1. Introduction

Coffee is a globally significant commodity of commercial, cultural, and historical importance, particularly for Brazil, its leading producer and exporter. Meeting the growing demand for coffee through sustainable production presents challenges [

1], with productivity depending on a complex interplay of factors, especially agricultural management practices. In this context, spraying plays a critical role, being influenced by plant protection needs, plant size, and pest dynamics, all of which affect application efficiency.

Although advanced spraying techniques for perennial crops are available [

2,

3], low-tech equipment, such as sack, stationary hydraulic, pneumatic, and hydro-pneumatic sprayers, remain prevalent in Brazilian coffee farming. High-tech sprayers are not widely adopted for tree crops as yet, reflecting the reality of coffee cultivation in Brazil’s Cerrado region. Therefore, optimizing operating conditions—including appropriate nozzle selection, application rates, working speeds, regulation, and calibration—is essential for efficient spraying [

4].

Air-assisted sprayers are the most commonly used sprayers for coffee cultivation in areas with mechanization-friendly topography. Currently, several models are available, with radial and axial fans being the most common for tree crops. In coffee farming, axial fans dominate, producing large volumes of turbulent air at relatively low static pressures. These fans offer limited adjustment of airflow patterns and vertical spray distribution, allowing variability in nozzle type and number, but not their positioning [

5,

6,

7].

Hydro-pneumatic sprayers with axial fans distribute a portion of droplets and airflow into the environment, extending beyond the target canopy. A tunnel-type turbo-pneumatic sprayer with a reduced drift risk has been designed for more precise spraying [

8,

9]. Preciseness was achieved by surrounding the target lines with air outlets from one or more radial fans, or multiple tangential or direct axial fans, adjustable for air angles and fan positions. Recycling tunnel sprayers have enhanced uniformity and foliar deposition, while reducing pesticide consumption, drift, and soil loss compared to traditional non-tunnel sprayers [

2]. However, these systems are costly and best suited for flat areas or uniform orchards.

When sprayer adjustments and calibration are not aligned with the target, they can result in uneven application, loss of spray to the ground, drift, and droplet evaporation [

10]. In perennial crops, droplets are directed by airflow across the canopy and upward, leading to both horizontal drift across the canopy as well as vertical drift above the canopy and into the atmosphere. Therefore, minimizing pesticide loss, under-application, over-application, and off-target coverage and deposition is crucial. These measures would help to preserve environmental and human health, and ensure food safety [

7,

11]. The performance of hydro-pneumatic sprayers depends on the airflow requirements of the tree canopy. Therefore, the air delivery rate of sprayers must be appropriately regulated. However, field testing of these sprayers requires considerable effort, time, and expensive instruments to accurately measure airflow rates [

12,

13].

Spray studies to address the variability in spray behaviours and air velocity profiles within and around crop canopies are yet unknown. Few growers understand how to select and configure sprayers to address issues related to spray penetration and improve canopy depth deposition [

14] without over spraying beyond the canopy. The insufficient knowledge and limited training of growers often results in air-blast sprayers depositing only a fraction of the product on the intended target, with 30–50% loss to non-target areas [

15,

16].

The objective of air-assisted applications lies in directing a droplet-laden air stream towards the canopy for deposition on the target. Insufficient flow results in poor penetration into the canopy, leading to inadequate deposition and reduced effectiveness of the control. In contrast, excessive airflow propels droplets beyond the intended range, causing soil and environmental losses and compromising application uniformity and target coverage [

6,

17]. Thus, restricting droplet distribution within the designated application range is crucial.

Studies have examined factors influencing foliar deposition or retention, such as nozzle type, application rates, and the use of adjuvants, with a focus on reducing drift. Standard flat jet nozzles offer lower drift potential, and a more uniform deposition compared to hollow conical jet nozzles [

18,

19,

20]. In perennial crops, hollow conical nozzles are commonly used at high pressures, generating fine droplets that are more prone to loss [

21]. Therefore, further investigations into the use of flat-jet nozzles is warranted [

22].

Studies in application technology have focused on operational optimization, aiming to enhance application efficiency and effectiveness and covering aspects such as product deposition on the target, droplet spectrum, control effectiveness, and losses to the soil and environment. However, studies on the assessment of droplet deposition on leaves adjacent to the application band are unknown. This phenomenon, referred to as ‘transfer’ in this study, represents an induced and ‘accepted’ drift in the field, which may lead to the selection of resistant biotic pests and pathogens in coffee crops. Therefore, this study aimed to address this gap by quantifying the drift, represented by the deposition of a tracer on adjacent leaves, caused by varying application rates and hydraulic nozzles with different jet types.

The quantification of carry-over, as demonstrated in this study, could drive substantial advancements in the hydropneumatic sprayer industry. These advancements would focus on developing machines and strategies that improve the targeting and retention of plant protection products on the intended canopy, thereby reducing drift losses. While applications can be optimized from both technical and environmental perspectives, the use of appropriate machinery remains crucial for ensuring effective application technology.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was conducted on the Jataí property (18°53'04.82" S, 47°21'09.15" W), located at an altitude of 972 m, in the municipality of Monte Carmelo-MG, Brazil, in February 2023. The region’s climate is classified as Cwa (warm and humid with a dry winter) according to the Köppen-Geiger classification [

23]. Laboratory analyses were carried out at the Centre of Excellence in Agricultural Mechanisation, affiliated with the Institute of Agricultural Sciences at the Federal University of Uberlândia, Brazil.

The trial was conducted in a six-year-old coffee plantation of Mundo Novo cultivar, with a plant spacing of 3.8 × 0.6 m. The plants were in the fruit-filling stage, with an average height of 2.75 m, a crown diameter of 1.64 m, and a vegetation volume of 11,868 m ha-1, calculated using the methodology adapted from [

24]. Each experimental unit (1,260 m²) used for treatment applications comprised ten 40-m-long planting rows. A central 20-m section of two planting rows was designated as the effective area, with 10-m sections at both ends acting as borders.

