1. Introduction

The transition into a super-aged society has emerged as a major global public health issue [

1], and the increasing proportion of the elderly population has intensified societal concern about health-related problems [

2,

3]. Among these, oral health issues in older adults are increasingly being recognised as a serious public health concern [

4]. Oral health in the elderly is not merely a dental issue but is closely linked to overall systemic health [

3]. Poor oral health can lead to various negative outcomes, including diminished chewing function, poor nutritional status, and social isolation [

5]. These problems not only reduce the quality of life of older adults but also contribute significantly to the deterioration of their overall health status [

4,

6].

Due to physiological, psychological, and social ageing, older adults often find it difficult to address various daily life challenges on their own, making collaboration among multidisciplinary healthcare professionals essential [

7,

8,

9]. In particular, to meet the complex health needs of older adults, a system that provides person-centred, integrated services through cooperation among experts from various fields is required [

10]. This cooperation is based on interprofessional work (IPW), the importance of which is increasingly emphasised in the context of an ageing society [

11,

12].

Since 2019, some local governments in Korea have implemented pilot projects for integrated community care [

13]. Since 2023, the Integrated Community Care in Older Adults (ICOA) program has been in operation, offering a variety of services [

14]. The core of the ICOA service is to provide integrated care based on collaboration among diverse healthcare professionals, including dentists, dental hygienists, nurses, traditional medicine doctors, pharmacists, and physical therapists [

8,

9]. This multidisciplinary approach is a key strategy not only for oral health management but also for improving overall health and quality of life [

6,

12]. However, despite growing recognition of the importance of oral health management for older adults in an ageing society [

4], systematic and sustainable programs and an effective operational model are still lacking [

15,

16].

A clear understanding of both the synergistic effects and limitations of interprofessional collaboration is a critical prerequisite for developing a practical and efficient home-visit oral care (HVOC) model [

17]. Therefore, it is necessary to thoroughly explore the experiences, collaborative processes, and institutional challenges encountered in HVOC settings, as well as the development of interprofessional education curricula for integrated care [

18], to provide future directions for the advancement of oral health management within the integrated care system.

An in-depth analysis of the experiences and perceptions of healthcare providers working in the ICOA field can serve as empirical and practical data for designing future customised HVOC programs based on the ICOA model [

19]. Accordingly, this study aimed to derive practical implications for developing an effective integrated HVOC model by thoroughly exploring the perceptions and experiences of multidisciplinary healthcare professionals involved in the ICOA program.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This study adopted a phenomenological approach to gain an in-depth understanding of the experiences of multidisciplinary professionals involved in providing HVOC within the ICOA system and to explore the meaning and essence of these experiences [

20]. To achieve this, a qualitative study was conducted using focus group interviews (FGIs) [

21].

2.2. Participants

The study participants were healthcare professionals working in the ICOA system. Sixteen individuals (eight in the first round of interviews and eight in the second) who provided written consent after being informed of the study’s purpose and procedures were selected.

The inclusion criteria were as follows:

Individuals with more than one year of practical experience in community-based health care or integrated community care services for older adults

Professionals currently working in the healthcare or caregiving field, including dental hygienists, nurses, social workers, caregivers, physicians/dentists, occupational therapists, and physical therapists

Individuals who voluntarily agreed to participate in FGIs after receiving sufficient explanation of the study’s purpose and methods

Individuals with no difficulties in communication (language or cognition) and who were able to participate in a 1–2-hour interview

The exclusion criteria were as follows:

Individuals not currently working in healthcare or caregiving, or with less than one year of relevant experience

Individuals with no practical experience related to the study topic (HVOC)

Individuals who, despite receiving an explanation of the study, did not provide written consent

Individuals with severe language or cognitive impairment, or health conditions that made participation in the FGIs difficult

Individuals who had already participated in an FGI for the same study

The first round of interviews was conducted with eight dental hygienists who had more than one year of field experience in providing HVOC under the ICOA system. Their clinical dental work experience was as follows: less than 5 years (1 person, 12.5%), 5–10 years (2 people, 25%), 10–15 years (2 people, 25%), and over 15 years (3 people, 37.5%). Their experience in HVOC care was 1 year (1 person, 12.5%), 2 years (4 people, 50%), and over 3 years (3 people, 37.5%) (

Table 1).

The second round of interviews included eight professionals with more than one year of experience in the same integrated care-based healthcare field. Their occupations were as follows: one Korean medicine doctor, one pharmacist, one home care nurse, one physical therapist, two local government officials (one social worker, one nurse), and two dental hygienists (

Table 1).

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

Data collection was conducted using FGI methods between 1

st October and 31

st October, 2023. Individual interviews lasting approximately 60 minutes per participant were conducted using a semi-structured open-ended questionnaire. The main questions focused on participants’ awareness of older adults’ health issues during the process of providing HVOC, the necessity of interprofessional collaboration, roles within integrated community care, experiences in oral health care, and strategies for improving collaboration. A detailed interview guide is presented in

Table 2.

