1. Introduction

In recent years, the rubber industry is developing rapidly along with the high-speed development of the global automobile industry. In order to meet the development needs of the automobile industry, the production and waste of tires have been rising year by year. According to statistics, the world produces about 1.4 billion waste tires (WTs) every year, equivalent to about 25 million tons of solid waste [

1]. China's tire production reaches 1.187 billion units in 2024, with demand accounting for more than 40% of the global total [

2,

3].

Although WTs contain highly valuable materials-such as natural and synthetic rubber, carbon black, steel wire, and polyester fiber-their potential for resource recovery remains largely underexploited. Each of these components has significant reuse potential in various industrial applications, yet vast quantities of waste tire material are still discarded. According to recent estimates, over 600,000 tons of non-recyclable rubber waste are improperly managed or landfilled annually [

4,

5]. Globally, only 3-15% of waste tire material is actually recycled into secondary raw materials, such as crumb rubber or recovered carbon black. In contrast, 5-23% of tires are reused-primarily through retreading or second-hand export-while the majority is subject to non-recycling-based disposal: 20-30% ends up in landfills or stockpiles, and 25-60% is incinerated for energy recovery [

6].

The extremely low recycling rate highlights a critical gap in global waste tire management. Bridging this gap is essential not only for reducing environmental harm, but also for achieving circular economy goals and carbon neutrality targets in the materials and mobility sectors.

At present, the main waste tire treatment routes include retreading, mechanical recycling (e.g., crumb rubber production), incineration, and landfilling. Each of these methods plays a role in managing end-of-life tires, but they also face substantial environmental and resource efficiency limitations.

Retreading, which involves reapplying new treads to waste tires, is an effective form of reuse with relatively low environmental impact. However, it is limited to certain tire types (e.g., commercial truck tires) and depends on strict quality control of the casing. Mechanical recycling, particularly the production of crumb rubber, allows tires to be reused in road surfacing, playgrounds, and rubber-modified asphalt. Yet, such downcycling applications often represent low-value use of high-value materials and do not contribute meaningfully to carbon mitigation. Moreover, the market for crumb rubber remains volatile due to performance concerns and potential environmental leaching [

7].

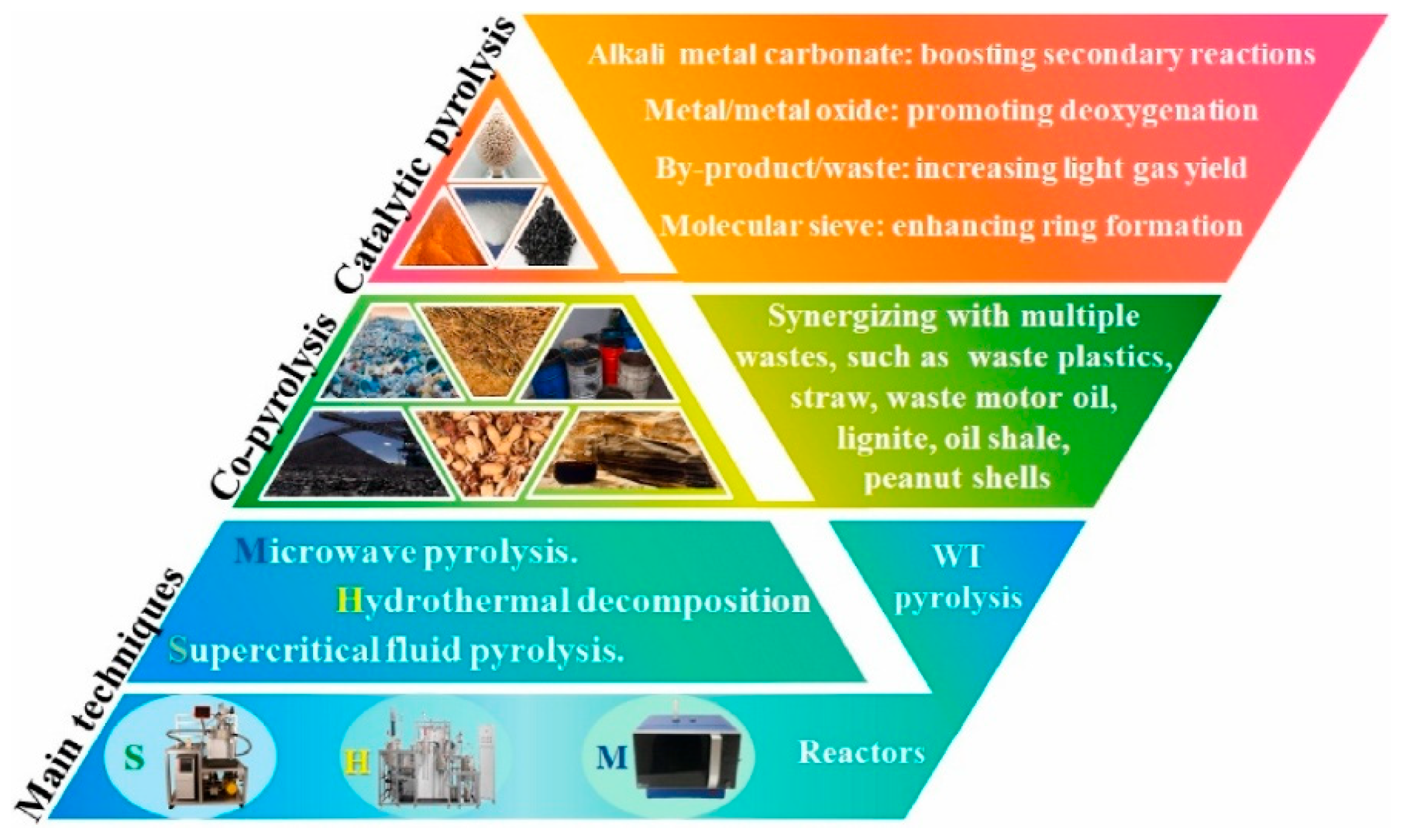

Figure 1.

Main techniques of WT pyrolysis. Source: Wang et al., 2022 [

8].

Figure 1.

Main techniques of WT pyrolysis. Source: Wang et al., 2022 [

8].

In contrast, incineration recovers energy by direct combustion but emits approximately 2.8 tons of CO

2 per ton of tire burned, along with harmful compounds such as sulfur dioxide (SO

2), nitrogen oxides (NO

x), and dioxins [

9]. Landfilling, while still practiced in some regions, occupies large areas and creates persistent environmental risks due to the non-biodegradable nature of rubber and potential leaching of heavy metals. Crucially, both incineration and landfilling fail to recover valuable tire constituents such as carbon black, steel wire, and liquid hydrocarbons-representing significant losses in material circularity [

10,

11].

Given these limitations, pyrolysis has emerged as a promising thermochemical conversion pathway, offering both high recovery efficiency and lower environmental impact. The process involves heating waste tires in an oxygen-deficient or inert atmosphere—typically between 250 ℃ and 900 ℃-resulting in multiple outputs: tire pyrolysis oil (TPO), pyrolysis gas (TPG), recovered carbon black (rCB), and steel wire. Unlike incineration, pyrolysis avoids direct oxidation and significantly reduces process-related CO

2 emissions. More importantly, its products can substitute for fossil-based fuels and materials: TPO can replace diesel in industrial boilers or engines, while rCB has potential as a partial substitute for virgin carbon black. These substitution effects, when considered across the life cycle, significantly enhance the carbon reduction performance of pyrolysis [

8,

12].

While pyrolysis is widely recognized for its potential in resource recovery, its carbon reduction performance remains debated. Three key challenges—uncertain emission mechanisms, technical inefficiencies, and missing policy support—hinder a clear assessment of its decarbonization role.

