Submitted:

06 August 2025

Posted:

11 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

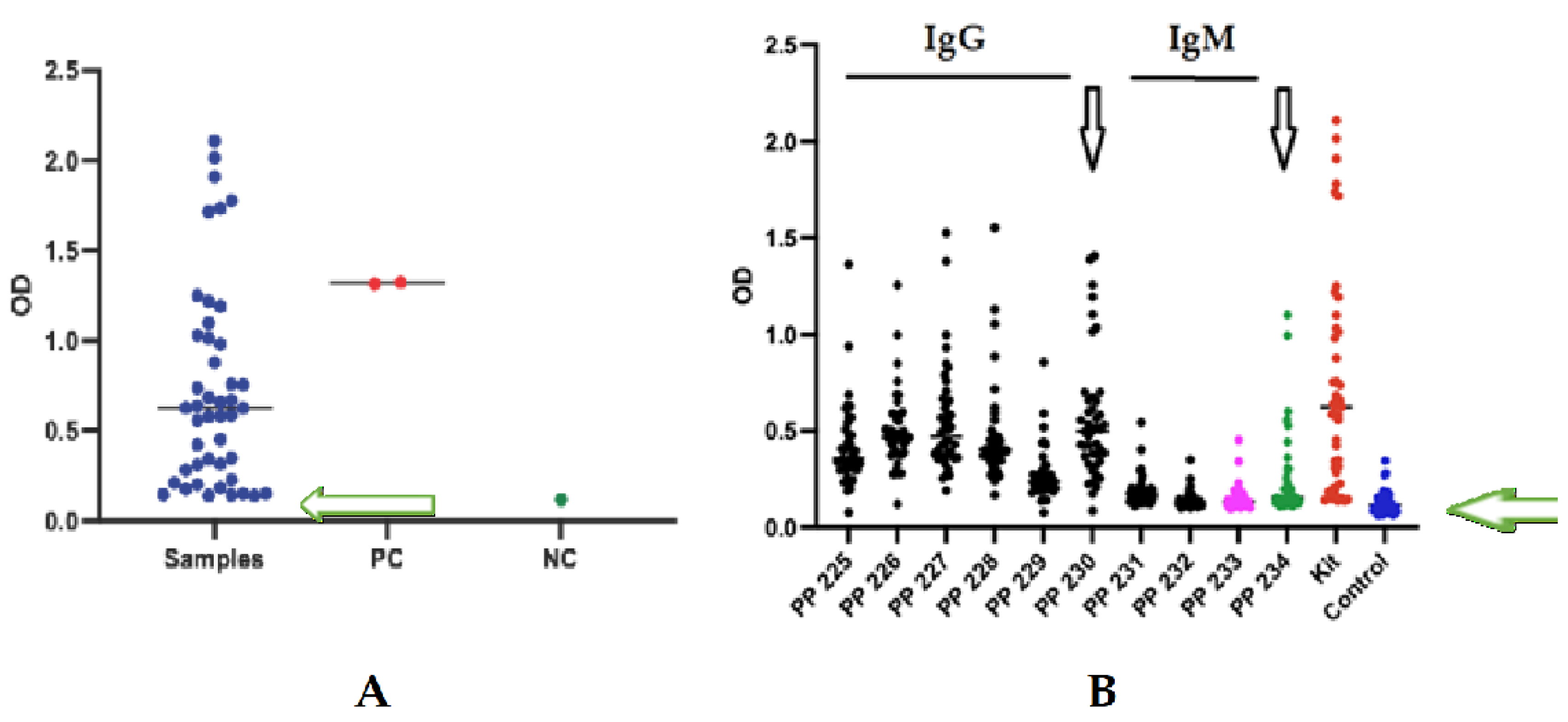

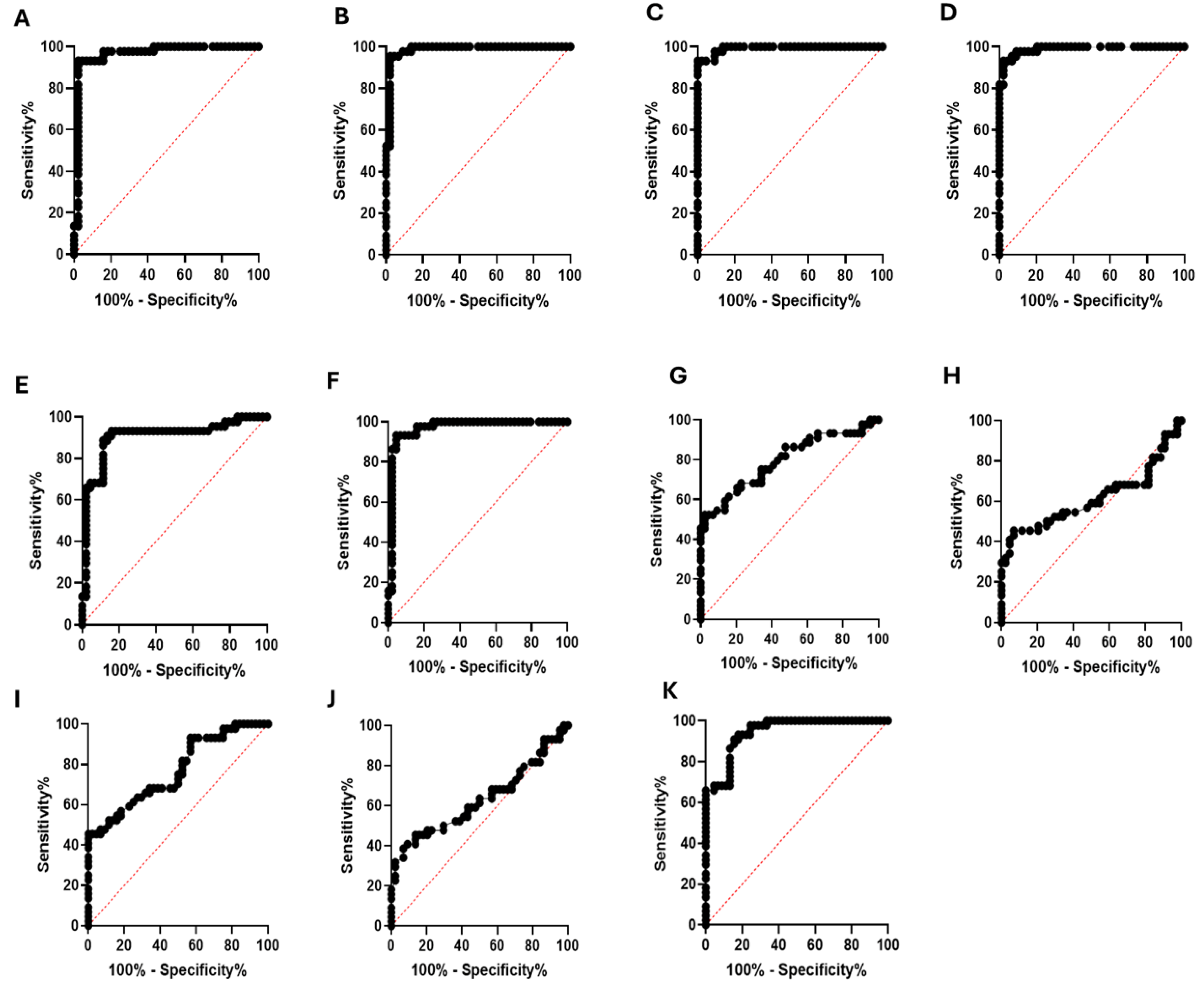

Brucellosis is one of the most serious zoonotic diseases worldwide, affecting both human and animal health. In humans, the disease often presents with diverse and nonspecific symptoms, making laboratory confirmation essential for accurate diagnosis and effective treatment. However, traditional diagnostic methods, including serological tests, suffer from limitations such as low sensitivity and high false-positive rates, underscoring the need for improved diagnostic strategies. This underscores the need for improved assays that enable rapid and reliable laboratory detection. In this study, we performed comprehensive IgM and IgG epitope mapping of the Omp-2a protein using sera from Brucella-infected patients. We identified epitopes, created chimeric peptides, and tested their diagnostic value with ELISA. Materials and Methods: The IgM and IgG epitopes of the Omp-2a protein were identified through SPOT synthesis on cellulose membranes, utilizing sera obtained from seropositive individuals. Potential cross-reactive epitopes were screened using peptide database searches and ELISA. Long, chimeric, multi-epitope peptides were synthesized and tested using ELISA on sera from 40 patients to evaluate their diagnostic performance. Results: Three major IgM and seven IgG linear B-cell epitopes were identified. None of the selected epitopes showed cross-reactivity with proteins from other significant human pathogenic organisms, as determined by analysis of peptide databases. Six peptide epitopes were confirmed using peptide-ELISA. Two chimeric peptides (50 and 60 amino acids) containing Brucella-specific IgM and IgG epitopes demonstrated high diagnostic performance, with a sensitivity of 99.96% and a specificity of 100%. Conclusion: Our study identified and validated IgM and IgG epitopes of the transmembrane Omp-2a protein from Brucella abortus. The use of these specific epitopes as biomarkers presents a promising strategy for developing accurate serological assays, potentially enhancing Brucellosis diagnosis and facilitating better monitoring of infection-induced immunity.