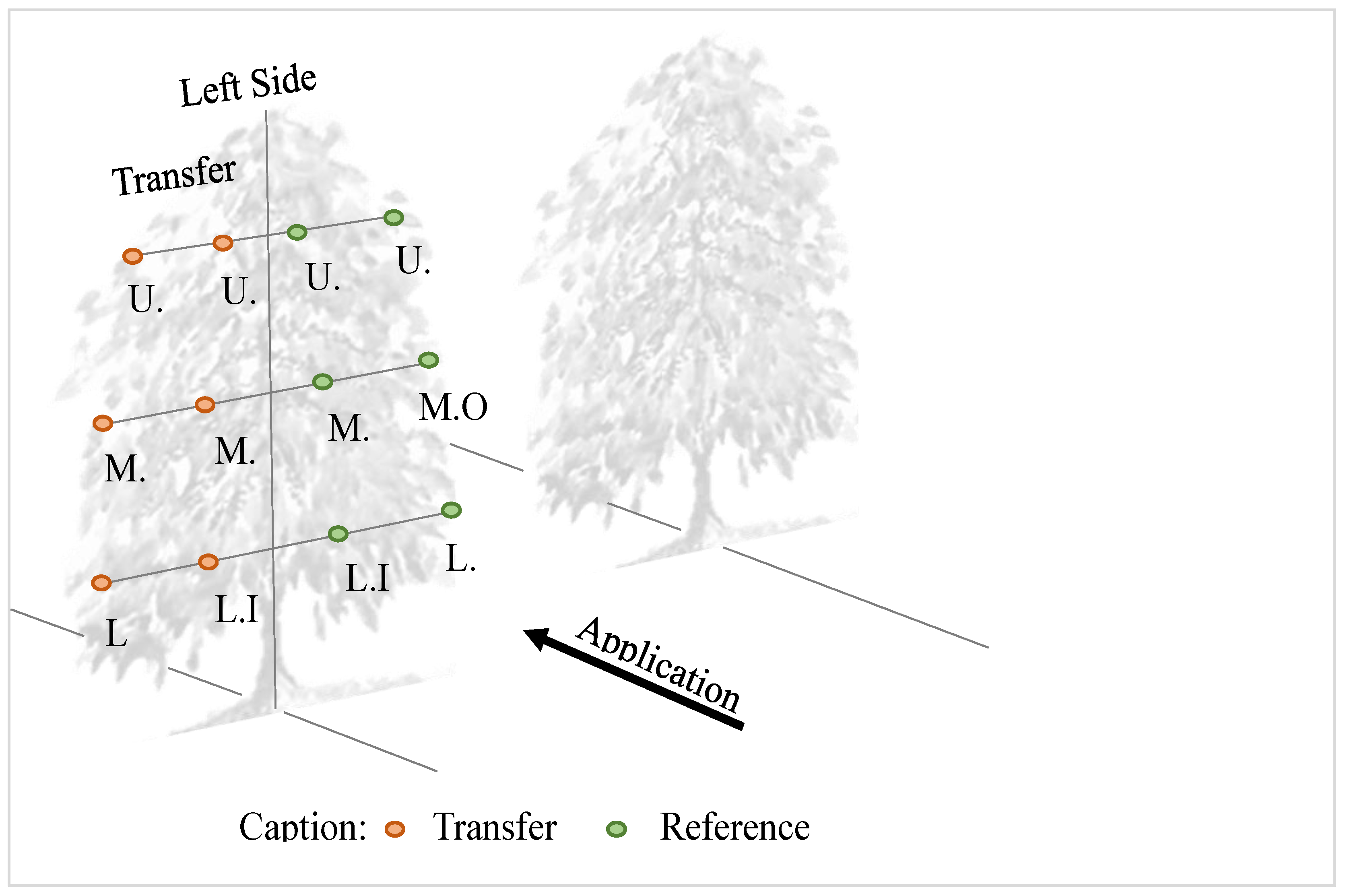

The experiment was carried out in a hierarchical design (3 × 2 × 2 × 3 × 3 × 2), with four replicates. The factors included three application rates (200, 400, and 600 Lha-1) and two different jet types (conical and standard flat), considering the evaluation on two application sides of the sprayer (left and right), plant sections (upper, middle, and lower), and positions on the plagiotropic branch (inner and outer).

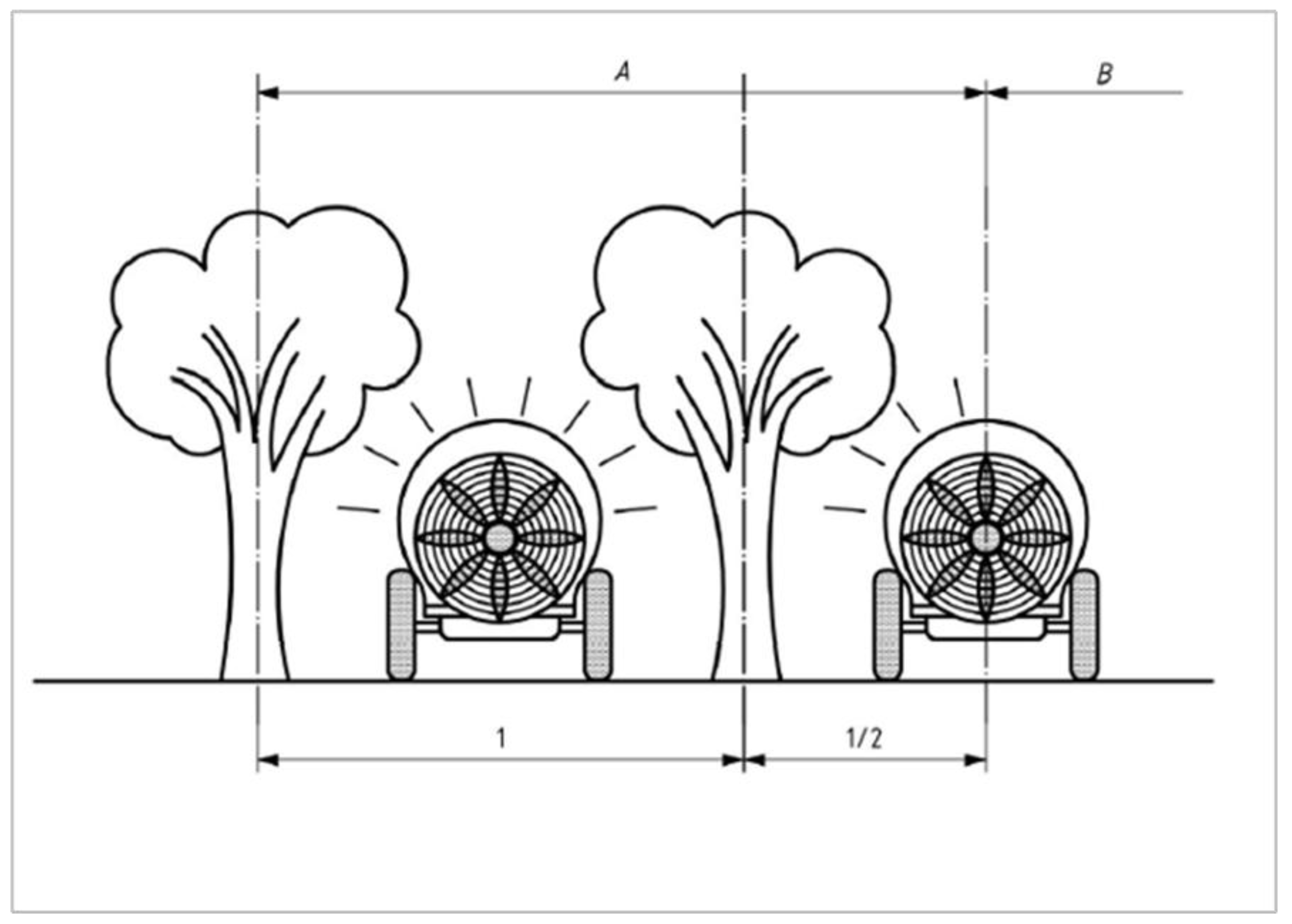

The response variable was tracer deposition on the leaves in the directly sprayed area measured at various locations (sides, thirds, and positions). Tracer deposition was assessed in Fractions 1 and ½, as prescribed in ISO 22866 [

25] (

Figure 1).

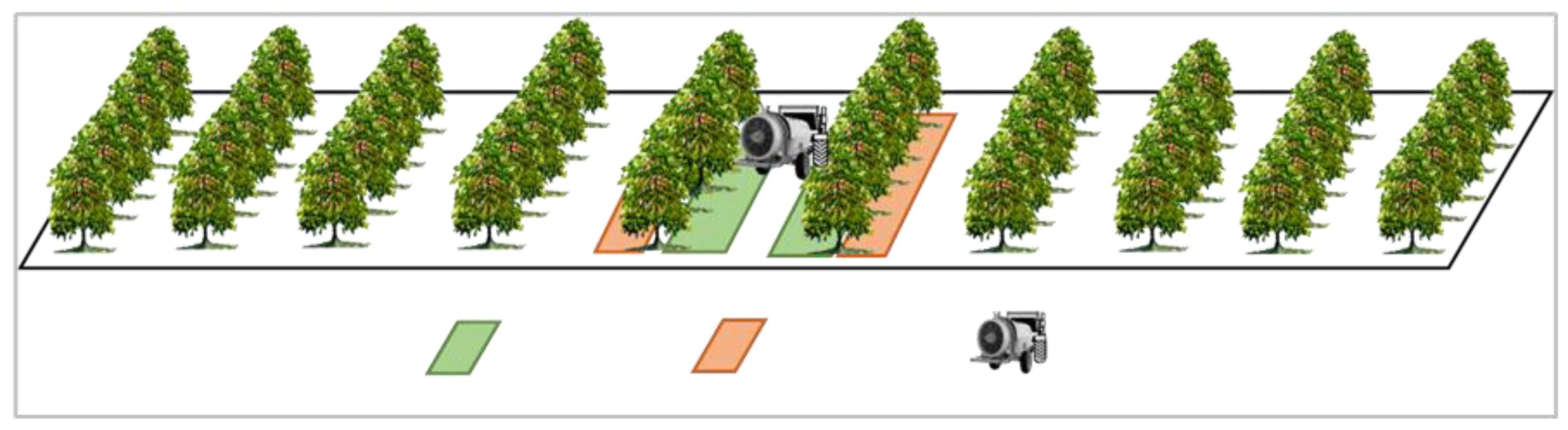

The different fractions were considered directly sprayed areas (

Figure 1), with Fraction 1 representing the distance between planting rows, i.e., the application interval used to determine the spray volume. Fraction ½ in the field was not considered for determining spray volume and did not fall within the drift zone. Therefore, depositions in Fraction 1 were referred to as ‘reference’, while those in Fraction ½ were designated as ‘transfer’ (

Figure 2).