First, although pyrolysis yields potentially valuable products—such as TPO, rCB, and TPG—that could replace fossil-based fuels and materials, current studies vary widely in how they define system boundaries, allocate environmental burdens, and model substitution effects. As a result, estimates of pyrolysis’s climate benefits are highly inconsistent across the literature. This lack of methodological coherence makes it difficult to assess whether pyrolysis can be considered a genuinely low-carbon solution, and under what conditions it may outperform other waste tire management pathways.

Second, product quality issues and high energy use reduce the carbon benefits of pyrolysis. High sulfur TPO requires further treatment, increasing emissions [

13], while electricity use may contribute 60-80% of total emissions [

14], especially in carbon-intensive grids.

Third, the absence of recognized carbon offset protocols for pyrolysis limits access to climate finance. Unlike renewable energy, products like TPO and rCB lack standard crediting methods under systems like EU ETS (European Union Emissions Trading System) or VCS (Verified Carbon Standard), weakening economic incentives for scaling up.

To address these gaps, this review aims to clarify whether pyrolysis can fulfill its dual role in waste valorization and carbon mitigation. It focuses on three core questions:

What carbon reduction mechanisms underlie the pyrolysis of waste tires, and how are they enabled by its major products—TPO, rCB, and TPG?

How do existing LCA-based studies evaluate and compare the carbon performance of pyrolysis systems, and what methodological challenges remain?

What are the key factors required to transition pyrolysis from laboratory validation to scalable, standardized, and policy-integrated industrial deployment?

By synthesizing the latest literature and comparing representative case studies, this review seeks to provide a structured overview of the current state, limitations, and future potential of waste tire pyrolysis in the context of climate mitigation and circular economy transitions.

2. Waste Tire Pyrolysis Technology

To understand the emission reduction mechanisms of waste tire pyrolysis, it is essential to first examine the pyrolysis process itself. Pyrolysis is a thermochemical treatment carried out under oxygen-deficient conditions, in which rubber polymers are broken down into a mixture of gaseous, liquid, and solid fractions. This chapter provides an overview of both conventional and modified pyrolysis technologies, with emphasis on their operational characteristics, product profiles, and relevance to carbon mitigation through material and energy substitution.

Conventional pyrolysis of waste tires typically operates at temperatures between 400 ℃ to 700 ℃, decomposing tire materials into three major product streams: TPO, TPG, and rCB, along with a small amount of recoverable steel. TPO is a complex liquid composed of aliphatic and aromatic hydrocarbons, usually accounting for 40-50% of the input mass, and has a calorific value comparable to diesel. TPG, composed mainly of light hydrocarbons such as CH4, CO, and H2, constitutes approximately 10-15% and is often used to supply heat back to the system. The solid residue, rCB, represents 30-40% of the output and consists primarily of carbon and inorganic fillers. While all three fractions have substitution potential for fossil-derived fuels and materials, the quality of these products-particularly the high sulfur content of TPO and the ash and heavy metal content in rCB, which can limit their application without further upgrading.

To address the limitations of conventional pyrolysis, various modified technologies have emerged that enhance both energy efficiency and product usability. These advancements are directly linked to the carbon reduction mechanisms elaborated in subsequent chapters. Modified systems aim to reduce external energy inputs and improve the quality of output products, thereby increasing the overall emission reduction potential. For instance, the reuse of pyrolysis gas for internal heating significantly reduces dependence on grid electricity or natural gas, lowering Scope 2 emissions. More advanced designs, such as microwave-assisted and solar-heated reactors, have demonstrated even greater reductions in external energy demand [

15]. In parallel, the integration of catalysts, such as zeolites or metal oxides, during the pyrolysis process promotes cleaner cracking pathways, resulting in lighter, lower-sulfur oil fractions [

16]. Similarly, the post-treatment of rCB through acid washing, activation, and blending techniques can significantly increase its compatibility with rubber formulations, thus raising its substitution ratio for virgin carbon black [

17].

Table 1 summarizes the typical differences between conventional and modified pyrolysis systems in terms of process parameters, product composition, and emission reduction potential. As shown, modified systems tend to operate at lower temperatures, produce higher-quality outputs, and achieve greater carbon savings—making them increasingly relevant in the context of circular economy and decarbonization targets.

This technological progression lays the groundwork for understanding how pyrolysis enables indirect emission reductions through both energy self-sufficiency and material substitution. These mechanisms are further explored in the following chapter.

WT technology is a final disposal method with the advantages of environmental friendliness, high resource recycling rate, low raw material quality requirements, large utilization volume and high product value, which is considered to be the future direction of waste tire resource utilization [

21]. In general, waste tire pyrolysis can be obtained 45%-50% pyrolysis oil, 32%-36% carbon black and 12%-15% steel wire [

22]. The method is widely applicable that can be used in the petrochemical, energy, and steel industries.

3. Carbon Reduction Mechanisms

To assess the decarbonization potential of waste tire pyrolysis, it is essential to understand the mechanisms through which it contributes to greenhouse gas (GHG) mitigation. The current literature identifies two major pathways: material substitution and energy self-sufficiency. This chapter conceptually classifies these pathways and explains the underlying mechanisms by which different pyrolysis-derived products contribute to emission reductions.

Although the energy content of TPG theoretically allows broader application, such as power generation or fuel substitution, practical challenges—including its complex chemical composition, sulfur content, and safety concerns during compression and transport—have largely confined its use to internal circulation within pyrolysis facilities [

23,

24]. Therefore, in most LCA models, emission reduction from TPG is framed as an avoided energy input, rather than a product-based substitution.

3.1. Overview of Material Substitution Pathways

One of the most widely recognized carbon mitigation pathways in waste tire pyrolysis is the substitution of fossil-based materials with pyrolysis-derived products. This pathway operates on the principle that the environmental burden of manufacturing conventional fuels and materials—such as diesel and virgin carbon black (vCB)—can be avoided if equivalent functionality is provided by TPO and rCB. From a life cycle perspective, such substitution reduces upstream emissions linked to fossil resource extraction, chemical processing, and thermal transformation.

3.1.1. Tire Pyrolysis Oil as a Diesel Substitute

TPO is one of the principal products obtained from the thermal decomposition of waste tires and typically constitutes 40-50 wt% of the pyrolysis output. Its high heating value—ranging from 44.20 to 45.09 MJ/kg—is nearly equivalent to that of commercial diesel fuel (≈45 MJ/kg), making it a viable alternative in energy-intensive applications such as industrial boilers, cement kilns, and stationary diesel engines The energy substitution pathway enabled by TPO is widely regarded as a cornerstone of carbon mitigation in pyrolysis systems.

From a feedstock perspective, the carbon advantage of TPO lies in its origin from waste materials. Unlike fossil diesel, which requires the extraction and refinement of approximately 3.8 tons of crude oil per ton and generates 0.43 tons of CO

2e in upstream processes [

25], TPO is derived from used tires—an end-of-life product containing both biogenic carbon (from natural rubber) and industrial carbon (from synthetic rubber). During pyrolysis, 60-70% of the tire’s volatile content is thermally decomposed under oxygen-limited conditions into liquid hydrocarbons. Approximately 88% of the C/H/O elements are retained in the TPO, with only 12-15% lost as CO

2 due to energy consumption in the process. The resulting oil generally contains 85-88 wt% carbon, 10-12 wt% hydrogen, and 0.5-2 wt% oxygen, indicating a composition favorable for fuel applications [

26,

27,

28,

29].