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Human Sera

2.2. Spot Synthesis

2.3. Screening and Measurement of Spot Signal Intensities

2.4. Preparation of the Chimeric Peptides

2.5. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

2.6. Bioinformatics and In-Silico Analysis Model

2.7. Statistical Analysis

2.8. Ethical Standards

3. Results

3.1. Epitope Mapping of the Omp-2a

3.2. Shared Epitopes and Selection of Specific Brucella sp Epitopes

3.3. Structural Studies

3.4. Enzyme Immunoassay with Human Serum

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO 2019. Neglected tropical diseases. World Health Organiztion. Available online: http://www.who.int/neglecteddiseases/ zoonoses/infections_more/en/ (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- WHO, 2001. WHO recommended strategies for the prevention and control of communicable Diseases. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/brucellosis (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- Qureshi, K.A.; Parvez, A.; Fahmy, N.A.; Abdel Hady, B.H.; Kumar, S.; Ganguly, A.; Atiya, A.; Elhassan, G.O.; Alfadly, S.O.; Parkkila, S.; Aspatwar, A. Brucellosis: epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment-a comprehensive review. Ann Med 2023, 55, 2295398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swai, E.S.; Schoonman, L. Human brucellosis: Seroprevalence and risk factors related to high risk occupational groups in Tanga Municipality, Tanzania. Zoonoses Public Health 2009, 56, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laine CG, Johnson VE, Scott HM, Arenas-Gamboa AM. Global estimate of human brucellosis incidence. Emerg Infect Dis 2023, 29, 1789–1797. [CrossRef]