The treatments were randomized based on application rate and jet type. Additional treatments were organized hierarchically within the application area defined by the combination of these treatments (3 × 2) and included application side, third of the plant, and branch position (

Figure 3).

The application was conducted using a hydropneumatic sprayer (turbo-atomiser), model Arbus 2000 TF 2P (Jacto, Pompeia, São Paulo, Brazil), with a tank capacity of 2,000 L. The sprayer featured 12 nozzle holders on each side arch, a piston pump delivering a flow rate of 75 Lmin⁻¹, and an axial-flow fan with a diameter of 850 mm positioned 1.10 m above ground level. The fan operated at an air speed of 26 ms⁻¹, producing an air volume of 11.2 m³s⁻¹. The fan blades were set to position ‘A’, which provides maximum air flow and is the standard configuration used by coffee farmers in the region.

The tractor used was a 4 × 2 FWD Auto model 4265 compact tractor (Massey Ferguson, Itu, São Paulo, Brazil) with a power output of 65 hp. The power take-off speed was set at 540 rpm, using an MDT2238A digital tachometer (Minipa®, Santo Amaro, São Paulo, Brazil). The tachometer remained fixed at 1,980 rpm, and the tractor operated in third gear at a speed of 6.45 kmh⁻¹ across all treatment areas.

Application rates were calibrated by adjusting the sprayer’s working pressure to match that of the hydraulic nozzle. Calibration was performed using a pressure gauge kit and a 1,000 mL graduated beaker. Vacuum cone jet tips (of angle 80°), traditionally used in coffee farming, and standard flat jet tips (of angle 110°), known for producing fine droplets, were selected for the experiment (

Table 1).

The coefficients of variation for the left and right booms were 2.52% and 2.27%, respectively, based on the flow rate of each ISO 5682-1 tip [

26]. The application was uniform on each side, with tip flow rate variation remaining below 10%, in accordance with the standard recommendations.

The spray mixture consisted of water and the food tracer Brilliant Blue (FD&C Blue No. 1), applied at a rate of 600 gha⁻¹. The required tracer concentrations were adjusted to 3.0, 1.5, and 1.0 gL⁻¹ for application rates of 200, 400, and 600 Lha⁻¹, respectively. Weather data during application were obtained from a Vantage Pro2 weather station (Davis, Hayward, California, USA), which recorded a temperature of 28.4 °C, a relative humidity of 66%, and a wind speed of 2.4 kmh-1, predominantly in an easterly direction.

The application commenced with a single pass of the sprayer targeting only the reference lane. Leaves were collected 15 min after application to allow adequate settling of the tracer. Collection was carried out from the reference and adjacent lane to assess deposition and transfer, respectively. Two pairs of leaves were sampled from the plagiotropic branch of a single plant in each plant section (upper, middle, and lower), and from both the inner and outer sides of the canopy. The leaves were placed in pre-labelled plastic bags, stored in Styrofoam boxes for thermal and light insulation, and transported to the laboratory for tracer quantification.

In the laboratory, 20 mL of distilled water was added to the plastic bags to remove the tracer. The solution was then transferred to a plastic container and stored in darkness for 24 h to allow impurities to settle. Subsequently, the absorbance of each sample was measured at 630 nm using a V-5000 spectrophotometer (Metash®, Songjiang District, Shanghai, China). The tracer concentration was determined from the absorbance using a calibration curve. The tracer mass on the leaves was calculated based on the initial spray concentration applied in the field and the dilution volume of the samples. Leaf area was measured using an LI 3100C leaf area meter (LI-COR, Lincoln, Nebraska, USA).

Statistical analyses were performed using RStudio software version 4.3.1A [

27]. The dataset was checked for outliers using boxplots. A linear mixed model was fitted using the lme4 package [

28], with parameters estimated via restricted maximum likelihood. The assumptions of homoscedasticity, normality, linearity, and independence were validated by analysing quantile-quantile plots of the normalised residuals and plotting the residuals against the explanatory variables and fitted values [

29].

The interactions among the application rate, jet type, third of the plants (lower, middle, and upper), branch position (internal and external), and their individual effects were considered as fixed factors for the model. The hierarchical structure of the harvest, considering the position within the third of the plant, jet type, and application area, was treated as a random factor. An initial mixed model was constructed with all fixed and random factors. If the model failed to converge due to its high complexity, alternative models with reduced complexity in the interactions between fixed and random factors were tested. When significant differences were detected, estimated means of the factors were compared using Tukey’s test at a 5% significance level, with Sidak adjustment, utilising the emmeans package [

30].

3. Results

3.1. Model Adjustment

The deposition data were fitted to a model that considered the interactions among application rate, jet type, third of the plants, and branch positions, as well as the derived triple and double interactions, treated as fixed effects. The application area and selection of thirds within the application were considered as random factors. For transfer, the fitted model considered interactions among the application rate, jet type, application side, third of the plants, and branch position, as well as doubly derived interactions, as fixed effects. The application area and third of the plants within the sides were considered random factors. More complex models were not pursued due to the low variability explained by the measured random factors and the high complexity of the fixed factor structure.

