposed prenatally to organochlorines. Environ Health Perspect 2012, 120, 904–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selvakumar, K.; Prabha, R.L.; Saranya, K.; Bavithra, S.; Krishnamoorthy, G.; Arunakaran, J. Polychlorinated biphenyls impair blood–brain barrier integrity via disruption of tight junction proteins in cerebrum, cerebellum and hippocampus of female Wistar rats: neuropotential role of quercetin. Human & experimental toxicology 2013, 32, 706–720. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, R.K.; Chern, A.; Golub, J.S.; Lalwani, A.K. Subclinical hearing loss and educational performance in children: A national study. Frontiers in Audiology and Otology 2023, 1, 1214188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Robertson, L.W.; Ludewig, G. Regulatory effects of dioxin-like and non-dioxin-like PCBs and other AhR ligands on the antioxidant enzymes paraoxonase 1/2/3. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2016, 23, 2108–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Carthew, P.; Clothier, B.; Constantin, D.; Francis, J.; Madra, S. Synergy of iron in the toxicity and carcinogenicity of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and related chemicals. Toxicology letters 1995, 82, 945–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, M.; Sun, J.; Liu, S.; Zhu, Y.; Ren, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, X.; Yang, W.; Li, G.; Wang, X.; Zheng, W.; Zhang, J.; Yang, J. An event-related potential study of P300 in preschool children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Front Pediatr 2024, 12, 1461921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, K. 2012. Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in school buildings: sources, environmental levels, and exposures. US Environmental Protection Agency, National Exposure Research Laboratory ….

- Trnovec, T.; Šovčíková; E; Hust’ák, M. ; Wimmerová; S; Kočan, A.; Jurečková; D; Langer, P.; Palkovičová; Lu, D.r.o.b.n.á.; B Exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls and hearing impairment in children. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology 2008, 25, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuji, M. , Aiko, Y., Kawamoto, T., Hachisuga, T., Kooriyama, C., Myoga, M., Tomonaga, C., Matsumura, F., Anan, A., Tanaka, M., Yu, H.S., Fujisawa, Y., Suga, R., Shibata, E., 2013. Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) decrease the placental syncytiotrophoblast volume and increase Placental Growth Factor (PlGF) in the placenta of normal pregnancy. Placenta 34. [CrossRef]

- Vreugdenhil, H.; Van Zanten, G.; Brocaar, M.; Mulder, P.G.; Weisglas-Kuperus, N. Prenatal exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls and breastfeeding: opposing effects on auditory P300 latencies in 9-year-old Dutch children. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology 2004, 46, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Feng, S.; Bai, H.; Zeng, P.; Chen, F.; Wu, C.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Ye, Q. Polychlorinated biphenyl quinone induces endothelial barrier dysregulation by setting the cross talk between VE-cadherin, focal adhesion, and MAPK signaling. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 2015, 308, H1205–H1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Sargis, R.M.; Volden, P.A.; Carmean, C.M.; Sun, X.J.; Brady, M.J. PCB 126 and other dioxin-like PCBs specifically suppress hepatic PEPCK expression via the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. PloS one 2012, 7, e37103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).