TPO is a chemically complex mixture, primarily composed of aromatic hydrocarbons (such as benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylene), along with aliphatic chains and minor sulfur- and nitrogen-containing compounds. This composition gives TPO combustion characteristics similar to those of diesel fuel, though with some operational differences. For example, its relatively low cetane number (CN ≈ 35, compared to CN > 50 for diesel) results in a longer ignition delay but can reduce peak combustion temperatures, which in turn lowers NO

x emissions by 8-12%. Due to its cyclic aromatic content, particulate emissions are also reduced by an estimated 15-20% relative to diesel, offering co-benefits in local air pollution control [

30].

Beyond direct fuel substitution, TPO can also be refined into value-added products with further emission reduction potential. Vacuum distillation separates TPO into light and heavy fractions. The light fraction (C

5–C

10), with volatility and octane ratings comparable to gasoline, can displace petroleum-based fuels and reduce emissions [

31]. The heavy fraction, rich in aromatics and resins, is suitable for steam reforming, yielding 110-130 g H

2/kg TPO with a carbon intensity of 1.5 kg CO

2e/kg H

2, about 55% lower than hydrogen from natural gas reforming [

32]. Another noteworthy compound is limonene (5-8%), a renewable terpene that serves as a green solvent [

33].

In summary, TPO serves as both a direct and indirect substitute for fossil fuels, contributing significantly to the carbon mitigation capacity of pyrolysis systems. Its versatility, energy density, and compatibility with industrial combustion processes make it a strategic asset in the transition to low-carbon and circular waste management models.

3.1.2. Recovered Carbon Black as a Material Substitute

Recovered carbon black (rCB), a major solid product obtained from the pyrolysis of WTs, exhibits high carbon content (typically 80-90%), porous morphology, and a heterogeneous microstructure. Studies have shown that rCB undergoes structural evolution from amorphous to partially graphitized carbon as pyrolysis temperature increases from 400 to 600 ℃, with enhanced crystallinity, strong C-C and S-S bonds, and reduced volatile matter, indicating its potential as a sustainable substitute for vCB in industrial applications [

34].

Unlike vCB, which is traditionally produced through the energy-intensive furnace black process using fossil-based hydrocarbons, rCB is derived from the intrinsic carbon content of tires without additional fossil fuel input. The production of 1 ton of vCB emits approximately 3.2 tCO

2, while rCB production emits significantly less, ranging from 0.8 to 1.5 t CO

2 per ton, depending on the pyrolysis conditions and energy sources used [

35,

36]. This substantial difference in carbon footprint highlights the potential of rCB in mitigating GHG emissions during the tire production lifecycle.

In terms of material performance, numerous studies have demonstrated that rCB can partially replace vCB in rubber formulations. For instance, Zhang et al. (2024) confirmed that rCB contains residual zinc sulfide and silica, which can independently catalyze the vulcanization of brominated butyl rubber (BIIR), achieving comparable curing behavior and mechanical strength to rubber filled with N660 carbon black and zinc oxide [

37]. Similarly, Bogdahn et al. (2025) reported that although rCB-based elastomers exhibited slightly lower mechanical properties than those filled with standard vCB, increasing the rCB loading partially compensated for performance loss and contributed to sustainability goals [

38].

Moreover, the quality of rCB can be significantly improved via post-treatment techniques such as chemical activation, acid demineralization, and plasma modification. These treatments enhance surface area, introduce oxygen-containing functional groups, and reduce ash and heavy metal content, thereby improving dispersion and filler-polymer interaction in rubber matrices [

39,

40,

41]. When incorporated into natural rubber composites, properly modified rCB demonstrated mechanical performance approaching that of vCB, especially under high loading scenarios [

42].

Based on the industrial-scale study by Dziejarski et al. (2024) [

43], modified recovered carbon black (M-CBp) activated at 900 °C with KOH can directly replace ≥80 % of vCB in rubber products. Given that vCB production emits 3.2 t CO₂e per ton while M-CBp requires only 0.5-0.7 t CO

2e, each ton of rCB substituted avoids 2.5–2.7 t CO

2e. Moreover, the off-gas from the pyrolysis process provides on-site energy, cutting an additional 0.8–1.1 t CO

2e per ton of finished product.

In summary, rCB offers a promising low-carbon alternative to vCB, especially when appropriately upgraded. Its integration into rubber products not only reduces dependence on fossil-based carbon black but also transforms WTs into value-added resources, thereby playing a crucial role in achieving low-carbon and circular manufacturing systems.

3.1.3. Emission Reduction Factors Across Studies

As discussed in the previous sections, two primary pyrolysis products—TPO and rCB—play central roles in offsetting upstream carbon emissions through material substitution. TPO can partially or fully replace fossil-derived diesel fuel in industrial combustion systems, while rCB can displace virgin carbon black in various rubber formulations. These substitution effects form the quantitative basis for assessing the emission reduction capacity of pyrolysis systems.

To synthesize existing evidence,

Table 2 summarizes emission factors for conventional materials and the corresponding avoided emissions achieved by replacing them with pyrolysis-derived products. The actual carbon savings depend on a variety of factors, including product quality, upgrading processes, local fuel mixes, and the degree of substitution implemented in each scenario.

As shown, the substitution of TPO for diesel yields emission savings ranging from 0.5 to 0.7 kg CO2 per kg of product, depending largely on its sulfur content and the end-use application. For rCB, studies report emission reductions between 1.8 and 2.2 kg CO2 per kg, reflecting the high energy intensity of vCB production and the substantial benefits of rCB integration in tire manufacturing. These estimates generally align with LCA modeling assumptions used in both industrial and academic analyses.

3.2. Energy Self-Sufficiency and Process Optimization

The pyrolysis gas generated from waste tire decomposition exhibits favorable fuel properties, making it a promising alternative energy source for internal energy self-supply within pyrolysis systems. The gas typically contains a high proportion of combustible compounds such as hydrogen (H

2), methane (CH

4), ethylene (C

2H

4), propane (C

3H

8), and other light hydrocarbons, along with small amounts of CO, CO

2, and sulfur-containing gases. The lower heating value (LHV) of this pyrolytic gas generally ranges between 30 and 40 MJ/m

3, comparable to natural gas and significantly higher than that of syngas derived from biomass or municipal solid waste [

46].

Due to this high energy content, pyrolytic gas is widely regarded as a viable energy carrier capable of directly supplying the thermal energy required for the pyrolysis process itself. This internal recycling of pyrolytic gas reduces, or in many cases entirely replaces, the need for external fossil fuel input. Studies indicate that in continuous or semi-continuous pyrolysis systems, the energy recovered from gas combustion can cover up to 95-100% of the reactor’s thermal demand [

47]. As such, waste tire pyrolysis can be considered a near energy-autonomous process, especially when combined with heat recovery and insulation optimization.

Replacing external energy sources with pyrolytic gas significantly contributes to GHG reduction. According to some studies, using TPG instead of coal or diesel oil can effectively reduce CO

2 emissions, depending on system efficiency and gas purification steps [

47,

48]. Furthermore, the direct use of in-situ generated gas avoids upstream emissions related to fuel extraction, refining, and transportation.

Several experimental and industrial studies have demonstrated the feasibility of using pyrolytic gas as a primary energy source in waste tire treatment systems. For instance, Campuzano et al. (2020) reported that a twin-auger continuous pyrolysis reactor operating at 475 ℃ could maintain stable operation using its own gas as the heating source, while also producing high-quality TPO and rCB [

49]. Similarly, Hoang et al. (2024) emphasized that pyrolytic gas, when properly cleaned, not only supplies sufficient thermal energy for pyrolysis but can also be used for power generation or industrial heating in cement, lime, or steel plants [

50]. Some pilot-scale systems have even integrated gas turbines or boilers for co-generation (heat and power), pushing the system toward full energy circularity.