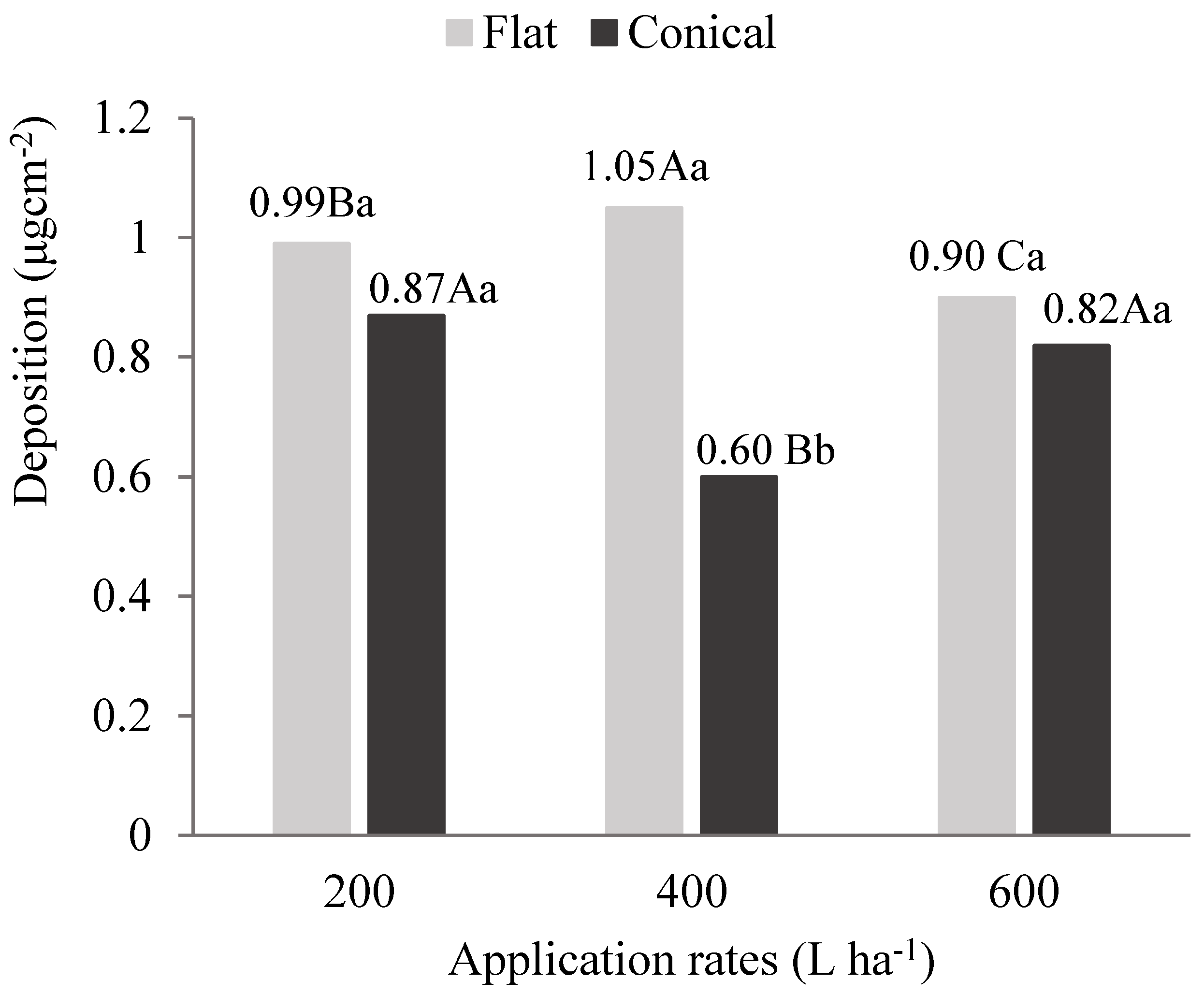

3.2. Reference Area Deposition for Different Jets and Application Rates

In the reference area, deposition was influenced by an interaction between application rate and jet type. Across different application rates, the standard flat jet produced the highest deposition at the 400 Lha

-1 rate, an intermediate deposition at the 200 Lha

-1 rate, and the lowest deposition at the 600 Lha

-1 rate. The conical jet produced the lowest deposition at the 400 Lha

-1 rate, while producing the highest deposition at the 200 Lha

-1 rate followed by that at the 600 Lha

-1 rate. Specifically, the standard flat jet tip produced a 75% higher deposition than the conical jet tip at the application rate of 400 Lha

-1, while no significant differences between the jets were observed at the other application rates (

Figure 4).

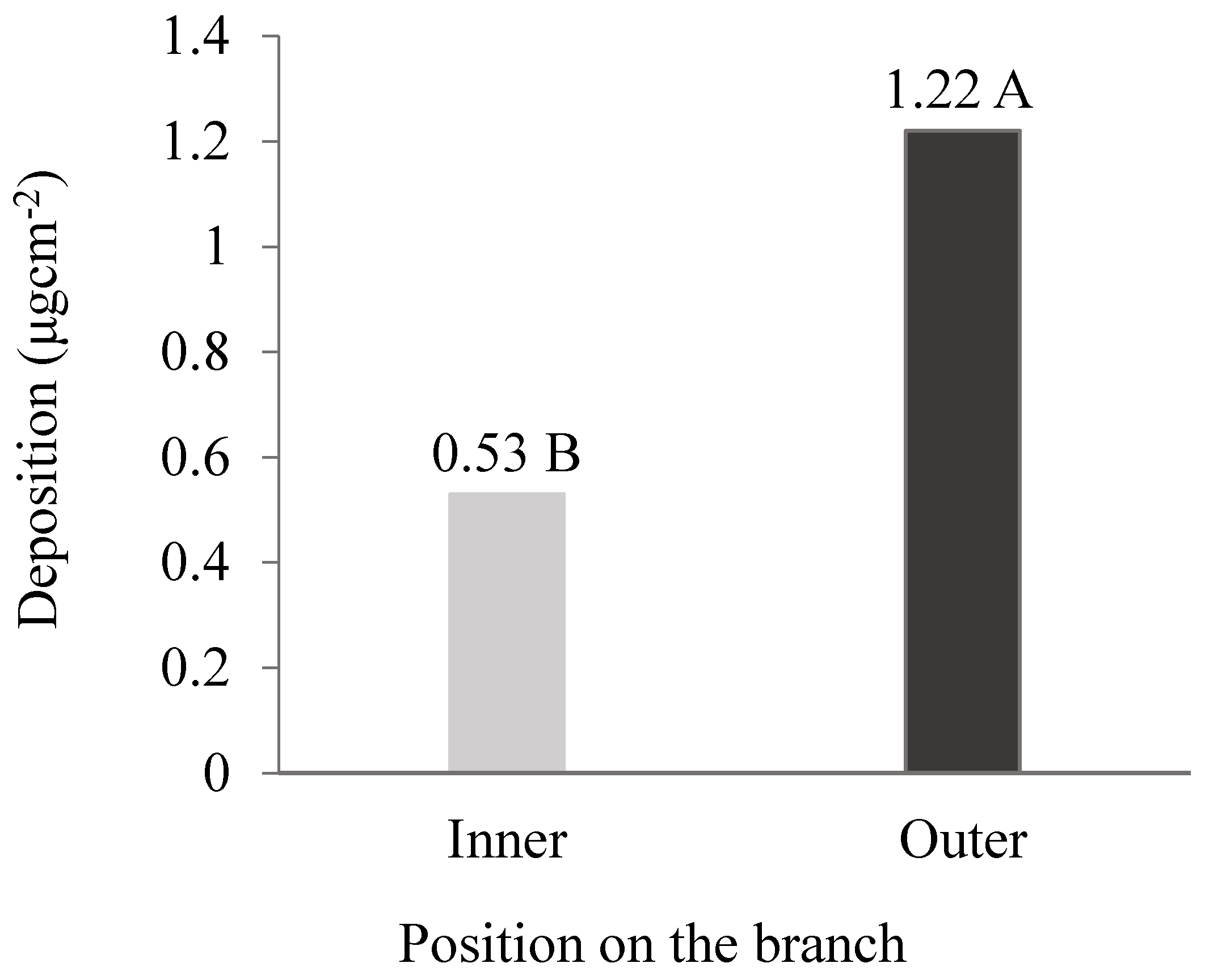

3.3. Deposition in the Reference Area at Different Positions on the Plagiotropic Branch

Deposition was influenced by both inner and outer positions of the branch, regardless of the jet type or application rate. Deposition on the outer side of the branch was 130% higher than that on the inner side (

Figure 5).

Due to the dense canopy, the deposition on the side of the plant facing the reference lane was higher at the outer position of the branch. In contrast, on the opposite (transverse) side of the plant, the highest tracer concentration was likely to occur at the inner position.