The collected data were transcribed and r4epeatedly reviewed to extract meaningful statements and derive themes. Additional interviews were conducted as necessary until data saturation was reached. Each interview began in a natural and comfortable atmosphere and was gradually expanded into the research topic. With the participants’ consent, interviews were recorded using a smartphone and subsequently transcribed. The transcripts were checked for accuracy through repeated listening and then shared with the participants for member checking. Interviews were scheduled before or after working hours to avoid conflicts with the participants’ availability. When information was insufficient during the analysis phase, supplementary interviews were conducted for clarification.

Data analysis followed the phenomenological research framework using Colaizzi’s method of analysis [

22]. First, audio data collected from interviews with study participants were transcribed into text using the Naver AI program "CLOVA NOTE" and repeatedly read to grasp the overall meaning and context. Second, meaningful statements related to the research topic were identified and extracted through a thorough review of the transcripts. Third, the extracted statements were rephrased into general expressions to derive core meanings, and similar statements were categorised and organised into comprehensive theme clusters. Fourth, based on these theme clusters, the key themes that emerged from the experiences of HVOC providers within the ICOA system were identified. Fifth, the results of the analysis were reviewed through consultation with a dental hygiene professor experienced in qualitative research, and the participants confirmed the derived themes and essential structures to ensure the study’s credibility and validity.

Through this analytical process, this study aimed to gain an in-depth understanding of the experiences of multidisciplinary professionals involved in providing HVOC within the ICOA.

2.4. Ethical Considerations

This study adhered to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was conducted with the approval of the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of D University (IRB No: DKU 2023-07-026-007). Before the interviews, participants were fully informed about the purpose and procedures of the study, including the audio recording of the interviews, and provided voluntary written consent. Anonymity and confidentiality were strictly maintained throughout data collection and analysis. All data were stored as audio files and used solely for research purposes. Participants were assured that confidentiality would be protected and that there would be no disadvantages resulting from participation. Additionally, the participants were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time. To ensure anonymity, case numbers were assigned instead of using the participants’ names during recording.

3. Results

The FGIs exploring the experiences of multidisciplinary professionals involved in providing HVOC within the ICOA system yielded 134 meaningful statements. These statements were categorised into 10 themes, which were then grouped into four overarching theme clusters (

Table 3). The final theme clusters were as follows: 1) Knowledge, 2) Skill, 3) Value, and 4) Multidisciplinary Organisational Efforts.