The reuse of pyrolytic gas significantly enhances the energy efficiency and environmental performance of waste tire pyrolysis. It transforms the process into a self-sustaining, low-carbon system and reduces reliance on external energy inputs, thus aligning with broader goals of clean energy transition and circular economy implementation.

3.3. Summary of Emission Reduction Mechanisms

Waste tire pyrolysis offers a dual pathway for greenhouse gas mitigation: material substitution and energy self-sufficiency. As demonstrated in this chapter, TPO and rCB can partially replace fossil-based diesel and virgin carbon black, yielding considerable upstream emission savings. Simultaneously, the reuse of TPG as an internal heat source significantly lowers the system’s external energy demand, further contributing to emission reduction.

However, the extent of these benefits depends heavily on product quality, upgrading technologies, system configurations, and regional energy contexts. Variability in sulfur content, ash fraction, and calorific value can influence substitution rates and downstream compatibility. Moreover, most of the current emission reduction estimates rely on attributional LCA with simplified boundaries, which may not fully capture rebound effects or cross-sector interactions.

Overall, while pyrolysis is not a zero-emission technology, it presents a credible and scalable pathway for decarbonizing waste management and material production—especially when combined with advanced upgrading techniques and integrated into circular economy frameworks. The following chapter will examine how LCA has been applied to quantify these emission impacts and guide technology optimization.

4. Quantitative Carbon Reduction Strategies Based on LCA

4.1. Role and Methodological Framework of LCA

Life Cycle Assessment has emerged as the most widely adopted and scientifically recognized tool for quantifying the environmental and climate impacts of waste tire management pathways. As defined by the ISO 14040 and 14044 standards, LCA comprises four main stages: (1) goal and scope definition, (2) inventory analysis, (3) impact assessment, and (4) interpretation. Within the context of waste tire pyrolysis, LCA enables a holistic evaluation of upstream and downstream processes—including raw material acquisition, energy inputs, emissions, product substitution, and end-of-life scenarios-under a consistent accounting framework.

In recent years, LCA has played a crucial role in comparing pyrolysis against other waste tire recovery methods such as incineration, mechanical grinding, retreading, and landfilling. Unlike attributional LCA models that focus solely on direct emissions, more advanced studies have incorporated consequential LCA approaches to capture indirect system-wide effects, including the displacement of fossil-based fuels and materials by pyrolysis-derived products [

51,

52]. These “avoided emissions” are particularly relevant in pyrolysis systems, where TPO and rCB can substitute diesel and vCB, respectively—thereby reducing upstream extraction, refining, and processing emissions.

Tsangas et al. (2024) [

53] emphasized that the integration of substitution effects and circularity indicators is critical for assessing the true environmental value of pyrolysis in a circular economy framework. Similarly, Nunes et al. (2022) [

54] highlighted that the most climate-effective tire recovery scenarios are those that prioritize high substitution efficiency, product upgrading, and system integration. As such, the ability of LCA to model cross-boundary emission interactions is particularly valuable for evaluating pyrolysis systems that offer both material recovery and energy self-sufficiency.

Despite its utility, the application of LCA in the pyrolysis domain is not without challenges. Differences in methodological assumptions—such as system boundary choices, allocation principles, and functional units—can lead to considerable variation in carbon footprint estimates. Moreover, many studies still rely on attributional models with static background data, potentially underestimating the benefits of emerging technologies or dynamic policy interventions. These limitations underscore the need for transparent, scenario-based LCA frameworks that can better support both technology developers and policymakers.

In sum, LCA serves as the methodological backbone for quantifying the decarbonization potential of pyrolysis-based tire recycling. Its strength lies in its capacity to account for complex trade-offs across the full life cycle, including the emission benefits associated with material and energy substitution. The following sections explore how system boundary definitions, carbon reduction mechanisms, and comparative results influence the interpretation of LCA outcomes in the pyrolysis literature.

4.2. System Boundary Definition and Functional Units

In LCA modeling of waste tire pyrolysis, the definition of system boundaries and the selection of functional units are critical methodological choices that directly affect the comparability and interpretation of results. These elements determine not only which processes are included in the assessment, but also how the environmental burdens and benefits are normalized and communicated.

4.2.1. System Boundaries

Three typical types of system boundaries are observed in the literature:

Narrow (gate-to-gate) boundaries focus solely on the pyrolysis process itself, excluding upstream material sourcing and downstream product use. These models are useful for analyzing process energy efficiency but cannot account for substitution effects or avoided burdens.

Intermediate (cradle-to-gate) boundaries include the upstream impacts of tire collection and transportation, along with pyrolysis operations, but terminate at the factory gate without modeling product utilization.

Broad (cradle-to-grave) boundaries extend further to include downstream product applications and disposal, thereby capturing the full life-cycle benefits of substituting fossil-derived fuels and materials.

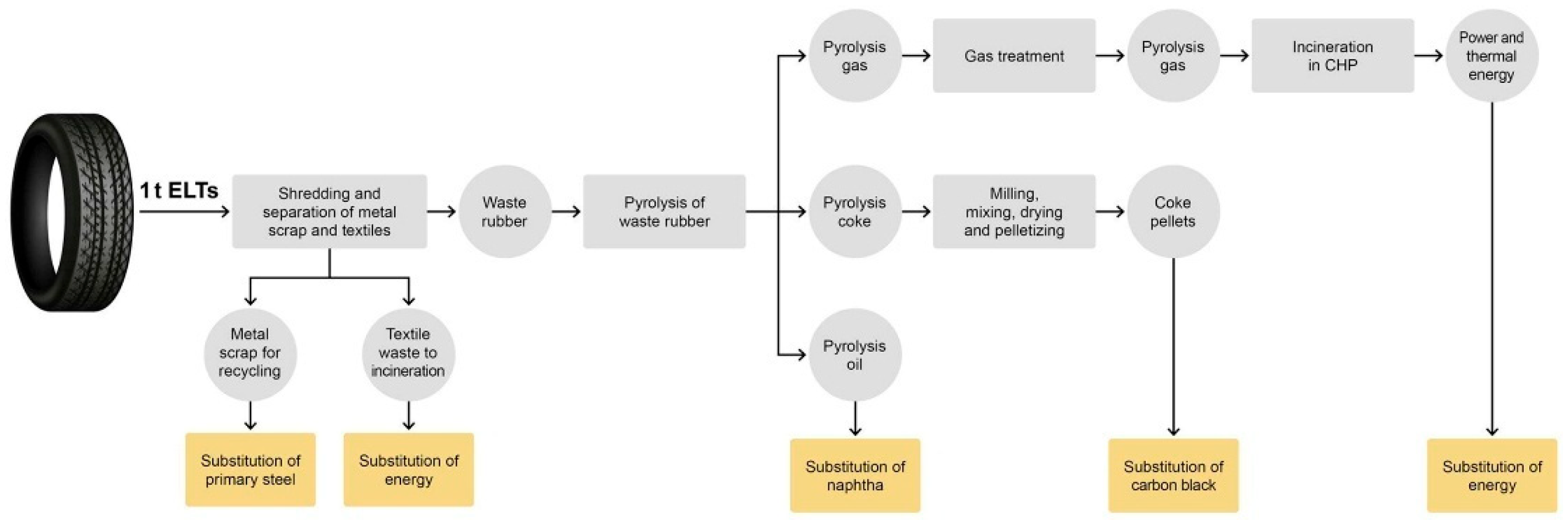

As illustrated in

Figure 2, pyrolysis-derived products—including TPO, rCB, and TPG—enable the substitution of fossil diesel, vCB, and conventional fuels, respectively. These downstream applications represent the primary source of avoided emissions in tire pyrolysis systems. However, such substitution effects can only be captured when the LCA model adopts a broad system boundary. Therefore, the inclusion or exclusion of product utilization phases directly determines the credibility and completeness of the decarbonization assessment.