- Franco, M.P.; Mulder, M.; Gilman, R.H.; Smits, H.L. Human brucellosis. Lancet Infect Dis 2007, 7, 775–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saddique, A.; Ali, S.; Akhter, S.; Khan, I.; Neubauer, H.; Melzer, F.; Khan, A.U.; Azam, A.; El-Adawy, H. Acute febrile illness caused by Brucella abortus Infection in humans in Pakistan. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019, 16, 4071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, K.S.; Schuster, H.; Al-Rawahi, A.; Balkhair, A. Clinical presentations of brucellosis over a four-year period at Sultan Qaboos University Hospital and armed forces hospital, Muscat, Oman. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J 2021, 21, e282–e288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, R.; Xie, S.; Lu, X.; Sun, L.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; et al. . A systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiology and clinical manifestations of human brucellosis in China. BioMed Res Int 2018, 2018, 5712920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiiza, D.; Denagamage, T.; Serra, R.; Maunsell, F.; Kiker, G.; Benavides, B.; Hernandez, J.A. A systematic review of economic assessments for brucellosis control interventions in livestock populations. Prev Vet Med 2023, 213, 105878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ducrotoy, M.J.; Bertu, W.J.; Ocholi, R.A.; Gusi, A.M.; Bryssinckx, W.; Welburn, S.; Moriyon, I. Brucellosis as an emerging threat in developing economies: Lessons from Nigeria. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2014, 8, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agasthya, A.S.; Isloor, S.; Krishnamsetty, P. Seroprevalence study of human brucellosis by conventional tests and indigenous indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Sci. World J 2012, 20, 104–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrick, J.A.; Lederman, R.J.; Sullivan, B.; Powers, J.H.; Palmore, T.N. Brucella arteritis: Clinical manifestations, treatment, and prognosis. Lancet Infect Dis 2014, 14, 520–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blacksell, S.D.; Dhawan, S.; Kusumoto, M.; Le, K.K.; Summermatter, K.; O'Keefe, J.; Kozlovac, J.; Almuhairi, S.S.; Sendow, I.; Scheel, C.M.; et al. The biosafety research road map: The search for evidence to support practices in the laboratory-Bacillus anthracis and Brucella melitensis. Appl Biosaf 2023, 28, 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dadar, M.; Tabibi, R.; Alamian, S.; Caraballo-Arias, Y.; Mrema, E.J.; Mlimbila, J.; Chandrasekar, S.; Dzhusupov, K.; Sulaimanova, C.; Alekesheva, L.Z.; et al. Safety concerns and potential hazards of occupational brucellosis in developing countries: A review. J Public Health (Berl) 2023, 31, 1681–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memish, Z.A.; Balkhy, H.H. Brucellosis and international travel. J. Travel. Med. 2004, 11, 49–55. 10. Rahman, A.K.; Dirk, B.; Fretin, D.; Saegerman, C.; Ahmed, M.U.; Muhammad, N.; Hossain, A.; Abatih, E. Seroprevalence and risk factors for brucellosis in a high-risk group of individuals in Bangladesh. Foodborne Pathog Dis 2012, 9, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokamar, P.N.; Kutwah, M.A.; Atieli, H.; Gumo, S.; Ouma, C. Socio-economic impacts of brucellosis on livestock production and reproduction performance in Koibatek and Marigat regions, Baringo County, Kenya. BMC Veter Res 2020, 16, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, S.; Chen, Q.; Li, Z. Human brucellosis: An ongoing global health challenge. China CDC Wkly 2021, 3, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrioni, G.; Gartzonika, C.; Kostoula, A.; Boboyianni, C.; Papadopoulou, C.; Levidiotou, S. Application of a polymerase chain reaction enzyme immunoassay in peripheral whole blood and serum specimens for diagnosis of acute human brucellosis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2004, 23, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikokart 202 Freire, M.L.; Machado de Assis, T.S.; Silva, S.N.; Cota, G. Diagnosis of human brucellosis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2024, 18, e0012030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, S.; Thomson, P.C.; Hernandez-Jover, M.; McGill, D.M.; Warriach, H.M.; Heller, J. Knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP) relating to brucellosis in small holder dairy farmers in two provinces in Pakistan. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0173365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal, T.; Kara, S.S.; Cikman, A.; Balkan, C.E.; Acıkgoz, Z.C.; Zeybek, H.; Uslu, H.; Durmaz, R. Comparison of multiplex real-time polymerase chain reaction with serological tests and culture for diagnosing human brucellosis. J Infect Public Health 2019, 12, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Bonaventura, G.; Angeletti, S.; Ianni, A.; Petitti, T.; Gherardi, G. Microbiological laboratory diagnosis of human brucellosis: An overview. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusi, A.M.; Bertu, W.J.; Jesús de Miguel, M.; Dieste-Pérez, L.; Smits, H.L.; Ocholi, R.A.; Blasco, J.M.; Moriyón, I.; Muñoz, P.M. Comparative performance of lateral flow immunochromatography, iELISA and rose bengal tests for the diagnosis of cattle, sheep, goat and swine brucellosis. PLoS NeglTrop Dis 2019, 13, e0007509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinić, V.; Brodard, I.; Thomann, A.; Cvetnić, Z.; Makaya, P.V.; Frey, J.; Abril, C. Novel identification and differentiation of Brucella melitensis, B. abortus, B. suis, B. ovis, B. canis, and B. neotomae suitable for both conventional and real-time PCR systems. J Microbiol Methods. 2008, 75, 375–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeybek, H.; Acikgoz, Z.C.; Dal, T.; Durmaz, R. Optimization and validation of a real-time polymerase chain reaction protocol for the diagnosis of human brucellosis. Folia Microbiol (Praha) 2020, 65, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freire, M.L.; Machado de Assis, T.S.; Silva, S.N.; Cota, G. Diagnosis of human brucellosis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2024, 18, e0012030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbehiry, A.; Aldubaib, M.; Marzouk, E.; Abalkhail, A.; Almuzaini, A.M.; Rawway, M.; Alghamdi, A.; Alqarni, A.; Aldawsari, M.; Draz, A. The development of diagnostic and vaccine strategies for early detection and control of human brucellosis, particularly in endemic areas. Vaccines (Basel) 2023, 11, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masjedian Jezi, F.; Razavi, S.; Mirnejad, R.; Zamani, K. Immunogenic and protective antigens of Brucella as vaccine candidates. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis 2019, 65, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, M.; Rabbani-Khorasgani, M.; Zarkesh-Esfahani, S.H.; Emamzadeh, R.; Abtahi, H. Prediction of the Omp16 epitopes for the development of an epitope-based vaccine against Brucellosis. Infect Disord Drug Targets 2019, 19, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, T.; Li, Z.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, X.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, F.; Ding, J. Bioinformatics analysis of candidate proteins Omp2b, P39 and BLS for Brucella multivalent epitope vaccines. Microb Pathog 2020, 147, 104318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Sha, T.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, F.; Ding, J. Design of a new multi-epitope vaccine against Brucella based on T and B cell epitopes using bioinformatics methods. Epidemiol Infect 2021, 149, e136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira KC, Brancaglion GA, Santos NCM, Araújo LP, Novaes E, Santos RL, Oliveira SC, Corsetti PP, de Almeida LA. Epitope-based vaccine of a Brucella abortus putative small RNA target induces protection and less tissue damage in mice. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 778475. [CrossRef]