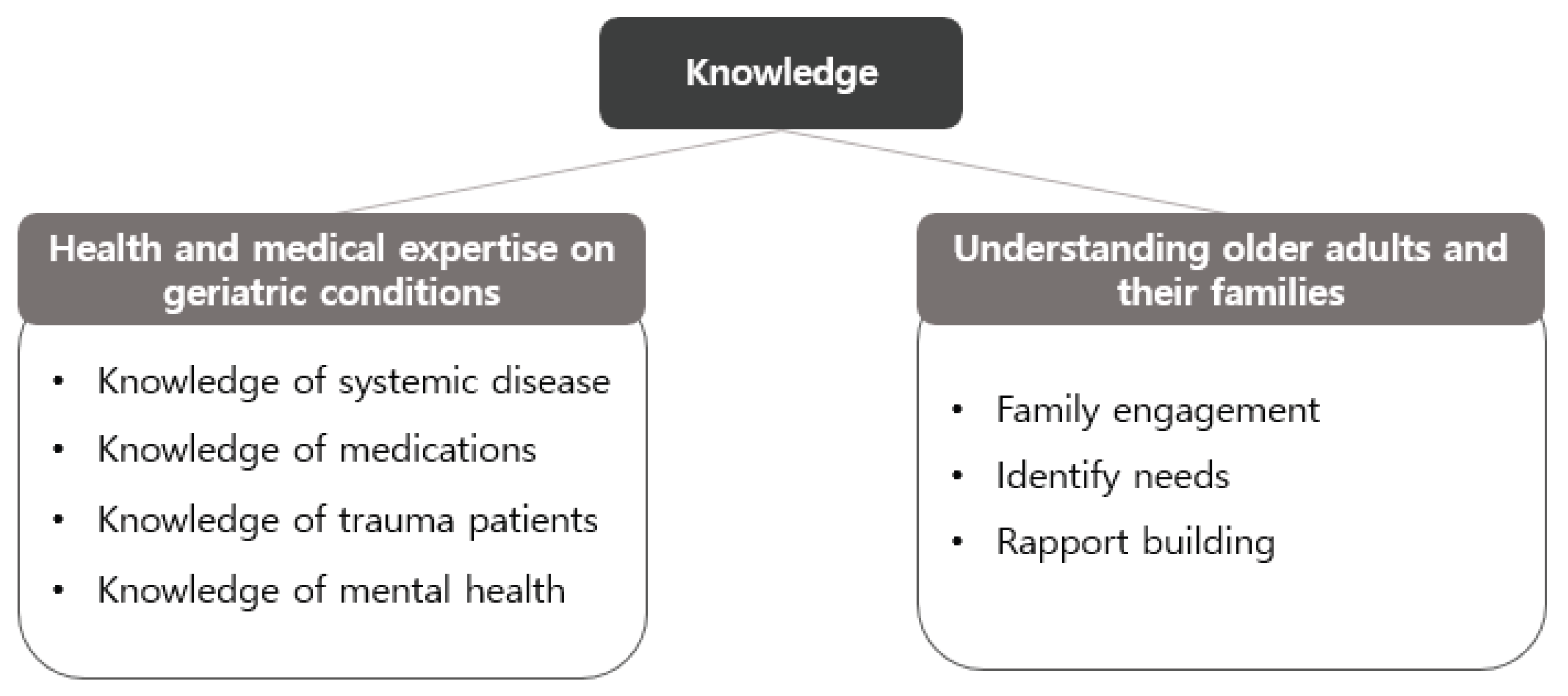

3.1. Theme 1: Knowledge

Multidisciplinary professionals emphasised that the core of interprofessional collaboration from a knowledge-based perspective lies in the systematic and regular sharing of expertise related to older adults’ health. In particular, they pointed out the need to enhance the connection between oral health and overall systemic health by comprehensively understanding and sharing knowledge about the complex health characteristics of older adults, such as systemic diseases, polypharmacy, and cognitive decline (

Figure 1).

“There needs to be a system in which professionals from each field regularly share and collaborate on cases involving older adults’ systemic diseases, medications, and oral health conditions.” (Dental hygienist H)

“Older adults are often reluctant to open their mouths, so various professionals need to collaborate in creating psychological stability and identifying their needs.” (Dental hygienist E)

“I’ve seen firsthand that oral health is directly linked to systemic health issues like pneumonia and diabetes. Even if oral problems are recognised, the lack of dental knowledge limits intervention. I believe integrating home nursing and oral health care would enable more effective care.” (Nurse 1)

Professionals agreed that such a structure for integrated health information sharing helps complement the expertise of each profession and is essential for enhancing the effectiveness of integrated community care.