This point is further supported by recent studies. Broad system boundaries are essential for evaluating the full carbon mitigation role of pyrolysis. For instance, models that exclude downstream utilization phases will miss the majority of the emission savings—such as those derived from using TPO in place of diesel or rCB in rubber manufacturing. Briones-Hidrovo et al. (2025) [

51] demonstrated that over 70% of the total climate benefit of tire pyrolysis arises from avoided emissions via substitution pathways. Their consequential LCA framework revealed that when these effects are omitted—or when system boundaries are restricted to the gate-to-gate level—the true decarbonization value of pyrolysis is significantly underestimated.

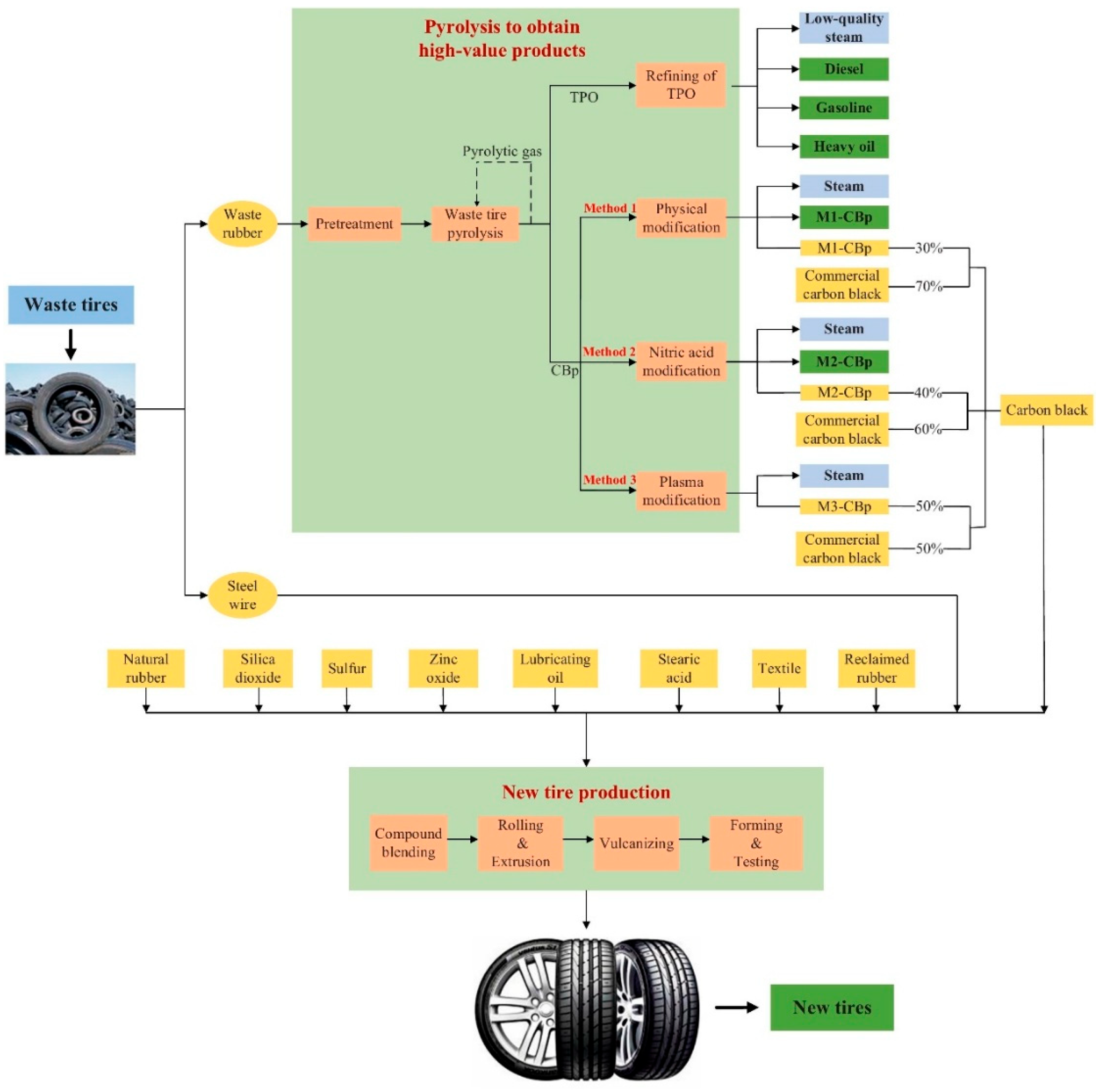

As shown in

Figure 3, adopting a cradle-to-grave perspective not only captures these downstream benefits but also reflects the broader circularity of pyrolysis systems. The diagram illustrates a closed-loop configuration in which pyrolysis products are reintegrated into new tire production, reinforcing the importance of product valorization and systemic integration. This highlights the need for expanded, cross-boundary LCA approaches to fully reflect the climate value of pyrolysis within circular economy strategies.

4.2.2. Functional Units

Equally important is the choice of functional unit, which defines the basis for impact quantification. Common units used in tire recycling LCA include:

Per ton of waste tires processed

Per unit of useful output (e.g., 1 MJ of energy, 1 kg of product)

Per functional item (e.g., 1 passenger car tire, 1 tire lifetime)

The functional unit must align with the study’s objectives and enable fair comparisons across treatment options. For example, using "per ton of waste tires" enables direct benchmarking across pyrolysis, incineration, and mechanical recycling systems. In contrast, energy-based units (e.g., per MJ) may favor energy recovery routes, while product-based units better highlight the material recovery potential of rCB or TPO. Some recent studies have adopted dual-functional units to address this bias, reporting both per-ton and per-function results for completeness.

4.2.3. Implications

Overall, system boundaries and functional units are not merely technical settings—they shape the narrative of pyrolysis’s environmental profile. Models adopting broad boundaries and product-substitution logic tend to report significantly higher emission savings than those with limited scope. To ensure transparency and comparability across LCA studies, future work should clearly state modeling assumptions and adopt harmonized boundary schemes.

The next section will explore the specific carbon reduction mechanisms reflected in LCA literature, including the substitution of fuels, materials, and process energy.

4.3. Key Carbon Reduction Pathways in Pyrolysis-Based LCA

One of the defining advantages of pyrolysis in waste tire management lies in its ability to generate marketable products that can substitute fossil-based fuels and materials. LCA models typically attribute emission reductions to three main pathways: material substitution, fuel substitution, and energy self-sufficiency. Each of these mechanisms contributes to the overall carbon mitigation performance of pyrolysis and is highly dependent on system configuration, product upgrading, and allocation rules.

4.3.1. Fuel Substitution: TPO Replacing Diesel

TPO can substitute diesel fuel in industrial burners, engines, or co-processing applications like cement kilns. Given its high calorific value (≈44 MJ/kg), comparable to commercial diesel, TPO presents a viable fossil fuel alternative. Multiple LCA studies[

45,

55,

56] estimate that replacing 1 kg of diesel with TPO can save approximately 2.7-3.2 kg CO

2e, though this figure decreases if pre-treatment (e.g., hydrotreatment or desulfurization) is required.