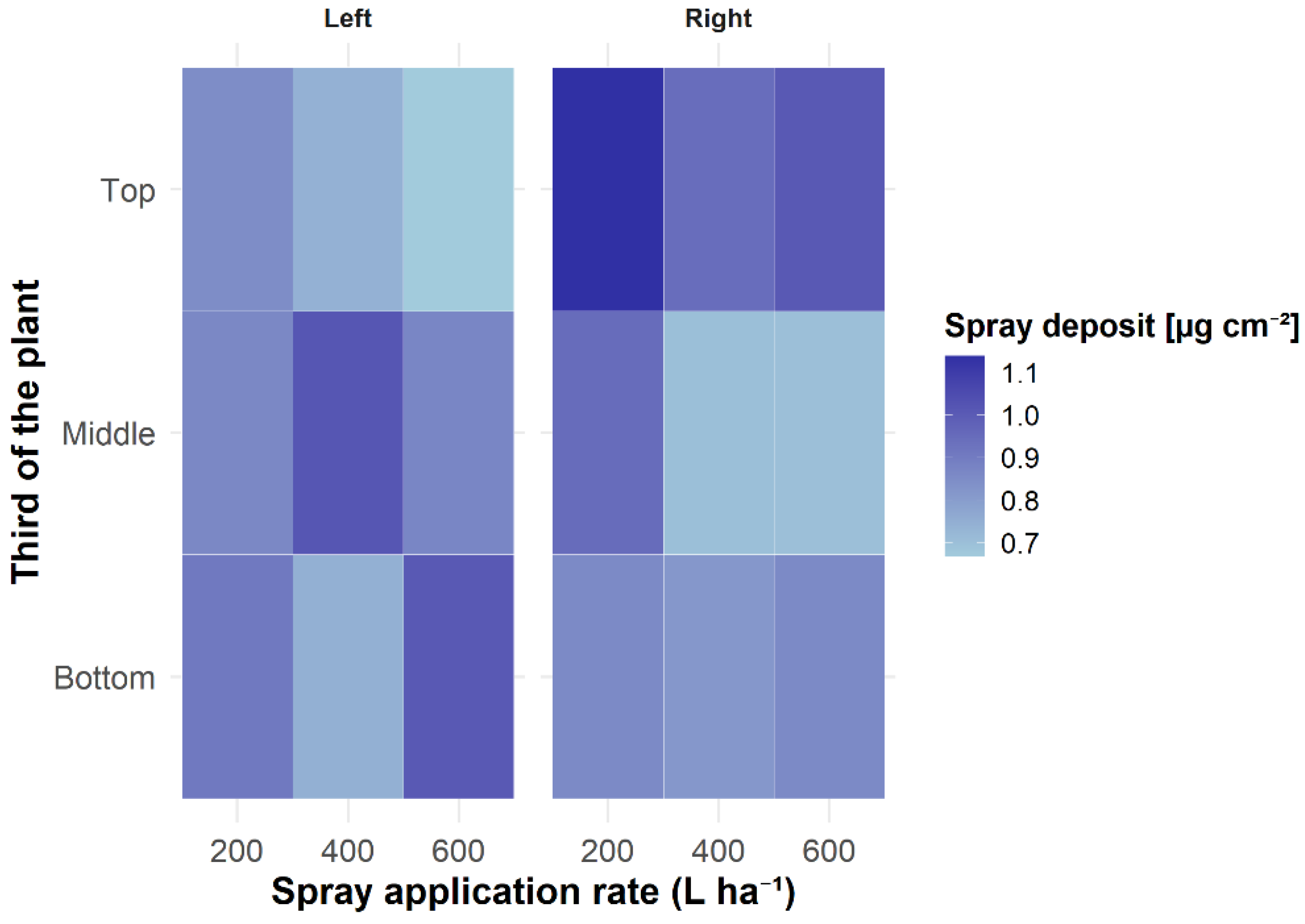

3.4. Deposition in the Reference Zone as a Function of Application Rates in the Application Sides and Canopy Thirds

Deposition in the reference zone was influenced by the interaction among application rate, third of the plant, and application side. In the colour map of

Figure 6, the highest tracer deposition in the reference zone was obtained in the top part of the canopy on the right side, specifically at application rate of 200 L ha

-1. In the lower third of the left application side, with the highest deposition occurring at the 600 Lha

-1 rate. Among the thirds, deposition was uniform at the 200 Lha

-1 only rate on the left side. Deposition decreased as the third of the plants increased; however, this trend was observed only on the left side at the 600 Lha

-1 rate. The opposite pattern was observed on the right side, where deposition increased at the 200 Lha

-1 rate. Between the application sides, tracer deposition was higher on the right side in the upper third at both the 200 and 600 Lha

-1 rates, and in the middle third at the 400 Lha

-1 rate.

The deposition on the upper right side was higher than that on the left side. This finding can be attributed to the alignment of the plagiotropic branch with the airflow on the right side, which was directed downward. In contrast, on the left side, the airflow was directed upwards, encountering more resistance when it collided with the branches.

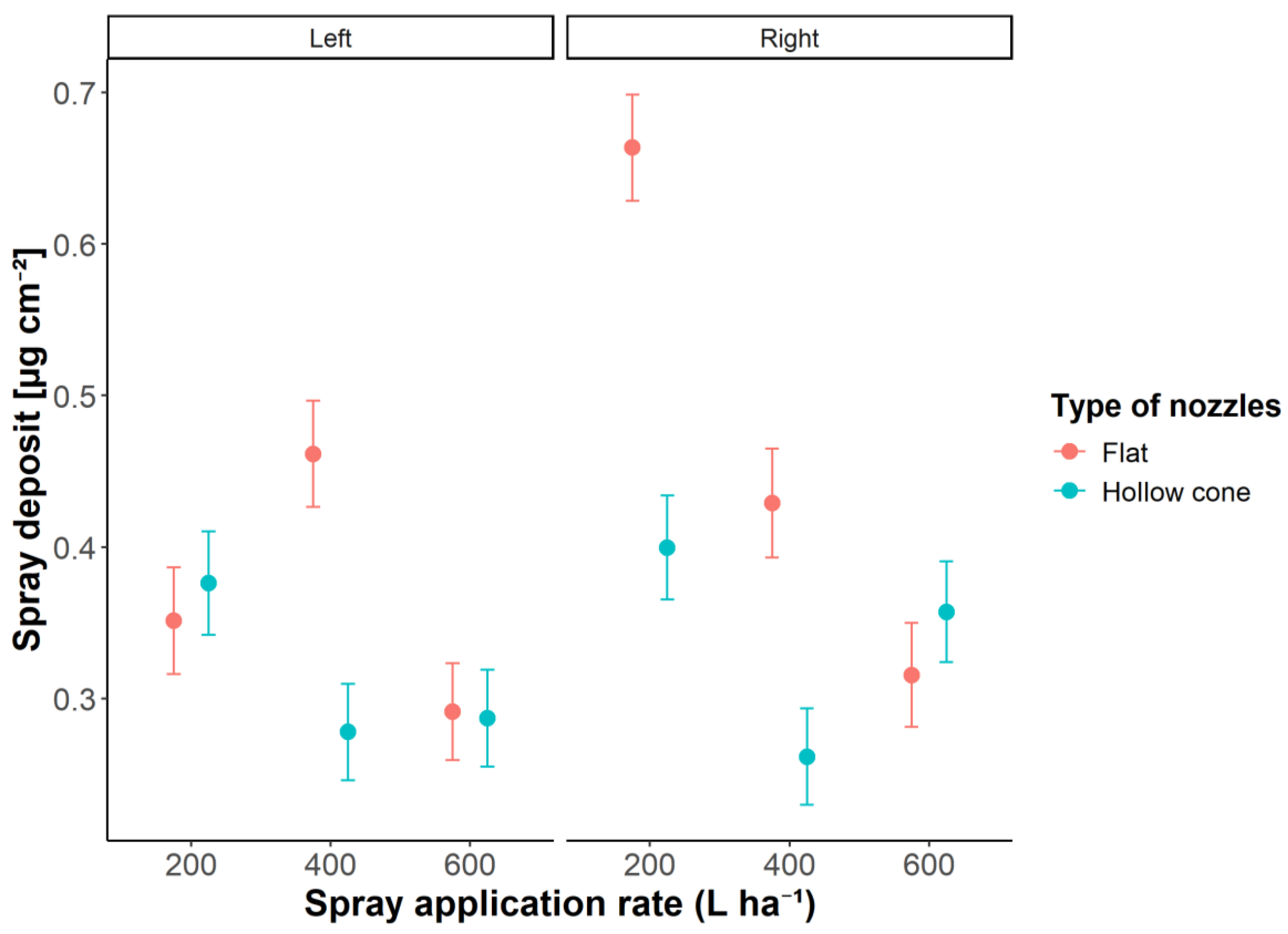

3.5. Transfer Through the Sides of the Application Boom

Figure 7 illustrates the interactions between nozzle type, application rate, and application side for transfer. Differences in transfer were observed between conical and flat spraying at the 400 Lha

-1 rate on the left side, and at the 200 and 400 Lha

-1 rates on the right side. For both nozzle types, the highest transfer occurred at the 200 Lha

-1 rate, but only on the right side, whereas low transfer occurred at the 400 and 600 Lha

-1 rates. At the 400 L ha-1 rate, the flat spray tip resulted in greater transfer on the left side, compared to the 600 L ha-1 rate. Overall, transfer was uniform between the application sides, with a higher transfer observed on the right side when using the flat spray tip at the 200 Lha

-1 rate.