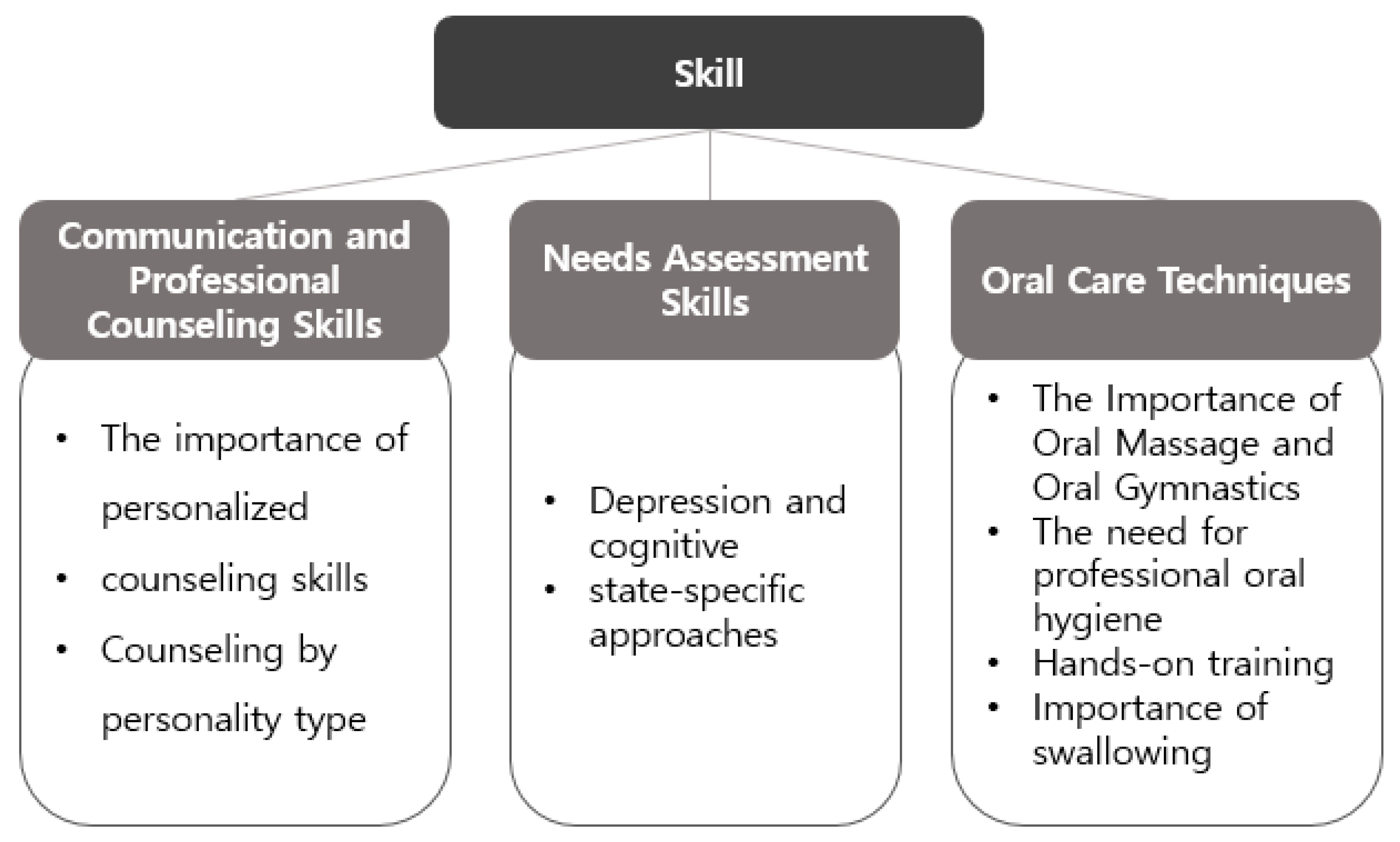

3.2. Theme 2: Skill

Multidisciplinary professionals emphasised the importance of personalised consultation and communication skills tailored to the diverse physical and cognitive characteristics of older adults. They pointed out the need for collaborative strategies among professionals to increase practical applicability in the field. They also agreed that oral care skills go beyond hygiene maintenance and are closely linked to swallowing, nutrition, and rehabilitation, making interprofessional collaboration essential (

Figure 2).

“Professionals from each field should collaborate to develop and share tailored consultation techniques for different types of older adults to enhance the quality of service.” (Dental hygienist E)

“Oral care is directly related to physical function recovery and eating ability. When training for physical activity, oral pain or dental conditions often affect performance. I would like to connect basic oral assessments with oral hygiene needs.” (Physical therapist)

“Dietary habits and medication adherence in older adults are closely associated with oral health. In particular, for older individuals with dementia, effective medication management requires not only collaboration with care workers but also the establishment of a multidisciplinary system in which health information, including oral conditions, is shared among professionals.” (Pharmacist)

“Interprofessional collaboration requires continuous and integrated professional training so that oral hygiene management can be connected with swallowing, feeding, and systemic health.” (Dental hygienist A)

The professionals stressed that the integration of technical skills and a structured training system serves as a critical foundation for improving the quality of HVOC services.

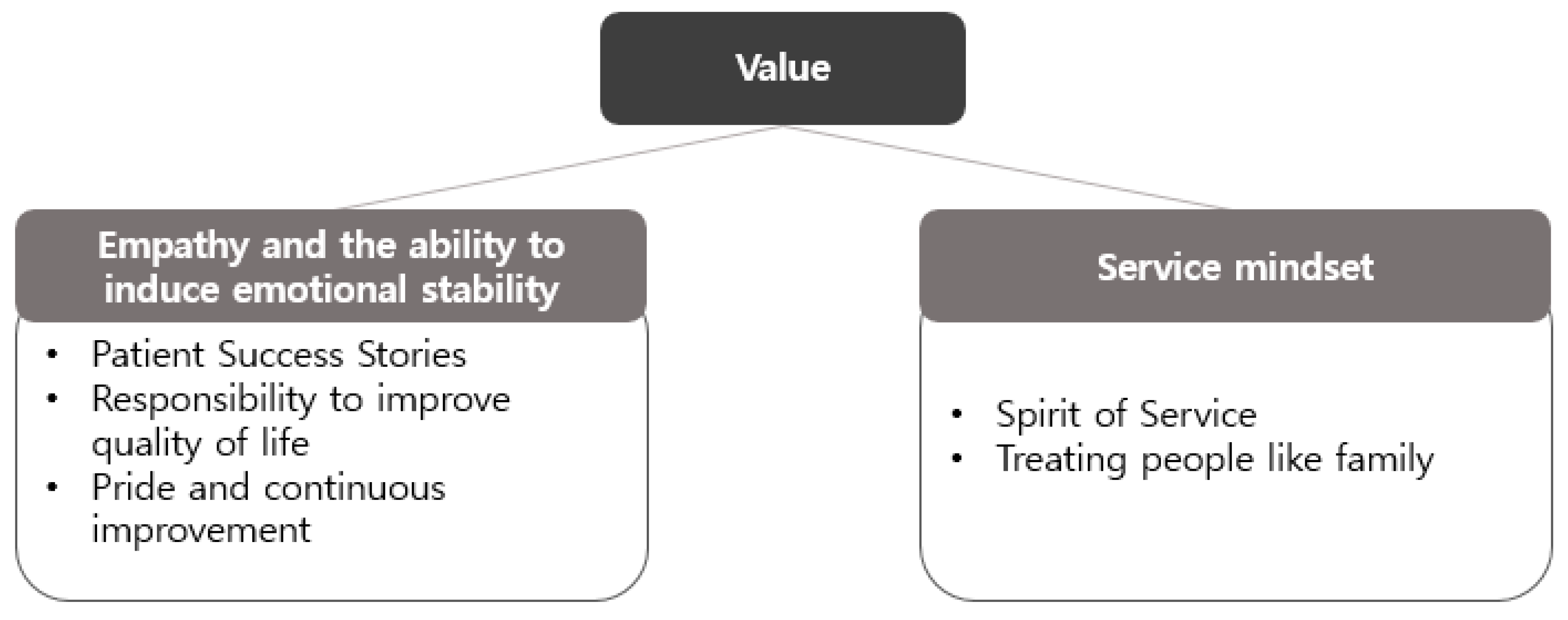

3.3. Theme 3: Value

From a value-based perspective, professionals emphasised that an empathy-centred, patient-oriented approach founded on multidisciplinary collaboration promotes emotional stability and self-esteem recovery, ultimately contributing to an improved quality of life. This approach emerged as a core value of interprofessional collaboration and was found to have a positive impact on the professional pride of healthcare providers (

Figure 3).