On a more conservative basis, LCA models often adopt an emission savings factor of 0.5-0.7 kg CO

2e/kg TPO, reflecting partial substitution and regional fuel mix variability. These values remain significant when scaled across system outputs, particularly in configurations prioritizing TPO valorization [

57].

4.3.2. Material Substitution: rCB Replacing Virgin Carbon Black

rCB, derived from the solid residue of tire pyrolysis, can partially or fully replace vCB, which is traditionally produced through fossil-fuel-intensive, high-temperature processes. According to Briones-Hidrovo et al. (2025) [

51], the production of 1 ton of vCB typically emits 2.4-3.0 tons of CO

2-equivalent, depending on the feedstock and process efficiency. In contrast, rCB production via pyrolysis results in 0.8-1.5 tons of CO

2e per ton, mainly due to lower energy consumption and avoided extraction of petroleum-based raw materials. This results in a net emission reduction of up to 72% when rCB is used as a substitute for vCB in tire or rubber manufacturing applications.

When rCB is used in tire or rubber manufacturing—particularly in secondary applications like industrial tires, flooring, or automotive parts—it can avoid up to 2.0-2.2 tCO₂e per ton of product, assuming functional equivalence and sufficient dispersion quality. Some studies [

39] report lower substitution ratios (50-70%) due to ash content or limited reinforcement properties, but modified or post-treated rCB (M-CBp) has shown improved mechanical compatibility.

4.3.3. Energy Self-Sufficiency: TPG Replacing Natural Gas or Grid Electricity

The gaseous fraction from pyrolysis—commonly referred to as TPG—has a LHV between 30-40 MJ/m

3 and can fully meet the reactor’s thermal demand when combusted onsite. Replacing external fossil energy (typically natural gas or coal-fired electricity) with TPG can reduce emissions by approximately 0.4-0.8 tCO

2e per ton of tires processed [

58].

While TPG could theoretically be refined and sold as a synthetic fuel, most pyrolysis systems use it internally due to its unstable composition and safety concerns. Consequently, its carbon benefit is modeled not as product substitution but as avoided upstream energy input.

LCA results consistently show that systems maximizing product utilization and closing material-energy loops outperform conventional recovery methods in terms of GHG reduction. However, the actual benefits depend on product quality, market integration, and boundary assumptions. As such, the next section will synthesize published LCA results to highlight these variations and identify key influencing factors.

4.4. Comparative LCA Results and Influencing Factors

Despite a growing number of LCAs on waste tire pyrolysis, their reported carbon footprints vary significantly across studies. These differences arise not only from geographical and technological variations, but also from methodological choices—such as boundary definitions, functional units, data sources, and assumptions about product substitution and upgrading. This section compares representative LCA studies and highlights key factors that drive discrepancies in emission estimates.

The table below summarizes four recent LCA studies that assess pyrolysis-based tire recycling under different scenarios. For comparability, all values are normalized to a functional unit of 1 ton of waste tires processed, with boundary types and modeling features indicated.

Table 3.

Summary of Carbon Footprint Results from Pyrolysis-Based LCA Studies.

Table 3.

Summary of Carbon Footprint Results from Pyrolysis-Based LCA Studies.

| Study |

System Boundary |

Functional Unit |

Carbon Footprint (kg CO2e/t tire)

|

Key Features |

|

| Aryan et al. (2023) [55] |

Cradle-to-grave |

1 t tire |

~644 |

Strong substitution effects (TPO, rCB); product upgrading |

|

| Briones-Hidrovo et al.(2025) [51] |

Gate-to-gate |

1 t tire |

410–470 |

Renewable energy inputs; no downstream substitution modeled |

|

| Tsangas et al. (2024) [53] |

Cradle-to-gate |

per t tire |

↓30% vs. conventional diesel path |

TPO combustion for electricity; hybrid energy recovery |

|

These results reveal three main insights: Boundary scope shapes emission intensity: Studies with cradle-to-grave boundaries consistently report greater emission reductions, as they capture avoided emissions from product substitution (e.g., TPO replacing diesel). In contrast, gate-to-gate models exclude downstream use phases, resulting in less favorable climate scores despite operational improvements. Substitution modeling is essential: The inclusion and quality of product substitution scenarios—especially for rCB and TPO—largely determine the overall decarbonization outcome. Process energy and electricity mix matter: The source of thermal and electrical energy significantly influences results.

Conclusion and Implications

The diversity in carbon footprint outcomes highlights the importance of harmonized and transparent modeling approaches. Key influencing factors include:

System boundary and inclusion of avoided emissions

Substitution rates and product upgrading assumptions

Process energy source and regional electricity mix

Quality and application of recovered products (e.g., rCB grade)

To maximize the carbon benefits of waste tire pyrolysis, future LCA models should adopt cradle-to-grave boundaries, integrate realistic substitution scenarios, and incorporate quality-adjusted product performance. Moreover, open data sharing and scenario-based modeling would enhance comparability across studies and support evidence-based policy making.

The next chapter will explore policy, regulatory, and market frameworks that can support the scale-up of low-carbon pyrolysis technologies in the context of global circular economy transitions.

5. Future Perspectives

Building on the established carbon reduction potential of waste tire pyrolysis, the path forward requires transitioning from theoretical and pilot-scale studies to scalable, standardized, and policy-integrated industrial applications. This calls for cross-disciplinary innovation and coordinated policy support to unlock the full climate and resource value of pyrolysis systems.

One of the key priorities lies in enhancing process efficiency and product quality. While current pyrolysis operations demonstrate environmental advantages, variability in feedstock composition and process control continues to yield inconsistent product quality-especially in pyrolysis oil and recovered carbon black. Future research should prioritize modular, adaptive pyrolysis systems capable of handling heterogeneous waste streams while ensuring standardized outputs. Product upgrading technologies such as hydrodesulfurization, chemical activation, and advanced filtration systems will be crucial to meet industrial specifications, reduce downstream emissions, and improve product marketability.

At the same time, accurate environmental evaluation frameworks must evolve. Current LCA often suffer from outdated emission factors, oversimplified boundary definitions, or regional mismatches. Future efforts should develop dynamic, geographically explicit LCA models that reflect real-world logistics, power mixes, and local regulatory contexts. In parallel, coupling LCA with techno-economic assessment (TEA) and social life cycle assessment (S-LCA) can help decision-makers evaluate the environmental, financial, and societal co-benefits of pyrolysis investments. As climate policy tightens, credible quantification of avoided emissions will become essential for securing carbon financing or participating in voluntary carbon markets.

Beyond technical and methodological improvements, institutional and policy mechanisms will play a pivotal role in driving adoption. Currently, pyrolysis remains underrepresented in climate action plans and circular economy strategies. Governments should consider formally recognizing pyrolysis-derived products (e.g., rCB, TPO) within green taxonomy frameworks and carbon offset registries. Subsidy mechanisms, green bonds, and emissions trading schemes could provide powerful financial incentives for facilities that demonstrate verifiable emission savings. Moreover, establishing technical standards for pyrolysis outputs and lifecycle accounting will help align industry practices, improve investor confidence, and foster market transparency.

In the broader context of sustainable development, tire pyrolysis should not be viewed merely as an end-of-life treatment, but rather as a node in a circular, decarbonized material economy. Integrated systems that combine pyrolysis with upstream reuse and downstream material reintegration-such as using rCB in new tires or TPO in regional transport fuel blends-can maximize both resource recovery and emission mitigation. To realize this vision, closer collaboration is needed between researchers, industry actors, policymakers, and financial institutions.