Transfer is an uncommon variable with limited documentation in the literature. Therefore, this study aimed to relate transfer to tracer deposition for the reference lane. Tracer deposition was quantified in the directly sprayed areas. Our results indicated that jet types and application rates influenced transfer more than the application side. The heterogeneous airflow of the turbo sprayer tended to cause uneven deposition between application sides and between third of the plants in the reference lane; however, it did not significantly influence transfer.

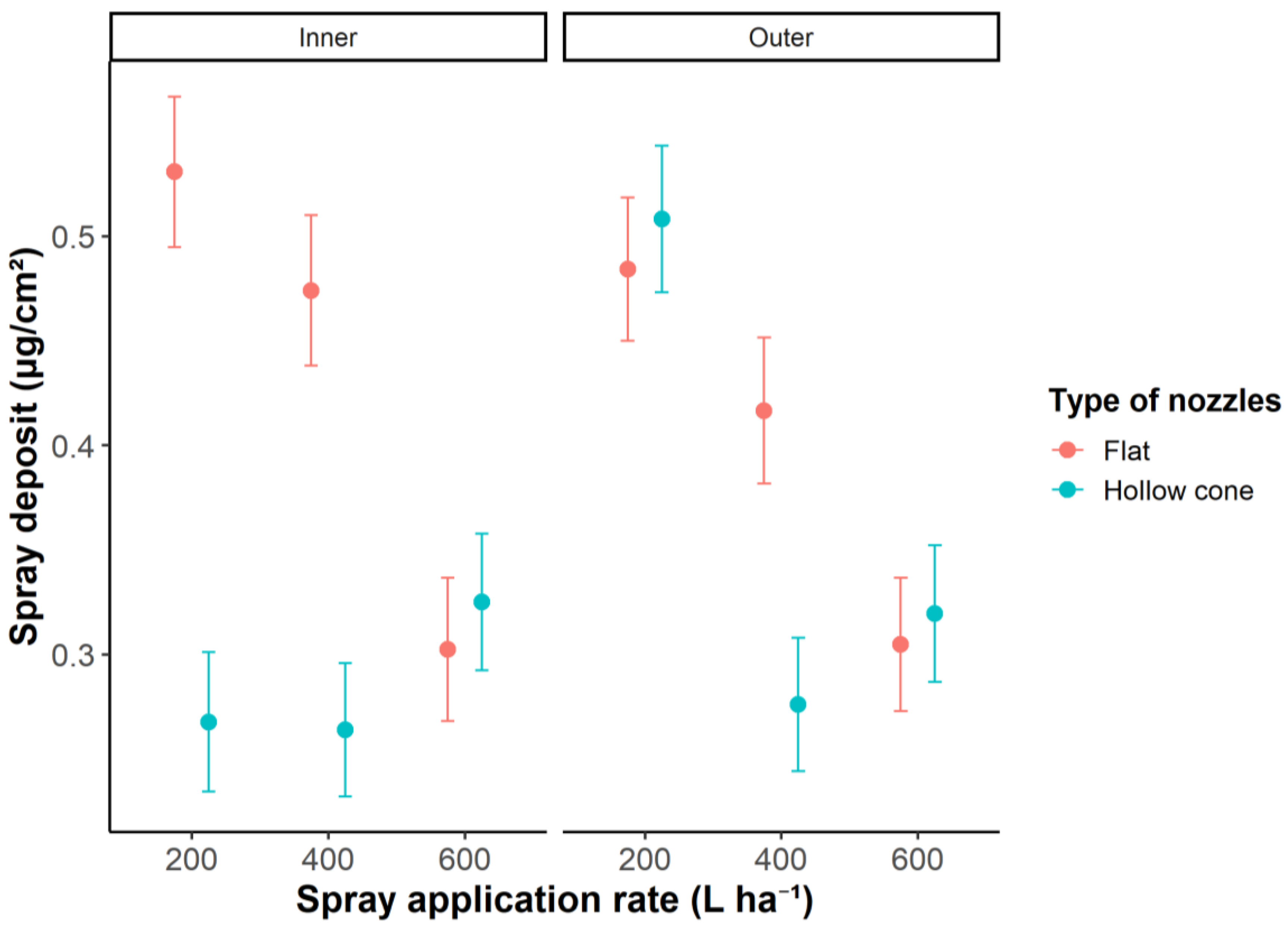

3.6. Transfer at Inner and Outer Canopy Positions

At both branch positions, the flat spray resulted in a higher transfer than the conical spray at the 400 Lha

-1 rate. However, at the 200 Lha

-1 rate, this difference was only observed at the inner position. The flat jet produced higher transfer at both branch positions at the 200 and 400 Lha

-1 rates than that at the 600 Lha

-1 rate. Transfer at the outer position was higher than that at the inner position, but only at the 200 Lha

-1 rate with the conical jet (

Figure 8).

The interaction between the 400 Lha-1 rate and the cone jet resulted in lower transfer at both branch positions, but lower deposition in the reference lane. Generally, transfer was similar across branch positions. The highest reference deposition was observed at the 400 Lha-1 rate with the flat nozzle, followed by that at the 200 Lha-1 rate with the flat nozzle, and finally that at the 200 Lha-1 rate with the conical nozzle. The combination of the 200 Lha-1 rate and the conical nozzle was the only one that showed higher transfer at the outer position, recording 85% and 15% higher transfer than that at the 400 Lha-1 and 600 Lha-1 rates, respectively.

Transfer was also influenced by the nozzle type; the flat nozzle produced the higher transfer. However, transfer was lower at both branch positions at the 600 Lha-1 rate, likely due to increased runoff, which also contributed to reduced deposition in the reference lane.

4. Discussion

The results of this study demonstrated that the studied variables influenced deposition and reference transfer in distinct ways. The flat jet tip outperformed the conical jet tip by operating at lower working pressures and providing more effective target coverage. In contrast, conical jet tips operated at higher pressures, and due to their droplet distribution dynamics, followed a more sinuous and slower path to reach the target. Spray pressure is a critical factor influencing droplet size and coverage, thereby affecting drift and deposition [

31].

In this study, deposition was higher at the outer branch position, regardless of jet type or speed. This effect can be attributed to the droplet cloud initially contacting the outer leaves of the plagiotropic branch. Effective deposition and coverage require matching the airflow volume with canopy density [

32]. However, the sprayer model used in this study allowed for only two airflow settings, with the higher setting being standard for coffee cultivation. Generally, the optimal air velocity required to reach the inner canopy is uncertain; plant density plays a crucial role in adjusting airflow and must be considered accordingly.

In this study, the highest deposition in the lower third of the canopy was observed at the highest application rate (600 L ha

-1), similar to that reported by [

33], who noted that a higher application rate (560 Lha

-1) combined with high turbine speed improved the mobility of coffee leaves, overcoming challenges posed by overlapping foliage. The upper third of the coffee canopy, being farthest from the spray tips, presents challenges for product deposition [

34]. The observed asymmetry in deposition across sides and thirds can be attributed to the resistance of the branches to the uneven airflow generated by the fan. The right side of the canopy receives higher air velocity due to the direction of turbine rotation, leading to increased aerosol deposition, while greater penetration occurs into the middle third of the plant on the left side due to the horizontal persistence of airflow, which contrasts with the findings of the current study [

35,

36].