“Professionals from different fields need to collaborate in guiding patients through successful experiences and providing emotional support based on empathy.” (Dental hygienist D)

“It’s very important to sincerely care for patients and to continuously improve professional expertise through Interprofessional Collaboration.” (Dental hygienist E)

“Oral issues are risk factors for systemic diseases and impact overall health in older adults. However, owing to the lack of a home-based care system, effective intervention is difficult. Strengthening the roles of other professions is essential, and early detection and prevention through multidisciplinary approaches are especially important.” (Nurse 2)

The collective insights confirmed that sharing patient-centred values enhances motivation for collaboration and serves as a catalyst for the sustainability of HVOC services.

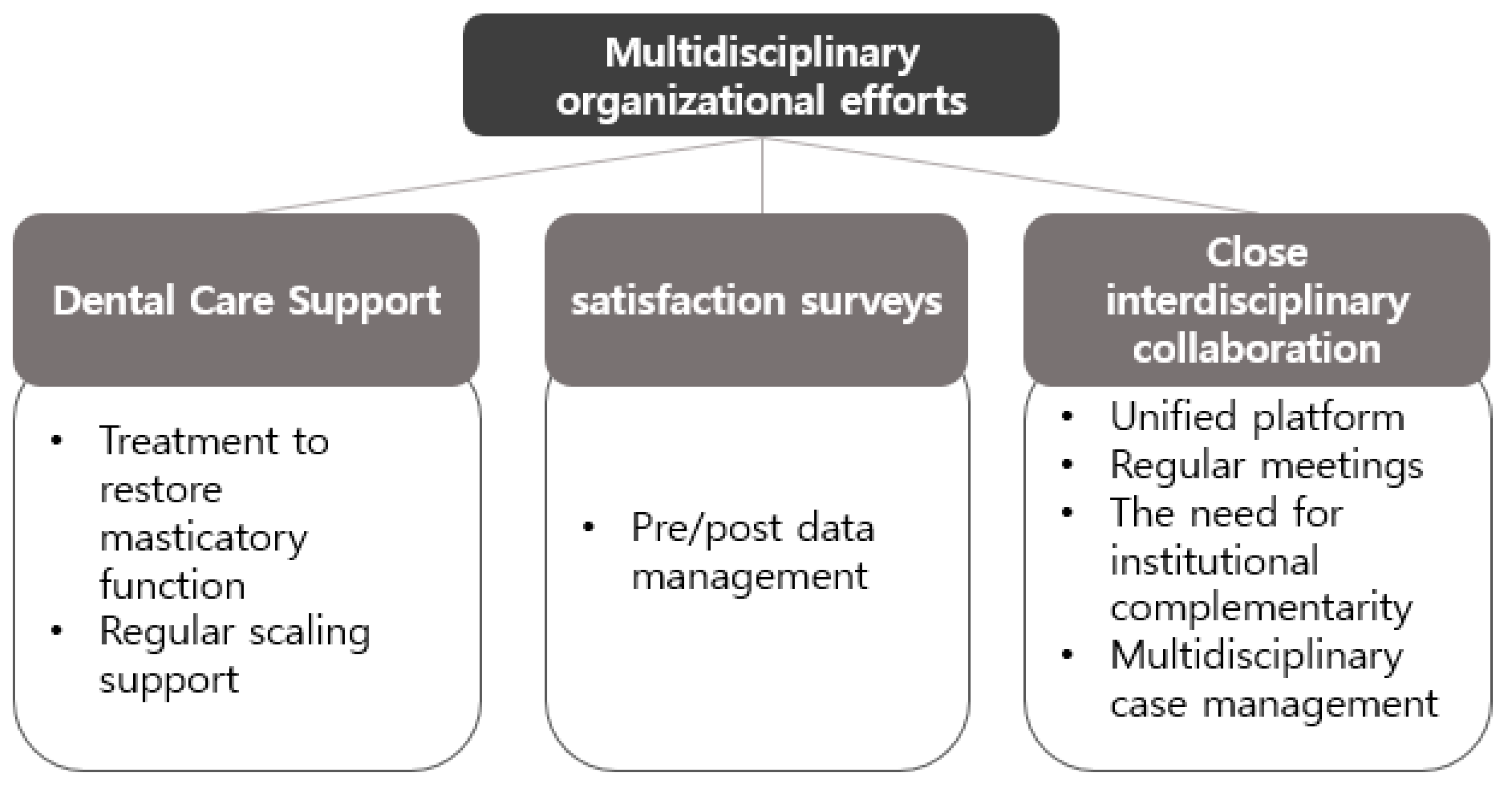

3.4. Theme 4: Multidisciplinary Organisational Efforts

At the organisational level, key factors for enhancing the efficiency and sustainability of HVOC services included clarifying role allocation, building data-driven integrated management platforms, and implementing systematic satisfaction and performance evaluation mechanisms (

Figure 4).