The future of waste tire pyrolysis lies in its ability to scale sustainably, demonstrate clear carbon benefits, and embed itself within national and global sustainability agendas. As technological innovation continues and policy support strengthens, pyrolysis has the potential to become not only a viable waste solution, but also a significant contributor to climate action, industrial decarbonization, and circular economy transformation.

6. Conclusions

This review has examined the carbon reduction potential of waste tire pyrolysis through the lens of LCA. The analysis covered key pyrolysis products—rCB, TPO, and TPG—and explored how their substitution for diesel, virgin carbon black, as well as TPG reuse respectively contributes to significant GHG emission reductions.

The comparative analysis of existing LCA literature reveals that pyrolysis offers a balanced solution with moderate emissions, strong resource recovery capabilities, and opportunities for energy self-sufficiency. While incineration and landfilling present higher environmental burdens, pyrolysis-especially when combined with upgrading and product reuse-offers a more sustainable pathway aligned with circular economy goals.

Nevertheless, realizing the full climate mitigation potential of tire pyrolysis requires overcoming technological, regulatory, and market-related barriers. Further research into localized LCA modeling, product certification, and system-level optimization is essential.

In conclusion, waste tire pyrolysis is not only a feasible waste management option but also a strategic component of the global decarbonization agenda. With continued investment in research, policy alignment, and industrial innovation, this technology can play a transformative role in building a more sustainable and carbon-efficient future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.W. and G.L.; methodology, G.L.; validation, J.X. (Junqing Xu), Q.Z. and S.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.W.; writing—review and editing, G.L. and H.Z.; funding acquisition, J.X. (Junshi Xu). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Shanghai Municipal Education Commission-Gaofeng Environment and Ecology Grant Support (Class IV) (No. HJGFXK-2020-001): Pollution Control and Resource Utilization of Typical Waste in the Mechanical and Electronic Industry.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Junshi Xu was employed by the company Tire Craftsman Carbon Neutrality Industrial. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| WTs |

Waste tires |

| TPO |

Tire pyrolysis oil |

| TPG |

Tire pyrolysis gas |

| rCB |

Recovered carbon black |

| GHG |

Greenhouse gas |

| LCA |

Life cycle assessment |

| MAP |

Microwave-assisted pyrolysis |

| FRM |

Fixed reactor mode with conventional external heating |

| vCB |

Virgin carbon black |

| LHV |

Lower heating value |

| TEA |

Techno-economic assessment |

| S-LCA |

Social life cycle assessment |

References

- Zhang M H, Qi Y F, Zhang W, et al. A review on waste tires pyrolysis for energy and material recovery from the optimization perspective [J]. Renewable & Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2024, 199.

- CUI D, BI Z H, WANG Y, et al. Scenario analysis of waste tires from China's vehicles future [J]. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2024, 478.

- OBOIRIEN B O, NORTH B C. A review of waste tyre gasification [J]. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 2017, 5(5): 5169-78.

- Xiao, Z.; Pramanik, A.; Basak, A.; Prakash, C.; Shankar, S. Material recovery and recycling of waste tyres-A review. Clean. Mater. 2022, 5. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Blanpain, B.; Guo, M.; Malfliet, A. In-situ electrical conductivity monitoring of slag solidification during continuous cooling for slag recycling. Waste Manag. 2023, 161, 234–244. [CrossRef]

- Goevert, D. The value of different recycling technologies for waste rubber tires in the circular economy—A review. Front. Sustain. 2024, 4, 1282805. [CrossRef]

- Bhalode, P.; Najmi, S.; Vlachos, D. Computation-Guided Removal of 6PPD from End-of-Life Waste Tires. ACS Sustain. Resour. Manag. 2024, 1, 2276–2283. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Cheng, M.; Xie, M.; Yang, Y.; Liu, T.; Zhou, T.; Cen, Q.; Liu, Z.; Li, B. From waste to energy: Comprehensive understanding of the thermal-chemical utilization techniques for waste tire recycling. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 211. [CrossRef]

- Soprych, P.; Czerski, G.; Grzywacz, P. Studies on the Thermochemical Conversion of Waste Tyre Rubber—A Review. Energies 2023, 17, 14. [CrossRef]

- MENG X H, YANG J X, DING N, et al. Identification of the potential environmental loads of waste tire treatment in China from the life cycle perspective [J]. Resources Conservation and Recycling, 2023, 193.

- Mavukwana, A.-E.; Sempuga, C. Recent developments in waste tyre pyrolysis and gasification processes. Chem. Eng. Commun. 2020, 209, 485–511. [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, M.; Zarmehr, S.P.; Yazdani, H.; Fini, E. Review and Perspectives of End-of-Life Tires Applications for Fuel and Products. Energy Fuels 2023, 37, 10758–10774. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, Z.; Gou, X. Advances and Outlook on Desulfurization and Utilization of Tire Pyrolysis Oil: A Review. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 21889–21912. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Ren, J.; Hu, Y.; Song, J.; Yang, W. Future projections and life cycle assessment of end-of-life tires to energy conversion in Hong Kong: Environmental, climate and energy benefits for regional sustainability. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2025, 55, 328–339. [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Ccuno, C.; Churata, R.; Martínez, K.; Almirón, J. Development and Characterization of KOH-Activated Carbons Derived from Zeolite-Catalyzed Pyrolysis of Waste Tires. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4822. [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Feng, H.; Oboirien, B.; Liu, S.; Zhang, X.; Wu, Z.; Chen, Z.; Gao, S. Catalytic upgrading of waste tire pyrolysis volatiles over Ga/ZSM-5 catalysts. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2025, 192. [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.; Wang, S.; Shan, R.; Gu, J.; Yuan, H.; Chen, Y. Characteristics and chemical treatment of carbon black from waste tires pyrolysis. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2024, 178. [CrossRef]

- LABAKI M, JEGUIRIM M. Thermochemical conversion of waste tyres—a review [J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2017, 24(11): 9962-92.

- Agblevor, F.A.; Hietsoi, O.; Jahromi, H.; Abdellaoui, H. Production of low-sulfur fuels from catalytic pyrolysis of waste tires using formulated red mud catalyst. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33121. [CrossRef]

- Undri, A.; Rosi, L.; Frediani, M.; Frediani, P. Upgraded fuel from microwave assisted pyrolysis of waste tire. Fuel 2014, 115, 600–608. [CrossRef]

- HAN W W, HAN D S, CHEN H B. Pyrolysis of Waste Tires: A Review [J]. Polymers, 2023, 15(7): 26.

- JIANG Z, LIU Y, SONG Y, et al. Review of pyrolysis for waste tires and research prospects of pyrolysis products [J]. Chemical Industry and Engineering Progress, 2021, 40(1): 515-25.

- Abdallah, R.; Juaidi, A.; Assad, M.; Salameh, T.; Manzano-Agugliaro, F. Energy Recovery from Waste Tires Using Pyrolysis: Palestine as Case of Study. Energies 2020, 13, 1817. [CrossRef]

- Papuga, S.; Djurdjevic, M.; Tomović, G.; Ciprioti, S.V. Pyrolysis of Tyre Waste in a Fixed-Bed Reactor. Symmetry 2023, 15, 2146. [CrossRef]

- IPCC. 2019 Refinement to the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories, Volume 3: Industrial Processes and Product Use [R]: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2019.

- HERNANDEZ SOBRINO F, RODRIGUEZ MONROY C, LUIS HERNANDEZ PEREZ J. Biofuels and fossil fuels: Life Cycle Analysis (LCA) optimisation through productive resources maximisation [J]. Renewable & Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2011, 15(6): 2621-8.