It is important to note that deposition variability among third of the plants is higher on the application side. This underscores the need to stratify plants into thirds when measuring tracer retention on leaves. In addition to ensuring uniform distribution during application, the consistency of deposition across third of the plants must also be considered to minimize the risk of overdosing.

In this study, the air and droplet clouds generated by the turbo sprayer first contacted the side of the plant facing the spray passage, depositing the product on the outside of the branch before reaching the inside. The airflow then dissipated within the canopy; however, transfer continued, resulting in product deposition on the side of the plant adjacent to the spray passage—an overlap that allowed the product to be deposited on the treated areas. Approximately 29% of the tracer was directed towards the transfer areas. The interaction of the airflow with the inner canopy caused deposition to be less variable and more homogeneous across application sides and third of the plants. However, the disturbance of airflow may have interfered with the deposition of both reference and pass-through tracers. Plant architecture complicates airflow dynamics in and around the canopy [

37]. When the airflow passes through the canopy, its energy is altered, affecting the distribution of deposited droplets.

The deposition in the reference lane with the lowest transfer was observed at a rate of 200 Lha-1 with a conical jet tip. In contrast, maintaining the same rate with a flat jet tip resulted in higher carry-over. Notably, studies and applications aiming to reduce the drag should consider adjusting the fan blades to a lower airflow setting, which would influence deposition in the reference lane.

In Brazil, challenges associated with the application of crop protection products include sprayer calibration and determining the correct dosage for the spray tank. In coffee cultivation, the application range is defined by the spacing between planting rows, which influences both application rate and droplet distribution. During application, the sprayed strip not only receives deposition of the active ingredient at the recommended rate, but also experiences a fraction of transfer, which can spread to adjacent untreated rows. This transfer can lead to overdosing, potentially contributing to the selection of resistant biotypes and altering pest population dynamics. Pest resistance, pesticide residues, and environmental contamination are the primary concerns resulting from inaccurate dosing in crop fields [

38,

39]. Furthermore, economic losses continue to rise each year due to overlapping and overdosing, highlighting the importance of proper regulation and calibration of sprayers to achieve the recommended application rate in the target area.

Axial fan sprayers direct the spray to only one side of the planting row, whereas tunnel sprayers spray on both sides and may include recovery panels to collect and recycle excess spray that does not land on the target plant. Furthermore, tunnel sprayers are known to improve coverage and uniformity, reduce drift and off-target deposition, and increase the total application rate per cultivated area [

4,

9,

40]. Therefore, tunnel-type air-assisted sprayers may serve as a viable alternative for mitigating carryover. However, this technology has yet to be tested in coffee crop trials.

5. Conclusions

This study aimed to examine the deposition of droplets on plant leaves adjacent to the application band (transfer) and evaluate the impact of different operating conditions on spray mixture deposition across various plant parts and application sides. The highest reference deposition was observed with the flat spray tip; however, deposition was uneven across different third of the plants and lowest at the inner branch position, regardless of application rate. Optimal operating conditions for deposition with minimal transfer at low application volumes were identified. These included the 200 Lha-1 rate with cone-jet tips, which achieved higher deposition on the reference tramline and reduced carry-over, while flat-jet tips favoured higher carry-over. The average reference deposition was 0.87 μgcm-2, with carry-over at 0.36 μgcm-2. Studies on air-assisted sprayer applications that address overlapping spray mixtures to prevent application failures and overspraying in coffee crops are limited. Therefore, further studies should evaluate the impact of application technology variables in conjunction with transfer under different operating conditions, especially with regard to airflow, and explore the efficacy of phytosanitary products.

Inherently, field research involves variables that are challenging to control; however, it provides an authentic representation of operational conditions, and the performance of the equipment and technologies employed. For instance, wind speed and direction can influence both deposition and transfer. Further studies should consider factors such as canopy density, fan airflow, plant developmental stage, branch architecture, and leaf arrangement across cultivars. These variables are not limitations, but essential considerations to ensure that a wide range of field conditions and plant development stages are evaluated.

The quantification of carry-over, as demonstrated in this study, could drive substantial advancements in the hydropneumatic sprayer industry. These advancements would focus on developing machines and strategies that improve the targeting and retention of plant protection products on the intended canopy, thereby reducing drift losses. While applications can be optimized from both technical and environmental perspectives, the use of appropriate machinery remains crucial for ensuring effective application technology.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.O.F., R.Z., G.M.R and C.B. d. A.; methodology, L.O.F., G.M.R., R.Z., C.B. d. A and F.J.C.; software, L.O.F. and F.J.C.; validation, L.O.F. and F.J.C..; formal analysis, L.O.F., F.J.C and L.L.L..; investigation, L.O.F., G.M.R., R.Z., D.P.L.B, L.L.L. and C.B. d. A.; resources, L.O.F., G.M.R., R.Z., J. P. A. R. d. C. and C.B. d. A.; data curation, L.O.F., G.M.R. and R.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, L.O.F.; writing—review and editing, L. O. F., C.B. d. A., L.L.L. and J. P. A. R. d. C.; visualization, P. C. N. R. and J. P. A. R. d. C.; supervision, C.B. d. A and R.Z.; project administration, L.O.F. and C.B. d. A; funding acquisition, C.B. d. A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially supported by CAPES (Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel), under doctoral scholarship grant number 88887.643891/2021-00.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the

Article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Vitória, E. L.; Krohling, C. A.; Borges, F. R. P.; Ribeiro, L. F. O; Ribeiro, M. E. A.; Chen, P.; Lan, Y.; Wang, S.; Moraes, H. M. F.; Furtado Júnior, M. R. Efficiency of fungicide application an using an unmanned aerial vehicle and pneumatic sprayer for control of Hemileia vastatrix and Cercospora coffeicola in mountain coffee crops. Agronomy. 2023, 13, 340. [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, E.; Gil, E. Strategies to minimize spray drift for effective spraying in orchards and vineyards. FABE-533. Ohioline, 2022. Available online: https://ohioline.osu.edu/factsheet/fabe-533.

- Wei, Z.; Li, R.; Xue, X.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, S.; Li, Q.; Chang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, Y.; Dou, Q. Research status, methods and prospects of air-assisted spray technology. Agronomy. 2023, 13, 1407. [CrossRef]

- Planas, S.; Román, C.; Sanz, R.; Rosell-Polo, J. R. Bases for pesticide dose expression and adjustment in 3D crops and comparison of decision support systems. Science of The Total Environment. 2022, 806, 150357. [CrossRef]

- Salcedo, R.; Fonte, A.; Grella, M.; Garcerá, C.; Chueca, P. Blade pitch and air-outlet width effects on the airflow generated by an airblast sprayer with wireless remote-controlled axial fan. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture. 2021, 190, 106428. [CrossRef]

- Deveau, J.; Ledebuhr, M.; Manketelow, D. Airblast 101: Your guide to effective and efficient spraying. 2rd ed; Ontário: Canadá. 2021, pp. 305. Available online: https://platform.innoseta.eu/storage/training_material_files/1610107418_136075_2021_Airblast101-2ndEdition-ProtectedA7.pdf.

- Grella, M.; Marucco, P.; Zwertvaegher, I.; Gioelli, F.; Bozzer, C.; Biglia, A.; Manzone, M.; Caffini, A.; Fountas, S.; Nuyttens, D.; Balsari, P. The effect of fan setting, air-conveyor orientation and nozzle configuration on airblast sprayer efficiency: Insights relevant to trellised vineyards. Crop Protection. 2022, 155, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, F. K; Mota, A. A. B; Chechetto, R.G.; Antuniassi, U. R. Entendendo a tecnologia de aplicação: turbopulverizadores. 1ª ed; Botucatu: FEPAF. 2023, pp- 92. Available online: https://agroefetiva.com.br/entendendo-a-tecnologia-de-aplicacao-turbopulverizadores-1a-edicao/.