“It’s necessary to establish clear role-sharing and collaboration systems among professionals—for example, Korean medicine doctors can oversee digestive and dementia care, while dental hygienists can support oral health and masticatory function.” (Korean medicine doctor I)

“Professionals from each field must collaborate to build a platform for integrated patient data management and institutional improvement.” (Social worker)

Multidisciplinary professionals recognised that establishing structured collaboration systems and integrated platforms for HVOC is foundational for expanding service provision and informing policy development.

4. Discussion

In an ageing society, the need for HVOC within integrated community care is steadily increasing [

14]. This study identified key elements to enhance the effectiveness of HVOC through a multidisciplinary approach by targeting individuals with experience in the ICOA program. The analysis revealed four thematic clusters—Knowledge, Skill, Value, and Multidisciplinary Organisational Efforts—highlighting how interprofessional collaboration can contribute practically and be expanded.

First, in the knowledge domain, professionals expressed the need for expanded roles and deeper expertise. This study confirmed that an integrated understanding and regular sharing of information, beyond dental knowledge to include systemic conditions, polypharmacy, cognitive and mental health, and family caregiving environments, are essential. Oral health is closely linked to diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and dementia [

23,

24,

25], whereas polypharmacy-induced xerostomia affects chewing and swallowing functions [

26]. In elderly care facilities, specialised oral care provided by dentists led to lower recurrence rates of aspiration pneumonia compared to standard nursing care [

27]. Home-visit oral health education also improved xerostomia and swallowing-related quality of life among older adults in integrated community care [

28]. These findings demonstrate that when dentists and dental hygienists contribute their expertise through multidisciplinary collaboration, elderly health outcomes improve. Therefore, systematic knowledge sharing through cross-professional education and joint case meetings may help to identify individual needs and contribute to improving both systemic and oral health.

Second, in the skill domain, the challenge lies in bridging service gaps between professions. multidisciplinary professionals agreed that oral health is directly tied to systemic health and that preventive care is vital. However, the lack of interprofessional information-sharing systems was identified as a major limitation. There was consensus on the need to establish an HVOC system centred on dental hygienists, alongside basic training and manuals for other professions. HVOC should be formally recognised as an essential area within integrated care services. Joint development and training of practical skills, such as personalised consultation, oral assessments, oral massage, facial exercises, and swallowing training, were especially emphasised.

Technical integration among dental hygienists, physical therapists, and nurses is a fundamental component of integrated community care, enabling the simultaneous management of physical function and nutritional status in older adults [

29]. However, vague role definitions, hierarchy-related conflicts, and inefficient workflows can hinder collaboration between the health and welfare sectors [

29]. Communication among multidisciplinary personnel is a key factor influencing organisational cooperation in ICOA [

30], and effective communication is believed to enhance service quality and ultimately contribute to improved quality of life in older adults [

31,

32].

Third, in the value domain, empathy-based, patient-centred approaches were confirmed as the ethical foundation of multidisciplinary collaboration. Alleviating patient anxiety and guiding them toward positive experiences not only improves quality of life but also boosts providers’ professional pride [

33]. Several studies have shown that multidisciplinary approaches enhance not only physical health but also psychological stability, social support, and independence [

34,

35,

36,

37]. These core elements should be carefully considered when applying HVOC programs.

Fourth, on the organisational effort level, clarifying roles, building integrated platforms, and establishing institutional foundations emerged as core strategies. Successful integrated community care requires local governance built on horizontal public-private networks centred on the community. Strengthening local government delivery systems and securing specialised personnel are critical [

19]. A prime example is the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) in the U.S., where multidisciplinary teams deliver care with outstanding outcomes in health maintenance and independent living support [

38]. To activate integrated care, building HVOC teams led by dental hygienists and expanding integrated management platforms and infrastructure based on patient data are essential.

In summary, future multidisciplinary HVOC programs should evolve in the following directions: continuous reinforcement of interprofessional collaboration, ongoing education and training to enhance service providers’ skills and communication, and expansion of empathy-based, patient-centred approaches.

Policy support and the establishment of integrated management platforms are necessary to improve the effectiveness and sustainability of collaboration.

4.1. Strengths, Limitations, and Future Research Directions

This study is academically significant as it is the first to conduct an in-depth analysis of strategies for multidisciplinary collaboration in HVOC by focusing on ICOA intervention providers. Its findings offer essential insights for the development of tailored HVOC protocols, which are increasingly in demand and based on interprofessional collaboration.

Qualitative research emphasises representativeness and suitability in participant selection [

39]. However, the participants of this study were limited to a small number of local governments operating HVOC programs, which introduces the possibility of regional and selection bias. In addition, the participants were limited to dental hygienists, nurses, Korean medicine doctors, physical therapists, pharmacists, and social workers. The participation of a broader range of professionals, including physicians, dentists, and speech therapists, was not achieved. Future studies should expand the scope to include more diverse professionals and regional characteristics. Longitudinal research is also needed to validate the effectiveness of customised HVOC protocols that reflect the core elements identified in this study.