- Quek, A.; Balasubramanian, R. Life Cycle Assessment of Energy and Energy Carriers from Waste Matter – A Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 79, 18–31. [CrossRef]

- Toteva, V.; Stanulov, K. Waste tires pyrolysis oil as a source of energy: Methods for refining. Prog. Rubber, Plast. Recycl. Technol. 2019, 36, 143–158. [CrossRef]

- WANGLIN L U, YUQI J I N, YONG C H I, et al. Waste tire pyrolysis and appfication prospect of pyrolysis oil [J]. Chemical Industry and Engineering Progress, 2007, 26(1): 13-7.

- Fırat, M.; Okcu, M.; Çelik, O.; Altun, Ş.; Varol, Y. Comparative analysis of waste tire pyrolysis oil and gasoline as low reactivity fuel in RCCI engine. Energy Sources, Part A: Recover. Util. Environ. Eff. 2023, 45, 12243–12262. [CrossRef]

- SATIRA A. Catalytic upgrading of TPO via vacuum distillation and hydroprocessing [D]; University of Naples Federico II, 2022.

- MORENO D. Novel Catalytic Steam Processing of Hydrocarbons: Partial Steam Reforming of Oils and Low-Temperature Steam Reforming [D]; University of Calgary, 2024.

- Sathiskumar, C.; Karthikeyan, S. Recycling of waste tires and its energy storage application of by-products –a review. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2019, 22. [CrossRef]

- Fadipe, O.O.; Oyewole, K.A.; Adebanjo, A.U.; Ajiferuke, A.T.; Olukayode, O. Evaluating the reusability of carbon black recovered from waste tyres: An elemental and microstructural analysis. Results Surfaces Interfaces 2025, 18. [CrossRef]

- FAN Y, FOWLER G D, ZHAO M. The past, present and future of carbon black as a rubber reinforcing filler – A review [J]. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2020, 247: 119115.

- Wu, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, X.; Song, G.; Xiao, J. Life cycle assessment of waste tire recycling: Upgraded pyrolytic products for new tire production. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 46, 294–309. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Peng, J.; Wang, H.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, Y. Curing and reinforcement effect of recovered carbon black from waste tires on brominated butyl rubber. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2024, 258. [CrossRef]

- Bogdahn, S.; Koch, E.; Katrakova-Kr黦er, D.; Malek, C.; Katrakova-Krüger, D. Application of recovered Carbon Black (rCB) by Waste Tire Pyrolysis as an Alternative Filler in Elastomer Products. Adv. Mater. Sustain. Manuf. 2025, 2, 10008–10008. [CrossRef]

- Costa, S.M.R.; Fowler, D.; Carreira, G.A.; Portugal, I.; Silva, C.M. Production and Upgrading of Recovered Carbon Black from the Pyrolysis of End-of-Life Tires. Materials 2022, 15, 2030. [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.M.; Maganinho, C.; Mendes, A.; Rocha, J.; Portugal, I. Recovered carbon black: A comprehensive review of activation, demineralization, and incorporation in rubber matrices. Carbon Resour. Convers. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Cardona-Uribe, N.; Betancur, M.; Martínez, J.D. Towards the chemical upgrading of the recovered carbon black derived from pyrolysis of end-of-life tires. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2021, 28. [CrossRef]

- Urrego-Yepes, W.; Cardona-Uribe, N.; Vargas-Isaza, C.A.; Martínez, J.D. Incorporating the recovered carbon black produced in an industrial-scale waste tire pyrolysis plant into a natural rubber formulation. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 287, 112292. [CrossRef]

- Dziejarski, B.; Hernández-Barreto, D.F.; Moreno-Piraján, J.C.; Giraldo, L.; Serafin, J.; Knutsson, P.; Andersson, K.; Krzyżyńska, R. Upgrading recovered carbon black (rCB) from industrial-scale end-of-life tires (ELTs) pyrolysis to activated carbons: Material characterization and CO2 capture abilities. Environ. Res. 2024, 247, 118169. [CrossRef]

- Veses, A.; Martínez, J.D.; Sanchís, A.; López, J.M.; García, T.; García, G.; Murillo, R. Pyrolysis of End-Of-Life Tires: Moving from a Pilot Prototype to a Semi-Industrial Plant Using Auger Technology. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 17087–17099. [CrossRef]

- Afash, H.; Ozarisoy, B.; Altan, H. Biofuel production using tire waste in fast pyrolysis: A life cycle assessment study. Sustain. Environ. 2025, 11. [CrossRef]

- Czajczyńska, D.; Krzyżyńska, R.; Jouhara, H.; Spencer, N. Use of pyrolytic gas from waste tire as a fuel: A review. Energy 2017, 134, 1121–1131. [CrossRef]

- Afash, H.; Ozarisoy, B.; Altan, H.; Budayan, C. Recycling of Tire Waste Using Pyrolysis: An Environmental Perspective. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14178. [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, N.A.; Zorpas, A.A. Quality protocol and procedure development to define end-of-waste criteria for tire pyrolysis oil in the framework of circular economy strategy. Waste Manag. 2019, 95, 161–170. [CrossRef]

- Campuzano, F.; Jameel, A.G.A.; Zhang, W.; Emwas, A.-H.; Agudelo, A.F.; Martínez, J.D.; Sarathy, S.M. Fuel and Chemical Properties of Waste Tire Pyrolysis Oil Derived from a Continuous Twin-Auger Reactor. Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 12688–12702. [CrossRef]

- Hoang, A.T.; Nguyen, T.H.; Nguyen, H.P. Scrap tire pyrolysis as a potential strategy for waste management pathway: a review. Energy Sources, Part A: Recover. Util. Environ. Eff. 2020, 46, 6305–6322. [CrossRef]

- Briones-Hidrovo, A.; Costa, S.M.; Maganinho, C.; Silva, C.M.; Rocha, J.; Dias, A.C.; Portugal, I. Recovering carbon black from end-of-life tires: A consequential life cycle assessment. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2025, 115. [CrossRef]

- WU S C, WANG Z T, GUO S S, et al. Life-cycle-based reconfiguration of sustainable carbon black production: Integrated conventional technique with waste tire pyrolysis and its future improvement potentials [J]. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2024, 442.

- Tsangas, M.; Papamichael, I.; Loizia, P.; Voukkali, I.; Raza, N.S.; Vincenzo, N.; Zorpas, A.A. Life cycle assessment of electricity generation by tire pyrolysis oil. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 186, 376–387. [CrossRef]

- Nunes, L.J.R.; Guimarães, L.; Oliveira, M.; Kille, P.; Ferreira, N.G.C. Thermochemical Conversion Processes as a Path for Sustainability of the Tire Industry: Carbon Black Recovery Potential in a Circular Economy Approach. Clean Technol. 2022, 4, 653–668. [CrossRef]

- Maga, D.; Aryan, V.; Blömer, J. A comparative life cycle assessment of tyre recycling using pyrolysis compared to conventional end-of-life pathways. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 199. [CrossRef]

- Yaqoob, H.; Teoh, Y.H.; Jamil, M.A.; Gulzar, M. Potential of tire pyrolysis oil as an alternate fuel for diesel engines: A review. J. Energy Inst. 2021, 96, 205–221. [CrossRef]

- Gamboa, A.A.R.; dos Santos, L.R.; Martins, C.A.; Rocha, A.M.A.; Alvarado-Silva, C.A.; de Carvalho, J.A. Thermodynamic Evaluation of the Energy Self-Sufficiency of the Tyre Pyrolysis Process. Energies 2023, 16, 7932. [CrossRef]

- Mouneir, S.M.; El-Shamy, A.M. A review on harnessing the energy potential of pyrolysis gas from scrap tires: Challenges and opportunities for sustainable energy recovery. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2023, 177. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).