- Tarrahimofrad, H.; Zamani, J.; Hamblin, M.R.; Darvish, M.; Mirzaei, H. A designed peptide-based vaccine to combat Brucella melitensis, B. suis and B. abortus: Harnessing an epitope mapping and immunoinformatics approach. Biomed Pharmacother 2022, 155, 113557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casalinuovo, F.; Ciambrone, L.; Cacia, A.; Rippa, P. Contamination of Bovine, Sheep and Goat Meat with Brucella Spp. Ital J Food Saf 2016, 5, 5913. Ital J Food Saf 2016, 5, 5913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wareth, G.; Dadar, M.; Ali, H.; Hamdy, M.E.R.; Al-Talhy, A.M.; Elkharsawi, A.R.; El Tawab, A.A.A.; Neubauer, H. The perspective of antibiotic therapeutic challenges of brucellosis in the Middle East and North African countries: Current situation and therapeutic management. Transbound Emerg Dis 2022, 69, e1253–e1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binnicker, M.J.; Theel, E.S.; Larsen, S.M.; Patel, R. A high percentage of serum samples that test reactive by enzyme immunoassay for anti-Brucella antibodies are not confirmed by the standard tube agglutination test. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2012, 19, 1332–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikailov, M.M.; Gunashev, S.A.; Yanikova, E.A.; Halikov, A.A.; Bulashev, A.K. Indirect hemagglutination assay for diagnosing brucellosis: Past, present, and future. Vet World 2024, 17, 811–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chothe, S.K.; Saxena, H.M. Innovative modifications to Rose Bengal plate test enhance its specificity, sensitivity and predictive value in the diagnosis of brucellosis. J Microbiol Methods 2014, 97, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gemcioglu, E.; Erden, A.; Karabuga, B.; Davutoglu, M.; Ates, I.; Kücüksahin, O.; Güner, R. False positivity of Rose Bengal test in patients with COVID-19: case series, uncontrolled longitudinal study. Sao Paulo Med J 2020, 138, 561–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantur, B.G.; Amarnath, S.K.; Shinde, R.S. Review of clinical and laboratory features of human brucellosis. Indian J Med Microbiol 2007, 25, 25,188–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, H.E.; Lopez, J.; Yeh, C.; Tablante, J.; Morgan, J.; Kaneko, B.; Duffey, P. Performance characteristics of the Euroimmun enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits for Brucella IgG and IgM. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2009, 65, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chart, H.; Okubadejo, O.; Rowe, B. The serological relationship between Escherichia coli O157 and Yersinia enterocolitica O9 using sera from patients with brucellosis. Epidemiol. Infect. 1992, 108, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdenebaatar, J.; Bayarsaikhan, B.; Watarai, M.; Makino, S.; Shirahata, T. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to differentiate the antibody responses of animals infected with Brucella species from those of animals infected with Yersinia enterocolitica O9. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 2003, 10, 710–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawlins, ML; Gerstner, C.; Hill, H.R.; Litwin, C.M. Evaluation of a western blot method for the detection of Yersinia antibodies: evidence of serological cross-reactivity between Yersinia outer membrane proteins and Borrelia burgdorferi. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2005, 12, 1269–1274. [CrossRef]