5. Conclusions

Multidisciplinary professionals with experience in ICOA-recognised HVOC programs are a key factor not only in improving the oral health of older adults but also in enhancing their overall quality of life. They emphasised that providing HVOC through interprofessional collaboration must carefully and practically consider four aspects: Knowledge, Skill, Value, and Multidisciplinary Organisational Efforts. To activate HVOC within integrated community care, the following are needed: continuous strengthening of multidisciplinary collaboration systems, ongoing training and education to enhance provider competencies, expansion of empathy-based, patient-centred approaches, and policy support and development of integrated management platforms. Through these efforts, a sustainable HVOC system that promotes the health and well-being of older adults can be established.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, J.-H.J.; Methodology, S.-R.J., and J.-H.J.; Software, S.-R.J.; Validation, S.-R.J., B.-R.S., and J.-H.J.; Formal analysis, S.-R.J.; Investigation, S.-R.J. and B.-R.S.; Resources, S.-R.J.; Data curation, S.-R.J.; Writing—original draft preparation, S.-R.J. and J.-H.J.; Writing—review and editing, J.-H.J., and S.-R.J.; Visualization, S.-R.J., and J.-H.J.; Supervision, J.-H.J.; Project administration, J.-H.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study did not receive external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Dankook University (DKU: 2023-07-026-007 on 27 September 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all those who participated in the home-visit oral care activities based on integrated community care in Cheonan City.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FGI |

Focus group interview |

| HVOC |

Home-visit oral care |

| ICOA |

Integrated community care in older adults |

| IPW |

Interprofessional work |

References

- Hong, C.; Sun, L.; Liu, G.; Guan, B.; Li, C.; Luo, Y. Response of global health towards the challenges presented by population aging. China CDC Wkly. 2023, 5, 884–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, E.-S.; Kim, B.-I.; Jung, H.-I. Age, period and cohort trends in oral health status in South Korean adults. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2021, 49, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-B.; Han, K.-D.; Park, Y.-G. Ko, Y.-K. Association between socioeconomic status and oral health behaviors: the 2008-2010 Korea national health and nutrition examination survey. Exp. Ther. Med. 2016, 12, 2657–2664. [CrossRef]

- Lipsky, M.S.; Singh, T.; Zakeri, G.; Hung, M. Oral health and older adults: a narrative review. Dent. J. 2024, 12, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenthöfer, A.; Rammelsberg, P.; Cabrera, T.; Schröder, J.; Hassel, A.J. Determinants of oral health-related quality of life of the institutionalized elderly. Psychogeriatrics 2014, 14, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saruta, J.; Nakagawa, K.; Morinaga, H. Kobayashi, I. Interdisciplinary collaboration for managing xerostomia in patients with systemic diseases. J. Multidiscip. Health 2022, 15, 127–135. [Google Scholar]

- Kandelman, D.; Petersen, P.E.; Ueda, H. Oral health, general health, and quality of life in older people. Spec. Care Dentist. 2008, 28, 224–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooten, D.; Youngblut, J.M.; Hannan, J.; Guido-Sanz, F. The impact of interprofessional collaboration on the effectiveness, significance, and future of advanced practice registered nurses. Nurs. Clin. North Am. 2012, 47, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katon, W.J.; Lin, E.H.; Von Korff, M.; Ciechanowski, P.; Ludman, E.J.; Young, B.; Peterson, D.; Rutter, C.M.; McGregor, M.; McCulloch, D. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 2611–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, C.; Drennan, V.; Scheibl, F.; Shah, D.; Manthorpe, J.; Gage, H.; Iliffe, S. Models of interprofessional working for older people living at home: a survey and review of the local strategies of English health and social care statutory organisations. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2011, 11, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, D.; Goodman, C.; Gage, H.; Baron, N.; Scheibl, F.; Iliffe, S.; Manthorpe, J.; Bunn, F.; Drennan, V. The effectiveness of inter-professional working for older people living in the community: a systematic review. Health Soc. Care Community 2013, 21, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint-Pierre, C.; Herskovic, V.; Sepúlveda, M. Multidisciplinary collaboration in primary care: a systematic review. Fam. Pract. 2018, 35, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.-B.; Park, S.-S. A systematic literature review on community care: focusing on the analysis of pilot projects. Korean J. Care Manag. 2025, 54, 209–240. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, J.-H. Oral health care intervention protocol for older adults at home in dental hygienists: a narrative literature review. J. Korean Soc. Dent. Hyg. 2023, 23, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, S.C.; Marcelo, V.C.; da Silva, E.T.; Leles, C.R. Oral health of institutionalised elderly: a qualitative study of health careivers’ perceptions in Brazil. Gerodontology 2011, 28, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forsell, M.; Kullberg, E.; Hoogstraate, J.; Johansson, O.; Sjogren, P. An evidence-based oral hygiene education program for nursing staff. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2011, 11, 256–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.-W.; Jang, J.-H. Evaluation of interprofessional education (IPE) competency for oral health care based on integrated care for older adults in dental hygienists. J. Korean Soc. Dent. Hyg. 2024, 24, 597–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.-N.; Yoon, J.-Y.; Oh, K.-S.; Kim, J.-A. Development of the interprofessional education curriculum for community care. J. Long Term Care. 2024, 12, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, D. Issues in the integrated community care and the implementation of the integrated community care support act. Health Welfare Policy Forum 2025, 340, 4–23. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, K.-H. Qualitative Research Methodology, 1st ed.; Hakjisa: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2023, 50-65. [Google Scholar]