- Cheraiet, A.; Codis, S.; Lienard, A.; Vergès, A.; Carra, M.; Bastidon, D.; Bonicel, J. F.; Delpuech, X.; Ribeyrolles, X.; Douzals, J. P.; Lebeau, F.;Taylor, J. A.; Naud, O. EvaSprayViti: A flexible test bench for comparative assessment of the 3D deposition efficiency of vineyard sprayers at multiple growth stages. Biosystems Engineering. 2024, 241, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Crause, D. H.; da Vitória, E. L.; Ribeiro, L. F. O.; Ferreira, F. de A.; Lan, Y.; Chen, P. Droplet deposition of leaf fertilizers applied by an unmanned aerial vehicle in Coffea Canephora plants. Agronomy. 2023, 13, 1506. [CrossRef]

- Vigo-Morancho, A.; Videgain, M.; Boné, A.; Vidal, M.; García-Ramos, F. J. Static and dynamic study of the airflow behavior generated by two air assisted sprayers commonly used in 3D crops. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture. 2024, 216, 108535. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, W.; Lei, X.; Wang, S.; Li, X.; Norton, T. (2022). Canopy segmentation method for determining the spray deposition rate in orchards. Agronomy. 12(5), 1195. [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Zhou, H.; Lv, X.; Lei, X.; Tao, S. Study of the distribution characteristics of the airflow field in tree canopies based on the CFD model. Agronomy. 2022, 12, 3072. [CrossRef]

- Womac, A. R.; Ozkan, E.; Zhu, H.; Kochendorfer, J.; Jeon, H. Status of spray penetration and deposition in dense field crop canopies. Journal of the ASABE. 2022, 65, 1107–1117. [CrossRef]

- Petre, I. M.; Pop, S.; Boșcoianu, M. Engineering and management of the precision treatments spraying system implementation on horticultural crops. Rezultatele Cercetărilor Noastre Tehnice. 2023, 71, 249–255. [CrossRef]

- Xun, L.; Campos, J.; Salas, B.; Fabregas, F. X.; Zhu, H.; Gil, E. Advanced spraying systems to improve pesticide saving and reduce spray drift for apple orchards. Precision Agriculture. 2023, 24, 1526–1546. [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Zou, W.; Wang, X.; Chen, L.; Zhai, C. Wind loss model for the thick canopies of orchard trees based on accurate variable spraying. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2022, 13, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Herbst, A.; Bonds, J.; Wang, Z.; Zeng, A.; He, X.; Goff, P. The influence of unmanned agricultural aircraft system design on spray drift. Journal of Cultivated Plants/Journal für Kulturpflanzen. 2020, 72, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Jia, Y.; Luo, B.; Chen, C.; Wang, Y.; Kang, F.; Li, J. Deposition law of flat fan nozzle for pesticide application in horticultural plants. International Journal of Agricultural and Biological Engineering. 2022, 15, 27–38. Available online at: https://ijabe.org/index.php/ijabe/article/view/7502.

- Wang, S.; Li, X.; Nuyttens, D.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Y.; Li, X. Evaluationof compact air-induction flat fan nozzles for herbicide applications: Spray drift and biological efficacy. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2023, 14, 1018626. [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Douzals, J. P.; Lan, Y.; Cotteux, E.; Delpuech, X.; Pouxviel, G.; Zhan, Y. Characteristics of unmanned aerial spraying systems and related spray drift: A review. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2022, 13, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Neto, G. J.; da Cunha, J. P. A. R. Spray deposition and chemical control of the coffee leaf-miner with different spray nozzles and auxiliary boom. Engenharia Agrícola. 2016, 36, 656–663. [CrossRef]

- Beck, H. E.; McVicar, T. R.; Vergopolan, N.; Berg, A.; Lutsko, N. J.; Dufour, A.; Miralles, D. G. High-resolution (1 km) Köppen-Geiger maps for 1901–2099 based on constrained CMIP6 projections. Scientific data. 2023, 10, 724. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Dou, H.; Sun, H.; Zhai, C.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, F. Calculation method of canopy dynamic meshing division volumes for precision pesticide application in orchards based on LiDAR. Agronomy. 2023, 13, 1077. [CrossRef]

- ISO 22866:2005. Equipment for crop protection – methods for field measurement of spray drift. 1st ed. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland. 2005, pp. 1–17. Available online at: https://www.iso.org/standard/35161.html.

- ISO 5682-1:2017. Equipment for crop protection—spraying equipment—part 1: Test methods for sprayer nozzles. 3rd ed. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland. 2017, pp. 1–35. Available online at: https://www.iso.org/standard/60053.html.

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R foundation for statistical computing, Vienna, Austria, 2023. Available online at: https://www.R-project.org/.

- Bates, D.; Mächler, M.; Bolker, B.; Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software. 2015, 67, 1–48. [CrossRef]

- Ieno, E. N.; Luque, P. L.; Pierce, G. J.; Zuur, A. F.; Santos, M. B.; Walker, N. J.; Saveliev, A. A.; Smith, G. M. Three-way nested data for age determination techniques applied to cetaceans. In: Mixed effects models and extensions in ecology with R. Chapter 19. Statistics for Biology and Health. 2009, pp. 459–468. [CrossRef]

- Lenth, R. V. Emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least Squares Means. R package version 1.8.8. 2018. Available online at: http://cran.r-project.org/package=emmeans.

- Xue, X.; Zeng, K.; Li, N.; Luo, Q.; Ji, Y.; Li, Z.; Lyu, S.; Song, S. Parameters optimization and performance evaluation model of air-assisted electrostatic sprayer for citrus orchards. Agriculture. 2023, 13, 1498. [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, M. S.; Zahid, A.; He, L.; Martin, P. Opportunities and possibilities of developing an advanced precision spraying system for tree fruits. Sensors, 2021, 21, 3262. [CrossRef]

- Santinato, F.; da Silva; C. D.; da Silva, R. P.; Ormond, A. T. S.; Gonasalves, V. A. R.; Santinato, R. Development and technical validation of spray kit for coffee harvester. African Journal of Agricultural Research. 2019, 14, 571–575. [CrossRef]

- Alves, T. C.; Cunha, J. P. A. R.; Alves, G. S.; Silva, S. M.; Lemes, E. M. Canopy volume and application rate interaction on spray deposition for different phenological stages of coffee crop. Coffee Science. 2020, 15, e151777, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Rathnayake, A. P.; Chandel, A. K.; Schrader, M. J.; Hoheisel, G. A.; Khot, L. R. Spray patterns and perceptive canopy interaction assessment of commercial airblast sprayers used in Pacific Northwest perennial specialty crop production. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture. 2021, 184, 106097. [CrossRef]

- Khot, L. R. Air-assisted velocity profiles and perceptive canopy interactions of commercial airblast sprayers used in Pacific Northwest perennial specialty crop production. Agricultural Engineering International: CIGR Journal. 2022. 24. 78–89. https://cigrjournal.org/index.php/Ejounral/article/view/7039.

- Yan. C.; Niu. C.; Ma. S.; Tan. H.; Xu. L. CFD models as a tool to analyze the deformation behavior of grape leaves under an air-assisted sprayer. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture. 2022. 198. 107112. [CrossRef]

- İrsel. G. Design and implementation of low-cost field crop sprayer electronic flow control system. Gazi University Journal of Science. 2021. 34. 835–849. [CrossRef]

- Kumar. M.; Ajaykumara. K. M. Importance of pesticide dose in pest management. Indian Entomologist. 2022. 3. 51–54. Available online at: https://www.indianentomologist.org/vol3issue1.

- Patil. S. S.; Patil. Y.; Patil. S. B. Review on automatic variable-rate spraying systems based on orchard canopy characterization. Informatics and Automation. 2023. 22. 57–86. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).