- Yin, D.; Li, L.; Song, X.; Li, H.; Wang, J.; Ju, W.; Qu, X.; Song, D.; Liu, Y.; Meng, X.; et al. A novel multi-epitope recombined protein for diagnosis of human brucellosis. BMC Infect Dis 2016, 16, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koyuncu, I.; Kocyigit, A.; Ozer, A.; Selek, S.; Kirmit, A.; Karsen, H. Diagnostic potential of Brucella melitensis Rev1 native Omp28 precursor in human brucellosis. Cent Eur J Immunol 2018, 43, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, D.; Bai, Q.; Zhang, J.; Xu, K.; Li, J. A novel recombinant multiepitope protein candidate for the diagnosis of brucellosis: A pilot study. J Microbiol Methods 2020, 174, 105964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, D.; Bai, Q.; Wu, X.; Li, H.; Shao, J.; Sun, M.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, J. Paper-based ELISA diagnosis technology for human brucellosis based on a multiepitope fusion protein. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021, 15, e0009695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, A.A.M.; Ribeiro, A.J.; Resende, C.A.A.; Couto, C.A.P.; Gandra, I.B.; Dos Santos Barcelos, I.C.; da Silva, J.O.; Machado, J.M.; Silva, K.A.; Silva, L.S.; et al. Recombinant multiepitope proteins expressed in Escherichia coli cells and their potential for immunodiagnosis. Microb Cell 2024, 23, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulashev, A.; Akibekov, O.; Syzdykova, A.; Suranshiyev, Z.; Ingirbay, B. Use of recombinant Brucella outer membrane proteins 19, 25, and 31 for serodiagnosis of bovine brucellosis. Vet World 2020, 13, 1439–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulashev, A.K.; Ingirbay, B.K.; Mukantayev, K.N.; Syzdykova, A.S. Evaluation of chimeric proteins for serological diagnosis of brucellosis in cattle. Vet World. 2021, 14, 2187–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, D.; Bai, Q.; Zhang, J.; Xu, K.; Li, J. A novel recombinant multiepitope protein candidate for the diagnosis of brucellosis: A pilot study. J Microbiol Methods 2020, 2020. 174, 105964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, D.; Bai, Q.; Wu, X.; Li, H.; Shao, J.; Sun, M.; Zhang, J. A multi-epitope fusion protein-based p-ELISA method for diagnosing bovine and goat Brucellosis. Front Vet Sci 2021, 8, 708008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golchin, M.; Mollayi, S.; Mohammadi, E.; Eskandarzade, N. Development of a diagnostic indirect ELISA test for detection of Brucella antibody using recombinant outer membrane protein 16 kDa (rOMP16). Vet Res Forum. 2022, 13, 387–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binnicker, M.J.; Theel, E.S.; Larsen, S.M.; Patel, R. A high percentage of serum samples that test reactive by enzyme immunoassay for anti-Brucella antibodies are not confirmed by the standard tube agglutination test. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2012, 19, 1332–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paquet, J.Y.; Vinals, C.; Wouters, J.; Letesson, J.J.; Depiereux, E. Topology prediction of Brucella abortus Omp2b and Omp2a porins after critical assessment of transmembrane beta strands prediction by several secondary structure prediction methods. J Biomol Struct Dyn 2000, 17, 747–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulashev, A.; Eskendirova, S. Brucellosis detection and the role of Brucella spp. cell wall proteins. Vet World. 2023, 16, 1390–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roussel, G.; Matagne, A.; De Bolle, X.; Perpète, E.A.; Michaux, C. Purification, refolding and characterization of the trimeric Omp2a outer membrane porin from Brucella melitensis. Protein Expr Purif 2012, 83, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De-Simone, S.G.; Napoleão-Pêgo, P.; Lechuga, G.C.; Carvalho, J.P.R.S.; Gomes, L.R.; Cardoso, S.V.; Morel, C.M.; Provance-Jr, D.W.; Silva, F.R.S. High-throughput IgG epitope mapping of tetanus neurotoxin: Implications for immunotherapy and vaccine design. Toxins 2023, 15, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-Simone, S.G.; Souza, A.L.A.; Melgarejo, A.R.; Aguiar, A.S.; Provance, D.W., Jr. Development of elisa assay to detect specific human IgE anti-therapeutic horse sera. Toxicon 2017, 138, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutsinas, G.; Shuaib, C.; Guo, W.; Jarvis, S. Graph hierarchy: A novel framework to analyze hierarchical structures in complex networks. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 13943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.R.; Napoleão-Pego, P.; De-Simone, S.G. Identification of linear B epitopes of pertactin of Bordetella pertussis induced by immunization with whole and acellular vaccine. Vaccine 2014, 32, 6251–6258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-Simone, S.G.; Gomes, L.R.; Napoleão-Pêgo, P.; Lechuga, G.C.; de Pina, J.S.; da Silva, F.R. Epitope mapping of the diphtheria toxin and development of an ELISA-specific diagnostic assay. Vaccines (Basel) 2021, 9, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J.; Evansm, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MedCalc® Statistical Software; Version 20.218. Available on https://www.filehorse.com/download-medcalc/download/. (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Liu, C.M.; Suo, B.; Zhang, Y. Analysis of clinical manifestations of acute and chronic brucellosis in patients admitted to a public general hospital in Northern China. Int J Gen Med 2021, 14, 8311–8316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, M.; Feyzioğlu, B.; Kurtoğlu, M.G.; Doğan, M.; Dağı, H.T.; Yüksekkaya, Ş.; Keşli, R.; Baysal, B. A comparison of immuncapture agglutination and ELISA methods in serological diagnosis of brucellosis. Int J Med Sci 2011, 8, 428–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaad, A.M.; Alqahtani, J.M. Serological and molecular diagnosis of human brucellosis in Najran, Southwestern Saudi Arabia. J Infect Public Health 2012, 5, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobasheri, H.; Ficht, T.A.; Marquis, H.; Lea, E.J.; Lakey, J.H. Brucella Omp2a and Omp2b porins: single channel measurements and topology prediction. FEMS Microbiol Lett 1997, 155, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pathak, P.; Kumar, A.; Thavaselvam, D. Evaluation of recombinant porin (rOmp2a) protein as a potential antigen candidate for serodiagnosis of human Brucellosis. BMC Infect Dis 2017, 17, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, T.; Jia, H.; Xie, H.; Wu, Q.; Chen, W.; Wu, L.; Lian, D. Enhanced diagnostic accuracy of combined serological and bacteriological tests for brucella infection. Am J Transl Res. 2024, 16, 3915–3921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, M.; Guo, X.; Wu, X.; Bai, Q.; Sun, M.; Yin, D. Evaluation of the combined use of major outer membrane proteins in the serodiagnosis of brucellosis. Infect Drug Resist 2022, 15, 4093–4100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kringelum, J.V.; Nielsen, M.; Padkjær, S.B.; Lund, O. Structural analysis of B-cell epitopes in antibody:protein complexes. Mol Immunol. 2013, 53, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solís García Del Pozo, J.; Lorente Ortuño, S.; Navarro, E.; Solera, J. Detection of IgM antibrucella antibody in the absence of IgGs: a challenge for the clinical interpretation of brucella serology. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2014, 8, e3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paquet, J.Y.; Diaz, M.A.; Genevrois, S.; Grayon, M.; Verger, J.M.; de Bolle, X.; Lakey, J.H.; Letesson, J.J.; Cloeckaert, A. Molecular, antigenic, and functional analyses of Omp2b porin size variants of Brucella spp. J Bacteriol 2001, 183, 4839–4847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquis, H.; Ficht, T.A. The Omp2 gene locus of Brucella abortus encodes two homologous outer membrane proteins with properties characteristic of bacterial porins. Infect Immun 1993, 61, 3785–3790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aranís, J.C.; Oporto, C.J.; Espinoza, M.; Riedel, K.I.; Pérez, C.C.; García, C.P. Usefulness of the determination of IgG and IgM antibodies by ELISA and immunocapture in a clinical series of human brucellosis. Rev Chilena Infectol 2008, 25, 116–121. [Google Scholar]