- David, W.S.; Prem, N.S. Focus Group Research Methodology, 3rd ed.; Hakjisa: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2018, 60-110. [Google Scholar]

- Colaizzi, P.F. Psychological Research as the Phenomenologist Views It. In Existential Phenomenological Alternatives for Psychology; Valle, R.S., Mark, K., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, 1978; pp. 48–71. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, M.; Moffat, R.; Gill, G.; Lauren, E.; Ruiz-Negrón, B.; Rosales, M.N.; Richey, J.; Licari, F.W. Oral health as a gateway to overall health and well-being: surveillance of the geriatric population in the United States. Spec. Care Dent. 2019, 39, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botelho, J.; Mascarenhas, P.; Viana, J.; Proença, L.; Orlandi, M.; Leira, Y.; Chambrone, L.; Mendes, J.J.; Machado, V. An umbrella review of the evidence linking oral health and systemic noncommunicable diseases. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azami-Aghdash, S.; Ebadi, S.S.; Sardareh, M.; Pournaghi-Azar, F.; Karami, S.; Pouyan, S.N.; Derakhshani, N. The impact of professional oral health care on the oral health of older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanasiewicz, M.; Hildebrandt, T.; Obersztyn, I. Xerostomia of various etiologies: A review of the literature. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2016, 25, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyagami, T.; Nishizaki, Y.; Imada, R.; Yamaguchi, K.; Nojima, M.; Kataoka, K.; Sakairi, M.; Aoki, N.; Furusaka, T.; Kushiro, S.; Yang, K.S.; Morikawa, T.; Tohara, H.; Naito, T. Dental care to reduce aspiration pneumonia recurrence: a prospective cohort study. Int. Dent. J. 2024, 74, 816–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ki, J.-Y.; Jo, S.-R.; Cho, K.-S.; Park, J.-E.; Cho, J.-W.; Jang, J.-H. Effect of Oral Health Education using a mobile app (OHEMA) on the oral health and swallowing-related quality of life in community-based integrated care of the elderly: a randomized clinical trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.-H.; Kim, C.-S.; Seo, J.-H. Collaboration in health and welfare: from the perspective of nurses and social workers at the integrated care center. Korean J. Care Manag. 2024, 50, 31–61. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, S.-H.; Cho, S.-M. Relationship between communication and organizational cooperation among integrated care service workers: examining the mediation effect of trust. J. Korean Soc. Welfare Adm. 2024, 26, 55–83. [Google Scholar]

- Sehgal, N.L.; Fox, M.; Vidyarthi, A.R.; Sharpe, B.A.; Gearhart, S.; Bookwalter, T.; Barker, J.; Alldredge, B.K.; Blegen, M.A.; Wachter, R.M. ; Triad for Optimal Patient Safety Project. A multidisciplinary teamwork training program: the Triad for Optimal Patient Safety (TOPS) experience. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2008, 23, 2053–2057. [Google Scholar]

- Seneviratne, C.J.; Lau, M.W.J.; Goh, B.T. The role of dentists in COVID-19 is beyond dentistry: voluntary medical engagements and future preparedness. Front. Med. 2020, 7, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, Y.-J. The effect of health change awareness of integrated elderly care health guardians on quality of life: focusing on the mediating effect of self-worth awareness and continued participation willingness. J. Reg. Stud. 2024, 32, 35–60. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, N.E. Multidisciplinary in-hospital teams improve patient outcomes: a review. Surg. Neurol. Int. 2014, 5, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langmann, E. Vulnerability, ageism, and health: is it helpful to label older adults as a vulnerable group in health care? Med. Health Care Philos. 2023, 26, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, S.; Otis, M.; Greenfield, G.; Razzaq, N.; Solanki, D.; Norton, J.; Richardson, S.; Hayhoe, B.W.J. Improving multidisciplinary team working to support integrated care for people with frailty amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Integr. Care 2023, 23, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grady, P.A.; Gough, L.L. Self-management: a comprehensive approach to management of chronic conditions. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, e25–e31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keough, M.E.; Field, T.S.; Gurwitz, J.H. A model of community-based interdisciplinary team training in the care of the frail elderly. Acad. Med. 2002, 77, 936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.-P. Theoretical justification for the representativeness of participant(sample)s’ selection in qualitative research: focusing on Mead’s self-theory. J. Qual. Inq. 2021, 7, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).