| Code | Sequence | Peptide start | Peptide end | 2nd Structure | Ig type | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Omp-2a/1M | NNSRHDGQYGDFSDD | 116 | 130 | S+C | IgM | Brucella sp., Rhodotorula sp. |

| Omp-2a/2M | NGFSAVIALE | 151 | 165 | S+C | IgM | Brucella sp., Bartonella tamiae, Ochrobactrum sp. |

| Omp-2a/3M | FTITPEVSYTKFGGE | 285 | 300 | S+C | IgM | Brucella sp., |

| Omp-2a/4G | FNYTSNNSRHDGQYG | 111 | 125 | S+C | IgG | Brucella sp., Rhodotorula sp. |

| Omp-2a/5G | TFTGGNGFSAVIALE | 146 | 160 | S+C | IgG | Brucella sp., Bartonella tamiae, Ochrobactrum sp. |

| Omp-2a/6G | VAYDSVIEEWATKVRGDVNI | 196 | 215 | S+C | IgG | Brucella sp., Pseudochrobactrum saccharolyticum |

| Omp-2a/7G | NYGQWGGDWA | 236 | 245 | C+S | IgG | Brucella sp., Falsochrobactrum ovis, Bartonella tamiae |

| Omp-2a/8G | VWGGAKFIAPEKATF | 246 | 260 | S | IgG | Brucella sp., Falsochrobactrum ovis, Ochrobactrum anthropi |

| Omp-2a/9G | HDDWGKTAVTANVAY | 266 | 280 | C+S | IgG | Brucella sp., Falsochrobactrum ovis |

| Omp-2a/10G | KFGGEWKDTVAEDNA | 296 | 310 | C | IgG | Brucella sp. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).